- Department of Government, Centre for Research on Discretion and Paternalism, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

Political trust is a fundamental component of democratic stability, yet its relationship with the quality of schooling remains underexplored. This study examines how both student-level perceptions of schooling—measured through distributive justice, procedural fairness, and functional effectiveness—and national-level investment in education influence political trust across 22 European countries. Using data from Round 2 of the European Social Survey (2004) and national-level education expenditure from the World Bank (2004–2006), this study employs multilevel modeling to assess the impact of quality of schooling on political trust. The results reveal that students’ perceptions of distributive justice, procedural fairness and functional effectiveness significantly impact political trust, alongside national-level spending in education. These findings highlight the role of education in shaping political attitudes and suggest that government commitment to educational quality can enhance trust in political institutions. The study offers important implications for policymakers, particularly in the context of ongoing debates on education privatization and public investment in schooling.

Introduction

Prior research on education and trust has identified two significant patterns. The first, widely substantiated, concerns the role of education in democratization, encompassing democratic consolidation, democratic legitimacy, and political trust. From this perspective, the duration or quantity of education an individual receives plays a crucial role in fostering political trust over time and across different societies (Kołczyńska, 2020; van Elsas, 2015). Education and political trust are closely linked, as individuals with higher levels of education are more likely to trust political institutions due to their enhanced cognitive abilities in understanding democratic processes (Hakhverdian and Mayne, 2012; Monsiváis-Carrillo and Cantú Ramos, 2022; van Elsas, 2015). The second perspective examines how students assess the quality of education through their daily interactions with educational institutions and authorities. Extensive evidence indicates that civic education strengthens political efficacy (Levy, 2013; Maurissen, 2020), increases political participation (Henn et al., 2002; Hooghe and Dassonneville, 2013), and enhances political trust among students (Kiess, 2022; Torney-Purta et al., 2004).

At the same time, schools function as essential sources of firsthand information about politics and society, introducing students to bureaucratic processes and public authorities—most notably, teachers—and facilitating interactions with what are commonly referred to as “street-level bureaucracies” (Claes et al., 2012; Lipsky, 1980). Furthermore, classrooms serve as unique arenas of justice, where teachers and students assume the roles of allocators and recipients of rewards and sanctions, evaluating one another based on their respective performances (Resh and Sabbagh, 2014). As spaces where educational services are directly experienced, schools provide students with the opportunity to establish a rational connection between the quality of these publicly funded services and the broader political system.

Research on political attitudes has examined the micro- and macro-level factors influencing political trust through distinct approaches. At the micro-level, extensive studies indicate that negative classroom experiences not only result in adverse student outcomes, such as absenteeism and aggression (Chory-Assad and Paulsel, 2004a; Horan et al., 2010), but also have a detrimental impact on political attitudes, including political trust (Abdelzadeh et al., 2015; Brezicha and Leroux, 2023; Ziemes et al., 2020). However, the majority of these student-level studies focus on single cases, with only a limited number offering comparative analyses, particularly among Nordic countries (Brezicha and Leroux, 2023).

At the macro level, research links a regime’s overall performance in delivering institutional outputs—such as fostering economic growth, reducing unemployment, and strengthening social protection—to levels of political trust (Mishler and Rose, 2005; van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017). While studies on young people have explored the impact of various macro-level factors on civic knowledge (Lin, 2014; Torney-Purta et al., 2004) and political participation (Hooghe and Dassonneville, 2013), there is limited empirical evidence on how these contextual factors shape students’ political trust in comparative context. The current study thus seeks to fill this gap in literature through asking the question: How does the quality of education at both the student and national levels influence political trust in Europe?

This study contributes to the literature on political trust through a multilevel analysis of data from Round 2 of the European Social Survey and World Bank data on GDP allocation to education for the same period. First, it expands the analysis beyond a narrow focus on fairness in performance or quality by incorporating distributive justice, procedural fairness, and functional effectiveness as key dimensions. Second, it demonstrates that students consider both procedural fairness and functional effectiveness when forming political trust. Third, amid ongoing reforms advocating for the privatization of public services, including education, this study highlights the significance of budgetary allocation for education at the country level as a potential macro-level determinant of political trust in Europe.

The next section examines the theoretical relationship between schooling quality and political trust. The third section describes the data and analytical approach, followed by the presentation of the main findings in the fourth section. The paper concludes with a summary and discussion of the key findings in the final section.

Theory and hypotheses

Political trust is commonly defined based on Easton’s concepts of diffuse and specific support (Easton, 1975). Diffuse support reflects citizens’ recognition and respect for core political institutions, independent of their performance, and is expressed through trust and legitimacy. In contrast, specific support refers to citizens’ evaluations of authorities and governmental bodies based on their daily performance, conveyed through satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Political trust differs from political legitimacy in that it represents a summary judgment that the political system—or its components—will continue to produce favorable policy outcomes without requiring constant scrutiny (Easton, 1975; Hetherington, 2007; Miller and Listhaug, 1990). It encompasses both cognitive and emotional attitudes, incorporating citizens’ knowledge, expectations, perceptions of risk, and interests related to political institutions. Political legitimacy, by contrast, pertains to citizens’ belief that existing political institutions are appropriate for society and that their authority should be respected and followed (Levi and Stoker, 2000; Lipset, 1960). Simply put, legitimacy relates to future behavioral orientations, whereas trust is tied to present affective orientations.

Micro-performance and political trust

Performance theory posits that citizens’ evaluations of public services (micro-performance) and the overall effectiveness of institutions (macro-performance) are key determinants of political trust (Mishler and Rose, 2001; Norris, 2011; van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017). Micro-performance refers to citizens’ assessments of various aspects of working of public authorities, including distributive justice, procedural fairness, and functional effectiveness (Jost and Kay, 2010; Lind and Tyler, 1988; McFarlin and Sweeney, 1992; Rothstein and Teorell, 2008; Tyler, 2000; Van Ryzin, 2011). Distributive justice pertains to the fair and impartial allocation of outcomes based on principles of equity, equality, or need, with the objective of fostering productivity, social harmony, and overall social welfare (Lind and Tyler, 1988).

