- Politics and International Studies, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom

This paper engages Hamid's democratic minimalism which proposes democracy via ballot form is not only necessary but sufficient for democracy to flourish. Hamid proposes a state sustaining democratic norms such as voting, free elections, and protection of civil society enlarging the ideological playing field creating different types of democratic states. However, this paper argues this argument fails to protect democracy. By narrowing the scope for procedural democracy to protect itself Hamid opens the door for authoritarianism to emerge democratically. The paper demonstrates this both theoretically and practically via a case study of Hungary. Focusing on the emergence of electoral authoritarianism and polarization, the paper argues procedural democracy cannot reliably retain its shape in a minimalist setting. Through a theoretical realist lens the paper highlights the limits of minimalism arguing democracy requires a thicker relationship to value via deliberation in order for a sustainable arrangement of democracy to emerge. The conclusion of the paper is that minimalism is too thin to sustain democracy creating the conditions for its ultimate demise as shown in the case study of Hungary.

Introduction

Democratic minimalism, as envisaged by Hamid, believes that democracy is the best solution to political problems. This article challenges his claim through two key arguments. First, the article argues that ballot democracy is insufficient to secure itself without sufficient normative guardrails amongst the populace. Second, using a lens of feasibility, the article argues that without active deliberative mechanisms, ballot democracy cannot protect itself from backsliding and the emergence of electoral authoritarianism. The scope of the article focuses on analyzing the feasibility of ballot democracy in a minimalist setting. Ultimately, the article argues that democratic minimalism cannot reliably sustain itself.

Beginning from a definitional stance, the article highlights that there are differing definitions of democratic minimalism. Focusing on two key distinctions, Schumpeter (2013) and Hamid (2022), the article uses the more expansive definition of minimalism given by Hamid. Schumpeter (2013) argues that the citizenry must be limited in its input to democracies, while Hamid (2023) proposes that the ballot becomes an expansive measure that engages wider ideological disagreement. Following the definition of democratic minimalism, the article articulates a conception of consolidated democracy as emphasized by Dahl (2020) and Galperin (2024), including effective participation, voting equality, and inclusion of all non-incarcerated adults, which even procedural democracies must recognize. This is the definition of sustainable democracy, which the article uses as a baseline to argue that we can not only identify democratically sustainable regimes but also highlight threats emerging via the use of mere procedural democracy.

To outline this claim, the article focuses on the mimicking of democratic traits by actors using the ballot to achieve electoral success, highlighting the disconnect between democratic methods and the achievement of sustainable democratic systems. The article argues that the democratic minimalism advocated by Hamid (2022) fails to sustain democratic systems, as it opens the door to their deconsolidation, given that ballots represent an insufficient method of expressing democratic values. The article achieves this by arguing that democracy requires not just a ballot but a normative component expressed via active and regular deliberation amongst the citizenry. Although institutions may provide some protection against anti-democratic actors, the article uses the examples of the United States and Hungary, highlighting the limitations of institutional guardrails to sustain democracy as previously defined. Therefore, stronger normative values than institutional support must be found for democracy to be protected as defined in the article.

Using an illustrative case study method, the article adopts philosophical feasibility. Adopting this method not only provides a greater illustration of the specific problems minimalism faces when put into practice. Using the case study of Hungary, the article presents the argument that democratic minimalism fails to provide sufficient protection for democracy to prosper. Despite significant institutionalization achieved following the collapse of the Soviet Union, this did not stop Orban from turning Hungary into a hybrid regime. By focusing on institutional consolidation, the underlying problems of Hungary, such as economic dislocation, were ignored, allowing undemocratic actors to take office. Ballot democracy and institutionalization thus provided limited protection for the form of democracy outlined in this article.

This conclusion is found via two key observations. First, acknowledging democracy is not merely an institutional procedure but a culture that must be practiced. Democracy, therefore, requires certain norms for it to sustain itself. Whereas Hamid's conception of minimalism acknowledges this, the article argues he does not go far enough in sealing off experiments that potentially undermine democracy. Second, the article explores the danger of inviting the “undemocratic fox” into the “democratic henhouse” via the form of democratic minimalism Hamid uses.

This article makes a theoretical contribution to the literature responding to Hamid (2022) work. Responses to Hamid's work from scholars such as Sadr (2024) focus on pluralism or the case of economic freedom by Murtazashvili (2024). However, neither of these contributions focuses on philosophical feasibility or political realism. There have also been responses, such as Freer and Mahmood (2024), which focus on the Middle East as opposed to central Europe, such as this article, which focuses on Hungary. The article, therefore, makes a new contribution to critiquing Hamid (2022) beliefs about the strengths of democratic minimalism.

Additionally, the article makes additional contributions to the wider literature on democratic minimalism. By critiquing the notion of feasibility, the article questions the notion of legitimacy found in voting alone as discussed by Bidner et al. (2014). The article builds on work such as Petit's (2018), which identifies the limits of procedural voting as a guarantor of any ideology in the sense of greater limits to proceduralism. Nevertheless, the article moves further in identifying deficits in proceduralism than Pettit (2017) by analyzing minimalism's counterproductive essence. Additionally, the article moves beyond Przeworski (2024) or James (2024), who question what democracy is and the material requirements for democracy to function effectively. Instead of seeking an alternative conception of democracy, the article focuses on the limits of minimalism and the need for greater deliberation via a realist lens.

Although research such as Alnemr et al. (2024) engages with practical work on town halls, this does not offer a theoretical framework for critiquing democratic minimalism, nor does it engage with the case study of Hungary. The article also contributes to the literature on Hungary's democratic backsliding, providing new reasoning based on Halmai (2024) article by focusing on a deeper commitment to democratic values at the citizen level than voting alone. Bogaards (2018) and Buzogány (2020) focus on definitions of democracy and institutionalization, but this article contributes to the wider literature on democratic decline. Using Hungary as a case study brings not only a fresh understanding of democratic minimalism and its limits but also new potential ways of analyzing democratic decline in Hungary.

Conceptualizing democratic minimalism

Despite differing descriptions, democratic minimalism has some consistent properties throughout alternative accounts. There are two consistent features of democratic minimalism that appear in every account: the focus on competitive elections deciding rulership and the legitimacy granted to rulers via electoral victory. Rather than seeking legitimacy via the “correct” ideology, bloodline, or competence, minimalists focus on elections as the legitimating factor for the right to rule (Bidner et al., 2014).

Voting acts as a quantitative method of authorization, granting legitimacy to coercive actions undertaken by the state (Dryzek, 2004; Körösényi, 2009). Acquiring not merely a descriptive but a normative element, minimalists such as Przeworski (1999) find elections not as a route to rationality, better decision-making, or ideological cohesiveness but primarily as a path toward peaceful transitions of power (Przeworski, 1999). Although democratic minimalism does not guarantee particular background ideology steering the democratic collective toward a certain pathway or decisions, it makes the claim that democratic proceduralism is not only sufficient but necessary for peaceful transitions of power (Dufek and Holzer, 2013). Therefore, minimalism produces a specific type of democratic ideal founded within the procedural recognition of the people's will rather than focusing on specific institutional or societal values.

Of course, one must assume that this argument against ideological agreement does not extend to the principle of democratic legitimacy itself; otherwise, it would collapse in and of itself. As Bidner et al. (2014) have argued, it is possible for mutual agreement to occur over the legitimacy of voting even if wider ideological disagreements are maintained with political parties. Nevertheless, minimalism does not necessarily require active engagement from citizens in democracy, leaving minimalism open to only ballot participation. Minimalism, being grounded in the will of the citizenry, does not necessarily foster strong civic engagement or reinforce the significance of the ballot.

“Thus, a minimalist democracy as we characterize it can only exist if democratic rules are self-enforcing in the sense of those with the capacity to use violence for political ends choosing not to do so, which we will show they can be.” (Bidner et al., 2014, p. 4)

Minimalists such as Schumpeter (2013) doubt that the average citizen can make a significant difference and that elections by themselves cannot produce unity. This theory of democracy remains elitist, portraying the citizenry as an uninterested, uninformed, and apathetic mass who can only choose from a small pool of representatives (Dryzek, 2004; Schumpeter, 2013). Democracy, for Schumpeter (2013), on its own cannot guide a path toward agreement on core principles, opening the space for representatives to manage the role of ideology and policy once elected (Dryzek, 2004; Pettit, 2017).

