- 1Department of Social Sciences, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

- 2Faculty of Sociology, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

- 3European School of Political and Social Sciences, Lille Catholic University, Lille, France

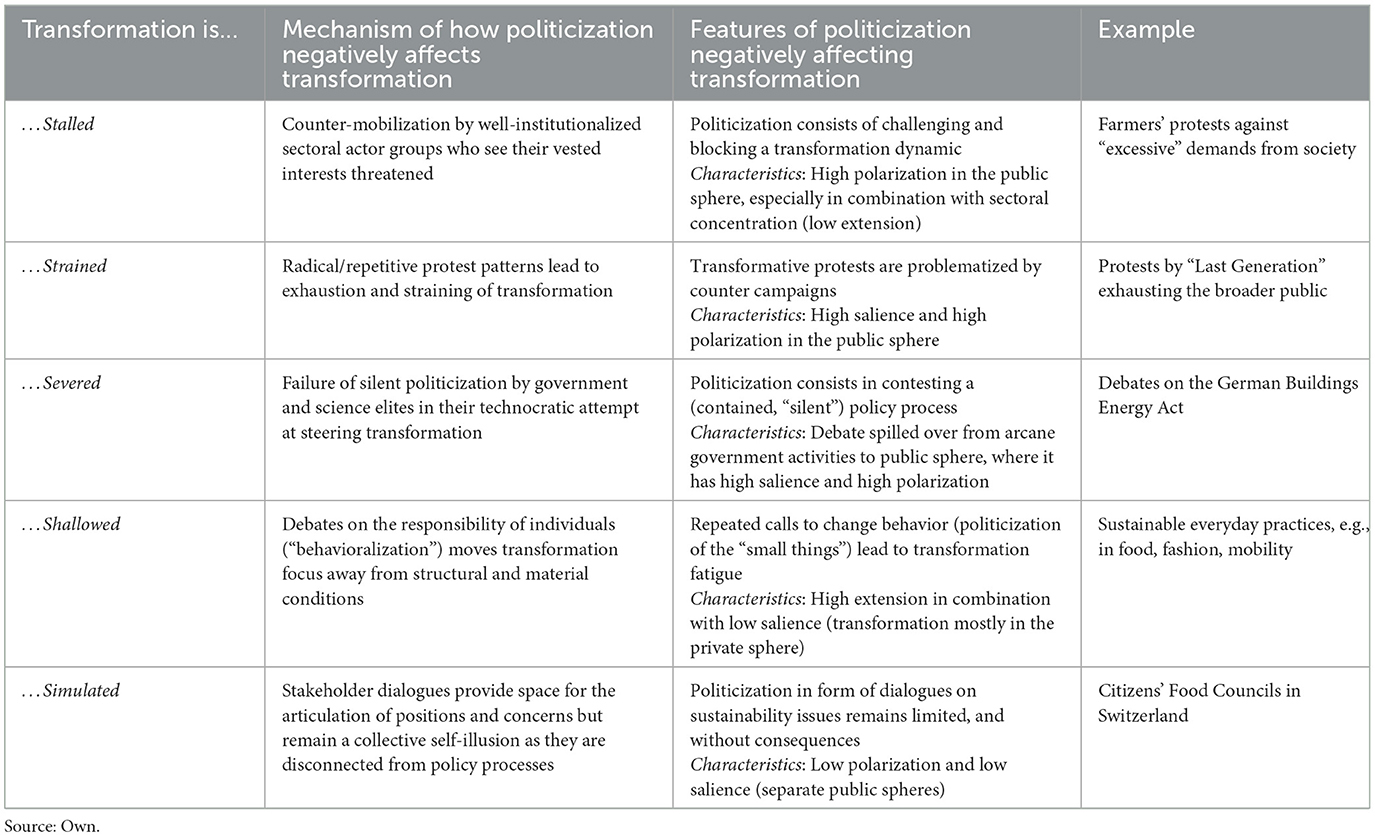

The relationship between politicization and sustainability transformation is complex and multifaceted. Politicization is often viewed as a catalyst for sustainability transformations. Through contestation and mobilization of societal actors, it provides the impetus for broad and deep social change, bringing societies onto more just and ecologically sustainable pathways. At the same time, politicization can also have detrimental effects, potentially creating fatigue among the public, fostering division rather than unity, and undermining the public support and engagement necessary for effective change. This article aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the complex relationship between politicization and transformation. To this end, we focus specifically on the negative effects, i.e., how politicization undermines sustainability transformations. Drawing on empirical examples of “politicized transformation,” we identify five different mechanisms by which politicization can stall, strain, sever, shallow, or simulate transformation efforts. We discuss how these mechanisms interact over time to form broader dynamics that undermine or obstruct sustainability transformations and point to potential strategies to counteract these dynamics.

Introduction

We live in turbulent times characterized by two major, interrelated dynamics. For one, in the face of escalating social and ecological crises, more or less deliberate attempts are being made to initiate and shape profound processes of social change, that is, sustainability transformations. At the same time, a new quality and intensity of “the political” can be observed, with societies becoming increasingly politicized. Proponents of sustainability transformations have long hoped for moments of politicization to provide the impetus for broad and deep social change needed to bring societies onto more just and ecological pathways. In this vein, “Fridays for Future” has been heralded as the (overdue) climate political awakening of societies, mobilizing large masses and creating political pressure for fundamental change. Indeed, there are signs of significant impact, such as the 2021 climate ruling of the German Federal Constitutional Court in response to a lawsuit filed by young climate activists and NGOs, which declared essential elements of the Federal Climate Protection Act unconstitutional because they did not sufficiently protect the rights of future generations. Others, however, are more skeptical about a straightforward link between politicization and transformation. (Jäger 2023) recently described the current era as one of “hyperpolitics,” characterized by intense politicization and weak institutionalization. Beginning around 2017, and following a phase of antipolitics, hyperpolitics involves brief bursts of political engagement that often fizzle out without achieving significant results. The quick rise and fall of (online) mobilizations around, amongst others, climate issues illustrate this dynamic of hyperpolitics, where digital attention peaks but fails to translate into any form of social change. Politicization resembles a straw fire that flares up rapidly and furiously, only to quickly die out without leaving a transformative imprint. (Swyngedouw 2015, p. 2–3) was among the first to draw attention to the somewhat “paradoxical situation” in which political mobilization about environmental issues might become a “constituent force in the production of depoliticization,” ultimately perpetuating rather than changing the status quo. Some go even further and warn of the “dark sides” of politics and politicization that could potentially obstruct transformation (Ginsberg, 2024). From this perspective, politicization has become a counterforce to transformation.