Procedural fairness refers to the application of decision-making criteria in a manner that upholds fundamental rights and human dignity (Jost and Kay, 2010). It encompasses key elements such as representation or voice, accuracy, consistency, correctability, and neutrality or the absence of bias (Lind and Tyler, 1988). Functional effectiveness, in contrast, refers to the actual outcomes achieved, such as a reduction in crime rates or high academic performance in schools. Research in the field of policing and child protection systems has examined how these three dimensions of performance—distributive justice, procedural fairness, and functional effectiveness—shape institutional trust and legitimacy (Hassan, 2024; Lind and Tyler, 1988; Sunshine and Tyler, 2003). These performance assessments also extend to political trust (Marien and Werner, 2019). Yet, it remains relatively uncommon to explore how these three measures of performance collectively influence political trust among students (Abdelzadeh et al., 2015).

The first three hypotheses (H1–H3) are grounded in the micro-performance literature, which highlights the links between citizens’ perceptions of public services and regulatory institutions—such as the police, courts, and child protection systems—and students’ assessments of teaching quality in schools with political trust (Abdelzadeh et al., 2015; Bouckaert and Van de Walle, 2003; Hassan, 2024; Marien and Werner, 2019; Van Ryzin, 2011). When citizens perceive public authorities as impartial, fair, and effective in delivering expected outcomes, they are more likely to trust political institutions. Similarly, students who have positive experiences with school authorities tend to exhibit greater political trust. Moreover, fostering interactions between teachers and students not only strengthens political trust but also contributes to the development of social capital, which is essential for sustaining democratic regimes. These interactions, along with social learning experiences such as discussions, debates, and negotiations, play a crucial role in cultivating the social capital necessary for the success of democratic systems (Claes and Hooghe, 2017).

The classroom justice literature suggests that students respond rationally to their interactions with teachers, who serve as primary authority figures in the classroom. Positive interactions, such as seeking guidance and skill development, contribute to improved student outcomes (Chory-Assad and Paulsel, 2004a, 2004b; Horan et al., 2010; Kaufmann and Tatum, 2018; Tripp et al., 2019). Conversely, negative experiences, including victimization and discrimination, diminish students’ interest in politics (Ziemes et al., 2020). This body of research conceptualizes teaching quality through dimensions such as nondiscrimination, equality, equity, justice, fair assessment, and ethical teaching practices, which together fall under the broader categories of distributive, procedural, and instructional justice (Berti et al., 2010; Chory-Assad and Paulsel, 2004a, 2004b; Horan et al., 2010; Rasooli et al., 2019; Resh and Sabbagh, 2014).

In the existing literature, distributive justice refers to students’ perceptions of the fair allocation of outcomes, including grades, opportunities for grade improvement, teacher attention, and other rewards and consequences. Procedural justice concerns the application of appropriate procedures in the distribution of these grades. While teacher effectiveness, which reflects students’ perceptions of how well teachers impart essential knowledge, skills, and abilities, receives comparatively less attention in the classroom justice literature, it remains a crucial component of the micro-performance perspective (Bouckaert and Van de Walle, 2003; Van de Walle and Bouckaert, 2003). Applying this perspective to educational services suggests that students (1) distinguish between politics and educational services, (2) possess better information and knowledge about these services, (3) evaluate them based on teachers’ performance, and (4) establish a causal link between service performance and trust in political institutions.

Assessing the effectiveness of teachers and schools is more complex than evaluating resource distribution and procedural fairness. Effective schooling entails preparing students for the evolving demands of the labor market while equipping them with essential skills for tasks such as problem-solving, optimization, ensuring equal opportunities, and fostering socialization (Labaree, 1997; van de Werfhorst, 2014). However, determining whether teachers effectively fulfill these roles remains challenging due to shifting labor market requirements and changing societal values (van de Werfhorst, 2014). Despite these measurement difficulties, evaluating school effectiveness remains essential and can be achieved through a holistic approach to student development, including providing clear explanations, fostering critical thinking, and offering student support (Chory, 2007; Chory-Assad and Paulsel, 2004a; Galbraith et al., 2012).

Building on the micro-performance literature, it is expected that the quality of interactions between students and teachers will shape students’ perceptions of distributive justice, procedural fairness, and functional effectiveness, which in turn will influence their political trust. Consequently, higher-quality individual-level education is anticipated to enhance political trust. Specifically:

H1: Students' perceptions of distributive injustice by teachers will be negatively associated with their level of political trust.

H2: Students' perceptions of procedural fairness demonstrated by their teachers will be positively associated with their political trust.

H3: Students' perceptions of their teachers' effectiveness will be positively correlated with their political trust.

Macro-performance and political trust

Researchers generally concur that political trust depends on a country’s overall performance in ensuring good governance and addressing societal challenges. Citizens’ political trust is shaped by their assessments of government performance relative to their expectations. Rational citizens are more likely to trust a regime that consistently upholds good governance through transparency, accountability, adherence to the rule of law, economic growth, employment, and the reduction of corruption and crime. Extensive research has explored the effects of governance, corruption, poverty, economic growth, inflation, and unemployment on political trust (Kroknes et al., 2015; Norris, 2011; Obydenkova and Arpino, 2018; van der Meer, 2010; van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017; Van Erkel and Van Der Meer, 2016; Zmerli and Castillo, 2015). Accordingly, this study posits:

H4: The state's capacity to efficiently provide educational services will be positively associated with students' levels of political trust.

Data and analysis

This study utilizes multilevel data constructed from Round 2 of the European Social Survey (ESS2)1 and World Bank data2 to examine the relationship between student’s perceptions of quality of schooling and political trust. ESS2 surveyed individuals aged 15 and above in 25 countries between September 2004 and July 2006. Data on student-level political trust and various control variables were obtained from the core module, while quality of schooling variables were extracted from the rotating module titled Family, Work and Wellbeing. Students were the primary respondents providing information about the quality of education in their institutions. It is important to note that the family work module was not rotated in France, and measures of distributive justice contained 96% missing values in Slovenia. Additionally, the World Bank data did not include information on the percentage of GDP allocated to education for Turkey, a country-level measure of schooling quality. The student-level dataset comprised 3,743 observations, supplemented by 22 country-level observations on quality of schooling—measured as the percentage of GDP allocated to education—resulting in a final dataset suitable for multilevel analysis. The countries included in the analysis are Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, and Ukraine.

