- 1Department of Political Science and International Relations, Bowen University, Iwo, Nigeria

- 2Department of Law, Safety, and Security Management, Tshwane University of Technology, Soshanguve South Campus, Pretoria, South Africa

Achieving meaningful development and success in any government endeavour will remain elusive without a robust and well-planned security architecture. Conducting credible, free and fair elections, guaranteeing the protection of election management officials and election materials, creating an enabling atmosphere for the electorate to cast their votes and ensuring that their votes count, are all possible within the framework of a safe and secured electoral environment. Observations have shown that security challenges in contemporary Nigeria are taking their tolls on the electoral process thus causing systematic disenfranchisement of the electorate, voter apathy, election manipulation, assaulting of election observers and destruction of their monitoring gadgets as well as the outright burning down of electoral management offices across the nation. It is against the foregoing that this article examined the implication of security challenges on election administration in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic that commenced in 1999. The study utilized qualitative research method with data gathered from secondary sources including books, journal articles, official government and non-governmental organisations’ documents, newspapers and internet materials while data were analysed using content analysis. The paper was anchored on state fragility as its theoretical framework. From its findings, the study showed that the underperformance of the election management body in Nigeria is compounded by the challenges of insecurity facing the nation including kidnapping, banditry and terrorism and exacerbated by the ineffectiveness of security agencies and their officials in addressing election insecurity in the country. The article concluded that a security unit be established within Nigeria’s election management structure to allow for long-term inclusive security mapping and planning as each election cycle unfolds.

Introduction

The centrality of security in election matters cannot be disputed as election administration demands safe and secured environment which is the fundamental responsibility of the state. The primary goal of any civilized society remains the enforcement of law and order by maintaining and guaranteeing the citizens general security (Adedayo, 2011). Security thus entails proactive measures and facilities that protect citizens, resources and properties from danger of violence, theft, sabotage, attack or subversion. This conceptualization is instructive because the primary purpose of government is to ensure the welfare and security of its people including the safety and protection to render their civic responsibilities. This makes election security an important subject of discourse in electoral matters. Security is an inseparable aspect of the electoral process, consequently, it is integral to achieving the goal of an election. It this sense, Olurode (2013) instructively wrote:

Security is indispensable to the conduct of free, fair and credible elections. From the provision of the basic security to voters at political party rallies and campaigns to ensuring that results forms are protected, the whole electoral process is circumscribed by security considerations. Thus, without adequate security, there cannot be credible, free and fair elections.

Observations have shown that security challenges in Nigeria notably terrorism, kidnapping, banditry and unabated political and ethno-religious violence are taking their tolls on the conduct of elections thereby causing systematic disenfranchisement of the electorate, voter apathy, election manipulation including ballot stuffing, ballot snatching, hijack of election materials and kidnapping of electoral officials. Other matters of security concern in the electoral process are lateness of electoral officials and election materials to voting centers, killing of voters and electoral officials, alteration and falsification of election results, assaulting of election observers and destruction of their monitoring gadgets as well as outright burning down of electoral management offices across the nation. This development seems to continue to weaken the integrity of elections and electoral processes in Nigeria as the will of the people becomes difficult to ascertain in electoral outcomes. This also copiously raises concerns over the seeming descendancy in the level of citizens’ engagement in electoral activities and the low level of confidence placed on democratic institutions to deliver credible elections.

To ensure electoral security, the role of security agencies and their personnel has been identified to be non-negotiable such that without them, the electoral atmosphere will become disorderly, unsafe, violent and anarchic (Yoroms, 2017; Mediayanose, 2018; Ali and Ali, 2022). However, the deployment of security agents for the purpose of securing the electoral process and activities has not guaranteed rancor-free elections since Nigeria’s return to party politics in 1999. Reports have shown that security agencies are compromised by political elites to achieve their parochial interests (National Democratic Institute, 2008; Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2015; YIAGA Africa, 2023). They are allegedly used by politicians to create palpable fear and tension to scare potential voters away particularly in the strongholds of the opposition. They have equally been accused of voters’ repression and intimidation and in some instances, they are used to supervise electoral frauds (YIAGA Africa, 2023). To complicate issues, electoral administration in contemporary Nigeria has suffered coordination problem as security agencies are embroiled in inter-agency rivalry bothering on who has the power to supervise the electoral process to the detriment of electoral integrity and democratic consolidation. Consequently, this study will be steered by two research questions namely (1) to what extent has security agencies been culpable in undermining election security in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic? (2) what are the underlying implications of election insecurity for election administration and democratic consolidation in contemporary Nigeria?

While studies on the underperformance of election management body in Nigeria have implicated the electoral umpire itself, this study adds to the frontiers of knowledge by expousing the unprofessional conduct of security agencies during elections and its attendant implication for election administration.

The study is structured into eight sections. The first is the introduction followed by conceptual discourse on key concepts in the study. The third section is the theoretical analysis while the fourth touches on methodology. The fifth is an overview of election insecurity in some democratic climes while section six is focused on security agencies and election administration in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic which underscores the utility of security agencies in election conduct and instances of culpability of security agents in election insecurity. The penultimate section dwells on the implication of insecurity for election administration and democratic consolidation in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic. The last section which is the eighth concluded the study and offered discernible recommendations.

Conceptual discourse

Election and election administration

In democratic settings, election is one of the building blocks for ensuring change of leadership. Election serves as a transition process in democratic systems and a way of strengthening political systems to become stable and viable for human progress and development. It is a process of acquiring political power by political actors to control state affairs in manners that instill public trust and confidence in the political cum democratic system. Election serves two critical purposes. First, it is a weapon of legitimizing government. By giving popular vote to a candidate or political party, authority is derived directly from the people and obedience to such government is voluntary. Second, it is a weapon in the hands of the citizens to “sack” and replace unpopular government, political party and their candidates from the saddle of leadership. It is the “red card” in the hand of a referee in a football match to a give a marching order to erring player(s). Election therefore provides the avenue and framework for persuasion, discussion, debate and common rules for selecting representatives of the people to serve in various institutions of government (Oni et al., 2017). Thus, an impartial and professional electoral umpire is a necessity to oversee the selection processes to avoid politicization. Electoral process comprises different stakeholders including the politicians, the electorate, local and international observers, security institutions, and Election Management Bodies (EMB), among others. The roles played by these respective stakeholders are coordinated by the EMB.

Election administration encompasses setting rules to organize and govern the electoral process as well as the implementation of such rules (Ejalonibu, 2019). It is the framework which regulates voting and electoral competition. In the words of the Election Administration Research Centre (2005), election administration simply focuses on voting and management of election at all levels. The task involves the organization of electoral structures, regulating the behavior and characters of election officials, the process of conducting elections and the implementation of election policies (Election Administration Research Centre, 2005). This connotes that election administration does not operate in vacuum. It operates within the framework of established laws, rules, guidelines, principles and regulations that develop from international law and conventions enhancing fundamental human rights and domestic laws within the tenets of international best practices on elections and democratic practice. To achieve desired results, adequate preparations are required in the administration of elections in terms of voters’ registration, procurement of necessary equipment particularly communication gadgets and logistical vehicles, voters’ education and sensitization as well as recruitment and training of poll workers (Oni et al., 2017). In the case of Nigeria, the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), is responsible for the registration and supervision of political parties, the conduct of elections up to the declaration of results. Elections in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic have been precarious causing voters to shun the polling booths due to security challenges while some electorates are systematically disenfranchised for the same reasons.

