Abstract

Objective:

Acute spinal cord injury (SCI) produces profound cardiovascular instability that exacerbates secondary damage, emphasizing the need for timely blood pressure management and hemodynamic support. While stabilizing hemodynamics is central to acute SCI management, evidence guiding optimal mean arterial pressure (MAP) targets, vasopressor selection, and management strategies remains limited. We conducted a narrative, comprehensive review of peer-reviewed clinical and preclinical studies addressing hemodynamic management after SCI, defined here as the first 7 days after injury, including MAP augmentation, spinal cord perfusion pressure (SCPP) monitoring, vasopressor selection, and neuromodulatory approaches.

Results:

Observational studies show that even transient hypotensive episodes within the first 72 h worsen neurological recovery. Updated guidelines recommend maintaining MAP between 75 to 80 and 90 to 95 mmHg for 3 to 7 days following injury. Norepinephrine is favored as first-line therapy because it reliably raises MAP with fewer adverse effects than other vasopressors. Neuromodulation with tSCS or eSCS has been shown to restore blood pressure and stabilize cardiovascular control in chronic SCI. Emerging evidence suggest these neuromodulatory approaches may be adapted for acute care. SCPP-guided strategies using lumbar cerebrospinal fluid drainage or direct intraspinal monitoring better reflect local perfusion and predict outcomes more accurately than MAP alone, although their use is limited to specialized centers.

Conclusion:

Hemodynamic management after SCI should be considered a therapeutic intervention that directly modifies secondary injury mechanisms. Refining MAP targets, expanding access to SCPP-guided care, and evaluating staged neuromodulation, could enhance precision and individualized care to improve long-term recovery. Large-scale multicenter trials will be essential to establish protocols that improve both neurological and cardiovascular outcomes after SCI.

1 Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) affects more than 300,000 people in the United States, with an average of 18,000 new cases each year (1, 2). These injuries produce lasting sensory, motor, and autonomic sequelae that diminish independence and quality of life (3, 4). Sensory and motor impairments generally reflect the neurological level and completeness of injury, which provides clinicians with a practical framework for treatment and prognosis (3). In contrast, autonomic dysfunction, particularly cardiovascular dysregulation, demonstrates weak and inconsistent association with neurological level and frequently occurs independently of motor and sensory deficit severity (5–7). Recent work demonstrates that the spinal cord region affected (neurological level) and American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale do not reliably predict cardiovascular instability after SCI, underscoring the need for direct autonomic assessment to better identify patients at risk of secondary complications (5). This divergence emphasizes that autonomic impairment follows a distinct pathophysiology from sensory and motor loss and highlights the need for targeted approaches to hemodynamic management after SCI.

In the immediate aftermath of an acute SCI, disruption of sympathetic autonomic pathways often leads to severe hemodynamic instability. Higher level injuries can produce unopposed parasympathetic vagal activity, resulting in hypotension and bradycardia, characteristics of neurogenic shock (8). Further, the lack of blood pressure autoregulation in the hours to days after injury increases the risk of secondary ischemic damage, worsens neurologic outcomes, and contributes to preventable mortality (9–11). Hypotension and hypoxia are well known secondary insults that worsen the extent of spinal cord damage, making aggressive hemodynamic management a mainstay of acute SCI care (12, 13).

Augmenting systemic blood pressure during the acute phase of SCI improves spinal cord blood flow to minimize further ischemic insult to the cord and is associated with improved neurological recovery (11, 14, 15). The earliest evidence that systemic blood pressure influences spinal cord blood flow dates back to the 1970’s (16), with the first studies targeting blood pressure to induce neuroprotection occurring soon after (17). Despite decades of research, high-quality studies to define blood pressure targets, monitoring techniques for perfusion, and vasopressor choice, remain limited. This in turn has weakened guideline recommendations and led to wide variability in clinical implementation (18–22).

For these reasons, there is a pressing need to clarify best practices for hemodynamic management in acute SCI. This review is structured as a narrative synthesis of peer-reviewed clinical and pre-clinical evidence to address those gaps in knowledge. Throughout this review, we use “acute” to denote the first 7 days after injury. This operational window reflects the period in which secondary ischemic and inflammatory mechanisms are most active and is consistent with prior pathophysiologic and guideline frameworks that recommend augmenting blood pressure for roughly the first week after injury (10, 22–25). We first provide a brief overview of normal autonomic control of cardiovascular function and describe how acute SCI disrupts this regulation and affects secondary injury processes to undermine neurological recovery. We then discuss current management strategies including targeting mean arterial pressure (MAP), vasopressor selection, and recent work supporting guideline updates. Next, emerging techniques that aim to improve spinal cord perfusion through pharmacologic and device-based interventions are reviewed for their translational potential. Finally, we highlight key unresolved questions in the field including the uncertainty in optimal blood pressure targets and the development of improved monitoring and techniques. This review aims to highlight the ongoing and completed work that is guiding the constantly evolving area of hemodynamic management in acute SCI. Further, we hope to bolster understanding in this area to motivate future research and guide clinicians toward better acute SCI care strategies. Recent AO Spine Knowledge Forum reports extend this framework to surgical decision making in acute traumatic SCI, emphasizing early decompression when feasible and contemporary operative strategies that are implemented within guideline-informed hemodynamic care (25, 26).

Most of the clinical and preclinical evidence that underpins current hemodynamic management guidelines comes from cohorts with acute traumatic SCI. However, similar patterns of autonomic dysfunction, blood pressure lability, and perfusion-related secondary injury are reported across traumatic and non-traumatic SCI, reflecting shared disruption of supraspinal sympathetic control (3, 27, 28). Noniatrogenic vascular causes of spinal cord ischemia, including infarction, are frequently associated with aortic pathology and are typically managed with blood pressure augmentation and in select cases, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage to support spinal cord perfusion (29). Together, these shared pathophysiologic features suggest that principles of blood pressure optimization and perfusion targeted management are mechanistically relevant across acute SCI presentations, even though guideline development has largely been driven by traumatic cohorts and dedicated validation in non-traumatic injury remains limited (22, 29).

2 Autonomic control of hemodynamics

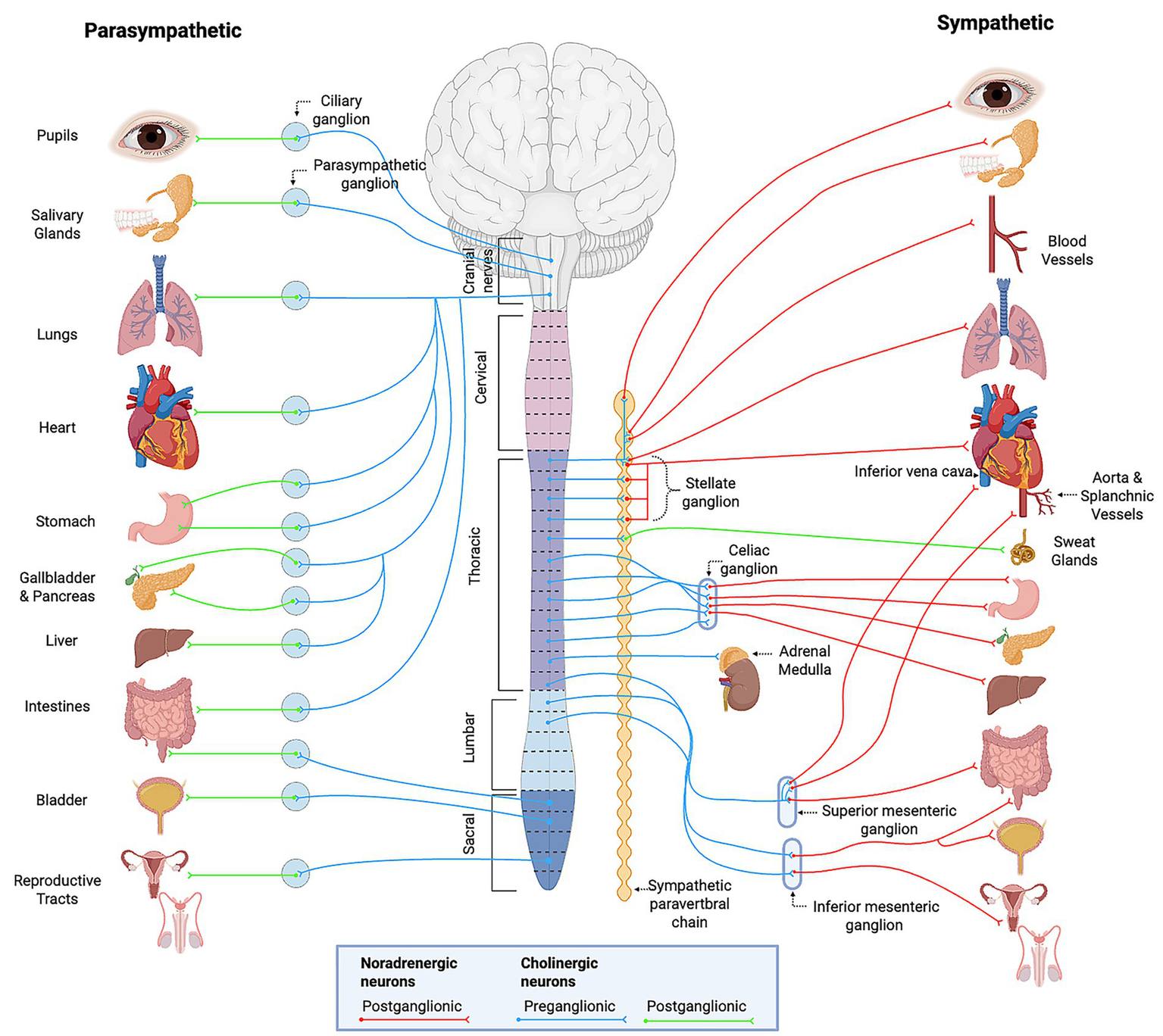

The autonomic nervous system maintains cardiovascular homeostasis by regulating heart rate, vascular tone, and cardiac output through both rapid reflex arcs and longer-term neuroendocrine mechanisms (30–32). It consists of two primary branches: the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, which exert opposing effects on cardiovascular function (Figure 1). The sympathetic nervous system increases heart rate, myocardial contractility, and vasoconstriction via the release of norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine, primarily through β1 and α1 adrenergic receptors (33–35) (Table 1). In contrast, the parasympathetic nervous system slows the heart rate and reduces atrioventricular nodal conduction mediated primarily by the vagus nerve and subsequent release of acetylcholine (ACh), which engages M2 muscarinic receptors (36). This coordinated balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity also influences numerous organ systems illustrated in Figure 2 and summarized in Table 2. The remainder of this section will focus on the autonomic control of hemodynamic function with integral neural structures and pathways discussed below.