Political trust

Political trust, the dependent variable, was measured using the ESS2 question asking respondents: “Please tell me, on a scale of 0–10, how much you personally trust each of the institutions I read out. Zero means you do not trust an institution at all, and 10 means you have complete trust.” The listed institutions included the country’s parliament (trstprl), political parties (trstprt), politicians (trstplt), the police (trstplc), and the legal system (trstlgl). Trust in these five institutions was aggregated into an average index of political trust across the 22 countries, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.77 in the Netherlands to 0.91 in the Czech Republic. This measurement aligns with previous research (Hakhverdian and Mayne, 2012; Hooghe et al., 2017). See Appendix A for a detailed reliability analysis of political trust and its associated variables.

Quality of schooling

The concept of quality is often used interchangeably with terms such as efficiency, effectiveness, and the impartial implementation of laws (Rothstein and Teorell, 2008; UNICEF, 2000), making it particularly challenging to operationalize the quality of schooling. Nonetheless, this study follows established literature on the subjective and objective quality of democracy (Fuchs and Roller, 2018) to develop measures of subjective and objective schooling quality, the two independent variables.

Building on previous research on public services (Hassan, 2024; Huq et al., 2017; Sunshine and Tyler, 2003; Van Ryzin, 2011), subjective schooling quality is assessed through students’ perceptions and experiences of three dimensions of the school environment and processes: distributive justice, procedural fairness, and functional effectiveness. These variables were operationalized using four out of 13 items from the Family, Work and Wellbeing module. While additional factors, such as student interactions with peers, workload, and the quality of the physical environment, could provide further insights, they were excluded from the analysis. This exclusion was inevitable due to the need for a different theoretical framework and the potential challenges in analysis and comparability resulting from variations in educational systems. The four retained items align with those previously used in the literature on quality of education (Chory-Assad and Paulsel, 2004b; Hooghe et al., 2015; Smith and Gorard, 2006).

Distributive justice refers to the fair and impartial allocation of educational resources and outcomes—for instance, grades—based on merit, irrespective of students’ gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, or religion. While scholars often employ multi-item indices to measure distributive justice (Chory-Assad and Paulsel, 2004b; Fields et al., 2000; Wolfe et al., 2016), this study utilizes a single-item proxy: “Would you describe yourself as being a member of a group that is discriminated against in this country (dscrgrp)?” Responses were coded as 1 (yes) and 2 (no). This measure is comparable to existing indicators of distributive justice used in studies on attitudes toward legal authorities (Sunshine and Tyler, 2003; Tyler and Huo, 2002). Given that students spend a significant portion of their time in educational institutions, their responses are likely to reflect their school experiences, making this measure a meaningful proxy for assessing the administration of justice within educational settings.

Procedural justice was assessed using the statement: “There are teachers who treat me badly or unfairly (tchtruf).” Responses were recorded on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree), with higher scores indicating greater procedural fairness in teachers’ behavior. Functional effectiveness was measured using global indicators that encompassed overall teacher evaluation and instructional justice, including aspects such as providing clear explanations, fostering critical thinking, and supporting students (Chory, 2007; Chory-Assad and Paulsel, 2004a; Galbraith et al., 2012). Although the Family, Work, and Wellbeing module did not contain comprehensive global measures of teacher effectiveness, this study relied on three items assessing the instructional dimension. The first two items asked respondents to rate, on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree), the extent to which: “Teachers are interested in the students (tchints),” and “When I criticize something, my teachers listen to what I have to say (tchlcrt).” The third item measured perceived teacher support: “Do you feel you get the help you need from the teachers about your course(s) (tchlp)?” Responses were recorded on a 4-point scale (1 = always, 2 = often, 3 = not very often, 4 = never). After reverse coding these items, a reliability analysis was conducted, demonstrating that they reliably measured the underlying construct in most countries, with some exceptions (e.g., Hungary: alpha = 0.45; see Appendix A). As a result, these items were aggregated into an average index ranging from 1 (least effective) to 5 (most effective).

The subjective quality of schooling, as reflected in students’ perceptions and experiences, can provide valuable comparative insights when complemented by objective measures. However, identifying valid and reliable indicators of objective schooling quality presents a significant challenge. Objective quality can be assessed through inputs such as facilities, teaching materials, and the presence of qualified teachers (Grisay and Mählck, 1991). Nevertheless, measuring these factors accurately is complex. For instance, one school may employ a larger number of highly qualified teachers than another, yet those teachers may be less motivated. Similarly, a school with fewer facilities may utilize them more efficiently than one with greater resources (Carron and Châu, 1981).

Given that institutional quality can be evaluated through indicators such as the successful provision of essential public goods and effective spending (La Porta et al., 1999, p. 223), this study used the World Bank’s data to measure country-level quality of schooling using the percentage of national gross domestic product (GDP) allocated to education. To reduce the impact of short-term fluctuations, an average for the years 2004, 2005, and 2006 was calculated. The lack of available data presents challenges in selecting appropriate direct measures of the quality of schooling at the national level, such as student-teacher ratios, the quality of teaching content, infrastructure, and facilities. While this measure does not precisely capture educational quality, it serves as a useful proxy for illustrating government commitment to investing in teachers, students, and educational infrastructure. Additionally, it provides a basis for comparing the prioritization of education relative to national economic capacity, facilitating cross-country analyses for researchers and policymakers.

Control variables

The analysis incorporated several student-level and country-level control variables (Goubin and Hooghe, 2020; van der Meer, 2010; Zmerli and Newton, 2008). Student-level controls included gender, age, study level, citizenship, satisfaction with the economy, political interest, and left–right political orientation. Additionally, social capital was included as a student-level control variable, measured as an average index of interpersonal trust, helpfulness, and fairness. At the country level, a history of communism was included as a control variable. For details on the construction and descriptive statistics of these variables (see Appendices A–D).

