Abstract

Objective:

To develop and internally validate a machine learning (ML) model that identifies older outpatients with MCI using routine electronic health record (EHR) data.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study of community outpatients aged ≥60 years in Zhejiang, China. Structured EHR predictors included demographics, comorbidities/medications, lifestyle, and visit patterns. The outcome was adjudicated MCI based on cognitive screening (MoCA plus supplemental tests). Supervised ML classifiers were compared using 10-fold cross-validation and an independent held-out test set; class imbalance was addressed with SMOTE. Performance was assessed by the area under the ROC curve (AUC) and by sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), accuracy, and F1 score.

Results:

The test set included ~640 patients (≈20% MCI). Gradient Boosting performed best: cross-validation mean AUC 0.855 (SD 0.031) and accuracy 0.862 (SD 0.013); test AUC 0.850, accuracy 0.833, and F1 0.402. At the default threshold, sensitivity was 0.286 and specificity 0.967 (PPV 0.679; NPV 0.847). Prioritizing sensitivity (~0.82) lowered specificity (~0.64). At a high-sensitivity threshold of 0.159, the model achieved a sensitivity of 0.802 with a specificity of 0.751 (PPV 0.441; NPV 0.939). Important predictors included older age, female sex, lower education, smaller family size, and higher depression scores.

Conclusion:

An ML model using routine outpatient EHR can discriminate MCI in older adults (AUC ≈ 0.85), supporting potential for automated, low-cost screening in primary care. Using the predicted probabilities generated in this analysis, we assessed calibration and conducted a decision-curve analysis. While the model shows good discrimination and calibration, external validation is still required to confirm clinical utility and refine operating thresholds.

Introduction

Population aging has increased the public health burden of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Recent reviews estimate a global MCI prevalence of about 23.7% (95% CI 18.6–29.6) in older adults (1). In China, a large meta-analysis of 393,525 adults aged ≥60 years reported a prevalence of 19.6% (2). Primary care settings face practical barriers—limited consultation time, workflow constraints, and communication challenges—that lead to underdiagnosis of cognitive impairment (3–5). Consequently, leveraging low-cost, routinely collected outpatient EHR data to identify individuals at risk for MCI is an attractive and scalable strategy.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) offer feasible tools for this task. Recent work shows that ML models using demographics, chronic disease burden, lifestyle, care-seeking behaviors, and basic cognitive/functional measures can achieve useful discrimination for Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders (ADRD) or MCI from EHR data (6). Other studies demonstrate that, even without imaging, Gradient-Boosting models like XGBoost can predict 3-year conversion risk among cognitively healthy older adults using non-imaging features (7). However, important evidence gaps remain: external validation and context-specific thresholding in community populations are limited, and beyond discrimination, reporting of calibration and clinical utility (e.g., decision-curve analysis) is often insufficient.

To address these issues, we developed and internally evaluated an MCI screening model based on community outpatient data, reporting transparent methods aligned with the TRIPOD+AI guidance (8) and framing model evaluation with contemporary BMJ guidance on prediction modeling and clinical utility (9, 10). The model can produce individual predicted probabilities; In this manuscript, we report discrimination (ROC–AUC) and operating characteristics at prespecified thresholds (sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV), in addition to discrimination (ROC–AUC) and classification metrics, we also present calibration plots and decision-curve analysis to assess clinical utility. External validation remains a future step. Thus, this internal analysis should be viewed as an exploratory first step rather than definitive evidence of clinical utility. We outline these future plans, including sample-size considerations for validation and model updating, in the Discussion.

Methods

Study design and reporting

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional analysis using de-identified records from community outpatient clinics. The study protocol received institutional ethics approval. We followed the STROBE guideline for observational studies (11). For model development and internal validation, we adhered to TRIPOD+AI standards (8). We also assessed risk of bias and applicability using PROBAST (12). The number of participants and outcome events (see Results) was considered adequate relative to the number of predictors, and formal sample-size calculations for external validation and model updating will follow the Riley et al. framework. A checklist mapping each TRIPOD+AI, STROBE, and PROBAST item to this manuscript or its Supplement is provided in the Supplementary material (12).

