Abstract

Background:

Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH) is a devastating stroke subtype. Accelerating hematoma clearance is a critical therapeutic goal. This study evaluated non-invasive pulsed ultrasound for enhancing hematoma clearance, edema resolution, and recovery post-ICH.

Methods:

Twenty-nine rats with striatal autologous blood-induced ICH were randomized into control (n = 11), 2 MHz ultrasound (n = 7), and 8 MHz ultrasound (n = 11) groups. Ultrasound treatment (60 min/day) was applied for 7 consecutive days following ICH induction. Hematoma volume and perihematomal edema (PHE) were assessed by T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) and susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) at days 1 and 7 post-ICH. Neurological function was assessed by corner turn and cylinder tests at baseline and days 1, 3, and 7.

Results:

Non-invasive pulsed ultrasound significantly enhanced hematoma clearance (2 MHz: 47.7%; 8 MHz: 47.8% vs. control: 20.4%, p < 0.01) and PHE resolution (2 MHz: 53.9%; 8 MHz: 71.8% vs. control: 31.1%, p < 0.05). Behavioral tests showed reduced right-turn bias and forelimb asymmetry in ultrasound groups (p < 0.05). No frequency difference was found.

Conclusion:

Non-invasive pulsed ultrasound significantly enhances hematoma clearance, reduces edema, and improves functional recovery post-ICH, supporting its translational potential.

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a particularly devastating subtype of stroke, characterized by high morbidity and mortality, with limited effective therapeutic options (1). Although ICH accounts for only 10–25% of all strokes globally (2, 3), its 30-day mortality rate remains as high as 50% (4–6). The dual-injury paradigm, consisting of primary mechanical disruption and secondary neurotoxicity from hemoglobin degradation products, drives progressive neurological deterioration (7). The increase of 1 mL in absolute ICH volume leads to a 7% greater likelihood for patients to shift from independence to dependence (8).

Current management strategies for ICH remain largely supportive, focusing on blood pressure control, hematoma evacuation, and reducing secondary injury (9). However, clinical trials, investigating surgical hematoma removal, such as STICH (10), MISTIE (11), and CLEAR (12), have failed to demonstrate significant survival benefits. Notably, the MISTIE-III trial which aimed to refine minimally invasive techniques, also showed no overall improvement in functional outcomes compared to standard medical care, despite achieving hematoma volume reduction (13). Furthermore, the recent ENRICH trial revealed a critical nuance: minimally invasive evacuation significantly improved functional recovery in patients with lobar hemorrhages, yet demonstrated no efficacy for those with basal ganglia hemorrhages (14). As a result, alternative non-invasive therapeutic strategies are being actively explored to enhance hematoma clearance and promote neurological recovery.

Emerging as a promising non-invasive modality, ultrasound has recently garnered significant attention for its neuroprotective potential across multiple central nervous system disorders. Notably, preclinical studies have demonstrated its therapeutic utility in ischemic stroke (15), Parkinson’s disease (16), and traumatic brain injury (17). Low-intensity focused ultrasound reduces immunoglobulin G (IgG) deposition in the brain, indicating decreased blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption, thereby contributing to neuroprotection following ischemic stroke (15). Similarly, in TBI, low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) significantly attenuates neuroinflammation by decreasing MMP-9 activity, neutrophil infiltration, and microglial activation (17). Moreover, studies suggest that ultrasound, through its cavitation and mechanical effects, can effectively fragment thrombi and calcified plaques into micron-sized particles, thereby facilitating their clearance (18, 19). In addition, continuous monitoring with 2-MHz transcranial Doppler (TCD) during tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) infusion for ischemic stroke has been associated with a high rate of complete recanalization and significant clinical recovery, likely by enhancing thrombolysis through increased clot surface exposure to tPA (20). Despite these promising findings, it remains unclear whether treatment with non-invasive pulsed ultrasound can alleviate ICH-induced detrimental outcomes and inflammatory responses.

In this study, we investigated the effects of non-invasive pulsed ultrasound (2 MHz and 8 MHz) on hematoma clearance, perihematomal edema (PHE) absorption, and neurological recovery in a rodent model of ICH. The 2 MHz frequency was chosen because it corresponds to the standard operating frequency of clinical transcranial Doppler systems and has well-established safety, skull penetration characteristics, and translational relevance. In contrast, 8 MHz ultrasound was included as a higher-frequency comparator to investigate whether ultrasound-mediated hematoma clearance and perihematomal edema resolution exhibit frequency-dependent characteristics.

We hypothesized that ultrasound stimulation would enhance hematoma resolution and attenuate secondary brain injury, thus improving functional outcomes. Our findings provide insight into the potential translational applications of non-invasive pulsed ultrasound as a novel therapeutic strategy for ICH management.

Methods

Animal model of intracerebral hemorrhage

All animal procedure protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Beijing Neurosurgery Research Institute. The study complies with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting in vivo experiments. Twenty-nine adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (250–350 g, Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.) were used. The rats had free access to food and water before and after surgery and were housed in a 12-h light/dark cycle. The animals were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (45 mg/kg), and body temperature was maintained at 37 °C using a feedback-controlled heating pad. The rats were placed in a stereotactic frame (RWD, Shenzhen, China) and a cranial burr hole (1 mm) was drilled on the right coronal suture 3.5 mm lateral to the midline. Autologous arterial blood was obtained from the right femoral artery cannulation with a polyethylene catheter and injected immediately after collection, at a rate of 6 μL/min using a 26-gage needle at the coordinates: 0.2 mm anterior, 5.5 mm lateral, and 3.5 mm ventral to the bregma. Blood withdrawal and intracerebral injection were performed consecutively without storage or intentional delay, within a short and consistent time window, to minimize the possibility of ex vivo clot formation prior to injection. The needle remained in position for an additional 10 min before being gently removed. The burr hole was filled with bone wax, and the skin incision was sutured closed.

