Abstract

Background:

Depression is a common comorbid condition in stroke patients, significantly impairing their quality of life. Electroacupuncture (EA) has shown promising effects in treating post-stroke depression (PSD), but integrated evidence remains scarce.

Objective:

To investigate the efficacy of EA in improving PSD and evaluate its clinical effectiveness and safety through systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods:

We searched eight electronic databases (PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, CNKI, VIP Data Platform, Wanfang Data Knowledge Service Platform, and China Biomedical Literature Service System) and manually reviewed reference lists of relevant literature and clinical trial registries for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of EA for PSD. Eligible studies were screened based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, and relevant data were extracted. Meta-analysis was performed using RevMan 5.4 software.

Results:

A total of 22 studies involving 1,640 patients were included. Meta-analysis results showed that EA improved HAMD (MD = −1.71, 95% CI: −2.79 to −0.63, I2 = 89%, p = 0.002), efficacy rate (OR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.43 to 2.64, I2 = 0%, p < 0.0001), and safety (OR = 0.2, 95% CI: 0.12–0.34, I2 = 45%, p < 0.00001). However, it did not show superiority over the control group in terms of the Barthel Index (BI) (MD = 4.01, 95% CI: −0.26 to 8.27, I2 = 70%, p = 0.07) and SDS (MD = −3.28, 95%CI: −6.78 to 0.21, I2 = 97%, p = 0.07). The GRADE assessment indicates that the evidence level for HAMD is very low, while that for BI is low.

Conclusion:

EA demonstrated superiority over conventional drug therapy in improving HAMD scores, efficacy rates, and safety. However, no significant difference was observed between EA and the control group in improving BI and SDS scores. The pooled results for HAMD scores and SDS showed high heterogeneity, and the study itself exhibited considerable heterogeneity. Furthermore, all included studies were conducted in China, which may introduce regional bias. Future rigorous clinical research is needed to provide high-quality evidence.

1 Introduction

Stroke is characterized by high incidence, high disability rates, and high mortality, significantly impacting global health (1). Post-stroke depression (PSD), as a common and severe psychiatric complication, adversely affects patients’ recovery and quality of life (2). Data indicates that 25.4% of patients develop PSD within 2 years of stroke onset, yet only 7.8% recognize their depressive symptoms (3). These individuals often lack timely or standardized treatment. Despite physical functional improvements, psychological symptoms may worsen, hindering overall recovery.

PSD onset is associated with factors like age, gender, education level, and stroke type. It commonly manifests as persistent low mood, accompanied by cognitive impairment, apathy, anhedonia, fatigue, self-blame, self-harm behaviors, and even suicidal ideation (4). PSD exhibits complex interactions with other complications such as anxiety, neurological deficits, and obstructive sleep apnea (5), potentially leading to severe functional impairment, reduced quality of life, recurrent stroke, and mortality (6, 7). PSD may involve diverse etiological mechanisms, encompassing biological and psychological hypotheses (8). Biological hypotheses include four mechanisms: lesion localization, neurotransmitter, inflammatory cytokine, and genetic polymorphism. The specific location of lesions plays a crucial role in PSD pathogenesis; reduced serotonin and norepinephrine in the brain are associated with PSD; increased cytokines post-stroke may lead to depression; and the short variant genotype of the serotonin transporter gene linkage promoter region shows a significant association with major depressive disorder after stroke (9). Psychological hypotheses suggest that social and psychological stressors associated with stroke may be primary contributors to depression. Currently, no definitive evidence supports or refutes purely biological or purely psychosocial mechanisms. It appears to be a psychosocial, multifactorial mental disorder.

Current PSD treatment primarily relies on pharmacotherapy, supplemented by psychotherapy and techniques like transcranial magnetic stimulation (10). However, pharmacological interventions exhibit slow onset (typically 4–8 weeks) and are prone to drug tolerance and adverse reactions (11, 12). This poses challenges for PSD patients’ recovery. EA is a technique that builds upon traditional acupuncture methods. After obtaining qi sensation at the acupoint, a microcurrent wave (sensing) that responds to the body’s bioelectricity is applied through the needle to treat diseases. It is currently widely used in the treatment of PSD and has achieved certain clinical effects. Although clinical evidence demonstrates the good efficacy of EA in treating PSD, the current evidence has not been effectively integrated and has not formed persuasive evidence-based medical evidence.

Therefore, this study conducts a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical research on EA for PSD to integrate existing evidence, provide reliable guidance for clinical practice, clarify current research limitations, and offer reference for future studies.

2 Materials and methods

This study was conducted according to the PRISMA statement and was registered in PROSPERO prior to commencement (Registration Number: CRD420251171897).

2.1 Data sources and search strategy

This study searched eight databases including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, China Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), China Science Journal Database (VIP), Wanfang Database, and China Biomedical Literature Service System (CBM). Publications were limited to English and Chinese languages, with the search cutoff date set at July 21, 2025. Mesh terms were combined with free-text keywords for retrieval, with primary search terms including “Electroacupuncture,” “Stroke,” and “Depression.” The specific search strategy is detailed in Table 1 (using PubMed as an example). Search strategies for other databases and the PRISMA 2020 checklist are provided in the Supplementary material.

