- 1Department of Communication and Internet Studies, Cyprus University of Technology, Limassol, Cyprus

- 2Department of Communications & Marketing, Cyprus University of Technology, Limassol, Cyprus

On June 27, 2015, the Greek coalition government, led by the left-wing SYRIZA party, announced the July 5th referendum, asking citizens to decide on the adoption of the EU-proposed economic plan. Referendums in Greece are infrequent, and this decision sparked various interpretations of the motives behind it. In events like the 2016 US presidential elections and the Brexit referendum of the same year, public opinion, especially as expressed on platforms like Twitter, often diverged from the narrative set by the news media agenda. The outcome of the Greek referendum reflected Twitter users’ preferences more closely, surprising many and challenging the traditional role of news media in shaping public opinion. This paper revisits the 2015 Greek referendum, comparing topics discussed in news media with those on Twitter to understand whether the disparity between the two platforms resulted from the dominance of news media agenda-setting or other factors, such as Twitter’s inclination toward alternative voices. The study employs content analysis and topic modeling on a dataset comprising news articles and tweets. Results indicate that the news media agenda predominantly influenced topics discussed by “YES” supporters on Twitter, while it played a less significant role in shaping the topics discussed by “NO” supporters during the 2015 Greek referendum.

1 Introduction

Greece’s extended socioeconomic turmoil, which began with the 2009 financial crisis, has brought about profound political and social transformations in the country. Since the economic crisis started, Greece had received two bailout packages on the condition of drastic austerity measures and structural reforms. In this context, left-wing SYRIZA became the ruling party in January 2015 with an explicit mandate to end austerity. The new government adopted an assertive negotiation strategy, seeking to ease the conditions of the existing bailout program in Greece’s favor. Despite these efforts, creditors remained steadfast in their refusal to make concessions. On 24 June 2015, the European Commission made a “take-it-or-leave-it” proposal about the conditions attached to a bailout extension for Greece (Walter, 2021). Prime Minister Tsipras rejected this proposal. Subsequently, on June 27, 2015, Tsipras called for a referendum with a question regarding the approval or rejection of the plan agreement submitted by the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund in the Eurogroup on June 25, 2015. The prime minister and his coalition recommended that voters should vote “No” and reject the creditors’ proposal. Grexit was a wholly plausible scenario and for many citizens, it represented the ‘question’ they voted on Walter (2021). Political events such as the United States presidential election of 2016 and Trump’s win, and the British referendum on leaving the European Union are examples of events that have astonished academics. In the present article, we focus on a similar case that is part of the same narrative, the Greek referendum of 2015. The bailout referendum held on July 5, 2015, marked the ninth in Greece’s history and stands out as an intriguing case with potential far-reaching implications internationally. Eurozone politicians closely monitored the Greek referendum, and their involvement during the campaign was substantial. The referendum resulted in a resounding “No” vote, with 61.3 percent, while the “Yes” vote garnered 38.7 percent, with a turnout of 62.5 percent. Set against the background of one of the deepest and most prolonged economic crises, the Greek referendum marked the culmination of prolonged and unyielding negotiations between the Greek government and its creditors. Notably, the Greek referendum, with the shortest campaign in the history of referendums, triggered a polarizing debate regarding the reasons upon which it was called as well as its consequence. The heightened influence of media during such a condensed period underscores the significance of studying this referendum as a distinct example of the media’s role in shaping public opinion in high-stakes political contexts. Scholarly research on the Greek referendum remains limited, though a few notable exceptions exist (Boukala and Dimitrakopoulou, 2016; Hansen et al., 2017; Walter et al., 2018; Sools et al., 2018; Katsambekis and Souvlis, 2018; Xezonakis and Hartmann, 2020). These contributions provide important insights, but the field is still underexplored, emphasizing the need for further investigation.

Social media platforms have become integral to political discourse and election campaigns. Regarding the positive effect of the use of Twitter1 in politics and elections, we identify two major impacts. Firstly, Twitter allows political candidates to quickly share information and announcements with a broad audience (Conway et al., 2015). For example, during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Donald Trump effectively utilized Twitter to communicate his campaign messages directly to his supporters, bypassing traditional news media channels. Secondly, Twitter enables politicians to engage directly with voters, creating a sense of accessibility and promoting democratic engagement (Vargo and Guo, 2016; Bossetta, 2018). For instance, during the 2020 New Zealand general election, the hashtag #nzpol trended on Twitter, providing a platform for voters to discuss policy issues, engage with candidates, and mobilize support for their preferred parties. Yet, as with every media, Twitter is known to have caused some serious negative effects. One of them is the spread of misinformation. More specifically, Twitter’s fast-paced nature makes it vulnerable to the dissemination of false information and conspiracy theories. It is notable that during the 2016 Brexit referendum, false claims and misleading information spread rapidly on Twitter, influenced public opinion, and potentially had an impact on voter decisions (Gaber and Fisher, 2021). On another note, the platform’s algorithms and user behavior are responsible for the formation of echo chambers, reinforcing pre-existing beliefs and polarizing political discourse. This polarization can deepen divisions and hinder constructive dialogue (Tsai et al., 2020). In addition, Twitter has been exploited by foreign entities seeking to influence election outcomes (Bossetta, 2018).

Twitter’s inception in 2006 precipitated its rapid growth, amassing half a billion users within a decade, with 310 million deemed active and generating over 500 million tweets daily (Twitter official data2). During the Greek referendum in the second quarter of 2015, it boasted 304 million monthly users (Statistica.com, 20183). In 2015, the year of the Greek referendum, approximately 5% of the Greek population were active Twitter users, which amounted to around 500,000 individuals (Eurobarometer 844). In the 2015 Greek referendum, Twitter played a key role as a platform for public discourse, shaping political narratives and mobilizing voters. Twitter functioned as a space for real-time information exchange, providing a means for citizens to express opinions, debate, and influence each other amid a polarized political climate (Theocharis et al., 2014). Twitter’s dual role in both disseminating news from traditional media sources and amplifying the voices of influencers, activists, and regular citizens alike facilitated a decentralized flow of information, which enabled a reduction in reliance on mainstream media narratives (Theocharis et al., 2014).

Based on the premise that for most people media is a basic source of information on politics and the way they define referendum issues (Wettstein, 2011) and based on the statement that in short-term election periods, campaign effects are even greater (Hobolt, 2009), this article aims to explore the agenda and the topics that emerged in the public debate around the 2015 Greek bailout referendum in two different sets of media sources, namely online press and Twitter. Moreover, based on the advent and the important role of social media concerning the Greek referendum case, the second goal is to investigate the Twitter users’ (and not institutional actors such as politicians and journalists) agenda and the topics that emerge from this agenda. The formulation of the main research questions emanates as follows:

RQ1: What is the agenda set in online press and Twitter overall?

RQ2: What are the predominant topics of discussion among “No” and “Yes” supporters and neutral users on Twitter?

To address these goals, we curated a dataset comprising newspaper articles and tweets, subjecting it to thorough investigation using content analysis and topic modeling. Through manual content analysis, we expect to identify that news articles focus more on economic consequences, Greece’s European future, and economic and national stability, presenting these themes as the main topics of the Greek bailout referendum. Given the fragmented nature of social media discourse, automated content analysis is expected to reveal a broader and more varied set of topics on Twitter, encompassing a mix of personal opinions, sentimental reactions, and alternative perspectives that do not necessarily align with the institutional news media agenda. Through this study, we seek to take an integrated theoretical approach to the analysis of different types of media, namely news and social media.

2 Related work

Changing media infrastructure with the advent of social media has played a significant role in the representations of public opinion development (McGregor, 2019). The ascendancy of platforms like Twitter and social media at large is noteworthy in their profound influence on the formation of public opinion, a role traditionally ascribed to news media. The prevailing trend suggests that citizens frequently formulate their perspectives on policies and programs by relying on their perceptions of social reality, shaped by the combined influence of social media and news media, albeit with discernible variations (Grossman, 2022).

Framing studies have elucidated the mechanisms through which citizens construct their understanding of issues based on the emphasized aspects of news coverage. Wettstein (2011) has posited that, in the lead-up to initiatives, citizens tend to adopt the topical focus presented by the media. Previous research posits that the framing of referendum issues in the news can exert a notable influence on voter participation (de Vreese and Semetko, 2002). Schuck and de Vreese (2008) analyzed news framing effects on turnout during the 2005 Dutch EU Constitution referendum campaign. The study revealed that individuals harboring skepticism towards the EU when exposed to positive news framing about the EU Constitution were mobilized to participate and cast votes against it. Another inquiry by Vreese and Semetko (2004) concentrated on the intensity and tone of news coverage in the context of the Danish 2000 referendum. A key finding was the significant impact of public exposure to television on voting preferences. The model proposed by Vreese and Semetko (2004) also highlighted the crucial role of mediated campaign exposure through news media in the concluding weeks of the campaign. Collectively, these studies underscore the multifaceted effects of news media in influencing voter attitudes, behavior, and overall electoral outcomes, particularly in the distinctive context of referendum campaigns.

The historical role of the news media, which includes newspapers, television, and radio, has been crucial in shaping public opinion (Coleman and Wu, 2021). With their extensive reach and authoritative standing, news media platforms wield considerable influence by determining the agenda-deciding which topics and issues receive attention and dictating their framing (Bennett and Pfetsch, 2018). As established purveyors of information, people often turn to these sources for news and analysis, a practice that significantly contributes to the formulation of their opinions. Recent scholarly inquiries into the Brexit referendum have focused on analyzing press coverage, examining the principal narratives and issues presented by each side of the argument (Levy et al., 2016), predicting the voting patterns in the referendum (Amador Diaz Lopez et al., 2017), and scrutinizing the repetitive deployment of frames and their correlation with public concerns about the European Union in the context of the Brexit referendum (Khabaz, 2018). This academic exploration underscores the multifaceted influence and implications of news media in the molding of public opinion within the complex socio-political landscape.

On the other hand, Twitter has emerged as a prominent platform for public discourse and opinion sharing. It enables individuals, including politicians, celebrities, journalists, and ordinary users, to express their opinions, share information, and engage in conversations. The real-time nature of Twitter, coupled with its expansive user base, fosters expeditious dissemination of news, opinions, and perspectives. The utilization of hashtags and the amplification of trending topics on Twitter hold the potential to garner significant attention, thereby exerting influence over public discussions (Kluknavská and Eisele, 2021). An expanding body of scholarly inquiry has leveraged Twitter data to scrutinize the perspectives of both politicians and citizens alike (Tumasjan et al., 2010; Boyd and Crawford, 2012; McKelvey et al., 2014).

