- Department of Psychosocial Science, University of Bergen, Norway

Introduction: Sexual and gender minorities (SGMs) are more often targets of negative interpersonal behaviors at work and as a result report worse health than their cisgender and heterosexual coworkers. We argue that by engaging in acts of allyship—such as defending and empowering SGMs—employees can contribute to better the health of SGMs in the workplace. Specifically, we hypothesized that there are negative associations between observing and experiencing interpersonal discrimination and self-rated health, and that these can be moderated by experiencing and observing SGM allyship.

Methods: We tested these hypotheses in a large sample of Norwegian SGMs (N = 438) originally recruited for the Sexual Orientation, Gender Diversity, and Living Conditions Study.

Results: Both experiencing (r = −0.15, p < 0.001) and observing interpersonal discrimination (r = −0.21, p < 0.001) were significantly related to poorer self-rated health. As expected, regression analyses showed that experiencing allyship moderated the association between experiencing interpersonal discrimination and self-rated health (b = 0.26, p = 0.046, 95% CI [0.004, 0.520]). Experiencing allyship also moderated the negative effect of observing interpersonal discrimination on self-rated health (b = 0.21, p = 0.028, 95% CI [0.023, 0.391]). The difference in self-rated health between individuals who had experienced or observed interpersonal discrimination and those who had not was substantially reduced at higher levels of experienced allyship. Contrary to our hypotheses, observing allyship was not a significant moderator.

Discussion: The findings extend previous research on the benefits of allyship for SGM employees and have implications for the promotion of SGMs' wellbeing at work.

1 Introduction

Compared to their heterosexual and cisgender peers, sexual and gender minority (SGM) employees more commonly experience interpersonal mistreatment at work, such as incivility (Zurbrügg and Miner, 2016), microaggressions (Jones et al., 2017), ostracism (DeSouza et al., 2017), bullying (Hoel et al., 2014), sexual harassment (Bye and Bjørkelo, 2024), and discrimination and harassment (McFadden, 2015). Exposure to such negative interpersonal behaviors is negatively associated with both mental and physical health outcomes (Waldo, 1999; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013; Hoel et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2016, 2017; Russell and Fish, 2016; English et al., 2018; Scandurra et al., 2018; Valentine and Shipherd, 2018; Christian et al., 2021; Lattanner et al., 2022; Smith and Griffiths, 2022; Puckett et al., 2023; Lacatena et al., 2024; Oliveira et al., 2024). This is consistent with the theory of minority stress, which outlines how experiences of discrimination, prejudice, and stigma mount over time to corrode physical and mental health (Meyer, 2003; Frost and Meyer, 2023). Importantly, both personally experiencing and observing the mistreatment of others can impact health negatively (Waldo, 1999; Hoel et al., 2014; Woodford et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2016, 2017; English et al., 2018; Miner and Costa, 2018; Scandurra et al., 2018; Valentine and Shipherd, 2018; Christian et al., 2021; Lattanner et al., 2022; Puckett et al., 2023).

However, some SGMs may face or observe interpersonal mistreatment without experiencing negative health symptoms (Witten, 2013; Meyer, 2015; De Lira and de Morais, 2018). Resilience factors, such as social support (Cobb, 1976; Sarason et al., 1983; Wilks, 2008; Sloan, 2012; Bockting et al., 2016), may hinder negative health effects (Schwarzer and Leppin, 1991; Geldart et al., 2018). But different forms of social support are not necessarily equally effective (Schilling, 1987; Schwarzer and Leppin, 1991; Viswesvaran et al., 1999; Taylor, 2011; Jolly et al., 2021). Well-intentioned, supportive acts, such as listening to and validating the target's frustration, can be insufficient (Collier-Spruel and Ryan, 2022). Rather, Selvanathan et al. (2020) argue that minority members favor allyship in the form of actions to confront negative interpersonal behaviors over emotional support.

At work, SGM allies could be especially valuable (Brooks and Edwards, 2009; Webster et al., 2017; Hebl et al., 2020; Thoroughgood et al., 2021). Thoroughgood et al. (2021) argue that advantaged group members who publicly challenge workplace inequality, unfairness, disrespect, and harm, signal to minorities that they are valued, more so than through private forms of social support. Consistent with this line of reasoning, previous research demonstrates that allies in the workplace contribute to SGM's wellbeing (Perales, 2022; Deloitte Global, 2023), relationships with colleagues (Perales, 2022; Chen et al., 2023), job satisfaction, and organizational commitment (Thoroughgood et al., 2021). Whether personally experiencing and observing allyship can ameliorate the negative health effects of interpersonal discrimination remains empirically unexplored.

In this study, we extend previous work by investigating whether allyship can buffer the negative impact of discrimination on self-rated health both for targets and observers of interpersonal discrimination directed at SGMs. Empirically, we draw on the Sexual Orientation, Gender Diversity and Living Conditions Study (Anderssen et al., 2021) which provides rare and high-quality data on the work experiences and health of Norwegian SGMs.

1.1 Perceived interpersonal discrimination and health

Despite legislation that prohibits discrimination and harassment based on sexual orientation and gender identity in the workplace (e.g., Equality Anti-Discrimination, 2017, §§6–8), SGMs can face both blatant and more subtle expressions of prejudice (Einarsdóttir et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2016, 2017; Malterud and Bjorkman, 2016; DeSouza et al., 2017; Synnes and Malterud, 2019; Di Marco et al., 2021; Deloitte Global, 2023). We focus on interpersonal discrimination, which is defined as “verbal, non-verbal and paraverbal behaviors that demonstrate biased behaviors toward specific groups” (Hebl et al., 2020, p. 259). Interpersonal discrimination at work can take many forms, for example, tasteless jokes at the expense of SGMs (Waldo, 1999; Di Marco et al., 2018, 2021; Deloitte Global, 2023), increased curtness (Zurbrügg and Miner, 2016), or a changed tone, pitch, or pacing (e.g., sarcasm, fake interest, speaking faster or slower than usual) when speaking to SGMs (Hebl et al., 2002). Although interpersonal discrimination is often—but not always—subtle, both targets and observers are able to perceive its negativity (Hebl et al., 2002). However, whether, and to what extent, ambiguous negative interpersonal behaviors are attributed to SGM status may vary among SGMs, both when observing others being targets and when being targets themselves. In this study, we specifically address perceived interpersonal discrimination by including the respondents' perceptions that the negative interpersonal comments or behaviors they have experienced or observed are due to their own, or the observed target's SGM status.

As already discussed, experiencing interpersonal discrimination can have harmful effects on physical and mental health among SGM targets (Waldo, 1999; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013; Hoel et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2016, 2017; Russell and Fish, 2016; English et al., 2018; Scandurra et al., 2018; Valentine and Shipherd, 2018; Christian et al., 2021; Peterson et al., 2021; Lattanner et al., 2022; Smith and Griffiths, 2022; Puckett et al., 2023; Lacatena et al., 2024). Similarly, SGMs who observe interpersonal discrimination toward other SGMs can also experience negative health symptoms (Woodford et al., 2014; Miner and Costa, 2018; Peterson et al., 2021). In line with minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003; Frost and Meyer, 2023) and the interpersonal discrimination literature, we hypothesize that both being a target and being a witness to interpersonal discrimination are negatively correlated with self-rated health among SGMs.

Hypothesis 1. Experiencing interpersonal discrimination in the workplace is negatively associated with self-rated health among SGMs.