Data source, participants, and outcome

Data were extracted from community health service centers in Zhejiang Province, China, including adults aged ≥60 years with at least one outpatient encounter in the past year. Inclusion required age ≥60 years, ≥1 outpatient visit in the previous 12 months, and sufficient data to ascertain cognitive status. We excluded individuals with established dementia or moderate–severe cognitive impairment, irrecoverable missingness in key variables, or conditions invalidating cognitive assessment (e.g., acute severe illness). The primary outcome was mild cognitive impairment (MCI), adjudicated according to the 2018 Chinese guideline (subjective cognitive complaint/corroboration, objective impairment in ≥1 domain, preserved basic activities of daily living, and not meeting dementia criteria) (13).

Predictors and preprocessing

Candidate predictors were drawn from structured EHR fields: demographics (age, sex, education), social context (living alone, social participation), chronic conditions and medications (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, depressive symptoms), lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol, physical activity, sleep), and care-seeking behaviors (visit frequency, department specialties). Continuous variables were screened for outliers and standardized; categorical variables were harmonized with consistent coding. Missing data were imputed by multiple imputation with chained equations (MICE) (14). We repeated model fitting in each imputed dataset and pooled the results. Since MCI was the minority class, we managed class imbalance in the training data using synthetic minority oversampling (SMOTE) and/or class weighting, while leaving the held-out test set unchanged. The choice of sampling strategy and evaluation metrics was informed by a recent review on imbalanced medical datasets (15).

Data split and model development

We split the data at the participant level into a training set (80%) and an independent held-out test set (20%), ensuring no individual appeared in both. We evaluated 10 supervised learning algorithms: regularized logistic regression, support vector machine, k-nearest neighbors, naïve Bayes, decision tree, random forest, Gradient Boosting (LightGBM), extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and a multilayer perceptron neural network. Most models were implemented with scikit-learn, and boosting models used their native libraries (16). Hyperparameters were tuned via grid or Bayesian search within 10-fold cross-validation. Regularization and early stopping were applied where available to prevent overfitting.

Performance evaluation and operating thresholds

Discrimination was summarized by the area under the receiver-operating-characteristic curve (ROC–AUC). We also reported sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and confusion matrices at two operating points: (i) a default threshold (maximizing Youden’s J statistic) and (ii) a high-sensitivity threshold (to minimize missed cases in community screening). Where sample size allowed, we obtained two-sided 95% confidence intervals for AUC and classification metrics by bootstrap resampling. Calibration (calibration plots, Brier score, calibration intercept and slope) was assessed using the individual predicted probabilities exported from the final model; decision-curve analysis was conducted using standard net-benefit calculations in accordance with contemporary guidance (9, 10).

Implementation and reproducibility

We report 10-fold CV performance as mean ± SD and present AUC, accuracy, and F1 on the held-out test set. For proportions (sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV), two-sided 95% CIs were computed using the Wilson score method. Likelihood ratios were calculated as LR + = Sens/(1–Spec) and LR– = (1–Sens)/Spec, with diagnostic odds ratio DOR = LR+/LR–. All statistics were derived from the held-out test set and its confusion matrix; calibration and decision-curve analyses were performed on the held-out test set using the predicted probabilities exported by the model. Analyses were conducted in Python using pandas/NumPy and scikit-learn for modeling, XGBoost and LightGBM for boosting (16), and shap for model explainability (17). We used fixed random seeds (42) and split data at the participant level to support reproducibility. Key hyperparameters, software/library versions, and script details are provided in the Supplement (“Reproducibility Checklist”) in accordance with TRIPOD+AI transparency expectations (8).

Model explainability

To aid interpretability, we applied SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) to obtain global feature importance and local case-level attributions (17). Representative plots illustrate why an individual is classified as high risk. We also consulted a recent review of explainable AI in healthcare to guide visualization and discussion of caveats (18).

Results

Multiple-model comparison and overall discrimination

We evaluated all 10 candidate algorithms on the held-out test set (Figure 1). Ensemble tree models performed best: Gradient Boosting and XGBoost achieved AUCs around 0.84–0.85, followed by Random Forest. SVM and logistic regression had intermediate performance, and Gaussian naïve Bayes had the lowest AUC. We present these results descriptively in Figure 1, without formal statistical comparisons.

