Abstract

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is increasingly being recognized as a potential complication of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), posing challenges in diagnosis and prognosis. We conducted a systematic search of case reports published from 1996 to 2023 in PubMed and Web of Science using the terms “sinus thrombosis, intracranial” and “subarachnoid hemorrhage” and identified 94 cases from 58 articles. Analysis of these cases suggests potential predictors of CVST complicated by SAH, including epilepsy, pregnancy history, abortion history, migraine history, thrombosis in the superior sagittal sinus, and thrombosis involving both the superior sagittal and transverse sinuses. These findings could stimulate further research on the diagnosis and treatment of CVST complicated by SAH.

1 Introduction

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) is a series of cerebrovascular diseases caused by various etiologies and features, including the obstruction of cerebrovenous return and impaired absorption of cerebrospinal fluid. It is a rare and underrecognized kind of stroke that accounts for 0.5–1% of all stroke occurrences, yet the fatality rate can reach 10% (1). As a very serious but common encephalopathy, although the main causes of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) are ruptured aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis could be associated with SAH in a few cases (2).

The frequency of CVST in daily practice is increasing, and some CVST cases have been reported to be complicated by SAH. SAH is becoming widely recognized as a possible complication of CVST. The possible pathophysiological mechanisms are as follows. First, cerebral venous thrombosis induces local inflammation, increases vascular permeability, and allows blood to enter the subarachnoid space. Second, venous parenchymal hemorrhagic infarction is a potential complication in patients with CVST and may rupture into the subarachnoid space in some cases. Finally, dural sinus thrombosis extends to the superficial vein, resulting in local venous hypertension accompanied by dilation of the thin and fragile parietal cortical veins and eventual rupture into the SA space (3).

On the other hand, CVST is characterized by a variety of vague clinical symptoms that coincide with those of other disorders, including SAH. The non-specific symptoms affect the early diagnosis and treatment of CVST.

2 Methods

2.1 Search strategy

We searched for studies collected in PubMed and Web of Science from 1996 to 2023 using the terms “sinus thrombosis,” “intracranial,” and “subarachnoid hemorrhage.” Repeated and inaccessible studies were excluded. We screened case reports and case series reports of CVST complicated by SAH. We excluded emails, studies with only abstracts, reviews, and meta-analyses without case presentations, comments, and letters. The search strategy flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Search strategy flowchart.

2.2 Data collection

We extracted data on each patient characteristic (age, sex, initial symptoms, possible etiology and risk factors, location of the CVST thrombus, and subsequent treatment) and recorded them in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for summary and descriptive analysis. When the information was insufficient or descriptions were unclear, we marked the item as missing in the case information record sheet to be excluded during the statistical process.

3 Results

3.1 Demography

We extracted data from 94 cases from 58 identified articles. The mean age of the 94 patients was 41.0 ± 12.7 (39.5) years, with the youngest being 14 years and the oldest being 83 years. Of this, 45 were male (45/94, 47.9%, mean age 42.6 years), and 49 were female (49/94, 52.1%, mean age 39.2 years). Among the females, 38 patients were under 50 years old (40.4% of all the reviewed cases) of childbearing age.

3.2 Etiology

Of the identified cases, 20 were excluded due to missing risk factors and vague descriptions, leaving 74 cases for etiology statistics. There were 22 young females (22/74, 29.7%) with oral contraceptive and other hormone drug usage etiology (only 4 patients had hormone therapy, but not with enterogastrone), and 12 patients (12/74, 16.2%) had a history of recent pregnancy and abortion. There were 9 patients with a specific embolization status (9/74, 12.2%, including 1 with factor III deficiency, 2 with anticardiolipin antibody syndrome, 1 with activated protein C resistance, 3 with a Factor V Leyden mutation, and 2 with a factor II G20210A mutation). Eight patients (8/74, 10.8%) had a history of migraine, and 7 patients (7/74, 9.46%) had received the influenza vaccine within 1 month before the onset of illness. Increased homocysteine was found in five patients, and five patients suffered from spinal craniocerebral traumatic operations, such as lumbar puncture and craniocerebral trauma. Five patients had a history of thrombotic events, and four patients had a history of autoimmune diseases other than APS (including three cases of Graves’ disease and one case of suspected Behcet’s disease). Four patients had a history of polycythemia. Four patients had gastroenteritis and dehydration. We also counted the single and combined situations of these factors, which are all presented in Supplementary Table S1.

