- Faculty of Law, University of Győr, Gyor, Hungary

The Government has declared a state of emergency for the whole territory of Hungary for a period of 210 days from 1 November 2022 in view of the armed conflict and humanitarian disaster in Ukraine and to avert and manage the consequences of such conflicts in Hungary. Under the rules of emergency legislation, the Government is thus once again in a constitutional position to suspend the application of certain laws, derogate from statutory provisions and take other extraordinary measures. On the basis of this authorization, Government Decree 3/2023 (I. 12.) on the different application of certain provisions concerning the execution of sentences during a state of emergency was adopted at the beginning of the year, according to which, upon the request of a non-Hungarian convict, the national commander of the penitentiary system shall suspend the execution of the sentence until the transfer of the sentence, provided that certain conditions are met and there are no grounds for exclusion. Based on a detailed analysis of the legislation, it can be concluded that in practice this may also mean the remission of the remaining part of the sentence, since the receiving foreign state must ensure the enforcement of the sentence under Hungarian rules, but it is questionable whether this will be done. This outcome, however, runs counter to the fundamental principle of criminal justice, the principle of proportionate punishment, as it discriminates between offenders based on nationality. How compatible is this solution with the fundamental principles of the rule of law, such as non-discrimination or the principle of the obligation to be punished?

1 Introduction

Value is the most abstract scientific category in philosophy and other social sciences, such as law and political science, yet it is very much part of our everyday lives.1 What is the value of criminalization?—the question may arise, since criminalization itself always implies a kind of value selection, value commitment. From the point of view of values, traditional criminal policy can be regarded as unchanging, since the range of values it protects is historically constant. In contrast, changing views on criminal policy follow or reflect the moral, political and historical changes in society.2 How specific can criminal policy be in times of emergency? What is the risk of misuse of emergency legislation?3

The Government has declared a state of emergency for the whole territory of Hungary for a period of 210 days from 1 November 2022 in view of the armed conflict and humanitarian disaster in Ukraine and to avert and manage the consequences of such conflicts in Hungary. Under the rules of emergency legislation, the Government is thus once again in a constitutional position to suspend the application of certain laws, derogate from statutory provisions and take other extraordinary measures. On the basis of this authorization, Government Decree 3/2023 (I. 12.) on the different application of certain provisions concerning the execution of sentences during a state of emergency was issued at the beginning of the year, according to which, upon the request of a non-Hungarian convict, the national commander of the penitentiary system shall suspend the execution of the sentence until the transfer of the sentence, provided that certain conditions are met and there are no grounds for exclusion. What exactly does this provision mean? Can prison doors be opened on the grounds of danger?

2 Emergency legislation in Hungary

The Ninth Amendment to the Constitution of Hungary4 is a milestone in the regulation of the special legal order, as it fundamentally redrew the system of the Constitution with effect from 1 November 2022. 5 The scope of the special legal order has been narrowed down to three categories (state of war, state of emergency and state of danger),6 in which cases the Government has extraordinary legislative powers: it can issue decrees to suspend the application of certain laws, derogate from legal provisions and take other extraordinary measures, as specified in a cardinal law. 7

The pivotal law referred to is Act XCIII of 2021 on the Coordination of Defense and Security Activities, which stipulates that in such cases the Government may suspend the application of certain laws, derogate from legal provisions and take other extraordinary measures by decree in order to guarantee the safety of life, health, persons, property and legal security of citizens and the stability of the national economy. The Government may, however, exercise this power in a very broad and general list of cases, as set out in the Act.

(a) Relating to personal liberty and living conditions,

(b) In the context of economic and supply security,

(c) Relating to restrictions for security purposes affecting communities and to the provision of information to the public,

(d) Relating to the operation of the state and local government,

(e) Relating to the maintenance or restoration of law and order and public security,

(f) Relating to national defense and the movement of persons,

(g) In other regulatory matters not covered by the foregoing points, directly related to the prevention, management, liquidation, and prevention or remedying of the harmful effects of an event giving rise to a state of war, state of emergency or emergency.8