We believe that such broad diagnoses underestimate both the diversity of the two processes and the complexity of their interactions (see Walker et al., 2018, on “diagnosing the present”). This article builds on the assumption that politicization and transformation each reveal complex dynamics that are interconnected in multiple and ambiguous ways. Neither politicization nor transformation are simple processes but represent multifaceted phenomena (Horcea-Milcu et al., 2024; Scoones et al., 2020). Different forms of politicization have different effects on transformation processes, and whether and how politicization affects transformation processes depends on the nature of these dynamics and the mechanisms through which they are linked. We aim at contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the ambivalent and complex relationship between politicization and transformation. Our focus, however, is on the negative effects, i.e., how politicization undermines sustainability transformations. Specifically, we demonstrate how politicization can stall, strain, sever, shallow, or simulate transformation efforts.

We think that these dynamics are not coincidental but, on the contrary, are at least partly inherent to sustainability transformation discourses with their emancipatory logic and ambition to overcome the existing order, to open up spaces for contestation and search for alternatives (Blühdorn, 2024). Still, we do not assume these (self-)destructive dynamics to be necessary and unavoidable. We argue that understanding the fundamental mechanisms is vital for preventing sustainability transformation from undermining itself. Our goal is to elucidate these mechanisms, i.e., the conditions and factors that contribute to politicization becoming a counterforce to transformation. The empirical examples used to analyze and illustrate the five mechanisms of politicization: stalling, straining, severing, shallowing, and simulating sustainability transformations are drawn from prominent cases in Germany and Switzerland that received broad political, media, and societal attention between 2019 and 2023. They were selected purposefully to cover a range of policy areas (agriculture, climate activism, energy use in buildings, everyday consumption, participatory governance) and to reflect different dynamics of politicization across various spheres of politics (official, public, and private). The examples presented are neither developed as full case studies nor analyzed comparatively in a systematic manner. Rather, they serve as illustrative empirical vignettes to exemplify different patterns of politicization and their effects, based on publicly available sources (media reports, academic studies, and government documents) and on the authors' contextual knowledge of the cases. The empirical approach is therefore exploratory and illustrative in nature.

Importantly, our focus on the “dark sides” of politicization in no way implies a rejection of politicization as a critical transformative force, nor does it signal an endorsement of depoliticization. Yet, we caution against the euphoria surrounding politicization that has taken hold in parts of the transformation community, and we seek to offer insights into how mechanisms creating negative links between politicization and transformation might be mitigated or redirected toward more constructive transformative pathways. By better understanding the specific mechanisms of counter-transformation through politicization, we contribute to differentiating the broad-brush societal diagnoses and the effects, hopes, and dangers associated with them. This can form the basis for considering more politically reflexive strategies for transformation.

The article begins with an exploration of basic links between transformation and politicization, highlighting the inherent ambiguity of their relationship. We then unpack both concepts to provide a more nuanced foundation to explore how politicization may negatively affect transformation. On this basis and drawing on several empirical examples to illustrate our points, we examine how politicization may stall, strain, sever, shallow, and simulate transformation. We discuss our observations in the light of broader developments in contemporary political contexts, reflect on practical strategies to address the negative dynamics between politicization and transformation, and sketch directions for future research on the topic.

Enabling transformation: from politicization to depoliticization—and back again?

Contributions to the relationship between politicization and transformation are scattered across various literatures and rarely share a common conceptual basis. Authors use different terms and have not yet systematically studied the links between politicization and transformation. The politicization-transformation nexus often functions as a projection screen for hopes and warnings (Pepermans and Maeseele, 2016). On the one hand, politicization in the context of sustainability transformations enables citizens to ultimately determine the appropriateness of policy proposals (Hällmark, 2023); on the other hand, “politicization may lead to a lack of consensus on how to halt climate change and environmental degradation” (ibid., p. 62). These divergent interpretations are shaped by academic, social, and political conjunctures (e.g., Jäger, 2023; Blühdorn, 2024).

Early positions, recently subsumed by (Blühdorn 2022) under the term “eco-emancipatory project,” placed their hopes in the positive effects of politicization, assigning a central role to the environmental movement that emerged from the New Social Movements of the 1970s and 1980s. Their critique of the state—highlighting its complicity in the creation and perpetuation of a growth-oriented, capitalist economy and consumer society, along with the resulting ecological crisis—was fundamentally tied to the notion of a new emancipatory politics grounded in the Enlightenment ideal of the autonomous political subject. From this perspective, overcoming the ecological crisis would require more than political reforms within the existing system; it would demand a profound re-politicization through robust participatory democracy capable of challenging and transforming entrenched political and economic structures. A prominent historical example of this eco-emancipatory project is the anti-nuclear movement in Germany, which employed grassroots mobilization to articulate a broader critique of capitalist industrial society.

Yet, perceptions of politicization's role in transformative change began to shift in the 1990s. As neoliberal globalization unfolded and the state's influence over economic and social governance declined, the impact of social movements on social change likewise diminished. The rise of the “governance” discourse brought cooperative policymaking, engaging different social stakeholders, into focus. This approach resonated strongly with the emerging concept of sustainability and the recognition of increasingly complex, socially dispersed problems. Rather than emphasizing the politicization of social movements, stakeholder involvement became the strategy for managing complexity and uncertainty in the pursuit of sustainability change. This “governance turn” fundamentally altered prevailing understandings of politicization. Rather than relying on direct political confrontation, new governance models sought to engage a range of actors, including the state, market, and civil society, in collaborative forms of action. While this approach aimed to harness collective resources for problem-solving, it simultaneously depoliticized and neutralized some of the radical potentials of earlier movements by prioritizing consensus and coordination over conflict and emancipation.

Despite certain successes, the 2010s saw the emergence of sharp critiques targeting the post-political tendencies in sustainability governance (Swyngedouw, 2015). These critiques were in part a response to governance failures exposed by the financial, economic, and Euro crises. At the same time, the decade was increasingly characterized by more fundamental, anti-political tendencies (Jäger, 2023), particularly in the realm of environmental and climate policy. Diagnosing the “death of environmental politics,” Ulrich Beck observed: “In the name of indisputable facts portraying a bleak future for humanity, green politics has succeeded in depoliticizing political passions to the point of leaving citizens nothing but gloomy ascetism, a terror of violating nature and an indifference toward the modernization of modernity. Everything happens as if green politics has frozen politics into a kind of immobility” (Beck, 2010, p. 263). In a similar vein, (Swyngedouw 2011, 2015) warned against a depoliticized environmental consensus and the emergence of non-political politics of climate change. From this perspective, political dynamics and conflicts are seen as inherent in any form of sustainability transformation. Public contestation and protest are viewed as catalytic forces, capable of opening up alternative futures and disrupting the “apolitical politics of climate change” (Swyngedouw, 2015). In fact, with the rise of broad movement phenomena—from Occupy to Fridays for Future to Black Lives Matter—a new phase of “re-politicization” (Anshelm and Haikola, 2018) seems to have emerged. For many, this recent wave of politicization represents the long-awaited turning point in the socio-ecological transformation.

