Abstract

Objective:

This retrospective single-center study aimed to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and long-term outcomes of the Willis covered stent (WCS) in the treatment of direct carotid-cavernous fistula (dCCF).

Methods:

Between November 2014 and November 2019, 13 patients with dCCF (out of 66 eligible cases) were enrolled and treated with WCS in our institution. Clinical characteristics, procedural details and follow-up data were collected and analyzed.

Results:

Technical success in WCS delivery and deployment was achieved in all 13 patients. No device-related or procedure-related complications were observed. Postoperative angiography demonstrated complete fistula occlusion in 10 patients (76.9%), minimal endoleak in 2 patients (15.4%), and minimal residual leakage in 1 patient (7.7%). Cranial bruit was resolved in all affected patients immediately after the procedure. Proptosis completely resolved in all 13 patients (100%) at the 1-month clinical follow-up (FU). During angiographic FU (mean duration: 9 ± 5.9 months), complete fistula occlusion and parent artery patency were maintained in all 13 patients (100%), with no recurrence of dCCF or in-stent stenosis detected. Long-term clinical FU data were available for 12 patients (92.3%), with a mean duration of 76.8 ± 29.7 months. Ocular symptoms fully resolved in 9 patients (75%), while persistent visual decline was noted in 1 patient (8.3%) and permanent visual loss with mild ptosis was observed in 2 patients (16.7%).

Conclusion:

Our findings demonstrated that WCS was a safe and effective therapeutic option for the treatment of dCCFs, with favorable long-term clinical outcomes. However, additional large-scale studies and prospective randomized controlled trials are warranted to validate these results.

Introduction

Direct carotid-cavernous fistulas (dCCFs) are characterized by a pathological arteriovenous shunt between internal carotid artery (ICA) and cavernous sinus (CS) (1). Based on etiology, dCCFs can be classified into traumatic (80%), spontaneous, and iatrogenic subtypes (2). The most common anatomical locations of dCCFs were reported to be the proximal horizontal portion and posterior bend of the cavernous ICA (3, 4). The shunting blood flow in dCCFs might induce venous hyperperfusion, manifesting as diverse clinical symptoms including proptosis, cranial bruit, diplopia, and visual impairment.

The optimal treatment goal for dCCFs is complete occlusion of the fistulous rent, while preserving ICA patency and minimizing compromise of the CS. Endovascular therapy (EVT) has become the first-line treatment since Serbinenko first treated the dCCF using a detachable balloon in 1974 (5). Compared with other EVT modalities, such as detachable balloons (DBs), coils, liquid embolic agent, or flow diverters (FDs), the Willis covered stent (WCS, MicroPort, Shanghai, China) offers several distinct advantages: (i) immediate fistula occlusion via parent artery reconstruction without intraluminal mass protrusion; (ii) preservation of CS drainage to reduce the risk of cranial nerve palsy; and (iii) simplified, time-efficient procedures that avoid intra-fistulous manipulation (6).

Several retrospective studies have evaluated the safety and efficacy of WCS for dCCF treatment with promising results (7, 8). However, these studies were limited by small sample sizes and a lack of long-term outcome data. Additional evidence regarding clinical outcomes and technical nuances of this EVT modality is needed. Therefore, the present retrospective single-center study aimed to report our experience with WCS for dCCF treatment, with a focus on long-term outcomes.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

A total of 66 patients with dCCFs were identified from the “Database of Cerebrovascular Diseases in Tangdu Hospital” between November 2014 and November 2019. Eligibility for WCS treatment was independently evaluated by two senior interventional neuroradiologists based on angiographic characteristics, including fistula location, parent artery diameter, and vessel tortuosity, with the following criteria: (i) with respect to the carotid siphon, fistula location was proximal to the anterior bend of the cavernous ICA; (ii) maximum parent artery diameter ≤ 4.5 mm; (iii) the size of fistulous rent ≤ 12 mm (considering the maximum available WCS length of 16 mm, with a minimum of 2 mm healthy vessel coverage required on both sides of the lesion); and (iv) posterior bend angle of the cavernous ICA ≥ 90° (9). Alternative EVT strategies, including DBs, coils, liquid embolic agents or FDs, were discussed with all patients and their relatives. Ultimately, 13 patients with dCCFs were enrolled in the study. Clinical data, stent specifications, procedural details, and postoperative/follow-up (FU) results were collected and analyzed.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tandu Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient for the purpose of research.

Segments of the cavernous ICA

The cavernous ICA, which extends from the superior margin of the petrolingual ligament to the proximal dural ring, is divided into four segments along the direction of blood flow: vertical portion, posterior bend, horizontal portion and anterior bend (4). The vertical and horizontal portion are more favorable for covered stent placement than the posterior and anterior bends.

