Abstract

Background:

Hereditary hearing loss demonstrates significant genetic heterogeneity, involving diverse genes and variation types. Autosomal dominant forms present particular challenges in variant interpretation due to variable expressivity.

Objectives:

This study aimed to clinically and molecularly characterize a multi-generational family with autosomal dominant hereditary hearing loss, and to functionally validate the pathogenicity of an identified novel variant.

Methods:

Comprehensive clinical evaluations included audiometric testing and medical history review. Genetic analysis employed whole-exome sequencing followed by Sanger validation. Functional characterization involved minigene splicing assays and transcript analysis to assess the impact on splicing mechanisms.

Results:

Affected individuals exhibited post-lingual, bilateral, symmetric, progressive sensorineural hearing loss, initially affecting high frequencies. We identified a novel GSDME mutation (NM_001127453.2:c.1123G>T; p.Glu375Ter) that disrupts an exon splicing enhancer, causing exon 8 skipping and frameshift alterations. Functional assays confirmed reduced enhancer activity and aberrant splicing. Literature review of 20 reported mutations revealed substantial phenotypic variability and highlighted limitations of splice prediction algorithms.

Conclusions:

Our findings expand the GSDME mutation spectrum and provide functional evidence supporting a pathogenic role for non-sense variants through splicing disruption mechanisms. This study reinforces the potential gain-of-function hypothesis for GSDME-associated hearing loss and emphasizes the necessity of functional validation for accurate variant interpretation.

1 Introduction

Hearing loss represents a major global health burden with a strong genetic basis, where inherited factors contribute to 40–60% of cases across a highly heterogeneous landscape of over 150 implicated genes (1). This heterogeneity poses a significant challenge in autosomal dominant non-syndromic hearing loss (ADNSHL), where variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance often complicate the interpretation of genetic variants.

Deafness autosomal dominant 5 (DFNA5), caused by mutations in the GSDME gene, stands out for its exceptionally same pathogenic mechanism. Since its initial linkage to chromosome 7p15 (2), research has revealed that virtually all pathogenic GSDME variants converge on a single molecular outcome: the complete skipping of exon 8 in the mRNA (3, 4). This results in a consistent, truncated protein product. The invariance of this splicing defect across diverse mutations, coupled with normal hearing in GSDME-knockout mice, provides compelling evidence for a gain-of-function (GOF) pathogenesis (5). Historically, haploinsufficiency mechanisms-related non-sense or frameshift variants of GSDME were thought to be benign (6).

This study describes a large Chinese ADNSHL pedigree and identified a novel, segregating non-sense variant in GSDME (c.1123G>T; p.Glu375Ter). Minigene assays confirmed this variant causes exon 8 skipping. Our finding challenges the traditional benign classification of GSDME non-sense variants, expands the mutational spectrum of DFNA5, and necessitates a revised mechanistic understanding of how PTCs can lead to GOF pathology.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Subjects and clinical characterization

This study included a large Han Chinese pedigree with sensorineural hearing loss, consisting of 72 family members. Each member provided demographic information, age of onset, illness development, obstetric history, noise exposure, ototoxic medication use, head trauma, infectious infections, family history, and other pertinent clinical symptoms. Audiological assessments and otolaryngological examinations were conducted on probands, including pure-tone audiometry, impedance testing, distortion product otoacoustic emissions, auditory brainstem response, and temporal bone CT scans. Pure-tone audiometry was performed to assess the hearing of other family members using frequencies of 0.125 kHz, 0.25 kHz, 0.5 kHz, 1 kHz, 2 kHz, 4 kHz, and 8 kHz via air conduction bilaterally. The average values of the thresholds of air conduction were determined at 500–4,000 Hz to determine the degree of hearing loss in the family. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of West China Hospital [2021 Audit (190)]. All family members provided written informed consent before participating in this study.

2.2 Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

Approximately 5 mL of peripheral blood was collected from the proband and family members. DNA was isolated using the AxyPrep-96 Blood Genomic DNA Kit (Axygen BioScience, Union City, CA, USA). Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) sequencing was performed on the proband (III-2) and another family member (VI-4) using DNBSEQ-T7 sequencing instruments (MGI, Shenzhen, China), with paired-end reads of 100 base pairs. The sequenced reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38/hg38) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA v0.7.10). Subsequent processing, including duplicate marking, local realignment, and base quality score recalibration, was performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK v4.0). Variant calling was conducted with GATK HaplotypeCaller. The identified variants were filtered using the following criteria: (1) population frequency < 1% in the gnomAD and an in-house Chinese database; (2) presence in a custom panel of 189 genes known to be associated with hearing loss (Supplementary material); and (3) compatible with an autosomal dominant inheritance model. The functional impact of prioritized variants was predicted using PolyPhen-2, MutationTaster, and SIFT.

2.3 Segregation analysis Sanger sequencing

Sanger sequencing was used for variants validation. Primer3 online (https://www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/primer3plus/primer3plus.cgi) was used to design primers for the GSDME gene variants. A pair of exon 8 primers (forward, 5′-CCGTCAGTGAAATGTAGCC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TTCCACAGTTACCACCTCTG-3′) across the intron-exon boundaries were used to span the sequences. One hundred ng Genomic DNA (gDNA) was used as a template in a total reaction volume of 15 μL (2 × PrimeSTAR Max Premix 7.5 μl, primer forward 10 μmol/L 0.25 μL, primer reverse 10 μmol/L 0.25 μL, and dH2O to 15 μL). PCR was performed with an initial denaturation at 98 °C for 1 min, followed by 35 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 5 s, and 72 °C for 20 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Direct sequencing of the DNA in both directions was performed by Sangon Biotech (Chengdu, China). The reference sequence of GSDME used was GenBank NM_001127453.2.

