- Department of Political Science, Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden

While Western democracies have become increasingly gender-equal over the past decades, recent research documents a backlash against gender equality in the form of rising modern sexism. Previous research shows that modern sexism predicts political attitudes and voting behavior that are detrimental to women's empowerment and liberalism. Yet, we know little about which factors explain modern sexist attitudes and how they operate across multiple country contexts. Building on modern conceptualizations of sexism, we theorize that (perceived) increases in competition between men and women provoke modern sexism among young men in particular. Using an original measure that approximates dimensions of modern sexism embedded in the 2021 EQI survey, capturing 32,469 individuals nested in 208 NUTS 2 regions in 27 European Union countries, we demonstrate that young men are most likely to perceive advances in women's rights as a threat to men's opportunities. This is particularly true for young men who (a) consider public institutions in their region as unfair, and (b) reside in regions with recent increases in unemployment resulting in increased competition for jobs. Our findings highlight the role of perceived competition between men and women in modern sexism and contradict the argument that older generations are most likely to backlash against progressive values, potentially adding to research explaining the recent backlash against gender equality.

Introduction

While much research documents increasing gender equality and sexual freedom in Western democracies and globally since the second half of the twentieth century (Inglehart and Norris, 2003; Goldin, 2014; Alexander et al., 2016), recent research describes the emergence of a movement counteracting these developments (Kuhar and Paternotte, 2018). Radical right political actors, religious organizations, and civil society promote modern sexist positions and organize against feminism and sexual freedom, aiming to preserve the patriarchal and heteronormative social order (Kuhar and Paternotte, 2018). Arguably, there is a backlash against feminism and sexual freedom that is politically manifested, for instance, in politicians' overt sexism and laws restricting women's and LGBTQI+ rights in countries like the United States, Poland, Hungary, and others (Grzebalska and Peto, 2018; Darakchi, 2019; Faludi et al., 2019; Maxwell and Shields, 2019; Cabezas, 2022). Yet, we know little about the factors explaining modern sexist attitudes at the individual level and across different country contexts.

According to Manne (2017, 79), sexism serves to justify and rationalize patriarchal social relations characterized by the structural dominance of men over women. The psychological literature explains sexist attitudes mostly by ideology (e.g., Christopher and Wojda, 2008; Mosso et al., 2012; Hellmer et al., 2018; Van Assche et al., 2019), and personality traits (e.g., Akrami et al., 2011; Hellmer et al., 2018). While this research is insightful, we still know little about the demographic factors and contextual factors explaining sexist attitudes.

Regarding demographic factors, cultural backlash theory holds that older generations hold more conservative values and younger generations are more progressive (Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Yet, there is research also demonstrating that different generations hold similar cultural attitudes (Schäfer, 2021). Similarly, while some scholars argue and find that men are more sexist than women (Glick et al., 2004; Russell and Trigg, 2004; Christopher and Mull, 2006; Roets et al., 2012), others find that gender explains only very little of the variation in sexism (Glick et al., 2004; Russell and Trigg, 2004; Roets et al., 2012; Van Assche et al., 2019). Regarding contextual factors, modernization theorists argue that economic and institutional development leads to more emancipative values, including gender equality and sexual freedom (Inglehart and Baker, 2000; Welzel, 2013). However, the recent backlash against feminism is observed in Western democracies with relatively developed economies and political institutions, such as the United States (Ratliff et al., 2019) and the United Kingdom (Green and Shorrocks, 2021). More research is thus needed on demographic and contextual factors explaining sexism.

Building on the concepts of hostile sexism (Glick and Fiske, 1996), envious prejudice (Fiske et al., 1999), and modern sexism (Swim et al., 1995), we theorize that perceived competition between men and women explains sexism among individuals who may expect to lose from this competition. According to our argument, these individuals are disproportionately young men, as they are most likely to perceive women's competition as a potential threat to their future life courses. Further in line with our argument, young men who perceive institutions in their regions to be unfair react more strongly to this perceived competition and express more sexism, as they are more likely to consider this competition to be unfair1. Finally, young men residing in regions that record recent increases in unemployment will express more sexism due to the increased competition in the labor market, which they may perceive to be further aggravated by increasing women's labor force participation.

We test these hypotheses using large-n survey data (n = 32,469) from 27 European Union countries at the regional NUTS 2 level (208 regions), analyzing agreement with an original measure that captures sexism in response to perceived competition between men and women. While support for advancing women's rights is relatively high across the sample, we find that young men, in particular, express the greatest opposition, especially if they distrust public institutions in their region of residence or if they reside in regions with recently rising unemployment, which supports our theoretical argument and contrasts expectations from cultural backlash theory.

This study contributes to the existing literature on sexism, first, by analyzing representative cross-national regional-level survey data, which allows us to test individual-level demographic and regional-level contextual factors predicting sexism across 27 European Union countries. Theoretically, we contribute to the literature on sexism by theorizing and testing the role of perceived competition between men and women in young men's sexism. The focus on perceived competition between men and women may be particularly apt for explaining rising sexism in countries marked by relatively advanced gender equality, where women may more realistically come to represent a competitive threat to men. Our study thus contributes to explaining rising sexism in a population group that is often expected to be relatively progressive: young men in economically developed democracies.

This paper proceeds by defining modern understandings of sexism and presenting previous literature on predictors of sexist attitudes. Second, we theorize perceived competition between men and women as a driver of sexism, especially in relatively gender-equal contexts and among young men. Third, we present the methods and data used in this study, followed by the results of our analysis. We conclude by situating our results within the findings of previous research.

Defining sexism

According to Manne (2017, 79), “sexism should be understood primarily as the ‘justificatory’ branch of a patriarchal order, which consists in ideology that has the overall function of rationalizing and justifying patriarchal social relations”, where the patriarchal order is characterized by women being “positioned as subordinate in relation to some man or men […], the latter of whom are thereby […] dominant over the former, on the basis of their genders (among other relevant intersecting factors)” (45). Sexist attitudes are thus defined as attitudes that justify a system of men's dominance over women, for instance by emphasizing natural differences between men as the stronger and women as the weaker sex. However, with increasing gender equality in various societies over the past decades, sexism has often become more subtle than the above definition suggests.

Reacting to the need to assess subtle sexism in a context of increasing gender equality, Swim et al. (1995) developed the Modern Sexism Scale. Accordingly, examples of modern sexism are the denial of women's continued discrimination and the rejection of demands for increased gender equality. It is based on the perception that gender equality is already established and further anti-discrimination laws or measures to promote women would result in special favors toward women.

Similarly, Glick and Fiske (1996) developed the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory that distinguishes between hostile and benevolent sexism to explain how even seemingly positive stereotypes about women reinforce patriarchal order. They describe sexism as an ambivalent case of prejudice because it is not only hostile and involves intimate relationships and emotional dependency between the dominant and subordinated population groups. Thus, while hostile sexism justifies women's discrimination, for instance by ascribing less competence to women than to men, benevolent sexism reinforces traditional gender roles through positive stereotyping, for instance by considering women as the better parent. Such positive stereotyping does not involve hostility toward women but still serves to uphold traditional gender roles, wherein women are considered the “weaker” sex and deserve protection, and men are the providers and protectors. Further, Glick and Fiske (1996) argue that hostile and benevolent sexism are positively correlated, despite their contradictions, making sexism an ambivalent concept. For the study at hand, hostile sexism and its focus on competitive gender differences and the zero-sum nature of gender equality are of particular relevance, as we further elaborate in the theory section. Both the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory and the Modern Sexism Scale constitute bases for our theorization of perceived competition between men and women as a driver of sexism among young men in relatively gender-equal contexts.