According to this vision of democratic minimalism, democracy is far from a free-for-all. The word “minimalism” in Schumpeter narrows the space for citizen participation in politics, leaving political elites to govern. Minimalism, in this sense, does not enlarge democracy or the role of the citizen. Instead, it merely advocates for elections as a tool of governmental legitimation, which can elect and remove representatives peacefully. However, we would be mistaken to believe that this is the only conception of democratic minimalism that is available to us.

As opposed to Schumpeter, there are minimalists who articulate a more inclusive democratic vision, arguing against political norms excluding illiberal policy options. In his book The Problem of Democracy, Shadi Hamid notes that democracy has become “increasingly ill-defined” (Hamid, 2022, p. 44) and rails against the ideologisation of democracy, seeking instead a reinvigoration of democracy. Focusing on the Middle East, the potential rise of Islamist parties via democracy and the US's unwillingness to tolerate different forms of democracy, preferring secular authoritarianism, Hamid's democratic minimalism arrives from the opposite perspective than Schumpeter (Hamid, 2023).

“At their core, democracies offer one essential advantage: they allow for the peaceful alternation of power and the regulation of existential conflict.” (Hamid, 2022, p. 44)

Democratic minimalism in this conception fights the liberal-democratic notion of protected rights outside the boundary of participation in elections and civic society. By ringfencing increasingly large sections of politics as outside the “democratic domain,” the value of democracy wilts in favor of an ideological perception of what constitutes “good outcomes.” As a result, democracy becomes a mere instrumental good rather than a force in and of itself for making political choices. Hamid's claim goes further than merely suggesting that ideological notions mute the power of democracy, but that they actually contribute to a rise of distrust in democracy (Hamid, 2022).

“Counterintuitively, thickening the democratic idea—making it more substantive than procedural—had the effect of diluting the force of democracy, or at least democracy without adjectives.” (Hamid, 2022, p. 49)

Thus, according to Hamid, the sole focus of democratic minimalism is securing the legitimacy of governance. This is especially true in societies ridden with political conflicts, as common ends can rarely, if ever, be found. Far from seeking unity and agreement, democratic minimalism calls for us to embrace our differences and fight it out. It is ultimately a quest of experimentation, difference, and recognizing procedural rules fundamental for democracy to exist. Therefore, we arrive at the somewhat paradoxical notion of finding stability and the peaceful transfer of government while actively embracing our substantive political differences.

“For the opponents of any given government, democracy offers predictability, since losers of elections have the chance to fight another day, as long as they are willing to fight peacefully” (Hamid, 2022, p. 54)

The conception of democratic minimalism that this article challenges is that of Shadi Hamid's more expansive vision of democracy. Hamid contests not only that democratic minimalism is a normatively good idea, i.e., minimalism is the correct thing to do, but he also asserts it is helpful for democracies in allowing our grievances to come to the fore. Hamid's commitment to procedural democracy clashes with his defense of democratic minimalism, as his minimalism opens the door to political movements which, over time, challenge the liberal premises of Hamid's project. In short, democratic minimalism cannot contain the potential results it may inadvertently produce.

Challenges to democratic minimalism in the form of electoral authoritarianism and excessive polarization

This section builds on the previous section, which defines the type of democratic minimalism the article engages with. The article engages in this section with threats to democratic minimalism emerging from electoral authoritarianism. In order to establish what a threat is, the article first needs to establish what it means to be a democracy, i.e., defining minimal features of democracy by which the article can measure declines in democracy. This opens the door to discuss “backsliding,” an effect where we see the features of democracy not only being challenged but also beginning to come under threat. Second, the article shall then define and discuss threats to such a conception of democracy via electoral authoritarianism and excessive polarization, as shall be demonstrated; these are not simply elite-led challenges to procedural democracy but also stem from the ground up. Democratic minimalism, which is far from revitalizing and protecting democracy as envisioned by Hamid, risks becoming too open, allowing undemocratic tendencies to take root in the political sphere and threatening procedural democracy.

Although democracy arrives in various constitutional and institutional guises defying a singular conception, it requires the fundamental features of free voting, effective participation, and inclusion of all non-incarcerated adults if it is to be considered a true democracy, even in a procedural sense (Kendall-Taylor and Frantz, 2014; Dahl, 2020; Diamond, 2015; Galperin, 2024). Such a conception of democracy requires a commitment to the rules of the game, establishing a normative as well as a descriptive component, although the normative commitment is narrowly centered (Castoriadis, 1997; Habermas, 2017; Simon, 2018). Thus, actors that threaten such rules should be considered a threat to the viability of procedural democracy, even as procedural democracy paradoxically believes in every individual's equal participation in competitive and fair elections (Saffon and Urbinati, 2013). Even at its most militant, procedural democracy ultimately accepts democratic results even when the result threatens procedural democracy (Estlund, 2009; Kirshner, 2010).

Minimalism, as defined by Hamid (2022), produces a democratic environment that, under the wrong circumstances, tests procedural democracy to its very limits. Far from providing democratic safety, democratic minimalism's expansionist tendencies make procedural democracy vulnerable to parties and politicians who espouse democracy rhetorically but are not true democrats.

When the parameters of competition are set too openly, this not only risks opening the door to those who may undermine the essence of procedural democracy but, in extremis, could devour the system itself. Thus, rather than supporting relativism, even universal ideas must adapt to the specific environments in which they are situated to adequately defend the common good they seek to uphold (Barber, 1988; MacIntyre, 2013; Martínez-Hernández, 2024). Nevertheless, Hamid's minimalism, in such contexts, cannot meet these challenges, as it presents competition as inherently beneficial—thereby, by definition, undermining the sustainability of procedural democracy.

The question, therefore, is what constitutes “democratic backsliding,” i.e., the erosion of procedural democracy and its ability to sustain itself. Can procedural democracy limit and defeat potential backsliding, or is it insufficient in the face of threats to democracy? First, we must define backsliding. Backsliding includes those who win elections legitimately, who later seek to narrow democratic choice, as well as those seeking institutional overthrow via violence or rigging elections (Bermeo, 2016; Knutsen et al., 2024). Backsliding, therefore, does not simply mean an absolute breakdown in electoral politics but the limiting of electoral freedoms and creating an unbalanced system that limits democratic input (Merkel and Lührmann, 2021). This definition of backsliding represents an affinity with the earlier definition of procedural democracy, which the article uses as a baseline for measuring democratic minimalism. Despite some, such as Tilly (2007), arguing democratization is a continuous process, making it difficult to mark genuine backsliding from democracy changing its nature, as discussed earlier, we can decipher backsliding in democratic regimes when procedural democracy's fundamental features are tested (Tilly, 2007; Cianetti et al., 2020).

Backsliding is particularly likely to occur when threats to democratic function are allowed to grow and develop unchecked. Minimalism, as previously defined, grants the potential breeding ground for such threats to emerge and be cultivated by enlarging the field of competition to the ballot alone. As Habermas (2017) argues, proceduralism alone fails to provide a normative foundation for democracy to sustain itself through loyalty to democratic decision-making. However, if we acknowledge, much like Hamid does, that democracy must maintain certain core properties to remain a democracy, we can also acknowledge when democracy comes under threat, is diluted, or, in extreme cases, is destroyed. Democratic backsliding, therefore, becomes a crucial factor when evaluating the viability of democratic minimalism within the framework of procedural democracy.