Others, however, remain more skeptical. (Pavenstädt 2024) argues that more recent attempts at politicization tend to unfold within narratively constrained frameworks (referring to “evidence first” or “system change”) and, in this respect, take on the character of a “bounded politicization,” with limited potential for transformation. (Jäger 2023) likewise questions the depth and efficacy of re-politicized climate politics. His notion of “hyperpolitics” describes a pervasive yet incoherent and highly volatile drive to politicize—one that lacks substantive consequences. In this view, the dynamics of re-politicization have lost their transformative force. (Blühdorn 2024), in turn, interprets re-politicization as a symptom of the failure of the social-ecological transformation project. He introduces the notion of a reflexive re-politicization, arising from within the socio-ecological transformation processes, and identifies self-destructive tendencies within the emancipatory project itself. As he puts it: “What had previously been achieved in terms of an eco-political consensus on transformation is being re-politicized. The crisis of socio-ecological transformation is not simply caused by the resistance of the capitalist system. Rather, [...] the eco-emancipatory project is also essentially collapsing due to its own logic and internal contradictions. To a certain extent, it is becoming obsolete due to its emancipatory success” (Blühdorn, 2024, p. 16–17).

The diagnoses and associated hopes regarding the transformative effects of politicization thus remain deeply ambivalent. In the light of this ambivalence, we argue that the links between politicization and transformation are not only shaped by historical and political conjunctures but also mediated by specific mechanisms that warrant empirical investigation. Unpacking these mechanisms requires a more nuanced conceptual understanding of politicization and transformation, to which we now turn.

Conceptualizing politicization and sustainability transformation

In this section, we clarify basic understandings of politicization and sustainability transformation and identify dimensions and conceptual reference points that allow us to explore these phenomena and their interconnections.

Politicization

Politicization is a concept with multiple meanings. Most definitions refer to a state and/or process of becoming political, thereby tying the concept closely to the notion of “political” itself (e.g., Wiesner, 2021). Yet, understandings of what constitutes the “political” vary. In some accounts, the “political” is conceived as a distinct sphere of social interaction and communication, and politicization is seen as a movement into this realm. In other approaches, the political is defined as a particular quality, distinct from non-political qualities such as the economic or scientific, implying that politicization entails a shift in the nature or degree of engagement. In this sense, a previously non-political object, such as an idea, institution, practice, action, knowledge, belief, identity, interaction etc., becomes (increasingly) political. These two perspectives—understanding the political as either a sphere or a quality—can be viewed as complementary. An issue that enters the political sphere simultaneously acquires a political quality, and vice versa. Yet this raises a fundamental question: What distinguishes the political, whether as a sphere or a quality, from the non-political?

According to (Laclau and Mouffe 2001), the “political” refers to the dimension of antagonism inherent in human societies, representing the fundamental conflicts and power struggles that shape collective identities and social relations. Mouffe emphasizes that the political is marked by the ever-present potential for conflict and the operation of power, both of which are intrinsic to the formation of social orders and the establishment of hegemonies (Mouffe, 2005). “Politics” in contrast refers to the set of practices, discourses, and institutions through which an order is created, stabilized, and contested within the framework of the political. Politics, in this view, is the realm of institutionalized conflict and negotiation, where power relations are articulated and managed (Laclau and Mouffe, 2001). On this basis, “politicization” can be understood as the process through which issues become contingent and enter the realm of contestation and public debate (Flügel-Martinsen, 2020).

Building on this general understanding, politicization refers to a fundamental societal dynamic encompassing a wide range of phenomena. To better grasp this diversity, two additional analytical distinctions prove useful: The first relates to modes of politicization and reflects the fact that politicization can manifest in multiple dimensions and forms (Hay, 2007; de Wilde et al., 2016; Zürn, 2018). One such dimension is salience which refers to the visibility of a contested issue—the more visible a contested issue is, the more politicized it is. Polarization captures the distance between opposing positions in a debate or dispute, with a greater distance indicating greater polarization and, consequently, a stronger degree of politicization. Finally, extension refers to the spread of a contentious issue. An issue is considered more politicized when it mobilizes broader segments of the population, as opposed to being confined to particular groups, sectors, or social arenas.

The second analytical distinction concerns the locus of politicization, capturing different contexts in which politicization can occur. Building on a prominent proposition by (Hay 2007), three spheres of politics can be distinguished—“private,” “public,” and “official”—each representing a domain where contingency can arise/be created (politicization) or can disappear/be removed (depoliticization). The private sphere encompasses the actions of individual and collective actors that relate to the pursuit of their private goals, not linked to public concerns. Typically, this includes private consumption, as well as corporate activities that take place on private grounds (e.g., regulated by private law). In a classical understanding, politics ends where the private sphere begins, thus separating the private from the political. However, this boundary has been increasingly contested, prompting a reconsideration of the private sphere as a potential site of the political (Mahajan, 2009). Politicization in the private sphere refers to phenomena in which taken-for-granted beliefs, values, norms, knowledge, and practices are problematized, thereby becoming contingent and contestable.

The public sphere encompasses the actions of individual and collective actors within a political system that, while not yet collectively binding, are relevant to the political community as a whole. This sphere spans a wide spectrum—from individual citizen contributions in public discourse and media debates to the strategic, long-term efforts of organized interest groups such as social movements, political parties, and associations. These actors seek to shape public opinion and influence collective decision-making processes by mobilizing support, framing issues, and advocating specific agendas.

The realm of official politics comprises all activities related to the preparation, communication, and implementation of collectively binding decisions. It includes not only the institutional structures and general expectations that govern these activities but also the constellations of individual and organized actors involved, along with the practices and procedures through which coordination, evaluation, and alignment are achieved. Politicization in this formal space refers to the generation of contingency, controversy, and decision-making regarding previously uncontested problem interpretations, goals, and measures, as well as institutions and procedures.

Depoliticization, by contrast, describes the displacement or suppression of contention, conflict, and debate. Most significantly, the “post-political” era is characterized in the literature as a systemic condition in which technocratic and institutional strategies are employed to neutralize or preclude political contestation across all spheres (Wilson and Swyngedouw, 2014). At its core, depoliticization negates contingency. Proponents of the post-political reject the notion of political consideration and decision, asserting that “there is no alternative” to existing institutions, procedures, and policy frameworks. Recent contributions from critical theorists of environmental politics argue that post-politics extend beyond the official sphere of politics within the state, permeating places and spaces beyond the national scale as well. From this perspective, the post-political condition is a multi-scalar phenomenon that inhibits transformative action across both societal spheres and geographical scales (Kythreotis, 2023).