Treatment allocation

Animals were randomly assigned to treatment conditions. Randomization was conducted using the random number generator function in Microsoft Excel. A total of 29 rats were divided into three experimental conditions (Figure 1A). (Experiment 1) Rats received an intracerebral injection of 60 μL autologous whole blood into the right basal ganglia (n = 11). (Experiment 2) Rats received an infusion of 60 μL autologous whole blood and 2 MHz ultrasound treatment for 60 min per day over 7 consecutive days (n = 7). (Experiment 3) Rats received an infusion of 60 μL autologous whole blood and 8 MHz ultrasound treatment for 60 min per day over 7 consecutive days (n = 11).

Figure 1

Experimental design. (A) Flow chart of the experimental procedure. Twenty-nine rats were randomized into control (ICH), ICH + 2 MHz ultrasound, and ICH + 8 MHz ultrasound groups. All animals were included in behavioral assessments conducted at baseline and at days 1, 3, and 7 post-ICH. A predefined longitudinal imaging subsample (n = 6 per group) was used for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) analyses at days 1 and 7 post-ICH. (B) Schematic diagram of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound setup.

All 29 animals were included in behavioral assessments, which were conducted at baseline (day 0) and at days 1, 3, and 7 post-ICH (n = 7 for the 2 MHz group, n = 11 for the ICH and 8 MHz groups). For magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) analyses, a predefined longitudinal imaging subsample was used. Six rats per group (n = 6/group) were randomly selected prior to imaging to undergo T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) and susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) at days 1 and 7 post-ICH. No animals were excluded from MRI analyses based on imaging outcomes.

Pulsed ultrasound apparatus and exposure protocol

A non-invasive pulsed ultrasound system (Doppler-Box™, Compumedics Germany GmbH, DWL, Singen, Germany) equipped with dual-frequency probes (2 MHz and 8 MHz) was employed in this study. Although commercially labeled as a TCD device, the system was used exclusively as a source of therapeutic pulsed ultrasound exposure, rather than for diagnostic Doppler blood flow velocity measurements. No Doppler-specific functions, including spectral analysis, sample volume selection, gain adjustment, or flow velocity measurement, were applied.

Both probes were operated in pulsed-wave mode. Except for the spatial-peak temporal-average intensity (I_SPTA), which was set according to the system’s standard output settings, all other acoustic parameters were probe-inherent, manufacturer-defined presets and were not user-adjustable. Accordingly, these parameters were kept constant across all animals and experimental sessions and were not treated as experimental variables. For the 2-MHz probe, the maximum mechanical index (MI) was 0.5, the maximum thermal index was 2.8, I_SPTA was 420 mW/cm2, the peak negative acoustic pressure was 0.65 MPa, the pulse repetition frequency (PRF) was 7,000 Hz, and the pulse duration was 3.78 μs. For the 8-MHz probe, the maximum MI was 0.1, I_SPTA was 200 mW/cm2, the peak negative acoustic pressure was 0.41 MPa, the PRF was 7,000 Hz, and the pulse duration was 9.11 μs. All ultrasound exposures were performed within manufacturer-defined safety limits and in accordance with the ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) principle.

Ultrasound coupling gel was applied to ensure appropriate acoustic impedance matching between the transducer and the rat skull. During ultrasound exposure and MRI procedures, rats were anesthetized with a 2% isoflurane/air mixture, and body temperature was maintained using a forced-air heating system.

The ultrasound transducer was stereotactically mounted (RWD Life Science, China) and positioned on the intact skull surface above the hematoma location, corresponding to the cranial burr hole used for ICH induction. Ultrasound was delivered transcranially to the underlying brain tissue. Because no Doppler sampling gate was used, parameters such as insonation depth selection and sample volume positioning are not applicable in this therapeutic context. Given the small skull thickness and limited scalp-to-brain distance in rats, transcranial ultrasound exposure from the cranial surface resulted in effective insonation of the cortical and perihematomal brain regions for both probe frequencies. Ultrasound treatment was administered once daily for 60 min/day over 7 consecutive days following ICH induction (Figure 1B).

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI was performed on a 7.0-T scanner (Bruker, Germany). During the MRI scans, the rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (45 mg/kg). Their body temperature was maintained at approximately 37 °C. T2WI were acquired using a fat-suppressed RARE sequence (TR/TE = 3380/41 ms, field of view = 55 × 55 mm2, matrix size = 384 × 384, in-plane resolution = 0.143 × 0.143 mm2, slice thickness = 0.8 mm), with 27 consecutive coronal slices acquired to ensure full coverage of the hematoma, ventricular system, and surrounding brain tissue, for lesion volume assessment. SWI (TR/TE = 20/10 ms, field of view = 35 × 35 mm2, matrix size = 384 × 384, in-plane resolution = 0.091 × 0.091 mm2, slice thickness = 0.5 mm) was performed to quantify hematoma volume with 33 consecutive coronal slices acquired for complete lesion coverage. T2WI and SWI datasets were manually segmented using ITK-SNAP (version 3.8.01), with hematoma and lesion volumes calculated by tracing regions of interest (ROIs). For quantitative analysis, ROIs were delineated on all consecutive slices covering the hematoma, ventricular system, and perihematomal region. Volumetric measurements were obtained by summing ROI areas across slices and multiplying by slice thickness. This volumetric analysis strategy applies to all MRI-based outcome measures, including parenchymal hematoma, intraventricular hematoma, intracerebral hematoma, and PHE. PHE volume was derived by subtracting hematoma volume from total lesion volume. MRI scans were conducted at days 1 and 7 post-ICH. In the present study, hematoma clearance rates were used as primary endpoint, which was calculated as: (hematoma volume at day 1- hematoma volume at day 7) hematoma volume at day 1 × 100%. In addition, PHE volume clearance rate was evaluated as well, which was calculated as:(PHE volume at day 1- PHE volume at day 7)/PHE volume at day 1 × 100%. All MRI analyses were conducted by two independent investigators blinded to group allocation. Each investigator independently analyzed the complete MRI dataset, including all animals and time points, using the same predefined ROI delineation protocol.