Citizens equipped with internet access and digital devices have gained the capacity to actively engage in discussions on social media platforms, ushering in novel avenues for the representation of public opinion. Various studies (Conway et al., 2015; Harder et al., 2017; Vargo and Guo, 2016; Bossetta, 2018; Kim and Lee, 2021) have explored how individuals use social media for political discussions to share their political views. Twitter’s influence on public opinion formation can be attributed to its ability to amplify voices that may not have had a prominent platform in traditional news media (Rogstad, 2016). It allows marginalized groups, citizen journalists, and grassroots movements to share their experiences, highlight social issues, and challenge dominant narratives. A noteworthy example of Twitter’s impact on public opinion is evident in the case of the Black Lives Matter movement, which garnered widespread attention and support through the platform. The hashtag #BlackLivesMatter served as a rallying point for protests against racial injustice and police violence. Twitter played a pivotal role in disseminating critical information, sharing personal narratives, and organizing demonstrations, thereby effecting a significant transformation in public opinion and fostering heightened awareness regarding systemic racism. This illustrative instance underscores the transformative potential of social media, particularly Twitter, in reshaping public discourse and influencing societal perspectives on pressing issues.

Some scholars argue that the use of social media in general, and Twitter in particular, is likely to reinforce already existing political perceptions, enabling active citizens to engage in politics through new activities (Vergeer et al., 2011). Others argue that the use of social media creates a public sphere that abolishes the differences and limitations in public participation, highlighting a particular type of participation, internet activism (Jackson and Valentine, 2014). Based on these findings, citizens in the public sphere(s) of social media are not seen only as passive recipients of campaigning content and news media agenda. Instead, they play an active and participatory role in the dynamic process of online opinion-making.

In addition, a number of studies have found a relationship between exposure to social media and a higher level of electoral participation and turnout (Gueorguieva, 2007; Gulati and Williams, 2010; Lee and Xenos, 2020). Other studies show linkages between social media use and individuals’ political engagement (Holt et al., 2013; Loader et al., 2014; Boulianne, 2015; Gil de Zúñiga and Diehl, 2018; Ahmed et al., 2022). The latter is particularly relevant, since Twitter facilitates the formation of online communities and echo chambers, where like-minded individuals reinforce their opinions and beliefs, which can shape public sentiment (Xiong et al., 2019). The #MeToo movement is characteristic of this trend as it gained momentum on Twitter. Survivors utilized the platform to share their narratives, catalyzing a societal reckoning and instigating a more extensive discourse on power dynamics and gender inequality. Twitter provided an avenue for victims to circumvent news media gatekeepers, enabling the formation of a collective voice that significantly influenced public opinion regarding the frequency and ramifications of sexual misconduct (Prendergast and Quinn, 2020).

In the past, scholars have argued that social media democratizes information and fosters collective action by removing traditional gatekeepers (Shaw, 2012; Coddington and Holton, 2013). However, it is important to note that Twitter’s influence on public opinion is not without challenges. In 2016, after the Cambridge Analytica scandal on Facebook, we changed how we see social media in political campaigning. This potential is increasingly undermined by significant challenges, including disinformation and political polarization. Misinformation spreads rapidly on platforms like Twitter, with Egelhofer and Lecheler (2019) arguing that false information reaches more people than the truth, exacerbating public confusion and distorting democratic debate. The platform’s fast-paced nature and limited character count can promote oversimplification and the spread of misinformation. The prevalence of bots, trolls, and coordinated campaigns can manipulate public discourse, and distort public opinion. Additionally, the demographic and socio-economic biases present in Twitter’s user base can limit the representativeness of the opinions and perspectives shared on the platform. Moreover, echo chambers and algorithmic filters on platforms like Facebook and Twitter reinforce ideological divides by presenting users with content that aligns with their pre-existing beliefs, contributing to polarization (Spohr, 2017). This creates fragmented publics, where opposing viewpoints rarely intersect, limiting the possibility for constructive democratic dialogue (Tian, 2023). These issues, along with the socio-economic and demographic biases inherent in social media user bases (Spohr, 2017), restrict the platforms’ representativeness and challenge their role as inclusive spaces for democratic engagement.

In summary, both news media and Twitter have the potential to influence public opinion formation. News media’s reach and authority can shape public perceptions, while Twitter’s participatory nature and amplification of diverse voices can impact public discourse. However, it is important to critically evaluate the information from both sources, considering their strengths, limitations, and potential biases. And this is exactly where the present study is targeting at. Despite the growing body of research focusing on referendum campaigns, the agenda of different types of media is not the primary concern. Although not the first of its kind, this study is among the few that utilize quantitative data from both social and news media to analyze the relationship between these two sources and the agendas they set (Rogstad, 2016; Harder et al., 2017; Su and Borah, 2019; Gilardi et al., 2021; Su and Xiao, 2024).

3 Data and methods

To address the goals of the present study, which is to explore and compare the topics that were highlighted in news media and Twitter, we used a corpus of data from online news media and tweets. This methodological approach was adopted to facilitate a comprehensive analysis of the information landscape across these two distinct but influential communication sources. The comparative analysis between the online press and Twitter data at two distinct levels provides an insightful examination of agenda-setting dynamics, focusing on emergent topics and tone. Simultaneously, the juxtaposition of these two-level analyses, employing markedly different methodological approaches, affords a comprehensive comparison. Specifically, it contrasts manual content analysis, which elucidates primary topics, with automated computational analysis through topic modeling, illuminating topics stemming from both “YES” and “NO” supporters. The strategic integration of both manual content analysis and automated topic modeling in this study was deliberate, aiming to capitalize on the distinctive strengths inherent in each methodology. Simultaneously, automated topic modeling enhanced the scalability of the analysis, ensuring the efficient processing of voluminous datasets.

3.1 News media data collection

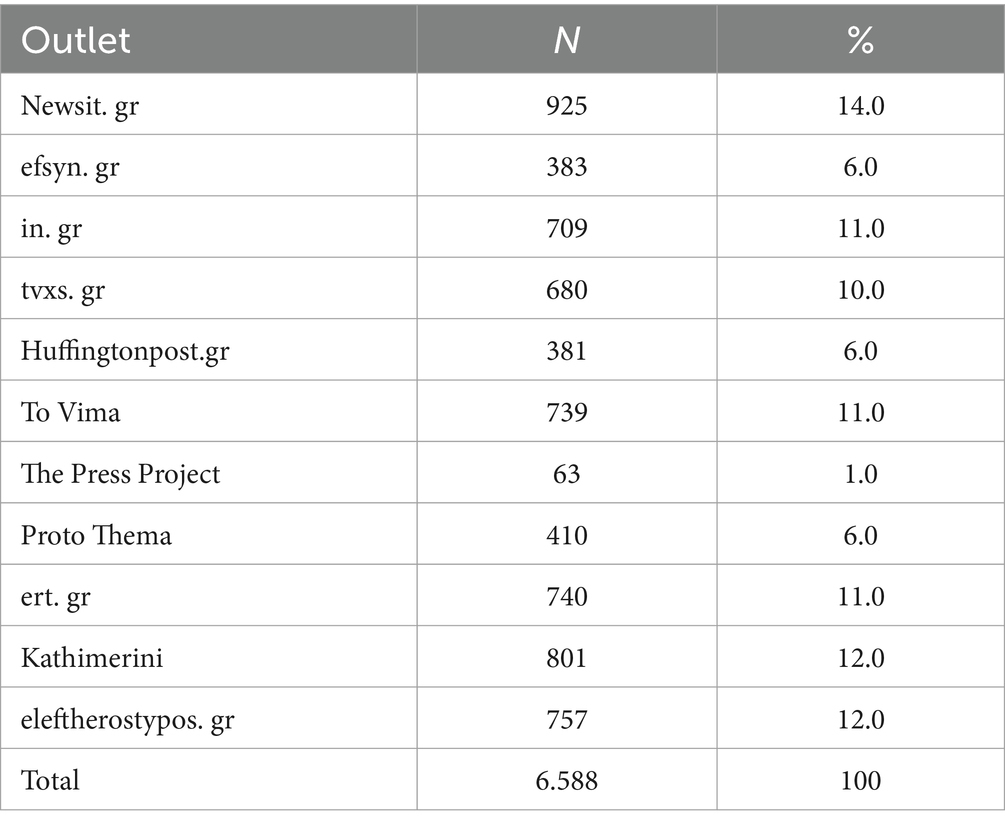

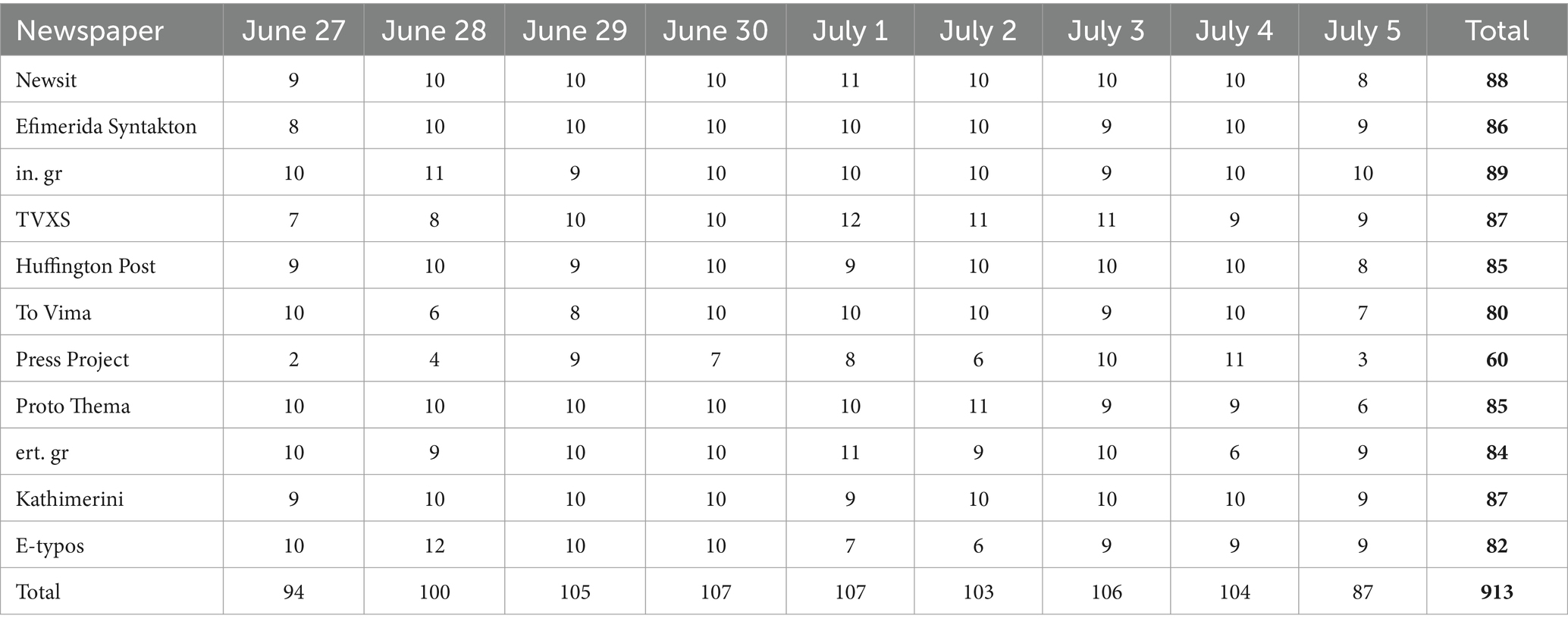

During the 2015 Greek bailout referendum campaign, an extensive data collection process took place which resulted in gathering all newspaper articles that were published online and referred to the referendum directly or indirectly from 11 news outlets (see Table 1). The online press articles were collected from four legacy media organizations: To Vima, Kathimerini, Proto Thema, and Eleftheros Typos; the public broadcaster service, namely ert.gr; three news web portals that do not have a print edition (Huffington Post Greece5, in.gr and Newsit6) and three alternative news sources, TVXS, The Press Project and Efimerida Syntakton. The Press Project and Efimerida Syntakton are self-managed by journalists’ cooperatives and have no affiliation to corporate resources as they run as non-profit organizations (Siapera et al., 2014). The total dataset comprises 6.588 news and opinion articles. As a second step, a representative sample was constructed using random stratified sampling, which included 913 articles (14% of the articles’ population), equally distributed over the 9 days of the campaign (June 27–July 5). The only exception was The Press Project, which published a total of 60 articles in the selected period, a significantly smaller number compared to all other outlets. In this case, all 60 articles were included in the sample (see Table 2).