Sustainability transformation

Sustainability transformation has become a central—albeit often loosely defined—concept in sustainability research and practice. It highlights the need for profound changes in the structural, functional, relational, and cognitive aspects of socio-technical and ecological systems to address the interlinked crises facing contemporary societies (Patterson et al., 2017). The term transformation is used both analytically, to describe the actual changes within societal or socio-ecological systems, and normatively, to articulate visions of desirable pathways toward more sustainable futures.

The concept of sustainability transformation extends beyond earlier concepts of sustainable development by emphasizing the need for societies around the globe to fundamentally rethink and reshape their socio-ecological development pathways and patterns of production and consumption (Scoones et al., 2020). Yet perspectives diverge on whether such transformations are emergent and evolutionary, or can be steered: Some scholars see transformations as complex, dynamic, and co-evolutionary processes that emerge from ongoing interactions between human systems (such as values, knowledge, and technology) and environmental systems (Norgaard, 1995, 2006). Others argue that transformations can also be purposefully navigated or steered. This involves intentional efforts to instigate fundamental changes at structural levels, for example, in response to challenges like climate change. Approaches such as “transformative adaptation” underscore the importance of deliberate action to contest entrenched conditions and foster alternative futures, highlighting the role of human agency, intentionality, and motivation in steering transformation processes (O'Brien, 2012).

In summary, transformations toward sustainability involve a dynamic interplay between emergent processes and intentional governance actions aimed at guiding systemic change. By implication, transformations are recognized as deeply political and contested processes (Meadowcroft, 2007; Scoones et al., 2015). Transformative changes affect actors unevenly, resulting in potential winners and losers during the transformation journey. This complexity is further compounded by competing narratives and divergent perceptions of what sustainability entails and how it should be achieved, which must be navigated in the pursuit of sustainable futures.

In this article, we use the term transformation in an open and context-sensitive manner, rather than referring to a specific, normatively defined pattern of change. The term is further concretized along the following dimensions. First, we distinguish sustainability transformations based on their breadth and depth. Transformations are broad when they span and interlink multiple societal sectors, domains, or fields. For example, decarbonization constitutes a broad transformation insofar as it requires reducing both direct and indirect carbon emissions across the entire economy and society. In contrast, transformations are described as narrow when confined to a specific domain, such as the energy or mobility sector, or even a particular organization. From a socio-spatial perspective, breadth can also be understood in terms of geographic scale: transformations may expand as they diffuse across urban, regional, and national levels, as exemplified by the vision of a “post-fossil city” (Hajer and Versteeg, 2019). Conversely, transformations may remain narrow when cities are reduced to mere sites of fossil fuel extraction and its associated practices.

The depth of transformation refers to the extent to which systemic change occurs. Deep transformations involve a fundamental reconfiguration of how systems function, whereas shallow transformations are limited to surface-level or instrumental adjustments. (Hausknost 2020) makes a similar distinction between lifeworld sustainability, which denotes the superficial greening of individual lifestyles, and system sustainability, which targets the structural parameters that determine environmental outcomes (e.g., CO2 concentration). A governance-oriented perspective is provided by the concept of “leverage points” for sustainability transformations (Abson et al., 2017), which categorizes different levels of intervention within complex systems. While shallow interventions may alter operational practices within existing frameworks, deep leverage points aim at transforming the underlying value structures and normative orientations that shape system dynamics.

While breadth and depth describe the systemic scope of sustainability transformations, these processes also unfold over time and exhibit certain temporal qualities. Transformations are inherently non-linear and variable in pace, progressing through different phases, accelerating or decelerating, and extending over shorter or longer durations. Their specific trajectories often emerge from the interplay of steering efforts and emergent properties. Concepts to capture the process dimension are “sustainability pathways” and “transformation journeys” (e.g., Patterson et al., 2017). These concepts emphasize that transformative change rarely follows a linear trajectory. Instead, it is shaped by iterative processes, feedback loops, and unpredictable outcomes. This perspective underscores the importance of considering interconnected changes across multiple domains—social, political, institutional, technological, and environmental—in their specific contexts. As (Scoones et al. 2015 p. 21) argue, “rather than there being one big green transformation, it is more likely that there will be multiple transformations that will intersect, overlap, and conflict in unpredictable ways”.

How politicization negatively affects sustainability transformations

The preceding conceptual discussion highlights that both politicization and transformation are complex and multifaceted processes that, by implication, can be intertwined in various ways. Building on these clarifications, we now explore when and how politicization may negatively affect processes of sustainability transformation. To do so, we examine several empirical cases in which transformation—as a project, policy, or idea—has become politicized. Across varying levels of abstraction, we find evidence of five recurring patterns through which politicization can impede or distort transformation: it can stall, strain, sever, shallow, or simulate transformation. In the following sections, we describe each pattern and identify the mechanisms by which politicization exerts negative effects. To illustrate each pattern, we provide examples that stem from German politics as well as from Switzerland. A summary of these observations is provided in Table 1.

In the hands of vested interests: politicization stalling transformation

The first transformation-inhibiting effect of politicization can be described as “stalling.” In this pattern, a transformation pathway or project that has been set in motion is slowed down or brought to a halt as a result of the politicization it has triggered. This connection is neither surprising nor uncommon, given that transformations often have far-reaching implications and disrupt established norms, practices, and institutional arrangements (Sommer and Schad, 2022). By questioning dominant values and reconfiguring social and material orders, transformations generate uncertainty and contestation. When the interests, values, and identities of relevant societal actors are affected, resistance emerges—whether in the form of direct opposition, disengagement, or strategic obstruction. Actors may resist because they have different priorities and goals, see their interests threatened, or feel disoriented by the pace and scope of change. The expectation of losing out in the transformation process can also trigger backlash. Stalling thus reflects a broader political dynamic in which proponents of transformation encounter organized or diffuse efforts to preserve the status quo.

