- 1Institute for Social Change and Sustainability, WU Wien, Vienna, Austria

- 2Institute of Political Science, Technical University of Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany

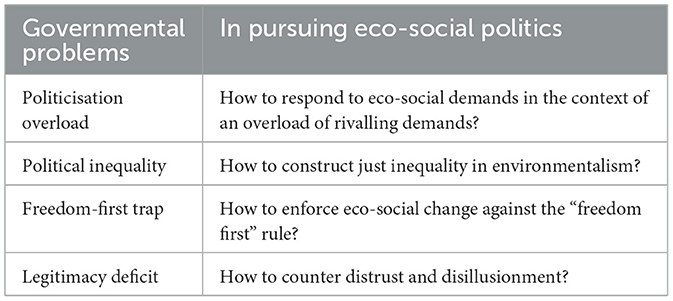

The phenomenon of ungovernability is by no means new and had already been described 50 years ago in the literature, but awareness of its importance has only recently been reawakened. From that starting point, this article develops a conceptual scheme of the problems governments are currently facing in their efforts to address eco-social issues, namely politicisation overload, political inequality, the “freedom-first trap”, and a structural legitimacy deficit. The heuristic potential of this scheme is then illustrated by way of the debates on the Buildings Energy Act in Germany. Given the inability of liberalism as a political paradigm to solve these problems, this article offers initial suggestions as to whether republicanism, as an alternative paradigm for environmental politics, can respond to the structural challenges of governing.

1 Introduction

In recent years, researchers and policymakers have increasingly recognised the close interconnections between environmental and social issues. Strategies such as the European Green Deal and instruments such as the European Union's Just Transition Mechanism and the Social Climate Fund reflect this development. Against this backdrop, the term eco-social policy has emerged to describe “public policies explicitly pursuing both environmental and social policy goals in an integrated way” (Mandelli, 2022, p. 340). Under this conceptual umbrella, a still nascent field of research is taking shape (Bohnenberger, 2023; Cotta, 2024). It examines the social impacts of environmental policies (Kortetmäki and Järvelä, 2021; Markkanen and Anger-Kraavi, 2019; McDowall et al., 2023; Nullmeier, 2024), describes and analyses the design, internal dynamics, and implementation of existing eco-social instruments (Im et al., 2024; Klüh et al., 2024; Kyriazi and Miró, 2022; McCauley et al., 2023; Sabato and Mandelli, 2024), and constructs normative frameworks for future policy design under the banner of sustainable welfare (Fritz and Lee, 2023; Gough, 2017, 2022; Koch, 2022). While much of this work highlights the renewed centrality of the state (Bonvin and Laruffa, 2022; Koch, 2022; Kortetmäki and Huttunen, 2022), a systematic exploration of the problems of governing within eco-social politics is so far lacking.

Such an analysis would be advantageous, however, as governments are increasingly caught between ever-increasing eco-social challenges and a turbulent politicisation, while their own capacities are shrinking. Indicators for this politicisation are the global increase in political protest since the financial crisis (Ortiz et al., 2022), the shortening period of time in which governing parties and politicians enjoy social support after being elected to power, the contestation of an increasing number of societal matters, and the challenge of a hitherto unchallenged (neo)liberalism. At the same time, governments are struggling with diminished capabilities amid a worsening economic outlook, growing geopolitical conflict, and perpetual polycrises. Although this amplifies demands for public problem-solving, there is a significant decline in confidence regarding the ability of government institutions to satisfy these demands (Forsa, 2024; OECD, 2024). This pincer movement of increased demands and reduced capabilities for effectively exercising political authority makes governing a difficult task today. Taking this into account, a stronger theoretical focus on problems of governing in the field of eco-social politics itself is needed (see Mann and Wainwright, 2018), not least because of the worsening ecological problems (Richardson et al., 2023) and intensifying social and political disintegration (Turchin, 2023).

This article, therefore, focuses on the macro-structural problems of governing today. Below, we will refer to these problems as governmental problems or, synonymously, problems of governing. We define governing as the process of making collectively binding decisions on practical norms and material and immaterial values by public officials in a legitimate and effective manner to solve public issues.

Against this backdrop, our article offers a conceptual scheme for identifying governmental problems of eco-social politics in times of (neo)liberal exhaustion. The second section uses the themes raised in the literature on ungovernability as a basis for a deeper inquiry of four problems of governing. In the third section, we illustrate the heuristic value of this conceptional scheme by analysing the debates surrounding the Buildings Energy Act in Germany between 2020 and 2025. In the fourth section, we then explore the potential of green republicanism for dealing with the challenges we have outlined. In the concluding section, we set out the key questions emerging from our analysis and suggest directions for further research.

2 Ungovernability reconsidered: governmental problems in eco-social politics

The literature on (un-)governability long ago identified a simultaneity: increased demands for effectively exercised political authority on the one hand, and reduced capacities to do so on the other. Triggered by the incipient “participatory revolution” (Kaase, 1984) during the 1960s and 1970s, US political scientists such as Huntington (1975) and his British (King, 1975) and German (Hennis, 1977; Kielmansegg, 1977) colleagues were concerned at how the increasing mobilisation of citizenry in the wake of the student protest movements and the liberalisation of political culture would affect the process of governing in Western democracies. Most famously, Huntington argued that an overly mobilised citizenry and an ever-expanding public sector meant that the future of Western societies was ungovernability. According to Huntington, governments were unable to cope with the demands they were facing. He summed this up in the formula that there has not only been a “substantial increase in governmental activity” but also a “substantial decrease in governmental authority” (Huntington, 1975, p. 64). Even if one does not share the conservative agenda of Huntington and his colleagues, this diagnosis has aged quite well in light of the contemporary dynamics of governing mentioned in the introduction to this article.

More recently, Blühdorn (2025) has returned to this debate by introducing the concept of “ecological ungovernability”. He argues that technocratic and emancipatory approaches to environmental policymaking are similarly exhausted. They are increasingly unable to guide policy, leading citizens to distance themselves from the underlying paradigms of environmentalism and liberalism. For this reason, he suggests, we are in a transition to a new phase of modernity, namely “post-liberal modernity” (Blühdorn, 2025, p. 20).1

The diagnosis of a full-blown crisis of governability, in the sense of an overall decline and the advent of anarchy, as described by Huntington and his German counterparts (Hennis, 1977; Kielmansegg, 1977), seems exaggerated in retrospect. Therefore, we use the term governmental problems and, synonymously, problems of governing; these are intended to strip away the conservative rhetoric that has characterised much of the literature on ungovernability (see Chamayou, 2021). The diagnosis of these proponents of the ungovernability literature, however, serves as the starting point for a more in-depth examination of governmental problems of eco-social politics today. We refer to them as politicisation overload, political inequality, the freedom-first trap, and legitimacy deficit.2

2.1 Politicisation overload

Proponents of the ungovernability thesis had argued that erosion of traditional motives for consent, the loss of community spirit, and the disappearance of non-political areas (i.e., the private sphere) together dissolve cultural prerequisites for governing. In German-language political theory, the locus classicus for this line of argument is the so-called Böckenförde Dilemma, named after the constitutional theorist and judge Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde, who asked whether the ongoing process of secularisation would, in the long run, dissolve the foundations of liberal-democratic regimes: “The liberal, secularized state rests upon presuppositions that it itself cannot guarantee”3 (Böckenförde, 1976, p. 60).

Half a century later, we can see that following the dissolution of traditional worldviews and religious norms (Inglehart, 2021), political regimes are not fundamentally unstable because they lack metaphysical foundations. However, secularisation increases the consciousness of contingency and practical choice. This enkindles an advancing process of politicisation (see Wiesner, 2021). Due to politicisation, grievances and discontent no longer appear as fate. They can be recognised as the result of political decisions made in the past and as something that can be influenced by policy. For this reason, more and more domains have become contested, in turn triggering more and more demands for governmental activity. The widespread diagnosis of a “post-politics” is therefore fundamentally flawed. On the contrary, we are entering an era of “hyper politics” (Jaeger, 2022) in which politics becomes more ubiquitous while policy becomes harder to implement.