Having defined democratic backsliding and outlined how it can occur in procedural democracies and the potential for its amplification via democratic minimalism, it is important to define what type of threats occur. One such threat is electoral authoritarianism. As Schedler (2006) and Morse (2012) highlight, electoral authoritarianism ensures elections are held, but strategies occur that limit the fairness of ballot elections by creating unfair conditions such as unequal access to resources, censorship, and usage of lawfare (using the law to target opponents) in which democratic actors compete. Thus, in electoral authoritarianism, democratic features are mimicked even if not actively practiced, limiting the ability of citizens to access procedural democracy (Signé and Korha, 2016; Tomini et al., 2023; Yabanci, 2024). Electoral authoritarianism is a growing phenomenon as candidates refuse to grant losers' consent, creating a democratic paradox of inclusion of actors who are involved in democracy but refuse to abide by its rules. This is true of both winners and losers who seek to challenge and reshape institutions that protect procedural democracy (Cohen et al., 2023). Electoral authoritarianism is not simply an elite activity, as citizens who claim they want democracy can back candidates who do not practice democratic politics. Once the norm of democracy wears away, the threat of authoritarian actors becomes less of a threat and more of an open choice (Chan, 2024).

The growth of threats to procedural democracy does not only occur with the rise of those who would undermine procedural democracy, but also in the growth of attitudes antithetical to procedural democracy. One such attitude is excessive political polarization. Despite Hamid's minimalism embracing polarization as the navigation of significant differences, we can also witness the potential for democratic backsliding occurring via the rise of polarization. Electoral authoritarianism thrives when fear of the other becomes so great that it is felt they should not be granted political space to have the same chance of victory. Polarization, therefore, is not simply the distance of political parties and actors from each other, but the levels of intensity arrived at via the distance. Politics becomes distended with fewer meetings in the middle, disabling compromise and increasing the possibility of political conflict and measures to limit democratic input of the other contributing to a decline in procedural democracy (Hetherington, 2009; Gentzkow, 2016; Casal Bértoa and Rama, 2021; Levin et al., 2021).

When challenges emerge to democratic institutions, such as increased polarization, this not only attacks formal structures but informal practices such as “agreeing to disagree,” which undergird democratic practices necessary for procedural democracy to survive (Somer and McCoy, 2019; Fossati, 2024). Institutions may be able to protect form but not practice, and if citizens no longer respect the right to disagree via polarization, this inherently undercuts the functioning of procedural democracy. Polarization, when driven to its extremities, limits the ability of the demos to practice democracy, seeing the other as an existential threat. Both established democracies and newer democracies suffer from polarization, challenging democratic resilience societally too, where polarization affects not simply our voting habits but also social relations with one another, threatening procedural democracy (McCoy and Somer, 2019, 2022; Merkel and Lührmann, 2021). Minimalism may be more or less stable, dependent upon not only the existing political context, given the differences between states which have established institutions and long-held cultural values recognizing the importance of democratic principles, which can emerge via the rise of polarization (Munck, 2011; Fossati, 2024).

As witnessed in multiple countries, such as Hungary, Poland, and the United States, procedural democracy has come under risk of backsliding via both electoral authoritarianism and polarization. Citizens have rewarded anti-democratic politicians at the ballot box, undermining the future of procedural democracy (Carrión, 2008; Jacob, 2024). Thus, the emergence of electoral authoritarianism can arise out of procedural democracy rather than simply authoritarian systems of rulership (Bozóki and Hegedűs, 2018; Yilmaz and Bashirov, 2018). We can also see this through Republican voters in the United States, who have become more willing to accept candidates' rejections of democratic results, despite initially supporting democracy, as a result of increasing polarization (Levitsky and Way, 2024). It is therefore not simply countries which are “new” to democracy, such as those in Central Europe, but older examples such as the United States, who have seen backsliding occur from “full democracies” to “flawed democracies,” linking both voter attitudes toward the legitimacy of elections as well as elite behavior such as tilting electoral maps to ensure certain outcomes (Mettler et al., 2022; Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2023).

If procedural democracies lack sufficient values to ground them, the growth of authoritarian “democratic” actors can emerge via the ballot box. Hamid's democratic minimalism fails to sufficiently protect procedural democratic functionality by over-enlarging the public sphere and encouraging the utility of high-risk politics. Far from securing procedural democracy, democratic minimalism's reliance upon ballots and a wider arrangement of democracy opens the door to parties and politics that undermine procedural democracy when acted out. This section has highlighted the danger of minimalism inside procedural democratic systems of government. Minimalism grants too wide a grounding for anti-democratic actors to infiltrate democratic systems, undermining procedural democracy. Additionally, Hamid's minimalism enables, perhaps even encourages, the notion of polarized politics inside a procedural system. Nevertheless, when polarization reaches unstable levels, it increases the likelihood of procedural democracy being undermined. As the next section highlights, procedural democracy, if it wishes to sustain itself, requires a normative component that goes beyond the mere ballot.

Is democracy an institutional or a normative reality: a discussion of deliberation

Building on the previous section, this section argues that institutions alone are insufficient to guarantee procedural democracy. Instead, this section highlights the importance of normative values acquired via deliberation if they are to sustain themselves. On the face of it, this presents democratic minimalism as the optimum application of democratic practice. Nevertheless, as this section highlights, democratic minimalism paradoxically undermines normative commitments to democracy by relying upon ballot voting as the measure of democratic input. Instead, this article proposes stronger commitments to democratic thought and practice beyond voting to secure democracy's functioning.

In order to achieve this, the article focuses on the notion of resilience as it pertains to the stability of procedural democracy. As this section argues, resilience is logically insufficient to plan for threats, as resilience cannot be known until tested by anti-democratic politics. Therefore, relying upon resilience to defend democratic minimalism is an insufficient defense of such a conception of democracy. Following this, the section highlights the inability of institutional protections, such as a separation of powers, to protect democratic features. As discussed in previous and future sections, even institutions with numerous separations of powers, such as within the United States or Hungary, have faced democratic backsliding. Following this discussion, the section highlights why deliberation rather than ballot voting represents a stronger commitment to procedurally democratic values by providing a “thicker” commitment to democratic ideals. Ballot voting does not prescribe active deliberation, which provides additional layers of support for democracy to survive threats, either via polarization or electoral authoritarianism.

Resilience as a concept has acquired a multiplicity of definitions from ecology, engineering, and psychology, all using “resilience” in different ways, albeit sharing similar characteristics of handling stressors and maintaining their quality (Helgest et al., 2022; Boese et al., 2023). Just as we can imagine resilience as upholding features when under threat, we can think of backsliding as the opposite, i.e., losing features when a threat emerges. Furthermore, resilience cannot be measured without first determining the strength of the thing it is resisting. It is therefore not useful to discuss institutional design in relation to democratic resilience unless the design has been tested by anti-democratic politics (Boese et al., 2023; Volacu and Aligica, 2023). Therefore, resilience in the context of the article discusses the ability of procedural democracy to sustain itself within a democratically minimalistic system.

Building on this definition, the article argues that institutional design remains insufficient to guarantee procedural democracy. Part of this process requires an examination of the effects of democratic consolidation to study the protections in place for procedural democracy. Democratic consolidation is the process of “shoring up” democracies, ensuring sustainability in the face of threats to their procedural and minimal functions as previously defined. However, the term mimics sectarianism in being over-developed past a singular recognizable definition, acquiring a broad range of meanings from civilian oversight of the military to enforceable electoral practices (O'Donnell, 1996; Schedler, 1998a; Haddad, 2017; Holloway and Manwaring, 2023). In essence, democratic consolidation has become a byword for institutional methods to secure minimal features of procedural democracy in the face of undemocratic threats.

Consolidation in this context thus means producing institutions that protect the structure of procedural democracy. Such questions of consolidation and institutionalization fail to discuss the quality and underlying strength of democracy outside of casting ballots and institutional rules. Thus, there remains some opaqueness when it comes to describing consolidation beyond such measures, limiting its effectiveness as an explanatory tool for securing democracy (Beetham, 1994; Haggard and Kaufman, 1994; Schedler, 1998b; Randall and Svåsand, 2002). Thus, there is a gap where institutions and procedural democracy may be regarded as secure regardless of the potential vulnerabilities present, even when facing significant challenges such as electoral authoritarianism and polarization in a democratically minimalist environment.