An example of stalling dynamics can be seen in the farmers' protests that occurred in many European countries in the years 2022/23. These protests reflected concerns about environmental regulations, mounting economic pressures faced by farmers across Europe, and broader dissatisfaction with evolving agricultural policies (Politico, 2024). The concrete topics and demands of the farmers in the protests differed between countries. In Germany, for example, the abolition of tax breaks for agricultural diesel was a particular concern of the protesters, as were the increased costs for inputs such as feed, fuel, and energy. Viewed in a broader context, these protests can be interpreted as a reaction to the politicization of the (environmental) side-effects of agriculture, which had led to growing public and political demands placed upon farmers. This background politicization, coupled with targeted subsidy cuts which some policymakers in fact presented as a contribution to the sector's transformation, sparked widespread backlash. Through road blockades and protests, farmers sought to draw public attention to their perceived marginalization and economic vulnerability. Protesters and their political representatives denounced both the specific policies and the broader direction of the transformation agenda, arguing that it jeopardized their socioeconomic livelihoods. At the same time, they demanded recognition of their essential contributions to food production, rural community life and landscape stewardship.

The farmers' protests example illustrates how politicization can lead to the stalling of transformation when certain conditions are present. A combination of high public visibility, the strong polarization of actors along deep-rooted rural-urban divides, and the protests' strong sectoral anchoring contributed to effectively halting the transformation process. At the same time, the example of the farmers' protests shows that it is not necessarily a transformation policy itself that triggers politicization. Rather, resistance can be sparked by the perception and discursive labeling of a political measure as transformative. This dynamic was clearly visible in the farmers' protests in Germany, where a relatively narrow measure—the abolition of tax breaks for agricultural diesel—was not only perceived as inappropriate by its critics, but also contributed a broader rejection of transformation as a whole (The Guardian, 2024).

Sand in the gears: politicization straining transformation

Politicization can lead to the straining and exhaustion of transformation processes when it undermines public support and individuals' willingness to contribute to or endorse change. While parts of the literature on sustainability transformation suggest that transformative dynamics will accelerate over time—as sustainability ideas spread throughout society and political institutions—this is not an automatic process (Linnér and Wibeck, 2020). Transformation trajectories are also prone to disruption, deceleration, or even stagnation. This holds, among others, in situations where the transformation is perceived as tiresome, a nuisance, or overwhelming by some actors.

An illustrative case is the actions of the “Last Generation” in Germany, a group that emerged in 2021 from the youth climate movement “Fridays for Future.” With the stated goal of pushing governments to adopt more ambitious climate policies in line with the Paris Agreement, this group has significantly politicized climate change and the German government's climate policies through repeated protest actions in streets and airports, as well as in cultural venues such as museums and concert halls, e.g., protesters gluing themselves on streets, or spray-painting art objects. Their actions, which they themselves framed as civil disobedience, took place in highly visible public places to ensure maximum attention. Particularly in 2021 and 2022, the actions garnered significant public attention (Lederer et al., 2024). Although the protests remained local and involved only a relatively small number of participants, they were widespread and broad media coverage contributed to a sense of ubiquity. The protests were polarizing from the start. While some viewed them as a legitimate form of civil disobedience, or at least as an appropriate means of drawing attention to the failings of climate policy, others questioned their suitability for achieving their goals or rejected them outright due to their radical nature.

While the active or silent sympathizers were in the majority at the beginning and mainly supported the demands for a more ambitious climate policy, the societal mood changed with the increasing duration and intensity of the protests and their continued omnipresence in the media. The initial support among the population began to wane, leading to a general decline in acceptance. In the public eye, the forms and goals of the Last Generation protests appeared to be increasingly incoherent and inadequate, which in turn led to a questioning of their broader purpose. Repeated protests led to a perception, conveyed by media coverage, of public fatigue and increasing anger. A narrative gained widespread traction that, despite their laudable goals, the protests were inappropriate and ineffective, further weakening public support. Amidst the growing social unrest, violent clashes began occurring between demonstrators and individuals whose daily lives were affected by the protests. In combination with coercive state measures against protesters, such events reinforced the public's perception of transformative politics as radical and a potential threat to social cohesion and peace (Sprengholz and Meier, 2024). The Last Generation recognized the erosion of support and eventually adjusted its strategy. However, the initial impact of their politicization efforts had already contributed to a significant strain on the transformation process undermining public support for sustainable transformations.

In sum, the case of the Last Generation in Germany is an example of how politicization, while aiming to drive transformative change, can inadvertently lead to a strain on the very change it seeks to promote. This highlights the importance of coherent strategies, and the potential risks associated with attention-grabbing and highly polarizing activism in achieving long-term sustainability goals.

The consequences of silent politics: severed transformation

Under certain conditions, the quest for new or alternative modes of transformation—and their translation into policy instruments—can be driven almost exclusively by government elites, civil servants, lobbyists, or scientific experts. These actors operate within the upper echelons and arcane areas of governments, the ministerial apparatus, agencies, think tanks, and advisory commissions. Even in these relatively “hidden” spaces, policy discussions can be highly contentious, as actors have very different ideas about the goals, means, and target groups of transformative change. In such closed circles, politicization may gain some momentum and even lead to far-reaching decisions on how to advance transformative action. However, as long as these dynamics remain confined to expert forums and receive little public or media attention, they remain silent. This mode of “silent politicization” (Zürn, 2018) can nonetheless have an impact on policies of ecological change, climate mitigation, or sustainable development. At some point, if the key actors in silent politics reach an agreement and make collectively binding decisions, they can significantly change the complex corpus of environmental laws, regulations, assessments, and standards.

This dynamic can be observed in the 2023 amendment of the Buildings Energy Act (Gebäudeenergiegesetz, GEG), which became a central topic of political debate in Germany (Braungardt et al., 2024). The impetus for the GEG amendment was the energy crisis triggered by the Russian war against Ukraine, which progressive forces within the Ministry of Economic Affairs, under the leadership of the Green Party, viewed as a strategic opportunity to accelerate the country's energy transition. These actors were seeking to expedite the transition from fossil fuel-based heating systems to renewable technologies, particularly heat pumps, as part of a broader energy transformation.

The draft bill, prepared by the Ministry of Economic Affairs, faced significant resistance during the interministerial coordination stage. Initially, the politicization of the issue remained confined to bureaucratic circles and the arcane sphere of ministerial governance, where it was managed through established processes of conflict resolution. In the case of the GEG, however, this silent politicization rapidly transformed into a highly public and contentious debate after a draft of the policy proposal was leaked to the media. What had been a regular bureaucratic coordination process now unfolded in the public arena as an emotionally charged, polarized debate on transformation policy. While government officials underscored the importance of the GEG amendment for ensuring energy security and achieving national climate goals, substantial opposition emerged, fuelled by public discontent. Critics framed the amendment as emblematic of an elitist eco-agenda that disregards or even ignores broader societal concerns about economic constraints, social justice, and individual freedoms. The law, still in draft form, was portrayed as imposing significant social burdens, thereby eroding public trust and undermining the legitimacy of environmental and energy policy initiatives (Braungardt et al., 2024).

