- Institute for Intercultural and International Studies, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

This article examines how regional organizations (ROs) generate distinct policy ideas through the mobilization of regional knowledge. Although some ROs have gained considerable influence in international politics, their institutional idiosyncrasies largely remain underexplored and undertheorized. The article first intends to clarify the conceptual relationship between regions, regionalism, and regional organizations. Secondly, it proposes a theoretical framework of regional knowledge and knowledge mobilization through ROs. Relying on constructivist and institutionalist notions of international relations, it argues that the ability to draw from both regional and global bodies of knowledge distinguishes ROs from other IOs. The article posits that ROs leverage both regional, context-specific knowledge and global, formalized knowledge, particularly in policy fields where local and regional socio-cultural context is crucial. Regional knowledge thereby fulfills a moderating role in the genesis of regional policy ideas. ROs are thus to be treated as unique social actors which act back against their environments in ways which are often specific to them.

Introduction

International organizations (IOs) have been studied in considerable depth. A lot of their influence in world politics has been attributed to their ability to produce, reproduce and diffuse policy ideas and norms (Barnett and Finnemore, 2004). Other studies point to advantages in data, technical knowledge and expertise as crucial vectors for IO agency (Hawkins and Jacoby, 2006). Thus, IOs display agency by mobilizing knowledge, and by pursuing policy ideas based on this knowledge (Krogmann, 2024). However, the literature has rarely accounted for differences between IOs of varying geographical scopes. There is little reason to believe that the relationship between bureaucratic international institutions, policy ideas and knowledge should be the same for all types of IOs, especially since IOs show variation in their intrinsic features, which moderates their behavior and ability to exert influence (Niemann et al., 2023). This is puzzling because some regional organizations (ROs) have become influential actors in international politics, yet we know little about their institutional idiosyncracies. This article is thus concerned with the distinct policy ideas of ROs and how they are moderated by the mobilization of regional knowledge. Apart from the empirical observation that recent years have seen “more and deeper regionalism” (Börzel, 2016: p. 41) in many regional contexts, scholars have engaged with ROs from different angles. While some argue that the rise of a number of regional organizations may challenge the liberal international order (LIO) which has structured international relations from 1945 onwards by promoting regional “sub-orders” (Kornprobst and Paul, 2021; Lake et al., 2021), others point to the lack of International Relations (IR) theorizing about ROs (Acharya, 2009, 2014). Traditionally, studies on regionalism have focused on the European Union (EU), thereby spawning a host of theories about regional integration (e.g., Moravcsik, 1995). However, while there is a rich and established body of literature on European integration, non-EU regional politics have often been neglected. Studies in comparative regionalism have attempted to fix some of these shortcomings (Panke et al., 2020), but the literature remains fragmented. Similarly, the EU has often been used as benchmark of comparison. Where ROs have been studied outside of Europe, the focus has mostly been on their different institutional designs rather than on their output (e.g., Jetschke et al., 2021; Jetschke and Lenz, 2013). The IR literature is especially lacking comprehensive accounts of region-specific policy ideas. Where such accounts are available, they mostly stem from development studies and are limited to economic ideas (e.g., O'Reilly and Heron, 2023). As knowledge plays such an important role in the formulation of policy ideas in general (Heymann, 2010; Niemann and Martens, 2018), it stands to reason that regional contexts should be no exception. Indeed, what some scholars have referred to as “world-regional […] policy” (Deacon et al., 2010) may critically rely on access to local and regional “knowledges” and issue framings, which has for instance been shown for regional health policy to some extent (Amaya et al., 2015). While processes of regional integration thus remain contested subjects in comparative regionalism, there is little literature on the ideational outcomes of integration. In other words, scholars have been more concerned with how regional institutions come about and how they differ from each other in their institutional designs, rather than with the ideas and norms they produce, and the processes by which they do so. This article takes another approach. Rather than with the determinants of regionalism as an integrative process of institution-building, I am concerned with how the ideational outcomes of such developments depend on different bodies of knowledge. How, then, do regional organizations mobilize knowledge when they produce distinct policy ideas? In answering this question, this article's contribution is mainly theoretical in nature. I intend to illuminate two distinct conceptual relationships between key elements of contemporary politics in today's “world of regions” (Katzenstein, 2019: p. 1). First, and rather briefly, this article separates regions, regional organizations, and regionalism to make them tangible as analytical units. Second, and in greater length, it provides an account of how regional organizations mobilize different bodies of knowledge when pursuing policy ideas. I argue that while the relationship between concepts of region, regionalism, and regional organizations are muddied by the inconsistency of their usage, they can be distinguished from each other in a way that is both comprehensive and analytically useful. I further argue that the same is true for regional knowledge and regional policy ideas, where the former moderates the formulation of the latter in ROs. ROs mobilize both regional, context-dependent and experiential knowledge, as well as global formalized knowledge when formulating policy ideas. The ability to draw from both of these bodies of knowledge distinguishes ROs from other IOs. These contributions are in accord with constructivist IR theory, as constructivism provides the tools to engage with institutions, knowledge and ideas as explanatory variables in international politics.

The article is organized as follows. First, I explore what it means to talk about political regions in the first place, how regional organizations relate to regions, and what constitutes regionalism. I then relate these concepts to constructivist institutionalism, show how regional organizations develop their own policy ideas, and explain how this process is moderated by available regional knowledge. Lastly, I discuss possible theoretical obstacles for such a framework, before drawing a conclusion.