Given that politics is not static, using resilience and institutional design as a method of safeguarding procedural democracy remains insufficient in a minimalist environment. All institutions exist in and are molded by their context, and when they stop producing results, they must be deemed to have faced demise in practice if not in form, limiting their structural force in defending procedural democracy (Mazo, 2005; Barber, 2014). We can witness this in the cases of Tunisia, where institutional protections against rogue actors have been insufficient to defend procedural democracy against threats that emerge inside the system itself (Bednar, 2021; Tomini et al., 2023). Thus, trusting institutional rule to protect procedural democracy risks unresolved tensions in democracies precisely because of its reactive nature, creating the conditions for procedural democracy to fail (Boese et al., 2023; Levitsky and Way, 2024).

This article argues that it is not simply the quantity of democracy that matters, but also the quality. Moving beyond mere proceduralism, democracy requires thicker commitments beyond participation via voting if it wishes to survive attempts to deconsolidate it. Ballot democracy does not exist entirely without discussion, but it fails to center other commitments to procedural democracy found via deliberative methodologies. Democracy requires a normative component if it is to survive challenges from non-democratic actors that move beyond mere proceduralism. In some circumstances, the language of democracy can deflect from actors seeking to undermine it if normative commitments to substantial modes of democracy are lacking (Selelo and Mashilo, 2023; Acar et al., 2024). Unlimited mass democracy creates the potential for overload, where the state has to integrate undemocratic actors into the democratic process. Indeed, abstract support for democracy is worth little if such support is unconditional toward actors who are willing to dismantle the systems protecting it (Bonefeld, 2017; Cohen et al., 2023). Therefore, more is not always better when it comes to democracy.

Deliberation ultimately is not merely the process of more democracy. Justification and having to use justifications help produce a stronger moral framework to guide our political decision-making. Despite considerable studies questioning the utility of deliberation, this only maps deliberation in our current framework of governance, limiting its explanatory effect (Thompson, 2008). A stronger normative framework for democracy challenges mere institutionalization of values, which can exist on a “higher plane,” giving protection from potential threats to democracy. Rather than focusing on rights guaranteed by institutions that can be overturned, deliberation focuses on the goals and interests of all participants. Thus, deliberation requires a more substantive engagement with other participants and recognizes a fundamental equality of the citizen, which voting alone does not. It is this thicker engagement that the article argues highlights the limitations of democratic minimalism.

As Petit (2018) and Habermas (2017) note, proceduralism and deliberation fundamentally diverge. Voting is a “thin” exercise in democracy, whereas deliberation is a “thick” exercise of democratic principle. Given that voters do not always punish undemocratic actors as discussed in the previous section, we should not assume democracies can sustain themselves merely at the ballot box, and such a thin tool should be looked upon with skepticism. If democracy, even procedural democracy, is merely seen as an instrumental good instead of an absolute good, this threatens its continuation. Thus, there is a stronger normative commitment than the ballot can provide (Balasco and Carrión, 2019; Frega, 2018, 2019). Normative commitments to democracy require a thicker relationship between the demos and democracy via a set of values outside of ballot democracy (Schedler, 2002). The ballot is merely an expression of will. It does not come with any normative supposition that democracy should remain. As seen in previous and future sections, citizens regularly reward actors who undermine procedural democracy. Thus, ballot democracy can incorporate elements threatening the future of procedural democracy where institutions cannot provide a sufficient safety net against electoral authoritarianism (O'Donnell, 2001; Przeworski, 2007).

Whereas voting is a relatively “thin” method, deliberation is inherently “thicker.” Deliberative methods of democracy utilize reciprocal recognition of the other to make hierarchical decisions. As Ryfe (2005) discusses, deliberation is distinct from procedural democracy in that it grants the public a hand in the decision-making process, apart from merely being consulted as in voting. Creating a more radical democratic practice amongst the populace theoretically, as Habermas (1975) argued, creates a forum for the best argument to prevail as opposed to selective interest, bargaining, and power, with the right to disagree being protected via respectful exchanges (Habermas, 1975; Cohen, 1996; Landemore, 2017). Voting does not entail any such thing, as demonstrated by the rise of electoral authoritarianism and polarization, even if voting is oftentimes accompanied by discussion amongst the electorate and representatives.

Indeed, in modern democratic politics, deliberation has been increasingly limited, with citizen participation lessening in politics. As Guerrero (2024) has argued in Lottocracy, the current political background in many democracies limits true democratic input due to questions of time and money influencing political decision-making at the ballot box. Truly engineering democracy requires a more rigorous practice than voting alone. The decline of citizen participation coincides with the rise of authoritarian populist movements, which paradoxically gain popularity from the support of the general public (Schnaudt et al., 2024). Indeed, studies have shown that precious few have been asked to deliberate, and when asked to do so, participants are keen to do so (Neblo et al., 2010). Deliberation has also been found to have maintained its effect after first being conducted, with an interest in politics maintained and support for greater citizen input found in some participants throughout the policy process (Van der Does and Jacquet, 2023). Typically, those involved in the deliberative process are wary of the professionalization of politics as the curtain of politics and decision-making is pulled back from them (Itten and Mouter, 2022). Deliberation, therefore, can provide a framework for ingratiating stronger democratic values and norms than mere ballot democracy. Without active engagement via deliberation and mere institutional management of politics, citizen functionality within politics is lessened. Deliberation can maximalise functional democratic traits such as inclusion, collective agendas, and decision-making, curating a more active democratic structure than ballot democracy alone grants (Scudder, 2023).

Nevertheless, we may find some limitations to this form of democratic modeling. Deliberative politics has practical limits under our current conditions. Not everyone can discuss every act of politics without grinding decision-making to a halt, requiring some form of decision-maker to take charge without consultation on some questions (Cohen and Fung, 2004; Thompson, 2008). However, deliberation does not need to be invested in each and every decision for it to be valuable. Instead, deliberation is sufficient to help us figure out a route to the common good through complementary listening and engagement with one another in a non-coercive fashion. This does not diminish argument or difference but encases it within the specific practice of deliberation (Mansbridge et al., 2012).

This section has highlighted that for democracy to survive, institutions are insufficient without strong commitments from the citizenry for democratic flourishing. Elections alone are poor indicators of this. As we have seen in numerous examples, the demos can not only accidentally elect those who undermine democratic values but also go on to reward actors with renewed terms. This undermines one of the core pillars of democratic minimalism, which relies upon free and open choices to “play out” the best modes of governing, as the demos can paradoxically limit their future options.

On the face of it, democratic minimalism's advantage can be seen here. By refusing to exclude political actors who are challenging, democracy is opened up, creating a maximalist vision theoretically enabling democratic features to thrive. Nevertheless, if democracy is recognized as a truly normative commitment, then merely voting feels insufficient to practice democracy fully, even if it is necessary procedurally. Voting, after all, is merely a descriptive method of practicing democracy without the underpinning value set to sustain democratic practice in the long run. Democratic minimalism, therefore, should not be constrained inside a voting system alone but should open up possibilities for greater deliberation.

Democracy requires a strong normative commitment from the demos to safeguard its future, which institutions cannot provide alone. Although at first glance, minimalism appears to be useful in safeguarding democracy, as discussed earlier, Hamid's conception is too capacious to retain democracy's stability and function. However, as discussed earlier, institutions alone lack usefulness in retaining democratic features. Rather, the demos should inculcate democratic values via greater deliberation than we currently see. Democracy must be seen as larger than a “vote” but a commitment to a set of values which some actors fall foul of.

Case study method

Opening the door for philosophical realism to emerge, this article interrogates democratic minimalism on both practical and theoretical planes. Interrogating democratic minimalism in this way allows the article to argue that minimalism fails to protect procedural democracy as is claimed. The case study method allows the article not only to contribute to the theoretical literature but also to the empirical literature. In this article, the theoretical engages with the empirical, granting each a new lens of the other.

The case study method is especially useful when investigating a phenomenon within its real-life context, allowing for the creation of a new hypothesis by testing outcomes (Yin, 1992). As Geertz (1973) argues, the case study allows a rich understanding of a particular case and context to emerge. In doing so, the case study approach grants greater explanatory power than a quantitative approach when addressing theoretical questions. Furthermore, given the word count restrictions, the use of a singular study also grants the article additional richness and depth compared to a comparative analysis of multiple cases.