Table 1

| Rank | Search term | Result |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | Electroacupuncture [MeSH] | 5,658 |

| #2 | Electroacupuncture OR electro-acupuncture OR electric acupuncture OR Electroneedle OR “Electroacupuncture Treatment” OR “Treatment, Electroacupuncture” | 11,276 |

| #3 | #1 OR #2 | 11,276 |

| #4 | Stroke [MeSH] | 192,769 |

| #5 | Ischemic stroke [MeSH] | 18,031 |

| #6 | Hemorrhagic stroke [MeSH] | 844 |

| #7 | Brain infarction [MeSH] | 45,224 |

| #8 | Cerebral hemorrhage [MeSH] | 39,969 |

| #9 | Cerebrovascular accident OR Cerebrovascular Accidents OR CVA OR Cerebrovascular Apoplexy OR Apoplexy, Cerebrovascular OR Vascular Accident, Brain OR Brain Vascular Accident* OR Vascular Accidents, Brain OR Cerebrovascular Stroke* OR Stroke, Cerebrovascular OR Strokes, Cerebrovascular OR Apoplexy OR Cerebral Stroke* OR Stroke, Cerebral OR Strokes, Cerebral OR Stroke, Acute OR Acute Stroke* OR Strokes, Acute OR Cerebrovascular Accident, Acute OR Acute Cerebrovascular Accident* OR Cerebrovascular Accidents, Acute | 505,119 |

| #10 | #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 | 531,500 |

| #11 | Depression [MeSH] | 282,884 |

| #12 | Depressive disorder [MeSH] | 129,269 |

| #13 | Depressive Symptoms OR Depressive Symptom OR Symptom, Depressive OR Emotional Depression OR Depression, Emotional OR Depressive Disorders OR Disorder*, Depressive OR Neurosis, Depressive OR Depressive Neuroses OR Depressive Neurosis OR Neuroses, Depressive OR Depression*, Endogenous OR Endogenous Depression* OR Depressive Syndrome* OR Syndrome*, Depressive OR Depression*, Neurotic OR Neurotic Depression* OR Melancholia* OR Unipolar Depression OR Depression*, Unipolar OR Unipolar Depressions | 637,288 |

| #14 | #11 OR #12 OR #13 | 637,288 |

| #15 | #3 AND #10 AND #14 | 50 |

Search strategy (PubMed as an example).

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were established using the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design) framework. Specific criteria were: (1) P: Participants with a confirmed diagnosis of PSD; (2) I: Treatment group receiving EA therapy; (3) C: Control group receiving conventional medication; (4) O: Using the HAMD as the primary indicator; (5) S: Study design being randomized controlled trials.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Studies with unclear diagnoses or comorbidities affecting outcome assessment; (2) Studies involving concurrent interventions; (3) Studies with non-representative outcome measures; (4) Not randomized controlled trials; (5) Studies lacking full-text access or incomplete data.

2.3 Literature management and data extraction

Two researchers independently screened and extracted data based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through consultation with a third researcher. The screening process involved: (1) Removing duplicate records using EndNote X9.3 literature management software. (2) Reviewing titles and abstracts to exclude reviews, theses, conference papers, scientific achievements, and other non-relevant literature. (3) Full-text review to determine eligibility.

After literature screening, the following information was extracted: (1) Basic literature information: author details, publication year, etc.; (2) Basic subject information; (3) Intervention method, intervention frequency, and treatment duration; (4) Outcome measures.

2.4 Literature quality assessment

We used the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (ROB 2.0) to assess the quality of included studies. This tool evaluates five domains: Bias in the randomization process, bias in deviation from the intended intervention, bias in missing outcome data, bias in outcome measurement, and bias in selective reporting of results. The bias in deviation from the intended intervention domain is further subdivided into two scenarios based on research objectives: evaluating the effectiveness of intervention assignment and evaluating the effectiveness of intervention adherence. Each domain contains multiple signal questions. When assessing the risk of bias in RCTs, researchers must make judgments and objectively answer these questions. Signal questions typically offer five response options: Yes (Y), Probably Yes (PY), Probably No (PN), No (N), and No Information (NI).

2.5 Statistical analysis

Following the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration and PRISMA guidelines, statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.4.1, reporting pooled risk ratios (RR) and mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic. Heterogeneity was defined as low, moderate, or high based on I2 values of 25, 50, and 75%, respectively. Publication bias for primary outcomes was visually assessed using funnel plots. The Egger regression test was applied to analyze publication bias.

To more accurately assess the robustness of the analysis results and the inclusion of bias in the studies, we shall employ Stata 18 to conduct sensitivity analyses and Egger’s test.

3 Results

3.1 Search results

A total of 1,106 publications were retrieved from databases. After removing duplicates, 633 publications remained. Further screening based on title and abstract review yielded 27 publications. Full-text review of these 27 publications resulted in 22 eligible publications meeting inclusion criteria, all in Chinese. The specific screening process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Literature screening process.

3.2 Basic characteristics of included studies

A total of 20 studies were included (13–34). These comprised 22 individual research projects involving 1,761 patients. All studies were conducted in China across 12 provinces. All studies provided specific diagnostic criteria. The intervention group in each trial received EA. Among the control groups, 18 studies used fluoxetine as the control, two studies used sertraline tablets, one study used Flupentixol and Melitracen Tablets, and one study used sertraline hydrochloride. The intervention periods ranged from 4 weeks to 60 days across the 22 studies. Detailed information is presented in Table 2.

