- 1Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, United States

- 2College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University, Collegeville, MN, United States

Dilma Rousseff's presidency ended in controversial form. The first woman elected to the position in Brazil, Rousseff's 2016 impeachment was seen as a coup by her supporters and as a necessary step for democracy by her detractors. With the Brazilian economy facing its worst recession in history and the Car Wash corruption scandal ravaging the political class, critics continually raised questions about Rousseff's leadership style and abilities. This article analyzes how this criticism in part can be attributed to gendered subjective understandings of preferred leadership traits. Using a thematic analysis of interviews with political actors in five different Brazilian states conducted in 2017 and 2018, we demonstrate that gender stereotypes and sexism fueled criticisms about women's political leadership. While Rousseff's presidency was riddled with problems, the president's leadership style and abilities were scrutinized in distinct gendered ways, indicating a gendered double bind and a backlash against women in politics.

Introduction

In March of 2009, during a conference called “More Women in Power,” then Chief of Staff Dilma Rousseff addressed her infamous brash personality: “In the spheres of power, a woman stops being seen as fragile, and that's unforgivable. This is where the history of the tough woman starts. It is true. I am a tough woman surrounded by tender men” (de Gois, 2009)1. At that time, Rousseff held Brazil's most powerful cabinet position, and rumors of a presidential run were gaining traction. Seven years later, after a successful presidential election campaign in 2010 and a victorious though contentious reelection in 2014, Rousseff was impeached and ultimately removed from power in 2016. Throughout Rousseff's tenure and especially during the impeachment proceedings, political actors and the general population questioned her leadership skills and fitness for office (Zdebskyi et al., 2015; de Bolle, 2016; Dantas, 2019; dos Santos and Jalalzai, 2021).

Using a thematic analysis of original interviews with political actors, we demonstrate that gender stereotypes and sexism fueled criticisms of Rousseff, constituting a backlash against women's political leadership more broadly. Presidents of Brazil regularly face intense scrutiny. Fernando Collor de Melo's 1992 impeachment proceedings (Villa, 2016) and Jair Bolsonaro's current confrontations (Hunter and Power, 2019) are just two examples. While Rousseff's presidency was riddled with issues, including one of the largest corruption scandals ever uncovered (Watts, 2017; Ellis, 2018) and a severe economic crisis (de Bolle, 2016; dos Santos and Jalalzai, 2021), the President's leadership style and abilities were scrutinized in distinct gendered ways, suggestive of backlash against women in politics.

Male dominated systems have slowly ceded women political rights, first with suffrage followed by formal and informal procedures solidifying women's rights to hold elected office (Towns, 2019). The modern political system has allowed for a gradual increase in the number of women in politics: as of 2021, women hold 25 percent of parliamentary positions worldwide, including 28 percent of women holding deputy speaker of parliament positions and 21 percent of speaker of the parliament positions (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2021). While gains have been constant since the second half of the twentieth century, these numbers are still disappointing given that women constitute roughly half of the world's population. The figures are more skewed when analyzing elected national executive positions. A mere 54 women have been elected to such posts in modern history, meaning the ratio of women elected to men is derisorily low (Reyes-Housholder, 2021). Even when including non-elected executive positions, far<10 percent of all presidents and prime ministers worldwide are women, which reinforces the masculine nature of this institution (Baturo and Gray, 2018; Jalalzai, 2019).

This research contributes to the growing literature on women in executive power worldwide (Genovese and Steckenrider, 2013; Jalalzai, 2013; Thames and Williams, 2013; Skard, 2014; Montecinos, 2017; Baturo and Gray, 2018; Wiltse and Hager, 2021) and in Latin America (Jalalzai, 2015; Reyes-Housholder, 2016, 2019; Waylen, 2016; Reyes-Housholder and Thomas, 2018; dos Santos and Jalalzai, 2021). Globally, numbers of women presidents and prime ministers have more than tripled since 1960, the first year a woman governed as a prime minister (Jalalzai, 2019). In Latin America, women started to make noticeable presidential gains; in 2010, four countries in the region had female presidents and all were elected by the popular vote (Jalalzai, 2015). The “wave” of women presidents in Latin America, however, proved short-lived. When Michelle Bachelet's second term in Chile ended in March 2018, no women presidents remained. It was not until January 2022 that another (elected) woman served as president (Ernst, 2021).

By focusing on the gendered obstacles women confront once in power, this article expands the literature on women executives. Scholars have addressed conditions facilitating or obstructing women's ascensions such as institutional arrangements and structural factors (Jensen, 2008; Jalalzai, 2013; Lee, 2017; Baturo and Gray, 2018; Wiltse and Hager, 2021). Increasingly, explorations assess whether and how women prime ministers and presidents affect women's political empowerment as policy makers, cabinet selectors, and symbols (Jalalzai, 2015, 2019; Reyes-Housholder and Schwindt-Bayer, 2016; Adams, 2017; dos Santos and Jalalzai, 2021). We aim to contribute to the relatively understudied area of gendered perceptions and governance for women presidents.

Gendered double bind and misogynistic backlash

Given recent setbacks of women presidents including Park Geun-hye of South Korea and Dilma Rousseff, both impeached, scholars must better understand whether women face greater scrutiny for lackluster performances in their leadership capacities or alleged engagement in inappropriate behavior. Some evidence suggests that women executives indeed are judged more harshly. Carlin et al. (2019) find that women presidents are less popular and face more extreme approval changes than their male counterparts, especially in issues related to security and corruption. Reyes-Housholder (2019) provides confirmation that women presidents of Latin America encounter greater pressure to offer moral leadership, being viewed more negatively than their male colleagues in contexts of presidential scandal and executive corruption.

Our study extends research on the double-bind and misogynistic backlash women in politics face, specifically women presidents. The double bind “emerges when desirable traits require more investment or are associated with different burdens, for members of non-dominant groups” (Teele et al., 2018, p. 525). Manne (2018, p. 34) defines misogyny as “a system that polices, punishes, dominates, and condemns those women who are perceived as an enemy or threat to the patriarchy.” Women challenging the status quo are punished for deviating from the prevailing norm.

