Abstract

Background:

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic, progressive autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation of the axial skeleton. Although acupuncture has been investigated as a potential therapeutic option for symptom relief, its efficacy in AS remains inconclusive. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of acupuncture for patients with AS, aiming to generate evidence to inform clinical practice.

Methods:

This study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement. A literature search was performed across 7 databases to identify articles published up to December 25, 2024. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that met the eligibility criteria were included. The methodological quality of the included trials was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (RoB 2.0), and meta-analyses were conducted with RevMan 5.4 software. If high heterogeneity was observed among the included studies, a random-effects model was used for data synthesis. Subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses were performed when necessary.

Results:

A total of 35 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) met the inclusion criteria of this study. We used 6 indicators to estimate the results of the meta-analysis, all outcomes showed statistically significant improvements, including BASDAI score, BASFI score, ASDAS, VAS score, CRP level, and ESR level. Specifically, the BASDAI score (MD = −1.55, 95% CI: −1.97 to −1.13, p < 0.0001), BASFI score (MD = −1.47, 95% CI: −1.76 to −1.19, p < 0.0001), and ASDAS (MD = −0.57, 95% CI: −0.82 to −0.33, p < 0.0001). VAS score (MD = −1.30, 95% CI: −1.54 to −1.06, p < 0.0001), CRP level (MD = −7.12, 95% CI: −8.68 to −5.56, p < 0.0001), and ESR level (MD = −7.22, 95% CI: −9.13 to −5.32, p < 0.0001) all decreased significantly. Moreover, no serious acupuncture-related adverse events were reported across the 35 RCTs (only mild, transient reactions in a few cases).

Conclusion:

Acupuncture (including electroacupuncture, warm acupuncture, and fire acupuncture, etc.) is an effective and safe treatment for AS. However, the evidence base is limited by substantial heterogeneity and the lack of large-scale, high-quality clinical trials. Future research should focus on high-quality multicenter studies and comparative analyses of different acupuncture modalities to optimize the evidence for acupuncture in AS treatment.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, identifier CRD42025633263.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is an inflammatory rheumatic disease that affects the axial skeleton and is characterized by inflammatory back pain (1, 66). AS is one of the five spondyloarthritis subtypes (the others: psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, spondyloarthritis with inflammatory bowel disease, undifferentiated spondyloarthritis) and is classified as a rheumatic immune disease (2). AS has an insidious onset and lacks specific symptoms in the early stage (3). With the progression of sacroiliac joint and axial skeleton inflammation, patients gradually develop chronic inflammatory low back pain, accompanied by morning stiffness and fatigue (4). Worsening spinal inflammation causes spinal stiffness and reduced mobility. Some patients may also have hip, knee, ankle, or shoulder swelling; the eyes are often involved, such as in acute anterior uveitis (5). AS affects approximately 0.1–0.5% of the global population, primarily young adults around 26 years old, with a higher prevalence in males (6).

The etiology of this disease remains unclear, but it exhibits obvious familial aggregation and a strong genetic association, with HLA-B27 serving as a key susceptibility gene (6, 7). At present, there is no clear cure for the disease, and clinical management focuses on controlling inflammation, relieving acute symptoms, and improving spinal function (8). The commonly used western medicines are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (9, 10). However, current western therapies for AS only alleviate symptoms, requiring long-term use with high relapse risks, heavy economic burden, and notable side effects (11): long-term NSAIDs increase gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal damage risks; conventional DMARDs act slowly with limited efficacy on axial symptoms (4, 65).

In recent years, with the continuous development and innovation of TCM techniques, acupuncture, as a safe and effective complementary therapy, has increasingly demonstrated its unique advantages in the treatment of systemic autoimmune diseases (12). In particular, it has provided novel insights and practical approaches for managing AS, a clinically intractable disease (13). Notably, the reason why these acupuncture methods can be effective in AS treatment lies in their adherence to the TCM principle of syndrome differentiation and treatment (14), combined with precise acupoint selection based on the individual disease conditions of AS patients. This ultimately achieves a multi-targeted and multi-pathway comprehensive regulatory effect: it not only regulates the body’s immune function and metabolic levels but also alleviates the core symptoms of patients through anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects (14, 15).

Given the scattered clinical evidence and lack of systematic reviews on acupuncture for AS, this study is necessary to summarize existing evidence via meta-analysis to clarify acupuncture’s efficacy and safety. This study systematically reviews current evidence to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of acupuncture in treating AS. It further explores the mechanisms of action of various acupuncture therapies, as well as existing limitations and potential areas for improvement, aiming to provide evidence for the acupuncture treatment of AS.

Methods

This review was registered in PROSPERO (ID CRD42025633263) on January 7, 2025. At the study’s initiation, we predefined three primary outcomes (BASDAI, BASFI, ASDAS) and designated VAS, CRP, and ESR as secondary outcomes. The review was conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines.

Data sources

In accordance with the Cochrane Handbook, we systematically searched PubMed, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), as well as the Chinese databases China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang, and VIP, from their inception to December 25, 2024. For the English-language databases, searches were conducted using a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free-text terms related to ankylosing spondylitis and acupuncture interventions, applied to the title and abstract fields, with MeSH terms used where applicable. The search terms were then translated into Chinese and used to search the Chinese-language databases. All retrieved records were imported into Zotero for de-duplication.

Study selection

During study selection, we did not exclude trials based on methodological quality (e.g., randomization, allocation concealment, blinding). We included (a) Study design: randomized controlled trials (RCTs); (b) Participants: patients diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis (AS); (c) Experimental intervention: acupuncture therapies, including traditional needling, electroacupuncture, warm needling, fire needling, acupotomy, and related modalities; (d) Control intervention: sham acupuncture, conventional Western medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, or three-arm trials in which acupuncture could be treated as an independent comparison; (e) Outcomes: reporting at least one predefined outcome indicator. We excluded studies that: (a) were not RCTs; (b) did not target AS or only reported outcomes related to comorbidities; (c) evaluated traditional Chinese medicine therapies other than acupuncture or moxibustion; (d) did not provide outcome data on the efficacy of acupuncture for AS; (e) lacked accessible full-text data.

Primary outcome indicators:

-

BASDAI (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index).

-

BASFI (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index).

-

ASDAS (Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score).

Secondary outcome indicators:

-

VAS (Visual Analogue Scale).

-

CRP (C-reactive protein).

-

ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate).

Methodology quality assessment and data extraction

Two reviewers (JZ, SS) independently conducted literature screening. Any discrepancies arising at any screening stage were resolved through in-depth discussion with a third independent researcher (RB), followed by the extraction of data on: (a) author and publication year; (b) sample size; (c) details of interventions (acupuncture type, acupoints, treatment duration, single treatment duration) for treatment and control groups; (d) outcome measures; (e) adverse events. All information is recorded in Table 1.