This is significant because political theory has long diagnosed and critiqued a state of depoliticisation. On this basis, agonist theorists have argued that democratic legitimacy erodes when opportunities for politicisation are lacking (Mouffe, 2005, 2013). From this perspective, the hope—still shared by some theorists—is that renewed politicisation could help overcome these crises and reinvigorate democratic institutions. This hope has proven to be deceptive, as the advent of “hyper politics” (Jaeger, 2022) has not led to improved democratic decision-making and legitimacy, but rather to chaotic and permanent contestation, poor governance, and a lack of legitimacy of the political process. It seems that “hyper politics” (Jaeger, 2022), when viewed from the perspective of governments, is, in fact, a politicisation overload because it confronts governments with an almost unmanageable number of demands to meet or deflect (Adam et al., 2019).

This over-politicisation not only multiplies political demands directed at governments but also affects political communication and basic concepts of political life. Key concepts of political speech have become contested and ambiguous due to politicisation, which applies to concepts that are being used in political discourse on environmentalism and distributional justice, that is, concepts such as sustainability or fairness. As a result, politicisation overload poses the problem for governments of balancing conceptual clarity with the need for vagueness that maximises consent and responds to a variety of demands. This is exacerbated by the fact that digitalisation has led to an intensification and multiplication of political communication. Political discourse was traditionally mediated through traditional print and broadcast media, but the emergence of digital media has redefined the public sphere. Today, almost anyone can engage as a “prosumer”—simultaneously consuming and generating political content—which results in a continuous and more diffuse flow of political communication (Sánchez Medero, 2020; Stark et al., 2021).

2.2 Political inequality

In modern society, based on the division of labour, capitalist modes of production and distribution, and unequal power relations, the normal state of affairs is inequality. However, inequality is increasingly no longer perceived as a natural or inevitable fact. Rather, it can be attributed to political decision-making processes.

In this context, the growing scale and complexity of governance play pivotal roles. The phenomenon of an ever-growing governmental apparatus persists (and had already been described during the heyday of the debate on ungovernability), even though the overall public sector has not expanded since the 2000s. In effect, the so-called neoliberal era has not led to less public expenditure (IMF, 2025) and a shrinking of public bureaucracy (Nationaler Normenkontrollrat, 2024).

Governing now takes place in differentiated network structures of governance on different levels with varying degrees of interconnectedness, with ever more political actors included. Whether and how this has affected the problem-solving capacities of governments towards eco-social problems is a difficult question and one that may be impossible to answer in general. The complexity of contemporary governance, however, aggravates a phenomenon that was prominent in the discourses on ungovernability: while the citizenry attributes more and more responsibility for public problems to governments, the increasing political differentiation of governance, with its network structure and multiple levels, makes it more difficult for citizens to acquire the cognitive capacities and knowledge needed to understand policy issues and political procedures. What they do understand, is that this structure of governance favours the vested interests of well-organised groups, elite networks, socio-economically privileged groups, and insiders (Binderkrantz et al., 2021; Elsässer et al., 2017; Grote, 2020). Complex governance appears to them as a driver of growing inequality, creating unfair social conditions and unequal responsivity.4

From these perspectives, inequality is (once again) to be regarded largely as a political issue. As a result, governments face the constant task of either presenting the existing inequality as justified and fair or describing it as an injustice that needs to be overcome within a socio-economic system determined by a weakened but still dominant (neo)liberal paradigm. Governing actors constantly face the problem of constructing just inequality, distinguishing it from unjust inequality, and thereby reconciling their policy with its distributional effects. This also applies to environmental policy, as environmental issues not only compete with other concerns for the scarce resource of prioritisation during the agenda-setting process, but also raise questions such as: Who should contribute what to environmental protection or restauration? Which natural resources may (or may not) be exploited by whom and in what way? Who is responsible for financing and implementing social protection against environmental risks? Who is vulnerable and in need of social protection against the adverse socio-economic effects of environmental protection measures?

2.3 Freedom-first trap

Among the citizenry, traditional drivers of consent, loyalty, and self-restraint have largely dissolved, and duty-oriented political behaviour has become less common. Sociologists have consistently shown that the erosion of duty-oriented attitudes is prevalent, particularly among politically influential milieus and the university-educated middle class. The political culture of democratic regimes, in turn, has been transformed by an increased preponderance of individualistic values (Reckwitz, 2017). This is reflected, for example, in the fact that membership in political mass organisations is declining, political identification has become more fluid, and political engagement is more situational and of a transitory nature. While this may seem laudable if one considers democracy and liberalism as inherently linked, there is theoretical and empirical evidence that the erosion of social- and duty-oriented norms is indeed harmful to democratic government because it makes the acceptance of decisions and electoral outcomes less likely and reduces individuals' willingness to become permanently involved in democratic organisations and associations. Citizens are increasingly left to their own devices in their political engagement, whereby socially disadvantaged milieus often do not have the individual resources to compensate for the loss of social support through informal networks, social capital, and organisational membership (Armingeon and Schädel, 2014; Howe, 2017). Because liberal norms are less constrained by their embeddedness in social- and duty-oriented norms, unbound liberalism prevails, restricting governing insofar as it constitutes an implicit “freedom first” priority rule that favours liberal policies. With a view towards just eco-social policies, this inhibits duty-oriented solutions and poses the problem of how to enforce environmentalism against this “freedom first” rule.

2.4 Legitimacy deficit

The difficulties of generating democratic legitimacy, already addressed in the literature on ungovernability, has increased in recent times. This applies to both the input and output dimensions of legitimacy and is accompanied by a significant decline in citizen trust vis-à-vis the fulfilment of democratic norms and promises.

While there is considerable disagreement on how to explain and conceptualise this phenomenon, there is far-reaching agreement among political scientists that democratic regimes are currently in a crisis of trust. We can witness a “backsliding” of democracy.5 The process of “legitimation by procedure” (Luhmann, 1983) through the voting mechanism has ceased to function properly. As a result, the voting mechanism no longer ensures that public officials, simply by being elected, have sufficient legitimacy for governing.6 They are confronted with a chronic shortage of legitimacy that begins to affect the institutional structure itself (Turchin, 2023; Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018).

For a long time, the lack of procedural legitimacy had been compensated for by output legitimacy in the form of a widespread belief in continuous societal progress and the idea that economic growth would ultimately benefit all. Due to a growing sense of loss and pessimism regarding the future, the common belief that a rising tide lifts all boats (at least in the long run) no longer exists. Contemporary scholarship on democracy indicates that democratic regimes fail to live up to their normative promises, and this assessment is also widely shared within the citizenry (Przeworski, 2020; Schäfer and Zürn, 2021). Even though there has been no overall decline in public trust in governments (OECD, 2024), citizens' confidence in the state's ability to solve problems that involve many unknowns and trade-offs, such as the climate crisis or providing equal opportunities for all, has reached a very low level (OECD, 2024, p. 93–100).

To counter this increasingly pessimistic outlook on the future and disillusionment among the citizenry, governments must envision an appealing and progressive positive future that promises a fuller form of justice and ecological transformation. At the same time, however, they have to perform expectation management given their limited capabilities. They need to balance and decide between the various demands within the “eco-social-growth trilemma”7 (Mandelli, 2022) in the economic context of worsening conditions and within a political timeframe that is shaped by the tension between short-term electoral cycles and the long-term requirements of transformative change. Consequently, in eco-social policy, governments are compelled to reconcile a pragmatic vision of what is feasible with a utopian vision on what is just and legitimate.

Table 1 summarises our conceptual scheme.

3 Empirical illustration: the Buildings Energy Act in Germany

In this section, we empirically illustrate the heuristic potential of our conceptual scheme. Our case study is the development of eco-social policy in Germany, a particularly interesting case because the institutional, socio-economic, and political factors at play are both enabling and constraining Germany's just transition (Finkeldey et al., 2024).

The German polity has long been described as a coordinated market economy (Hall and Soskice, 2001) paired with a conservative welfare state. It combines strong elements of consensual democracy with a corporatist tradition of negotiation between social, economic, and political actors. Its economic model is based on its deep integration into neoliberal globalisation and relies on export-led growth. Among Germany's political parties, there is a broad consensus on the need to act on climate change, except for the right-wing populist and far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). The Green Party (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen), although somewhat diminished by the recent federal elections (Bundeswahlleiterin, 2025), and the environmental and social movements are important political players (Buzogány and Scherhaufer, 2022; Cremer, 2024). Most parties are committed to “green growth”.