Security and election administration

Security is sine qua non for election administration. Security is approached from both conventional and contemporary forms. Traditionally or conventionally, the essence of election security is to protect the electorates, candidates, electoral officers, the press, observers, election materials, data, and infrastructure from death, damage, and destruction during elections (Nabiebu, 2022). Security is also needed in post-election activities like result collation, announcement and reactions to announcement. Security has become a serious issue in the electoral process in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic. Election insecurity has been aggravated by racial and religious tensions, poverty, political thuggery, weak law enforcement and corruption among others (Fadeyi and Akintola, 2023). All these culminate in electoral insecurity. Since independence, electoral security has been an integral part of the electoral system (Obiam, 2021). Election insecurity represents any act that compromises the safety of voters and election facilities perpetrated in the course of political activities before, during or after election (Fadeyi and Akintola, 2023).

Insecurity creates an atmosphere where voters are unable to make their electoral choice due to fear, difficulty in campaigning for candidates of their choice and hinder right to contest for election (National Democratic Institute, 2008). Thus, insecurity has been experienced in all stages in Nigeria’s electoral process. Insecurity could be perpetrated by state or non-state actors (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019; Faluyi, 2023). The involvement of state actors in acts of violence substantiates the reservations about the neutrality of state institutions in guaranteeing security. These acts of violence manifest through different ways. Elections have been threatened with forceful disruption of political meetings, destruction, manipulation or theft of campaign materials, detention, intimidation or disappearance of party candidates or supporters, detention, intimidation or disappearance of voters or civil society organization members, riots or protests and bodily harm or injury to anyone linked with the electoral process (Obiam, 2021). The other side of the coin is human security, precisely the issue of poverty. Political elites have weaponized poverty such that they use it to manipulate the masses to vote for them or the candidates they support (Faluyi, 2023; Nnabuife, 2024). Voters are induced with cash or material rewards to secure their votes. Poverty has also been a weapon to recruit political miscreants who are the foot soldiers for perpetrating electoral violence to compromise the security framework of elections before, during and after elections (Nwagwu et al., 2022; Faluyi, 2023).

Theoretical analysis

This study is anchored on state fragility theory. While there is the fundamental problem of understanding what state fragility represents because there is no universally acceptable conceptualization of the term, its meaning is aptly captured as a weakness or inability of the state to perform functions required and expedient to meet the needs and expectations of the citizens. It suggests the incapacity of a state to assure basic security, maintaining the rule of law and justice or providing basic services and economic opportunities for their citizens (Albert, 2011). According to the fragility speaks to the inability of a state to meet the expectations of their population or manage changes in expectations and capacity through the political process. Goldstone (2009) pointedly noted that fragile states are usually very weak in either the legitimacy or effectiveness of their state institutions or in both. He observed that there is a deterioration in state capacity especially on issues relating to the political system, the economy, provision of social services and basic security. Goldstone (2009) submitted that the political effectiveness of the system can be gauged from the angles of:

1. Whether or not elections in the country are free and non-violent

2. Whether the results are contested and

3. Whether the elections are judged to be improper and unfair by international observers

The author fundamentally observed that a state is fragile when one or more groups are systematically excluded from political access (Goldstone, 2009). This makes election security an important aspect of the electoral process because the fragility of a state is mostly revealed during elections (Albert, 2011). In Nigeria’s Fourth Republic, election seasons are often seen as endangered with no guarantee of security of lives and property of the citizens. Security challenges stemming from kidnapping, political thuggery, violence and terrorism often affect the administration of elections. For instance, the political violence that erupted in the Niger-Delta region of Nigeria during the 2003 general elections did not only disenfranchise electorate from performing their civic responsibilities, it further heightened insecurity in Nigeria as the thugs recruited by the politicians of the region later took up arms against the Nigerian state (Albert, 2011). Similarly, the National Union of Road Transport Workers crisis of 2007 was linked to politicians who recruited them to unleash terror against supporters of their opponents.

The strategic imports of perpetrating insecurity before, during and after elections are to affect electoral processes by disabling and disrupting opposing forces so as to emerge victorious at the polls, to weaken the voting strength of opposing camps by disenfranchising targeted population from registering during voters’ registration exercises, to prevent the normal circulation of voting materials to areas of strength of the opposing forces and to vitiate the elections generally by undermining the integrity of the election results. Insecurity, whether fueled by political thuggery, terrorism or kidnapping, their prevalence cannot be divorced from the weaknesses and incapacity of the state from exerting itself as an overarching authority armed to protect the citizens and prevent the duopoly of the use of force by centrifugal elements within the political system.

Methodology

The study adopted a qualitative technique by collecting data from relevant materials including journals, books, official government and non-governmental organizations’ documents, newspapers, and verified internet sources. The researchers searched for these documents using the Google Scholar, Web of Science, Google, SciELO, and EBSCO search engines. Even though the documents retrieved from these sources are a crucial source of data, the researchers carefully and critically examined every document to ensure that only relevant data are extracted particularly incidences that occur during the months of election campaigns and the actual week or day of voting. The credibility of authors’ works consulted and the verified outlets where they were published are criteria for drawing data from documented sources. Data drawn were mainly restricted to election related matters. The documents were subjected to content analysis before descriptively drawing valid inferences on security challenges and election administration in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic. The themes for the analysis reflected the realities on election matters in Nigeria and inferences were drawn from literature consulted.

Security challenges and election administration: global cases

Challenges during elections remain a global phenomenon even in the much-touted advanced democracies. For instance, the United States of America (USA) has been an epitome of democracy for centuries. However, there has been some developments in recent years that have brought some doubts about the democratic strength of the country. According to Asevameh et al. (2024), disinformation campaigns mostly through social media aimed at spreading false information and manipulating voter behavior have become a pervasive threat. The 2020 presidential election drew the attention of the globe to the country. Trump, the candidate of the Republican Party alleged that the ballots in the 2020 presidential election were changed, missing or stolen (Luke, 2023). Thus, after the election, trump was alleged to have incited the attacks on the Capitol on January 6, 2021 (Luke, 2023). Trump called on his political supporters to match to the Capitol peacefully and patriotically to make their voices heard. He ended his speech by informing his supporters to fight. This led to the attacks on the Capitol. Although, he later asked his supporters to remain peaceful and go home (BBC, 2023). The atmosphere also became charged toward the 2024 presidential elections. In the build-up to the 2024 presidential elections, there were attempts on the life of Donald Trump (Aljazeera, 2024; Vick, 2024).