In the exercise of its powers, the constitutional principles of necessity, proportionality and purpose must be considered: the Government may exercise these powers, to the extent necessary and proportionate to the objective to be achieved, in order to prevent, manage, eliminate and prevent or remedy the harmful effects of the event giving rise to the state of war, state of emergency or emergency. In the case of regulation relating to personal freedom and living conditions, the law imposes an additional condition, namely that the Government may exercise its powers, without prejudice to the above, only in connection with the introduction of measures which are necessary and proportionate to the threat to be dealt with to respond immediately.9

In a special legal order, to achieve the above objectives, fundamental rights may be restricted only to the extent strictly necessary and proportionate to the objective pursued, in relation to the event giving rise to the special legal order. Suspension of fundamental rights may occur if the above restrictions are not sufficient for the purpose and the prevention, management, elimination, prevention or remedying of the event giving rise to the special legal order cannot be guaranteed by other means.10 These requirements relating to the restriction or suspension of fundamental rights may not be derogated from. The Government shall ensure that these requirements are always complied with, and if the conditions for restriction or suspension are no longer met, the Government shall immediately ensure that the restriction or suspension of the fundamental right is lifted.11

How unique is this Hungarian regulation?12 The answer to this question does not necessarily require us to dig into the depths of individual national regulations, as the appropriate mandate can be found within the Council of Europe.13

In the context of Article 15 of the Convention, the following logical basis for State discretion can be established. The text proposes an objective interpretation both justification for the derogation and of the appropriateness of the measures taken, the principles of democracy, subsidiarity and proportionality providing a concrete instrument for State discretion. A real threat presents democratic authorities with an honest dilemma, in which they must choose between fulfilling their obligations under the Convention and exercising the rights allowed by Article 15, the latter being derogated from if circumstances permit. Assessing whether these circumstances arise is generally not easy and may involve balancing conflicting public interests on the one hand, and order and stability on the other. The Convention cannot be interpreted as meaning that the rights it enshrines must be upheld even if this would jeopardize the unity of a given national democracy by limiting the state’s ability to deal effectively with disorder. A given emergency can bring a range of proportional responses, from which it is not easy to choose. But this choice should be left to the national authorities, for three reasons. First, they are closer to the fire and therefore theoretically in a better position to make the right decision. Second, the choice is inherently political rather than judicial and can be highly contentious. Third, different responses can be justified for different emergencies in different states. The key moment in the assessment of the instrument of state discretion lies in the credibility of the evidence that the democratic unity of the state in question is openly threatened and cannot be defended without extraordinary measures.14 We can see that there is then a clear justification for state discretion, which is why a higher level of implementation of the principle of democracy is required in these cases.15

3 The Hungarian government’s decision on foreign criminals

In times of crisis, any political system gives the executive an exceptional mandate, since it is not possible to face new and rapidly changing challenges within the framework of existing laws.16 However, the first key question in relation to the declaration of an emergency is always whether it is necessary to declare it at all, or whether, once declared, the legislation made with reference to it is necessary (directly causally linked) to crisis management.17

Under the emergency clause of the Constitution, the Government may declare a state of emergency in the event of an armed conflict, war or humanitarian disaster in a neighboring country, or in the event of a serious incident threatening the safety of life and property, in particular a natural disaster or industrial accident, and in order to avert the consequences thereof.18 This happened in the autumn of 2022, in view of the armed conflict and humanitarian disaster in Ukraine, and in order to avert and manage the consequences of these in Hungary, the Government Decree 424/2022 (X. 28.) on the declaration of a state of emergency and certain emergency rules declared a state of emergency for the entire territory of Hungary.19 The Regulation entered into force on 1 November 2022 and will expire on 20 November 2024,20 therefore maintains the exceptional regime for 2 years.21 Emergency measures in relation to emergencies are provided for in separate government decrees.22

The latter enabling provision brings us to Government Decree 3/2023 (I. 12.) on the different application of certain provisions concerning the execution of sentences during emergency situations, which is relevant to our topic and will be analyzed in detail.23 During a state of emergency, the Government Decree provides for the different application of certain provisions concerning the execution of sentences, according to which, at the request of a non-Hungarian convict, the national commander of the penitentiary system shall, if certain conditions are met or there are no grounds for exclusion, suspend the execution of the sentence and the Hungarian State shall transfer the execution to the other State indicated by the offender in his request.24 What is this special provision? Does the State waive its legitimate criminal right to punish the offender, i.e., does it “let the offender go”?

The legislation is summarized below:

Under the Government Decree, an interruption may be made if.