Figure 1

Autonomic nervous system innervation. The autonomic nervous system consists of the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions: (A) Sympathetic pathway via chain ganglia. Preganglionic neurons originate in intermediolateral cell column (IML) of the spinal cord gray matter (T1-L2). Their axons exit via ventral roots, pass into spinal nerves, and enter the sympathetic chain through the white rami communicantes (myelinated preganglionic fibers). Here, preganglionic axons synapse on postganglionic neurons, releasing acetylcholine (ACh) onto nicotinic receptors. Postganglionic axons then exit the sympathetic chain, rejoin spinal nerves through the gray rami communicantes (unmyelinated fibers present at all levels), and project to effector organs, where they primarily release norepinephrine (NE) onto adrenergic receptors. (B) Sympathetic pathway via adrenal medulla. Preganglionic axons from the IML project directly to the adrenal medulla, releasing ACh onto nicotinic receptors of chromaffin cells, which then secrete epinephrine (and norepinephrine, dopamine, peptides) into the blood stream to exert a broad systemic effect by acting on adrenergic receptors of various effector organs. (C) Parasympathetic pathway. Parasympathetic preganglionic neurons originate from either brainstem nuclei (Cranial nerves III, VII, IX, and X) or from the spinal cord sacral autonomic nucleus (SAN; S2-S4). Their long preganglionic axons synapse in ganglia located near or within target organs, releasing ACh onto nicotinic receptors. Short postganglionic fibers then release acetylcholine (ACh) onto muscarinic receptors at effector organs. Source: Gordan 2015 (30); Loewy 1990 (42); Purves 2018 (32); Westfall 2011 (41). Created with BioRender.com. ACh, acetylcholine; IML, intermediolateral cell column; SAN, sacral autonomic nucleus; NE, norepinephrine.

Table 1

| Autonomic branch | Receptor | Endogenous agonist(s) | Primary sites (hemodynamic specific) | Primary hemodynamic effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sympathetic | α1-adrenergic | Norepinephrine, epinephrine | Arterioles/venous capacitance vessels; skin, splanchnic, renal; some coronary | Vasoconstriction; ↑ systemic vascular resistance; ↑ venous return |

| Sympathetic | α2-adrenergic | Norepinephrine, epinephrine | Presynaptic terminals; vascular smooth muscle | ↓ NE release (presynaptic); modest vasoconstriction postsynaptically |

| Sympathetic | β1-adrenergic | Norepinephrine > epinephrine | SA/AV nodes, atria, ventricles; juxtaglomerular cells | ↑ Heart rate, ↑ conduction, ↑ contractility; ↑ renin release |

| Sympathetic | β2-adrenergic | Epinephrine ≥ norepinephrine | Skeletal muscle arterioles, coronary and hepatic vasculature; bronchi | Vasodilation in select beds; bronchodilation |

| Sympathetic | D1 dopaminergic | Dopamine | Renal, mesenteric, coronary, cerebral arterioles | Vasodilation and ↑ renal blood flow at low doses |

| Parasympathetic | M2 muscarinic | Acetylcholine | SA/AV nodes; atrial myocardium | ↓ Heart rate and AV nodal conduction |

| Parasympathetic | M3 muscarinic | Acetylcholine | Endothelial cells of systemic/coronary vessels; vascular smooth muscle | Endothelium-dependent vasodilation via NO; context-dependent vasoconstriction if endothelium injured |

| Neuroendocrine | Angiotensin II (AT1 receptor) | Angiotensin II | Vascular smooth muscle; adrenal cortex; brainstem/hypothalamus | Vasoconstriction; ↑ aldosterone; ↑ central sympathetic outflow; ↓ baroreflex sensitivity |

| Neuroendocrine | Angiotensin II (AT2 receptor) | Angiotensin II | Endothelium; adrenal medulla; CNS (developmental prominence) | Counter-regulatory vasodilation, natriuresis, and anti-proliferative effects |

| Neuroendocrine | Arginine vasopressin (V1A) | Arginine vasopressin | Vascular smooth muscle (systemic, splanchnic) | Vasoconstriction; ↑ MAP |

| Neuroendocrine | Arginine vasopressin (V2) | Arginine vasopressin | Renal collecting duct | ↑ Water reabsorption; ↑ intravascular volume |

Autonomic and neuroendocrine receptors relevant to hemodynamic control.

Figure 2

Overview of the autonomic nervous system. General schematic of craniosacral parasympathetic and thoracolumbar sympathetic divisions, showing preganglionic and postganglionic pathways, associated ganglia, and effector organ targets. Provides context for organ-level func7ons summarized in Table 2. Created with BioRender.com. Adapted from Purves 2018 (32).

Table 2

| Effector organ | Parasympathetic action | Sympathetic action and adrenergic receptor type |

|---|---|---|

| Heart | Decreases heart rate; decreases contractility (atria) | Increases heart rate and contractility (β1) |

| Arterioles | No significant effect | Constriction (α1, α2); dilation (β2) |

| Veins | No significant effect | Constriction (α1, α2); dilation (β2) |

| Lungs (bronchioles, glands) | Constriction; stimulates secretion | Relaxation (β2); inhibits secretion (α1) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Increases motility and secretion | Decreases motility and secretion (α1, α2, β2); constricts sphincters (α1) |

| Liver | No significant effect | Glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis (α1, β2) |

| Pancreas | Stimulates insulin secretion | Inhibits insulin secretion (α2) |

| Adrenal medulla | No significant effect | Secretes epinephrine and norepinephrine (nicotinic receptors) |

| Kidney | No significant effect | Secretes renin (β1) |

| Bladder | Contracts detrusor; relaxes sphincter | Relaxes detrusor (β2); contracts sphincter (α1) |

| Male genitalia | Erection (via Nitric Oxide) | Ejaculation (α1) |

| Female genitalia (uterus) | Variable (depends on cycle stage) | Contraction (α1); relaxation (β2) |

| Sweat glands | No significant effect | Generalized secretion (muscarinic); localized secretion (α1) |

| Salivary glands | Stimulates secretion (watery) | Stimulates secretion (viscous, α1) |

| Eye (iris, pupil) | Contracts circular muscle → miosis | Contracts radial muscle (α1) → mydriasis |

| Ciliary muscle (lens) | Contracts for near vision | Relaxes for far vision (β2) |

| Skin (piloerector muscles) | No significant effect | Contraction (α1) |

Functions of the autonomic nervous system.

