- School of Built Environment and Development Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

South Africa is globally rated as the most unequal society, which does not conform to democratic principles. Inequality is perpetuated by uneven security provisions at the behest of the state, which entrenches elitism. The study investigates the extraordinary utilisation of Very Important People’s blue light security by politicians and the budgetary implications and multiplier effects, such as exacerbating inequalities in South Africa. In pursuit of the study’s noble course, Social Contract Theory is employed to explain how the government has broken the social contract with the electorate in pursuit of the protection of elite status while deserting service delivery. This paper utilises doctrinal legal research to interpret legislation governing the use of VIP blue lights and a comprehensive literature review as a complementary method due to the limited literature. The government is prioritising the security of politicians, while law enforcement continues to receive a decreasing budget amid persistent crime challenges. The conduct of VIP blue light security is found to be inconsistent with road regulations and exposes other road users to danger. The study recommended that the government reconsider the allocation of resources, centralise the procurement of VIP blue lights, and employ innovative strategies in areas with poor police visibility.

1 Introduction

South Africa is one of the youngest democracies in the world, at only 30 years of age and is still confronted by the highest levels of inequalities, thus ranking 5th in the world (World Bank, 2022). Despite the prevailing social disparities, the country’s political leadership in all three spheres of government seems to be concerned with personal security details. The securing of politicians is disproportionate to the number of political killings, which merely account for 488 since 2000–2023. These statistics are insignificant compared to the daily crime (Matamba and Thobela, 2024). This illustrates an image that politicians are self-serving than concentrating on addressing the extremely high inequalities which give birth to the recurring social ills. This study argues that the South African government, which is amongst a few countries with the largest cabinet comprising 32 ministers and 43 deputy ministers, in line with the ministerial handbook, is afforded support staff members and VIP blue light vehicles paid by the state. Through the ministerial handbook, political elitism is ushered in because a person is afforded VIP drivers and protectors upon assuming an executive position. In addition, the South African Police Service also conducts static security needs analysis and provides protection for the three maximum households of ministers (Ministerial Handbook, 2022).

A Large cabinet is associated with poor government performance and increased political leadership budget expenditure (Wehner and Mills, 2022). The installation of a large cabinet is occurring against the backdrop of all government departments receiving budget cuts due to austerity measures to mitigate the servicing of debts and low economic growth (Sibeko and Isaacs, 2019). This study strongly argues that the security upkeep of politicians is stealing from the poor because critical service departments aimed at enhancing people’s lives are defunded, while an exorbitant amount of money is spent on politicians’ security (Parliament Monitoring Group, 2023d). The reduction in public expenditure has resulted in high crime levels as people find alternative means to earn a living, such as using VIP blue lights, which are easily accessible to commit crime, and other means. Evidently, the South Police Service, due to budgetary constraints emanating from austerity measures, is unable to fill existing vacancies, yet VIP Security Services Unit received an increased budget of R2 billion (National Treasury, 2024). The continued budgetary increment of VIP protection against social services by the government perpetuates the high inequalities, unemployment, crime, and basic infrastructural challenges. It is deplorable because millions of people are languishing in squalor (Ngubane et al., 2023). Moreover, the so-called VIP blue light vehicles are utilised to intimidate other road users and expose them to danger as they constantly disobey road regulations (Automobile Association, 2023).

The act by the government to prioritise VIP security is against the principles of Ubuntu of embracing human dignity, equality, and advancement of human rights, fairness, and justice as the foundation of the country’s constitution. Political elitism has assumed a central role, eroding democracy’s founding principles and Ubuntu, which is interwoven in the country’s history of oppression. However, the VIP blue light protectors have sometimes been used to instigate fear and abuse ordinary citizens. For example, members of the Presidential VIP unit assigned to the Deputy President of South Africa allegedly assaulted three motorists claiming an untoward road behaviour (Heywood, 2023). The incident and many others demonstrated the abuse of power by members of the South African Police Service (SAPS) who, by law, are assigned the responsibility to protect citizens and uphold constitutional rights at all times. Moreover, they are publicly viewed as an attempt to assert elitism advanced by political principals. The continuously witnessed elitism and abuse of power are akin to spitting on taxpayers’ faces as they are the ones responsible for funding the government activities through taxes, yet find themselves at the receiving end of political abuse and elitism through VIP blue lights. The government ought to be intensifying social upliftment programmes to bridge inequalities and reduce crime. Evidently, the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) had its budget slashed from R700,000, while the VIP security received an increment of R52 million (Parliament Monitoring Group, 2024; Hlazo-Webster, 2024). This demonstrates the significance of politicians’ security over addressing social challenges.

In addition, South Africa’s social challenges continue to worsen while politicians focus more on security. Statistically, there is glaring evidence that suggests the social challenges are getting worse. For instance, unemployment rate in the 1st quarter of 2024 stood at 32,9%, with the crime index clocking at 75.4% making it number one in Africa and 5th globally, inequality is ranked the most unequal country in the world (World Bank, 2022; Statistics South Africa, 2024; Statista, 2024). Black Africans remain the hardest hit population by unemployment, sitting at 36. 8%, which is a slight decrease from the 41% recorded in 2004, compared to the 6% of white people and black people who are commonly featured in criminal activities (Statistics South Africa, 2023). Crime is not uniformly experienced because areas with high rates of poverty and unemployment often experience poor allocation of policing resources and have high population density as opposed to where the executive with high-security personnel resides (Ndlela, 2020; Siegelaar and Ballard, 2023). These conditions illustrate the deplorable conditions that the general populace is confronted with, while the executive is masquerading in VIP blue light vehicles. Hence, it is for this rationale that this study investigates the excessive use of VIP blue lights amid the high levels of inequalities, which have dire multiplier effects such as unemployment, poverty and crime.

2 Theoretical framework

This study uses the Social Contract Theory (SCT) to explain how Very Important People (VIP) blue lights are utilised. In the explanation of the excessive utilisation of VIP protection blue lights and the exacerbation of inequalities, this article entails the work of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau as three avid philosophers on ethics, accountability, obedience, and transformation. The uneven security provisions between citizens and politicians are reflective of societal power imbalances and contribute to the widening of inequalities. The allocation of security is not informed by cost–benefit because the investment is too high for a selected few while the greater populace languishes in crime-infested communities (Thorne, 2024). SCT is deemed relevant for this study because it addresses the relationship between the government authority and people’s consent to be governed based on the agreed terms and conditions. Fear, intimidation and elitism the outcomes of the VIP blue light vehicles are cynical synonyms of the broken social contract between the electorate and the elected (Van der Bijl, 2013). In agreement, VIP blue light vehicles force other road users off the road for easy passage even at the height of traffic congestion and threaten them with guns for refusing them a way (Automobile Association, 2023). This is per the government prescripts on awarding VIP protection to political office bearers, administrative officials and foreign dignitaries such is contained in section 205 (3) and the Risk Management Support Systems Policy as amended in 2004. The Constitution affirms that the government must be accountable and abide by the laws of the republic (Republic of South Africa, 1996a,b). The witnessed abuse by the VIP blue lights-driven individuals is contrary to lawfulness and discards the upholding of constitutional values.