3.2 Twitter data collection

The second dataset consisted of Twitter posts. A total of 507.263 tweets tagged with the hashtags #Greferendum, #dimopsifisma, #OXI, #NAI and variations of them were mined, using the Twitter Streaming API7, during the period June 27–July 5, 2015. This dataset was then automatically filtered by language and 13.000 tweets in Greek were selected. This subset appeared to be quite unbalanced towards the “NO” vote. Tweets were balanced according to voting position categories (pro-YES, pro-NO, and neutral) to ensure valid thematic extraction through automated analysis. This stratification enabled a nuanced examination of the topics across distinct voter groups, facilitating a comprehensive and credible comparison. Thus, a second subset consisting of 5,088 tweets was extracted and given to annotators for manual classification of tweets. We used the second subset (5.088) to run the topic modeling analysis. Utilizing topic models across the entire spectrum of Twitter users allowed us to examine the emerging themes among “YES” and “NO” supporters and those categorized as neutral.

3.3 Analysis of news media data

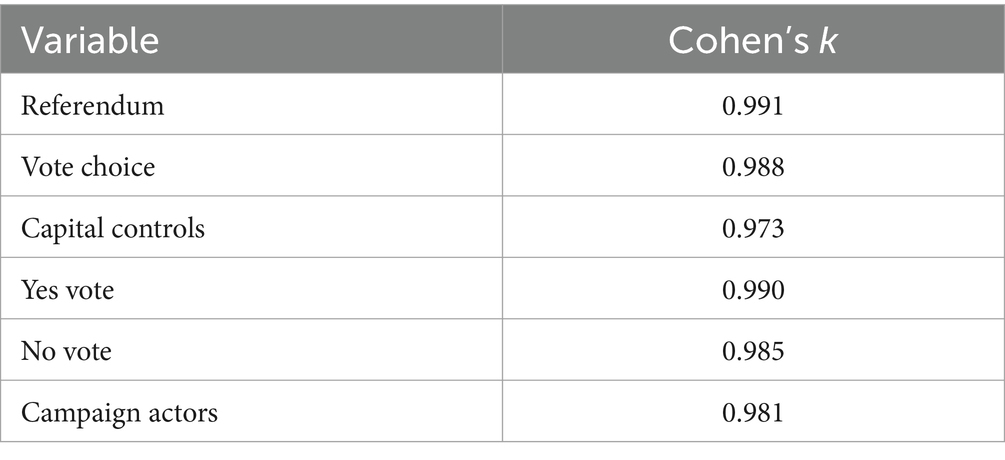

The online news media dataset was analyzed through in-depth manual qualitative and quantitative content analysis based on a codebook that was informed by the theoretical framework of agenda-setting to identify the major topics in terms of their frequency, prominence, and valence (Neuendorf, 2016). So, we focused on the higher frequency of an issue and then on its actual meaning so we could examine the prominence and valence of the respective issues. The main variables were mined after two rounds of pilot analysis of news articles and various iterations of coding among the coders, which aimed at acquiring the best training. The coders were asked to code each news item according to a list of variables: (1) explicit or implicit evaluative judgments about the referendum: e.g. valid, invalid, democratic, undemocratic, coercive, unnecessary (Referendum), (2) the vote choice (Vote Choice), (3) the capital controls as a consequence of the referendum (Capital Controls),(4) the “Yes” vote effects (Yes vote), (5) the “No” vote effects (No vote), (6) explicit or implicit evaluative judgments about the campaign actors (e.g.EU and national officials and political leaders, domestic opposition from the right- and left-wing parties, politicians, media) (Campaign Actors). The total sample of 913 articles is separated into two subsets. The first subset of the 494 news articles was coded by two coders. The two coders coded this part of the sample independently and their disagreements were by a third coder. Cohen’s k was run on SPSS to measure intercoder reliability between the two coders on 494 newspaper articles. There was almost perfect agreement between the two coders on the six variables as shown in Table 3.

3.4 Analysis of tweets

The annotation of tweets was performed with the aid of Appen8 -formerly known as crowdsourcing and crowdtagging platform by using the invitation to annotators function. This way, two trained, Greek-speaking annotators per tweet were assigned. The annotators were asked to (a) express their opinion on whether the tweet that was presented to them was referring to the vote choice on the referendum, and (b) choose the favored opinion (“YES,” “NO,” “Neutral”) of the tweet regarding the question posed to the voters in the referendum: “the draft agreement submitted by the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund to the Eurogroup on 25.06.2015 must be accepted.” The annotators agreed, regarding the tweet position (second question), on 91.7% of the tweets while disagreements were resolved by a third coder. Cohen’s k, that was used to determine intercoder reliability, was found to be 0.833 regarding the first question (i.e., whether the tweet refers to the vote choice in the referendum). In that way, we can see how many sets of tweets were created about “Yes,” and “No” supporters and neutral users. Each of these groups’ tweets is submitted to a computer-assisted analysis (topic modeling), which detects the presence of key referendum issues. Using our partisan of users, we can then separate the content using topic models to examine what was said by each side (Yes side, No side, and Neutral side). Then, we compared the two agendas (social media agenda and news media agenda). Below we provide a short recap so as for the reader to better understand the method as well as the complexity compared to other methods.

3.5 Topic modeling

For the topic modeling of the annotated tweets, we followed the procedure described in Tsapatsoulis, 2020 and Argyrou et al. (2018). First, topics are created from the collection of tweets relevant to the Greek referendum in 2015. This results in a set of topics S = {T, T,.., T,..T}. Second, the matching score of a tweet $\mathcal{H}_i$ with each one of the topics $\mathcal{T}_t$ is computed. Both $\mathcal{H}_i$ and $\mathcal{T}_t$ are sets of words while the latter also includes the importance of each word expressed through its relative frequency in the topic. The matching score of a tweet Hi with each one of the topics Tt is computed. Both Hi and Tt are sets of words while the latter also includes the importance of each word expressed through its relative frequency in the topic. The matching score R (Hi, Tt) between these two sets can be computed as a weighted sum of the pair similarities of their word embeddings (Mikolov et al., 2013) used for the Glove project9. This is the approach we followed in the past when dealing with English text(s). However, the tweets collected for the current work are in Greek and, to the best of our knowledge, there are no pre-trained word embeddings for the Greek words. Thus, we decided to compute the similarity of words through simple string matching10 as shown in Equation 1.

where |A| denotes the cardinality of set A,h is the j-th token of tweet Hi, w is the q-th word of topic Tt, α[w ] is the authority score, computed with the aid of the HITS (Hyperlink-Induced Topic Search) algorithm (Giannoulakis and Tsapatsoulis, 2019), of word w and cc(.,.) is the string similarity measure mentioned above. In the third step, the best matching, to the tweet Hi, topic T (Hi) is selected with aid of Equation 2:

4 Results

4.1 The agenda of news media

The content analysis of the news media articles unfolded three main topics, which covered largely the referendum campaign. The most discussed topic was that of “vote choice” (52.0%), followed by the “referendum” (38.7%) and then by a bit more than one-fourth (27.4%) the topic of “capital controls.”

The first topic, which is the most frequently discussed issue in the online press, was the reference to the “vote choice.” Some newspaper articles referred to the vote choice and its meaning in general, some others characterized the “No” vote and the actors who backed the “No” and its potential consequences whereas others focused on the “Yes” vote, the actors who supported it as well as its potential outcomes. The second topic was the reference to the “referendum.” The respective news items focused on the decision to hold a referendum and whether this was positive or negative, or an unanticipated political move that raised a wave of controversy among international and domestic political actors. Some other aspects regarding the referendum discussed its legality and legitimacy, its political denotations, and the unclear consequences. The third topic involves discussions on “capital controls.” Following Prime Minister Tsipras’ announcement of the referendum on June 28, Eurozone finance ministers opted against extending the ongoing bailout program scheduled to conclude 3 days later. Consequently, the European Central Bank (ECB) declared its decision not to augment Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) funds, citing the absence of a bailout program as justification. Consequently, Greek authorities declared a bank holiday and imposed capital controls on June 28. Our analysis reveals that online press articles reference the imposition of capital controls, expounding on the rationales behind them and detailing their anticipated consequences.

The three topics were reported with either a factual (the content was rather neutral) or an evaluative tone (a specific position was expressed in relation to the topic). More specifically, all issues were reported factually without the expression of any critical stance by the following frequency: “capital controls” by 20.4%, “vote choice” by 16.0% and the “referendum” by just 7.4%. Factual reporting is equivalent to the agenda setting mechanism of the media, signaling to a frequent, thus important set of topics yet without manifesting a clear position (McCombs and Funk, 2011).

All issues were also reported with an evaluative tone, which is part of the second-level agenda-setting process, namely priming (Valenzuela and McCombs, 2021). More specifically, 36.0% of the articles that referred to the “vote choice” adopted a position pro or against the “No” or “Yes” to the referendum, with the majority of them (20.4%) containing a position supporting the “YES” vote, being against the prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, the Left, the party of SYRIZA, and the government. Their argumentation was sustained by the danger of “Grexit” as an effect of a “NO” vote. In contrast, only 9.1% of the evaluative reporting on the “vote choice” contained a positive position of the prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, putting forward the benefits of the “NO” vote to the referendum. The argumentation in this case was based on presenting the referendum as “Victory of Democracy” while the “NO” vote choice was portrayed as an act of resistance by the Greeks against the Europeans and the Creditors. The second topic of the “referendum” was also discussed from an evaluative perspective to a slightly smaller extent (31.3%) than the “vote choice.” Most articles characterized the referendum negatively (22.1%) (such as unexpected, unnecessary, adventurous, polarized, undemocratic unconstitutional and even as a parody) and just 9.2% discussed it in positive terms (as democratic and necessary). Concerning “capital controls,” the evaluative tone was identified in 7.0% of the articles which were all presenting this topic negatively, as an inevitable consequence of calling the referendum.