Brazil has also been stared in the face with security threats to the electoral process. Historically, politically motivated violence has characterized elections in Brazil, with repeated targeting of political contenders and violent intimidation of voters throughout the democratic period (Election Watch, 2022). In a bid to influence election outcomes in their favor, politicians build pacts with criminal groups to assassinate political rivals and intimidate voters (Dierolf, 2018). These criminal groups also act on their own volition. For instance, Bolsonaro, a presidential candidate was stabbed and seriously injured during a campaign rally on 6 September 2018 in Juiz de Fora city, Minas Gerais state (Election Watch, 2022). Also, on 14 March of the same year, suspected members of a militia assumed to have political ties shot and killed Marielle Franco, a human rights defender and Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL) councilwoman in Rio de Janeiro city’s Central Zone (Election Watch, 2022). Militias and drug trafficking groups deploy violence to daunt candidates who pose a threat to their activities, as witnessed ahead of the country’s 2020 local elections (Election Watch, 2022). The 2022 presidential election in Brazil was fierce and distinct from previous elections since re-democratization. The 2022 Brazilian election was characterized with the spread of distrust, violence, high electoral volatility, and high party fragmentation (Tarouco, 2023). The electoral activities were characterized with polarization, violence, fake news, conspiracy theories and spreading of hate speech among citizens and candidates (Tarouco, 2023). Drug trafficking groups were also involved in political attacks including shooting and inflicting injuries on Brazilian Labor Party (PTB) councilman Wemerson Barriga in Itacoatiara city, Amazonas state (Election Watch, 2022). The slim victory of former president Lula over Bolsonaro generated a hostile environment between supporters of both actors (Tarouco, 2023). Presidential offices, the Congress and Supreme Court buildings were invaded in post-election violence (Tarouco, 2023).

Kenya has equally experienced security challenges in its elections. Kenya African National Union (KANU) ruled from 1963 and remained in power until 2002 (Dercon and Gutiérrez-Romero, 2012). The 1992 and 1997 elections were won by KANU with serious violence and electoral irregularities witnessed in both elections (Laakso and Kariuki, 2023). The post-KANU elections have also been subjects of security scare. The monitored media sources account for 1,127 people killed because of electoral violence from the Election Day on 27 December 2007 until 29 February 2008 (Dercon and Gutiérrez-Romero, 2012). Few incidents of electoral violence were recoded before the Election Day. Most of these incidents were in small towns and recorded during political rallies (Dercon and Gutiérrez-Romero, 2012). These acts of violence included disruption of campaign rallies, threats of violence to aspirants and supporters of parties, and direct violence on candidates and supporters with cases of reported killings among others (Dercon and Gutiérrez-Romero, 2012). The declaration and swearing in of Kibaki on 30 December 2007 led to political crisis. This took the form of ethnic attacks in different parts of the country (Ksoll et al., 2021). Majority of these deaths were linked to politically connected gangs such as Mungiki (Dercon and Gutiérrez-Romero, 2012). The 2007–08 election violence generated fears of a likely violence in 2012 elections, the violence recorded was far less compared to those of the 2008 post-election violence (Adebayo and Makwambeni, 2019). Prior to the 2012 elections, inter-ethnic violence between unemployed youths engaged by rival politicians occurred in some areas (Barkan, 2013).

Similarly, Zimbabwe has been dominated by a party- Zimbabwe African National Union- Patriotic front (ZANU-PF) since its independence in 1980. This party is the. In a bid to retain its control of the country, the party has promoted violence as a tool (Makonye et al., 2020). There was also intra-party scheming to hold on to power. The ruling party has been accused of using the military to perpetrate violence by intimidating the opposition and punishing the geographical areas that did not vote for them (Tirivangasi et al., 2021). The ruling party has also used war veterans, ZANU PF youth Group (militia) and the police to intimidate the opposition (Cheeseman, 2011, p. 349; Tirivangasi et al., 2021). Some of these “measures” have been applied since the administration of Mugabe. For instance, it was alleged that former President Mugabe destroyed the houses of people in MDC strongholds because they did not vote for him in the 2002 presidential election (Makonye et al., 2020). The militarization of elections by appointing members of the military elite class into key positions including the membership of the electoral commission fueled pre- and post-election violence in Zimbabwe (Makonye et al., 2020). There were also reported cases of murder of some opposition Movement for Democratic Change supporters and activists (Makonye et al., 2020).

The foregoing discussion points to the fact that different countries witness different forms of election insecurity with Nigeria not an exception. The need to study election insecurity in Nigeria and its impact on election administration is fueled by the narratives that indict the electoral umpire in Nigeria for the many woes that bedevil Nigeria’s electoral process. While similar efforts have been undertaken to examine how political parties and party indiscipline undermine election administration in contemporary Nigeria (Oni, 2024), this study is another attempt to espouse the culpability of other stakeholders in election maladministration witnessed in Nigeria since its return to party politics in 1999. The focus on security agencies and their personnel is informed by the persistence of their culpabilities in election maladministration from the reports of both local and international election observers after each election cycle.

Security agencies and election administration in Nigeria’s fourth republic

As part of the procedures for election conduct in Nigeria, security personnel are deployed to various voting centers to ensure the maintenance of law and order. The agencies whose services are engaged include the Nigeria Police Force, the Military, Department of State Services (DSS), Nigeria Security and Civil Defense Corps (NSCDC), Federal Road Safety Corps (FRSC), and the Nigeria Immigration Service (NIS), among others. The Police is usually the lead agency among the security stakeholders. The duties of the Police and Military in elections have been defined to be logistics and protection (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019). An information obtained from the INEC website indicates that the NIS collaborates with INEC in identifying non-Nigerians whose names might have been “included’ in the voters” registers. The same website provides that one of the roles of the DSS is to investigate the conduct of INEC staff, ad hoc electoral officials and security agents during elections. The DSS also provides intelligence reports on the feasibility or otherwise of elections based on security threats. The role of the FRSC includes enforcement of no movement order, checking if INEC vehicles used in conveying electoral materials are in good conditions, removal of obstructions and participation in rescue operations and collaboration with other security agencies to maintain orderliness in polling booths (Opara, 2020). The role of the NSCDC in the electoral process is to protect vital national assets and infrastructure during elections and secure election materials during and after elections as well as cooperate with other security agents to ensure peaceful elections (Ajayi, 2024). The essence of the involvement of these security institutions and other security agencies is to guarantee safety, curtail vote buying and forestall violence.

Despite the retinue of security agencies assigned responsibilities for smooth electoral process, election insecurity remains a major setback to electoral success in Nigeria. It is worrisome that the massive deployment of security institutions and their agents has not stemmed the tide of electoral insecurity in Nigeria. These state institutions have also performed below expectations either due to incompetence or taking sides with a political party or group. They are on many occasions overwhelmed with troubles that emanate from the electoral process (Rosenau et al., 2015).