Making sense of political regions—regional organizations and regionalism

This section discusses what it means to talk about “regions” and situates the article within the general debate on regionalism. All three of these concepts—region, regional organization, and regionalism—are related to each other, and it is important to gain conceptual clarity about the specific nature of this relationship here. Regional organizations can be seen as manifestations of political regions, and they represent instances of regionalism.

Regions

The term “region” is employed quite inconsistently in both scientific literature as well as public discourse. At times, it is taken to refer to the sub-national level, as in “the region of Madrid.” This is most common in fields such as business studies or urban planning and development, where a region is a rather well-defined area within a nation state, often times with its own municipal government (Lönnqvist et al., 2014). In this conceptualization, the region has clear boundaries, and there is little debate about where it ends or what it is comprised of.

Other times, “region” refers to groups of nation states, as in “the Southeast Asian region.” It is this latter usage which is the subject of this article, and it is here where the concept becomes slightly more puzzling. Most of this confusion stems from the fact that the composition of a region changes depending on which criteria it is defined by. Geographically, for example, “the Baltics” can be seen as a region comprised of states which border the Baltic Sea, namely Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania. But within and above that same geographical space, multiple other groupings exist which could legitimately be called regions, for instance the region “Europe,” which encompasses all Baltic states. The picture becomes even less clear when political, cultural or otherwise socially constructed criteria of regional belonging are taken into account. Notions such as the EU's “Europe of Regions” and the “European Committee of the Regions” serve to illustrate the elusiveness of the term region. Geography has thus struggled to come to a concise definition of regions, as “there seems to be a consensus that regions are more than just territorial spaces, but it remains difficult […] to grasp that extra-geographical element” (van Langenhove, 2013: p. 474).

In political science as well as IR, most of the attention has been given to the social construction of regions beyond their mere geographical properties, especially to the role of regions in global and local governance (Börzel and Risse, 2016; van Langenhove, 2013). As for political regions, a comprehensive definition is offered by Paasi, according to whom “regions […] are historically contingent social processes that become institutionalized” (Paasi, 2011: p. 10). All three elements of this definition—historicity, social (re-)production and institutionalization are key features of political regions, but it is the creation and continuation of regional institutions where the rather abstract concept of “region-ness” becomes most readily observable.

The institutionalization of regions can take many forms, and encompasses coordination and organization among state actors, private actors and civil society, as well as hybrid forms. ROs fulfill a unique role for regional institutionalization and integration, because they are both agents of and subjects to regional integration (Weiffen et al., 2013). In other words, they can be drivers of regional integration through the mandates granted to them by their member states, but that same process also deepens their scope and capacities, since they offer frameworks for nation states through which to direct integration.

Regional organizations

While regions are somewhat unwieldy as analytical units, regional organizations are much easier to define, observe, analyze and theorize. They have been engaged mostly as distinct empirical phenomena by scholars of regionalism, and often disregarded by international relations theorists in favor of larger global bureaucracies when studying international organizations. However, for a concise definition, the first step is to acknowledge that regional organizations are international organizations. While there are many ways to define IOs, one of the most common definitions is provided by Barnett and Finnemore, according to which IOs are “organizations which have representatives from three or more states supporting a permanent secretariat to perform ongoing tasks related to a common purpose” (Barnett and Finnemore, 2004: p. 177).

Regional organizations, then, are IOs which somehow relate to regions. One dimension of this relationship is membership. Regional organizations are typically comprised of states in geographical proximity to each other, which therefore share incentives for cooperation in matters concerning what they perceive as their region. Another dimension is the external representation of the region. Regional organizations often represent their member states in international negotiations with third parties, such as other IOs, when it is beneficial for them to “speak with one voice.” For example, in the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), officials have often acted on behalf of Caribbean states in multilateral negotiations in different policy fields. A third important dimension is the regional scope of activities. While some ROs, especially the EU, extend their reach beyond their home region through funding and policy advice on a more global level in many policy fields, ROs will generally focus their policies on the region that they are situated in, because that is where their primary mandate stems from. ROs are therefore partly defined by their actions—ROs are IOs which engage in region-building or regionalism in some form or another. Regional organizations, then, “are formal and institutionalized cooperative relations among states […] and constitute regionalism” (Börzel and Risse, 2016: 7). By extension, when regional ideas are mentioned in the following sections, they refer to the policy ideas held by and within regional organizations.

If regional organizations are but one type of international organization, why should they be studied as distinct empirical phenomena? A first step in answering this question is to acknowledge that empirically, RO numbers have massively increased over the last decades. For two prominent examples, ROs make up around about 50% of all IOs active in international health policy, and about 65% in education policy today (Niemann et al., 2023). However, they were rarely the first IOs to cover a given policy field. Instead, they engaged with these topics only after global organizations had their mandate expanded to incorporate them. This development is remarkable because it demonstrates that although global structures for multilateral cooperation were already in place, nation states around the world were convinced that there was a niche for regional IOs to cover these issues. In other words, for so many ROs to incorporate these topics into their missions, there had to be a conviction among the member states that this step would yield benefits beyond what global organizations could provide. Multilateral climate policy provides a telling case here. Climate policy started as a highly internationalized field from the very beginning due to the nature of its core problems, but distinct regional arrangements were founded soon after the global infrastructure had been put into action. This is interesting because setting up a new department responsible for climate action, hiring experts on climate policy, or otherwise contributing to the development of policy costs time and money, both of which are scarce in intergovernmental bureaucracies. Consider the following statement from resolution AG/RES. 1440 (XXVI-O/96) of the Organization of American States (OAS) from 1996, in which the organization first adopted climate change as one of its areas of work, identifying the need to make use of the comparative advantages of the OAS not only by tapping cumulative experience but especially by directing the Organization toward areas where, in the opinion of the member states, opportunities exist for action to complement the efforts of the states themselves and efforts of other international organizations and institutions, particularly those operating within the Hemisphere (OAS, 1996).