The design and implementation of a case study remain contested, as argued by Yazan (2015), but the article follows Yin's (2013) approach in examining the case within its specific context and using the case study as a descriptive tool for the study. As Flyvbjerg (2006) argues, the case study method grants greater analytical scope, which need not be generalisable for it to grant value. The use of a singular case study is a particular finding not necessarily replicable outside of its given context. This does not exclude analytical generalization but does require caution when applying its findings more widely (Halkier, 2011; Yin, 2013). Repetition does not need to be found for generalisable claims to be made, given the use of the case study, but situational realities need to be taken into account. Doing so does not reduce the question of agency but leads to a stronger description where context creates the conditions for certain outcomes to become more likely (Yin, 1994; Delmar, 2010; Byrne, 2013; Woolcock, 2013).

Moving beyond the technical, integrating theory and practice creates a dual criticality imposed upon the study, both theoretically and practically (Wolin, 1969). The case study, therefore, not only acts as a descriptive tool for the study but also as a heuristic tool for the reader. A practical method that is used for philosophical realism is that of the case study. Case studies remain a popular method even amongst disciplines which traditionally do not venture into empirical studies, such as political theory, because of their utility and their ability to be interrogated in either a qualitative or quantitative fashion (Gerring, 2004). Case studies, therefore, provide theory greater explanatory power, which theory alone struggles to possess, which is why this article takes the approach of Carens (2004), who argues

“Theories aim to generalise and that inevitably entails abstraction from particularity, but sometimes theories are presented at such a level of generality and abstraction that it is hard to tell what it really means.” (Carens, 2004, p. 118)

Using a case study approach grants explicit illustration and practicality, addressing the feasibility of the theory of democratic minimalism. It is only through the application of a case study that the article can fully explore the possibilities emerging within Hamid's vision of democratic minimalism. Furthermore, using an illustrative approach by clarifying the function of the theory makes both the reader and the author conscious of the issues that need to be addressed in the theory through the practical. As argued by Thompson and Modood (2019)

“It is through the exploration and evaluation of multiple contexts that general principles are devised, revised, and refined” (Thompson and Modood, 2019, p. 340)

Feasibility has traditionally been used in normative political theory, as stated by Valentini (2012) and Freeden (2012). However, it can also be used in descriptive political theory by assessing the possibilities and reliability of a theory's description of the world. Exemplified in Rawls' (2001) work, which cites feasibility as “probing the limits of practicable political possibility” (Rawls, 2001, p. 4–5) and in Gilabert and Lawford-Smith (2012), who claim, “A state of affairs is infeasible if it ignores the momentum or inevitability of certain events” (Gilabert and Lawford-Smith, 2012, p. 811). Drawing on feasibility, the article focuses on practical limits on democratic minimalism's function in practice.

An illustrative case study approach simultaneously achieves greater depth and increased clarity of theory in comparison to a purely hypothetical approach (Reeves, 2018). This is a form of realist theorizing that enables practical and functional thinking alongside theoretical thinking (Rossi and Sleat, 2014; Jubb and Rossi, 2014). This aids the role of the theorist, which is not simply to understand the domain of politics and agency but also to contribute to improving the actions of the agents involved (Raekstad, 2015). By engaging with theory via a realist lens, the article is able to judge feasibility, granting greater depth to theorizing.

The dimensions of the research are the existence of a democratic system before an undemocratic regime came to power, i.e., voters freely elected an undemocratic regime and then decided to retain it. By this framework, the article substantiates the claim that procedural democracy alone is insufficient to sustain itself in some circumstances. The methodology of the article sits within philosophical realism, using a case study highlighting the lack of feasibility of democratic minimalism within consolidating democracies. Choosing Hungary as the case study complements the methodology of feasibility and political realism by locating the potential for democratic minimalism to undermine the fundamental features of democracy. The article finds minimalism's deficiencies via engagement with the case study, arguing that the idea, when put into practice, cannot sustain itself, making minimalism within the confines of emerging democracies ultimately inconsistent with democratic practice.

The Hungary case study

As the case study highlights, when a procedural democracy becomes too capacious, including actors who seek to contest the procedural democratic regime, this creates danger for the sustainability of even minimalistic democracy. Not only has this case study taken minimalism to its very limits, but it also presents a picture of a democracy that emerged in the third wave, which was thought to have been “consolidated.” Thus, this case study teaches us that even so-called “consolidated” democracies run the risk of deconsolidation when facing challenges to their principles.

The context in Hungary is far from unique, but the significance of the backsliding is distinctive in the region. Democratic backsliding has occurred in multiple countries, such as Poland and Romania, without regime change occurring, making Hungary simultaneously special and representative (Bernhard, 2021; Helms, 2023). The rise of Fidesz and Orban occurred in conditions replicated across the continent. As Krekó and Enyedi (2018) argue, the factors leading to democratic backsliding are not necessarily specific to Hungary. The case study of Hungary used in the article brings to life the theoretical concerns described earlier. Hungary as a case study fits the parameters of the article by representing significant challenges in institutionalization, democratic sustainability, and the role of consolidated vs consolidating democracies (Pappas, 2014; Buzogány, 2020; Mészáros, 2020). Therefore, Hungary is both relevant and significant to my article's argument for testing the feasibility of minimalistic democracy.

Hungary still conducts elections, albeit under profoundly unfair conditions, yet Orban and Fidesz have retained genuine popularity amongst its citizens. Additionally, the parameter of a constitution guaranteeing free and fair conditions was also accounted for, ensuring a replication of Hamid's standards for democratic minimalism. The Hungary case study highlights how anti-democratic actors can profit from electoral politics and continue to do so during their rulership. Anti-democratic actors can not only change the system institutionally, degrading its democratic credentials, but they can also retain or increase their popularity, cementing their power despite citizens participating in unfair elections. Thus, the paradox of popularity and a lack of democracy arrives at the heart of the case study and argument for the article.

Fragmented opposition, economic failures by the previous regime, and cultural fights over migration built the platform for Fidesz to take power via the ballot box. The swift transition to a market democracy was not unique with Poland and the Czech Republic also aligning themselves with the Washington Consensus model of development. The subsequent financial catastrophe following 2008 led to the collapse of support amongst both the liberal and socialist bases (Scheppele, 2022; Bod, 2024). The rise of Orban's Fidesz can be grounded in the perceived economic failure of previous regimes, which was replicated across countries experiencing significant economic distress post-2008 (Armingeon and Guthmann, 2014; Cordero and Simón, 2016).

The rise of Orban as a populist leader is not unique either, and neither is the fact that Fidesz earned a disproportionate seat share compared to its vote share (Bozóki, 2015; Mudde, 2021). These are all events that are witnessed across multiple countries in the region and beyond. Nevertheless, the path Fidesz took differed from other regimes that gained power post-2008, which were part of the populist right-wing surge. Orban, far from violating the constitution and laws of the state, simply remade them via the fundamental law, reshaping the constitutional order (Levitsky and Way, 2010; Bozóki and Benedek, 2024). In doing so, Orban did not merely become an authoritarian but changed the very nature of the political system in a unique way, making Hungary's regime difficult to categorize (Bozóki and Hegedűs, 2018; Ágh, 2022). The Hungary case study is significant due to the particular methods of institutional change created through “Frakenstate” methods, highlighting how agents can undermine procedural democracy when they arrive via democratic elections (Drinóczi and Bień-Kacała, 2019; Donáth, 2020; Fleck et al., 2022).

Once in power, Fidesz's use of the media to create an uneven playing field, undermining procedural democracy, is also not unheard of, with regimes such as Chavez in Venezuela providing a coherent example of this. However, the extent of re-engineering the constitution and political system to create a hybrid regime makes it unique in Eastern and Central Europe. As Scheppele (2022) argues, when in office, Orban did not expand a loyal voter base but relied upon a mixture of electoral bribery, intimidation of some government workers, and theft of issues from his rivals, combining legitimate democratic tactics with authoritarian ones.