Localization of fistulous rent

Fistula localization might be challenging in high-flow dCCF cases. Therefore, supplementary angiographic evaluations should be performed, including vertebral artery angiography (lateral view) and contralateral carotid artery angiography (anterior–posterior view) with/without ipsilateral carotid compression. Furthermore, three-dimensional (3D) rotational angiography would be practical and effective. The site of fistulous rent could be identified by tracing the ICA wall on multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) images orthogonal to the suspected lesion, where a “broken-rim sign” (discontinuity or indistinctness of the vessel wall) indicated the rent. The size of fistulous rent could be measured on the same MPR views (10).

Endovascular procedures

Endovascular procedures were performed under general anesthesia using a Siemens Artis Zee biplane angiographic system (Siemens, Munich, Germany). Intravenous heparinization was administered to maintain an activated clotting time of 250–300 s.

For non-tortuous vascular pathways, a 6Fr Envoy guiding catheter (Codman, Raynham, MA, USA) was used to deliver the WCS via a 0.014-inch Synchro microguidewire (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA). For tortuous pathways, a coaxial system was employed, consisting of an 8Fr Envoy guiding catheter (Codman, Raynham, MA, USA) or a 6Fr NeuroMax long sheath (Penumbra, Alameda, CA, USA), a 5F or 6F Navien Intracranial Support Catheter (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA), and an XT-27 microcatheter (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA). In this scenario, the Navien catheter was advanced across the fistula, followed by withdrawal of the XT-27 microcatheter. The WCS (housed within the Navien catheter) was positioned at the target site, and then the Navien catheter was slowly withdrawn to expose the stent for deployment. Under roadmap monitoring, the WCS was deployed by inflating the balloon at an appropriate pressure. Immediate post-deployment angiography was performed to assess stent apposition and fistula occlusion.

Endoleak could be inevitably encountered after initial stent deployment owning to the diameter gradients along the covered artery. Therefore, balloon re-inflation (in situ, proximally, or distally) with moderately increased pressure should be performed to eliminate endoleak. Persisted endoleak after several balloon re-inflation (≤ 3 times) should be discriminated and managed based on severity. Minimal endoleak in the middle-to-distal segment of the WCS could be monitored conservatively, while significant endoleak or residual fistulous flow should be promptly addressed with additional WCS deployment or alternative EVT strategies. Postoperative angiography, physical examination, and computed tomography (CT) were routinely performed to rule out procedure related complications.

Antithrombotic management

Preoperatively, patients received dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin (100 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) for 3–5 consecutive days. For patients with clopidogrel resistance, ticagrelor (90 mg, twice, daily) was substituted. Emergency patients received intravenous tirofiban immediately after stent deployment (10 μg/kg bolus within 3 min, followed by 0.15 μg/kg/min maintenance infusion for 48 h), with DAPT initiated 6 h before tirofiban withdrawal. All patients were instructed to continue DAPT for 6 months and aspirin for at least 1 year.

Clinical and angiographic follow-up

Clinical FU was conducted at discharge and 1 month postoperatively. The final clinical FU was performed via telephone interview or outpatient visit. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) or CT angiography (CTA) was recommended for all patients to assess angiographic outcomes.

Results

General characteristics

Thirteen patients, 7 females (53.8%) and 6 males (46.2%), with a mean age of 50.85 ± 10.09 years (range: 25–64 years) were enrolled in our study. The etiology was traumatic (76.9%) and spontaneous (23.1%). The most common ocular symptoms were proptosis (100%), followed by cranial bruit (76.9%), diplopia (38.5%), visual decline (15.4%) and visual loss (15.4%). The sites of fistulous rent were at the vertical portion (61.5%), posterior bend (23.1%) and horizontal portion (15.4%) of the cavernous ICA, respectively. The maximum diameter of the parent artery was 4.24 ± 0.20 mm. The size of fistulous rent was 3.43 ± 0.77 mm. Detailed baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Variables | n or mean ± SD | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 6 | 46.2% |

| Female | 7 | 53.8% |

| Age (years) | 50.85 ± 10.09 | |

| Etiology | ||

| Traumatic | 10 | 76.9% |

| Spontaneous | 3 | 23.1% |

| Ocular symptoms | ||

| Proptosis | 13 | 100% |

| Cranial bruit | 10 | 76.9% |

| Diplopia | 5 | 38.5% |

| Visual decline | 2 | 15.4% |

| Visual loss | 2 | 15.4% |

| Site of fistulous rent | ||

| Vertical portion | 8 | 61.5% |

| Posterior bend | 3 | 23.1% |

| Horizontal portion | 2 | 15.4% |

| Maximum diameter of the parent artery (mm) | 4.24 ± 0.20 | |

| Size of fistulous rent (mm) | 3.43 ± 0.77 | |

Detailed baseline characteristics of the 13 patients with dCCF treated by the WCS.

dCCF, direct carotid-cavernous fistula. WCS, Willis covered stent.

