- 1Institute for Security Studies, Pretoria, South Africa

- 2School of History, Anthropology, Philosophy and Politics, Queen's University Belfast, Belfast, United Kingdom

In Mozambique, systematic electoral fraud has persistently prevented the will of the electorate, as expressed at the ballot box, from being reflected in the selection of national leadership. This has resulted in recurrent post- electoral conflicts between the main opposition parties and ruling authorities, often addressed through political agreements and legal reforms aimed at preventing future irregularities. Although successive electoral reforms have improved transparency and expanded access to independent domestic and international observation, election rigging continues. Recent trends reveal an increasing reliance on the state apparatus—including legislative bodies, electoral commissions, the police, and the—judiciary to influence electoral outcomes. This article draws on a review of relevant literature, key informant interviews, and both direct and indirect observation to examine the evolution of electoral fraud in Mozambique. It demonstrates how fraudulent practices have become sophisticated to adapt to a society with growing access to information and heightened civic awareness. The paper argues that the systemic manipulation of electoral processes by state institutions has eroded the credibility of democratic institutions and may foster organized political violence, posing serious threats to peace and political stability.

1 Introduction

Mozambique has existed as an independent state for 50 years, half of which were marked by armed conflicts, from a long-scale civil war (1976–1992) to a small-scale post-election conflict (2013–2016), and the current jihadist insurgency in the northern province of Cabo Delgado (2017-present) (Morier-Genoud, 2020). Immediately after it won political independence from Portugal, the former liberation struggle movement, Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO), denied the existence of other political parties (Lundin, 1995, p. 466). The option for a one-party regime was one of the key causes used by the Mozambique National Resistance (MNR) to mobilize and sustain a civil war against the FRELIMO-led government (Resistência Nacional Moçambicana, 1981, p. 7). The rebel group demanded, among various reforms, the holding of elections to choose the government. In 1990, still during the civil war, a constitutional reform instituted liberal democracy, allowing multi-party free and fair elections to choose the country's leaders. The constitutional reform was key for the signing of the peace agreement 2 years later, in 1992, which ended the civil war.

Mozambique has held regular multiparty elections since 1994, welcomed international and domestic observers, and adopted multiple electoral reforms. Yet these elections have remained systematically fraudulent. Despite the formal appearance of democracy, the will of the electorate has consistently failed to translate into genuine political change (Hanlon, 2021; Do Rosário and Guambe, 2023). Why has Mozambique, after more than three decades of electoral reform and democratization, failed to hold free and fair elections? Why does electoral fraud persist—and even evolve—despite widespread scrutiny and growing civic awareness?

This article documents how electoral fraud has evolved over three decades, preventing the exercise of effective democracy in Mozambique. It demonstrates that Mozambique's persistent electoral fraud is not merely the result of technical or procedural weaknesses, but rather a deliberate strategy by the ruling party, FRELIMO, to maintain its political dominance. Over time, electoral manipulation has become increasingly institutionalized, involving the coordinated use of state institutions—including the legislature, judiciary, police, and electoral management bodies—to influence outcomes. As electoral observation and civic oversight have intensified, so too have the sophistication and scale of manipulation. It also offers an analysis of how election rigging undermines the credibility of democratic institutions, risking the emergence of organized political violence.

Methodologically, the article resorted to a qualitative research approach. The documentary research included reports of independent electoral observers, issued by local and international electoral observation missions. Reports published by Mozambican Political Process Bulletin, edited by Joseph Hanlon, which have covered all electoral processes in Mozambique since 1994, and reports from the European Union Electoral Observation Mission, which also observed all the elections in Mozambique, were exhaustively consulted. The Research also relied on historical documents on the civil war, mainly MNR's internal documents that explain the causes of the civil war it waged against FRELIMO's single-party regime. Twenty-eight (28) Key Informant Interviews (KII) with selected electoral officials, both active and retired, were used to obtain relevant information. Interviewees have been kept anonymous due to the sensitive nature of the information covered. Finally, the article includes information gathered from electoral observation by the author, who was part of the editorial team of the Mozambique Political Process Bulletin for five elections in Mozambique, three local elections (2013, 2018 and 2023) and two national elections (2014 and 2019).

The article is structured in three sections. The first section discusses the theoretical framework of democracy, elections, peace and stability with a focus on Mozambique and includes a subsection on the historical context of the introduction of liberal democracy and the multi-party elections in Mozambique. It is argued that with the introduction of multi-party elections (combined with other social and economic reforms), it was possible to end the civil war in Mozambique, however, the elections were never free or fair. The second section demonstrates how the elections in Mozambique are manipulated to benefit the ruling FRELIMO. It is argued that the rigging strategies and tactics have evolved over time to cope with the growing electoral observation, which keeps exposing election rigging schemes in social networks. Currently, the election rigging is conducted by the state apparatus, engaging the democratic institutions such as the Parliament, police, electoral management bodies, and the judiciary (courts) in election rigging. The third and final section analyses the dangers of electoral rigging. It argues that rigging has resulted in small-scale post-election wars and the discrediting of democratic institutions. If occurring for a long time, rigging can lead to the emergence of organized political violence as an alternative to power change.

2 Democracy as a peacebuilding mechanism in post-cold war Africa

Following the end of the Cold War, a wave of democratization swept across sub-Saharan Africa, often promoted by international actors as a condition for peace, aid, and development (Bratton and van de Walle, 1997; Ottaway, 2003). Many authoritarian regimes transitioned to multiparty systems not through domestic demand alone, but also in response to global shifts in norms and funding criteria. In post-conflict settings, elections were increasingly framed as mechanisms for restoring political order and fostering reconciliation. Zürcher (2011) cautions, however, that democratization and peacebuilding, though often pursued simultaneously, can operate at cross purposes. Where elections are introduced rapidly, without addressing structural grievances or building trust in institutions, the risk of renewed instability increases. In such contexts, democratic competition may entrench power struggles rather than resolve them, particularly when dominant elites manipulate electoral processes to maintain control.

Mozambique's path to democracy fits this broader pattern. After nearly two decades of civil war between FRELIMO and RENAMO, the 1990 Constitution introduced multiparty elections and a liberal democratic framework as part of the peace process. However, this shift was largely elite-driven and did not dismantle the centralizing legacy of FRELIMO's one-party rule (Manning, 2002). As Sitoe (2020) notes, while Mozambican constitutions proclaim that sovereignty resides with the people, in practice, they have reinforced FRELIMO's institutional dominance. The 1975 Constitution openly declared FRELIMO as the leading force in state and society—a position that, though reworded, remained embedded in subsequent constitutional revisions, including those of 1990 and 2004.

The dominance of FRELIMO is not merely legal or institutional; it is also historical. Mazula (2000) describes this as a “complex of ownership of historicity,” whereby the party's role in achieving independence has been used to justify its continued monopoly on power. Institutions created to ensure electoral integrity, such as the National Electoral Commission (CNE) and the Technical Secretariat for Electoral Administration (STAE), have repeatedly been criticized for their lack of independence and for being heavily politicized (De Brito, 2008).

Mozambique's early electoral processes were marked by optimism and high levels of participation. The first multiparty elections in 1994 saw a turnout of 88%, reflecting widespread public enthusiasm for peace and democratic renewal (Manning, 2002; Barnés, 1998). However, this enthusiasm gradually gave way to skepticism. By 1999, voter turnout had declined to 74%, and subsequent elections witnessed further reductions (Silva, 2016). This trend reflects growing public disillusionment with a system perceived as unresponsive and increasingly fraudulent.

Electoral legitimacy has been further eroded by the recurring refusal of RENAMO to accept electoral results. Since 1994, the main opposition party has consistently contested election outcomes, citing procedural irregularities, vote rigging, and restrictions on political freedoms. Azevedo-Harman (2015) notes that such allegations are not unfounded: elections have often been marred by flawed voter rolls, biased media coverage, and lack of transparency in result tabulation. While elections have helped maintain a degree of political order, they have also served to entrench a system of “managed competition” in which FRELIMO retains power with minimal accountability.