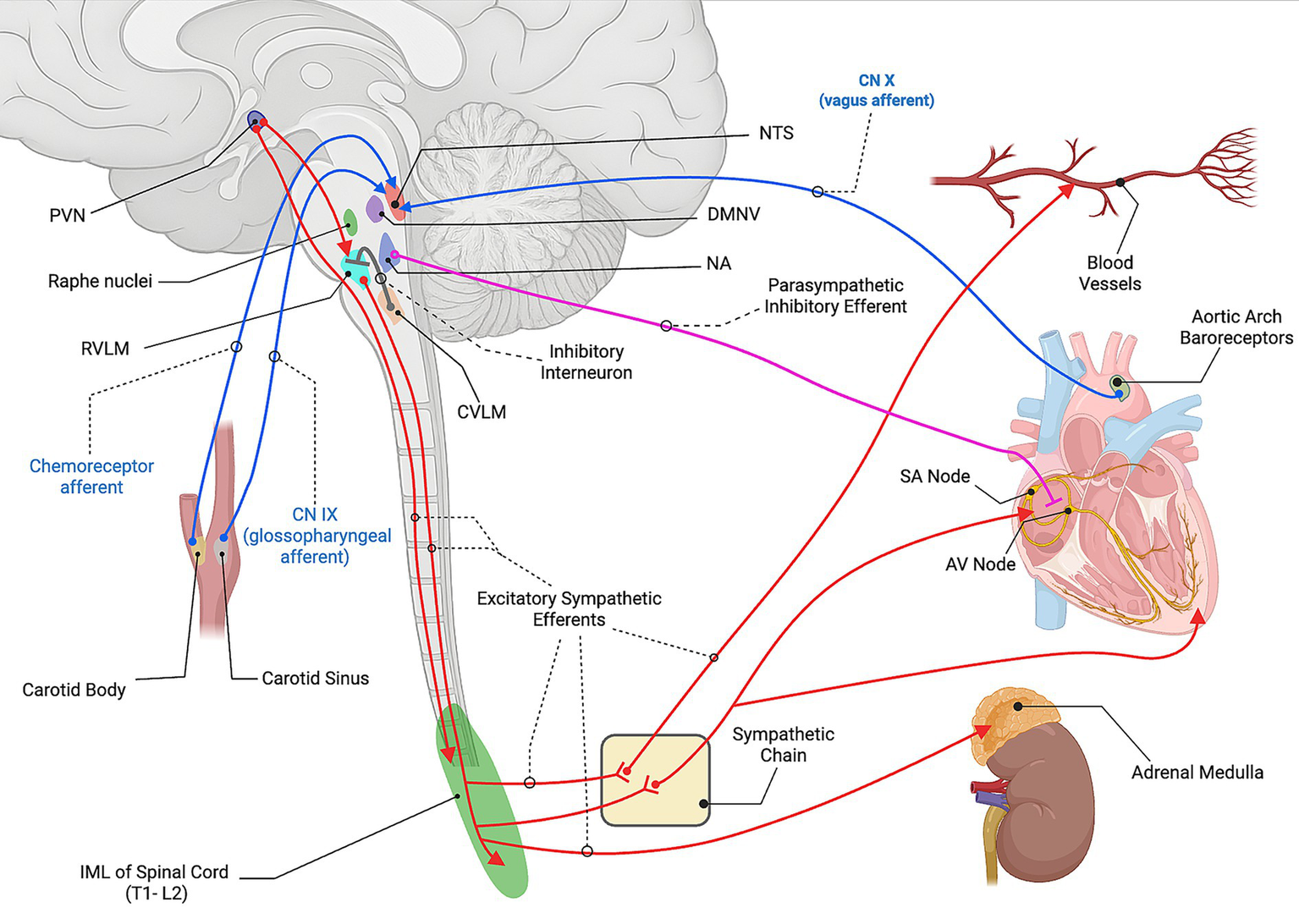

2.1 Baroreceptor reflex

The baroreceptor reflex is the principal mechanism for maintaining arterial pressure in response to rapid pressure changes (Figure 3). High-pressure baroreceptors located in the carotid sinus and aortic arch detect changes in arterial stretch and signal alterations via cranial nerves IX and X, respectively, to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in the dorsal medulla (37). The NTS serves as the primary integration area and relays excitatory glutamatergic input to two downstream centers. The first activates cardioinhibitory parasympathetic neurons in the nucleus ambiguus (NA) and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNV), which release ACh to slow the heart via M2 receptors (30). The second activates the caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM), which contains GABAergic neurons that inhibit the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), the primary excitatory output center for the sympathetic nervous system (38–40).

Figure 3

Neural control of cardiovascular function. Baroreceptor afferents from the carotid sinus (CN IX) and aortic arch (CN X), and chemoreceptor afferents from the carotid body, project to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS). The NTS activates parasympathetic cardioinhibitory neurons in the nucleus ambiguus (NA) and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNV). In parallel, the NTS activates the caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM), which inhibits the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) through interneuron projections. The paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus provides descending excitatory input to the RVLM as well as directly to the intermediolateral cell column (IML) of the spinal cord (T1-L2 overall, with cardiac sympathetic outflow primarily from T1-T5). RVLM premotor neurons drive sympathetic outflow through the IML and synapse with postganglionic fibers at the sympathetic chain that then travel to the heart and blood vessels. These postganglionic fibers release norepinephrine (NE) onto β1- adrenergic receptors in the sinoatrial node, atrioventricular node, ventricular myocardium increasing heart rate, conduction velocity, and contractility. NE also acts on the α1-adrenergic receptors on vascular smooth muscle to produce vasoconstriction. Furthermore, a subset of preganglionic fibers project directly from the IML to the adrenal medulla, where acetylcholine (ACh) activates nicotinic receptors on chromaffin cells, stimulating the release of epinephrine (Epi) and NE into the circulation. Parasympathetic vagal efferents from the NA release ACh onto muscarinic (M2) receptors in the heart to slow rate and conduction. Created with BioRender.com. Source: Dampney 1994 (37); Guyenet 2006 (38); Guyenet and Stornetta 2022 (39); Loewy 1990 (42). CN, cranial nerve; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarius; DMNV, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; NA, nucleus ambiguus; CVLM, caudal ventrolateral medulla; RVLM, rostral ventrolateral medulla; PVN, paraventricular nucleus; IML, intermediolateral cell column; SA node, sinoatrial node; AV node, atrioventricular node; NE, norepinephrine; ACh, acetylcholine; Epi, epinephrine.

When activated, signals from the RVLM descend ipsilaterally through the reticulospinal tract and terminate in the intermediolateral cell column within the T1-L2 lateral horn of the spinal cord gray matter. These neurons release glutamate to activate sympathetic preganglionic neurons, which in turn engage postganglionic neurons that release NE at peripheral sites. Furthermore, these postganglionic fibers stimulate the adrenal medulla to release epinephrine, enhancing vasoconstriction and cardiac output (33, 41).

2.2 Parasympathetic activity

Parasympathetic control of the heart is mediated through vagal efferents originating in the NA and DMNV. These neurons synapse on cardiac ganglia and release ACh, which binds to M2 receptors to activate G-protein-coupled inward rectifier potassium channels, which slows heart rate and conduction (30). While the NA is primarily involved in acute parasympathetic regulation, the DMNV contributes more broadly to visceral autonomic output (31, 36).

2.3 Supraspinal circuitry

Supraspinal structures such as the hypothalamus, periaqueductal gray (PAG), and limbic regions further refine autonomic control by integrating emotional, thermoregulatory, and endocrine signals (42).

The paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus sends glutamatergic and vasopressinergic projections to the RVLM and spinal cord to increase sympathetic drive, especially during dehydration, stress, or hypovolemia (33, 43). The PVN also modulates baroreflex sensitivity and releases arginine vasopressin, which acts on vascular V1 receptors to promote vasoconstriction and renal V2 receptors to enhance water reabsorption (44).

The PAG is a midbrain structure that contributes to both autonomic responses and descending analgesia, using serotonin (5-HT) projections from the raphe nuclei to modulate tonic sympathetic tone across circadian cycles (45, 46). Its dorsolateral columns initiate sympathetic activation during active coping (fight-or-flight), while ventrolateral regions promote parasympathetic responses (bradycardia, hypotension) associated with passive coping strategies (47).

Limbic structures, including the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex, and insular cortex process affective and visceral sensory inputs (48). These structures modulate downstream autonomic output through projections to the hypothalamus and PAG.

2.4 Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone endocrine system responds to a loss in blood pressure through the expression of angiotensin II, which augments central sympathetic outflow by acting on hypothalamic and brainstem centers and dampening baroreflex sensitivity, leading to elevated sympathetic tone (33, 45). In parallel, aldosterone promotes sodium reabsorption in the renal distal tubules, leading to intravascular volume expansion. These combined effects contribute to the long-term regulation of atrial pressure, especially during states of hypovolemia or hypotension (49, 50).

2.5 Autonomic adaptations

During exercise, descending input from motor and premotor cortices activate the hypothalamus, raising sympathetic outflow and suppressing parasympathetic activity. This allows for increased cardiac output and blood flow redistribution. The baroreflex is transiently reset to permit higher arterial pressures without reflex bradycardia (51, 52). In orthostatic stress, typically caused by gravitational shifts in blood volume (e.g., from standing up quickly), a reduction in baroreceptor stretch occurs due to a drop in arterial pressure. This elicits a rapid sympathetic response resulting in vasoconstriction and tachycardia to maintain blood pressure. However, a paradoxical surge in vagal activity, usually triggered by emotional distress or pain, can override this response causing vasovagal syncope, highlighting the sensitivity of autonomic balance (53, 54).

3 Effects of disrupted autonomic cardiovascular control after SCI

SCI interrupts the integrated neural pathways responsible for autonomic cardiovascular regulation, as described above. The cardiovascular consequences that follow injury are primarily due to the loss of supraspinal input to preganglionic neurons in the intermediolateral cell column of the spinal cord (8, 28, 31, 38). After an SCI, particularly at cervical or high thoracic levels (at or above T6), this disconnection creates a clinical state of unopposed parasympathetic vagal influence and a loss of sympathetic control below the lesion (3, 8, 55). The severity of hemodynamic compromise increases with higher and more complete injuries. High level injuries impair the descending sympathetic outflow to vascular beds such as the splanchnic circulation and heart, yielding profound vasodilation and bradycardia. Further, there is a loss of sympathetic vasoconstriction leading to systemic hypotension, often accompanied by reflex bradyarrhythmia due to unopposed vagal activity (27, 56). This is exacerbated by the disrupted arterial baroreflex pathways being unable to provide rapid blood pressure compensation (39). Together, these clinical manifestations of hypotension and bradycardia due to loss of sympathetic tone define neurogenic shock. This is a life-threatening condition that ensues within minutes of injury and in severe cases can persist for several weeks (8, 57).

In the acute phase of SCI, the failure of autonomic cardiovascular control makes the injured spinal cord especially vulnerable to secondary damage as the normal processes that manage perfusion are lost (3, 8). As a result, the secondary injury cascade is transformed from a local spinal process into a systemically driven phenomenon that exacerbates the severity of injury and undermines neurological recovery. Below, the major components of secondary injury are outlined alongside the mechanism(s) by which hemodynamic instability due to autonomic dysregulation impacts each process.

3.1 Vascular disruption and ischemia

The loss of sympathetic outflow disrupts the maintenance of perfusion pressure in the spinal cord’s microvasculature, causing it to become solely dependent on systemic pressure and positioning. Without baseline vasomotor tone or reflex vasoconstriction, acute systemic hypotension ensues, producing a critical reduction in blood flow through the injured cord. Animal and human studies have shown that even brief periods of reduced MAP can expand the area of ischemic damage and worsen long-term neurological outcomes (11, 58). It has been emphasized that ischemia is a major contributor to tissue loss, second only to the primary mechanical injury (10).

3.2 Blood-spinal cord barrier breakdown

Endothelial cells within the injured cord are sensitive to changes in shear stress, oxygen tension, and pressure. Prolonged hypotension and intermittent hypoxia induces endothelial dysfunction and tight junction disassembly, increasing blood-spinal cord barrier (BSCB) permeability (59). While inadequate perfusion can lead to endothelial cell swelling and/or death, reperfusion surges can physically stretch capillaries and promote barrier leakage. Zhou and colleagues (60) observed that within minutes of injury, abnormal venous pooling and pressure changes occur causing junctional gap formation in capillary endothelium and leakage of the BSCB. Leukocytes are rapidly recruited to these leaky vessels (within 15–30 min post-SCI) and transmigrate through the vessels, further widening the junctional gap and exacerbating BSCB breakdown. Together, these events result in vasogenic edema and accumulation of pro-inflammatory cells at the injury site, enhancing secondary damage (58).