Table 2

| No. | Author | Year | Research location | Diagnostic criteria | Grouping method | Blind method | Sample size | Intervention methods | Intervention frequency | Course of treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bi et al. | 2010 | Shandong Province | Yes | Merely mentioned randomly | Double-blind | I:31 C:32 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 5 t/w C: 20 mg/d |

I:6 w C:6 w |

HAMD; SDS |

| 2 | Chen | 2012 | Zhejiang Province | Yes | Merely mentioned randomly | Not mentioned | I:47 C:47 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 3 t/w C: 20 mg/d |

I:4 w C:4 w |

HRDS; clinical efficacy rate; comparison of limb function |

| 3 | Chen et al. | 2005 | Jilin Province | Yes | Computerised random grouping | Not mentioned | I:30 C:30 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 1 t/d C: 20 mg/d |

I:4 w C:4 w |

Clinical efficacy rate; SDS; SCAG |

| 4 | Chu et al. | 2007 | Jilin Province | Yes | Random number table method | Not mentioned | I:36 C:36 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 5 t/w C: 20 mg/d |

I:8 w C:8 w |

HAMD; clinical efficacy rate; adverse events |

| 5 | Dai | 2009 | Hubei Province | Yes | Randomised allocation according to order of presentation | Not mentioned | I:30 C:30 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Flupentixol and Melitracen Tablets |

I: 6 t/w C: 21 mg/d |

I:4 w C:4 w |

HADM; clinical efficacy rate; onset time |

| 6 | Dong et al. | 2017 | Heilongjiang Province | Yes | Random number table method | Not mentioned | I:50 C:50 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 1 t/d C: 20 mg/d increased to 80 mg/d |

I:30 d C:28 d |

HAMD; SDS; electroencephalogram changes; 5-HIAA; clinical efficacy rate |

| 7 | Dong et al. | 2007 | Heilongjiang Province | Yes | Random number table method | Not mentioned | I:38 C:34 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I:1 t/d C: 20 mg/d |

I:30 d C:28 d |

HAMD; SDS; severity index; clinical efficacy rate |

| 8 | Hong et al. | 2015 | Zhejiang Province | Yes | Random number table method | Not mentioned | I:30 C:30 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Escitalopram Oxalate Tablets |

I: 6 t/w C: 20 mg/d |

I:30 d C:30 d |

HAMD; Barthel; clinical efficacy rate |

| 9 | Huang et al. | 2014 | Sichuan Province | Yes | Random number table method | Envelope method | I:30 C:30 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 5 t/w C: 20 mg/d |

I:6 w C:6 w |

HAMD; Ronneberg Sleep Scale; Clinical efficacy rate; adverse events |

| 10 | Kang et al. | 2014 | Hebei Province | Yes | Merely mentioned randomly | Not mentioned | I:40 C:40 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 1 t/d C: 20 mg/d |

I:4 w C:4 w |

NIHSS; ADL; HAMD |

| 11 | Li et al. | 2015 | Zhejiang Province | Yes | Computerised random grouping | Not mentioned | I:11 C:10 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 1 t/d C: 20 mg/d |

I:8 w C:8 w |

HAMD; r CBF; clinical efficacy rate; ROI radioactive count ratio |

| 12 | Li et al. | 2013 | Heilongjiang Province | Yes | Randomised allocation according to order of presentation | Not mentioned | I:35 C:35 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 1 t/d C: 20 mg/d |

I:4 w C:4 w |

HAMD; MESSS; clinical efficacy rate |

| 13 | Long et al. | 2004 | Hunan Province | Yes | Merely mentioned randomly | Single-blind | I:36 C:36 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 6 t/w C: 10-40 mg/d |

I:4 w C:4 w |

HAMD; CNS; BI; FMA; adverse events |

| 14 | Nie et al. | 2010 | Guangdong Province | Yes | Random number table method | Not mentioned | I:30 C:30 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 1 t/d C: 20 mg/d |

I:60 d C:60 d |

Clinical efficacy rate; HAMD; MESSS; Barthel |

| 15 | Peng et al. | 2011 | Guangdong Province | Yes | Merely mentioned randomly | Envelope Method | I:58 C:59 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 6 t/w C: 20 mg/d |

I:4 w C:4 w |

HRSD; SDS; FIM; adverse events |

| 16 | Wang | 2010 | Zhejiang Province | Yes | Merely mentioned randomly | Not mentioned | I:40 C:40 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Sertraline hydrochloride |

I: 1 t/d C: 50 mg/d |

I:30 d C:30 d |

HAMD; affected side FMA |

| 17 | Wu et al. | 2007 | Gansu Province | Yes | Randomised allocation according to order of presentation | Not mentioned | I:32 C:31 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Escitalopram Oxalate Tablets |

I: 5 t/w C: 20 mg/d |

I:6 w C:6 w |

Clinical efficacy rate; HAMD;ADL; adverse events; TESS |

| 18 | Xu et al. | 2015 | Liaoning Province | Yes | Randomised allocation by treatment method | Not mentioned | I:40 C:40 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 1 t/d C: 20 mg/d |

I:6 w C:6 w |

Clinical efficacy rate; HAMD |

| 19 | Zhang et al. | 2013 | Hubei Province | Yes | Merely mentioned randomly | Not mentioned | I:34 C:27 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 6 t/w C: 20 mg/d |

I:6 w C:6 w |

HAMD; SDS |

| 20 | Zhou | 2010 | Henan Province | Yes | Computerised random grouping | Not mentioned | I:145 C:148 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 1 t/d C: 20 mg/d |

I:8 w C:8 w |

HAMD; clinical efficacy rate; adverse events |

| 21 | Zhou | 2007 | Hunan Province | Yes | Merely mentioned randomly | Not mentioned | I:31 C:30 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 1 t/d C: 20 mg/d |

I:4 w C:4 w |

HAMD; Adverse events; TESS; patient satisfaction rate |

| 22 | Zhu et al. | 2012 | Zhejiang Province | Yes | Merely mentioned randomly | Not mentioned | I:32 C:30 |

I: Electroacupuncture C: Fluoxetine |

I: 5 t/w C: 20 mg/d |

I:8 w C:8 w |

Clinical efficacy rate; HAMD; adverse events |

Basic characteristics of included studies.

