- Department of Democracy Studies, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany

Among the believers of Islam, no central, universally accepted institution exists that could decide authoritatively on the interpretations of Islamic norms. Today, internet users encounter an enormous diversity of Muslim and non-Muslim authority claims to interpret the norms of Islam. But which type of norm interpretation dominates when users search on Google and YouTube for information on the Islamic rulings on apostasy and theft? Drawing on the literature on the concept of authority and its application to the religious field as well as on the theory on religious markets, the method of a manual search on Google and YouTube was chosen to analyze the top 15 search results on each platform on the topic of apostasy in Islam as well as the issue of theft. The analysis revealed that neither conservative Islamic perspectives nor secular content nor other types of interpretation prevail unchallenged. The wide variety of interpretations of the most diverse Islamic commandments by the most diverse actors (secular and Muslim, including followers of a rigid Sunni Islam as well as liberal Muslims) ensures that divergent interpretations are always just a few clicks away. Searches on Google and YouTube on the Islamic ruling on apostasy revealed that lots of content tried to challenge its validity from a secular view infused with Islamic scripture-based reasoning. The search results for content on Google and YouTube on the Islamic ruling on theft showed a prominence of conservative Muslim positions defending the legitimacy of the punishment of amputation which is incompatible with the principles of liberal democracy. However, the liberal Muslim position renouncing the punishment was also present, as well as anti-Muslim videos. It is argued that governments as well as actors of civil society that want to improve the cohesion of society and stimulate support for liberal democracy among Muslims need to think about ways how liberal interpretations of Islamic norms that are compatible with democracy can be made more visible online—without infringing on the freedom of religion or strangling the religious market.

1 Introduction

In the realm of the religion of Islam, there is no recognized central authority that could claim to interpret the entirety of Islamic norms in a binding manner. Therefore, the fact that a large number of people and institutions today claim authority over the correct interpretation of Islam and its commandments cannot be considered a modern innovation. The classical era of Islam already knew the coexistence of various institutionalized roles that could exercise authority. Nevertheless, contemporary Muslims living in predominantly non-Muslim states that are organized as liberal democracies are confronted with a degree of plurality of authority claims to interpret Islamic norms that is historically unprecedented.

Today, diverse and conflicting interpretations of Islamic norms are readily accessible, especially but not exclusively on digital online platforms. On the internet, an instant comparison of the exegesis of the rules of sharia on various topics can be easily conducted regarding its content and popularity. Therefore, I argue that this competition of interpretations can be best described as a “religious market”, a concept developed by Berger (1963), Stark and Finke (2000) and later refined by Stolz (2006). Drawing on the theory of non-Muslim Islams developed by Petersen and Ackfeldt (2023), I will show that non-Muslim actors also compete in the market of claims to authority on the interpretation of Islamic norms. I will then explore the micro market of interpretations internet users will reach when they search for content on the Islamic ruling on apostasy (ridda), the abandonment of Islam, as well as the Islamic ruling on theft, using the platforms of Google and YouTube. I will discuss the following research question: Which type of norm interpretation dominates when users search on Google and YouTube for information on the Islamic rulings on apostasy and theft? I expect that on Google, Muslim and non-Muslim content is almost equally visibly present, but that in contrast, interpretations posted by Muslim actors with conservative, sometimes rigid views on these controversial rulings will dominate the market on YouTube, due to the successful drawing by preachers on the long tradition of oral transmission of Islamic authority and its employment on the internet that secular interpreters of Islamic commandments cannot easily match. To answer my research question, I will first define the concept of “authority”, in particular its significance in the field of religion. Next, I will explain the concept of the religious market and its operationalization to describe the plurality of Islamic claims to authority. Then, I will analyze the micro market on the two politically controversial topics by conducting a manual search for the first 15 results on Google and YouTube for both the search queries “Islam Ridda” and “Islam Theft” and attributing the results to the categories secular, anti-Islamic and Islamic (the latest having several subcategories). After presenting my results, I will briefly discuss what this competition of Muslim and non-Muslim interpretations means for social cohesion and point to questions left open for further research.

2 On the concept of authority

The concept of authority has long been established in the social sciences, but is has been associated with various, differing meanings. Following Weber (Weber, 1980, p. 122), social scientists often understand the term as a synonym for legitimate rule. However, actors who claim Islamic authority only exercise power if their decision are enforced by means of state coercion. This is not the case in liberal democracies with non-Muslim majorities. Whyte (2024, p. 11) therefore argues that “Islamic religious authority […] relies on discursive and non-discursive means to transmit, debate, embody and exchange religious knowledge without recourse to force or violence. Yet, this pure religious authority was often fused with political power “in early Islam, and continue[s] to be in many Muslim-majority countries” (12).

Drawing on Horkheimer, authority can also refer more generally to influence recognized as legitimate (Schultze, 2010). This sense of the word seems to be the most appropriate when it comes to the context of Islamic norms. Horkheimer himself understands authority as “affirmed dependence” (German: “bejahte Abhängigkeit”, Horkheimer, 1936, p. 24). Actors asserting religious authority do not claim to be the source of authority themselves, because the basis of religious authority is always the “claim to reflect God's will, and the core argument between religions and between streams within religion is over which [interpretation] most faithfully reflects this will” (Firestone, 2013, p. 701), thereby limiting their authority claim. At the same time, however, their claim is also comprehensive, as the commandments of (monotheistic) religions can potentially extend to all areas of life. This certainly applies to Islam. The discipline of fiqh, Islamic jurisprudence, which interprets the entirety of the commandments contained or derivable from the Islamic sources, in particular the Quran and the Sunna, the “tradition” of the Prophet, emerged as early as the classical period of Islam. From the 10th century onward, jurists endeavored to provide information on the furthest extent of issues that could possibly be regulated by law (Rohe, 2011, p. 76). The ruling of sharia extents to the area of interpersonal coexistence (mu‘āmalāt), which also requires legal regulation according to secular understanding, as well as to the definition of ritual obligations toward God (‘ibādāt) not subject to secular law (Rohe, 2011, p. 9–13).

In this paper, the term “Islamic authority claims” is intended to cover all statements with which Muslim actors claim to interpret the commandments of Islam correctly and thus bindingly. The broader concept of “Islam-related claims to authority” encompasses all statements claiming the correct interpretation of Islamic commandments—regardless of whether they are made by Muslims or non-Muslims. Non-Muslims can claim “the right to speak on Islam”, but not “in the name of Islam” (Krämer and Schmidtke, 2014, p. 12). Their claims to authority are rejected by many Muslims as illegitimate in view of their external perspective—and yet Muslims are exposed to them as they are part of the plural discourse on Islamic norms (see Section 2.2.).

The question whether religious authority in the digital sphere is of a different kind than authority in the real world and whether religious authority claims spread online tend to challenge or rather reaffirm traditional religious authorities has been controversially debated in the research literature (Campbell, 2010, p. 251f.). Heidi Campbell suggested that different forms of religious authority in the digital sphere could be identified, namely in the form of (a) hierarchy and roles, (b) structure, (c) ideologies and beliefs (which are the focus of this study) and (d) religious texts (252). Yet, “the fact that online and offline power structures are becoming increasingly intertwined” (274), a development that has accelerated in the last decades, make it seem possible that increasingly digital authority loses its specifics in comparison to real-world religious authority – at least as long as AI-generated interpretations of religious norms that are outside the scope of this article are disregarded. Drawing on Horkheimer's insight that people voluntarily accept the authority of others as they believe that they are competent to make judgement on certain issues, it is assumed that the feature of voluntarism is even more pronounced in the digital sphere: While people may face social sanctions if they disobey imams' or scholars' advice whom they might meet in real life, digital authority cannot rely on social pressure, but needs to cope with the mechanisms of digital platforms to gain attention in order to be relevant.

2.1 The development of Islamic claims to authority in the diaspora in liberal democracies

In liberal democracies, there is a greater plurality of Muslim actors who can claim authority to interpret Islamic norms since these countries are governed by the idea of religious freedom and lack long-established Islamic institutions. It is only in the last six decades that followers of Islam became permanently established in (Western) Europe (Nielsen, 2004, p. 1), North America, Australia (Whyte, 2024) and New Zealand.

In West Germany, greater immigration of (predominantly Sunni) Muslims only began with the recruitment agreement with Turkey in 1961 to supply workers in order to meet the growing demand for industrial labor. It was not before the 1970s that the first permanent mosques were built, which were usually run by laypeople. Over the decades, different nationwide federations of mosques were established that had cordial relations at times, but engaged in fierce competition with each other in other periods, despite most of them sharing a Turkish Sunni profile (Schiffauer, 2010, p. 44–100, Heimbach, 2001, p. 86–95). In other Western European countries like the UK and France, Muslim immigration led to a similar competition between mosque associations and other institutions claiming the authority to interpret the commandments of Islam (Nielsen, 2004, p. 13–19 and 42–49, Lacroix, 2011, p. 42).

The advent of the internet brought perhaps the most profound change to the field of Islamic claims to authority. In the 1990s, the establishment of the World Wide Web and eventually of specialized websites such as the Qatari portal IslamOnline.net (Gräf, 2010, p. 120) ensured that anyone with open access to the Internet can view numerous interpretations of Islamic commandments claiming authority. In addition, the new medium offered virtually anyone the opportunity to publish their own interpretations of Islamic commandments—even without the necessary professional qualifications. When the video platform YouTube was opened in 2005, numerous Muslim protagonists discovered it as an environment for presenting their views on Islamic doctrine and practice and, according to their self-image, practiced Islamic dacwa (invitation, call) by trying to reach out to Muslims and, in many cases, non-Muslims with their videos, calling on viewers to follow Islam and its commandments in what they considered to be the correct way (Wiedl, 2017; Bunt, 2022). Later, other social networks such as Facebook and Twitter as well as messenger services, particularly Telegram, were also used for these purposes. On these platforms, the protagonists can use their own channels to build a specific target group (Klevesath, 2021, p. 11–14). Many of the Sunni Muslim protagonists particularly active on social media can be assigned to the rigid radical current referred to as “Salafism” (El-Wereny, 2020).