3.3 Excitotoxicity and ionic imbalance

Neurons and glia in the injured spinal cord require adequate blood flow to meet their energy demands. The ischemic local environment due to inadequate blood flow leads to rapid depletion of ATP and subsequent failure of energy-dependent ion pumps (61, 62). Consequently, neurons accumulate intracellular sodium and calcium ions, leading to depolarization and release of excess glutamate into the extracellular space. This excess glutamate over activates NMDA and AMPA receptors on local neurons, triggering an excitotoxic process with calcium-mediated cell injury and death.

3.4 Oxidative stress

Cycles of ischemia and reperfusion due to hemodynamic instability initiate bursts of oxidative damage after SCI. In an uninjured state with normal autonomic cardiovascular regulation, blood flow is maintained within a narrow range. After SCI, impaired sympathetic regulation leads to a loss of the vasomotor responses that normally dampen extreme fluctuations of blood flow. The combination of baseline hypotension and intermittent hypertensive states (autonomic dysreflexia) brings a wide range of perfusion pressures at the injury site (9, 63). It has been observed that regions of the injured spinal cord experience repeated phases of low perfusion followed by hyperemia in the acute phase of SCI (58). When perfusion is restored to ischemic tissue, a surge of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species is generated (64). These free radicals attack lipids, proteins, and DNA, further increasing cellular injury with each occurrence.

3.5 Inflammation

Necrotic cell death in hypoperfused spinal tissue leads to the release of danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are not effectively cleared from the site of injury. DAMPs activate pattern recognition receptors on resident microglia/ astrocytes and bolster the recruitment peripheral immune cells (65). Combined with the BSCB disruption, this facilitates the influx of circulating leukocytes, complement, and other inflammatory mediators (66). The resulting prolonged inflammatory response allows for increased local tissue loss and lesion expansion, impeding neurological recovery (67).

Additionally, SCI induces a systemic immunosuppressive state driven by maladaptive sympathetic and hypothalamic activation (68, 69). Disinhibited sympathetic outflow releases excess NE at immune organs such as the spleen and lymph nodes. This contributes to apoptosis of T- and B-cells and reduces cytokine production. Concurrently, activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis drives systemic glucocorticoid release, further suppressing the inflammatory cascade. Together, this activity leads to dampened peripheral immune processes, even as inflammation persists at the injury site.

3.6 Apoptosis and oligodendrocyte loss

Neurons and oligodendrocytes are highly sensitive to ischemic events. Following SCI, repeated bouts of hypoperfusion lead to extended periods of metabolic stress in the spinal tissue surrounding the primary injury. This contributes to widespread apoptosis of both neurons and oligodendrocytes that expands the area of secondary injury. Fluctuating blood pressure in the subacute phase of SCI has been found to correlate with greater oligodendrocyte loss and demyelination (58). As oligodendrocytes die and myelin degenerates, previously functional axons in spared tissue lose conductance, worsening the neurological deficit. Hawryluk et al. (2015) found that patients with fewer periods of hypotension in the acute phase had greater white matter preservation, suggesting that maintaining stable perfusion pressures helps limit apoptosis (11).

3.7 Hemorrhage expansion

Immediately after injury, there is often a central area of hemorrhage at the injury site due to ruptured microvessels. Without intact autonomic reflexes, the balance of spinal cord perfusion pressure is lost. Low pressures leads to tissue infarction that then bleed upon reperfusion, while high pressures can further rupture already damaged vasculature with increased blood infiltrating the spinal parenchyma (70). Extravasated blood is cytotoxic to the local spinal tissue. Hemoglobin from ruptured red blood cells breaks down into heme and free iron, which drives oxidative stress and neuronal death via lipid peroxidation and iron-catalyzed hydroxyl radical formation (71, 72). Additionally, heme activates inflammatory signaling via TLR4, promoting cytokine release and lesion expansion (73). Increased hemorrhage at the lesion site is associated with worsened locomotor outcomes in rodents (74–76). This is further supported by human studies, which have shown intramedullary hemorrhage is a strong predictor of irreversible motor paralysis in cervical SCI (77, 78).

4 Hemodynamic management in acute SCI

Preventing further spinal cord ischemia during the acute phase of SCI remains one of the few interventions available to clinicians to improve neurological recovery following injury. This involves prompt surgical decompression of the injured spinal cord, coupled with vigilant respiratory management and proactive hemodynamic monitoring and support (79–81). These interventions are critical to minimize secondary ischemic damage allowing for maximal tissue preservation, as discussed above (10, 29, 82). Here, we discuss the evolution of currently available therapeutic interventions as well as future directions for the treatment of hemodynamic instability during the acute phase of SCI.

4.1 Targeting MAP

Over the past few decades, research has focused on optimizing hemodynamic protocols that maintain spinal cord perfusion and limit secondary injury after SCI (Table 3). In 2008, the Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine issued the first formal guidance to maintain MAP at or above 85 mmHg for at least 7 days post injury (83, 84). Interestingly, this recommendation was largely based on the results from two small, uncontrolled clinical studies from the 1990s by Levi et al. (85) and Vale et al. (86). In 2013, the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons set a more stringent guideline recommending MAP be maintained between 85 and 90 mmHg for 7 days (87). Because these guidelines were based on limited and low-quality data and were difficult to achieve in routine ICU care, subsequent studies have emphasized three questions: (1) When to initiate MAP augmentation; (2) where to set practical lower and upper MAP bounds; and (3) how long to continue support?

Table 3

| Source | Design | Injury | Protocol | Follow-up | Primary outcome | Key finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levi 1993 (85) | Prospective case series; N = 50 | Acute cervical SCI; complete and incomplete | Aggressive hemodynamic support with fluids + vasopressors; target MAP > 90 mmHg for 7 days post-SCI | 6 weeks | Neurologic improvement (modified Frankel and motor scores) | Protocol feasible and safe; hemodynamic parameters did not distinguish complete versus incomplete injuries, but a “severe hemodynamic deficit” profile (disproportionately low PVRI versus SVRI) predicted no recovery in Frankel A + B patients, whereas 13 of 29 without this profile improved. |

| Vale 1997 (86) | Prospective series; N = 77 (64 with 12-mo follow-up) | Acute cervical and thoracic SCI; ASIA A–D | SBP > 90 and MAP 85–90 mmHg; vasopressors + fluids; typically 7 days; early decompression when feasible | Neurologic outcome at discharge and 12 months | ASIA conversion / motor recovery | MAP augmentation strategy with early decompression associated with higher-than-expected neurological improvement versus historical controls. |

| Hawryluk 2015 (11) | Observational cohort; N = 74 | Acute SCI; first 2–3 days post-injury | Exposure analysis of MAP levels (no fixed target); evaluated thresholds including ≥85 mmHg across first 2–3 days | Discharge and 6-month neurologic outcome | Association of MAP exposure with ASIA motor score / conversion | Higher MAP early after injury correlated with better neurologic recovery; hypotension predicted worse outcomes. |

| Catapano 2016 (94) | Retrospective cohort; N = 62 | Acute complete SCI at presentation (initial ASIA A) | MAP values measured over first 7 days; vasopressor use captured | Discharge neurologic status | ASIA conversion from complete (A) to higher grade | Higher mean MAP values associated with neurologic improvement; vasopressor requirement tracked with severity. |

| Haldrup 2020 (14) | Retrospective cohort; N = 129 | Acute SCI | Initial ED/prehospital MAP levels analyzed | Long-term functional outcome | Association of initial MAP with outcome | Higher initial MAP associated with better long-term outcome; hypotension predicted worse recovery. |

| Weinberg 2021 (93) | Retrospective single-center cohort; N = 136 | Acute blunt SCI; mixed ASIA A-D | MAP goal ≥85 mmHg for first 72 h; vasopressors as needed | Hospital discharge | ASIA grade change | Greater proportion of MAP readings ≥85 mmHg predicted ASIA improvement; effect mediated by vasopressor dose. |

| Clark 2023 (88) | Retrospective cohort; N = 99 | Acute SCI | Depth of prehospital hypotension and lowest prehospital MAP analyzed versus MRI neuroanatomy | Early ASIA grade / MRI lesion measures | Probability of motor-incomplete injury; neural tissue preservation | Each 5-mmHg increase in lowest per-episode MAP increased odds of motor-incomplete injury; hypotension linked to neural tissue loss. |

| Torres-Espín 2021 (89) | Retrospective multicenter cohort; N = 118 (confirmatory regression N = 103) | Acute SCI | Data-driven analysis of intraoperative MAP | Hospital Discharge | ASIA grade change (≥ 1 level) | Identified a target range of approximately 76 to 104–117 mmHg; more time spent outside the optimal MAP range was associated with a lower probability of neurologic improvement. |

| Chou 2022 (90) | Retrospective multicenter cohort; N = 74 training, N = 59 external validation | Acute SCI | Modeled intraoperative MAP features based on thresholds identified by Torres-Espín 2021 | Hospital Discharge | ASIA grade change (≥ 1 level) | Hypertension during surgery was a stronger negative correlate than hypotension; avoiding MAP above ~104 mmHg improved outcomes. |

| Almeida 2021 (91) | Multicenter preclinical secondary analysis (MASCIS); N = 1,125 rats | Thoracic contusion SCI in rats (T9–10), drop heights 12.5, 25, 50 mm | Perioperative MAP via arterial catheter (20 min pre-injury, at injury, 20 min post-injury); relationship of MAP to recovery assessed | Acute 48 h and weekly to 6 weeks | BBB locomotor recovery change, % weight gain | Interaction between MAP and injury severity: in moderate injury, higher MAP predicted better recovery; in severe injury, higher MAP predicted worse recovery. |