3.3 Quality assessment of included studies

The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (ROB 2.0) was used to assess the risk of bias in the included studies. Six studies used random number tables for allocation, three used computer software, 11 mentioned random allocation only, and two allocated participants based on order of arrival. One study employed an envelope method during randomization to ensure blinding. One study reported achieving double-blinding during the research process, one study reported achieving single-blinding, and the remaining studies mentioned blinding measures. This lack of consistent blinding protocols was the primary factor reducing study quality. Of the 22 studies, one was classified as “low risk,” one as “some concerns,” and 20 as “high risk.” Specific details are shown in Figures 2, 3.

Figure 2

Risk of bias summary.

Figure 3

Risk of bias graph.

3.4 Primary outcome measures

3.4.1 Hamilton depression scale (HAMD)

Eighteen studies evaluated HAMD scores before and after treatment, involving a total of 1,429 patients: 717 in the experimental group and 712 in the control group. Meta-analysis results indicated that the treatment group demonstrated greater improvement in HAMD scores compared to the control group (MD = −1.71, 95% CI: −2.79 to −0.63, I2 = 89%, p = 0.002). See Figure 4 for details.

Figure 4

HAMD forest plot.

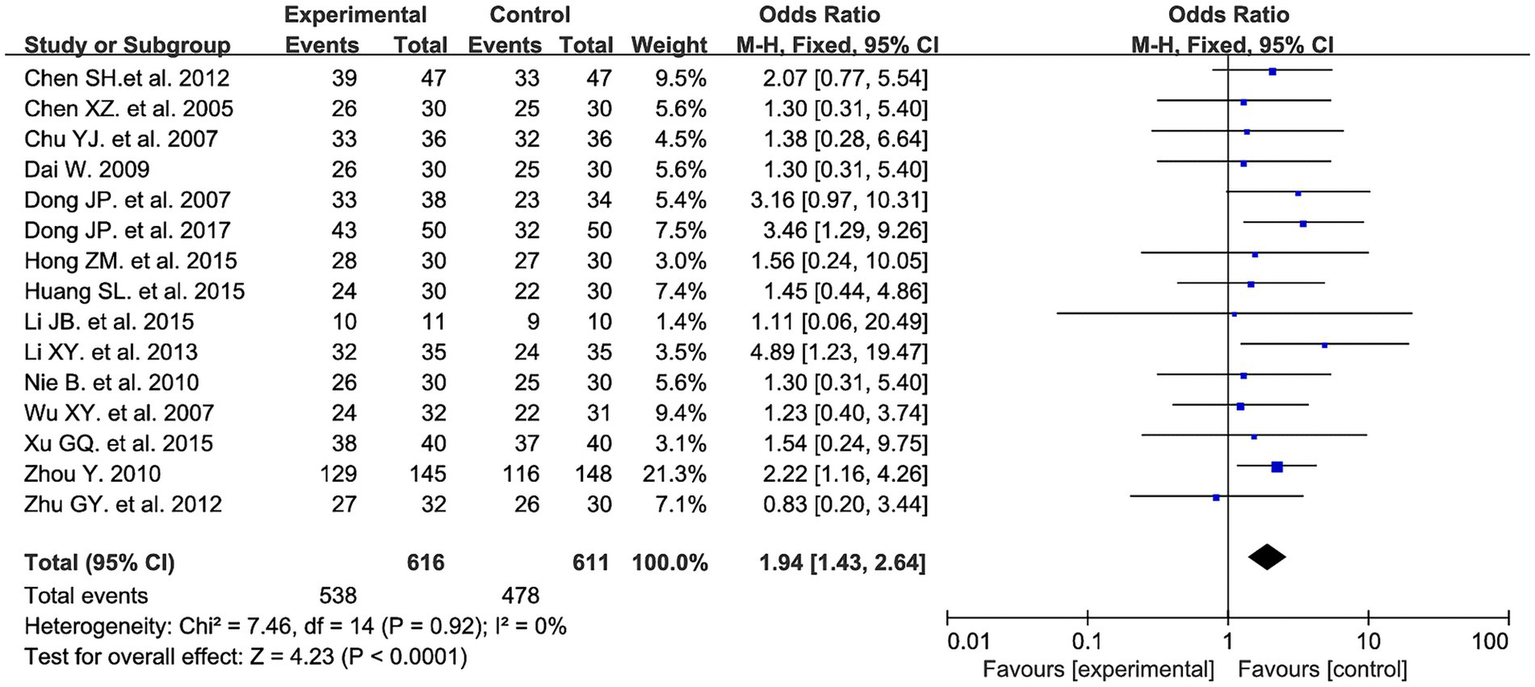

3.4.2 Clinical efficacy rate

Fifteen studies evaluated the clinical efficacy rate between the two groups, involving a total of 1,227 patients: 616 in the experimental group and 611 in the control group. Meta-analysis results showed that the experimental group had a higher efficacy rate compared to the control group (OR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.43 to 2.64, I2 = 0%, p < 0.0001). See Figure 5 for details.

Figure 5

Clinical efficacy rate forest plot.

3.5 Secondary outcomes

3.5.1 BI

Three studies evaluated the BI before and after treatment, involving 192 patients (96 in the experimental group and 96 in the control group). The meta-analysis showed no significant difference between the two groups in improving the Barthel Index (MD = 4.01, 95% CI: −0.26 to 8.27, I2 = 70%, p = 0.07). See Figure 6 for details.

Figure 6

Barthel forest plot.

3.5.2 Self-rating depression scale (SDS)

Six studies evaluated SDS before and after treatment, involving 473 patients: 241 in the experimental group and 232 in the control group. Meta-analysis results showed no significant difference between the two groups in improving the Barthel Index (MD = −3.28, 95% CI: −6.78 to 0.21, I2 = 97%, p = 0.07). See Figure 7 for details.