4.2 The topics discovered in Twitter

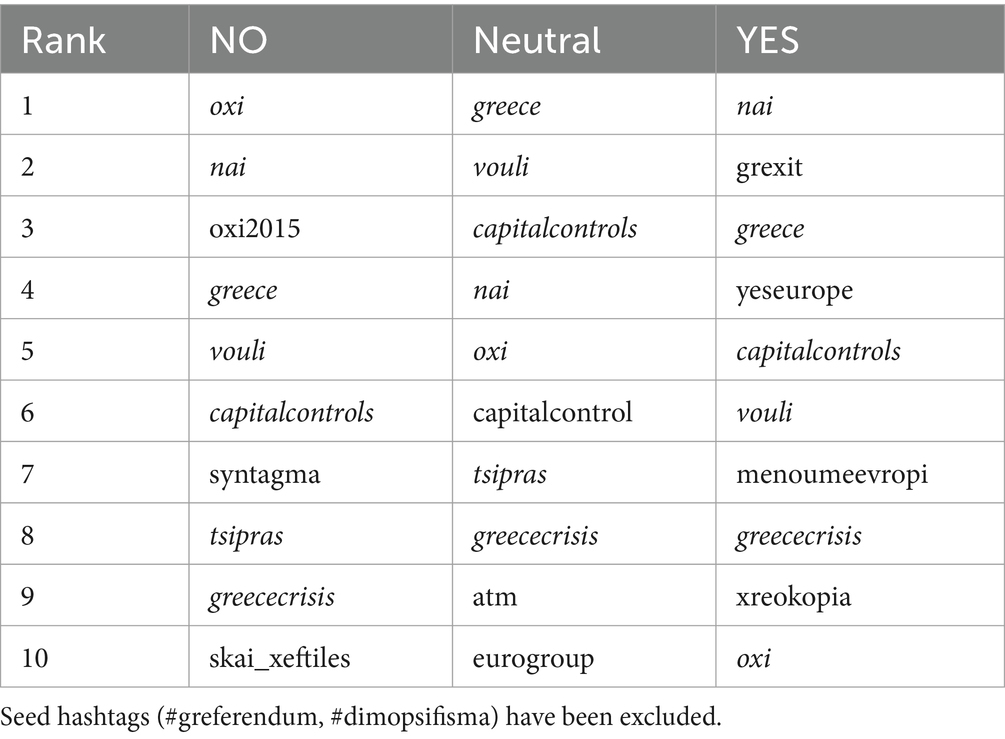

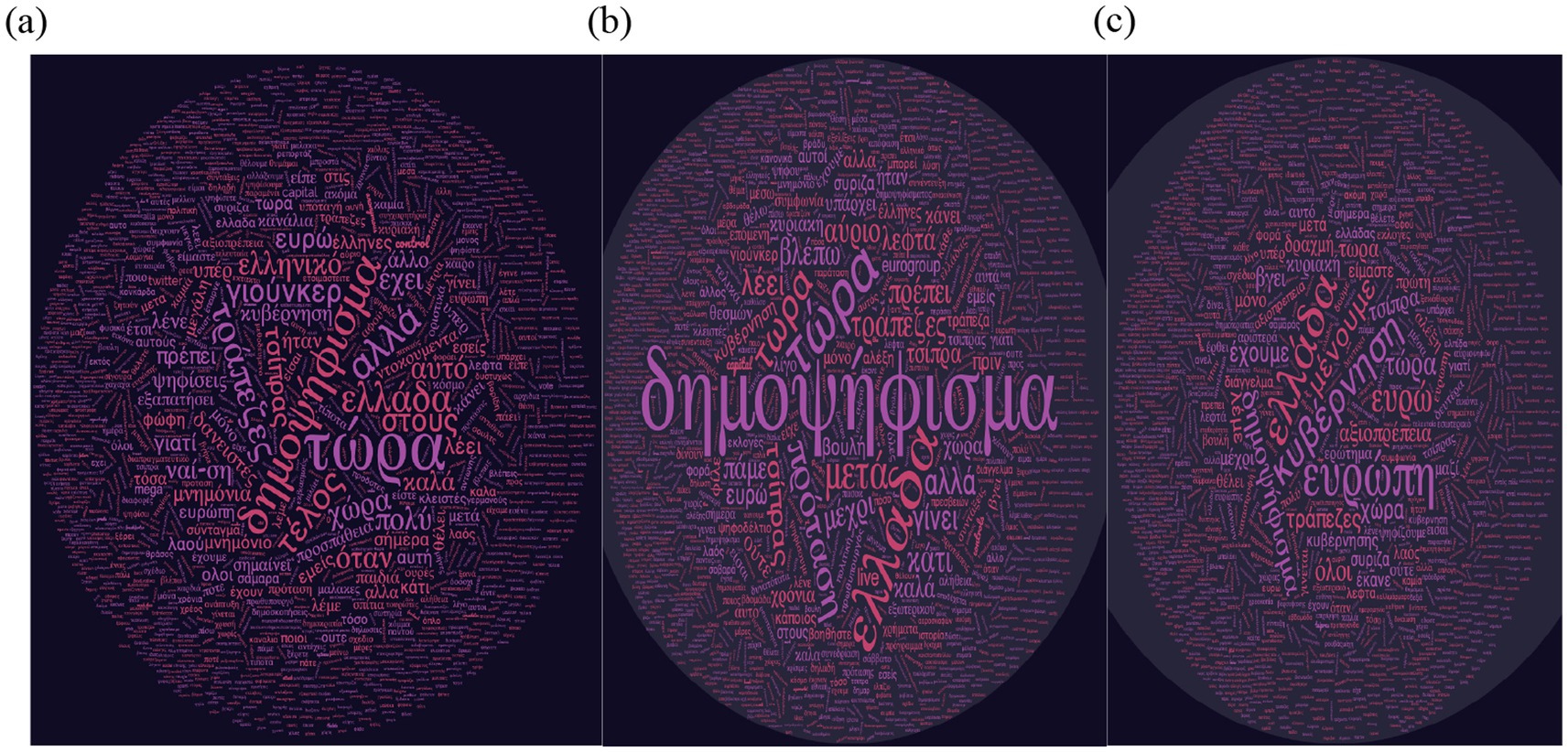

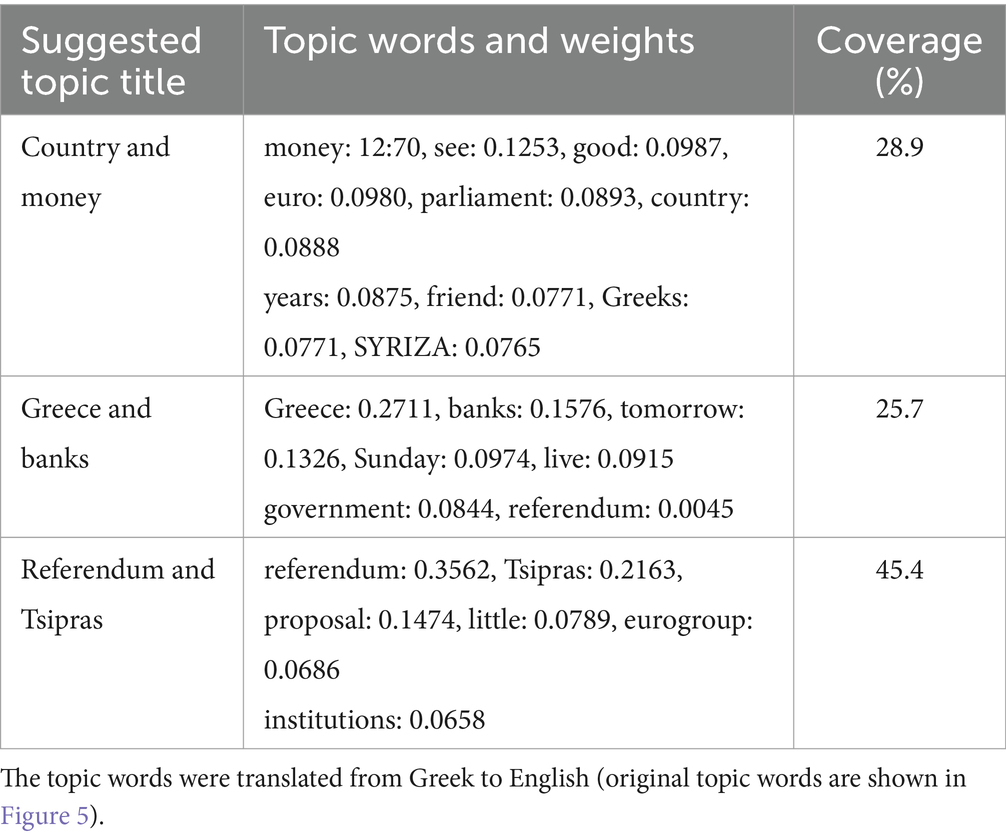

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the dataset prior to delving into specific topics, an analysis of the distribution of the most frequently used hashtags was undertaken (see Table 4). Figure 1 shows that the most prevalent hashtags among “No” vote supporters are “oxi,” “nai,” and “oxi2015,” with “skai_xeftiles” highlighting their critical stance towards mainstream media. “Yes” vote supporters predominantly use “nai,” “Grexit,” and “Greece,” emphasizing themes of affirmative sentiments, and potential EU and euro exit. Notably, neutral users and both “No” and “Yes” supporters share common hashtags such as “capital controls,” “nai,” “oxi,” “Greece,” “vouli,” and “Greece crisis,” reflecting a collective focus on fiscal restrictions, voting preferences, parliamentary activities, and socio-economic challenges in Greece (see Figure 1). This strategic use of hashtags underscores their role in shaping socio-political discourse, particularly during referendums or elections.

Figure 1. Hashtags wordcloud for NO (left), neutral (center) and YES (right) tweets. Seed hashtags (#greferendum, #dimopsifisma) have been excluded.