Since the inception of the Fourth Republic in May 1999, the Military, the DSS and the Police have been stained with allegations of aiding the incumbent governments by disrupting elections at opposition strongholds, deliberately delaying the delivery of ballot material to opposition strongholds, ignoring violence and intimidation of voters, and in some cases, being the masterminds of violence and intimidation against voters, opposition members and their agents including unlawful arrests and detention in the run up to elections and on election day (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019). They are sometimes involved in electoral violence, using their positions to harass and intimidate voters that have links with parties that are in opposition to the candidate who has the highest price for their loyalty (Rosenau et al., 2015). Furthermore, the police have been allegedly accused of failing to arrest and prosecute political thugs and those that contravene electoral laws and disorganize the electoral process (Tobi and Oikhala, 2018). This explains why one may conclude that the institution’s neutrality has been compromised.

To have a holistic grasp of the security situations during elections in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic and the role security agencies played in the situations, it is salient to have a chronological overview of elections from 1999 to 2023. The 1999 general elections, the first in the current democratic journey, were less violent due to the seeming elite consensus that the military should return to the barracks hence politicians across different party lines relatively played by the rules of the game to avoid any annulment of the electoral process as seen in 1993 (The Carter Center and National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, 1999). Relatedly, politicians were not as advanced as they are recently in vices such as vote buying, voter intimidation, the use of security personnel to grease rigging, falsification of election results and so on (The Carter Center and National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, 1999; Magaji and Musa, 2022). At another level, the political class less envisaged that political offices will be as lucrative as they are in the country. The 2003 election was the first civil to civil transition to power after the commencement of the Fourth Republic. Political elites were more interested in participating directly in politics because they began to face the reality of the less likelihood of military’s incursion into politics. Considering the paraphernalia that comes with political offices, political elites became more interested in vying for political offices. The ruling parties at the national and state levels were also keen on retaining power. These made the atmosphere of the electoral process tensed. Hence, security became a serious concern. Therefore, pre-election flaws like high prevalence of violence mainly during party primaries and defects in the voter registration and voter education process became common issues (Le Van et al., 2003). Undoubtedly, these problems helped create an unstable climate for the elections. Toward the election, there were killings of political and non-political opponents as well as physical attacks against aspirants for political offices and their supporters (Le Van et al., 2003). There was election violence is some states to the extent that elections in these states were postponed and/or rescheduled (Le Van et al., 2003). The 2003 presidential election was characterized by obvious rigging, thuggery, intimidation, and manipulation of the electoral process (Obiam, 2021). Accusing fingers were pointed at security agents as they could not prevent some of these violent acts and they were allegedly directly involved in thwarting free and fair elections in some places. It was alleged that the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) used security agents to rig the 2003 elections (Ajayi, 2006).

The 2007 general election was in no way better in terms of security. The quest of the political class to participate more in politics and the efforts of the opposition parties especially the All Nigeria Peoples Party to wrestle power from the ruling PDP boosted the political storm that shook the 2007 general elections. At the state level, governors did not want the opposition parties to capture their states thus deploying the incumbency power to win elections at all cost. Meanwhile, opposition parties were keen on taking power from the ruling parties in various states. The atmosphere became politically tensed that the incumbent President despite being in the latter days of his second and final term in office, through his utterances and actions, was determined to retain power for the ruling PDP at the national and state levels. Former President Olusegun Obasanjo thus declared that the 2007 election was a “do or die affair,” which can be interpreted as an impetus for his supporters to weaponise violence and rigging to secure electoral victory (Yoroms, 2017; Bekoe, 2011). These attitude and statement among other factors consolidated the insecure cloud over the elections.

On a number of occasions, candidates belonging to the opposition parties in some states were arrested and whisked to Abuja by security agents, which had negative effects on their preparations for the elections and frightened their supporters (National Democratic Institute, 2008). There were intra and inter party acts of violence and pre-election acts of violence, including political assassinations, killings and armed clashes between rival political factions (National Democratic Institute, 2008; Ogele, 2020). In some parts of the country, violence restricted the capability of parties and candidates to freely campaign or conduct other electoral activities (National Democratic Institute, 2008). In the same vein, there were intimidations of potential voters to sway their choice at the polling centers; and there were attacks carried out at/against polling stations, polling officials and rival party agents (National Democratic Institute, 2008). Furthermore, there was low secrecy in balloting coupled with ballot box stuffing and snatching and killings of civilians (National Democratic Institute, 2008). In some states where thugs invaded some polling stations, seized ballot boxes and scared away voters, security officials were just standing by (National Democratic Institute, 2008). The “incapacitation” of the police signaled to the people that if the police could act in such a manner, they were more vulnerable to attacks by political thugs. The excessive deployment of the military and other security personnel exacerbated voters’ fears and ironically failed to guarantee safety and security (National Democratic Institute, 2008). Voters’ fears increased because they had the feeling that the security operatives may be working in the interest of candidates that are not their choice. Hence, they may incur the wrath of the security officials if they fail to align with their principals’ political interests.

The acknowledgement by late President Yar’Adua that the election that ushered him into power as the president in 2007 was not free and fair and the setting up of the Justice Uwais Committee placated the people on their distrust in the country’s electoral system. The 2011 presidential election was mild majorly at the federal level before and during the elections. At the state level, each state had its peculiarity as some governors wanted to retain their positions while some wanted to ensure that their political mentees took over from them. This “win at all cost syndrome” heightened the palpable fear and tension that greeted the elections as many sitting Governors particularly those that belonged to the ruling party at the federal level state utilized security apparatuses to gain control of the electoral process. Again, the differences between the North and the South on who becomes the president hunted the country in 2011 as the country experienced devastating post-election violence.

The 2011 post-election violence in some Northern states where about 800 people died and about 65, 000 displaced was far greater than pre-election and election day acts of violence recorded (Bekoe, 2011). The post-election violence had effects on the political climate in the build-up to the 2015 election activities. It also decimated the trust of the people in the capacity of state institutions particularly security agencies to prevent and respond to violence. The attempt by the incumbent, Goodluck Jonathan to retain his position and the moves by his opponent, Muhammadu Buhari to wrest power from him created a security tensed electoral atmosphere. The North was keen on taking back power because it felt it has had a lesser share in the rotational presidency between the north and the south as at 2015. From 1999, the South had ruled for 13 years while the North had ruled for 3 years.

The 2015 electoral process was characterized by hate speeches, slandering, victimizations, intimidations, killings and destruction of property (Obiam, 2021). Some of these were directly linked to the activities of the political class in connivance with security agencies who became partisan and unprofessional in handling security threats and deficient in intelligence gathering. In January and February 2015, there were bomb blasts in Rivers and Gombe States, respectively (Rosenau et al., 2015). There were attempts to subvert the electoral and democratic process as supporters of incumbent President Jonathan brazenly disrupted the National Conference Center in Abuja where results of elections were collated having sensed that their principal was about to lose the election. The ensuing security situation would have been catastrophic if not for the courageous and timely phone call President Jonathan put across to Muhammadu Buhari to congratulate him. The post-election security situation did not pose much threat because Buhari emerged the winner, thus a repeat of the 2011 post-election violence in the North was averted. The security situation in the country did not improve between 2015 and 2019. Boko Haram and the Islamic State West Africa Province posed major threats to the 2019 elections (International Crisis Group, 2023).

