- Swiss Forum for Migration and Population Studies (SFM), University of Neuchatel, Neuchatel, Switzerland

Migration is a central topic in the populist radical right (PRR) discourse, usually perceived within the frames of the politicization of immigration in Europe. Departing from the centrality of distrust in such discourse, we advance the argument that PRR parties strategically use nostalgic narratives to make assertions on both inward and outward migration as an elite-blaming strategy, thus mobilizing paradoxes—presence–absence, crowded–empty, deserving–undeserving—through a sentimental longing for a better past. Italy, Spain, and Portugal have long been countries of emigration that, in the last few decades, have become countries of immigration, too. In Italy, a populist radical right party (Fratelli d’Italia) is in government, and Spain and Portugal, not long ago regarded as exceptions in Europe’s populist radical right sweep, have seen a rapid mainstreaming and growth of these movements (Vox and Chega), now consolidated as the third-biggest parties in terms of parliamentary representation. By analyzing party manifestos of recent general elections (2022, 2023, and 2024), we shall posit that the populist radical right discourse in Southern Europe layers ideas of overlapping, protracted crises threatening the future of the nation and its people against the backdrop of a glorified past that unifies a ‘virtuous’ population. Nostalgia conveys distrust channeled towards specific actors, thus creating an intelligible discursive framework for grievances and their populist radical right rationale. Mobility takes a central place in the politics of nostalgia, as particular e−/im-migration narratives emerge vis-à-vis ethnonational concerns emphasizing a widening gap between a hopeful past and a woeful present.

Introduction

Populism—defined as one of the key threats to democracy by much scholarship since the early 2000s—has held experts increasingly concerned (Canovan, 2002; Arditi, 2004; Albertazzi and McDonnell, 2008; Abts and Rummens, 2007). In the late 1990s and early 2000s, studies looking at globalization and its crises showed how these phenomena had contributed to the development of a feeling of constant insecurity, suspicion towards change, and a perception of the incapability of the nation-state to protect its citizens from crises (Tuathail, 1999): it is in this context that populist politicians capitalized on people’s fears and anxieties to gain power by selling specific promises. In addition, research in the early 2000s started investigating what was to become a crucial object of study in populist discourse today: the use of distrust and the meaning and significance of trust in populist arguments (Hameleers, 2020; Bonikowski, 2016; Farrand and Carrapico, 2021; Fieschi and Heywood, 2004). The sentiment of distrust has been instrumentalized by populist discourse towards elites at the national and supranational levels (Farrand and Carrapico, 2021; Hameleers, 2020; Grigoriadis, 2020). At the supranational level, distrust in populist discourse has mostly been directed towards EU technocratic elites (Reiser and Hebenstreit, 2020; Csehi and Zgut, 2021; Sata, 2023) despite research showing that populism and technocracy have often more in common than we might believe, given their complementary critique of party democracy (Bickerton and Accetti, 2017: 188).

Research has also investigated populist discourse of distrust towards specific societal groups. Many studies investigate the discursive hostility towards the press, experts, and scientists, who, according to this discourse, are devoted to knowledge and expertise rather than committing to the people’s interests and sentiments (Carnegie et al., 2024; Martinico and Monti, 2024; Imran and Javed, 2024). Distrust might also be expressed towards specific societal groups who may not always be a political group, such as religious minorities and foreigners—migrants from specific backgrounds—encouraging specific attitudes towards these minorities (Bonikowski and Zhang, 2023; Campani, 2018; Nowicka, 2018; Kamenova and Pingaud, 2017). Right-wing populism and ethnonationalism have, in fact, often been linked and associated with one another: the reference to we, the people in right-wing populist discourse implicitly excludes part of the population, namely those belonging to racial, ethnic, or religious minorities (Bonikowski and Zhang, 2023; Rooduijn and Pauwels, 2011; Varshney, 2021). Research has thus brought evidence of distrust as a powerful, dominant emotion found in populist discourse; and its strategic appeal in political discourse seems to concern social scientists. In fact, the debate on populism as a threat to democracy has become increasingly central to studies in political science, political philosophy, and sociology, with populism often being associated with a crisis of democracy (Mudde and Kaltwasser 2012; Havlík 2016; Weyland 2020; Akkerman et al., 2014): Spittler (2018) reported evidence showing that right-wing populist parties do have a negative effect on democratic quality when they gain power and form governments.

In this article, we investigate the use of distrust in Southern European populist radical right (PRR) discourses, emphasizing similarities and differences and identifying a specific discursive strategy, answering the research question: how is the emotion of distrust strategically used in discourse by Southern European PRR parties? We advance the argument that the PRR parties utilize a specific strategy of nostalgic discourse aimed at conveying and reinforcing distrust. It is through a discourse in which nostalgia is a central emotion—a longing for a morally superior past (Elgenius and Rydgren, 2022)—that PRR parties justify a strong feeling of distrust towards (a) national and regional elites; (b) supranational ideologies, entities, and organizations (e.g., the European Union); and (c) societal groups or individuals considered alien to the nationals (non-nationals/non-citizens). The predominant use of nostalgia in the discourse is an extremely powerful tool for inciting distrust towards the present and specific parts of present society. The PRR parties provide a straightforward solution to a rotting society by rationalizing securitization in the face of mobility. Security is introduced in the discourse as the solution to a distrustful society, not only by tightening border control but also by legitimizing othering processes in order to preserve a notion of we, the people. The strategic use of nostalgia often focuses on this exclusionary notion; on the one hand, it restricts who belongs to the people and, on the other hand, it stretches the meaning of national belonging in the present to an ancestral belonging that evokes a historical, often selective or even fantasized past. The identification of mobility, either as immigration or emigration, as an issue by PRR parties and its inclusion in a nostalgic repertoire emanating distrust is, we argue, a key feature of Southern European PRR parties in their attempt to ideologically reconcile long histories of emigration with pronounced, albeit recent, trends of increasing migrant populations. The uses of nostalgia are multifaceted, but we argue that mobility, in particular, is regarded by PRR parties through these lenses, as nostalgia allows them to further distrust by contrasting past and present in a discourse aimed at identifying culprits for national decline and insecurity. Furthermore, the PRR parties’ nostalgic discourse is certainly in tune with the European Zeitgeist, as 67% of the European public thinks that the world used to be a better place (de Vries and Hoffmann, 2018).

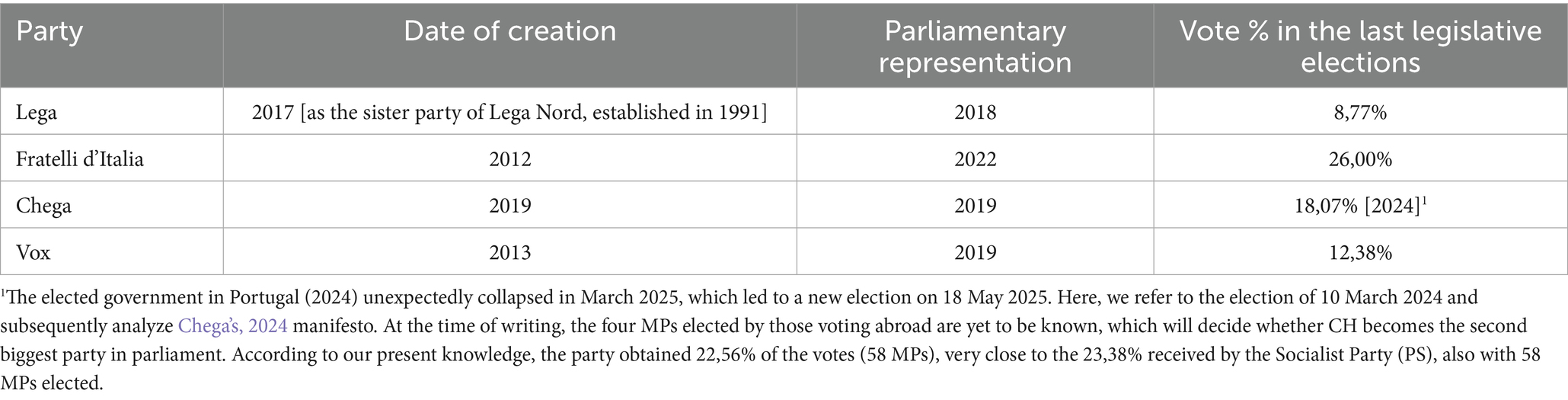

Comparing Lega, Fratelli d’Italia [FdI], Chega [CH], and Vox offers valuable insight into how populist radical right (PRR) parties in Southern Europe mobilize distrust of elites and institutions alongside nostalgia for idealized national pasts. While sharing core PRR traits (Mudde, 2007), these parties differ in how they evoke historical memory—post-fascism in Italy, authoritarian conservatism in Portugal, Francoism in Spain—reflecting distinct national narratives (Innerarity and Giansante, 2025) through the same emotions. Their rise amid economic insecurity and political disillusionment (Pappas and Kriesi, 2015) makes them ideal for analyzing how distrust and nostalgia reinforce PRR appeal in comparable yet varied contexts (Table 1).1

Table 1. Founding dates, electoral breakthroughs, and recent performance of PRR parties in Southern Europe.

By looking at two key emotions—nostalgia and distrust—through which PRR parties propose readings of mobility-connected issues, we aim to analyze how these emotions are deployed and clarify their discursive implications in four political manifestos, thus identifying their tendencies and affinities at national (Italy, Portugal, Spain) and transnational (Southern Europe) levels. The shared history and current status of emigration countries that are, nevertheless, deeply concerned with immigration (Grignoli et al., 2024; Lama et al., 2025; Zerka, 2019) make the choice of these three countries particularly relevant. In addition, what makes the study of these countries’ PRR parties pertinent and urgently needed is their effective capability of networking and drawing inspiration from one another to gain visibility and, ultimately, electoral success; for example, the leader of FdI and the one of CH have delivered speeches at Vox’s rallies on numerous occasions, even if only CH is part of the Identity and Democracy political group at the European Parliament (with Lega). Their stance on mobility usually identifies a common overarching narrative on migration and blame-shifting, but, even if the villains are usually the same, there are relevant variations in what is picked from the repertoire, a selection stemming from the workings of nostalgia when adopting context-dependent historical scripts.