Procedural details and immediate outcomes

Technical success (successful WCS deployment with parent artery preservation) was achieved in all 13 patients (100%). No device-related or procedure-related complications were observed. Postoperative angiography demonstrated complete fistula occlusion in 10 patients (76.9%), minimal endoleak in 2 patients (15.4%), and minimal residual leakage in 1 patient (7.7%).

Immediately after initial WCS deployment, complete occlusion was achieved in 6 patients (46.2%), endoleak was detected in 6 patients (46.2%), and significant distal leakage was noted in 1 patient (7.7%). Balloon re-inflation was performed for all endoleak cases, resulting in complete resolution in 4 patients and persistent minimal endoleak in 2 patients (one in the middle segment and one in the distal segment of the WCS). The patient with significant distal leakage (inadequate stent coverage) underwent rescue embolization with coils and Onyx, with minimal residual leakage remaining postoperatively. All minimal endoleaks and residual leakage were carefully evaluated and deemed acceptable for conservative monitoring and FU. Detailed procedural outcomes were summarized in Tables 2, 3.

Table 2

| Variables | N or mean ± SD | % |

|---|---|---|

| Technical success | 13 | 100% |

| Procedural details | ||

| WCS | 12 | 92.3% |

| Stenting only | 6 | 46.2% |

| Stenting + balloon re-inflation (for endoleak) | 6 | 46.2% |

| WCS + Coils + Onyx | 1 | 7.7% |

| Immediate post-operative result | ||

| Complete occlusion | 10 | 76.9% |

| Minimal endoleak | 2 | 15.4% |

| Middle section of WCS | 1 | 7.7% |

| Distal section of WCS | 1 | 7.7% |

| Minimal residual leakage | 1 | 7.7% |

| Procedural complications | 0 | 0 |

| Angiographic follow-up | ||

| Patients | 13 | 100% |

| Months | 9.00 ± 5.87 | |

| Complete occlusion | 13 | 100% |

| Parent artery patency | 13 | 100% |

| 1-month clinical follow-up | ||

| Patients | 13 | 100% |

| No symptom | 8 | 61.5% |

| Mild Diplopia | 1 | 7.7% |

| Visual decline | 2 | 15.4% |

| Visual loss with moderate ptosis | 2 | 15.4% |

| Last clinical follow-up | ||

| Patients | 12 | 92.3% |

| Months | 76.80 ± 29.72 | |

| No symptom | 9 | 75% |

| Visual decline | 1 | 8.3% |

| Visual loss with mild ptosis | 2 | 16.7% |

Operative and follow-up results of the 13 patients with dCCF treated by the WCS.

dCCF, direct carotid-cavernous fistula. WCS, Willis covered stent.

Table 3

| No | Sex | Age | Etiology | Ocular symptoms | Site of fistula | Stent size | Procedure details | Post-op outcome | Angiographic FU | 1-month clinical FU | Last clinical FU | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | Results | Duration | Results | ||||||||||

| 1 | M | 25 | Traumatic | Proptosis, visual loss | Vertical portion | 4.0 × 16 mm | Stenting only | Complete occlusion | 7 months | Complete occlusion | Moderate ptosis, Visual loss | 132 months | Mild ptosis, Visual loss |

| 2 | F | 58 | Traumatic | Proptosis, visual decline | Vertical portion | 4.5 × 16 mm | proximal and distal balloon re-inflation | Complete occlusion | 6 months | Complete occlusion | visual decline | 112 months | No symptom |

| 3 | F | 54 | Spontaneous | Proptosis, bruit | Vertical portion | 4.5 × 13 mm | Proximal balloon re-inflation | Complete occlusion | 6 months | Complete occlusion | No symptom | 109 months | No symptom |

| 4 | F | 57 | Traumatic | Proptosis, bruit, diplopia | Vertical portion | 4.5 × 16 mm | Proximal and distal balloon re-inflation | Minimal endoleak* | 8 months | Complete occlusion | No symptom | 96 months | No symptom |

| 5 | M | 60 | Traumatic | Proptosis, bruit, diplopia | Horizontal portion | 4.5 × 13 mm | In situ balloon re-inflation | Complete occlusion | 6 months | Complete occlusion | No symptom | 85 months | No symptom |

| 6 | M | 64 | Traumatic | Proptosis, bruit, diplopia | Posterior bend | 4.5 × 13 mm | Stenting only | Complete occlusion | 15 months | Complete occlusion | No symptom | 77 months | No symptom |