Table 1

| First author (year) | Type of acupuncture | Sample sizes | Interventions | Acupuncture points selection | Single treatment duration | Treatment duration | Main outcomes | Adverse events | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | C | T | C | |||||||

| Wang Fei 2017 (27) | Acupuncture | 36 | 36/36 | Acupuncture+TCM | TCM/Western medicine | DU3, DU14, DU8, DU9, BL23, DU2, GB24 | 30 min | 3 weeks | BASDAI, VAS, BASFI, CRP, ESR | Nausea, anorexia, fever, dermatitis, palpitations, dizziness, and abdominal pain |

| Chen Xin 2018 (50) | Electroacupuncture | 54 | 54 | Electroacupuncture | Conventional Western Medicine | C1-L5, BL23, DU14, BL11, BL18 | 30 min 2 Hz | 13 weeks | VAS, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Thanakorn Theerakarunwong 2021 (26) | Du Mai Pai Zhen Method | 31 | 30/32/30 | Du Mai Pai Zhen Method+TCM | Acupuncture/Du Mai Pai Zhen Method/TCM | BL11, DU12, DU3, EX-B2 | 30 min | 4 weeks | BASDAI, VAS, BASFI, CRP, ESR | Nausea, vomiting, belching |

| Zhuang Yu (38) | Warm Acupuncture | 35 | 35 | Warm Acupuncture | Western medicine | DU20, DU16, DU14, DU12, DU4, DU3, DU1 | 40 min | 5 weeks of treatment over 10 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Chen Yutao (19) | Silver needles | 15 | 15/15 | Acupuncture | TCM/Acupuncture+TCM | n.r. | n.r. | 12 weeks | BASDAI | n.r. |

| Gao Lixin (42) | Fire Acupuncture | 31 | 31 | Western medicine+Fire Acupuncture | Western medicine | Du3, BL18, BL23, ST36, SP6 | n.r. | 12 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Zheng Yimin (14) | Warm Acupuncture | 35 | 35 | Warm Acupuncture+Western medicine | Western medicine | SP16, SP15, SP14, SP9, GB34, ST36, ST37, ST40 | 60 min | 4 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP, ESR, ASDAS | Abdominal distension, diarrhea |

| Wang Yingjie 2017 (40) | Floating needle | 40 | 40 | Floating needle | Western medicine | Lower back, buttocks | 30 min | 24 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI | n.r. |

| Guo Chunliang 2024 (47) | Exercise needles | 47 | 47 | Exercise needles+Western medicine+Tuina | Western medicine+Tuina | KI6, BL62 | n.r. | 32 weeks | BASDAI, VAS, BASFI, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Wu Jia 2023 (48) | Exercise needles | 39 | 39 | Exercise needles+Western medicine | Western medicine | KI6, BL62 | 20 min | 3 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP | Vomiting, abnormal liver function |

| Liu Biyan 2019 (23) | Acupuncture | 40 | 40 | Western medicine+Acupuncture | Acupuncture | EX-B2, BL23, BL25, BL54, GB30, BL40 | 30 min | 8 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP | n.r. |

| Gao Taozhen 2019 (29) | Warm Acupuncture | 20 | 20 | Western medicine+Warm Acupuncture | Western medicine | EX-B2 | 30 min | 4 weeks | BASFI, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Luo Yuxuan 2024 (24) | Acupuncture | 30 | 30 | Western medicine+Acupuncture | Western medicine | DU20, DU14, HT7, BL23, BL18, DU3, GB34, SP6 | 30 min | 4 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Huang Yongjie 2016 (22) | Acupuncture | 43 | 43 | Western medicine+Acupuncture | Western medicine | SP6, BL40, LI15, LI4, LI11, LI10 | 30 min | 5 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Dai Chaoran 2020 (51) | Electroacupuncture | 29 | 29 | Electroacupuncture+Western medicine | Western medicine | BL10, BL11, DU14, BL27, BL32, SJ5, GB34, EX-B2 | 30 min, 1–2 mA 2 Hz | 2 weeks | BASDAI, VAS, BASFI, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Yang Lihua 2020 (34) | Warm Acupuncture | 34 | 34 | Warm Acupuncture | Western medicine | DU14, GB20, BL11, BL23 | 30 min | 8 weeks | VAS, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Wang Junren 2013 (33) | Warm Acupuncture | 30 | 30 | Acupuncture | Western medicine | EX-B2, DU2, DU14, DU1, DU5, BL40, BL18 | 30 min | 12 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP, ESR, VAS | n.r. |

| Zhou Shaohui 2011 (37) | Warm Acupuncture | 28 | 28 | Warm Acupuncture+Western medicine | Western medicine | DU14, BL11, BL18, BL23, EX-HN14 | 30 min | 3 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Wang Zhengrong 2022 (44) | Needle knives | 40 | 40 | Needle knives+Western medicine | Western medicine | Lumbosacral, Abdominal regions | n.r. | 8 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Lin Bo 2023 (31) | Warm Acupuncture | 40 | 40 | Warm Acupuncture+Herbal Fumigation | Herbal Fumigation | DU20, DU16, DU14, DU12, DU4, DU3, DU1 | 40 min | 12 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP, ESR, VAS | skin allergies, subcutaneous hematoma, nausea and vomiting |

| You Yuquan 2020 (46) | Needle knives | 30 | 30/30 | Needle knives | Needle knives+Western medicine/Western medicine | sacroiliac joint | n.r. | 24 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Huang Wenchao 2024 (30) | Warm Acupuncture | 26 | 26 | Western medicine+Warm Acupuncture | Western medicine | SP16, SP15, GB34, SP9, ST36, ST40, ST37 | 60 min | n.r. | BASFI | n.r. |

| Ye Lei 2022 (35) | Warm Acupuncture | 30 | 30 | Western medicine+Warm Acupuncture | Western medicine | BL23, BL26, BL28, GB29, GB30 | 30 min | 5 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, VAS | n.r. |

| Zhao Mingyang 2023 (28) | Acupuncture | 30 | 30 | Western medicine+Acupuncture | Western medicine | TSBh1-8910, RFh1-6, RFh2-6, DXh2-6811, DNsz, DWSg, DZBh1-5 | 30 min | 4 weeks | BASDAI, VAS, CRP, ESR | C: Gastrointestinal upset |

| Gao Shouyuan 2019 (20) | Acupuncture for Tonifying the Kidney | 32 | 32 | Acupuncture | Western medicine | DU14, BL18, BL20, DU4, BL23, ST36, SP6, KI3 | 30 min | 6 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, VAS | n.r. |

| Wang Dongzhi 2020 (15) | Warm Acupuncture | 30 | 30 | Moxibustion supervision+Warm Acupuncture | Moxibustion supervision | n.r. | 60 min | 22 weeks | CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Luo Xiaoguang 2022 (32) | Warm Acupuncture | 40 | 40 | Proprietary chinese medicines +Warm Acupuncture | Proprietary chinese medicines | BL22, BL23, RN6, BL25, RN4, BL29, BL30 | n.r. | 8 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP, ESR, VAS | n.r. |

| Li Xinxian 2015 (52) | Bee needles | 30 | 30 | Bee needles+Electroacupuncture | Electroacupuncture | EX-B2, BL28, BL23, DU16, DU14, BL13, BL67, BL25, DU3 | n.r. | 4 weeks | BASDAI, ASDAS, CRP, ESR, VAS | n.r. |

| Zeng Yufen 2017 (41) | Floating needle | 48 | 50 | Floating needle+TCM | Western medicine+TCM | MTrP | 10 min | 3 weeks | VAS | n.r. |

| Zeng Wenbi 2018 (43) | Fire needle | 23 | 23 | Western medicine+Fire needle | Western medicine | BL13, BL14, BL15, BL18, BL19, BL20, BL22, BL.23, BL25, BL28 | 5 min | 4 weeks | VAS | n.r. |

| Shi Wencai 2020 (25) | Acupuncture | 30 | 30/30 | Western medicine+TCM + Acupuncture | Western medicine+TCM/Western medicine | BL11, DU14, BL18, BL23 | 30 min | 8 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI, CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Wang Zhaoyi 2022 (45) | The meridian puncture method | 49 | 49 | The meridian puncture method+Western medicine | Western medicine | Foot sun meridian tendon junction lesions | 30 min | 8 weeks | CRP, ESR | n.r. |

| Hou Haikun 2021 (21) | Wen yang Tong Du needlezy | 49 | 49 | Wen yang Tong Du needle+Inner heat needle | Inner heat needle | KI3, KI1, SP9, GB34, DU20, GB21 | 30 min | 4 weeks | BASFI, CRP, ESR, VAS | n.r. |

| Zhang Le 2017 (36) | Warm acupuncture | 30 | 31 | Western medicine+Warm acupuncture | Western medicine | BL23, DU4, BL40, GB30, DU3 | n.r. | 2 weeks | ESR | n.r. |

| Lu Zhishu 2024 (39) | Floating needle | 34 | 34 | Western medicine+Floating needle | Western medicine | MTrP | 240 min | 8 weeks | BASDAI, BASFI | Subcutaneous hematoma, skin rash, dyspepsia |

Baseline characteristics of included RCTs on acupuncture for ankylosing spondylitis.