Hypothesis 2. Observing interpersonal discrimination toward other SGMs in the workplace is negatively associated with self-rated health.

1.2 Allyship as a source of resilience against interpersonal discrimination

Allies are defined as persons from advantaged groups who are “engaging in committed action to improve the treatment and status of a disadvantaged group” (Louis et al., 2019, p. 6). Allyship in the workplace may take the form of defending and empowering SGMs and contesting biased treatment (Brooks and Edwards, 2009; Thoroughgood et al., 2021; Collier-Spruel and Ryan, 2022; Chen et al., 2023; De Souza and Schmader, 2024). Here allyship shares some similarities with social support. Defending and empowering others can involve providing both instrumental support (e.g., sharing information and practical help) as well as emotional or reappraisal support (e.g., consoling the target, giving the target new perspectives on adverse events; Cobb, 1976; for a review of social support, see Jolly et al., 2021). However, allies also acknowledge the systemic oppression SGMs face and are driven to dismantle discriminatory social structures rather than take advantage of them (Louis et al., 2019; Selvanathan et al., 2020; De Souza and Schmader, 2024). Acts of allyship include defending or protecting SGMs by contesting biased treatment when it is appropriate to do so, for instance by shaking one's head at or challenging derogatory comments, and supporting coworkers, such as reaffirming SGM coworkers' voice when they are overheard or publicly attributing their ideas back to them (Collier-Spruel and Ryan, 2022; De Souza and Schmader, 2024).

We propose that both personally experiencing and observing acts of allyship toward other SGMs moderate the negative effects of experiencing and observing interpersonal discrimination. Acts of allyship signal to SGMs that they are highly valued (Thoroughgood et al., 2021), increase SGMs' wellbeing (Perales, 2022; Deloitte Global, 2023), and improve relationships with the ally (Perales, 2022; Chen et al., 2023). Additionally, as interpersonal discrimination can often be written off as a joke or misunderstanding (Einarsdóttir et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2016, 2017; Zurbrügg and Miner, 2016; DeSouza et al., 2017), successful acts of allyship validate SGMs' experiences of discrimination (Collier-Spruel and Ryan, 2022; De Souza and Schmader, 2024), which may reduce the stress associated with these often-ambiguous situations (Webster et al., 2017; Hebl et al., 2020; Thoroughgood et al., 2021).

SGMs can also benefit from observing acts of allyship toward other SGM in the workplace or from majority colleagues advocating for LGBT+ rights. For example, if a debate about SGM rights arises in the workplace, allyship may take the form of majority members supporting LGBT+ rights. Such acts of allyship may affect the workplace culture (Rasinski and Czopp, 2010; Drury and Kaiser, 2014), creating a safer work environment for stigmatized individuals (Webster et al., 2017). Indeed, observing allies contest biased treatment toward others improved perceptions of workplace safety among individuals from racial minority groups and women (Hildebrand et al., 2020). Additionally, when successfully confronted by allies, perpetrators tend to inhibit their prejudiced comments or behavior (Chaney and Sanchez, 2018; De Souza and Schmader, 2024), reducing the frequency of interpersonal discrimination in the workplace (Chaney et al., 2021).

A review and meta-analysis of factors that support LGBT employees at work (Webster et al., 2017), showed that supportive relationships with colleagues were associated with lower levels of psychological strain (e.g., depression, anxiety, and exhaustion). We focus on global self-rated health as a broader measure of health reflecting both psychological and somatic aspects of health (Idler and Benyamini, 1997; Kaplan et al., 2007; Benyamini, 2011; Lorem et al., 2017, 2020), and propose that experiencing and observing acts of allyship in the workplace buffer the negative association between interpersonal discrimination and self-rated health among SGM workers.

Hypothesis 3. The negative effect of experiencing interpersonal discrimination in the workplace on self-rated health is moderated by both experiencing and observing SGM allyship.

Hypothesis 4. The negative effect of observing interpersonal discrimination in the workplace on self-rated health is moderated by both experiencing and observing SGM allyship.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and procedure

We draw on data from the fourth nationwide study of Sexual Orientation, Gender Diversity, and Living Conditions (Anderssen et al., 2021). This is a large survey about SGM and heterosexual cisgendered Norwegians' background, life satisfaction, social networks, physical and mental health, socioeconomic status, experiences of discrimination and violence, and openness and concealment. The survey also contains a series of questions about interpersonal discrimination and allyship at work, which we draw on in the present study. Data is stored at the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (Anderssen et al., 2024) and is available for research purposes.

The data collection was conducted by Opinion AS between April 4th and June 15th, 2020. The questionnaire was sent to 110,000 web panel participants. Participants in Opinion's web panels have been recruited from the Norwegian population registry to be representative of the Norwegian population and have consented to receive e-mails inviting them to participate in various surveys. Because the project's main aim was to survey living conditions among sexual- and gender-minority individuals, an oversampling method was used to achieve a sufficient number of participants who indicated belonging to a sexual- and/or gender-minority group. For comparisons, heterosexual and cisgender participants were also recruited.