Populism, nostalgia, and distrust: a theoretical framework

Despite the overall agreement on populism as a ‘quintessentially contested concept’ (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017: 2–5), some guidelines are advanced by scholarship allowing for its identification: populism is generally perceived as a worldview (Müller, 2017) or a communication style (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007) according to which there is an ongoing struggle between ‘corrupt elites’ and ‘the noble people’; a definition that points, therefore, to its anti-elitism and people-centrism (Mudde, 2004). Although the populist phenomenon may occur across the political spectrum (Akkerman et al., 2014; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017), we will focus here on a radical right type of populism as ‘political claims-making predicated on a moral opposition between corrupt elites and the virtuous people, with the latter viewed as the only legitimate source of political power’ (Bonikowski and Zhang, 2023: 182). The worldview supported by the populist radical right relies, therefore, on the core assumption that democracy—and more concretely, democratic representation—has gone through a process of distortion, proposing alternative ways of doing politics that would be, according to their proponents, morally better and more consistent with democratic ideals (Chatterjee, 2020: 120–1). The populist rhetoric has thus been associated with feelings of political discontent (Rooduijn et al., 2016), protest attitudes (Schumacher and Rooduijn, 2013), conspiracy beliefs (Erisen et al., 2021; Van Prooijen et al., 2022), and ontological insecurity (Kinnvall, 2018). Furthermore, according to Webber (2023: 862-6), there are common tendencies and affinities stemming from the core elements—anti-elitism and people-centrism—of the populist radical right worldview: (i) a ‘narrow and exclusive definition of the people’ that often follows (ii) ascriptive characteristics (promoting racism, religious intolerance, rejection of cultural diversity, etc.); (iii) opposition to immigration; (iv) a skeptical view of professional experience, science, and education; (v) a ‘sense of wounded dignity, victimhood, disrespect, or vulnerability’; (vi) ‘manipulative,’ ‘duplicitous’ appeals; (vii) nationalist politics; (viii) illiberality; (ix) executive-dominated government; (x) economic grievance; (xi) rural bedrock.

In the literature on populism, Italy is frequently taken as a case study, ‘a showcase’ of these parties, given that populists have had a more durable hold on government (Verbeek and Zaslove, 2016; Caiani and Graziano, 2016). For this reason, there has been a burgeoning literature on the continuities and changes observed in Italian populist right-wing parties, their discourse and ideology, in the past few years (Puleo and Piccolino, 2022; Alekseenkova, 2022), thus paving the way for a variety of approaches (Ozzano, 2021; Di Matteo and Mariotti, 2021) and comparative studies, namely with other Southern European/Mediterranean countries (Marcos-Marne and Sendra, 2024; Chryssogelos et al., 2023). Spain and Portugal have also seen an upsurge in academic interest after a long-lasting perception of the Iberian countries as exceptions in the European political landscape (Quintas da Silva, 2018; da Silva and Salgado, 2018; Vázquez-Barrio, 2021; Enríquez and del Carmen, 2017), overturned by the emergence of Vox and CH (Dennison and Mendes, 2019; Turnbull-Dugarte, 2019; Küppers, 2024). Some studies have underlined common features regarding the main drivers of right-wing populism intensity in these three countries, such as the exacerbation of the economic situation and destabilization of the political system after the 2008 financial crisis (Ruzza, 2018), precarity and financial/work insecurity (Zhirnov et al., 2024), long-term cultural change (Manunta et al., 2022; Baro and Jenssen, 2024), and immigration (Mora Castro, 2023), as well as national differences between PRR parties (Heyne and Manucci, 2021; Chamusca, 2024; Biscaia and Salgado, 2022). Recent works have further specified national differences regarding these parties’ rhetoric: Vox’s focus on state unity and mobilization of anti-feminist sentiment (Heyne and Manucci, 2021); CH’s rising support stemming from an ability to articulate the discontent of marginalized rural areas (Magalhães and Cancela, 2025), even within a national context typically characterized by ‘apparent social calm’ and a relative absence of organized public dissent (Chamusca, 2024: 2); and Italy’s FdI, extremely successful in presenting itself as a novelty within the context of radical right populism, and Lega, with its history of separatism, and their obsession with immigration and national security (Donà, 2022).

Despite the overall anti-establishment message and binary worldview, some authors have shown the adaptability of PRR parties when claiming the defense of a national heritage against immigrants and globalists: they are influenced by contextual factors as well as host ideologies (Fernández-García and Valencia-Sáiz, 2023), often tailoring the common features of populism to a specific national context (Biscaia and Salgado, 2022) to adapt to voters’ preferences (Michel, 2020). Therefore, considering the discursive features of PRR parties in Southern Europe specifically can, on the one hand, highlight the role of national characteristics for the flourishing of these parties in a political scene that had until recently been inauspicious (Valentim, 2024); and, on the other hand, shed light on a broader Southern European program of democratic regeneration in the face of a perceived crisis of representation (Luengo and Fernández-García, 2019), reinforcing economic and cultural grievances within the broader European context.

Distrust and nostalgia can be identified as emotional pillars as well as discursive lenses through which PRR parties make claims and build a political program. Firstly, anti-elitism constitutes in itself a deep-rooted, targeted distrust towards powerful elites and other ‘elite-like groups’ seen as capable of influencing politics and society (Springer and Ege, 2023). Distrust has been commonly understood as a feeling of unease and suspicion towards politics (Korvela and Vento, 2023), or the perception that the political system will act maliciously rather than beneficially (Newton, 2007: 344), thus expressing a lack of trust toward the political system in its entirety or components (Devine et al., 2020; Bunting et al., 2021). Although the concept of elite may be discursively malleable, it usually focuses on politicians as self-interested actors with a personal agenda (Bøggild, 2020), under a general ‘belief that political actors behave in a way that violates the shared moral norms of fairness and justice’ (Bertsou, 2019: 11). Secondly, the populist calls to action to those included in a particular (‘narrow’ and ‘exclusive’) definition of the people tend to draw ‘a comparison between a currently corrupt political system and a much better, glorious past’ (Van Prooijen et al., 2022: 952). Nostalgia is defined as the longing for a ‘glorious era’ that a construed ‘everyone’ can rally around (Elçi, 2022; Routledge et al., 2008); and, in the populist discourse, this ‘everyone’ transpires from a notion of the people as an ‘empty signifier’ (Laclau, 2005), i.e., a hegemonic representative of a collection of unsatisfied demands in the construction of a popular identity presupposing exclusion (Laclau, 2000). Societies dealing with aging populations, mass immigration, and economic setbacks are argued to be particularly susceptible to a collective nostalgia (Campanella and Dassù, 2019) that attributes to the past a sort of moral superiority (Elgenius and Rydgren, 2022) against perceived collective threats to national identity (Lammers, 2023) and ominous feelings of loss and decline (Gaston and Hilhorst, 2018). It is not surprising, thus, that the literature has suggested links between nostalgia, nativist narratives (Kešić et al., 2022; Bertossi et al., 2022), and populism (Van Prooijen et al., 2022; Frischlich et al., 2023; Couperus et al., 2023; Insero, 2022).

The uses of a narrative framework by PRR parties, we argue, tend to reinforce and dialogue with feelings of distrust. PRR parties identify current culprits for the loss of a former glory and call a virtuous people to, under the party’s guidance, save society from the moral decline brought about by the ‘globalizing’ agendas and ‘woke’ ideologies supported by national and/or supranational elites. Therefore, only the party can provide a return to the better times people long for, thus fulfilling a national destiny. Through nostalgia, populists tell a story of how trust was lost—and make programmatic claims on how they will restitute it to the people.

Methods of data collection and analysis

In order to detect the uses of nostalgia to convey distrust in the statements of PRR parties in Southern Europe, we analyzed party manifestos for each country’s latest general elections (2022, 2023, and 2024), retrieved from the websites of Fratelli d’Italia, Lega Nord, Vox, and Chega.

In these manifestos, we identified discourses referring to feelings of distrust as (i) unease and suspicion towards political elites, institutions, and/or specific societal groups (Korvela and Vento, 2023) and (ii) the people’s perception that the political system will act maliciously rather than beneficially (Newton, 2007: 344). After a preliminary survey of the documents, we hypothesize a link between distrust and nostalgia, which we detected as being particularly dominant on issues connected to mobility—here encompassing both emigration and immigration. To identify how nostalgia and distrust are discursively linked to mobility, we need to primarily look for and analyze these emotions. We conceptualize nostalgia as the longing for a more prosperous, predictable, socially homogeneous (rethinking of the) past. Nostalgia points to a sense of decline and an irreversible loss of a past, one that is often fantasized as a golden age. As a result, a society that was supposedly thriving in the past is seen as undergoing major, nefarious changes in the present (nostalgia), a phenomenon for which there are, according to the PRR discourse, specific culprits (distrust).