T, treatment group; C, control group; n.r., not reported; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; ASDAS, ASAS Spondyloarthritis Disease Activity Score; TCM, Traditional Chinese Medicine.

We used the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool to assess the risk of: (a) bias in random sequence generation; (b) bias in allocation concealment; (c) performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel); (d) detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment); (e) attrition bias (incomplete outcome data); (f) reporting bias (selective reporting); and (g) other biases, and then determine whether the type of risk is “high-risk” (H), “low-risk” (L), or “unclear-risk” (U) (16). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or through consultation with a third reviewer (RB).

Data analysis

If essential data were missing, we attempted to contact study authors for clarification. We used Review Manager (RevMan 5.4) for meta-analysis. For continuous outcomes, we pooled data as mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI); for dichotomous outcomes, we used relative risk (RR) with 95% CI. Heterogeneity was assessed with the I2 statistic (17). If there is significant heterogeneity among the included trials, a random-effects model will be used for pooled meta-analysis. If heterogeneity is high, subgroup analysis or sensitivity analysis will be applied to manage the data.

-

An I2 < 25% was considered low heterogeneity, in which case a fixed-effect model might be appropriate, and pooled results are relatively reliable.

-

I2 of 25–50% indicated moderate heterogeneity, and we explored potential sources of heterogeneity (e.g., subgroup analyses).

-

I2 ≥ 50% was considered high heterogeneity. In such cases, we applied a random-effects model and planned subgroup or sensitivity analyses. We also intended to explore the reasons for heterogeneity in the Discussion field (18).

Results

Retrieval results and document information

Initially, a total of 2,660 records were identified. After removing 860 duplicates (579 by software and 281 manually) and 1,465 irrelevant or ineligible records (non-RCTs, unrelated topics, etc.), 35 RCTs remained for meta-analysis. The specific information contained in these studies was summarized in Figure 1. Altogether, these studies included 2,591 AS patients, with individual sample sizes ranging from 40 to 123. Among the included studies, ten studies evaluated traditional manual acupuncture (19–28), twelve studies evaluated warm acupuncture (14, 15, 29–38), three studies evaluated floating acupuncture (39–41), two studies used fire acupuncture (42, 43), two studies used acupotomy (needle-knife) (44–46), two studies used exercise (kinetic) acupuncture (47, 48), two studies used electroacupuncture (49–51), one study used meridian needling (44, 45), and one study used bee venom acupuncture (52).

Figure 1

Flowchart of the literature review and selection process.

Among the included studies, five studies were three-arm trials, with TCM, Western medicine, and acupuncture used as mutual controls (19, 25–27, 46); three studies set acupuncture controls based on acupuncture intervention (21, 44, 45, 52); one study used TCM alone (41), and one study used Chinese patent medicine alone (32); one study added acupuncture control based on moxibustion (15), one study used TCM fumigation and washing therapy as the control (31), and one study set a control based on “tuina and Western medicine” (47); the remaining studies all used Western medicine as the control (e.g., NSAIDs or DMARDs), except for the studies using acupotomy. The common acupoints included BL23, BL25, DU14, EX-B2, DU4, and DU3, involving primarily the Governor Vessel (Du) and Bladder meridians, along with points from the Spleen and Gallbladder meridians.

Seven studies reported various adverse reactions (14, 26–28, 31, 39, 48), such as abdominal bloating, diarrhea, nausea, anorexia, fever, dermatitis, palpitations, dizziness, and abdominal pain. In addition, the detailed characteristics of each included study are presented in Table 1. Most reported adverse events occurred in participants receiving concomitant pharmacologic therapy and were unlikely to be directly caused by acupuncture. No trial reported a serious acupuncture-related adverse event, and the events attributable specifically to acupuncture (e.g., transient dizziness or localized discomfort) were mild and self-limiting. In terms of treatment delivery, acupuncture sessions typically lasted 30 min, with a small number of studies extending the duration to 40 min or 1 h (14, 15, 38, 39). In particular, the acupuncture time was not mentioned for the acupotomy therapy. Treatment duration ranged from 2 weeks to 32 weeks across studies.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias graph is presented in Figure 2, and the risk of bias summary is shown in Figure 3. Additionally, the summary of the risk of bias is documented in Table 2.

Figure 2

Assessment of cochrane risk of bias presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 3

Cochrane risk of bias summary for each included study.

Table 2

| Study (first author, year) | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessors | Incomplete outcome | Selective reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang Fei 2017 (27) | L | U | H | L | H | U | L |

| Chen Xin 2018 (50) | U | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| Thanakorn Theerakarunwong 2021 (26) | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Zhuang Yu 2023 (38) | H | U | H | L | L | L | L |

| Chen Yutao 2017 (19) | H | U | H | U | L | U | H |

| Gao Lixin 2018 (42) | H | U | H | L | H | L | L |

| Zheng Yimin 2023 (14) | L | U | H | L | L | L | L |

| Wang Yingjie 2017 (40) | H | U | H | L | H | U | L |

| Guo Chunliang 2024 (47) | H | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| Wu Jia 2023 (48) | L | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| Liu Biyan 2019 (23) | L | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| Gao Taozhen 2019 (20) | H | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| Luo Yuxuan 2024 (24) | L | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| Huang Yongjie 2016 (22) | H | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| Dai Chaoran 2020 (51) | L | L | H | L | H | L | L |

| Yang Lihua 2020 (34) | H | U | H | H | L | U | L |

| Wang Junren 2013 (33) | L | L | H | L | L | L | L |

| Zhou Shaohui 2011 (37) | L | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| Wang Zhengrong 2022 (44) | L | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| Lin Bo 2023 (31) | L | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| You Yuquan 2020 (46) | L | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| Huang Wenchao 2024 (30) | H | U | H | L | L | U | H |

| Ye Lei 2022 (35) | L | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| Zhao Mingyang 2023 (28) | H | U | H | L | L | L | L |

| Gao Shouyuan 2019 (29) | L | U | H | L | H | L | L |

| Wang Dongzhi 2020 (15) | L | U | H | H | H | U | H |

| Luo Xiaoguang 2022 (32) | L | U | H | L | L | U | L |

| Li Xinxian 2015 (52) | L | U | H | L | L | L | L |

| Zeng Yufen 2017 (41) | L | U | H | H | H | U | L |

| Zeng Wenbi 2018 (43) | H | U | H | H | L | U | L |

| Shi Wencai 2020 (25) | L | U | L | L | L | U | L |

| Wang Zhaoyi 2022 (45) | L | U | H | H | H | U | L |

| Hou Haikun 2021 (21) | L | U | H | L | H | U | L |

| Zhang Le 2017 (36) | L | U | H | H | L | L | L |

| Lu Zhishu 2024 (39) | H | U | H | L | L | U | L |

Risk of bias for the 35 included studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool.

“L”, a low risk of bias; “U”, the risk of bias is uncertain; “H”, a high risk of bias.

Selection bias

Among the 35 included studies, one study did not describe the randomization process (49, 50). Among the remaining studies, twelve studies did not used random number tables for randomization (19, 22, 28–30, 34, 38–40, 42, 43, 47) were judged to be at high risk of bias.

Only three studies described the method of random allocation; these studies were assessed as having low risk of bias because they achieved allocation concealment using sealed envelopes (26, 33, 51), while the other thirty-two studies either did not describe their allocation methods or performed random allocation based on admission order. Overall, most studies had a high risk of bias in terms of random sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Performance bias

Among the included RCTs, thirty-three studies were rated as having a high risk of performance bias because they did not provide sufficient information to demonstrate that blinding of participants or study personnel was implemented. In contrast, only two studies (25, 26) explicitly reported a plausible double-blinding procedure and were therefore not classified as high risk.