2.4 In vitro splicing analysis

The pSPL3 vector, pre-purchased by our research group, was utilized to construct plasmids for in vitro splicing validation. This vector has 6031 base pairs and comprises an SV40 promoter, as well as two exons, SD6 and SA2. Specific primers with XhoI and BamHI restriction enzyme sites (F5′-CCCTCGAGCCGTCAGTGAAATGTAGCC3′ and R5′-CGGGATCCTTCCACAGTTACCACCTCTG3′) were utilized to amplify a 471 bp fragment that encompasses exon 8 of GSDME. The PCR products and plasmid underwent digestion with XhoI (Takara, 1094S) and BamHI (Takara, 1010S) restriction enzymes, respectively. Subsequently, T4 ligase (Takara, 2011A) was used for ligation. The ligated products were then transformed into E.coli DH5α Competent Cells (Takara, 9057) for amplification. Finally, single colonies were selected for sequencing to confirm the accuracy of the mutation.

The mini-gene vector was transfected into COS-7 cells using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, L3000015). After 48 h, cells were collected and RNA was extracted using the Trizol (Invitrogen, 15596018). The extracted RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with a reverse transcription kit (Takara, RR047A). Amplification was performed using exon-specific primers (SD6-F: TCTGAGTCACCTGGACAACC and SA2-R: ATCTCAGTGGTATTTGTGAGC) from pSPL3. PCR was performed with an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 15 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel. Direct sequencing of the DNA in both directions was performed by Sangon Biotech (Chengdu, China). Three controls were included in each transfection experiment: (1) the wild-type (WT) construct (negative control for aberrant splicing); (2) a construct carrying a known pathogenic splice-site variant (c.991-21_991-19delTTCinsT) (positive control for exon 8 skipping); and (3) the empty pSPL3 vector (background control).

2.5 Literature review and splicing prediction

A thorough evaluation was undertaken on pathogenic variations of GSDME previously identified in persons. PubMed was used to conduct literature searches using the keywords (GSDME OR DFNA5) AND (hearing loss OR deafness). The most recent search occurred on March 22, 2024. Information was collected on the location of the variant, age of onset, audiometric manifestations, associated symptoms, and other systemic abnormalities documented in the literature in affected individuals.

The MANE SELECT transcript was used to convert all filtered pathogenic variants. dbscSNV, MaxEntScan, and Splice AI were used to predict the effect of mutations on splicing. In addition, ESEfinder 3.0 (https://esefinder.ahc.umn.edu) was used for splicing prediction.