| Lariccia 2024 (92) | Retrospective single-center cohort; N = 53 | Acute SCI; ASIA A–D at presentation | Early ‘hyperperfusion’ (mean MAP >90 mmHg within first 8 h and over 72 h) versus standard care | Discharge and/or 6-month outcome | ASIA conversion / motor score improvement | Early sustained MAP >90 mmHg associated with greater neurologic improvement compared with standard care. |

| Drotleff 2022 (95) | Prospective pilot; N = 20 | Acute SCI | Protocolized MAP ≥85–90 mmHg with fluids/vasopressors guided by PPV/SVV/CI over 7 days | ICU course; early neurologic exam | Feasibility; hemodynamic optimization metrics | Protocol achieved MAP targets with minimal fluid overload; highlighted utility of advanced monitoring to avoid under/over-resuscitation. |

| Långsjö 2024 (96) | Retrospective two-cohort comparison; N = 51 (higher MAP n = 32; lower MAP n = 19) | Acute cervical SCI | ICU MAP targets 85–90 versus 65–85 mmHg; 1-min recording over up to 7 days; 3-day MAP % ≥ 85 summarized | ASIA conversion at discharge | ASIA improvement versus MAP target group and MAP % ≥ 85 | Higher MAP targets produced greater elevated MAP exposures but did not yield statistically different neurologic recovery; MAP % ≥ 85 did not correlate with outcome. |

MAP-targeted strategies in acute SCI.

Clinical and preclinical studies of mean arterial pressure augmentation, including design, injury level, protocol, follow-up, outcomes and key findings. MAP, mean arterial pressure; SCI, spinal cord injury; ASIA, American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale; SBP, systolic blood pressure; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; BBB, Basso–Beattie–Bresnahan locomotor score; PVRI, pulmonary vascular resistance index; SVRI, systemic vascular resistance index; PPV, pulse pressure variation; SVV, stroke volume variation; CI, cardiac index; ICU, intensive care unit; ED, emergency department.

4.1.1 Initiation timing

Hawryluk et al. (11) provided early evidence that higher MAP values in the first 2–3 days post injury correlate with greater neurological improvement, whereas prolonged hypotension correlated with worse outcomes. In their analysis of 100 patients who received 5 days of MAP targeted therapy (>85 mmHg), they found the proportion of time below the 85 mmHg threshold during the initial 72 h was a stronger predictor of poor recovery than average MAP. This suggests that preventing hypotension may be more critical than achieving supraphysiologic pressures. Building on this, Haldrup et al. (14) demonstrated that maintaining MAP above 80 mmHg as early as pre-hospital transport through the intraoperative and ICU periods was associated with significantly better long-term motor outcomes 1-year following injury in a retrospective cohort of 129 patients. Consistent with these findings, Clark et al. (88) reported that even brief hypotension prior to hospital arrival can exacerbate secondary injury. In their sample of 99 SCI cases, each 5 mmHg increase in the lowest recorded prehospital MAP was associated with a 34% increase in the likelihood of an incomplete (versus complete) neurological grade at admission. These findings underscore the importance of early and aggressive blood pressure support immediately after SCI, even before patients reach the hospital.

4.1.2 Double edged sword of MAP limits

While avoiding hypotension is clearly vital, emerging data also highlight the potential risks of excessive hypertension (i.e., hyperperfusion). Torres-Espin et al. (89) applied machine learning techniques to intraoperative hemodynamic records from 118 acute SCI surgeries across two centers. They identified an intraoperative MAP range with a lower limit of 76 mmHg and an upper boundary between 104 and 117 mmHg that was associated with the best chance of improved neurological recovery. Patients who experienced MAP values outside of this window had significantly worse neurological outcomes, indicating that both hypoperfusion and extreme hyperperfusion during surgery can be detrimental. A follow-up study by Chou et al. (90) corroborated these thresholds using a decision-tree machine learning model. In 74 surgical patients, they found that an average intraoperative MAP of 80–96 mmHg was associated with the highest likelihood of motor grade improvement, whereas all patients whose mean intraoperative MAP exceeded ~96 mmHg showed no neurological improvement. Additionally, spending more than 93 min outside of the 76–104 mmHg range (especially above the upper bound) was linked to worse functional outcomes at discharge. Collectively, these results provide strong evidence that there is an optimal MAP in the acute phase and that both prolonged hypotension and excessive hypertension beyond the upper limit can worsen recovery. Notably, this principle appears to hold in preclinical models as well. A meta-analysis of 1,125 rats with SCI found that low blood pressure exacerbated injury in moderate contusions, whereas high blood pressure worsened outcomes in severe contusions (91).

4.1.3 Hyperperfusion is detrimental

Many centers have historically overshot MAP targets (i.e., induced systemic hypertension) to ensure patients remain above the recommended minimum, but this practice is now being reexamined. One observational study of ICU patients with acute SCI found that maintaining MAP strictly within the 85–90 mmHg guideline was practically unachievable, with a success rate of only about 24% of recorded MAP values lying within this range over the first 5 days (21). Attempts to maintain higher mean pressures tended to increase MAP variability and expose patients to more episodes of hypertension. Nonetheless, some have postulated that deliberately tolerating or inducing hyperperfusion might confer additional benefit to the injured cord (92). In a single-center retrospective cohort, early MAP goal attainment correlated with better short-term neurological improvement: patients who spent less time below 85 mmHg in the first 12 h had higher odds of ASIA grade improvement, and their mean MAP was higher during that window (92). Notably, the cohort with early improvement exhibited incomplete injuries (ASIA C) at baseline and far fewer interfacility transfers, though the analysis lacked multivariable adjustment. These factors warrant caution in inferring causality and suggest that early target attainment may be, in part, a marker of baseline neurological status and care pathway rather than a pure effect of hyperperfusion alone. Their observations reinforce other findings that more time spent with blood pressure above 85 mmHg early after injury is associated with improved neurological outcomes (93, 94). However, there is very limited evidence to support pushing MAP to higher values that may tax the physiologic limits of the spinal cord. The potential downsides of vasopressor-induced hypertension (cardiac stress, arrhythmias, peripheral ischemia, etc.) have led many investigators to question the common practice of routinely overshooting MAP targets (21, 95). A pilot study by Drotleff et al. (95) using advanced hemodynamic monitoring found that acute SCI patients often have a reduced systemic vascular resistance index (due to lack of sympathetic outflow to blood vessels) while MAP, cardiac index, and heart rate were in reference ranges. Thus, they argue that vasopressor use to achieve very high MAP levels may not bolster spinal cord perfusion.

4.1.4 Lower MAP targets

On the other end of the spectrum, studies have explored whether lower MAP goals might be sufficient for improved outcomes. Långsjö et al. (96), performed a retrospective comparison of two MAP protocols in 51 patients with cervical SCI for at least 3 days post injury: One group was managed to a traditional MAP of 85 to 90 mmHg in the ICU, while the other had a more moderate target of 65 to 85 mmHg. As expected, the higher MAP group received more vasopressors and achieved substantially higher pressures. Importantly, however, neurological recovery at 1 year was equivalent between the two groups, and there was no correlation between individual MAP levels and degree of motor improvement. These clinical findings suggest that a more modest MAP target may be adequate. This work aligns with the earlier observations from Martin et al. (97) finding that augmenting blood pressure to meet MAP goals of 85 to 90 mmHg in the first 72 h conferred no significant improvement in ASIA motor scores by hospital discharge. In their cohort, patients with more severe injuries had more hypotensive episodes and consequent vasopressor treatment to maintain MAP, yet the blood pressure augmentation itself did not translate into superior recovery. Together, these studies suggest that for many patients, preventing hypotension with a practical MAP floor near 75 to 80 mmHg may be sufficient, while enforcing a narrow supraphysiologic target offers no proven neurologic advantage.

4.1.5 Impact on guidelines

Evolving insights from the past decade have informed updates to clinical guidelines. Most recently, in 2024 a new multidisciplinary guideline for hemodynamic management in acute SCI by AO Spine, American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons was published (22). They recommended augmenting MAP to at least 75 to 80 with an upper limit not to exceed 90 to 95 mmHg. The guideline also reduced the suggested duration of MAP support to 3–7 days after injury, acknowledging the most critical period for perfusion is likely within the first several days. Notably, the panel graded the evidence as very low and the recommendations as weak, emphasizing the need for an individualized approach tailored to each patient. These recommendations align with AO Spine guidance on decompression timing, which favors surgery within 24 h when medically feasible and underscores the need to individualize timing based on patient and injury characteristics (25). The accompanying AO Spine Clinical practice recommendations describe contemporary surgical strategies and emphasize that perfusion targets, decompression, and postoperative ICU management are most effective when implemented as a coordinated acute care pathway (26). Taken together, these hemodynamic and surgical updates represent a more nuanced approach that balances the need to prevent hypotension against the risks of excessive hypertension in the early post-injury period.

4.2 Targeting spinal cord perfusion pressure

After SCI, the injured cord often swells within the spinal canal, raising intrathecal pressure and reducing spinal perfusion even when systemic MAP is normal (98). Thus, augmen7ng blood pressure while u7lizing MAP as a therapeu7c target alone may be insufficient. Due to this, utilizing spinal cord perfusion pressure (SCPP) as a target has emerged as a promising and more reliable hemodynamic strategy in acute SCI. SCPP represents the pressure gradient driving blood flow through the injured spinal cord, defined as MAP minus intrathecal (or intraspinal) pressure. This is analogous to cerebral perfusion pressure management in traumatic brain injury, where intracranial pressure is subtracted from MAP to ensure adequate brain perfusion (99). Intrathecal pressure (ITP) and intraspinal pressure (ISP) are two terms (defined below) that are sometimes inaccurately used interchangeably when describing SCPP-guided therapy. Obtaining ITP and ISP measures to calculate SCPP requires different monitoring techniques, each with their own safety, efficacy, and feasibility concerns. There are limited data on the feasibility, safety, and effects of targeting SCPP as compared to MAP (19, 100). This remains an active area of research with early results reviewed here (Table 4).