Predicting sexism by psychological, ideological, demographic, and contextual factors

Previous research has mostly explained sexism psychologically by various personality traits and ideologies. These include dimensions of the Big Five personality traits, especially openness and agreeableness (Akrami et al., 2011; Grubbs et al., 2014), as well as empathy and the ability to take others' perspectives (Hellmer et al., 2018), which are all considered to be negatively related to sexism. On the other hand, the personality trait of psychological entitlement, i.e., the notion of oneself deserving special treatment, is shown to be positively related to sexism (Grubbs et al., 2014; Hammond et al., 2014).

The most prominent ideological explanatory factors used to predict sexism are social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism (Sibley et al., 2007; Christopher and Wojda, 2008; Akrami et al., 2011; Hart et al., 2012; Mosso et al., 2012; Rosenthal et al., 2014; Van Assche et al., 2019). Herein, high levels of social dominance orientation refer to an understanding of intergroup relations as hierarchical, marked by the superiority of one group over another. Right-wing authoritarianism then implies the favoring of strong authorities, social cohesion, and collective security (Sibley et al., 2007). While both of these ideological factors are shown to be positively related to sexism, studies reveal that social dominance orientation is particularly related to hostile sexism, and right-wing authoritarianism is particularly predictive of benevolent sexism (Christopher and Mull, 2006; Sibley et al., 2007; Christopher and Wojda, 2008). Related to authoritarianism and the emphasis on traditional values, political conservatism has also been shown to predict sexism (Christopher and Wojda, 2008; Mosso et al., 2012). In contrast, studies reveal mixed findings on the relationship between religiosity and sexism: Religiosity is shown to predict benevolent sexism in Spain, Belgium, and Turkey (Glick et al., 2002; Van Assche et al., 2019), but not in the Netherlands, Italy and the US (Mosso et al., 2012; Van Assche et al., 2019).

Regarding demographic factors, few existing studies explicitly focus on the effects of gender and age on sexism. Unsurprisingly, previous research agrees that men tend to be more sexist than women (Mosso et al., 2012; Hellmer et al., 2018; Cowie et al., 2019), where the difference is more pronounced for hostile than benevolent sexism (Glick et al., 2004), which can be explained by sexism being a system that discriminates against women. Herein, women who feel psychologically entitled, i.e., deserving of special treatment, are particularly likely to hold benevolent sexist attitudes (Hammond et al., 2014), since benevolent sexism emphasizes stereotypical positively-connoted traits of women. Yet, various studies also highlight that gender explains only little of the variation in sexism, and women and men hold relatively similar sexist attitudes, despite some existing differences (Glick et al., 2004; Roets et al., 2012).

The relationship between age and sexism is less clear. Glick et al. (2002) show that higher age is associated with higher levels of benevolent sexism among men and women in Spain, but not with hostile sexism. While Hammond et al. (2018) find a similarly linear effect of age on men's benevolent sexism in New Zealand, their study reveals that women's benevolent sexism, as well as men's and women's hostile sexism, have a U-shaped relationship with age. Accordingly, younger and older individuals are more sexist than middle-aged individuals. Investigating attitudes toward feminism, Fitzpatrick Bettencourt et al. (2011) find that age is related to negative attitudes toward feminism for women but not for men. Accordingly, young women hold more progressive attitudes toward feminism than young men, whereas older men and women do not differ in their attitudes toward feminism. These findings, however, contradict Huddy et al. (2000) study showing that both young women and men hold more positive attitudes toward the women's movement than older individuals of the same gender. Theorizing and studying generational differences in cultural attitudes more generally, Norris and Inglehart (2019) argue that older generations tend to hold more conservative attitudes and younger generations tend to hold more progressive attitudes. However, Schäfer (2021) demonstrates that these differences are explained by data specification rather than actual variation in the data and demonstrates that generations differ only a little from each other in their cultural attitudes. There is thus mixed evidence on the relationship between age, as well as the interaction between gender and age, and sexism.

Further, previous research considers the demographic factor of education. Glick et al. (2002), Hellmer et al. (2018) and Mosso et al. (2012) find that the level of education is negatively related to both benevolent and hostile sexism in men and women in Spain, Sweden, and the US. Van Assche et al. (2019) find that education predicts hostile sexism but not benevolent sexism in the Netherlands. However, other studies controlling for the effect of education find no significant effects in Italy (Mosso et al., 2012) and Turkey (Van Assche et al., 2019).

Most of the existing studies on sexism are difficult to compare, which complicates any inference about the influence of demographic or contextual variables on sexism. This lack of comparability stems from at least two factors: First, many studies use unrepresentative convenience samples, often consisting of undergraduate students (e.g., Russell and Trigg, 2004; Hellmer et al., 2018), which limits variation in age and place of residence. Second, most previous research consists of single-country studies, and many studies are conducted in the US context (e.g., Christopher and Wojda, 2008; Rosenthal et al., 2014), which hinders cross-national and cross-cultural comparisons. Some exceptions are a cross-national study by Glick et al. (2004) including population samples from 19 countries worldwide, as well as Mosso et al. (2012)'s comparison of the US and Italian contexts, and Van Assche et al. (2019)'s study on Belgium, the Netherlands, and Turkey. However, neither of these studies test for contextual effects. While Mosso et al. (2012) and Van Assche et al. (2019) discuss their results in light of cultural differences between their studied countries' gender norms and religion, Glick et al. (2004) do not elaborate on contextual factors that could potentially explain country differences. To our knowledge, subnational contextual factors, such as regional economic performance or urbanization, are not considered in the psychological literature on sexism.

However, the literature on emancipative values provides evidence of the effects of contextual factors that is relevant to the role of context in understanding sexist attitudes. Emancipative values include gender equality and sexual freedom (Welzel, 2013) and thus stand in contrast to sexism. According to modernization theory, emancipative values emerge in contexts characterized by economic development and democratic institutions, as existential security promotes the valuing of individual self-expression, education encourages critical thinking and political participation stimulates the questioning of authorities (e.g., Inglehart and Baker, 2000). Accordingly, in contexts marked by economic development and democratic institutions where individuals experience existential security, in-groups will be more tolerant and less hostile toward outgroups (Welzel, 2013). While the theory refers to various kinds of ingroup-outgroup relations, it also applies to relations between men and women and resulting advances in gender equality (Alexander and Welzel, 2011). Based on the literature on emancipative values, sexist attitudes are therefore expected to be less pronounced in economically developed contexts and in contexts with well-functioning democratic institutions. Yet, as the emancipative values literature usually considers an index of various values, more research is needed on contextual factors explaining sexism in particular.

While economic development is shown to lead to emancipative values, economic crises can in turn set back previous achievements in gender equality, institutionally and in terms of individual behavior: Feminist economists show that neoliberal austerity measures result in the cutting of women-dominated public sector employment and public services, including care services (Rubery, 2015). Beyond these institutional setbacks, gender-based violence has been shown to increase during economic crises (Kantola and Lombardo, 2017, p.5). The contextual effect of the economy may thus affect sexism both ways: While sexism may decline as economies develop, economic downturns can lead to increased sexism.

Theorizing perceived competition as a driver of sexism

We address the gap in the literature on demographic and contextual factors influencing sexism by theorizing that perceived competition between men and women acts as a driver of sexism. We hypothesize that this is the case, particularly among young men who (a) perceive public institutions in their region to be unfair, and (b) reside in regions that register recent increases in unemployment. This theorization is based on group and status threat theory, as well as the concepts of hostile sexism (Glick and Fiske, 1996), envious prejudice (Fiske et al., 1999), and modern sexism (Swim et al., 1995), as well as more recent studies focussing on the notion of competition between men and women (Kasumovic and Kuznekoff, 2015; Mansell et al., 2021). These concepts were developed to assess subtle sexism as societies become increasingly gender equal. They are thus adequate to capture sexism in European democracies today.