Figure 1

Combined ROC curves comparing ten algorithms.

Cross-validation performance of Gradient Boosting and model selection

In 10-fold cross-validation, the Gradient Boosting model achieved mean accuracy 0.862 (SD 0.013), F1 score 0.371 (SD 0.052), and AUC 0.855 (SD 0.031). The relatively low F1 reflects the small fraction of positive cases, whereas the consistently high AUC and accuracy indicate consistent discrimination. Given its stable performance and high AUC, we selected Gradient Boosting as the primary model for testing (Table 1).

Table 1

| Metric | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.862 ± 0.013 |

| F1 score | 0.371 ± 0.052 |

| AUC | 0.855 ± 0.031 |

10-fold cross-validation performance (mean ± SD).

Held-out test performance and operating characteristics

On the independent test set, the Gradient Boosting model attained AUC 0.850, accuracy 0.833, and F1 score 0.402 (Table 2). At the current operating threshold (0.50), the sensitivity was 0.286, specificity 0.967, PPV 0.679, and NPV 0.847, and the confusion matrix was TP = 36, FP = 17, FN = 90, TN = 497 (Figure 2), with the ROC curve is shown in (Figure 3). This operating point emphasizes high specificity at the cost of low sensitivity, as intended in initial evaluation. At a high-sensitivity threshold of 0.159, the model achieved a sensitivity of 0.802 with a specificity of 0.751 (PPV 0.441; NPV 0.939).

Table 2

| Metric | Test set |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.833 |

| F1 score | 0.402 |

| AUC | 0.850 |

Held-out test-set performance.

Figure 2

Confusion matrix for Gradient Boosting at the current operating threshold (TP = 36, FP = 17, FN = 90, TN = 497).

Figure 3

ROC for Gradient Boosting (AUC ≈ 0.850).

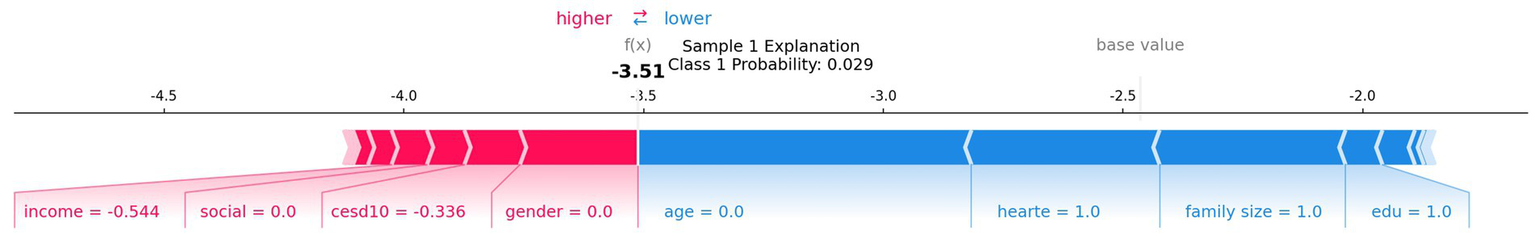

Model interpretability: global importance and individual attribution

SHAP analysis identified family size, age, education, sex, income, and CES-D score as the most important predictors (Figure 4). At the individual level, a representative SHAP force plot (Figure 5) shows how protective factors (e.g., larger family size, higher education) can offset unfavorable factors (e.g., lower income, limited social participation), resulting in a lower predicted risk. We offer only descriptive interpretations and make no causal claims.

Figure 4

Global feature importance by mean absolute SHAP value.

Figure 5

Representative SHAP force plot for one individual. AUC, area under the ROC curve; SHAP, Shapley Additive Explanations.

Additional supplementary results

To conserve space, the 10-fold CV fold-wise variability (boxplots) and SHAP beeswarm/dependence plots (capturing non-linear patterns and interactions) are included in the Supplement (Supplementary Figures S1–S3); the main text cites only their key conclusions.