Table 4

| Source | Design | Injury | Monitor / device | Protocol | Follow-up | Primary outcome | Key finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwon 2009 (101) | RCT; N = 22 | Acute cervical SCI; ASIA not specified | ITP via lumbar intrathecal catheter + arterial line | Drainage for 72 h to reduce ITP and raise SCPP; MAP augmented per ICU protocol | 72 h and 6-month | Feasibility and effect on SCPP | CSF drainage increased SCPP at 72 h; no between-group difference in 6-month motor outcomes. |

| Werndle 2014 (98) | Prospective feasibility cohort; N = 18 | Acute cervical and thoracic SCI; ASIA A–C | ISP at injury site via subdural Codman microsensor | Probe inserted ≤72 h post-injury; monitored up to 1 week. Observed effect of dural decompression | ICU monitoring ≤ 1 week | Feasibility/safety; spinal cord physiology | High ISP and low SCPP common after laminectomy; dural decompression improved SCPP and reactivity (sPRx). |

| Varsos 2015 (107) | Observational cohort; N = 18 | Acute cervical and thoracic SCI; ASIA A–D | ISP probe at injury site + arterial line | Probe within 72 h; monitored up to 1 week; waveform and reactivity analysis | ICU monitoring ≤ 1 week | Biophysics of ISP/SCPP; sPRx relation to SCPP | Identified U-shaped sPRx–SCPP curve and pressure–volume features; foundational for SCPPopt concept. |

| Phang 2015 (106) | Prospective cohort; N = 21 | Acute cervical SCI; ASIA A–C | ISP probe at injury site | Monitored up to 1 week; compared bony decompression versus expansion duroplasty | 2–3 weeks MRI; 6-month outcomes | Radiologic decompression and spinal cord physiology | Duroplasty lowered ISP, increased SCPP, and improved sPRx; group mean SCPPopt 90 mmHg (patient range 60–120 mmHg). |

| Chen 2017 (108) | Prospective cohort; N = 14 | Acute cervical and thoracic SCI; ASIA A–C | Injury-site ISP probe (subdural Codman) + arterial line; continuous SCPPopt calculation; microdialysis in subset | Continuous SCPP monitoring in ICU; individualized SCPPopt derived; no lumbar drain | ICU monitoring ≤ 1 week; 2 wk.; 6–12 month outcomes | Feasibility of continuous SCPPopt visualization | Continuous determination of patient-specific SCPPopt feasible; supports individualized hemodynamic targets. |

| Squair 2017 (102) | Prospective cohort; N = 93 | Acute cervical and thoracic SCI; ASIA A–C | Lumbar intrathecal catheter (no CSF drainage) | MAP targeted (80–85 mmHg) 7 days; SCPP monitored | Discharge and 6-month outcomes | Association of SCPP with neurological recovery | Augmented SCPP associated with better motor recovery; evidence that perfusion matters clinically. |

| Squair 2019 (103) | Retrospective cohort; N = 107 | Acute cervical and thoracic SCI; ASIA A-D | ITP via lumbar catheter | Analyzed exposure to SCPP levels over first week | 6-month outcomes | Empirical SCPP target windows | SCPP 60–65 mmHg associated with ASIA improvement; extremes above/below associated with worse outcomes. |

| Hogg 2020 (105) | Prospective cohort; N = 13 | Acute SCI; cervical, thoracic, and conus; ASIA A–C | Concurrent lumbar CSF (ITP) catheter and injury-site ISP probe; microdialysis in subset | Concurrent ISP and lumbar CSF monitoring; intermittent CSF drainage to test ISP effects; lumbar CSF metabolites versus injury-site micro dialysate. | ICU monitoring ≤ 1 week; MRI at 2–3 months; 6 month outcomes | Correlation between lumbar CSF and injury-site ISP–derived SCPP; Effect of CSF drainage on ISP | Lumbar CSF pressure poorly reflected injury-site ISP and SCPP; lumbar drainage rarely reduced ISP; injury-site microdialysis values differed from lumbar CSF metabolites. |

| Yue 2020 (15) | Prospective Cohort; N = 15 | Acute cervical and thoracic SCI; ASIA A-D | Lumbar subarachnoid drain (LSAD) | LSAD within 24 h; SCPP monitored 5 days goal ≥65 mmHg; MAP not targeted separately; early surgical decompression in 14/15 patients | ICU monitoring for 5 days; ASIA at day 7 versus admission | Feasibility and safety of standardized SCPP-guided protocol; ASIA change | SCPP protocol was feasible and safe; all patients maintained mean SCPP ≥65 mmHg; no LSAD-related complications; at day 7, 33% overall and 50% of severe ASIA A–C patients improved ≥1 ASIA grade. |

SCPP-targeted monitoring and management in acute SCI.

Studies utilizing intrathecal (ITP) or intraspinal (ISP) pressure monitoring to calculate spinal cord perfusion (SCPP) pressure with associated protocols, outcomes, and key findings. SCPP, spinal cord perfusion pressure; SCPPopt, optimized spinal cord perfusion pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; ISP, intraspinal pressure; ITP, intrathecal pressure; sPRx, spinal pressure reactivity index; ICU, intensive care unit; ASIA, American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; LSAD, lumbar subarachnoid drain.

4.2.1 Monitoring intrathecal pressure as a measure of SCPP

ITP reflects the pressure of the CSF within the thecal sac (the subarachnoid space around the spinal cord). In acute SCI, cord swelling and impaired CSF circulation can elevate ITP, reducing SCPP and further worsening recovery. Monitoring and titrating ITP using a lumbar intrathecal catheter has been found to be safe and feasible in the acute setting (101). In a prospective trial, Kwon et al. (101) inserted lumbar CSF catheters in 22 patients within 48 h of SCI for continuous ITP monitoring with half receiving CSF drainage. They observed that the mean ITP was approximately 14 mmHg at insertion, rising to about 22 mmHg during surgical decompression, and often further increased post-operatively. Importantly, draining CSF dampened these ITP elevations without any significant complications. This study established proof-of-concept that lowering ITP via lumbar drainage can effectively improve SCPP in acute SCI and can be implemented with low risk. Subsequent studies have reinforced that SCPP is more predictive of neurologic recovery than MAP alone, further supporting the value of ITP monitoring (15, 102). One study analyzed 92 acute SCI patients with lumbar CSF monitors and found that time spent above an SCPP of 50 mmHg had a positive linear relationship with 6-month motor improvement (102). Further work showed that maintaining SCPP in the 60 to 65 mmHg range was associated with the greatest neurological improvement, whereas adherence to MAP targets was less predictive (103). Preclinical data support these ranges by showing that augmenting perfusion improved spinal cord blood flow and metabolism, but with diminishing returns and potential harm at excessive pressures depending on the vasopressor used (104). Further, Yue and colleagues (15) successfully implemented the use of a SCPP-guided therapy protocol utilizing a lumbar drain to monitor ITP. In their study of 15 acute SCI patients, they targeted a SCPP at or above 65 mmHg for 5 days instead of traditional MAP goals. No drain related complications occurred and one-third of patients showed improved ASIA grades by day 7, further suggesting an SCPP-guided approach is clinically feasible and may confer early neurological benefits. Together, these studies demonstrate the clinical utility of employing lumbar CSF catheters to monitor and augment SCPP to promote recovery after SCI with the potential to lessen the use of vasopressors. A key limitation of lumbar catheters is that they measure CSF pressure distal to the injury, which may underestimate true pressures at the lesion site in cases of severe spinal cord swelling from hemorrhage or edema (98, 99, 105). Nonetheless, monitoring ITP with lumbar catheters is generally safe, feasibly integrated into clinical settings, and provides insight into cord perfusion status that might be missed when solely relying on MAP monitoring (19).

4.2.2 Monitoring intraspinal pressure as a measure of SCPP

ISP refers to the pressure within the intradural space at the injury site measured via a probe placed under the dura, typically after surgical decompression. This technique was pioneered by the Injured Spinal Cord Pressure Evaluation (ISCoPE) studies and overcomes the limitation of ITP monitoring, which sometimes underestimates pressures at the site of injury (98, 99). In addition to providing proof-of-principle of this protocol, the work by Werndle and colleagues (98) showed that surgical decompression via laminectomy alone did not reliably reduce ISP and may even be detrimental by exposing the swollen spinal cord to further external compression forces. This finding motivated a subsequent study evaluating the use of expansion duroplasty (enlarging the dural sac) to further decrease ISP (106). Performing an expansion duroplasty in 10 patients after laminectomy decreased ISP and increased SCPP. This is just one example of how direct measurement of ISP can guide decisions in real time. Moreover, continuous ISP monitoring has enabled advanced insights into spinal cord hemodynamics (107). By concurrently recording MAP and ISP, investigators can calculate SCPP and spinal pressure reactivity index (sPRx) on a rolling basis, analogous to intracranial pressure monitoring in TBI (107). The sPRx is derived as the correlation between slow waves of ISP and MAP, where a positive correlation indicates impaired spinal blood flow autoregulation and a negative or zero relation suggests intact autoregulation. Using these techniques, Chen and colleagues (108) identified an optimal SCPP for each patient by finding the pressure that minimized sPRx. In their series of 45 patients with ISP monitors, the continuous optimal SCPP could be calculated about 45% of the time and was highly variable between individuals (108). Even within a single patient, the optimal SCPP shifted over hours to days, demonstrating a dynamic perfusion requirement. Importantly, time spent out of a patient’s optimal SCPP was associated with a decline in key metabolic markers and worsened neurologic outcomes. Patients that stayed within an average of 5 mmHg of their optimal SCPP had significantly greater ASIA grade improvement compared to those who did not. These findings provide compelling evidence that individualized SCPP goals, made possible using ISP monitoring at the injury site, can optimize neurological outcomes. Major limitations of ISP monitoring include its invasive nature requiring neurosurgical expertise with risk of further injury, specialized hardware, and continuous data capture and analysis, all of which limit its availability outside specialized centers (109, 110). Still, targeting ISP provides the most direct measure of the local pressure at the level of injury that has allowed for valuable insight advancing the use of SCPP-guided therapy in acute SCI.