Regarding its eco-social performance, Zimmermann and Graziano (2020, p. 11) argue that Germany has an “above-average social performance but far-below-average eco performance”. Germany has set itself the objectives of becoming climate neutral by 2045 [Federal Climate Action Act [Bundes-Klimaschutzgesetz - KSG], 2024] and phasing out coal by 2038. Its eco-social policy is embedded in the European climate and environmental policy framework and incorporates the eco-social imaginaries that are prevalent in the European multi-level system (Klüh et al., 2024). Its energy sector is a frontrunner in the green transition, while the buildings and transport sectors have failed to meet their targets for several years (Wehnemann et al., 2025). So far, there have been only tentative signs of a committed eco-social policy, with social policy limited to a compensatory role (Gerstenberg, 2024) and a focus on social investments (Im et al., 2024).

It is beyond the scope of this brief case study to illustrate the four challenges of governability in relation to Germany's overall eco-social development. This section will therefore focus on the debates surrounding the Buildings Energy Act [Gesetz zur Einsparung von Energie und zur Nutzung erneuerbarer Energien zur Wärme- und Kälteerzeugung in Gebäuden, GEG], (2024) between 2020 and 2025. This example is instructive because the buildings sector—accompanied by the associated transition to decarbonised heating systems—plays a central role in the broader green transition and paradigmatically reveals “social-ecological transformation conflicts” (Dörre, 2022). In addition, this heat transition has a more direct and tangible physical and economic impact on all social classes, regardless of their housing situation, which raises several issues of distributional justice, especially in comparison to the energy transition and the coal phase-out. Despite the importance of the heat transition, Germany's handling of the eco-social-growth trilemma in the context of this transition has received considerably less scholarly attention than, for example, Germany's ongoing coal phase-out (Arora and Schroeder, 2022; Herberg et al., 2024; Hermwille et al., 2023; Reitzenstein et al., 2021; Schuster et al., 2023) or industrial decarbonisation (Haas, 2021; Im et al., 2024).

The Buildings Energy Act (GEG), commonly referred to as the “Heating Law”, was introduced in 2020 during Chancellor Angela Merkel's fourth cabinet (a coalition between the conservative CDU/CSU and the social-democratic SPD). The main objective of this legislation is to achieve climate targets in the buildings sector and to implement corresponding European directives. The buildings sector was responsible for approximately 15 percent of Germany's total greenhouse gas emissions in 2023 (Wehnemann et al., 2025), while more than 70 percent of German homes still rely on fossil fuel heating systems (Bundesverband der Energie- und Wasserwirtschaft, 2024). The Act sets energy efficiency requirements for existing buildings, new buildings, and heating and cooling systems. It includes financial support programmes to promote the use of renewable energy sources for heating and cooling, alongside measures to improve overall energy efficiency.

The Act attracted considerable public attention in the wake of the intense debate on its revision in 2023 by the so-called traffic-light coalition (consisting of the social-democratic SPD, green-alternative Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, and pro-market liberal FDP). The revised version introduced a requirement (Buildings Energy Act [Gesetz zur Einsparung von Energie und zur Nutzung erneuerbarer Energien zur Wärme- und Kälteerzeugung in Gebäuden, GEG], 2024 Art. 71) that by 2028 at the latest, all newly installed heating systems must use at least 65 percent renewable energy (a de facto ban on fossil-fuel-only heating systems), with implementation timelines staggered by building type and supplemented by financial support programmes. The Buildings Energy Act also became a key issue in the 2025 federal election and the subsequent coalition negotiations between CDU/CSU and SPD, with discussions focusing on either revision, repeal, or replacement.

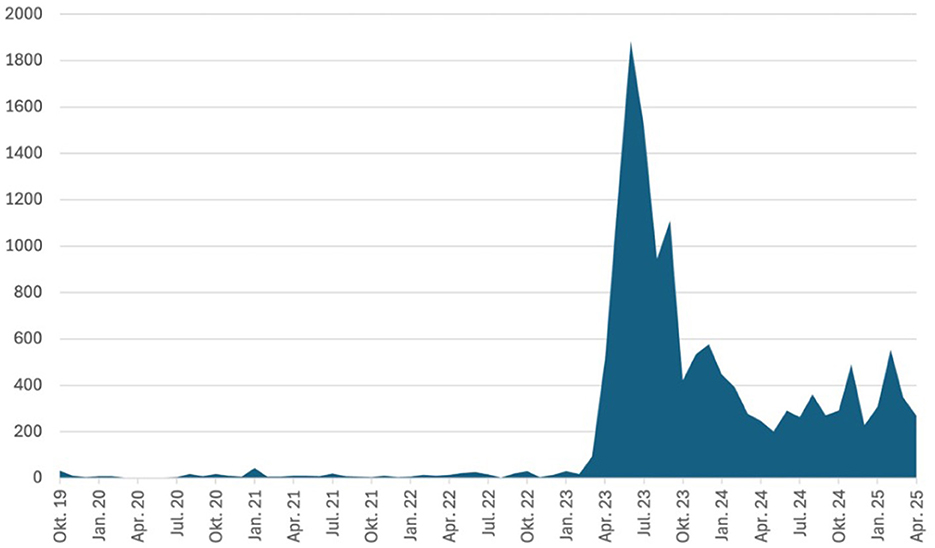

3.1 Politicisation overload

Newspaper coverage indicates that the GEG has been one of the most widely discussed laws of the green transition in Germany in recent years (see Figure 1). While coverage of the GEG was relatively low in its early years, it increased sharply in 2023 after the so-called traffic-light coalition announced that it intends to revise the law. The coverage peaked during the numerous crisis summits of the traffic-light coalition to reach an agreement8 and remained at a high level even after the Bundestag (German parliament) passed the revision to the law in September 2023.

Figure 1. Development of news coverage of the Buildings Energy Act over time. Own figure. Measured by the number of newspaper articles. Data refer to a scan of newspaper articles in Germany with the keywords Gebäudeenergiegesetz and Heizungsgesetz in the LexisNexis database in the period from October 2019 to April 2025.

Jost et al. (2024) showed in their study on the coverage of the GEG between January and October 2023 that the overall assessment of the act was predominantly negative. This applies to both the portrayal of the political actors involved in the revision debate—the governing parties, in particular Bündnis 90/Die Grünen and the FDP, as well as the opposition parties CDU/CSU and AfD—and to substantive aspects such as public acceptance, economic consequences, and the public communication of the content of the law. Especially in the reporting of the right-wing media and in Germany's biggest tabloid newspaper, Bild, which has been campaigning against the revision of the GEG, this is most obvious. As a “polarising entrepreneur” (Mau et al., 2023, p. 374), the tabloid, with its “Heizhammer” (heating hammer) (Schäfer et al., 2023) campaign, widely echoed on social media, contributed significantly to creating an emotionalised and politicised environment that fuelled widespread protests.

In this constellation, a multitude of competing demands and ideas collided in the debate on the revision of the GEG in 2023, both within and outside the government. While the governing FDP was primarily committed to technological openness and trust in the market, with carbon pricing as the central instrument for the transition (FDP, 2021), the governing Bündnis 90/Die Grünen proposed a much more integrated eco-social approach, with clearer ecological requirements for heating, investment measures, and socially differentiated subsidies (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, 2021). The governing SPD was mainly concerned about social repercussions and the public and private investment needs (SPD, 2021). The coalition partners were confronted with the biggest opposition party, CDU/CSU, which focused on the issues of an alleged lack of technological openness, severe social impacts, declining growth, and a loss of competitiveness. It mainly played off social anxieties about rising living costs and demands for growth and pitted them against the GEG's ecological goals. The CDU/CSU's politics and, to an even greater extent, those of the right-wing populist AfD, served an overall strategy to dismantle the law and can be described as “secondary climate obstruction” (Ekberg et al., 2023; Haas et al., 2025). Along with this came a diverse and conflictual civil-society landscape in which defenders of the status quo and pragmatists on the one hand and an eco-social alliance and activists on the other each brought forward their conflicting demands regarding the intensity and breadth of the eco-social transition (Cremer, 2024). Against this backdrop, Sander (2024) is correct in describing the entire landscape of affected interests as a field of struggle for hegemony.

The traffic-light coalition had difficulties coping with this multitude of competing demands and their inherent conflicting understandings of fundamental concepts such as fairness, social vulnerability, technological openness, and growth. It failed to effectively balance the need for conceptual clarity with the strategic vagueness required to maximise consensus. The formula of building a “progressive alliance for freedom, justice and sustainability” (SPD., Grüne, and FDP, 2021) did not prove to be a unifying narrative. The contradictions between the coalition partners came to the fore in the formulation and specification of their idea for the German heat transition.