3 Results

3.1 Clinical funding

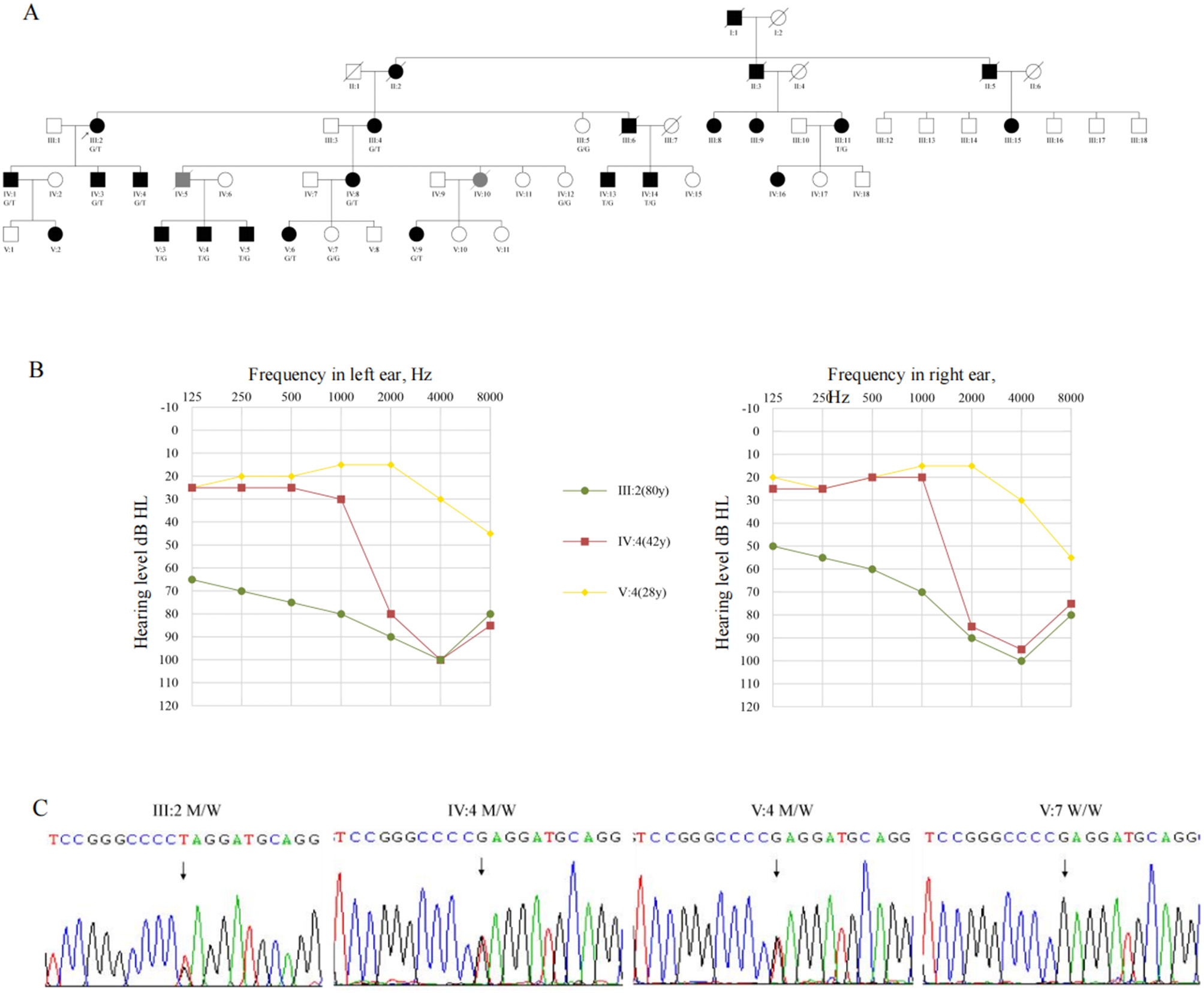

The pedigree(Figure 1A) shows a typical autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of hereditary hearing loss, covering five generations and including a total of 55 family members. There is no gender disparity among affected individuals in the pedigree. Hearing loss typically appears during the first or second decades of life. It is characterized by post-lingual, bilateral, symmetric, and progressive sensorineural deafness. Initially, it affects high frequencies and gradually extends to involve all frequencies (Figure 1B). Notably, individuals IV-1 and IV-3 present with asymmetric hearing loss due to otitis media. Most patients report intermittent tinnitus without symptoms of vertigo or balance disturbances and with normal intellectual and cognitive functions. None of the patients had a history of aminoglycoside exposure or noise exposure before presentation, and physical exams were normal. High-resolution CT scan of the temporal bone showed no abnormality. Thirteen patients showed moderate to severe bilateral sensorineural hearing loss during auditory testing. The audiograms showed that the high frequencies were affected at the beginning and that the middle and low frequencies were gradually affected with increasing age (Table 1). Although V-8 currently has average hearing thresholds within the normal range, the audiogram showed a significant decline in high-frequency hearing (Figure 1B).

Figure 1

The pedigree presents autosomal dominant non-syndromic sensorineural deafness. (A) The pedigree of the family.  , Proband; T, Mutation allele; G, Wild-type allele. (B) The pure tone audiometry of III:2, IV-4, V-4. (C) Sanger sequencing of III:2, IV-4, V-4, V-7. T, Mutation allele; G, Wild-type allele.

, Proband; T, Mutation allele; G, Wild-type allele. (B) The pure tone audiometry of III:2, IV-4, V-4. (C) Sanger sequencing of III:2, IV-4, V-4, V-7. T, Mutation allele; G, Wild-type allele.

Table 1

| Subjects | Age of test (years) | Age of onset (years) | Nucleotide change | PTA-right (dB HL) | PTA-left (dB HL) | Tinnitus | Vertigo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III:2 | 80 | 10+ | c.1123G>T | 80 | 86.25 | Y | N |

| III:4 | 77 | 20+ | c.1123G>T | 87.5 | 88.75 | Y | N |

| III:5 | 71 | N | Wide type | 32.5 | 43.75 | N | N |

| III:11 | 70 | 20+ | c.1123G>T | 100 | 77.5 | NA | NA |

| IV:1 | 57 | 20+ | c.1123G>T | 81.25 | 100 | NA | NA |

| IV:3 | 49 | 19 | c.1123G>T | 68.75 | 100 | Y | N |

| IV:4 | 42 | 19 | c.1123G>T | 55 | 58.75 | Y | N |

| IV:8 | 55 | 15 | c.1123G>T | 87.5 | 92.5 | Y | N |

| IV:12 | 44 | N | Wide type | 20 | 25 | N | N |

| IV:13 | 43 | 18 | c.1123G>T | 80 | 77.5 | Y | N |

| IV:14 | 40 | 10+ | c.1123G>T | 95 | 80 | Y | N |

| V:3 | 30 | 10+ | c.1123G>T | 60 | 57.5 | Y | N |

| V:4 | 28 | 20+ | c.1123G>T | 20 | 20 | N | N |

| V:5 | 26 | 22 | c.1123G>T | 35 | 33.75 | Y | N |

| V:6 | 29 | 23 | c.1123G>T | 63.75 | 69 | Y | N |

| V:7 | 28 | N | Wide type | 15 | 12.5 | N | N |

| V:9 | 24 | 18 | c.1123G>T | 55 | 58.75 | Y | N |

Summary of clinical data for family members.

3.2 Identification of GSDME mutation

Whole-genome sequencing of the proband (III-2) and an unaffected relative (IV-4) initially yielded multiple variants in hearing loss-associated genes. After filtering against population databases and enforcing an autosomal dominant inheritance model, a single candidate variant emerged: a heterozygous c.1123G>T transition in exon 8 of GSDME (NM_001127453.2), predicted to introduce a premature termination codon (p.Glu375Ter). Sanger sequencing confirmed this variant co-segregated perfectly with the hearing loss phenotype in the family (Figure 1C) and was absent from gnomAD, 1,000 Genomes, and our in-house controls.”

“A second heterozygous variant in MITF (c.1156G>C, p.Val386Leu) was also identified in both sequenced individuals. However, it was excluded as causative due to phenotype mismatch (no features of Waardenburg syndrome) and lack of co-segregation within the pedigree.