The gendered double bind is a complex phenomenon that likely influenced the behavior of President Dilma Rousseff in distinct ways, including her attempts to comply with gendered assumptions of leadership and to challenge or defy these assumptions. In that context, the consequences of complying and challenging gendered assumptions led to very distinct reactions from political actors. Another theme connecting Rousseff's presidency to the gendered double bind was the constant comparison between her leadership (and leadership style) to that of the men preceding and following her in the presidency, as well as comments about how Rousseff would have been treated differently if she was a man. In our thematic analysis we observed a pattern where comments relating Rousseff's challenge of gendered assumptions and those emphasizing the comparison of her leadership to that of men were followed by or included discussions about the backlash suffered by the President, overwhelmingly defined as misogyny or misogynistic acts against her.

Rousseff was not the only president who has endured the challenges of being a woman in a position of executive leadership. Other women presidents such as Michelle Bachelet, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, and Laura Chinchilla dealt with similar issues. One of the many challenges women presidents face is gaining a seat at the table in the first place. As Schwindt-Bayer puts it, “Women face a political environment long dominated by men in which it is difficult for women to break into the informal networks that underlie the power structure” (Schwindt-Bayer, 2010, p. 32). This makes it difficult for women to gain access to essential political resources and keeps them marginalized in the political world. Jalalzai expands on this stating, “executive power arrangements are masculine because they are centralized and hierarchical, making it difficult for women to break into these roles” (Jalalzai, 2010, p. 140). The structure of executive leadership positions itself hinders the ability of women to get positions of executive leadership, but this does not mean that women have not attempted to win executive elections. For example, by 2013 at least 38 women in 25 African countries had sought the presidency but only one was successful, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (Jalalzai, 2013). As mentioned, in 2014, there were even four women presidents governing at the same time. Now in 2022, only one woman holds a presidential position in Latin America. The presidency has been a historically masculine office. Although more women are changing this narrative, this does not constitute a significant shift in roles and expectations. Electing a few women to the highest office “might be seen as achieving some cracks in the ceiling...to eliminate the glass ceiling completely will take much more than women reaching the highest office” (Cortès-Conde and Boxer, 2015, p. 65).

Societal gender dynamics dictate expectations for political leaders as well as understandings of leadership traits in politics and beyond. In any position, women must break down barriers and demonstrate their belonging (Ragins et al., 1998; Jalalzai, 2013; Baumann, 2017). Long established gendered logics determine professional expectations ascribing certain “feminine” and “masculine” behaviors as acceptable or unacceptable (Acker, 2012), normally placing ascribed positive masculine traits and behaviors as desirable leadership traits. The gendered institutions and norms shaping society, and more specifically, influencing our understandings of leadership, lead to distinct expectations for women (Jamieson, 1995). Individuals prefer leaders who possess stereotypically masculine “agentic” traits (such as assertiveness, confidence, forcefulness, dominance) rather than communal traits associated with women (Eagly and Karau, 2002; Eagly and Carli, 2007; Koenig et al., 2011). When women demonstrate masculine traits, they face backlash for violating expected gendered behaviors (Jamieson, 1995; Rudman, 1998; Eagly and Karau, 2002; Valdini, 2019).

The national executive political space has been historically constructed for men and by men, evident by the lack of women as prime ministers and presidents (Jalalzai, 2013). Women's presence in political leadership creates a social role incongruency that impacts how individuals evaluate and react to a woman leader's performance (Rosette et al., 2015). Status incongruity describes the resistance individuals experience when they act contrary to social role expectations (Rudman et al., 2012). This can lead to a double bind. And while some evidence suggests that women in politics are not necessarily more likely to receive negative reactions due for displaying assertiveness (Brooks, 2011; Karl and Cormack, 2021; Hargrave and Blumenau, 2022), there is limited research on what happens when the national chief executive is a woman and displays such characteristics. These gendered assumptions about leadership traits place unique pressures on women, often putting them in an irreconcilable place in this rhetorical space where women's identity construct exists as only one of two alternatives: feminine or competent. “To be a woman (i.e., to have a womb) and to perform feminine qualities conflicts with the perceptions of competence” (Harp et al., 2016, p. 195). Power is attributed to men, meaning that to be a woman is to lack power. As Jamieson (1995, p. 14) states, the double bind is “constructed to deny women access to power and, where individuals manage to slip past their constraints, to undermine their exercise of whatever power they achieve.” Women must then keep an “appropriate” attitude to be considered qualified enough to do their job. They carry the daunting task of acting somewhere between masculine and feminine, but it “is challenging and often at odds with women's identity and experienced conflicts between life and work” (Bierema, 2016, p. 119). Therefore, “every woman is the wrong woman” (Anderson, 2017, p. 132) because women cannot find the right balance to femininity and masculinity to be considered competent. “Women who are considered feminine will be judged incompetent, and women who are competent, unfeminine” (Jamieson, 1995, p. 16).

Misogyny is a characteristic of social systems in which women face hostilities because they are women in a man's world and fail to live up to specific gendered standards (Manne, 2018, p. 34). Misogyny tends to be personal (i.e., targeting very specific women) but it is in its essence political, because it can be seen as an attempt to send a broader message that women as a group should have no part in the political process or should at least act in accordance with their expected gender roles (Krook, 2017, p. 75). Backlash against women in politics and specific cases of misogyny in the political arena can, therefore, be associated with attempts to increase women's empowerment.

The gender and politics literature has focused especially on the ways the gendered double bind and misogynistic backlash affect voter's perception of women politicians and the prospects of women's election. Scholarship on women executives examines factors that may help or hinder women's ability to gain foothold as well. But what happens after a woman president gets elected? How do the double bind and gendered backlash affect a woman's ability to lead? To answer these questions, we focus on political actors' perceptions of the presidency of Brazil's first woman president, Dilma Rousseff. This is an important case study because Rousseff led a strong presidential system for 6 years, was democratically elected and re-elected, and was impeached and ultimately removed from her position. This means that Rousseff was able to transcend the obstacles women traditionally face but was forcibly removed from office, allowing us to analyze her rise and fall through gendered lenses.