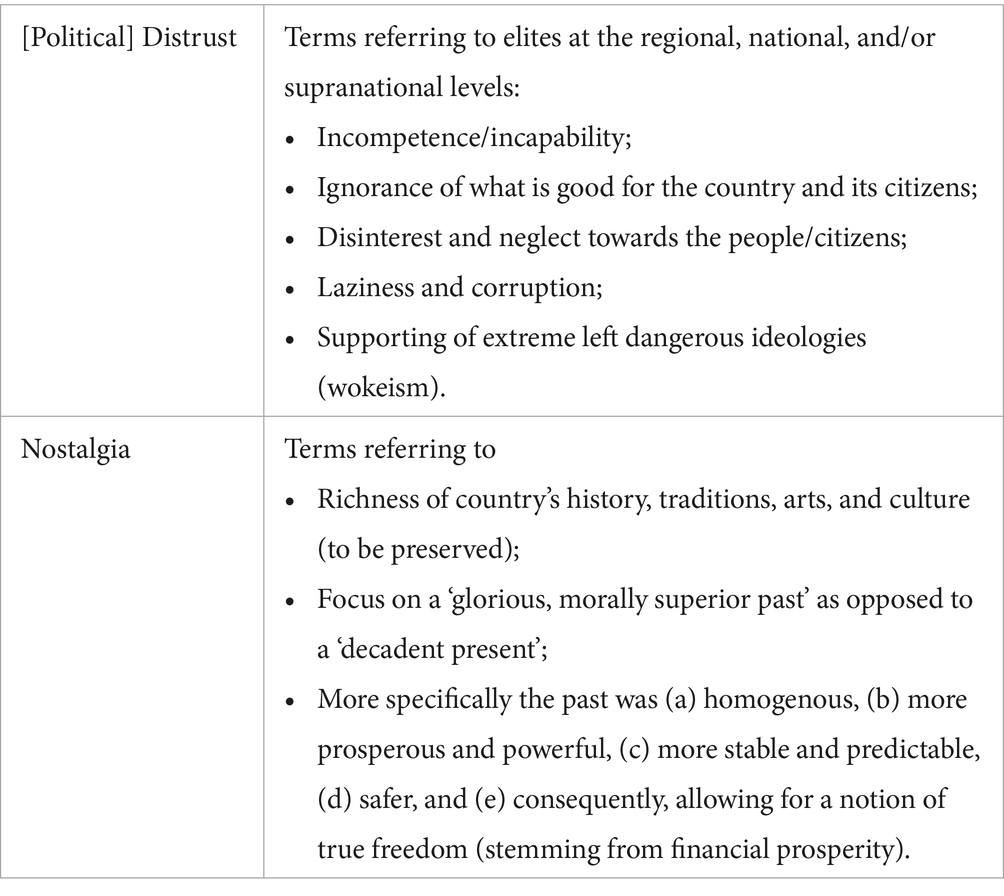

The explicit terms of distrust or lack of trust tend to indicate a broadly shared feeling, expressing how the people these parties claim to represent (should) feel. Terms and themes that, we argue, indicate distrust point to the incapability, corruption, laziness, and disinterest in, or negligence of, the people’s best interests. We identified the feeling of nostalgia when finding terms that refer to the beauty, might, and values of the past, focusing specifically on nostalgic narratives of mobility conveying distrust. Table 2 summarizes our operationalization:

The Rinascimento Italy deserves: grand promises to relieve the bel paese

Within the Italian case, we investigate the narratives of Lega Nord, currently Lega, and Fratelli d’Italia (FdI). These two parties represent the most prominent PRR parties in the country and, considering the results of the last Italian elections in 2022, the most relevant PRR parties in our region of interest, Southern Europe. Indeed, in the last elections, the center-right pursued a specific strategy—as opposed to the center-left—by presenting itself united, with Meloni’s FdI, Matteo Salvini’s Lega, and Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia sharing an electoral platform. Electoral rules privileged the larger coalition; nevertheless, it was FdI that won the orchestrated internal race, gaining almost 22 percentage points, while Lega and Forza Italia lost 8.6 and 5.9 percentage points, respectively, considering their results in 2018 (Puleo et al., 2024). FdI successfully managed to present itself as a novelty in the context of the populist radical right, contrasting with a Lega still holding to a tradition of strong regionalism. FdI is considered a nativist party, conceiving the Italian national identity as the expression of a single, homogeneous Italian community sharing a common history, specific cultural heritage, and traditional values (Donà, 2022). On the other hand, Lega is rightly defined in several studies not only as a PRR party but also as a regionalist one (Newth, 2019); while presenting all of the characteristics of a PRR party, Lega came into existence with a specific separatist goal that was progressively de-radicalized while maintaining a focus on the autonomy of regions and municipalities. Research has, in fact, highlighted how, under the leadership of Matteo Salvini, Lega distanced itself from its early separatist purposes through a process of ideological rethinking that placed the defense of the nation, its values, culture, and interests at the center of its discourse (Albertazzi et al., 2018). Both parties can thus today be defined as part of the European PRR constellation.

In these parties’ manifestos, we identify distrust towards national political elites, with specific hostility towards the left (generalized as la sinistra), which cannot be trusted due to ‘the damages it has brought to the country’ and the incompetence its governments have demonstrated throughout the years. La sinistra is described as incompetent, disinterested, and detached from the struggles of the average Italian citizen. La sinistra has radicalized society and promoted specific ‘radical’ and ‘dangerous’ ideologies. It is also accused of ‘Europeanizing’ the objectives and needs of the country, giving up sovereignty to a supranational entity, such as the European Union, and its elites. Both parties express concerns about the erosion of Italian sovereignty: the European Union is mainly seen as an enemy regarding environmental policy demands and the lack of cooperation in migration governance. Terms related to distrust are also directed towards minorities and, within minorities, the people these manifestos refer to as ‘immigrants.’ It is important to underline that the ‘immigrants’ these manifestos refer to are people on the move from Africa and the Middle East—people who mostly travel through Italy’s southernmost border, Lampedusa, Sicily, and the Central Mediterranean. Although these are clearly not the only people on the move towards/in Italy, these are the ones these manifestos focus on—which is indicative of these parties’ understanding of ‘migration.’ In addition, the term ‘immigrant’ is often used to indicate those who are ‘different,’ the ‘Other,’ phenotypically, ethnically, and frequently religiously, glossing over the fact that many of these ‘immigrants’ might also be Italian citizens. The term ‘immigrant’ is then instrumentalized to indicate the ‘Other in more general terms’: everything and everyone not aligning with these parties’ construction of Italian identity. Inward movement—immigration—is often reported in relation to social problems and disruptions in the country, such as claimed ‘increasing criminality,’ ‘terrorism’ and, in the specific case of Lega, the ‘increasing power of the Nigerian mafia.’ While immigration is generally perceived as something strictly negative and disruptive, both manifestos report instances of what can be defined as acceptable immigration: the ‘qualified one.’ The characteristics of this ‘qualified immigration’ are not specified; however, it must be economically beneficial to the country and contribute to its development.

Outward mobility—emigration—an increasingly relevant issue for the country, is presented in the manifestos as something rather temporary: Italian emigrants are never referred to as such, and the concept of diaspora is never employed to identify more recent flows of emigration; the term is never explicitly mentioned. Italian emigration appears temporary as both manifestos explicitly discuss strategies and policies to ease the return of Italians currently abroad. This focus on Italians’ potential return underlines the temporality that characterizes this emigration, according to these parties. Emigration is, at times, mentioned as a societal problem in Italy under the term ‘brain drain’—strictly referring to younger Italians with higher education—and through the description of ‘depopulated areas of Italy’ such as mountainous and countryside areas. Depopulation is mentioned but rarely specifically linked to outward migration and never considered a consequence of outward mobility—either people moving towards urban centers or out of the country—abroad. Emigration is not mentioned as a concern or disruption for the country except in the case of young graduates moving abroad due to the impossibility of finding a job with their degrees; this is described in particular by Lega as a problem of investment in university services and how they prepare young people to access the job market. There is a denial of emigration as a more general Italian issue.

In the documents, distrust towards the above-mentioned actors develops in parallel with a narrative displaying trust towards the Italian citizen—who is generally a good person (Italiani brava gente), a hard worker, friendly, and generous; the victim of a system that does not have their best interest at hearts, and a hero for surviving under such disastrous circumstances. The nostalgia of the bel paese transpires from discourses around the country’s rich history and magnificent collection of arts and culture—most of which were created when Italy was still very far from being a country at all, which is obviously never mentioned—and the importance of tradition for the country to thrive and return to the growth experienced during the peninsula’s glorious past. This past is located both in a remote past, such as the Renaissance—used by FdI’s narrative to underline that Italy needs a new Rinascimento, which they indeed promise—but also in a more recent time before the extremist ideologies of the left became popular: wokeism, politically correct ideology, multiculturalism, ‘ideological environmentalism,’ and gender identity ideology.2 In both manifestos, Italy is described as ‘the most beautiful country in the world,’ ‘homeland of Christianity,’ and ‘cradle of Western civilization,’ whose tradition and identity need to be protected. This discourse of protection is not just a call to action but a unifying force that binds all Italians in a shared purpose and identity.

Whom must Italy be protected from? A nostalgic discourse allows the manifestos to delve deeper into the critical issues of Italian society and politics today—many societal novelties have brought struggle and threats to the country. Italy, its ‘Western values,’ and its citizens are threatened. Political elites of the left have governed the country against its interests, especially regarding migration and environmental policy and the relationship with the EU—giving up Italian interests in the name of supranationalism. This sense of betrayal by the political elites fuels the call for change and a return to what is defined as Italian values. The EU is also viewed with suspicion—as an entity that gives orders but leaves empty promises/emptiness [lascia vuoti]. The EU, which is referred to as ‘Brussels’—the city that is its bastion, often described as present but helpless—is far from knowing what the Italian citizen wants and needs. The EU does not know what is best for Italy: Lega and Fratelli d’Italia promise to bring Italian interests to the supranational table, defending sovereignty, subsidiarity, and autonomy.