Social Contract Theory postulates that the legitimacy of government is incumbent upon people’s consent or agreement (Jos, 2006; Moore, 2010). In the context of South Africa, the government ignores its laws as it continues to fail to implement its National Road Traffic Regulations of 2000 regarding the use of VIP blue lights. The City of Johannesburg unilaterally afforded VIP protection to mayoral committee members and members of the executive without following proper procedures, such as a security assessment from the South African Police Service (Maromo, 2024). In addition, the skyrocketing crime is a breach of the constitutional agreement between the state and the people, as they no longer live in a safe environment (Constitution, 1996). Yet, government representatives are guaranteed safety at the behest of the vulnerable citizens they lead. In addition to high crime, VIP blue light personnel lack accountability for disregarding road regulations. For instance, a Former KwaZulu-Natal Transport and Safety Member of the Executive (MEC) wanted to open a court case against a public member who filmed an abuse of a road user by members of the VIP Protection Service (Arrive Alive, 2008). Furthermore, this indicates a self-serving government because millions of citizens are insecure while politicians presiding over the affairs of the government are secure, and from time to time, they increase their security (Parliament Monitoring Group, 2021).

3 Research methodology

This study utilises a non-empirical research design, the Comprehensive Literature Review (CLR) and Doctrinal Legal Research. The use of these non-empirical research methods was informed by the scholarly dearth of the phenomenon under study. The Comprehensive Literature Review is described as a synthesis of scientific evidence to answer a research question transparently through the use of multiple sources of data (Williams, 2018; Lame, 2019). It is complemented by the Doctrinal Legal Research methodology, which is significant due to aiding the study to be able to synthesise and analyse legislation governing the use of VIP protection blue lights.

3.1 Doctrinal legal research

The method herein deals with the prescripts of the National Road Traffic Act and the utilisation of VIP blue lights in the context of South Africa as a low–income country. This is crucial as it lays a foundation for the determination of the granting and use of VIP protection blue lights in all spheres of government, particularly the local sphere, where there is a prevalence of crime conducted using the VIP blue lights fitted vehicles.

3.1.1 National Road Traffic Act 93 of 1996 and National Road Traffic Regulations, 2000

According to the National Road Traffic Act 93 of 1996, it is a chargeable offence for any person to disobey road traffic signs or exceed the set speed limit (Republic of South Africa, 1996a,b). However, the National Road Traffic Regulations of 2000 stipulate that vehicles are to be fitted with a lamp displaying a blue light. These legal prescripts do not apply to emergency vehicles, which are regarded by the Defence Force, Municipal Traffic Officers and South African Police Service members driving an emergency vehicle. In addition, these vehicles must be fitted with a device emitting sound and a flashing blue light in the event of exceeding the speed limit (Republic of South Africa, 2000).

Furthermore, the NRTA grants exemption to firefighters’ vehicles, ambulances and traffic officers engaged in their duties or to persons in civil protection to disregard road rules. This should be done under certain circumstances, but the safety of all other road users must be considered (Republic of South Africa, 1996a,b). Moreover, VIP protection in South Africa is afforded to members of the Executive at national and provincial levels Ministers, Deputy Ministers, National Speaker, Chairperson of the National Council of Provinces, President of the Supreme Court of Appeal and their deputies, Judge Presidents, members of the Executive Councils and Speakers of the provincial legislature (Constitution, 1996; Ministerial Handbook, 2022). Many times members of the VIP protection services in the execution of their duties and non-emergency situations are found to be disregarding the safety of other road users by disobeying road speed limits and overtaking in dangerous zones, thus causing accidents (Arrive Alive, 2011; Van der Bijl, 2013; Automobile Association, 2023).

Furthermore, this study argues that VIP blue light vehicle personnel often contravene the NRTA 93 of 1996, accident rules and procedures. This study contends that the conduct of the VIP blue lights brigade is tantamount to abuse of power and disregard of the universal right to life, as such situations may result in deaths. The VIP blue light brigade challenge is also experienced in the local sphere of government, which is not included in the Ministerial handbook and Presidential Protection Service for the provision of VIP blue light security detail. However, the next section discusses the applicable laws for the provision of such service in the local sphere of government.

3.1.2 Powers of the local sphere of government

The Municipal Systems Act of 2000 allows municipalities to establish bylaws for the safety of their inhabitants and the enhancement of service delivery. This includes, amongst other establishment of municipal traffic services concerning the NRTA. Municipalities such as Ekurhuleni established their VIP protection unit to provide varying levels of protection to the Mayor, Speaker, Members of the Mayoral Committee and Chief Whip, Councillors, Other Council Employees and Visiting Dignitaries from 1 to 6, respectively (Ekurhuleni metropolitan municipality, 2005). Furthermore, the policy stipulates that members of the VIP Protection must be Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Police Department (EMPD) officers. The policy per the NRTA spells out that the service must be offered by traffic officers. This policy practice is enforced in municipalities with traffic officer departments to provide VIP protection and ensure compliance with all traffic management regulations within that municipality. In essence, this implies that a non-trained individual as a traffic officer may not be assigned the responsibility of driving a vehicle emitting a blue light. However, municipalities without traffic officers utilise private security service providers to render VIP protection with VIP blue lights fitted vehicles. Corroborating this is the impoundment of the King Cetshwayo district municipality’s mayoral fleet for illegal use of blue light (Khumalo, 2024).

3.2 Comprehensive literature review

The Comprehensive Literature Review comprises three phases of CRL that have been used in this study, which are the Exploration Phase, the Interpretative Phase, and the Communicative Phase. Notably, each phase has various steps (Onwuegbuzie and Frels, 2015). This section explicitly unpacks how CRL phases have been employed to investigate the phenomenon under study.

3.2.1 Exploration phase

The exploratory phase has five steps, which are clearly explained, and this section explains how the five steps are applied in the course of this research article on the use of VIP protection blue lights and their contribution to crime.

3.2.2 Exploring beliefs and topics

In this stage, the research topic was identified. Thereafter, search terms such as ‘Blue lights gangs’, ‘crime’, ‘security costs implications’, ‘inequality’, and ‘security needs’ were utilised to gather data on the utilisation of VIP blue lights and contributing to criminal activities in low-income countries. The proceeding stage dealt with initiating the search.