While liberal democracies allow for an amount of freedom and pluralism of legal opinions that is largely unknown to Muslim majority countries mostly under authoritarian rule, Muslim actors making authority claims in Western Europe and other so-called Western countries are nevertheless seriously “impacted by Islamophobic narratives and securitization policies that inhibit Muslims from participating in civic life in fear of anti-Muslim bigotry” (Whyte, 2024, p. 2).

2.2 The growing prominence of non-Muslim authority claims to interpret Islamic norms

As it became increasingly clear in the decades following the Second World War that the presence of Muslims in Western Europe would not be a temporary phenomenon, the interest of non-Muslim actors in Islam and the interpretation of Islamic norms also grew, especially in academia and even outside the field of Islamic studies. With the coverage of the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the media discourse on Islam and its norms also became increasingly important, although the focus was primarily on politics and the portrayal of Muslim actors as a challenge to the West (Karis, 2013, p. 122 f.) In many cases, actors who are not bound to a religious perspective also claim to correctly explain the content of Islamic norms. Sometimes secular (i.e. not religiously bound) scientific methods of data collection and evaluation are used or journalistic standards are applied to ascertain the authority to correctly convey the meaning of Islamic norms.

The claims to authority by non-Muslim actors in relation to Islam and its norms have only become the subject of academic analysis in recent years, although the existence of the phenomenon has long been recognized. As early as 2006, Krämer and Schmidtke explained that the “nature, scope and locus of religious authority” are difficult to determine, especially in the modern age, because: “More and more groups and individuals are claiming the right to speak on Islam and in the name of Islam.” (Krämer and Schmidtke, 2014, p. 12.) They identified social scientists—who are often non-Muslim—as relevant actors claiming authority to interpret Islamic norms. Petersen and Ackfeldt point out that—among others—non-Muslim journalists and especially non-Muslim politicians can claim to be bearers of authority regarding the interpretation of Islamic norms, as liberal leaders like Barack Obama as well as right-wing politicians have publicly presented their interpretations of Islamic norms by referring to the Islamic sources of Quran and Sunna and interpreting them, thereby making competing claims of Islam being a religion of peace or of intolerance. Such non-Muslim interpretations of Islam are not only relevant for the self-image of liberal democracies' societies, but also impact Muslims themselves as they cannot completely avoid exposure to it (244–253).

In order to analyze the competition between the nowadays very numerous actors who make Islamic or Islam-related claims to authority, the concept of the “religious market” is presented below. I will examine to what extent it can be utilized to understand the competitive situation under consideration here.

3 Theory—The concept of the religious market and its application to Islamic claims to authority

Social science regularly conceptualizes the spheres of the economy and of religion as two subsystems of modern society among many others that fulfill different functions (Luhmann, 2000, p. 283). Thus, the postulate that there are also markets in the sphere of religion, which is related to the transcendent, may initially seem counterintuitive. Nevertheless, the social science concept of “religious markets” has existed since the 1960s (Hero, 2018, p. 572) In 1963, Berger suggested that the various Protestant denominations should be perceived as “economic units which are engaging in competition within a free market” (Berger, 1963, p. 79). Stark and Finke developed the concept of the religious market on the basis of the “rational choice” concept into a universal model to explain the coexistence of different religious actors. According to this model, a subsystem is formed in every society in which all religious activities take place and which can be described as a “religious economy”. People demand religious goods such as religious gatherings and other offerings, which are made available by various providers (Stark and Finke, 2000).

Today, the concept of the religious market has received a broad academic reception. However, the approach has also been criticized (Hero, 2018, p. 574–577): A meta-analysis by Mark Chaves and Philip Gorski, for example, showed that a religious market has no positive effect on the demand for religion as claimed by Stark and Finke (Chaves and Gorski, 2001). Since the effect on the demand for religion is not part of this study, the point will be disregarded here. In addition, Jörg Stolz criticizes that the representatives of the “rational choice” approach have not defined what religious goods are and argues that different forms of religious goods exist. Only “consumer goods” and—insofar as state and cultural conditions permitted—“membership goods” could be allocated on the market. For example, the office of a pastor or of an imam cannot legitimately be bought. Even “personal goods” such as religious knowledge are not available on the religious market (Stolz, 2006, p. 14–28; Hero, 2018, p. 579). Nevertheless, people claiming religious authority can offer their knowledge to advice seekers, thereby placing it on a religious market. Stolz also expanded the religious market approach to include a theory of religious-secular competition for the demand for services but also for people's time resources. According to this theory, providers of religious goods not only compete with actors within the religious spectrum, but also with secular actors. For example, the secular welfare state can compete with religious charity (Stolz, 2006, p. 29–37).

The application of the concept of the religious market to the field of Islam has triggered a controversial debate, as the religion differs in many aspects from Protestantism for which the concept was first developed. However, François Gauthier argues that due to the worldwide dominance of the sphere of economics, the prevailing logic of the market also pushed contemporary Islamic actors to put an emphasis on visibility and compete with others for attention on social media (Gauthier, 2018, p. 392–403). Therefore, the concept is suitable for analyzing the coexistence of different authority claims related to Islam—at least in the present age. Although not all religious goods can be allocated via a market, the utilization of knowledge about religion, including Islam, can—following Stolz—certainly be mediated via a market as religion-related “consumer goods”. For this to happen, however, the extensive absence of state regulation and social pressure must ensure that individuals are free to choose their sources of knowledge. Islamic and secular actors can also compete with each other when it comes to the demand for Islam-related knowledge (even if practicing Muslims in particular are generally likely to rely exclusively on the authority of Muslims). The large internet platforms in particular create markets for Islam-related knowledge, which can be searched for using specific search terms. However, internet platforms provide no plain level field. Instead, to a large part, algorithms predetermine what content users will see and which search hits will be placed on top of the list or further below. Google does not disclose to the public how exactly algorithms structure the search results. Therefore, the market of religious authority claims on Google and YouTube is not unrestricted, but regulated by mechanisms hidden from external scrutiny. As commercial platforms, they create revenue not by conforming with qualitative standards for information, but by displaying content that will keep users on these platforms—which (especially for YouTube) is often the case with controversial content. Also, they amplify content suitable to be placed next to commercial advertisement. Actors making claims to the authority to interpret Islamic rulings need to adapt to the digital environment by ensuring that their content attracts attention—otherwise, their interpretations are threatened to remain irrelevant in the digital realm.

4 Methodology

In order to analyze competing authority claims on Islamic norms, the interpretations of the rulings on apostasy and theft were identified as suitable cases for an exemplary qualitative analysis of Islamic commandments which in their orthodox interpretation run counter to norms of liberal democracy protecting freedom of religion and physical integrity, thereby outlawing corporal punishments: The established teaching of orthodox Islam calls for the death penalty for leaving Islam and for hand amputations for theft. Although these commandments are not representative for the entire body of Islamic law, covering commandments for areas such as ritual practice that—by and large—are completely compatible with liberal democracy, it is expected that due to their controversiality, these rulings are debated more intensely than others and are therefore particularly suitable to analyze differences between secular, liberal Islamic and conservative Islamic interpretations. The Arabic word “ridda” (sometimes spelled “riddah”) literally means “refusal” and is the technical term for apostasy. Although there is no Quranic verse calling for punishment of apostates by human agents, a prescription to put apostates to death can be found in the prophetic tradition.1 Classical Islamic law sees the death penalty for (conscious) apostasy as the default punishment, although no consensus exists on the question whether it can be considered as one of the ḥudūd punishments, the scope of which is regarded as definitely settled by the sources of Islam. For example, the Hanafi school sees confinement and corporal punishment (repeated beating) as appropriate for women (Peters and De Vries, 1976, p. 4–7). Present-day interpreters often see the punishment of apostasy as being conditioned on the existence of an Islamic state that should persecute apostasy among its Muslim citizens—not on religious grounds but as the political crime of treason. A prominent example for this position is given by Rachid al-Ghannouchi, the leading thinker and politician of political Islam in Tunisia (Klevesath, 2014). Other than the sanction on apostasy, the ruling on theft is explicitly anchored in the Quran. Verse 5:38 calls for the amputation of the hands for both the male and the female thief.

In order to analyze content that many internet users searching for the Islamic ruling on apostasy and theft would see, the most popular search engine worldwide—Google—was selected. As video content is also popular with internet users not only for entertainment but also as a source for information, the Google-owned video platform YouTube was identified as a second website to be included in the analysis. YouTube was selected as a platform since it is the most popular Internet video platform globally as of 2025.2 The key words “Islam Ridda” and “Islam Theft” were used on both Google and YouTube. In the settings of the Google search engine, the option to only show English-language content was selected. Both searches were conducted on a desktop computer running the Chrome browser under a Windows operating system, using a German IP address.3 Therefore, a locality bias cannot be ruled out. The browser was not logged in with a google account to prevent the personalization of search results. No additional search parameters were set. However, it cannot be guaranteed that other users from other locations, using different browsers, operating systems and settings would not have received different results (the change of search results over time is a given that can be ignored for the purpose of this study). A generic search query was deliberately selected in order to focus on hits that are likely to be displayed to users who have little or no familiarity with Islamic law and therefore do not provide more keywords searching for Islamic rulings on specific situations. Some of these users who are inexperienced with sharia law are likely to be non-Muslims who are not looking for an authority to guide their personal lives, but who are interested in clarifying Islamic norms. However, the use of the keyword “ridda” implies some acquaintance with Islamic discourse as the Islamic technical term for apostasy is unknown to the majority of non-Muslims. Nevertheless, the keyword was used here since the search query “apostasy” would not have been a good alternative as it is yet another technical term that might be unknown to many (lay) internet users. It can also be assumed that young Muslims use general search terms more frequently. Important questions such as the validity of sharia commandments in predominantly non-Muslim areas are unlikely to be addressed.