Zürcher (2011) framework offers a useful lens through which to interpret Mozambique's trajectory. He argues that in post-conflict societies, elections are often implemented not as instruments of genuine democracy, but as part of elite bargains aimed at pacifying violence. When these processes fail to institutionalize democratic norms or protect political pluralism, they risk reproducing the same tensions they aim to resolve. In Mozambique, the initial elite pact between FRELIMO and RENAMO allowed elections to substitute for war, but failed to dismantle the underlying structures of authoritarian control. As a result, the country has developed what Levitsky and Way (2010) term a “competitive authoritarian” regime, where formal democratic institutions exist but are systematically undermined to ensure regime continuity.

2.1 A war for elections

After winning political independence from Portugal in 1975, Mozambique was ravaged by a civil war that only ended after far-reaching constitutional reforms. These reforms essentially involved abandoning the one-party regime and introducing liberal democracy and multi-party elections to choose the country's leaders. The constitutional reforms were approved in 1990, and 2 years later, in 1992, a General Peace Agreement was signed between the warring groups. The first democratic, multi-party elections were held in 1994, with the main contenders being the two former warring groups, FRELIMO (the government) and the former rebel group Mozambique National Resistance, which had now changed its acronym to RENAMO or Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (Mozambican National Resistance).

With this, it can be clearly said that the constitutional reform of 1990 to allow for liberal democracy and multi-party elections was key to the establishment of peace. Of course, one must not ignore other internal social and economic factors that contributed to the end of the civil war in Mozambique, as well as important geopolitical changes that occurred in the same period in Southern Africa, such as the end of apartheid in neighboring South Africa and, on an international level, the fall of the Berlin Wall marking the end of the Cold War. All this contributed to some extent to the end of the civil war in Mozambique (Pavia, 2000, pp. 49-50).

Some scholars debate whether, in waging civil war against the Mozambican government, RENAMO's main demand was the introduction of liberal democracy and, above all, the holding of elections to choose state leaders. These are the cases of Vines (1996) and Hanlon (2006), prominent English scholars of Mozambican politics, who argue that RENAMO waged war against the socialist FRELIMO government essentially because of economic demands. The external support that RENAMO obtained from the minority regime in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and later from the Apartheid regime in South Africa after Zimbabwe's independence in 1980 meant that many players, especially those sympathetic to FRELIMO, initially refused to treat the war in Mozambique as a civil war1. These scholars tended to classify the conflict between the MNR and the Mozambican government as a proxy war waged by the white minority governments of neighboring countries against the socialist FRELIMO government.

However, several scholars of the Mozambican civil war agree that this conflict, despite having a proxy war element, was, above all, a civil war. MNR survived the end or drastic reduction of external support from South Africa and Rhodesia and began to feed on domestic dynamics in Mozambique (Finnegan, 1993; Morier-Genoud et al., 2018; Emerson, 2019). Furthermore, the histories of the war written by intellectuals who directly supported RENAMO during the civil war show with material evidence that RENAMO always had a political objective behind the war, namely the introduction of democracy and the free choice of leaders (Thomashausen, 1987; Cabrita, 2000). RENAMO's historical documents dating from the early 1980s, namely the first Manifesto and the first Political Programme of RENAMO, both published in 1981, show that one of the main political foundations of struggle was the demand for the introduction of a democratic political regime, in which the President of the Republic and the members of the National Assembly would be chosen in “free elections.” In these terms, the right of the people to freely choose the leaders of the state was part of RENAMO's political demands. This is contained in the first Political Programme of the Mozambican National Resistance (MNR) published in 1981 (Resistência Nacional Moçambicana, 1981).

“... Our aim is to democratize, liberalize and create conditions for generalized progress in the future republic of Mozambique (...) the people have the right to choose and will freely vote on the country's political, social and economic system. Nothing will be imposed on the majority by a minority” (Resistência Nacional Moçambicana, 1981, p. 7).

In another historic document, dated 1982, called Base Política (Political Basis), the then Mozambican National Resistance once again reaffirmed with special emphasis the need to institutionalize democracy in Mozambique, this time using the specific term multi-party democracy and setting a deadline of 2 years after the end of the civil war for elections to be held to choose the President of the Republic and later members of the National Assembly (Parliament).

“The political regime will be semi-presidential, and the President, elected by the People, will appoint a Prime Minister whose actions will be approved and supervised by the National Assembly” (Resistência Nacional Moçambicana, 1982, p. 1).

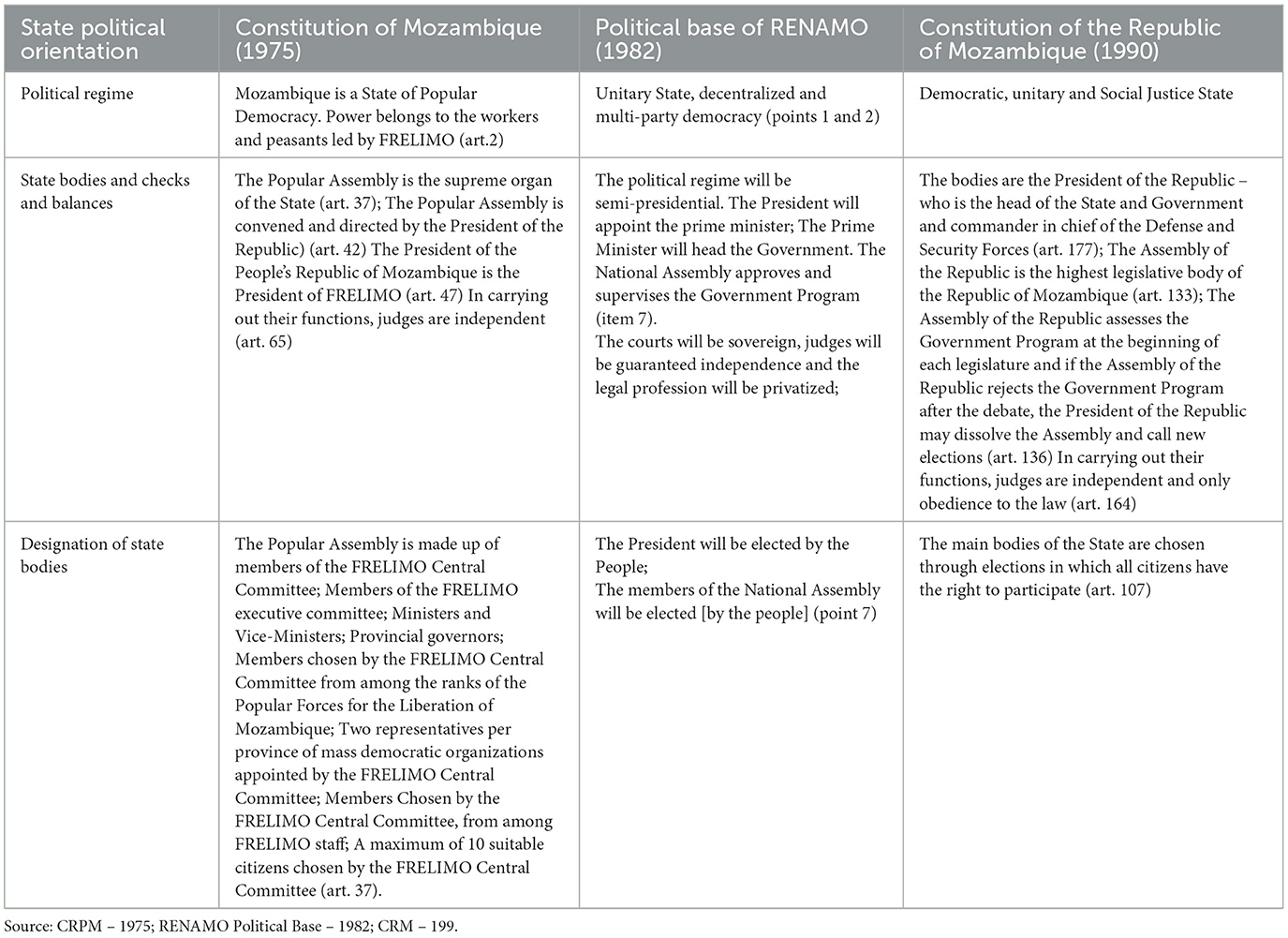

Remarkably, the 1990 Constitution—drafted solely by FRELIMO legislators—incorporated nearly all ten principles from RENAMO's 1982 Base Política. A comparison of key elements, including regime type and separation of powers, reveals that RENAMO's political blueprint heavily influenced the constitutional reforms that underpinned peace negotiations and shaped Mozambique's democratic framework (see Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of the Constitution of the People's Republic (1975) Political Base of RENAMO (1982) and Constitution of the Republic of Mozambique (1990) in the political component.