3.2.3 Initiating the search

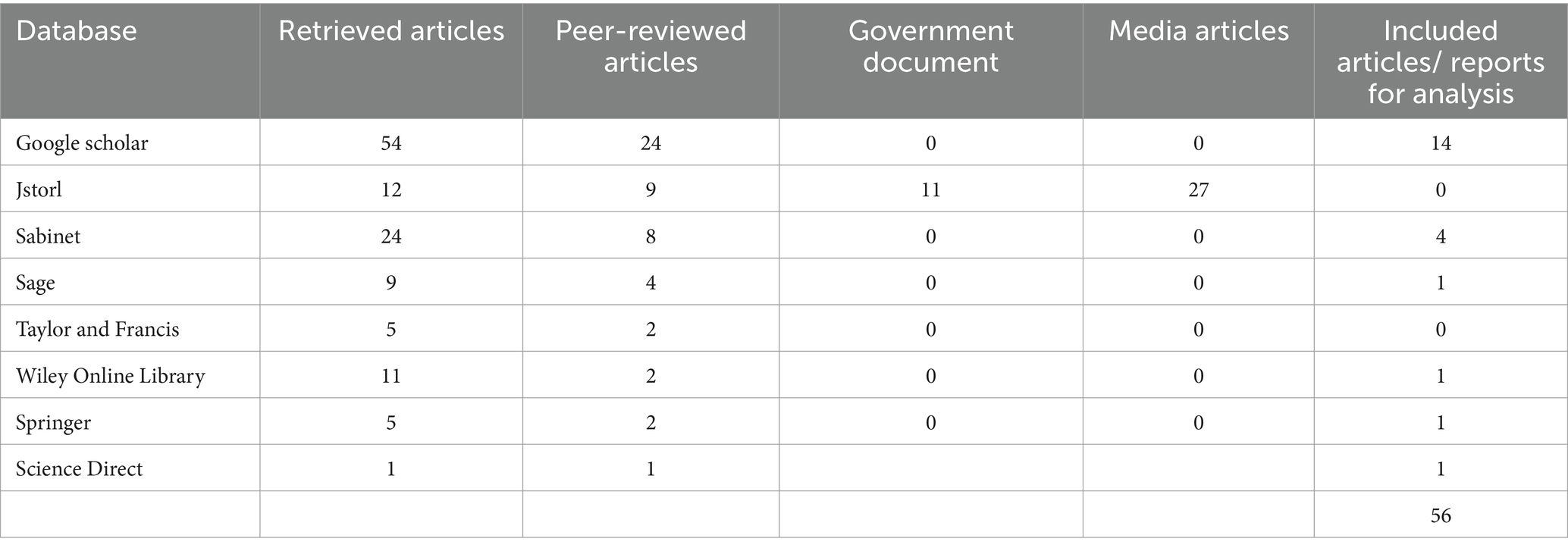

The stage addressed how and where data will be harvested. Following the research topic, the searched and harvested data were from South Africa and written in English. However, the available literature suggested that there is a challenge of empirical data in South Africa, hence non-empirical retrieved for analysis consideration in this study. The databases which were used were Google Scholar, Sabinet, Science Direct, government documents and media articles. This process yielded 121 search outcomes, which were analysed. As a result, after the removal of duplications and irrelevant articles, the study remained with 22 articles, 11 government documents and 27 media articles.

3.2.4 Storing and organising information

The retrieved peer-reviewed articles, government documents and media articles on the use of VIP protection blue lights were sorted and stored. Then, Microsoft Excel was used to extract information that was stored in accordance with three research methodologies. The authors gathered 14 qualitative, 6 quantitative and mixed methods research methods conducted articles. These studies were complemented by 11 government documents and 27 media articles. The dominance of qualitative research studies does not insinuate that the study is qualitative.

3.2.5 Selecting and deselecting information

This study utilised three criteria for inclusion for analysis: location, language and relevance to the research question. As a result, all peer-reviewed empirical and non-empirical studies that were from South Africa, written in English, and relevant to the research question were included for analysis. Due to the scholarly dearth of articles relating to the subject under review, government documents and media articles were incorporated for analysis to supplement inadequate scholarly work on the subject. Nevertheless, 38 articles were discarded from the study due to irrelevance and duplication. As a result, the study remained with 84 articles for analysis, of which only 56, inclusive of government documents and media reports, were analysed.

3.2.6 MODES data collection

MODES is the abbreviation of media, observation, experts and secondary data, it is generally informed by insufficient scientific knowledge in the subject under review (Onwuegbuzie and Frels, 2015). This is the case with the current study, and the authors resorted to incorporating extracted information from the government documents and media articles on the use of VIP protection blue lights and their contribution to crime. However, the limitations of the comprehensive literature review are the reliance on secondary data, and this fails to capture the voices of significant participants. Furthermore, the study faced the scarce availability of peer-reviewed literature regarding the excessive utilisation of VIP blue light security and inequalities. This was overcome through incorporating media articles and government documents to mitigate the dearth of literature, which is in line with the MODES data collection.

3.2.7 Interpretive phase

This phase accounts for the databases, the number of peer-reviewed articles and the government documents and media articles from which data was extracted for analysis. The analysis illustrates a government loophole in issuing VIP blue lights at the local government level, which ends up in the criminal’s hands. Nonetheless, Table 1 provides data from various data sources that were included and excluded in the analysis.

3.2.8 Communication phase

The communication phase is the final phase of the seven-step process and deals with the presentation of the research outcomes of the CLR (Onwuegbuzie and Frels, 2015). The findings of this research study were informed by 56 peer-reviewed articles, government documents, and media articles that were analysed as stipulated in the aforementioned section. The findings of this study capture the excessive utilisation of the VIP protection blue lights. The following discussions unpack the findings of the study.

4 Findings of the study

The study’s findings are obtained through the Doctrinal Legal Research and Comprehensive Literature Review. The presentation of findings is followed by a discussion of the findings.

4.1 Security services and resource allocation

The South African constitution legally lays the foundation for the establishment of the South African Police Service Division of Protection and Security Services (PSS) to provide professional, effective and accountable protection and security services to all individuals identified and government interests in South Africa as very important people. The mandate of PSS is to provide VIP protection services, both static and in transit and regulatory services to all identified strategic installations (Constitution, 1996; South African Cabinet, 2003). This implies that the provision of VIP protection blue lights to government-identified individuals at the national level remains the prerogative of the Ministry of Police Services. This study argues that this has led to the inability to quantify the number of individuals accorded the status, and all three spheres of government are engaged in the process.