While group threat theory has mostly been used to explain opposition to immigration (e.g., Bobo and Hutchings, 1996), it can be applied to intergroup relations more generally, and in this case to gender relations. Studies show that perceived competition is an important driver of perceived outgroup threat, especially among ingroup members with low socioeconomic status (Bobo and Hutchings, 1996) and when perceptions of economic insecurity increase (Kuntz et al., 2017). On the contrary, other studies show that status threat perceived by high-status ingroup members, rather than economic hardship experienced by low-status ingroup members, explains support for traditional status hierarchies (Mutz, 2018). Relating status threat theory to gender relations, Grabowski et al. (2022) find that gender status threat perceptions correlate with hostile sexism, amongst others. While group and status threat theory explain threat perceptions through different mechanisms, i.e., economic or status threat perceptions, both mechanisms are related to perceived intergroup competition. Applying these theories to gender relations thus provides the framework for theorizing perceived competition as a driver of sexism.

Glick and Fiske (1996) theorize that the notion of competitive gender differences is a core component of hostile sexism, which holds that “male-female relationships are characterized by a power-struggle” (p. 507), and this notion results in men's desire to dominate women. This is in line with evidence showing that hostile sexism is related to the perception of gender relations as a zero-sum game: As women gain, men lose (Ruthig et al., 2017). Advances in women's rights may thus be perceived as a challenge to men's dominance (Glick and Fiske, 2011). This is related to the notion of envious prejudice, which Fiske et al. (1999) theorize to emerge in an ingroup in response to an outgroup that is perceived as competent. Accordingly, the outgroup's perceived group status predicts its perceived competence and competitiveness. In the case of sexism, men constitute the ingroup and women constitute the outgroup. As women become more powerful in society, men may thus perceive them as more competent and therefore as an increasing competition for their own position in society. Further, Fiske et al. (1999) theorize that perceived competence and perceived warmth condition each other in opposite directions: As an outgroup is perceived as competitive, it is also perceived as lacking warmth, and vice versa. Thus, while the ingroup respects the outgroup for their competence, they also dislike them, which the authors label “envious prejudice”. Therefore, men will develop envious prejudice toward, for example, career women, and perceive them as competent but cold individuals. Finally, the concept of modern sexism as theorized by Swim et al. (1995) reflects the above notions of competitive gender differences and envious prejudice. It captures resentment for women who push for greater economic and political power. In modern sexism, such demands are considered as demands for special favors, because discrimination against women is considered to have already ended. Overall, the currently most prominent modern conceptualizations of sexism, hostile sexism as a part of ambivalent sexism (Glick and Fiske, 1996) and modern sexism (Swim et al., 1995), thus share the component of perceived competition between men and women.

The theory that sexism is driven by perceived competition between the genders is supported by research showing that low-status men are more likely than high-status men to show hostility toward women who enter a previously men-dominated arena because low-status men will more likely lose from the hierarchy disruption caused by these women (Kasumovic and Kuznekoff, 2015). Similarly, Mansell et al. (2021) show that men become more sexist after receiving negative feedback about their performance if their performance is assessed relative to women's performance. Our study adds to the hitherto scarce research on the role of perceived competition between men and women in sexism, which Kasumovic and Kuznekoff (2015, p. 2) consider an “evolutionary” perspective on sexism.

Institutional distrust and perceived competition

We further theorize that institutional distrust is positively related to individuals' notion of competition between population groups, and in this case between men and women. Previous research suggests that the relationship between institutional (dis)trust and solidarity or tolerance between different population groups is mediated by social trust. Social trust is here defined as “confidence that people will manifest sensible and when needed, reciprocally beneficial behavior in their interactions with others” (Welch et al., 2005, 457). Rothstein and Uslaner (2005) argue that the degree to which individuals are solitary and tolerant toward minorities and “people who are not like themselves” (41), as well as the degree to which individuals believe that those with fewer resources should be granted more resources are both related to social trust. More precisely, high levels of social trust should be related to more solidarity and tolerance between population groups and therefore reduce the notion of competition between them.

While there is a large literature on determinants of social trust, Rothstein and Uslaner (2005) argue that two closely related types of equality can evoke social trust: institutional equality of opportunities and economic equality of resources. Unfair institutions that discriminate against certain people and/or are corrupt create inequality of opportunities and a culture of cheating, which in turn leads to individuals doubting people's trustworthiness in general (Kumlin and Rothstein, 2005). Similarly, economic inequality exacerbates the perceived inequality of opportunities, as some population groups possess more resources than others, and thus amplifies the social distrust created by unfair institutions (Rothstein and Uslaner, 2005). Overall, perceptions of unfair treatment by institutions go hand in hand with a social context marked by little solidarity or tolerance between different population groups.

Based on the above argument, perceived institutional fairness should be related to high levels of social trust, which in turn should create solidarity between population groups and reduce the degree to which they perceive each other as competing. For the case of men and women, the notion of competition between men and women should therefore be less prevalent when individuals perceive institutions as fair. In contrast, individuals who perceive institutions as unfair should more likely perceive competition between men and women.

Hypotheses

Building on the above theorization on the role of perceived increases in competition between men and women in sexism, we hypothesize that younger men are particularly likely to react to this competition by expressing higher levels of sexism. Because younger men are still at an early stage in their careers and personal life courses, they may perceive increased competition between men and women as more threatening to their future careers and life courses than older men who may feel that they already hold a more consolidated position in society. In contrast, women should not feel particularly threatened by increases in competition between men and women, as women's increased competitiveness relative to men should rather benefit than threaten women's position in society relative to men's2. The effect of perceived competition between men and women on young men's sexism should be particularly prominent in relatively gender-equal societies, where women are more likely to compete with men for positions of power. Given our sample of (globally speaking) relatively gender-equal European countries, we thus arrive at our first hypothesis that:

(1) Younger men are more likely than older men or women of any age group to consider advances in women's rights as a threat to men's opportunities.

Further, we hypothesize that the perception of impartial public institutions in respondents' region of residence moderates this effect. Young men who perceive public institutions as unfair will more likely consider advances in women's rights as an unfair measures resulting in unjustified special treatment of women and disadvantages for men. In contrast, young men who trust public institutions to be impartial will feel less threatened by advances in women's rights, as they will trust their institutions to act in a nondiscriminatory way. Again, older men and women of any age will generally express less sexist attitudes, even if they perceive institutions to be unfair because they do not fear the loss of opportunities as much as young men do. We thus arrive at our second hypothesis:

(2) Younger men who believe that public institutions in their area are unfair are more likely than older men or women of any age group with similar beliefs to consider advances in women's rights as a threat to men's opportunities.

Finally, we hypothesize that recent regional changes in unemployment moderate this relationship. Young men's economic prospects may be affected by increased competition stemming from increased women's labor force participation. As unemployment rises, this competition is aggravated. Again, this effect should be particularly pronounced for young men in their early careers, as older men tend to have more consolidated careers and should therefore feel less threatened by increased competition between men and women, and women of any age group should not fear losing from such competition. We thus arrive at our final hypothesis that:

(3) Younger men residing in regions with increasing unemployment rates are more likely than older men or women of any age group to consider advances in women's rights as a threat to men's opportunities.

By investigating these hypotheses, we contribute to the understanding of demographic and contextual factors' influence on individuals' sexism, as well as the role of perceived competition between men and women in sexism, especially in relatively gender-equal contexts.

Research design, sample, and data

To test the hypotheses, we rely on observational data from the latest round of the European Quality of Government Index survey (Charron et al., 2021). The EQI's fourth round survey contains a total sample of 129,991 respondents across 27 European Union member states. However, our dependent variable was asked to a sub-set of 32,469 respondents, and our sample here corresponds to such. The data was collected during autumn and winter 2020/21 at the NUTS 2 regional level, comprising 208 regions3. More on the sample, survey, and administration can be found in Appendix 1.