Thus, regional organizations and their member states may view themselves as holding a “comparative advantage” over global IOs. This advantage does not necessarily manifest itself in terms of resources in staff or budget, which, for most regional organizations, is magnitudes smaller than those of global bureaucracies. Rather, it is expressed in their knowledge about local and regional connections and networks and insights into the respective social contexts in which they operate. In this view, regional organizations are uniquely situated (both literally and metaphorically) to deal with policy issues in a way that is both more likely to be effective and more likely to be accepted and supported by the citizens in their home regions.

This notion can be found within many regional organizations. The Pacific Community (SPC), for instance, stresses that addressing these Pacific challenges [of climate change] requires multilayered action, at all governance levels. Local biophysical, social, economic, political and cultural circumstances must prevail when designing adaptation and mitigation options (SPC, 2020).

The idea that ROs have unique insights into how “their” region works socially, culturally and politically and are thus able to design or contribute to designing better policy for that region is also present across policy fields. For instance, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has often emphasized the “ASEAN way” as a paradigm for security policy in Southeast Asia, which is based on informal rules and state sovereignty against outside (especially Western) influence (Caballero-Anthony, 2022). In conjunction with regional membership, external representation and regional scope of activities, it is this notion of uniqueness that distinguishes ROs from other IOs, and that makes them distinct units of analysis.

Regionalism

Regionalism is “a primarily state-led process of building and sustaining formal regional institutions and organizations among at least three states” (Börzel and Risse, 2016: p. 7). Historically, the literature on regionalism has distinguished between early, old and new regionalism. The latest development in research on regionalism may be called “comparative regionalism” and proposes both theoretical as well as methodological openness in order to generate insights from comparing different cases and instances of regionalism (Söderbaum, 2016). In new and in comparative regionalism, researchers have both focused rather heavily on processes of political integration, especially in the EU. Thus, European integration has been viewed as a model for regional integration in other regions, and the design philosophy of the EU as a guiding framework for other regional organizations, although it is entirely unclear whether that framework is transferable to other regional contexts (Acharya, 2016). Indeed, the available literature suggests that it is not, as regional organizations have pushed alternatives to the concept of “global governance” in some regions, the most prominent of which is ASEAN (Jetschke and Katada, 2016; Stubbs, 2008), and have contributed to shaping distinct regional identities (Checkel, 2016). Theories of regional integration have tended to ignore that “there is no single model of institution-building in world politics” (Acharya, 2014: p. 15).

Regional organizations as actors in international politics

Having distinguished between regions, regional organizations and regionalism, the following section summarizes how international organizations in general and regional organizations specifically matter in international politics, before relating these considerations to a framework of regional knowledge. Much has been written about the influence of international organizations and bureaucracies in international relations, and many of the avenues of IO influence naturally also apply to ROs. Most of these studies rely on a variety of institutionalist or constructivist frameworks, often combining both.

Constructivism and ROs

Constructivists have engaged with the influence of institutions, ideas and knowledge in world politics from multiple angles. As constructivism is not a theory of international relations specifically, but rather a general ontology about social life and social change, it usually needs to be complemented by an additional theoretical notion about which actors matter in order to be useful for analyzing empirical phenomena, such as IOs (Finnemore and Sikkink, 2001). Hence, institutionalist frameworks informed by constructivist assumptions have been employed to show how IOs act through the diffusion of norms and ideas, the fixing and framing of meanings, the creation and implementation of rules as well as the generation and administration of knowledge (Barnett and Finnemore, 2004; Rittberger et al., 2019). Constructivist scholars have also argued that IOs may be crucial in forming and maintaining what Haas calls “epistemic communities,” international networks of experts with shared beliefs which produce influential policy consensus (Haas, 1992). These theories establish different avenues to make sense of IOs (and thus, ROs) as actors in international relations. Constructivist institutionalism emphasizes the importance of institutions in structuring social relations and moderating behavior (Béland, 2016; Hay, 2016). However, since constructivist institutionalism is somewhat broad in its theoretical conceptualization of institutions, I develop a framework for regional ideas mthat is based on such assumptions but is better equipped to engage with regional organizations specifically.

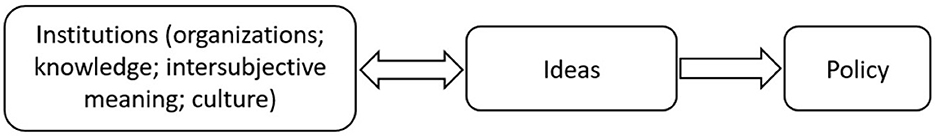

At their most basic, constructivist institutionalists agree that institutions, whatever form they may take, influence and moderate the behavior of purposive actors within the social contexts they reside in. In IR, one of the most common subjects is the creation and change of policy on international, national or sub-national levels, and how these interact with and co-constitute each other. Constructivists have contributed significantly to ideational research in IR by showing how institutions can exert influence in policymaking on all levels through ideas (Hay, 2011) and discourse (Schmidt, 2017). A basic constructivist notion of how institutions, ideas and policy relate to each other may therefore be summarized as follows (Figure 1). This sketch does of course not claim to be exhaustive and disregards, among other aspects, the constructivist assumption that these concepts may also be mutually constitutive. It rather serves illustrative purposes.