Figure 7

SDS forest plot.

3.5.3 Adverse events

Six studies evaluated adverse events before and after treatment, involving 667 patients (333 in the experimental group and 334 in the control group). Meta-analysis results indicated that the experimental group demonstrated superior safety (OR = 0.2, 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.34, I2 = 45%, p < 0.00001). See Figure 8 for details.

Figure 8

Adverse events forest plot.

3.6 Bias analysis

We examined potential publication bias by plotting funnel plots, where symmetry indicates no publication bias. Figure 9A shows the funnel plot for HAMD, and Figure 9B shows the funnel plot for efficacy rate. As shown in Figure 9A, most studies cluster around effect sizes close to zero, suggesting consistent overall effect directions (no studies with markedly extreme effects). Observing the symmetry of the “funnel” reveals a degree of asymmetry in the distribution of study points (particularly in the region with larger standard errors, where points are skewed toward one side). This asymmetry suggests potential publication bias. As shown in Figure 9B, study points are primarily concentrated in the region where effect sizes are close to 1, indicating that the effect sizes of most studies are consistent in direction. Observing the symmetry of the “funnel” reveals a pronounced asymmetry in the distribution of research points—in regions with larger standard errors (i.e., small-sample studies), the points deviate from the symmetrical funnel shape, exhibiting a distinct “gap” at the bottom. This asymmetry suggests a higher likelihood of publication bias.

Figure 9

![Panel A shows a funnel plot with SE(MD) on the vertical axis and MD on the horizontal axis, with data points clustered around the center line. Panel B displays another funnel plot with SE(log[OR]) on the vertical axis and OR on the horizontal axis, also with data points centered around the middle. Both plots include dashed lines forming a symmetrical funnel shape.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1732787/xml-images/fneur-16-1732787-g009.webp)

(A) HAMD funnel plot. (B) Clinical efficacy rate funnel plot.

To accurately analyse publication bias, we employed the Egger test in Stata 18 to assess the combined effect size of the HAMD. The results indicate that, the Egger test p-value for HAMD scores was 0.15, and that for efficacy rate was 0.417, both exceeding the significance level of α = 0.05. This indicates no significant linear association between effect size and precision for either measure across the included studies. Furthermore, the scatter plot for the Egger test showed symmetrical distribution of individual studies around the regression line, with no evident skewing. These findings indicate that the included studies in this meta-analysis exhibit no statistically significant publication bias, with a low risk of publication bias. The pooled results for the improvement in HAMD scores and the difference in treatment response rates demonstrate good authenticity and reliability. This provides objective and robust evidence-based medical support for evaluating the clinical efficacy of electroacupuncture in treating post-stroke depression. See Figure 10 for details.

Figure 10

(A) The Egger test for HAMD. (B) The Egger test for efficacy rate.

3.7 Sensitivity analysis

Observation of the meta-analysis results revealed considerable heterogeneity in the HAMD and SDS scores. We conducted sensitivity analyses on both datasets using Stata 18. The findings indicated varying degrees of stability in the outcomes across different endpoints within this study. The analysis using SDS as the outcome measure included six studies. Upon sequentially excluding individual studies, the pooled effect size estimates fluctuated between −1.87 and 0.35. In some instances, the effect size direction reversed and the confidence interval crossed the null line, indicating weak stability in the meta-analysis results for this measure and conclusions susceptible to interference from individual included studies. In contrast, the analysis using HAMD as the outcome measure included 18 studies. After excluding any single study, the pooled effect size consistently remained within the negative range of −0.76 to −0.43. Furthermore, all confidence intervals remained within the non-negligible threshold, with no reversal in effect size direction. This indicates robust stability and high reliability in the meta-analysis results for this measure. This further substantiates the robustness of the conclusion that electroacupuncture intervention demonstrates superior efficacy to conventional pharmacological interventions in ameliorating depressive symptoms (as measured by HAMD scores) in post-stroke patients, with minimal susceptibility to individual study data biases. See Figures 11A,B for details.

Figure 11

(A) HAMD sensitivity analysis. (B) SDS sensitivity analysis. (C) HAMD subgroup analysis forest plot.

To further investigate the sources of heterogeneity, we conducted a subgroup analysis of HAMD-related studies according to treatment duration. The subgroup analysis revealed substantial heterogeneity in both studies with treatment durations not exceeding 4 weeks and those exceeding 4 weeks, suggesting that the sources of heterogeneity may be independent of treatment duration. See Figure 11C for details.

A review of relevant studies revealed inconsistencies between the MDs reported by Huang Shile, Long Haowen, Nie Bin, Xu Guoqing, and Zhu Genying and those from other studies (19, 23, 24, 28, 32). In Huang Shile’s study, the disease duration was significantly shorter than in other studies. In Long Haowen’s study, the control group received an uncertain dosage of 10–40 mg/day, which may have contributed to the heterogeneity. Regarding studies involving the Barthel Index, excluding Hong Zhenmei’s study yielded I2 = 0%, p = 0.1. Reviewing this study revealed that the control group received sertraline tablets, whereas the other two trials used fluoxetine in their control groups, which may explain the heterogeneity.

3.8 Evidence grade assessment

We used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of evidence for this study. The meta-analysis results for HAMD and Barthel Index showed very low and low certainty, while meta-analyses for other indicators demonstrated high certainty. Detailed information is provided in Table 3.