By adopting the political basis of the state that coincides with what was proposed by RENAMO, through the approval of a new Constitution, the FRELIMO government has emptied the cause of RENAMO's struggle. At the peace negotiating table, which was already underway, FRELIMO could only say that the demands that RENAMO used to justify the civil war no longer make sense, simply by showing the new Constitution of Mozambique.

Regarding democracy and elections, the 1990 Constitution introduced multi-party democracy in Mozambique, with respect for democratic pluralism and the appointment of state leaders through multi-party and universal elections. All it took was for the war to end for elections to be organized. With that done, the two former belligerents have become the main political parties vying for power through multiparty and universal elections. However, allegations of electoral fraud have already led RENAMO to boycott its participation in elections and to the resurgence of small post-election conflicts more than once, putting the former belligerents against each other in a small-scale war in 2013 and in 2016.

Zürcher (2011) argues that introducing democratic competition too quickly in fragile post-conflict societies does not guarantee peace, particularly when undemocratic practices such as electoral manipulation persist. This is evident in Mozambique, where, despite the absence of a likely return to civil war between FRELIMO and RENAMO, continued election rigging in favor of FRELIMO threatens the credibility of democratic institutions. When the will of voters is persistently denied through fraud, elections lose legitimacy, and over time, political organizations may turn to alternative, potentially violent means to gain power.

3 From electoral fraud to its institutionalization in Mozambique

This section presents and discusses the manifestation of electoral fraud in Mozambique and describes how it has evolved in the face of increasing scrutiny through independent electoral observation carried out by local and international organizations that expose election rigging evidence in the social network.

Since Mozambique began holding elections, it has never missed or delayed an election, making it an example of respect for the people's right to choose their leaders, at least formally. However, on a material level, it is different. FRELIMO won all the presidential, parliamentary, provincial assembly and governor elections. It only lost a few municipal elections to two opposition parties, RENAMO and the Democratic Movement of Mozambique (MDM). The opposition has never accepted defeat, always alleging electoral fraud (De Brito, 2008), and in some cases, the allegations of fraud have led to the emergence of post-election violent conflict (2013 and 2016), stemming from allegations of fraud in the 2009 and 2014 general elections.

So far, the election fraud has been mostly done by individuals who could be public servants and even election officers, but acting in their own capacity. However, since the 2018 municipal elections, State institutions have been leading the manipulation of elections in Mozambique, operating under an authoritarian regime model. This shift resulted in Mozambique being classified as an authoritarian regime in The Economist's Global Democracy Index (Nhamirre, 2023). This model of electoral manipulation through State institutions persisted during the 2023 local elections and the general elections of 2019 and 2024. Following the 2023 local elections and the 2024 national elections, a new wave of violence emerged, characterized by widespread protests, particularly in urban areas (Freischlad, 2024). Led mainly by young people contesting the alleged rigging of election results, the unrest resulted in significant casualties (International Crisis Group, 2024). Although no armed conflict occurred, the post-election violence in 2024 led to over 300 deaths, including approximately a dozen police officers who were stoned to death by enraged crowds of young protesters (Dube, 2024; Nhamirre, 2024).

Pitcher (2012) shows that in many African democracies, formal electoral processes coexist with persistent ruling party control, where institutions are reshaped to serve regime interests. In Mozambique, having democratic institutions that lead to election rigging reflects what Sitoe (2020) called FRELIMO's central role in shaping the national political landscape. Birch (2011) defines electoral malpractice as deliberate attempts to manipulate electoral outcomes through illegal or unethical means, which can include vote-buying, intimidation, fraud, and the manipulation of electoral rules or procedures, categorizing election rigging into three broad areas, manipulation of the electoral process such as biased voter registration, manipulation of the campaign environment, citing media bias and, intimidation, and manipulation of the vote count and results, referring to vote tampering, fraudulent counting.

All the forms of electoral manipulations described by Birch are seen in Mozambique. And manipulation has evolved from tampering with the electoral results in favor of the ruling party to authoritarian state mechanisms, in which courts—electoral bodies included—that are formally independent have informal practices to ensure that judges do not rule against the ruling party's interests, especially when political opposition is involved. Thus, cases of illegal interference in elections that benefit the ruling party are brought before the electoral bodies and courts for judgment; However, despite the evidence presented, the decisions made tended to benefit the ruling party. A notable example is the 2023 municipal elections, in which RENAMO submitted compelling evidence that it had won in seven contested municipalities. Nevertheless, the Constitutional Council—Mozambique's highest electoral court—declared Frelimo the winner in key cities, including the capital, Maputo, while awarding RENAMO victories in only four less significant municipalities (RFI, 2023).

Election rigging in Mozambique is carried out by individuals and civil servants within State institutions. The list of public officials involved in electoral fraud is extensive, including electoral body officials who manipulate voter registration data in specific constituencies to disadvantage opposition parties and benefit the ruling FRELIMO party, as well as electoral court judges who issue biased rulings favoring the ruling party or deliberately abstain from making decisions that could harm it (Hanlon, 2021; Do Rosário and Guambe, 2023). Having civil servants and state institutions actively engaged in election rigging to benefit the ruling party reflects what Mazula (2000) observed as a strong “complex of ownership of historicity” within the party, leveraged to maintain political control.

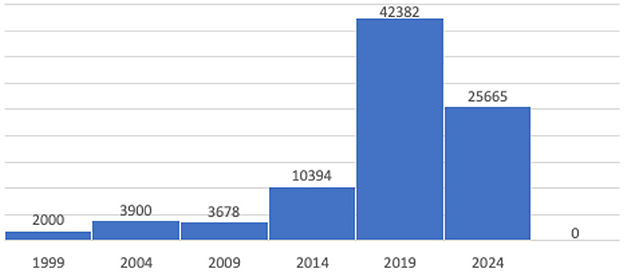

The more traditional forms of fraud that occur in Mozambique have, over time, become easier for election observers to detect. Such forms include stuffing ballot boxes with ballot papers already pre-marked in favor of the ruling party (CIP Eleições, 2019b), disabling opposition votes by polling station staff during the count (CIP Eleições, 2019a), changing names on the electoral roll to prevent voters from voting in constituencies favorable to the opposition (Hanlon, 2018b). On the other hand, there has been an increase in the observation of elections over time, by political party inspectors, independent domestic and international observers, which has made the practice of traditional fraud more difficult and, above all, riskier due to the danger of being exposed. Electoral legislation in Mozambique allows any person interested in observing the electoral process to do so if they register with the National Electoral Commission. Observers can be national or international, individuals or affiliated to organizations. Thus, as can be seen in Figure 1, over the years, there has been an increase in independent national election observers.

Figure 1. Evolution of the number of independent national election observers at national elections in Mozambique (1999 to 2019).

In the 1999 elections, around 2000 national observers were accredited (Hanlon, 2000), and in the 2004 elections, this number almost doubled to around 3,900 (Hanlon, 2004). In the following elections in 2009, the number of national observers was slightly reduced to 3,678 (Conselho Constitucional, 2009), but in 2014, the number increased almost threefold to 10,394 (Conselho Constitucional, 2014). The highest number of national observers ever registered in Mozambique's history was reached in 2019, with 42,382 accredited observers (Conselho Constitucional, 2019).

Parallel to the increase in the number of observers, the evolution of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) meant that people started using smartphones and social networks to register and report irregularities, and traditional electoral fraud practices started to be photographed and exposed on social networks. Thus, equipped with smartphones, election observers detected cases of traditional electoral fraud, photographed or filmed them and published them on social media, making the perpetrators more exposed to social criticism, running the risk of being sanctioned by the courts on charges of electoral offenses. With the intervention of observers armed with smartphones to record cases of fraud, polling station presidents were arrested in different places trying to insert extra ballot papers into the ballot boxes in favor of the ruling party FRELIMO (Hanlon, 2014).