| 7 | F | 50 | Spontaneous | Proptosis, visual loss | Posterior bend | 4.5 × 16 mm | In situ balloon re-inflation | Minimal endoleak* | 2 months | Complete occlusion | Moderate ptosis, Visual loss | 64 months | Mild ptosis, Visual loss |

| 8 | F | 46 | Traumatic | Proptosis, bruit | Horizontal portion | 4.5 × 13 mm | In situ balloon re-inflation | Complete occlusion | 10 months | Complete occlusion | No symptom | NA | NA |

| 9 | M | 50 | Traumatic | Proptosis, bruit, diplopia | Vertical portion | 4.5 × 13 mm | Stenting only | Complete occlusion | 12 months | Complete occlusion | No symptom | 55 months | No symptom |

| 10 | M | 58 | Traumatic | Proptosis, bruit, visual decline | Vertical portion | 4.5 × 13 mm | Stenting only | Complete occlusion | 6 months | Complete occlusion | Visual decline | 49 months | Visual decline |

| 11 | M | 41 | Traumatic | Proptosis, bruit | Vertical portion | 4.5 × 13 mm | Stenting only | Complete occlusion | 5 months | Complete occlusion | No symptom | 48 months | No symptom |

| 12 | F | 52 | Spontaneous | Proptosis, bruit, diplopia | Vertical portion | 4.5 × 10 mm | Distal endoleak Coils + Onyx | Minimal leakage | 25 months | Complete occlusion | Mild diplopia | 48 months | No symptom |

| 13 | F | 46 | Traumatic | Proptosis, bruit | Posterior bend | 4.5 × 16 mm | Stenting only | Complete occlusion | 9 months | Complete occlusion | No symptom | 47 months | No symptom |

Clinical data, stent size, procedure and follow-up details of the 13 patients with dCCF treated by the WCS.

dCCF, direct carotid-cavernous fistula. F, female; FU, follow-up; M, male. NA, not applicable. WCS, Willis covered stent. *Middle segment of the stent, distal segment of the stent.