This is not to say Orban has not retained popularity, as he has used issues such as immigration and the war in Ukraine to cement his electoral position; this is not unique. The notion of crisis via the issue of migration is a common tactic with radical right-wing populists such as Orban and Trump (Li et al., 2022; Szalai, 2024). The personalistic voice of Orban's regime is crucial to its success, as it is with other populists such as Trump, who seek to reinvent legitimacy away from the system of government to a political leader (Madlovics and Magyar, 2021; Sonnevend, 2024). We therefore see Orban's regime as not merely “elite-led” but as finding support from the demos.

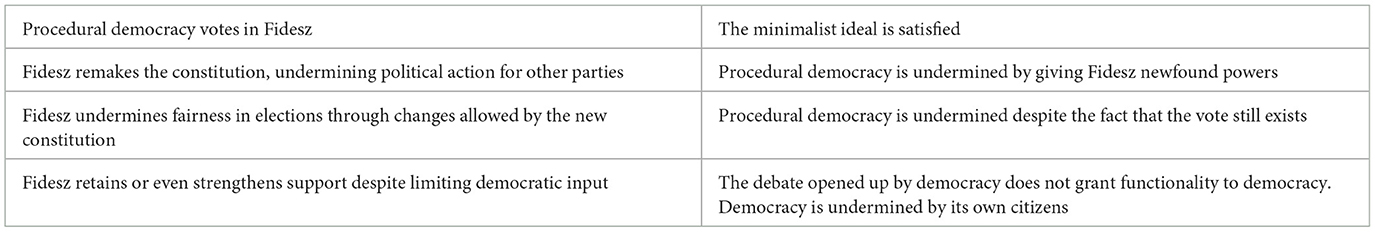

As discussed earlier, consolidation is not a static measure, and backsliding can occur even in democracies that have been considered “consolidated,” i.e., democracies which have created institutions governing procedural democratic arrangements. Hungary, therefore, represents a consolidated case of procedural democracy, as it corresponds to previous definitions. It also corresponds to the minimalistic definitions given by Hamid, given the wide variety of political actors allowed to participate. The rise of Fidesz and its alteration of the state highlight the limitations of democratic minimalism in sustaining itself, as marked out in the Table 1.

As Bogaards (2018) highlights, there remains no scholarly consensus on how to categorize the Orban regime beyond the fact that it is no longer a procedural democracy by its own definition. However, there are reasons for us to no longer label Hungary as a democracy. Frequent scores on democracy tables such as Freedom House have found Hungary's decline from a free democracy to only “partially free,” noting not only constitutional changes limiting not only democratic power but also the lack of rule of law and growing abuse of power, with freedom of expression declining. In seven out of eight categories for the maintenance of democracy, Hungary was found to be defective, and in three out of eight, it was found to be “highly defective” (Bogaards, 2018).

This highlights the obvious potential for democratic degradation occurring inside liberal democracies. Pursuing ideological experiments with policy, i.e., making liberalism smaller and democracy larger, is difficult to calculate in terms of risk. After all, Hungary, like other central European countries following the collapse of communism, produced not only free and relatively fair elections but also institutions providing the rule of law and checks and balances, making Hungary a “consolidated democracy.” Nevertheless, when faced with considerable pressure, such checks and balances found in Hungary's institutions were insufficient to prevent a regime that was determined to undo them as a result of a citizen's legitimate vote (Bugarič, 2015; Kornai, 2015; Herman, 2016; Buzogány, 2020).

Although the state had guaranteed the processes of democracy, it was much less successful at managing the development of its newfound capitalist economy, creating significant differences between economic groups. The result was discontent at economic change perceived to be happening “above” the demos, with only select “elite” groups benefitting from increased marketisation, in part due to a legacy of the former communist regime (Bugarič, 2015; Ágh, 2016). This absence of consent in the economic sphere opened the door for Orban to tell a story that made sense to ordinary Hungarians. Orban's success cannot merely be laid at the door of manipulation but at a genuine ability to recruit support like any other democratic politician (Csillag and Szelényi, 2015). At this point, Orban and Fidesz fit within the strictures of a democratically minimalist framework. They offered an alternative form of democratic arrangement prioritizing the “D” of democracy. Orban's coalition in 2010 won him 68% of the seats in Parliament, representing a significant democratic victory, aligning initially with Hamid's notion of minimalism (Kornai, 2015).

However, the Hungarian case exposes the inherent dangers when procedural democracy entertains anti-democratic actors via voting. This is reflected in the development of “uncivil society,” where institutions such as universities, NGOs, and xenophobia against migrants are narrowing the space for deliberation and the reimagination of institutions, undermining the rule of law, freedom of expression, and free and relatively fair elections (Bustikova and Guasti, 2017). This type of limit genuinely affects democratic involvement itself as a result of a future lack of deliberation (Buzogány, 2020; Sata and Karolewski, 2022).

The rise of Fidesz culminated in a constitutional supermajority in 2010, leaving little room for institutional checks on their power. The changing nature of the state can be observed in the shift in the speed of legislation. Between 2010 and 2014, 88% of bills were voted on within a week of being introduced, and in 13 cases, bills were introduced and voted on within a single day. The new constitution was likewise drafted amongst a small group of leaders within Fidesz, going through a similar process despite widespread protests against it (Kornai, 2015). These structural reforms enabled Fidesz to continue winning in elections, given their domination of the media landscape and limited budgets for opposition parties. Orban also gerrymandered electoral districts following their initial victory, which helped disable electoral competition (Kákai and Pálné Kovács, 2021; Sata and Karolewski, 2022). Orban used an original mandate to govern and change the character of the state, making it significantly more difficult to remove him and his party in the future.

Victor Orban, the leader of Fidesz, has changed the constitutional court's role via the use of the Fundamental Law, suspending review powers and limiting access to the court via those leading institutions or a quarter of MPs demanding a review of legislative acts. These changes have fundamentally altered Hungary from what was a procedurally democratic state with a competitive party system and safeguards such as a constitutional court into a personalized system with Fidesz representing the people's will that has significant barriers to challenge (Scheppele, 2014; Pappas, 2014; Varju and Chronowsk, 2015; Vincze, 2014; Buzogány, 2017; Szente and Gárdos-Orosz, 2018). One election provided the plaform for significant changes to the state. The speed of the changes provided little chance for pushback creating exclusionary notions of whom belongs and who does not. This progression highlights a central limitation of democratic minimalism. Hamid's notion of democracy fails to take into account the likelihood of undemocratic parties occupying institutions and undoing democracy by virtue of their democratic mandate. Far from playing out differences in the public realm, Fidesz has used its popularity to undermine democratic practices. Institutional defenses were insufficient to stop a significant breach of procedural democratic norms.

Mészáros (2020) argued that the constitutional changes Orban has made reflect a movement from a legalist state to a Schmittian decisionist-style executive state, limiting democratic input. This “Frankenstate” has stripped away attempts to limit executive power and instead prioritized concrete action by the state that is now difficult to restrain. This can be witnessed via the example of legislation on the “emergency caused by immigration” in 2015, suggesting a leak between emergency power, the regular constitutional order, and democratic sustainability (Mészáros, 2020). Stripping away constraints has laid bare the notion of a distinction between the regime and the state as the regime slowly becomes an integral part of the functioning of the state, affecting the notion of democratic minimalism.

The tendency to centralize by Fidesz moves beyond essentially fusing the executive and legislature together but moves into the roots of the state. Although institutions may be able to guide actors during times of political stability, it is during moments of radical change that the institution is being shaped rather than doing the shaping. Indeed, such a shift occurred in Hungary even when many regulations on finance and party organization were confined to the constitution, requiring a 2/3rds majority to overturn (Ilonszki and Várnagy, 2014). Fidesz officials have limited media freedom and used propaganda in an attempt to buttress their rule, providing a semblance of legitimacy outside of the 2010 election result (Bajomi-Lázár, 2013).