In a Google search query, the various entries can be compared using the name of the source, the URL and a short text, the so-called “snippet”. On the Google video portal YouTube, the search hits can be compared using a preview image from the video, the title, the time of its publication, the snippet and, in particular, the number of views and the duration of the video, which can give an indication of its content, as more information can be accommodated in a longer clip. Above all, however, the length signals to users the amount of time they have to invest to consume the video—and the necessary time commitment can be considered a “shadow price” for offers for which no financial costs apply, as time is also a limited resource. When internet users search for Islam-related knowledge on Google and YouTube, offers from a wide variety of actors appear instantly, which can initially only be compared on the basis of criteria that have nothing to do with the traditional criteria for evaluating Islamic claims to authority, such as affiliation to a particular school of law. The various search hits on Google and YouTube constitute a micro market of different information offerings on the two before-mentioned Islamic commandments. No in-depth qualitative content analysis of the individual contributions is carried out here. The results will be categorized manually as Islamic, secular or anti-Islamic content. All sources that explicitly state to be written from a Muslim point of view or that imply such a perspective by affirmatively using Islamic language will be classified as Islamic. In addition, Islamic content will be sorted according to five subcategories: (1) conservative (all Sunni content promoting in principal a literal reading of Islamic sources, encompassing a vast spectrum reaching from Sunni mainstream to Salafi positions), (2) Shia (encompassing an even wider spectrum from conservative to liberal positions within Shia Islam), (3) liberal (content promoting a non-literal reading of Islamic sources, thereby questioning traditional understandings of Islamic teachings on apostasy and theft), (4) mixed (blended content out of the first three subcategories) and (5) other Islamic content (which could not be attributed to any other subcategory). Secular sources are texts or videos that appear attempting to deal with Islamic rulings from a neutral perspective—irrespective of possible religious beliefs of the author(s) of the text or clip. All content that contains explicit polemics against the religion of Islam or some Islamic norms will be classified as anti-Islamic. Since the content is categorized manually, the categorization might to some extent be prone to subjectivity—some texts or videos might not easily fit into one category. The first 15 hits are considered in each case through a qualitative summary assessment by the author, following the assumption that results listed further down below attract only very limited attention by users. It is noteworthy that the top search results are not simply a reflection of the users' interests and preferences as indicated by search queries, but results significantly shaped by algorithms employed in the Google search engine and on YouTube, promoting certain content and limiting the reach of other websites and videos.

5 Search results for the keyword “Islam Ridda”

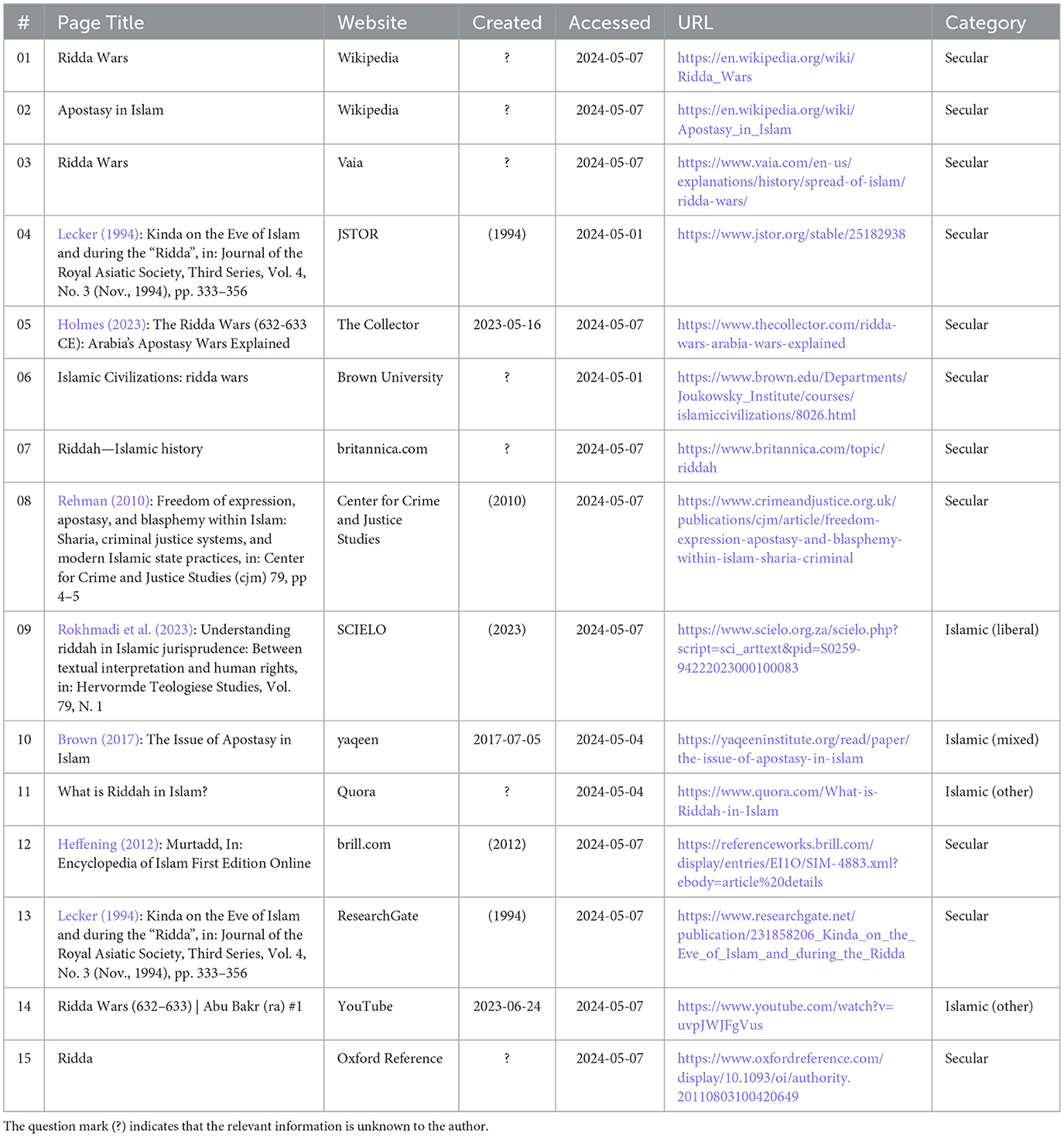

The results for the keywords “Islam Ridda” both on Google and YouTube (see Table 1) deliver a lot of content not on the Islamic ruling on apostasy per se, but on the so-called “Ridda Wars” that took place on the Arabian Peninsula in 632/633 when several Arab tribes renounced Islam or at least refused to pay taxes to Medina after the death of the prophet Muhammad. Nevertheless, these military campaigns were legitimized by the religious prohibition of defecting from Islam (Lecker, 2012). Some retrieved YouTube content, however, is not concerned with the Islamic ruling on apostasy at all.

5.1 “Islam Ridda” on Google: the domination of secular content

On Google (see Table 2), the first two search results that appear are Wikipedia articles, the first dealing with the Ridda Wars and the second one with the phenomenon of apostasy in Islam. Both are written by an unknown number of mostly anonymous authors and contain a secular perspective. The third result leads to the website Vaia, an environment for study materials. The content is secular in nature, exclusively text-based and seems to cater to high school or undergraduate university students. The names of the authors of the content are not provided. An academic journal article (secular) authored by Michael Lecker is listed as the fourth result, delving into the fate of the Kinda, a tribal confederation in Arabia at the time of the Ridda Wars. The fifth result leads to a website called “The Collector”. Users are offered a long history article by Robert Holmes, who is introduced as an academic specialized in ancient and medieval history as well as archaeology. The text is written from a secular perspective in an entertaining, easily accessible style and accompanied by many photos of archaeological findings and even a still from a motion picture. It can be assumed this is meant as content for people who study history solely as a hobby. Search result number six (secular) is provided by the “Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology & the Ancient World” of Brown University. It is an anonymous, very brief and poorly edited factsheet on the Ridda Wars, possibly authored by a student as part of an assignment. The style of the page might indicate that it was created in the 1990s or early 2000s. The seventh result listed (secular) is an article on the Ridda Wars of the Encyclopædia Britannica. The name of the author is not provided.

Search result number eight retrieves a text that delves into tafsir, the exegesis of the holy Quran and the interpretation of the Sunna, the second most important source of Islam. Javaid Rehman, a law professor of Brunel University London, argues that the validity of the death penalty for apostates is questionable from an Islamic point of view, as the Quran does not mention such a punishment. While he acknowledges that the Sunna indeed contains a commandment to kill apostates, he questions the validity of the tradition as—according to Rehman—there is no evidence that the prophet himself ever executed an apostate. He states that the retention of severe laws against apostasy in Muslim-majority countries can often be explained by attempts of authoritarian rulers to use the accusation of apostasy against regime critics. The text is a borderline case—the methods of Islamic fiqh are employed. Yet, the text is classified as secular as it is not directed to an exclusively Muslim audience and does not make religious truth claims. Search hit number nine leads to an academic article authored by four Indonesian Islamic theologians and fuqahāc, i.e., specialists for the interpretation of sharia. The argument of the authors is very similar to that of Rehman: The validity of the commandment of the Sunna to execute apostates is held to be questionable due to the lack of evidence for its actual application in early Islamic history. The execution of apostates is seen as a violation of human rights, which are—the authors argue—enshrined in the Quran, thereby implying that Quranic commandments supersede those from the Sunna. Since the content is presented as fiqh scholarship, it can be classified as Islamic. As a literal reading of the Sunna is questioned, the content is categorized as “liberal”.