Discussion

Main findings and significance

Our Gradient Boosting model, trained on routine community outpatient data, achieved good discrimination between MCI and normal cognition (test set AUC ≈ 0.85). At the default threshold, the model had high specificity (~0.97) but low sensitivity (~0.29). Shifting to a high-sensitivity threshold (sensitivity ≈0.82) substantially increased false positives (specificity ≈0.64), reflecting the expected trade-off in screening contexts. These findings indicate that the model effectively identifies high-risk individuals, and that threshold adjustment can balance sensitivity versus specificity for clinical needs.

Our model’s performance is comparable to recent ML studies. For example, Fernández-Blázquez et al. built XGBoost models in older adults and reported AUC ≈ 0.836 (19). Similarly, Hu et al. found AUC ≈ 0.83 for cognitive impairment in a Chinese community cohort (20). These results suggest that readily available outpatient data can yield predictive accuracy on par with more complex approaches. Other studies further support this potential. Yan et al. reported that a simple logistic model in stroke patients achieved AUC 0.8595 (21), and a wearable-sensor study achieved near-perfect discrimination (AUC ≈ 0.94–1.0) by aggregating daily activity, sleep, and heart-rate signals (22). These findings show that both vascular risk profiles and digital physiological signals can provide strong predictive performance and may complement our approach. The top predictors in our model (age, female sex, education, social support, and depression) align with known risk factors (7, 20), supporting the model’s clinical plausibility. Together, our findings demonstrate that AI applied to routine clinical data may offer a practical, low-cost tool for early MCI screening in primary care, while leaving room for future integration of wearable or stroke-specific data.

Beyond discrimination and preset thresholds, we assessed model calibration and decision-curve (net benefit) analysis on the test set using individual predicted probabilities. These internal results suggest good calibration and positive net benefit across a range of thresholds. Nonetheless, external validation is needed to confirm the model’s usefulness. Nonetheless, the reliance on routinely collected EHR data and SHAP-based explanations underscores the feasibility of this approach in primary care settings.

Comparison with previous studies

Few previous studies have focused on MCI prediction using non-imaging clinical data. Richter-Laskowska et al. used EMR features (demographics, labs, comorbidities) to distinguish MCI patients from healthy controls, achieving AUC ≈ 0.75 (23). Hu et al. applied ML to Chinese community data and obtained AUC ≈ 0.83 for cognitive impairment (MCI and dementia), outperforming a conventional screening test (20). In comparison, our model’s AUC (~0.85) was somewhat higher. This may reflect our inclusion of psychosocial factors (e.g., education, living situation) and consistent cross-validation, which can improve generalizability. Fernández-Blázquez et al. also built XGBoost models in older adults (including cognitive test scores) with AUC ≈ 0.836 (24). Yan et al. reported that a parsimonious logistic regression model in high-risk stroke patients achieved AUC 0.8595 (25). Xu et al. showed that aggregating physical activity, sleep, and heart-rate data from wearable trackers yielded AUC values around 0.94–1.0 for predicting MCI (26). Zhu et al. combined clinical variables with brain MRI markers (white-matter hyperintensity and baseline systolic blood pressure) in an XGBoost model, achieving AUC 0.9442 and accuracy 94.32% (27). These findings indicate that ML models using non-imaging predictors can reach AUCs in the range of ~0.75–0.85 and that incorporating vascular profiles, digital biomarkers, or imaging features may further improve performance. Overall, our results are broadly consistent with the literature and suggest that ML on routine clinical features could enhance community cognitive screening while leaving room for augmentation with more advanced data modalities.

Mechanisms and interpretability

The model’s top features have clear links to known mechanisms of cognitive decline. Older age and female sex increased predicted MCI risk in our SHAP analysis, consistent with established epidemiology. Education and social engagement appeared as protective factors: the 2020 Lancet Commission highlighted education, physical activity, and social contact as key factors that reduce dementia risk (28). Chronic conditions (hypertension and diabetes) act via vascular and metabolic pathways, as illustrated by the stroke-risk model in which transient ischemic attack, diabetes, and hypertension were the top predictors (21). Frequent outpatient visits or high chronic disease counts likely reflect overall health burden and were associated with higher predicted risk. Depressive symptoms (high CES-D scores) also emerged as important, aligning with evidence that depression is a modifiable risk factor for dementia (29).