Even the final GEG compromise adopted by the Bundestag in September 2023 did not put an end to the disputes. Instead, ongoing conflicts over the GEG shaped the federal election campaign in the winter of 2024–25, after the so-called traffic-light coalition collapsed and early elections were called. The SPD (2025, p. 33–34) advocated revisions, the CDU, CSU (2025, p. 20) and the FDP (2025, p. 44) advocated a reversal and repeal, whereas Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (2025, p. 44–45) advocated staying the course and increasing social compensation. The CDU/CSU–SPD coalition government that took office in the spring of 2025 must now continue to work on these conflicts because the compromise reached in their coalition agreement is, in fact, a formulaic one, as it simply lists conflicting goals without explaining how those conflicts are to be solved.9

3.2 Political inequality

When governments attempt to construct just inequality in the buildings sector, they must take into account the distributional effects of (and citizen attitudes toward) different policies, recognising that their perception of the fairness of a given policy is the most important factor driving their support (Bergquist et al., 2022).10 The vulnerability of citizens to retrofitting requirements and rising heating costs due to rising carbon prices depends on their housing situation, the efficiency class of the buildings they live in, and the household's income level (Koukoufikis and Uihlein, 2022; Knoche et al., 2024). Renovation rates also vary by income level. Proposals for more interventionist “push” instruments (pricing and regulation) are generally less accepted by citizens than “pull” instruments such as infrastructure/supply improvement, subsidies, and information/advice (Heyen and Schmitt, 2024). Consequently, push instruments need to be accompanied by packages of financially robust support measures for affected groups. Additionally, scholars underline the importance of an effective communication strategy.

Against this background, the Merkel-led CDU/CSU–SPD coalition government at the time of the GEGs introduction in 2020, and eventually even more so the traffic-light coalition, were confronted with the following questions (see Mandelli et al., 2024; Nullmeier, 2024): what exposures, eco-social risks, and vulnerabilities do they anticipate as a result of the new and increased efficiency and sustainability requirements for heating? Which groups will be most affected? Which of these exposures, risks, and vulnerabilities do they consider unfair and in need of action? And how do they intend to counteract them?

In view of the very negative reactions to the first draft of the revision of the GEG in the spring of 2023, the traffic-light coalition attempted to address the aspects mentioned at the beginning of this subsection by making various adjustments aimed at making the ultimately passed revision fairer.11 For example, they exempted existing buildings from the obligation to use renewable energies when replacing heating systems until 2026 or 2028, depending on the finalisation of the respective municipal heat planning. In addition, the coalition partners increased the subsidy to cover up to 70 percent of total costs, according to a socially graduated formula.

Nevertheless, 45 percent of the population felt that the GEG went too far (Infratest Dimap, 2023b, p. 9). Of note, 76 percent did not feel informed or not sufficiently informed (Infratest Dimap, 2023a, p. 6). This is partly due to the constant changes in the revision of the GEG until its final adoption, and the complex relationships between the GEG and European directives, also containing requirements for the building sector, which are difficult for the average citizen to understand. Most importantly, 67 percent of citizens felt overwhelmed by the expected costs (Infratest Dimap, 2023a, p. 6), despite all the changes made during the process. The traffic-light coalition thus failed in its attempts to address the governing problem of constructing just inequality, both in terms of content and in terms of communication.

3.3 The freedom-first trap

As noted above, prohibitive policies struggle to gain public acceptance, in Germany as everywhere else. At the same time, policies based on incentives—such as the approach initially taken in the Buildings Energy Act 2020—proved to be ineffective. Its steering effect was weak, and renovation rates remained insufficient until 2023, when the traffic-light coalition decided to revise the GEG. The approach of merely referring to the distant phase-out date for fossil-fuel heating systems in 2044 (Art. 72 Buildings Energy Act [Gesetz zur Einsparung von Energie und zur Nutzung erneuerbarer Energien zur Wärme- und Kälteerzeugung in Gebäuden, GEG], 2024) and the moderate efficiency requirements and financial incentives introduced by the Grand Coalition under Merkel's fourth government (CDU/CSU–SPD), therefore, needed to be adjusted.

As the building sector remained problematic, stricter ecological regulations with clear obligations for the replacement and installation of specific heating systems would have been necessary. The original draft of the GEG revision took this into account (Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action, 2023). However, intense “freedom-first” criticism from within the governing coalition and, in particular, from the conservative and right-wing populist opposition, which disseminated narratives about the impending disenfranchisement of German citizens, state surveillance of heating systems, and the need for an “ideology-free” openness to technological innovation (Haas et al., 2025), fuelled by the aforementioned media campaign, ultimately led to a final version of the revised GEG that permits almost all heating technologies. The GEG now even includes support for fossil-based systems, for biofuels, and for hydrogen heating systems (Art. 71; 90 Buildings Energy Act [Gesetz zur Einsparung von Energie und zur Nutzung erneuerbarer Energien zur Wärme- und Kälteerzeugung in Gebäuden, GEG], 2024). This will lead to consumer confusion, stranded assets and, worst of all, limited or no emissions reductions in the buildings sector. Green hydrogen, for example, will remain scarce for the foreseeable future, and its use will be limited to industrial processes that are difficult to electrify.

In the end, the traffic-light coalition fell into the freedom-first trap: what began as legislation to provide strict regulation became a patchwork of law that permitted a plurality of heating systems and watered down all requirements—in the name of freedom at the expense of progress towards climate neutrality.

3.4 Legitimacy deficit

In Germany, on the one hand, a general awareness of the climate crisis and the need for action prevails across most social strata. Citizens believe that those in power should take appropriate measures to achieve the climate objectives agreed within the EU governance framework (Hagemeyer et al., 2024). They also criticise the perceived lack of progress and the alleged unwillingness of those in power to act accordingly (Wolf et al., 2023).

On the other hand, 70 percent of German citizens are not convinced that the state is able to cope with its tasks and solve the problems of climate protection and social security (Forsa, 2024; Hagemeyer et al., 2024). Furthermore, there is only a low level of acceptance of bans and other measures that are perceived as bans (Blesse et al., 2024). The state's limited financial capacity due to the constitutional restriction on public debt12 represents an additional barrier. External crisis events, such as the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, worsen the situation by making Germany's dependence on fossil energy more apparent in the form of sharp price increases for electricity and heating.

Against this backdrop, the three government coalitions used distinct future narratives to generate legitimacy in the investigation period covered by this article, which can be distinguished in their approach to the eco-social-growth trilemma. During the last Merkel government (CDU/CSU–SPD), the narrative prevailed that the transition would be a win-win situation. The coalition ignored that there were trade-offs between environmental, social, and economic goals, and it suggested the transition could proceed without restrictions and negative repercussions. In contrast, the traffic-light coalition (SPD, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, FDP) was aware of these trade-offs, including the negative social consequences of climate policy, and saw the need for a more policy-integrated approach. It sought to combine its more ambitious ecological goals with mechanisms for social compensation, while remaining committed to the green growth paradigm. But in the face of the budget crisis13 and public uproar against the “heating hammer”, it became tangled up in integrating these conflicting objectives into concrete, operational policy proposals and legislation. It ended up pursuing a far less ambitious, business-as-usual policy, not only regarding the buildings sector. The current CDU/CSU–SPD government coalition seems to put ecological, social, and growth objectives back into a hierarchical order by giving priority to growth. Its room for manoeuvre to implement its vision of the future, however, has increased because it eased the debt brake.

What all three government narratives have in common is that they are neither sufficient in the face of massive environmental and social challenges, nor do they offer convincing future visions that can mobilise consent among the citizenry for the eco-social transformation and restore trust in the democratic system. Leaving aside their respective public rhetoric, all governments have pursued liberal policies that, while differing greatly in detail, have generally refrained from strong regulatory intervention and downward social redistribution. In the end, there prevailed a liberal policy intended to give priority to the market and take account of freedom and the plurality of lifestyles.

4 An exploration of green republican resolutions

Having zoomed in on a specific case to apply our conceptual scheme, this section zooms out again to adopt a more macro-level normative and institutional perspective. We begin by arguing that late-modern liberalism is under increasing challenge and unable to solve those governmental problems we have outlined. We then explore whether green republicanism might offer an alternative paradigm for dealing with the challenges of governing today.