The tenth result provides an article that tries to define the scope of the Islamic sanction on apostasy. It is provided by the Texas-based Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research.4 Jonathan Brown begins his article “The Issue of Apostasy in Islam” with invoking God with the Basmalah, thereby making clear that he argues from an Islamic perspective. Nevertheless, the style of the article largely follows the conventions accepted in the halls of largely secular Western academia. He argues that apostasy could be punished by death in Islamic history, but that the application of a punishment and its severeness was left to the discretion of Islamic rulers. However, as the punishment inflicted by the ISIS terrorist organization on people it deemed apostates shocked non-Muslims and Muslims alike—and even caused some Muslims to doubt their faith –, Brown argues that it seems wiser from an Islamic perspective to abstain from punishments for apostasy as the interest of Islam is better served by restraint. As the ruling on apostasy is upheld in principle but seen as inappropriate for current circumstances, the position taken is classified here as a mix of conservative and liberal positions.

The eleventh search hit leads to the page Quora, a website offering expertise on diverse subjects provided by people from very different fields. This is a platform at which Muslim and non-Muslim claims to authority can appear in close proximity to each other. The question “What is Riddah in Islam?” is answered by a person named Ian Hunt who claims a BA degree in “Islamic Sharia Law and Islamic Creed”, thereby claiming to write from an Islamic perspective. In his purely descriptive post, he explains that the term regularly refers to apostasy in an Islamic context, but can sometimes have the more general meaning of “going back” and refer to people who have not left Islam but who instead renounced a commitment, as in the case of one group in the so-called Ridda Wars that refused to pay taxes to the Islamic community. Since no specific interpretation of the ruling is offered, the content is classified as “other”.

Search result number 12 (secular) leads to the lemma “Murtadd” (the Arabic word for “apostate”), authored by Wilhelm Heffening, written for the first edition of “Encyclopedia of Islam”, the standard encyclopedia of Western Islamic studies that was published in the first half of the twentieth century. Result number 13 (secular) is a duplicate of the journal article by Michael Lecker already retrieved (search result number 4) that is offered via the website “ResearchGate”. Search result number 14 leads to an animated YouTube clip of the channel “Historische Schlachten” [historic battles]. Although the channel's name and description are shown in German, the clip is in English (as all the other videos on the channel). Interestingly enough, the clip narrates the events after the death of Muhammad from a Muslim point of view, using formulas of Muslim piety such as the eulogy for the prophet Muhammad, even though the channel also offers narrations of other battles of world history that do not involve Muslim parties. It clearly serves entertainment purposes and does not bring forward authority claims on Islamic norm interpretation, therefore classified as “other”. The fifteenth search hit (secular) is a short entry in the digital dictionary “Oxford Reference”, explaining that the term “ridda” refers to apostasy from Islam and the Ridda Wars.

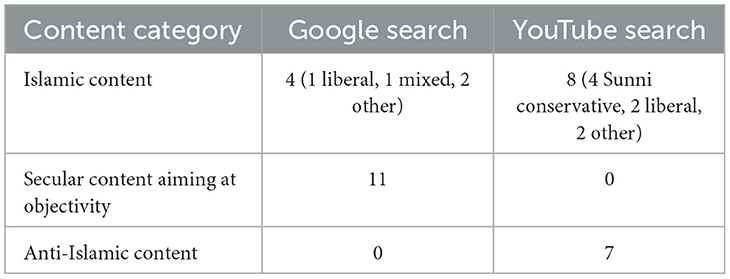

Contrary to the expectation that Muslim and secular content would be equally present on Google, it was found that secular content dominates the micro market on Google (11 out of 15 results). One of the texts classified as secular (Rehman) was a borderline case—the classification was due to the lack of religious truth claims, although methods of Islamic fiqh were employed in the text. But despite the fact that the categorization is prone to subjectivity, the dominance of secular content is certain. 8 of the 15 results were related to the Ridda Wars of early Islamic history and did not claim the authority to interpret the Islamic ruling on apostasy. Only four of the 15 analyzed texts were really trying to assert the authority to interpret the Islamic ruling on apostasy (search results number 2 and 8–10). Two of these articles (the Wikipedia article and the essay by Rehman) are of a secular nature, two others provide Islamic content (Brown and Rokhmadi et al.). Only Brown tries to justify the legitimacy of the Islamic punishment of apostates in general (but calls for the discontinuation of its application in modernity due to the lack of acceptance in society). Rokhmadi et al. brings forward a liberal reading, while the Wikipedia article lists diverse Islamic viewpoints from a secular perspective and does not provide a conclusion on whether a punishment of apostasy can be Islamically justified. Nevertheless, the liberal interpretations prevail on Google.

5.2 “Islam Ridda” on YouTube: the realm of polemics

The domination of secular and often scholarly content on Google is not mirrored on YouTube (see Table 3). On this platform, videos of Muslim actors dominate.

The first video displayed after entering the search query on YouTube is a clip by the Saudi cleric Assim al-Hakeem, known for his rejection of democracy.5 In the video classified here as conservative, he argues that a conscious Muslim has already agreed to accept the death penalty for apostasy as it is part of the prescriptions of Islam Muslims believe in. For people who never entered Islam, the punishment would not apply. Even persons skeptical about putting people to death for apostasy would agree to apply the death penalty to someone who would rape and kill a close female relative. The second video displayed is called “Proofs of Prophethood 21: Ridda Wars”, posted by the channel “Farid Responds” that according to the channel description is “dedicated to refuting anti-Islamic content”. In it, “Farid” presents Quranic verse 5:54. The verse predicts that if people from the prophet's community will revert from Islam, God will bring forth another people who will act hard toward the infidels and fight for God's cause. The video is classified as conservative as the legitimacy of the death penalty is implicitly upheld.

The third video is a YouTube short. It is presented by the anti-Islamic channel “Apostate Prophet” and is provided by Ridvan Aydemir,6 an ex-Muslim criticizing his former religion. The video shows a small clip from a longer video from Assim al-Hakeem mentioned above. In it, al-Hakeem declares that when Muslims conquer a foreign country, they first have to offer the inhabitants the opportunity to embrace Islam, or if they refuse, to pay the Jizya tax for non-Muslims. Only if they reject both options, Muslims have to fight the non-Muslims and could legitimately enslave them after victory. Al-Hakeem mentions that Muslims will become stronger in 40 or 50 years. The caption of the channel sharpens the message and claims the cleric threatens non-Muslims with enslavement in the coming decades. The fourth video (anti-Islamic) is another short provided by the same channel. The male host of the channel utters the shahada, the Islamic creed, pretending to have reverted to Islam in apparent mockery of the religion. The fifth video is another short by another anti-Islamic channel named “Infidel Noodle”, a female YouTuber claiming to be a former Sunni Muslim. In the video, she looks at the viewer with the lower part of her face covered (probably to remain anonymous). At the beginning, various captions like “Mohammed was a feminist” and “Islam gave women rights” are shown. After a few seconds, photos of women whose faces and bodies are completely covered by Islamic dresses are depicted, alongside various quotes from the Quran and Hadith that are presented as proofs of the misogynist nature of Islam.

The sixth video, classified as “Islamic (other)”, is also a YouTube short, posted by the German language channel “Anas Islam”. According to the channel's self-description, the channel serves the purpose of illuminating the miracles of the Quran and Islam in general. In the short, “Anas” discusses with a female vegan whether it was legitimate to slaughter a pig to provide a new heart valve to a human being. It has to be noted here that the clip is neither related to the topic of apostasy or even Islamic norms in general—the YouTube algorithm seems to deliver a video not matching the search query. The seventh video (anti-Islamic) is another mocking short by the channel “Apostate Prophet” in which the YouTuber jokingly claims Islam to be the only religion that nobody ever leaves—so-called ex-Muslims never had been true Muslim believers before.

The eighth video (conservative) is a 4 min clip from a Q&A session with the famous Indian Muslim cleric Zakir Naik who receives the same question as al-Hakeem about how the death penalty for apostates can be compatible with the Quranic ruling that there is no compulsion in religion. Naik explains that the death penalty for apostates is only applied in an Islamic state, which has to consider the abandonment of Islam as treason that is also severely punished by non-Islamic states. Video number nine (liberal) shows another Q&A session with yet another Muslim cleric, the Canadian preacher Shabir Ally. He gets asked whether Muslims should be free to leave their faith or whether they should be punished. Ally declares that Muslims should be free to abandon Islam without punishment. He provides the heterodox, semi-Quranist opinion that the Quran which guarantees religious freedom is providing the definite ruling and that hadith should only be consulted in cases in which the Quran does not include an understandable, clear ruling. Video number ten—classified as “Islamic (other)”—is the animated video of the Ridda Wars by the historic battle channel already retrieved and discussed above as Google search result number 14.

Video number eleven (anti-Islamic) is a short by the channel “IslamEducation”. The owner of the channel claims to be an ex-Muslim Christian convert now regarding himself as a “warrior” to “Lord Jesus”. In the video, it is argued that Allah is in fact Satan: Allah would convince people that they have no responsibility for the sins they commit as Allah is the actor who makes them commit the sin—but the role of an irresistible actor who leaves people no choice but to sin would normally be attributed to Satan. The video does not relate to the Islamic ruling on apostasy. Video number twelve is a short in Urdu/Hindi language on “Hindu-Muslim Unity” by the channel “ExMuslim Sahil Official Back Up”. Its content could not be analyzed by the author due to language barriers but was classified as anti-Islamic due to the name of the channel.