Behavioral tests

The corner turn test and forelimb use asymmetry were used for neurological assessment as previously described (21). Both tests were performed at baseline (day 0) and post-ICH days 1, 3, and 7. Forelimb use asymmetry was quantified by recording the frequency of ipsilateral (I), contralateral (C), and bilateral (B) forelimb contacts during vertical rearing activity. The asymmetry score was calculated as: (I − C)/ (I + C + B) × 100%. In the corner turn test, rats freely entered a 30°-angled corner, and their turning direction (left/right) was recorded over 20 consecutive trials. The percentage of right turns relative to total trials was computed. All behavioral assessments were evaluated by an investigator blinded to experimental groups.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). One-way and two-way ANOVA were employed to determine significant differences between groups. Bonferroni post hoc analysis was utilized for multiple comparisons correction. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, United States).

Results

Ultrasound treatment and parenchymal hematoma clearance

Parenchymal hematoma size was evaluated using SWI at days 1 and 7 following intracerebral injection of 60 μL autologous arterial blood (Figure 2A). As shown in Figure 2B, ultrasound treatment significantly enhanced hematoma clearance rates in the ICH + 2 MHz group compared to untreated ICH controls (47.7 ± 6.86% vs. 20.40 ± 4.62%, p = 0.002). Similarly, the ICH + 8 MHz group also exhibited significantly higher hematoma clearance rates than untreated ICH controls (47.82 ± 5.10% vs. 20.40 ± 4.62%, p = 0.011). Notably, no intergroup difference was detected between the 2 MHz and 8 MHz ultrasound protocols (47.7 ± 6.86% vs. 47.82 ± 5.10%, p > 0.05).

Figure 2

Ultrasound treatment enhances parenchymal hematoma clearance in a frequency-independent manner. (A) Representative SWI scans at days 1 and 7 post-ICH. (B) Quantification of hematoma clearance rates in control ICH, ICH + 2 MHz, and ICH + 8 MHz groups (n = 6/group). Individual data points represent single animals. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. ICH group (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction). Representative images are shown for visualization purposes, whereas quantitative analyses were based on multi-slice volumetric measurements.

Ultrasound treatment and intraventricular hematoma clearance

Consistent with parenchymal hematoma analysis, intraventricular hematoma volume was serially assessed via SWI at days 1 and 7 post-ICH (Figure 3A). As shown in Figure 3B, the 2 MHz ultrasound group exhibited significantly enhanced intraventricular hematoma clearance compared to the control group (52.22 ± 6.60% vs. 23.17 ± 3.34%, p = 0.003). In contrast, the 8 MHz ultrasound group did not show a significant therapeutic effect on intraventricular hematoma clearance (36.9 ± 4.69% vs. 23.17 ± 3.34%, p > 0.05). Interprotocol comparison revealed no statistical difference between 2 MHz and 8 MHz regimens (52.22 ± 6.60% vs. 36.9 ± 4.69%, p > 0.05).

Figure 3

2 MHz ultrasound preferentially enhances intraventricular hemorrhage resolution. (A) Representative SWI scans demonstrating temporal changes in intraventricular hematoma volume. (B) Quantitative clearance rates stratified by ultrasound frequency (n = 6/group). Individual data points represent single animals. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01 vs. ICH controls (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction). Representative images are shown for visualization purposes, whereas quantitative analyses were based on multi-slice volumetric measurements.

Ultrasound treatment and intracerebral hematoma clearance

Intracerebral hemorrhage volume (parenchymal + intraventricular) was longitudinally monitored via SWI at days 1 and 7 post-ICH induction (Figure 4A). As shown in Figure 4B, the 2 MHz ultrasound group demonstrated significantly superior clearance efficacy compared to the control group (50.72 ± 6.51% vs. 22.36 ± 2.88%, p = 0.002). In contrast, the 8 MHz ultrasound group did not achieve statistical significance in clearance efficacy (39.80 ± 4.18% vs. 22.36 ± 2.88%, p > 0.05). Inter-frequency comparison showed no statistical difference between protocols (50.72 ± 6.51% vs. 39.80 ± 4.18%, p > 0.05).

Figure 4

2 MHz ultrasound enhances intracerebral hemorrhage clearance. (A) Representative SWI scans showing hematoma dynamics. (B) Quantitative analysis of hemorrhage clearance rates (n = 6/group). Individual data points represent single animals. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01 vs. ICH controls (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test). Representative images are shown for visualization purposes, whereas quantitative analyses were based on multi-slice volumetric measurements.