Consequently, the GEG came to symbolize an environmental transformation project tainted by accusations of elitism and disconnection from societal realities. Underlying is a decoupling between different spheres and dynamics of politicization. The transformation elites and government actors, who may be deeply convinced of the necessity to drive transformation, are missing the opportunity to systematically coordinate their efforts with the broader sphere of policy and civil society actors, including preparing for a controlled escalation of politicization dynamics in the media and the public (Haas et al., 2025). The result is a severed transformation that only reaches very select parts and structures of society.

Pretending to change: the politics of shallow transformation

While the above patterns of transformation refer to processes of politicization affecting the dynamics of transformation processes, “shallowing” concerns the quality of transformation. Shallowing involves a flattening of the depth of transformation, i.e., a reorientation from fundamental system change to a mere adaptation within existing practices. Instead of addressing the systemic roots of unsustainability, transformation remains limited to superficial changes in the lifeworld (Hausknost, 2020).

Approaches to making sustainability-oriented changes in people's lifeworlds through sustainability standards, labels, and other means are present in numerous areas, including food, clothing, and mobility. The assumption is that such approaches induce increased awareness and value shifts, which in turn lead to behavioral changes toward more sustainable practices in virtually all fields of people's everyday lives (Dubois et al., 2019; Moberg et al., 2019). Yet, the quasi-ubiquitous politicization of individual behavior related to sustainability may lead to a shallow transformation only. Two sub-processes are decisive for this. Firstly, sustainability, due to its “compelling attractiveness” to virtually all areas of social action, has become “hegemonic” in society (Blühdorn, 2016). In terms of politicization, this means that potentially all areas of society are becoming recognized as important fields of action to pursue sustainability transformation. Secondly, with the emergence of a new political-epistemic regime of behavioralism (Straßheim, 2020), the focus of sustainability transformation is increasingly directed at individuals and their behavior. The “little things” of everyday life are being politicized in the face of omnipresent sustainability norms and expectations. Waste separation, water consumption, mobility, and other activities—almost every aspect is scrutinized and evaluated in terms of its sustainability implications. People are constantly made aware of the sustainability impacts and side effects of their behavior and are made responsible for them. Behavioral public policies offer a range of tools for micro-level interventions, including green incentives and green nudges, designed to reduce food waste, prevent littering, and conserve energy and water, among other objectives. Such behavioral policies focus attention on the individual, who is assigned responsibility for making transformations happen. While the contribution of individual action to sustainability progress in society is undeniable, the situation of permanent politicization of all areas of societal life can lead to transformation fatigue. People lose their appetite for changing actions and increasingly perceive transformation as a treadmill.

At the same time, the focus on individual and lifeworld change also means that alternative policy interventions in institutions and infrastructures beyond the behavioral dimension—arguably the “big points” of sustainability transformation—are systematically neglected and replaced by those that rely primarily on the results of behavioral experiments. Moreover, a permanently “nudged” society loses the ability to deliberate about profound changes (Bornemann and Burger, 2019).

Ultimately, the societal omnipresence of sustainability and the associated politicization of individuals and their behavior through behavioral interventions may lead to a flattening of transformation. In the long run, this then causes the exhaustion of the sustainability transformation project and the loss of its former appeal (Blühdorn, 2016). The grueling eco-politics of small things and everyday actions profoundly weaken both the capacity and the hope that a more encompassing, structural change is still possible.

The big illusion: politicization simulating transformation

A related mechanism is the simulation of transformation through politicization. Instead of effectively initiating a process of profound societal change, politicization can create the illusion of transformation. It promotes self-deception about society's willingness and ability to transform. Such a mechanism is particularly evident in participatory approaches to sustainability governance. In the context of sustainability-oriented transformation processes, there have been repeated calls for more intensive and comprehensive participation by citizens and stakeholders. Involving citizens and stakeholders would make it possible to understand (un)sustainability problems more comprehensively and to take into account a broader range of perspectives, ideas, and concerns when developing solutions (Meadowcroft, 2004; Lidskog and Elander, 2007). The expansion of participation opportunities comes with the potential to question and open up entrenched cognitive beliefs and normative orientations. Indeed, participation has become a central element of sustainability governance arrangements in many places, lending these arrangements a political quality (Fischer, 2017). Critical voices have, however, long pointed to the lack of impact of participatory arrangements (Oels, 2003). In particular, stakeholder processes can remain inadequate in many respects—for example, when they primarily reproduce established positions and interests. Other observers emphasize that the impact of participation depends on specific contextual conditions and design features, arguing for a differentiated assessment (Cattino and Reckien, 2021; Pickering et al., 2022; Jager and Newig, 2024). Following this nuanced position, certain forms of participation may lead to a politicization mode that merely simulates transformation. In these cases, politicization fosters the collective illusion of profound change without actual change occurring.

A relevant example is the Citizens' Councils on Food that took place in Switzerland in 2022 (Bürger:innenrat für Ernährungspolitik, 2023). Organized under the banner “Dialogues on the future of food in Switzerland,” these platforms brought together citizens to develop solutions for a more sustainable food system. Over 80 randomly selected citizens engaged in the process and developed a comprehensive set of actions. While the initiative was organized by various civil society groups, its connection to formal political processes was tenuous from the start. The creation of the Citizens' Council signaled a form of politicization intended to disrupt entrenched narratives and policy approaches surrounding food sustainability. However, because the forum remained detached from institutionalized decision-making processes, its practical impact was limited. The goals and actions developed in the citizen dialogues merely created an illusion of progress, fostering a false sense of accomplishment among participants and the public. This illusion arguably delayed the implementation of the actions needed to drive meaningful change.

The example suggests that politicization can lead to simulated transformation, especially when several conditions coincide. First, the “politicization” of issues in stakeholder dialogues was not particularly visible in public discourse, which meant that the pressure on policymakers to consider the outcomes of the dialogues was limited. The creation of dialogues as a separate public space, disconnected from actual political decision-making processes, further weakened their political traction. In addition, the limited participation options for societal actors created an impression of non-inclusive and undemocratic participation. Another contributing factor was the procedural taming of controversy: contentious topics were often softened or neutralized through dialogue formats that prioritized consensus and civility over confrontation. As a result, polarization was low, and truly transformative debates failed to emerge. Ultimately, the positions and concerns expressed remained ineffective. This not only produced a materially simulated transformation but can over time also contribute to the erosion of trust and weakening of future transformation efforts.