Table 3

| Certainty assessment | No. of patients | Effect | Certainty | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Electroacupuncture | Conventional drugs | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | ||

| HADM | ||||||||||||

| 18 | Randomised trials | Very seriousa | Not seriousb | Not serious | Not serious | Publication bias strongly suspected | 717 | 712 | — | MD 1.71 lower (2.79 lower to 0.63 lower) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very lowa,b | |

| Efficiency | ||||||||||||

| 15 | Randomised trials | Not seriousa | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 616/1227 (50.2%) | 611/1227 (49.8%) | OR 1.94 (1.43 to 2.64) | 160 more per 1,000 (from 89 more to 226 more) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ Higha | |

| Adverse events | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Randomised trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 26/333 (7.8%) | 82/334 (24.6%) | OR 0.20 (0.12 to 0.34) | 184 fewer per 1,000 (from 208 fewer to 146 fewer) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | |

| SDS | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Randomised trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 241 | 232 | — | MD 3.28 lower (6.78 lower to 0.21 higher) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | |

| Barthel | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Randomised trials | Seriousa | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Publication bias strongly suspected | 96 | 96 | — | MD 4.01 higher (0.26 lower to 8.27 higher) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Lowa | |

Grade assessment results.

CI, confidence interval; MD, mean difference; OR, odds ratio.

The funnel plot indicates the presence of bias.

The meta-analysis results exhibit heterogeneity.

4 Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy and safety of EA for treating PSD. Results indicate that EA outperformed conventional drug therapy in improving HAMD scores, increasing treatment response rates, and reducing adverse events. However, no significant differences were observed between EA and drug groups in improving Barthel Index or SDS scores. These findings provide preliminary evidence-based support for incorporating EA into the clinical management of PSD.

4.1 Potential mechanisms of EA in treating PSD

4.1.1 Regulation of mitochondrial function

In recent years, multiple studies have confirmed the efficacy of EA for PSD and identified potential mechanisms. Researchers found that EA increases AMPK expression in the prefrontal cortex of PSD rats, thereby improving mitochondrial function and alleviating depressive symptoms in model rats (35). In another study, researchers confirmed that EA intervention promotes cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R) and mitochondrial expression, restores mitochondrial dysfunction, and consequently improves PSD (36).

4.1.2 Regulation of monoamine neurotransmitters and neurotrophic factors

Multiple studies suggest that EA may exert antidepressant effects by modulating serotonin system function. Xu Nenggui and Yao Lulu’s team published findings in Translational Psychiatry indicating that electrical EA stimulation at Baihui and Shenting acupoints significantly enhances 5-HT neural projections from the dorsal raphe nucleus to the prefrontal cortex, restoring functional connectivity in this pathway and thereby improving depressive-like behaviors in PSD mice. Further chemogenetic inhibition experiments demonstrated that the DRN-mPFC 5-HT neural circuit is essential for EA efficacy. When this circuit was specifically suppressed, EA’s therapeutic effects were markedly attenuated (37). This finding strongly aligns with the significant improvement in HAMD scores observed in the EA group within this meta-analysis, suggesting a distinct neural circuit regulatory mechanism underlies clinical efficacy.

EA may also exert effects by modulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Researchers have found that EA applied to the Four Gates points promotes hippocampal BDNF and TrkB expression in PSD rats (38). Further studies revealed that EA enhances serum and prefrontal cortex BDNF expression in model rats. Additionally, EA was shown to increase tPA and TrkB expression in the prefrontal cortex of PSD rats, proposing that EA improves PSD by regulating the tPA/BDNF/TrkB pathway (39).

4.1.3 Regulation of inflammation and ferroptosis

Inflammation is closely associated with PSD. Studies have revealed that EA exerts its effects by regulating inflammation and ferroptosis. Li′s research demonstrated that EA reduces inflammatory factor expression in model mice, protects hippocampal neurons, and lowers TLR4, p-p38, p-NF-κB, and NLRP3 levels, validating the mechanism whereby EA acts through the TLR4/p38/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway (40). Recent studies further confirm that EA alleviates hippocampal inflammation and pyroptosis in PSD by downregulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation, suggesting NLRP3 as a potential therapeutic target for PSD (41). The association between ferroptosis and depression has been established (42), and the mechanism by which EA improves PSD through ferroptosis has been elucidated. Gao’s study revealed that EA inhibits ferroptosis in prefrontal cortical neurons to reduce neurological deficits and enhance spontaneous activity and exploratory behavior in rats (43).

In summary, current research has confirmed the definite efficacy of EA in treating PSD and identified multiple targets and pathways through which EA exerts its effects, demonstrating systemic and holistic characteristics.

4.2 Overview of meta-analysis results

Notably, the pooled results for HAMD scores and SDS in this study exhibited high heterogeneity (I2 = 89%; I2 = 97%), indicating significant clinical or methodological differences among studies. Sensitivity analysis revealed that inconsistencies in patient disease duration, drug dosage, and types were likely primary sources of heterogeneity. For example, the shorter disease duration in Huang et al.’s (19) study and the wider range of drug dosages in the control group of Long et al.’s (23) study may have impacted the consistency of results. Future studies should standardize intervention protocols and patient stratification to enhance the reliability of findings.

Regarding secondary outcomes, no significant differences were observed between EA and medication in improving the Barthel Index and SDS scores. This may stem from limited sample sizes or varying sensitivities of assessment tools across different dimensions of psychological and functional status. Furthermore, the Barthel Index primarily reflects activities of daily living, whereas the SDS is a self-report scale; its assessment of depression severity may differ from clinician-rated HAMD scores.

Furthermore, all included studies were conducted in China, and most exhibited suboptimal methodological quality, particularly with inadequate implementation of blinding and allocation concealment, potentially introducing implementation and measurement biases. The findings of this study are primarily applicable to the Chinese population and should be applied with caution to other regions or populations. Future research requires more high-quality, multicenter, large-sample randomized controlled trials to enhance the generalizability and strength of evidence.