For constructivists, institutions can take many forms, such as organizations, knowledge, intersubjective meaning, culture, and tradition, which all hold explanatory power for political outcomes. While these terms describe distinct concepts, the literature is less clear about what precisely it is that separates them, and some of them have at times been used interchangeably (Finnemore and Sikkink, 2001). Many constructivist scholars have been “hesitant to explore the ways in which ideas are themselves affected by other factors” (Berman, 2001: p. 233), failing to explain how the ideas that influence policy outcomes come into existence in the first place (Campbell and Pedersen, 2015), while acknowledging their contested nature within IOs (Béland and Orenstein, 2013). In a regional setting, region-specific knowledge, I argue, is one of these factors. Knowledge has mostly been treated as “scientific knowledge” in IR (e.g., Allan, 2018; Paasi, 2015; Vadrot, 2017), ignoring the importance of knowledge from other sources such as experience. The following sections offer a typology of knowledge which accounts for these regional sources of knowledge. First, however, it is important to clearly define knowledge and ideas as analytical categories, as well as distinguish them from each other.

On the relationship between knowledge and ideas

Separating knowledge from ideas is not entirely unproblematic, and the distinction between both remains largely undertheorized in the literature. Goldstein and Keohane provide a widely accepted typology of ideas, which are “beliefs held by actors” (Goldstein and Keohane, 1993: p. 1) that can take different forms, such as principled beliefs, causal beliefs, or world views. Building on this conceptualization, a useful and more specific framework of policy ideas that distinguishes between problem definitions, policy solutions, and Zeitgeist is provided by Mehta (2011). I rely on this latter typology to make sense of the relationship between knowledge, ideas, institutions, and policy. Where an investigation of Zeitgeist is both beyond the scope of this article as well as analytically problematic, problem definitions and policy solutions are of particular interest for my purpose. They represent narrower forms of ideas, where problem definitions are “particular ways of understanding a complex reality.” These ideas, as per the term, define the problems to be solved by policy solutions, which Mehta takes to refer to the “means for solving the problem and accomplishing [a given set of] objectives” (Mehta, 2011: p. 29–30). ROs may produce or generate entirely novel policy ideas themselves, but they may also simply reproduce ideas disseminated to them from other actors, such as IOs or states, at times giving them their own distinct regional “twists.”

It is less straight forward to define knowledge. Indeed, although knowledge has been the subject of many philosophical debates, there is no undisputed epistemological definition of what it means to know something (Bolisani and Bratianu, 2018). The Britannica dictionary proposes that knowledge refers to “information, understanding, or skill that you get from experience or education.” For the purpose of this paper, it will suffice to rely on this somewhat limited definition.

Knowledge and ideas are commonly treated as broadly equivalent analytical categories in constructivism, or at least not clearly separate. Knowledge about causal relationships has sometimes been treated as a type of idea (e.g., Andersen and Breidahl, 2021). Similarly, policy ideas have been categorized as one form of expertise among others (e.g., Hirschman and Berman, 2014). However, the framework I propose here distinguishes between the two by defining ideas and knowledge as distinct but related analytical units, in the sense that ideas which an actor develops are at least partly dependent on the knowledge that the actor has access to. As I have argued elsewhere, for problem definitions and policy solutions, “knowledge is best understood as the cognitive background in regard to which actors define problems and conceptualize solutions” (Krogmann, 2024: p. 4). Knowledge thus precedes and moderates the production of policy ideas, which are “deriving from knowledge” (Christensen, 2021: p. 458). While an idea thus “generally invokes both normative and empirical descriptions in ways that are mutually reinforcing” (Mehta, 2011: p. 33), the same cannot be said for knowledge. For an actor to know something, it is required that this knowledge be “true,” or at least aspire to hold an element of “objective” and “factual” truth, not with standing that many knowledge claims will not meet this standard. Different epistemic philosophies of knowledge mostly agree that one cannot know something unless it is true. According to the classical tripartite definition of knowledge, knowledge is “justifiable true belief” (JTB), where all three of these elements are necessary conditions for knowledge (Haddock et al., 2009). An idea does not need to meet those criteria. Indeed, ideas clearly have an inherently normative component about which solutions are preferable to solve a problem with a given definition. They thus usually come with some sort of justification, and they are beliefs held by actors, but the are not necessarily true, nor do they aspire to be. While there is an ongoing epistemic debate about the JTB definition of knowledge, this distinction will suffice for the purpose of this article.

For a policy field-specific example, an actor might know that climate change is an empirical reality, as this knowledge can be acquired from sources that the actor considers legitimate, such as scientific resources, publications of international organizations or other, non-formal avenues. However, knowing about the causal relationship between global emissions and climate change does not yet tell the actor how he ought to judge this relationship. First of all, however unlikely, it is not inconceivable that some actors might not define climate change as a problem in the first place. For the actors that do so, there is a myriad of possibilities to conceptualize the problem, to propose solutions to the problem, and to prioritize these solutions in different ways. All of these contain an element of normative judgement on how climate change should be understood, which goes beyond causal knowledge claims. This is especially clear for problem definitions. Any problem definition works by excluding a range of meanings from the conceptualization of that problem, while incorporating others, in order to represent what the actor believes to be the nature or essence of the problem. In the given example of climate change, defining what makes climate change a problem also means defining which of its aspects are less or not at all problematic. If climate change, for instance, is defined as an economic problem, because of its potential to damage the global economy in unprecedented and unpredictable ways, this definition contains an implicit judgement about the importance of the global economy. Such a judgement can only be expressed on normative grounds, as there are no objectively agreeable criteria in regard to which all possible problem definitions of climate change could be ranked. Similar examples are easily imaginable for other policy fields. The key difference between knowledge and ideas in policy is thus that while knowledge claims aspire to represent objective truth (whether they accomplish that goal is another question), ideas, especially problem definitions, cannot exist without an element of normativity.