Detection bias

Among the 35 included studies, six studies (15, 34, 36, 41, 43–45) were considered at high risk of detection bias due to their reliance on simplistic or subjective outcome measures, such as single self-reported indicators, which may compromise the reliability of effect estimates. Furthermore, one study had a very small sample and provided insufficient detail regarding outcome assessment procedures; as a result, its detection bias was rated as “unclear” (19). These factors should be taken into account when interpreting the pooled results.

Attrition bias

Nine studies reported patient drop-outs (due to adverse events), so attrition bias was high in these (15, 20, 21, 27, 40–42, 44, 45, 51). The other studies reported no loss to follow-up, indicating low attrition bias. The remaining twenty-six studies had no data loss and were judged as low risk.

Reporting bias

Twenty-five studies did not provide information on trial registration or protocols, hence were judged “unclear” for reporting bias. Only ten studies that reported all expected outcomes were considered at low risk (14, 20, 26, 28, 33, 36, 38, 42, 51, 52). Registration information was not reported in most Chinese and English studies; therefore, the risk of reporting bias was mostly assessed as “unclear-risk.”

Other biases

One study was assessed as high risk of bias due to insufficiently disclosed information (30), and two studies were judged to have high risk of bias because details such as acupuncture points were not clearly specified (15, 19). No other sources of bias were apparent.

Primary outcome indicators

BASDAI score

Twenty-four studies (19, 20, 22–29, 31–33, 35, 37–40, 42, 44–47, 51, 52) reported the BASDAI scores after treatment, involving 777 patients in the treatment group and 774 patients in the control group. Considerable heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 96%), so a random-effects model was used. Despite the heterogeneity, all studies showed a direction of effect favoring acupuncture. The BASDAI score in the treatment group was lower than that in the control group (1,551 participants, MD = −1.55, 95% CI: −1.97 to −1.13, p < 0.0001), with a statistically significant difference (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Forest plot of BASDAI score.

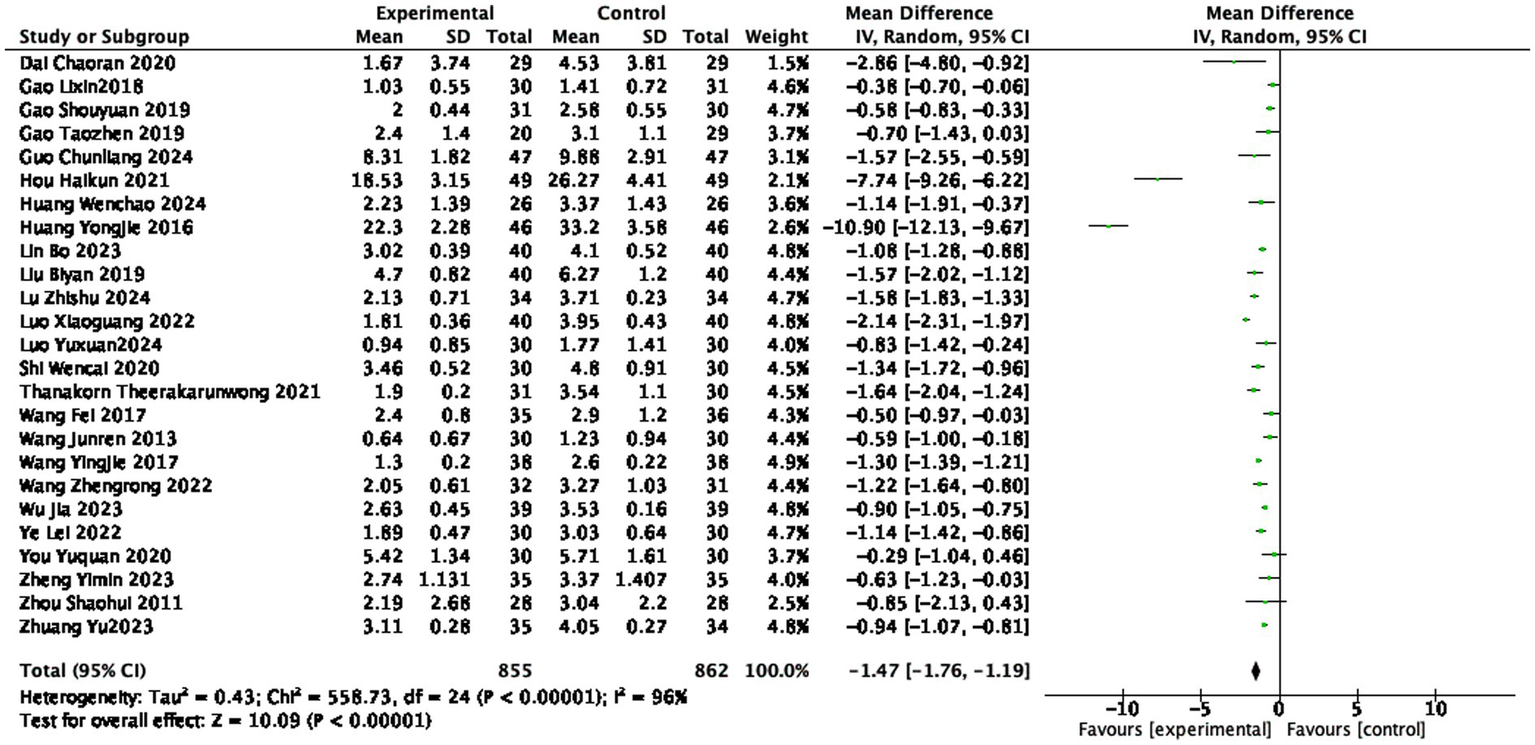

BASFI score

Twenty-five studies (14, 20–27, 29–33, 35, 37–40, 42, 44–48, 51) reported the BASFI scores after treatment, involving 855 patients in the treatment group and 862 patients in the control group. The heterogeneity is very high (I2 = 96%, random effect model), but the overall results show that acupuncture and moxibustion can significantly reduce the BASFI score. The BASFI score in the treatment group was lower than that in the control group (1,717 participants, MD = −1.47, 95% CI: −1.76 to −1.19, p < 0.0001), with a statistically significant difference (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Forest plot of BASFI score.

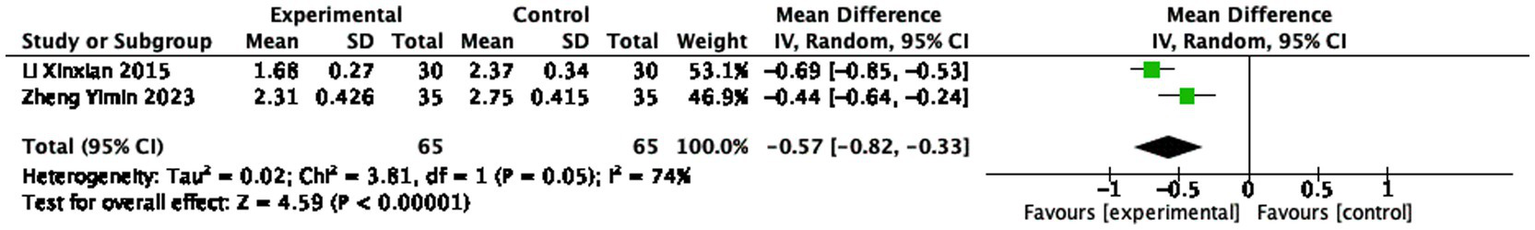

ASDAS

Two studies (14, 52) reported the ASDAS after treatment, involving 65 patients in the treatment group and 65 patients in the control group. The heterogeneity of the analysis was I2 = 74%, indicating statistically significant differences among the studies. The ASDAS in the treatment group was lower than that in the control group (130 participants, MD = −0.57, 95% CI: −0.82 to −0.33, p < 0.0001), with a statistically significant difference (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

Forest plot of ASDAS score.