While the survey mainly focuses on perceptions and experiences of corruption, impartiality, and quality of public services, several additional demographic questions are included, along with some items on political values, trust, and partisanship. To proxy the opposition to advances in women's rights and capture the notion of increasing competition between men and women, we ask for agreement with the following statement: “Advancing women's and girls' rights has gone too far because it threatens men's and boys' opportunities”. Respondents were asked to place themselves on a 1–10 scale, whereby “1” indicates full disagreement and “10” indicates full agreement4. The weighted average across the sample is 3.23, which implies that the majority of citizens express disagreement with the statement and thus do not consider women's rights as a threat to men's opportunities5.

To test H1, we simply rely on two standard demographic questions, namely respondent's age and gender. Gender is considered binary (man = 1) and age is broken down into four categories: 18–29, 30–49, 50–64, and 65+6. To test whether younger men, in particular, express the highest agreement with the statement above, we construct a simple interaction between these two variables.

The test of H2 requires a proxy of one's perception of institutional impartiality. The EQI contains six such questions that ask about respondents' perceptions of the degree to which certain citizens are “favored” within certain public services, as well as the degree to which people believe everyone is ‘treated equally' (see Appendix 1 for wording). We take the battery of six questions on fairness and impartiality and construct an index (standardized via z-scores), whereby three are positively framed (stronger “agree” implies more perceived impartiality) and three are negatively framed (stronger “agree” implies less perceived impartiality). We re-scale all questions such that higher values indicate that one believes the institutions in one's area are fair and impartial. We then construct a three-way interaction between the impartiality index, the age group, and the gender of the respondent.

We test H3 via data from Eurostat on unemployment trends. To enhance the precision and increase the number of observations at the macro level, we take estimates at the regional level (NUTS 2). To proxy recent changes in employment opportunities for people in a given region, we take the difference in the long-term unemployment rates from 2019 to 2020, with positive (negative) numbers implying that unemployment has increased (decreased) during that time period. We focus on long-term unemployment to best mitigate the possible short-term and unique effects of the pandemic.

As our research design is observational, we include a number of control variables in addition to the main variables of interest to mitigate endogeneity. We include proxies of socio-economic status, income, and education, which we expect to correlate with the dependent variable, as well as with gender and age. We control for the population size of residence, as people in urban areas tend to have more progressive gender values. We also account for survey administration (online vs. telephone). In addition, in particular, for H2 where perceptions of impartiality and opposition to women's rights are most likely endogenous, we include several question items on partisanship and political values as control variables. Such controls also allow us to evaluate the construct validity of our outcome variable (Adcock and Collier, 2001)7. At the regional level for our cross-level interaction models, we control for a measure of the ‘human development index’ (HDI), which is an index of economic, health, and education development.

Our dependent variable has a non-normal, right-skewed distribution, and thus we rely on a generalized linear, negative binomial model to estimate the main models8. In the Appendix, we also replicate the generalized models with standard linear models, in which we find similar substantive effects of the variables. To account for the nested nature of the data, we employ country-fixed effects and clustered standard errors9. To adjust for differences between the sample and population, we employ post-stratification (gender, age, education, and partisanship) and design weights (population of region and country) in all models.

Empirical results

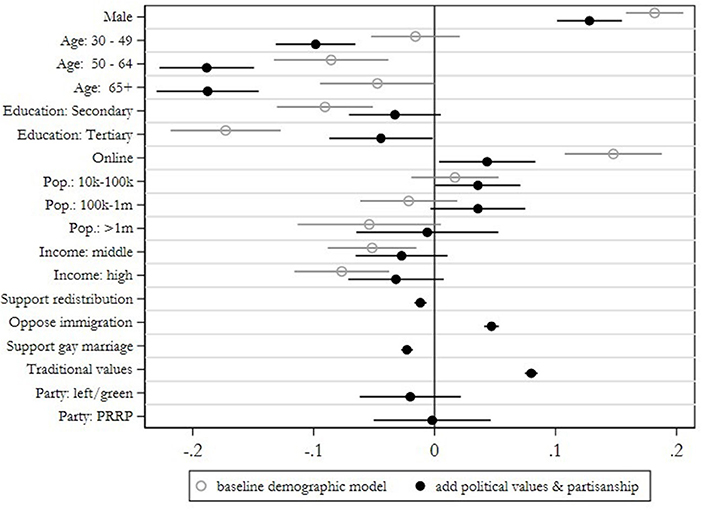

We begin with an overview of the correlates of “opposition to advances in women's rights” in Figure 1. The figure highlights two models, one with standard demographic controls (hollow circles) and the second which includes political values and partisanship (gray circles). The variables' coefficients nearly all point in the expected direction, which demonstrates validity for our outcome variable. Namely, men show greater opposition to advances in women's rights, while higher educated and higher income individuals show less opposition. Age is negatively correlated with opposition to women's rights, indicating that older individuals are less opposed to women's rights, which we unpack in the subsequent analysis. All coefficients of proxies of political values, namely economic left-right orientation (“support redistribution measures”) and GAL-TAN attitudes (“opposition to immigration”, support for “traditional values” and “support for gay marriage”) point in the expected directions, while partisan affiliation is insignificant under control for political values.

Figure 1. Covariates of opposition to advances in women's rights. Coefficients are from negative binomial estimation and express the expected change in the dependent variable from a one-unit increase in the covariate, with 95% CIs. The reference categories are: aged 18–29, less than secondary education, low income, and <10,000 inhabitants. Country fixed effects included (not shown), and standard errors clustered by region. Models include post-stratification and design weights. The number of observations for Models 1 and 2 is 31,602 and 29,299 respectively.

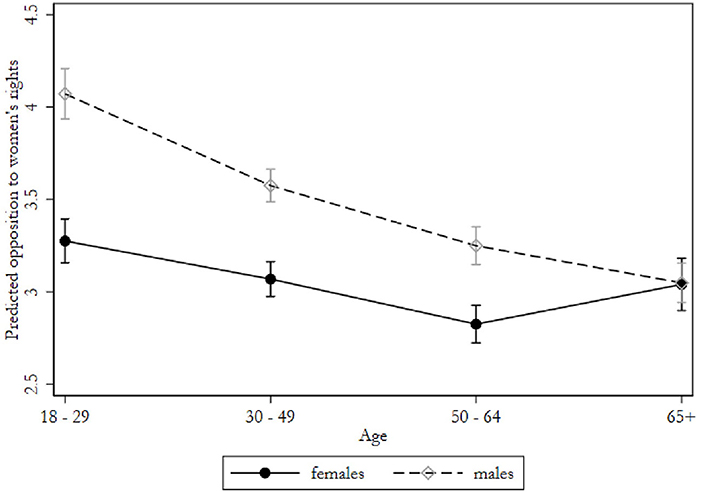

Next, we test H1, with an interaction between the age and gender variables above. Figure 2 summarizes the effect of the interaction, showing the level of opposition to advances in women's rights among men and women over the four age groups. The figure clearly shows evidence for H1: The group that expresses the most opposition toward advances in women's rights are the young men. While women across all age cohorts show very low levels of opposition to women's rights, the relationship between age and the dependent variable among men is nearly linear and negative10. Older men respondents show the lowest levels of opposition to women's rights—indistinguishable from women of the same age, which lends support to recent evidence against the idea of older generations being most opposed to changes in modern, liberal values (see Schäfer, 2021). The differences are substantively interesting, for example, the 0.8 difference in the dependent variable between young men (4.07) and young women (3.27) is slightly larger than the gap in opposition to women's rights between the average Green party (2.63) and Christian Democrat (CDU) (3.35) supporter in Germany. The 1.03 gap between the youngest and oldest cohorts of men (4.07 vs. 3.04) is equivalent to that of the average supporter of Geert Wilders' radical right Party for Freedom (PVD) and the Liberal Democrats 66 (3.94 vs. 2.93) in the Netherlands. These findings support our first hypothesis that younger men are more likely than older men or women of any age group to consider advances in women's rights as a threat to men's opportunities.

