- American Studies Program, Boston University, Boston, MA, United States

This essay draws on theories of political philosopher Hanna Pitkin and cultural studies scholar Stuart Hall to consider youth representation in terms of relationships between cultural representation and political representation. I argue that the ways in which youth are represented and misrepresented in cultural discourse and media affects their political representation. After an opening section focused on the problem of cultural misrepresentations of youth, the essay explores concepts of youth and adolescence as they evolved after World War II. The third section assesses the impact of cultural constructs of youth on political representation by reviewing evidence on mainstream media representations of young climate change activists. The essay’s final section analyzes debates related to minimum voting age requirements, and what they suggest about understanding the problem of youth representation.

Introduction

Political philosopher Hanna Pitkin famously compared the concept of representation to “a rather complicated, convoluted, three-dimensional structure in the middle of a dark enclosure.” Continuing the metaphor, Pitkin described different political theories about representation as “flash-bulb photographs of the structure taken from different angles” (1967, p.10). This metaphor aptly expresses the varied conclusions political scientists reach when they train different theoretical lenses on representation. Thus a “photo” taken from the “angle” of how political institutions marginalize youth will yield a different view than a case study exploring the extent to which younger politicians represent youth interests. Pitkin’s analysis highlights how the conceptual shapes the real. Political institutions and behaviors aren’t pulled out of a hat; they emerge from how people “see themselves and their world, and this in turn depends upon the concepts through which they see” (Pitkin, 1967, p. 1). In her foundational 1967 The Concept of Representation, Pitkin defines and analyzes four conceptual “angles” used to understand political representation (formalist, symbolic, descriptive and substantive), each with its “particular and peculiar assumptions and implications” (p. 226). These theoretical assumptions cast different light on the structure of representation, and lead to different conclusions.

Nearly 60 years after the publication of The Concept of Representation, Pitkin’s work remains essential to theoretical understanding of representation. Yet differences in understandings of representation among the theoretical approaches Pitkin discusses are relatively minor compared to those between social science scholars and those in the humanities and cultural studies. Using Pitkin’s definition of representation as “making present again,” (p. 8) the former ground the concept in “the activity of making citizens’ voices, opinions, and perspectives ‘present’ in public policy making processes” (Dovi, 2018). Closely linked to problems and processes of liberal democracies, such political definitions of representation result in research projects that “trace the normative basis of liberal representation, sketch the development of these institutions as manifested in Western democracies, describe and assess the extent to which their mechanisms work effectively and evaluate potential threats liberal democracy currently faces” (Rohrschneider and Thomassen, 2020, p. 4). Yet political science approaches to representation, tend, as sociologist Eric Selbin writes, to “not look kindly” on the narratives, visual images, and textual evidence on which cultural studies relies. Such non-empirical evidence is “most commonly disparaged with the term ‘mere’ and referred to as ‘description,’ ‘journalism,’ or most damning of all, ‘history’ (Selbin, 2010, p. 30). Certainly factors other than cultural representation affect youth political representation. But discourse and popular images of youth, as the essay will discuss, are frequently associated with immaturity or violence. Disregarding the role of such cultural representation both overlooks an important facet of the problem of youth underrepresentation, and risks reifying cultural ideas about youth as fact.

This paper offers an initial attempt to bridge a gap between methodologies and emphases of cultural theorists and political scientists. As a conceptual piece, it does not meet Pitkin’s call for “systematic study and clarification” of discourse surrounding the word representation and “the contexts in which it can be used” (p. 7). It does seek to broaden those contexts to consider relationships between cultural and political representations of youth.

To be sure, Hanna Pitkin’s discussion of symbolic representation considers narratives and visual images. In the chapter “‘Standing For’: Symbolic Representation,” Pitkin makes the point that “To say something symbolizes something else is to say that it calls to mind, and even beyond that evokes emotions of attitudes appropriate to the absent thing.” Her discussion, however, largely revolves around political symbols, such as flags, and the use of emotion and symbols by leaders, often to undercut democratic representation. Thus Pitkin cites the Nazi lawyer Otto Koellreutter’s analysis of Hitler’s power as rooted in an ability to treat the people as an “instrument on which the political leader must play. If he elicts the right tones from this instrument….he receives thereby the indispensable foundation for his activity of political leadership” (p. 108). In this conception, political leaders use symbols to appeal to and gain power. Thus the symbolic power of a border wall has become a propaganda weapon for Donald Trump, helping him to gain power to enact anti-immigrant policies, and build the literal wall.

However, as Stuart Hall explains in Representation, in the methodology of cultural studies, texts are not simply symbolic tools, or illustrative examples. Representation, Hall writes,

Can only be properly analyzed in relation to the actual concrete forms which meaning assumes, in the concrete practices of signifying, ‘reading’ and interpretation; and these require analysis of the actual signs, symbols, figures, images, narratives, words and sounds--the material forms--in which symbolic meaning is circulated (2013, p. xxv).

Visual and written texts, and discourse itself, are, to the cultural studies scholar, what election results, statistical models, surveys and case studies are for the political scientist. Thus cultural theorists, following Stuart Hall’s seminal work, focus on representation as portrayal (implicit or explicit), transmitted culturally, and particularly via mainstream media, such as Hollywood film. Hall explained this definition in Representation, first published in 1997.

In part, we give things meaning by how we represent them—the words we use about them, the stories we tell about them, the images of them we produce, the emotions we associate with them, the ways we classify and conceptualize them, the values we place on them (2013, p. xix).

Whereas political scientists reach conclusions based on empirical data, cultural studies scholars use texts, such as works of literature, films, or visual art. These cultural materials are shaped into a story. Hall uses a painting of the Biblical story of Cain’s murder by Abel to demonstrate this understanding of representation. “The figures in the painting stand in the place of, and at the same time, stand for, the story of Cain and Abel.” (p. 16) That story of Cain and Abel then becomes a larger narrative about human nature and human societies.

The divergent views of political science and cultural studies are reflected in the two main dictionary definitions of representation as “a person or organization that speaks, acts, or is present officially for someone else” and “the way that someone or something is shown or described” (Representation definition, n.d.; Rehfeld, 2011). In terms of youth representation, these dual meanings suggest the importance of understanding not just how political institutions represent youth, but how cultural meanings ascribed to youth interface with and impact youth political representation.

This essay focuses on that interface, tackling the question of why political institutions have a poor track record in representing youth by considering relationships between cultural representation and political representation. These two disciplinary approaches to understanding youth representation largely remain apart, disjoint sets of a non-intersecting Venn diagram. I argue that bringing political science and cultural studies together in an interdisciplinary analysis of youth representation yields important insights. After a first section focused on theories of cultural representation of youth, the essay moves to outlining dominant cultural ideas about youth and adolescence as these concepts evolved in the US post-World War II. Next, I analyze the ways cultural constructs regarding youth impact political representation by examining attitudes toward young climate change activists. In the final discussion portion of the essay, I consider broader implications of the intersections of cultural and political youth representation, focusing on the voting age, and the potential of understanding youth underrepresentation as a civil rights issue.