Secondary outcome indicators

VAS score

Sixteen studies (20, 21, 26, 28, 31–35, 41, 43–45, 47, 49–52) reported the VAS scores after treatment, involving 577 patients in the treatment group and 575 patients in the control group. Heterogeneity was substantial (I2 = 87%, random-effects model), indicating statistically significant differences among the studies. The VAS score in the treatment group was lower than that in the control group (1,152 participants, MD = −1.30, 95% CI: −1.54 to −1.06, p < 0.0001), with a statistically significant difference (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

Forest plot of VAS score.

CRP level

Twenty-seven studies (14, 15, 21, 23–34, 37–39, 42, 44–52) reported the CRP level after treatment, involving 942 patients in the treatment group and 940 patients in the control group. Extremely high heterogeneity (I2 = 98%), using a random effects model, indicating statistically significant differences among the studies. The CRP level in the treatment group was lower than that in the control group (1882 participants, MD = −7.12 mg/L, 95% CI: −8.68 to −5.56, p < 0.0001, see Figure 8), with a statistically significant difference.

Figure 8

Forest plot of CRP score.

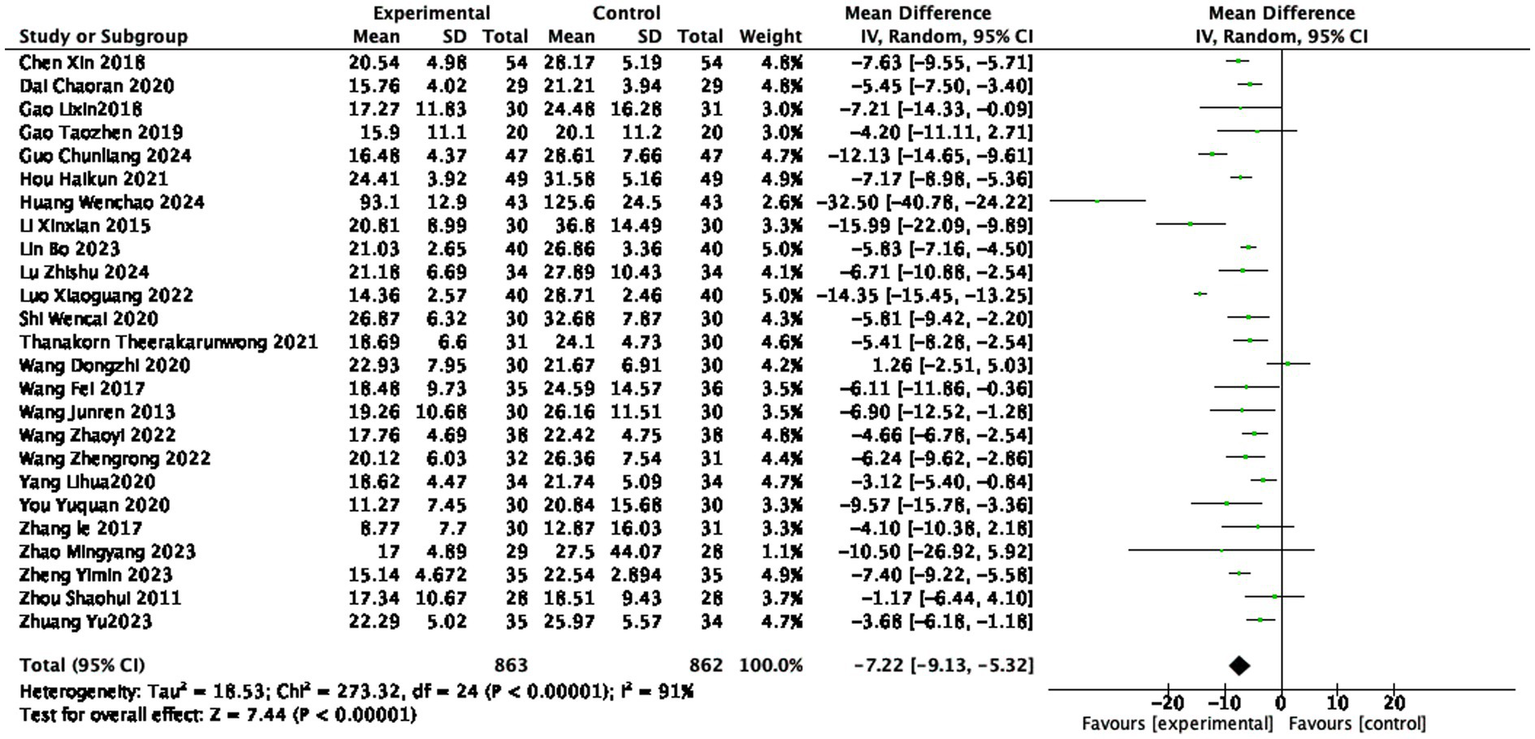

ESR level

Twenty-five studies (14, 15, 21, 25–34, 36–39, 42, 44–47, 49–52) reported the ESR level after treatment, involving 863 patients in the treatment group and 862 patients in the control group. The heterogeneity was very high (I2 = 91%, random effect). Indicating statistically significant differences among the studies. The ESR level in the treatment group was lower than that in the control group (1725 participants, MD = −7.22 mm/h, 95% CI: −9.13 to −5.32, p < 0.0001, see Figure 9), with a statistically significant difference.

Figure 9

Forest plot of ESR score.

Subgroup analysis

In this study, CRP was selected as the outcome for subgroup analysis because it was reported by the most studies, providing the largest sample size for analysis. Subgroup analyses were performed by different acupuncture types, each treatment duration, treatment frequency, and total course, with results detailed in Table 3. We found that significant differences in CRP results were observed across different acupuncture methods, intervention durations, and treatment cycles (detailed forest plots are available in Supplementary material 1).

Table 3

| Term | Category | Included studies | Results of heterogeneity assessment | Effect model | Meta-analysis results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | P | MD | 95%CI | P | ||||

| Intervention form | Acupuncture | 7 | 86% | p < 0.001 | Random | −3.65 | −4.97 to −2.32 | P < 0.001 |

| Warm acupuncture | 10 | 99% | P < 0.001 | Random | −12.16 | −18.77 to −5.56 | p < 0.001 | |

| Needle-knife therapy | 2 | 56% | p = 0.13 | Random | −4.24 | −8.27 to −0.21 | p = 0.04 | |

| Fire acupuncture | 1 | n.r. | n.r. | Random | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | |

| Floating needle | 1 | n.r. | n.r. | Random | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | |

| Exercise-acupuncture | 2 | 99% | P < 0.001 | Random | −3.72 | −13.51 to 6.07 | p = 0.46 | |

| Electroacupuncture | 2 | 0% | p = 0.63 | Random | −4.77 | −5.94 to −3.61 | P < 0.001 | |

| Bee acupuncture | 1 | n.r. | n.r. | Random | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | |

| Meridian needling | 1 | n.r. | n.r. | Random | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | |

| Single treatment duration | Less 30 min | 1 | n.r. | n.r. | Random | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| 30 min | 14 | 83% | P < 0.001 | Random | −3.66 | −4.44 to −2.88 | p < 0.001 | |

| More 30 min | 6 | 99% | p = 0.009 | Random | −18.32 | −32.08 to −4.55 | p < 0.001 | |

| Treatment duration | Less than 5 weeks | 11 | 88% | P < 0.001 | Random | −3.94 | −5.27 to −2.60 | p < 0.001 |

| 5 weeks-10 weeks | 8 | 90% | p < 0.001 | Random | −4.67 | −5.99 to −3.35 | P < 0.001 | |

| More than 10 weeks | 6 | 87% | P < 0.001 | Random | −5.59 | −7.73 to −3.45 | p < 0.001 | |

Results of subgroup analysis on the improvement of AS in patients with acupuncture intervention.

n.r., not reported.