While they both stress the need to protect national sovereignty, Lega, due to its identitarian history based on the fight for separatism and autonomy in the North of Italy, focuses much of its discourse on the defense of local and regional autonomy for a ‘federalist process’ that could take place on the peninsula. This discourse is often connected to the description of the central government and its bureaucracy as ineffective, inefficient, and slow: in the name of this inefficiency and the need for governability and efficiency [governabilità e efficienza], both parties underline the need to introduce presidentialism—the direct election of the Head of State—as Italians are tired of coping with unstable governments that easily fall and change, contributing to dissatisfaction and economic decline. While presidentialism is set to solve the Italian government’s legacy of instability and, consequently, its financial situation, it is an increase in the budget for defense—and the Italian police forces—that, in the eyes of both parties, is set to solve the illness of distrust and the feeling of unsafety that is damaging Italian society in recent times. The obsession with protection and security is visible in many parts of the analyzed manifestos: defense is what brings security and safety in such unstable and unpredictable times—the ones we are living in. As a result, it is an increased budget for defense forces that will bring us back to more secure times—the good old times.

‘Resurrecting’ Portugal: Chega’s quest for the ‘virtuous Portuguese’ within and abroad

10 March 2024: André Ventura, leader of the Chega (CH) Party, announced the end of ‘the two-party system’ in Portugal when it became known that his party had achieved more than 1 million votes, thus consolidating CH as the third political power in parliament. Ventura’s boastful words upon his party’s newly acquired coalition power point to what has been called ‘the normalization of the radical right’ (Valentim, 2024), whose electoral success leads individuals to become more comfortable with expressing such views while encouraging more politicians, both experienced and aspiring, to join a growing party. Indeed, CH’s growth since its creation in 2019 has made it a force to be reckoned with, even if most parties, from left to right, from the opposition to the government, had sworn to keep, in more or less unequivocal terms, a ‘cordon sanitaire’ [cerco sanitário] against CH in any coalitions or agreements. But the political establishment that shuns CH is precisely the one CH points the finger at, finding in it the culprits for the ‘systemic corruption growing in the public institutions [that,] like a toxic element[,] [erodes] … the trust that the Portuguese have on institutions and politicians’ (Chega, 2024: 3), further weakening the confidence in representative democracy from within, alongside a purported threat posed by the European Union in its present federalizing ‘model’ to the Portuguese ‘sovereignty and national independence’ (ibid: 160).

‘Increasing the trust of the Portuguese in politics’ (Chega, 2024: 9) is defined by CH as a priority in its 2024 manifesto, right from the first section of the political program, addressing the issue of corruption. Distrust thus sets the tone and provides the lens through which CH identifies its role as the sole representative of ‘the majority of the Portuguese people’ (ibid: 8) against local and national corrupt elites and the establishment [o sistema] furthering their interests, which ‘the Portuguese’ have good reason to distrust. Calling to itself the mission of ‘cleaning Portugal’ of self-serving elites, their ideological allies, and other malevolent forces, bundling together all the enemies of ‘the people,’ CH uses such an expression as a slogan throughout the electoral campaign, pointing to the party’s broader task, through a messianic wording with nostalgic underpinnings, of ‘resurrecting a country in which the family, society and fatherland [pátria] are at the core of a meritocratic culture in earnest’ (ibid: 9), and thus restoring the trust of ‘the people’ whose interests they commit to represent. Piggybacking on strong religiosity, dissatisfaction with traditional politics, and cultural criticism of globalization and immigration (Marchi and Zúquete, 2024), CH frames key elements with a clear populist character, such as anti-elitism; the centrality of an idea of ‘the people’; an ‘anti-system’ rhetoric; nationalism with a nativist logic; and a sort of messianism (Prior, 2021). ‘The people’—an elusive, albeit clearly moral(izing), concept—is ever present in CH’s discourse. An ‘empty signifier’ (Laclau, 2005), ‘the people’ is used in contrast to (a lesser) something else; usually, ‘the people,’ a righteous, untainted national group, against corrupt, self-serving ‘elites.’

‘The people’ and ‘the elite’ are thus discursively constructed in direct opposition to each other, one representing the ‘virtuous Portuguese’ [Portugueses de bem], often invoked in Ventura’s discourse, and the other personified by those in office who allegedly used the post-revolution democratic developments ‘to settle themselves into power and seize benefits and advantages [for themselves]’ (Chega, 2024: 8). The former—the people—is a force for good, which CH claims to be the voice of, while the latter is the main reason for the ‘rottenness that spread from north to south, including islands, and only we [Chega] have the courage to face it and clean Portugal from it’ (ibid: 3).

CH’s nativist discourse surrounding what ‘people’ the party claims to represent has evolved to rely more heavily on immigration issues, becoming more similar to other European populist radical right parties alongside a consistent trend of an increasing migrant population in Portugal (Oliveira and Reis, 2023). However, one of the main threats identified by CH in earlier party discourse had been the Roma community, regarded as living at the margins of the law and the state under a self-imposed segregation from the general population and, next to corruption, as one of the main drainers of public funds. This enemy of the ‘virtuous Portuguese’ is absent from the 2024 legislative manifesto despite its salience ever since the party’s inception.3 The 2024 manifesto blames instead socialist fiscal policies—characterized as ‘inadequate’ and ‘persecutory of the wealth-creation process, as it penalizes the salaries of those who work the most and put more effort’ (Chega, 2024: 56)—and immigration policies, positioning them under a lens of distrust by placing the moral and practical shortcomings of these policies on national, and to a lesser extent supranational, elites.

For CH, both immigration and emigration are moral issues with political and cultural content. According to the manifesto, the former has been managed through ‘open-door irresponsible policies’ with serious implications for the country, such as the burden placed on the welfare system, linking, moreover, immigration to increased criminality. Adopting a conspiratorial tone—‘contrary to what they would have you believe’ (Chega, 2024: 50), ‘they’ being an unspecified, albeit broad, entity within a narrative of distrust—CH claims to voice the thoughts and feelings of the common citizen, for ‘the Portuguese also thinks so’:

Chega is not against immigration or immigrants. Chega recognizes the importance of immigrants in several sectors of the national economy. Chega is, instead, against immigration without control, of ‘open doors’, [according to which] everyone can enter Portugal without any control. Chega is against an immigration that only seeks social benefits. Massive. That does not want to integrate. That wants to change us and subjugate us culturally, that does not respect our traditions.

According to this view, more regulation means not only tighter control at the border but also ‘to change the paradigm of nationality obtention,’ to select immigrants based on labor demands and their lack of criminal record, promote integration, and institute the ‘crime of illegal residency on Portuguese soil’ (Chega, 2024: 51). This securitizing prescription further distinguishing ‘the virtuous Portuguese’ from immigrants points to the distrust of non-nationals—particularly those of Muslim faith, as ‘Islamic fundamentalism’ is singled out—but even more predominantly to distrust of the elite supporting ‘irresponsible policies’ (ibid: 50). Ultimately, the political elite is the one to blame, as it is allowing in the type of immigrants that, according to CH, threaten the welfare and traditions of the ‘virtuous Portuguese.’

Emigration is also a matter of concern in two sections of the manifesto, on the youth and the diaspora. Unemployment and unattractive salaries leave the highly qualified youth with no option but to leave the country: a ‘social catastrophe with serious political responsibilities, that demonstrates the moral collapse of this Republic and those who govern it’ (Chega, 2024: 62). From the labor problem affecting the youth, CH diagnoses others for ‘youngsters that are less free than their parents or grandparents were,’ jumping from economic issues to a ‘perversion of the notion of freedom’ that allows young people to choose ‘bathrooms’ and ‘pronouns’ but prevents them from having a fair salary, buying a car, or renting their own apartment before turning 30. The culprit here is also clearly stated: there is an ‘amputated generation’ due to ‘decades of a socialist government’ (ibid.: 63). The acritical recalling of the supposedly better times lived by the ‘parents and grandparents’ of this young generation uses nostalgia as a narrative device to inflame distrust, according to which the elites and their ideological allies have perverted the traditional idea of freedom—and implicitly are on their way to defile the morality of a whole generation—to hide their failings in providing true freedom stemming from financial independence. The diaspora, on the other hand, is a ‘valuable asset’ for the country and its moral virtue exalted as part of the Portuguese people. The Portuguese emigrant, a nostalgia-coded metaphor for the Portuguese keeping the connection with ancestral roots and preserving traditions in spite of distance and time, is the ideal immigrant in other countries, for they integrate ‘peacefully’ and are respectful of the host countries’ laws and customs ‘without ever abdicating of their roots’ (ibid: 154). Through a moral estimation of the Portuguese emigrant, CH aggrandizes the Portuguese population numerically: ‘Portugal has 15 million inhabitants and not just the 10 million who reside in national territory’ (ibid.: 154). Therefore, CH proposes the creation of a Ministry for the Portuguese Diaspora [Ministério das Comunidades], with a new attitude aiming to integrate these communities ‘around the world’ into the national whole, i.e., ‘the people’ embodying a set of virtues under their ‘Portuguese-ness [portugalidade],’ which CH claims to represent.

Throughout the manifesto, CH takes for granted several assumptions about the ‘Portuguese identity,’ its ‘European nature and Atlantic vocation’ (Chega, 2024: 63). The exaltation of the people—or an idea of a ‘virtuous Portuguese’—relies on the glorification of the past. Like a ‘trojan horse’, present ideologies (labeled ‘neo-Marxist woke’) and (‘globalizing’) agendas (ibid: 102), to which the allegedly corrupt national elites ascribe, threaten the memory of a glorious past when ‘Portugal built a maritime empire that amazed the world, creating wealth never seen before in a kingdom wedged between mighty Castile and the Atlantic’ (ibid.: 68). According to CH, it is from this past and their ancestors that the ‘virtuous Portuguese’ should take inspiration in the mission of developing and protecting the country while preserving its culture. The exaltation of this skewed view of the historical past makes it even more urgent to unite ‘the virtuous Portuguese’ domestically and abroad against foreign forces that threaten to subjugate them and ‘corrupt elites’ who hinder the fulfillment of a grandiose national destiny.