Figure 2. Test of H1: The interaction of age and gender. Predated values of the dependent variable from negative binomial estimation, with 95% CIs. Higher values of the dependent variable (y-axis) equal more opposition to advances in women's rights. Control variables from Figure 1 and country fixed effects are held constant at mean levels, and standard errors are clustered by region. All models include post-stratification and design weights.

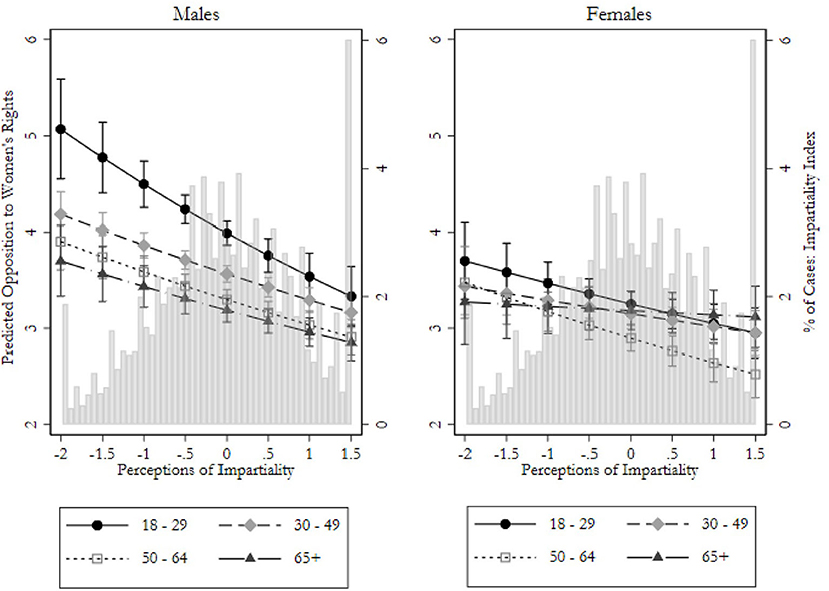

To test H2 that younger men that have perceptions of institutional unfairness and lack of impartiality will feel most threatened by advancements in women's rights, a three-way interaction term is included (age*gender*impartiality perception) in the model. The results are summarized in Figure 3. The findings are quite striking and lend evidence to the hypothesis. First, we see that women again express low levels of the dependent variable regardless of age and level of impartiality, yet the slope is negative and significant for three of the four age cohorts (save 30–49) across values of impartiality. Second, among those with a low perception of impartiality, young men clearly express greater agreement with the statement that women's rights have ‘gone too far’, and differ significantly from all other age/gender cohorts. Third, the negative slope of impartiality is steepest among young men (yet consistent among all men), and thus we observe convergence in support for advances in women's rights among people who think that their institutions are fair and impartial, as there is no significant difference between men or women of any age at high values of impartiality11.

Figure 3. Test of H2: The moderating effect of impartiality perceptions. Predated values of the dependent variable from negative binomial estimation, with 95% CIs. Higher values of the dependent variable (y-axis) equal more opposition to advances in women's rights. Control variables from Figure 1 and country fixed effects are held constant at mean levels, and standard errors are clustered by region. All models include post-stratification and design weights.

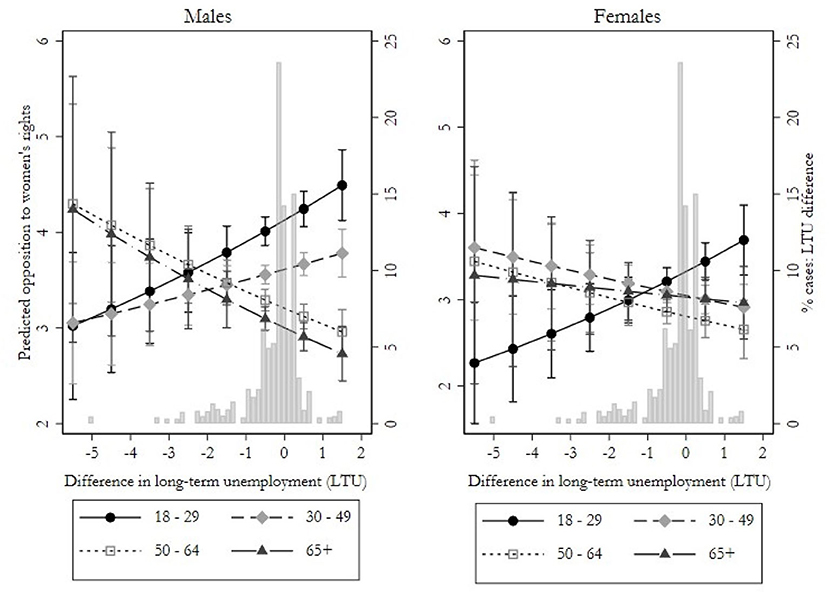

Finally, we move to our test of H3, which predicts that younger men, in particular, will demonstrate the greatest opposition to advances in women's rights for reasons of relative competition in the labor force. We proxy this via our measure of recent changes in the structural, long-term unemployment rates at the regional level and include a three-way interaction with this unemployment variable and the age/gender variables. Figure 4 summarizes the findings of the interaction. We see three noteworthy results from this test. First, there is a clear relationship between age and the outcome variable over the range of unemployment changes among men. In line with our hypothesis, increases in unemployment are positively related to the dependent variable among younger men—with the steepest slope among the 18–29 cohort. For example, comparing the predicted level of opposition of young men in regions where unemployment has declined the most (3.19) vs. increased the most (4.55) is equivalent to the gap between the average supporters of the Social Democrats (Partito Democratico) and center-right Forza Italia in Italy (2.8 vs. 4.1). Yet, among men 50 and older, there is a negative slope, demonstrating a divergence of opinion among men as the relative change in unemployment increases. When comparing the dependent variable between the youngest and oldest cohorts of men in regions where unemployment increased by 1% (the 95%ile), we see a predicted gap of 1.65 (4.34 vs. 2.79), which is larger than the difference between the average left-wing Podemos supporter and the average right-wing Partido Popular (PP) supporter in Spain (2.42 vs. 3.86). Among women, age does not significantly distinguish the dependent variable for 95% of the distribution of long-term unemployment. We see that the three cohorts aged 30 and older show virtually the same low levels of opposition to advances in women's rights regardless of relative changes in unemployment. In contrast, younger women show less opposition to advances in women's rights as more employment opportunities have come to their region in recent times. Yet at higher levels of the moderating variable (i.e., relative increases in structural unemployment), we see that the levels of the dependent variable converge among all age cohorts for women for the vast majority of the distribution of the moderating variable.

Figure 4. Test of H3: The moderating effect of relative changes in unemployment. Predated values of the dependent variable from negative binomial estimation, with 95% CIs. Higher values of the dependent variable (y-axis) equal more opposition to advances in women's rights. This figure shows the triple interaction between age, gender, and change in unemployment, with a histogram of the distribution of the change in long-term unemployment. Control variables from Figure 1, regional HDI, the long-term unemployment rate in 2019, and country fixed effects are held constant at mean levels, and standard errors are clustered by region. All models include post-stratification and design weights.