Sensitivity analysis

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the pooled results. First, a sensitivity analysis restricted to high-quality studies could not be performed because only one study was rated as having a low overall risk of bias (21). Second, the leave-one-out analysis showed that the pooled effect estimates and heterogeneity remained stable after sequential exclusion of each study, indicating that no single study exerted a disproportionate influence on the overall findings or served as the primary source of heterogeneity.

Discussion

This study conducted a meta-analysis of 35 RCTs to clarify the core efficacy of acupuncture for ankylosing spondylitis (AS). Compared with conventional treatment alone, the acupuncture group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in disease activity (assessed via BASDAI and ASDAS), functional status (BASFI), and pain intensity (VAS score), alongside a marked reduction in inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP). Baseline levels of these markers were generally comparable between groups, reducing—but not eliminating—the possibility that post-treatment differences were influenced by initial imbalance. These findings provide quantitative evidence supporting acupuncture as a beneficial intervention for AS.

However, high heterogeneity was observed across all outcome measures. Further analysis identified the key potential contributors: inadequate control of confounding factors, including variations in acupuncture modalities, intervention durations, and assessment tools, which precluded the identification of core variables influencing outcomes. Although heterogeneity can be explored through a stepwise subgrouping approach, which involves holding two variables constant (e.g., assessment tool and intervention duration) while varying the third (e.g., needling method) to observe changes in I2, this strategy requires an adequate number of studies. Specifically, each resulting subgroup must contain at least two studies to allow meaningful comparison; otherwise, the findings cannot be considered robust.

Building on the above findings regarding efficacy and heterogeneity, we further explored the mechanisms underlying acupuncture’s symptom-alleviating effects in AS. From the perspective of shared mechanisms, existing studies have validated acupuncture’s effectiveness across multiple dimensions: (a) At the neural repair level, acupuncture along the Governor Vessel (Du Meridian) can promote the repair and regeneration of damaged neural tissue (53). For example, in an animal model of spinal cord injury, this approach upregulated the expression of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2) and neurofilament-light chain (NF-L), suggesting potential for improving neurofunction-related symptoms in AS patients (26); (b) At the immune regulation and bone protection level, acupuncture modulates the immunoinflammatory state of AS patients by reducing ESR and proinflammatory cytokine levels while increasing the expression of complement C3 and immunoglobulin A (IgA). Additionally, studies have observed that acupuncture may downregulate human leukocyte antigen-B27 (HLA-B27) expression to slow disease progression, promote central endorphin release for pain relief, and reduce levels of bone turnover enzymes (e.g., creatine kinase, alkaline phosphatase) to protect bone tissue (54, 55); (c) At the neurohumoral regulation level, acupuncture stimulation of the abundant superficial nerve endings triggers neurohumoral responses. Beyond promoting endorphin release, this stimulation relieves muscle spasms, improves the biomechanical function of affected joints, and ultimately enhances patients’ motor capacity and quality of life (56).

Furthermore, distinct acupuncture modalities exhibit targeted unique mechanisms (57): (a) Warm needle acupuncture: Combining thermal stimulation with needling, it improves local circulation, inhibits inflammatory mediators, and reduces IL-17 levels. This blocks the “IL-17/IL-23 mediated upregulation of calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) in osteoblasts” pathway, thereby delaying pathological ossification in AS (58); (b) Floating needling: By sweeping subcutaneous connective tissue, it generates bioelectrical signals along fascial planes, rapidly altering cell signaling and membrane permeability in target regions to achieve rapid pain relief (59, 60); (c) Fire needling: Exerting both mechanical and thermal stimulation at acupoints, it warms and unblocks meridians, activates blood circulation to resolve stasis, and alleviates pain and stiffness (43); (d) Acupotomy: Performs microincisions at tender points to regulate pain-related neuropeptides (e.g., increasing substance P levels), exerting therapeutic effects through neurochemical changes (49, 50, 61, 62).

Given the complex systemic nature of AS, multimodal treatment strategies integrating internal and external therapies may offer more comprehensive symptom control. An integrated strategy combining internal therapies (e.g., systemic medications) and external therapies (e.g., acupuncture, physical therapy) may provide the most effective management. In TCM, internal medicine (herbal therapy) and external treatment (acupuncture) have complementary strengths (63). Combining them may produce synergistic effects: acupuncture can enhance the distribution and efficacy of medications (helping them reach the entire body) (28). In contrast, medications can prolong or amplify the benefits of acupuncture in unblocking meridians (26). By targeting both internal pathology and external symptoms, this combined approach could yield superior outcomes in AS (27).

Despite these encouraging findings, several limitations warrant consideration. The included trials differed in acupuncture techniques, practitioner expertise, and acupoint selection, which may have contributed to heterogeneity in treatment effects. Moreover, the overall methodological quality was moderate, with frequent issues such as lack of blinding and small sample sizes, limiting the robustness of the conclusions. Most outcomes relied on patient-reported measures, while objective indicators such as imaging or biomarkers were seldom employed. In addition, the underlying mechanisms of AS and of acupuncture’s therapeutic effects remain insufficiently understood, and certain outcome measures required standardization or data approximation during synthesis, potentially introducing minor errors.

Future research should prioritize the establishment of standardized acupuncture protocols, which would help reduce heterogeneity and enable more reliable comparisons across studies. Equally important is the conduct of high-quality, multicenter randomized controlled trials with rigorous methodological safeguards, such as adequate blinding and appropriate sample sizes, to strengthen the evidence base. The use of more objective outcome measures, including imaging techniques and functional assessments, alongside patient-reported scales, could improve the accuracy of efficacy evaluation and minimize bias. Furthermore, long-term follow-up studies are needed to clarify not only the sustained effects of acupuncture and moxibustion but also their potential influence on disease progression and overall prognosis.

Nevertheless, this study still holds great significance. Through meta-analysis, this study found that in addition to conventional needling, specialized acupuncture modalities such as fire needling, catgut embedding, and acupotomy also serve as effective supplementary treatments for AS. Furthermore, no acupuncture-related serious adverse events were reported in the trials included in this study, indicating that acupuncture has good safety as an adjuvant therapy. Currently, recommendations on acupuncture for AS treatment remain relatively scarce in international guidelines (64). This study provides quantitative evidence for the adjuvant role of acupuncture (including specialized modalities) in improving AS symptoms, which is expected to offer a reference basis for the development and update of relevant guidelines in the future. Although this study still lacks sufficient evidence to directly compare the efficacy of the aforementioned different acupuncture techniques, which makes it impossible to objectively rank their effectiveness, it also points out a direction for subsequent research.

In the future, we hope that more researchers will build on these findings by expanding research in this field and by developing more standardized acupuncture protocols, thereby providing stronger and more comparable evidence for integrating acupuncture into the clinical management of AS and related immune diseases.

Conclusion

As revealed in this systematic review, acupuncture (including electroacupuncture, warm acupuncture, and fire acupuncture) is effective and safe for AS, for it not only markedly reduces scores on scales like BASFI, BASDAI, ASDAS, and VAS (thereby alleviating back pain and improving disease activity and functional status) but also lowers CRP and ESR levels to curb inflammation. Rarely reported adverse events, coupled with its advantages of being eco-friendly, cost-effective, and efficacious, further highlight its level. However, significant heterogeneity across studies, combined with the paucity of large-scale, high-quality controlled trials, undermines the current evidence base. Thus, future research should prioritize high-quality multi-center trials and enhanced comparisons between therapies to objectively evaluate various acupuncture approaches and refine the evidence system for acupuncture in AS treatment.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SS: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RB: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HY: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82374369) and Capital Medical Development Research Fund (No. 2024-2-40613).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1716550/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Braun J Sieper J . Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet. (2007) 369:1379–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60635-7,

2.

Sharip A Kunz J . Understanding the pathogenesis of spondyloarthritis. Biomolecules. (2020) 10:1461. doi: 10.3390/biom10101461,

3.