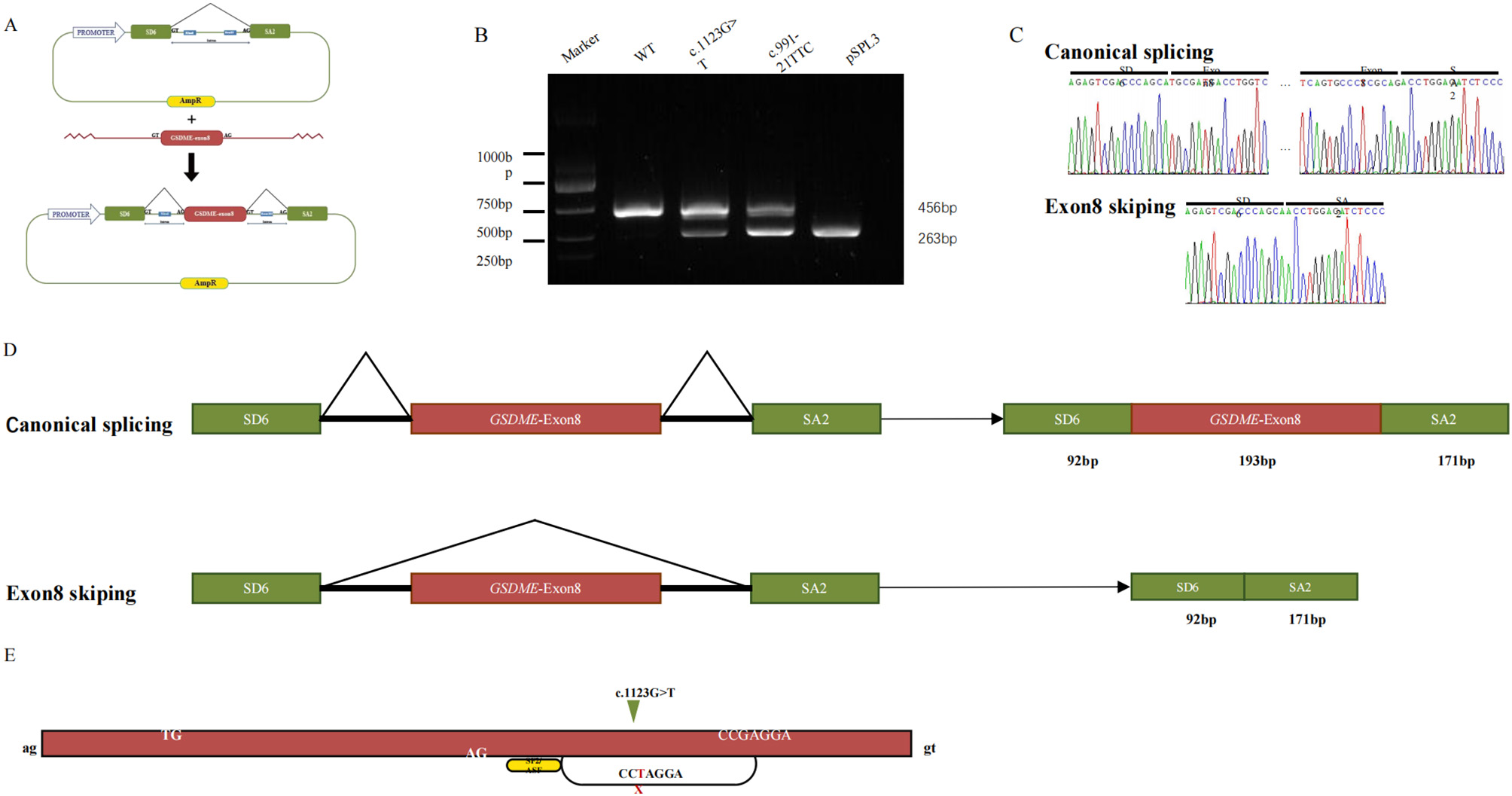

3.3 Splicing analysis

The in vitro minigene assay was employed to determine the effect of c.1123G>T on splicing. RT-PCR analysis of RNA from transfected COS-7 cells yielded a single 456-bp product for the wild-type construct, which sequencing confirmed contained the vector-derived SD6 exon, GSDME exon 8, and the SA2 exon (Figures 2B, C). In contrast, the mutant construct produced two products: the expected 456-bp wild-type band and a predominant aberrant band of 263 bp (Figure 2B). Sequencing of the smaller band confirmed the complete absence of GSDME exon 8, indicating direct splicing from SD6 to SA2 (Figures 2C, D). This exon skipping creates a frameshift, introducing a premature termination codon at position 372 and predicting a truncated protein lacking the C-terminal 126 amino acids.”

Figure 2

In vitro analysis of splice site variant. (A) Mini-gene splicing analysis and schematic representation of GSDME exon 8 and splicing factor binding. (B) Splicing-assay products were separated by agarose gel. (C) Sanger sequencing of the bands. (D) The schematic diagram of splicing patterns. (E) Predicted the ESE of the novel variant in this study, wild-type black and mutant red.

“Bioinformatic analysis using ESEfinder 3.0 suggested that the c.1123G>T substitution disrupts a binding motif for the splicing factor SF2/ASF, potentially reducing exonic splicing enhancer activity and contributing to exon 8 skipping (Figure 2E).