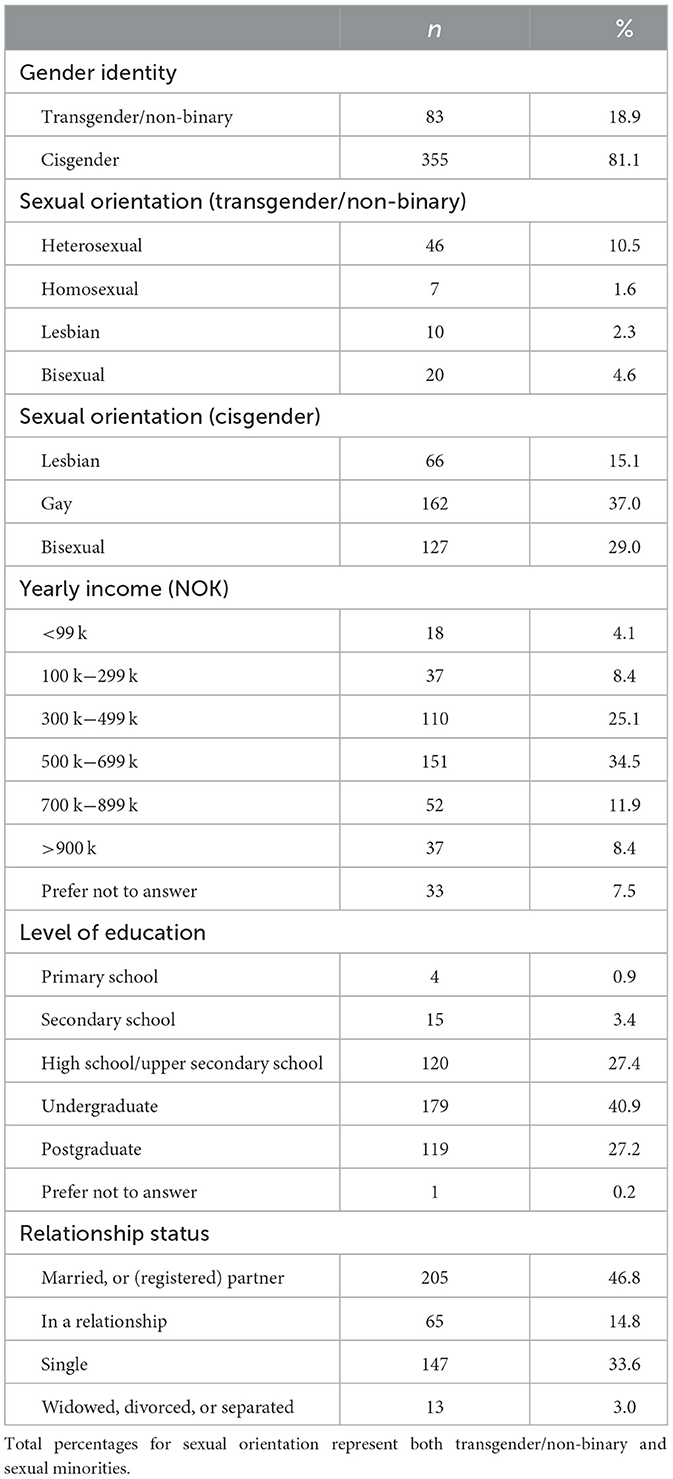

The total sample from the data collection was 2,059 participants. The current study focused on a subset of 630 employed participants who identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual, binary transgender, or non-binary. As detailed in the description of the measures, many survey questions provided the participants with the response options “not relevant” or “prefer not to answer”. We excluded a total of 192 participants who chose these response options for the items included in the main analyses. In the analyzed sample (N = 438), 83 participants identified as transgender or non-binary, of whom 47 identified as binary transgender (34,0% women) and 36 as non-binary. Of the 83 transgender and non-binary participants, 46 reported being heterosexual, 20 were bisexual, 10 were lesbian, and seven were homosexual. Among the cisgender respondents (n = 355; 41.4% women), 162 identified as homosexual, 66 as lesbian, and 127 as bisexual. The sample was diverse in age (M = 38.96, SD = 11.96), ranging from 18 to 71 years old. Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Experienced interpersonal discrimination

Experiences of interpersonal discrimination were measured with two questions. The first one was “Have you at your workplace, the last 5 years, experienced negative comments or behaviors because you are lesbian/homosexual/bisexual?”. The second was “Have you at your workplace, the last 5 years, experienced negative comments or behaviors because of your gender identity or gender expression?”. The response options were never (1), less than once a month (2), about once a month (3), two to three times a month (4), about once a week (5), two to four times a week (6), and almost every day (7). Respondents could also choose “not applicable” or “prefer not to answer”. Because sexual orientation and gender identity are not mutually exclusive, some participants answered both questions, in which case the highest score was chosen to represent their level of experienced interpersonal discrimination.

2.2.2 Observed interpersonal discrimination

Observations of interpersonal discrimination were measured with two questions. The first question asked participants “Have you at your workplace, the last 5 years, heard or seen negative comments or behavior because a colleague is perceived as lesbian/homosexual/bisexual?”. The second question was “Have you at your workplace, in the last 5 years, heard or seen negative comments or behavior because a colleague is perceived as having an atypical gender identity or expression?”. For cisgender sexual minority respondents, observed interpersonal discrimination was based on the first question referencing sexual minorities. For heterosexual trans and non-binary individuals, the second question referencing gender identity was employed. The highest score of the two items was chosen for respondents for whom both questions were self-relevant (i.e., sexual minority respondents who were also transpersons). The response options were identical to the measure of experienced interpersonal discrimination, except that “not applicable” was not an option.

Due to highly skewed responses toward never on both interpersonal discrimination items, we chose to dichotomize the two variables to distinguish between participants who had experienced or observed any interpersonal discrimination at work in the last 5 years (1), from those who had not (0). This is a deviation from our pre-registered analysis plan (https://osf.io/d2nwt/?view_only=898ae7453a2f4a76b60237febcff68d8).

2.2.3 Experienced allyship

Experienced allyship was measured with two questions. The first question was “Has someone at work supported, defended, or protected you or your rights as an LGB person in the workplace”. The second question was “Has someone at work supported, defended, or protected you and your rights as a transperson in the workplace?”. The first question was used for cisgender sexual minority respondents, and the second for heterosexual trans and non-binary respondents. The highest score from these two items was chosen for respondents who were both transgender/non-binary and LGB. The response options were never (1), rarely (2), often (3), and always (4). Respondents could also choose “not relevant”.

When initially running our analyses, we noted that a quarter of our sample (n = 173) was excluded because respondents had selected “not relevant” to the question about experienced allyship. Exploratory analyses revealed that 162 of these 173 participants also reported not having experienced interpersonal discrimination. Participants who had not experienced any form of interpersonal discrimination most likely perceived the question about allyship as a follow-up to the question about experiencing interpersonal discrimination, leading them to consider the allyship question “not relevant” to them. We re-coded the responses of these 162 participants from “not relevant” to “never” on experienced allyship. The remaining 11 participants were excluded from the analysis, as described above.

2.2.4 Observed allyship

Observed allyship was measured with the single question “Have you heard of, or seen someone at work support, protect or advocate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender persons or persons with differences of sex development's rights in the workplace?”. Response options were identical to the question about experienced allyship.

2.2.5 Self-rated health

Health was measured with one question about global self-rated health (similar to Ware and Gandek, 1998). The question was posed as “In general, how would you rate your own health” with five response options: very poor (1), quite poor (2), neither good nor poor (3), quite good (4), and very good (5). Respondents could also choose “prefer not to answer”. This question cues participants to consider all aspects of their health that they deem relevant (Idler and Benyamini, 1997; Benyamini, 2011). Self-rated health is associated with a range of objective indicators of health (e.g., blood pressure; Wuorela et al., 2020) and predicts mortality, also when other physical (Kaplan et al., 2007; Lorem et al., 2020), mental (Lorem et al., 2017), and socioeconomic factors are taken into consideration (Kaplan et al., 2007).

2.3 Analyses

Hypotheses and the analysis plan for the study were pre-registered at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/d2nwt/?view_only=898ae7453a2f4a76b60237febcff68d8) before analyses. To test the hypotheses that experiencing and observing allyship buffer the negative effects of experienced and observed interpersonal discrimination on health, we conducted two moderation analyses using model 2 in the PROCESS macro extension (Hayes, 2022) for SPSS version 29. Age was a covariate in all analyses, as self-rated health tends to decline with age (Andersen et al., 2007). When testing the effect of observed interpersonal discrimination, personal experiences of interpersonal discrimination were added as a covariate. Continuous variables were mean-centered before analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive findings