Make Spain great again? Vox against the ‘enemies’ of the nation

‘We will not let you down, we will resist, Spain will resist,’ promised Santiago Abascal, leader of the Vox party, after knowing the results of the 2023 general elections (Vox España, 24 July 2023). Despite falling short of fulfilling Vox’s ambitions, the electoral results once again confirmed Vox as the third political power in Spain after entering the Andalusian Parliament in 2018 and rising at the national level in the general elections of April 2019, further consolidating its power in the new general elections taking place in November of that same year. Although Vox’s electorate is in line with the usual preoccupations of the PRR repertoire—‘socio-demographics, political dissatisfaction, media diet, and the rejection of immigration and feminism’ (Heyne and Manucci, 2021)—its populist character has been subject to extensive debate among Spanish scholars.

Ferreira (2019: 89-90, 92), for example, while positioning the party clearly on the radical right in the political spectrum, argues that populism is not an ‘explicit’ feature of Vox, as the party ‘is much more nationalist than populist’ (ibid: 94). Aranda Bustamante and Escribano (2022) as well as Rubio-Pueyo (2019) highlight the importance of Francoist legacies to Vox’s ideology, pointing to a Francoism-influenced post-fascist discourse with a populist character. Franzé et al. (2022) posit that it is the ‘post-fascist’ character of Vox that confers to the party a ‘toned down and inverted populism,’ supposedly ‘focused on the designation and defense of a special ‘We’ (p. 87) and in constructing an opposition between expressions of Spanish-ness and anti-Spanish minority collectives (‘secessionism’, feminism, ‘the left,’ immigrants, etc.). The latter are perceived as being presently empowered to the detriment of the traditional status quo and the national order based on the 1978 Constitution and the process of Transition [la Transición] from the Francoist regime to a constitutional democracy.

We consider Vox to be a populist radical right party in the full sense of the term. Although it is nationalism that provides an overarching rhetoric to populist elements, that does not in itself negate the populist character of Vox’s discourse. Ultimately, like its Portuguese and Italian counterparts, Vox formulates political content and ideological postulates, here extracted from its 2023 manifesto, based on populist assumptions, even if and when it does so by resorting to metaphorical framings (Capdevila et al., 2022). Contrary to what has been argued by Franzé et al. (2022), we contend that Vox’s political program includes an anti-elite positioning that does not contradict but rather reinforces the multiplicity—and thus the supposed danger—of enemies, brought together under the alleged neglect or even jeopardy posed by the Sánchez government to the Spanish nation. Moreover, the usage of anti-elite language may be seen as fitting Vox’s broader strategy—starting in 2020, with slogans such as ‘obrero y español’ and the creation of the Solidarity Union appealing to a more working-class electorate (Lerín Ibarra, 2024)—to become a catch-all party.

In Vox’s (2023) manifesto, each and every one of its 20 sections starts by unequivocally placing the blame on Sánchez and his government for the evils plaguing the Spanish nation and the problems threatening the well-being of the Spaniards. Although, contrary to CH’s manifesto, trust [confianza] or lack thereof [desconfianza] is not mentioned once, the distrustful, anti-elite tone is clear from the onset:

Pedro Sánchez will be remembered as the President [of the Government] who was hard and relentless with the honorable Spaniards and soft with the criminals, the enemies of Spain and the foreign elites. His concessions to separatism and his commitment to a multi-level Spain has only benefited the autonomic elites, allowing for the consolidation of an unjust model that hinders the prosperity and welfare of the Spaniards.

This opening paragraph—from the first section on ‘Equality among Spaniards’ (Vox, 2023: 7)—points to topics that are transversal to PRR parties, such as anti-elitism, but also to country-specific issues, such as national unity vis-à-vis the autonomic state [estado de las autonomias]. Indeed, Vox’s growth at the time of the procés català made it easier to define an internal enemy: the independentist movements threatening Vox’s recentralizing program. Such a program is inspired by and based on a key notion of Spain as a ‘reality transcending the Spaniards,’ a ‘fatherland [patria]’ guaranteeing rights and equality, ‘a legacy’ from their ancestors that should be preserved to be left as an inheritance to the next generations (ibid: 15). Indistinctive from internal enemies are other nefarious forces that have detached the ‘compatriots’ from the nation, due to ‘the ideological indoctrination’ caused by ‘separatism and globalism.’ According to Vox, this twofold indoctrination spreads to (and ‘contaminates’) every aspect of life, assisted by feminism, multiculturalism, and progresismo under the umbrella of the so-called ‘extreme left.’ Moreover, this indoctrination would find support in a Sánchez government ‘drifting to authoritarianism’ (ibid: 155), allegedly complicit with this agenda due to the ‘socialist and globalist’ character of its policies (ibid: 21, 31, 63, 99, 115). Therefore, ‘more than any previous government,’ Sánchez and his government personify to Vox a ‘direct enemy’ of the development and prosperity of the nation (ibid: 47) and, therefore, cannot be trusted.

‘Spain’—i.e., the nation—takes a central role and replaces ‘the people’ in Vox’s discourse. ‘Spain’ is an alternative ‘empty signifier’ (Laclau, 2015); however, it is still in opposition to the elite, serving the same function and combining an idea of ‘the people’. Both ‘socialists and their allies’ are not only hinted to be corrupt (Vox, 2023: 19) but also traitors (ibid: 15) of Spain and ‘the honorable Spaniards.’ There is, thus, a nativist, exclusionary, and righteous notion of ‘the people’—‘the honorable Spaniards’ of ancestral lineage or ‘the virtuous Spaniards’ [los españoles de bien], as Abascal had also called them in 2019 (Público, 20 March 2019)—underlying Vox’s idea of ‘Spain.’

‘Uncontrolled’ and ‘illegal’ immigration (Vox, 2023: 21, 63) are prominent buzzwords in the party’s repertoire. The link between immigration and criminality is clearly stated in the causality established between ‘the uncontrolled arrival of millions of illegal immigrants’ and the ‘suffering’ of ‘Spanish families,’ a consequence of the ‘globalist policies’ promoted by Sánchez’s government, leading to ‘insecurity and the degradation of their neighborhoods’ (ibid: 99). Vox lays out its proposals in contrast to a despised ‘multicultural model,’ of which Belgium, France, and the United Kingdom are given as the most alarming examples. The party claims to support, therefore, ‘a controlled, legal immigration, adapted to Spain’s needs,’ prioritizing newcomers with ‘the ability and will to integrate’ (ibid: 99); more concretely, those coming from a nostalgically fantasized transnational space to which Vox calls the ‘Iberosphere.’ These newcomers are not referred to as simply immigrants but rather as ‘citizens arriving from the nations sharing the language and important ties of friendship, history and culture with Spain’ (ibid: 101). It is, thus, the nostalgic recalling of past imperial relations that makes a specific type of immigrant congruent with Vox’s nationalist idea of Spain, as these immigrants are redeemed by a notion of shared culture and ancestry via past colonization. They can even be understood as part of the historic ‘nation’ exalted by the party, for ‘Spain cannot renounce to being the epicenter of this brotherly community [the Iberosphere] of free, sovereign nations’ (ibid: 141). This position reclaims, thus, a glorious historical past evoking the ‘achievements and feats of our national heroes within and beyond our borders’ (ibid: 17). Such a selective memory emphasizes, of course, ‘Spain’s contribution to universal civilization and history’ and it is, moreover, perceived as essential to the diffusion and protection of national identity, which is threatened yet again by ‘the extreme left’s liberticide agenda’ and a compliant Sánchez government (ibid: 141).

Although Vox does not express any views on emigration at the national level, its concern with social and territorial inequalities vis-à-vis an emptying process of ‘the rural Spain’ says something of its stance regarding regional emigration, fitting into a broader narrative of ‘the emptied Spain’ [la España vaciada]. By using such an expression, Vox not only nostalgically reimagines a past ‘rural Spain’ and a more prosperous hinterland but also attributes agency to its decline and depopulation, imposed by Sánchez’s ‘anti-countryside policies’ (Vox, 2023: 147) and implicitly furthered by the political blackmail of independentist movements, as they tend to focus on affluent, coastal regions. Vox’s answer is to ‘repopulate the rural Spain,’ namely through policies aimed at incentivizing the youth to stay and boosting the rural economy as well as the birth rate (ibid: 148–152). The ‘rural Spain’ is both literal and figurative: the countryside gives Spain ‘produce sovereignty’ and is the last bastion of tradition in a conservative longing for a past untainted by progresismo and ‘globalizing ideologies.’

In its defense of (a notion of) Spain, its identity, and traditional values, Vox establishes an equivalence between the party and ‘the nation’ (Fernández Riquelme, 2020) through the nostalgic recalling of a glorious past, often in contrast to the present situation brought about by a harmful government complicit with internal and external ‘enemies of Spain.’ Although not openly anti-EU, Vox proposes ‘another vision of Europe’ that comprises ‘free, sovereign nations,’ claiming, moreover, a cultural affinity and shared interests in the context of the Southern European region specifically (Vox, 2023: 133–135). There is, thus, the underlying idea that ‘the nation’ has been wronged, both internally and abroad, and that, informed by a former glory, there is something to be restituted to Spain against present forces seeking its political, economic, and moral decline, thus vindicating their main victim, ‘the honorable Spaniard.’