3.3 Symptoms and signs

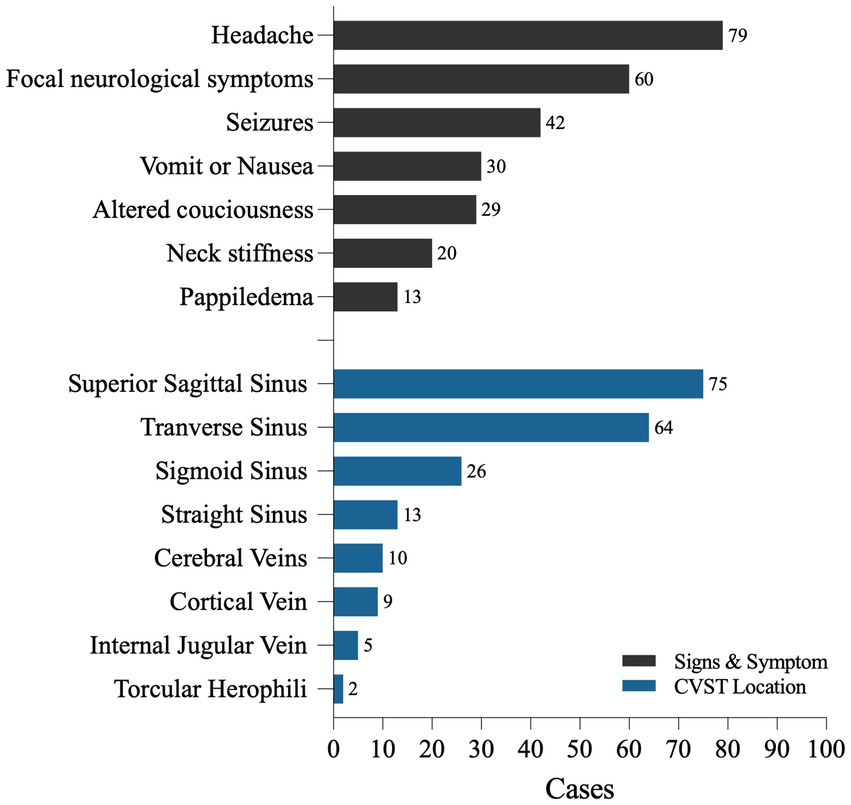

Among the 94 patients, 79 reported symptoms of headache (79/94, 84.0%). Among these, 13 were described as thunderclap or lightning-like headaches, 25 had subacute headaches, and 3 had progressive headaches lasting from 3 days to 1 month. Nausea or vomiting occurred in 30 patients (31.6%), and papilledema was observed in 13 patients during physical examination. A total of 84 patients (89.7%) exhibited signs of intracranial hypertension, as mentioned above. Seizures were the initial symptoms in 42 patients, accounting for 44.7% (among patients describing specific types of seizures, 13 had generalized seizures and 11 had partial seizures). A total of 60 patients (60/94, 63.83%) presented with focal neurological symptoms, including hemiparesis, sensory abnormalities, and non-specific language impairments, which may be closely related to dysfunction of the affected venous system in the brain area. A total of 29 patients (29/94, 30.9%) experienced changes in consciousness and mental status, among whom 12 patients were clearly described as having severe impairment of consciousness (delirium, coma, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) ≤ 9). A total of 11 patients had mild symptoms, such as drowsiness, irritability, and mild confusion, with GCS scores greater than 9. Neck stiffness or rigidity was observed in 20 (21.3%) patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2

The symptoms and CVST locations of 94 CVST cases with SAH.

3.4 CVST location

There were 76 cases (76/94, 80.9%) of thrombosis in the superior sagittal sinus (SSS), 64 cases (64/94, 68.1%) in the transverse sinus (T), 26 cases (26/94, 27.67%) in the sigmoid sinus (SS), and 13 cases (13/94, 13.8%) in the straight sinus (St). We found a few cases of thrombosis located in the inferior sagittal sinus (ISS) and torcular herophili. SSS and T were simultaneously involved in 45 cases (45/94, 45.8%), and there were 57 cases of multiple thromboses involving two or more sites (57/94, 53.2%) (Table 1; Figure 2).

Table 1

| Age | Sex | CVST Location | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 37 | F | SSS + T + SS | de Bruijn et al. (19) |