Angiographic follow-up results

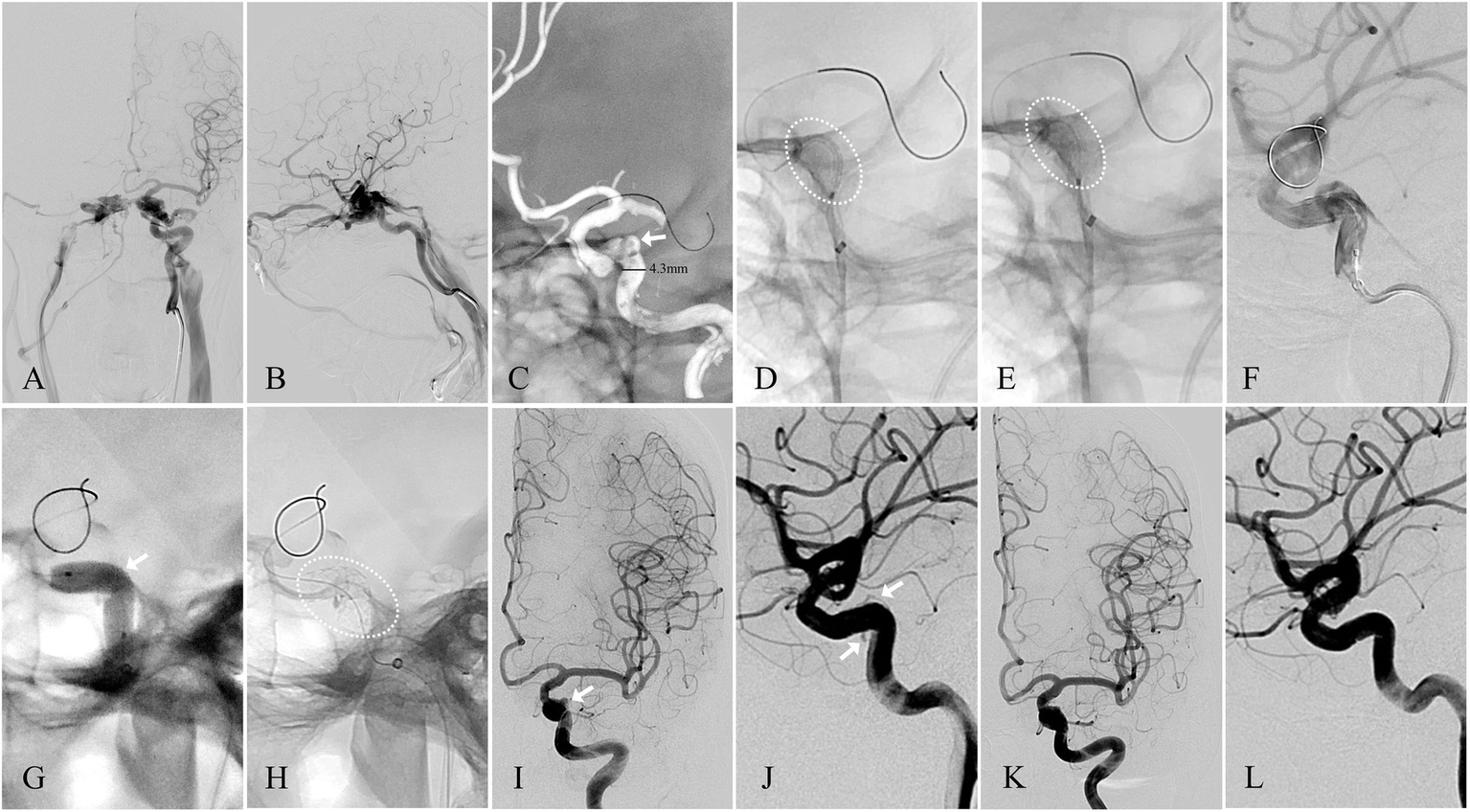

Angiographic FU data were available for all 13 patients with a mean duration of 9.00 ± 5.87 months (range: 2–25 months). Complete fistula occlusion and parent artery patency were maintained in all patients (100%), with no recurrence of dCCF or in-stent stenosis detected. Neointimal hyperplasia was observed in 1 patient at the 15-month FU (Figure 1). Notably, the 2 cases of minimal endoleak and 1 case of residual leakage resolved spontaneously during FU: the endoleak in the middle segment of the stent resolved at 8 months (patient No. 4), the endoleak in the distal segment of the stent resolved at 2 months (patient No. 7, Figure 2), and the residual leakage (after coil/Onyx rescue embolization) resolved at 25 months (patient No. 12).

Figure 1

Angiographic images of a 64-year-old man with a right traumatic dCCF (see Patient No. 6 in Table 3). (A) A-P view and (B) Lateral view of a right-sided traumatic dCCF and the diameter of the parent artery (straight line). (C) The site (arrowhead) and size (straight line) of the fistulous rent was identified at the posterior bend of the cavernous ICA in multiplanar reconstructions (MPR) imaging orthogonal to the rent. (D) The WCS (dotted oval) 4.5 × 13 mm was delivered in position to cover the fistula. (E) The WCS (dotted oval) was deployed after initial balloon inflation. (F) A-P view and (G) lateral view of the complete occlusion of the dCCF and the preservation of the parent artery. (H) A-P view and (I) lateral view of the complete occlusion of the dCCF at the 15-month angiographic FU. (J) The neointimal hyperplasia (arrowhead) within the WCS.

Figure 2

Angiographic images of a 50-year-old woman with a left-sided spontaneous dCCF (see Patient No. 7 in Table 3). (A) A-P view and (B) Lateral view of a left-sided traumatic dCCF. (C) The site of the fistulous rent (arrowhead) was identified at the posterior bend of the cavernous ICA by 3D reconstruction, the microguidewire was navigated by 3D roadmap, and the diameter of the parent artery (straight line) was measured. (D) The WCS (dotted oval) 4.5 × 16 mm was delivered in position to cover the fistula. (E) The WCS (dotted oval) was deployed after initial balloon inflation. (F) Endoleak persisted after initial balloon inflation. (G) Balloon re-inflation with an appropriately increased pressure. (H) The WC’S after balloon re-inflation. (I) A-P view and (J) lateral view of the minimal endoleak (arrowhead) at the distal section of the WCS. (K) A-P view and (L) lateral view of the complete elimination of the endoleak at the 2-month angiographic FU.

Clinical follow-up results

Cranial bruit resolved immediately after procedure in all affected patients, and all ocular symptoms except visual impairment improved gradually by discharge. At the 1-month FU, proptosis had completely resolved in all 13 patients (100%), and other ocular symptoms had fully recovered in 8 patients (61.5%). Mild diplopia persisted in 1 patient (7.7%) who had undergone coil/Onyx rescue embolization. Visual decline in 2 patients (15.4%) and visual loss in 2 patients (15.4%) showed no improvement, with moderate ptosis observed in the 2 patients with visual loss.

Long-term clinical FU data were available for 12 patients with a mean duration of 76.80 ± 29.72 months (range: 47–132 months). No strokes or new neurological deficits occurred during FU. Ocular symptoms had fully resolved in 9 patients (75%), while persistent visual decline was noted in 1 patient (8.3%) and permanent visual loss with mild ptosis persisted in 2 patients (16.7%).