Video number thirteen “Happy Eid! (except for polytheists)” is another short by another anti-Islamic channel called “ApostateAladdin”. “Aladdin” explains that according to Islamic tradition, Abraham (Ibrahim), who is seen by Islam as a Muslim prophet, destroyed the idols of polytheists while they were celebrating a religious holiday to show them that their religion was ridiculous. The YouTuber sees this story as a proof that Islam lacks the respect for other religions even though it demands non-Muslims to respect Islam. Video number fourteen titled “Muslims & Philosophy” is a short provided by iERA, a charity in England and Wales that according to the channel's “bio” is dedicated to bringing forward an intelligent case for Islam. In the clip, an unknown man in conversation with another male person argues that studying philosophy does not have to be harmful for a Muslim who knows the basics of his faith well. It does not touch on the Islamic ruling on apostasy, but is nevertheless classified as liberal since conservative currents of Islam either restrict or reject the use of philosophy. Yet, since no interpretation of Islamic rulings is offered and some established currents of Sunni Islam such as the Māturidiyya accept philosophic reasoning to certain extent, the video is a borderline case that cannot be categorized with certainty. The fifteenth video “Ali dawah meets a murtad [apostate]” is a short provided by the channel “Dawah Over Dunya” [meaning Islamic missionary work (dawah) trumping the realm of worldly things (dunya)]. The owner of the channel claims to be “devoted to defend Islam” and sees himself as “an independent researcher” but not a “person of knowledge”. The video, classified here as conservative, first portrays a heated word duel between an ex-Muslim Christian missionary and a Muslim preacher who ascertains that Islam commands that the apostate has to be put to death. The YouTuber then provides quotes from the Old Testament sanctioning the death penalty for apostates to show that this commandment is not exclusive to Islam, thereby defending the harsh punishment.

An analysis of the search results shows that the content found on YouTube is very different from the content on Google. The micro market presented on YouTube is a battle zone of diverse polemic actors. Unexpectedly, almost half of the videos (7 videos) were posted by anti-Islamic YouTubers. This can be explained by the fact that entering the keyword “ridda” brings up not only content about the Islamic perspective on apostasy but also clips by YouTubers portraying themselves as apostates and ex-Muslims. Only one anti-Muslim video (“Islam is the ONLY RELIGION That NOBODY LEAVES”) seems to hint at the Islamic ruling on apostasy, scandalizing the perceived lack of freedom for people who want to leave Islam. Both secular and academic content is completely lacking among the retrieved clips. Among the Islamic videos, one video—the clip by Saudi cleric al-Hakeem—is an outright defense of the death penalty of Islam, ignoring that this position is a clear human rights violation. The video by the channel “Dawah Over Dunya” also seems to defend the harsh sanction. Naik takes a more cautious position only justifying the punishment of apostates as traitors in the case that they live in an Islamic state. Only one Islamic video (the Q&A session with the cleric Shabir Ally) contains a genuinely liberal Islamic perspective on the ruling, portraying the punishment of apostates as religiously impermissible (Another Islamic video classified as liberal, “Muslims and Philosophy”, does not deal with the treatment of apostates). The assumption that Muslim clerics, drawing on the oral tradition of Islamic authority and their rhetorical skills, was confirmed: Secular actors do not seem to be able to provide content that generates interest among YouTube users. However, the preachers of anti-Islam are surprisingly able to enter into competition with Islamic clerics. An analysis of the number of views of the videos reveals that YouTube displays a selection of clips with a wide range of popularity: While video 10 was only watched 6,361 times, clip 3 had more than 1,5 million views. Two of the three most popular videos displayed are polemical anti-Islamic videos, the other being video 6 by Anas Islam unrelated to the Islamic ruling on apostasy but ridiculing the ethics of a vegan woman. A mix of (sometimes rarely watched) clips closely fitting the search query and popular videos with content only distantly related to the inquired topic is displayed, probably reflecting the influence of algorithms on the results. The category of conservative Islamic videos is a wide one containing positions reaching from an outright defense of the harsh sanction on apostasy to a call for enforcing it only under special circumstances. The popularity of polemical content might be due to both user demand and deliberate promotion by the platform to capture the users' attention.

6 Search results for the keyword “Islam Theft”

Even though the search query “Islam Theft” (see Table 4) does not invoke a reference to historic events such as the Ridda Wars, only the Google search results analyzed here focus strictly on the Islamic ruling on theft. The YouTube search query again shows a lot of unrelated content.