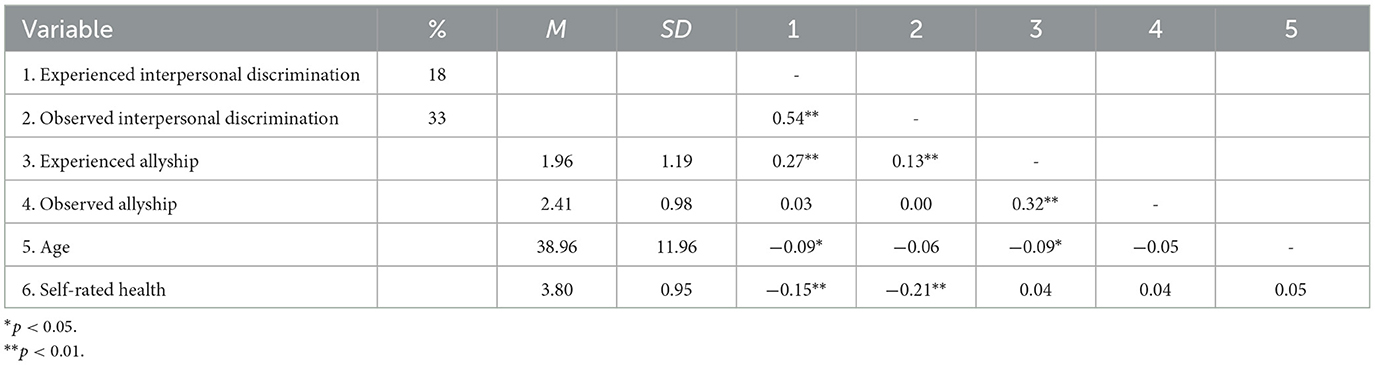

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 2. Of the 438 participants, 18.3 % had experienced interpersonal discrimination at work in the last 5 years. Nearly twice as many (32.9 %) reported that they had observed other SGMs being subject to interpersonal discrimination at work. About half of the participants experienced acts of allyship at work (45.4 % reported allyship occurring “rarely”, “often” or “always”) while observing allyship toward other SGMs was reported more often (76.9 % reported allyship occurring “rarely”, “often”, or “always”).

3.2 Main findings

Hypothesis 1 was supported. Experiencing interpersonal discrimination was negatively associated with self-rated health (r = −0.15, p < 0.001). As expected, observing interpersonal discrimination also correlated negatively with self-rated health (r = −0.21, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2.

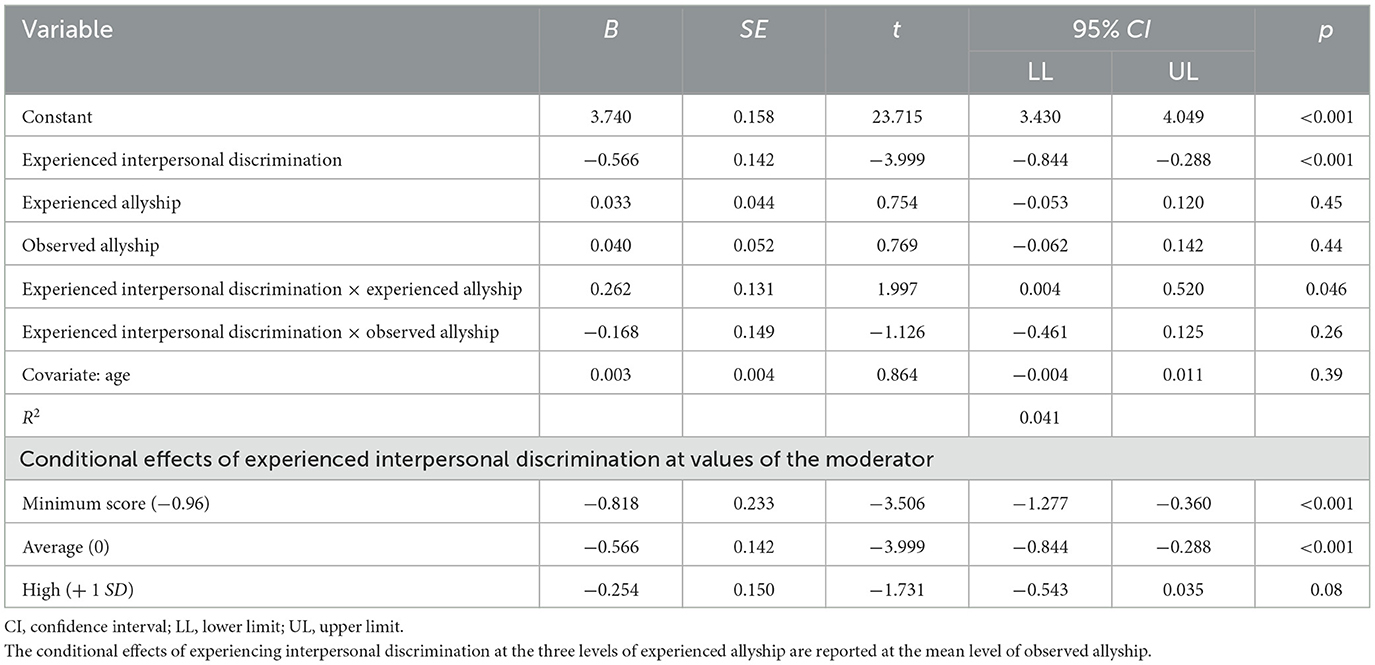

The results of the moderation analyses are presented in Tables 3 and 4. Hypothesis 3 was partially supported. As predicted, the interaction between experienced interpersonal discrimination and experienced allyship was a significant predictor of self-rated health (b = 0.262, p = 0.046, 95% CI [0.004, 0.520]). However, observing allyship toward others did not have an impact on the relationship between experienced interpersonal discrimination and self-rated health (b = −0.168, p = 0.261, 95% CI [−0.461, 0.125]).

Table 3. Moderation analysis. Effect of experienced interpersonal discrimination on health moderated by experienced and observed allyship.

Table 4. Moderation analysis. Effect of observed interpersonal discrimination on health moderated by experienced and observed allyship.