| 32 | F | T + SS | de Bruijn et al. (19) |

| 54 | F | SSS | Ohta et al. (20) |

| 36 | F | T + SS + CV(c) | Ciccone et al. (21) |

| 60 | M | SSS + T + SS | Ra et al. (22) |

| 58 | F | T + SS | Sztajzel et al. (23) |

| 38 | M | SSS + T + St + CV + IJV + TH | Selim et al. (24) |

| 36 | M | SSS + T + St + IJV + CV | Selim et al. (24) |

| 33 | F | SSS + CV(c) | Widjaja et al. (25) |

| 22 | F | SSS | Widjaja et al. (25) |

| 43 | F | SSS + T + St + CV(c) | Widjaja et al. (25) |

| 27 | F | SSS + T + IJV | Tidahy et al. (26) |

| 14 | M | SSS + St + CV | Adaletli et al. (27) |

| 69 | M | SSS + T | Oppenheim et al. (28) |

| 55 | F | SSS + T | Oppenheim et al. (28) |

| 32 | F | SSS + T | Oppenheim et al. (28) |

| 51 | F | SSS + CV(c) | Oppenheim et al. (28) |

| 41 | F | SSS | Spitzer et al. (10) |

| 42 | M | SSS + T | Spitzer et al. (10) |

| 45 | F | SSS + T + SS + St | Zare and Mirabdolbaghi (29) |

| 39 | M | SSS + T | Kasuga et al. (30) |

| 44 | M | SSS + T | Lin et al. (31) |

| 56 | F | SSS + T | Rice et al. (32) |

| 31 | F | SSS | Senel et al. (33) |

| 40 | M | SSS + T + SS + ISS | Shukla et al. (34) |

| 40 | M | SSS + T | Mathew et al. (35) |

| 33 | F | T + CV + TH | Wang et al. (36) |

| 53 | F | SSS | Jaiser et al. (37) |

| 34 | M | SSS | Lai et al. (38) |

| 43 | F | SSS + T | Tang et al. (39) |

| 37 | F | SSS + T | Tang et al. (39) |

| 46 | F | SSS + T | Tang et al. (39) |

| 48 | M | SSS + T | Tang et al. (39) |

| 30 | M | SSS + T | Tang et al. (39) |

| 23 | M | SSS + T | Tang et al. (39) |

| 56 | M | SSS + T | Benabu et al. (3) |

| 31 | F | SSS | Bittencourt et al. (40) |

| 72 | F | T + SS + St + CV | Lee et al. (41) |

| 39 | F | St + ISS + CV | Lee et al. (41) |

| 38 | F | SSS + T | Hegazi et al. (42) |

| 52 | F | SSS + T + SS + St | Kato et al. (43) |

| 40 | M | SSS + T + SS | Sharma et al. (44) |

| 32 | M | SSS + T | Panda et al. (11) |

| 50 | M | SSS + T + St | Panda et al. (11) |

| 27 | F | SSS + T + St | Panda et al. (11) |

| 33 | M | SSS | Panda et al. (11) |

| 32 | F | SSS | Panda et al. (11) |

| 25 | M | SSS | Panda et al. (11) |

| 38 | M | SSS + T | Panda et al. (11) |

| 39 | M | SSS | Panda et al. (11) |

| 38 | M | SSS + T + SS + St + ISS | Panda et al. (11) |

| 59 | M | SSS + T | Sharma et al. (45) |

| 70 | M | SSS | Field et al. (46) |

| 83 | M | T | Oda et al. (47) |

| 22 | M | SSS + T | Oz et al. (48) |

| 42 | F | T + SS | Saya et al. (49) |

| 36 | M | SSS + T + SS | Saya et al. (49) |

| 48 | M | SSS | Sahin et al. (13) |

| 24 | F | SSS + CV(c) | Froehler (50) |

| 30 | M | T + SS + CV | Kulkarni et al. (51) |

| 22 | F | SSS + T | Mathon et al. (52) |

| 42 | M | SSS + T + SS | Anderson et al. (53) |

| 46 | M | SSS + T + SS | Hassan et al. (54) |

| 35 | M | SSS | Hassan et al. (54) |

| 40 | F | SSS + CV(c) | Bansal et al. (55) |

| 58 | M | SSS | Kathib et al. (56) |

| 45 | M | T | Fu et al. (57) |

| 45 | M | T + SS | Liang et al. (58) |

| 38 | M | SSS | Uniyal et al. (59) |

| 58 | M | SSS + St | Abbas et al. (60) |

| 44 | F | T + SS + IJV | Amer et al. (61) |

| 20 | F | SSS | Han et al. (62) |

| 57 | F | SSS | Sun et al. (63) |

| 32 | M | SSS + T + CV(c) | Mehta et al. (64) |

| 25 | M | SSS + CV(c) | Mehta et al. (64) |

| 62 | M | SSS + CV(c) | Bérezné et al. (65) |

| 54 | F | SSS + CV | D’Agostino et al. (66) |

| 58 | F | T | Gajurel et al. (67) |

| 25 | F | T | Kumar et al. (68) |

| 45 | M | SSS | Syed et al. (69) |

| 22 | F | SSS + T + SS | Wolf et al. (12) |

| 46 | F | SSS + T + SS | Wolf et al. (12) |

| 36 | F | SSS + T | Medeiros et al. (70) |

| 28 | F | SSS + T + SS | Medeiros et al. (70) |

| 49 | F | SSS + T + SS | Medeiros et al. (70) |

| 30 | F | SSS + CV | Medeiros et al. (70) |

| 28 | F | SS + IJV | Medeiros et al. (70) |

| 44 | M | T | Medeiros et al. (70) |

| 40 | F | SSS + T + SS | Medeiros et al. (70) |

| 43 | F | SSS | Medeiros et al. (70) |

| 38 | F | T | Medeiros et al. (70) |

| 32 | F | SSS + T + SS + St + IJV | Medeiros et al. (70) |

| 47 | M | SSS + T | Medeiros et al. (70) |

| 39 | M | SS + T + CV | Sakashita et al. (71) |

CVST locations in 94 CVST cases with SAH.