Analytical approach

The analysis begins with a descriptive overview, offering a comprehensive examination of the distribution of political trust and its associated factors. This is followed by a summary of correlation statistics. The study then applies multilevel analysis, a widely used method for hierarchical data in which individual-level observations are nested within country-level data (Snijders and Bosker, 1999).

Findings

Cross-national differences in political trust

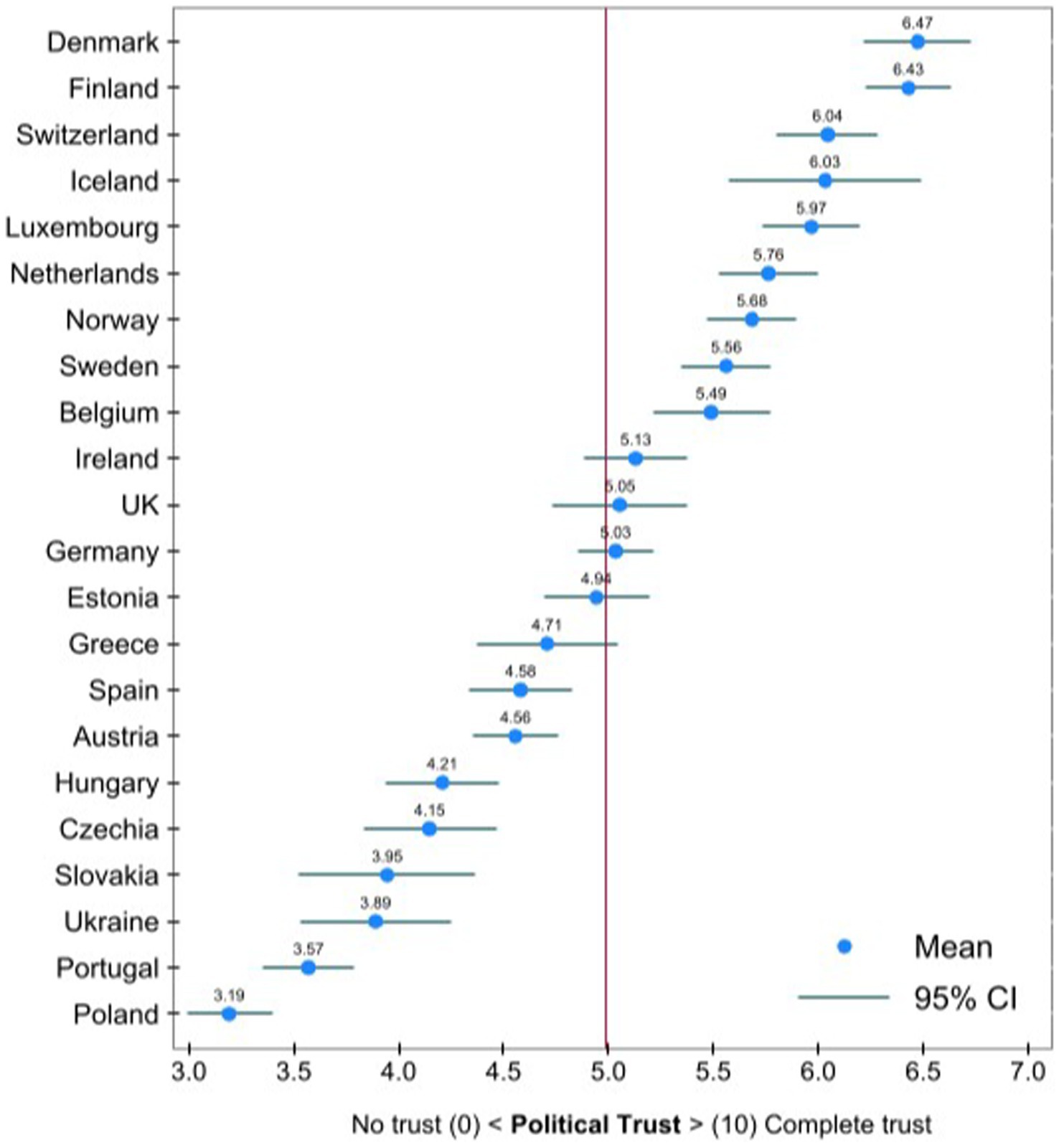

Figure 1 displays the mean political trust among students across 22 European countries, with confidence intervals (95% CI) to illustrate variability (see Appendix B). The results show notable differences in political trust between countries, with Denmark reporting the highest mean (6.47) and Poland the lowest (3.19). The vertical red line represents the overall mean across all countries (4.99), dividing countries with above- and below-average levels of political trust. Countries such as Finland, Switzerland, and Iceland exhibit high trust levels, while Portugal, Ukraine, and Slovakia fall on the lower end. The confidence intervals highlight the degree of variation within each country, indicating that political trust is not uniformly distributed among students.

Figure 1. Mean political trust, by country. Data from ESS2 (2004). Vertical line shows the overall mean across all countries (4.99). See Appendix B for details.

Appendix B provides an overview of the distribution of predictors and control variables at both the student and country levels. Among students, British respondents reported the highest percentage of perceived discrimination by teachers (15.9%), representing distributive justice, while Czech students reported the lowest (1.4%). In terms of procedural justice, Danish students had the highest perception (4.04), whereas Hungarian students had the lowest (3.03). Regarding functional effectiveness, Icelandic schools were rated as the most effective by students (3.95), while Slovakian schools were perceived as the least effective (3.14). Additionally, government spending on education—a proxy for country-level quality schooling—varied significantly, with Denmark allocating the highest percentage of GDP to education (8.01%) and Greece the lowest (3.76%). All continuous variables were centered at the country level for student-level analysis and at EU mean for country-level analysis to facilitate interpretation and comparison. Finally, correlation analysis in Appendix E indicates that distributive justice (b = 0.06, p ≤ 0.001), procedural fairness (b = 0.09, p ≤ 0.001), and functional effectiveness (b = 0.14, p ≤ 0.001) at the school level, along with percentage of GDP to education were significantly associated with political trust (b = 0.21, p ≤ 0.001).