Furthermore, this study applied more precise inclusion criteria for the experimental group. For the experimental group, the studies included in our analysis featured subjects receiving only EA treatment, while the control groups received only conventional drug therapy. This allows for a more precise analysis of the advantages and limitations of acupuncture compared to conventional therapies. Previous meta-analyses (44), however, appear to have applied broader criteria for intervention methods, incorporating studies using various acupuncture techniques such as EA, body acupuncture, auricular acupuncture, and scalp acupuncture. While this approach yielded more comprehensive results, it lacked the necessary precision.

5 Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, all included studies originated from China, potentially introducing regional bias and limiting the generalizability of findings. Second, most studies inadequately described specific methods for random sequence generation and allocation concealment, and incomplete blinding may have introduced implementation and measurement biases. Furthermore, the number of studies for certain outcome measures was limited—for example, only three studies included the Barthel Index—compromising the robustness of results. Finally, funnel plots suggest potential publication bias, particularly with small-sample studies showing a tendency toward positive results, indicating that negative findings may be underreported.

6 Conclusion

This systematic review of existing clinical trials preliminarily confirms the efficacy of EA in improving core PSD symptoms and its safety profile. Future research should focus on multicenter, large-sample, methodologically rigorous randomized controlled trials to further validate the long-term efficacy and mechanisms of EA, and to explore response variations across different patient subgroups.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YG: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HH: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HY: Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JG: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZZ: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1732787/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Gong S Wang S Wang J Yin Y Wu Y . The mediating effect of serum cortisol between stigma and post-stroke depression in stroke patients. Front Public Health. (2025) 13:1682528. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1682528,

2.

Lin F Zhou M . Development and validation of a risk prediction model for depression in patients with stroke. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. (2025) 40:1082–90. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acaf021,

3.

Jørgensen TS Wium-Andersen IK Wium-Andersen MK Jørgensen MB Prescott E Maartensson S et al . Incidence of depression after stroke, and associated risk factors and mortality outcomes, in a large cohort of Danish patients. JAMA Psychiatr. (2016) 73:1032–40. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1932,

4.

Zhou H Wei YJ Xie GY . Research progress on post-stroke depression. Exp Neurol. (2024) 373:114660. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2023.114660,

5.

van Mierlo ML van Heugten CM Post MW Hajós TR Kappelle LJ Visser-Meily JM . Quality of life during the first two years Post stroke: the Restore4Stroke cohort study. Cerebrovas Dis (Basel, Switzerland). (2016) 41:19–26. doi: 10.1159/000441197,

6.

Bartoli F Lillia N Lax A Crocamo C Mantero V Carrà G et al . Depression after stroke and risk of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke Res Treat. (2013) 2013:862978. doi: 10.1155/2013/862978,

7.

Bartoli F Di Brita C Crocamo C Clerici M Carrà G . Early post-stroke depression and mortality: meta-analysis and meta-regression. Front Psych. (2018) 9:530. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00530,

8.

Fang J Cheng Q . Etiological mechanisms of post-stroke depression: a review. Neurol Res. (2009) 31:904–9. doi: 10.1179/174313209X385752,

9.

Taylor SE Way BM Welch WT Hilmert CJ Lehman BJ Eisenberger NI . Early family environment, current adversity, the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism, and depressive symptomatology. Biol Psychiatry. (2006) 60:671–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.019,

10.

Raggi A Serretti A Ferri R . A comprehensive overview of post-stroke depression treatment options. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (2024) 39:127–38. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000532,

11.

Anderson HD Pace WD Libby AM West DR Valuck RJ . Rates of 5 common antidepressant side effects among new adult and adolescent cases of depression: a retrospective US claims study. Clin Ther. (2012) 34:113–23. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.11.024

12.

Dodd S Mitchell PB Bauer M Yatham L Young AH Kennedy SH et al . Monitoring for antidepressant-associated adverse events in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: an international consensus statement. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2018) 19:330–48. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2017.1379609,

13.

Bi C Lin S Jiang L . A comparative study of different therapeutic approaches for post stroke depression. China Pract Med. (2010) 5:71–3.

14.

Chen J Xinzhi WJ Wang J Zang L . Clinical study on EA for enhancing brain health and calming the mind in the treatment of post stroke depression. Liaoning J Tradit Chin Med. (2005) 32:464–5.

15.

Chu Y Wang C Zhang H . Clinical observation of 72 cases of acupuncture treatment for post stroke depression. Chin J Geriatr. (2007) 27

16.

Dong J Sun W Wang S Wu Z Liu F . Clinical observation on head point-through-point electroacupuncture for treatment of poststroke depression. Chin Acupunct Moxibustion. (2007) 27

17.

Dong J Xu Y Zhang Y Li Y Chen C . Clinical study on post stroke depression treated with electro-acupuncture scalp point-through-point therapy. Chin J Tradit Med Sci Technol. (2017) 24

18.

Hong Z Wang Z Zhang S Ma R . Observation on effect of "Xingshen Jieyu" acupuncture method in treating post stroke depression. J Zhejiang Chin Med Univ. (2015) 39

19.

Huang S Wei Y Zhang Z . Combination of electroacupuncture on “shen-wu-xing points” and western medicine for poststroke depression: a randomized controlled trial. Shanghai J Tradit Chin Med. (2014) 48

20.

Kang W Yang B . Electro-acupuncture therapy for the post-stroke depression. J Clin Acupunct Moxibustion. (2014) 30

21.

Li J Ye X Cheng R Zhu G Yang T . Effect of electroacupuncture on regional cerebral blood flow in patients with post-stroke depression. Chin J Rehabil Theory Pract. (2015) 21

22.