Materials and methods

We use a thematic analysis of interviews with political actors in Brazil (for a detailed discussion, see the Appendix). Thematic analysis attempts to “arrive at an understanding of a particular phenomenon from the perspective of those experiencing it” (Vaismoradi et al., 2013, p. 398). It facilitates identifying themes arising in interviews and others forms of data collection, providing a rich context to expand on complex concepts and recognize patterns that can strengthen conceptual and empirical discussions (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Terry et al., 2017).

Thematic analysis captures nuanced concepts. The various steps in coding the data allow researchers to refine their approach and to find patterns and themes not previously identified. Here, we develop a thematic analysis focusing on the gendered double bind and backlash and then systematically follow best practices suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006) and Terry et al. (2017). The interview data we use was originally collected in 2017 and 2018, transcribed (in Portuguese) and translated to English. A group of seven researchers (including all co-authors) worked in different stages of the project to develop a thematic analysis of 90 interviews (see Table 1 and Appendix). The profile of interview subjects (mostly women2) helps us identify themes related to the gendered double bind and backlash since the subjects themselves experience and think about the topic regularly. Using this data, the goal of the process is to develop a conceptualization and qualitative measure/discussion of the gendered double bind and gendered backlash.

Table 1. Thematic analysis—phases and best practices [Adapted from (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Terry et al., 2017)].

Part of the research team (two of the co-authors and one research assistant) spent the summer of 2019 exploring the literature on Dilma Rousseff's presidency and identifying possible themes related to Rousseff's leadership. While other themes stood out (Phase 3 on Table 1), the gendered double bind appears directly and indirectly throughout the interviews, while misogynistic backlash appears most times in connection and relation to the gendered double bind. Phase 4, conducted by three co-authors and one research assistant, involved identifying sentences and paragraphs connecting to a broad conceptualization of the gendered double bind and misogynistic backlash in a random sample of the interview dataset. Data strings broadly defining these concepts were analyzed for nuance inside these data strings. For Phase 5 the researchers (all of the co-authors) developed subcategories (or sub themes) present inside the previously coded data, using a consensus model to identify the subcategories present in all 90 interviews conducted.

The increasing familiarity with the interview data over various phases was vital to the analysis, as thematic analyses require researchers to deeply engage with data (Terry et al., 2017). Researchers first coded interview transcripts for the double bind and then reread quotes selected for the double bind to code for subcategories. The researchers' close work and immersion in the interview transcripts helped highlight the complexity of the gendered double bind and its connection to misogynistic backlash. The transition of focusing on themes initially selected, to the themes explored by three researchers (Phase 3 in Table 1) to finally the focus on subthemes of the gendered double bind (including misogynistic backlash) also highlights the importance of viewing analysis as a flexible and interpretative process as emphasized by thematic analysis (Terry et al., 2017).

From gendered double bind to misogynistic backlash

Once they get a foot in the door, women still face various challenges in their positions. One of these is the gendered double bind. Because men have dominated presidencies, there are certain gendered expectations. The public often associates leadership with traits like aggression, competitiveness, dominance, and rationality. For women, it may be harder to demonstrate these qualities because constituents have specific expectations of men and women. More specifically, they tend to associate men with “masculine” traits and women with “feminine” traits. Male traits typically include the qualities envisioned with political leadership such as aggression, competition, dominance and rationality. Feminine traits typically include being more caring, compassionate, nurturing, and emotional. When women do demonstrate “masculine” traits, it has the potential to undermine their leadership. Burns and Murdie explain, “women are perceived more negatively by the public for exhibiting the same behaviors as men. This means that women acting assertively violate gendered expectations and may be penalized more for this behavior” (Burns and Murdie, 2018, p. 473). Not only are women in positions of leadership viewed negatively for behaving in the same manner as men, but when they do behave the way they are expected to as a woman, they aren't seen as fit to lead. For example, “In her first campaign in 2005, Bachelet was routinely criticized for her more consensual approach to leadership that differed from an authoritative, directive style strongly associated with presidential power. Her opponents claimed that she simply was not “presidential” or lacked competence” (Schwindt-Bayer, 2018, p. 24).

The gendered double bind not only makes it difficult for women leaders to get a spot at the table in the first place, but it also creates challenges during their time in office, as evidenced by our findings. Rousseff had to navigate a political terrain that faulted her for acting too feminine. Yet, if she behaved in a masculine manner, she was labeled as harsh and overbearing. In some instances, the consequence of the double bind was misogynistic backlash targeting President Rousseff, a gendered backlash affecting women because of their gender identity.

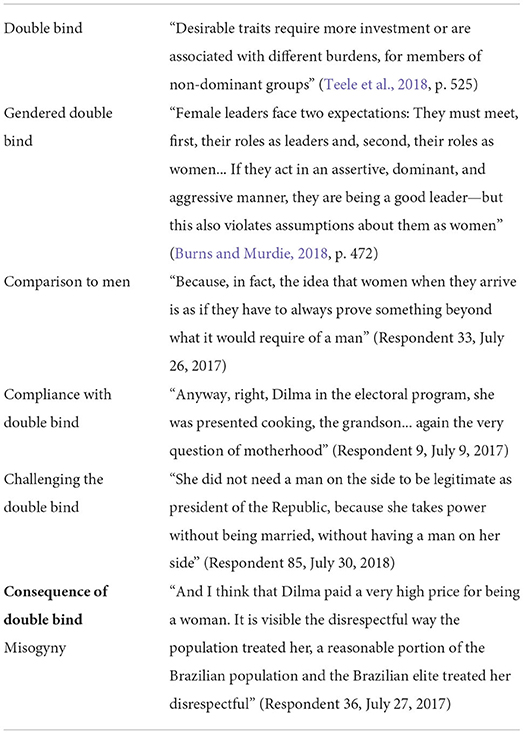

Discussions about Rousseff's impeachment and the sexism and misogyny behind the process have been discussed in popular media (Hao, 2016; Hertzman, 2016; Romero and Kaiser, 2016) and in scholarly works (Zdebskyi et al., 2015; Cardoso and Souza, 2016; Santiago and Saliba, 2016; dos Santos and Jalalzai, 2021). In this work we will focus on misogyny as identified by our interviewees in the context of Rousseff's 6 years in power, specifically emphasizing the connection between misogynistic backlash and the gendered double bind dynamics identified. The themes identified in our analysis will serve as the driving points for the remainder of this paper. In the following section we provide a more nuanced definition for each of the subcategories identified (see Table 2), providing stand-alone definitions and examples from the data combined with descriptive analyses of key moments in Rousseff's presidency that exemplify the dynamic between our nuanced proposal for analyzing the gendered double bind, misogynist backlash, and its consequence on Rousseff's presidency.