The problem of youth (mis)representation

Despite methodological differences, political science and cultural studies approaches to youth representation have a commonality. Both disciplines typically see youth as more misrepresented than represented, emphasize the ways in which young people are inadequately or inappropriately represented by dominant systems, and seek to understand the implications of such exclusions. An extensive body of empirical social science scholarship on youth political participation has documented the extent of the problem of youth underrepresentation, reasons for it, and avenues to improve youth civic engagement and political representation (Kitanova, 2019; Torres and Río, 2013; Stockemer and Sundström, 2022; Antkowiak, 2024; Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), 2025). Studies point to the key role of what Stockemer and Aksel Sundström describe as “a vicious cycle of political alienation” in the political disempowerment of young people. While scholars differ on the causes and solutions, that youth are woefully unrepresented in national governments across the globe is clear. Adults under 35 make up less than 10% of members of the 120 parliaments surveyed in a recent study (Stockemer and Sundström, 2022). In the United States, youth fare even worse in political representation. The 119th Congress, sworn in January 6, 2025, is the third oldest in US history, with only one member under 30, and 20 over 80. Millennials constitute nearly a third of the US population, but make up only 15% of the 119th Congress (Murphy, 2025). Representation of other historically marginalized groups has increased in recent years, with the current Congress the most racially and ethnically diverse ever, including a high of 66 Black federal lawmakers (Hatfield, 2025). But while the median age of Congress is decreasing slightly, it remains only about 57 years More, the percent of young elected officials in the US Congress went down nearly 50% from 1981 to 2021 (Stockemer et al., 2023). This underrepresentation of youth has consequences. As legal scholar Jonathan Todres argues, the “exclusion of young people frequently results in children’s interests flying under the radar in the context of political and legal debates” (Todres et al., 2023, p. 425).

Parallel with such examinations of youth underrepresentation in political institutions, scholars in cultural studies have examined representations and misrepresentations of youth in literature, history, popular culture and mass media (Lesko, 2012; Petrone et al., 2014; Christenbury et al., 2009). Such cultural studies analyses begin with the notion that “youth” is a cultural construct, created and contested by and amid dominant systems and institutions. Cultural understandings of young people as individuals and youth as a group are “always contingent on and constituted through social arrangements and systems of reasoning available within particular historical moments and contexts (Petrone et al., 2014, p. 509).” Cultural studies employs this constructivist approach to analyze the ways in which the category youth is “arbitrary and contested,” and “part of a politics of classification” (Bessant, 2020, p. 3). Like political systems, cultural constructs of youth have consequences. Largely, however, cultural images of youth have been seen from the viewpoint of consequences for youth behavior. In particular, the role of popular culture and mass media in making youth subject to rebellious or dangerous behaviors has long been studied, with many of these concluding that “exposure to violence in the media is associated with higher levels of antisocial behavior” (Jamieson and Romer, 2008, p. 233). A 2023 report by the United States Surgeon General (2023) reviewed multiple studies, and found some benefits to youth media exposure, but concluded that there are “ample indicators that social media can have a profound risk of harm to the mental health and well-being of children and adolescents” (p. 4).

It is not the purpose of this essay to engage in debates about the impact of media on youth, such as whether Tiktok should be banned. Those debates, while important, skirt the question of how cultural representations of youth affect political representation. As Stuart Hall argued more generally about representation, the meanings a dominant culture ascribes to marginalized groups “serve the interests of the wealthiest and most powerful members of a society (Campbell, 2011, p. 16).” Cultural representation contains, as Hall noted, the” power to mark, assign and classify;….the power to represent someone or something in a certain way” (2013, p. 249). That this power is based in discourse and symbols makes it no less real (Bastedo, 2012). Edward Said’s classic study of the peoples and cultures Europeans named “the Orient” demonstrates this clearly. Stereotyping and misrepresentation was, as Said wrote, a central means “by which European culture was able to manage—and even produce the Orient politically, sociologically, militarily, ideologically, scientifically, and imaginatively” (Said, 1977, p. 7). As much as military fortifications, cultural concepts which represented the complex civilizations of North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia as inferior, violence prone, and driven by irrational impulse and fanaticism, buttressed European colonialism.

Through this same process, young people, as members of a non-dominant political and social group, become subject to false or stereotyped representations. Such (mis)representation, as Hall writes, “reduces people to a few, simple, essential characteristics, which are represented as fixed by nature.” (p. 247) Thus the Child Welfare League of America, in its definition of “adultism,” describes how cultural concepts contribute to disempowering and disenfranchising youth through representing them “as objects instead of human beings” (Westman, p. 46, Delgado, 2002, p. 6). What Hall and ensuing cultural critics refer to as “signifiers” mark youth in particular ways. For example, as one study of youth depictions in the media found, young people have come to be associated with rebellion and violence, and have “frequently been framed within televised spaces either as belligerent intruders or as a feral underclass” (Banaji and Cammaerts, 2014). Such depictions of youth as violent have continued, despite a lack of empirical evidence supporting that view. As noted in a history of juvenile justice in the US, even as youth had long been associated with violence, by the 1980s, an image arose of certain youth as “superpredators,” allegedly responsible for rising rates of violence.

The emphasis on extreme violence and the rise of the superpredator was based in large measure on fear and repeated images in popular culture of youth as perpetrators of ongoing extreme violence…[despite] data that indicate that in the 21st century, youth crime is on the decline (Short, 2012, p. 7).

This false conception of youth violence, racialized and applied specifically to Black youth, contributed to “tough on crime” US policies that included sentencing youth as young as 14 to life without parole. The punishments included execution until 2005, when the US Supreme Court, in Roper v. Simmons, ruled the juvenile death penalty unconstitutional (Equal Justice Initiative, 2017, p. 13).

Understood in such contexts, the problem of youth political representation can be seen to be connected, at least in part, to the interests of a status quo that seeks to keep youth disempowered, and wields power thorough cultural portrayals. This power is employed not only via specific negative signifiers associated with youth, such as violence and immaturity, but more broadly, through the creation of a monolithic concept of youth “as being supposedly all the same and essentially different from adults” (Alvermann, 2009, p. 19). And while it is now generally accepted that race is a cultural construct, and not biological reality, “this theoretical perspective has been used less frequently to dismantle the ways in which adolescence is represented in both popular discourses and even in social science research” (Gordon, 2009, p. 6). To use Nancy Lesko’s term, youth have been “massified,” so that “descriptions of adolescents in general came to be understood as essential characteristics of each and every adolescent” (Lesko, 2012, p. 76). Though describing women, or racial minorities, in such broad strokes is usually understood as bias, rooted in stereotypes, a monolithic conception of “youth” can be excused as based on developmental biology, appearing to be natural rather than cultural.