Discussion

WCS and other EVT modality

EVT has become the cornerstone of dCCF management, driven by technological progress and material innovations in neurointervention. Although DBs pioneered dCCF treatment in 1974, their utilization has declined in many centers due to availability constraints. A 2023 meta-analysis reported that coils are the most commonly used EVT modality for dCCF (69.3%), followed by Onyx (31.1%), covered stents (22.2%), N-butyl cyanoacrylate (6.7%), and FDs (4.8%) (11). The pooled overall complete occlusion rate was 92.1%. Specifically, the initial occlusion rate was 77.7%, which increased to a final occlusion rate of 93.1%. The pooled symptom improvement rate was 89.4% and the recurrence rate was 8.3%. The pooled complication rate was 10.9%. Specifically, the most common major complication was cranial nerve palsy (3.3%), followed by intracranial hemorrhage (0.5%).

In our study, the initial complete occlusion rate of 76.9% increased to 100% at FU. No procedural/delayed complications or fistula recurrence was observed. The favorable outcomes were attributed to strict patient selection, optimal stent apposition, and proactive management of endoleak/residual leakage. Notably, visual loss (likely secondary to primary optic nerve injury) was irreversible even after successful fistula occlusion, whereas visual decline showed potential for reversal with timely intervention. These findings aligned with previous reports indicating that pre-existing optic nerve damage was a major determinant of irreversible visual impairment in dCCF.

Advantages of WCS

The WCS is a balloon-expandable endoprosthesis consisting of a bare stent and an expandable polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane, specially designed for use in the tortuous intracranial vasculature (6). Over the past decade, our team has validated its utility as a simplified, effective, and time-efficient treatment for various cranial vascular lesions (12–15). The WCS seemed to be an ideal therapeutic option for two key advantages: (i) immediate parent artery reconstruction without intraluminal mass protrusion, which avoids the risk of vessel occlusion or stenosis; and (ii) preservation of normal CS blood flow and cranial nerve function, as intra-fistulous manipulation is unnecessary, thus reducing the risk of cranial nerve palsy, a common complication of coil or liquid embolic agent use.

Fistulous rent identification

Accurate identification of the fistulous rent is critical for successful dCCF treatment, particularly in high-flow cases. Supplementary angiographic evaluations (vertebral artery and contralateral carotid artery angiography) and 3D rotational angiography facilitated precise fistulous rent identification. As demonstrated in our study, vertebral artery angiography not only aided in fistulous rent identification, but also supported microcatheter navigation and intraoperative monitoring (Figure 3). 3D roadmap imaging was additionally valuable for differentiating dCCF from other lesions, such as ruptured cavernous ICA aneurysms, as illustrated in one of our spontaneous cases (Figure 2). Furthermore, the “broken-rim sign” on MPR imaging orthogonal to the fistula provided a practical and reliable method for localizing and measuring the fistulous rent. Which was essential for optimal stent size selection (Figure 1).

Figure 3

Angiographic images of a 50-year-old man with a right traumatic dCCF (see Patient No. 9 in Table 3). (A) A-P view and (B) Lateral view of a right-sided traumatic dCCF and the diameter of the parent artery (straight line). (C) A-P view of the collateral compensation from the contralateral ICA (D) The site of the fistulous rent (arrowhead) was identified at the vertical segment of the cavernous ICA by the vertebral angiography. (E) The WCS (dotted oval) 4.5 × 13 mm was delivered in position to cover the fistula. (F) The position of the WCS (dotted oval) was reconfirmed by the vertebral angiography. (G) Initial balloon inflation (dotted oval) (H) The WCS (dotted oval) was deployed. (I) lateral view and (J) A-P view of the complete occlusion of the dCCF and the preservation of the parent artery. (I) A-P view and (L) lateral view of the 12-month angiographic FU.

Technical pearls for WCS delivery and apposition

Despite its intracranial design, successful WCS delivery and apposition in tortuous arteries remain challenges. Fistulous rent location and parent artery tortuosity are major determinants for technical success. First, fistulous rent location impacts stent apposition: dCCFs in straight vascular segments (vertical and horizontal portion of the cavernous ICA, which accounted for 76.9% of cases in our study) are more suitable for WCS placement and apposition than those in curved vascular segments (anterior and posterior bend of the cavernous ICA). In our experience, dCCFs in the posterior bend of the cavernous ICA were eligible only if the bend angle is obtuse (≥ 90°), as seen in 3 enrolled patients (23.1%); acute-angled bend (< 90°) was not recommended due to the risk of inadequate stent apposition and subsequent endoleak. Second, parent artery tortuosity is a major barrier to WCS delivery, which can be overcome with the use of intracranial support catheters. A critical technical pearl is to advance the WCS beyond the fistula within the intracranial support catheter to prevent unintended stent migration during deployment, which significantly improved technical success in our series (16–18).