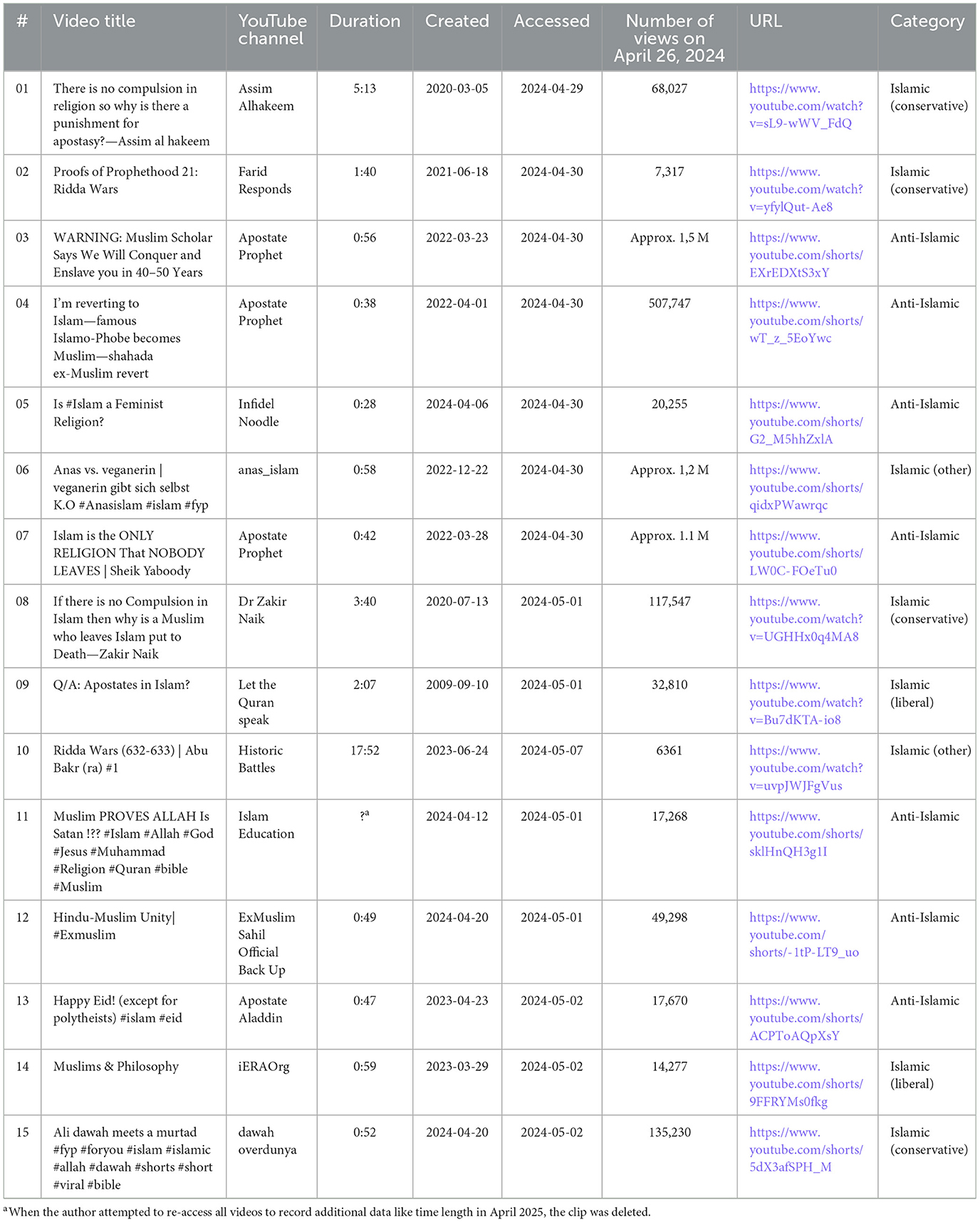

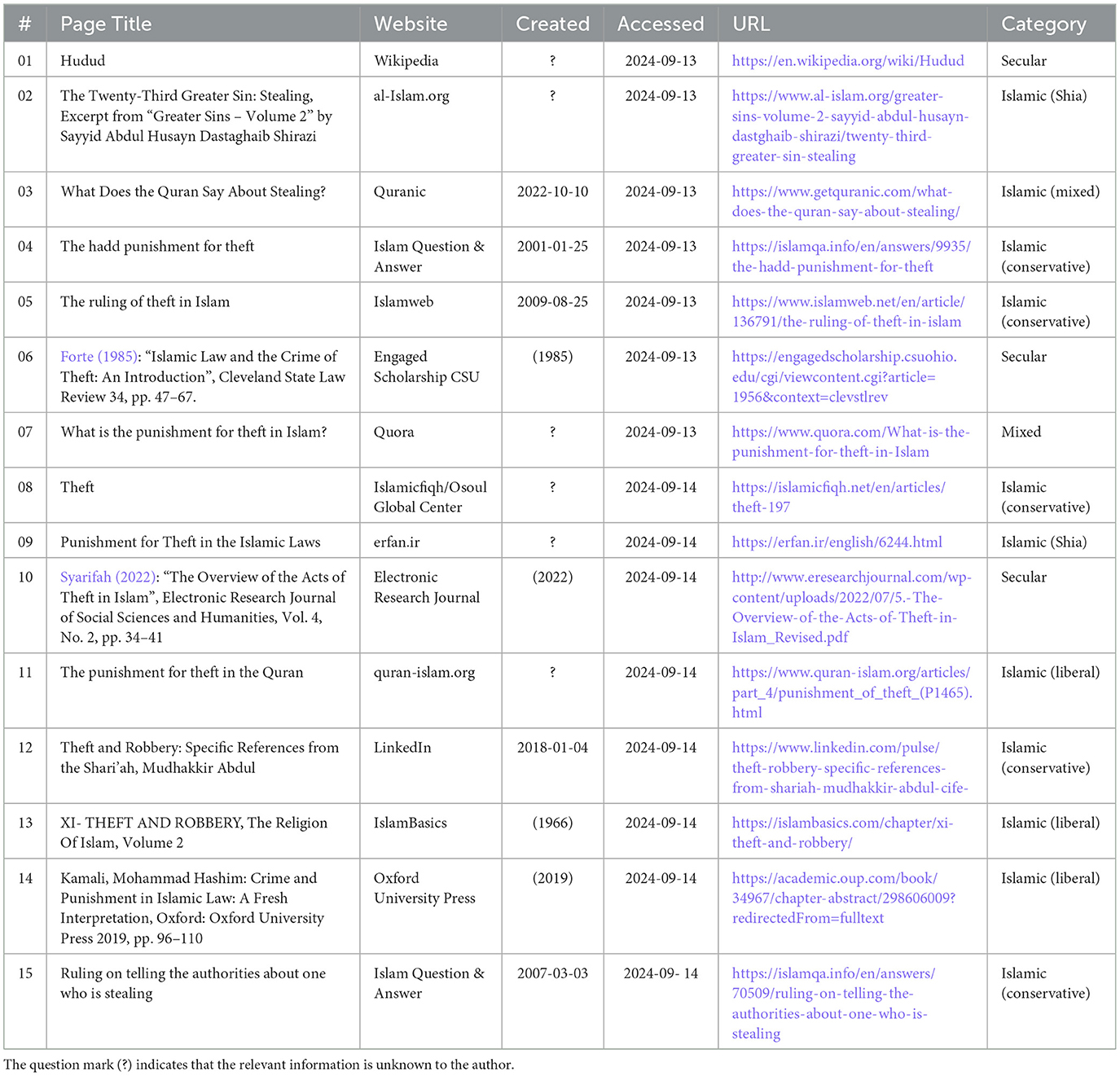

6.1 “Islam Theft” on Google: a mix between different Islamic currents and secular content

Searching for “Islam Theft” on Google (see Table 5), the first search hit retrieved is a Wikipedia article on the “hudud”, i.e., punishments that orthodox Muslims believe have unalterably been defined by God. Written by anonymous authors from a secular perspective, the article lists theft among other crimes as one of the offenses that in Islam are believed to be associated with a fixed punishment. Quranic verse 5:38 calling for hand cutting of thieves is mentioned as textual evidence (dalil). The second result leads to the Shia web page al-Islam.org, offering an excerpt from the second volume of the work “Greater Sins”, authored by the Iranian Shia scholar and follower of Ruhollah Khomeini, Abdol Hossein Dastgheib Shirazi (1913–1981). Although the website is registered in the United States, it apparently has ideological ties to Iran. Shirazi refers extensively to the interpretation of the Quran by 17th century Bahraini Shia scholar Sayyid Hashim al-Bahrani. The excerpt offers instructions on the correct application of the punishment according to Shia Islam (it can only be executed by a judge or a legitimate ruler, the thumb and palm have to be spared) as well as a detailed analysis of the conditions that—according to Shia fiqh—have to be met in order to carry it out. The text also offers a vindication of the punishment against the accusation of the measure being inhuman, arguing that severe punishments are necessary as deterrence.

The third search result leads to the page Quranic, founded by Adam Jamal, the imam of a mosque in the US state of Washington.7 In the article on theft, a couple of Quranic verses dealing with the topic are mentioned besides the famous verse of 5:38. The article refers to verse 60:12, mentioning an oath of Muslim believers to the prophet not to steal, or verse 11:85 warning against using false measure in business transactions. The text offers no conclusion on whether the commandment to cut the thief's hand off is to be understood literally. While it is argued that the commandment is to be comprehended as a “deterrent given by the Quran but also wisdom, mercy and justice as a gift to humanity from Allah”, the text also mentions that according to some modern Quranic scholars, the Arabic word “yad” could also be translated as “wealth” rather than “hand”, so that the commandment could be understood as simply calling for compensation of the victim. Therefore, the content is classified as “mixed”. The fourth entry (conservative) points to the website Islamqa.info founded in the 1990s by the Saudi scholar Muhammad al-Munajjid (born 1961) providing users with advice on Islamic law. Displayed is a Q&A from 2001. An anonymous user asks whether the sparing of the thumb of a thief as practiced in Iran is a deviation from the Islamic Sunna. The anonymous scholar answers in the affirmative, referring to Quranic verse 5:38 as well as several hadiths: the hand has to be “cut off from the wrist”, rendering the Shia application of the commandment an illegitimate innovation (bidca), deviating from divine law. The text refers to a commentary by the Syrian Shaficite scholar Yaḥyā ibn Sharaf al-Nawawi (1230–1277), who is particularly popular among Salafi circles, to explain which conditions need to be met for the punishment to be carried out: the crime has to be proven by two witnesses or a repeated confession by the thief, and the stolen item has to have a value and been secretly taken from a non-public place of storage. The content differs from many other conservative positions as it is openly polemical toward Shia interpretations about the ruling on theft. Search hit number five (conservative) points to the website islamweb.net, a Qatari equivalent to Islamqa.info also founded in the 1990s. The text is almost identical to the answer given on Islamqa.info except for some differences in spelling and different translations of the quotes from Quran and Sunna. However, the original question is not displayed. The text shows the same polemical position toward Shia interpretations.

The sixth search hit leads to an academic article written by an American legal scholar. David F. Forte analyzes the Islamic ruling on theft from a secular perspective and, entering the field of philosophy of law, tries to investigate how the harsh punishment might have been justified apart from the fact that it is explicitly stated in the Quran. He spells out the conditions under which the punishment was deemed applicable by the fuqaha and comes to the conclusion that both judges and scholars had to navigate between the explicit commandment of the Quran and the high value of repentance that is generally cherished by Islam. The text is another borderline case: Although the author reconstructs the perspective of fiqh in-depth, he does not endorse an Islamic viewpoint—therefore, the text is classified as secular. Search result number seven (classified as “mixed”) again leads to the page of Quora, collecting various types of expertise among its users. The page shown provides the answers to various related questions on the topic, among them the question whether the amputation of the hand is actually carried out in present-day Saudi-Arabia. Many answers shown are provided by users referring to their travels to Saudi-Arabia as the basis for the expertise, explaining that the punishment is not carried out in the Middle Eastern kingdom today. Few users state that they have a background in Islamic legal studies. They try to weigh in on the question of the applicability of the Quranic junction.

The eighth search hit (conservative) leads to the Saudi web page Islamicfiqh.net.8 It offers an anonymous exegesis very similar in content and wording to that provided by Islamqa.info and islamweb.net, although differing regarding the hadith references. The condition outlined—deemed necessary for a lawful application for the amputation—are identical to those attributed to al-Nawawi on Islamqa.info and islamweb.net, even though the numeration is different and the text refers to Indian scholar Abul Hasan Ali Hasani Nadwi (1913–1999) instead of al-Nawawi. Search result number nine (Shia) leads users to website erfan.ir—referring to the Arabic term cirfān (knowledge). Erfan.ir is promoted as the “official website” of Hossein Ansarian (born 1944), an Iranian Shia cleric. The text provided, however, is almost identical to the one presented on al-Islam.org. Search hit number 10 leads to another article published in an academic journal. Syarifah, the author of the text, compares Islamic law and Indonesian law regarding theft and comes to the conclusion that the difference is not limited to the punishment, as the definition of the crime also varies. The comparison can arguably be considered as secular, as the author does not take a position on its religious justification.

Search result number eleven (liberal) leads to quran-islam.org, a Florida-based web page offering a heterodox Quranist interpretation of Islam. The anonymous authors hold that all hadiths are inauthentic and should not be followed, as the Quran itself is deemed sufficient for divine guidance.9 Regarding the commandment in Quranic verse 5:38, it is argued that the hands of thieves should only be marked but not severed, as the Arabic imperative “qṭacū” would not imply a complete detachment of the cut object. To support their argument, they refer to Quranic verse 12:31, where the verb is used in the sense of light cutting of the hand. The twelfth result leads to a personal page on the social network LinkedIn. Mudhakkir Abdul, a “Shari'ah Auditor & Adviser” and “Shari'ah Compliance Expert” delves into the relevant Quranic verses and hadiths on both theft and robbery and their interpretation. He argues that the punishment for theft is divinely fixed only in so far as the amputation of the hand is the harshest punishment legally possible. Yet, Islamic law would leave the way open for milder sanctions for repentant thieves. However, as the validity of the amputation punishment is upheld, the content is classified as conservative. The 13th displayed search result (liberal) is the web page “IslamBasics.com”. The anonymous authors claim that they intend to offer books—free of copyright and accessible online—that provide knowledge they deem to be Islamically authentic.10 On the topic of theft, IslamBasics.com provides an excerpt from the English translation of the second volume of “The Religion of Islam”, authored by the Egyptian scholar Ahmed Ghalwash and published in 1966.11 Although Ghalwash argues that the amputation punishment has been carried out in early Islamic times, he approvingly mentions that the Umayyad caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik (ruled 724–743) changed the sanction from amputation to imprisonment and that most Islamic countries do not enforce the cutting of hands in the 20th century. Such a liberal Muslim perspective seems rather exotic nowadays, as many Muslims today (at least conservative ones) condemn the conscious ignoring of rules enshrined in the Quran or the hadiths that are seen as authentic, while the Umayyad dynasty is regularly criticized for their corruption.

Search result 14 points to a book chapter on the crime of theft from the book “Crime and Punishment in Islamic Law: A Fresh Interpretation” by Mohammad Hashim Kamali, published in 2019 by Oxford University Press. The author analyzes the current Islamic discourse on Islamic sanctions and how it relates to the Islamic concept of repentance. As he advocates for “non-literal” and “rationalist” (Bennett, 2022) interpretations to make Islamic law compatible with pluralism, the search hit is classified as Islamic (liberal). Search result number 15 is another Q&A from the Saudi website Islamqa.info. An anonymous user asks if he needs to report people stealing in his company—the anonymous scholar affirms the question but argues that, according to an authentic hadith, it would be even better to stop the theft by intervening directly if possible. The content does not touch the question of the validity of the amputation punishment, thereby rendering the categorization of the text difficult. However, as the text refers to other positions typical for conservative interpretations of Islam such as the banning of polytheism and disbelief, the search hit is classified as conservative.