Alternative specifications and other robustness checks

We begin by checking several potential relationships in the data that we view as empirical implications of our findings. First, as our theory relies on a mechanism of competition, one implication of our results is that young men who perceive public education as unfair will more likely perceive advances in women's rights as a threat, as this institution, in particular, is key for career opportunities and advancements in the labor market. Given that girls outperform boys in school, on average (e.g., Pomerantz et al., 2002), young men may perceive competition between men and women in public education as unfair in particular. We test whether the findings for H2 are equally or even more pronounced among men and women of different age groups if moderated by only the education items of the impartiality index (Appendix Figure A4). Indeed, we find that opposition to advances in women's rights among young men is highly driven by perceptions of education impartiality. Moreover, opposition to advances in women's rights is not moderated by perceptions of education impartiality for any of the other age groups among men, nor among women at all. Thus, we interpret this as further evidence that perceived competition (i.e., perceived fairness in key institutions) is a driving factor in young men's opposition to advances in women's rights. Second, again regarding H2, we check whether the context of impartiality matters (via 2017 impartiality scores of the EQI, Charron et al., 2019) in the interaction with age and gender. We do not find that the level of threat perception of advances in women's rights among young men depends on the context of “actual” fairness. Rather, it is the individual-level perception that matters most for our findings.

Third, we test the moderating effect of the contextual level of gender equality in the area in which respondents live. We approximate the contextual level of gender equality using data on the proportion of women in local governance (Sundström and Wängnerud, 2016). This could serve as an additional heuristic of contextual competition where higher proportions of women in local governance would imply higher levels of local gender equality and therefore higher (perceived) competition between men and women. We find here that there is in fact a divergence in opposition to advances in women's rights among younger men vs. older men, whereby opposition to advances in women's rights increases among the former group and decreases in the latter groups as a function of the local level of gender equality. This could suggest further evidence for the moderating effect of (perceived) competition between men and women on young men's opposition to advances in women's rights. In contrast, attitudes toward advances in women's rights among women respondents are unaffected by this moderator (Appendix Figure A5).

In addition, we replicate several of the main models using alternative specifications and alternative measures to test the robustness of the findings. First, we re-run the findings for Appendix Figure A1 using a linear, OLS model (Appendix Figure A1). Second, we check the sensitivity of the age categories as such and replicate Figure 2 using a continuous measure of age (Appendix Figure A2). Third, we show the test of H3 using recent changes in the unemployment rate rather than the long-term unemployment rates (Appendix Figure A3). In all cases, we find results that correspond with our main findings.

Discussion

Our empirical findings suggest that young men are particularly likely to perceive advances in women's rights as a threat to men's opportunities (H1), especially if they perceive institutions as unfair (H2) and if they reside in regions observing increases in unemployment (H3), lending support to all our hypotheses. These findings entail several empirical and theoretical contributions to the literature on modern sexism, as well as some limitations.

Empirically, first, our study measures and explains modern sexism across all 27 European Union countries using representative survey data at the subnational level, which allows us to test for demographic and contextual factors explaining modern sexism. It thereby contributes to previous research on sexism that is often based on unrepresentative samples in one or a few countries and therefore cannot make inferences on demographic or contextual factors. Second, we develop an original measure of modern sexism that captures the element of perceived competition between men and women, which we theorize to be a core component of young men's modern sexism in relatively gender-equal societies. While previous research mostly uses established question batteries to measure sexism and there is much merit in assessing sexism as the complex concept it is, focusing on one component of sexism contributes to understanding how drivers of different components of modern sexism can result in different levels of modern sexism across population groups, depending on their demographics and contexts.

Theoretically, we contribute to previous research by explaining the rise of modern sexism in a population group that is usually considered rather progressive: young men in relatively gender-equal societies. We do so by theorizing that young men are particularly likely to feel threatened by perceived increases in competition between men and women because they are most likely to fear that their future life courses are affected by this competition. Our findings contradict the cultural backlash theory (Norris and Inglehart, 2019), which argues that older generations hold more socially conservative values than younger generations due to generational value change. As it seems, inter-generational differences in modern sexism are not fully explained by generational value change. Rather, our findings suggest that another mechanism may be at play: perceived competition between men and women for (future) power in society. These findings lend support to “evolutionary” (Kasumovic and Kuznekoff, 2015) rather than ideological explanations of sexism. Future research may further explore how different mechanisms lead to sexism in different population groups. For instance, while ideological explanations of sexism may better explain old generations' sexism, we demonstrate that evolutionary explanations of sexism better explain young men's sexism. There may thus be a U-shaped relationship between age and sexism, wherein potentially different types of sexism may be driven by different mechanisms for young men and older generations.

Further, we theoretically contribute to the literature on sexism and potentially the literature on prejudice more generally in relation to perceived institutional fairness. Our findings suggest that perceptions of unfair institutions are an important explanatory factor of sexism, especially among those who are most likely to fear competition between men and women, i.e., young men. Notions of competition between men and women may thus particularly result in modern sexism if this competition is perceived as unfair and as favoring women over men. This speaks to the research on how institutional trust is related to social trust, which in turn affects solidarity and tolerance (or inversely: prejudice) between different population groups (Kumlin and Rothstein, 2005; Rothstein and Uslaner, 2005). Our findings support this theory and test its implications for the case of sexism. Future research may investigate whether the same mechanism holds for other types of prejudice, such as prejudice based on race or ethnicity.

Finally, our findings are in line with modernization theory suggesting that economic development and existential security will eventually lead to the development of emancipative values, where emancipative values include gender equality (Inglehart and Baker, 2000; Welzel, 2013). We find that young men express particularly high levels of sexism in regions observing increasing unemployment. In light of modernization theory, this finding suggests that increased competition for jobs may trigger existential insecurity and therefore reduce tolerance toward out-groups, resulting in sexism fueled by the notion of competition between men and women. Finally, our subnational variation allows us to test the implications of modernization theory in the relatively developed contexts of European Union countries, which are expected to promote emancipative values. We show that, even in developed contexts, subnational variation in development can explain the lack of emancipative values in the case of sexism.

Our study is subject to several limitations. First, our measure of modern sexism includes only one component of sexism, i.e., the notion of competition between men and women. While our theory and findings suggest that there is value in investigating single components of sexism because different components may drive sexism in different population groups, future research may focus on other individual components of modern sexism. Second, our measure of perceived institutional fairness is endogenous to political attitudes and values, and thus sexism. Whether an individual perceives institutions as unfair may not reflect actual institutional impartiality. While we address this problem by controlling for various political attitudes, we are unable to claim that institutional impartiality is related to sexism based on the findings in this study. Further, our data does not allow us to make claims on the direction of the relationship between perceived institutional fairness and sexism. Future research may further explore the relationship between actual and perceived institutional impartiality and sexism. Third, given the spatial nature of our data, we cannot distinguish between age and cohort—that is to say, if there is something specific about this particular group of young men (i.e., “Gen Z”/ young Millennials) or if the findings would apply to all young men irrespective of the cohort. Thus, more data over time would have to be collected to assess this distinction. Fourth, our data was collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, during which many people experienced increased levels of economic insecurity. We address this problem by using changes in long-term unemployment, rather than short-term unemployment, as our contextual-level moderating variable. However, the deteriorating existential security experienced during the pandemic may have affected respondents' response to our sexism measure, as modernization theory would predict. Future studies may thus use data collected in periods of relative (economic) stability.

Finally, our theory is unable to explain our findings that older men are more sexist in regions with decreasing unemployment, and younger women are more sexist than older women in regions observing increasing unemployment. Future research may further explore this phenomenon.

Conclusion

This study theorizes and empirically demonstrates that young men are most likely to perceive advances in women's rights as a threat to men's opportunities, i.e., as competition, compared to men of other age groups and women of any age groups. We further show that this is particularly the case for young men who perceive institutions in their regions as unfair, and young men who reside in regions that observe increases in long-term unemployment resulting in increased job competition. In other words, young men who live in conditions that make them more likely to perceive competition as (a) unfair and (b) growing are particularly likely to consider women's rights advances as a threat. This is shown based on survey data analysis of representative samples from all 27 European Union countries at the subnational NUTS 2 level (n = 32,469).