Then, from the 2018 and 2019 electoral cycle onwards, there was the sophistication and institutionalization of election rigging, and this continued until the 2023–2024 electoral cycle. The sophistication of fraud means that the manipulation of electoral results is no longer predominantly through stuffing ballot boxes or rendering opposition votes unusable, but through the manipulation of decisions made by State institutions that intervene in the electoral process. Key institutions, such as Parliament, pass electoral legislation designed to favor the ruling party, including the introduction of the principle of prior contestation in electoral disputes. This mechanism is used to block opposition appeals in electoral courts (Salema, 2023). The police intervene in the electoral process with violence, intimidating, physically assaulting, and even killing opposition leaders and independent observers, in short, creating an atmosphere of fear to prevent the acts of election rigging from being challenged (Bearak, 2024). This set of fraudulent actions is called here rigging by the State apparatus.

3.1 The manipulation of vote counts and results

The stuffing of ballot boxes in favor of the ruling party, FRELIMO, and the nullifying of opposition votes are two of the most traditional forms of election rigging that continue to be practiced by the electoral management bodies, or with their intervention. During the vote, the competing political parties have the right to appoint inspectors to oversee the voting process, but they are unable to do so fully. Voting begins at 7 am and ends at 6 pm if there are no more people in the queue. There are cases where it extends to 7 pm if there are people waiting. Once voting is over, the counting of votes at the polling station follows, which lasts until around midnight and, in some cases, until the early hours of the morning. In the 2019 presidential elections, there were 20,000 polling stations (Caldeira, 2024), and in the 2023 local elections, there were just over 6,700 polling stations (Lusa, 2023).

In the context of electoral fraud practiced by the electoral management bodies, opposition parties should have been able to appoint at least two inspectors for each of the polling stations to ensure full coverage of the stations during voting and counting. This way, if one inspector was absent to attend to some biological need, the other would be there to monitor the voting and counting of results. Nevertheless, the opposition parties do not have this capacity. The only party that manages to place inspectors at all the polling stations is the party in power, FRELIMO, which uses civil servants, especially primary and secondary school teachers, as inspectors.

There are often cases in which polling station presidents expel opposition inspectors from polling stations, accusing them of obstructing the vote, and in cases where the inspectors refuse to be expelled, the presiding officer calls the police and orders the arrest of the opposition members. In the 2019 elections, an emblematic case occurred in the province of Gaza, a FRELIMO stronghold, in which around 200 inspectors from a new party called New Democracy were expelled from polling stations and 17 were arrested and held in prison for months for refusing to comply with the expulsion orders (Hanlon, 2020). The absence of opposition inspectors, whose coverage is very low for the number of polling stations set up, allows ballot boxes to be stuffed in favor of the ruling party, FRELIMO, but also for opposition votes to be suppressed, either by making the ballot papers in favor of the opposition unusable or simply by undercounting the opposition votes deposited in the ballot box.

In a study relating to the 2019 general elections, it was concluded that by combining the schemes of ballot box stuffing, the destruction of opposition votes, registration inflation in constituencies favorable to FRELIMO and under registrations in constituencies favorable to RENAMO, this allowed the FRELIMO candidate to be fraudulently allocated 371,691 votes and the opposition to be fraudulently removed 105,945 votes (Hanlon, 2019). In the 2023 local elections, according to studies by the Center for Public Integrity, there was ballot box stuffing in favor of FRELIMO and suppression of RENAMO votes in at least 18 of the 65 municipalities (CIP Eleições, 2023b), and because of this, the National Elections Commission sidelined RENAMO in 5 cities, including the capital Maputo, and in Mozambique's most populous city, Matola, with the loss of 180,000 RENAMO votes and the addition of ghost voters (CIP Eleições, 2023a).

After the end of the vote, the law requires the counting of votes at the polling stations to begin immediately. However, the presiding officers at several polling stations do not immediately start counting the votes, in violation of the electoral law. In the 2023 local elections, in the municipalities of Nampula, Nacala Porto, Gurué, Quelimane, Maputo city and Matola, where the opposition had the potential to win the election, the counting process started late evening (Peyton and Mucari, 2024). The delay in starting the vote count tired out the independent observers and party agents, who were tempted to leave the polling stations. Observers and opposition party agents who were absent from the polling station for any reason during this interregnum are forbidden to enter the room when they return.

Election results are also changed in the intermediate tabulation process. The intermediate tabulation consists of adding up the tallies from the polling stations. This is done by a District Election Commission, where FRELIMO has the majority of members due to the principle of proportional representation of political parties in electoral bodies approved in 2023 by the Parliament and which was at the root of the resurgence of war. In the intermediate tabulation, notices of results from the polling station were invalidated or disqualified due to the absence of a stamp, signature or any other pretext whenever the results of the notices were in favor of the opposition parties. Tabulations are made using false notices, the provenance of which is unknown. In the 2023 local elections, these practices were proven in some district electoral courts, such as the cases of Kaphumo, KaMavota, Nlhamakulo (Maputo City), Matola (Maputo province), Chókuwè (Gaza province), Cuamba (Niassa province) and Alto-Molócue (Zambézia province), which canceled the elections in these places (Fernando, 2023). The decisions of the electoral courts were later reversed by the Constitutional Council (whose actions will be discussed below). Regarding fraud in the tabulation of results, The Carter Center's electoral observation mission for the 2003 local elections stated that “the tabulation process still suffers from a lack of transparency, due to the absence of satisfactory conditions for adequate observation of the process or verification of the data” (The Carter Center, 2004, p. 33).

3.2 Manipulation of the campaign and electoral environment

In the architecture of electoral fraud using the State apparatus, the police play a fundamental role in intimidating opposition leaders and civil society organizations dedicated to monitoring the electoral process. Arbitrary arrests of opposition inspectors to prevent them from observing the voting process and the counting of votes at the polling stations and excessive violence against citizens protesting against electoral fraud are the most common forms of intimidation employed by the police (Lusa, 2023).

However, an extreme case occurred on the eve of the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections, when a civil society leader and election observer was murdered in broad daylight by officers from a special police unit, as he was leaving an opening session for the training of election observers in the town of Xai-Xai, the capital of Gaza province, a FRELIMO stronghold (Al Jazeera, 2020). National and international election observers, including those from the European Union Election Observation Mission, the Commonwealth and the United States (US) Embassy, condemned the murder of the election observation leader a few days before the elections and in their election observation reports linked the murder to electoral violence.

Some of the police officers who murdered the election observer were found and tried for a literally accidental reason, as the car they were driving to try to escape from the place where they murdered the observer was involved in a road accident and some of its occupants died at the scene and others were caught with blood on their hands (Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 2019). Meanwhile, the leader of the group managed to escape and was never found again. During the trial that took place years later, the policemen said that they had been hired by their now fugitive colleague to murder the civil society leader for personal reasons (Zitamar News, 2019). However, they turned to a famous FRELIMO supporter for his defense, who 5 years later ran for deputy of the Parliament on the FRELIMO list (Lusa, 2020).

Although the police officers who murdered the leader of an electoral observation group have maintained that they acted out of private motives, in its final report, the European Union Election Observation Mission in Mozambique directly linked the murder of the electoral observation leader to police misconduct in electoral processes, stating that the murder of the leading electoral observer further affects public confidence in the police in the electoral process.

“A lack of public trust was observed in the impartiality of the national police forces, often perceived as more supportive of the ruling party and not managing properly the election-related incidents and complaints. Distrust was further exacerbated just one week before elections with the assassination of a senior election observer, Anastácio Matavel, by active members of the police,” (EU EOM Mozambique, 2019, p. 21–22).

Several opposition leaders have been assassinated in Mozambique in the context of elections. A RENAMO district political delegate in Cabo Delgado was murdered in 2018 while waiting for the results of that year's local elections to be announced (RFI, 2018), and the president of the RENAMO Women's League in Zumbo District, Tete province, was also murdered along with her husband during the 2019 general election process (Catueira, 2019). All these cases have never been clarified and the killers have never been found, unlike the killers of the leading election observer, who were killed in a car crash shortly after committing the crime.

During the 2024 national elections, two prominent opposition members and aides to the runner-up presidential candidate were assassinated in Maputo, 10 days after the polls (Associated Press, 2024). One victim, Elvino Dias, was the lead attorney for Venâncio Mondlane, the presidential candidate, while the other, Paulo Guambe, was an electoral agent from the PODEMOS party, which supported Mondlane's candidacy. Local human rights organizations accused government-backed death squads of orchestrating the killings to obstruct legal challenges against the election results [Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD), 2025].