(a) The Minister responsible for justice declares that the transfer of the enforcement of the custodial sentence is not excluded;

(b) On the basis of a preliminary opinion of the National Directorate General for Aliens, the expulsion of a foreign prisoner subject to expulsion or, in the case of a foreign prisoner not subject to expulsion, the expulsion of a foreign prisoner subject to expulsion may be ordered and its enforceability is not excluded;

(c) The return of a foreign national not subject to the above rule to the State in which the custodial sentence was transferred is guaranteed;

(d) The foreign prisoner undertakes to leave the territory of Hungary after the suspension of the enforcement of the custodial sentence, to cooperate with the authorities to this end and to submit to the aliens’ proceedings against him, to return to the State concerned by the transfer of the custodial sentence and not to return to the territory of Hungary before the enforcement of the custodial sentence is completed or its enforceability has ceased or during the period of expulsion or, if an aliens’ expulsion order is issued, during the period of the prohibition on entry and residence;

(e) The foreign prisoner consents to the enforcement of the custodial sentence in another State;

(f) The grounds for exclusion provided for in the Regulation do not apply.25

The enforcement of a custodial sentence may not be interrupted if.

(a) A further custodial sentence is to be served for which the statutory conditions are not fulfilled,

(b) Criminal proceedings are pending against the foreign prisoner in the territory of hungary,

(c) The authorized interruption of the enforcement of the custodial sentence has been terminated earlier due to the foreign convict’s misconduct,

(d) It cannot be ensured that the interruption of the enforcement of the custodial sentence is carried out in such a way that the remaining part of the custodial sentence is the shortest possible period of the custodial sentence that can be handed down,

(e) There are 5 years or more remaining on the term of imprisonment,

(f) The foreign convict has been sentenced to life imprisonment,

(g) The foreign national has been sentenced to a term of imprisonment to be carried out for offences defined in the Regulation (e.g., crimes against humanity or against peace, war crimes, crimes against the State, terrorist offences, seizure of a vehicle or a vehicle for the transport of aircraft, rail, water, road, public transport or goods, capital offences).26

The foreign prisoner may submit his application for the suspension of the enforcement of the sentence in the penitentiary institution. In his application, he must state the State in respect of which he consents to the transfer of the custodial sentence and his personal circumstances in relation to the State he has indicated, in particular the grounds for his right of residence there, the documentary evidence of his right of residence and the means of securing his return to the country in which the custodial sentence is to be transferred.27

The prison institute forwards the foreign prisoner’s application to the national commander. On receipt, the national commander first checks whether there are any grounds for exclusion and, if there are none, sends the foreign national’s application to the Minister, the competent prison judge and the Directorate-General.28 The Minister shall declare within 30 days of receipt of the request whether the transfer of the enforcement of the custodial sentence is excluded, and shall indicate the shortest period of custodial sentence that may be transferred in the case of a foreign prisoner if the transfer of the enforcement of the custodial sentence is not excluded.29 Within 30 days of receipt of the request, the enforcement judge shall inform the foreign prisoner of the place of residence in the other State, of the personal circumstances of the foreign prisoner which justify the transfer of enforcement, in particular the legal basis and documentary evidence of his right of residence in the State in which enforcement of the sentence is transferred, and of the means of ensuring his return to the State in which enforcement of the sentence is transferred. The judge shall send the record of the hearing to the national commander.30 On receipt of the request, the Directorate-General will give a preliminary opinion on the enforceability of the expulsion or, if an expulsion order is necessary, on the enforceability of the expulsion order.31

Within 3 days of receiving the report of the hearing of the foreign prisoner, the Minister’s statement and the opinion of the Directorate-General, the national commander decides to suspend the sentence.32 The convicted person and the prosecution can file a judicial review against the decision.33

From the point of view of our topic, the main question is in which cases it is possible for a prisoner—in most cases arrested during the proceedings and then serving a custodial sentence—to be released.

Reading the legislation, it seems at first glance that the fate of the convicted person depends on whether he or she is subject to expulsion34 or deportation.35 If yes, he or she will be handed over by the penitentiary to the police on the day of the start of the expulsion to be accompanied by the authorities, and if no, he or she will be released by the penitentiary.36 But this is not the case in practice.