The development of modern cultural constructs of youth

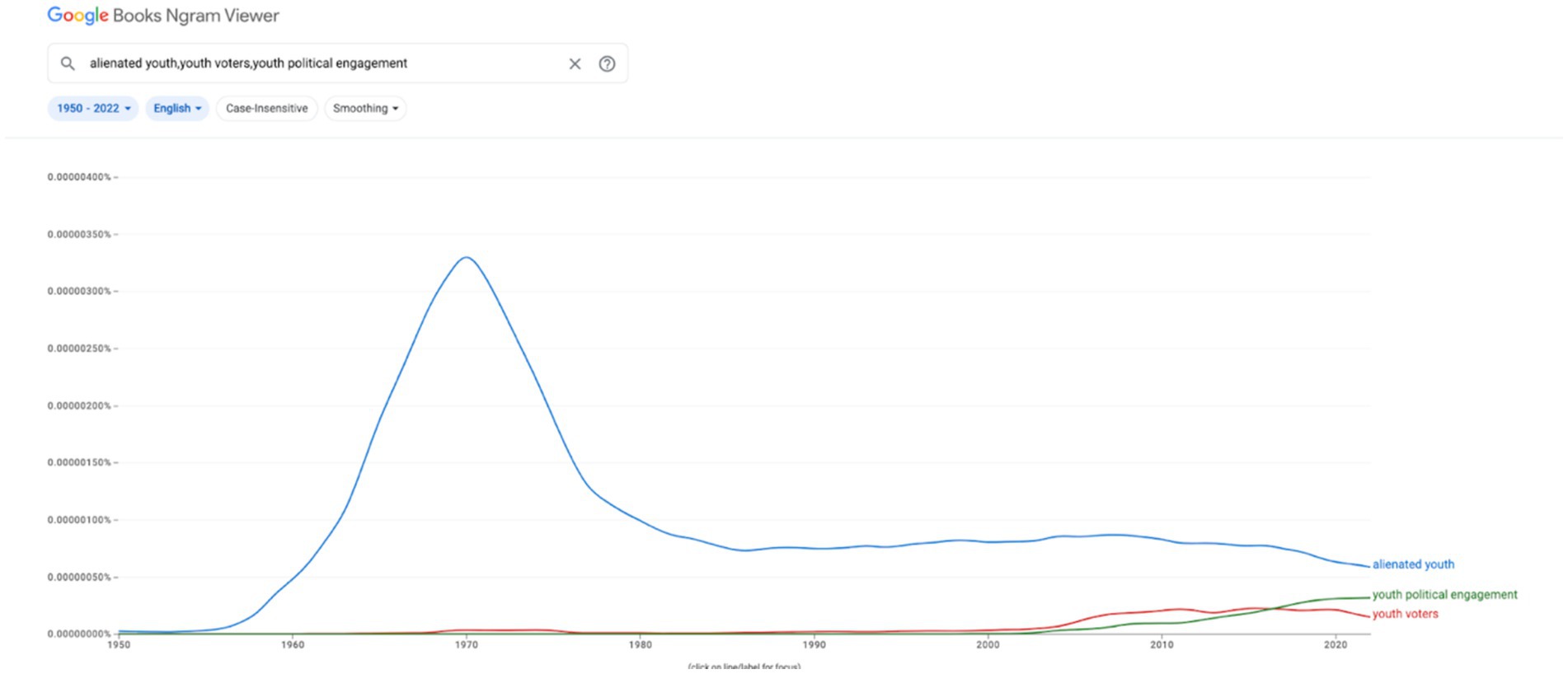

Through much of human history, “youth” was not a distinct cultural concept. Youth, often used synonymously with adolescent, began to take on specific cultural meanings in the early twentieth century, with the development of psychology as an academic discipline and the 1905 publication of G. Stanley Hall’s two volume Adolescence (Arnett, 2006). Hall and other psychologists constructed adolescence as “a particularly fragile state of physical, emotional, moral and intellectual development” (Austin and Willard, 1998, p. 3), with youth conceived as “torn by unmanageable passions, impulsive, rebellious, and given to florid swings of mood” (Esman, 1990, p.22). An association of youth with rebellion, alienation, and violence came to dominate American and to an extent global culture in the mid to late twentieth century. Thus a Google Ngram of books in English published from 1950 to 2022 shows the relative popularity of selected phrases associated with youth (Figure 1). The phrase “alienated youth” is used more commonly than “youth political participation” or “youth voters.” Though associations of youth with politics have become more salient in recent years, the concept of youth as alienated remains evident throughout the decades, with the popularity of the phrase “alienated youth” peaking in 1970.

Political disengagement is a key element of youth alienation as understood in the post-World War II era, as social psychologist Kenneth Keniston discussed in his classic 1960 study of American middle class youth, The Uncommitted: Alienated Youth in American Society.

Most youths approach the wider world, social problems, political events and international affairs with a comparable lack of deep involvement…The vast majority are well informed and uninvolved. Ultimately, most students feel a strong underlying sense of powerlessness which dictates this lack of involvement. Few believe that society could, much less should, be radically transformed; most consider the world complex beyond their power to comprehend or influence it (pp. 397–398).

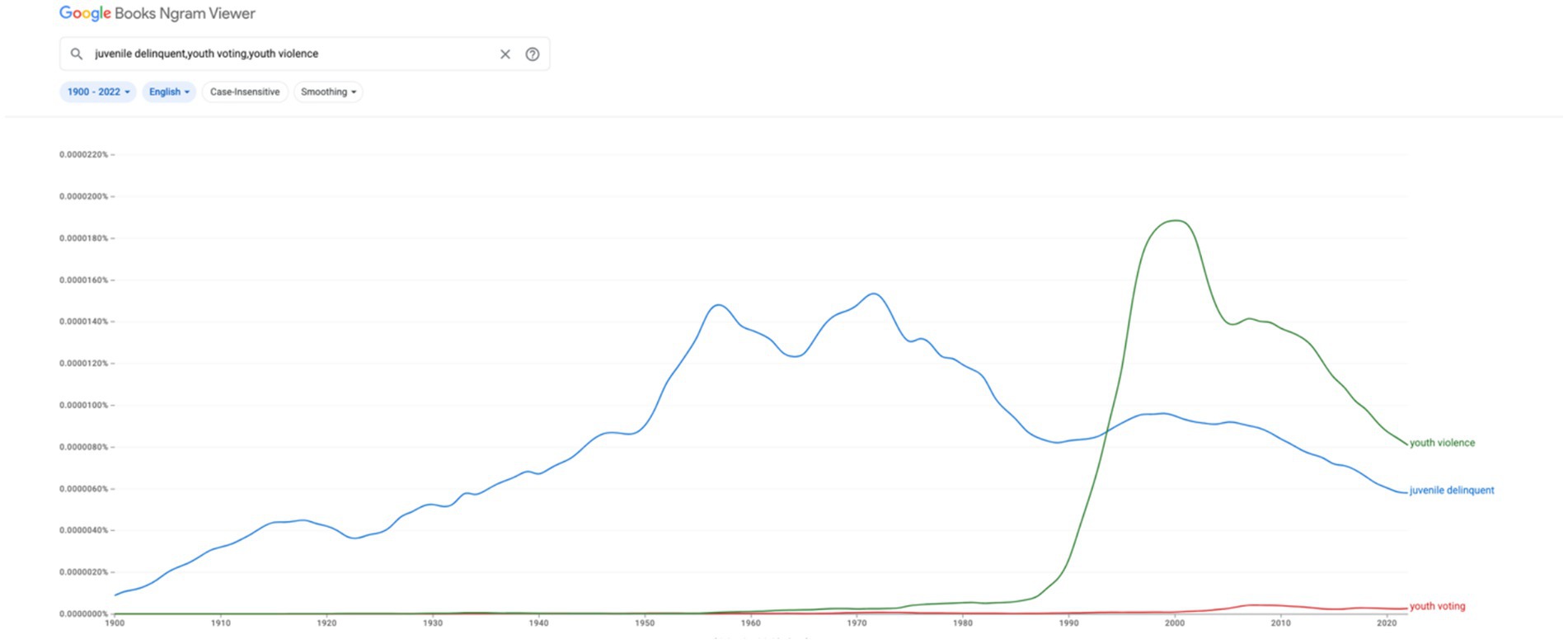

In this framing, youth, while rebellious, as depicted in films such as Rebel with a Cause, or The Blackboard Jungle, were not involved citizens (Golub, 2015). Rather, the dominant cultural representations of youth showed them as “simultaneously malleable and obstinate, a danger to themselves and to others. Individual adolescents or specific groups of young people were presented as social problems, and as either actually or potentially capable of terrible upheaval and trauma for society” (Griffin, 1993, p. 23). This cultural construct of youth as dangerous has grown over time, as exemplified in Figure 2, comparing the frequency of the phrases “youth violence,” “juvenile delinquent,” and “youth voting.”