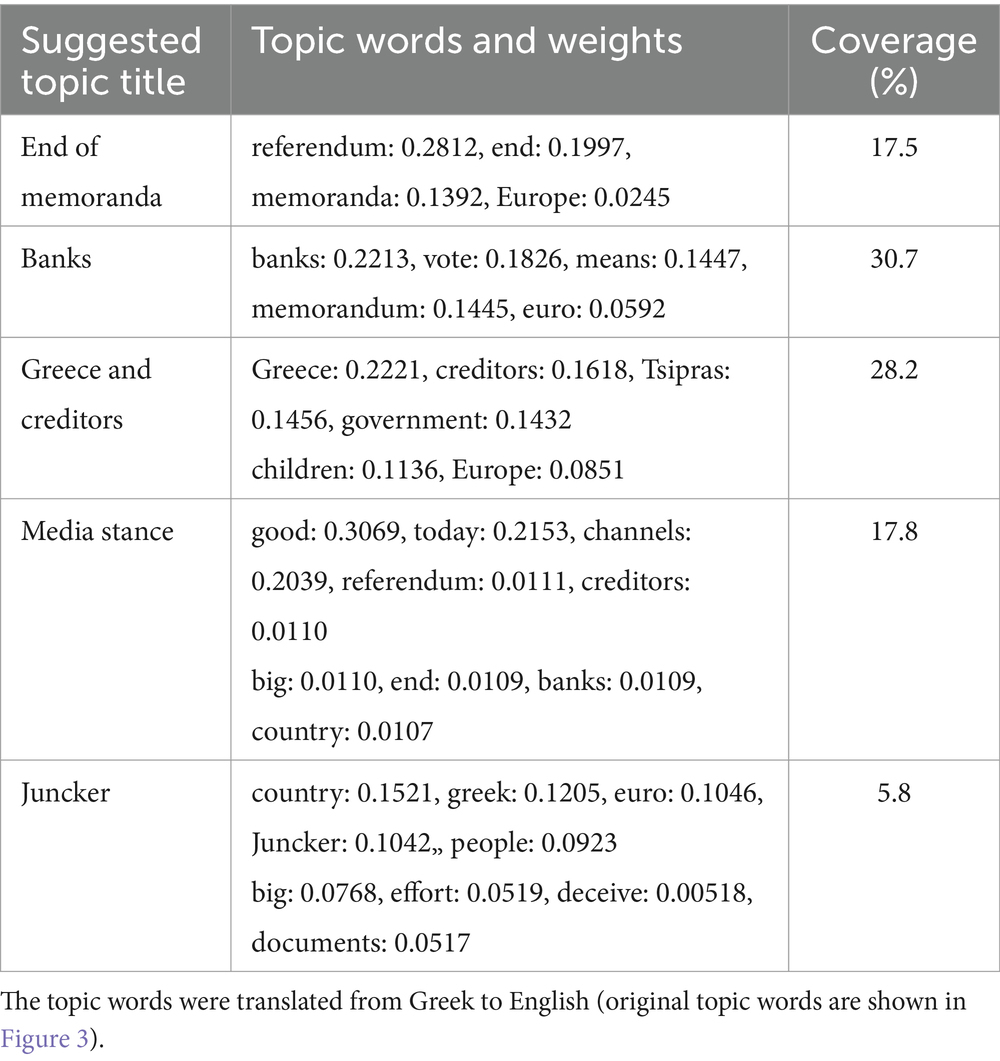

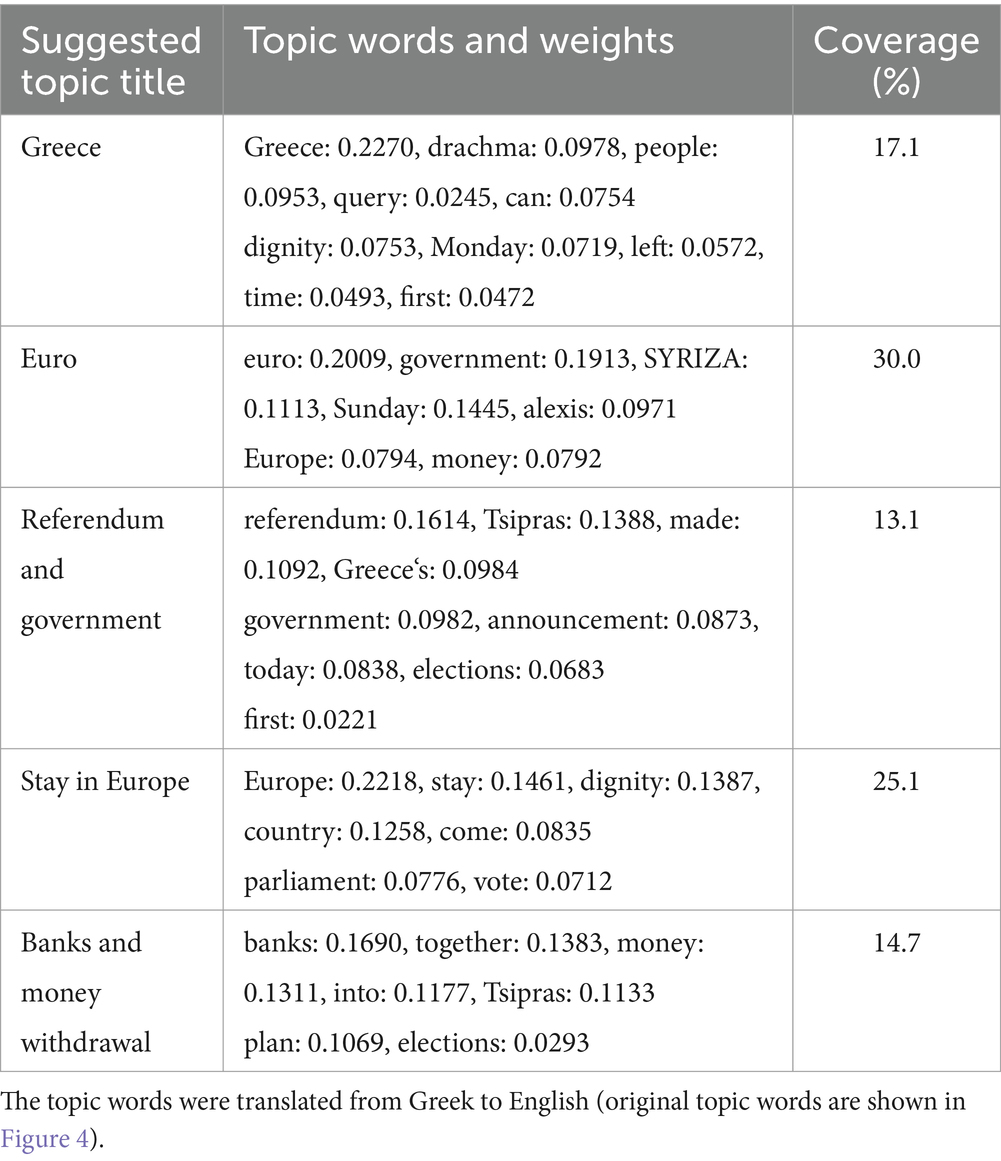

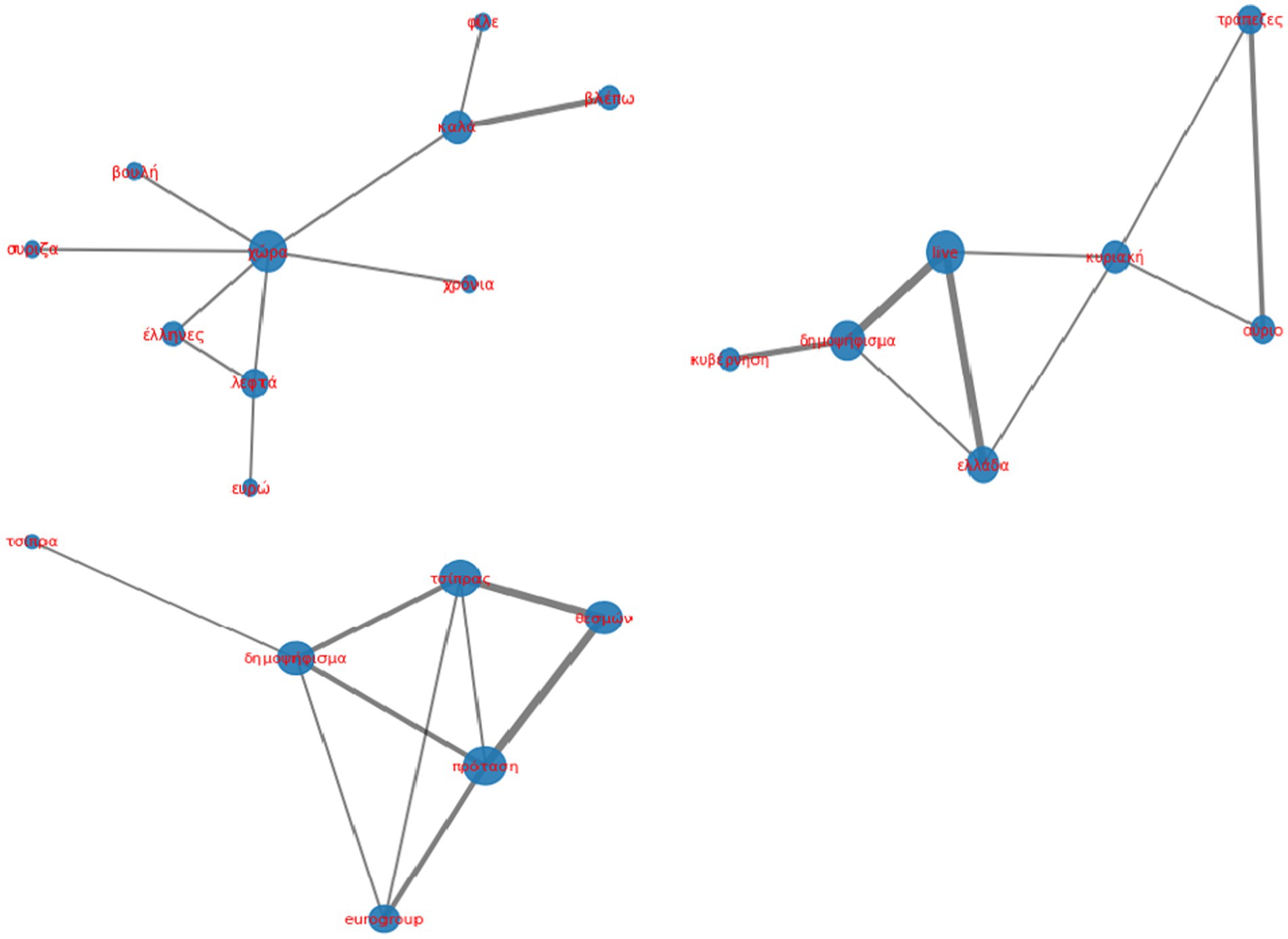

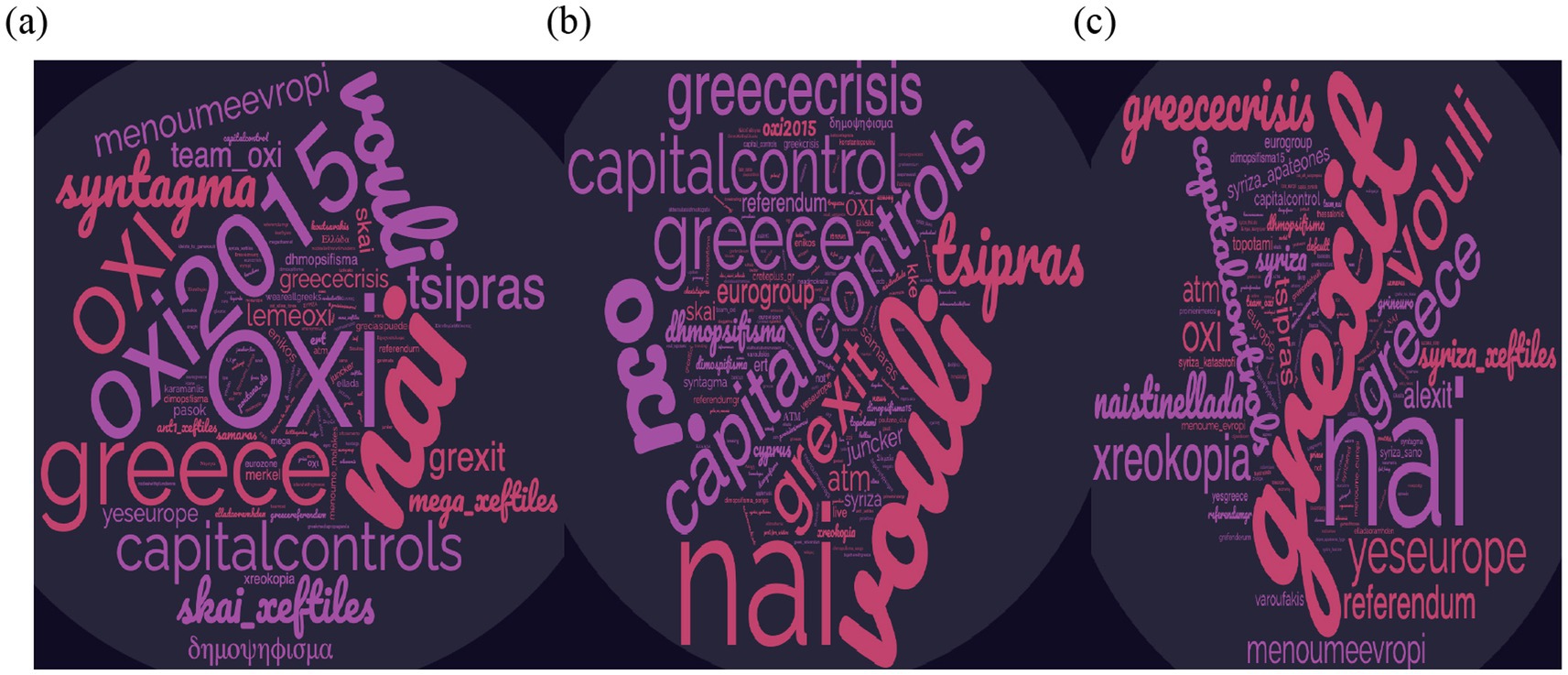

Looking at the users’ voices through Twitter, Table 5 shows that “NO” vote supporters referred to three major topics, the “Creditors and banks,” the “media stance” and the “End of memoranda.” In the case of the Greek referendum, we observe a marked degree of anti-news media sentiment among the “NO” vote supporters in Twitter. These identified topics occupy a relatively marginal space within the online press, finding primary coverage in alternative news media outlets and the public broadcaster (ert.gr), which traditionally reflects the government’s viewpoint. Consequently, it becomes apparent that the agenda articulated by Twitter users aligning with the “NO” vote significantly diverges from that of the news media and especially the legacy newspapers. This observation underscores the distinctive perspectives and priorities present in the online discourse compared to the narrative propagated by news media channels. In contrast, Table 6 shows that “YES” vote supporters referred to the “stay in Europe declaration and euro” and criticize the way the government of SYRIZA handled the referendum issue. These topics coincide with the agenda of online press. Both news media and the “YES” supporters on Twitter presented the “NO” vote as a “No” to Europe and the Eurozone and criticized the Prime Minister (of that period) Tsipras and his government. This convergence in narrative highlights a notable correspondence between the perspectives presented by news media and those expressed by Twitter users who advocated for the “YES” vote. The shared emphasis on key themes reveals a considerable coherence in the agenda pertaining to the referendum, thus underscoring the continued influence of news media on shaping the discussions within the realm of social media. This convergence implies an intricate interplay where news media not only reflects but also significantly influences the topics and priorities echoed in the Twittersphere (Figures 1,2).

Figure 3. Visual presentation of topics extracted from tweets expressing the “NO” opinion in the referendum.

Figure 4. Visual presentation of topics extracted from tweets expressing the “YES” opinion in the referendum.