Marzo-Ortega H . Axial spondyloarthritis: coming of age. Rheumatology. (2020) 59:iv1–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa437,

4.

Ward MM Deodhar A Gensler LS Dubreuil M Yu D Khan MA et al . 2019 update of the American College of Rheumatology/spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis research and treatment network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. (2019) 71:1285–99. doi: 10.1002/acr.24025,

5.

Shan H Wu X . HLA-B27-positive spondyloarthritis-associated ocular diseases. Chin J Exp Ophthalmol. (2024) 42:780–4. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn115989-20220828-00398

6.

Ward MM Deodhar A Gensler LS Dubreuil M Yu D Khan MA et al . 2019 update of the American College of Rheumatology/spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis research and treatment network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2019) 71:1599–613. doi: 10.1002/art.41042,

7.

Yang X Garner LI Zvyagin IV Paley MA Komech EA Jude KM et al . Autoimmunity-associated T cell receptors recognize HLA-B*27-bound peptides. Nature. (2022) 612:771–7. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05501-7,

8.

He D Cheng P Wang R Fan J . Clinical practice guideline of integrated of traditional Chinese and Western medicine for ankylosing spondylitis. Shanghai Med Pharm J. (2023) 44:23–30. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-1533.2023.13.009

9.

Baraliakos X vander Heijde D Sieper J Inman RD Kameda H Maksymowych WP et al . Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis refractory to biologic therapy: 2-year clinical and radiographic results from the open-label extension of the SELECT-AXIS 2 study. Arthritis Res Ther. (2024) 26:197. doi: 10.1186/s13075-024-03412-8,

10.

Fan M Liu J Zhao B Wu X Li X Gu J . Indirect comparison of NSAIDs for ankylosing spondylitis: network meta-analysis of randomized, double-blinded, controlled trials. Exp Ther Med. (2020) 19:3031–41. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8564,

11.

Xu J Ji W . Isofraxidin inhibits the proliferation and differentiation of the osteoblast MC3T3-E1 subclone 14 cell line. Cell Mol Biol Fr. (2023) 69:44–50. doi: 10.14715/cmb/2023.69.15.7,

12.

Su Y Ma Q . Deciphering neuro-immune regulation in the view of the acupuncture discipline. Bull Natl Nat Sci Found China. (2024) 38:446–53. doi: 10.16262/j.cnki.1000-8217.2024.03.004

13.

Xuan Y Huang H Huang Y Liu D Hu X Geng L . The efficacy and safety of simple-needling therapy for treating ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2020) 2020:4276380. doi: 10.1155/2020/4276380,

14.

Zheng Y . Clinical efficacy observation of Jian pi Qu Shi warm acupuncture in the treatment ofActive ankylosing spondylitis. Fujian, China: Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2023).

15.

Wang D . Clinical study on Du moxibustion accompanied by needle warming moxibustion in treating spine stiffness of the mid-term ankylosing spondylitis. Shandong, China: Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2020).

16.

Sterne JAC Savović J Page MJ Elbers RG Blencowe NS Boutron I et al . RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2019) 366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898,

17.

Braun J Pincus T . Mortality, course of disease and prognosis of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. (2002) 20:S16–22. Available online at: https://www.clinexprheumatol.org/abstract.asp?a=1455

18.

Higgins J Thomas J Chandler J Cumpston M Li T Page M et al . Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester (UK): John Wiley Sons (2019).

19.

Chen Y An Y . Observation on the effect of silver needle combined with Bushen Qiangdu Zhilou decoction in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Chin J Clin Ration Drug Use. (2017) 10:58–9. doi: 10.15887/j.cnki.13-1389/r.2017.02.037

20.

Gao S . Clinical observation of the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) with liver and kidney deficiency by tonifying the kidney and adjusting the governor meridian and sulfasalazine. Henan, China: Henan University of Chinese Medicine (2019).

21.

Hou H Xiong D Li J . Efficacy of Wenyang Tongdu acupuncture combined with internal heated needling in treating AS of cold-dampness obstruction and its influence to serum levels of ESR, CRP and RF. J Clin Acupunct Moxibust. (2021) 37:18–21. doi: 10.19917/j.cnki.1005-0779.021217

22.

Huang Y . A randomized parallel controlled study on acupuncture for treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. J Pract Tradit Chin Intern Med. (2016) 30:98–100. doi: 10.13729/j.issn.1671-7813.2016.04.40

23.

Liu B . Effect of acupuncture combined with conventional drugs on ankylosing spondylitis. China Mod Med. (2019) 26:21–24, 33. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFQ&dbname=CJFDLAST2019&filename=ZGUD201902006

24.

Luo Y Zhong D Huang Y Li Z . Clinical observation on acupuncture in treating patients with sleep disorders in ankylosing spondylitis. J Guangzhou Univ Tradit Chin Med. (2024) 41:3210–5. doi: 10.13359/j.cnki.gzxbtcm.2024.12.019

25.

Shi W Nie C Hu X Wang H . Clinical study on the treatment of early - stage ankylosing spondylitis by Huangqi Guizhi Wuwu decoction combined with Xuefu Zhuyu decoction and acupuncture. Shaanxi Zhong Yi Yao Da Xue Xue Bao. (2020) 41:315–317, 337. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-7369.2020.03.012

26.

Thanakorn T . Clinical observation on Dumai needle row combined with Tongbiling tablets of ankylosing spondylitis. Guangzhou, China: Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (2021).

27.

Wang F Wang Y . Clinical observation of acupuncture combined with modified Wulingtang on the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Chin J Basic Med Tradit Chin Med. (2017) 23:3210–5. doi: 10.19945/j.cnki.issn.1006-3250.2017.08.035

28.

Zhao M . Clinical efficacy of Zhuang medicine acupuncture in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Guangxi, China: Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine (2023).

29.

Gao T Huang G . Clinical observation of warm needling moxibustion at Jiaji point combined with Western medicine in treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Hubei J Tradit Chin Med. (2019) 41:17–9. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=OfZxIIxxsvA2LWUegHiSj0XB8C7W9d5feYzEUHnG4Rp_gR5Ncxf4hVrDHJitdi6EdOSEWHCXHh8XZmr056Raeumk-IK4NGKIHhHqAJM55ikczQ5OlF7V3q5zRuLi_sL4ipoXkTwhOV_T-EG5oNSKBTe-JpOGOT-_XOk7Rbnuj39TVZiZPGwboQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

30.

Huang W . Clinical efficacy observation of the method of spleen-strengthening, dampness - eliminating and warm acupuncture and moxibustion in the treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis. Chin Sci Technol J Database Full Text Ed Med Health. (2024) 4:0107–10. doi: 10.53381/20240413

31.

Lin B Xu D Chen H Zhang S Luo X . Clinical effect of aligned warm needling combined with traditional Chinese medicine fumigation on ankylosing spondylitis of kidney-deficiency governor meridian cold. World Chin Med. (2023) 18:2666–70. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-7202.2023.18.018

32.

Luo X Zhang X Huang C . Observation on the efficacy of short-needling, lateral-needling, warm acupuncture and moxibustion combined with Tripterygium glycosides tablets in the treatment of acute exacerbation of ankylosing spondylitis. J Mod Integr Med. (2022) 31:2121–5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-8849.2022.15.015

33.

Wang J . Clinical studies of treatment of thirty ankylosing spondylitis by warm acupuncture. Guangzhou, China: Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (2013).

34.

Yang L Ouyang B . Clinical observation of warm acupuncture and moxibustion in the treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis of kidney deficiency and governor vessel cold type. Chinas Naturop. (2020) 28:26–8. doi: 10.19621/j.cnki.11-3555/r.2020.1912

35.

Ye L Zou Y . Clinical study of warm needling moxibustion plus intra-articular injection of sodium hyaluronate for hip involvement in ankylosing spondylitis. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. (2022) 20:206–12. doi: 10.1007/sl1726-022-1314-8

36.