Effects of quality of schooling on political trust

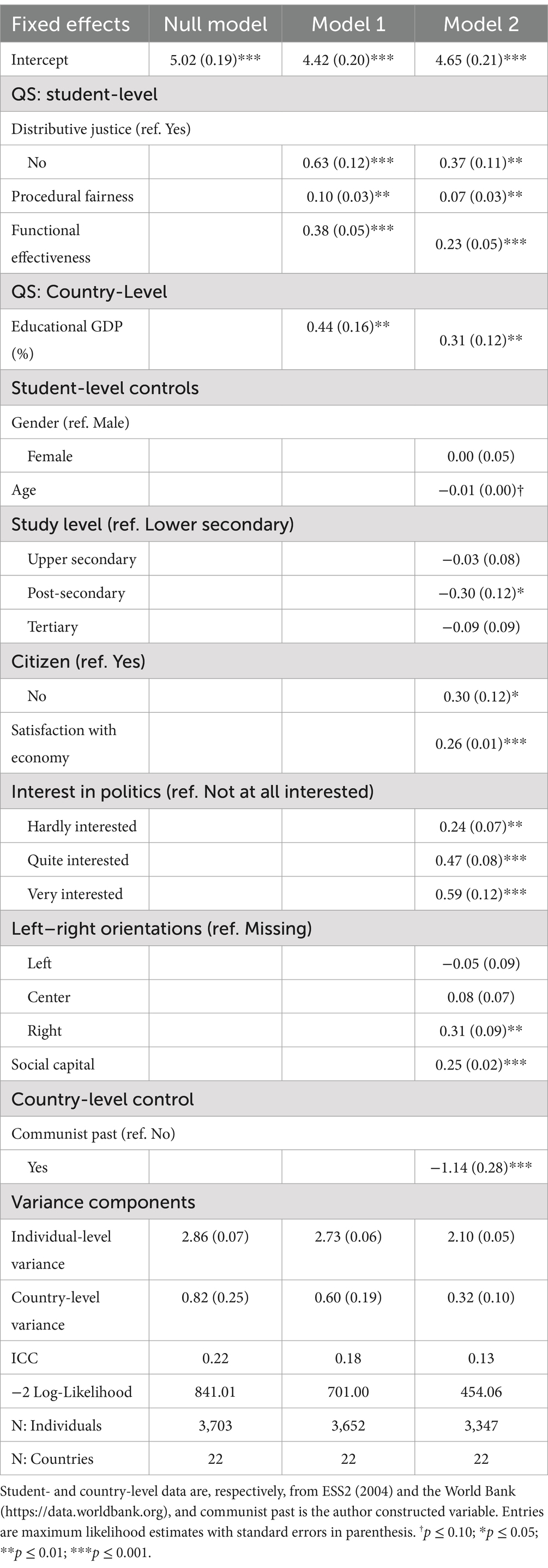

The Null Model in Table 1 presents the results of the intercept-only model, which estimates country-level variance using ANOVA statistics and calculates the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). The ANOVA results indicate that political trust has a mean of 5.02 and a standard deviation of 0.19. The intercepts, representing the grand means of political trust, show significant variation across countries. The ICC reveals that 22% of the total variation in political trust is attributable to country-level differences. This variance decreases by 4 percentage points after including variables related to the quality of schooling (Model 1) and by another 5 percentage points when additional control variables are included (Model 2). The −2 log-likelihood statistics indicate that the nested models are statistically significant compared to their non-nested counterparts. Notably, one additional degree of freedom corresponds to a chi-square distribution of 6.64 at a significance level of 0.01. These findings confirm the suitability of multilevel modeling for this analysis.

Table 1 presents the results of two multilevel models. Model 1 includes only the predictor variables, while Model 2 incorporates additional controls for a more comprehensive analysis. The findings indicate that both subjective and objective measures of the quality of schooling significantly predict students’ political trust in European countries. These effects remain statistically significant across varying model specifications, suggesting that political trust among students is determined by both subjective perceptions and objective indicators of quality of schooling. The estimates discussed below are derived from the fuller model.

In Model 2, several key findings emerge. Students who perceive no discrimination in their schools, representing distributive justice, are 0.37 (p ≤ 0.01) times more likely to trust political institutions than those who experience discrimination. A one standard deviation increase in the perception of procedural fairness in teachers is associated with a 0.07 (p ≤ 0.01) unit increase in students’ political trust. Similarly, students’ political trust increases by 0.23 (p ≤ 0.001) points for each standard deviation increase in teachers’ perceived functional effectiveness. At the country level, a one standard deviation increase in the objective quality of schooling, measured by GDP (%) expenditure on education, corresponds to a 0.31 (p ≤ 0.01) unit rise in political trust. These results suggest that while students’ perceptions and experiences of schooling significantly influence political trust, investment in education plays an even greater role. Overall, the findings strongly support the hypotheses that political trust is shaped by distributive justice (H1), procedural fairness (H2), and functional effectiveness (H3) at the student level, as well as by country-level investment in education (H4).

Model 2 also incorporates student- and country-level demographic and control variables. The key findings are as follows: gender does not show a significant association with political trust. Age and post-secondary student status are negatively associated with political trust, while non-citizen status, satisfaction with the economy, and social capital are positively associated with political trust. Interest in politics is also positively correlated with political trust, with those who are very interested in politics exhibiting higher levels of trust compared to those who are only somewhat or hardly interested. Additionally, students identified as center on the left–right political spectrum are more likely to trust political institutions than those who identify as left (insignificant) or right. At the country level, students in post-communist states are less likely to express political trust compared to those in non-communist societies.

Conclusion

This study aimed to examine the relationship between the quality of schooling and political trust from both micro and macro perspectives. It drew on micro-performance and classroom justice literature to theoretically establish the connections between students’ perceptions of distributive justice, procedural fairness, and functional effectiveness—three student-level dimensions of the subjective quality of schooling—and political trust (H1–H3). Additionally, based on macro-performance literature, the study posited that the objective quality of schooling is positively associated with political trust (H4). These hypotheses were tested using multilevel analysis of data from Round 2 of the European Social Survey (ESS2), which assessed students’ subjective perceptions of schooling quality, alongside the percentage of GDP spent on education as a proxy for the objective quality of schooling.