These findings contribute to four different lines of research. First, the large-scale cross-country analysis of demographic and contextual factors, and the focus on one particular component of modern sexism, i.e., competition between men and women, expand previous research on modern sexism. Second, our findings that young men are most likely to express this type of sexism contradict the cultural backlash theory that argues that old generations are most likely to hold socially conservative values due to generational value change. We thus suggest that the notion of competition between men and women operates in a different way than generational value change, and the different mechanisms drive sexism in different population groups. Third, we speak to the literature on the relationship between institutional trust and prejudice by confirming the theorized expectations for the case of sexism. Future research may investigate this relationship for other types of prejudice. Fourth, we contribute to modernization theory by theorizing and testing why sexism emerges in highly developed contexts such as the European Union countries. While modernization theory holds that these contexts should promote emancipative values, we suggest that these contexts may simultaneously evoke a notion of competition between men and women that potentially increases sexism among young men and challenges these values precisely because there is a level of gender equality that allows women to take certain jobs or political offices.

On the one hand, this study suggests that modern sexism in young men may be addressed by improving institutions' impartiality and institutional trust, as well as creating employment opportunities. In addition, improved communication on the potential advantages of women in societal power positions to young men, in particular, could mitigate modern sexism. On the other hand, the study's findings reveal an important challenge for the implementation of gender equality measures across European Union member states: young men's perception of women's rights as a threat, which may become particularly strong in times of economic downturns.

Data availability statement

Replication material for this study is openly available at: https://zenodo.org/record/6940021#.YuParIRBw2x.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

GO wrote the introduction, literature, theory, discussion, and concluding sections. NC conducted the empirical analysis and wrote the methods and results sections. AA provided particular input on theoretical perspectives. All authors contributed to the theoretical development, research design, and the design of the measurement, commented on the manuscript on several occasions, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project was partially funded by a grant from the European Commission, DG Regio [No. 2019CE160AT022].

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers, Nicholas Sorak and participants of the QoG conference in February 2022 for helpful comments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.909811/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Given that we measure perceived institutional impartiality rather than actual institutional impartiality, we cannot treat this indicator as a truly contextual factor. Residents of regions with high institutional impartiality may also perceive institutions to be unfair, depending on their political beliefs and personal experiences.

2. ^Conservative women may constitute an exception to this and also feel threatened by changing norms on women's role in society, as they may fear to lose status and recognition for their way of living relative to women who do not adhere to traditional gender roles.

3. ^Given that the sexism question is only asked in the most recent 2021 EQI survey wave, we can only analyze one time period.

4. ^We pre-tested the questions in a pilot study in Germany, Italy and Romania in May 2020 (n = 3,000, 1,000 per country) and found the item to be highly correlated with other proxies of social conservatism, such as partisanship and other GAL-TAN proxies.

5. ^Roughly 2.5% responded “don't know/refuse” and these are dropped from the main analyses, resulting in a relevant sample of 31,602. We checked if the non-responses were systematically linked with our main variables of interest via logistic model (see Appendix Figure A6). We find that while low-educated responded tend to have higher non-responses rates, our main variables of gender, age, impartiality and unemployment are all non-significant predictors of non-response.

6. ^While the data only allows for a binary operationalization of gender, we acknowledge the existence of other genders than men and women.

7. ^We report further validity and equivalence checks of the dependent variable in Appendix, Section Checking the Validity and Equivalence of the Measure of Sexism across the Sample.

8. ^Tests for the Poisson model showed evidence of overdispersion, and thus the negative binomial estimation is used here.

9. ^An empty hierarchical model shows that just 2.5% of the unexplained variation is at the country level, while the remaining is at the individual level.

10. ^In Appendix Figure A2, we replicate the interaction using a continuous measure of age rather than the categorical variables. We find the linear effects are nearly identical.

11. ^In Appendix Figure A7, we provide a histogram of the distribution of impartiality perceptions among the young men cohort.

References

Adcock, R., and Collier, D. (2001). Measurement validity: a shared standard for qualitative and quantitative research. Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 95, 529–546. doi: 10.1017/S0003055401003100

Akrami, N., Ekehammar, B., and Yang-Wallentin, F. (2011). Pers. and social Psychol. factors explaining sexism. J. Individ. Diff. 32, 153 doi: 10.1027/1614-0001/a000043

Alexander, A. C., Inglehart, R., and Welzel, C. (2016). Emancipating sexuality: Breakthroughs into a bulwark of tradition. Soc. Indicat., 129, 909–935. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-1137-9

Alexander, A. C., and Welzel, C. (2011). Empowering women: the role of emancipative beliefs. Eur. Soc. Rev., 27, 364–384. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcq012

Bobo, L., and Hutchings, V. L. (1996). Perceptions of racial group competition: Extending Blumer's theory of group position to a multiracial social context. Am. Soc. Rev. 1, 951–972. doi: 10.2307/2096302

Cabezas, M. (2022). Silencing feminism? Gender and the rise of the nationalist far right in Spain. Signs 47, 319–345. doi: 10.1086/716858

Charron, N., Lapuente, V., and Annoni, P. (2019). Measuring quality of government in EU regions across space and time. Papers Reg. Sci. 98, 1925–1953. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12437

Charron, N., Lapuente, V., and Bauhr, M. (2021). Sub-national Quality of Government in EU Member States: Presenting the 2021 European Quality of Government Index and its Relationship with |-19 Indicators (No. 2021, 4.).

Christopher, A. N., and Mull, M. S. (2006). Conservative ideology and ambivalent sexism. Psychol. Women Q. 30, 223–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00284.x

Christopher, A. N., and Wojda, M. R. (2008). Social dominance orientation, right-wing authoritarianism, sexism, and prejudice toward women in the workforce. Psychol. Women Q. 32, 65–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00407.x

Cowie, L. J., Greaves, L. M., and Sibley, C. G. (2019). Sexuality and sexism: differences in ambivalent sexism across gender and sexual identity. Pers. and Individ. Differences, 148, 85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.023

Darakchi, S. (2019). “The Western Feminists Want to Make Us Gay”: Nationalism, Heteronormativity, and Violence Against Women in Bulgaria in Times of “Anti-gender Campaigns”. Sexuality and Culture, 23, 1208–1229. doi: 10.1007/s12119-019-09611-9

Faludi, S., Shames, S., Piscopo, J. M., and Walsh, D. M. (2019). A Conversation with Susan Faludi on Backlash, Trumpism, and #MeToo. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 45, 336–345. doi: 10.1086/704988

Fiske, S. T., Xu, J., Cuddy, A. C., and Glick, P. (1999). (Dis) respecting vs. (dis) liking: Status and interdependence predict ambivalent stereotypes of competence and warmth. J. Soc. Issues, 55, 473–489. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00128

Fitzpatrick Bettencourt, K. E., Vacha-Haase, T., and Byrne, Z. S. (2011). Older and younger adults' attitudes toward feminism: the influence of religiosity, political orientation, gender, education, and family. Sex Roles 64, 863–874. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-9946-z

Glick, P., and Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 491–512. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

Glick, P., and Fiske, S. T. (2011). Ambivalent sexism revisited. Psychol. Women Q. 35, 530–535. doi: 10.1177/0361684311414832

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., and Castro, Y. R. (2002). Education and Catholic religiosity as predictors of hostile and benevolent sexism toward women and men. Sex Roles 47, 433–441. doi: 10.1023/A:1021696209949

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., Fiske, S. T., Eckes, T., Masser, B., Volpato, C., et al. (2004). Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 86, 713. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.713