Li X Shi G D Q . Electroacupuncture at the san Shen and Si guan points in the treatment of 70 patients with post-stroke depression. Heilongjiang J Tradit Chin Med. (2013) 42

23.

Long H Tan P Feng J L M . Clinical observation of electroacupuncture in the treatment of post stroke depression. J Clin Psychiatry. (2004) 14

24.

Nie B Nie T . Clinical study on electroacupuncture treatment for post-stroke depression. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. (2010) 8. doi: 10.1007/s11726-010-0444-6

25.

Peng H Ye J He X Tan J Zhang Z . A randomised controlled clinical trial of electroacupuncture versus fluoxetine capsules for post-stroke depression. Jilin J Chin Med. (2011) 31

26.

Suhua C . Observational study on the efficacy of electroacupuncture therapy for post stroke depression. Chin J Prim Med Pharm. (2012) 19:3094–5.

27.

Wu X H X . A controlled study on the treatment of post-stroke depression using electroacupuncture at the Sanyinjiao and Yintang points. West J Tradit Chin Med. (2007) 20

28.

Xu G M G . Curative effect observation on electroacupuncture to treat elderly post-stroke depression. Chin J Convalesc Med. (2015) 24

29.

Yanwu W . High-frequency electroacupuncture treatment for post-stroke depression in 40 cases. Zhejiang J Tradit Chin Med. (2010) 45:62.

30.

Yuan Z Jianhong J Guoying Z . Treatment of 1 45 post-stroke depression (PSD) patients with electric acupunctur. J Shaanxi Coll Tradit Chin Med. (2010) 33:78–80.

31.

Zhiming Z . A controlled study of electroacupuncture versus pharmacotherapy for post-stroke depression. China Med Herald. (2007) 4:23–128.

32.

Zhu G Ye X Li J Wen W Tian L Yang T . Clinical controlled study on electroacupuncture opening the ‘four gates’ versus fluoxetine hydrochloride in the treatment of post-stroke depression. Zhejiang J Integr Tradit Chin West Med. (2012) 22:865–7.

33.

Wei D . Observational study on the efficacy of electroacupuncture in treating post-stroke depression. Hubei J Tradit Chin Med. (2009) 31:22–3.

34.

Jinglan Z Fei W . Electroacupuncture ear point therapy for post-stroke depression: a study of 34 cases. J Extern Ther Tradit Chin Med. (2013) 22:46–7.

35.

Ding Z Gao J Feng Y Wang M Zhao H Wu R et al . Electroacupuncture ameliorates depression-like behaviors in post-stroke rats via activating AMPK-mediated mitochondrial function. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2023) 19:2657–71. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S436177,

36.

Hu G Zhou C Wang J Ma X Ma H Yu H et al . Electroacupuncture treatment ameliorates depressive-like behavior and cognitive dysfunction via CB1R dependent mitochondria biogenesis after experimental global cerebral ischemic stroke. Front Cell Neurosci. (2023) 17:1135227. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2023.1135227,

37.

Deng B Di W Long H He Q Jiang Z Nan T et al . The involvement of 5-HT was necessary for EA-mediated improvement of post-stroke depression. Transl Psychiatry. (2025) 15:382. doi: 10.1038/s41398-025-03621-y,

38.

Kang Z Ye H Chen T Zhang P . Effect of electroacupuncture at Siguan acupoints on expression of BDNF and TrkB proteins in the hippocampus of post-stroke depression rats. J Mole Neurosci. (2021) 71:2165–71. doi: 10.1007/s12031-021-01844-4,

39.

Dong H Qin YQ Sun YC Yao HJ Cheng XK Yu Y et al . Electroacupuncture ameliorates depressive-like behaviors in poststroke rats via activating the tPA/BDNF/TrkB pathway. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2021) 17:1057–67. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S298540,

40.

Li M Yang F Zhang X Yang H He X Mao Z et al . Electroacupuncture attenuates depressive-like behaviors in poststroke depression mice through promoting hippocampal neurogenesis and inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway. Neuroreport. (2024) 35:947–60. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000002088,

41.

Cai W Wei XF Tao L Shen WD . Antidepressant-like effects of electroacupuncture by regulating NLRP3-mediated hippocampal inflammation and pyroptosis in rats with post-stroke depression. Brain Behav. (2025) 15:e70670. doi: 10.1002/brb3.70670,

42.

Feng X Zhang W Liu X Wang Q Dang X Han J et al . Ferroptosis-associated signaling pathways and therapeutic approaches in depression. Front Neurosci. (2025) 19:1559597. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2025.1559597,

43.

Gao J Song X Feng Y Wu L Ding Z Qi S et al . Electroacupuncture ameliorates depression-like behaviors in rats with post-stroke depression by inhibiting ferroptosis in the prefrontal cortex. Front Neurosci. (2024) 18:1422638. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2024.1422638,

44.

Zhang Z Xue K Li H Yan M Cui J . Electroacupuncture for post-stroke depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Neurol. (2025) 16:1671808. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1671808,

Summary

Keywords

depression, electroacupuncture, meta-analysis, stroke, systematic review

Citation

Liang Y, Gu Y, Han H, Yin H, Gao J, Hou L, Ning W and Zheng Z (2026) Efficacy and safety of electroacupuncture for post-stroke depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 16:1732787. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1732787

Received

26 October 2025

Revised

22 December 2025

Accepted

25 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Tianye Hu, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University, China

Reviewed by

Hantong Hu, Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, China

Kelin He, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Liang, Gu, Han, Yin, Gao, Hou, Ning and Zheng.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zuncheng Zheng, zhengzc1965@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.