SSS, superior sagittal sinus; T, transverse sinus; St, straight sinus; SS, sigmoid sinus; ISS, Inferior sagital sinus; IJV, Internal jugular vein; CV, Cerebral veins; CV, Cerebral veins including Galen, Labbe, and Trolard; CV(c), Cortical Vein; TH, torcular herophili.

3.5 Treatment

Seventy-four patients underwent anticoagulant therapy. During follow-up, 56 patients achieved complete recovery, 8 showed partial recovery, and 6 were discharged with partial remission but were lost to follow-up. One patient exhibited no improvement, while three experienced rapid deterioration and died. Additionally, one patient had a short-term recurrence of cerebral venous thrombosis. Moreover, among the patients who received subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin followed by oral anticoagulation, all achieved complete remission, except for one who was lost to follow-up (Supplementary Table S2).

4 Discussion

There are a few reports of concurrent subarachnoid hemorrhage in CVST. A study of baseline characteristics of patients with CVST in the National Readmissions Database (NRD) found that the average age of patients was 46.8 years, with a predominance of females (65%) (4). Our retrospective analysis yielded similar results regarding the average age of the patients compared with the above research. However, among the patients with CVST and concurrent SAH included in our review, the sex distribution was close to 1:1. Reproductive-age females did not constitute the majority of patients in our review of concurrent SAH cases, although they are considered the main population at risk for CVST (5). Lin et al. (6) found that compared to patients of other ages and genders, reproductive-age females with CVST had better outcomes and were less likely to experience severe complications, including intracranial hemorrhage; the mechanism behind this phenomenon remains unclear.

Our review of CVST combined with SAH found a relatively higher proportion of patients with recent pregnancy history than the susceptibility factors described by Ferro et al. (33.3% vs. 21%) (7). This may be attributed to hormonal changes during pregnancy, especially the elevation of estrogen levels, which can affect the stability of blood vessel walls, making them more fragile and prone to damage. Increased blood volume and cardiac output during pregnancy may subject the vascular system to additional stress. These changes may exacerbate the pathological condition of cerebral veins already affected by thrombosis. Other etiologies or risk factors did not show any additional noteworthy characteristics.

Thunderclap headache, often known as lightning strike headache, is the primary symptom of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (8). However, in the cases of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) accompanied by SAH that we examined, less than 20% of the patients had this distinctive headache. This result implies that CVST-induced SAH rarely results in thunderclap headaches. This could be due to the different causes of SAH; ruptured aneurysms account for approximately 90% of SAH cases (8), and sudden and intense bleeding from aneurysmal rupture frequently displays as thunderclap headaches. CVST, a less prevalent cause of SAH, is characterized by a progressive pathophysiological mechanism that results in bleeding. In cases where CVST causes SAH, rupture of the venous sinuses and superficial veins directly into the subarachnoid space often relieves venous congestion and surrounding edema, resulting in diffuse bleeding in the subarachnoid space. Consequently, local intracranial pressure may be alleviated, leading to milder headaches than those caused by ruptured aneurysms. Among all patients, 16 presented with isolated headaches as the initial symptom, without focal neurological symptoms, seizures, or impaired mental status. The initial headaches in these patients are often confused with migraines, posing a challenge for clinical diagnosis and making them prone to misdiagnosis.

Lindgren et al. (9) conducted a large-scale study on the association between CVST and seizures, finding that 34% of 1,281 patients experienced seizures within 1 week after cerebral venous thrombosis formation. In contrast, we noticed that 44.7% of patients with CVST combined with SAH experienced seizures at onset, which represents an increased proportion compared to the aforementioned studies. Based on this comparison, we propose that seizures may be related to CVST complicated by SAH, especially when SAH occurs in the cerebral convexity region, which may directly stimulate the cerebral cortex and trigger seizures. Spontaneous cerebral convex subarachnoid hemorrhage (cSAH) is a rare and distinct subtype of subarachnoid hemorrhage and is an important subtype of non-aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (2). The characteristic feature of this condition is the presence of bleeding limited to one or more sulci of the cerebral convexity, without involving the adjacent brain parenchyma, longitudinal fissures, basal cisterns, or ventricles. When SAH is caused by cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, cSAH is the most common presentation (10). In a study by Panda et al. (11), evidence of concurrent SAH was found in 10 of 233 patients with CVST, all of whom had cSAH. This suggests that the presence of cSAH with bleeding not involving the basal cisterns implies that bleeding is induced by CVST. Our analysis also revealed that 88% of patients with seizures had concurrent cSAH, possibly due to the direct stimulation of the cerebral cortex by cSAH bleeding. Conversely, among the eight patients with SAH limited to the perimesencephalic cisterns and ventricles, only one patient experienced seizures, confirming the association between seizures in patients with CVST and cSAH.