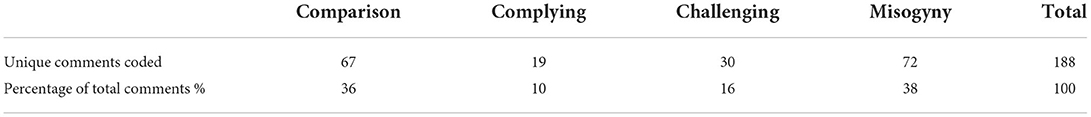

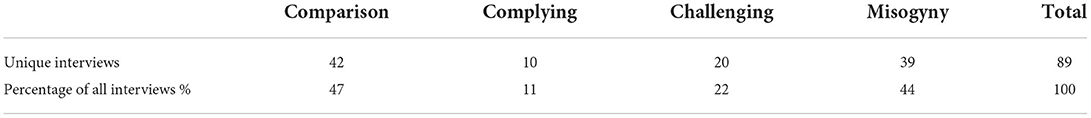

The four subcategories identified appeared in the data at varying levels (see Tables 3, 4). Two themes appeared in higher proportion: Comparison to Men and Misogyny. Comments themed as comparison to men appeared in almost half of all interviews and represented 36 percent of all comments codified. Comments themed as misogyny were the majority comments (38 percent) and appeared in 44 percent of all interviews. In other words, interviewees were most cognizant of Rousseff's role as president in comparison to other male politicians and former presidents, as well as the ways Rousseff was punished during her administration because of gendered expectation and backlash.

While appearing with less frequency in the interviews, the other two themes provide important context to understanding possible sexist backlash during the presidency of Brazil's first woman president. Discussions on how Rousseff attempted to comply with gendered expectations ascribed to women (Complying with the Double Bind) appeared in over 10 percent of the comment coded and interviews conducted. Meanwhile, discussion on how Rousseff challenged the gendered expectations of her position (Challenging the Double Bind) appeared in over one fifth of all interviews, constituting 16 percent of all comments coded.

The description of the numerical occurrence of the thematic analysis provides a starting point to a qualitative analysis of each theme, focusing on the connection between each theme, especially the connection between the three themes directly related to the gendered double bind (comparison, complying, and challenging) and the misogynistic backlash that followed.

Comparison to men

One of the subcategories identified was comparisons of Dilma Rousseff to men, both comparing Rousseff to male political figures and describing how things would be different if Rousseff were a man. Thus, we found that there is both an abstract component and practical component to her comparison to men. In an abstract sense, we often saw the phrase, “if she were a man” to describe how a situation would have played out differently had Dilma not been a woman. The narrative portrayed in our interviews is of a system that “favors men” (Respondent 88, July 31, 2018), with “no open gender discrimination, but the fact that [a politician] is a man is a plus” (Respondent 8, July 5, 2017). When discussing this comparison more concretely, there is a focus on Rousseff's abrasive personality, the “tough woman around tender men.” The quote below provides more context:

Yes, and they said that she was a hard person, that she could not talk to anyone, that she had an authoritarian way of speaking. Everything that for men appears as a compliment “no, he is a hard person, a self-confident person who knows what he wants.” To her was presented as negative “no, she does not know how to talk, she is hard, she is this” in a negative way. How they talk to us, women. We have reached a certain position, we are being harsh, we are deviating from to how to be a woman, who is sweet, transparent, quiet and such. The form of Dilma being is the form of women who manage to be strong within a completely patriarchal world, facing this order that exists (Respondent 79, July 25, 2018).

Various interviewees also directly compared Rousseff to male political leaders. Some comparisons questioned the unfair treatment Rousseff received, especially in comparison to Michel Temer, the man who succeeded her in power. More interestingly, with Lula as her same party predecessor, comparisons between Rousseff and Lula were common and gendered in distinct ways. One interviewee says, “Lula was also charismatic, and she is not, and it was never required of her to fulfill this role, to be charismatic” (Respondent 3, June 30, 2017). Others state that “Lula was a political animal, he could have a Dilma in the center, more technical. Dilma was not this political animal, she had to have that political animal underneath and she did not have it” (Respondent 22, July 18, 2017). So, while comparisons between Rousseff and her successor (who was vilified by Rousseff supporters throughout) emphasized the double standard women face, comparisons between Rousseff and her predecessor subtly questioned Rousseff's political abilities, indicating that the gendered double bind affected even how her supporters viewed her leadership skills.

Complying with the double bind

Another theme that arose was how Rousseff complied with the double bind during her campaign and presidency. To gain popularity or appear more likable, Rousseff adopted a “Mother of Brazil” persona in the media (dos Santos and Jalalzai, 2014). During the campaign, the birth of her grandson allowed Rousseff's campaign to emphasize her motherly (and grandmotherly) role (mentioned in five interviews a total of thirteen times). But Rousseff also emphasized motherhood and gendered traits throughout her presidency. For example, in Mother's Day speeches, Rousseff emphasized the role of motherhood and motherly traits as essential to the development of the country (dos Santos and Jalalzai, 2014). Another interesting political moment was shared by an interviewee:

“I think sometimes she used the female condition in a positive way. When there was that Brazilian who was between life and death in Indonesia for drug trafficking, the guy was going to be executed and there was an appeal and she contacted the president of Indonesia and spoke: ‘I appeal as president of the republic and as mother.' She tried to make a humanitarian appeal, but also of a woman, has a greater weight so. And at the same time, she used this condition of woman, but I think in that context was very appropriate, you try to sensitize a president of the republic as president and as mother has a greater weight” (Respondent 9, July 9, 2017).