Liberal and liberalism are ambiguous terms that cover a wide political spectrum. In the US, they include a left-liberal tradition close to democratic socialism, as seen in John Dewey during the New Deal (Dewey, 1935) and Michael Walzer since the 1970s (Walzer, 2023). In today's usage, the term still signals a left-liberal politics. But at the same time, the terms also denote moderately conservative politics, as seen in Walter Lippmann's rejection of John Dewey's interventionist and egalitarian views, a stance now echoed by centrist-liberal intellectuals, such as Fareed Zakaria, and sometimes referred to as the hallmark of “classical liberalism”. While European liberalism displays less ideological variety, left, centrist, and right-wing variants of liberalism have always existed there as well. For this reason, it is not surprising that the prevailing view in academic research is still that liberalism is an ambiguous ideology and political discourse.

However, during the Cold War and especially after the beginning of the new world order post-Cold War, the complexity that liberalism has in theory and discourse does not materialise in practical politics; on the contrary, the triumph of neoliberalism has led to a narrowing of liberalism's political range and the marginalisation of left-liberal ideas in particular (Moyn, 2023). As a result, in current political life liberalism can be understood as an ideology for practical politics that denotes a rather delimited set of policy options. This watered-down but hegemonic liberalism—whose influence was also visible in the above-described case—can be broken down into rules of thumb that formulate normative rules of priority for politics:

- The market takes precedence over the state.

- Freedom takes precedence over equality.

- Representation takes precedence over participation and popular sovereignty.

- Pluralism takes precedence over notions of the common good.

Recent developments in politics and theory, however, signal a departure from this liberal political paradigm. Most notably, the US administration under Trump is currently implementing post-liberal policies such as the restriction of freedom of expression and movement. It is also initiating a neo-mercantilist trade policy and undertaking several other “de-globalist” measures. While it remains to be seen whether this approach, in economic terms already underway under Biden's administration, will also be adopted in Europe, these policies can be interpreted as the beginning of a weakening of the liberal paradigm in politics. In the realm of theory, post-liberal paths have also been tried out for some time (Borg, 2023), not least because a discussion among liberals has broken out as to whether we can expect a retreat of liberalism in the future (Fukuyama, 2022). Against this backdrop, Blühdorn (2025) argued that the exhaustion of the approach of ecological modernisation and the participatory eco-emancipatory project signals a transition to a new phase of modernity, namely “post-liberal modernity” (Blühdorn, 2025, p. 20), in which liberal notions of politics are losing their validity. All of this indicates that liberalism, while still the dominant political paradigm in Western democracies, no longer occupies the unchallenged position it did over recent decades.

What is more, it is probably evident that the governmental problems we have identified cannot be solved by following the described liberal rules of priority without largely abandoning eco-social issues. The prioritisation of market solutions, the strengthening of the principle of (negative) freedom, and the re-establishment of elitist forms of representation could, if successful, curb tendencies towards politicisation and work towards making inequalities appear justified, at least in the short term. However, this would only be possible at the cost of weakening or even abandoning ecological and social goals, which are constitutive for eco-social policy. In the long term, this would also lead to a deepening of political and social inequality and thus further disintegration and exacerbation of legitimacy problems. Liberalism in its current, unbounded form has therefore become problematic itself because it is not balanced by other political paradigms, as was the case in the past before neoliberalism took off. Without these checks, it undermines itself and shows little capacity for self-correction or learning. We therefore are keen to explore whether green republicanism as an alternative political paradigm could offer a way out.

Republicanism is not an approach anchored within movements or parties, but primarily an academic theoretical discourse that draws on the tradition of ancient and early modern republican theory (Skinner, 1980) and updates it with a view to contemporary politics in democracies. Two dominant variants can be distinguished. A more moderate Roman-civic variant (Pettit, 2012, 2016), which is participatory but at the same time aims at containing plebeian politics, and a democratic-radical variant, which proposes to strengthen plebeian forms of politics to counter oligarchic tendencies within contemporary democracies (McCormick, 2011). Under the banner of green republicanism, republican theory has for some time been applied to questions of ecological politics (Barry and Smith, 2008; Heidenreich, 2023; Fremaux, 2019; Slaughter, 2008), with the Roman-civic variant of republicanism in particular being adopted (for a critique from a radical point of view, cf. Dingeldey, 2024).

Green republicanism is not yet a fully developed theory, but rather an idea and a semantic marker that various authors have taken up and an aspiration to which those authors refer. A coherent and systematic theory of green republicanism exists only in its infancy. Therefore, in the following, we will gather several practical proposals for giving an eco-socially oriented policy more clout that can be found in the literature on green republicanism and allocate them to the four problems of governing we have identified.

Republican antidotes to politicisation overload: the stability and permanence of an orderly republic is a topos of republican thinking. And even though republicans do not consider political conflicts to be problematic so long as they remain within the republic's institutional framework, an excess of demands on the republic is considered a potential threat to its stability. In green republican theory, this calls for institutional proposals as to how environmentally oriented policy can be made permanent and how an ecological attitude can be perpetuated in the citizenry in the context of an overload of rivalling demands. To this end, green republicans firstly propose the introduction of a “compulsory ‘sustainability service”' (Barry, 2016, p. 336). This is considered to fulfil ecological and socialising functions. The aim is to establish a sense of duty to the community and the environment as a collective task to which everyone, regardless of social status, must contribute. Secondly, the institutionalisation of “environmental rights” (Dodsworth, 2021) is proposed. This strategy of judicialisation needs to be distinguished from similar proposals that have been brought forward in the literature on environmentalism because green republican theorists argue also for “regionalism” (Cannavò, 2010) and “frugality and modesty” (Barry, 2008, p. 6), following the republican suspicion against any form of luxury and overstretching of the polity by allowing for free trade, consumerism, and boundless mobility. Thus, republican environmental rights would therefore be implemented in a regionalist and frugalist manner, meaning that they would impose far-reaching restrictions on trade, mobility, consumption, and production.

Republican proposals for countering political inequality: green republicanism engages with environmental issues in the context of an egalitarian (and partly anti-capitalist) approach towards economic policy (McGeown, 2025). There are various suggestions in the literature as to how this could be put into practice. Firstly, green republicans are concerned with introducing co-determination at the workplace and democratising firms and businesses (Barry, 2021). Secondly, they advocate for restoring the primacy of the state in economic policy with the aim of not only regulating but also decommodifying social spheres that have been commodified during the neoliberal era (Slaughter, 2008). This also involves policies such as a universal basic income cum sufficiency that, green republicans argue, would put an end to the capitalist economy's structural compulsion to acceleration and growth generation, thereby aiming at an end of the “tyranny of economic growth” (Barry, 2021). Thirdly, green republicans suggest that a communitarian ethos must also be anchored among citizens, which in the form of patriotism, must not be confused with chauvinistic national pride. Rather, it is meant to strengthen reciprocal obligations and thus also solidarity. Patriotism is seen here as a vehicle for anchoring virtue within the citizenry. Fourthly, proponents of the radical democratic variant of green republicanism propose the institutionalisation of plebeian institutions and countervailing powers to counter the structural superiority of oligarchic power that stems from money and other resources (Scerri, 2023).

Republican proposals for escaping the freedom-first trap: contemporary republican theorists see the unleashing of individualism and the rule of the stronger over the weaker as expressions of a liberal concept of freedom, which understands freedom to mean non-interference. This concept legitimises imbalances of power because, according to this liberal concept, relations of power are just as long as the powerful respect the rule of law and do not arbitrarily interfere in the individual life plans of the powerless. Republicans counter this with a different concept of freedom. Stemming from the philosopher Philip Pettit and the historian of ideas Quentin Skinner, this concept's core principle is that of non-domination (Pettit, 2016), in which freedom is only possible within a framework of self-legislation, thus giving each citizen the equal power to shape those laws.