3.3 Rigging the electoral process: institutionalizing fraud

3.3.1 The parliament

Parliament, where FRELIMO has an absolute majority of seats, has contributed to institutional election rigging by approving electoral legislation that benefits the FRELIMO party, to the detriment of the opposition. Some blatant examples of this sophisticated fraudulent practice include the controversial prior contestation of electoral litigation and the electoral reform of municipal elections.

The principle of prior contestation of electoral litigation: this is a rule that imposes the obligation to first complain to an electoral body as a condition for appealing to the electoral court. This rule is manifestly unconstitutional because it makes access to electoral justice conditional on a complaint to a public administration body. In doing so, it restricts citizens' right of access to justice as provided for in Articles 69 and 70 of the Constitution of Mozambique, as well as preventing the judge from carrying out his judicial activity with a view to guaranteeing rights.

Similarly, the principle of prior challenge in electoral litigation violates the separation of powers provided for in Article 134 of the Constitution of Mozambique since it makes the exercise of the court's jurisdictional power conditional on a prior complaint by the offended party to a body of the electoral administration, which falls under the executive power. In the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections, the principle of impeachment was key to the rejection of opposition appeals against allegations of fraud. A total of 58 appeals were submitted to the electoral courts, and around 95% of the requests were rejected outright by the courts without analyzing the substance of the complaint. The main reason for the rejection of the appeals is that the complainants did not first submit the complaint to the electoral management bodies, a necessary condition for being able to complain to the court (RTP, 2019).

After these elections, there was a lot of opposition to the principle of prior challenge, which makes access to the court conditional on an administrative appeal. The Parliament revised the electoral law, and it was understood that the principle of prior challenge had been repealed (Salema, 2023). However, in the 2023 elections, it was once again applied by the courts to reject opposition appeals against allegations of election rigging, and the Constitutional Council declared that the prior challenge had not yet been declared unconstitutional, so it remained in force (Salema, op cit).

Another notable legal reform introduced by Parliament in 2018, which benefited FRELIMO and harmed the opposition, is the change to the electoral law that regulates municipal elections. In 2018, Parliament approved a reform of the electoral law establishing that the mayor will no longer be elected through an independent list but through a party list (coalition or citizens' group list). In this new model, the head of the list that obtains a simple majority of votes is declared mayor. This is a significant legal change to the model of local elections in Mozambique and one that has not been substantiated by Parliament. From 1998 to 2013, the model for electing mayors was by independent candidacy of party lists and to be declared the winner, the candidate had to obtain an absolute majority (50%+1 vote) and if no candidate managed to exceed 50%, the two most voted candidates would go to a second round between them. This is the model that is still used for the election of the President of the Republic.

With the legal reform introduced shortly before the 2018 local elections, FRELIMO was able to win in six municipalities despite failing to secure an absolute majority (50% + 1 vote). These included Matola (48.05%), Marromeu (47.13%), Moatize (48.84%), Alto-Molócuè (47.77%), Monapo (47.91%), and Ribáuè (46.75%) (Hanlon, 2018a). Had the 2023 municipal elections been conducted under the previous electoral law, FRELIMO would not have won these municipalities in the first round. A runoff between the two most-voted candidates would have been required, potentially allowing the opposition candidate to win by consolidating support from voters who had backed other opposition parties in the first round.

This means that the unsubstantiated legal reform introduced by parliament, where FRELIMO's parliamentary group has a qualified majority to pass any legislation regardless of how the opposition votes, facilitated FRELIMO's victory in six of the 53 municipalities. In the polarized Mozambican political context between FRELIMO in power and RENAMO in opposition, in a run-off election, there is a considerable chance that the opposition candidate will win since the other small parties tend to vote for the opposition candidate because of pre-election agreements.

3.3.2 The national electoral commission

In Mozambique, electoral processes are carried out by the Technical Secretariat for Electoral Administration (STAE), an operational arm of the National Electoral Commission (CNE), which has the task of overseeing the electoral process, from voter registration, receiving, evaluating and approving or rejecting candidacies, allocating state funding to the parties approved to run, organizing the vote to counting and publishing the results, before they are ratified by the Constitutional Council, which acts as a Supreme Electoral Court.

Throughout this process, the National Electoral Commission makes and implements decisions that benefit the ruling party and harm opposition parties. Such decisions include, for example, inflating the number of registered voters in constituencies that mostly vote for FRELIMO and under-registering voters in constituencies that generally support the opposition, up to and including suppressing the votes of opposition candidates. Details of how this sophisticated election rigging takes place are presented below. First, it is explained how a National Electoral Commission which, under the terms of the law, “is an independent and impartial organ of the State (...) and in the exercise of its functions, owes obedience only to the law,”2 instead of acting in defense of democracy, acts in the service of the ruling party, undermining and threatening democracy.

It all starts with the composition of the CNE, which was deliberately designed to ensure that FRELIMO has control over the body's decisions. The Parliament approved the current structure of the CNE in February 2013, about 6 months before local elections were held.

The 2013 local elections were very important because there was great potential for the opposition to win in many towns. President Armando Guebuza was in the penultimate year of his second and final presidential term (2009–2014). His rule had been very unpopular, with rising prices for food and other basic services leading to a huge popular demonstration in the capital of Maputo and the country's main urban centers on 1 and 2 September 2010. What was known as the hunger demonstration was very violent and the government reacted badly, ordering the police to fire tear gas grenades and real bullets, killing at least 10 people, including two children, and arresting at least one and a half hundred people on the first day of the demonstration alone (Esquerda, 2010). The popular demonstration was just a violent expression of the urban population's frustration with the government, which had increased bread prices by 17%, electricity tariffs by 13.4%, petrol prices by 8%, cooking gas by 7.9% and piped water by 2 meticais in a short space of time (De Brito et al., 2015, p. 28). In 2012, a year before the elections, another strike took place due to the threat of demonstrations.

The government was aware of its unpopularity, especially in the urban centers, and the way people would react would be to vote for the opposition in the 2013 municipal elections. To avoid the risk of losing elections in important cities, including the capital Maputo, the government submitted to parliament a proposal to change the law that defines the composition of the National Electoral Commission to ensure that it has full control of the important electoral management body. The new law approved around 6 months before the elections defines that the absolute majority of the members of the National Electoral Commission are directly or indirectly appointed by the FRELIMO party. The government justified this composition by claiming that the National Electoral Commission should correspond to the parliamentary representation. RENAMO argued that all three parties with parliamentary seats should have the right to appoint an equal number of commissioners to the National Electoral Commission. This became known as the parity or proportionality dispute, in reference to the criteria that should be used for the parties to appoint CNE commissioners and was the subject of political negotiations between the government and RENAMO, but there was no consensus (Canal de Moçambique, 2013).

With a majority of seats in Parliament, FRELIMO won the dispute through the majority vote of its deputies and the new CNE Law was passed, so FRELIMO now controls the majority of CNE commissioners with voting rights. This ensured that FRELIMO could push through all the decisions of the electoral process regardless of how the opposition voted. RENAMO felt this was unfair and boycotted its participation in the 2013 local elections and began armed attacks against military and civilian targets in the center and north of the country, breaking for the first time a 20-year period of peace that followed the 1992 General Peace Agreement that ended the civil war (Regalia, 2017). Not even the resurgence of war was able to change the new composition of the CNE. FRELIMO went ahead with holding elections without RENAMO. The second largest opposition party, MDM, ran and won in four municipalities, including the capital cities of the three most important provinces after Maputo, namely Beira, Nampula and Quelimane, despite various allegations of fraud (Canal de Moçambique, 2013).

Since then, the National Electoral Commission has become a center for manipulating elections through unfounded decisions in favor of FRELIMO and against the opposition. Below is some evidence that the National Electoral Commission and its support bodies at provincial and district levels were the center of election manipulation.