Discussion and conclusion

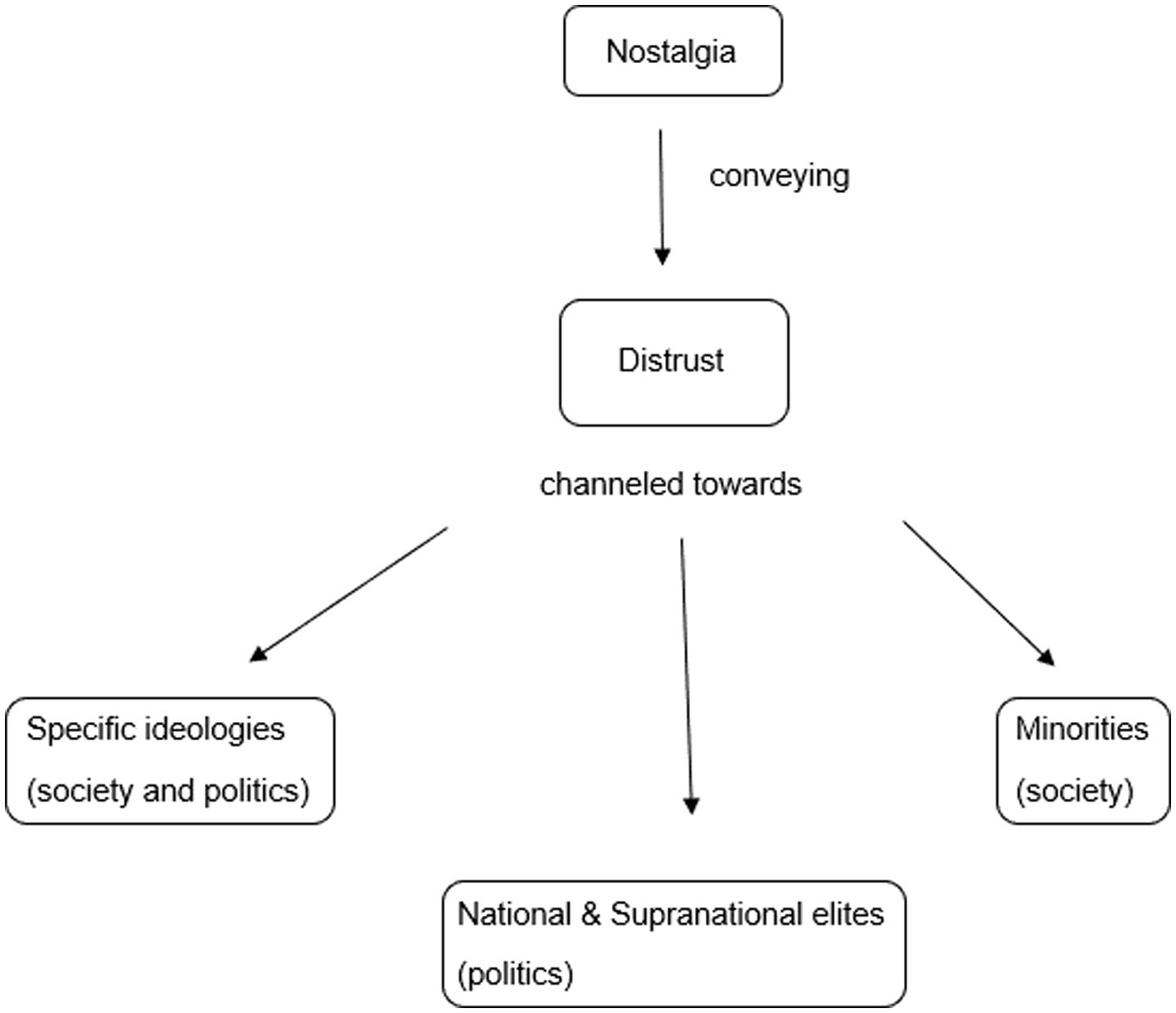

By proposing a skewed view of what was—the society, the country, and its might—PRR parties propose a political program for what should become in the future, informed by a nostalgic recalling of the past. Absolving the ‘righteous’ people for the perceived evils plaguing the country, PRR parties put the blame on elites and their perceived allies, internal and external enemies of the people they claim to represent. The populist people-centered view focuses on a narrow, exclusive national group (the ‘Italian good people,’ the ‘virtuous Portuguese,’ and the ‘honorable Spaniard’), victimized by national and/or supranational elites, ‘globalizing’ agendas, and ‘woke extreme-left’ ideologies, as well as othered minorities. Distrust comes through nostalgic appeals to the people against an elite for the return to a glorious era and the restitution of national dignity. Figure 1 shows how we identify a specific narrative strategy in these PRR parties’ manifestos: while we identify terms related to the feeling of nostalgia and distrust, nostalgia is used in the manifestos to specifically convey distrust that is channeled towards specific receivers. A specific narrative aimed at glorifying what society was in the past enables distrust channeled towards political actors (national and supranational elites), political and societal movements (ideologies), and specific groups within society (minorities). Nostalgic narratives thus play into fears of what is characteristic of today’s society—considered as new—contrasting with an imagined society of the past.

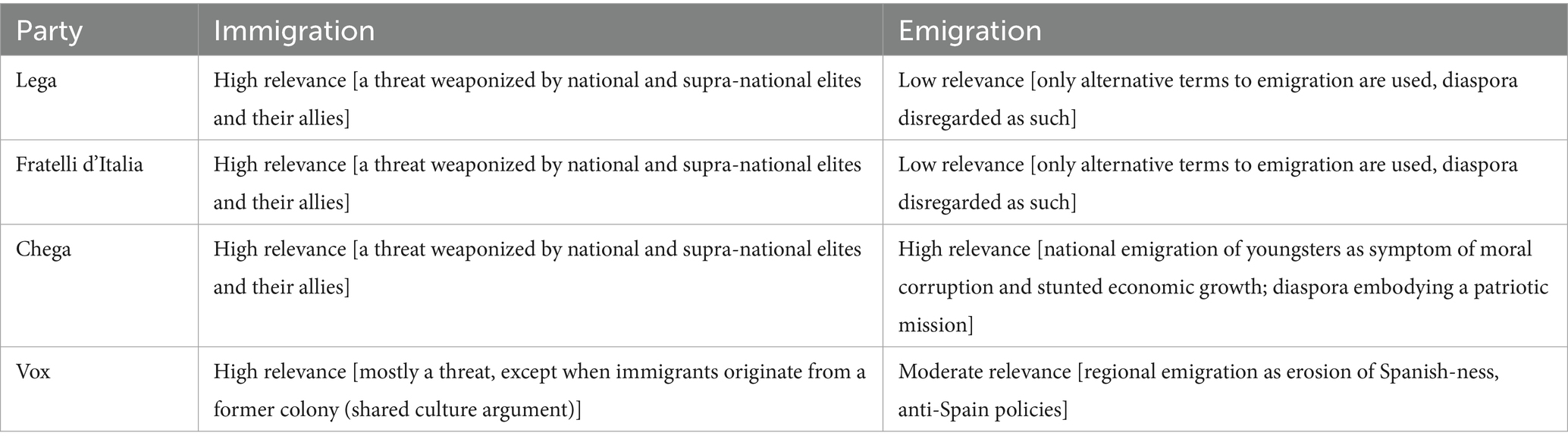

We focus on the topic of mobility to understand the nostalgia narrative framework used by Southern European PRR parties as a device in dialogue with and an instrument to reinforce distrust. Indeed, all four political manifestos under analysis present opposition to immigration by identifying the type of immigration (‘uncontrolled,’ ‘illegal,’ ‘massive,’ ‘that does not want to integrate’) allowed by national or supranational elites and their ‘ideological allies’ as a threat to the nation and the people. Therefore, immigration fits the nostalgic narrative as a ‘threat’ to the national identity informed by past feats and glory, to criticize a decline intertwining morality and ethno-demographics—constructing, thus, the idea of a righteous, superior national against a foreign, backward other who is jeopardizing the former’s safety, traditions, values, and ethnic majority. Furthermore, the narrative surrounding immigration prompts distrust of elites and their ‘ideological allies,’ not only due to the agency that is attributed in the context of this phenomenon but also through a conspirative notion that such elites purposedly ignore or neglect the popular will, thus failing to represent the national majority’s view on the topic. In the Italian examples, both in Lega’s and FdI’s 2022 manifestos, immigration is presented as a strictly negative phenomenon as it forces people to leave their country of origin due to economic struggles and, more importantly, creates a state of emergency in Italy. Both parties declare themselves ready to accept a specific type of immigration that they define as ‘qualified, useful and necessary for the country’s development’ as opposed to an ‘illegal’ immigration. There is no mention whatsoever of Italian past colonial projects and how these might affect migration routes today, or the relationship with former Italian colonies. Immigration is presented as a current, disruptive phenomenon, which is not linked to any other phenomenon if not with criminality and terrorism. Lega and FdI thus completely invisibilize legacies of what could be defined as an Italian empire and its colonial endeavors, which differs from the Spanish and Portuguese PRR parties. Recalling the imagined space of a former empire allows Vox in its 2023 manifesto to reconcile a specific type of immigrants with the party’s idea of ‘nation’ through a shared culture and language. CH, however, does not make the same exception for those coming from former Portuguese colonies. The party even suggests the revoking of the mobility agreement between Portugal and these countries, congruent with its position on the ‘injustices’ of the decolonization process to the white (−majority) Portuguese returnees [retornados] upon the independence of former African colonies. Although exceptions to othering processes may apply according to the parties’ selective recalling of the national past and view on historical experiences, such as those of colonization and decolonization, their overarching nostalgic narrative on immigration is similar. The four manifestos, while at times identifying a specific type of immigration that they consider acceptable, generally portray the phenomenon as a threat to ‘the people,’ identifying the culprits who are seeking the downfall of the nation (i.e., center-left governments and/or the EU, ‘globalizing’ agendas and ‘woke extreme-left’ ideologies).