While this was the least common category of analysis (see Tables 3, 4), complying with the double bind once again provides evidence of the impossible task for women executive leaders. Women must appeal to feminine traits and other gendered identities such as mother and grandmother but must do so in the context of a political role that requires leadership traits that undermine the importance of feminine traits and identities. In complying with the double bind, Rousseff, and arguably other women leaders, must navigate a difficult political landscape, emphasizing gendered roles when deemed (or calculated as) appropriate without letting go of masculine leadership traits. In other words, they must comply with gendered expectations even though their political role and their presence in this role fundamentally challenges the status quo.

Challenging the double bind

Although, at times, Rousseff chose to exhibit traditional feminine traits to avoid criticism, our analysis suggests she often went against these norms. The researchers identified passages where interviewees talked about Rousseff acting in ways that differed from traditional gendered (feminine) norms. These statements emphasize instances where Rousseff exhibited stereotypical masculine traits and/or did not follow traditional feminine expectations. Several interviewees emphasized Rousseff's career trajectory and personal life as transgressions to established gendered norms. For example, on the day of her inauguration, “She paraded in an open car with her daughter, without a man on his side, without a male figure. And an adult daughter, so it was not a child, it was a woman, a professional, an adult daughter that did not depend on her” (Respondent 34, July 26, 2017). Rousseff's decision to participate in the parade broke away from a traditional family structure, instead showing her independence as a divorced mother, as a woman who does not need the help of a man. “It was not an image reinforcing the image of mother, it was reinforcing the image of woman, but I do not know how that was seen in the world” (Respondent 34, July 26, 2017).

Some interviewees explained how Rousseff's personality and style transgressed expected feminine traits and prevented her from connecting with other female political figures and women in general. One interviewee expressed this opinion: “women complained, for example, is that women could not talk to Dilma about her being a woman” (Respondent 21, July 17, 2017). Another interviewee expanded: “People didn't see Dilma as a woman because the way she presented herself, or in a meeting. She was a person who swears a lot (…). If she was in a meeting with other people, not just subordinates, anyone, she was swearing, you see all the time” (Respondent 87, July 31, 2018). Here the interviewee suggests Rousseff's swearing was more masculine, and that it was her choice to not appear as a woman. Although some of the interviews simply highlighted how Rousseff was “strong,” “firm,” or “hard,” others seemed to criticize her inability to express female and maternal characteristics, such as being “caring” or “sensitive.” Respondent 87 continued, “I am not blaming her for doing that, but by doing that I think she was not seen as a woman, like these caring or sensitive women, that was looking for children, as they would expect a woman would be. She was seen as this strong, actually even as not a polite person” (July 31, 2018).

Rousseff received criticism for choosing not to fulfill traditional feminine roles. Although these behaviors are acceptable for men, even the women we interviewed (including women who supported Rousseff) sometimes struggled with the interpretation of these transgressions: some saw Rousseff's transgressions as a negative aspect of her leadership style. “She was a woman alone, she was a woman without a man, without a husband. This was quietly used against her. When she was tough in the meetings, it was common to say: now she has PMS” (Respondent 63, July 19, 2018). The connection between her arguably masculine leadership style to an age-old sexist trope regarding women's mental state and their menstrual cycle exemplify the kind of backlash that women can receive when transgressing/not complying with expected gendered traits.

Backlash: Misogyny as a consequence

Our thematic analysis emphasized three ways in which the gendered double bind influenced Rousseff's presidency: comparisons to men, compliance with gendered expectations, and challenging gendered expectations. We identified another themed related to the gendered double bind: the misogynistic backlash Rousseff endured during her presidency. The researchers coded for misogyny when passages discussed hatred for women and specific prejudice against Rousseff related to the fact that she is a woman. These references emphasize Rousseff being treated differently than her male counterparts, specifically in relation to being treated with disrespect, ridicule, and being dismissed because she is a woman. As one interviewee stated, “the fact that she was a woman was used against her” (Respondent 88, July 31, 2018).

We identified the misogyny theme, keeping in mind the conceptual and empirical debates surrounding the term today. We conceptualize misogyny as a “system that punishes, dominates, and condemns those women who are perceived as an enemy or threat to the patriarchy” (Manne, 2018, p. 34). The ways the system punishes, dominates, and condemns women varies, but the intent is to put women in their place. In the context of women in executive positions, the masculine and masculinist mature of presidencies across history implies a system that is overtly and covertly patriarchal, meaning that any attempt to transgress pre-established expectations based on gender identity is likely to be perceived as a threat to the “way the system works.” Hence, in systems dominated by men such as executive politics, misogyny will work in overt and covert ways (see also Krook, 2020).

Our thematic analysis identified a connection between misogyny and two of the gendered double bind categories: comparison to men and challenging the double bind. In other words, when interviewees discussed these two aspects of the gendered double bind, most also identified a connection between them and misogynist responses toward President Rousseff.

In the two types of comparisons to men, the abstract and the practical, misogynistic outcomes followed different logics. When comparing Rousseff to men (“if she were a man”) interviewees are alluding to the subtle misogynistic nature of politics, often emphasizing that Rousseff would be “punished” for actions and behaviors that would not warrant the same reactions if she was a man. When directly comparing Rousseff to other men, especially Lula, interviewees were often engaging in gendered rhetoric that ascribed to Lula (and other men) a kind of leadership that is seen as masculine and more competent/capable, while downplaying Rousseff's own leadership abilities. It is interesting to note that some of our subjects criticized the comparison to men in the abstract but would then participate in this gendered rhetoric ascribing to Lula (and other men) leadership traits that emphasize their ability to lead over Rousseff's own ability. For example, an interviewee stated: “Lula was a political animal (…) Dilma was not this political animal” Respondent 22, July 17, 2017). In other words, when comparing Rousseff to men and ascribing to these men “better” leadership qualities, subjects are at a minimum ascribing to subtly sexist narratives.