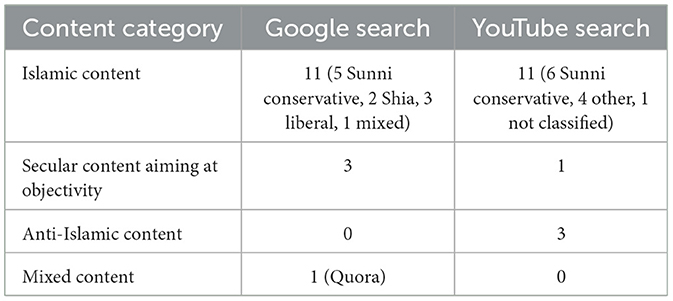

The search results for “Islam Theft” differ from those on apostasy. While secular content was dominating the Google search results on the renunciation of Islam, it is scarcely present (3 results) when searching for content on the Islamic commandment on theft. Instead, users get results leading to mostly Sunni conservative or Shia content – seven analyzed texts defend the legitimacy of the punishment of amputation in general. Yet, three results lead to liberal (in one case Quranist) content questioning the application of the commandment taken from a literal reading of Quranic verse 5:38. It has to be noted that the category of conservative Islamic content lumps together a wide spectrum from positions that defend hand amputation outright to other interpretations limiting it to very specific cases.

6.2 “Islam Theft” on YouTube: the partial hegemony of conservative Islamic content

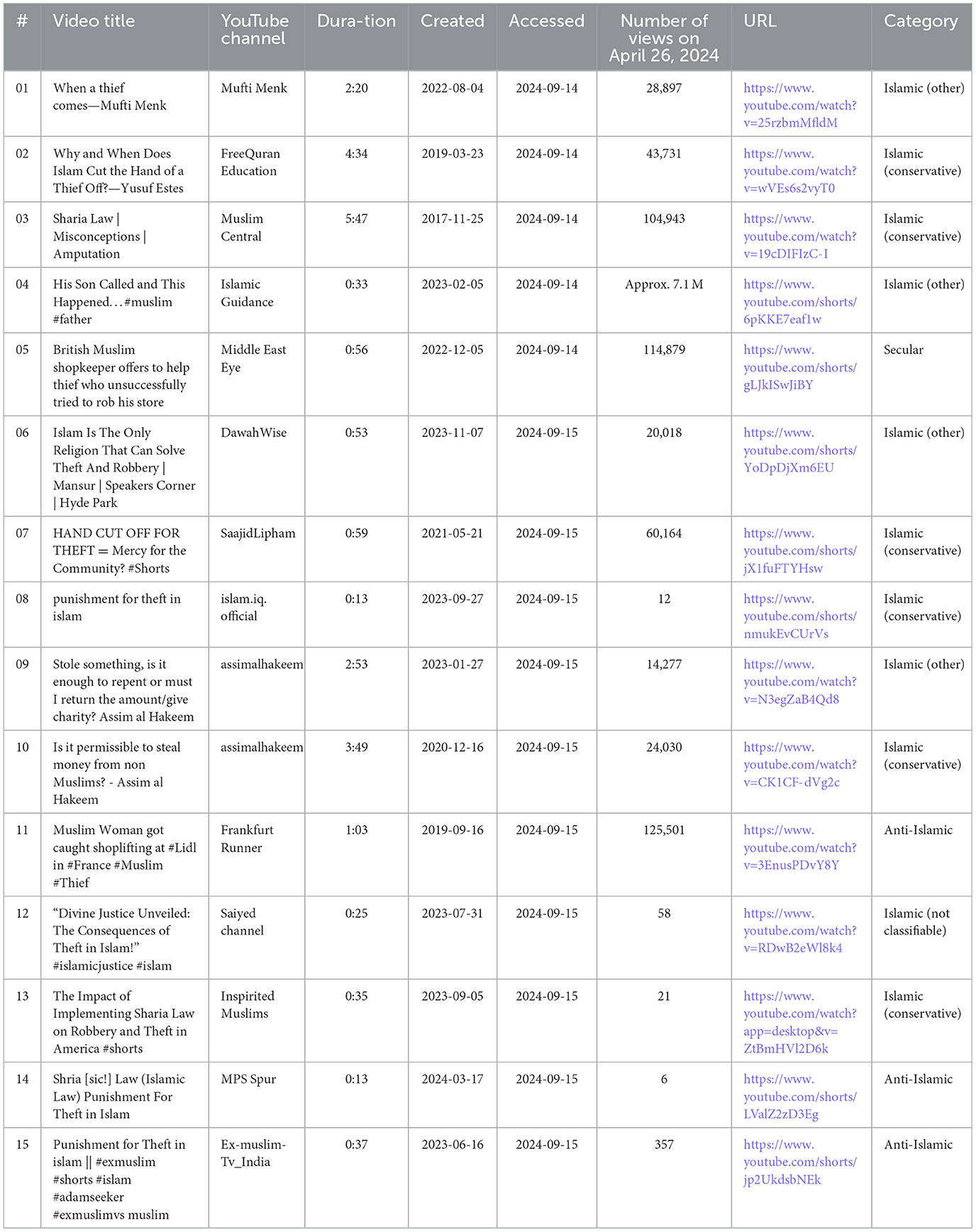

While the writers of the content presented on Google often remain anonymous, the video search results on the topic of Islam and theft are clearly dominated by preachers (see Table 6).

The first clip presented on YouTube is a video by Ismail ibn Musa Menk, Grand Mufti of Zimbabwe, hosted by a Turkey-based YouTube channel that claims in its “bio” to cover Islam-related education and Islamic history, among others. The 2 min clip does not deal with the Islamic commandment on theft at all, but compares the Quran to a guidebook instructing people on how to prevent theft, as the holy book of Islam taught people how to prevent the devil from taking away the chances for an afterlife in paradise. The video was classified as “Islamic (other)” as no viewpoint on specific Islamic rulings was articulated. The second clip provides a justification for the Islamic verdict on theft by the American Muslim preacher Yusuf Estes. The clip is apparently based on an audio recording, accompanied by illustrative animated content that is typical for “FreeQuranEducation”, a YouTube channel provided by an animation studio from Jakarta claiming to be dedicated to educate people about Islam. Estes argues that only people who steal have to be afraid of the punishment. He claims that the condemnation of this sharia sanction would noticeably often be voiced by lawyers and politicians, thereby implying that these two groups of people were often involved in illegal property appropriation. Islam would only call for the punishment to be carried out after the establishment of an Islamic state guaranteeing the necessities of life to everyone. The video is classified as conservative, as the legitimacy of the amputation punishment is upheld. Video number three promises to clarify “misconceptions” about the sharia and amputations. It is hosted by the channel of “Muslim Central”, a South African non-profit organization. A voice accompanied again by animated graphics explains that sharia is wrongly associated by many non-Muslims with cruelty and arbitrary punishment. The speaker points out to the fact that penal law is only a small fraction of sharia. The amputation of the hand could only be legally carried out if more than sixty conditions that ensure that no one that steals out of hunger or under pressure of others is punished by hand amputation. The speaker of the clip further argues that the comparably low homicide rate of Saudi Arabia would prove that the application of sharia penal law would ensure deterrence so that major crimes hardly occur, therefore making the application of that punishment rare. The clip advocates for the amputation punishment for theft and is therefore classified here as conservative, even though the legitimacy of the punishment is limited to very specific cases.

The fourth video is a YouTube short by the Canadian channel “islamic_guidance”. It shows an Islamic dāci12 being called by his toddler child during lecture. The video, classified as “other”, is unrelated to the Islamic ruling on theft and an example of Islamic channels employing purely entertaining videos next to religious lectures to attract more viewers. Clip number five (secular) is another short, posted by the British news outlet “Middle East Eye”, showing a CCTV video of an attempted theft from a mobile phone shop run by a Muslim. The thief fails to steal because the shop's door is locked. At the end of the clip, an Instagram message of the shop owner is shown, offering to help the thief in case he lacks funds for food, citing a hadith calling for Muslims to show mercy and forgive others. The video is not related to the Islamic ruling on theft.

The sixth video is another short, hosted by the British YouTube channel “DawahWise” by two individuals named “Hashim” and “Mansur” that post videos taken at London's “Speaker's Corner”. In the video, Mansur is explaining that in the early years of Islam, jewelry shop keepers went to the mosque for prayer with their gold kept unlocked and unguarded because piety had virtually eradicated theft. The video does not explicitly refer to the ruling on theft and is therefore classified as “other” in this study (although it is possible that Mansur believes that the virtual eradication of theft in the classic age of Islam was due to the strict punishment). Clip number seven is a short posted by Saajid Lipham, introducing himself in his channel's “bio” as an “American Muslim convert” and a graduate of the Islamic University of Medina. Lipham is shown preaching in public, arguing that contrary to common assumption, theft is often not punished by amputation in Islamic law, as minors, as well as the hungry, mentally ill and others are spared from the sentence. His content is classified as conservative since he argues that in some cases, it is needed as a deterrent that he sees lacking in the United States suffering from a high crime rate. The eighth clip is a short hosted by the channel “islam.iq.official”, claiming in its “bio” to spread “authentic content” rooted in Quran and Sunna. Many videos are short quizzes. The analyzed clip asks users whether the Islamic punishment for theft is a fine, imprisonment or the “cutting of hand”. After some seconds, the answer “cutting of hand” is revealed, thereby confirming it in principle as the correct ruling. Therefore, the clip was classified as conservative. The clip is illustrated by a black-and white animated picture of a sea with a mosque in the background and accompanied by the sound of surf, creating a subtly eerie atmosphere.