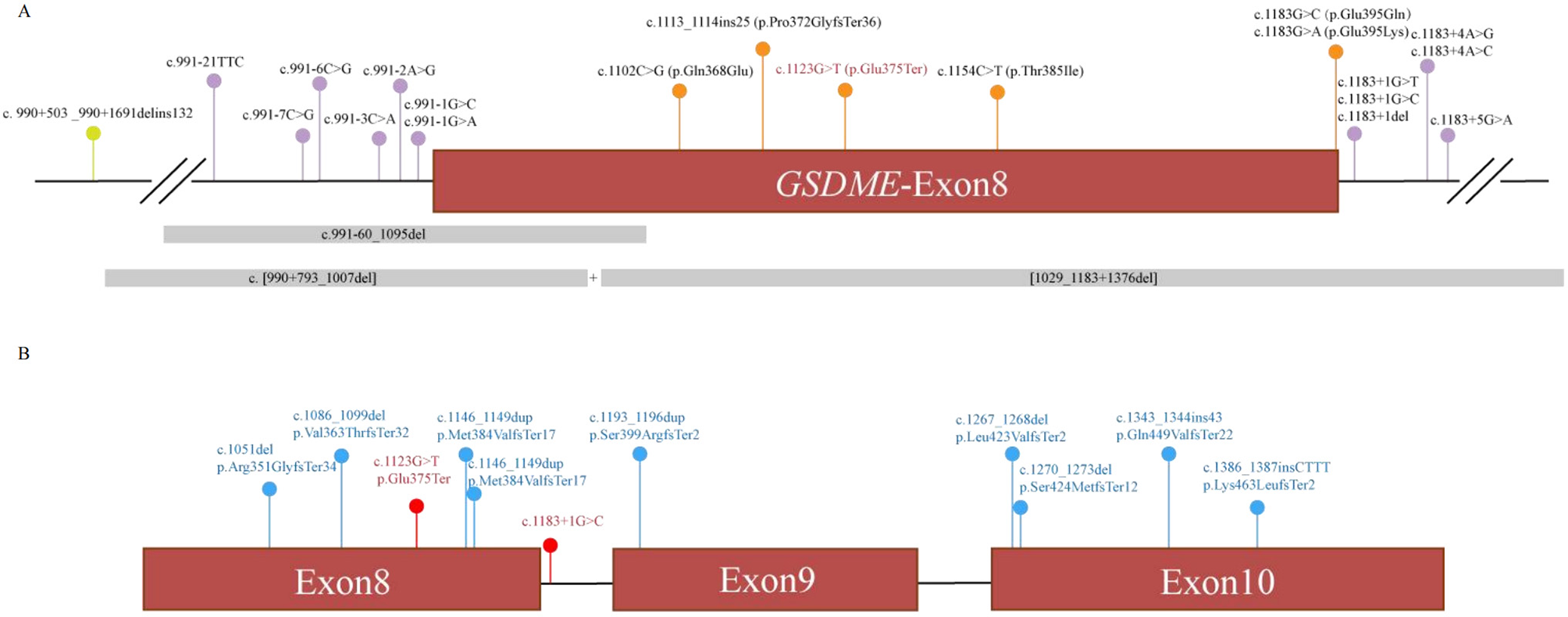

3.4 Phenotypic analysis and splice predictions of different variants

A review of the literature identified 20 previously reported pathogenic GSDME variants, predominantly clustered around exon 8 (Figure 3A, Table 2). All experimentally tested variants have been shown to cause exon 8 skipping. The associated phenotypes consistently involve progressive, high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss with an onset ranging from 5 to 50 years, often accompanied by tinnitus. Considerable intra- and inter-familial phenotypic variability was noted, even for the same mutation.

Figure 3

(A) Novel (red) and previously described (black) variants alignment to GSDME exon 8 and its flanking introns. Orange, variants in exon; purple, variants in splice region; green, variants in intron; gray, CNV; (B) LOF variants in GDC. Red, pathogenic variants; blue, begin variants.

Table 2

| Mutation (NM_001127453.2) | Location | Effect | Age of onset (years) | PTA | Tinnitus | Vertigo | Country | dbscSNV | MaxEntScan | Splice AI | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.991-60_1095del | Intron 7-Exon 8 | Exon 8 skipping | 6–20 | Sloping | NA | NA | France | NA | NA | + | (17) |

| c.[990+793_1007del; 1029_1183+1376del] | Intron 7-Intron 8 | Exon 8 skipping | 6 | Sloping to flat | NA | NA | France | NA | NA | NA | (17) |

| c.990+503_990+1691delins132 | Intron 7 | Exon 8 skipping | 5–15 | Sloping | NA | NA | Dutch | NA | NA | NA | (14) |

| c.991-15_991-13del | Intron 7 | Exon 8 skipping | 20–31 | Sloping to flat | Y | – | China | NA | NA | – | (15) |

| 20 | Sloping to flat | NA | – | Korea | NA | NA | – | (18) | |||

| 7–30 | Sloping | NA | NA | China | NA | NA | – | (19) | |||

| 20–35 | Sloping | NA | NA | China | NA | NA | – | (20) | |||

| 17–21 | Cookie-bite | NA | NA | China | NA | NA | – | (20) | |||

| 17 | Sloping | NA | NA | China | NA | NA | – | (20) | |||

| 25–35 | Sloping to flat | Y | – | China | NA | NA | – | (21) | |||

| 10–20 | Sloping | NA | NA | USA | NA | NA | – | (3) | |||

| 6–13 | flat | NA | NA | USA | NA | NA | – | (15) | |||

| c.991-7C>G | Intron 7 | Exon 8 skipping | 10 | Sloping | NA | NA | China | – | + | – | (20) |