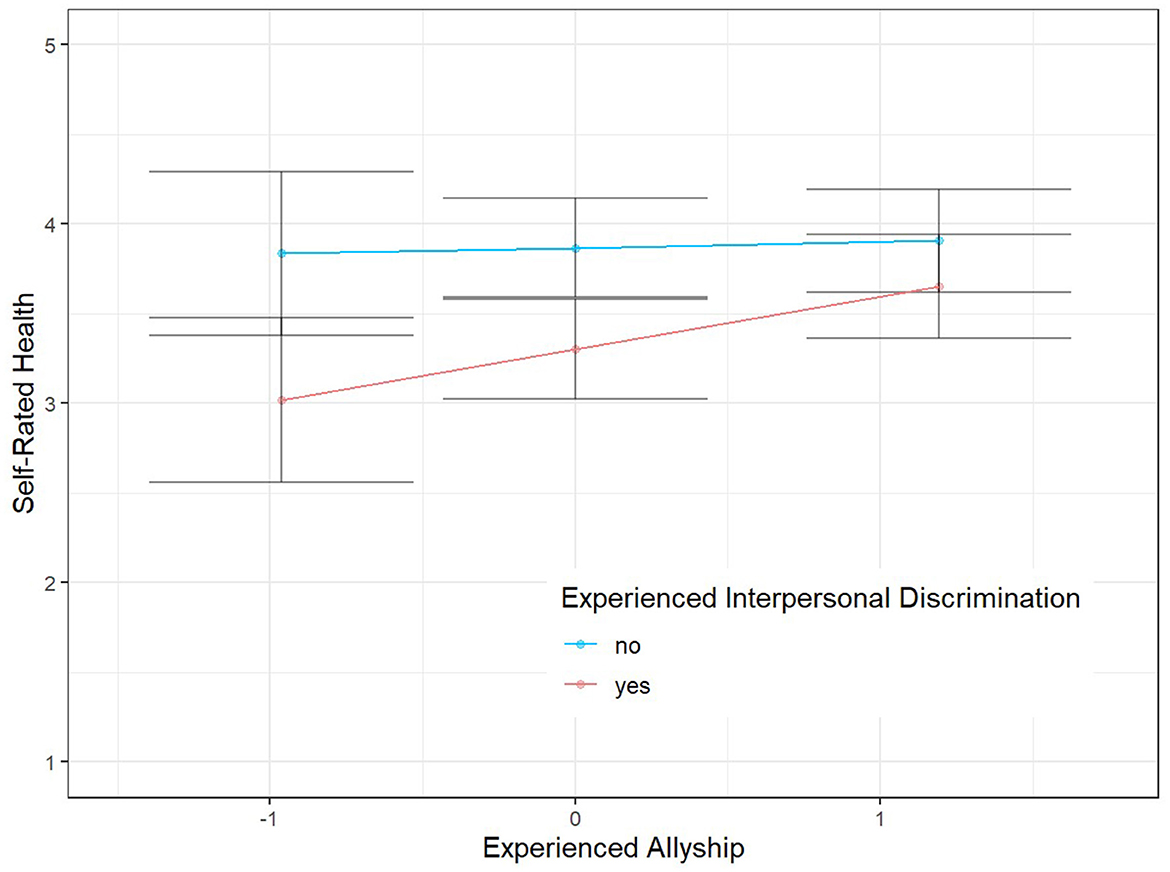

The interaction between interpersonal discrimination and experienced allyship is plotted in Figure 1. It shows that the difference in self-rated health between individuals who have experienced interpersonal discrimination and those who have not is substantially reduced as experienced allyship increases. The conditional effects of experiencing interpersonal discrimination reported in Table 3 show that at minimum and average levels of allyship, respondents who had experienced interpersonal discrimination reported worse self-rated health than respondents who had not experienced interpersonal discrimination. At high levels of allyship, the difference between respondents who had and had not experienced discrimination was no longer significant.

Figure 1. Effect of experienced interpersonal discrimination on health moderated by experienced allyship. The effect of experienced interpersonal discrimination on self-rated health is plotted at the minimum, mean and + 1 SD level of experienced allyship, and at the mean level of observed allyship. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Consistent with Hypothesis 4, the interaction between observed interpersonal discrimination and experiencing allyship was significant in the prediction of self-rated health (b = 0.207, p = 0.028, 95% CI [0.023, 0.391]). However, observing allyship did not moderate the negative relationship between observing interpersonal discrimination and self-rated health (b = −0.120, p = 0.285, 95% CI [−0.339, 0.100]).

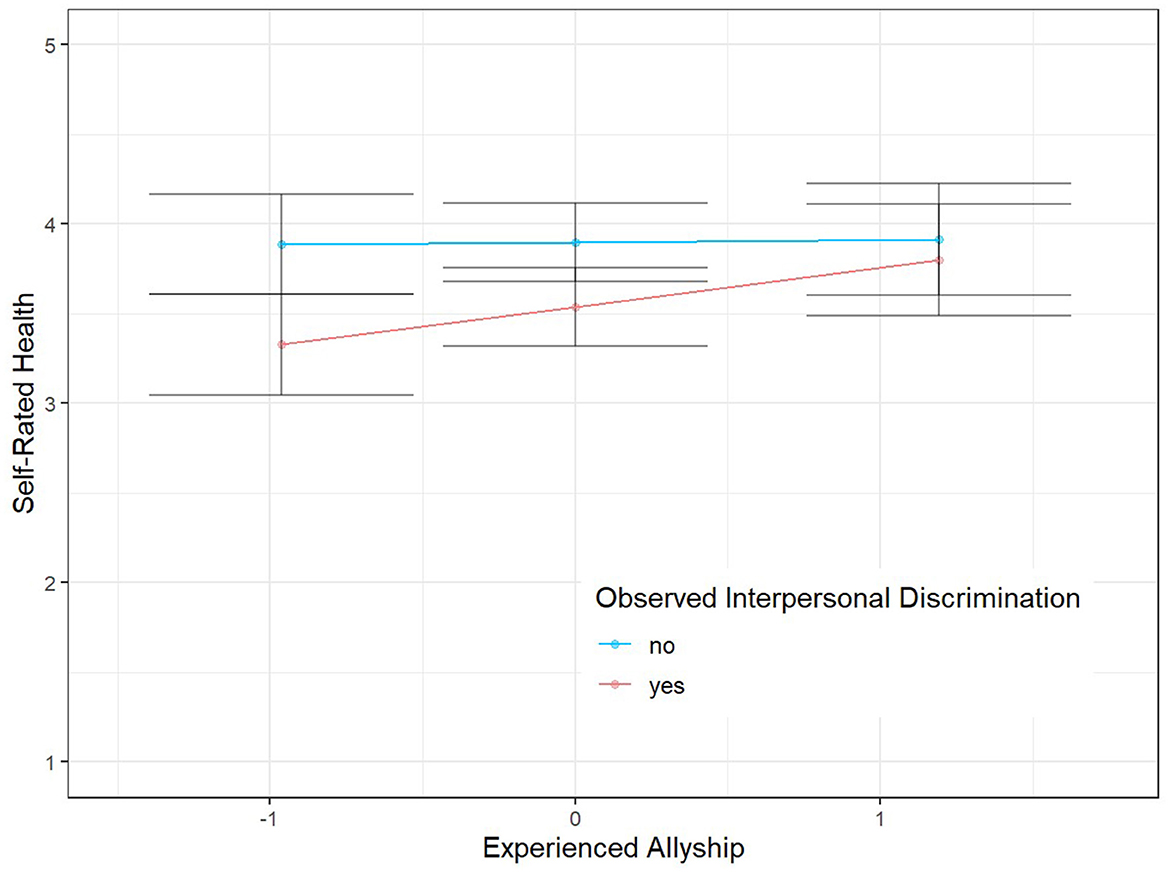

The interaction between observed interpersonal discrimination and experienced allyship is plotted in Figure 2. Similar to the interaction between experienced interpersonal discrimination and experienced allyship, we found that the difference in self-rated health between individuals who have observed interpersonal discrimination and those who have not is substantially reduced as experienced allyship increases. The conditional effects of observing interpersonal discrimination reported in Table 4 show that at minimum and average levels of experienced allyship, respondents who had observed interpersonal discrimination reported poorer self-rated health than respondents who had not observed interpersonal discrimination. At high levels of allyship, the difference between respondents who had and had not observed discrimination was no longer significant.

Figure 2. Effect of observed interpersonal discrimination on health moderated by experienced allyship. The effect of experienced interpersonal discrimination on self-rated health is plotted at the minimum, mean and + 1 SD level of experienced allyship, and at the mean level of observed allyship. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

4 Discussion

This study examined the relationship between interpersonal discrimination and self-rated health and the potential buffering effects of acts of allyship in the workplace among sexual and gender minorities. Consistent with our first and second hypotheses, both experiencing and observing interpersonal discrimination were negatively associated with self-rated health. We further hypothesized that the negative association between interpersonal discrimination and self-rated health would be buffered by both experiencing and observing acts of allyship. These hypotheses were both partially supported, as only experiencing acts of allyship, but not observing allyship, buffered the negative association between interpersonal discrimination and self-rated health.