One of the most notable cases of manipulation of the electoral process by electoral (and justice) bodies to benefit FRELIMO took place in Gaza province in 2019. The National Electoral Commission claimed to have registered 1.1 million voters in Gaza province, while the National Statistics Institute INE data indicates that there were 836,000 people of voting age there in the same period (Pitcher, 2020; Hanlon, 2020). In other words, the CNE extrapolated the number of voters by 329,000, more than forecasted by INE. The case was a national controversy because INE did not agree with the extrapolation of voter data and resigned from its post (Lusa, 2019). INE officials said at the time that, according to official projections, Gaza province would only reach this number of voters in 2040, which made it clear that the voter figures had been manipulated (Roque, 2019). With this extrapolation of the number of registered voters, Gaza jumped from being the second smallest electoral constituency in 2014 to the fourth largest, gaining eight additional seats in the Parliament (EU EOM Mozambique, 2019, p. 7). It is simple to understand the reason behind the extrapolation of the number of voters in Gaza province. Gaza is a FRELIMO stronghold. In all the parliamentary elections held in Gaza, FRELIMO has always won all the seats, so it was certain that increasing the number of seats in the Gaza constituency by eight would guarantee an additional eight seats for FRRELIMO in the Parliament. And so it was. In the 2019 elections, FRELIMO won all the seats in Gaza and benefited from the increase in the number of registered voters. The case of Gaza has made the headlines, but there are many more cases of systemic manipulation of the electoral register in order to enroll more voters in the provinces where the vote is preferentially for FRELIMO (Gaza, Inhambane, Cabo Delgado provinces) and enroll fewer voters in the areas of influence of the opposition (Nampula, Zambézia, Sofala, Niassa) (Carta de Moçambique, 2023b).

3.3.3 Other electoral management bodies

Another form of voter registration manipulation is through the constitution of priority lists of people to be registered. The electoral management bodies receive lists made up of FRELIMO members and sympathizers and give them priority at the voter registration offices, to the detriment of other voters waiting to be registered. After registering the people on the lists, there are systematic breakdowns of the voter registration computers, which are seen as intentional malfunctions and consist of the brigade leaders switching off the mobiles to prevent opposition supporters from registering (Caetano, 2023). And yet, another form of voter registration manipulation is the registration of voters living outside the municipalised areas, who are mobilized by the FRELIMO party and transported in buses to be registered in the municipalities so that they can vote as if they were resident there. This happens with the permission of the electoral management bodies that are responsible for carrying out the census (Carta de Moçambique, 2023a).

3.3.4 The courts

The courts are key players in the electoral process. They have the power to say the last word on the legality of electoral acts carried out by all those involved. In Mozambican electoral law, the Electoral Courts are the District Judicial Courts, which are responsible for judging electoral disputes at first instance in their district of jurisdiction. In Mozambique's current administrative division, there are around 150 districts, and in each district, there is a District Judicial Court. During the electoral cycle, the District Judicial Court fulfills the functions of the Electoral Court to judge all the cases that occur in its territory of jurisdiction.

Above the District Electoral Courts is the Constitutional Council, which acts as a Supreme Electoral Court. The Constitutional Council acts as a court of appeal for contentious electoral cases decided by the district courts and also acts as a court of single instance for contentious electoral cases against central electoral management bodies. In this case, acts carried out by the National Electoral Commission can be appealed to the Constitutional Council, and its decision is legally binding, i.e., it cannot be appealed. Examples of cases that can be appealed to the Constitutional Council are the decisions of the National Electoral Commission approving the general voter registration data, the final lists of candidates for the parliamentary elections, and the general tabulation of election results.

As a whole, the courts have the power to annul, validate or order the repetition of electoral acts such as voter registration, voting and the tabulation of election results. In a democratic state governed by the rule of law, contestants in elections and citizens in general expect the courts not to approve manifestly fraudulent electoral acts. However, what has been noticed is that in the context of rigging by State apparatus, the courts choose to reject the majority of electoral appeals without analyzing their content, as is the case with the 95% of electoral litigation appeals that were rejected outright by the courts in 2019 (AIM, 2019). In doing so, career electoral court judges prefer not to discuss the substance of appeals so as not to find themselves in the ridiculous situation of having to approve manifestly illegal cases. That is why they hide behind procedural errors in order to reject the appeals and, in this way, place the blame on the electoral actors for not having handled the electoral process properly, for not having gathered the necessary evidence, or for having filed the appeal in the wrong forum.

In the 2023 local elections, many courts received electoral litigation appeals from opposition parties challenging the election results approved by the District Election Commissions. The appellants demonstrated that the sum of the results of the partial tabulation acts (counting of votes at the polling stations) gave different results to those approved by the District Election Commissions. To prove that the results published were false, the appellants attached copies of the partial tabulation acts and asked the courts to compare them with the results presented by the district election commissions. This is an exercise in simple arithmetic, of having the votes added up on the basis of the minutes of results made available by both the electoral management bodies and the minutes made available by the competing parties that obtained them at the polling stations, and then comparing the results to see which party is right. However, many courts dismissed opposition appeals on the grounds that the copies of the minutes submitted by the appellant parties to prove that the intermediate tabulation was carried out on the basis of false minutes were not authenticated. This argument makes no sense and finds no legal support since nowhere in the Electoral Law does it require the use of authenticated results tabulation minutes, not least because it is impossible to authenticate copies of public notices without having access to the originals (Tempo, 2023). The minutes that are distributed to candidate delegates are copies and the courts have the legal and technical competence to verify their authenticity. This is an argument used simply to deny judgment on opposition appeals.

The Constitutional Council, acting as the supreme electoral court, also actively participates in electoral fraud, making decisions or abstaining from making decisions that ultimately harm the opposition and benefit the ruling party. One of the most emblematic cases of the Constitutional Council's inaction to curb electoral fraud is the manipulation of voter registration data in Gaza province, which benefited FRELIMO by more than 320,000 votes, corresponding to eight parliamentary seats as discussed above. RENAMO appealed to the Constitutional Council, demanding the annulment of the National Electoral Commission's decision approving the general voter registration data, arguing that through this decision, the National Electoral Commission had approved false electoral data for Gaza province. The Constitutional Council rejected RENAMO's appeal without judging its substance. It argued that it could not assess the merits of RENAMO's appeal because it had been submitted to the wrong body. According to the Constitutional Council, RENAMO should have challenged the decision of the Gaza Provincial Electoral Commission approving the voter registration data in the province. And by failing to do so, it could no longer appeal to the Constitutional Council, as this means that it was satisfied with the data published by the Provincial Electoral Commission of Gaza province, even though this data was not yet final and needed the approval of the National Electoral Commission (Conselho Constitucional, 2019). In short, the Constitutional Council refused to consider RENAMO's appeal, citing procedural errors, and FRELIMO benefited by winning eight parliamentary seats.

In the 2023 local elections, the Constitutional Council took what must be the most visible fraudulent action of all time. After a highly fraudulent election, in which FRELIMO was declared the winner in 64 of the 65 municipalities, the opposition parties appealed to the Constitutional Council to have the National Electoral Commission's decision declaring FRELIMO the winner annulled (Nhamirre, 2023). The appellants attached copies of partial tabulation notices (vote counts at polling stations) and handed them to the Constitutional Council to prove that the results published by the National Elections Commission were forged. The Constitutional Council asked the National Elections Commission to hand over the notices that were used to tabulate votes. On receiving the notices from the National Elections Commission, the Constitutional Council decided to analyse and change the election results approved by the National Elections Commission, without ordering a repeat count. In this process, the Constitutional Council removed more than 78,000 votes that the CNE had allocated to FRELIMO and distributed them among the two opposition parties, RENAMO and MDM, for various municipalities, including Matola, Maputo-Cidade, Vilankulo, Quelimane, Alto-Molócue, Chiure, Nampula (International IDEA, 2023). With these changes, RENAMO, which on the basis of the results approved and announced by the National Electoral Commission had not won a single municipality, was declared the winner in four municipalities, namely Quelimane, Alto-Molócue, Chiure and Vilankulo, and regained seats in the municipal assemblies of many municipalities (Voice of America, 2024). During the 2024 national elections, vote rigging was once again observed at the District Electoral Commission level during the vote-counting process. This manipulation resulted in 20 additional parliamentary seats being unlawfully allocated to FRELIMO (Reuters, 2024). However, the Constitutional Council later overturned these seats during the result validation phase, redistributing them to opposition parties (Conselho Constitucional, 2024).

What at first glance appears to be a good act of justice by the Constitutional Council, in correcting the fraud committed by the National Electoral Commission, returning more than 78,000 votes to RENAMO that had been lost by the CNE, actually hides a greater fraud practiced by the Constitutional Council itself. The electoral law does not order the Constitutional Council to recount votes. What the Constitutional Council must do when it detects errors made by electoral bodies that affect the final result is to annul these illegal acts and have them repeated. So, if the National Electoral Commission miscounted votes, what the Constitutional Council should do is order the vote counting to be repeated. The same would apply if the mistake had been made in the vote. The court would order the vote to be repeated.