At the same time, to stay with the example above, knowing about climate change is a prerequisite for an actor to be able to formulate and put into action any policy ideas relating to it. While knowledge and ideas are therefore distinguishable analytical categories, they are also not completely independent of each other.

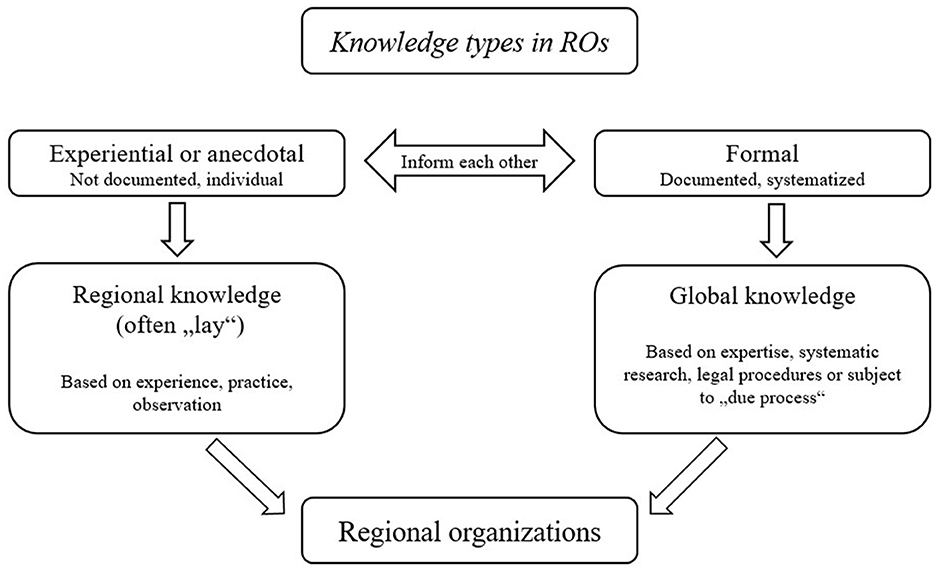

Knowledge types and regional organizations

There are different types and different sources of knowledge that IOs can mobilize to exert influence in world politics (Barnett and Finnemore, 1999; Sturdy et al., 2013). While most studies focus on how IOs employ expertise and scientific, formalized knowledge, Sturdy et al. have shown that IOs can also mobilize knowledge in other ways—“holistic, experience-based and context-sensitive” (Sturdy et al., 2013: p. 532). This type of knowledge, i.e., “regional knowledge,” is crucial for ROs. Access to regional knowledge is what makes ROs unique actors which act at the intersection of the global and the regional (Krogmann, 2023). This embeddedness in both regional and global political contexts allows them to mobilize “local, experiential and contextualized knowledge” as well as “non-local, objectified and generalized knowledge” (Rydin, 2007: p. 54) produced by scientific institutions. A comprehensive typology of knowledge is provided by Stepanova et al. (2020), expanding on the work of Rydin (2007). The following sections build upon this typology, while amending it to enable the analysis of regional organizations. Figure 2 shows the resulting typology.

Experiential or anecdotal knowledge is comprised of information or understanding about a given topic which is neither systematically documented nor otherwise formalized into rules, laws or official procedures. For example, one could imagine fisheries in the Carribean to experience decline in their yield because of climate-related environmental changes. Knowledge about this decline would first accumulate with local fishermen, before gaining regional notoriety. However, knowledge about such developments would likely remain limited to the affected region for some time, and accumulate mainly within individual fishermen, i.e., a specific subset of the regional population. Regional knowledge, then, refers to a body of knowledge which is based on “on the ground” experience, regional practice and observation through the affected groups and individuals. It is thus often “lay” knowledge, held by practitioners instead of policy experts or scientists.

Accordingly, formal knowledge is more systematized and closer to what is often called “expertise” in political science and IR (Littoz-Monnet, 2017). It is comprised of information that is documented and published in some form or another, and subject to “due procedure.” Such information feeds into what I refer to as global knowledge, because it is in principle accessible from anywhere in the world. It is also usually either sourced from scientific research and empirical evidence, or from national or international law. To stay with the example above, consider the manyfold studies which have been carried out by marine ecologists on how climate change negatively impacts fisheries around the world (e.g., Brander, 2010). These represent global knowledge. Anyone with access to the internet or a well-stocked university library can, in principle, draw on these insights and gain an understanding of the relationship between climate change and fisheries, without actually having to make any related experiences.

These bodies of knowledge may also inform each other, of course, but conceding that they do holds little analytical value beyond the awareness that these categories are less dichotomous in empirical reality. Some scholars argue that such a distinction is arbitrary in the first place, since positivist and structured knowledge, especially scientific knowledge, is less objective and much more biased than it supposes to be (Ramirez et al., 2019). I argue that distinguishing between these two types of knowledge is valid because their underlying knowledge claims are different. While they both claim to be true, global knowledge also aspires to be generalizable and replicable over time, space and social context, while regional knowledge does not.