4.2.3 Future of SCPP

Despite the advancements made in the use of targeting SCPP in acute SCI, detailed studies to guide its clinical implementation are still needed. Ongoing and upcoming clinical trials are poised to provide much needed data. A randomized controlled trial at UTHealth Houston has been launched to compare traditional MAP management versus SCPP-targeted care in acute SCI (“Monitoring spinal cord perfusion pressure in acute traumatic spinal cord injury”; Clinicaltrials.gov NCT06451133). This trial will be one of the first to test whether proactive SCPP optimization translates into superior recovery compared to MAP-driven care, and will also clarify the risks associated with each strategy. Complementing this, the Canadian-American SCPP and Biomarker Study (“CASPER”; Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03911492) is an ongoing multicenter trial investigating the effect of SCPP versus MAP on long-term outcomes. Both of these studies are utilizing lumbar catheterization to monitor and manipulate ITP to optimize SCPP. Together, this work will help determine whether ITP monitoring and SCPP-targeted treatment should become the standard of care and will guide future work in optimizing MAP and SCPP protocols.

4.3 Vasopressor selection

The immediate cardiovascular consequence of SCI is hypotension, and for this reason, targeting MAP and SCPP goals involves treatments designed to augment blood pressure, with initial management involving IV fluid resuscitation. When a patient remains hypotensive despite adequate fluid resuscitation, vasopressor therapy is initiated to augment systemic vascular resistance and raise blood pressure into the targeted MAP range (111). Vasopressors serve as pharmacological support to counteract the loss of sympathetic tone and maintain adequate spinal cord perfusion. Several vasopressors are available, but three are most commonly utilized in acute SCI: NE, dopamine (DA), and phenylephrine (PHE) (12, 79, 81, 112) (Table 5). Each agent has a distinct mechanism of action and hemodynamic profile, which informs its use in different clinical scenarios. Although all can effectively raise MAP, their differing affinities for α- and β-adrenergic (and dopaminergic) receptors lead them to exert unique effects on heart rate, cardiac output, and vascular tone (41, 113, 114). Further, these pharmacological differences translate to variable impacts on spinal cord perfusion and potential side effects. Thus, selecting an appropriate vasopressor requires balancing the desired hemodynamic effect with the drug’s risk profile, with particular attention to the possibility that treatment could have a harmful effect by driving MAP/SCPP outside of the optimal range (Table 6). Below, we compare NE, DA, and PHE in the context of acute SCI, focusing on their mechanisms, indications, outcomes, and complications.

Table 5

| Agent | Receptor profile | Hemodynamic action (MAP and CO) | Clinical notes | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norepinephrine | α1-dominant with β1 activity; minimal β2. | ↑MAP via ↑SVR; CO neutral to ↑ (β1). In acute SCI, maintains MAP with lower ISP and higher SCPP than dopamine. | Animal and clinical data: norepinephrine improved SCBF/PO2 versus phenylephrine post-decompression in pigs; early post-injury rat infusion increased hemorrhage size; lower arrhythmia burden versus dopamine in ICU shock trials. | Altaf 2017 (120); Soubeyrand 2014 (62); Streijger 2018 (119); Cheung 2020 (70); De Backer 2010 (114); De Backer 2012 (113) |

| Phenylephrine | Selective α1 agonist. | ↑MAP via ↑SVR; CO may ↓ due to ↑afterload and reflex bradycardia. | Porcine SCI: lower SCBF and PO2 after decompression and greater hemorrhage than control; generally chosen when tachyarrhythmia precludes β1 effects. | Streijger 2018 (119); Ko 2024 (128) |

| Dopamine | Dose-dependent: D1/D2 (1–3 μg/kg/min) → vasodilation; β1 (3–10) → ↑HR/contractility; α1 (>10) → vasoconstriction. | At moderate doses ↑CO; at high doses ↑MAP. In acute SCI cross-over, higher ISP and lower SCPP versus norepinephrine at similar MAP. | Higher risk of arrhythmias and worse outcomes versus norepinephrine in shock RCTs/meta-analyses; may be reserved when strong inotropy is required and arrhythmia risk acceptable. | Altaf 2017 (120); Readdy 2015 (124); Inoue 2014 (112); De Backer 2010 (114); De Backer 2012 (113); Agarwal 2023 (125) |

Common vasopressors used to augment MAP in acute SCI.

Receptor profile, hemodynamic effects, and clinical considerations of norepinephrine, phenylephrine, and dopamine in acute spinal cord injury. MAP, mean arterial pressure; SCI, spinal cord injury; CO, cardiac output; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; SCBF, spinal cord blood flow; PO₂, oxygen tension; LOS, length of stay; RCT, randomized controlled trial; HR, heart rate.

Table 6

| Source | Model | Design | Vasopressor(s) | MAP protocol | Primary outcome | Perfusion effect | Hemorrhage | Safety profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soubeyrand 2014 (62) | Rat T9 contusion | Preclinical; randomized; N = 35 | Norepinephrine | Dose infusion (no MAP target reported) | SCBF measured by laser Doppler; microvascular flow near lesion edge | NE transiently increased SCBF proximally but was not sustained | Increased parenchymal hemorrhage versus control | Suggests early NE can worsen hemorrhage |

| Streijger 2018 (119) | Porcine T10 contusion-compression | Randomized; N = 22 | Norepinephrine versus phenylephrine | Augment MAP by 20 mmHg above baseline | Spinal cord RBC flux and PbtO2 | NE increased RBC flux and PbtO2; PE decreased microvascular flow despite MAP ↑ | Not reported | Adverse systemic effects not assessed |

| Cheung 2020 (70) | Porcine thoracic contusion | Preclinical; N = 16 | Norepinephrine | MAP titrated (~50 → 110 mmHg) post-injury | SCBF (RBC flux) and microvascular oxygenation | SCBF and oxygenation rose linearly with MAP up to ~100–110 mmHg; regional heterogeneity noted | Not increased during step-ups | NE infusion improved perfusion but increased hemorrhage risk in some conditions. |

| Altaf 2017 (120) | Human acute SCI ICU | Prospective cross-over; N = 11 | Norepinephrine versus dopamine | Clinical MAP maintenance ≥85–90 mmHg | SCPP via lumbar subarachnoid catheter | NE increased SCPP and reduced ISP versus dopamine | Not reported | DA caused tachycardia → arm terminated; NE favored for microcirculation |

| Readdy 2015 (124) | Human ATCCS | Retrospective cohort; N = 34 | Dopamine versus phenylephrine | Maintain MAP ≥85 mmHg for up to 7 days | Clinical outcomes; complications | Not applicable | Not reported | Dopamine associated with more CV complications versus phenylephrine in older patients |

| Readdy 2016 (126) | Human SCI (penetrating versus blunt) | Retrospective cohort; N = 36 | Dopamine and phenylephrine | Maintain MAP ≥85 mmHg; mean ~101–124 h exposure | Complications by agent/mechanism | Not applicable | Not reported | Dopamine linked to more cardiogenic complications; phenylephrine fewer events |

| Agarwal 2023 (125) | Elderly (≥ 65 years) human SCI | Prospective registry; N = 40 | NE, PE, VP, DA, Dob, Epi | Maintain MAP ≥85 mmHg | Complications, LOS, mortality | Not applicable | Not reported | Norepinephrine use associated with more CV complications; caution in elderly |

| Ko 2024 (128) | Rat cervical SCI | Preclinical randomized; N = 48 | Norepinephrine and phenylephrine | Pressor infusion to raise MAP; decompression timing examined | Intraspinal pressure, microvascular leakage | Pressors increased MAP; but exacerbated microvascular extravasation without decompression | Decompression reduced vasopressor induced spinal hemorrhage and extravasation | Pair hemodynamic therapy with decompression to mitigate bleeding risk |

| Hashemaghaie 2025 (127) | Human acute SCI | Retrospective cohort; N = 277 | Norepinephrine; dopamine, and phenylephrine | MAP ≥85 mmHg; early versus non-early pressor initiation compared | Clinical outcomes; complications; LOS | Not applicable | Not reported | Early pressor use not clearly associated with improved outcomes; cardiovascular events frequent |

Vasopressor agents in acute SCI.

Preclinical and clinical studies examining vasopressor use, hemodynamic protocols, perfusion effects, and safety outcomes. MAP, mean arterial pressure; SCI, spinal cord injury; SCBF, spinal cord blood flow; PbtO₂, partial pressure of tissue oxygen; ISP, intraspinal pressure; SCPP, spinal cord perfusion pressure; NE, norepinephrine; PE, phenylephrine; DA, dopamine; Dob, dobutamine; Epi, epinephrine; VP, vasopressin; ATCCS, acute traumatic central cord syndrome; CV, cardiovascular; RBC, red blood cell.