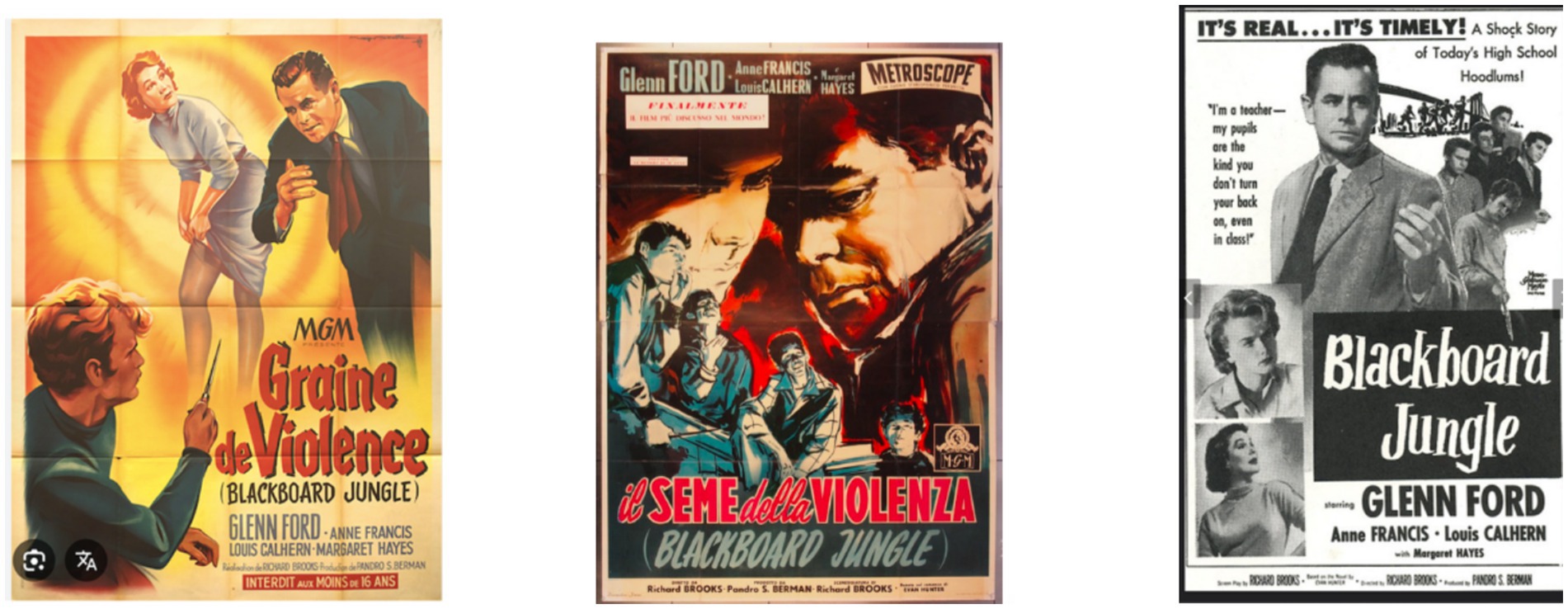

Figure 2. Google ngram comparison of youth violence, juvenile delinquent, and youth voting. Two important cultural documents from the 1950s offer examples of the ways in which “youth” as a group were represented: J.D Salinger’s 1951 novel, Catcher in the Rye, and the 1955 film The Blackboard Jungle. Both present teenagers as anti-social “rebels without a cause,” with Catcher in the Rye more illustrative of representations of youth alienation, and The Blackboard Jungle constructing youth as violent.

As literary critic Joyce Rowe argues, the alienation of Salinger’s teenage protagonist Holden Caulfield is rooted in his status as a “precocious but socially impotent upper-middle-class adolescent who is entirely dependent upon institutions that have failed him” (Rowe, 1992, p. 79). The novel, one critic has noted, might have been called “The Observer in the Rye,” since Holden, despite narrating the novel, shows little sense of agency (Sasani and Javidnejat, 2015; Graham, 2007). Holden is drawn to childhood, epitomized by the use of the children’s song “Catcher in the Rye,” and his close relationship with his sister Phoebe. He sees adults as “phonies,” and adulthood as an unacceptable choice. This bifurcation of child/adult is in keeping with generalizations about adolescence as antithetical to adult maturity, a concept, which, as I discuss later, is used to argue against youth voting. Linked to this, and evident in the range of Holden’s negative behaviors, from fighting, to seeking out a prostitute, is the representation of youth as dangerously antisocial. Nor does Holden Caulfield get out of this place of adolescent angst and alienation. He is stuck in an unhappy, dysfunctional and disempowered state, a condition linked directly to his status as an adolescent.

This cultural concept of mid-twentieth century youth as alienated and disempowered notably did not accord with political realities. At the start of 1960, the same year Keniston’s study of alienated and uncommitted youth was published, four 18-year-old Black men at North Carolina A& T College, and Black women students at nearby Bennett College, organized the first sit-in protest of the modern civil rights era. Two years earlier, Martin Luther King, Jr. praised youth in soaring terms at a youth march for school integration. Dr. King told the student activists:

You, the young people of America, have marched for freedom. Fifty thousand in the fight for a free America…There is a unique element in this demonstration; it is a young people’s march. You are proving that the youth of America is freeing itself of the prejudices of an older and darker time in our history…. Keep marching and show the pessimists and the weak of spirit that they are wrong. Keep marching and do not let them silence you. Keep marching and resist injustice with the firm, non-violent spirit you demonstrated today (King, 1958).

By April of 1960, students in over 70 Southern cities had led sit-ins, leading writer Lillian Smith to pen an essay entitled “Only the Young and the Brave,” and the New York Times to opine, about young civil rights activists, that Americans should “Heed Their Rising Voices.” (Smith, 1960; Sit-ins in Greensboro, 2021). These real young people were neither uncommitted nor violent; they were courageous, responsible citizens seeking to address racial inequality.

The fact that the subjects of The Uncommitted were, like Holden Caulfield, white and middle to upper class men, explains some of the gap between Kenneth Keniston’s findings on youth alienation and the actual engagement of youth in social protests. But it is also evidence of the way dominant cultural representations consciously shaped images and ideas about who youth were, framing them as alienated and anti-social rather than responsible and politically engaged (Cohen, 1997). Thus despite the youth activism evident in anti-war, civil rights, feminist, and gay rights protests, the dominant cultural construct of youth in the second half of the twentieth century became one of retreat to what Tom Wolfe labeled the “Me” generation. This image of the average youth as a “somewhat selfish, extremely hip, and utterly narcissistic individual who is unconcerned about any issue that transcends this immediate vision” (Mackey, 1978, p. 360) is demonstrably untrue of the Black youths who faced fire hoses and arrest in the 1963 Birmingham children’s crusade, or the youth from France, to Mexico, to the US, whose uprisings shut down institutions across the globe in the summer of 1968. Nor is it true of the youth James Baldwin describes in works such as the 1957 short story “Sonny’s Blues,” or the 1963 essay “A Talk to Teachers.” In the former, Baldwin’s teenage Black protagonists are “growing up with a rush” in an ostensibly democratic but structurally racist society where “their heads bumped abruptly against the low ceilings of their actual possibilities (Baldwin, 1957).” In the latter, Baldwin says that were he a teacher, he would tell students that it is up to them to change American society “for the sake of the life and health of the country” and to understand that “the popular culture—as represented, for example, on television and in comic books and in movies—is based on fantasies” that “have nothing to do with reality” (Baldwin, 1963). The views of James Baldwin, Dr. King, Lillian Smith, and youth themselves, however, were marginalized by the power of dominant politics and culture.

To the extent youth activism was acknowledged, it was often depicted as immature rebellion or pathologized as violent juvenile delinquency. Building on Chimamanda Adiche’s influential 2009 Ted Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” the University of Pittsburgh educational theorist Leigh Patel has described how the “single story” of adolescence became “one of raging hormones, rebelliousness, and defiance of authority” (p. 36). Importantly, these late twentieth century cultural constructs of youth did not present them as innocent, but rather, encoded adolescents as dangerous. As cultural critic Henry Giroux writes, “Hollywood and other conduits of media culture capitalized on such fears by constructing youth as both a social threat and a lucrative market. Redefining teen culture as both separate and in opposition to adult society, youth became the embodiment of alienation, anger, and potential danger” (p. 74). These negative cultural representations of youth benefitted the status quo, describing youth as alienated and rebellious rather than rational citizens, and “downplaying the role of systemic inequality and potentially reinforcing rather than overcoming children and young people’s subjugation” (Hartung, 2017). From The Catcher in the Rye to films like The Blackboard Jungle, cultural constructs of youth in the mid to late twentieth century “located [them] within a range of signifiers that largely deny their representational status as active citizens. Associated with coming-of-age rebellion, youth become a metaphor for trivializing resistance” (Giroux, 2022, p. 71), The mass media’s representations of youth thus functioned in part to keep protests, change, and youth political power, at bay.