The precise etiology of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) remains unclear. The most plausible explanation lies in the anatomical characteristics of the bridging superficial veins. These veins traverse the subarachnoid space before draining into the dural sinuses and are characterized by thin walls, absence of muscular fibers, and lack of valves. This unique structure grants the cerebral venous system significant capacitance while rendering it susceptible to blood flow reversal during thrombosis (12). Under conditions of venous hypertension, such fragile vessels are prone to rupture, leading to blood extravasation into the subarachnoid space (12). Furthermore, cortical vein thrombosis may occur as a result of retrograde propagation of dural sinus thrombosis (13). Another potential mechanism may involve an inflammatory response induced by CVST, which could increase vascular permeability and allow blood to leak into the subarachnoid space. Additionally, hemorrhagic venous infarction might lead to secondary rupture into the subarachnoid spaces, although this scenario remains infrequently documented in the literature (13).

Multiple studies have shown that the superior sagittal sinus (SSS) is the most common site of CVST, followed by the transverse sinus (TS) and sigmoid sinus (5, 7, 14). SSS accounts for 62–80% of cases, while TS is involved in 38–86% of cases (14). Thrombus formation affects multiple venous sinuses in approximately 75% of cases, with the most common combination being SSS + TS, affecting approximately 30% of patients with CVST simultaneously (14). In reviewing the thrombus sites in CVST complicated by SAH, SSS remains the most prevalent, with the proportion of SSS thrombosis being higher than that reported by Ferro et al. in their study of the CVST population (80.9% vs. 62%). The second most common site is the transverse sinus. However, the sigmoid sinus takes third place, accounting for 27.6%, whereas Ferro et al. reported that the incidence of sigmoid sinus involvement in CVST is less than 10% (7). The proportion of cases involving two or more venous sinuses is lower than that reported by Ferro et al. in their study of the CVST population (53.2% vs. 75%), while involvement of both SSS and TS is 45.8%, which is also the most common combination (5). Therefore, if imaging shows thrombosis in the SSS and both the SSS and TS, vigilance should be given regarding the risk of concomitant SAH.

Systemic anticoagulation serves as the first-line treatment for CVST due to its well-established efficacy and safety profile. Notably, the presence of hemorrhage in CVST does not contraindicate anticoagulant therapy; once imaging confirms CVST, anticoagulation should be initiated regardless of whether intracerebral bleeding is present (15, 16). Regarding anticoagulant selection, standard management of cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) typically begins with parenteral anticoagulation using unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin, followed by long-term oral therapy with vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) (15, 16). In practice, for patients requiring continued anticoagulation after discharge—particularly when regular coagulation monitoring is challenging—dabigatran may be considered as a maintenance option. Among the cases reviewed, eight patients received dabigatran orally for several months post-discharge, all of whom exhibited favorable outcomes. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), including factor Xa inhibitors (e.g., rivaroxaban, edoxaban) and the factor IIa inhibitor dabigatran, are increasingly used off-label for CVT, with studies suggesting comparable efficacy and safety to warfarin (17) and potentially superior recanalization rates versus vitamin K antagonists (18). However, evidence remains limited due to disease rarity, underscoring the need for international multicenter studies to establish DOACs’ role in CVST management.

5 Conclusion

Based on the results of the above case analysis, seizures, obstetric history, migraine history, thrombosis in the superior sagittal sinus, and thrombosis involving both the superior sagittal and transverse sinuses may be potential risk factors for SAH in patients with CVST. Patients with CVST with these characteristics should be vigilant about the risk of developing SAH, and targeted interventions should be implemented to improve patient outcomes. More diverse-sample case–control and cohort studies are needed. This will enable timely diagnosis and intervention to prevent the severe consequences of SAH in patients with CVST with the aforementioned conditions, as well as advise anticoagulant choice and timing.

6 Limitations

As it is a rare disease and its complications, data from fewer than 100 cases were collected. Our study used secondary information, so we could not directly contact the patients, and some missing information in the cases affected the accuracy of the analysis results. Consequently, the information could only be analyzed descriptively.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

XM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. XH: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. DS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants and clinical staff for their support and contributions to this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2026.1718666/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Gharaibeh K Aladamat N Ali A Mierzwa AT Pervez H Jumaa M et al . Predictors of early intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with cerebral sinus venous thrombosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2024) 33:108028. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2024.108028,

2.

Jha S Kulanthaivelu K Raja P Kenchiah R Ramakrishnan S Kulkarni GB et al . Spectrum of intracranial hemorrhages in cerebral venous thrombosis: a pictorial case series and review of pathophysiology and management. Neurologist. (2025) 30:45–51. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0000000000000604,

3.

Unal AY Unal A Goksu E Arslan S . Cerebral venous thrombosis presenting with headache only and misdiagnosed as subarachnoid hemorrhage. World J Emerg Med. (2016) 7:234–6. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2016.03.013,

4.

Coutinho JM Zuurbier SM Aramideh M Stam J . The incidence of cerebral venous thrombosis: a cross-sectional study. Stroke. (2012) 43:3375–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.671453,

5.

Ferro JM de Aguiar Sousa D . Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. (2019) 19:74. doi: 10.1007/s11910-019-0988-x,

6.

Lin L Liu S Wang W He XK Romli MH Rajen Durai R . Key prognostic risk factors linked to poor functional outcomes in cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. (2025) 25:52. doi: 10.1186/s12883-025-04059-x,

7.