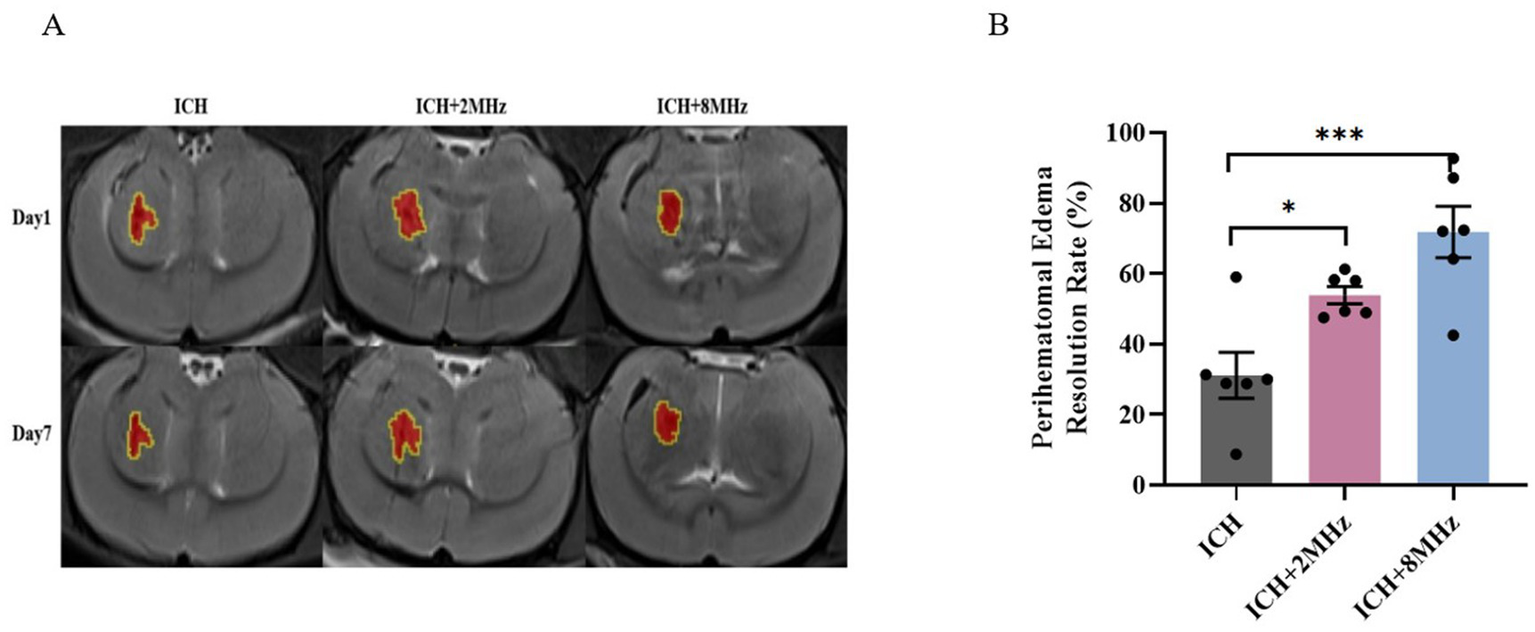

Ultrasound treatment and PHE

Lesion progression was longitudinally monitored via T2WI at days 1 and 7 post-ICH induction (Figure 5A). PHE volume was calculated as [Lesion volume – Parenchymal hematoma volume] (Figure 5A). As shown in Figure 5B ultrasound treatment significantly enhanced PHE resolution rate in the ICH + 2 MHz group compared to untreated ICH controls (53.91 ± 2.42% vs. 31.15 ± 6.55%, p = 0.043). Similarly, the ICH + 8 MHz group also exhibited significantly higher PHE resolution rate than untreated ICH controls (71.83 ± 7.28% vs. 31.15 ± 6.55%, p = 0.001). Inter-frequency comparison revealed no statistical significance (71.83 ± 7.28% vs. 53.91 ± 2.42%, p > 0.05).

Figure 5

Frequency-specific ultrasound enhancement of PHE resolution. (A) Representative T2WI scans at days 1 and 7 post-ICH. Red areas: Parenchymal hematoma; Yellow contours: Total lesion boundaries. (B) Quantitative analysis of PHE volume changes (n = 6/group). Individual data points represent single animals. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 vs. ICH controls). Representative images are shown for visualization purposes, whereas quantitative analyses were based on multi-slice volumetric measurements.