| c.991-6C>G | Intron 7 | Exon 8 skipping | 0–40 | Sloping | NA | NA | Dutch | – | + | – | (22) |

| c.991-3C>A | Intron 7 | Exon 8 skipping | 20–39 | Sloping | Y | - | China | + | + | – | (15) |

| c.991-2A>G | Intron 7 | Exon 8 skipping | 13–61 | Sloping to flat | NA | NA | China | + | + | + | (23) |

| 10–20 | Sloping | NA | NA | USA | + | + | + | (3) | |||

| 8–18 | Sloping | NA | NA | China | + | + | + | (24) | |||

| c.991-1G>C | Intron 7 | Exon 8 skipping | 20–40 | Sloping to flat | NA | NA | China | + | + | + | (25) |

| 18–30 | Cookie-bite | NA | NA | China | + | + | + | (20) | |||

| c.1102C>G | Exon 8 | Exon 8 skipping | 10–20 | Sloping to flat | NA | NA | USA | NA | NA | – | (3) |

| c.1113_1114ins25 | Exon 8 | Frameshift variant | 7–30 | Sloping to flat | NA | – | China | NA | NA | – | (26) |

| c.1123G>T | Exon 8 | Exon 8 skipping | 10–30 | Sloping | Y | N | China | NA | NA | + | This study |

| c.1154C>T | Exon 8 | Exon 8 skipping | 10–20 | Sloping to flat | NA | NA | Iran | NA | NA | + | (3) |

| c.1183G>C | Exon 8 | Exon 8 skipping | NA | NA | NA | NA | China | + | + | + | (27) |

| c.1183G>A | Exon 8 | Exon 8 skipping | 10–20 | Sloping | NA | NA | USA | + | + | + | (3) |

| c.1183+1G>T | Intron 8 | Exon 8 skipping | 15–50 | Flat | NA | NA | China | + | + | + | (20) |

| c.1183+1G>C | Intron 8 | Exon 8 skipping | 20 | Sloping to flat | – | – | China | + | + | + | (20) |

| c.1183+1del | Intron 8 | Exon 8 skipping | 12–30 | Sloping | NA | – | China | NA | NA | + | (16) |

| 8–30 | Sloping | Y | – | China | NA | NA | + | (28) | |||

| c.1183+4A>G | Intron 8 | Exon 8 skipping | 11–50 | Sloping | NA | NA | China | – | + | + | (5) |

| c.1183+5G>A | Intron 8 | Exon 8 skipping | NA | NA | NA | NA | Australia | + | + | + | (29) |

Summary of all reported GSDME variants leading to hearing loss.

In silico splice prediction tools (SpliceAI, dbscSNV, MaxEntScan) were applied to these variants. Their performance varied, with MaxEntScan achieving 100% accuracy for variants within canonical splice regions, while SpliceAI's accuracy was lower (66.7%) despite its ability to assess all genomic regions (Table 2).

4 Discussion

In this study, we report a novel GSDME non-sense variant (c.1123G>T; p.Glu375Ter) in a large autosomal dominant deafness Chinese family. To our knowledge, this is the first reported non-sense variant causing DFNA5. This finding directly challenges the long-held notion that non-sense/frameshift variants in GSDME are benign due to haploinsufficiency (6–8), compelling a reassessment of how premature termination codons (PTCs) paradoxically lead to gain-of-function (GOF) disorders. The determination of pathogenicity heavily relies on the interpretation of variant, encompassing predictions of the potential consequences resulting from base alterations, which might not always align with biological processes. A multifaceted, comprehensive analysis of variant pathogenicity, leveraging various interpretative dimensions, can aid in averting misdirection stemming from “very strong” evidence.

The present findings serve to further emphasize the consistency of the pathogenic mechanisms of DFNA5. As outlined in our analysis and in previous reports (see Table 2), the vast majority of pathogenic GSDME variants, whether involving splice-site alterations in introns 7/8 or missense changes within exon 8, ultimately result in the same pathological outcome: the skipping of exon 8 at the mRNA level. The c.1123G>T variant, despite being predicted as a non-sense variant, has been shown to share the same pathogenic mechanism. Minigene analysis unequivocally demonstrates that it also causes complete skipping of exon 8 (Figure 2). This variant was found to be mechanistically aligned with all other known DFNA5-causing variants, rather than with the presumed loss-of-function (LOF) allele.

Traditionally, non-sense variants and splicing site variants have been viewed as distinct pathogenic pathways. But this non-sense variant unequivocally caused exon skipping. This compelled us to look beyond conventional categories to non-sense-associated altered splicing (NAS), a mechanism that bridges these seemingly separate processes (9, 10). The phenomenon of NAS is characterized by the influence of a PTC on splice site selection, frequently resulting in the exclusion of the exon containing the PTC. This process is believed to be a strategy employed to evade the non-sense-mediated decay (NMD) pathway (11). Bioinformatic analysis suggests that the c.1123G>T nucleotide substitution disrupts a putative binding site for the serine/arginine-rich splicing factor SF2/ASF (an exonic splicing enhancer, ESE) (Figure 2E) (12). The hypothesis is that this weakening of exon definition shifts the balance toward the recognition of a cryptic or competing splice site, resulting in exon 8 skipping. This model elegantly reconciles the non-sense nature of our variant with the established GOF mechanism of DFNA5, providing a specific molecular route by which a PTC can initiate the pathogenic splicing event.