Endoleak management

Endoleak is defined as persistent perfusion of the space between the covered stent and parent vessel wall (19). Stent size selection is paramount for minimizing endoleak risk. When in doubt, our experience is to choose a WCS that is larger in diameter to ensure stent apposition and longer in length to secure adequate coverage, owing to the absence of vital branches or perforating arteries in the cavernous ICA (18). Nevertheless, endoleak occurred in 6 patients (46.2%) after initial WCS deployment in our study, attributable to two main factors: (i) insufficient initial balloon inflation (due to over-caution to avoid arterial dissection or rupture, considering the diameter gradients along the covered vessel), which could be resolved by balloon re-inflation with moderately increased pressure; and (ii) inadequate stent apposition on the concave side of curved vessels (an inevitable limitation associated with the rigid structural properties of the covered stents).

For endoleaks caused by insufficient initial balloon inflation (n = 5), balloon re-inflation with moderately increased pressure resulted in complete resolution in 4 patients and alleviation to minimal endoleak in 1 patient (Figure 2). For the endoleak (n = 1) attributed to inadequate concave apposition, alleviation was achieved but minimal endoleak persisted despite of multiple balloon re-inflations. These two cases of persistent minimal endoleak were consistent with previous reports indicating favorable outcomes for minimal endoleak, particularly in the middle-to-distal stent segments (7, 11, 20, 21).

In contrast, significant distal leakage (distinct from endoleak) secondary to inadequate stent coverage, resulting from incorrect fistulous rent measurement and undersized stent selection, required urgent remedial EVT strategies. In this case, rescue embolization with coils and Onyx was successfully performed.

Limitations

This study had several notable limitations. First, it was a single-center retrospective study with a small sample size (n = 13), which restricted the statistical power of our analyses and limited the generalizability of the findings. Second, the retrospective design inherently introduced selection bias: enrollment criteria were subjectively evaluated by two senior interventional neuroradiologists, and EVT modality decisions were made jointly with patients and their relatives based on clinical preferences and shared decision making. Third, long-term angiographic FU data were limited (mean duration: 9.00 ± 5.87 months), precluding comprehensive assessment of long-term vascular outcomes such as neointimal hyperplasia and in-stent stenosis. Fourth, the absence of a control group (patients treated with other EVT modalities such as coils or FDs) prevented direct comparison of the WCS with alternative treatments for dCCFs.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrated that the WCS was a safe and effective therapeutic option for the treatment of dCCFs, with favorable long-term clinical outcomes. Strict patient selection, precise fistulous rent localization, optimal stent apposition, and proactive endoleak management were critical for achieving these outcomes. Nevertheless, given the study limitations, additional large-scale prospective studies and randomized controlled trials are warranted to validate the efficacy and safety of the WCS for dCCFs.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Tandu Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

TZ: Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation. HC: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. YL: Software, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. WF: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. GL: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. XG: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. HJ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. ZY: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. YS: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. ZZ: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. JD: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the Clinical Research Funding Program, Air Force Medical University (Grant No. 2022LC2225).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

3D, three dimensional; A-P view, anterior–posterior view; CS, cavernous sinus; CT, computed tomography; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; DBs, detachable balloons; dCCFs, direct carotid-cavernous fistulas; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; EVT, endovascular therapy; FDs, flow diverters; FU, follow-up; ICA, internal carotid artery; MPR, multiplanar reconstructions; WCS, Willis covered stent.

References

1.

Barrow DL Spector RH Braun IF Landman JA Tindall SC Tindall GT . Classification and treatment of spontaneous carotid-cavernous sinus fistulas. J Neurosurg. (1985) 62:248–56. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.2.0248,

2.

Ringer AJ Salud L Tomsick TA . Carotid cavernous fistulas: anatomy, classification, and treatment. Neurosurg Clin N Am. (2005) 16:279–95, viii, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2004.08.004,

3.

Debrun G Lacour P Vinuela F Fox A Drake CG Caron JP . Treatment of 54 traumatic carotid-cavernous fistulas. J Neurosurg. (1981) 55:678–92. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.55.5.0678,

4.

Bouthillier A van Loveren HR Keller JT . Segments of the internal carotid artery: a new classification. Neurosurgery. (1996) 38:425–32. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199603000-00001,

5.

Serbinenko FA . Balloon catheterization and occlusion of major cerebral vessels. J Neurosurg. (1974) 41:125–45. doi: 10.3171/jns.1974.41.2.0125

6.

Li MH Gao BL Wang YL Fang C Li YD . Management of pseudoaneurysms in the intracranial segment of the internal carotid artery with covered stents specially designed for use in the intracranial vasculature: technical notes. Neuroradiology. (2006) 48:841–6. doi: 10.1007/s00234-006-0127-7,

7.