Previously, the decision of a court, immigration authority or asylum authority ordering deportation had to be enforced by an official escort (deportation) in several cases, but in the case of prisoners in detention, this is now only required, following a later legislative amendment, if the control of their departure is necessary for national security, the enforcement of an international treaty obligation, or the protection of public safety or public order. Based on this, the authority is free to decide whether to deport the prisoner, and if it does not consider it justified, to release him. The practice is definitely in the latter direction.37 In this case, however, it is strangely up to the prison to decide when the conditions of release can be secured, when the prisoner is “put out on the street.” Could he be in for another week if he cannot prove that the conditions of release are not assured?38 How does this fit in with the guarantees of the rule of law?

In some cases of expulsion and deportation by immigration authorities, the prisoner would therefore be under official escort, which would optimally cease when the enforcement of his or her custodial sentence is taken over by another State.39 In practice, however, this is not the case. On the one hand, we have seen that, under the Government Decree, an interruption is possible, inter alia, if the Minister of Justice declares that the transfer of the execution of the custodial sentence is not excluded. However, for a significant proportion of the offenders concerned by the legislation, the basic offence of smuggling of human beings (e.g., taking a single person across the border for the first time in his or her life without consideration) is not punishable in Austria or Germany, so that the punishment of offenders who often come from these countries cannot be interrupted. On the other hand, even in the case of deportation under the Government Decree, the other state does not physically take charge of the detainee, nor does it wait for him on the other side of the border, unless he is also under criminal investigation in that country. The Hungarian authorities will escort him to the border where he will be released. Of course, the Minister of Justice sends the information to the ministry of the country of destination, but at the moment it is a big question whether the remaining sentence will be executed there.40

Following the legislation in January 2023, there was a substantial change in April. Based on the procedure for emergency legislation detailed above, the Government adopted Government Decree 148/2023 (27 April 2023) on the reintegration detention of persons convicted of the crime of smuggling of human beings. Under the new rule, if the court has imposed a custodial sentence for the crime of smuggling or preparation of smuggling and has also ordered the expulsion of the convicted person, provided that the convicted person is not under criminal proceedings for any other offence in Hungary, or he is not serving a further custodial sentence for which the above conditions are not met and has not yet been placed under a reintegration detention order, the remaining period of the custodial sentence imposed on the sentenced person after his release from the penitentiary shall be converted into a reintegration detention order.41 In practice, this means that the offender has to leave Hungary within 72 h, as the place of execution of the reintegration detention is the territory of the state of the former habitual residence of the sentenced person before Hungary or, if this is not known, the state of his nationality.42 It is clear from this rule alone that this reintegration detention has the least to do with these two words: on the one hand, it is not reintegration, since there is no intention of integration; on the other hand, it is not detention, since we are releasing prisoners. In practice, therefore, it is a simple amnesty to reduce the prison population.43

4 Conclusion

Criminal justice is the exercise of the criminal power of the State, and the application of substantive criminal law involves the determination of the offence and the imposition of a penalty. A criminal sanction is a punishment, a penalty. Legitimate punishment has a symbolic function: criminal orders cannot be violated with impunity, even if there is a reason to do so.44 Does Hungary comply with this legal principle? Or can the offender escape?