This has compromised both the lives of VIPs and non-VIP citizens. Apart from this, it has also created a special type of people classification. For instance, in a country of 60.6 million people, in 2017, 289 individuals were afforded VIP protection (Pariament Monitoring Group, 2017; Census South Africa, 2022). What makes matters worse is the increasing social displeasure against the VIP protection blue light members abusing their powers and endangering the lives of other road users, as in the case of the Deputy President’s Presidential Protection Unit assaulting motorists (Heywood, 2023). The government is seen as disregarding the growing discontent between itself and the citizens. Evidently, the VIP Protection Service and Programmes consume 2% of the annual budget of the Department of Police and receive almost the same amount of budget as the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation (DPCI), commonly known as Hawks received R4. 74 billion, while VIP Protection Service received R2. 09 billion (National Treasury, 2024). This study argues that the steep increase from R3.76 billion has been necessitated by the increased government size due to the Government of National Unity (GNU) (Pariament Monitoring Group, 2023a; Hlazo-Webster, 2024). This implies the security needs of politicians take centre stage over citizens and disregard the government’s position on austerity measures. This situation arises when law enforcement is overwhelmed by a lack of resources to effectively prevent and combat crime in the country. It is stated that crime is interwoven in the untransformed socio-economic status of millions of people (Kruger and Landman, 2008; Siegelaar and Ballard, 2023). The continued increase of allocation of resources towards securing politicians security of citizens is demonstrative of the government’s lack of desire to crap the whip on organised crimes which are inherent to the high inequalities engulfing the country.

4.2 The effect of VIP protection, blue light and politicians

The literature suggests that the challenge of the abuse of VIP protection blue light crime is ongoing. VIP blue light crime is understood as crime conducted using blue light-fitted vehicles, which is only common in South Africa. This study argues that there is a causal relationship between inequality and crime. The assertion is confirmed by numerous scholars (Kruger and Landman, 2008; Harris and Vermaak, 2015; Jeke et al., 2021). The high inequalities in the country have led to high crime rates (Siegelaar and Ballard, 2023). The study postulates that criminals have taken advantage of the uneven treatment of citizens and poor policing, thus engaging in VIP blue light crime. In the case of VIP blue lights, this study strongly argues that South Africa is unable to administer the purchasing and distribution of identification lamps effectively. Identification lights often end up in the hands of bogus cops who utilise them in the conduct of crime to endanger unsuspecting road users.

VIP blue lights and sirens were found to be sold in Durban China Mall to members of the public (Wicks, 2010). The widespread easy accessibility of identification lamps has caused security mayhem for the public. This has prompted an increase in road traffic crime syndicate incidents in the Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga Provinces. The R28 highway near Krugersdorp, N14 outside Tshwane, N12 on the East and West R in Gauteng; the N4 and R511 near Brits in the North West Province and the N3 highway in the vicinity of Villiers to Heidelberg were flagged as hotspots for the blue lights crimes and hijacking with most occurring at night due to poor police visibility (Crime Watch, 2022; Government News, 2024). It is argued that major enablers of the VIP blue light crime are poor lighting, lack of surveillance technologies, police members, police visibility, unbranded police and cloning of police vehicles (Wright and Ribbens, 2016; Government News, 2024). This is corroborated by the fact that in the City of Johannesburg alone, cloned police vehicles have been responsible for 35 cases of hijacking, with most of these hijackings taking place in the above-mentioned routes (Crime Watch, 2022). This has resulted in a depreciation of trust afforded to the police by the citizens due to involvement in unethical behaviour (Krönke et al., 2024). Victims of this nature of crime are dependent on the South African Police Service and municipalities for security, which are not efficient in discharging their constitutional duty for numerous reasons, which have been shared above. Politicians remain unscattered by this crime because taxpayers assure them of security. These occurrences resonate with Ndlela’s (2020) argument that crime affects citizens differently, with the poor and vulnerable being the most victims.

The study argues that politicians are partly to blame for contravening the NRTA and NRM for illegal usage of VIP blue lights, but they are barely accountable for their actions. Evidently, the Inkatha Freedom Party chairperson and also a former mayor of King Cetshwayo, one of the District municipality councillors’ convoy emitting blue, was impounded for illegal use of VIP protection blue light, and soon after this quagmire, he was granted another fleet (Khumalo, 2024). This was done despite the King Cetshwayo District municipality not having a municipal traffic unit, implying that they do fall within the description provided by Republic of South Africa (1996a,b) and Republic of South Africa (2000). The act of using public funds in this unlawful exercise indicates how there is a lack of accountability and respect for the law, posing a question of how private security companies acquire VIP protection blue lights. This quagmire is old, and there have been endeavours by the provincial government of KwaZulu-Natal and the Western Cape to curtail the scourge of the use of VIP blue lights by non-designated persons through issuing memoranda. However, the challenge is still pertinent in these provinces, particularly KwaZulu-Natal, as flagged as one of the three provinces regarded as hotspots (Government News, 2012; Carlisle, 2013; Khumalo, 2024).

4.3 VIP protection blue lights, and crime

The availability of VIP protection blue lights is widely available to ordinary members of society, whether through security cluster officers or private security. In concurrence, police officers are in cahoots with blue light gangs either through the provision of uniforms, blue lights or firearms (Phiyega, 2010; Nortje, 2023). The easy accessibility of VIP blue lights at the courtesy of police officials has ripple effects on various societal aspects. This exposes the country to security threats, and more vulnerable are the unsuspecting citizens. This calls for strict regulation of the procurement of VIP blue lights, which are presently easily available even in shopping centres. For example, they diminish public confidence in the work of law officers, including traffic officers, expose people to criminal activities and limit international visitors and tourism-facilitated livelihoods due to reduced tourist activities (Bezuidenhout, 2014; Mbane and Ezeuduji, 2022; Krönke et al., 2024).

On the other hand, the road transport freight business is shedding millions every month due to VIP blue light gangs, fake police officers and hijackings in the routes mentioned in section 4.2. This is occurring at a time when the country’s seaports are poorly performing and shipping companies are opting for alternative routes (Chinedum, 2018; Grater and Chasomeris, 2022). Thus, making road transport freight a highly sought after to deliver goods all over the continent, with 70% of goods delivered through road (Yesufu, 2021; Mlepo, 2022). To arrest the negative impact of VIP blue light crime and other road crimes government need to employ innovative strategies to enhance road safety, which will also boost citizens’ and international visitors’ confidence in safety.

The South African law enforcement agencies are partly to be blamed for the scourge which undermines the Republic and sabotages the economy. However, arresting the scourge is attainable through the enforcement of laws which stipulate that it is a criminal offence to purport to be a police, military or traffic official and to utilise a vehicle fitted with a lamp emitting blue light on public roads (Republic of South Africa, 1995). The enforcement of this act will curtail the abuse of the use of VIP protection blue lights by politicians and members of society. Subsequently, reduce the incidents of car hijacking by those purporting to be police officials.