Liu LX Lim J Zhang CW Lin S Wu C Wang T et al . Application of the Willis covered stent in the treatment of carotid-cavernous fistula: a single-center experience. World Neurosurg. (2019) 122:e390–8. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.10.060,

8.

Liu Q Qi C Wang Y Su W Li G Wang D . Treatment of direct carotid-cavernous fistula with Willis covered stent with midterm follow-up. Chin Neurosurg J. (2021) 7:41. doi: 10.1186/s41016-021-00256-y,

9.

Chen Z Fan T Zhao X Hu T Qi H Li D . Simplified classification of cavernous internal carotid artery tortuosity: a predictor of procedural complexity and clinical outcomes in mechanical thrombectomy. Neurol Res. (2022) 44:918–26. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2022.2068851,

10.

Sharma DP Kannath SK Singh G Rajan JE . Shunt site localization of direct carotid-cavernous fistula using 3d rotational angiography—utility of broken-rim sign. World Neurosurg. (2020) 144:e376–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.08.167,

11.

Yuan J Yang R Zhang J Liu H Ye Z Chao Q . Covered stent treatment for direct carotid-cavernous fistulas: a meta-analysis of efficacy and safety outcomes. World Neurosurg. (2024) 187:e302–12. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2024.04.077

12.

Zhang T Deng J Chen H Liu Y Wang F Li S et al . Treatment of cranial-cervical aneurysms with stent-graft: 20 cases report with short-term follow-up. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. (2016) 54:346–51. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5815.2016.05.006

13.

Fang W Yu J Liu Y Sun P Yang Z Zhao Z et al . Application of the Willis covered stent in the treatment of blood blister-like aneurysms: a single-center experience. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:882880. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.882880,

14.

Lu D Ma T Zhu G Zhang T Wang N Lei H et al . Willis covered stent for treating intracranial pseudoaneurysms of the internal carotid artery: a multi-institutional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2022) 18:125–35. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S345163,

15.

Wu Y Yu J Zhang T Deng JP Zhao Z . Endovascular treatment of distal internal carotid artery aneurysms and vertebral artery dissecting aneurysms with the Willis covered stent: a single-center, retrospective study. Interv Neuroradiol. (2023) 29:63–78. doi: 10.1177/15910199211070900,

16.

Zeng S Yang H Yang D Xu L Xu M Wang H . Case report of late type IIIb endoleak with Willis covered stent (WCS) and literature review. World Neurosurg. (2019) 130:160–4. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.06.105,

17.

Ma L Feng H Yan S Xu JC Tan HQ Fang C . Endovascular treatment of complex vascular diseases of the internal carotid artery using the Willis covered stent: preliminary experience and technical considerations. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:554988. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.554988,

18.

Tong X Xue X Feng X Jiang Z Duan C Liu A . Impact of stent size selection and vessel evaluation on skull base cerebrovascular diseases treated with Willis covered stents: a multicenter retrospective analysis. J Endovasc Ther. (2024) 32:15266028241241193. doi: 10.1177/15266028241241193,

19.

Tan HQ Li MH Li YD Fang C Wang JB Wang W et al . Endovascular reconstruction with the Willis covered stent for the treatment of large or giant intracranial aneurysms. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2011) 31:154–62. doi: 10.1159/000321735,

20.

Wang YL Ma J Li YD Ding PX Han XW Wu G . Application of the Willis covered stent for the Management of Posttraumatic Carotid-Cavernous Fistulas: an initial clinical study. Neurol India. (2012) 60:180–4. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.96397,

21.

Ma L Yan S Feng H Xu J Tan H Fang C . Endoleak management and postoperative surveillance following endovascular repair of internal carotid artery vascular diseases using Willis covered stent. J Interv Med. (2021) 4:212–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jimed.2021.09.001,

Summary

Keywords

direct carotid-cavernous fistula, endovascular therapy, long-term outcome, retrospective study, Willis covered stent

Citation

Zhang T, Chen H, Liu Y, Fang W, Luo G, Guo X, Jiang H, Yang Z, Si Y, Zhao Z and Deng J (2026) Long-term outcome of Willis covered stent for direct carotid-cavernous fistula. Front. Neurol. 17:1753105. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2026.1753105

Received

24 November 2025

Revised

02 January 2026

Accepted

12 January 2026

Published

22 January 2026

Volume

17 - 2026

Edited by

Tianxiao Li, Henan Provincial People's Hospital, China

Reviewed by

Li Pan, Wuhan People's Liberation Army General Hospital, China

Zhifeng Wen, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Zhang, Chen, Liu, Fang, Luo, Guo, Jiang, Yang, Si, Zhao and Deng.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tao Zhang, Baltimore@163.com; Zhenwei Zhao, zzwzc@sina.com; Jianping Deng, 13991139395@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.