The case study of Hungary highlights the dangers of democracies becoming too capacious in whom they include. Hungary, even as a young democracy, was a consolidated one with institutions creating a separation of powers and genuine democratic features. It was considered one of the most promising post-communist examples of liberal democracy. Nevertheless, Hungary has shown the limitations of democratic minimalism in a procedural sense. Fidesz and its leader, Viktor Orbán, used their electoral victory to upturn institutions. Not only have they fused executive and parliamentary branches of government for all intents and purposes, but Fidesz has also been successful in limiting democratic input by gerrymandering electoral districts, defunding competitors, and controlling significant portions of the media.

The net result of these changes is the erosion of democracy in Hungary. Although there is no scholarly consensus on precisely how to label Hungary's democratic credentials, all agree that there has been some negation of democratic tendencies. The case study highlights that even though democratic minimalism is internally coherent theoretically, it does not put a realistic case forward on how to sustain democratic arrangements. Democracy in a minimalistic environment promotes the possibility of democracy being upturned once a single election has been held.

The case study of Hungary contributes to highlighting the limits of democratic minimalism. As we have seen with the Hungarian examples, illiberal democracy is an oxymoronic term, as given enough space, such regimes disintegrate into an environment hostile to the flourishing of democracy. From a feasibility and realist perspective, democratic minimalism fails to protect minimal requirements for procedural democracy to flourish. The institutional mechanisms required to protect democracy come under increasing pressure and scrutiny, leading to an unsustainable minimalist application of democracy once normative commitments drain away.

Hungary's new democracy was still relatively well-consolidated. Nevertheless, Fidesz found a way to overcome such consolidation and use its institutions against themselves. By narrowing the ability of institutions to check the regime and creating an “uncivil society,” the lack of deliberation created by Fidesz ensured ballots lost their procedural value. The undermining of democracy in Hungary highlights the limitations of democratic minimalism.

Conclusion

The article has focused on Shadi Hamid's theory of democratic minimalism via a philosophical realist lens, focusing on questions of feasibility. The article does not challenge the internal logic of Hamid's argument, as his principles and reasoning are internally consistent, nor does it attack his ideas from a normative standpoint. Rather, the article focuses on the durability of a democratically minimalist project once acted out. Using the case study of Hungary, the article critiques democratic minimalism from a philosophical feasibility point of view.

My article responds to Hamid (2022) work, adding to the theoretical literature by critiquing Hamid from a feasibility perspective, unlike Sadr (2024) and Freer and Mahmood (2024), who focus on pluralism and the Middle East. My article brings forward a discussion of Central Europe to unpack Hamid's theories in an alternative geographic space via a new case study and a fresh theoretical framework. My article thus makes two significant new contributions to discussions on democratic minimalism. The article contends that Hamid's democratic minimalism is too capacious to sustain itself. Voting, while a mechanism for legitimacy, is insufficient to sustain democratic practice in the long run. Despite Hamid's attempts to safeguard democracy by creating a procedurally democratic state to retain its structural features, minimalism's inclusion of potentially rogue political actors leads to a lack of feasibility. Voters, even voters in consolidated democracies, can not only vote for actors who degrade procedural democracy in elections post hoc but can also reward them in future elections, undermining the bare minimum for procedural democracy to sustain itself. Thus, mere voting is insufficient to safeguard democracy.

As the article has shown, democratic resilience entails the ability to withstand certain stressors. Some states arguably possess the institutional capacity to maintain democracy even while operating minimalistic practices. However, due to the very nature of institutional strength, it cannot be known until it is sufficiently well-tested. Thus, creating an overly capacious democratic environment begets potential dangers for democracy to maintain itself. Ultimately, democratic minimalism is, at best, a gamble with the very values it seeks to defend and, at worst, an active gateway to undermining procedural democracy. Democratic minimalism in the form of Hamid's expansion of democratic toleration leads down the road to a political arrangement that it ultimately could not support. Minimalism, therefore, has the potential to create a political system that is undemocratic and one that minimalism would not envision.

The case study of Hungary places a practical mapping of the limits of democratic minimalism and the lack of protection institutions alone can give. Hungary, despite significant institutionalization and previous elections under Orban and Fidesz, suffered democratic regression. Despite a lack of consensus on what precisely to label Hungary's democratic regression, scholars do agree there has been one. Fidesz has not only reconstituted the government, but they have also limited the ability to challenge their rule via gerrymandering districts, defunding opposition groups, creating an “uncivil society,” and using the media to their advantage.

The article not only adds to the literature but also opens the door to additional areas of research to contribute to the literature. Future articles will build on this effort and discuss the relationship between fear, deliberation, and wider polarization. Additionally, future articles will research alternative case studies with different forms of politics, such as the United States. Finally, future avenues of research can build on this to develop a practical institutional change in order to secure democracy beyond minimalistic conceptions.

Author contributions

SM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acar, B., Bagci, S. C., and Verkuyten, M. (2024). Toleration, discrimination, or acceptance? How majorities interpret and legitimize minority toleration depends on outgroup threat. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 63, 1053–1072. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12715

Ágh, A. (2016). The decline of democracy in East-Central Europe: Hungary as the worst-case scenario. Probl. Post-Communism 63, 277–287. doi: 10.1080/10758216.2015.1113383

Ágh, A. (2022). The Orbán regime as the “perfect autocracy”: the emergence of the “zombie democracy” in Hungary. J. Cent. East Eur. Stud. 18, 1–25. doi: 10.2478/pce-2022-0001

Alnemr, N., Ercan, S. A., Vlahos, N., Dryzek, J. S., Leigh, A., Neblo, M., et al. (2024). Advancing deliberative reform in a parliamentary system: prospects for recursive representation. Eur. Political Sci. Rev. 16, 242–259. doi: 10.1017/S1755773923000292

Armingeon, K., and Guthmann, K. (2014). Democracy in crisis? The declining support for national democracy in European countries, 2007–2011. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 53, 423–442. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12046

Bajomi-Lázár, P. (2013). The party colonisation of the media: the case of Hungary. East Eur. Politics Soc. 27, 69–89. doi: 10.1177/0888325412465085

Balasco, L. M., and Carrión, J. F. (2019). Required consultation or provoking confrontation? The use of the referendum in peace agreements. Representation 55, 141–157. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2019.1636852

Barber, B. R. (1988). The Conquest of Politics: Liberal Philosophy in Democratic Times. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780691225227

Barber, S. (2014). Constitutional Failure. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. doi: 10.1353/book35437

Bednar, J. (2021). Polarization, diversity, and democratic robustness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118:e2113843118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2113843118

Beetham, D. (1994). Conditions for democratic consolidation. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 21, 157–172. doi: 10.1080/03056249408704053

Bernhard, M. (2021). Democratic backsliding in Poland and Hungary. Slavic Rev. 80, 585–607. doi: 10.1017/slr.2021.145

Bidner, C., Francois, P., and Trebbi, F. (2014). A Theory of Minimalist Democracy (No. w20552). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. doi: 10.3386/w20552

Bod, P. Á. (2024). Return of activist state in a former transition star: the curious case of Hungary. Post-Communist Econ. 36, 262–279. doi: 10.1080/14631377.2023.2273694

Boese, V. A., Edgell, A. B., Hellmeier, S., Maerz, S. F., and Lindberg, S. I. (2023). “How democracies prevail: democratic resilience as a two-stage process,” in Resilience of Democracy, eds. A. Lührmann, and W. Merkel (London: Routledge), 17–39. doi: 10.4324/9781003363507-2

Bogaards, M. (2018). De-democratization in Hungary: diffusely defective democracy. Democratization 25, 1481–1499. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2018.1485015

Bonefeld, W. (2017). Authoritarian liberalism: from Schmitt via ordoliberalism to the Euro. Crit. Sociol. 43, 747–761. doi: 10.1177/0896920516662695

Bozóki, A. (2015). Broken democracy, predatory state and nationalist populism. Hungarian Patient 247–262. doi: 10.1515/9786155225550-005

Bozóki, A., and Benedek, I. (2024). “Politics in Hungary: two critical junctures,” in Civic and Uncivic Values in Hungary, eds. S. P. Ramet, and L. Kürti (London: Routledge), 17–42. doi: 10.4324/9781003488842-3