Green republicanism adopts this concept of freedom. At the same time, it restricts it by giving priority to the common good, following classical republican thinking. As McGeown puts it: “The centrality of this practical concern for the common good to republican thought marks a fundamental distinction from liberalism's ontological focus on the ‘sovereign' individual and its resulting ideological preoccupation with individualism” (McGeown, 2025, p. 139). Notably, in green republicanism the common good is understood in “ecocentric” terms (Curry, 2020, p. 32). Green republicanism is therefore not only non-neutral towards definitions of the good life (Pinto, 2019) but also advocates an ecological conception of the common good. This is based on an ontology in which interdependence with nature, dependence on the natural environment, and a sustainable relationship with nature are key (Barry and Smith, 2008). The freedom that green republicans advocate is a bounded form of freedom.

Republican answers to the problem of legitimacy deficit: firstly, green republicans propose to tackle the current legitimacy problems by opening the political process to practices of contestation (Wissenburg, 2019). The aim here is to institutionalise the expansion of policy options for strong ecological measures and prevent technocratic policymaking. Secondly, they argue for the introduction of citizens' councils, in which participants drawn by lot would deliberate and decide on those environmental policy measures (Heidenreich, 2023). Third, green republicanism is beginning to engage with the writings of John P. McCormick (Scerri, 2023). They are particularly relevant to the question of how a more inclusive eco-social politics can be conceived because McCormick's radical republicanism aims at institutional changes that go beyond the above-mentioned proposals. The latter are intended to supplement the institutions of liberal-representative democracy but not to fundamentally change them. This holds true regarding, for example, the introduction of expert or citizens' councils. In contrast to these rather moderate measures, McCormick devises elaborate, institutional-level reform plans for tackling the legitimacy crisis and the rise of right-wing populism, in such a way that the responsiveness of the political system increases and, at the same time, governability is guaranteed again. To this end, he argues for the introduction of ancient Roman-plebeian institutions such as the tribunate of the people, public political trials that can be brought by ordinary citizens against members of the political elite, and appointment for public office by a combination of lottery and election (McCormick, 2011, 2006).

As mentioned above, green republicanism does not yet represent a coherent theory. The proposals presented here, which we have taken from the existing literature on this subject, reflect its status as an incipient and not-yet-consolidated movement of thought and could certainly benefit from a stronger social dimension and more integrated eco-social thinking. Although the proposals can be meaningfully related to the problems we developed in section two, they do not represent a consistent programme. It would therefore be unrealistic to claim that this is a ready-made answer to the current problems of governability and a replacement for liberalism and the dominant “green growth” policy. In fact, what we have presented so far is only an unsystematic, strongly normative and appellative collection of ideas of what would be conceivable by turning to the republican tradition of political thought and applying it to the subject of eco-social politics. Therefore, our view is that further research must work to develop the literature on green republicanism from the normative level towards a more realist body of political theory that, for instance, focuses on how the different social milieus and classes could be mobilised for a green republican project, which interests correspond to such a project, and which discursive and organisational strategies would be conducive to its dissemination.

5 Conclusion

This article has sought to contribute to an understanding of contemporary problems of governing in the field of eco-social politics by developing and applying a conceptual scheme that combines insights from the ungovernability literature with more recent scholarship. The heuristic value of this scheme was demonstrated through an analysis of the debates around the German Buildings Energy Act, which revealed the practical manifestations and consequences of four problems: politicisation overload, political inequality, the freedom-first trap, and a legitimacy deficit. Arguing that liberalism as a paradigm is incapable of solving these problems, and given liberalism's weakened status, we turned to the discourse of green republicanism and explored its proposals for responding normatively and institutionally to the pathologies of contemporary governance.

Taken together, the three parts of the article form an analytical arc. The conceptual scheme identifies the structural constraints under which eco-social politics must currently operate. The empirical case illustrates how these constraints generate friction and conflict in concrete political processes. The exploration of green republicanism, in turn, points to an alternative political paradigm that might help to overcome the four problems embedded in liberalism's structural blind spots by reformulating and “greening” the idea of freedom and strengthening democratic legitimacy through institutional reform. For this purpose, however, further development of this theoretical paradigm—which so far is only in its infancy—would be necessary.

The main insight of our article is that the central problems in pursuing eco-social policies are structural in nature. As a result, they cannot be solved by improving governmental communication and PR or similar low-threshold proposals. Green republicanism can be a first starting point for thinking about reform proposals that would imply structural change. However, an important caveat should be made: it should not be ruled out from the outset that the problem of governability may recur at a different level, as even the institutional reform that is deemed to solve the problem of governability could fail due to the non-implementability of this reform or lack of mobilising power. One may refer to this as second-order ungovernability.14 Against this backdrop, we see three issues for further research.

Firstly, there is an urgent need for research in eco-social science on the question of how ideas for far-reaching political reforms might be put on the political agenda. At present, green republicanism is an academic school of thought at best, and a theoretically devised wish list at worst, but not a political programme anchored in practice. Reflecting on how alternative political paradigms such as green republicanism may gain more traction seems ever more important. Particularly given that our diagnostic conceptual scheme in section two reveals that our democratic regime in its current form is no longer able to fulfil one of its core functions: the ability to self-correct, to learn, and to open up political decision-making to alternative political ideas. While the current post-liberal turn moves in a direction that is worthy of criticism and cause for concern, it may also indicate that there is a need to think about political programmes and concepts that deviate from liberalism without resorting to reactionary ideas. Against this backdrop, it can be worthwhile to engage with political ideas that are currently still marginal and have no anchorage in the political mainstream. It is worth remembering that in its early days, neoliberalism was a political ideology that only found support on the fringes of intellectual discourse.

Secondly, the proposals discussed in section four show overlaps with proposals that have already been brought forward in the scholarly literature on eco-social politics. For this reason, it would also be worthwhile to examine the similarities and differences between green republicanism and related concepts in the field of eco-social transformation at a conceptual level. This includes, for example, the literature on sustainable welfare, post-capitalism, post-liberalism, and de- and post-growth. Of particular interest would be whether these different approaches and fields of research can benefit from each other. Furthermore, it would be fruitful to explore in more detail green republicanism's most contentious aspect, namely patriotism and bring it into dialogue with the emerging field of study on “nationalism and climate change” (Conversi, 2020) and “green nationalism” (Posocco and Watson, 2022).

Finally, the way we describe problems of governing today can be criticised, and these problems may require different answers than we have proposed. However, we believe that this article has at least shown that the issue of ungovernability is not only of historical interest but also an important topic that deserves more attention in research.

Author contributions

VS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. They acknowledge funding for the publication of this article by the Publications funds of Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU Wien).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^We will come back to the significance of this diagnosis in Section 4.

2. ^The following also builds upon social-theory-driven macro-diagnoses by Blühdorn (2024) and Selk (2023).

3. ^Unless stated otherwise, responsibility for all translations from German to English lies with us.

4. ^Fewer than one in three citizens believe the government would refuse a company's demand if it went against the public interest (OECD, 2024, p. 100). Notably, 40 percent of citizens in OECD countries do not believe that parliament fairly balances the interests of different groups when debating a policy (OECD, 2024, p. 150).

5. ^It should be mentioned that the diagnosis of democratic backsliding is empirically controversial. Little and Meng pointed out that there has been no decline in the number of changes in government triggered by elections (Little and Meng, 2024).

6. ^Almost 50 percent of citizens in OECD countries do not believe that the political system allows the people to have a say in what the government does (OECD, 2024, p. 106).

7. ^This concept describes the difficulties governments face in reconciling environmental policy goals (respecting planetary boundaries), social goals (fair distribution of resources and opportunities, prevention of risks), and economic growth (on which economies currently depend) as their relationship is characterised not only by synergies but also by trade-offs and incompatibilities. To address this trilemma, governments can consider three policy responses: pursuing separate goals, arranging goals hierarchically, or taking an integrated approach to balancing competing goals.

8. ^For a detailed chronological overview of the revision debate within the traffic-light coalition, see Caspari et al. (2023).

9. ^Their coalition agreement states: “Affordability, technology openness, supply security, and climate protection are our goals for modernising the heat supply. We will repeal the Heating Act. We will make the new GEG more technology-open, flexible, and simple” (CDU, CSU, and SPD, 2025, p. 24).

10. ^On the general attitudes of the German population towards eco-social change, see the Sinus-Milieu study by Detsch (2024), but also Hagemeyer et al. (2024).

11. ^However, some of these adjustments compromised the revision's ecological stringency (see Subsection 3.3).

12. ^The debt brake is a German constitutional provision that limits the amount of new debt the federal government and the states can incur.