4.4 Public resentment and legal challenges against VIP blue lights

The widespread utilisation of VIP blue lights, largely by politicians and armed security detail, has seen public growing discontent with their leaders. People and Section 27 institutions view the blue light-fitted vehicles as permission to break all road regulations (South African Human Rights Commission, 2012). People argue that such vehicles barely stop at traffic lights, which in turn exposes other road users to risk. For instance, in 2011, a vehicle assigned to the Local Government and Housing member of the executive (MEC) in the Gauteng province VIP blue light vehicle severely injured a grade 12 learner who eventually succumbed to injuries because of skipping a traffic light (Arrive Alive, 2011). Moreover, society argues that the politicians, through reinforced security details, are contravening road regulations and abusing other road users. This has prompted the public to propose a ban on VIP blue light usage until the policy clearly articulates the question of emergency, as the current legislation permits their use under such a context (Sibanda, 2023). The study argues that this is perceived as elitism, and the preservation status of politicians comes at an exorbitant cost to taxpayers.

Contrarily, the issue of the abuse of power through VIP blue lights has seen the discontent ventilated in the courts of law. The people’s discontent has caught the eye of political leaders such as the African National Congress Secretary General, who warned that the behaviour of VIP protection, if not addressed, would lead to turmoil (Madisa, 2023). This case is demonstrative of how voters are increasingly resentful about the abuse of the VIP blue lights, primarily by politicians who by virtue of being people’s representatives, ought to be protecting them, but this is not the case. This study perceives that people elect their leaders only to be shielded against them in their execution of fiduciary duties.

4.5 Road-related crime statistics

Table 2 provides road-related crime statistics to draw a vivid image of the progress or regression by police service to fight the scourge. The table further exposes the government’s failure to record VIP blue light crimes.

Table 2 presents statistics that illustrate a bleak image of how road-related crimes are on the rise in the country, but notably, truck hijacking has slightly decreased. Carjacking illustrates a huge growth of 6.5%, which is a major setback to public safety. However, this study argues that the statistics are inconclusive to fully understand the level of committed crime by VIP protection blue light gangs. For instance, the police released statistics for the 2018/19 financial year confirm that blue light gangs and fake police crimes were on the rise by 50, 32.1 and 14.8% in Northern Cape, Mpumalanga and North West provinces, respectively (South Africa Police Service, 2019). The situation is escalating to a catastrophe, and the government is failing to account in the form of statistics.

The rise in these crimes is intrinsic to the shortage of members of the South African Police Service due to many factors, with most police officers leaving the sector motivated by high rewards in other sectors (Mukwevho and Bussin, 2021). Further to this is the unethical police behaviour, which has resulted in a dismal of 46 police officers, a decrease from 2010, when 119 police officers were dismissed for various crimes, including giving SAPS uniforms to members of the public (Government Communications, 2010; South African Police Service, 2023b). The escalating crime has resulted in politicians prioritising their security, which comes at a high cost in the three spheres of government. Evidently, eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality agreed to purchase a new fleet for the Security and Protection Services at R25 million (eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality, 2024). This exorbitant expenditure is occurring amid some of eThekwini dwellers are battling with a poor provision of clean water and high levels of crime, which demonstrates that politicians lead at the behest of people to serve themselves more than those who elected them. Furthermore, these developments postulate that the security problems engulfing the country are not merely about poor capacity but a lack of political will by leaders to prioritise the fight against crime.

4.6 Police visibility in crime hotspots

Police visibility is a strategy employed globally to prevent crime, and it is also the case in South Africa. However, the soaring crime and abhorrent VIP blue light gangs’ road infestation raise questions about the effectiveness of police visibility. There is a general failure by the government to adhere to the National Crime Prevention Strategy and White Paper on Safety and Security, which postulates that local government should play a central role in crime prevention (Mothibi and Roelofse, 2017). Victims and community members of routes infested with blue light gangs and police decry poor police visibility and poor lighting in hotspots (Nkosi, 2023). Whereas, SAPS and municipalities blame the poor police visibility on inadequate resources, which stretch the limited available resources (Rauch et al., 2001; Lamb, 2021). Though the study agrees that there is a human capital shortage of 8,000 detectives in SAPS (Parliament Monitoring Group, 2023b). But another significant challenge is the improper prioritisation of resources, as a chunk of resources is channelled to cater for VIP security units in all spheres of government, while leaving citizens vulnerable to crime. This indicates that South Africa has two protection services, namely one designated for politicians and an underfunded police service for the general populace.

This is informed by the state of disarray of the police call centre, which is proving to be detrimental in the fight against crime and is not competitive due 60% shortage of workers. However, the government resolved to appoint interns to cover the approximately 7 million dropped calls and to work with the private sector to enhance its capability towards crime fighting (Government News, 2023; Parliament Monitoring Group, 2023c). Amid these challenges, the government of Gauteng province began a public-private partnership with the launch of 6,000 Vuma cameras to surveil streets (Government News, 2024), but the impact of Vuma cameras in the fight against crime has not yet been measured.

5 Discussion

The South African government has failed to address social inequalities, which have resulted in a scourge of crime, including VIP blue light crime. Further, learned that the extended size of government office bearers and allocation of security to politicians have ripple effects on the Department of Police budget and disregarding the cost containment measures adopted by the government. This is because the VIP protection service consumes 2% of the total Department of Police budget, which is failing to provide adequate police vehicles and stations to communities (Govender, 2019; National Treasury, 2024). The prioritisation of VIP security while taking away from the already vulnerable is a breach of the social contract, as their security is further weakened by inadequate resource distribution. This is affirmed by the interrogated literature that poor policing, light visibility and inadequate surveillance are the country’s primary challenges in fighting the scourge of blue light crime syndicates operating actively in the three provinces.

The latter assertion is similarly echoed by Somduth (2023), who pointed out that for 6 years, road speed cameras have not been operational in eThekwini municipality because of the dispute between the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) and the eThekwini Metropolitan service provider. This has resulted in a state of lawlessness and a loss of possible revenue amounting to R800 million. This demonstrates that bureaucratic processes may result in policing inefficiencies, which not only exacerbate crime but also cause significant economic losses. Furthermore, the lawlessness is an illustration of the government’s desertion of its constitutional duty of ensuring that all citizens reside in a safe environment. The study also found that law enforcement in the curtailment of VIP blue light crime has proven to be a challenge, despite the existence of relevant prescripts. For example, the South African Police Service and the Private Security Industry Regulatory Authority Advocate (PSIRA) were compelled to issue a joint statement to warn against private security companies utilising blue light identification lamps because it is illegal to utilise them (PSIRA, 2019). This was informed by the fact that private security companies in their provision of VIP security utilise VIP blue lights, as was the case with King Cetshwayo’s former mayor. It was deduced that the usage of VIP blue lights by private security companies was due to easy procurement and distribution in shopping malls and by police officers. For instance, the South African Police Service Deputy Commissioner was fingered in the fraudulent awarding of a tender to procure VIP blue lights and other warning equipment (Cruywagen, 2023).