ROs, then, hold a unique position in this knowledge grid as they serve as hubs for both global and regional knowledge, thus contributing to their “comparative advantage” vis-à-vis global organizations. RO officials have access to both regional and global knowledge, through member state input as well as work experience on local and regional policy issues on the one hand, and the global scientific community as well as their cooperations with other IOs on the other hand. They may experience first-hand that local fisheries are in decline, when they read about it in local newspapers or talk to representatives of local municipalities. They may then match this regional knowledge with the scientific evidence that fisheries are in decline globally, and connect that to the empirical reality of climate change, confirming what they gather from their day-to-day work. This combination of global knowledge with regional experience makes for a potent driver of ideational change. In principle, this assumption should be applicable to many policy fields. However, it is especially relevant to subfields of social policy, or fields that at least have a social policy dimension. Since the underlying objectives of these fields are highly context-dependent, so too is the knowledge required to design policies which are effective and legitimate in these contexts. Consider, for instance, education policy. What constitutes a “good education” will vary between nation states and regions, depending on socio-economic and cultural factors. While there are attempts to provide standardized global frameworks for education via international large scale assessments such as PISA, the norms set by these frameworks are not exhaustive or uncontested in regional contexts, especially in the Global South. Thus, knowledge about regional and local idiosyncracries and education ideals is key when designing regional education policy, which means that ROs will be able to make use of their “comparative advantage.”

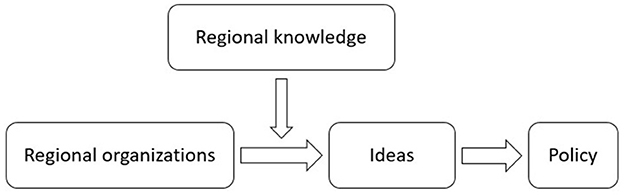

Combining this typology of knowledge with constructivist institutionalist assumptions about the interaction of institutions, ideas and policy results in a comprehensive framework of how ROs generate ideas by incorporating regional knowledge (see Figure 3).

ROs produce and reproduce ideas (problem definitions and policy solutions) which in turn influence the policies that they propose and implement. Regional knowledge serves as a moderating variable in this process, where ROs may take regional experiences into account and “cross-check” them with other sources of knowledge that they have access to. Ideas are thus determined, among other factors, by knowledge. Regional experience, practices and observations influence ROs' ideas through contributing to regional knowledge. Thus, this framework amends constructivist and institutionalist assumptions about the relationship between institutions, ideas, and policy and applies them to regional settings in ROs. Regional knowledge is only one source of knowledge, but it is more important and a larger part of the equation for these ROs than it may be in global IOs, which are necessarily cosmopolitan. Global IOs are producers of knowledge which has the claim to be valid independent of context.

It is important to note here that I am not disputing constructivism's claim that institutions and ideas are mutually constitutive. The causal relationship displayed in Figure 3 is perhaps not a one-way street in empirical reality. However, for the purpose of clarity, I will disregard the “feedback loop” of how ideas can also influence the institutional setups they originate in. This framework can explain ideas at specific “snapshots” in time, but it can also be used to explain ideational change over time, which constructivists have traditionally struggled to do (Carstensen, 2011). The creation, distribution and incorporation of new regional knowledge in RO settings may drive or contribute to ideational change in this way. If knowledge about a given problem changes, so may its definition and the solutions proposed in regard to it.

Discussion

This article has proposed a framework for analyzing the types of knowledge that moderate the policy ideas produced by regional organizations. I have argued that ROs are uniquely able to incorporate regional knowledge into their policy making, while at the same time tapping into globally available formal expertise and knowledge. In the following, I want to briefly assess two possible counterpoints to my argument.

First of all, an obvious retort to the basic premise of this article would be a rationalist view in which political action is based on the interest of calculating, utility-maximizing actors. Such a view would certainly dispute the attention I have granted both ideas as well ROs here. One could argue, as some rationalist approaches do, that ideas are second to material interests in explaining political outcomes, if they hold any causal influence at all. It could thus be argued that RO discourse and policies are just manifestations of their member states' aspirations and geopolitical interests. These are valid objections, but they do not contradict the framework as fundamentally as one might assume. Following Hay (2011), I contend that interests must be seen as socially constructed as well. Interests are just ideas given form, because what is meant by this term is what actors perceive as their interest, which in turn depends on ideas, norms, and values. Ideas and knowledge are what defines interest in the first place.

Second, there is an “elephant in the room,” which is that it remains unclear how exactly the mobilization of regional knowledge in ROs works in empirical reality. What is the mechanism by which ROs incorporate and manage knowledge? Which are the factors which drive ideational change on a micro level, and what is the role of RO officials as individual actors in this process? These questions come down to an agent vs. structure debate, and there is a number of possible constructivist and sociological answers. It may be that knowledge is diffused and synthesized mainly through socialization and social learning. RO officials, in this view, are purposeful actors acting back against the organizational settings they reside in, who translate their own physical interactions with their environment into political action (Blyth, 2011). However, it is beyond the scope of this article to provide a definite answer here. Future research is needed in order to better assess the determinants and conditions of knowledge mobilization in ROs.

Author contributions

DK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This article is a product of the research conducted in the Collaborative Research Centre 1342 “Global Dynamics of Social Policy” at the University of Bremen. The center was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project No. 374666841 – SFB 1342.

Acknowledgments

Parts of this article have previously been published online as contributions to the author's doctoral thesis.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acharya, A. (2009). Whose Ideas Matter? Agency and Power in Asian Regionalism. Ithaca, NY; London: Cornell University Press.