It is on emigration that these parties’ manifestos presented more variation in the narrative adopted. While Lega and FdI mention the topic as part of a nostalgic grand narrative, they do so by mentioning it with alternative terms, such as ‘brain-drain’ or the ‘threat of de-population,’ while never mentioning explicitly emigration or referring to a more recent Italian diaspora. The two parties plan to attract Italians abroad by giving benefits upon their return as if they believed they are simply set to return to the homeland: these people are never defined as migrants or emigrants but rather as Italians abroad, specifying through this denomination that it is Italy these people belong to. The Italian enormous diaspora is as well selectively ignored in the narrative: the Italians abroad will come back to Italy and this is when they will matter to these parties again. Until then, they are not mentioned nor considered. Similarly, Vox does not mention the issue of national outward migration specifically, but emigration from the countryside to the city or between autonomous communities is included implicitly, in the context of a broader narrative on ‘the rural Spain’ as an ‘emptied Spain.’ This narrative is also nostalgic in the idealization of ‘rural Spain’ as a primary and primitive resource, a stronghold of traditions and values—of Spanish-ness—thus reinforcing distrust of an elite (personified by Sánchez and his government) by blaming it for depopulation due to ‘anti-countryside’/anti-Spain policies. CH has perhaps the most elaborate inclusion of emigration into a broader nostalgic narrative. On the one hand, CH sees emigration as an inevitable ‘social catastrophe’ for a Portuguese youth that is supposedly less free than their parents and grandparents were, because of a perversion of the notion of freedom through which national elites promote moral corruption and inhibit economic prosperity. On the other hand, the party exalts the diaspora and its moral fiber, discursively integrating the millions of Portuguese around the world into a notion of ‘virtuous Portuguese,’ the people CH claims to represent. The party does not necessarily call (although it encourages) the Portuguese emigrant to return as part of a patriotic mission; they present an economic, numeric, and moral advantage to Portugal from abroad, as a sort of post-imperial expansion by other means. CH’s nostalgic narrative on emigration binds together the longing for a better past (the times lived by ‘parents and grandparents’) and the nostalgic recalling of expansion as an asset to the country and a trait of Portuguese-ness (Table 3).

Emigration seems, thus, to be a topic shaped by specific ideological and historical legacies of the past, while immigration is more consistently placed within a narrative of threat against ethnic homogeneity posed by powerful and purposeful anti-patriotic elites. More broadly, one can say that the challenges—a shrinking national ethnie and erosion of those deemed values of the nation—and the culprits—neglectful or conspiring elites—are the same. When identifying such challenges and culprits, these parties infuse moral content and a comparison with a better past into their rhetoric. While distrust represents a central emotion in populist discourse, through this piece, we show how nostalgia helps convey this emotion channeled toward specific actors in society. It is through nostalgic discourse that PRR parties are able to build a distrust-framing narrative on both inward and outward mobility. Future research would need to delve deeper into the role of emotions in political discourse, underlining how strategic uses of emotions make discourses more appealing to and successful among specific audiences.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

AM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the nccr - on the move, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant numbers 51NF40_205605 and 51NF40_182897.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Greece is excluded due to its distinct political trajectory, where distrust and nostalgia have primarily fueled left-wing populism rather than a sustained PRR presence (Pappas, 2013). Unlike Italy, Spain, and Portugal, Greek nostalgia often evokes resistance or victimhood narratives rooted in Balkan and Orthodox traditions, not authoritarian nationalism (Mazower, 2000). Additionally, Greece’s extreme economic collapse and prolonged IMF oversight created a unique crisis context (Featherstone, 2011), making direct comparison with these Southern European PRR parties – where nostalgia revives national strength and distrust tends to target democratic elites and institutions – potentially less analytically coherent.

2. ^The ideology of gender identity is represented, according to both radical right parties, by the Ddl Zan, a bill which took the name of the deputy of the Partito Democratico (Italian left), Alessandro Zan, and which proposed specific measures to tackle homophobia and sexism in the country. Both parties promise in several parts of the manifestos to firmly oppose the Ddl Zan, the symbol of an ‘extremist LGBTQ+ ideology,’ and all measures which would seem to go in the same direction.

3. ^The ‘othering’ of the Roma community was present in Ventura’s discourse even when he was still a member of PSD, which is presently the country’s ruling party. As a candidate to mayor in Loures, Ventura made several discriminatory statements against the community in the 2017 local elections. After a public struggle against the party leadership in 2018, Ventura left his office as local councilor [autarca] in Loures and the party, creating CH shortly after. The Roma community was, since 2019, consistently singled out as one of the enemies of the ‘virtuous Portuguese’ in CH’s discourse, continuing to be a hot topic during the 2021 presidential campaign and, to a lesser degree, in the 2022 legislative campaign.

References

Abts, K., and Rummens, S. (2007). Populism versus democracy. Polit. Stud. 55, 405–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00657.x

Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., and Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comp. Pol. Stud. 47, 1324–1353. doi: 10.1177/0010414013512600

Albertazzi, D., Giovannini, A., and Seddone, A. (2018). “No regionalism please, we are Leghisti !” the transformation of the Italian Lega Nord under the leadership of Matteo Salvini. Reg. Federal Stud. 28, 645–671. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2018.1512977

Albertazzi, D., and McDonnell, D. (2008). Twenty-first century populism. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Alekseenkova, E. S. (2022). Transformation of right-wing populism in Italy in 2018−2022: from Sovereignism to patriotism. Her. Russ. Acad. Sci. 92, S667–S674. doi: 10.1134/S1019331622130123

Aranda Bustamante, G., and Escribano, R. (2022). Las múltiples hibridaciones del posfranquismo populista de Vox. Desafíos 34:1.

Arditi, B. (2004). Populism as a spectre of democracy: a response to Canovan. Polit. Stud. 52, 135–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2004.00468.x

Baro, E., and Jenssen, A. T. (2024). Beyond the cultural backlash: exploring diverse pathways to authoritarian populism in Europe. Democratization 32, 350–372. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2024.2371453

Bertossi, C., Duyvendak, J. W., and Foner, N. (2022). Introduction: nativism and nostalgia. Temporalities in the politics of race and ethnicity in Europe and the US. Appart. Altérités 2:282. doi: 10.4000/alterites.282

Bertsou, E. (2019). Rethinking political distrust. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 11, 213–230. doi: 10.1017/S1755773919000080

Bickerton, C., and Accetti, C. I. (2017). Populism and technocracy: opposites or complements? Crit Rev Int Soc Pol Phil 20, 186–206. doi: 10.1080/13698230.2014.995504

Biscaia, A., and Salgado, S. (2022). “Placing Portuguese right-wing populism into context: analogies with France, Italy, and Spain” in Contemporary politics, communication, and the impact on democracy. (Eds.) D. Palau-Sampio, G. López García, and L. Iannelli (IGI Global), 234–255.

Bøggild, T. (2020). Politicians as party hacks: party loyalty and public distrust in politicians. J. Polit. 82, 1516–1529. doi: 10.1086/708681

Bonikowski, B. (2016). Three lessons of contemporary populism in Europe and the United States. Brown J. World Affairs 23, 9–24.

Bonikowski, B., and Zhang, Y. (2023). Populism as dog-whistle politics: anti-elite discourse and sentiments toward minority groups. Soc. Forces 102, 180–201. doi: 10.1093/sf/soac147

Bunting, H., Gaskell, J., and Stoker, G. (2021). Trust, mistrust and distrust: a gendered perspective on meanings and measurements. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:642129. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.642129

Caiani, M., and Graziano, P. R. (2016). Varieties of populism: insights from the Italian case. Italian Polit. Sci. Rev. 46, 243–267. doi: 10.1017/ipo.2016.6

Campanella, E., and Dassù, M. (2019). Anglo Nostalgia: The Politics of Emotion in a Fractured West : Oxford University Press.

Campani, G. (2018). The migration crisis between populism and post-democracy. In Populism and the Crisis of Democracy: Routledge.

Canovan, M. (2002). “Taking politics to the people:populism as the ideology of democracy” in Democracies and the populist challenge. eds. Y. Mény and Y. Surel (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK), 25–44.

Capdevila, A., Moragas-Fernández, C. M., and Grau-Masot, J. M. (2022). Emergencia del populismo en España: marcos metafóricos de Vox y de su comunidad online durante las elecciones generales de 2019. Prof. Inform. 31:17. doi: 10.3145/epi.2022.may.17

Carnegie, Allison, Clark, Richard, and Zucker, Noah. (2024). ‘Global governance under populism: The challenge of information suppression’. World Politics, February. Available online at: https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/122438/ (Accessed August 14, 2024).

Chamusca, P. (2024). Discontent, populism, or the revenge of the ‘places that Don’t matter’? Analysis of the rise of the far-right in Portugal. Societies 14:80. doi: 10.3390/soc14060080

Chatterjee, P. (2020). I am the people. Reflections on popular sovereignty today. New York: Columbia University Press.

Chega. (2024). Limpar Portugal. Available online at: https://partidochega.pt/index.php/2024legislativas_programa/. (Accessed August 2, 2024).

Chryssogelos, A., Giurlando, P., and Wajner, D. F. (2023). “Populist foreign policy in southern Europe” in Populist foreign policy: Regional perspectives of populism in the international scene. eds. P. Giurlando and D. F. Wajner (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 63–88.

Couperus, S., Tortola, P. D., and Rensmann, L. (2023). Memory politics of the far right in Europe. Eur. Politics Soc. 24, 435–444. doi: 10.1080/23745118.2022.2058757

Csehi, R., and Zgut, E. (2021). “We won’t let Brussels dictate us”: Eurosceptic populism in Hungary and Poland. Eur. Politics Soc. 22, 53–68. doi: 10.1080/23745118.2020.1717064

Da Silva, F. C., and Salgado, S. (2018). ‘Why no populism in Portugal?’ In M. C. Lobo, Silva, F. C.Da, J. P. Zúquete (Eds.), Changing societies: Legacies and challenges. Vol. 2. Citizenship in crisis. pp. 249–268. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais

de Vries, Catherine, and Hoffmann, Isabell. (2018). ‘The Power of the Past How Nostalgia Shapes European Public Opinion. Eupinions #2018/2’. Other. 2018. Available online at: https://aei.pitt.edu/102425/ (Accessed August 14, 2024).

Dennison, James, and Mendes, Mariana. (2019). When do populist radical right parties succeed? Salience, stigma, and the case of the end of Iberian “exceptionalism”. SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY.