The Constitutional Council, whose job it is to approve or disapprove of the electoral acts carried out by the electoral bodies, took on the role of electoral management bodies and recounted votes, redistributing them among the parties. This vote recount was carried out far from the electoral observation of the parties and independent observers, so it is not actually known what criteria the Constitutional Council used to remove 78,000 votes from FRELIMO and allocate them to the opposition, and the council itself did not give reasons on the basis of which law it acted in this way, which makes the decision highly suspect of being unlawful, since under the terms of Mozambique's Code of Civil Procedure, the courts must base their decisions on the law and the facts3. In doing so, the Constitutional Council minimized the fraud committed by the National Electoral Commission, but did not solve the problem of fraud. In fact, it approved fraud in other municipalities. A study concluded that the CNE took 180,000 votes from RENAMO (CIP Eleições, 2023a,b). Parallel vote counting data (PVT) indicated that RENAMO won in the municipalities of Maputo, Matola, Nampula, three of Mozambique's four largest cities, but their votes were lost by the National Electoral Commission and this loss was approved by the Constitutional Council (Consórcio Eleitoral Mais Integridade, 2023).

4 Systemic election rigging threatens peace in Mozambique

Although some scholars specializing in Mozambique's peace process, such as Maschietto (2016) and Bueno (2019), have questioned its effectiveness and sustainability, the country was also widely regarded as a success story of post-conflict democracies for two decades (1992–2012) (Weinstein, 2002; de Zeeuw, 2006; Macuane et al., 2018). However, this success story was clearly interrupted when an armed conflict broke out in 2013 between the former civil war belligerents, RENAMO and FRELIMO. One of the main causes of the renewed conflict was electoral fraud, with RENAMO's leadership accusing FRELIMO of manipulating elections to prevent RENAMO from gaining access to power, including through the drastic reduction of RENAMO's parliamentary representation. In 2009, RENAMO had achieved its worst electoral result ever, electing only 51 of the 250 members of Parliament compared, for example, to 112 it had elected in the 1994 inaugural elections [Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), 1994] or 117 it had managed to elect in 1999 [Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), 1999]. In the previous election, in 2004, RENAMO had already dropped to 90 deputies, yet the fall in 2009 was drastic [International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), 2009]. RENAMO accused FRELIMO of electoral fraud, as it has done in every election, but this time the situation was worse because it affected the survival of RENAMO itself as a political party. Political parties receive financial transfers from the State for their representation in the Parliament, and the amount transferred is proportional to the number of seats each party holds. Dropping from 90 deputies in the previous legislature (2004–2009) to 51 in the next legislature (2009–2014) not only meant that RENAMO would lose political space in parliament, but it also meant that it would lose around half of the money transferred by the state to parties with Parliamentary seats and important jobs for former deputies who would now have to return home, with no guarantee of finding work in another sector. In Mozambique, FRELIMO dominates the state and all senior State officials must be FRELIMO members, with very few exceptions. This is known as the “partisanship of the state” and was one of RENAMO's demands at the resumption of the violent conflict (RENAMO, 2015). In this context, former RENAMO MPs would have great difficulty finding work in the State and the private sector is also controlled by FRELIMO, so it was almost a given that former RENAMO MPs would be unemployed.

On the FRELIMO side, there was a discourse that the opposition should be “reduced to nothing” and that FRELIMO should have 100 per cent of the seats in Parliament. Two years before the 2009 elections, in an interview with the pro-government newspaper “Notícias,” an important political and military leader of FRELIMO, Mariano Matsinha, said that

“we are going to do everything necessary so that FRELIMO never leaves power (...) We want that in some time they don't even enter Parliament, that is, in the future, all the seats should be occupied by our deputies. I'm not in favor of wiping out the opposition, but it must remain insignificant (Filimone, 2007).”

The words of FRELIMO's political and military leader were replicated by FRELIMO members and the fraudulent practices in the 2009 elections, which led to RENAMO obtaining its worst electoral result ever, created the conditions for a return to political violence. RENAMO did not accept the 2009 election results and threatened that its 51 MPs would boycott Parliament, but the FRELIMO leadership did not accept dialogue with the opposition and went ahead with the formation of the government and threatened that if the 51 RENAMO MPs did not take their seats in Parliament, they would lose their mandates (Finita, 2010).

The emergence of a third political party capable of securing seats in Parliament, the Democratic Movement of Mozambique (MDM), was perceived as a threat to both FRELIMO and RENAMO. The two parties, with representation in electoral bodies, collaborated to exclude the MDM from 7 out of 11 electoral constituencies. Nuvunga and Salih (2010) interpreted this as an act of electoral manipulation aimed at weakening the new political player.

In 2013, the year of the local elections, Parliament passed a law reforming the composition of the National Electoral Commission (CNE), establishing proportional representation based on the number of seats held by parties in Parliament, as previously discussed. RENAMO, which had recorded its worst electoral performance in the previous elections, was entitled to only minimal representation on electoral management bodies. As a result, it would always be outvoted by FRELIMO, which held a majority. This also meant that thousands of RENAMO-affiliated individuals would lose potential employment opportunities in the district electoral commissions due to the party's reduced representation. In Mozambique, each of the 154 districts has a District Electoral Commission composed of 11 members, totalling 1,694 positions nationally. These posts are distributed among parties with seats in Parliament. If RENAMO were entitled to nominate half of the members per district, it could secure around 847 posts; if only one, that number would fall to just 150. While RENAMO supported the principle of proportional representation, the reform significantly reduced its influence and patronage capacity. FRELIMO, with its parliamentary majority, passed the reform despite RENAMO's opposition. RENAMO lost the political battle in Parliament—and chose to return to armed confrontation.

For more than a year, there were military attacks in the provinces where RENAMO had the most support from the population, costing dozens of human lives and destroying several infrastructures, including coal transport trains belonging to the Brazilian multinational Vale, which were attacked and the transport of coal temporarily suspended (Matias, 2014). The resumption of the war forced FRELIMO to return to dialogue with RENAMO for important political reforms, including the composition of the National Electoral Commission. FRELIMO maintained its majority on the electoral management bodies; however, it accepted that RENAMO would increase the number of members. In September 2014, Afonso Dhlakama, the president of RENAMO and Armando Guebuza, the President of Mozambique and FRELIMO, signed a cessation of hostilities agreement, which ended the conflict and allowed RENAMO to participate in the 2014 general elections (Al Jazeera, 2014).

The return to violent conflict helped RENAMO increase its number of seats in Parliament. It rose from 51 seats in 2009 to 89 seats in 2014 [International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), 2014]. However, RENAMO once again claimed that there had been electoral fraud and resumed military attacks in 2015 that would only end in 2019 with the signing of the Maputo Peace Accord, this time between the President of Mozambique and FRELIMO, Filipe Nyusi and the new leader of RENAMO, Ossufo Momade, who succeeded Afonso Dhlakama who died in 2018 (Peace Process Support – The Secretariat, n.d.). Since then, peace has prevailed between FRELIMO and RENAMO, but the continued manipulation of the elections could lead to a resurgence of the violent conflict, bringing the two former belligerents back to civil war and beyond. With the implementation of the Maputo agreement, RENAMO has completely disarmed itself and demobilized the thousands of former rebel men to rejoin society.

In 2023 and 2024, a violent wave of protests against electoral results, centered in urban areas, led to hundreds of deaths, damage to public infrastructure, and slowed economic growth. This unrest demonstrated that, despite RENAMO's disarmament, electoral fraud continues to have the potential to trigger political violence (Dias, 2025). The manipulation and electoral fraud to perpetuate FRELIMO in power were one of the main causes of the resurgence of war in Mozambique. RENAMO's disarmament and demobilization are no guarantee that the post-election violent conflict in Mozambique will end.