Acharya, A. (2016). “Regionalism beyond EU-centrism,” in The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism, eds. T. A. Börzel and T. Risse (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 109–130.

Allan, B. B. (2018). From subjects to objects: knowledge in international relations theory. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 24, 841–864. doi: 10.1177/135406611774152

Amaya, A. B., Rollet, V., and Kingah, S. (2015). What's in a word? The framing of health at the regional level: ASEAN, EU, SADC and UNASUR. Glob. Soc. Policy 15, 229–260. doi: 10.1177/1468018115599816

Andersen, N. A., and Breidahl, K. N. (2021). The power of ideas in policymaking processes: the role of institutionalised knowledge production in state bureaucracies. Soc. Policy Administr. 55, 848–862. doi: 10.1111/spol.12665

Barnett, M. N., and Finnemore, M. (1999). The politics, power, and pathologies of international organizations. Int. Organ. 53, 699–732.

Barnett, M. N., and Finnemore, M. (2004). Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics. Ithaca, NY; London: Cornell University Press.

Béland, D. (2016). Kingdon reconsidered: ideas, interests and institutions in comparative policy analysis. J. Compar. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 18, 228–242. doi: 10.1080/13876988.2015.1029770

Béland, D., and Orenstein, M. A. (2013). International organizations as policy actors: an ideational approach. Glob. Soc. Policy 13, 125–143. doi: 10.1177/14680181134846

Berman, S. (2001). Ideas, norms, and culture in political analysis. Comp. Polit. 33:231. doi: 10.2307/422380

Blyth, M. (2011). “Ideas, uncertainty, and evolution,” in Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research, eds. D. Béland and R. H. Cox (Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 83–100.

Bolisani, E., and Bratianu, C. (2018). “The elusive definition of knowledge,” in Emergent Knowledge Strategies: Strategic Thinking in Knowledge Management, eds. E. Bolisani and C. Brătianu (Cham: Springer), 1–22.

Börzel, T A. (2016). “Theorizing regionalism: cooperation, integration, and governance,” in The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism, eds. T. A. Börzel and T. Risse (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 41–63.

Börzel, T. A., and Risse, T. (2016). “Introduction,” in The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism, eds. T. A. Börzel and T. Risse T (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 3–15.

Brander, K. (2010). Impacts of climate change on fisheries. J. Mar. Syst. 79, 389–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2008.12.015

Caballero-Anthony, M. (2022). The ASEAN way and the changing security environment: navigating challenges to informality and centrality. Int. Pol. doi: 10.1057/s41311-022-00400-0. [Epub ahead of print].

Campbell, J. L., and Pedersen, O. K. (2015). Policy ideas, knowledge regimes and comparative political economy. Socio Econ. Rev. 13, 679–701. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwv004

Carstensen, M. B. (2011). Ideas are not as stable as political scientists want them to be: a theory of incremental ideational change. Polit. Stud. 59, 596–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00868.x

Checkel, J. T. (2016). “Regional identities and communities,” in The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism, eds. T. A. Börzel and T. Risse (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 559–578.

Christensen, J. (2021). Expert knowledge and policymaking: a multi-disciplinary research agenda. Policy Polit. 49, 455–471. doi: 10.1332/030557320X15898190680037

Deacon, B., Macovei, M. C., van Langenhove, L., and Yeates, N., (eds.). (2010). World-Regional Social Policy and Global Governance: New Research and Policy Agendas in Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin America. London: Routledge.

Finnemore, M., and Sikkink, K. (2001). Taking stock: the constructivist research program in international relations and comparative politics. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 4, 391–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.391

Goldstein, J., and Keohane, R. O. (1993). Ideas and Foreign Policy: Beliefs, Institutions, and Political Change. Ithaca, NY: London: Cornell University Press.

Haas, P. M. (1992). Introduction: epistemic communities and international policy coordination. Int. Organ. 46, 1–35.

Haddock, A., Millar, A., and Pritchard, D. (2009). Epistemic Value. Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hawkins, D. G., and Jacoby, W. (2006). “How agents matter,” in Delegation and Agency in International Organizations, eds. D. G. Hawkins, D. A. Lake, D. L. Nielson, and M. J. Tierney (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 199–228.

Hay, C. (2011). “Ideas and the construction of interests,” in Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research, eds. D. Béland and R. H. Cox (Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 65–81.

Hay, C. (2016). Good in a crisis: the ontological institutionalism of social constructivism. N. Polit. Econ. 21, 520–535. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2016.1158800

Heymann, M. (2010). The evolution of climate ideas and knowledge. WIREs Clim. Change 1, 581–597. doi: 10.1002/wcc.61

Hirschman, D., and Berman, E. P. (2014). Do economists make policies? On the political effects of economics. Socio Econ. Rev. 12, 779–811. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwu017

Jetschke, A., and Katada, S. N. (2016). Asia. In: Börzel TA and Risse T. (eds). The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism: Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jetschke, A., and Lenz, T. (2013). Does regionalism diffuse? A new research agenda for the study of regional organizations. J. Eur. Public Policy 20, 626–637. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2012.762186

Jetschke, A., Münch, S., Cardozo-Silva, A. R., and Theiner, P. (2021). Patterns of (dis)similarity in the design of regional organizations: the regional organizations similarity index (ROSI). Int. Stud. Perspect. 22, 181–200. doi: 10.1093/isp/ekaa006

Kornprobst, M., and Paul, T. V. (2021). Globalization, deglobalization and the liberal international order. Int. Aff. 97, 1305–1316. doi: 10.1093/ia/iiab120

Krogmann, D. (2023). Explaining Regional Problem Definitions and Policy Solutions: A Comparative Account of Regional Organizations in Climate and Education Policy. doi: 10.26092/elib/2647

Krogmann, D. (2024). Here to stay? Challenges to liberal environmentalism in regional climate governance. Glob. Policy 15, 288–300. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.13321

Lake, D. A., Martin, L. L., and Risse, T. (2021). Challenges to the liberal order: reflections on international organization. Int. Organ. 75, 225–257. doi: 10.1017/S0020818320000636

Littoz-Monnet, A., (ed.). (2017). The Politics of Expertise in International Organizations. London: Routledge.