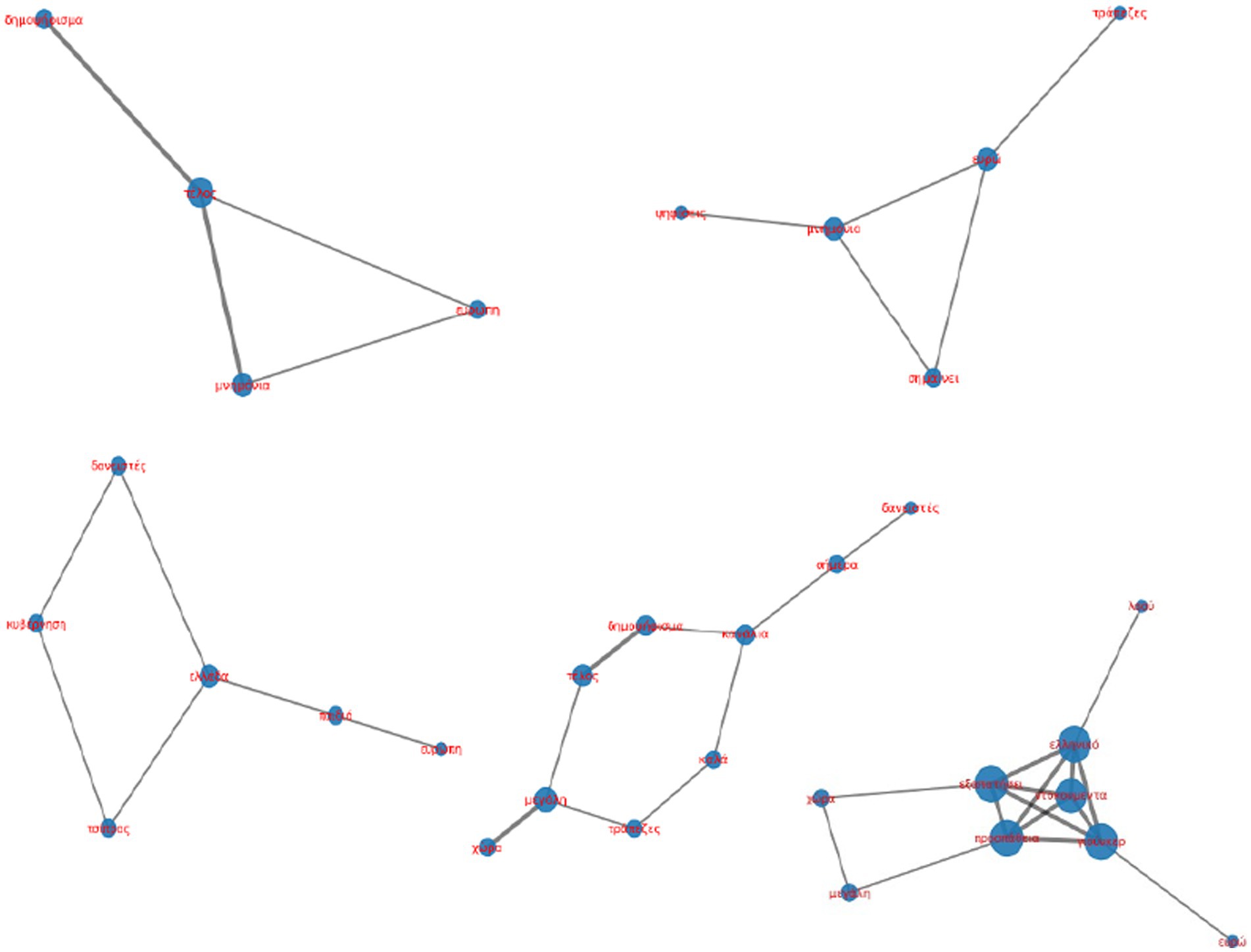

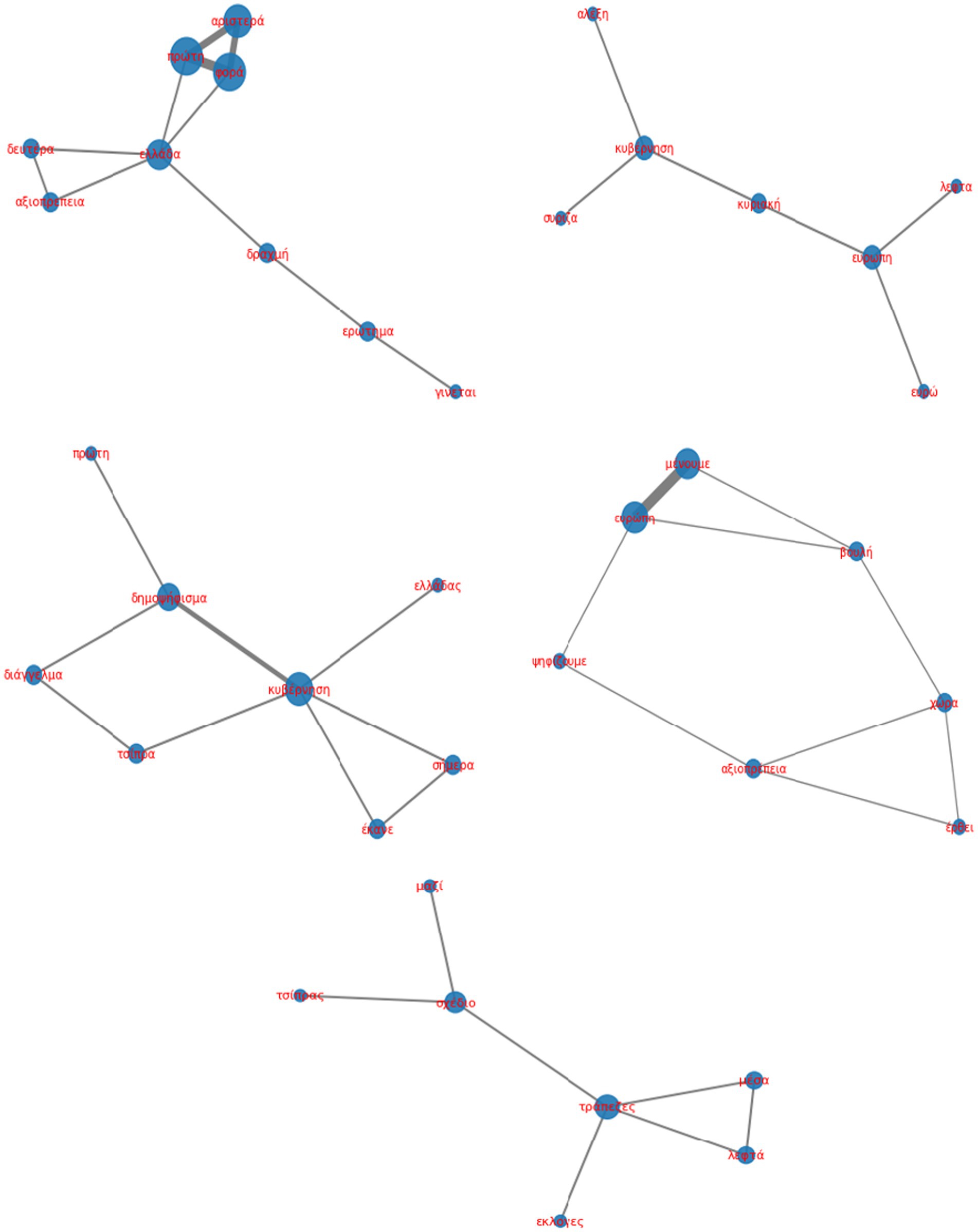

The three neutral topics pertinent to the Twitter discussion surrounding the referendum vote exhibit a propensity for informativeness (see Figure 5). As Table 7 shows Twitter users have prominently alluded to three main topics, namely, “Referendum and Tsipras,” “Greece and banks,” and “Country and money.” These topics not only encapsulate the core elements of the referendum discussion but also emanate a tone of factual representation. While news media outlets critiqued the referendum and the government, attributing risk to the country’s future and its EU orientation, neutral Twitter users refrained from characterizing the referendum as undemocratic, unconstitutional, or unnecessary. Furthermore, these users did not articulate concerns about Greece’s future. This disparity suggests a notable divergence in the evaluative aspects, which is part of the second level of the agenda-setting process, emphasized by news media and neutral Twitter users. The absence of explicit criticisms or concerns among neutral Twitter users underscores their proclivity toward factual and informative discussions, indicating a distinct pattern in the discussion compared to the evaluative and critical tone prevalent in news media coverage.

4.3 Comparing news and social media agendas

Social media displayed a lower likelihood of addressing some topics compared to news media. Specifically, the comparative analysis between social media and news media reveals a discernible discrepancy in the emphasis placed on main issues such as the “referendum” and “capital controls,” encompassing factual reporting and evaluative dimensions. News media demonstrated a notable proclivity towards extensively referencing and evaluating the “referendum” and “capital controls” instead of social media, where these references were markedly limited (see Figure 1). While news media outlets critiqued the referendum and the government, attributing risk to the country’s future and its EU orientation, neutral Twitter users refrained from characterizing the referendum as undemocratic, unconstitutional, or unnecessary (see Table 5). The conspicuous absence of overt criticisms or apprehensions within the agenda of neutral Twitter users accentuates their inclination toward engaging in factual and informative discussions specifically on the topic of the “referendum.” This observation highlights a distinct pattern in the discussion among neutral users, in stark contrast to the evaluative and critical tone that characterizes the coverage related to the topic of the “referendum” within news media coverage. Moreover, Twitter users discussed the issue of the “vote choice” and took a position to campaign actors (prime minister, Creditors, Europeans, news media). This observed stance suggests a remarkable emphasis within the Twitter discourse on political actors involved in the referendum context. Specifically, the discussions revolved around articulating positions either against the government or against actors aligning with the “Yes” vote, highlighting the multifaceted nature of public discourse on the platform. Our investigation revealed a discernible efficacy of news media in predicting the issues highlighted by “Yes” supporters on Twitter (see Table 4). Twitter highlights alternative evaluative salient issues, specifically accentuating negative judgments directed towards actors advocating the “Yes” vote and critical assessments of news media (see Table 3). Overall, our results show that each type of media had a different agenda, not so much in terms of the subject matter but the direction of the issues.

5 Discussion and conclusion

The ways in which the news media put together different topics to discuss the referendum corresponded well with how the “YES” supporters in Twitter talked about the issue. The latter were more attentive to the news media agenda than the “NO” supporters. In particular, in the current study we found that the news media agenda could best explain the topics dominated among the Twitter “YES” supporters. On the contrary, although news media seek to reach the largest audiences possible by definition (Vargo et al., 2014; Bachmann et al., 2021), such media did not play a significant role in the topics that dominated the tweets of the ‘NO” supporters during the 2015 Greek referendum. In the past, it has been argued that online information is dominated by mainstream media outlets and political elites (Hindman, 2009). However, it seems that the interactive layout of social media can break this dominance (Meraz and Papacharissi, 2013; Ceron, 2015) by favoring peer-to-peer information sharing and overstepping the established hierarchy, typical of mainstream media (Hermida, 2013). The comparison between the different types of media supported that overall, Twitter is characterized by more diversity and independence. Our findings suggest that news media still make part of the social media agenda, although, in some way, Twitter also hosted alternative voices and highlighted different topics compared to the news media agenda. During the Greek referendum, Twitter functioned as an alternative media platform by advancing a different agenda, particularly in terms of evaluation (second level of agenda-setting). While traditional news media overwhelmingly promoted the “Yes” vote and framed the referendum negatively in a significant portion of their coverage, Twitter users concentrated more on the vote itself, with a substantial majority favoring the “No” vote and offering critical commentary on the mainstream news media’s agenda. This divergence in second-level agenda-setting underscores Twitter’s role in shaping a narrative that contrasts with that of mainstream news outlets. Furthermore, it demonstrates Twitter’s potential as a valuable information source for entity-oriented issues that receive little to no coverage in traditional news media. Our analysis concludes that Twitter hosted alternative and different voices (at least regarding the referendum), which did not manage to get their spin across in news media. These findings seem to suggest, once again, that social media has changed the nature of campaigns and play a key role in the elections and especially in referendums (Bright et al., 2019; Gilardi et al., 2021). The contemporary digital landscape, particularly within the realm of social media, has transformed citizens into proactive contributors, shaping and influencing opinions through their active engagement with diverse content and interactive discussions. Users actively engage with a variety of content and participate in interactive discussions, creating a vibrant digital public sphere where diverse viewpoints can coexist. This phenomenon challenges the traditional gatekeeping role of news media. Our results point to the role of social media to set the agenda and formatting the users’ opinion. The interaction between news media and social media, as highlighted in the present paper, introduces a complex interplay between institutionalized journalism and user-generated content. Investigating the dynamics of this interaction becomes crucial for understanding how information circulates, gains prominence, and ultimately shapes public opinion and influence the democratic process. In this setting, the interaction of news and social media is becoming an increasingly important area for future research.

5.1 Conclusion and further work

In this paper, we presented the topics that emerged from news and social media during the 2015 Greek Bailout referendum campaign. Through a comparative analysis of the identified topics, we have highlighted the differences between the agenda of news media and Twitter in Greece. The referendum unfolded against a backdrop of heightened polarization, and during that period Twitter turned out as an important tool of public opinion formation. The result of the referendum and the dominance of the “NO” vote showed that Twitter won the battle of public opinion compared to online media. However, recent history shows that this is not always the case. The result of the last parliamentary elections in Greece (May 2023) put forward an entirely different picture. This is elaborately explained by the latest studies about the influence of social media in politics and the echo chamber effect in Twitter (Tsai et al., 2020). Future research should address the role of other social media, such as TikTok, in opinion formation related to politics. Notably, TikTok played a significant and influential role during the European parliamentary election campaign in Cyprus in June 2024. The victorious candidate, Fidias Panayiotou, effectively used the platform to connect with young voters, presenting a modern political image and becoming the first “influencer politician” elected to the European Parliament. Finally, the evolving landscape of social media dynamics, especially considering the recent changes under Elon Musk’s leadership at Twitter, raises intriguing questions about the continued influence of these platforms in politics. It becomes pertinent to explore whether the most influential social media platforms will persist in playing a central role or potentially shift toward a more consumerist trajectory, aligning with the ambitions of their respective owners. This dynamic interaction of media and politics offers a rich avenue for exploration in future research.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human data in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not required, for either participation in the study or for the publication of potentially/indirectly identifying information, in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platform's terms of use and all relevant institutional/national regulations.

Author contributions

N-MS: Writing – original draft. VT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This article utilizes the nomenclature corresponding to the social media platform formerly identified as Twitter, the brand “Twitter” was the name of the platform during the period coinciding with the Greek referendum. In April 2023, it is notable that Twitter transformed X Corp., after the decision made by the newly appointed owner and CEO, Elon Musk, to merge Twitter with X Holdings.

2. ^https://about.twitter.com/

4. ^https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2098

5. ^https://www.huffingtonpost.gr/

7. ^https://docs.tweepy.org/en/stable/streaming.html

9. ^https://nlp.stanford.edu/projects/glove/

10. ^https://towardsdatascience.com/sequencematcher-in-python-6b1e6f3915fc

References

Ahmed, S., Madrid-Morales, D., and Tully, M. (2022). Social media, misinformation, and age inequality in online political engagement. J. Inform. Tech. Polit. 20, 269–285. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2022.2096743

Amador Diaz Lopez, J. C., Collignon-Delmar, S., Benoit, K., and Matsuo, A. (2017). Predicting the Brexit vote by tracking and classifying public opinion using twitter data. Statistics Polit. Policy 8, 85–104. doi: 10.1515/spp-2017-0006

Argyrou, A., Giannoulakis, S., and Tsapatsoulis, N. (2018). Topic modelling on Instagram hashtags: An alternative way to automatic image annotation? in Proceedings of the 13th International Workshop on Semantic and Social Media Adaptation and Personalization, ser. SMAP. IEEE, 61–67.