When the public comes to realize that participatory processes do not result in real policy changes, trust in those processes—and in the institutions behind them—beings to erode. Actors involved are often left disappointed and disillusioned when their contributions are not reflected in actual decisions. The resources spent in organizing and implementing these processes are perceived as wasted. This disillusionment undermines future efforts to mobilize social actors to participate in such processes, thereby undermining their overall legitimacy. It also fuels the populist narratives of an elite-dominated political system that is unwilling to change—a system that merely stages participation and pretends to consider the people's will. Some scholars argue, however, that simulated transformation is not just a strategic failure but a symptom of a deeply disillusioned society in which both elites and citizens willingly engage in illusionary activities as a way of coping with the unresolved contradictions of unsustainability (Blühdorn, 2016).

From obstruction to opportunity? Toward more politically reflexive transformation strategies

Since the 1990s, politicization—through social movement mobilization and parliamentarization of environmental discourse—has been essential to countering scientistic and technocratic tendencies in sustainability governance, thereby contributing to environmentally-oriented social change. However, our analysis reveals that politicization can also have various negative effects on sustainability transformations. Under certain conditions, politicization may fuel societal counter-movements, resulting in a stalemate situation (stalling); it may slow down transformation efforts by exhausting the public (straining); it may drive a wedge between progressive transformation elites and the larger public (severing); it may hollow out existing transformation efforts by putting pressure on everyday practices without addressing deeper structural problems (shallowing); or it may foster collective self-deception about society's willingness and ability to transform (simulating). In the following, we reflect on these key findings of our analysis by exploring the links between the different forms and mechanisms of politicization and discuss their practical implications for advancing transformation efforts.

Our analysis identifies several mechanisms of politicization that negatively affect sustainability transformations. These mechanisms do not operate in isolation but are often interrelated and influence each other over time. For example, politicization that places strain on transformation efforts can develop into a shallowing of transformation, diverting attention from the structural causes of unsustainability. Similarly, politicization that simulates transformation—by creating the illusion of deep change without actual transformation—can ultimately lead to a stalling of transformation, as the lack of real progress demotivates actors and hinders further efforts to change. Understanding how these mechanisms interact is crucial, as they often form chains of obstruction. In these chains, initial hopes for transformation may gradually give way to fatigue, resistance, or counter-mobilization, each compounding the barriers to change. A dynamic of obstruction might, for example, begin with shallowness or simulation and gradually lead to stalling. Unraveling these chains is essential for breaking the negative dynamics that prevent sustainability transformations from building momentum or achieving deeper structural change.

To this end, our analysis suggests several practical strategies for addressing and counteracting the negative effects of politicization on transformation. One key strategy is to overcome the polarization among actors that often fuels obstructive forms of politicization. For transformation to succeed, it is crucial to build coalitions that involve all relevant actors. These include not only actors advocating for change but also those who feel threatened, marginalized or positioned as potential losers, e.g., in sectors under economic pressure or from communities particularly affected by transformation processes. Promoting dialogue and inclusive decision-making can help redirect politicization into a more constructive force that enables transformation rather than impedes it. Community-based transition councils and co-design approaches in energy and food transitions provide promising models in this regard (e.g., Pickering et al., 2022).

A concrete example of a strategy aimed at building socio-spatial networks and connecting diverse stakeholders is the Post-Fossil City Contest (PFCC), organized by the Urban Futures Studio (Hajer and Versteeg, 2019; see also postfossil.city). The PFCC invited participants to develop imaginative visions of a post-fossil future. From 250 submissions worldwide, ten were selected, curated, and exhibited at Utrecht City Hall. The winner, chosen by a jury of national and municipal policymakers, designed a boundary object that traveled between cities, helping to shape discourses on post-fuel cities. Under certain conditions, similar strategies of “anticipatory governance” and futuring exercises have demonstrated integrative and mobilizing potential for transformation (Muiderman et al., 2022). In parallel, counter-politicization strategies can play a crucial role in challenging the narratives that hinder transformation. These approaches seek to bring to light the issues and concerns that negative politicization tends to ignore or obscure, such as the long-term benefits of transformation for marginalized communities and the broader social and environmental gains. By reframing the conversation and highlighting these previously disregarded dimensions, it may become possible to shift the tide of politicization from obstruction to support for deeper transformation.

Conclusion

Politicization and transformation are complex societal dynamics, connected in multiple and often contradictory ways. Politicization can either function as a catalyst for transformation—by questioning established practices, challenging structures and existing power relations, mobilizing actors, and creating contingencies that set off transformative change. This is the hopeful interpretation of politicization as an engine of transformation. Or politicization can have transformation-inhibiting effects—by stalling, straining, severing, shallowing, simulating, or otherwise undermining transformative efforts. By identifying and illustrating these mechanisms, our analysis contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the ambivalent role politicization plays in sustainability transformations. Hence, while often regarded as a necessary driver of change, politicization can also undermine transformation processes in various ways. In highlighting this dual character, we aim to contribute to a more reflexive approach to navigating the relationship between politicization and transformation. Such an approach requires the careful design of inclusive governance arrangements that recognize, anticipate, and counteract negative politicization dynamics (Fischer, 2017; Pickering et al., 2022; Scoones et al., 2020).

The findings of our analysis suggest the need for further research that systematically examines the reciprocal dynamics between politicization and transformation. The five mechanisms we identify as ways in which politicization can hinder transformation are neither exhaustive nor yet fully understood. A key direction for future research is to further substantiate, differentiate, and expand the mechanisms through which politicization affects transformation. This could include empirical studies that test and contextualize the conceptual insights offered here in different sectors, such as energy, agri-food systems, or transportation, to examine how politicization trajectories unfold in these fields. While the focus of our empirical examples was on Germany and Switzerland, there is a clear need to analyze how the politicization-transformation dynamics play out in other political contexts, including in countries with developed democracies and more autocratic regimes. In other contexts, the forms of politicization, as well as the transformation pathways, may differ significantly. Comparative analyses—across sectors, countries, and political regimes—could shed light on the different forms of politicization, helping to identify recurring patterns of politicization as well as context-specific dynamics.

In addition, future research should examine longer and more extensive episodes of politicization to understand better how these dynamics unfold over time. Different mechanisms may typically follow or reinforce one another, creating chains of obstruction that must be carefully traced and unpacked. Furthermore, comparative studies of different types of politicization—across national, sectoral, or local contexts—could help determine whether the negative dynamics we have identified are more systematic or context-dependent. For example, recent studies have shown how politicization without meaningful transformation can shape discourses that travel across geographical and political boundaries, influencing both democratic and authoritarian regimes alike (Kythreotis, 2023). A deeper understanding of all these processes is a prerequisite for addressing the practical challenges of navigating and shaping future sustainable transformations in politicized times.