The present study contributes a critical piece of evidence to the GOF hypothesis for DFNA5. It is demonstrated that the pathogenic determinant is not the variant type per se (missense or non-sense), but rather its final consequence on pre-mRNA processing. This principle is powerfully illustrated by our querying of population and clinical databases (Genetic Deafness Commons, GDC). As demonstrated in Figure 3B, LOF variants occurring before the critical exon 8 region are typically benign, whereas those that induce exon 8 skipping (e.g., splice-site variants and, as demonstrated in this study, this specific non-sense variant) are pathogenic. This finding provides compelling evidence that refutes the hypothesis of haploinsufficiency and instead highlights the toxic nature of the specific truncated protein resulting from exon 8 loss. This assertion contradicts the notion that the observed effects are merely a consequence of reduced protein dosage.

In accordance with preceding reports on DFNA5, the present pedigree demonstrates substantial inter- and intra-familial phenotypic variability with regard to both age of onset (ranging from the first to third decade) and progression rate (see Table 1) (13). This variability, also observed across different variants (see Table 2), suggests that the core “exon 8 skipping” event, while necessary, may not be sufficient to dictate the precise clinical course (13). The expression of disease is likely to be modulated by modifying genetic factors, environmental influences (e.g., noise), or stochastic processes in the cochlea. From a clinical diagnostic perspective, this variability underscores the necessity of prioritizing functional splicing assays over phenotype-based predictions when assessing GSDME variants in the exon 8 critical region.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of the present study. The minigene assay, while widely regarded as the gold standard for splicing analysis, is an in vitro model (PMID: 35716007). The NAS mechanism would be further validated by additional research using patient-derived cells or knock-in animal models in vivo, which would also make it easier to examine the downstream cytotoxic effects unique to this non-sense variant. Furthermore, the genetic modifiers underlying the observed phenotypic spectrum remain to be discovered. Finally, we have discovered and described the first pathogenic non-sense variant in GSDME's exon 8. The present study not only expands the variantal and mechanistic spectrum of DFNA5 by implicating NAS, but also fundamentally refines the genetic counseling framework for GSDME. It is now imperative that variants in this region are assessed for their splicing impact, regardless of their predicted protein-level effect. This finding serves to reinforce the unifying principle that DFNA5 pathogenesis converges exclusively on the gain-of-function mechanism triggered by exon 8 skipping.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we successfully identified a novel non-sense variant in the exon 8 of GSDME in a Chinese family with hereditary deafness. This variant causes NAS in exon 8, which was found to be causative for deafness. To date, this is the first report of a GSDME non-sense mutation leading to DFNA5, expanding the spectrum of GSDME mutations and phenotypes, and further confirming the pathogenic mechanism of GSDME as gain-of-function.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee on Biomedical Research, West China Hospital of Sichuan University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Ethical approval was not required for the studies on animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

BY: Writing – original draft, Methodology. MZ: Writing – original draft, Methodology. XL: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Validation. SW: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. YL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HY: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. QH: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2026.1752843/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Jiang L Wang D He Y Shu Y . Advances in gene therapy hold promise for treating hereditary hearing loss. Mol Ther. (2023) 31:934–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.02.001

2.

van Camp G Coucke P Balemans W van Velzen D van de Bilt C van Laer L et al . Localization of a gene for non-syndromic hearing loss (DFNA5) to chromosome 7p15. Hum Mol Genet. (1995) 4:2159–63. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2159

3.

Van Laer L Huizing EH Verstreken M van Zuijlen D Wauters JG Bossuyt PJ et al . Nonsyndromic hearing impairment is associated with a mutation in DFNA5. Nat Genet. (1998) 20:194–7. doi: 10.1038/2503

4.

Booth KT Azaiez H Kahrizi K Wang D Zhang Y Frees K et al . Exonic mutations and exon skipping: lessons learned from DFNA5. Hum Mutat. (2018) 39:433–40. doi: 10.1002/humu.23384

5.

Van Laer L Pfister M Thys S Vrijens K Mueller M Umans L et al . Mice lacking Dfna5 show a diverging number of cochlear fourth row outer hair cells. Neurobiol Dis. (2005) 19:386–99. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.01.019

6.

Cheng J Han DY Dai P Sun HJ Tao R Sun Q et al . A novel DFNA5 mutation, IVS8+4 A>G, in the splice donor site of intron 8 causes late-onset non-syndromic hearing loss in a Chinese family. Clin Genet. (2007) 72:471–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00889.x

7.

Van Laer L Meyer NC Malekpour M Riazalhosseini Y Moghannibashi M Kahrizi K et al . A novel DFNA5 mutation does not cause hearing loss in an Iranian family. J Hum Genet. (2007) 52:549–52. doi: 10.1007/s10038-007-0137-2

8.

Wang H Guan J Guan L Yang J Wu K Lin Q et al . Further evidence for “gain-of-function” mechanism of DFNA5 related hearing loss. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:8424. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26554-7

9.

Barny I Perrault I Rio M Dollfus H Defoort-Dhellemmes S Kaplan J et al . Description of two siblings with apparently severe CEP290 mutations and unusually mild retinal disease unrelated to basal exon skipping or nonsense-associated altered splicing. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2019) 1185:189–95. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-27378-1_31

10.

Sofronova V Fukushima Y Masuno M Naka M Nagata M Ishihara Y et al . A novel nonsense variant in ARID1B causing simultaneous RNA decay and exon skipping is associated with Coffin-Siris syndrome. Hum Genome Var. (2022) 9:26. doi: 10.1038/s41439-022-00203-y

11.