The impact of Hollywood and other purveyors of popular culture on images of youth was not confined to the United States. In an analysis of the worldwide impact of Hollywood films on depictions of youth, cultural and popular studies writer Adam Golub traces responses to the 1955 film The Blackboard Jungle in Europe and Asia. The film takes place in an New York City high school populated by youth who are at best disrespectful, and at worst dangerous. Students in the film bring knives to school, rob a newspaper van, attempt to sexually assault a teacher, and beat up the main adult character, an army veteran and new English teacher. When MGM released The Blackboard Jungle, they called it a “Drama of Teen-age Terror,” and implicitly sent out warnings about youth with lurid advertisements showing a student cleaning his nails with a switchblade, and warning “They Turned a School Into a Jungle!” The racial and class subtext of these advertisements was also evident in the context of the film’s depiction of a technical high school, with the disruptive students shown to be working class, Black, and Puerto Rican. In one scene, the lead character English teacher visits a wealthier high school, where well-behaved white students, dressed in business attire, stand at attention, singing “The Star Spangled Banner.”

Fueled by Hollywood and American popular culture, these images of youth spread, not only in the United States, but globally. Banned in Japan for being “harmful to juveniles,” and limited to adult audiences in England, Brazil, Chile, Columbia, Cuba, and Holland, the film’s transnational reception is evidence of the ways of which American concepts of youths as alienated and dangerous delinquents “circulated meaningfully, multiplied, and had consequence beyond US borders during the 1950s” (Golub, 2015, pp.2, 3,7). The film’s publicity posters in France, Italy, and Germany, translated the original English title as “seeds of violence,” (Figure 3), suggesting youth as responsible not just for individual acts, but as a group, the root cause of societal violence.

The Blackboard Jungle also points to the ways particular cultural representations of youth became dominant through the power of media. The film’s overall message, communicated by the protagonists, Glenn Ford’s English teacher and Sidney Poitier’s student, a young Black man Ford’s character identifies as a leader, is that even the most problematic youths can be redeemed. Their bad behavior is not depicted as inherent in adolescence, but rather, a product of their era and class. They are, as one teacher puts it, the neglected children of World War II, when fathers were away fighting and mothers employed in defense factories. But those words in defense of youth are drowned out by the loud music, violence, and imagery of the film, as well as its marketing.

Depictions of youth as violent, anti-social deviants made it to the halls of the US Congress, which in 1954 convened a special committee to investigate juvenile delinquency. Senator Robert Hendrickson of New Jersey opened the hearings by calling juvenile delinquency.

“the shame of America.” Hendrickson, who previously had called youth crime and delinquency.

“the fifth horseman of doom,” particularly focused on comic books. The Senator called psychologist Frederic Wertham, author of the anti-comic book screed Seduction of the Innocents, to testify. Wertham’s comments included the sensational claim that “Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry. They get the children much younger” (Hastings, 2022). Decrying the “rising tide of juvenile delinquency,” the Senate committee described its charge as.

Seeking honestly and earnestly to determine why so many young Americans are unable to adjust themselves into the lawful pattern of American society. We are examining the reason why more and more of our youngsters steal automobiles, turn to vandalism, commit holdups, or become narcotic addicts (United States Congress Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 1954).

Importantly, the Senate names the problem as larger than crime statistics. The fear is that youth will not “adjust themselves into the lawful pattern of American society.” This statement can be seen as rooted in resistance to the social change youth were already bringing through their political activism, activism that would increase throughout the 1960s. Seventy years after the United States Congress Senate Committee on the Judiciary (1954) hearings on juvenile delinquency, similar patterns continue to be seen in the ways cultural signifiers of youth impact their political representation. In the next section, I explore the relationship of dominant cultural representations of youth to depictions of young climate change activists.

Youth representation and depictions of climate change activists

In Act Your Age! A Cultural Construction of Adolescence, Nancy Lesko identifies four key concepts associated with representations of young people. These are: youth as not yet adults who exist in a liminal, unfinished, “coming of age” state; youth as controlled by their “raging hormones;” youth as subject to peer pressure, and last, youth seen as a unified group whose age alone calls forth “volumes of information” (Lesko, 2012, pp. 2–4). The actual diversity of young people is reduced to a narrow cultural representation of youth as “troubling teenagers” who are “emotional, confused, controlled by hormones, unstable” (p.107). Young people, notes Lesko, are simultaneously “imprisoned in their time (age) and out of time (abstracted), and they are thereby denied power over decisions or resources” (p. 106). As Lesko and other scholars who have analyzed youth cultural representation argue, it is not accidental that portrayals of youth serve to undercut their political rights and power (Bessant, 2020; Giroux, 2022; Todres, 2022). Cultural representations, conveyed by mainstream media, work in tandem with ideological values and political systems to maintain the status quo.

Qualitative studies of media representations of young climate change activists show this dynamic at work. Thus a 2023 study of Australian media accounts of youth climate change activists concluded, “Mainstream news media has been shown to frame youth climate activists as politically illegitimate by focusing on their ages and lack of authority, indicating their inability to participate in political systems and processes” (Cowan et al., 2023, p. 77). Two different analyses of German press treatments of Fridays for the Futures, the youth-led global movement sparked by then 15-year-old Greta Thunberg’s protests at the Swedish parliament, reached similar conclusions. Lena von Zabern and Christopher Tulloch, using “framing theory” (p. 2) to analyze which aspects of Fridays for the Future protests the German press highlighted, concluded that “two out of every three articles (58/85) undermine the protesters self-agency through direct or indirect disparagement, or by portraying the protesters as exploited by adult agenda,” and “marginalize or de-politicize the protesters’ demands and accusations” (p. 16). German press depictions, von Zabern and Tulloch found, presented youth as illegitimate political actors because of their youth, with a substantial portion of stories fitting what the study authors call the “truancy frame,” in which youth activism was trivialized, coming out of “dubious motives,” (p. 12) and labeled irresponsible. An analysis of a large dataset of Australian media depictions of Fridays for the Future similarly found youth represented as “inauthentic truants,” (Cowan et al., 2023, p. 82) whose participation was not motivated by genuine political concerns, but an immature desire to skip school.

Another German study of the FFF movement concluded that youth climate activists are “depicted according the ‘pupil-being.’ In this cultural construct, youth are, to use Nancy Lesko’s schema, immature students who are “coming of age,” rather than responsible and informed adults “protesting against the failure of the established environmental governance regime to address climate change” (Bergmann and Ossewaarde, 2020, p. 272). These cultural representations encode children and youth as “mere ‘becomings’ and ‘beings’” (Todres et al., 2023, p. 417). This concept of youth as coming of age is also reflected in two German studies which found a narrative of youth as subject to peer pressure. Media depictions described Fridays for the Futures participants as blindly following “the personality cult of Greta Thunberg,” with publications dismissing youth climate activists as school children obsessed with the latest pop idol (Bergmann and Ossewaarde, 2020, p. 273, von Zabern and Tulloch, 2021, p. 13). Instead of describing young climate activists as intelligent and responsible, “courageous in their concerns” and politically astute and effective in their “abilities to organize, mobilize, and inspire action,” (Cowan et al., 2023, p. 78) mainstream media narratives, from Australia, to Germany, to the United States, lock youth activists into a limited typology which has been categorized as “dutiful, disruptive, and dangerous” (Cowan et al., 2023; O’Brien et al., 2018).