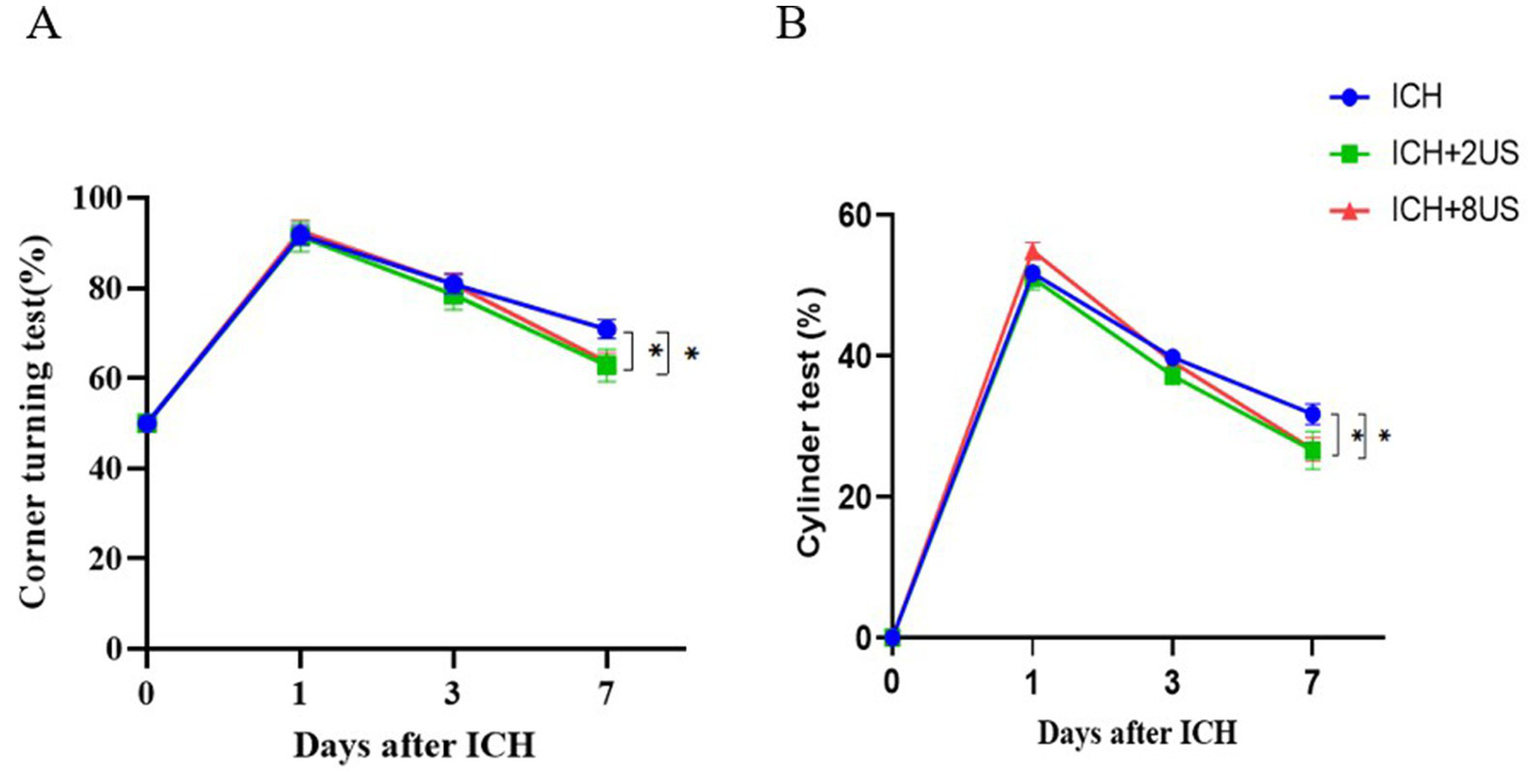

Ultrasound treatment and neurological deficits improvement

Neurological function was longitudinally assessed using corner turning and cylinder tests at baseline (pre-surgery) and at days 1, 3, 7 post-ICH to evaluate ultrasound-mediated functional recovery. ICH induction precipitated significant neurological deterioration (vs baseline, p < 0.001), which was attenuated by ultrasound treatment at day 7 (p < 0.05).

Corner test analysis demonstrated:2 MHz: 62.86 ± 3.60% vs. Control 70.91 ± 2.11% (p = 0.049); 8 MHz: 63.64 ± 2.03% vs. Control 70.91 ± 2.11% (p = 0.041) (Figure 6A). Cylinder test quantification revealed analogous improvements:2 MHz: 26.56 ± 2.72% vs. Control 31.75 ± 1.48% (p = 0.022); 8 MHz: 26.73 ± 1.65% vs. Control 31.75 ± 1.48% (p = 0.010) (Figure 6B). Interprotocol comparisons showed no frequency-dependent differences (p > 0.05).

Figure 6

Ultrasound treatment rescues early neurological deficits post-ICH. (A) Corner test performance. (B) Cylinder test forelimb asymmetry scores. Data expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 7 for ICH + 2 MHz; n = 11 for ICH/ICH + 8 MHz). **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 vs. ICH controls (two-way RM ANOVA with Bonferroni correction).

Discussion

In this study, we systematically evaluated the effects of non-invasive pulsed ultrasound on parenchymal hematoma clearance, PHE resolution, and neurological recovery in a rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Our findings demonstrate that: (1) Non-invasive pulsed ultrasound treatment significantly accelerated parenchymal hematoma clearance and effectively promoted the resolution of PHE; (2) Non-invasive pulsed ultrasound treatment significantly attenuated secondary brain injury following ICH, as evidenced by improved neurological function and reduced motor asymmetry in both the corner turn and cylinder tests (p < 0.05). These results highlight the translational potential of non-invasive pulsed ultrasound therapy for enhancing hematoma clearance, mitigating secondary injury, and improving functional outcomes after ICH.

Masomi-Bornwasser et al. previously investigated the thrombolytic effects of ultrasound in both in vitro and in vivo ICH models (22, 23). In vitro clot model, high-frequency ultrasound (10 MHz) significantly reduced relative clot weight (40.2% vs. 61%) even without pharmacologic agents, especially in large (50 mL) or aged (48-h) clots, underscoring the intrinsic thrombolytic capacity of ultrasound (22). In a porcine model, ultrasound-assisted drainage achieved an 18 ± 8% reduction in hematoma volume, superior to drainage alone (2 ± 1%) (23). These findings highlight the mechanical disruption of fibrin networks by ultrasound, though its standalone efficacy in vivo remains limited. Notably, the in vitro model lacks physiological complexity such as metabolism, inflammation, and blood–brain barrier integrity, while the in vivo porcine model, despite anatomical relevance, requires invasive procedures that may hinder clinical translation.

In another recent study, Su et al. demonstrated that LIPUS exerts anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects by modulating glia-mediated inflammation via the PI3K/Akt–NF-κB signaling pathway (24). Although this work provided valuable mechanistic insights, it primarily focused on molecular pathways rather than therapeutic outcomes.

Building upon these findings, our study represents a translational advancement by utilizing non-invasive pulsed ultrasound to assess therapeutic efficacy in ICH. Through stereotactic ultrasound delivery, longitudinal MRI-based hematoma quantification, and behavioral assessments, we demonstrated that non-invasive pulsed ultrasound significantly promotes hematoma clearance, reduces PHE, and improves functional recovery. This approach bridges the gap between mechanistic investigations and clinically relevant interventions, underscoring the potential of ultrasound as a non-invasive therapy for ICH.