When addressing Rousseff's challenges to the gendered double bind, connections between them and misogyny were easily identified by our interviewees. This is especially present when connecting Rousseff's abrasive leadership style to the impeachment process. Rousseff's demanding leadership style established a clear transgression by the president toward the patriarchal structure: she dared to interrupt men, to yell at men, and to make decisions that went counter to what some of her allies and opposition believed were best for the country. As one interviewee put it, “men do not like being led by women. They can be led by a scumbag like Michel Temer, Aécio. But a woman may even be correct, but she will always be diminished” (Respondent 6, July 4, 2017). Rousseff's disregard toward the patriarchal structureled her to lose some support inside her own party and galvanized the opposition to pursue an impeachment process that had clear misogynistic elements into it, such as the Tchau, Querida (Goodbye, Dear) chants and constant questions about Rousseff's intelligence and appearance (dos Santos and Jalalzai, 2021).

In sum, our thematic analysis showed that the gendered double bind manifests itself in different ways, and that the consequences of such manifestations also differ. When Rousseff attempted to comply with the gendered double bind, our interviewees sometimes criticized her for doing so or argued that such compliance is part of the political process, but rarely connected such actions with an attempt to put Rousseff in her place. Conversely, discussions surrounding comparisons of Rousseff to men and examples of Rousseff rejecting or challenging the gendered double bind tended to link these actions with misogynistic responses to Rousseff's leadership.

Discussion

This article examined how the gendered double bind manifested itself in Dilma Rousseff's presidency. As the first woman president of Brazil, Rousseff's time in office provided an appropriate case study. Using a thematic analysis of interviews with political actors in Brazil, we discovered that the double bind resulted in Rousseff's comparison to men, Rousseff complying with the double bind to gain political support and Rousseff challenging the double bind. Throughout it all, Rousseff experienced misogyny as Brazil's first woman president. This dynamic suggests that the gendered double bind is rooted in misogyny. While Rousseff may not have faced outright gender hostility in all aspects of her presidency, she had to navigate the political landscape in a way that men simply do not. She had to walk the fine line of being not too caring but not too firm, not too passive but not too decisive, not too quiet but not too loud. Like countless other female leaders, Dilma Rousseff had to work against the barrier that is the gendered double bind.

Although Rousseff overcame many barriers to become president in the male-dominated sector of politics, our findings suggest she continued to face challenges while in office. In fact, the gendered double bind likely influenced Rousseff's presidency in several ways. The subcategories of the gendered double bind illustrate the complexity to this phenomenon. The findings show how Rousseff faced many challenges because of her gender, as she both challenged assumptions of leadership, fulfilled typical female roles, and was continually compared to men. Furthermore, her competence as a political leader was repeatedly questioned while in office.

Due to this negative treatment from being a woman, another way Rousseff reacted to the criticism was by adhering to traditional feminine and maternal traits. In other instances the interviewees discussed show how she also chose to break away from female norms by displaying strength and independence from men. Rousseff's ability to both go against gender expectations, while also at times adhering to typical female traits, implies she recognized how her leadership was being negatively affected by the gendered double bind. It also implies that women must be flexible and respond in many ways to criticism to be successful. Rousseff's ultimate impeachment, however, may indicate that it is ultimately very difficult to overcome these criticisms.

Backlash against Rousseff that led to her impeachment ushered in an era of major policy setbacks for women. Programs that especially benefitted poor women that Rousseff expanded during her tenure were completely eradicated, unenforced or underfunded (dos Santos and Jalalzai, 2021). Levels of women in the cabinet had reached historical highs under Rousseff. When Michel Temer took over as president, he failed to appoint a single woman to the cabinet (Garcia-Navarro and Geo, 2016). His successor, Jair Bolsonaro's misogynistic rhetoric may have contributed to rising rates of violence against women (Lavinas and Correa, 2020). Backlash against an individual woman in power can lead to far-reaching negative impacts on women more broadly.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by PS, Luther College. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

FJ conducted some of the interviews and helped write text. PS conducted some of the interviews, helped write text, and helped code. BK, LM-P, and BS explored the literature on Dilma Rousseff's presidency and identified possible themes related to Rousseff's leadership and from the transcripts, identified sentences, and paragraphs to develop strings broadly defining these concepts and developed subcategories (or sub themes) present inside the previously coded data, using a consensus model to identify the subcategories present in all 90 interviews conducted. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank research assistants Noemi Salas-Rivera and Belen Dominguez for their support in developing this work as well as the reviewers who helped strengthen the article. A version of this article was presented at the 2021 American Political Science Association Annual Meeting.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.926579/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The expression used by Rousseff in Portuguese was homens meigos. There are different ways to translate the word meigo to English, including tender and gentle. There is a gendered component in this expression, where men showing tenderness/gentleness may be seen as less masculine.

2. ^It is important to note that while most of our interviewees were women, not all fully supported president Rousseff. Interviews were conducted with journalists and academics who were critical of her government, and with politicians from the opposition. Moreover, as discussed in dos Santos and Jalalzai (2021) many of the women interviewed experienced a complex relationship with Rousseff and her administration: activists and political actors directly involved in the policymaking process were very critical of many of Rousseff's policies while emphasizing the role of misogyny and gendered backlash throughout her presidency and especially during the impeachment process.