Petrić Howe M Patani R . Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in neuronal physiology and neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci. (2023) 46:879–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2023.07.001

12.

Vuoristo MM Pappas JG Jansen V Ala-Kokko L . A stop codon mutation in COL11A2 induces exon skipping and leads to non-ocular Stickler syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. (2004) 130a:160–4. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30111

13.

Thorpe RK Walls WD Corrigan R Schaefer A Wang K Huygen P et al . AudioGene: refining the natural history of KCNQ4, GSDME, WFS1, and COCH-associated hearing loss. Hum Genet. (2022) 141:877–87. doi: 10.1007/s00439-021-02424-7

14.

Jiang M Qi L Li L Li Y . The caspase-3/GSDME signal pathway as a switch between apoptosis and pyroptosis in cancer. Cell Death Discov. (2020) 6:112. doi: 10.1038/s41420-020-00349-0

15.

Van Laer L Vrijens K Thys S Van Tendeloo VF Smith RJ Van Bockstaele DR et al . DFNA5: hearing impairment exon instead of hearing impairment gene?J Med Genet. (2004) 41:401–6. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.015073

16.

Wang Y Peng J Xie X Zhang Z Li M Yang M . Gasdermin E-mediated programmed cell death: an unpaved path to tumor suppression. J Cancer. (2021) 12:5241–8. doi: 10.7150/jca.48989

17.

Mansard L Vaché C Bianchi J Baudoin C Perthus I Isidor B et al . Identification of the first single GSDME Exon 8 structural variants associated with autosomal dominant hearing loss. Diagnostics. (2022) 12:207. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12010207

18.

Park HJ Cho HJ Baek JI Ben-Yosef T Kwon TJ Griffith AJ et al . Evidence for a founder mutation causing DFNA5 hearing loss in East Asians. J Hum Genet. (2010) 55:59–62. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.114

19.

Yu C Meng X Zhang S Zhao G Hu L Kong X . A 3-nucleotide deletion in the polypyrimidine tract of intron 7 of the DFNA5 gene causes nonsyndromic hearing impairment in a Chinese family. Genomics. (2003) 82:575–9. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00175-

20.

Li D Wang H Wang Q . Splicing mutations of GSDME cause late-onset non-syndromic hearing loss. J Clin Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2024) 38:30–7. doi: 10.13201/j.issn.2096-7993.2024.01.005

21.

Lei P Zhu Q Dong W Zhang S Sun Y Du X et al . Mutation analysis of the GSDME gene in a Chinese family with non-syndromic hearing loss. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0276233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0276233

22.

Bischoff AM Luijendijk MW Huygen PL van Duijnhoven G De Leenheer EMR Oudesluijs GG et al . A novel mutation identified in the DFNA5 gene in a Dutch family: a clinical and genetic evaluation. Audiol Neurotol. (2004) 9:34–46. doi: 10.1159/000074185

23.

Jin Z Cheng J Han B Li H Lu Y Li Z et al . Characteristics of audiology and clinical genetics of a Chinese family with the DFNA5 genetic hearing loss. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi (2011) 25:395–8.

24.

Chai Y Chen D Wang X Wu H Yang T . A novel splice site mutation in DFNA5 causes late-onset progressive non-syndromic hearing loss in a Chinese family. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. (2014) 78:1265–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.05.007

25.

Chen X Jia BL Li MH Lyu Y Liu CX . Case report: novel heterozygous DFNA5 splicing variant responsible for autosomal dominant non-syndromic hearing loss in a chinese family. Front Genet. (2020) 11:569284. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.569284

26.

Cheng J Li T Tan Q Fu J Zhang L Yang L et al . Novel, pathogenic insertion variant of GSDME associates with autosomal dominant hearing loss in a large Chinese pedigree. J Cell Mol Med. (2024) 28:e18004. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.18004

27.

Chen S Dong C Wang Q Zhong Z Qi Y Ke X et al . Targeted next-generation sequencing successfully detects causative genes in chinese patients with hereditary hearing loss. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers (2016) 20:660–5. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2016.0051

28.

Li-Yang MN Shen XF Wei QJ Yao J Lu YJ Cao X et al . IVS8+1 DelG, a novel splice site mutation causing DFNA5 deafness in a Chinese family. Chin Med J (Engl) (2015) 128, 2510–5. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.164980

29.

Bournazos AM Riley LG Bommireddipalli S Ades L Akesson LS Al-Shinnag M et al . (2022). Standardized practices for RNA diagnostics using clinically accessible specimens reclassifies 75% of putative splicing variants. Genet Med.24:130–45. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2021.09.001

Summary

Keywords

DFNA5, GSDME, hereditary hearing loss, phenotype variability, splicing analysis

Citation

Yang B, Zhu M, Long X, Wan S, Lu Y, Yuan H and Hua Q (2026) A novel non-sense variant in GSDME causing exon skipping associated with DFNA5 in a large Chinese family. Front. Neurol. 17:1752843. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2026.1752843

Received

25 November 2025

Revised

10 January 2026

Accepted

14 January 2026

Published

06 February 2026

Volume

17 - 2026

Edited by

Jose Antonio Lopez-Escamez, University of Sydney, Australia

Reviewed by

Wenfu Ma, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, China

Chuan Zhang, Gansu Provincial Maternal and Child Health Hospital, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Yang, Zhu, Long, Wan, Lu, Yuan and Hua.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qingquan Hua, RM001637@whu.edu.cn

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.