Larger hematoma volumes are closely associated with poor neurological outcomes (25). Our study showed that non-invasive pulsed ultrasound significantly enhanced hematoma clearance (47.7 ± 6.86% vs. 20.40 ± 4.62%, p = 0.002). This is consistent with in vitro evidence demonstrating that ultrasound alone can achieve clot lysis efficiencies comparable to recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) monotherapy (26). Mechanistically, ultrasound in the kHz–MHz range has been shown to synergistically enhance rtPA activity; for example, 1 MHz irradiation increased clot degradation rates by 1.8-fold compared to rtPA alone (27). Clinical studies have further supported this, showing that ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke improves 24-h outcomes (20). Our findings suggest that non-invasive pulsed ultrasound may be a promising therapeutic approach for ICH, potentially applicable in clinical contexts.

PHE is a critical pathological process that leads to delayed neurological deterioration after intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), driven by thrombin activation, immune dysregulation, BBB dysfunction, and hemoglobin cytotoxicity (28–31). The rapid expansion of PHE exacerbates intracranial hypertension, imposing mechanical stress on brain tissue and causing neuronal injury (32). In our study, non-invasive pulsed ultrasound treatment facilitated the absorption of PHE. Previous studies have demonstrated that transcranial ultrasound–based stimulation, including transcranial focused ultrasound and LIPUS exerts neuroregulatory and neuroprotective effects across various neurological conditions (17, 33). In a middle cerebral artery occlusion mouse model, low-intensity, low-frequency (0.5 MHz) transcranial focused ultrasound applied at 2, 4, and 8 h after ischemia enhanced tight junction protein ZO-1 expression, reduced IgG leakage, improved blood–brain barrier integrity, and attenuated TNF-α secretion and MMP-9 activation, thereby reducing brain edema volume (33). Similarly, transcranial LIPUS demonstrated significant neuroprotective effects in a traumatic brain injury mouse model by alleviating brain edema, decreasing MMP-9 activity, mitigating neutrophil infiltration, and inhibiting microglial activation (17). These findings suggest that the neuroprotective effects of LIPUS are associated with its ability to mitigate early inflammatory events. Our results are consistent with these prior studies, indicating that non-invasive pulsed ultrasound may promote PHE resolution by modulating neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory pathways. However, further research is needed to elucidate the precise molecular mechanisms underlying these therapeutic effects.

An important aspect of the present study is the comparison between 2 MHz and 8 MHz pulsed ultrasound exposure. Despite their distinct acoustic properties, both frequencies significantly promoted parenchymal hematoma clearance, reduced perihematomal edema, and improved neurological function compared with untreated ICH controls. Notably, no marked superiority of one frequency over the other was observed with respect to parenchymal hematoma resolution, suggesting that, within the frequency range examined, the overall therapeutic effects of ultrasound are not exclusively determined by frequency alone. Instead, these benefits are likely mediated by shared mechanical and biological mechanisms, such as microstructural clot modulation, altered interstitial transport, and modulation of local inflammatory responses.

By comparison, differences between frequencies emerged in intraventricular hemorrhage resolution, where 2 MHz ultrasound demonstrated a more pronounced effect than 8 MHz. This finding may be related to the greater penetration depth and broader acoustic field associated with lower-frequency ultrasound, which could be advantageous for influencing deeper or ventricular components of hemorrhage. In contrast, the higher-frequency 8 MHz ultrasound may generate more spatially confined mechanical stimulation, which appears sufficient for parenchymal hematoma but less effective for intraventricular regions.

The mechanisms underlying ultrasound-mediated clearance of parenchymal hematoma and perihematomal edema are not fully understood. However, based on previous research, we can propose several potential modes of action: (1) Mechanical Effects: Ultrasound waves can fragment thrombi through vibrations, breaking them into smaller particles and accelerating their metabolic clearance (18). Additionally, acoustic streaming generates shear forces that disrupt thrombi (34). (2) Cavitation Effects: Microbubbles oscillate and implode under ultrasound, disrupting thrombi and promoting their dissolution (35, 36). (3) Hemodynamic Modulation: Ultrasound application is thought to improve hemodynamics by augmenting blood flow in brain tissue (37, 38). This augmentation of blood flow velocity and circulation facilitates the transportation of mononuclear phagocytes to the perilesional area, thus promoting more efficient hematoma clearance. (4) Cell Membrane Alterations: Ultrasound increases cell permeability, enhancing fluid and solute exchange, which may accelerate hematoma absorption (39, 40). (5) Ultrasound reduces inflammation by inhibiting inflammatory factor production, thereby reducing edema and improving the local microenvironment (32, 41). (6) Neuroprotective Effects: Studies have shown that ultrasound exerts neuroprotective effects on nerve cells (15). This potentially alleviates cellular stress and promotes neuronal survival, thus mitigating damage to the surrounding brain tissue caused by hematomas. These mechanisms likely interact synergistically to promote hematoma clearance, perihematomal edema resorption, and brain tissue repair. Future research should focus on elucidating the specific roles and interactions of these mechanisms to optimize therapeutic strategies.

This study has several limitations. First, the specific biological mechanisms through which non-invasive pulsed ultrasound mitigates ICH-induced damage remain to be clarified. Second, the findings are based on a single-center rodent model, which may not fully recapitulate human pathophysiology. Multicenter studies utilizing standardized protocols are needed to validate reproducibility. Finally, the translational relevance of our findings should be evaluated in large animal models, such as pigs, which offer more accurate anatomical and acoustic properties relevant to clinical application.

Conclusion

Non-invasive pulsed ultrasound facilitated hematoma clearance, the resorption of perihematomal edema, and mitigated neuronal damage following ICH. Our findings demonstrate that non-invasive pulsed ultrasound treatment represents a potential therapeutic strategy for ICH.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

All experimental protocols involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Animal Welfare Ethics Committee of the Beijing Neurosurgery Research Institute (Approval No. 202104007).