References

Acker, J. (2012). Gendered organizations and intersectionality: problems and possibilities. Equal Div. Incl. Int. J. 31, 214–224. doi: 10.1108/02610151211209072

Adams, M. (2017). “Assessing Ellen Johnson Sirleaf's Presidency: Effects on Substantive Representation in Liberia,” in Women Presidents and Prime Ministers in Post-Transition Democracies Palgrave Studies in Political Leadership, ed V. Montecinos (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK), 183–204. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-48240-2_9

Anderson, K. V. (2017). Presidential pioneer or campaign queen? Hillary clinton and the first-timer/frontrunner double bind. Rhetor. Public Aff. 20, 525–538. doi: 10.14321/rhetpublaffa.20.3.0525

Baturo, A., and Gray, J. (2018). When do family ties matter? The duration of female suffrage and women's path to high political office. Polit. Res. Q. 71, 695–709. doi: 10.1177/1065912918759438

Baumann, H. (2017). Stories of women at the top: narratives and counternarratives of women's (non-)representation in executive leadership. Palgrave Commun. 3, 1–13. doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.9

Bierema, L. L. (2016). Women's leadership: troubling notions of the “ideal” (male) leader. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resourc. 18, 119–136. doi: 10.1177/1523422316641398

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brooks, D. J. (2011). Testing the double standard for candidate emotionality: voter reactions to the tears and anger of male and female politicians. J. Polit. 73, 597–615. doi: 10.1017/S0022381611000053

Burns, C., and Murdie, A. (2018). Female chief executives and state human rights practices: Self-fulfilling the political double bind. J. Hum. Rights 17, 470–484. doi: 10.1080/14754835.2018.1460582

Cardoso, Y. R. G., and Souza, R. B. R. (2016). Dilma, uma “presidente fora de si”: o impeachment como um processo patriarcal, sexista e midiático. Pauta Geral Estudos J. 3, 45–65. doi: 10.5212/RevistaPautaGeral.v.3.i2.0003

Carlin, R. E., Carreras, M., and Love, G. J. (2019). Presidents' sex and popularity: baselines, dynamics and policy performance. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 50, 1–21. doi: 10.1017/S0007123418000364

Cortès-Conde, F., and Boxer, D. (2015). “Breaking the glass & keeping the ceiling: women presidents' discursive practices in Latin America,” in Discourse, Politics and Women as Global Leaders, eds J. Wilson and D. Boxer (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing), 43–66. doi: 10.1075/dapsac.63.03cor

Dantas, F. A. (2019). Dilma Rousseff, Uma Mulher Fora do Lugar: As Narrativas Da Mídia Sobre a Primeira Presidenta Do Brasil. (Doctoral Dissertation), Salvador: Federal University of Bahia (Brazil).

de Bolle, M. B. (2016). Como Matar a Borboleta-azul: Uma Crônica da Era Dilma. Rio de Janeiro: Intrínsica.

de Gois, C. (2009). “Sou uma mulher dura cercada de homens meigos”, diz Dilma Rousseff. Extra. Available online at: https://extra.globo.com/noticias/brasil/sou-uma-mulher-dura-cercada-de-homens-meigos-diz-dilma-rousseff-248585.html (accessed January 13, 2021).

dos Santos, P. A. G., and Jalalzai, F. (2021). Women's Empowerment and Disempowerment in Brazil: The Rise and Fall of President Dilma Rousseff. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

dos Santos, P. G., and Jalalzai, F. (2014). “The mother of brazil: gender roles, campaign strategy, and the election of Brazil's first female president,” in Women in Politics and Media: Perspectives from Nations in Transition, eds M. Raicheva-Stover, and E. Ibroscheva (New York, NY: Bloomsbury).

Eagly, A. H., and Carli, L. L. (2007). Through the Labyrinth: The Truth About How Women Become Leaders. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Eagly, A. H., and Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 109, 573–598. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

Ellis, S. (2018). The Biggest Corruption Scandal in Latin America's History. Vox. Available online at: https://www.vox.com/videos/2018/10/30/18040200/brazil-car-wash-corruption-scandal-latin-america (accessed June 15, 2019).

Ernst, J. (2021). Xiomara Castro Poised to Become First Female President of Honduras. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/nov/29/xiomara-castro-declares-victory-in-honduras-presidential-election (accessed February 15, 2022).

Garcia-Navarro, L., and Geo, V. (2016). Brazil's New Cabinet Has no Women, Drawing Social Media Backlash, National Public Radio. Available online at: https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2016/05/12/477528379/brazils-new-cabinet-has-no-women-drawing-social-media-backlash (accessed April 21, 2022).

Genovese, M. A., and Steckenrider, J. S (eds.). (2013). Women as Political Leaders: Studies in Gender and Governing. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hao, A. (2016). In Brazil, Women Are Fighting Against the Sexist Impeachment of Dilma Rousseff. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/jul/05/in-brazil-women-are-fighting-against-the-sexist-impeachment-of-dilma-rousseff (accessed October 13, 2016).

Hargrave, L., and Blumenau, J. (2022). No longer conforming to stereotypes? Gender, political style and parliamentary debate in the UK. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 1–18. doi: 10.1017/S0007123421000648

Harp, D., Loke, J., and Bachmann, I. (2016). Hillary clinton's benghazi hearing coverage: political competence, authenticity, and the persistence of the double bind. Womens Stud. Commun. 39, 193–210. doi: 10.1080/07491409.2016.1171267

Hertzman, M. (2016). The Campaign to Impeach Brazil's President Is Viciously Sexist. The Cut. Available online at: https://www.thecut.com/2016/04/brazil-sexist-impeachment-campaign-dilma-rousseff.html (accessed May 21, 2019).

Hunter, W., and Power, T. J. (2019). Bolsonaro and Brazil's illiberal backlash. J. Democ. 30, 68–82. doi: 10.1353/jod.2019.0005

Jalalzai, F. (2010). Madam president: gender, power, and the comparative presidency. J. Women Polit. Policy 31, 132–165. doi: 10.1080/15544771003697643

Jalalzai, F. (2013). Shattered, Cracked, or Firmly Intact?: Women and the Executive Glass Ceiling Worldwide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Jalalzai, F. (2015). Women Presidents of Latin America: Beyond Family Ties? New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315769073

Jalalzai, F. (2019). “Women leaders in national politics,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies, ed N. Sandal (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.506

Jamieson, K. H. (1995). Beyond the Double Bind: Women and Leadership, First Printing edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jensen, J. (2008). Women Political Leaders: Breaking the Highest Glass Ceiling, 2008 Edn. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Karl, K. L., and Cormack, L. (2021). Big boys don't cry: evaluations of politicians across issue, gender, and emotion. Polit. Behav. 24, 1–22. doi: 10.1007/s11109-021-09727-5

Koenig, A. M., Eagly, A. H., Mitchell, A. A., and Ristikari, T. (2011). Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychol. Bull. 137, 616. doi: 10.1037/a0023557

Krook, M. L. (2017). Violence against women in politics. J. Democ. 28, 74–88. doi: 10.1353/jod.2017.0007

Krook, M. L. (2020). Violence Against Women in Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190088460.001.0001

Lavinas, L., and Correa, S. (2020). How Bolsonaro's Behavior Runs Counter to Fighting Gender Violence. Open Democracy. Available online at https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/democraciaabierta/jair-bolsonaro-gender-violence/ (accessed April 21, 2022).