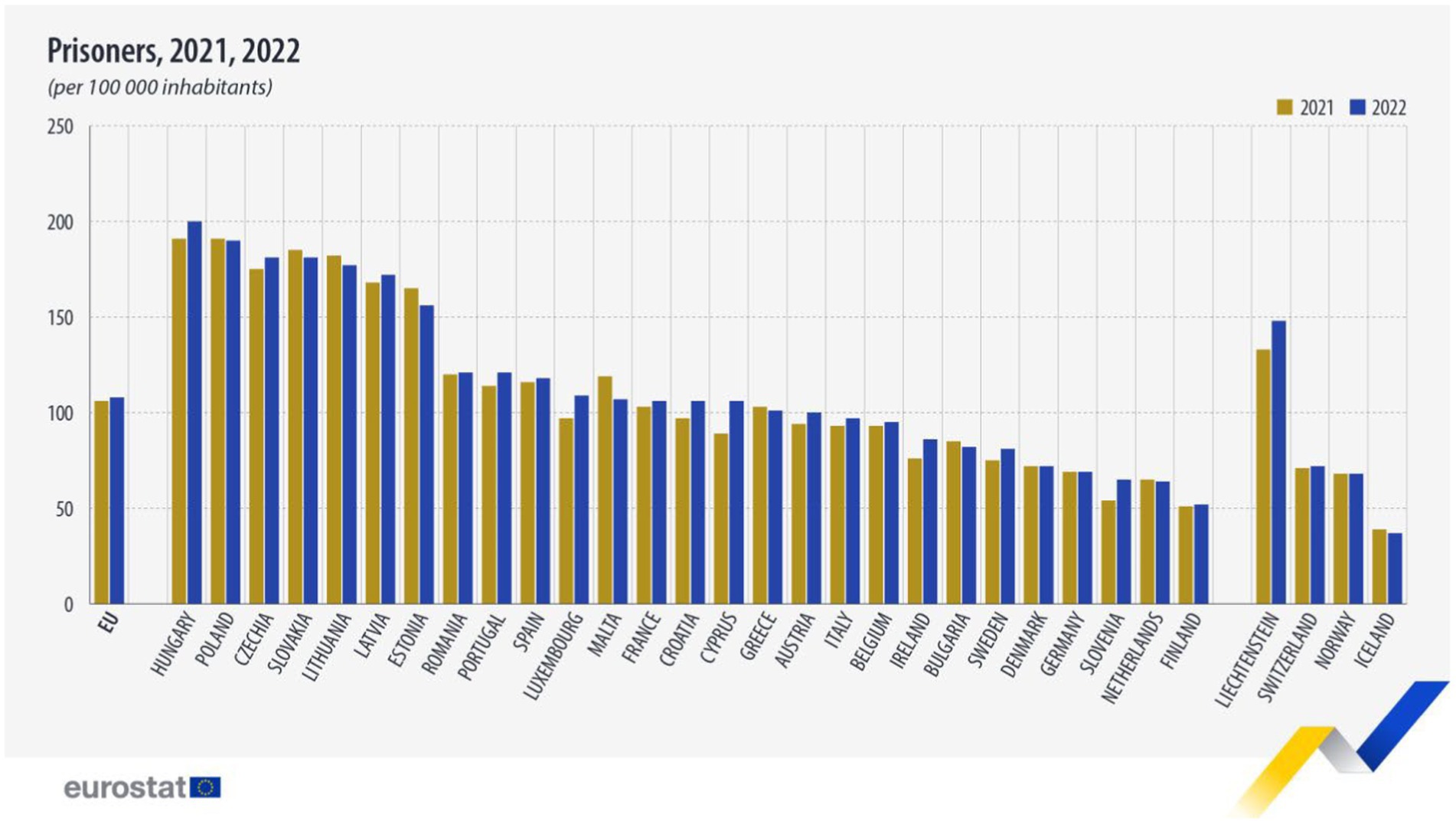

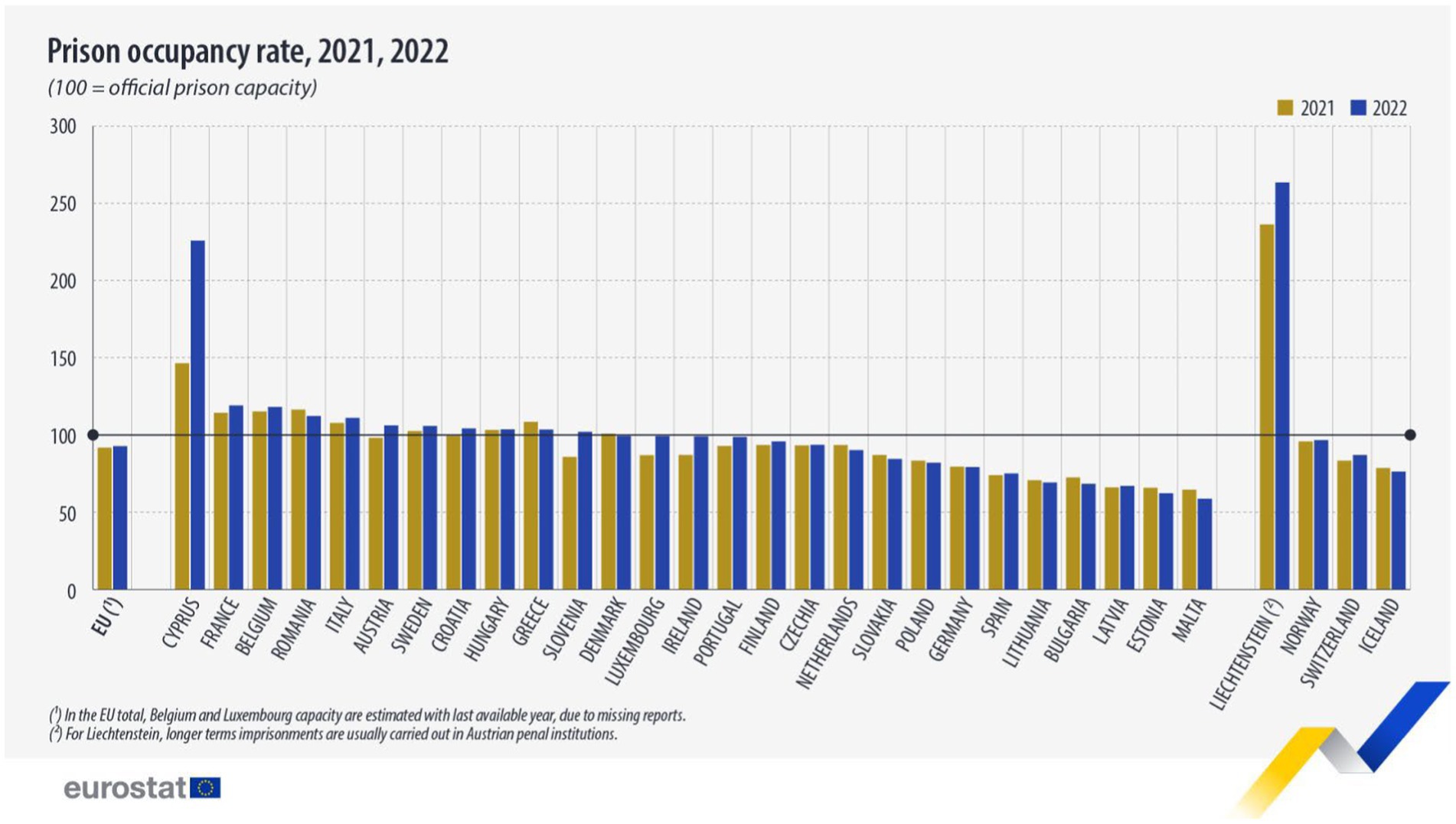

A detailed analysis of the legislation shows that, on the one hand, the Government Decree allows for the release of the sentenced person, and that the practice so far has made this a general rule. On the other hand, the interruption may also mean the remission of the remaining part of the sentence, since the receiving foreign state must ensure the execution of the sentence under Hungarian rules, but it is questionable whether it will do so under its own law. But this outcome goes against the fundamental principle of criminal justice, the principle of proportionate punishment,45 as it discriminates between offenders based on nationality. There can be neither retribution nor deterrence, since the sin committed thus remains essentially unpunished. What, then, is the legal policy rationale for the legislation? (Figures 1, 2)

The prison population has swollen enormously in recent years, almost topping 20,000, a level not seen since the change of regime. The Eurostat tables above clearly show that Hungarian prisons are over 100% full, with the country having the highest number of people in prison as a proportion of its population. At the same time, the armed conflict on the territory of Ukraine poses the risk that armed persons from the neighboring state may “stray” to commit crimes, in which case they would of course have to be “accommodated” in prisons. We need to improve the indicators, so we need the space, and it is advisable that it is not occupied by foreign people smugglers, for whom one of the main aims of the penitentiary system, reintegration and rehabilitation into society, is practically impossible, as the Hungarian state does not envisage their future in our country.

The legislator envisages that up to half (later estimated at a quarter) of the convicts concerned could leave the country thanks to the new legislation, and the case law of the time that has passed shows that the introduction of reintegration detention for people smuggling convicts is producing the expected results. The question is, however, at what price? To what extent is the legislative objective achieved by means of the rule of law? As an old Hungarian song goes: ‘one man succeeds, another man fails’. If two members of a criminal organization of different nationalities are convicted of smuggling people, the Hungarian convict must serve his sentence, while the foreign national does not. This, although legal under the current legislation, is not fair.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PV: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Bihari, 2009, p. 3.