Devine, Daniel, Gaskell, Jennifer, Jennings, Will, and Stoker, Gerry. (2020). Exploring trust, mistrust and distrust.

Di Matteo, D., and Mariotti, I. (2021). Italian discontent and right-wing populism: determinants, geographies, patterns. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 13, 371–397. doi: 10.1111/rsp3.12350

Donà, A. (2022). The rise of the radical right in Italy: the case of Fratelli d’Italia. J. Mod. Ital. Stud. 27, 775–794. doi: 10.1080/1354571X.2022.2113216

Elçi, E. (2022). Politics of nostalgia and populism: evidence from Turkey. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 52, 697–714. doi: 10.1017/S0007123420000666

Elgenius, G., and Rydgren, J. (2022). Nationalism and the politics of nostalgia. Sociol. Forum 37, 1230–1243. doi: 10.1111/socf.12836

Enríquez, González, and del Carmen, María. (2017). The Spanish Exception: Unemployment, Inequality and Immigration, but No Right-Wing Populist Parties. Aailable online at: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14468/11553.

Erisen, C., Guidi, M., Martini, S., Toprakkiran, S., Isernia, P., and Littvay, L. (2021). Psychological correlates of populist attitudes. Polit. Psychol. 42, 149–171. doi: 10.1111/pops.12768

Farrand, B., and Carrapico, H. F. (2021). “People like that cannot be trusted”: populist and technocratic political styles, legitimacy, and distrust in the context of Brexit negotiations. J. Contemp. Eur. Res. 17, 148–165. doi: 10.30950/jcer.v17i2.1186

Featherstone, K. (2011). The JCMS annual lecture: the Greek sovereign debt crisis and EMU: a failing state in a skewed regime. J. Common Market Stud. 49, 193–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02139.x

Fernández-García, B., and Valencia-Sáiz, Á. (2023). “Chapter 10 populism in southern Europe” in Democracy fatigue: An east European Epidemy. ed. C. García-Rivero (Central European University Press), 215–239.

Ferreira, C. (2019). Vox como representante de la derecha radical en España: un estudio sobre su ideologia. Re. Española de Ciencia Política 51, 73–98. doi: 10.21308/recp.51.03

Fieschi, C., and Heywood, P. (2004). Trust, cynicism and populist anti-politics. J. Polit. Ideol. 9, 289–309. doi: 10.1080/1356931042000263537

Franzé, J., Fernández-Vázquez, G., Franzé, J., and Fernández-Vázquez, G. (2022). El postfascismo de Vox: un populismo atenuado e invertido. Pensamiento al margen: revista digital sobre las ideas políticas 16, 57–92.

Fratelli D'Italia. (2022). Pronti a Risollevare l'Italia con il nostro Programma. Programma Fratelli D'Italia – Elezioni 2022 (programmafdi2022.it) (Accessed July 30, 2024).

Frischlich, L., Clever, L., Wulf, T., Wildschut, T., and Sedikides, C. (2023). Digital memory and populism| populists’ use of nostalgia: a supervised machine learning approach. Int. J. Commun. 17:25.

Gaston, S., and Hilhorst, S. (2018). At home in one’s past: Nostalgia as aCultural and political force in Britain, France and Germany. Mexico City: Demos.

Grignoli, D., D’Ambrosio, M., and Boriati, D. (2024). Vulnerability and inner areas in Italy—“should young stay or should young go”? A survey in the Molise region. Sustainability 16:359.

Grigoriadis, I. N. (2020). For the people, against the elites: left versus right-wing populism in Greece and Turkey. J. Middle East Afr. 11, 51–64. doi: 10.1080/21520844.2020.1723157

Hameleers, M. (2020). We are right, they are wrong: the antagonistic relationship between populism and discourses of (un)truthfulness. DisClosure J. Soc. Theory 29:11. doi: 10.13023/disclosure.29.11

Havlík, V. (2016). Populism as a threat to liberal democracy in East Central Europe. In Challenges to Democracies in East Central Europe Routledge, 36–55.

Heyne, L., and Manucci, L. (2021). A new Iberian exceptionalism? Comparing the populist radical right electorate in Portugal and Spain. Polit. Res. Exchange 3:1989985. doi: 10.1080/2474736X.2021.1989985

Imran, S., and Javed, H. (2024). Authoritarian populism and response to COVID-19: a comparative study of the United States, India, and Brazil. J. Public Aff. 24:e2898. doi: 10.1002/pa.2898

Innerarity, C., and Giansante, A. C. (2025). National Populism and religion: the case of Fratelli d’Italia and Vox. Religion 16:200. doi: 10.3390/rel16020200

Insero, Martina. (2022). Emotional narratives. Populism and Nostalgia in Europe. Available online at: https://iris.uniroma1.it/handle/11573/1657206. (Accessed August 14, 2024).

Jagers, J., and Walgrave, S. (2007). Populism as political communication style: an empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium. Eur J Polit Res 46, 319–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

Kamenova, D., and Pingaud, E. (2017). “Anti-migration and islamophobia: Web populism and targeting the “easiest other”” in Populism and the Web. (Eds.) M. Pajnik and B. Sauer (Routledge), 108–121.

Kešić, J., Frenkel, S. C., Speelman, I., and Duyvendak, J. W. (2022). Nativism and nostalgia in the Netherlands. Sociol. Forum 37, 1342–1359. doi: 10.1111/socf.12841

Kinnvall, C. (2018). Ontological insecurities and postcolonial imaginaries: the emotional appeal of populism. Humanit. Soc. 42, 523–543. doi: 10.1177/0160597618802646

Korvela, P.-E., and Vento, I. (2023). “Suspicious minds: towards a typology of political distrust” in Between theory and practice: Essays on criticism and crises of democracy. eds. E. Lagerspetz and O. Pulkkinen (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland), 37–64.

Küppers, R. (2024). The far right in Spain: an “exception” to what? Challenging conventions in the study of populism through innovative methodologies. Europ. J. Cult. Polit. Soc. 11, 517–557. doi: 10.1080/23254823.2024.2321905

Laclau, E. (2015). La guerre des identités: Grammaire de l’émancipation (C. Orsoni, Trad.). Éditions La Découverte.

Lama, A. C., Pereiro, S. L., and Suárez, B. F. (2025). A new wave of Spanish emigration to France and the United Kingdom: who are the emigrants and why are they moving? Popul. Soc. 629, 1–4.

Lammers, J. (2023). Collective nostalgia and political ideology. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 52:101607. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101607

Lega Nord. (2022). Elezioni Politiche 2022. Programma di Governo. Programma_Lega_2022.Pdf (legaonline.It). (Accessed July 30, 2024).

Lerín Ibarra, David. (2024). ‘Cambios en la estrategia política de Vox tras su irrupción electoral: populismo y búsqueda del voto obrero’, January 5, 27, 42.

Luengo, Ó. G., and Fernández-García, B. (2019). “Campaign coverage in Spain: populism, emerging parties, and personalization” in Mediated campaigns and populism in Europe. ed. S. Salgado (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 99–121.

Magalhães, P. C., and Cancela, J. (2025). Political neglect and support for the radical right: the case of rural Portugal. Polit. Geogr. 116:103224. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2024.103224

Manunta, E., Becker, M., Easterbrook, M. J., and Vignoles, V. L. (2022). Economic distress and populism: examining the role of identity threat and feelings of social exclusion. Polit. Psychol. 43, 893–912. doi: 10.1111/pops.12824

Marchi, R., and Zúquete, J. P. (2024). Far right populism in Portugal: the political culture of Chega’s members. Anál. Soc. 59:e22116.

Marcos-Marne, H., and Sendra, M. (2024). Everything for the people, but trust? Exploring the link between populist attitudes and social Trust in Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 30, 263–279. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12608

Martinico, G., and Monti, M. (2024). Online disinformation and populist approaches to freedom of expression: between confrontation and Mimetism. Liverpool Law Rev. 45, 143–169. doi: 10.1007/s10991-023-09343-9

Mazower, M. (2000). Changing trends in the historiography of postwar Europe, east and west. Int. Labor Working-Class Hist. 58, 275–282. doi: 10.1017/S0147547900003719

Michel, Andreas. (2020). “Cosmopolitanism, populism, and democracy”. in NOTES ON EUROPE. THE DOGMATIC SLEEP. Proc., no. 1 (March). pp. 153–66.

Mora Castro, A. (2023). Populismo nacionalista, inmigración y xenofobia. Cuadernos electrónicos de filosofía del derecho 49, 447–460.

Mudde, C. (2004). The Populist Zeitgeist. Gov. Oppos. 39, 541–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

Mudde, C., and Kaltwasser, C. R. (Eds.). (2012). Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or corrective for democracy?. Cambridge University Press.

Mudde, C., and Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A Very Short Introduction : Oxford University Press.

Newth, G. (2019). The roots of the Lega Nord’s populist regionalism. Patterns Prejud. 53, 384–406. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2019.1615784

Newton, K. (2007). “Social and political trust” in The Oxford handbook of political behavior. eds. R. J. Dalton and H.-D. Klingemann (Oxford University Press).

Nowicka, M. (2018). Cultural Precarity: migrants’ positionalities in the light of current anti-immigrant populism in Europe. J. Intercult. Stud. 39, 527–542. doi: 10.1080/07256868.2018.1508006

Oliveira, M. d. F., and Reis, P. (2023). Portuguese Agrifood sector resilience: an analysis using structural breaks applied to international trade. Agriculture 13:1699. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13091699

Ozzano, L. (2021). “Religion, cleavages, and right-wing populist parties: the Italian case” in A quarter century of the “clash of civilizations” (Routledge).

Pappas, Takis S., and Kriesi, Hanspeter. (2015). ‘Populism and crisis: a fuzzy relationship’. European populism in the shadow of the great recession: 303–325.