Ferro JM Canhão P Stam J Bousser MG Barinagarrementeria F ISCVT Investigators . Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the international study on cerebral vein and Dural sinus thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke. (2004) 35:664–70. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000117571.76197.26,

8.

Renou P Tourdias T Fleury O Debruxelles S Rouanet F Sibon I . Atraumatic nonaneurysmal sulcal subarachnoid hemorrhages: a diagnostic workup based on a case series. Cerebrovasc Dis (Basel, Switzerland). (2012) 34:147–52. doi: 10.1159/000339685,

9.

Lindgren E Silvis SM Hiltunen S Heldner MR Serrano F de Scisco M et al . Acute symptomatic seizures in cerebral venous thrombosis. Neurology. (2020) 95:e1706–15. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010577,

10.

Spitzer C Mull M Rohde V Kosinski CM . Non-traumatic cortical subarachnoid haemorrhage: diagnostic work-up and aetiological background. Neuroradiology. (2005) 47:525–31. doi: 10.1007/s00234-005-1384-6,

11.

Panda S Prashantha DK Shankar SR Nagaraja D . Localized convexity subarachnoid haemorrhage--a sign of early cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Eur J Neurol. (2010) 17:1249–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03001.x,

12.

Medeiros FC Moraes AC Bicalho ALR Pinto TVL Dahy FE . Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis presenting with subarachnoid hemorrhage: a series of 11 cases. Acta Neurol Belg. (2023) 123:911–6. doi: 10.1007/s13760-022-02081-1,

13.

Sahin N Solak A Genc B Bilgic N . Cerebral venous thrombosis as a rare cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage: case report and literature review. Clin Imaging. (2014) 38:373–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2014.03.005,

14.

Rosa S Fragata I Aguiar de Sousa D . Update on management of cerebral venous thrombosis. Curr Opin Neurol. (2025) 38:18–28. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000001329,

15.

Ferro JM Bousser MG Canhão P Coutinho JM Crassard I Dentali F et al . European stroke organization guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis - endorsed by the European academy of neurology. Eur J Neurol. (2017) 24:1203–13. doi: 10.1111/ene.13381,

16.

Weimar C Beyer-Westendorf J Bohmann FO Hahn G Halimeh S Holzhauer S et al . New recommendations on cerebral venous and dural sinus thrombosis from the German consensus-based (S2k) guideline. Neurol Res Pract. (2024) 6:23. doi: 10.1186/s42466-024-00320-9,

17.

Yaghi S Shu L Bakradze E Salehi Omran S Giles JA Amar JY et al . Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in the treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis (ACTION-CVT): a multicenter international study. Stroke. (2022) 53:728–38. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.037541,

18.

Nepal G Kharel S Bhagat R Ka Shing Y Ariel Coghlan M Poudyal P et al . Safety and efficacy of direct oral anticoagulants in cerebral venous thrombosis: a meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Scand. (2022) 145:10–23. doi: 10.1111/ane.13506,

19.

de Bruijn SF Stam J Kappelle LJ . Thunderclap headache as first symptom of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. CVST study group. Lancet (London, England). (1996) 348:1623–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07294-7,

20.

Ohta H Kinoshita Y Hashimoto M Yamada H Urasaki E Yokota A . Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis presenting with subarachnoid hemorrhage in a patient with aplastic anemia [in Japanese]. No To Shinkei. (1998) 50:739–43.

21.

Ciccone A Citterio A Santilli I Sterzi R . Subarachnoid haemorrhage treated with anticoagulants. Lancet (London, England). (2000) 356:1818. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03236-0,

22.

Ra CS Lui CC Liang CL Chen HJ Kuo YL Chen WF . Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis induced by thyrotoxicosis. Case report. J Neurosurg. (2001) 94:130–2. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.94.1.0130

23.

Sztajzel R Coeytaux A Dehdashti AR Delavelle J Sinnreich M . Subarachnoid hemorrhage: a rare presentation of cerebral venous thrombosis. Headache. (2001) 41:889–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.01161.x

24.

Selim M Fink J Linfante I Kumar S Schlaug G Caplan LR . Diagnosis of cerebral venous thrombosis with echo-planar T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol. (2002) 59:1021–6. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.6.1021

25.

Widjaja E Romanowski CA Sinanan AR Hodgson TJ Griffiths PD . Thunderclap headache: presentation of intracranial sinus thrombosis?Clin Radiol. (2003) 58:648–52. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(03)00174-0,

26.

Tidahy E Derex L Belo M Dardel P Robert R Honnorat J et al . Thrombophlébite cérébrale révélée par une hémorragie sous-arachnoïdienne [Cerebral venous thrombosis presenting as subarachnoid hemorrhage]. Rev Neurol (Paris). (2004) 160:459–61. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(04)70930-3

27.