The findings of this study strongly support the notion that the quality of schooling is a significant determinant of students’ levels of political trust in Europe. More precisely, the analysis revealed that students’ perceptions of distributive justice and procedural fairness positively influenced their political trust (H1–H2). These results align with prior research on the emotional and behavioral consequences of classroom injustice, including feelings of anger and hostility toward instructors, engagement in deceptive or vengeful behaviors, academic disengagement, and accusations against teachers (Chory-Assad and Paulsel, 2004a, 2004b; Horan et al., 2010; Kaufmann and Tatum, 2018; Tripp et al., 2019).

Furthermore, as expected, students’ perceptions of teachers’ functional effectiveness were positively associated with political trust (H3). This indicates that political trust increases when students perceive that teachers care about them, provide assistance, and are receptive to criticism. This finding aligns with prior research highlighting the positive impact of an open classroom climate on political trust (Claes et al., 2012). Finally, the results indicate that higher educational spending as a percentage of GDP—a country-level measure of quality of schooling—has a direct and positive impact on political trust. This finding supports the fourth hypothesis (H4) and is consistent with existing macro-performance literature, which examines the influence of various institutional factors, such as macroeconomic performance, the rule of law, and corruption, on political trust (Khan, 2016; Mishler and Rose, 2001; Norris, 2011; van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017).

These findings underscore the relevance of both micro- and macro-performance theories (Bouckaert and Van de Walle, 2003; Mishler and Rose, 2001; Norris, 2011; Van de Walle and Bouckaert, 2003). When applied to the assessment of schools, these theories suggest that students can differentiate between educational services and political affairs and, in a rational manner, hold political institutions accountable for the quality of teaching services they receive and experience in their educational institutions. In other words, students favor an egalitarian educational system that benefits all learners equally; they expect teachers to equip them with the essential skills needed for personal and professional success, which, in turn, contributes to their political trust (Smith and Gorard, 2006). Enhancing the quality of education is a critical objective, and this study highlights the need to prioritize it within government human development strategies. The findings suggest that improving education quality can act as a catalyst for strengthening political trust among students, aligning with the principles of emerging performance theories.

This study is not without limitations. Previous research in organizational justice (Beugre and Baron, 2001; Siu et al., 2013), policing (Sunshine and Tyler, 2003), and classroom justice has developed well-established, multidimensional operational definitions that distinguish between distributive justice and procedural fairness (Chory-Assad and Paulsel, 2004b). These frameworks highlight the importance of employing multi-item scales to enhance construct validity and reliability. However, this study relied on single-item proxy measures for distributive justice (perceived discrimination) and procedural fairness (perceived good or bad treatment by teachers), diverging from the comprehensive measurement approaches commonly used in prior research. This reliance on single-item measures was unavoidable, as ESS2 did not provide additional question batteries necessary to construct multidimensional measures of distributive justice and procedural fairness.

An additional limitation concerns the identification of alternative or direct country-level measures of schooling quality, which constrained the use of percentage GDP spent on education as a proxy for country-level schooling quality. While the inclusion of both subjective and objective measures of schooling quality provides valuable insights, it also entails certain trade-offs. At the subjective level, these measures may not fully capture the complexity and multidimensional nature of the underlying concepts, potentially leading to measurement errors by reflecting generalized perceptions of distributive justice and procedural fairness rather than concrete and complex experiences with educational authorities. Similarly, the percentage of GDP spent on education may not accurately represent schooling quality, as factors such as resource allocation efficiency, teacher effectiveness, and curriculum rigor also contribute to educational outcomes. Moreover, this study relied on a relatively small sample of 3,743 observations from 22 countries, which may have affected the precision of parameter estimates. Taken together, these limitations suggest that caution is warranted when generalizing the findings to broader populations or drawing comparative insights.

Future research in this area should aim to address the limitations identified in this study. Specifically, researchers should develop more comprehensive measures to assess students’ perceptions of distributive justice and procedural fairness. In examining functional effectiveness, employing more direct questions that explicitly evaluate whether courses and teachers equip students with the necessary skills and knowledge for future roles would enhance measurement accuracy. Furthermore, collecting data from larger, more representative student samples could provide deeper insights into the relationship between schooling quality and political trust. Lastly, as this study focused on schools in Europe, future research should validate these findings in comparative and cross-cultural contexts to better understand how schooling quality influences political trust across different educational and political systems.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ and https://data.worldbank.org/.

Author contributions

BH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on my doctoral thesis, written and defended under the supervision of Prof. Nicolas Sauger at the Centre for European Studies and Comparative Politics, Sciences Po Paris, in September 2021. I am grateful to Prof. Nicolas Sauger, my doctoral committee, participants at the 2020 ECPR Joint Sessions, and the two reviewers for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1389088/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Abdelzadeh, A., Zetterberg, P., and Ekman, J. (2015). Procedural fairness and political trust among young people: evidence from a panel study on Swedish high school students. Acta Politica 50, 253–278. doi: 10.1057/ap.2014.22

Berti, C., Molinari, L., and Speltini, G. (2010). Classroom justice and psychological engagement: students’ and teachers’ representations. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 13, 541–556. doi: 10.1007/s11218-010-9128-9

Beugre, C. D., and Baron, R. A. (2001). Perceptions of systemic justice: the effects of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 31, 324–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb00199.x

Bouckaert, G., and Van de Walle, S. (2003). “Quality of public service delivery and Trust in Government” in Governing networks: EGPA yearbook. ed. A. Salminen (Amsterdam: IOS Press), 299–318.

Brezicha, K. F., and Leroux, A. J. (2023). Examining the association between feeling excluded at school and political trust in four Nordic countries. Educ. Citizenship Soc. Justice 18, 364–381. doi: 10.1177/17461979221097362

Carron, G., and Châu, T. N. (1981). Reduction of regional disparities: The rôle of educational planning. Paris: UNESCO.