Lee, Y.-I. (2017). From first daughter to first lady to first woman president: park Geun-Hye's path to the South Korean presidency. Fem. Media Stud. 17, 377–391. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2016.1213307

Montecinos, V (ed.). (2017). Women Presidents and Prime Ministers in Post-Transition Democracies. Palgrave Macmillan. Available online at: https://www.palgrave.com/us/book/9781137482396 (accessed May 1, 2019).

Ragins, B. R., Townsend, B., and Mattis, M. (1998). Gender gap in the executive suite: CEOs and female executives report on breaking the glass ceiling. Acad. Manage. Perspect. 12, 28–42. doi: 10.5465/ame.1998.254976

Reyes-Housholder, C. (2016). Presidentas rise: consequences for women in cabinets? Latin Am. Polit. Soc. 58, 3–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-2456.2016.00316.x

Reyes-Housholder, C. (2019). A theory of gender's role on presidential approval ratings in corrupt times. Polit. Res. Q. 73, 1065912919838626. doi: 10.1177/1065912919838626

Reyes-Housholder, C. (2021). Gender inequalities and presidential politics: (im)possible to transform? APSA-CP Newslett. 31, 84–92. Available online at: https://www.comparativepoliticsnewsletter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/2021_spring.pdf

Reyes-Housholder, C., and Schwindt-Bayer, L. A. (2016). “The impact of presidentas on political activity,” in The Gendered Executive: A Comparative Analysis of Presidents, Prime Ministers, and Chief Executives, eds J. M. Martin, and M. A. Borrelli (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press), 103–122. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvrdf3zm.10

Reyes-Housholder, C., and Thomas, G. (2018). “Latin America's presidentas: overcoming challenges, forging new pathways,” in Gender and representation in Latin America, ed L. Schwindt-Bayer (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 19–38.

Romero, S., and Kaiser, A. J. (2016). Some See Anti-Women Backlash in Ouster of Brazil's President. The New York Times. Available online at: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/08/world/americas/some-see-anti-women-backlash-in-ouster-of-brazils-president.html (accessed October 13, 2016).

Rosette, A. S., Mueller, J. S., and Lebel, R. D. (2015). Are male leaders penalized for seeking help? the influence of gender and asking behaviors on competence perceptions. Leadersh. Q. 26, 749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.02.001

Rudman, L. A. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: the costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 629. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.629

Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan, J. E., and Nauts, S. (2012). Status incongruity and backlash effects: defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48, 165–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.10.008

Santiago, B. R., and Saliba, M. G. (2016). Bailarinas não fazem política? análise da violência de gênero presente no processo de impeachment de dilma rousseff. Rev. Dir. Fund. Demo. 21, 91–105. Available online at: https://revistaeletronicardfd.unibrasil.com.br/index.php/rdfd/article/view/916

Schwindt-Bayer, L. (2018). Gender and Representation in Latin America. Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190851224.001.0001

Schwindt-Bayer, L. A. (2010). Political Power and Women's Representation in Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Skard, T. (2014). Women of Power: Half a Century of Female Presidents and Prime Ministers Worldwide. Bristol: Policy Press. doi: 10.46692/9781447315797

Teele, D. L., Kalla, J., and Rosenbluth, F. (2018). The ties that double bind: social roles and women's underrepresentation in politics. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 112, 525–541. doi: 10.1017/S0003055418000217

Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2017). “Thematic analysis,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, ed C. Willig, (Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd), 17–36. doi: 10.4135/9781526405555.n2

Thames, F. C., and Williams, M. S. (2013). Contagious Representation: Women's Political Representation in Democracies around the World. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Towns, A. (2019). “Global patterns and debates in the granting of women's suffrage,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Women's Political Rights Gender and Politics, eds S. Franceschet, M. L. Krook, and N. Tan (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK), 3–19. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-59074-9_1

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., and Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study: qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 15, 398–405. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12048

Valdini, M. E. (2019). The Inclusion Calculation: Why Men Appropriate Women's Representation. Oxford University Press. Available online at: https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780190936198.001.0001/oso-9780190936198 (accessed June 22, 2021).

Watts, J. (2017). Operation Car Wash: The Biggest Corruption Scandal Ever? The Guardian. Available online at: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jun/01/brazil-operation-car-wash-is-this-the-biggest-corruption-scandal-in-history (acessed September 9, 2017).

Waylen, G. (2016). Gender, Institutions, and Change in Bachelet's Chile. Palgrave Macmillan. Available online at: http://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9781137501974 (accessed February 6, 2017).

Wiltse, E. Ç., and Hager, L. (2021). Women's Paths to Power: Female Presidents and Prime Ministers, 1960-2020. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Incorporated.

Keywords: Dilma Rousseff, gender, president, Brazil, misogyny, backlash

Citation: Jalalzai F, Kreft B, Martinez-Port L, dos Santos PAG and Smith BM (2022) A tough woman around tender men: Dilma Rousseff, gendered double bind, and misogynistic backlash. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:926579. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.926579

Received: 22 April 2022; Accepted: 17 August 2022;

Published: 07 September 2022.

Edited by:

Susan Banducci, University of Exeter, United KingdomReviewed by:

Marcos Paulo Da Silva, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, BrazilElisabeth Gidengil, McGill University, Canada

Copyright © 2022 Jalalzai, Kreft, Martinez-Port, dos Santos and Smith. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Farida Jalalzai, ZmphbGFsemFpQHZ0LmVkdQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Farida Jalalzai

Farida Jalalzai Brianna Kreft2†

Brianna Kreft2† Pedro A. G. dos Santos

Pedro A. G. dos Santos