2. ^Németh, 2013, pp. 361–365.

3. ^Mészáros, 2024, pp. 1–10.

4. ^Ninth Amendment to the Constitution of Hungary (22 December 2020), Article 11.

5. ^Regarding the previously applicable legal framework see: Hungler et al., 2021, pp. 4–7; Szente and Gárdos-Orosz, 2022, pp. 156–158.

6. ^Constitution, Article 48.

7. ^Constitution, Article 53(1). The text has been clarified by the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution of Hungary (24 May 2022), Article 1: In Article 53(1) of the Constitution, the words “The Government in the event of an elementary disaster threatening the security of life and property” shall be replaced by “The Government in the event of an armed conflict, war or humanitarian disaster in a neighboring country, and an elementary disaster threatening the security of life and property.” For a detailed analysis of the special legal regime, see. Ungvári and Sabjanics, 2021, pp. 284–287.

8. ^Act XCIII of 2021, § 80 (1)–(2), para.

9. ^Act XCIII of 2021, § 80 (3)–(4), para.

10. ^Act XCIII of 2021, § 81 (1)–(2), para.

11. ^Act XCIII of 2021, § 81 (3). For more details see. Stumpf, 2021, p. 251.

12. ^For a theoretical justification of the special legal order, see. Csink, 2017, pp. 8–10.

13. ^The European Convention on Human Rights’ rules on the protection of democracy, set out in Article 15, allow for the suspension of all rights except absolute rights in the event of “war or other public emergency threatening the life of the nation.” A loophole has thus long been open for States Parties to step aside in the event of a potential threat to violate certain Convention rights.

14. ^United Communist Party of Turkey and others v. Turkey, judgment of 30 October 1998, Reports of Judgments and Decisions, 1998-I, 1, 45. §.

15. ^Greer, 2000, pp. 23–24.

16. ^Stumpf, 2021, p. 248.

17. ^On the need to declare a state of emergency, see. Horváth, 2021, p. 152.

18. ^Constitution, Article 51(1).

19. ^Article 1 of the Government Decree No. 424/2022 (X. 28.) on the declaration of a state of emergency and certain emergency rules in view of the armed conflict or humanitarian disaster in Ukraine and to avert and manage the consequences thereof in Hungary.

20. ^Government Decree 424/2022. (X. 28.) § 4–5.

21. ^It should be noted that the maintenance of a special legal order for many years is not unique in Europe, see. Ságvári, 2017, p. 179.

22. ^Government Decree 424/2022. (X. 28.) § 3 (1).

23. ^Hereinafter: Government Decree.

24. ^The Government Decree thus creates a special case area for the regulation of interruption compared to the Bv. tv., since according to the general rule of law, the execution of imprisonment may be interrupted ex officio or upon request for important reasons, due to the personal or family circumstances of the convicted person or his/her state of health. See Article 116 (1) of Act CCXL of 2013 on the Enforcement of Penal Sanctions, Measures, Certain Coercive Measures and the Imprisonment for Offences (Bv. Act).

25. ^Government Decree § 2 (1).

26. ^Government Decree § 2 (2). It should be noted that the case law has already developed a different jurisprudence in the short time that has passed, interpreting the legal scope of the legislation in a restrictive way. For example, the administrative authority, acting in its discretionary power, will consider as an exclusionary circumstance if a transfer procedure has been initiated before the entry into force of the Regulation, in which case it will not allow the interruption under the new rules. However, the conditional reduction of the custodial sentence - which is not automatic and requires a decision by a bv. judge - is in practice “anticipated” by the authority, which requires the 6 months to be served before that date.

27. ^Government Decree § 3 (1)–(2).

28. ^Government Decree § 3 (3)–(4).

29. ^Government Decree § 4.

30. ^Government Decree § 5 (1) and (3).

31. ^Government Decree § 6 (1).

32. ^Government Decree § 7 (1).

33. ^Government Decree § 8 (1).

34. ^Section 33 (1) (i) of Act C of 2012 on the Criminal Code (hereinafter: Criminal Code) and Sections 59–60 of the Criminal Code.

35. ^Paragraph 43 (2) of Act II of 2007 on the Entry and Residence of Nationals of Third Countries (hereinafter: Harmtv.), which was repealed by the new regulation, Section 98 of Act XC of 2023 on the General Rules for the Entry and Residence of Nationals of Third Countries (hereinafter: Btátv.)