A key dynamic of dominant framings of youth climate activists is the way they delegitimize protests by citing age (Marquardt, et al, 2024). Hannah Feldman’s analysis of the School Strike for Climate movement finds that the media’s emphasis on “protestors’ age and lack of perspective or education” works to silence legitimate critiques of government environmental policy “via a commonly accepted deficit attitude toward young people’s engagement with polity” (p. 5). In 2020, German police even advised that students under 18 participating in climate strike walkouts should be reported to authorities and a recent U.N. report found that young people are the victims of a disproportionate number of attacks on climate activists, including fatal ones (Daly, 2020; Bahuet and Altorp, 2022). While attitudes toward youth vary, and in particular swing between concepts of youth as “pawn and threat, dangerous and defenseless” (Fournier, 2015, p. 38), studies by Feldman (2020) demonstrate the extent to which mainstream media and institutional representations of youth rely on fixed, largely negative characteristics linked to age. Rather than seeing youth as ‘citizens with agency,” such cultural depictions frame youth as “in a state of “becoming” future citizens,” who are “training to be participants in the sphere of formal politics,” (O’Brien et al., 2018, p. 42) and not yet suited for responsible adult decision-making.

Thus, studies of discourse surrounding young climate activists underscore how youth political representation and power is impacted by cultural representation (Daly, 2022). These cultural framings directly or indirectly serve the status quo, and limit youth voices and the adoption of policies to address global climate change. Dominant cultural representations of youth as irresponsible, disruptive, truants, motivated by peers or by other non-political aims, affect policy, in that the “political agenda of the protesters is completely marginalized” and “their demands and accusations are either missing or presented as vague and apolitical” (von Zabern and Tulloch, 2021, p. 12). More, unlike direct disenfranchisement of youth through voting laws, these cultural constructions are largely invisible and unquestioned. To the extent they are made evident, negative characteristics of youth are seen as a “natural” outgrowth of their age.

Neoliberal capitalism more generally relies on ideological framings of dissent and dissenters as illegitimate (Chiapello, 2005; Jacobsson, 2020; Bečević and Dahlstedt, 2022). In the case of youth climate activists, illegitimacy is conferred in part by cultural representations based in, as Nancy Lesko says, “massified” concepts of young people. These dominant cultural representations skew heavily toward negative depictions of youth. As Henry Giroux’s analysis of Hollywood films of the 1990s and 2000s concludes, youth, viewed as “slackers, gangsters, or sell-outs,” are largely defined by mainstream American popular culture “through the lens of contempt or criminality” (p. 73). These negative stereotypes of youth also factor in political systems related to youth voting, and contribute to the severe underrepresentation of youth in legislative bodies. Cultural constructs of youth, and the larger bifurcation of child/adult, result in generalizations about adolescence as antithetical to adult maturity. The last section considers this, in a discussion of implications of debates related to the voting age to cultural and political youth representation.

Discussion and implications for youth representation

As Stuart Hall reminds us, “we give things meaning by how we represent them—the words we use about them, the stories we tell about them, the images of them we produce, the emotions we associate with them, the ways we classify and conceptualize them, the values we place on them (Hall et al., 2013, p. xix). What do we learn by adding Stuart Hall’s theories of cultural representation to Hanna Pitkin’s on political representation? What happens when we consider the presence of beliefs about youth in Pitkin’s “rather complicated, convoluted, three-dimensional structure in the middle of a dark enclosure?” How can shifting analyses of political science and cultural studies from parallel to intersecting lines of inquiry lead to greater understanding of the problem of youth representation? What policies might follow from considering implications of cultural constructs which reduce diverse groups of young people to a singular “youth,” represented as immature, “coming of age,” and not yet ready for the responsibilities of democratic decision making?

Conceptual “massification,” and consequent stereotyping of young people is, to be sure, not only a problem of depictions of youth (Spencer, 2021). For example, the importance of gender as well as age in the silencing and discrediting of climate change activists has been documented. A recent empirical study concluded that “gender is deeply imbricated in any discussion of climate change’ (Kaul and Buchanan, 2023, p. 310). Similarly, research on voters in the US 2024 presidential election published in an article tellingly entitled “She Came, She Saw, He Conquered” concludes that “gender-based appeals were central to the success of Trump’s 2024 campaign,” and that “sexist attitudes—whether benevolent, hostile, or both—were consistently associated with candidate preference in every presidential election from 2008 onward.” (Blankenship and Moadel-Attie, 2024). Continued stereotypes about gender mean that despite the lowering of structural barriers to American women’s political participation (though not, notably, the inclusion of gender parity quotas), a woman has yet to be elected US president, and women continue to lag behind men in Congress. Yet women’s underrepresentation pales compares to youth. There are 125 female members in the US 119th Congress, or just under 30%. But only 12, or 2.7%, of US House Representatives are under 35 (Hatfield, 2025; Sanbonmatsu, 2020).

One policy route to address that is to reconsider minimum voting age requirements. Today, those limits are usually set at 18, with about 25 countries, and some US states and municipalities offering limited access to the franchise for 17 and 16 year olds (Jenkins, 2024; Mańko, 2023). Yet as with conceptions of youth as rebellious, or more prone to violence, youth voting policies have changed and evolved, with the adoption of an 18 year old vote, now the norm in 90% of cases, coinciding with a worldwide youth protest movement (UNICEF, n.d.) in the late 1960s and 1970s. In 1969, two years before the United States adopted the 26th Amendment, giving 18 year olds the right to vote, the US Supreme Court, in Des Moines (1969), ruled in favor of 13-year-old Mary Beth Tinker and other students who had been suspended from school for wearing black armbands in protest of the Vietnam War. The majority defended student political speech, memorably declaring that youth do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” However, the dissent by Justice Hugo Black was also notable.

And I repeat that, if the time has come when pupils of state-supported schools, kindergartens, grammar schools, or high schools, can defy and flout orders of school officials to keep their minds on their own schoolwork, it is the beginning of a new revolutionary era of permissiveness in this country fostered by the judiciary. The next logical step, it appears to me, would be to hold unconstitutional laws that bar pupils under 21 or 18 from voting, or from being elected members of the boards of education (p. 518).

While Justice Black was not a good predictor of the future, his dissent is good as capturing cultural representations of youth. They are pupils who should “keep their minds on their own schoolwork,” and are associated with revolutionary and permissive values. A lowered voting age is presented as a danger to the social order. Though the US did subsequently lower the voting age from 21 to 18, negative attitudes toward youth and fears about youth voting persist, and inform justifications for the current standard of a minimum 18 year old voting age (Circle at Tufts, 2023; Hinze, 2024; Bessant, 2020; Todres et al., 2023; Wall, 2022). Debates over the voting age thus raise larger questions about the relationship between cultural representation of youth and political representation.

In particular, the preceding analysis of youth cultural representation leads to a central observation about the problem of youth political representation-it’s not about youth, but adult perceptions of them. Thus the 18 year old voting age relies on a deficit model for cultural framings of youth and their tendencies and “innate” capacities (Sandin, et al., 2023). These negative representations of youth work against their inclusion and participation in democratic decision making. As Jakob Hinze’s analysis of young people and elections concludes, the “voting age excludes young people from developing a sense of political efficacy through voting. To the contrary, it sends an unmistakable signal to them that their judgment does not matter” (p. 86). As longitudinal studies of voting behavior have found, voting is a habit, important to developing lifelong civic engagement (Wagner et al., 2012; Franklin et al., 2004). And while data is limited on impacts of a lower voting minimum age, studies that have been done on 16 year old voting in Latin America and Austria find positive benefits for how youth view democracy and their sense of political efficacy (Hinze, 2024; Eichhorn and Bergh, 2020; Michelsen, 2020). While such studies and others demonstrate the validity of arguments for lowering the voting age to 16 or even more (Todres and Kilkelly, 2022; Bessant, 2020; Hinze, 2024), my point here is broader. Cultural representations of youth as immature, irresponsible, apathetic, and not yet ready for full citizenship also impact the ability of youth to have their voices heard in policy debates.