Lönnqvist, A., Käpylä, J., Salonius, H., and Yigitcanlar, T. (2014). Knowledge that matters: identifying regional knowledge assets of the tampere region. Eur. Plann. Stud. 22, 2011–2029. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2013.814621

Mehta, J. (2011). “The varied roles of ideas in politics: from “whether” to “how”,” in Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research, eds. D. Béland and R. H. Cox (Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 23–46.

Moravcsik, A. (1995). Liberal Intergovernmentalism and Integration: a Rejoinder. J. Common Mark. Stud. 33, 611–628.

Niemann, D., Krogmann, D., and Martens, K. (2023). Torn into the abyss? How subpopulations of international organizations in climate, education, and health policy evolve in times of a declining liberal international order. Glob. Govern. 29, 271–294. doi: 10.1163/19426720-02903004

Niemann, D., and Martens, K. (2018). Soft governance by hard fact? The OECD as a knowledge broker in education policy. Glob. Soc. Policy 18, 267–283. doi: 10.1177/1468018118794076

OAS (1996). AG/RES. 1440. (XXVI-O/96). Resolution Adopted at the Eighth Plenary Session, Held on June 7, 1996. Available online at: http://www.oas.org/juridico/english/ga-res96/Res-1440.htm (Accessed March 5, 2021).

O'Reilly, P., and Heron, T. (2023). Institutions, ideas and regional policy. (un-)coordination: the East African community and the politics of second-hand clothing. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 30, 608–631. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2022.2062614

Paasi, A. (2011). The region, identity, and power. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 14, 9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.011

Paasi, A. (2015). “Academic capitalism and the geopolitics of knowledge,” in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Political Geography, eds J. A. Agnew, V. Mamadouh, A. J. Secor, and J. P. Sharp (Chichester; West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell), 507–523.

Panke, D., Stapel, S., and Starkmann, A. (2020). Comparing Regional Organizations: Global Dynamics and Regional Particularities. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Ramirez, R., Ravetz, J., Sharpe, B., and Varley, L. (2019). We need to talk (more wisely). About wisdom: a set of conversations about wisdom, science, and futures. Futures 108, 72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2019.02.002

Rittberger, V., Zangl, B., Kruck, A., and Dijkstra, H. (2019). International Organization. London: Red Globe Press.

Rydin, Y. (2007). Re-examining the role of knowledge within planning theory. Plann. Theory 6, 52–68. doi: 10.1177/1473095207075161

Schmidt, V. A. (2017). Theorizing ideas and discourse in political science: intersubjectivity, neo-institutionalisms, and the power of ideas. Crit. Rev. 29, 248–263. doi: 10.1080/08913811.2017.1366665

Söderbaum, F. (2016). “Early, old, new and comparative regionalism: the history and scholarly development of the field,” in The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism, eds. T. A. Börzel and T. Risse (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 16–37.

SPC. (2020). Climate Change and Environmental Sustainability. Available online at: https://www.spc.int/cces (Accessed April 9, 2021).

Stepanova, O., Polk, M., and Saldert, H. (2020). Understanding mechanisms of conflict resolution beyond collaboration: an interdisciplinary typology of knowledge types and their integration in practice. Sust. Sci. 15, 263–279. doi: 10.1007/s11625-019-00690-z

Stubbs, R. (2008). The ASEAN alternative? Ideas, institutions and the challenge to ‘global' governance. Pac. Rev. 21, 451–468. doi: 10.1080/09512740802294713

Sturdy, S., Freeman, R., and Smith-Merry, J. (2013). Making knowledge for international policy: WHO Europe and Mental Health Policy, 1970-2008. Soc. Hist. Med. 26, 532–554. doi: 10.1093/shm/hkt009

Vadrot, A. B. M. (2017). Knowledge, international relations and the structure–agency debate: towards the concept of “epistemic selectivities”. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 30, 61–72. doi: 10.1080/13511610.2016.1226787

van Langenhove, L. (2013). What is a region? Towards a statehood theory of regions. Contemp. Polit. 19, 474–490. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2013.853392

Keywords: regionalism, regional organizations, knowledge, ideas, problem definitions, policy solutions

Citation: Krogmann D (2025) Mobilizing contextual knowledge: regional organizations and the genesis of policy ideas. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1516516. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1516516

Received: 24 October 2024; Accepted: 07 July 2025;

Published: 22 July 2025.

Edited by:

Mely Caballero-Anthony, Nanyang Technological University, SingaporeReviewed by:

Erick da Luz Scherf, University of Alabama, United StatesArina Suvorova, Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia

Copyright © 2025 Krogmann. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David Krogmann, a3JvZ21hbm5AdW5pLWJyZW1lbi5kZQ==

David Krogmann

David Krogmann