Digital biomarker studies further underscore relevant pathways. For example, Xu et al. found that heart-rate variability and physical activity features were among the most important predictors of MCI (30), linking autonomic and activity factors to cognitive decline. Imaging-based models offer complementary insights: Zhu et al. reported that white-matter hyperintensity scores and elevated systolic blood pressure were top features in their XGBoost model (27), supporting vascular contributions to MCI. In summary, our SHAP explanations show that age, sex, education, social support, and mood drive the model’s predictions in a clinically plausible manner. This concordance with known clinical and emerging factors increases confidence in the model and may help clinicians understand and trust its predictions in practice.

Threshold trade-offs and screening context

The choice of operating threshold has important practical implications. In our study, raising the threshold to achieve ~80% sensitivity markedly increased the false-positive rate. In community screening, higher sensitivity (at the cost of lower specificity) may be preferred to capture most true cases, whereas in specialized or resource-limited settings a higher threshold could reduce unnecessary referrals. This trade-off must be carefully considered: many false positives would lead to extra referrals, testing, and patient anxiety, while the default high-specificity setting would miss many true cases. Ultimately, the optimal threshold depends on local resources and acceptable risk levels. Using the individual predicted probabilities, we derived operating thresholds and evaluated net benefit via decision-curve analysis to identify clinically relevant operating points (31).