This is evident in the previous section’s discussion of media accounts of young climate activists. They present a deficit model in which youth are seen as immature, and acting on emotion (Bessant, 2020; Tapia-Echanove et al., 2025). Youth climate activists challenge this, pointing the need to act with urgency to address ongoing and worsening climate disasters. As then 15-year-old Greta Thunberg bluntly told the European Parliament in 2019, “You are not mature enough to tell it like it is. Even that burden you leave to us children.” (Thunberg, 2019). This challenge to depictions of young people as less mature also arose in a 2018 contest in Massachusetts’s 7th Congressional district. Incumbent Representative Michael Capuano (age 66) ran a campaign based on his maturity, and success in being a “pragmatic idealist,” focused on smaller, slower, policy steps in both actions to address climate change, and racial injustice. But his then 44-year-old opponent, Boston City Councilor Ayanna Pressley, won the race with a slogan “Change cannot wait.” (Vázquez Toness, 2009; Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, 2019) Pressley, in 2019, introduced a Congressional amendment which would lower the federal voting age to 16. In her remarks, the Massachusetts representative said, citing the presence of youth “at the forefront of social and legislative movements,” that “some have questioned the maturity of our youth. I do not.” Rejecting dominant cultural representations of youth, Pressley framed the question of a lower voting age as “ensuring that those who have a stake in our democracy will also have a say in our democracy.” Pressley, along with other advocates of a lowered voting age, define the issue as one of unfair exclusion of youth, a group representing 20% of the US population, arguing that the rationale for excluding youth on the basis of age relies on stereotype and generalization, and denies young people a voice in major policy debates and decisions (Todres, 2022; Youth Population Profile detailed by age, sex, and Race/Ethnicity, n.d.).

At the conclusion of his study of voting age debates, Jakob Hinze asks, “what purpose does the voting age serve, after all?” (p. 86) One clear result, if not purpose, of a relatively high minimum voting age is that it limits the involvement of youth in decision making processes and affects public policy. Henry Giroux puts the consequence of this exclusion in stark terms: “American society at present exudes both a deep rooted hostility and chilling indifference toward youth, reinforcing the dismal conditions that young people are increasingly living under” (p. 72). Just as Greta Thunberg turned the tables on stereotypical representations of youth, naming adults as the immature ones for their refusal to act on climate change, researchers who question the minimum voting age point to the ways in which adult biases and negative cultural representations of youth lurk behind arguments for keeping the status quo. As Jonathan Todres, Charlene Choi and Joseph Wright, respectively professors of law, medicine, and education, note, voting age limits are part of a larger exclusion of youth in which “their rights to express themselves, protest, and demonstrate are subject to greater state restrictions than adults face” (2023, p. 455). This arguably makes minimum voting age limits a civil rights issue, in that such limits are rooted in stereotyped and generalized representations of children and youth.

What does all this mean in terms of addressing the problem of youth representation? Certainly a range of issues, including inadequate civic engagement education, barriers in voting systems, and limited candidate options, impact youth voter turnout and representation (Stockemer and Sundström, 2022; Todres and Kilkelly, 2022; Wagner et al., 2012). But as Jonathan Todres concludes, “scaling up youth participation. …will require that we confront challenges on the part of adults that have led to systematic exclusion of young people from decision making processes” (2023, p. 449). The stories adults tell about youth, via cultural discourse, images, and texts bear on the problem of youth representation. Greater understanding the impact of cultural representation on youth political representation will not solve the problem of youth underrerpresentation. But including cultural studies approaches to the “flash-bulb photographs of the structure” (Pitkin, p. 10) of youth representation surely increases our ability to understand it.

Author contributions

MB: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alvermann, D. (2009). “Sociocultural constructions of adolescence and young people’s literacies,” in Handbook of adolescent literacy research. eds. L Christenbury, R Bomer, and P Smagorinsky. (New York: Guilford) 31–56.

Antkowiak, L. S. (2024). Who substitutes Service for Politics? Assessing the roles of youth and partisan alienation in Americans’ forms of civic engagement. Polit. Res. Q. 77, 89–105. doi: 10.1177/10659129231194641

Arnett, J. J. (2006). G. Stanley Hall’s adolescence: brilliant and nonsense. Hist. Psychol. 9, 186–197. doi: 10.1037/1093-4510.9.3.186

Austin, J., and Willard, M. N. (1998). Generations of youth: Youth cultures and history in twentieth-century America. New York: New York University Press.

Bahuet, C., and Altorp, A. (2022). Urgent need to protect young climate activists. UNDP Climate Promise blog, June 13. Available at: https://climatepromise.undp.org/news-and-stories/urgent-need-protect-young-climate-activists (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Baldwin, J. (1957). “Sonny’s blues” in The Oxford Book of American Short Stories. ed. J. C. Oates (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Banaji, S., and Cammaerts, B. (2014). Citizens of nowhere land: youth and news consumption in Europe. Journal. Stud. 16, 115–132. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2014.890340

Bastedo, H. (2012). They Don’t stand for me: Generational difference in voter motivation and the importance of symbolic representation in youth voter turnout. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

Bečević, Z., and Dahlstedt, M. (2022). On the margins of citizenship: youth participation and youth exclusion in times of neoliberal urbanism. J. Youth Stud. 25, 362–379. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2021.1886261

Bergmann, Z., and Ossewaarde, R. (2020). Youth climate activists meet environmental governance: ageist depictions of the FFF movement and Greta Thunberg in German newspaper coverage. J. Multicult. Discourses 15, 267–290. doi: 10.1080/17447143.2020.1745211

Bessant, J. (2020). From denizen to citizen: Contesting representations of young people and the voting age. J. Appl. Youth Stud. 3, 223–240. doi: 10.1007/s43151-020-00014-4

Blankenship, B., and Moadel-Attie, R. (2024). She came, she saw, he conquered: gender, polarization, and the 2024 U.S. presidential election: SPSSI virtual issues. Available online at: https://spssi.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/toc/10.1111/(ISSN)9999-0025.2024-US-Presidential-Election (Accessed January 16, 2025).

Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE). (2025). Tufts University. Available online at: https://circle.tufts.edu/ (Accessed November 1, 2024).

Chiapello, E. (2005). The new Spirit of capitalism. Int. J. Politics Cult. Soc. 18, 161–188. doi: 10.1007/s10767-006-9006-9

Christenbury, L., Bomer, R., and Smagorinsky, P. (2009) Handbook of adolescent literacy research. New York: Guilford, 14–28.

Circle at Tufts. (2023). Concern for climate change directly informs youth civic engagement. Available online at: https://circle.tufts.edu/latest-research/concern-climate-change-directly-informs-youth-civic-engagement (Accessed November 1, 2024).

Cohen, R. D. (1997). The delinquents: censorship and youth culture in recent U.S. history. Hist. Educ. Q. 37, 251–270. doi: 10.2307/369445

Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley. (2019). Rep. Pressley’s floor remarks on lowering the voting age. [Press Release]. Available online at: https://pressley.house.gov/2019/03/07/rep-pressleys-floor-remarks-lowering-voting-age/ (Accessed July 14, 2025).

Cowan, J. M., Dzidic, P., and Newnham, E. (2023). The Australian mainstream media’s portrayal of youth climate activism and dissent. Qual. Sociol. Rev. 19, 74–91. doi: 10.18778/1733-8077.19.2.04

Daly, A. (2020). It is time to accept that children have a right to be political. Bristol, U.K: Discover Society. Social Research Publications.

Daly, A. (2022). Climate competence: youth climate activism and its impact on international human rights law. Hum. Rights Law Rev. 22, 1–24. doi: 10.1093/hrlr/ngac011

Delgado, M. (2002). New frontiers for youth development in the twenty-first century revitalizing and broadening youth development. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dovi, S. (2018). “Political representation” in The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. ed. E. N. Zalta. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

Eichhorn, J., and Bergh, J. (2020). Lowering the voting age to 16. Learning from Real Experiences Worldwide. US: Palgrave Macmillan.

Equal Justice Initiative (2017). “All children are children: Challenging abusive punishment of juveniles.” Montgomery, AL: EJI.