Our results add to the extensive literature demonstrating the link between SGMs' experiences of discrimination and health (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013; Hoel et al., 2014; Woodford et al., 2014; McFadden, 2015; Jones et al., 2016; Miner and Costa, 2018; Valentine and Shipherd, 2018; Christian et al., 2021; Peterson et al., 2021; Lattanner et al., 2022; Puckett et al., 2023). Whereas previous research among SGMs has focused on depression (Woodford et al., 2014; Scandurra et al., 2018; Valentine and Shipherd, 2018; Lattanner et al., 2022; Puckett et al., 2023), anxiety (Woodford et al., 2014; Scandurra et al., 2018; Valentine and Shipherd, 2018; Puckett et al., 2023), wellbeing (Jones et al., 2016; Deloitte Global, 2023; Lacatena et al., 2024), cardiovascular health (Jones et al., 2016), negative affect, negative emotions (Jones et al., 2016; Miner and Costa, 2018; Puckett et al., 2023), physical, and psychological health complaints (Hoel et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2016; Miner and Costa, 2018), alcohol, and substance use (Jones et al., 2016; Valentine and Shipherd, 2018), and suicidality (Valentine and Shipherd, 2018; Peterson et al., 2021) we show that experiencing and observing interpersonal discrimination at work is also associated with global self-rated health among Norwegian SGMs.

As hypothesized, experiencing acts of allyship from peers buffered the association between experiencing and observing interpersonal discrimination and self-rated health. This is consistent with previous research demonstrating the importance of allies for SGMs' felt identity safety (Chen et al., 2023), wellbeing (Perales, 2022; Deloitte Global, 2023), and psychological health (Webster et al., 2017; Thoroughgood et al., 2021; Collier-Spruel and Ryan, 2022). It is also consistent with the theorized ameliorative effect of social support conveyed in the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003; Frost and Meyer, 2023). However, acts of allyship may be linked to health through increasing feelings of safety rather than, or in addition to, reducing stress. Diamond and Alley (2022) argue that the exclusive focus on minority stress as a predictor of health among SGMs is incomplete, and propose that feeling safe in a social environment is the main predictor of good health. They therefore suggest that there should be a direct link between experiences of social safety and health. If this is the case, experiencing acts of allyship may increase the perceived safety of the workplace and thereby promote health. Future research could include measures of both minority stress, social safety, allyship and health to further probe into the mechanisms of the relationship between discrimination, allyship and health outcomes.

Contrary to our hypotheses, observing acts of allyship did not buffer the negative association between experiencing or observing interpersonal discrimination and self-rated health. These findings indicate an important difference between experiencing and observing allyship. Whereas experiencing allyship seems to signal a strong sense of safety and/or reduce the stress associated with discrimination, the perceived risk of being exposed to interpersonal discrimination may outweigh the beneficial effects of seeing others being defended, protected, or supported. Hildebrand et al. (2020) showed that following racial or sexist remarks, observing allyship was only effective when it was affirmed by other employees. In other words, a single ally may not successfully transmit safety to SGMs, but SGMs may benefit when the ally is supported by other colleagues.

Alternatively, observing acts of allyship may have been an ineffective buffer because our study grouped SGM individuals who may have unique experiences together (Fassinger and Arseneau, 2007). Given that experiencing acts of allyship is beneficial because it signals that a specific identity is valued (Thoroughgood et al., 2021), acts of allyship may not signal value between different SGM groups. For example, observing a gay colleague being supported at work may not be protective for a transgender person, but could be protective for gay colleagues. This calls for further examination. For instance, future research could adapt Hildebrand et al.'s (2020) experiment to test whether observing an in-group SGM person being defended improves health-related outcomes (such as psychological safety) more than observing allyship directed at an SGM out-group individual. Future research should also address if affirmation from colleagues is necessary to benefit from observing acts of allyship, across both in-groups and out-groups.

4.1 Limitations

Our data was gathered from the fourth national survey of living conditions among Norwegian SGMs (Anderssen et al., 2021). The survey covered an array of topics related to the health and wellbeing of Norwegian sexual minorities, and, for the first time, gender minorities. This broad scope of the survey provides valuable insight into a wide range of issues concerning Norwegian sexual and gender minorities. However, the survey was not specifically designed to address our research topic. Ideally, we would have employed a more detailed and sensitive scale to measure interpersonal discrimination. We relied on a question that asked participants about negative comments or behavior in the last five years, with response options ranging from 6 (“daily”) to 1 (“less than once a month”) to 0 (“never”). Given the large skew we observed, the response options may not have been sensitive enough to capture interpersonal discrimination events that occurred less frequently than once a month. If using a five-year timeframe, future studies could add additional response options, such as “2–5 times the last 6 months”, “2–5 times a year”, and “less than once a year”. This item also asked participants to consider both negative comments and behavior at the same time, perhaps increasing the complexity of the question. Lastly, this measure may not have been sensitive enough to evoke recall of very subtle forms of interpersonal discrimination (Hebl et al., 2002).

4.2 Implications and conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate allyship as a buffer against the negative association between experiencing or observing interpersonal discrimination in the workplace and self-rated health. We have shown that allies who support, protect, or defend sexual and gender minorities against negative comments and behaviors can mitigate the negative impact of interpersonal discrimination on health. These novel findings add to the literature on acts of allyship as a potential source of resilience for SGMs wellbeing (Thoroughgood et al., 2021; Collier-Spruel and Ryan, 2022; Perales, 2022; Chen et al., 2023; Deloitte Global, 2023), and extend it to self-rated health.

Furthermore, this study has implications for organizational practice. Though organizations' formal anti-discrimination work may be limited in preventing interpersonal discrimination (Seiler-Ramadas et al., 2022), organizations could attempt to create work environments where coworkers hold each other accountable and speak up against mistreatment of others. Specifically, organizations can encourage their employees to contest biased treatment against their coworkers if they witness it. In addition to the protective effects for SGMs' health found in this study, this is also evidenced to be effective for reducing interpersonal mistreatment at work (Chaney and Sanchez, 2018; Chaney et al., 2021).

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2825850.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (project number 84944) the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services and Education (project number 636878). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. TS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Project administration. HB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. LB and TS received a personal scholarship from the Faculty of Psychology to conduct research over 1 year from 2023-2024. No other funding was received for this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Norman Anderssen for insightful advice and discussions in the initial phases of the research process.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. AI was used in developing scripts in R when making graphs.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andersen, F. K., Christensen, K., and Frederiksen, H. (2007). Self-rated health and age: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study of 11,000 Danes aged 45–102. Scand. J. Public Health 35, 164–171. doi: 10.1080/14034940600975674

Anderssen, N. Eggebø, H., Stubberud, E., and Holmelid, Ø. (2021). Seksuell orientering, kjønnsmangfold og levekår [Sexual orientation, gender diversity, and living conditions]. Norway: Institutt for samfunnspsykologi, Universitetet i Bergen.