Bozóki, A., and Hegedűs, D. (2018). An externally constrained hybrid regime: Hungary in the European Union. Democratization 25, 1173–1189. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2018.1455664

Bugarič, B. (2015). A crisis of constitutional democracy in post-Communist Europe: “lands in-between” democracy and authoritarianism. Int. J. Const. Law 13, 219–245. doi: 10.1093/icon/mov010

Bustikova, L., and Guasti, P. (2017). The illiberal turn or swerve in Central Europe? Politics Gov. 5, 166–176. doi: 10.17645/pag.v5i4.1156

Buzogány, A. (2017). Illiberal democracy in Hungary: authoritarian diffusion or domestic causation? Democratisation 24, 1307–1325. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2017.1328676

Buzogány, A. (2020). “Illiberal democracy in Hungary: authoritarian diffusion or domestic causation?” in Authoritarian Diffusion and Cooperation, eds. A. Bank, and K. Weyland (London: Routledge), 73–91. doi: 10.4324/9780429452123-5

Byrne, D. (2013). Evaluating complex social interventions in a complex world. Evaluation 19, 217–228. doi: 10.1177/1356389013495617

Carens, J. H. (2004). A contextual approach to political theory. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 7, 117–132. doi: 10.1023/B:ETTA.0000032761.25298.23

Carrión, J. F. (2008). “Illiberal democracy and normative democracy: how is democracy defined in the Americas,” in Challenges to Democracy in Latin America and the Caribbean (Vanderbilt), 21.

Casal Bértoa, F., and Rama, J. (2021). Polarization: what do we know and what can we do about it? Front. Polit. Sci. 3:687695. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.687695

Castoriadis, C. (1997). Democracy as procedure and democracy as regime. Constellations 4, 1–18. doi: 10.1111/1467-8675.00032

Chan, K. M. (2024). Autocratization spillover: when electing an authoritarian erodes election trust across borders. Public Opin. Q. 88, 828–842. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfae018

Cianetti, L., Dawson, J., and Hanley, S. (2020). “Rethinking “democratic backsliding” in Central and Eastern Europe–looking beyond Hungary and Poland,” in Rethinking'Democratic Backsliding'in Central and Eastern Europe (London: Routledge), 1–14. doi: 10.4324/9780429264795-1

Cohen, J. (1996). “Procedure and substance in deliberative democracy,” in Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political (Princeton, NJ), 95. doi: 10.1515/9780691234168-006

Cohen, J., and Fung, A. (2004). Radical democracy. Swiss J. Polit. Sci. 10, 23–34. Available online at: https://shs.cairn.info/journal-raisons-politiques-2011-2-page-115?lang=en

Cohen, M. J., Smith, A. E., Moseley, M. W., and Layton, M. L. (2023). Winners' consent? Citizen commitment to democracy when illiberal candidates win elections. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 67, 261–276. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12690

Cordero, G., and Simón, P. (2016). Economic crisis and support for democracy in Europe. West Eur. Polit. 39, 305–325. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1075767

Csillag, T., and Szelényi, I. (2015). Drifting from liberal democracy. Neo-conservative ideology of managed illiberal democratic capitalism in post-communist Europe. Intersections 1, 18–48. doi: 10.17356/ieejsp.v1i1.28

Delmar, C. (2010). “Generalizability” as recognition: reflections on a foundational problem in qualitative research. Qual. Stud. 1, 115–128. doi: 10.7146/qs.v1i2.3828

Diamond, L. (2015). Facing up to the democratic recession. J. Democr. 26, 141–155. doi: 10.1353/jod.2015.0009

Donáth, A. J. (2020). Absolutely corrupted: the rise of an illiberal system and the future of Hungarian democracy. Brown J. World Aff. 27:83.

Drinóczi, T., and Bień-Kacała, A. (2019). Illiberal constitutionalism: the case of Hungary and Poland. Ger. Law J. 20, 1140–1166. doi: 10.1017/glj.2019.83

Dryzek, J. S. (2004). Democratic political theory. Handb. Polit. Theory 1, 143–154. doi: 10.4135/9781848608139.n11

Dufek, P., and Holzer, J. (2013). Democratisation of democracy? On the discontinuity between empirical and normative theories of democracy. Representation 49, 117–134. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2013.816189

Estlund, D. (2009). “Epistemic proceduralism and democratic authority,” in Does Truth Matter? Democracy and Public Space, eds. R. Geenens, and R. Tinnevelt (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 15–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8849-0_2

Fleck, Z., Chronowski, N., and Bard, P. (2022). The Crisis of the Rule of Law, Democracy and Fundamental Rights in Hungary. MTA Law Working Papers 2022/4. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4100081

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual. Inq. 12, 219–245. doi: 10.1177/1077800405284363

Fossati, D. (2024). Illiberal resistance to democratic backsliding: the case of radical political Islam in Indonesia. Democratization 31, 616–637. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2023.2210504

Freeden, M. (2012). Interpretative realism and prescriptive realism. J. Polit. Ideol. 17, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/13569317.2012.651883

Freer, C., and Mahmood, N. (2024). An Islamist disadvantage? Revisiting electoral outcomes for Islamists in the Middle East. Middle East. Stud. 61, 148–160. doi: 10.1080/00263206.2024.2376097

Frega, R. (2018). The social ontology of democracy. J. Soc. Ontol. 4, 157–185. doi: 10.1515/jso-2018-0025

Frega, R. (2019). “The normativity of democracy,” in Pragmatism and the Wide View of Democracy, ed. R. Frega (New York, NY: Springer), 63–99. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-18561-9_3

Gentzkow, M. (2016). Polarization in 2016. Toulouse Network for Information Technology Whitepaper, 1(Stanford).

Gerring, J. (2004). What is a case study and what is it good for? Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 98, 341–354. doi: 10.1017/S0003055404001182

Gilabert, P., and Lawford-Smith, H. (2012). Political feasibility: a conceptual exploration. Polit. Stud. 60, 809–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00936.x

Guerrero, A. (2024). Lottocracy: Democracy Without Elections. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198856368.001.0001

Habermas, J. (1975). Legitimation Crisis, Vol. 519. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. doi: 10.3817/0975025210

Habermas, J. (2017). “Three normative models of democracy,” in Constitutionalism and Democracy (London: Routledge), 277–286. doi: 10.4324/9781315095455-16

Haddad, F. (2017). ‘Sectarianism' and its discontents in the study of the Middle East. Middle East J. 71, 363–382. doi: 10.3751/71.3.12

Haggard, S., and Kaufman, R. R. (1994). The challenges of consolidation. J. Democr. 5, 5–16. doi: 10.1353/jod.1994.0067

Halkier, B. (2011). Methodological practicalities in analytical generalization. Qual. Inq. 17, 787–797. doi: 10.1177/1077800411423194

Halmai, G. (2024). From liberal democracy to illiberal populist autocracy: possible reasons for Hungary's autocratization. Hague J. Rule Law 16, 439–463. doi: 10.1007/s40803-024-00231-6

Hamid, S. (2022). The Problem of Democracy: America, the Middle East, and the Rise and Fall of an Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780197579466.001.0001

Hamid, S. (2023). The blocked road to democracy: culture wars in the arab world and the end of politics. Middle East J. 76, 531–537. doi: 10.3751/76.4.30

Helgest, J., Merten, L., Niedringhaus, J., Rosenthal, M., and Walz, K. (2022). A New Game in Town: Democratic Resilience and the Added Value of the Concept in Explaining Democratic Survival and decline (No. 2206) (Mainz).

Helms, L. (2023). Political oppositions in democratic and authoritarian regimes: a state-of-the-field(s) review. Gov. Oppos. 58, 391–414. doi: 10.1017/gov.2022.25

Herman, L. E. (2016). Re-evaluating the post-communist success story: party elite loyalty, citizen mobilization and the erosion of Hungarian democracy. Eur. Political Sci. Rev. 8, 251–284. doi: 10.1017/S1755773914000472

Hetherington, M. J. (2009). Putting polarization in perspective. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 39, 413–448. doi: 10.1017/S0007123408000501