As the 2019 elections were approaching, supporters of the All Progressives Congress and the PDP clashed which ignited violence across the country (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019). Political elites were not considerate in their utterances as these had the potentials of fueling political violence. For instance, former Governor El-Rufai threatened that any foreigner who intervenes in Nigeria’s election should be ready to be returned back to their countries in body bags (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019). If foreigners could be threatened in that manner, any voter who valued his life may decide to stay away from voting with the prevalent level of threats that pervaded the polity. The President, in response to the threats, declared that those that snatch ballot boxes would pay with their lives (Agbakwuru and Ajayi, 2019). He directed security personnel to deal ruthlessly with party thugs that attempted to snatch ballot boxes (Agbakwuru and Ajayi, 2019). This literally sent a strong signal to perpetrators of violence to desist. However, the presidential order worsened the security situation during the elections considering the history of human rights abuses associated with Nigeria’s security agents. Notably, the security situation was bad, especially on the days of the election despite the heavy deployment of security personnel.

The 2019 elections were militarized and security personnel were deployed without clear coordination with INEC (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019). There was partisan involvement of the military, the DSS and police in the elections (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019). The large presence of security personnel was perceived by the public as an attempt to intimidate voters and this heavy deployment did not prevent violence which resulted in deaths and attacks on INEC facilities (Amao and Ambali, 2022). In some parts of the country, security personnel were unable to check incidents of violence, intimidation of voters, ballot box snatching and destruction (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019). About 27% of polling units were not provided with adequate security and they were made vulnerable to disruptions (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019). INEC officials were intimidated by security officials before voting, during voting and during collation of results (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019). An INEC staff was shot dead by security agents in Rivers State (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019). Journalists in Rivers and Plateau were kidnapped but later released (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019). To worsen the situation, fight for supremacy between the police and personnel of the Nigerian Army ensued at INEC office during the collation of the 2019 election results in Rivers State. The clash was mainly on who should be in charge of security at the INEC office during the period, a development that speaks largely to the problem of coordination in election security in Nigeria. This caused panic for INEC staff and other election stakeholders. With the apparent division between these two security agencies, it will certainly be difficult to cooperate to improve election security in the country.

Security issues remained a challenge in the activities toward the 2023 elections. The 2023 elections were characterized by violent political rivalry coupled with existing Nigeria’s security challenges before, during and after the elections (YIAGA Africa, 2023). Violent non-state actors increased their terror toward the elections. There was voter suppression as some voters were denied the opportunity to register to vote in some areas in the South West and South East. Thuggery, snatching and destruction of election materials, and attack on polling officials were reported in the 2023 electoral process (Independent National Electoral Commission, 2024). On the election day, there was disruption of voting, intimidation of voters, attacks on election observers and the media, election officials, Economic and Financial Crimes Commission officials and destruction of election materials and other forms of violence in some states (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2023; YIAGA Africa, 2023). Election materials were hijacked and there were also fatalities during the election (YIAGA Africa, 2023). Voters were profiled based on political affiliation or ethnic identity and consequently denied the privilege to access polling units to vote (YIAGA Africa, 2023). Some voters were deliberately denied the right to vote in some states in a bid to whittle their voting strength and power as a group (YIAGA Africa, 2023). There was adequate deployment of security personnel in most polling stations but they could not contain the activities of hoodlums in some polling stations (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2023). Although security agents responded to violence in some instances. For instance, thugs stormed Atani I Ward in Ogbaru LGA of Anambra State and bade to hijack ballot boxes but they were arrested by personnel of the Nigerian Army (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2023). This incidence disrupted voting in the area (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2023). An obvious instance where they could not prevent intimidation of voters was in Uzebu Ward, Oredo LGA, Edo State where thugs took control of Owegie Primary School 1 Polling Unit and forced the few voters who showed up to vote to display their ballot papers after thumb printing (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2023). This was against the set standard that votes should be cast in secrecy.

There was also post-election intimidation and violence. In some local governments in Rivers and Benue States, election observers were denied access to collation centers (YIAGA Africa, 2023). During the collation of governorship election results in the two states, thugs attacked collation centers and unruly party agents interfered with the collation process thus fueling the question on the whereabouts of security personnel in the process (YIAGA Africa, 2023). Security personnel were also unruly during the collation of results. The exercise had to be put on hold in Taraba State after soldiers killed two policemen over an attack on a soldier (John, 2023). Soldiers also harassed policemen escorting election results in some parts of the state (John, 2023). In sum, security agencies and their personnel have been indicted in election maladministration in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic owing largely to their partisanship, indifference and unprofessionalism.

Insecurity, election administration and democratic consolidation in Nigeria’s fourth republic

Arguably, the maladministration of elections witnessed in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic cannot be divorced from the security challenges confronting the country and weak state institutions with debilitating effects on democratic consolidation. Notably, insecurity and various forms of criminality have affected the operational procedures of the election management body in Nigeria as INEC is systematically decapacitated from performing its constitutional role. High level of criminality translates into coordinated attacks on INEC staff, offices, property and materials on many occasions during elections (International Crisis Group, 2023; Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2023; YIAGA Africa, 2023). It is worrisome to note that criminals attacked INEC offices 50 times in 15 of the country’s 36 states from 2019 to 2022 (International Crisis Group, 2023). As a result of insecurity, INEC could not register new voters in some local governments in the North East, North West and North Central zones, and it was unable to issue voters cards to many of the over 3 million internally displaced people in the troubled areas of northern Nigeria during the period (International Crisis Group, 2023). In April 2022, due to several physical attacks, INEC had no choice but to suspend voter registration in three local government areas of Imo state namely – Njaba, Orsu and Ihitte Uboma (International Crisis Group, 2023).

On the basis of the above therefore, election insecurity has continued to inadvertently increase voters’ apathy thereby reducing popular participation, the fundamental tenets upon which democracy rests. Voters’ turnout continues to diminish in each election cycle thus questioning the utility of elections as a means of changing power and government in contemporary Nigeria. Lack of popular participation has meant that the selection of leaders who govern and manage state affairs has been left in the hands of a few thus the concept of “selectoracy” replaces “electocracy” as unpopular candidates emerge from election contests with dire implications for good governance. Instructively, lack of good governance has been identified as a threat to democratic consolidation in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic (Oni et al., 2017).