Adaletli I Sirikci A Kara B Kurugoglu S Ozer H Bayram M . Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis presenting with excessive subarachnoid hemorrhage in a 14-year-old boy. Emerg Radiol. (2005) 12:57–9. doi: 10.1007/s10140-005-0438-8,

28.

Oppenheim C Domigo V Gauvrit JY Lamy C Mackowiak-Cordoliani MA Pruvo JP et al . Subarachnoid hemorrhage as the initial presentation of dural sinus thrombosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. (2005) 26:614–7.

29.

Zare M Mirabdolbaghi P . Cerebral venous thrombosis presented as subarachnoid hemorrhage and treated with anticoagulants. J Res Med Sci. (2005) 10:251–4.

30.

Kasuga K Naruse S Umeda M Tanaka M Fujita N . Rinsho shinkeigaku = clinical neurology. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. (2006) 46:270–3.

31.

Lin JH Kwan SY Wu D . Cerebral venous thrombosis initially presenting with acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Chinese Med Assoc. (2006) 69:282–5. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70258-8,

32.

Rice H Tang YM . Acute subarachnoid haemorrhage: a rare presentation of cerebral dural sinus thrombosis. Australas Radiol. (2006) 50:241–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2006.01569.x,

33.

Alparslan S Adnan D Hilmi AK Enis K . Localized spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage as first manifestation of cerebral venous thrombosis. Neurosurg Q. (2006) 16:117–20. doi: 10.1097/01.wnq.0000214015.65162.e1

34.

Shukla R Vinod P Prakash S Phadke RV Gupta RK . Subarachnoid haemorrhage as a presentation of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. J Assoc Physicians India. (2006) 54:42–4.

35.

Mathew T Sarma GR Kamath V Roy AK . Subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage and intracerebral parenchymal hemorrhage secondary to cerebral sinovenous thrombosis: a rare combination. Neurol India. (2007) 55:438–9. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.37110,

36.

Wang YF Fuh JL Lirng JF Chang FC Wang SJ . Spontaneous intracranial hypotension with isolated cortical vein thrombosis and subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cephalalgia. (2007) 27:1413–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01437.x,

37.

Jaiser SR Raman A Maddison P . Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis as a rare cause of thunderclap headache and nonaneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neurol. (2008) 255:448–9. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0683-3,

38.

Lai NK Hui JW Wong GK Yu SC Sun DT Poon WS . Cerebral venous thrombosis presenting as subarachnoid haemorrhage. Hong Kong Med J. (2008) 14:499–500.

39.

Tang PH Chai J Chan YH Chng SM Lim CC . Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis: subtle signs on neuroimaging. Ann Acad Med Singap. (2008) 37:397–401.

40.

Bittencourt LK Palma-Filho F Domingues RC Gasparetto EL . Subarachnoid hemorrhage in isolated cortical vein thrombosis: are presentation of an unusual condition. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. (2009) 67:1106–8. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2009000600029,

41.

Lee J Koh EM Chung CS Hong SC Kim YB Chung PW et al . Underlying venous pathology causing perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage. Can J Neurol Sci. (2009) 36:638–42. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100008167,

42.

Hegazi MO Ahmed S Sakr MG Hassanien OA . Anticoagulation for cerebral venous thrombosis with subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case report. Med Princ Pract. (2010) 19:73–5. doi: 10.1159/000252839

43.

Kato Y Takeda H Furuya D Nagoya H Deguchi I Fukuoka T et al . Subarachnoid hemorrhage as the initial presentation of cerebral venous thrombosis. Internal Med (Tokyo, Japan). (2010) 49:467–70. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.2789,

44.

Sharma B Satija V Dubey P Panagariya A . Subarachnoid hemorrhage with transient ischemic attack: another masquerader in cerebral venous thrombosis. Indian J Med Sci. (2010) 64:85–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5359.94405

45.

Sharma S Sharma N Yeolekar ME . Acute subarachnoid hemorrhage as initial presentation of dural sinus thrombosis. J Neurosci Rural Pract. (2010) 1:23–5. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.63097,

46.

Field DK Kleinig TJ . Aura attacks from acute convexity subarachnoid haemorrhage not due to cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Cephalalgia. (2011) 31:368–71. doi: 10.1177/0333102410384885,

47.

Oda S Shimoda M Hoshikawa K Osada T Yoshiyama M Matsumae M . Cortical subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by cerebral venous thrombosis. Neurol Med Chir. (2011) 51:30–6. doi: 10.2176/nmc.51.30,

48.

Oz O Akgun H Yücel M Battal B Ipekdal HI Ulaş UH et al . Cerebral venous thrombosis presenting with subarachnoid hemorrhage after spinal anesthesia. Acta Neurol Belg. (2011) 111:237–40.

49.

Sayadnasiri M Taheraghdam AA Talebi M . Cerebral venous thrombosis presenting as subarachnoid hemorrhage: report of two cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2012) 114:1099–101. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.02.024,

50.

Froehler MT . Successful treatment of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with the solitaire FR thrombectomy device. J Neurointerv Surg. (2013) 5:e45. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2012-010517,

51.