Author contributions

FM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LW: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JW: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YD: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. WD: Writing – review & editing. YL: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. QG: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. WX: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. XG: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. PD: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LG: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. RJ: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was primarily supported by the Capital First Health Brain Special Program (CFH-brain) (Grant No. 2024-2-2051). Additional funding was obtained from the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. L223028) and the Beijing Top Climbing Project (Grant No. DFL20240506). Further support was provided by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (Grant No. W2024SNKT21) and the National Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No. 2023ZD0503805) under the Ministry of Science and Technology.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ICH, Intracerebral hemorrhage; TCD, Transcranial Doppler; MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; SWI, Susceptibility-weighted imaging; T2WI, T2-weighted imaging; BBB, Blood–brain barrier; LIPUS, Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound; ROI, Region of interest; SEM, Standard error of the mean; PHE, Perihematomal edema; IgG, Immunoglobulin G; MI, Mechanical index; PRF, Pulse repetition frequency; I_SPTA, Spatial-peak temporal-average intensity; tPA, Tissue plasminogen activator; rtPA, Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator.

Footnotes

References

1.

Gross BA Jankowitz BT Friedlander RM . Cerebral intraparenchymal hemorrhage: a review. JAMA. (2019) 321:1295–303. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.2413,

2.

Krishnamurthi RV Ikeda T Feigin VL . Global, regional and country-specific burden of Ischaemic stroke, intracerebral Haemorrhage and subarachnoid Haemorrhage: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Neuroepidemiology. (2020) 54:171–9. doi: 10.1159/000506396,

3.

Qureshi AI Mendelow AD Hanley DF . Intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet. (2009) 373:1632–44. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60371-8,

4.

van Asch CJ Luitse MJ Rinkel GJ van der Tweel I Algra A Klijn CJ . Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral Haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. (2010) 9:167–76. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(09)70340-0,

5.

Fogelholm R Murros K Rissanen A Avikainen S . Long term survival after primary intracerebral haemorrhage: a retrospective population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2005) 76:1534–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.055145,

6.

Pinho J Costa AS Araújo JM Amorim JM Ferreira C . Intracerebral hemorrhage outcome: a comprehensive update. J Neurol Sci. (2019) 398:54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2019.01.013,

7.

Magid-Bernstein J Girard R Polster S Srinath A Romanos S Awad IA et al . Cerebral hemorrhage: pathophysiology, treatment, and future directions. Circ Res. (2022) 130:1204–29. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.121.319949,

8.

Chang GY . Hematoma growth is a determinant of mortality and poor outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. (2007) 68:471–2. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256290.15120.37,

9.

Li Z Khan S Liu Y Wei R Yong VW Xue M . Therapeutic strategies for intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:1032343. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1032343,

10.

Mendelow AD Gregson BA Fernandes HM Murray GD Teasdale GM Hope DT et al . Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral haematomas in the international surgical trial in intracerebral Haemorrhage (Stich): a randomised trial. Lancet. (2005) 365:387–97. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)17826-x

11.

Hanley DF Thompson RE Muschelli J Rosenblum M McBee N Lane K et al . Safety and efficacy of minimally invasive surgery plus Alteplase in intracerebral Haemorrhage evacuation (Mistie): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. (2016) 15:1228–37. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(16)30234-4,

12.

Naff N Williams MA Keyl PM Tuhrim S Bullock MR Mayer SA et al . Low-dose recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator enhances clot resolution in brain hemorrhage: the intraventricular hemorrhage thrombolysis trial. Stroke. (2011) 42:3009–16. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.110.610949,

13.

Hanley DF Thompson RE Rosenblum M Yenokyan G Lane K McBee N et al . Efficacy and safety of minimally invasive surgery with thrombolysis in intracerebral Haemorrhage evacuation (Mistie iii): a randomised, controlled, open-label, blinded endpoint phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2019) 393:1021–32. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30195-3,

14.

Pradilla G Ratcliff JJ Hall AJ Saville BR Allen JW Paulon G et al . Trial of early minimally invasive removal of intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. (2024) 390:1277–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2308440,

15.

Kaloss AM Arnold LN Soliman E Langman M Groot N Vlaisavljevich E et al . Noninvasive low-intensity focused ultrasound mediates tissue protection following ischemic stroke. BME Front. (2022) 2022:9864910. doi: 10.34133/2022/9864910,

16.

Sung CY Chiang PK Tsai CW Yang FY . Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound enhances neurotrophic factors and alleviates neuroinflammation in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Cereb Cortex. (2021) 32:176–85. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhab201,

17.

Chen SF Su WS Wu CH Lan TH Yang FY . Transcranial ultrasound stimulation improves long-term functional outcomes and protects against brain damage in traumatic brain injury. Mol Neurobiol. (2018) 55:7079–89. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-0897-z,

18.

Chernysh IN Everbach CE Purohit PK Weisel JW . Molecular mechanisms of the effect of ultrasound on the fibrinolysis of clots. J Thromb Haemost. (2015) 13:601–9. doi: 10.1111/jth.12857,

19.

Polat BE Hart D Langer R Blankschtein D . Ultrasound-mediated transdermal drug delivery: mechanisms, scope, and emerging trends. J Control Release. (2011) 152:330–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.01.006,

20.

Alexandrov AV Demchuk AM Felberg RA Christou I Barber PA Burgin WS et al . High rate of complete recanalization and dramatic clinical recovery during Tpa infusion when continuously monitored with 2-Mhz transcranial Doppler monitoring. Stroke. (2000) 31:610–4. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.610,

21.