Video number nine is another clip by the Saudi cleric Assim al-Hakeem, seemingly an excerpt from a call-in show. A female asks if it is sufficient in Islam to repent the act of stealing or if a compensation is necessary. She explicitly refers to the theft of an item, classified as “haram”, i.e., religiously illegitimate—but al-Hakeem seems to miss that word. He replies that it is necessary to return the item or its value in order to repent. Only if a return is impossible, an equivalent donation to charity is possible to avoid the punishment in afterlife. As the video offers no interpretation on the Islamic punishment for theft and no other statement specific for conservative interpretations of Islam, for the purpose of this study, it was classified as “other” despite the fact that al-Hakeem takes conservative positions in other cases. He is also the speaker in the tenth clip. He reads a question from an unknown individual inquiring about the legality to steal from non-Muslims. Al-Hakeem clarifies that neither the life nor the property of the non-Muslim can be taken. He claims such misconceptions are spread in non-Muslim countries because their governments would block access to authentic Islamic knowledge based on Quran and Sunna, instead fighting Islam and preventing Islamic practices like the wearing of niqāb and hijab or the segregation of sexes, thereby promoting ignorance among Muslims. The only non-Muslims whose life and property may be rightfully taken, al-Hakeem claims, is a “ḥarbi” who he defines as someone “belonging to a country that is fighting us [Muslims]”. However, as he implicitly declares all Islamic content circulating in “non-Muslim countries” (0:18) to be inauthentic and implicitly promotes gender segregation, the video is classified as conservative. Clip eleven (anti-Islamic) shows two hijab-wearing women caught stealing by a guard in a supermarket, emptying their clothes from many grocery items illegally taken. The video might be intended to support the claim that Muslims are often involved in crime and that veiled women might use their clothes to hide stolen items.

Videos 12–15 are all YouTube shorts. Clip number 12 is a Hindi-language video by an Indian dāci that could not be analyzed by the author due to the language barrier. Video number 13 (conservative), published by the channel “Inspirited Muslims” claiming in its “bio” to spread the “message of Islam”, shows a short excerpt from a longer speech of Indian preacher Zakir Naik. He claims that people condemn Islam for being barbaric because of the punishment of amputation. However, people denouncing this punishment should answer the question what would happen to the rate of theft and robbery in the United States if sharia was fully applied there, leading both to the implementation of the amputation punishment and the deduction of 2.5 percent in a lunar year of the total savings of all rich persons as zakat (the Islamic charity tax) to support the needy. Naik seems to suggest that these measures would be a viable solution to combat these crimes. Video number 14 (anti-Islamic) is a snippet from a news broadcast of unknown origin reporting on a conviction for theft by a sharia court in Somalia, with the convict(s) facing the punishment of hand and leg amputation. The obscure YouTube channel seems to spread a mixture of anti-Catholic and anti-Muslim content as well as entertaining videos. Video 15 is another Hindi-language clip by an ex-Muslim, with a recitation of Quranic verse 5:38 and a graphic animation of the punishment of hand amputation that could not be analyzed due to the language barrier. The context makes it likely that the YouTuber intends to denounce the Islamic sentence. Therefore, the clip was classified as anti-Islamic.

The YouTube results show a strong presence of conservative preachers even more pronounced than among the retrieved content on apostasy. In five videos, the legitimacy of the amputation punishment is defended, while five other videos do not deal with the Islamic punishment on theft directly, and one video could not be categorized due to the language barrier. While the search for content on apostasy showed one video taking a liberal Muslim perspective on the subject (and another one with a liberal viewpoint, yet unrelated to the topic of apostasy), a liberal Muslim perspective on the commandment of theft was completely missing among the retrieved videos, as well as Shia content. Interestingly enough, anti-Islamic content was also present, yet not as prominent as it is when searching for “ridda” (i.e. apostasy). YouTube seems to be well fitted for polemical battles between antagonistic positions. A look at the number of views of the videos reveals that the spread between the most popular clip and the least popular one is even larger than among the previous YouTube search query: Video number 4—showing a preacher receiving a call from his toddler son—was seen more than 7.1 million times, the second most popular video 11—the anti-Islamic depiction of a stealing veiled woman—far behind with 125,501 views. Funny, short content seems to get a lot more attention than other content, surpassing even polemical anti-Islamic content by far. The least popular clip 14 (an obscure anti-Islamic video) was only watched 6 times. The fact that some videos displayed have hardly been watched might indicate that they are possibly not displayed to many other users entering similar search queries. Therefore, the retrieved results cannot be taken as being representative for all internet users searching for content on the Islamic ruling on theft.

7 Conclusion

Muslims who set out in search of interpretations of Islamic norms that claim authority are confronted today with a wide variety of Islamic claims to authority. In addition, there are secular, Islam-related claims to interpret the norms of Islam truthfully from a non-religious perspective. This diversity is expressed, for example, in the heterogeneous landscape of mosques that has developed in liberal democracies, in which different communities adhere to sometimes contradictory interpretations of Islam. On the internet in particular, users are confronted with an overwhelming variety of interpretations of Islamic norms. The coexistence of different Internet content, which becomes visible through search queries on search engines and social media platforms, creates competition between different, divergent authority claims. This listing of different websites and other content such as videos creates comparability.

The competition between different interpretations of Islamic norms claiming authority can be described as a religion-related market. On YouTube in particular, the various interpretations can be compared according to criteria such as number of views and video length, which are far removed from traditional evaluative criteria for the interpretation of Islamic commandments. The results showed that both anti-Islamic as well as humorous videos get more views than other clips—this might be due both to the interests of internet users and amplification of these videos by the algorithms employed by YouTube.

However, it can be assumed that pious Muslims in particular will specifically visit websites they expect to offer an interpretation of Islamic norms that corresponds to their beliefs and which discuss detailed questions of Islamic law. Nevertheless, Muslims are also likely to take note of the coexistence of various Islamic and non-Islamic interpretations of norms in the wide space of the Internet and allow themselves to be indirectly influenced by them (just as many non-Muslims are likely to receive the interpretations of norms by Muslim actors out of sheer curiosity).

Regarding the research question on the dominant type of norm interpretation, it can be concluded that neither Islamic conservative perspectives nor secular videos or any other type of interpretation prevails unchallenged. The wide variety of interpretations of the most diverse Islamic commandments by the most diverse actors (secular and Muslim, including followers of a rigid Sunni Islam as well as a liberal interpretation of Islam) ensures that divergent interpretations are always just a few clicks away. This could be shown by the content found on Google and YouTube when searching on the Islamic ruling on apostasy: While lots of content tried to challenge the validity from a secular view infused with Islamic scripture-based reasoning, an article defending Islam's right to punish apostasy was also found, as well as Atheist content (on YouTube) denouncing the validity of Islam and its contents altogether. The search results for content on Google and YouTube on the Islamic ruling on theft showed indeed a prominence of conservative Muslim positions defending the legitimacy of the punishment of amputation which is incompatible with the principles of liberal democracy. However, the liberal Muslim position renouncing the punishment was also present, as well as anti-Muslim videos. The expectation of the dominance on YouTube of rigid conservative interpretations by preachers did not hold for the content on apostasy as anti-Islamic polemicists prevail in the field. Yet, the dominance of the conservative Islamic perspective could partially be confirmed for the videos on theft. Here, conservative Muslim preachers are able to successfully draw on the oral tradition of Islamic authority, while secular, non-Muslim voices are in a disadvantage. Yet, in this study, the category of conservative Islamic content included a wide range of Sunni positions reaching from mainstream to Salafi positions. Sometimes, executions for apostasy and the cutting of the hand for theft were defended outright, while in other texts and videos, the application of these punishments was limited to very specific cases. A future study could dive deeper into the variance within the field of conservative interpretations.

This article provided a glimpse into the increasing pluralization of Islam-related claims to authority and showed how the competition between different interpretations of norms constitutes religion-related markets. This was done using the examples of the (mostly) English language micro markets for the interpretation of the Islamic ruling on apostasy and theft, using the search queries on Google and YouTube. Further research is needed to investigate how other controversial Islamic rulings like the punishment for extramarital intercourse are discussed online and to examine the reception and the question how Muslim (and non-Muslim) internet users deal with the coexistence of competing interpretations of Islamic norms on the internet. In particular, it might be useful to design a comparative study examining the reception of search results on apostasy and theft by Muslim internet users in several European countries to investigate a possible effect of the national regimes of relations between religion and state that either put Islamic institution on an equal footing with other religious players or discriminate against them, and which may or may not leave room for the teaching of Islam-related knowledge in public schools. Fenella Fleischmann and Karen Phalet have argued that an “institutional accommodation” of Islam might have a “moderating role” (Fleischmann Phalet, 2011, p. 118). It might serve as a possible explanation why second-generation Muslims of Turkish descent in Berlin who succeed in the educational system tend to be less religious, while no connection between religiosity and educational achievement could be found in Amsterdam, Brussels and Stockholm. In those cities, less legal discrimination against Islamic institutions exist than in Germany, where pious Muslims might be discouraged from succeeding in public schools. Although Fleischmann found no support for “reactive religiosity” or the idea that second-generation Muslims would become more religious in reaction to perceived discrimination by the majority (Fleischmann Phalet, 2011, p. 99–118), it is possible that in countries where there is more discrimination against Muslims and Islamic institutions, Muslim internet users are more inclined to search for and adapt conservative interpretations of Islamic norms online in order to defy a state that is seen as more or less hostile toward their religion. Governments that enact laws to oppose orthodox Islamic norms like veiling for women might even strengthen the effects—here, the case of France might be of particular interest (Korteweg and Yurdakul, 2021).