The prevailing high inequalities, crime, poverty and abuse of power by individuals driven in VIP blue light-fitted vehicles have resulted in public discontent with authorities. They disregard most of the road rules and place the lives of other road users in danger. Moreover, the abuse tramples on the very principles of social contract theory, which citizens enter into for a just society governed by laws protecting the rights of all and VIP protection service personnel are law unto themselves. The public demonstrated their social discontent through a petition to call for the end of VIP blue lights (Zille, 2011). However, it is worth stating that since the partition in 2011, the incidents of road crime involving VIP blue light have increased tremendously, but the South African Police Service fails to capture the statistics of this nature of crime and develop mechanisms to curtail it.

This study postulates that to address the challenge of crime, the country would first need to address the inequality question. This is because there is a common shared view by governments and scholars that inequality has multiplying effects such as crime, poverty and unemployment. These issues fuel certain quarters of society to engage in illegal activities to earn a living. Echoing akin sentiments, Büttner (2022) points out that South African crime is influenced by apartheid, which is an inter-racial crime that primarily involves property and entails violent crime within a singular race and the challenge of high inequalities and crime also experienced in Latin American countries. The assertion also resonates with the view that crime in South Africa is not evenly experienced, with the poor suffering the most, while politicians shield themselves through reinforced security.

6 Conclusion

This research paper reaffirms the findings of studies conducted on crime that it is rooted in inequalities, so is unemployment and poverty too, but notes that it has racial implications. This implies that the previously disadvantaged individuals are actively participating and are also victims of crime due to high inequalities. Therefore, addressing inequalities in the country would also yield positive outcomes in the fight against crime. On the other side, the study discovered that politicians continue to prioritise VIP protection blue lights through increased spending, while the entire Department of Police is seized with human resources and tools to fight crime, this is tantamount to stealing from the poor. The increased VIP protection service is also not consistent with the government-enforced austerity measures, which severely affect social service departments such as Education, Police, Social Development and others. The study postulates that the conduct of the VIP blue lights security often contravenes the National Road Traffic Act and Traffic Road Regulations, which also includes municipalities without traffic divisions and human rights violations by members falling within the South African Police Service VIP protection unit.

The persistent inequalities and shortage of resources have exacerbated the activities of VIP blue light gangs. This was found to be in line with the police’s admission and victims of such crime that poor police visibility, unbranded police vehicles and poor lighting in hotspots are exacerbating VIP blue light crime. However, of greater concern to the public was the undue conduct by VIP blue light vehicles, which they argued places other road users in danger and is a pure abuse of power as they repeatedly disregard all road regulations. This results in social discontent among members of the public. However, the government-implemented interventions have failed because of undue conduct, and crime has increased over the years.

The study was perplexed by the easy accessibility of the VIP blue lights to the general public, and this is cancerous to the fight against the VIP blue light gangs. Therefore, this study recommends that the government ought to heighten its efforts to reduce inequalities, which breed crime, poverty and other social problems. Moreover, reconsider reducing the allocation of resources to the VIP Protection Service Unit and redirect more resources to crime prevention and fighting efforts to fulfil the police’s constitutional mandate of protecting citizens. It is this study’s shared view that the government centralise the procurement of lamps emitting blue lights to Denel, a State arms manufacturing company. Further, consider deploying innovative technology in crime hotspots such as solar-powered CCTV and drones because these strategies have limited financial implications. Furthermore, the study recommends that in municipalities without traffic division, VIP protection services may be rendered by the South African Police Service VIP protection unit or second traffic police officers from a municipality falling within the jurisdiction of the same district. Therefore, there is a need for empirical studies to be conducted in the near future to address the current study’s shortcomings.

Author contributions

MNM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MMM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Arrive Alive. (2008). VIP driver punched in blue light crash. Available online at: https://www.arrivealive.co.za/news.aspx?s=4andi=4488andname=vip-driver-punched-in-blue-light-crash (Accessed July 26, 2024).

Arrive Alive (2011). Teen in coma after state car ‘skips robot’. Available online at: https://www.arrivealive.mobi/news.aspx?s=4andi=6205andname=teen-in-coma-after-state-car-skips-robot (Accessed June 22, 2024).

Automobile Association. (2023). Blue light violence again highlights need for urgent intervention in VIP unit’s operations. Available online at: https://aa.co.za/blue-light-violence-again-highlights-need-for-urgent-intervention-in-vip-units-operations/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CIn%20early%202022%20we%20noted,many%20times%20through%20heavy%20traffic (Accessed August 3, 2024).

Bezuidenhout, C. (2014). Intriguing paradox: the inability to keep South Africa safe and the successful hosting of mega global sporting events. Chapter Routledge. Available online at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/b17692-20/intriguing-paradox-inability-keep-south-africa-safe-successful-hosting-mega-global-sporting-events-christiaan-bezuidenhout (Accessed May, 11 2024).

Büttner, N. (2022). Local inequality and crime: new evidence from South Africa. J. Econ. Inequal 2025:4213303. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4213303

Carlisle, R. (2013). Blue lights abuse must come to an end. Available online at: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/news/blue-lights-abuse-must-come-end#:~:text=As%20per%20the%20draft%20regulations,emergency%2C%E (Accessed May 10, 2024).

Census South Africa. (2022). 60.6 million people in South Africa. Accessed 14 May 2024; Available online at: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=15601 (Accessed May 14, 2024).

Chinedum, O. (2018). Port congestion determinants and impacts on logistics and supply chain network of five African ports. J. Sustain. Dev. Trans. Log. 3, 70–82.

Crime Watch. (2022). Blue light gangs. Available online at: https://www.enca.com/shows/crime-watch-blue-light-gangs-13-november-2022 (Accessed May 14, 2024).

Cruywagen, V. (2023). Ex-deputy police boss blue light corruption charges ‘clear’ – court rejects defence bid to access documents. Available online at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2023-10-29-ex-deputy-police-boss-blue-light-corruption-charges-clear-court-rejects-defence-bid-to-access-documents/ (Accessed June 24, 2024).

Ekurhuleni metropolitan municipality. (2005). Policy: establishment of a VIP-protection unit. Available online at: https://www.ekurhuleni.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/0303C_EstablishmentVIPProtectionUnit.pdf (Accessed May 7, 2024).

eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality. (2024). Decision circular executive committee meeting 23 April 2024. Available online at: https://www.durban.gov.za/storage/Documents/Council%20Minutes%20And%20Decisions/Year%202024/DECISIONS%20COUNCIL%202024/DECISIONS%20-%20EXECUTIVE%20COMMITTEE%202024-04-23.pdf (Accessed May 13, 2024).