Anderssen, N. Eggebø, H., Stubberud, E., and Holmelid, Ø. (2024). Seksuell orientering, kjønnsmangfold og levekår, 2020′. Sikt - Kunnskapssektorens tjenesteleverandør. Sikt - Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. doi: 10.18712/NSD-NSD3028-V2

Benyamini, Y. (2011). Why does self-rated health predict mortality? An update on current knowledge and a research agenda for psychologists. Psychol. Health 26, 1407–1413. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.621703

Bockting, W., Coleman, E., Deutsch, M. B., Guillamon, A., Meyer, I., Meyer, W. 3rd, et al. (2016). Adult development and quality of life of transgender and gender nonconforming people. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obesity 23:188. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000232

Brooks, A. K., and Edwards, K. (2009). Allies in the workplace: including LGBT in HRD. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 11, 136–149. doi: 10.1177/1523422308328500

Bye, H. H., and Bjørkelo, B. (2024). To add or to multiply? Gender, sexual minority status, and sexual harassment in the norwegian police service. J. Bus. Psychol. 40, 405–417. doi: 10.1007/s10869-024-09958-3

Chaney, K. E., and Sanchez, D. T. (2018). The endurance of interpersonal confrontations as a prejudice reduction strategy. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 44, 418–429. doi: 10.1177/0146167217741344

Chaney, K. E., Sanchez, D. T., Alt, N. P., and Shih, M. J. (2021). The breadth of confrontations as a prejudice reduction strategy. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 12, 314–322. doi: 10.1177/1948550620919318

Chen, J. M., Joel, S., and Lingl, D. C. (2023). Antecedents and consequences of LGBT individuals perceptions of straight allyship. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 125, 827–851. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000422

Christian, L. M., Cole, S. W., McDade, T., Pachankis, J. E., Morgan, E., Strahm, A. M., et al. (2021). A biopsychosocial framework for understanding sexual and gender minority health: a call for action. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 129, 107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.06.004

Cobb, S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Med. 38:300. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003

Collier-Spruel, L. A., and Ryan, A. M. (2022). Are all allyship attempts helpful? An investigation of effective and ineffective allyship. J. Bus. Psychol. 39, 1–26. doi: 10.1007/s10869-022-09861-9

De Lira, A. N., and de Morais, N. A. (2018). Resilience in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) populations: an integrative literature review. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 15, 272–282. doi: 10.1007/s13178-017-0285-x

De Souza, L., and Schmader, T. (2024). When people do allyship: a typology of allyship action. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 29, 3–31. doi: 10.1177/10888683241232732

Deloitte Global (2023). LGBT+ inclusion @ work. Available online at: https://www.deloitte.com/mt/en/about/people/social-responsibility/lgbt-at-work.html (accessed April 27, 2025).

DeSouza, E. R., Wesselmann, E. D., and Ispas, D. (2017). Workplace discrimination against sexual minorities: subtle and not-so-subtle. Can. J. Admin. Sci. 34, 121–132. doi: 10.1002/cjas.1438

Di Marco, D., Hoel, H., Arenas, A., and Munduate, L. (2018). Workplace incivility as modern sexual prejudice. J. Interpers. Violence 33, 1978–2004. doi: 10.1177/0886260515621083

Di Marco, D., Hoel, H., and Lewis, D. (2021). Discrimination and exclusion on grounds of sexual and gender identity: are LGBT people's voices heard at the workplace? Span. J. Psychol. 24:e18. doi: 10.1017/SJP.2021.16

Diamond, L. M., and Alley, J. (2022). Rethinking minority stress: a social safety perspective on the health effects of stigma in sexually-diverse and gender-diverse populations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 138:104720. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104720

Drury, B. J., and Kaiser, C. R. (2014). Allies against sexism: the role of men in confronting sexism. J. Soc. Issues 70, 637–652. doi: 10.1111/josi.12083

Einarsdóttir, A., Hoel, H., and Lewis, D. (2015). “It's nothing personal”: anti-homosexuality in the British workplace. Sociology 49, 1183–1199. doi: 10.1177/0038038515582160

English, D., Rendina, H. J., and Parsons, J. T. (2018). The effects of intersecting stigma: a longitudinal examination of minority stress, mental health, and substance use among Black, Latino, and multiracial gay and bisexual men. Psychol. Violence 8, 669–679. doi: 10.1037/vio0000218

Equality and Anti-Discrimination (2017). Act Relating to Equality and a Prohibition Against Discrimination. c. 2. Norway: Norwegian Ministry of Culture and Equality.

Fassinger, R. E., and Arseneau, J. R. (2007). “I'd rather get wet than be under that umbrella”: differentiating the experiences and identities of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people,” in Handbook of Counseling and Psychotherapy with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Clients, 2nd Edn (Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association), 19–49. doi: 10.1037/11482-001

Frost, D. M., and Meyer, I. H. (2023). Minority stress theory: application, critique, and continued relevance. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 51:101579. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101579

Geldart, S., Langlois, L., Shannon, H. S., Cortina, L. M., Griffith, L., and Haines, T. (2018). Workplace incivility, psychological distress, and the protective effect of co-worker support. Int. J. Workplace Health Manage. 11, 96–110. doi: 10.1108/IJWHM-07-2017-0051

Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol. Bull. 135, 707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Phelan, J. C., and Link, B. G. (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am. J. Public Health 103, 813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069

Hayes, A. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: third edition: a regression-based approach. Available online at: https://www.guilford.com/books/Introduction-to-Mediation-Moderation-and-Conditional-Process-Analysis/Andrew-Hayes/9781462549030 (accessed October 2, 2024).

Hebl, M., Cheng, S. K., and Ng, L. C. (2020). Modern discrimination in organizations. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 7, 257–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044948

Hebl, M., Foster, J. B., Mannix, L. M., and Dovidio, J. F. (2002). Formal and interpersonal discrimination: a field study of bias toward homosexual applicants. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 28, 815–825. doi: 10.1177/0146167202289010

Hildebrand, L. K., Jusuf, C. C., and Monteith, M. J. (2020). Ally confrontations as identity-safety cues for marginalized individuals. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 1318–1333. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2692

Hoel, H., Lewis, D., and Einarsdóttir, A. (2014). The Ups And Downs of Lgbs Workplace Experiences: Discrimination, Bullying and Harassment of Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Employees in Britain. Manchester: Manchester Business School.

Idler, E. L., and Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies, J. Health Soc. Behav. 38, 21–37. doi: 10.2307/2955359

Jolly, P. M., Kong, D. T., and Kim, K. Y. (2021). Social support at work: an integrative review. J. Organ. Behav. 42, 229–251. doi: 10.1002/job.2485

Jones, K. P., Arena, D. F., Nittrouer, C. L., Alonso, N. M., and Lindsey, A. P. (2017). Subtle discrimination in the workplace: a vicious cycle. Indus. Organ. Psychol. 10, 51–76. doi: 10.1017/iop.2016.91

Jones, K. P., Peddie, C. I., Gilrane, V. L., King, E. B., and Gray, A. L. (2016). Not so subtle: a meta-analytic investigation of the correlates of subtle and overt discrimination. J. Manage. 42, 1588–1613. doi: 10.1177/0149206313506466

Kaplan, M. S., Berthelot, J.-M., Feeny, D., McFarland, B. H., Khan, S., and Orpana, H. (2007). The predictive validity of health-related quality of life measures: mortality in a longitudinal population-based study. Qual. Life Res. 16, 1539–1546. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9256-7

Lacatena, M., Ramaglia, F., Vallone, F., Zurlo, M. C., and Sommantico, M. (2024). Lesbian and gay population, work experience, and well-being: a ten-year systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 21:1355. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21101355

Lattanner, M. R., Pachankis, J. E., and Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2022). Mechanisms linking distal minority stress and depressive symptoms in a longitudinal, population-based study of gay and bisexual men: a test and extension of the psychological mediation framework. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 90, 638–646. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000749

Lorem, G., Cook, S., Leon, D. A., Emaus, N., and Schirmer, H. (2020). Self-reported health as a predictor of mortality: a cohort study of its relation to other health measurements and observation time. Sci. Rep. 10:4886. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61603-0

Lorem, G. F., Schirmer, H., Wang, C. E. A., and Emaus, N. (2017). Ageing and mental health: changes in self-reported health due to physical illness and mental health status with consecutive cross-sectional analyses. BMJ Open 7:e013629. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013629