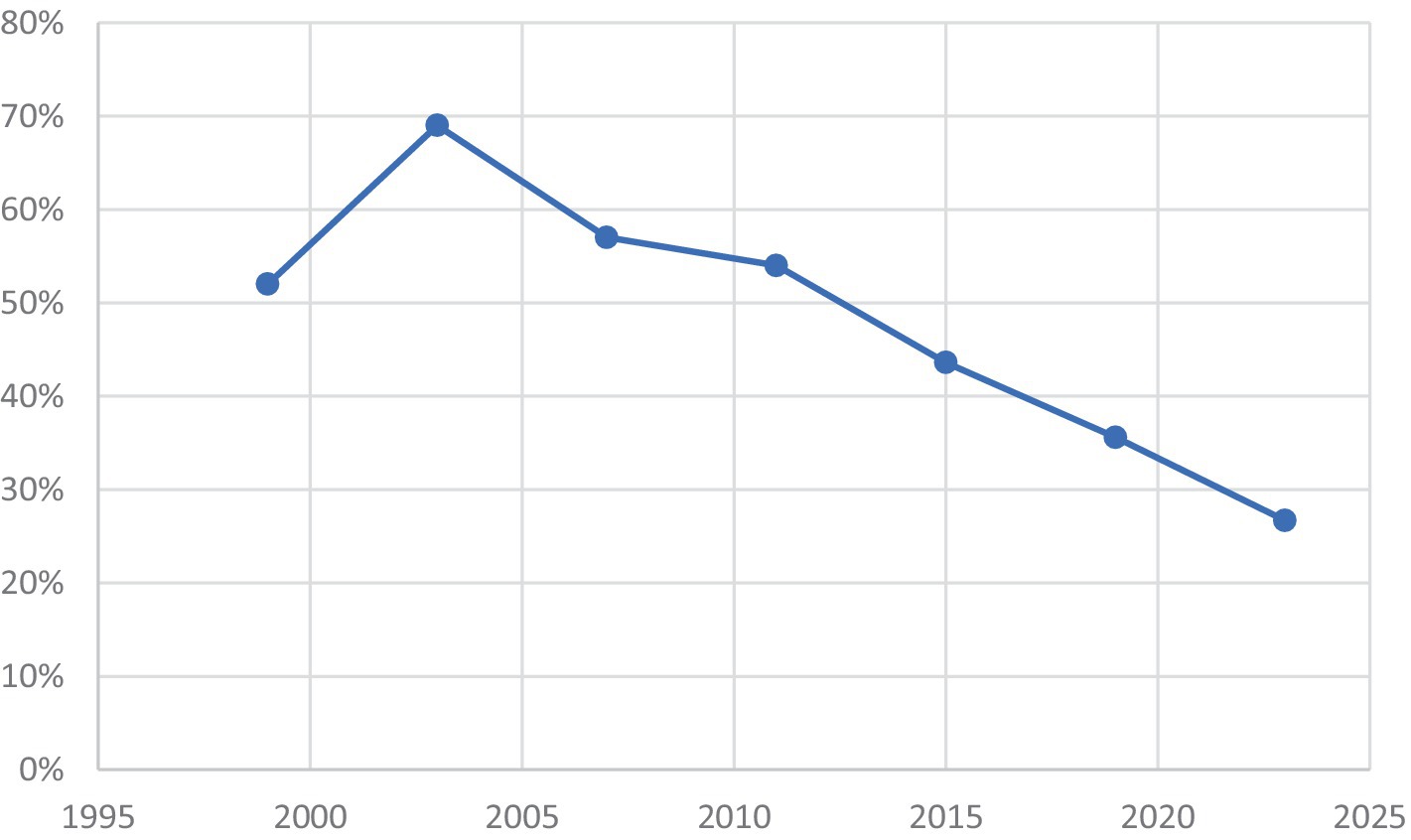

It is noteworthy that the overall voter turnout for the presidential elections has been nosediving due to security challenges and the underperformance of the security institutions since 1999 except for 2007. Figure 1 below gives a description.

Figure 1. Voter turnout of presidential elections from 1999 to 2023 Sources: Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room (2015), Obiam (2021), and YIAGA Africa (2023).

It was 52% in 1999, 69% in 2003, 57% in 2007, 54% in 2011 and 43.6% in 2015. The official voter turnout for the 2019 presidential election was 35.6% while that of the presidential and National Assembly election in 2023 was 26.7%. It is preposterous that the people electorally empowered and saddled with the responsibility of appointing political leaders and managers of state affairs including its resources continue to nosedive in number since 1999 except for 2003. Arguably, the low turnout in 1999 could be adduced to the manner in which the June 12, 1993 presidential election was annulled. Nigerians still doubted the sincerity of the country’s leadership to mid-wife an election that will reflect their will without circumventing the process and its outcome. However, it was expected that the higher turnout in 2003 will be sustained but weak election security has continued to worsen the situation.

Democracy has suffered severe attacks since Nigeria’s return to party politics in 1999 particularly during elections leading to the youths and some sections of Nigerians calling for the return of military rule due to election insecurity, poverty and bad governance (Orebe, 2024). The political values of regular and periodic elections in Nigeria remain in question since those elections come at the cost of citizens’ lives. To be sure, about 100 people were killed in the 2003 elections, about 300 were killed in 2007, in 2015, 106 people were killed while from the campaign period in October 2018 until the final election in March 2019, at least 626 people were killed (Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, 2019). Aside the post-election violence that led to the death of about 800 people in 2011 (Bekoe, 2011), there were pre-election cases of assassinations. These killings, attacks and other forms of political violence contributed to the swelling voter apathy in the country’s general elections. Specifically, increased cases of kidnapping and threats by militant groups reduced citizen participation in the 2007 elections in the Niger Delta area (National Democratic Institute, 2008). Uncontrolled activities of insurgents, bandits, herdsmen, and other violent non-state actors contributed to the low turnout of voters from 2015. Insecurity has heightened the creation of armed groups whose activities span beyond the election season. Observably, opposition political elites float armed or sponsor armed groups to provide security for themselves and act as parallel security officials before and during elections (Ajayi, 2006). Sadly, politicians supply arms to these political thugs and once elections are over, they are usually discarded thus embrace crime and violence to survive.

Since the electorate continue to observe that their votes do not count, their confidence in democracy has consistently dropped because unpopular candidates fraudulently emerge as winners. This is evident in the number of post-election litigations where the courts have unraveled fraudulent means by which candidates emerge winners at the polls (Oni, 2020). This reason and some others account for why some sections of the society canvass for military takeover of power at some point in the nation’s current democratic journey arguing that the country’s democratic system lacks substance and that the use of violence and guns to win elections is worse than the use of force by the military to take over power (Ajayi, 2006; Yoroms, 2017). Invariably, election insecurity has nosedived the trust of the electorate and the entire citizenry in democracy since they continue to be disenfranchised using the instrumentality of fear, intimidation and manipulations with security agents complicit in the process. In this sense, democracy will be easily subverted since citizens are disempowered in securing and defending democratic institutions thus democratic relapse and descent to military rule may become unpreventable.