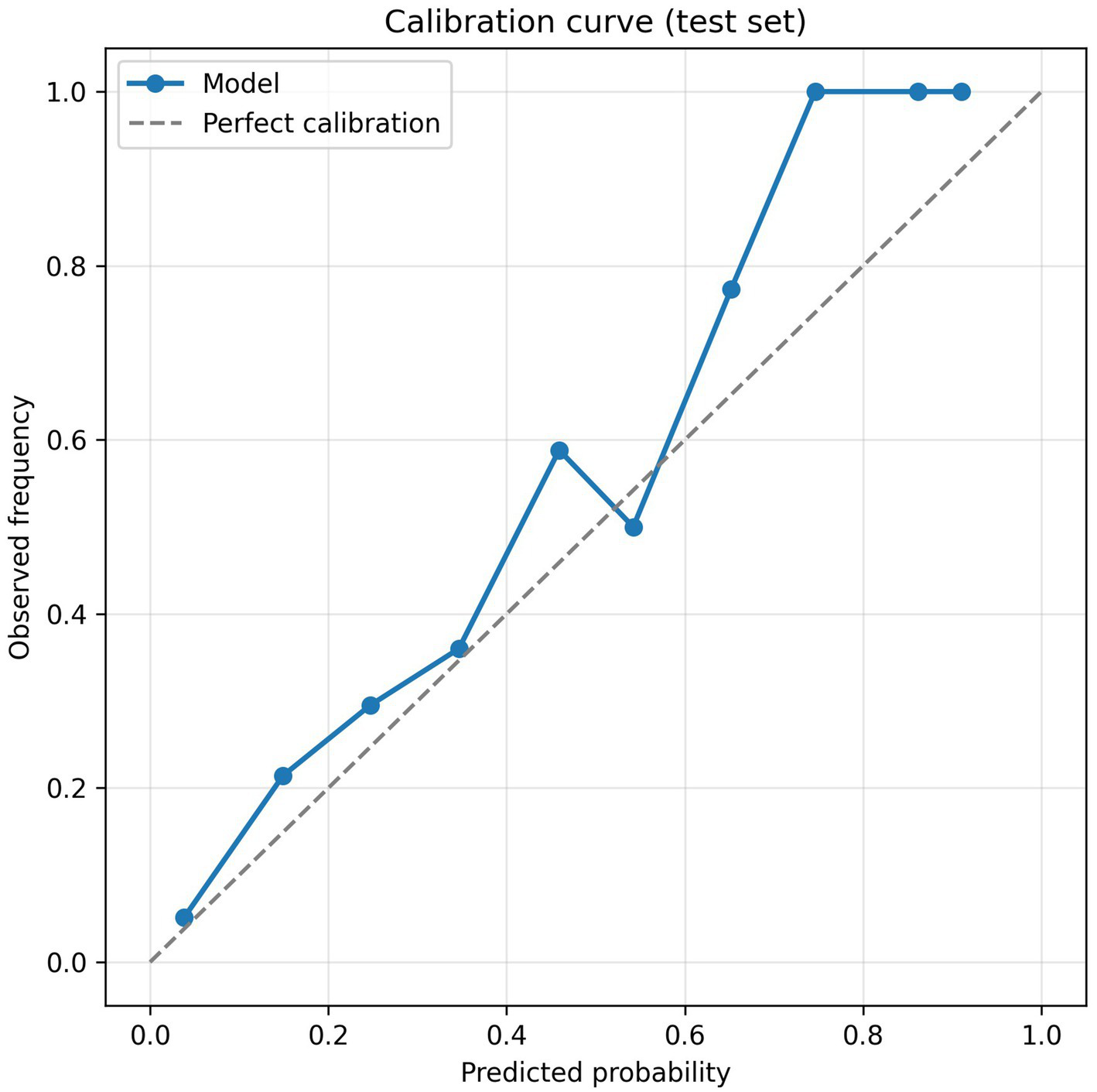

Calibration and clinical utility

Beyond discrimination, a valid prediction model should be well calibrated and its clinical net benefit evaluated. The calibration curve (Figure 6) showed close agreement between predicted probabilities and the observed incidence of MCI, indicating good calibration. As shown in Figure 7, the decision-curve analysis demonstrated that the Gradient Boosting model provided a higher net benefit than both the “screen-all” and “screen-none” strategies across most threshold probabilities, suggesting potential clinical utility.

Figure 6

Calibration curve for the Gradient Boosting model on the test set.

Figure 7

Decision-curve analysis for the Gradient Boosting model (net benefit vs. threshold probability for the model, “screen-all,” and “screen-none” strategies).

External validity and bias assessment

We acknowledge several limitations and potential sources of bias. First, our sample is from community health centers in one region, so selection bias is possible and generalizability is uncertain. Second, predictors were extracted from routine EHR data, which may contain misclassification or missing entries. Third, the MCI outcome was based on outpatient cognitive screening (e.g., MoCA or AD8) rather than biomarker confirmation, introducing potential misdiagnosis. Finally, we have only performed internal validation; no external cohort was tested. These factors (participant selection, predictor/outcome measurement, and analysis) could introduce bias or limit performance elsewhere. For example, a cross-sectional study in northern Peru found high prevalence of MCI and dementia and identified age, low education, hypertension, and hearing loss as significant factors (32). Such differences in prevalence and risk profiles suggest that models developed in one region may not perform as well elsewhere. We attempted to mitigate overfitting through cross-validation, but future work must test the model in independent cohorts to confirm its transportability and adjust for any bias, using tools such as the Prediction model Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool (PROBAST) (12).

We also recognize the importance of monitoring model fairness across demographic and socioeconomic subgroups and of adapting to potential distribution shifts over time. Plans for periodic recalibration, updating, and performance auditing will therefore be included in our external validation protocol.

Application prospects and future work

Our results suggest potential for developing a decision-support tool to aid community dementia screening; however, such a tool should only be pursued after external validation, calibration, and net-benefit analyses confirm its clinical value. Inspired by similar work [e.g., Fernández-Blázquez et al. provided an online MCI risk calculator using non-imaging data (7)], we plan to package our model into a user-friendly application contingent on further validation. Future tools might also incorporate variables identified in high-risk stroke cohorts (e.g., transient ischemic attack, diabetes, education, hypertension) (21) and include digital biomarkers. The wearable-sensor study shows that aggregating physical activity, sleep, and heart-rate signals yields high discrimination (22), suggesting that mobile devices and telehealth could enrich risk stratification. Before real-world deployment, further steps are needed: prospective validation in external cohorts, integration with EHR systems, and evaluation of usability and cost-effectiveness. Pilot studies could assess how using the model affects referral rates and early diagnosis in practice. In the long term, such tools could enable more targeted cognitive assessments and preventive interventions for at-risk older adults.