Louis, W. R., Thomas, E., Chapman, C. M., Achia, T., Wibisono, S., Mirnajafi, Z., and Droogendyk, L. (2019). Emerging research on intergroup prosociality: group members' charitable giving, positive contact, allyship, and solidarity with others. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 13:16. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12436

Malterud, K., and Bjorkman, M. (2016). The invisible work of closeting: a qualitative study about strategies used by lesbian and gay persons to conceal their sexual orientation. J. Homosexuality 63, 1339–1354. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1157995

McFadden, C. (2015). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender careers and human resource development: a systematic literature review. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 14, 125–162. doi: 10.1177/1534484314549456

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 129, 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Meyer, I. H. (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychol. Sex. Orientation Gender Divers. 2, 209–213. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000132

Miner, K. N., and Costa, P. L. (2018). Ambient workplace heterosexism: implications for sexual minority and heterosexual employees. Stress Health. 34, 563–572. doi: 10.1002/smi.2817

Oliveira, A., Pereira, H., and Alckmin-Carvalho, F. (2024). Occupational health, psychosocial risks and prevention factors in lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, asexual, and other populations: a narrative review. Societies 14, 146–177. doi: 10.3390/soc14080136

Perales, F. (2022). Improving the wellbeing of LGBTQ+ employees: do workplace diversity training and ally networks make a difference? Prevent. Med. 161, 107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107113

Peterson, A. L., Bender, A. M., Sullivan, B., and Karver, M. S. (2021). Ambient discrimination, victimization, and suicidality in a non-probability U.S. sample of LGBTQ adults. Arch. Sex. Behav. 50, 1003–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01888-4

Puckett, J. A., Dyar, C., Maroney, M. R., Mustanski, B., and Newcomb, M. E. (2023). Daily experiences of minority stress and mental health in transgender and gender-diverse individuals. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 132, 340–350. doi: 10.1037/abn0000814

Rasinski, H. M., and Czopp, A. M. (2010). The effect of target status on witnesses reactions to confrontations of bias. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32, 8–16. doi: 10.1080/01973530903539754

Russell, S. T., and Fish, J. N. (2016). Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 12, 465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153

Sarason, I., Levine, H. M., Basham, R. B., and Sarason, B. R. (1983). Assessing social support: the social support questionnaire. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 44, 127–139. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.44.1.127

Scandurra, C., Bochicchio, V., Amodeo, A. L., Esposito, C., Valerio, P., Maldonato, N. M., et al. (2018). Internalized transphobia, resilience, and mental health: applying the psychological mediation framework to Italian transgender individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15:508. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15030508

Schilling, R. F. (1987). Limitations of social support. Soc. Serv. Rev. 61, 19–31. doi: 10.1086/644416

Schwarzer, R., and Leppin, A. (1991). Social support and health: a theoretical and empirical overview. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 8, 99–127. doi: 10.1177/0265407591081005

Seiler-Ramadas, R., Markovic, L., Staras, C., Medina, L. L., Perak, J., Carmichael, C., et al. (2022). “I don't even want to come out”: the suppressed voices of our future and opening the lid on sexual and gender minority youth workplace discrimination in Europe: a qualitative study. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 19, 1452–1472. doi: 10.1007/s13178-021-00644-0

Selvanathan, H. P., Lickel, B., and Dasgupta, N. (2020). An integrative framework on the impact of allies: how identity-based needs influence intergroup solidarity and social movements. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 1344–1361. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2697

Sloan, M. M. (2012). Unfair treatment in the workplace and worker well-being: the role of coworker support in a service work environment. Work Occup. 39, 3–34. doi: 10.1177/0730888411406555

Smith, I. A., and Griffiths, A. (2022). Microaggressions, everyday discrimination, workplace incivilities and other subtle slights at work: a meta synthesis. Hum. Resou. Dev. Rev. 21, 275–299. doi: 10.1177/15344843221098756

Synnes, O., and Malterud, K. (2019). Queer narratives and minority stress: stories from lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals in Norway. Scand. J. Public Health 47, 105–114. doi: 10.1177/1403494818759841

Taylor, S. E. (2011). “Social support: a review,” in The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology (Oxford Library of Psychology) (New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press), 189–214. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195342819.013.0009

Thoroughgood, C. N., Sawyer, K. B., and Webster, J. R. (2021). Because you're worth the risks: acts of oppositional courage as symbolic messages of relational value to transgender employees. J. Appl. Psychol. 106, 399–421. doi: 10.1037/apl0000515

Valentine, S. E., and Shipherd, J. C. (2018). A systematic review of social stress and mental health among transgender and gender non-conforming people in the United States. Gender Ment. Health 66, 24–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.03.003

Viswesvaran, C., Sanchez, J. I., and Fisher, J. (1999). The role of social support in the process of work stress: a meta-analysis. J. Vocational Behav. 54, 314–334. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1998.1661

Waldo, C. R. (1999). Working in a majority context: a structural model of heterosexism as minority stress in the workplace. J. Couns. Psychol. 46, 218–232. doi: 10.1037//0022-0167.46.2.218

Ware, J. E., and Gandek, B. (1998). Overview of the SF-36 health survey and the international quality of life assessment (IQOLA) project. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 51, 903–912. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00081-X

Webster, J. R., Adams, G. A., Maranto, C. L., Sawyer, K., and Thoroughgood, C. (2017). Workplace contextual supports for LGBT employees: a review, meta-analysis, and agenda for future research. Hum. Resour. Manage. 57, 193–210. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21873

Wilks, S. (2008). Resilience amid academic stress: the moderating impact of social support among social work students. Adv. Soc. Work 9, 106–125. doi: 10.18060/51

Witten, T. (2013). It's not all darkness: robustness, resilience, and successful transgender aging. LGBT Health 1, 24–33. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0017

Woodford, M., Han, Y., Craig, S., Lim, C., and Matney, M. M. (2014). Discrimination and mental health among sexual minority college students: the type and form of discrimination does matter. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 18, 142–163. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2013.833882

Wuorela, M., Lavonius, S., Salminen, M., Vahlberg, T., Viitanen, M., and Viikari, L. (2020). Self-rated health and objective health status as predictors of all-cause mortality among older people: a prospective study with a 5-, 10-, and 27-year follow-up. BMC Geriatr. 20:120. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01516-9

Keywords: interpersonal discrimination, allyship, sexual minorities, gender minorities, LGBT, self-rated health, employee health, bystander intervention

Citation: Bjerkestrand LH, Stabbetorp TM and Bye HH (2025) Interpersonal discrimination and self-rated health among sexual and gender minority employees: the moderating role of allyship. Front. Organ. Psychol. 3:1584053. doi: 10.3389/forgp.2025.1584053

Received: 26 February 2025; Accepted: 05 May 2025;

Published: 27 May 2025.

Edited by:

Cláudia Andrade, Polytechnical Institute of Coimbra, PortugalReviewed by:

Scott Lawrence Martin, Zayed University, United Arab EmiratesMassimiliano Sommantico, Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Bjerkestrand, Stabbetorp and Bye. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lukas H. Bjerkestrand, Ymplcmtlc3RyYW5kLmx1a2FzQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Lukas H. Bjerkestrand

Lukas H. Bjerkestrand Tine M. Stabbetorp

Tine M. Stabbetorp Hege H. Bye

Hege H. Bye