4.3.1 Norepinephrine

NE is widely considered the first-line vasopressor for acute SCI due to its balanced adrenergic activity and favorable safety profile (14, 15, 111, 112). NE is a potent α1 adrenergic agonist with modest β1-adrenergic effects. This results in strong peripheral vasoconstriction, with a mild increase in heart rate and contractility (115, 116). In the setting of SCI-induced vasodilation and bradycardia, NE effectively counteracts hypotension while providing inotropic support, a useful combination in neurogenic shock (79, 81). Across comparative literature, NE is associated with fewer tachyarrhythmias and myocardial complications than DA in shock states, supporting its preference (81, 113, 114, 117, 118). Preclinical SCI work also suggests NE improves spinal cord blood flow and tissue oxygenation more than PHE at equivalent pressure targets, supporting a physiological advantage (119). In addition, NE was able to maintain target MAP levels with a lower ITP and a correspondingly higher SCPP when compared with DA in a study of 11 SCI patients (120). However, there have also been some detrimental effects of NE use in preclinical studies. Early NE treatment during persistent cord compression was also found to increase intraparenchymal hemorrhage despite improving tissue oxygenation in a porcine SCI model (70). This highlights the importance of the timing of vasopressor initiation in relation to decompression. Another preclinical study in rats reported NE increased spinal hemorrhage without improving perfusion (62). Nonetheless, NE provides effective MAP support with relatively fewer cardiac side effects, solidifying its role as the preferred vasopressor in acute SCI (81). Yet, it still requires careful titration and monitoring. Caution is also advised in patients with peripheral vascular disease, as NE’s intense peripheral vasoconstriction can compromise distal circulation, but in most SCI scenarios the benefits of improved perfusion outweigh this concern (116, 121).

4.3.2 Dopamine

DA is an endogenous catecholamine with dose-dependent receptor effects (41, 116, 122): Low doses (≤ 5 ug/kg per min) stimulate D1/D2 dopaminergic receptors in the renal and mesenteric beds causing vasodilation resulting in reduced systemic vascular resistance. At intermediate doses (5–10 ug/kg per min), DA predominantly engages β1 adrenergic receptors increasing heart rate and contractility. Using high doses (> 10 ug/kg per min) activates α1 adrenergic receptors producing systemic vasoconstriction. In the acute SCI and other shock states, low-dose DA can be counterproductive by lowering systemic vascular resistance, while higher doses required to maintain MAP are consistently associated with tachycardia and arrhythmias (113, 114, 118, 123). Historically, DA was widely considered the first line in MAP maintenance after SCI. However, mounting evidence underscoring its higher risk of adverse effects compared to PHE and NE has reduced its use, especially in older populations (90, 112, 124, 125) and those with penetrating trauma (126).

4.3.3 Phenylephrine

PHE is a selective α1 adrenergic agonist that increases systemic vascular resistance and arterial pressure with negligible direct β1 stimulation. Reflex bradycardia is common, and the resulting rise in afterload without inotropy can reduce stroke volume and cardiac output in susceptible patients (41, 116). These properties make PHE attractive when β-agonism is undesirable, for example in patients with tachyarrhythmias or myocardial ischemia. Yet, caution is warranted for those with baseline bradycardia, conduction disease, or marginal cardiac output. Several retrospective SCI cohort studies indicate PHE produced fewer cardiogenic complications when compared to DA (112, 124, 126). These data support favoring PHE over DA in most cases. A single clinical study has been performed comparing NE to PHE outcomes in acute SCI (127), which reports NE was more likely to lead to adverse effects compared to PHE. However, NE was more frequently selected in patients with severe injuries, possibly confounding their results. Still, this highlights the need for further investigation. In a preclinical porcine SCI model, PHE was found to increase intraparenchymal hemorrhage relative to controls receiving no vasopressor support (119). Rodent studies reinforce the importance of timing vasopressor initiation relative to decompression surgery as discussed in the NE section. Initiating PHE within minutes of cervical injury increased hemorrhage and BSCB extravasation, whereas decompression mitigated this effect (128). More clinical work is necessary to definitively recommend NE over PHE, but for now, evidence favors NE as first line to support spinal cord perfusion.

4.3.4 Vasopressor limitations

Overall, it must be emphasized that vasopressor therapy, even when successful in achieving MAP targets, has inherent limitations. Vasopressor use, especially when reaching supraphysiological levels of blood pressure, contributes to exacerbated secondary injury processes that can undermine recovery (62, 70, 74, 89, 91, 95, 119, 128). Further, the adverse effects due to the pharmacological profile of the vasopressors themselves can be detrimental and even lethal. While vasopressors remain essential in acute SCI care to manage hemodynamic instability, their use is a double-edged sword. The challenge of preserving spinal cord perfusion without exacerbating injury motivates the search for alternative therapeutic strategies. The use of lumbar catheters to drain CSF to lower ITP and increase SCPP shows promise (15, 101).

4.4 Neuromodulatory interventions for hemodynamic control

Conventional hemodynamic management in acute SCI primarily treats the manifestations of a disrupted autonomic system with vasopressors and related measures, rather than restoring autonomic function itself. Neuromodulation offers an alternative that aims to re-engage disrupted spinal circuitry by electrically recruiting somatoautonomic pathways below the lesion to restore autonomic output (129, 130). This has been well documented to be effective in chronic SCI with much work focusing on improving volitional limb movements and recovery of motor functions (131–136). More recently, several groups have applied this principle to treat cardiovascular dysfunction and maintain hemodynamic stability in chronic SCI patients with beneficial effects persisting even after cessation of treatment (137, 138) (Table 7). This early evidence justifies further investigation into neuromodulatory techniques as a potential therapeutic strategy to manage hemodynamic instability in acute SCI with the aim of reducing vasopressor dependence and mitigating long-term cardiovascular deterioration by restoring autonomic regulation. Here, we review both invasive and non-invasive neuromodulatory techniques for acute SCI hemodynamic management from preclinical models and emerging clinical studies.

Table 7

| Source | Design | Technique | Population | Protocol | Timeline | Primary outcome | Key finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phillips 2018 (148) | Prospective case series; N = 5 | Open-loop tSCS at T7–T8 | Chronic cervical and thoracic SCI; ASIA A/B | Acute stimulation during head-up tilt testing; 30 Hz, 1 ms biphasic pulses; current titrated 10–70 mA | Single-session tilt testing | Beat-by-beat BP, dP/dt, cerebral blood flow, symptoms | BP, cardiac contractility, and cerebral blood flow normalized within ~60 s; symptoms resolved; absence of leg EMG supported sympathetic recruitment. |

| Harkema 2018 (138) | Prospective case series; N = 4 | Open-loop epidural SCS (lumbosacral paddle); CV-targeted programs (CV-scES) | Chronic cervical SCI | Configurations chosen to raise MAP into 110–120 mmHg without motor activation | Repeated sessions over several weeks | MAP, SBP/DBP, HR stability across sessions | Repeated CV-scES sessions improved BP stability and introduced mapping for cardiovascular targets. |

| Squair 2021 (140) | Prospective first-in-human proof-of-concept; N = 4 | Closed-loop epidural SCS with beat-to-beat MAP feedback | Chronic high-level SCI | Controller adjusts stimulation of T10–T12 posterior roots to maintain user-defined MAP during orthostasis and AD | Acute repeated sessions | MAP control during tilt and AD provocation; sympathetic microneurography; plasma norepinephrine | Closed-loop control maintained MAP in real time, prevented BP collapse during tilt, and increased sympathetic activity/norepinephrine. |

| Peters 2023 (145) | Prospective protocol development study; N = 10 | Systematic tSCS mapping (T7/8, T9/10, T11/12, L1/2) | Chronic SCI with low seated SBP | 30 Hz, 1 ms pulse width, 5 kHz carrier; amplitude increased in 5 mA steps; Standardized SBP targets set at 110–120 mmHg (men) or 100–120 (women) | Single-session mapping visit | Feasibility and safety; SBP change; symptom tracking | Mapping identified reproducible, individualized tSCS parameters for BP stabilization. |

| Engel-Haber 2024 (149) | Prospective case series; N = 8 | tSCS mapping across cervical to sacral sites | Chronic cervical SCI with BP instability | 30 Hz, 1 ms pulse width, 5 kHz carrier; 5 mA step-ups to ~120 mA; compare vertebral levels | Single-session mapping visit | Beat-to-beat change in SBP (calibrated to brachial), DBP, and HR | Lumbosacral (L1/2–S1/2; incl. T11/12) stimulation consistently elevated SBP, whereas cervical/upper thoracic did not, supporting caudal targeting |

| Hofstoetter 2018 (147) | Mechanistic study; N = 20 (prospective tSCS, retrospective eSCS) | tSCS versus eSCS | Chronic SCI; motor-incomplete and complete | Evoke posterior-root muscle reflexes; tSCS via paravertebral electrodes (30 Hz, 1 ms, 5 kHz); eSCS via percutaneous lumbar leads; responses compared with EMG | Single-session testing | Reflex latencies, recruitment curves, and post-activation depression of posterior-root muscle (PRM) reflexes | Both tSCS and eSCS activated common posterior-root afferents; near-identical EMG waveforms confirmed mechanistic overlap. |

| Shackleton 2023 (146) | Prospective RCT protocol; N = 12 planned | Neuromodulation + intensive exercise versus exercise alone | Chronic SCI | Program includes neuromodulation sessions targeting motor and autonomic function | 8-week training program | Composite motor outcomes; autonomic outcomes (BP stability) as secondary | Defines trial framework to test combined neuromodulation and exercise effects on BP stability. |

Neuromodulation strategies that modulate arterial pressure after SCI.

Prospective and mechanistic studies using transcutaneous (tSCS) or epidural (eSCS) stimulation approaches to stabilize blood pressure in individuals with SCI. tSCS, transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation; eSCS, epidural spinal cord stimulation; CV-scES, cardiovascular-targeted epidural spinal cord stimulation; AD, autonomic dysreflexia; MAP, mean arterial pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; ASIA, American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale; BP, blood pressure; RCT, randomized controlled trial; T, thoracic; L, lumbar; EMG, electromyography; dP/dt, rate of rise of ventricular pressure; PRM, posterior-root muscle.

4.4.1 Invasive neuromodulation: epidural spinal cord stimulation