Chory, R. M. (2007). Enhancing student perceptions of fairness: the relationship between instructor credibility and classroom justice. Commun. Educ. 56, 89–105. doi: 10.1080/03634520600994300

Chory-Assad, R. M., and Paulsel, M. L. (2004a). Antisocial classroom communication: instructor influence and interactional justice as predictors of student aggression. Commun. Q. 52, 98–114. doi: 10.1080/01463370409370184

Chory-Assad, R. M., and Paulsel, M. L. (2004b). Classroom justice: student aggression and resistance as reactions to perceived unfairness. Commun. Educ. 53, 253–273. doi: 10.1080/0363452042000265189

Claes, E., and Hooghe, M. (2017). The effect of political science education on political trust and interest: results from a 5-year panel study. J. Polit. Sci. Educ. 13, 33–45. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2016.1171153

Claes, E., Hooghe, M., and Marien, S. (2012). A two-year panel study among Belgian late adolescents on the impact of school environment characteristics on political trust. Int. J. Pub. Opin. Res. 24, 208–224. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edr031

Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 5, 435–457. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008309

Fields, D., Pang, M., and Chiu, C. (2000). Distributive and procedural justice as predictors of employee outcomes in Hong Kong. J. Organ. Behav. 21, 547–562. doi: 10.1002/1099-1379(200008)21:5<547::AID-JOB41>3.0.CO;2-I

Fuchs, D., and Roller, E. (2018). Conceptualizing and measuring the quality of democracy: the citizens’ perspective. Politics Gov. 6, 22–32. doi: 10.17645/pag.v6i1.1188

Galbraith, C. S., Merrill, G. B., and Kline, D. M. (2012). Are student evaluations of teaching effectiveness valid for measuring student learning outcomes in business related classes? A neural network and Bayesian analyses. Res. High. Educ. 53, 353–374. doi: 10.1007/s11162-011-9229-0

Goubin, S., and Hooghe, M. (2020). The effect of inequality on the relation between socioeconomic stratification and political trust in europe. Soc. Justice Res 33, 219–247. doi: 10.1007/s11211-020-00350-z

Grisay, A., and Mählck, L. (1991). The quality of education in developing countries: A review of some research studies and policy documents. Paris: UNESCO.

Hakhverdian, A., and Mayne, Q. (2012). Institutional trust, education, and corruption: a Micro-macro interactive approach. J. Polit. 74, 739–750. doi: 10.1017/S0022381612000412

Hassan, B. (2024). Performance and trust in child protection systems: a comparative analysis of England and Norway. J. Soc. Policy 1–20, 1–20. doi: 10.1017/S0047279424000114

Henn, M., Weinstein, M., and Wring, D. (2002). A generation apart? Youth and political participation in Britain. Br. J. Polit. Int. Rel. 4, 167–192. doi: 10.1111/1467-856X.t01-1-00001

Hetherington, M. J. (2007). Why trust matters: Declining political trust and the demise of American liberalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hooghe, M., and Dassonneville, R. (2013). Voters and candidates of the future: the intention of electoral participation among adolescents in 22 European countries. Young 21, 1–28. doi: 10.1177/1103308812467664

Hooghe, M., Dassonneville, R., and Marien, S. (2015). The impact of education on the development of political trust: results from a five-year panel study among late adolescents and young adults in Belgium. Political Studies 63, 123–141. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12102

Hooghe, M., Marien, S., and Oser, J. (2017). Great expectations: the effect of democratic ideals on political trust in European democracies. Contemp. Polit. 23, 214–230. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2016.1210875

Horan, S. M., Chory, R. M., and Goodboy, A. K. (2010). Understanding students’ classroom justice experiences and responses. Commun. Educ. 59, 453–474. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2010.487282

Huq, A. Z., Jackson, J., and Trinkner, R. (2017). Legitimating practices: revisiting the predicates of police legitimacy. Br. J. Criminol. 22:azw037. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azw037

Jost, J. T., and Kay, A. C. (2010). “Social justice: history, theory, and research” in Handbook of social psychology. eds. S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, and G. Lindzey. 1st ed (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons).

Kaufmann, R., and Tatum, N. T. (2018). Examining direct and indirect effects of classroom procedural justice on online students’ willingness to talk. Distance Educ. 39, 373–389. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2018.1476838

Khan, H. A. (2016). The linkage between political trust and the quality of government: an analysis. Int. J. Public Adm. 39, 665–675. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2015.1068329

Kiess, J. (2022). Learning by doing: the impact of experiencing democracy in education on political trust and participation. Politics 42, 75–94. doi: 10.1177/0263395721990287

Kołczyńska, M. (2020). Democratic values, education, and political trust. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 61, 3–26. doi: 10.1177/0020715220909881

Kroknes, V. F., Jakobsen, T. G., and Grønning, L.-M. (2015). Economic performance and political trust: the impact of the financial crisis on European citizens. Eur. Soc. 17, 700–723. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2015.1124902

Labaree, D. F. (1997). Public goods, private goods: the American struggle over educational goals. Am. Educ. Res. J. 34, 39–81. doi: 10.3102/00028312034001039

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., and Vishny, R. (1999). The quality of government. J. Law. Econ. org. 15, 222–279. doi: 10.1093/jleo/15.1.222

Levi, M., and Stoker, L. (2000). Political trust and trustworthiness. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 3, 475–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.475

Levy, B. L. M. (2013). An empirical exploration of factors related to adolescents’ political efficacy. Educ. Psychol. 33, 357–390. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2013.772774

Lin, A. R. (2014). Examining students’ perception of classroom openness as a predictor of civic knowledge: A cross-national analysis of 38 countries. Appl. Develop. Sci. 18, 17–30. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2014.864204

Lipset, S. M. (1960). Political man: The social bases of politics. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: The dilemmas of the individual in public service: The dilemmas of the individual in public service. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Marien, S., and Werner, H. (2019). Fair treatment, fair play? The relationship between fair treatment perceptions, political trust and compliant and cooperative attitudes cross-nationally. Eur J Polit Res 58, 72–95. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12271