Government Communications. (2010). South African Police Service dismissed 119 for fraud and corruption in 2009/10 Fiscal– Minister Mthethwa. Available online at: https://www.gov.za/news/media-statements/south-african-police-service-dismissed-119-fraud-and-corruption-200910-fiscal (Accessed May 22, 2025).

Govender, D. (2019). Police and society: emerging dimensions in South Africa. Int. J. Crim. Justice Sci. 14, 376–391.

Government News. (2012). Executive statement on the use of blue lights, failure to obey road traffic signs, exceeding the speed limit and the size of security convoys for the executive council of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) presented to the KZN legislature by Mr willies Mchunu. Available online at: https://www.gov.za/news/media-statements/executive-statement-use-blue-lights-failure-obey-road-traffic-signs-exceeding (Accessed May 2, 2024).

Government News. (2023). Government, private sector to partner in improving police call Centre operations. Available online at: https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/government-private-sector-partner-improving-police-call-centre-operations (Accessed May 13, 2024).

Government News. (2024). Gauteng receives CCTV cameras to fight crime. Available online at: https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/gauteng-receives-cctv-cameras-fight-crime (Accessed May 13, 2024).

Grater, S., and Chasomeris, M. G. (2022). Analysing the impact of COVID-19 trade disruptions on port authority pricing and container shipping in South Africa. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 16:772.

Harris, G., and Vermaak, C. (2015). Economic inequality as a source of interpersonal violence: evidence from sub-Saharan Africa & South Africa. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 18, 45–57. doi: 10.17159/2222-3436/2015/v18n1a4

Heywood, M. (2023). Paul Mashatile VIP assault highlights police protection an expensive excuse for thuggery and vanity. Available online at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2023-07-04-paul-mashatile-vip-protection-assault/ (Accessed May 15, 2024).

Hlazo-Webster, N. (2024). Redirect VIP protection budget to fighting crime – BOSA. Available online at: https://www.politicsweb.co.za/politics/redirect-vip-protection-budget-to-fighting-crime (Accessed August 3, 2024).

Jeke, L., Chitenderu, T., and Moyo, C. (2021). Crime and economic development in South Africa: a panel data analysis. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Adm. IX, 424–438. doi: 10.35808/ijeba/712

Jos, P. H. (2006). Social contract theory: implications for professional ethics. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 36, 139–155. doi: 10.1177/0275074005282860

Khumalo, V. (2024). IFP KZN premier candidate’s blue-light vehicles impounded. Available online at: https://www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/932188-2/ (Accessed May 10, 2024).

Krönke, M., Mattes, R., and Lockwood, S. J. (2024). African political parties. In Oxford Bibliographies: African Studies. Oxford University Press.

Kruger, T., and Landman, K. (2008). Crime and the physical environment in South Africa: contextualizing international crime prevention experiences. Built Environ. 34, 75–87. doi: 10.2148/benv.34.1.75

Lamb, G. (2021). Safeguarding the republic? The south African police service, legitimacy and the tribulations of policing a violent democracy. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 56, 92–108. doi: 10.1177/0021909620946853

Lame, G. (2019). ‘Systematic literature reviews: an introduction’, in Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED19), Delft, The Netherlands.

Madisa, K. (2023). If unchecked, brutal action of VIP protectors could lead to revolt against government — Mbalula. Available online at: https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/south-africa/2023-07-05-if-unchecked-brutal-action-of-vip-protectors-could-lead-to-revolt-against-government-mbalula/ (Accessed August 3, 2024).

Maromo, J. (2024). City of Joburg says its VIP protection policy is “irregular, excessive” but was introduced by Herman Mashaba & DA. Available online at: https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/gauteng/city-of-joburg-says-its-vip-protection-policy-is-irregular-excessive-but-was-introduced-by-herman-mashaba-and-da-c558c19f-bcb1-4b97-b339-35e2d67f7ee5 (Accessed June 21, 2024).

Mbane, T. L., and Ezeuduji, I. O. (2022). Stakeholder perceptions of crime and security in township tourism development. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leisure 11, 1128–1142. doi: 10.46222/ajhtl.19770720.280

Mlepo, A. T. (2022). Attacks on road-freight transporters: a threat to trade participation for landlocked countries in southern Africa. J. Transp. Secur. 15, 23–40. doi: 10.1007/s12198-021-00242-6

Mothibi, K. A., and Roelofse, C. (2017). Poor crime prevention policy implementation: links to ‘fear of crime’. Acta Criminol. 30, 47–64.

Mukwevho, N. R., and Bussin, M. H. (2021). Exploring the role of a total rewards strategy in retaining south African police officers in Limpopo province. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 19:8. doi: 10.4102/sajhrm.v19i0.1391

National Treasury. (2024). Police Vote, 28. Available online at: https://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2024/ene/Vote%2028%20Police.pdf (Accessed July 26, 2024).

Ngubane, M. Z., Mndebele, S., and Kaseeram, I. (2023). Economic growth, unemployment and poverty: linear and non-linear evidence from South Africa. Heliyon 9:e20267. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20267

Nkosi, N. (2023). Police blame poor lighting as crime spikes on major roads. Available online at: https://www.iol.co.za/the-star/news/police-blame-poor-lighting-as-crime-spikes-on-major-roads-a35a7f28-2c1c-4014-a590-9d0868586969 (Accessed May 13, 2024).

Nortje, W. (2023). Professionalising the fight against police corruption in South Africa: towards a proactive anti-corruption regime. J. Jurid. Sci. 48, 72–95.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., and Frels, R. K. (2015). Using Q methodology in the literature review process: a mixed research approach. J. Educ. Issues 1, 90–109. doi: 10.5296/jei.v1i2.8396

Pariament Monitoring Group. (2017). Question NW1041 to the minister of police. Available online at: https://pmg.org.za/committee-question/5595/ (Accessed May 8, 2024).

Pariament Monitoring Group. (2023a). Report of the portfolio committee on police on the 2023/24 budget vote 28 and annual performance plan (APP) of the Department of Police (south African police service) dated 17 may 2023. Available online at: https://static.pmg.org.za/230517pcpolicereportvote28.pdf (Accessed May 8, 2024)

Parliament Monitoring Group. (2021). Defund the VIPs not the police. Available online at: https://static.pmg.org.za/Andrew-Speech.pdf (Accessed August 3, 2024).

Parliament Monitoring Group. (2023b). Police minister, Bheki Cele parliament oral reply. Available online at: https://static.pmg.org.za/RNO607-2023-11-08.pdf (Accessed May 13, 2024).