Goldin, C. (2014). A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter. Am. Econ. Rev. 104, 1091–1119. doi: 10.1257/aer.104.4.1091

Grabowski, M., Dinh, T. K., Wu, W., and Stockdale, M. S. (2022). The sex-based harassment inventory: a gender status threat measure of sex-based harassment intentions. Sex Roles 27, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11199-022-01294-1

Green, J., and Shorrocks, R. (2021). The Gender Backlash in the Vote for Brexit. Pol. Behav. 3, 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s11109-021-09704-y

Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., and Twenge, J. M. (2014). Psychol. entitlement and ambivalent sexism: Understanding the role of entitlement in predicting two forms of sexism. Sex Roles 70, 209–220. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0360-1

Grzebalska, W., and Peto, A. (2018). The gendered modus operandi of the illiberal transformation in Hungary and Poland. Women's Stud. Int. Forum 68, 164–172. Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2017.12.001

Hammond, M. D., Milojev, P., Huang, Y., and Sibley, C. G. (2018). Benevolent sexism and hostile sexism across the ages. Soc. Psychol. Per. Sci. 9, 863–874. doi: 10.1177/1948550617727588

Hammond, M. D., Sibley, C. G., and Overall, N. C. (2014). The allure of sexism: Psychology entitlement fosters women's endorsement of benevolent sexism over time. Soc. Psychol. Per. Sci. 5, 422–429. doi: 10.1177/1948550613506124

Hart, J., Hung, J. A., Glick, P., and Dinero, R. E. (2012). He loves her, he loves her not: attachment style as a Pers. antecedent to men's ambivalent sexism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38, 1495–1505. doi: 10.1177/0146167212454177

Hellmer, K., Stenson, J. T., and Jylhä, K. M. (2018). What's (not) underpinning ambivalent sexism?: Revisiting the roles of ideology, religiosity, Person., demographics, and men's facial hair in explaining hostile and benevolent sexism. Pers. Individ. Diff. 122, 29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.001

Huddy, L., Neely, F. K., and Lafay, M. R. (2000). Trends: Support for the women's movement. Public Opin. Q. 64, 309–350. doi: 10.1086/317991

Inglehart, R., and Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. Am. Soc. Rev. 19–51. doi: 10.2307/2657288

Inglehart, R., and Norris, P. (2003). Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Kantola, J., and Lombardo, E. (2017). Gender and the Economic Crisis in Europe: Politics, Institutions and Intersectionality (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-50778-1

Kasumovic, M. M., and Kuznekoff, J. H. (2015). Insights into sexism: Male status and performance moderates female-directed hostile and amicable behaviour. PloS ONE 10, e0131613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131613

Kuhar, R., and Paternotte, D. (2018). Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe. Mobilizing Against Equality (London, UK: Rowman and Littlefield International).

Kumlin, S., and Rothstein, B. (2005). Making and breaking social capital: The impact of welfare-state institutions. Comp. Pol. Stud. 38, 339–365. doi: 10.1177/0010414004273203

Kuntz, A., Davidov, E., and Semyonov, M. (2017). The dynamic relations between Econ. conditions and anti-immigrant sentiment: a natural experiment in times of the European Economic crisis. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 58, 392–415. doi: 10.1177/0020715217690434

Mansell, J., Harell, A., Thomas, M., and Gosselin, T. (2021). Competitive loss, gendered backlash and sexism in politics. Pol. Behav. 1–22. doi: 10.1007/s11109-021-09724-8

Maxwell, A., and Shields, T. (2019). The Long Southern Strategy: How Chasing White Voters in the South Changed American Politics (USA: Oxford University Press).

Mosso, C., Briante, G., Aiello, A., and Russo, S. (2012). The role of legitimizing ideologies as predictors of ambivalent sexism in young people: Evidence from Italy and the USA. Soc. Just. Res. 26, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s11211-012-0172-9

Mutz, D. C. (2018). Status threat, not Econ. hardship, explains the 2016 presidential vote. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, E4330–E4339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718155115

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press). doi: 10.1017/9781108595841

Pomerantz, E. M., Altermatt, E. R., and Saxon, J. L. (2002). Making the grade but feeling distressed: Gender differences in academic performance and internal distress. J. Educ. Psychol. 94, 396. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.94.2.396

Ratliff, K. A., Redford, L., Conway, J., and Smith, C. T. (2019). Engendering support: hostile sexism predicts voting for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 US presidential election. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 22, 578–593. doi: 10.1177/1368430217741203

Roets, A., Van Hiel, A., and Dhont, K. (2012). Is sexism a gender issue? A motivated social cognition perspective on men's and women's sexist attitudes toward own and other gender. Eur. J. Person. 26, 350–359. doi: 10.1002/per.843

Rosenthal, L., Levy, S. R., and Militano, M. (2014). Polyculturalism and sexist attitudes: Believing cultures are dynamic relates to lower sexism. Psychol. Women Q., 38, 519–534. doi: 10.1177/0361684313510152

Rothstein, B., and Uslaner, E. M. (2005). All for all: Equality, corruption, and social trust. World Pol. 58, 41–72. doi: 10.1353/wp.2006.0022

Rubery, J. (2015). Austerity and the Future for Gender Equality in Europe. ILR Rev. 68, 715–741. doi: 10.1177/0019793915588892

Russell, B. L., and Trigg, K. Y. (2004). Tolerance of sexual harassment: an examination of gender differences, ambivalent sexism, social dominance, and gender roles. Sex Roles 50, 565–573. doi: 10.1023/B:SERS.0000023075.32252.fd

Ruthig, J. C., Kehn, A., Gamblin, B. W., Vanderzanden, K., and Jones, K. (2017). When women's gains equal men's losses: predicting a zero-sum perspective of gender status. Sex Roles 76, 17–26. doi: 10.1007/s11199-016-0651-9

Schäfer, A. (2021). Cultural Backlash? How (not) to explain the rise of authoritarian populism. Br. J. Pol. Sci., 1–17. doi: 10.1017/S0007123421000363

Sibley, C. G., Wilson, M. S., and Duckitt, J. (2007). Antecedents of men's hostile and benevolent sexism: the dual roles of social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 33, 160–172. doi: 10.1177/0146167206294745

Sundström, A., and Wängnerud, L. (2016). Corruption as an obstacle to women's political representation: evidence from local councils in 18 European countries. Party Pol. 22, 354–369. doi: 10.1177/1354068814549339

Swim, J. K., Aikin, K. J., Hall, W. S., and Hunter, B. A. (1995). Sexism and racism: old-fashioned and modern prejudices. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 68, 199. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.68.2.199

Van Assche, J., Koç, Y., and Roets, A. (2019). Religiosity or ideology? On the individual differences predictors of sexism. Pers. Individ. Diff. 139, 191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.016

Welch, M. R., Rivera, R. E. N., Conway, B. P., Yonkoski, J., Lupton, P. M., Giancola, R., et al. (2005). Determinants and consequences of social trust. Soc. Inquiry, 75, 453–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.2005.00132.x

Keywords: modern sexism, young men, institutional trust, unemployment, competition between men and women

Citation: Off G, Charron N and Alexander A (2022) Who perceives women's rights as threatening to men and boys? Explaining modern sexism among young men in Europe. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:909811. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.909811

Received: 31 March 2022; Accepted: 18 July 2022;

Published: 15 August 2022.

Edited by:

Angela Smith, University of Sunderland, United KingdomReviewed by:

Vera Lomazzi, University of Bergamo, ItalyMelanee Thomas, University of Calgary, Canada

Copyright © 2022 Off, Charron and Alexander. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gefjon Off, Z2Vmam9uLm9mZkBndS5zZQ==

Gefjon Off

Gefjon Off Nicholas Charron

Nicholas Charron Amy Alexander

Amy Alexander