13. ^In 2023, Germany experienced a budget crisis after the Constitutional Court ruled the reallocation of €60 billion—originally earmarked to address pandemic-related challenges—to be unconstitutional. The traffic-light coalition then engaged in intense debates and disagreements about how to close the resulting financial gap.

14. ^The authors are thankful to one anonymous reviewer for pointing this out to us.

References

Adam, C., Hurka, S., Knill, C., and Steinebach, Y. (2019). Policy Accumulation and the Democratic Responsiveness Trap. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Armingeon, K., and Schädel, L. (2014). Social inequality in political participation: the dark side of individualisation. West Eur. Polit. 38, 1–27. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.929341

Arora, A., and Schroeder, H. (2022). How to avoid unjust energy transitions: insights from the Ruhr region. Energy Sustain. Soc. 12:19. doi: 10.1186/s13705-022-00345-5

Barry, J. (2008). Towards a green republicanism: constitutionalism, political economy, and the green state. Good Soc. 17, 1–11. doi: 10.2307/20711292

Barry, J. (2016). “Citizenship and (un)sustainability: a green republican perspective,” in The Oxford Handbook of Environmental Ethics, eds. S. M. Gardiner and A. Thompson (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 333–343. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199941339.013.30

Barry, J. (2021). Green republicanism and a ‘just transition' from the tyranny of economic growth. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Polit. Philos. 24, 725–742. doi: 10.1080/13698230.2019.1698134

Barry, J., and Smith, K. (2008). “Civic republicanism and green politics,” in Buildings a Citizen Society: The Emerging Politics of Republican Democracy, eds. D. Leighton and S. White (London: Lawrence and Wishart), 123–145.

Bergquist, M., Nilsson, A., Harring, N., and Jagers, S. C. (2022). Meta-analyses of fifteen determinants of public opinion about climate change taxes and laws. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 235–240. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01297-6

Binderkrantz, A. S., Blom-Hansen, J., and Senninger, R. (2021). Countering bias? The EU Commission's consultation with interest groups. J. Eur. Public Policy 28, 469–488. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2020.1748095

Blesse, S., Dietrich, H., Necker, S., and Zürn, M. K. (2024). Wollen die Deutschen beim Klimaschutz Vorreiter sein und wenn ja, wie? Maßnahmen aus Bevölkerungsperspektive. ifo Schnelldienst 77, 39–43.

Blühdorn, I. (2025). Ecological ungovernability and the transition to postliberal modernity: on the dialectic of the eco-emancipatory project. Eur. J. Soc. Theory. 1–29. doi: 10.1177/13684310251330872

Böckenförde, E-. W. (1976). “Die Entstehung des Staates als Vorgang der Säkularisation,” in Staat, Gesellschaft, Freiheit: Studien zur Staatstheorie und zum Verfassungsrecht, ed. E.-W. Böckenförde (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp), 42–64.

Bohnenberger, K. (2023). Peaks and gaps in eco-social policy and sustainable welfare: a systematic literature map of the research landscape. Eu. J. Soc. Secur. 25, 328–346. doi: 10.1177/13882627231214546

Bonvin, J. M., and Laruffa, F. (2022). Towards a capability-oriented eco-social policy: elements of a normative framework. Soc. Policy Soc. 21, 484–495. doi: 10.1017/S1474746421000798

Borg, S. (2023). In search of the common good: the postliberal project left and right. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 27, 3–21. doi: 10.1177/13684310231163126

Buildings Energy Act [Gesetz zur Einsparung von Energie und zur Nutzung erneuerbarer Energien zur Wärme- und Kälteerzeugung in Gebäuden, GEG]. (2024). Available online at: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/geg/ (Accessed April 25, 2025).

Bundesverband der Energie- und Wasserwirtschaft. (2024). “Wie heizt Deutschland?” (2023) - Ergebnisbericht - Studie zum Heizungsmarkt. Available online at: https://www.bdew.de/media/documents/Wie_heizt_Deutschland_2023_-aktualisierte_Fassung-_BDEW_1.pdf (Accessed April 25, 2025).

Bundeswahlleiterin. (2025). Bundestagswahl 2025. Ergebnisse. Available online at: https://www.bundeswahlleiterin.de/bundestagswahlen/2025/ergebnisse.html (Accessed April 25, 2025).

Bündnis 90/Die Grünen. (2021). Deutschland. Alles ist drin: Bundestagswahlprogramm 2021. Available online at: https://cms.gruene.de/uploads/assets/Wahlprogramm-DIE-GRUENEN-Bundestagswahl-2021_barrierefrei.pdf (Accessed April 15, 2025).

Bündnis 90/Die Grünen. (2025). Zusammen wachsen: Regierungsprogramm 2025. Available online at: https://cms.gruene.de/uploads/assets/20250318_Regierungsprogramm_DIGITAL_DINA5.pdf (Accessed April 25, 2025).

Buzogány, A., and Scherhaufer, P. (2022). Framing different energy futures? Comparing Fridays for Future and Extinction rebellion in Germany. Futures 137:102904. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2022.102904

Cannavò, P. F. (2010). To the thousandth generation: Timelessness, Jeffersonian republicanism and environmentalism. Environ. Polit. 19, 356–373. doi: 10.1080/09644011003690781

Caspari, L., Otto, F., Schlieben, M., Schuler, K., and Reinbold, F. (2023). “Wir waren im absoluten Krisenmodus”: Der Bundestag hat das Heizungsgesetz verabschiedet. Aus dem Zukunftsprojekt wurde ein Albtraum für die Koalition. Rekonstruktion der Fehler und Missverständnisse. Zeit Online. Available online at: https://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2023-09/gebaeudeenergiegesetz-heizungsgesetz-bundestag-ampel-koalition (Accessed February 2, 2024).

CDU CSU, and SPD. (2025). Verantwortung für Deutschland: Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU, CSU und SPD. 21. Legilsaturperiode. Available online at: https://www.cdu.de/app/uploads/2025/04/Koalitionsvertrag-2025.pdf (Accessed April 25, 2025).

CDU, CSU. (2025). Politikwechsel für Deutschland: Wahlprogramm von CDU und CSU. Available online at: https://www.cdu.de/app/uploads/2025/01/km_btw_2025_wahlprogramm_langfassung_ansicht.pdf (Accessed April 25, 2025).

Chamayou, G. (2021). The Ungovernable Society: A Genealogy of Authoritarian Liberalism. Cambridge, MA: Polity.

Conversi, D. (2020). The ultimate challenge: nationalism and climate change. Nationalities Pap. 48, 625–636. doi: 10.1017/nps.2020.18

Cotta, B. (2024). Unpacking the eco-social perspective in European policy, politics, and polity dimensions. Eur. Polit. Sci. 23, 1–13. doi: 10.1057/s41304-023-00453-6

Cremer, J. C. (2024). Collective actors and potential alliances for eco-social policies in Germany. Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 34, 183–206. doi: 10.1007/s41358-024-00374-w

Detsch, C. (2024). SINUS-Studie für die Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Sozialökologische Transformation. Länderbericht Deutschland. Available online at: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/bruessel/20832.pdf (Accessed May 5, 2025).

Dingeldey, P. (2024). Eine nachhaltige Demokratie? Zum Freiheitsverständnis des grünen Republikanismus. Vorgänge. Zeitschrift für Bürgerrechte und Gesellschaftspolitik 245/246, 83–100.

Dodsworth, A. (2021). Republican environmental rights. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Polit. Philos. 24, 710–724. doi: 10.1080/13698230.2019.1698154

Dörre, K. (2022). “Zangenkrise und sozial-ökologischer Transformationskonflikt,” in Abschied von Kohle und Auto. Sozial-ökologische Transformationskonflikte um Energie und Mobilität, 2nd Edn, eds. K. Dörre, M. Holzschuh, J. Köster, and J. Sittel (Frankfurt am Main: Campus), 50–57.

Ekberg, K., Forchtner, B., Hultman, M., and Jylhä, K. M. (2023). Climate Obstruction: How Denial, Delay and Inaction are Heating the Planet. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003181132

Elsässer, L., Hense, S., and Schäfer, A. (2017). “Dem Deutschen Volke”? Die ungleiche Responsivität des Bundestags. Zeitschrift Für Politikwissenschaft 27, 161–180. doi: 10.1007/s41358-017-0097-9

FDP (2021). Nie gab es mehr zu tun. Wahlprogramm der Freien Demokraten zur Bundestagswahl 2021. Available online at: https://www.fdp.de/sites/default/files/2021-06/FDP_Programm_Bundestagswahl2021_1.pdf (Accessed April 5, 2025).