Parliament Monitoring Group. (2023c). Question NO42 to the minister of police. Available online at: https://static.pmg.org.za/RNO42-2023-03-01.pdf (Accessed May 13, 2024).

Parliament Monitoring Group. (2023d). South African police service 2023/24 budget and annual performance plan. Available online at: https://static.pmg.org.za/230426SCoSJ_SAPS_23-24_Annual_Performance_Plan_-_26_April_2023_Version_23_April_2023_-1.pdf (Accessed August 2, 2024).

Parliament Monitoring Group. (2024). EPWP performance with ministry. Available online at: https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/39774/#:~:text=The%20vision%20is%20to%20see,to%20do%20more%20with%20less (Accessed April 29, 2025).

Phiyega, R. (2010). Task team to address blue light crimes. Available online at: https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/task-team-address-blue-light-crimes (Accessed May 11, 2024).

PSIRA. (2019). Joint directive between south African police service and private security industry regulatory authority advocate. Available online at: https://www.psira.co.za/dmdocuments/circular/2019-07-18%20-%20Joint%20directive%20between%20SAPS%20-%20PSIRA%20-%20Unlawful%20use%20of%20Blue%20lights,%20look%20a-like%20police%20vehicles%20-%20Brandings%20-%20Uniforms.pdf (Accessed June 24, 2024).

Rauch, J., Shaw, M., and Louw, A. (2001). Municipal policing in South Africa: Development and challenges. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies.

Republic of South Africa (1995). South African police service act 68 of 1995, section 68 (1) (2) (3). Pretoria: Government Printer.

Republic of South Africa (1996b). South African constitution, act 108. Pretoria: Government Printer.

Republic of South Africa (2000). Amendment of the National Road Traffic Regulations. Pretoria: Government Printer.

Sibanda, O. (2023). Ban blue light brigades until the law is reformed to respect human rights. Available online at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2023-07-04-ban-blue-light-brigades-until-the-law-is-reformed-to-respect-human-rights/ (Accessed August 3, 2023).

Sibeko, B., and Isaacs, G. (2019). The cost of austerity: lessons for South Africa. Institute for Economic Justice Working Paper Series.

Siegelaar, L., and Ballard, H. H. (2023). An evidence-based social crime prevention approach for community participation in the prevention of violent crime. Admin Pub 31, 1–22.

Somduth, C. (2023). Five years later & still no traffic cameras in eThekwini. Available online at: https://www.iol.co.za/thepost/news/five-years-later-and-still-no-traffic-cameras-in-ethekwini-ec7c4460-5a08-472b-84fd-b0b0ab75918a (Accessed June 24, 2024).

South Africa Police Service. (2019). Annual crime report 2018/2019 addendum to the SAPS annual report. Availabe online at: https://www.saps.gov.za/about/stratframework/annual_report/2018_2019/annual_crime_report2020.pdf (Accessed May 12, 2024).

South African Cabinet. (2003). Cabinet memorandum. Available online at: https://www.gcis.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/resourcecentre/yearbook/2004/17safsec.pdf (Accessed May 8, 2024).

South African Human Rights Commission. (2012). Media statement issued by the SA human rights commission regarding the usage of blue lights by the SAPS VIP protection unit. Available online at: https://www.sahrc.org.za/index.php/sahrc-media/news-2/item/149-media-statement-issued-by-the-sa-human-rights-commission-regarding-the-usage-of-blue-lights-by-the-saps-vip-protection-unit (Accessed June 24, 2024).

South African Police Service. (2023a). Crime statistics, third quarter 2023/2024. Available online at: https://www.saps.gov.za/services/crimestats.php (Accessed May 12, 2024).

South African Police Service. (2023b). Speaking notes for police minister general Bheki Cele (MP) on the occasion of the release of quarter 3 crime statistics in Cape Town on 17 February 2023. Available online at: https://www.saps.gov.za/newsroom/msspeechdetail.php?nid=44808 (Accessed May 12, 2024).

Statista. (2024). Crime index in South Africa from 2014 to 2024. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1399476/crime-index-south-africa/#:~:text=In%202024%2C%20South%20Africa%20had,fluctuated%20between%2075%20and%2077 (Accessed May 13, 2024).

Statistics South Africa. (2023). Quarterly labour force survey (QLFS) Q2:2023. Available online at: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/Presentation%20QLFS%20Q2%202023.pdf (Accessed May 12, 2024)

Statistics South Africa. (2024). Quarterly labour force survey quarter 1: 2024. Available online at: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02111stQuarter2024.pdf (Accessed May 14, 2024).

Thorne, S. (2024). South Africa has a massive policing problem. Available online at: https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/783325/south-africa-has-a-massive-policing-problem/ (Accessed July 26, 2024).

Wehner, J., and Mills, L. (2022). Cabinet size and governance in sub-Saharan Africa. Governance 35, 123–141. doi: 10.1111/gove.12575

Wicks, J. (2010). WATCH: how to buy illegal blue lights in minutes. Available online at: https://www.news24.com/news24/watch-how-to-buy-illegal-blue-lights-in-minutes-20160531 (Accessed April 11, 2024).

Williams, J. K. (2018). A comprehensive review of seven steps to a comprehensive literature review. Qual. Rep. 23, 345–349. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2018.3374

World Bank. (2022). Inequality in southern Africa: An assessment of the southern African customs union. Washington DC: The World Bank. doi: 10.1596/37283

Wright, G., and Ribbens, H. (2016). Exploring the impact of crime on road safety in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 35th Southern African Transport Conference. 436–455.

Yesufu, S. (2021). Harmonising road transport legislation in the SADC region for crime prevention. Sage 13, 28–55. doi: 10.1177/0975087820965165

Zille, H. (2011). Blue light convoy a danger to society. Available online at: https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/opinion/columnists/2011-11-28-blue-light-convoy-a-danger-to-society/ (Accessed June 24, 2024).

Keywords: blue light gangs, crime, costs, inequality, security

Citation: Maphumulo MN and Masuku MM (2025) We are all equal: politics of very important people blue light security in South Africa. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1475435. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1475435

Edited by:

Ilia Murtazashvili, University of Pittsburgh, United StatesReviewed by:

Michael Humphrey, The University of Sydney, AustraliaAwosusi Oladotun Emmanuel, University of Fort Hare, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Maphumulo and Masuku. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mashimane Njabulo Maphumulo, MjIzMTQ3MTg1QHN0dS51a3puLmFjLnph

†ORCID: Mashimane Njabulo Maphumulo, orcid.org/0000-0002-0294-4713

Mfundo Mandla Masuku, orcid.org/0000-0003-3743-0779

Mashimane Njabulo Maphumulo

Mashimane Njabulo Maphumulo Mfundo Mandla Masuku

Mfundo Mandla Masuku