Kulkarni GB Mustare V Abbas MM . Profile of patients with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with cerebellar involvement. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2014) 23:1106–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.09.022,

52.

Mathon B Ducros A Bresson D Herbrecht A Mirone G Houdart E et al . Subarachnoid and intra-cerebral hemorrhage in young adults: rare and underdiagnosed. Rev Neurol. (2014) 170:110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2013.07.032,

53.

Anderson B Sabat S Agarwal A Thamburaj K . Diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Pol J Radiol. (2015) 80:286–9. doi: 10.12659/PJR.894122,

54.

Hassan A Ahmad B Ahmed Z Al-Quliti KW . Acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. An unusual clinical presentation of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Neurosciences (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). (2015) 20:61–4.

55.

Bansal H Chaudhary A Mahajan A Paul B . Acute subdural hematoma secondary to cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: case report and review of literature. Asian J Neurosurg. (2016) 11:177. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.175632,

56.

Khatib KI Baviskar AS . Treatment of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with subdural hematoma and subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Emerg Trauma Shock. (2016) 9:155–6. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.193386,

57.

Fu FW Rao J Zheng YY Song L Chen W Zhou QH et al . Perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by transverse sinus thrombosis: a case report and review of literature. Medicine. (2017) 96:e7374. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007374,

58.

Liang J Chen H Li Z He S Luo B Tang S et al . Cortical vein thrombosis in adult patients of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis correlates with poor outcome and brain lesions: a retrospective study. BMC Neurol. (2017) 17:219. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0995-y,

59.

Uniyal R Kumar N Malhotra HS Garg RK . Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis presenting as subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurol Belg. (2017) 117:313–4. doi: 10.1007/s13760-016-0706-2

60.

Abbas A Sawlani V Hosseini AA . Subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Clin Case Rep. (2018) 6:768–9. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.1335,

61.

Amer RR Bakhsh EA . Nonaneurysmal Perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage as an atypical initial presentation of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a case report. Am J Case Rep. (2018) 19:472–7. doi: 10.12659/ajcr.908439,

62.

Han KH Won YD Na MK Han MH Ryu JI Kim JM et al . Postpartum superior sagittal sinus thrombosis: a case report. Korean J Neurotrauma. (2018) 14:146–9. doi: 10.13004/kjnt.2018.14.2.146,

63.

Sun J He Z Nan G . Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis presenting with multifocal intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case report. Medicine. (2018) 97:e13476. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013476,

64.

Mehta DG Swanson JW . Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis mimicking probable paroxysmal Hemicrania: a case report. Headache. (2020) 60:992–3. doi: 10.1111/head.13781,

65.

D'Agostino V Caranci F Negro A Piscitelli V Tuccillo B Fasano F et al . A rare case of cerebral venous thrombosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation temporally associated to the COVID-19 vaccine administration. J Pers Med. (2021) 11:285. doi: 10.3390/jpm11040285,

66.

Gajurel BP Shrestha A Gautam N Rajbhandari R Ojha R Karn R . Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with concomitant subdural hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhages involving cerebral convexity and perimesenchephalic regions: a case report. Clin Case Reports. (2021) 9:e04919. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.4919,

67.

Kumar H Ali S Kumar J Anwar MN Singh R . Dural venous sinus thrombosis leading to subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cureus. (2021) 13:e13497. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13497,

68.

Syed K Chaudhary H Donato A . Central venous sinus thrombosis with subarachnoid hemorrhage following an mRNA COVID-19 vaccination: are these reports merely co-incidental?Am J Case Rep. (2021) 22:e933397. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.933397,

69.

Wolf ME Luz B Niehaus L Bhogal P Bäzner H Henkes H . Thrombocytopenia and intracranial venous sinus thrombosis after "COVID-19 vaccine AstraZeneca" exposure. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:1599. doi: 10.3390/jcm10081599,

70.

Sakashita K Miyata K Saito R Sato R Kim S Mikuni N . A case of Perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis due to stenosis of the junction of the vein of Galen and Rectus sinus. Case Rep Neurol. (2022) 14:307–13. doi: 10.1159/000525506,

71.

Leavell Y Khalid M Tuhrim S Dhamoon MS . Baseline characteristics and readmissions after cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in a nationally representative database. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2018) 46:249–56. doi: 10.1159/000495420

Summary

Keywords

cerebral venous sinus, hemorrhage, review, subarachnoid, thrombosis

Citation

Ma X, He X and Sha D (2026) Subarachnoid hemorrhage complicated by cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a quantitative systematic review of cases. Front. Neurol. 17:1718666. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2026.1718666

Received

24 October 2025

Revised

20 December 2025

Accepted

12 January 2026

Published

02 February 2026

Volume

17 - 2026

Edited by

Shreyas Kuddannaya, University of Miami, United States

Reviewed by

Christian Scheiwe, University Hospital Freiburg, Germany

Steven Tandean, University of North Sumatra, Indonesia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Ma, He and Sha.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dujuan Sha, tbwen0912@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.