FDP (2025). Alles lässt sich ändern. Das Wahlprogramm der FDP zur Bundestagswahl 2025. Available online at: https://www.fdp.de/sites/default/files/2024-12/fdp-wahlprogramm_2025.pdf (Accessed April 05, 2025).

Federal Climate Action Act [Bundes-Klimaschutzgesetz - KSG]. (2024). Available online at: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_ksg/englisch_ksg.html (Accessed April 05, 2025).

Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action. (2023). Referentenentwurf: Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Änderung des Gebäudeenergiegesetzes und mehrerer Verordnungen zur Umstellung der Wärmeversorgung auf erneuerbare Energien. Available online at: https://wp.table.media/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/GEG-070323.pdf (Accessed April 5, 2025).

Finkeldey, J., Fischer, T., Theine, H., and Bohnenberger, K. (2024). The politics of Germany's eco-social transformation. Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 34, 124–136. doi: 10.1007/s41358-024-00389-3

Forsa. (2024). dbb Bürgerbefragung - “Öffentlicher Dienst 2024”: Der öffentliche Dienst aus Sicht der Bevölkerung. Available online at: https://www.dbb.de/artikel/70-prozent-halten-den-staat-fuer-ueberfordert-politik-muss-endlich-umsteuern.html (Accessed April 15, 2025).

Fremaux, A. (2019). “After the anthropocene,” in Green Republicanism in a Post-Capitalist World (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-11120-5

Fritz, M., and Lee, J. (2023). Introduction to the special issue: tackling inequality and providing sustainable welfare through eco-social policies. Eur. J. Soc. Secur. 25, 315–327. doi: 10.1177/13882627231213796

Gerstenberg, A. (2024). Ideas in transition? Policymakers' ideas of the social dimension of the green transition. Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 34, 137–159. doi: 10.1007/s41358-024-00375-9

Gough, I. (2017). Heat, Greed and Human Need: Climate Change, Capitalism and Sustainable Wellbeing. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. doi: 10.4337/9781785365119

Gough, I. (2022). Two scenarios for sustainable welfare: a framework for an eco-social contract. Soc. Policy Soc. 21, 460–472. doi: 10.1017/S1474746421000701

Grote, J. R. (2020). Civil society and the European Union. From enthusiasm to disenchantment. Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 32, 543–556. doi: 10.1515/fjsb-2019-0060

Haas, T. (2021). From green energy to the green car state? The political economy of ecological modernisation in Germany. New Polit. Econ. 26, 660–673. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2020.1816949

Haas, T., Sander, H., Fünfgeld, A., and Mey, F. (2025). Climate obstruction at work: right-wing populism and the German heating law. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 123:104034. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2025.104034

Hagemeyer, L., Faus, R., and Bernhard, L. (2024). Vertrauensfrage Klimaschutz: Mehrheiten für eine ambitionierte Klimapolitik gewinnen. Available online at: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/a-p-b/20941.pdf (Accessed February 2, 2025).

Hall, P. A., and Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/0199247757.001.0001

Hennis, W. (1977). “Zur Begründung der Fragestellung,” in Regierbarkeit: Studien zu ihrer Problematisierung (Vol. 1), eds. W. Hennis, P. G. Kielmansegg, and U. Matz (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta), 9–21.

Herberg, J., Luh, V., and Renn, O. (2024). Temporal injustice in Germany's coal compromise: industrial legacy, social exclusion, and political delay. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 117:103683. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2024.103683

Hermwille, L., Schulze-Steinen, M., Brandemann, V., Roelfes, M., Vrontisi, Z., Kesküla, E., et al. (2023). Of hopeful narratives and historical injustices - An analysis of just transition narratives in European coal regions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 104:103263. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2023.103263

Heyen, D. A., and Schmitt, L. (2024). Akzeptanzfaktoren klimapolitischer Maßnahmen: Synthese politisch relevanter Forschungsergebnisse und Schlussfolgerungen. Policy Brief. Öko-Institut e.V. Available online at: https://www.oeko.de/fileadmin/oekodoc/PolicyBrief-Akzeptanz.pdf (Accessed April 15, 2025).

Howe, P. (2017). Eroding norms and democratic deconsolidation. J. Democracy 28, 15–29. doi: 10.1353/jod.2017.0061

Huntington, S. (1975). “The United States,” in The Crisis of Democracy: Report on the Governability of Democracies to the Trilateral Commission, eds. M. J. Crozier, S. Huntington, and J. Watanuki (New York: University Press), 59–118.

Im, Z. J., de la Porte, C., Heins, E., Prontera, A., and Szelewa, D. (2024). A green but also just transition? Variations in social and industrial policy responses to industrial decarbonisation in EU member states. Global Soc. Policy 25, 64–85. doi: 10.1177/14680181241246763

IMF. (2025). Government expenditure, percent of GDP. Available online at: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/exp@FPP/USA/FRA/JPN/GBR/SWE/ESP/ITA/ZAF/IND (Accessed April 15, 2025).

Infratest Dimap (2023a). ARD-Deutschland Trend. Eine repräsentative Studie zur politischen Stimmung im Auftrag der ARD-Tagesthemen und der Tageszeitung DIE WELT, June 2023. Available online at: https://www.infratest-dimap.de/fileadmin/user_upload/DT2306_Report.pdf (Accessed February 2, 2024).

Infratest Dimap (2023b). ARD-Deutschland Trend. Eine repräsentative Studie zur politischen Stimmung im Auftrag der ARD-Tagesthemen und der Tageszeitung DIE WELT, July 2023. Available online at: https://www.infratest-dimap.de/umfragen-analysen/bundesweit/ard-deutschlandtrend/2023/juli/ (Accessed February 2, 2024).

Inglehart, R. F. (2021). Religion's Sudden Decline: What's Causing It, and What Comes Next? New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780197547045.001.0001

Jaeger, A. (2022). How the world went from post-politics to hyper-politics, Tribune. Available online at: https://tribunemag.co.uk/2022/01/from-post-politics-to-hyper-politics (Accessed February 11, 2024).

Jost, P., Mack, M., and Hillje, J. (2024). Aufgeheizte Debatte? Eine Analyse der Berichterstattung über das Heizungsgesetz - und was wir politisch daraus lernen können. Das Progressive Zentrum. Available online at: https://www.progressives-zentrum.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/240418_DPZ_Studie_Aufgeheizte-Debatte.pdf (Accessed February 03, 2025).

Kaase, M. (1984). The challenge of the “participatory revolution” in pluralist democracies. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 5, 299–318. doi: 10.1177/019251218400500306

Kielmansegg, P. G. (1977). “Demokratieprinzip und Regierbarkeit,” in Regierbarkeit: Studien zu ihrer Problematisierung (Vol. 1), eds. W. Hennis, P. G. Kielmansegg, and U. Matz (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta), 118–133.

King, A. (1975). Overload: problems of governing in the 1970s, Polit. Stud. 23, 284–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1975.tb00068.x

Klüh, N., Selk, V., and Knodt, M. (2024). Navigating the transition: unraveling the EU's different imaginaries for a just future. Futures 164:103483. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2024.103483

Knoche, A., Kaestner, K., Frondel, M., Gerster, A., Henger, R., Milcetic, M., et al. (2024). Fokusreport Wärme und Wohnen: Zentrale Ergebnisse aus dem Ariadne Wärme- und Wohnen-Panel 2023. Ariadne-Report. Potsdam: Kopernikus-Projekt Ariadne.

Koch, M. (2022). Social policy without growth: moving towards sustainable welfare states. Soc. Policy Soc. 21, 447–459. doi: 10.1017/S1474746421000361

Kortetmäki, T., and Huttunen, S. (2022). Responsibilities for just transition to low-carbon societies: a role-based framework. Environ. Polit. 32, 249–270. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2022.2064690

Kortetmäki, T., and Järvelä, M. (2021). Social vulnerability to climate policies: buildings a matrix to assess policy impacts on well-being. Environ. Sci. Policy 123, 220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2021.05.018

Koukoufikis, G., and Uihlein, A. (2022). Energy Poverty, Transport Poverty and Living Conditions—An Analysis of EU Data and Socioeconomic Indicators. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.