Conclusion

In summary, machine learning applied to routine community outpatient data can identify older adults at risk of mild cognitive impairment. Our Gradient Boosting model provided good discrimination (AUC ≈ 0.85) and highlighted well-known risk factors (age, education, depression, etc.) in its predictions. Although further validation is needed, this approach could augment existing screening programs. By enabling earlier detection of at-risk individuals, a deployed model could prompt timely cognitive assessments and interventions to slow cognitive decline.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Shaoxing People’s Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TY: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JP: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by Medical Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (2023KY1237).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, we used a large language model for English grammar editing and code formatting. All content, results, and interpretations were produced by the authors.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declared that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors used a large language model for English language editing and code formatting. Generative AI was not used to generate scientific content, data analyses, results, or conclusions. The authors take full responsibility for the final content.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2026.1718791/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

MCI, Mild cognitive impairment; EHR, Electronic health record; ML, Machine learning; AUC, Area under the (ROC) curve; PPV, Positive predictive value; NPV, Negative predictive value; F1, F1-score.

References

1.

Salari N Lotfi F Abdolmaleki A Heidarian P Rasoulpoor S Fazeli J et al . The global prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in geriatric population with emphasis on influential factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. (2025) 25:313. doi: 10.1186/s12877-025-05967-w,

2.

Wu W Chen G Ren X Zhao Y Yu Z Peng H et al . The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in China: evidence from a meta-analysis and systematic review of 393,525 adults. Neuroepidemiology. (2025) 59:259–76. doi: 10.1159/000539802,

3.

Borson S Small GW O’Brien Q Morrello A Boustani M . Understanding barriers to and facilitators of clinician–patient conversations about brain health and cognitive concerns in primary care: a systematic review and practical considerations. BMC Prim Care. (2023) 24:233. doi: 10.1186/s12875-023-02185-4,

4.

Salmon DP Malkina A Johnson ML Gigliotti C Little EA Galasko D . Effectiveness and utilization of a cognitive screening program for primary geriatric care. Alzheimer's Res Ther. (2025) 17:23. doi: 10.1186/s13195-024-01637-y,

5.

Amjad H Roth DL Sheehan OC Lyketsos CG Wolff JL Samus QM . Underdiagnosis of dementia: an observational study of patterns in diagnosis and awareness in US older adults. J Gen Intern Med. (2018) 33:1131–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4377-y,

6.

Akter S Liu Z Simoes EJ Rao P . Using machine learning and electronic health record (EHR) data for the early prediction of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. (2025) 12:100169. doi: 10.1016/j.tjpad.2025.100169,

7.

Fernández-Blázquez MA de León JMR-S Sanz-Blasco R Verche E Ávila-Villanueva M Gil-Moreno MJ et al . XGBoost models based on non-imaging features for the prediction of mild cognitive impairment in older adults. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:29732. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-14832-0

8.

Collins GS Moons KGM Dhiman P Riley RD Beam AL Van Calster B et al . TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ. (2024) 385:e078378. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-078378,

9.

Efthimiou O Seo M Chalkou K Debray TPA Egger M Salanti G . Developing clinical prediction models: a step-by-step guide. BMJ. (2024) 386:e078276. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-078276,

10.

Vickers AJ Van Calster B Steyerberg EW . A simple, step-by-step guide to interpreting decision curve analysis. Diagn Progn Res. (2019) 3:18. doi: 10.1186/s41512-019-0064-7,

11.

von Elm E Altman DG Egger M Pocock SJ Gøtzsche PC Vandenbroucke JP et al . Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. (2007) 335:806–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD,

12.

Wolff RF Moons KGM Riley RD Whiting PF Westwood M Collins GS et al . PROBAST: a tool to assess the risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies. Ann Intern Med. (2019) 170:51–8. doi: 10.7326/M18-1376,

13.

Chinese Society of Neurology; Dementia and Cognitive Disorders Committee . Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of dementia and cognitive impairment (V): diagnosis and treatment of mild cognitive impairment (in Chinese). Natl Med J China. (2018) 98:1294–301. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2018.17.003

14.

White IR Royston P Wood AM . Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. (2011) 30:377–99. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067,

15.

Salmi M Atif D Oliva D Abraham A Ventura S . Handling imbalanced medical datasets: review of a decade of research. Artif Intell Rev. (2024) 57:274. doi: 10.1007/s10462-024-10884-2

16.

Pedregosa F Varoquaux G Gramfort A Michel V Thirion B Grisel O et al . Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res. (2011) 12:2825–30.