Hua Y Schallert T Keep RF Wu J Hoff JT Xi G . Behavioral tests after intracerebral hemorrhage in the rat. Stroke. (2002) 33:2478–84. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000032302.91894.0f,

22.

Masomi-Bornwasser J Fabrig O Krenzlin H König J Tanyildizi Y Kempski O et al . Systematic analysis of combined thrombolysis using ultrasound and different fibrinolytic drugs in an in vitro clot model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Ultrasound Med Biol. (2021) 47:1334–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2021.01.005

23.

Masomi-Bornwasser J Heimann A Schneider C Klodt T Elmehdawi H Kronfeld A et al . Intrahematomal ultrasound enhances Rtpa-fibrinolysis in a porcine model of intracerebral hemorrhage. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:563. doi: 10.3390/jcm10040563,

24.

Su WS Wu CH Song WS Chen SF Yang FY . Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound ameliorates glia-mediated inflammation and neuronal damage in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage conditions. J Transl Med. (2023) 21:565. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-04377-z,

25.

Murthy SB Moradiya Y Dawson J Lees KR Hanley DF Ziai WC . Perihematomal edema and functional outcomes in intracerebral hemorrhage: influence of hematoma volume and location. Stroke. (2015) 46:3088–92. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.115.010054,

26.

Wilkinson DA Keep RF Hua Y Xi G . Hematoma clearance as a therapeutic target in intracerebral hemorrhage: from macro to Micro. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2018) 38:741–5. doi: 10.1177/0271678x17753590,

27.

Auer LM Deinsberger W Niederkorn K Gell G Kleinert R Schneider G et al . Endoscopic surgery versus medical treatment for spontaneous intracerebral hematoma: a randomized study. J Neurosurg. (1989) 70:530–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.4.0530,

28.

Ziai WC . Hematology and inflammatory signaling of intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. (2013) 44:S74–8. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.111.000662,

29.

Urday S Kimberly WT Beslow LA Vortmeyer AO Selim MH Rosand J et al . Targeting secondary injury in intracerebral haemorrhage--perihaematomal oedema. Nat Rev Neurol. (2015) 11:111–22. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.264,

30.

Wu H Zhang Z Li Y Zhao R Li H Song Y et al . Time course of upregulation of inflammatory mediators in the hemorrhagic brain in rats: correlation with brain edema. Neurochem Int. (2010) 57:248–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.06.002,

31.

Ironside N Chen CJ Ding D Mayer SA Connolly ES Jr . Perihematomal edema after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. (2019) 50:1626–33. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.119.024965,

32.

Chen Y Chen S Chang J Wei J Feng M Wang R . Perihematomal edema after intracerebral hemorrhage: an update on pathogenesis, risk factors, and therapeutic advances. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:740632. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.740632,

33.

Deng LD Qi L Suo Q Wu SJ Mamtilahun M Shi RB et al . Transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation reduces Vasogenic edema after middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Neural Regen Res. (2022) 17:2058–63. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.335158,

34.

Lee TH Yeh JC Tsai CH Yang JT Lou SL Seak CJ et al . Improved thrombolytic effect with focused ultrasound and neuroprotective agent against acute carotid artery thrombosis in rat. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:1638. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01769-2,

35.

Francis CW Blinc A Lee S Cox C . Ultrasound accelerates transport of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator into clots. Ultrasound Med Biol. (1995) 21:419–24. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(94)00119-x,

36.

Apfel RE . Acoustic cavitation: a possible consequence of biomedical uses of ultrasound. Br J Cancer Suppl. (1982) 5:140–6.

37.

Shaw GJ Bavani N Dhamija A Lindsell CJ . Effect of mild hypothermia on the thrombolytic efficacy of 120 Khz ultrasound enhanced thrombolysis in an in-vitro human clot model. Thromb Res. (2006) 117:603–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.05.005,

38.

Purkayastha S Sorond F . Transcranial Doppler ultrasound: technique and application. Semin Neurol. (2012) 32:411–20. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331812,

39.

Julian FJ Goldman DE . The effects of mechanical stimulation on some electrical properties of axons. J Gen Physiol. (1962) 46:297–313. doi: 10.1085/jgp.46.2.297,

40.

Karshafian R Bevan PD Williams R Samac S Burns PN . Sonoporation by ultrasound-activated microbubble contrast agents: effect of acoustic exposure parameters on cell membrane permeability and cell viability. Ultrasound Med Biol. (2009) 35:847–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.10.013,

41.

Yang Q Nanayakkara GK Drummer C Sun Y Johnson C Cueto R et al . Low-intensity ultrasound-induced anti-inflammatory effects are mediated by several new mechanisms including gene induction, Immunosuppressor cell promotion, and enhancement of exosome biogenesis and docking. Front Physiol. (2017) 8:818. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00818,

Summary

Keywords

intracerebral hemorrhage, non-invasive pulsed ultrasound, hematoma clearance, perihematomal edema resorption, neurological recovery

Citation

Ma F, Wang L, Wang J, Du Y, Dong W, Li Y, Guan Q, Xing W, Gong X, Dong P, Guo L and Ji R (2026) Non-invasive pulsed ultrasound enhances hematoma clearance and neurological recovery in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Front. Neurol. 17:1698217. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2026.1698217

Received

20 January 2026

Revised

01 January 2026

Accepted

21 January 2026

Published

11 February 2026

Volume

17 - 2026

Edited by

Andrea Zini, IRCCS Institute of Neurological Sciences of Bologna (ISNB), Italy

Reviewed by

Alexander Razumovsky, TCD Global, Inc., United States

Adam Thomas Corkery, The University of Iowa, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Ma, Wang, Wang, Du, Dong, Li, Guan, Xing, Gong, Dong, Guo and Ji.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ruijun Ji, jrjchina@sina.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.