Maurissen, L. (2020). Political efficacy and interest as mediators of expected political participation among Belgian adolescents. Appl. Dev. Sci. 24, 339–353. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2018.1507744

McFarlin, D. B., and Sweeney, P. D. (1992). Distributive and procedural justice as predictors of satisfaction with personal and organizational outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 35, 626–637. doi: 10.2307/256489

Miller, A. H., and Listhaug, O. (1990). Political parties and confidence in government: a comparison of Norway, Sweden and the United States. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 20, 357–386. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400005883

Mishler, W., and Rose, R. (2001). What are the origins of political trust?: testing institutional and cultural theories in post-communist societies. Comp. Pol. Stud. 34, 30–62. doi: 10.1177/0010414001034001002

Mishler, W., and Rose, R. (2005). What are the political consequences of trust?: a test of cultural and institutional theories in Russia. Comp. Pol. Stud. 38, 1050–1078. doi: 10.1177/0010414005278419

Monsiváis-Carrillo, A., and Cantú Ramos, G. (2022). Education, democratic governance, and satisfaction with democracy: multilevel evidence from Latin America. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 43, 662–679. doi: 10.1177/0192512120952878

Norris, P. (2011). “Does democratic satisfaction reflect regime performance?” in How democracy works. eds. M. Rosema, B. Denters, and K. Aarts (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press), 115–136.

Obydenkova, A. V., and Arpino, B. (2018). Corruption and trust in the european union and national institutions: changes over the great recession across european states. J. Common Mark. Stud. 56, 594–611. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12646

Rasooli, A., Zandi, H., and DeLuca, C. (2019). Conceptualising fairness in classroom assessment: exploring the value of organisational justice theory. Assessment Educ. Principles Policy Prac. 26, 584–611. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2019.1593105

Resh, N., and Sabbagh, C. (2014). Sense of justice in school and civic attitudes. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 17, 51–72. doi: 10.1007/s11218-013-9240-8

Rothstein, B., and Teorell, J. (2008). What is quality of government? A theory of impartial government institutions. Governance 21, 165–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2008.00391.x

Siu, N. Y.-M., Zhang, T. J.-F., and Yau, C.-Y. J. (2013). The roles of justice and customer satisfaction in customer retention: a lesson from service recovery. J. Bus. Ethics 114, 675–686. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1713-3

Smith, E., and Gorard, S. (2006). Pupils’ views on equity in schools. Compare J. Comparative Int. Educ. 36, 41–56. doi: 10.1080/03057920500382465

Snijders, T. A. B., and Bosker, R. J. (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: SAGE Publications.

Sunshine, J., and Tyler, T. R. (2003). The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law Soc. Rev. 37, 513–547. doi: 10.1111/1540-5893.3703002

Torney-Purta, J., Henry Barber, C., and Richardson, W. K. (2004). Trust in government-related institutions and political engagement among adolescents in six countries. Acta Politica 39, 380–406. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500080

Tripp, T. M., Jiang, L., Olson, K., and Graso, M. (2019). The fair process effect in the classroom: reducing the influence of grades on student evaluations of teachers. J. Mark. Educ. 41, 173–184. doi: 10.1177/0273475318772618

Tyler, T. R. (2000). Social justice: outcome and procedure. Int. J. Psychol. 35, 117–125. doi: 10.1080/002075900399411

Tyler, T. R., and Huo, Y. J. (2002). Trust in the law: Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

UNICEF (2000). Defining quality in education. Working Paper Series. Education Section Programme Division. Paris: UNICEF.

Van de Walle, S., and Bouckaert, G. (2003). Public service performance and trust in government: The problem of causality. Int. J. Public Adm. 26, 891–913. doi: 10.1081/PAD-120019352

van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2014). Changing societies and four tasks of schooling: challenges for strongly differentiated educational systems. Int. Rev. Educ. 60, 123–144. doi: 10.1007/s11159-014-9410-8

van der Meer, T. (2010). In what we trust? A multi-level study into trust in parliament as an evaluation of state characteristics. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 76, 517–536. doi: 10.1177/0020852310372450

van der Meer, T., and Hakhverdian, A. (2017). Political trust as the evaluation of process and performance: a cross-National Study of 42 European countries. Politic. Stu. 65, 81–102. doi: 10.1177/0032321715607514

van Elsas, E. (2015). Political trust as a rational attitude: a comparison of the nature of political trust across different levels of education. Polit. Stu. 63, 1158–1178. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12148

Van Erkel, P. F. A., and Van Der Meer, T. W. G. (2016). Macroeconomic performance, political trust and the great recession: a multilevel analysis of the effects of within-country fluctuations in macroeconomic performance on political trust in 15 EU countries, 1999–2011. Eur J Polit Res 55, 177–197. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12115

Van Ryzin, G. G. (2011). Outcomes, process, and trust of civil servants. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 21, 745–760. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muq092

Wolfe, S. E., Nix, J., Kaminski, R., and Rojek, J. (2016). Is the effect of procedural justice on police legitimacy invariant? Testing the generality of procedural justice and competing antecedents of legitimacy. J. Quant. Criminol. 32, 253–282. doi: 10.1007/s10940-015-9263-8

Ziemes, J. F., Hahn-Laudenberg, K., and Abs, H. J. (2020). The impact of schooling on trust in political institutions – differences arising from students’ immigration backgrounds. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 26:100429. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100429

Zmerli, S., and Castillo, J. C. (2015). Income inequality, distributive fairness and political trust in Latin America. Soc. Sci. Res. 52, 179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.02.003

Keywords: political trust, quality of schooling, micro-performance, macro-performance, multilevel analysis

Citation: Hassan B (2025) Quality of schooling and political trust among students. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1389088. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1389088

Edited by:

Arnstein Aassve, Bocconi University, ItalyReviewed by:

Rany Sam, National University of Battambang, CambodiaYasin Kutuk, Gebze Technical University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Hassan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bilal Hassan, YmlsYWwuaGFzc2FuQHVpYi5ubw==

Bilal Hassan

Bilal Hassan