17.

Lundberg SM Lee SI . A unified approach to interpreting model predictions In: Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (NeurIPS 2017) Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc. (2017). 4765–74.

18.

Sadeghi Z Kermani MK Abhari S Escorcia-Gutierrez J Gamarra M Muhammad K et al . Efficient leukocytes detection and classification in microscopic blood images using convolutional neural network coupled with a dual attention network. Comput Biol Med. (2024) 173:108146. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108146

19.

Li Q Yang X Xu J Guo Y He X Hu H et al . Early prediction of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias using real-world electronic health records. Alzheimers Dement. (2023) 19:3506–18. doi: 10.1002/alz.12967,

20.

Hu S Shu X Yu G Wu X Välimäki M Feng H . A risk prediction model based on machine learning for cognitive impairment among Chinese community-dwelling elderly people with normal cognition. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e20298. doi: 10.2196/20298

21.

Yan F-J Chen X-H Quan X-Q Wang L-L Wei X-Y Zhu J-L . Development and validation of an interpretable machine learning model—Predicting mild cognitive impairment in a high-risk stroke population. Front Aging Neurosci. (2023) 15:1180351. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2023.1180351

22.

Xu Q Kim Y Chung K Schulz P Gottlieb A . Prediction of mild cognitive impairment status: pilot study of machine learning models based on longitudinal data from fitness trackers. JMIR Form Res. (2024) 8:e55575. doi: 10.2196/55575

23.

Richter-Laskowska M Sobotnicka E Bednorz A . Cognitive performance classification of older patients using machine learning and electronic medical records. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:6564. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-90460-y

24.

Fouladvand S Noshad M Periyakoil VJ Chen JH . Machine learning prediction of mild cognitive impairment and its progression to Alzheimer’s disease. Health Sci Rep. (2023) 6:e1438. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.1438,

25.

Livingston G Huntley J Liu KY Costafreda SG Selbæk G Alladi S et al . Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet. (2024) 404:572–628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01296-0

26.

Li S Li K Liu J Huang S Wang C Tu Y et al . A new method for community-based intelligent screening of early Alzheimer’s disease populations based on digital biomarkers of the writing process. Front. Comput. Neurosci. (2025) 19:1564932. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2025.1564932

27.

Zhu X Liu S Ji C Liu JJ Huang C . Machine learning-based prediction of mild cognitive impairment among individuals with normal cognitive function using combined clinical and imaging variables. Front Neurol. (2024) 15:1352423. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1352423,

28.

Livingston G Huntley J Sommerlad A Ames D Ballard C Banerjee S et al . Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the lancet commission. Lancet. (2020) 396:413–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6,

29.

Byers AL Yaffe K . Depression and risk of developing dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. (2011) 7:323–31. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.60,

30.

Wang J Zhou Z Cheng S Zhou L Sun X Song Z et al . Dual-task turn velocity—a novel digital biomarker for mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. (2024) 16:1304265. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2024.1304265

31.

Vickers AJ Van Calster B Steyerberg EW . Decision curve analysis: a method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Mak. (2006) 26:565–74. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06295361,

32.

Zegarra-Valdivia J Pérez-Fernández L Casimiro-Arana M Arana-Nombera H Gallegos-Manayay VN Oliva-Piscoya MR et al . Prevalence and risk factors for mild cognitive impairment and dementia in northern Peru. Front Public Health. (2025) 13:1567073. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1567073

Summary

Keywords

calibration, decision curve analysis, electronic health records, machine learning, mild cognitive impairment, risk prediction

Citation

Ye T and Peng J (2026) AI-assisted screening for mild cognitive impairment using routine EHR data: a Gradient Boosting approach. Front. Neurol. 17:1718791. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2026.1718791

Received

06 October 2025

Revised

21 January 2026

Accepted

29 January 2026

Published

17 February 2026

Volume

17 - 2026

Edited by

Juan F. Cardona, University of the Valley, Colombia

Reviewed by

Kuk-In Jang, PANAXTOS Corporate Research Institute, Republic of Korea

Weiqi Jiao, Boston Strategic Partners Inc., United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Ye and Peng.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jianghua Peng, peng5300@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.