36. ^Government Decree § 9 (1).

37. ^Since the entry into force of the Government Decree, deportations have been ordered in less than 10% of cases in the Western Transdanubian region.

38. ^Paragraph 14 (1) of the Government Decree: expulsion ordered by a court or expulsion by an immigration authority shall be carried out under escort by the authorities if the control of the foreigner’s departure is necessary for the protection of national security, the enforcement of an obligation under an international treaty, or the protection of public security or public order.

39. ^Government Decree § 10 (1).

40. ^Based on current practice, there is no experience in this respect, and feedback should be provided to the Minister of Justice, but there are currently no statistics in this direction.

41. ^§ 1–2 of Government Decree 148/2023 (IV. 27.) on the reintegration detention of persons convicted of the crime of smuggling of human beings.

42. ^Government Regulation No 148/2023 (27.IV.) § 2 (2)–(3).

43. ^For the Hungarian amnesty provisions see. Váczi, 2013, pp. 553–562.

44. ^Constitutional Court Decision 23/1990 (X. 31.) on the unconstitutionality of the death penalty, concurrent opinion of Dr. András Szabó, Constitutional Judge.

45. ^“The principle of proportionate punishment is the only possible constitutional punishment under the rule of law, because it is the only one compatible with the ideal of equality of rights. Any other consideration would be a declaration of inequality of rights.” Cf. the decision of the Constitutional Court 23/1990 (X. 31.) on the unconstitutionality of the death penalty, parallel opinion of Dr. András Szabó, Constitutional Judge.

References

Greer, S. (ed.). (2000). “The margin of appreciation: interpretation and discretion under the European convention on human right” in Human rights files 2000/17 (Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing).

Horváth, Attila (2021). A 2020-as Covid-veszélyhelyzet alkotmányjogi szemmel. In: A különleges jogrend és nemzeti szabályozási modelljei. Ferenc Mádl Comparative Law Institute, Budapest.

Hungler, S., Rácz, L., and Gárdos-Orosz, F. (2021). “Hungary: Legal response to Covid-19,” in The Oxford Compendium of National Legal Responses to Covid-19 (OUP 2021). eds. J. King and O. L. M. Ferraz (Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/law-occ19/e40.013.40

Mészáros, G. (2024). Misuse of emergency powers and its effect on civil society - the case of Hungary. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1360637. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1360637

Németh, I. (2013). “Elmélkedés a büntetendővé nyilvánítás értéktartalmáról” in Tanulmányok a 70 éves Bihari Mihály tiszteletére. ed. S.-K. K.-D. Gergely (Győr: Universitas-Győr Nonprofit Kft).

Ságvári, Á. (2017, 2017). Különleges jogrend a francia jogban. Az állandósult kivételesség. Iustum Aequum Salutare XIII 4, 179–188.

Stumpf, I. (2021). A válságok hatása a politikai rendszerekre. Sci. Securitas 2, 247–256. doi: 10.1556/112.2021.00051

Szente, Z., and Gárdos-Orosz, F. (2022). “Using emergency powers in Hungary: against the pandemic and/or democracy?” in Pandemocracy in Europe: Power, parliaments and people in times of COVID-19 (Oxford: Hart Publishing), 155–178.

Ungvári, Á., and Sabjanics, I. (2021). Pandémia és különleges jogrend Magyarországon. Sci. Securitas 2, 284–291. doi: 10.1556/112.2021.00058

Keywords: extraordinary legal order, execution of the sentence, suspension of execution of the sentence, emergency powers, criminal justice

Citation: Vaczi P (2025) One succeeds and the other fails? Criminal justice in times of emergency. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1511739. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1511739

Edited by:

Fanni Tanács-Mandák, National Public Service University, HungaryReviewed by:

Nóra Balogh-Békesi, Ludovika University of Public Service, HungaryImre Nemeth, Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary

Katerina Frumarova, Palacký University, Olomouc, Czechia

Tomoya Mukai, Fukuyama University, Japan

Copyright © 2025 Vaczi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peter Vaczi, dmFjemkucGV0ZXJAZ2Euc3plLmh1

Peter Vaczi

Peter Vaczi