Feldman, H. R. (2020). A rhetorical perspective on youth environmental activism. J. Sci. Commun. 19:C07. doi: 10.22323/2.19060307

Fournier, A. (2015). Immature publics: democratic revolutions and youth activists in the eye of authority. Anthropol. Q. 88, 37–65. doi: 10.1353/anq.2015.0000

Franklin, M., Marsh, M., and Lyons, P. (2004). The generational basis of turnout decline in established democracies. Acta Politica. 39, 115–151. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500060

Giroux, H. A. (Editor). (2022). “Disposable youth/disposable futures: the crisis of politics and the public life” in American youth cultures (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 71–87.

Golub, A. (2015). A transnational tale of teenage terror: the blackboard jungle in global perspective. J. Transnational American Stud. 6, 1–10. doi: 10.5070/T861025868

Gordon, H. R. (2009). We fight to win: Inequality and the politics of youth activism. Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Griffin, C. (1993). Representations of youth: The study of youth and adolescence in Britain and America. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Hartung, C. (2017). Conditional citizens rethinking children and young people’s participation. 1st Edn. Singapore: Springer.

Hastings, E. B. (2022). The senate comic book hearings of 1954: In Custodia legis. Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress.

Hatfield, J. (2025). The changing face of congress in 7 charts. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center.

Hinze, J. (2024). “Young people, elections, and the epistemic value of democracy” in Handbook of children and youth studies. eds. J. Wyn, H. Cahill, and H. Cuervo (Singapore: Springer).

Jacobsson, D. (2020). Young vs old? Truancy or new radical politics? Journalistic discourses about social protests in relation to the climate crisis. Crit. Discourse Stud. 18, 481–497. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2020.1752758

Jamieson, P. E., and Romer, D. (2008). The changing portrayal of adolescents in the media since 1950. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, A. (2024). Voting age status report - nyra. Hyattsville, MD: National Youth Rights Association.

Kaul, N., and Buchanan, T. (2023). Misogyny, authoritarianism, and climate change. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 23, 308–333. doi: 10.1111/asap.12347

King, M.L. (1958). Address at youth march for integrated schools in Washington, D.C., delivered by Coretta Scott King. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. Available online at: https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/address-youth-march-integrated-schools-washington-dc-delivered-coretta-scott#fn2 (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Kitanova, M. (2019). Youth political participation in the EU: evidence from a cross-national analysis. J. Youth Stud. 23, 819–836. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2019.1636951

Lesko, N. (2012). Act your age!: A cultural construction of adolescence. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Marquardt, J., Lövbrand, E., and Buhre, F. (2024). The politics of youth representation at climate change conferences: who speaks, who is spoken of, and who listens? Global Environ. Politics 24, 19–45. doi: 10.1162/glep_a_00736

Michelsen, N. G. (2020). Votes at 16: Youth enfranchisement and the renewal of American democracy. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

O’Brien, K., Selboe, E., and Hayward, B. M. (2018). Exploring youth activism on climate change: dutiful, disruptive, and dangerous dissent. Ecol. Soc. 23:42. doi: 10.5751/ES-10287-230342

Petrone, R., Sarigianides, S. T., and Lewis, M. A. (2014). The youth Lens: analyzing adolescence/ts in literary texts. J. Lit. Res. 46, 506–533. doi: 10.1177/1086296X15568926

Rehfeld, A. (2011). The concepts of representation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 105, 631–641. doi: 10.1017/S0003055411000190

Representation definition (n.d.). Cambridge English dictionary. Representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rohrschneider, R., and Thomassen, J. J. A. (Eds.) (2020). The Oxford handbook of political representation in liberal democracies. Cambridge, UK: Oxford University Press.

Rowe, J. (1992). “Holden Caulfield and American protest” in New essays on the catcher in the Rye. ed. J. Salzman. 1st ed (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press).

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2020). Women’s underrepresentation in the U.S. congress. Dædalus, J. American Acad. Arts Sci. 149, 40–55. doi: 10.1162/daed_a_01772

Sandin, B., Hanson, K., and Balagopalan, S. (2023). The politics of children’s rights and representation. 1st Edn. US: Springer International.

Sasani, S., and Javidnejat, P. (2015). A discourse of the alienated youth in American culture: Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger’s the catcher in the Rye. Asian. Sociol. Sci. 11, 204–210.

Short, D. (2012). “Juvenile justice, history of” in The social history of crime and punishment in the U.S.: An encyclopedia. ed. W. F. Miller (Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Sage).

Sit-ins in Greensboro. SNCC digital gateway. (2021). Available online at: https://snccdigital.org/events/sit-ins-greensboro/ (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Smith, L. (1960). Sit-ins, the students report. Available online at: https://www.crmvet.org/docs/60_core_sitin.pdf (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Spencer, B. (2021). Impact of racism and sexism in the 2008–2020 US presidential elections. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 21, 175–188. doi: 10.1111/asap.12266

Stockemer, D., and Sundström, A. (2022). Youth without representation: The absence of young adults in parliaments, cabinets, and candidacies. 1st Edn. Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA: University of Michigan Press.

Stockemer, D., Thompson, H., and Sundström, A. (2023). Young adults' under-representation in elections to the U.S. house of representatives. Elect. Stud. 81:102554. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102554

Tapia-Echanove, M., Bloch-Atefi, A., Hanson-Easey, S., Oswald, T. K., and Eliott, J. (2025). Climate change cognition, affect, and behavior in youth: A scoping review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 16:e70000. doi: 10.1002/wcc.70000

Thunberg, G. (2019). Speech at the European parliament. Archives of Women’s Political Communication. Available online at: https://awpc.cattcenter.iastate.edu/2019/12/02/speech-at-the-european-parliament-april-16-2019/ (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Todres, J. (2022). Age discrimination and the personhood of children and youth. Harvard Human Rights Journal. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4295094

Todres, J., Choi, C., and Wright, J. (2023). A rights-based assessment of youth participation in the United States. Temple Law Rev. 95, 411–455.

Todres, J., and Kilkelly, U. (2022). Advancing children’s rights through the arts. Hum. Rights Q. 44, 38–55. doi: 10.1353/hrq.2022.0001

Torres, M., and Río, N. (2013). Citizens in the present: Youth civic engagement in the Americas. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

UNICEF. (n.d.). Should children vote?. Innocenti Global Office of Research and Foresight. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/should-children-vote (Accessed July 16, 2025).

United States Congress Senate Committee on the Judiciary (1954). Hearings before the subcommittee to investigate juvenile delinquency. Washington: U. S. Govt. Print. Office.

United States Surgeon General. (2023). Social media and youth mental health. Available online at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/sg-youth-mental-health-social-media-advisory.pdf (Accessed July 16, 2025).

von Zabern, L., and Tulloch, C. D. (2021). Rebel with a cause: the framing of climate change and intergenerational justice in the German press treatment of the Fridays for future protests. Media Cult. Soc. 43, 23–47. doi: 10.1177/0163443720960923

Wagner, M., Johann, D., and Kritzinger, S. (2012). Voting at 16: turnout and the quality of vote choice. Elect. Stud. 31, 372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2012.01.007

Wall, J. (2022). “The case for children’s voting,” in Studies in Childhood and Youth. Rutgers, New Jersey, USA: Palgrave Macmillan. 67–88. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-14541-4_4

Youth Population Profile detailed by age, sex, and Race/Ethnicity. (n.d.). Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Available online at: https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/statistical-briefing-book/population/faqs/qa01104 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

Keywords: youth, cultural representation, political participation, media, representation

Citation: Battenfeld M (2025) The impact of cultural representation of youth on political representation. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1591929. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1591929

Edited by:

Enrique Hernández-Diez, University of Extremadura, SpainReviewed by:

Bettina Steible, Open University of Catalonia, SpainGomer Betancor Nuez, National University of Distance Education (UNED), Spain

Copyright © 2025 Battenfeld. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mary Battenfeld, bWJhdHRlbkBidS5lZHU=

Mary Battenfeld

Mary Battenfeld