It is worrisome that election administration in Nigeria has also been affected by ethnic politics. Since elections in Nigeria are still largely determined by primordial sentiments including religion, tribalism or ethnicity and regionalism, the security apparatuses in Nigeria are not immune from them. Elections in Nigeria have been largely inspired by ethnic and religious permutations as visibly evident in the 2011, 2015 and 2023 presidential elections. As observed during military regimes in Nigeria, the military institution supposedly homogenous and unifying in nature, character and purpose also fell into the web of primordialism particularly ethnic politics, which affected its corrective missions in the body politic of Nigeria. Security agencies in Nigeria become politicized by political elite to satisfy personal and regional ambitions thus blinding them to their professionalism, neutrality and national loyalty. This ignoble practice weakens the capacity of security agencies for proactive actions toward intelligence gathering and rapid response to threat or use of violence before, during and after elections.

Conclusion and recommendations

This study has critically examined the place of security in election management and emphasized that security, defined in terms of safety and protection of lives of the electorate, election management officials, election materials and other critical stakeholders during the election season, is sacrosanct for political stability and democratic sustenance. The study identified insecurity as one of the causal factors of election maladministration and noted that the phenomenon bedevils Nigeria’s electoral process in two ways. First, is the unprofessional conduct of security agencies and their agents as they are complicit in perpetrating the oppression of voters and in some cases used to supervise electoral fraud. Security agencies have been noted to become ethicized and politicized by political elites using incumbency and primordial attachments. The study also observed that security agents are not immune from primordial cleavages hence their submission to be used by politicians for parochial and sectional interests. More worrisome is the inter-agency rivalry among top security agencies namely the Army, the Police and the DSS over supervision responsibilities during election periods. The lack of coordination among these security agencies has continued to exacerbate insecurity, dampen the enthusiasm of electorate to perform their civic responsibility to vote and reduce the efficiency of the election management body.

On the other hand, various criminal activities in the country chiefly kidnapping, farmer-herders’ conflicts, terrorism and banditry have reduced elections in Nigeria to a game of the few as the fear of being killed, attacked or kidnapped undoubtedly reduces voters’ turnout in each election cycle. Insecurity of this nature did not exempt the officials of the INEC and local and international election observers. There have been cases of attack against these officials, some were kidnapped and some killed. These heinous criminal tendencies affect the operational procedures of elections as well as the overall performance of INEC. The study submits that insecurity has telling implications on governance and democratic sustenance. The study also notes that security is not a one-off activity during election processes. It suggests that INEC should, as a matter of policy, incorporate security into the whole election architecture of the country by establishing a security unit within the INEC operational structure for planning, mapping and intelligence before each election cycle. Instructively, election is a civil activity thus is better supervised by the police which has the constitutional mandate for maintaining law and order. The security unit within INEC should accommodate officials of various relevant security agencies and headed by a competent and experienced police officer to coordinate security activities and responsibilities. This measure will improve intelligence gathering and proactive response to election threats ahead of time thereby improving election integrity and democratic sustenance in Nigeria.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

EO: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. OF: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LA: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AO: Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Bowen University, Iwo, Nigeria and the Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria, South Africa. We also appreciate the editors of Frontiers in Political Science for their comments and feedback.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adebayo, J. O., and Makwambeni, B. (2019). The limits of peace journalism: media reportage of Kenya’s 2017 general elections. J. Afr. Elect. 18, 69–85. doi: 10.20940/JAE/2019/v18i1a4

Adedayo, A. (2011). “Elections and Nigeria’s National Security,” in Democratic elections and Nigeria’s National Security, eds. I. O. Albert and N. L. Danjibo, Isola, O. O. and. Faleti, S. (Ibadan: John Archers Publishers Ltd.), 23–46.

Agbakwuru, J., and Ajayi, O. (2019). Snatch ballot box, pay with your life, Buhari declares. Available at: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2019/02/snatch-ballot-box-pay-with-your-life-buhari-declares/ (Accessed May 14, 2024).

Ajayi, K. (2006). Security forces, electoral conduct and the 2003 general elections in Nigeria. J. Soc. Sci. 13, 57–66. doi: 10.1080/09718923.2006.11892531

Ajayi, O. (2024). NSCDC deploys 6,433 personnel for Edo election. Available online at: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2024/09/nscdc-deploys-6433-personnel-for-edo-election/ (accessed September 18, 2024).

Albert, I. O. (2011). “Elections and state fragility in Nigeria’s fourth republic.” in Democratic elections and Nigeria’s National Security, eds. I. O. Albert and N. L. Danjibo, Isola, O. O. and. Faleti, S. (Ibadan: John Archers Publishers Ltd.), 23–46.

Ali, J. M., and Ali, S. D. (2022). An analysis of the role of security agencies in the management of electoral violence in Nigeria’s fourth republic. Zamfara J. Politics Dev. 3, 1–14.

Aljazeera (2024). US Sheriff says ‘probably prevented’ third Trump assassination attempt. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/10/13/us-sheriff-says-probably-prevented-third-trump-assassination-attempt (accessed January 14, 2025).

Amao, A. I., and Ambali, A. (2022). Electoral integrity, voters’ confidence and good governance in Nigeria: a comparative analysis of 2015 and 2019 presidential elections. J. Admin. Sci. 19, 39–65.

Asevameh, I. O., Dopamu, O. M., and Adesiyan, J. S. (2024). Election infrastructure security: a review of vulnerability and impact on the U.S. economic reputation. World J. Adv. Eng. Technol. Sci. 12, 233–244. doi: 10.30574/wjaets.2024.12.1.0212

Barkan, J. D. (2013). Electoral violence in Kenya. Manhattan, NY: Council on Foreign Relations, Center for Preventive Action.

BBC (2023). Capitol riots timeline: what happened on 6 January 2021? Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-56004916 (accessed January 14, 2025).

Bekoe, D. (2011). Nigeria’s 2011 elections: best run, but most violent. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

Cheeseman, N. (2011). The internal dynamics of power-sharing in Africa. Democratization 18, 336–365. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2011.553358

Dercon, S., and Gutiérrez-Romero, R. (2012). Triggers and characteristics of the 2007 Kenyan electoral violence. World Dev. 40, 731–744. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.09.015

Dierolf, J. G. A. (2018). Criminalized electoral politics: The socio-political foundations of electoral coercion in democratic Brazil (Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame.

Ejalonibu, G. L. (2019). Ecology of election administration and the performance of electoral management body in Nigeria's fourth republic. Soc. Sci. Law J. Policy Rev. Dev. Strat. 7, 21–45.

Election Administration Research Centre (2005). What is Election Administration? Available online at: https://earc.berkeley.edu/about.html (accessed April 25, 2024).

Election Watch (2022). Political violence during Brazil’s 2022 general elections. Available online at: https://acleddata.com/2022/10/17/political-violence-during-the-brazil-general-elections-2022/ (accessed January 14, 2025).

Fadeyi, O. I., and Akintola, O. I. (2023). Addressing election insecurity in Nigeria: strategies for a secure electoral process. Multidisciplinary J. Voc. Educ. Res. 5, 78–86.