Bachmann, P., Eisenegger, M., and Ingenhoff, D. (2021). Defining and measuring news media quality: comparing the content perspective and the audience perspective. Int. J. Press 27, 9–37. doi: 10.1177/1940161221999666

Bennett, W. L., and Pfetsch, B. (2018). Rethinking political communication in a time of disrupted public spheres. J. Commun. 68, 243–253. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqx017

Bossetta, M. (2018). The digital architectures of social media: comparing political campaigning on Facebook, twitter, Instagram, and snapchat in the 2016 U.S. election. J. Mass Commun. Q. 95, 471–496. doi: 10.1177/1077699018763307

Boukala, S., and Dimitrakopoulou, D. (2016). The politics of fear vs. the politics of hope: analysing the 2015 Greek election and referendum campaigns. Crit. Discourse Stud. 14, 39–55. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2016.1182933

Boulianne, S. (2015). Social media use and participation: a meta-analysis of current research. Inf. Commun. Soc. 18, 524–538. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1008542

Boyd, D., and Crawford, K. (2012). Critical questions for big data. Inf. Commun. Soc. 15, 662–679. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878

Bright, J., Hale, S., Ganesh, B., Bulovsky, A., Margetts, H., and Howard, P. (2019). Does campaigning on social media make a difference? Evidence from candidate use of twitter during the 2015 and 2017 U.K. elections. Commun. Res. 47, 988–1009. doi: 10.1177/0093650219872394

Ceron, A. (2015). Internet, news, and political trust: the difference between social media and online media outlets. J. Comput. Mediated Commun. 20, 487–503. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12129

Coddington, M., and Holton, A. E. (2013). When the gates swing open: examining network gatekeeping in a social media setting. Mass Commun. Soc. 17, 236–257. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2013.779717

Coleman, R., and Wu, H. D. (2021). Individual differences in affective agenda setting: a cross-sectional analysis of three U.S. presidential elections. Journalism 23, 992–1009. doi: 10.1177/1464884921990242

Conway, B. A., Kenski, K., and Wang, D. (2015). The rise of twitter in the political campaign: searching for intermedia agenda-setting effects in the presidential primary. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 20, 363–380. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12124

De Vreese, C. H., and Semetko, H. A. (2002). Cynical and engaged. Commun. Res. 29, 615–641. doi: 10.1177/009365002237829

Egelhofer, J. L., and Lecheler, S. (2019). Fake news as a two-dimensional phenomenon: a framework and research agenda. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 43, 97–116. doi: 10.1080/23808985.2019.1602782

Gaber, I., and Fisher, C. (2021). ‘Strategic lying’: the case of Brexit and the 2019 U.K. election. Int. J. Press 27, 460–477. doi: 10.1177/1940161221994100

Giannoulakis, S., and Tsapatsoulis, N. (2019). Filtering instagram hashtags through crowdtagging and the hits algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 6, 592–603.

Gil de Zúñiga, H., and Diehl, T. (2018). News finds me perception and democracy: effects on political knowledge, political interest, and voting. New Media Soc. 21, 1253–1271. doi: 10.1177/1461444818817548

Gilardi, F., Gessler, T., Kubli, M., and Müller, S. (2021). Social media and political agenda setting. Polit. Commun. 39, 39–60. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2021.1910390

Grossman, E. (2022). Media and policy making in the digital age. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 25, 443–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051120-103422

Gueorguieva, V. (2007). Voters, MySpace, and YouTube. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 26, 288–300. doi: 10.1177/0894439307305636

Gulati, J., and Williams, C. B. (2010). Communicating with constituents in 140 characters or less: twitter and the diffusion of technology innovation in the United States congress. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1628247 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1628247

Hansen, M. E., Shughart, W. F., and Yonk, R. M. (2017). Political party impacts on direct democracy: the 2015 Greek austerity referendum. Atl. Econ. J. 45, 5–15. doi: 10.1007/s11293-016-9528-0

Harder, R. A., Sevenans, J., and Van Aelst, P. (2017). Intermedia agenda setting in the social media age: how traditional players dominate the news agenda in election times. Int. J. Press. 22, 275–293. doi: 10.1177/1940161217704969

Holt, K., Shehata, A., Strömbäck, J., and Ljungberg, E. (2013). Age and the effects of news media attention and social media use on political interest and participation: do social media function as leveller? Eur. J. Commun. 28, 19–34. doi: 10.1177/0267323112465369

Jackson, L., and Valentine, G. (2014). Emotion and politics in a mediated public sphere: questioning democracy, responsibility and ethics in a computer mediated world. Geoforum 52, 193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.01.008

Katsambekis, G., and Souvlis, G. (2018). “EU referendum 2016 in the Greek press” in Reporting the road to Brexit. eds. A. Ridge-Newman, F. León-Solís, and H. O'Donnell (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan).

Khabaz, D. (2018). Framing Brexit: the role, and the impact, of the national newspapers on the EU referendum. Newsp. Res. J. 39, 496–508. doi: 10.1177/0739532918806871

Kim, C., and Lee, S. (2021). Does social media type matter to politics? Investigating the difference in political participation depending on preferred social media sites. Soc. Sci. Q. 102, 2942–2954. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.13055

Kluknavská, A., and Eisele, O. (2021). Trump and circumstance: Introducing the post-truth claim as an instrument for investigating truth contestation in public discourse. Inform. Commun. Soc., 1–18. doi: 10.1080/1369118x.2021.2020322

Lee, S., and Xenos, M. (2020). Incidental news exposure via social media and political participation: evidence of reciprocal effects. New Media Soc. 24, 178–201. doi: 10.1177/1461444820962121

Levy, D. A. L., Aslan, B., Bironzo, D., and For, I. (2016). UK press coverage of the EU referendum. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Loader, B. D., Vromen, A., and Xenos, M. A. (2014). The networked young citizen: social media, political participation and civic engagement. Inf. Commun. Soc. 17, 143–150. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.871571

McCombs, M., and Funk, M. (2011). Shaping the agenda of local daily newspapers: a methodology merging the agenda setting and community structure perspectives. Mass Commun. Soc. 14, 905–919. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2011.615447

McGregor, S. C. (2019). Social media as public opinion: how journalists use social media to represent public opinion. Journalism 20, 1070–1086. doi: 10.1177/1464884919845458

McKelvey, K., DiGrazia, J., and Rojas, F. (2014). Twitter publics: how online political communities signaled electoral outcomes in the 2010 US house election. Inf. Commun. Soc. 17, 436–450. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2014.892149

Meraz, S., and Papacharissi, Z. (2013). Networked gatekeeping and networked framing on #Egypt. Int. J. Press 18, 138–166. doi: 10.1177/1940161212474472

Neuendorf, K. A. (2016). The Content Analysis Guidebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Prendergast, M., and Quinn, F. (2020). Justice reframed? A comparative critical discourse analysis of twitter campaigns and print media discourse on two high-profile sexual assault verdicts in Ireland and Spain. J. Pract. 15, 1613–1632. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2020.1786436

Rogstad, I. (2016). Is twitter just rehashing? Intermedia agenda setting between twitter and mainstream media. J. Inform. Tech. Polit. 13, 142–158. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2016.1160263

Schuck, A. R. T., and de Vreese, C. H. (2008). Reversed mobilization in referendum campaigns. Int. J. Press 14, 40–66. doi: 10.1177/1940161208326926

Shaw, A. (2012). Centralized and decentralized gatekeeping in an open online collective. Polit. Soc. 40, 349–388. doi: 10.1177/0032329212449009

Siapera, E., Papadopoulou, L., and Archontakis, F. (2014). Post-crisis journalism. J. Stud. 16, 449–465. doi: 10.1080/1461670x.2014.916479

Sools, A., Triliva, S., Fragkiadaki, E., Tzanakis, M., and Gkinopoulos, T. (2018). The Greek referendum vote of 2015 as a paradoxical communicative practice: a narrative, Future-Making Approach. Polit. Psychol. 39, 1141–1156. doi: 10.1111/pops.12474

Spohr, D. (2017). Fake news and ideological polarization: filter bubbles and selective exposure on social media. Bus. Inf. Rev. 34, 150–160. doi: 10.1177/0266382117722446

Su, Y., and Borah, P. (2019). Who is the agenda setter? Examining the intermedia agenda-setting effect between twitter and newspapers. J. Inform. Tech. Polit. 16, 236–249. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2019.1641451

Su, Y., and Xiao, X. (2024). Intermedia attribute agenda setting between the U.S. mainstream newspapers and twitter: a two-study analysis of the paradigm and driving forces of the agenda flow. J. Mass Commun. Q. 101, 451–476. doi: 10.1177/10776990231221150

Theocharis, Y., Lowe, W., van Deth, J. W., and García-Albacete, G. (2014). Using twitter to mobilize protest action: online mobilization patterns and action repertoires in the Occupy Wall street, indignados, and Aganaktismenoi movements. Inf. Commun. Soc. 18, 202–220. doi: 10.1080/1369118x.2014.948035

Tian, Y. (2023). Fragmented narrative: Telling and interpreting stories in the Twitter age. The Communication Review 26, 94–97. doi: 10.1080/10714421.2023.2165768

Tsai, W.-H. S., Tao, W., Chuan, C.-H., and Hong, C. (2020). Echo chambers and social mediators in public advocacy issue networks. Public Relat. Rev. 46:101882. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101882

Tumasjan, A., Sprenger, T., Sandner, P., and Welpe, I. (2010). Predicting elections with twitter: what 140 characters reveal about political sentiment. Proceed. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 4, 178–185. doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v4i1.14009

Valenzuela, S., and Mccombs, M. (2021). Setting the agenda: The news media and public opinion. 3rd ed. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Vargo, C. J., and Guo, L. (2016). Networks, big data, and intermedia agenda setting: an analysis of traditional, partisan, and emerging online U.S. News. J. Mass Commun. Q. 94, 1031–1055. doi: 10.1177/1077699016679976

Vargo, C. J., Guo, L., McCombs, M., and Shaw, D. L. (2014). Network issue agendas on twitter during the 2012 U.S. presidential election. J. Commun. 64, 296–316. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12089

Vergeer, M., Hermans, L., and Sams, S. (2011). Online social networks and micro-blogging in political campaigning. Party Polit. 19, 477–501. doi: 10.1177/1354068811407580

Vreese, C. H. D., and Semetko, H. A. (2004). News matters: influences on the vote in the Danish 2000 euro referendum campaign. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 43, 699–722. doi: 10.1111/j.0304-4130.2004.00171.x

Walter, S. (2021). Brexit domino? The political contagion effects of voter-endorsed withdrawals from international institutions. Comp. Pol. Stud. 54, 2382–2415. doi: 10.1177/0010414021997169

Wettstein, M. (2011). Frame adoption in referendum campaigns. Am. Behav. Sci. 56, 318–333. doi: 10.1177/0002764211426328

Walter, S., Dinas, E., Jurado, I., and Konstantinidis, N. (2018). Noncooperation by Popular Vote: Expectations, Foreign Intervention, and the Vote in the 2015 Greek Bailout Referendum. International Organization, 72, 969–994. doi: 10.1017/s0020818318000255

Xezonakis, G., and Hartmann, F. (2020). Economic downturns and the Greek referendum of 2015: evidence using night-time light data. Eur. Union Polit. 21, 361–382. doi: 10.1177/1465116520924477

Keywords: opinion formation, news media, social media, agenda setting, politics, opinion mining, topic modeling, content analysis

Citation: Sergidou N-M, Triga V and Tsapatsoulis N (2025) Media battles in the cybersphere: analyzing news and social media agendas during the 2015 Greek bailout referendum. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1477767. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1477767

Edited by:

Micah Altman, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, United StatesReviewed by:

Tiago Silva, University of Lisbon, PortugalDonatella Selva, University of Florence, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Sergidou, Triga and Tsapatsoulis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nelly-Maria Sergidou, bmVsbHlzZXJnaWRvdUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Nelly-Maria Sergidou

Nelly-Maria Sergidou Vasiliki Triga

Vasiliki Triga Nicolas Tsapatsoulis

Nicolas Tsapatsoulis