Zhang L . Clinical study on treatment of kidney Yang-deficiency syndrome of ankylosing spondylitis with needle warming moxibustion. Xinjiang, China: Xinjiang Medical University (2017).

37.

Zhou S Chen Z Xu Z . Ankyiosing spondylitis by warm needling on Jiaji point. J Clin Acupunct Moxibust. (2011) 27:11–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-0779.2011.03.004

38.

Zhuang Y . Clinical observation on the treatment of row warm acupuncture combined with celecoxib for ankylosing spondylitis of kidney deficiency and Du-meridian cold syndrome. Fujian, China: Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2023).

39.

Lu Z Cheng X Ge L Zheng Y . The influence of floating needle combined with reperfusion activity on ankylosing spondylitis. Guangming J Chin Med. (2024) 39:726–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-8914.2024.04.030

40.

Wang Y Qiu W . Observations on the efficacy of superficial needling therapy for early ankylosing spondylitis. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibust. (2017) 36:1088–91. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2017.09.1088

41.

Zeng Y Zhang X Xiao Q . Short-term clinical effect of floating acupuncture combined Jibi pill on acute pain of ankylosing spondylitis. Guid J Tradit Chin Med Pharm. (2017) 23:63–5. doi: 10.13862/j.cnki.cn43-1446/r.2017.04.019

42.

Gao L . The clinical observation of the fire needle treatment to ankylosing spondylitis of the Shen Xu DU Han. Fujian, China: Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2018).

43.

Zeng W Luo L Li W Cai W . Clinical study of filiform fire-needling back - shu points in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. J Clin Acupunct Moxibust. (2018) 34:40–2. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-0779.2018.12.012

44.

Wang Z Li Y Zhang J . Effect of akupotomye lumbar-abdominal simultaneous regulation combined with sulfasalazine on ankylosing spondylitis. Chin J Pract Med. (2022) 49:120–3. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn115689-20220112-00157

45.

Wang Z Wang L Yin F Dong B Lin X . Clinical effect of tendon acupuncture on patients with mild to moderate ankylosing spondylitis. J North Sichuan Med Coll. (2022) 37:22–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-3697.2022.01.005

46.

You Y Cai M Lin J Liu L Chen C Wang Y et al . Efficacy of needle-knife combined with etanercept treatment regarding disease activity and hip joint function in ankylosing spondylitis patients with hip joint involvement: a randomized controlled study. Medicine. (2020) 99:e20019. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020019,

47.

Guo C Wu J Zhang W Yan X . Therapeutic observation of exercise-based acupuncture combined with medication and functional training for ankylosing spondylitis. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibust. (2024) 43:400–4. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2023.13.0016

48.

Wu J Liang J Li M Yu W . Efficacy of kinematic acupuncture combined with western medicine in ankylosing spondylitis and its effect on BASFI and BASDAI score. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibust. (2023) 42:56–60. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2023.01.0056

49.

Chen C Zhang Y Guo C Yao S . Effect of acupotomy intervention on SP and CGRP in vastus medials of rats with MTrP. J Clin Acupunct Moxibust. (2018) 34:55–58, 81. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFQ&dbname=CJFDLAST2018&filename=ZJLC20180101750

50.

Chen X Chen S Shi S Chen X Shi F . Clinical effect on ankylosing spondylitis with electroacupuncture at Jiaji acupoint. J Yunnan Univ Chin Med. (2018) 40:89–91. doi: 10.19288/j.cnki.issn.1000-2723.2017.06.026

51.

Dai C . Observation on the efficacy of acupuncture combined with TNF-α antagonists in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Shanghai, China: Shanghai University of T.C.M (2020).

52.

Li X . Clinical observation of bee acupuncture combined with electric acupuncture for patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Guangzhou, China: Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (2015).

53.

Wang J Liu J Tang Z Liang Q Cui J . Acupuncture promotes neurological recovery and regulates lymphatic function after acute inflammatory nerve root injury. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e35702. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35702,

54.

İnci H İnci F . Acupuncture effects on blood parameters in patients with fibromyalgia. Med Acupunct. (2021) 33:86–91. doi: 10.1089/acu.2020.1476,

55.

Li N Guo Y Gong Y Zhang Y Fan W Yao K et al . The anti-inflammatory actions and mechanisms of acupuncture from acupoint to target organs via neuro-immune regulation. J Inflamm Res. (2021) 14:7191–224. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S341581,

56.

Liu J Huang Z Zhang G . Involvement of NF-κB signal pathway in acupuncture treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Acupunct Res. (2020) 45:914–9. doi: 10.13702/j.1000-0607.190848,

57.

Liu G Yang K Geng J Luo C Zhao Y Zhao J et al . Staged treatment for 32 cases of ankylosing spondylitis with different acupuncture methods based on jingjin theory. Zhongguo Zhenjiu. (2025) 45:156–8. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20240321-k0004

58.

Ding W Chen S Shi X Zhao Y . Efficacy of warming needle moxibustion in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Medicine. (2021) 100:e25850. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025850,

59.

Ma Z Hu J Zou L . Effect of governor vessel moxibustion and floating needle therapy on activity function and levels of inflammatory factors and pain mediator in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Reflexol Rehabil Med. (2021) 17:13–6. Available online at: https://lib.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=00004H0G596NJEKK5D3F1JH1MLDG8JV1MPCHQ

60.

Xu H Lv R Zeng K . Clinical application of floating needle combined with rehabilitation therapy in spinal diseases. China Sci Technol J Database Med Pharm. (2024) 4:0176–9. Available online at: https://lib.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=1000004101111

61.

Duan Y Tan T Xiao M . Clinical observation on 50 cases of ankylosing spondylitis treated with needle knife. Rheum Arthritis. (2023) 12:24–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4174.2023.07.006

62.

Yue H Chen Y Wang Y Tao Y Cai J Li N . Effect of Jiedu Chushi Tongdu decoction combined with small needle-knife in treatment of damp-heat obstruction type of arthralgia ankyloss spondylitis and its effect on serum levels of CRP, IL-1β and TNF-α. Chin Arch Tradit Chin Med. (2024) 42:63–7. doi: 10.13193/j.issn.1673-7717.2024.08.013

63.

Hu M Liu Y Zhu J Lin L Tang P Shi M . Clinical randomized controlled trials of acupuncture and moxibustion combined with internal administration of traditional Chinese medicine prescriptions for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a meta-analysis. Guangxi Med J. (2024) 46:1911–9. doi: 10.11675/j.issn.0253-4304.2024.12.16

64.

Choufani M Ermann J . Updating the 2019 ACR/SAA/SPARTAN recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (SPARTAN 2024 annual meeting proceedings). Curr Rheumatol Rep. (2024) 27:8. doi: 10.1007/s11926-024-01170-9,

65.

Goodman SM Springer B Guyatt G Abdel MP Dasa V George M et al . 2017 American College of Rheumatology/American Association of hip and Knee Surgeons Guideline for the perioperative Management of Antirheumatic Medication in patients with rheumatic diseases undergoing elective Total hip or Total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res. (2017) 69:1111–24. doi: 10.1002/acr.23274,

66.

Taurog JD Chhabra A Colbert RA . Ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374:2563–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1406182,

Summary

Keywords

acupuncture, ankylosing spondylitis, complementary and alternative therapy, RCT, systematic review

Citation

Zhang J, Sun S, Bai R, Yin H, Chen J and Kong W (2026) Efficacy of acupuncture in the management of ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis with insights. Front. Neurol. 16:1716550. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1716550

Received

01 October 2025

Revised

20 December 2025

Accepted

22 December 2025

Published

13 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Huadong Zhang, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, China

Reviewed by

Jianwen Guo, Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China

Maorong Fan, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Zhang, Sun, Bai, Yin, Chen and Kong.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Weiping Kong, drkongweiping@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.