Faluyi, O. T. (2023). National integration and rotational presidency in Nigeria: Setting the ‘rules’ of integration in a plural state. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Goldstone, J. A. (2009). Deteriorating fragile states: How to recognize them, how to help them. Hopewell, VI: School of Public Policy, George Mason University.

Independent National Electoral Commission (2024). Report of the 2023 general election. Abuja: Independent National Electoral Commission.

International Crisis Group (2023). Mitigating risks of violence in Nigeria’s 2023 elections. Brussels: International Crisis Group.

John, B. (2023). Two policemen killed as Army, police clash in Taraba. International Centre for Investigative Reporting. Available online at: https://www.icirnigeria.org/two-policemen-killed-as-army-police-clash-in-taraba/ (accessed May 13, 2024).

Ksoll, C., Macchiavello, R., and Morjaria, A. (2021). Guns and roses: flower exports and electoral violence in Kenya. Global Poverty Research Lab Working Paper. 17–102. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3126456

Laakso, L., and Kariuki, E. (2023). Political science knowledge and electoral violence: experiences from Kenya and Zimbabwe. Forum Dev. Stud. 50, 59–81. doi: 10.1080/08039410.2022.2112280

Le Van, A. C., Pitso, T., and Adebo, B. (2003). Elections in Nigeria: is the third time a charm? J. Afr. Elect. 2, 30–47.

Luke, T. W. (2023). Democracy under threat after 2020 national elections in the USA: ‘stop the steal’ or ‘give more to the grifter-in-chief?’. Educ. Philos. Theory 55, 551–557. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2021.1889327

Magaji, M., and Musa, U. A. (2022). Vote-buying and the electoral process in Nigeria: trends and challenges, 2015-2019. Zamfara J. Politics Dev. 3, 93–101.

Makonye, F., Ehiane, S. O., and Otu, M. N. (2020). Dynamics of pre- and post-electoral violence in Zimbabwe since independence in April 1980 to November 2017. African Renaissance 17, 95–120. doi: 10.31920/2516-5305/2020/17n1a5

Mediayanose, O. E. (2018). The role of security in credible elections and sustainance of democracy in Nigeria. J. Pub. Admin. Finance Law 13, 134–141.

Nabiebu, M. (2022). Nigeria's legal regulatory framework for ensuring a credible 2023 election. Int. J. Law Soc. 1, 221–231. doi: 10.59683/ijls.v1i3.32

National Democratic Institute (2008). Final NDI report on Nigeria’s 2007 elections. Washington, DC: National Democratic Institute.

Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room (2015). Report on Nigeria’s 2015 general elections. Abuja: Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room.

Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room (2019). Report of Nigeria’s 2019 general elections. Abuja: Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room.

Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room (2023). Report on Nigeria’s 2023 general elections. Abuja: Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room.

Nnabuife, C. (2024) APC has worsened situations of Nigerians, weaponized poverty- CUPP. Available online at https://tribuneonlineng.com/apc-has-worsened-situation-of-nigerians-weaponized-poverty-cupp/ (accessed November 12, 2024).

Nwagwu, E. J., Uwaechia, O. G., Udegbunam, K. C., and Nnamani, R. (2022). Vote buying during 2015 and 2019 general elections: manifestation and implications on democratic development in Nigeria. Cogent Soc. Sci. 8, 1–28. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2021.1995237

Obiam, S. C. (2021). The Nigerian state and electoral violence: an analysis of the 2019 presidential general election in Nigeria. IOSR J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 26, 53–61. doi: 10.9790/0837-2603045361

Ogele, E. P. (2020). Battle on the ballot: trends of electoral violence and human security in Nigeria, 1964-2019. J. Soc. Polit. Sci. 3, 883–900. doi: 10.31014/aior.1991.03.03.221

Oni, E. O. (2020). The politicization of election litigation in Nigeria’s fourth republic. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Oni, E. O. (2024). Party discipline and the crisis of election Administration in Contemporary Nigeria. Afr. Renaissance 21:2532.

Oni, E. O., Erameh, N. I., and Oladejo, A. O. (2017). Nigeria’s fourth republic, electoral administration and the challenge of democratic consolidation. Afr. J. Gov. Dev. 6, 38–72.

Opara, T. (2020). FRSC deploys 1,500 personnel, 35 vehicles for Edo elections. Available online at: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2020/09/frsc-deploys-1500-personnel-35-vehicles-for-edo-elections/ (accessed September 18, 2024).

Orebe, F. (2024). The call for military takeover- an indictment of the Nigerian political class. Available online at: https://thenationonlineng.net/the-call-for-military-takeover-an-indictment-of-the-nigerian-political-class/ (accessed November 12, 2024).

Rosenau, W., Mushen, E., and McQuaid, J. (2015). Security during Nigeria’s 2015 National Elections: What should we expect from the police? Washington, DC: CNA Analysis and Solutions.

Tarouco, G. (2023). Brazilian 2022 general elections: process, results, and implications. Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política 32, 153–168. doi: 10.26851/RUCP.32.1.7

The Carter Center and National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (1999). Observing the 1998–99 Nigeria elections: Final report. Summer 1999. Atlanta: The Carter Center.

Tirivangasi, H. M., Nyahunda, L., and Maramura, T. C. (2021). Revisiting electoral violence in Zimbabwe: problems and prospects. Int. J. Criminol. Sociol. 10, 1066–1074. doi: 10.6000/1929-4409.2021.10.125

Tobi, A. A., and Oikhala, G. I. (2018). The police and election administration in Nigeria. Int. J. Pub. Admin. Financ. Law Issue. 14, 85–94.

Vick, R. (2024). Iran, trump and the third assassination plot. Available online at: https://time.com/7013497/donald-trump-iran-assassination-plot/on (accessed January 14, 2025).

YIAGA Africa (2023). Dashed hopes? YIAGA Africa report on Nigeria’s 2023 general election. Abuja: YIAGA.

Yoroms, G. (2017). Electoral violence, arms proliferations and electoral security in Nigeria: lessons from the twenty-fifteen elections for emerging democracies. Available online at: https://www.inecnigeria.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Conference-Paper-by-Gani-Yoroms1.pdf (accessed November 8, 2023).

Keywords: Nigeria, security, state fragility, insecurity, election administration, security agencies and democratic consolidation

Citation: Oni EO, Faluyi OT, Asumu LO and Olutola AA (2025) Security challenges and election administration in Nigeria’s fourth republic. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1458303. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1458303

Edited by:

Uchendu Eugene Chigbu, Namibia University of Science and Technology, NamibiaReviewed by:

Dorcas Ettang, Durban University of Technology, South AfricaDaniel Chigudu, University of South Africa, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Oni, Faluyi, Asumu and Olutola. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ebenezer Oluwole Oni, ZWJpbm90b3BzeTlAZ21haWwuY29t

Ebenezer Oluwole Oni

Ebenezer Oluwole Oni Olumuyiwa Temitope Faluyi2

Olumuyiwa Temitope Faluyi2