4.1 Rigging erodes the credibility of democratic institutions

In Mozambique, there is growing mistrust of democratic institutions such as Parliament, the courts, electoral management bodies and the police due to their involvement in acts of fraud. In its final version report, the European Union Election Observation Mission emphasized that “a lack of public trust was observed in the impartiality of the national police forces, often perceived as more supportive of the ruling party and not managing properly the election-related incidents and complaints (EU EOM Mozambique, 2019, p. 21). A survey concluded that distrust of electoral management bodies in Mozambique increased from 17 per cent in 2005 to 38 per cent in 2015 (Afro Barometer, 2017, p. 5). The problem with the lack of public trust in democratic institutions is that it threatens the very survival of the institutions of democracy. Lenard (2015, p. 54) explains that trust is central to ensuring the smooth functioning of the most basic of democratic institutions, thus, trust must prevail for these institutions to maintain support over time. This is because, for example, when there is widespread trust among a population, legislators can act knowing that their decisions will elicit voluntary compliance, and citizens trust legislators to make good decisions. On the opposite side, distrust is inimical to democracy in such a way that trust is a necessary feature of democratic survival (Lenard, 2015, p. 75).

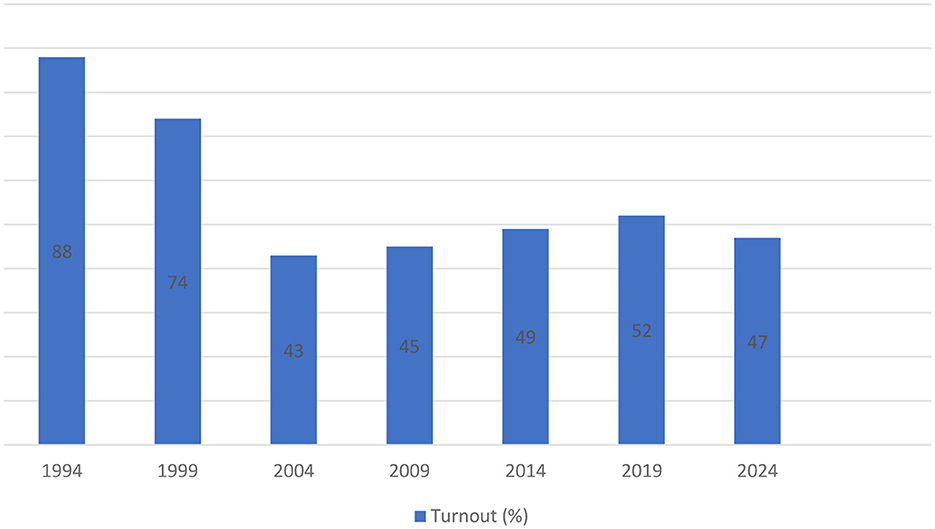

Without trust in democratic institutions, people stop actively participating in elections because they no longer believe that their participation will be respected by the institutions conducting the electoral process. This is notable in the history of the six general elections held in Mozambique, where participation dropped from 88 per cent in the first elections to a drastic 43 per cent 10 years later, in 2004. It then began a very slow recovery in the following election, and the average turnout in the last three elections has ranged from 45 per cent to 52 per cent (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Levels of participation in the seven general elections held in Mozambique (1994–2024). Source: Bulletin on the Political Process in Mozambique.

The problem with low turnout in elections is not just that people stop contributing to the choice of their political leaders. If people cannot trust democratic mechanisms to choose their leaders, there is a justified risk that people will start resorting to undemocratic means to force a change in power. If this were to happen, it would not be strange at all, given that the Mozambican regime itself has fallen in the 2018 Democracy Index from hybrid to authoritarian, prompted by the rigged 2018 elections, which observers inside and outside Mozambique widely criticized for unlawfully favoring the ruling FRELIMO (Nhamirre, 2024). This could lead to the breakdown of the social contract, which in the short term has unnoticeable implications, but in the medium and long term, the implications are very negative and could include people rebelling or easily becoming radicalized against the state and its institutions. Maintaining peace and harmony in society then becomes more difficult, and social order is jeopardized.

5 Conclusion

Following 16 years of civil war, Mozambique embarked on a multi-party democratic path that has sustained a relative peace. However, this post-war stability has been consistently threatened by systemic and recurrent electoral fraud. The 1992 General Peace Agreement ended formal hostilities between FRELIMO and RENAMO, transforming armed confrontation into electoral competition. Yet this shift from battlefield to ballot box did not dismantle the authoritarian structures inherited from FRELIMO's one-party rule, nor did it foster institutions capable of safeguarding democratic integrity.

For nearly two decades, the country experienced a tenuous coexistence between former belligerents and notable economic growth. However, the election of a more centralizing and exclusionary leadership in 2009 marked a turning point. Electoral reforms that consolidated FRELIMO's control over electoral institutions, coupled with increasingly blatant manipulation of results, marginalized the opposition and reignited armed conflict. The dominance of FRELIMO within bodies such as the National Electoral Commission and the judiciary enabled the institutionalization of fraud and curtailed meaningful political pluralism.

Although the 2019 peace agreement opened a new chapter, the manipulation of electoral processes has persisted. Far from being anomalies, fraudulent practices have evolved into routine functions of Mozambique's hybrid regime—what Levitsky and Way (2010) define as competitive authoritarianism. Institutions that should safeguard electoral integrity, including electoral commissions, courts, and security forces, have instead been instrumentalised to entrench FRELIMO's dominance. This has contributed to a deepening legitimacy crisis, evident in declining voter turnout and rising public disillusionment with elections as a vehicle for political change.

The findings presented in this article support Zürcher (2011) assertion that, in post-conflict societies, elections imposed without corresponding institutional reform risk becoming mechanisms for elite power-sharing rather than genuine democratization. In Mozambique, elections have served more as instruments of regime continuity than of democratic renewal. If current trends continue, the erosion of electoral credibility may foster conditions for organized political violence, particularly if broad segments of society come to view peaceful contestation as futile. The long-term survival of democracy in Mozambique will depend not merely on holding elections, but on restoring public trust in them as meaningful instruments of governance and change.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

BN: Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Gersovitz and Kriger (2013, pp. 160–161) define civil war as a politically organized, large-scale, sustained, and physically violent conflict that occurs within a country primarily between large/numerically important groups of its inhabitants or citizens. These groups fight for a monopoly on the use of force, challenging the government that controls the state and has a monopoly on force before the outbreak of civil war.

2. ^[1] See Art. 2 et seq. of Law no. 8-2014, of 12 March, which amends and republishes Law no. 5/2013, of 22 February, concerning the functions, composition, organization, competence and operation of the CNE.

3. ^See numbers 1 to 3 of Article 668 of the Mozambique Civil Procedure Code.

References

Afro Barometer (2017). A No-Confidence Vote? Mozambicans Still Vote, But Faith in Democracy Is Slipping, Dispatch No. 139. Available online at: https://afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/migrated/files/publications/Dispatches/ab_r6_dispatchno139_elections_and_democracy_in_mozambique.pdf (Accessed June 18, 2024).

AIM (2019). Mozambique Elections: Constitutional Council dismisses 95 percent of electoral disputes. 7 November. Available online at: https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-elections-constitutional-council-dismisses-95-percent-of-electoral-disputes-aim-269978/ (Accessed June 5, 2025).

Al Jazeera (2014). Mozambique rivals sign peace deal. 5 September. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2014/9/5/mozambique-rivals-sign-peace-deal (Accessed June 5, 2025).

Al Jazeera (2020). Four Mozambique policemen jailed for poll observer's murder. 18 June. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/6/18/four-mozambique-policemen-jailed-for-poll-observers-murder (Accessed June 5, 2025).

Associated Press (2024). Mozambique rocked by the killings of 2 prominent opposition figures soon after disputed election. 19 October. Available online at: https://apnews.com/article/cf07e1a8d232b1266a16c5136d4b06e2 (Accessed June 5, 2025).

Azevedo-Harman, E. (2015). Patching things up in Mozambique. J. Democr. 26, 139–150. doi: 10.1353/jod.2015.0036

Barnés, A. (1998). Compromise and Trust-Building After Civil War: The Elections Administration in Mozambique (1994). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, Innovations for Successful Societies.

Bearak, M. (2024). Mozambique opposition figures killed in protests over disputed election. The Guardian, 19 October. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/oct/19/mozambique-opposition-figures-killed-protest-disputed-election-podemos (Accessed January 30, 2025).

Birch, S. (2011). Electoral Malpractice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199606160.001.0001

Bratton, M., and van de Walle, N. (1997). Democratic Experiments In Africa: Regime Transitions In Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139174657