Author contributions

BB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the publication of this article. We acknowledge the financial support of the Open Access Publication Fund of Bielefeld University for the article processing charge. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abson, D. J., Fischer, J., Leventon, J., Newig, J., Schomerus, T., Vilsmaier, U., et al. (2017). Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 46, 30–39. doi: 10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y

Anshelm, J., and Haikola, S. (2018). Depoliticization, repoliticization, and environmental concerns—Swedish mining politics as an instance of environmental politicization. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 17, 561–596. doi: 10.14288/acme.v17i2.1500

Beck, U. (2010). Climate for change, or how to create a green modernity? Theory Cult. Soc. 27, 254–266. doi: 10.1177/0263276409358729

Blühdorn, I. (2016). “Sustainability—post-sustainability—unsustainability,” in The Oxford Handbook of Environmental Political Theory, eds. T. Gabrielson, C. Hall, J.M. Meyer., and D. Schlosberg (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 259–273.

Blühdorn, I. (2022). Liberation and limitation: emancipatory politics, socio-ecological transformation and the grammar of the autocratic-authoritarian turn. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 25, 26–52. doi: 10.1177/13684310211027088

Bornemann, B., and Burger, P. (2019). “Nudging to sustainability? Critical reflections on nudging from a theoretically informed sustainability perspective,” in Handbook of Behavioural Change and Public Policy, eds. H. Straßheim and S. Beck (Cheltenham, UK/Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar), 209–226.

Braungardt, S., Keimeyer, F., and Loschke, C. (2024). “Is the “heating hammer' hitting energy efficiency policy?—Learnings from the debate around the German buildings energy act,” in ECEEE Summer Study Proceedings. Available at: https://www.oeko.de/en/publications/translate-to-english-is-the-heating-hammer-hitting-energy-efficiency-policy-learnings-from-the-debate-around-the-german-buildings-energy-act/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (Accessed May 23, 2025).

Bürger:innenrat für Ernährungspolitik (2023). Empfehlungen für die Schweizer Ernährungspolitik. Abschlussbericht. Available at: https://www.buergerinnenrat.ch/de/jetzt-wird-aufgetischt/ (Accessed November 1, 2024).

Cattino, M., and Reckien, D. (2021). Does public participation lead to more ambitious and transformative local climate change planning? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 52, 100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2021.08.004

de Wilde, P., Leupold, A., and Schmidtke, H. (2016). Introduction: the differentiated politicisation of European governance. West Eur. Polit. 39, 3–22. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1081505

Dubois, G., Sovacool, B., Aall, C., Nilsson, M., Barbier, C., Herrmann, A., et al. (2019). It starts at home? Climate policies targeting household consumption and behavioral decisions are key to low-carbon futures. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 52, 144–158. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2019.02.001

Fischer, F. (2017). Climate Crisis and the Democratic Prospect: Participatory Governance in Sustainable Communities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flügel-Martinsen, O. (2020). Transformations of the struggle for social and political rights: democratic politics of contestation in a post-republican era. Soc. Work Soc. 18, 1–8.

Ginsberg, B. (2024). The Dark Side of Politics. Essays on the Unpleasant Realities of Political Life. New York/Oxon: Routledge.

Haas, T., Sander, H., Fünfgeld, A., and Mey, F. (2025). Climate obstruction at work: right-wing populism and the German heating law. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 123:104034. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2025.104034

Hajer, M., and Versteeg, W. (2019). Imagining the post-fossil city: Why is it so difficult to think of new possible worlds? Territ. Polit. Gov. 7, 122–134. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2018.1510339

Hällmark, K. (2023). Politicization after the “end of nature': the prospect of ecomodernism. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 26, 48–66. doi: 10.1177/13684310221103759

Hausknost, D. (2020). The environmental state and the glass ceiling of transformation. Environ. Polit. 29, 17–37. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2019.1680062

Horcea-Milcu, A-. I., Dorresteijn, I., Leventon, J., Stojanovic, M., Lam, D. P. M., Lang, D. J., et al. (2024). Transformative research for sustainability: characteristics, tensions, and moving forward. Glob. Sustain. 7:e14. doi: 10.1017/sus.2024.12

Jäger, A. (2023). Hyperpolitik. Extreme Politisierung ohne politische Folgen. Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Jager, N. W., and Newig, J. (2024). “What explains the performance of participatory governance?,” in Pathways to Positive Public Administration, eds. P. Lucas et al. (Cheltenham/Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar), 165–186.

Kythreotis, A. P. (2023). The paradoxical (post-)politics of scale: exploring authoritarian state environmental policymaking in Brunei. Territ. Polit. Gov. 11, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2023.2262508

Laclau, E., and Mouffe, C. (2001). Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics (2nd Edn.). Brooklyn: Verso.

Lederer, M., Lasso Mena, V., Marquardt, J., Richter, T. A., and Schoppek, D. E. (2024). Radical climate movements—Is the hype about “eco-terrorism' analogy, warning or propaganda? Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1421523. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1421523

Lidskog, R., and Elander, I. (2007). Representation, participation or deliberation? Democratic responses to the environmental challenge. Space Polity 11, 75–94. doi: 10.1080/13562570701406634

Linnér, B-. O., and Wibeck, V. (2020). Conceptualising variations in societal transformations towards sustainability. Environ. Sci. Policy 106, 221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.01.007

Mahajan, G. (2009). Reconsidering the private-public distinction. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Polit. Philos. 12, 133–143. doi: 10.1080/13698230902891970

Meadowcroft, J. (2004). “Participation and sustainable development: modes of citizen, community and organisational involvement,” in Governance for Sustainable Development: The Challenge of Adapting Form to Function, ed. W.M. Lafferty (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 162–190.

Meadowcroft, J. (2007). Who's in charge here? Governance for sustainable development in a complex world. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 9, 299–314. doi: 10.1080/15239080701631544

Moberg, K. R., Aall, C., Dorner, F., Reimerson, E., Ceron, J-. P., Sköld, B., et al. (2019). Mobility, food and housing: responsibility, individual consumption and demand-side policies in European deep decarbonisation pathways. Energy Eff. 12, 497–519. doi: 10.1007/s12053-018-9708-7

Muiderman, K., Zurek, M., Vervoort, J., Gupta, A., Hasnain, S., Driessen, P., et al. (2022). The anticipatory governance of sustainability transformations: hybrid approaches and dominant perspectives. Global Environ. Change 73:102452. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102452

Norgaard, R. B. (1995). Beyond materialism: A co-evolutionary reinterpretation of the environmental crisis. Rev. Soc. Econ. 53, 475–492. doi: 10.1080/00346769500000014

Norgaard, R. B. (2006). Development Betrayed: The End of Progress and a Co-Evolutionary Revisioning of the Future. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203012406

O'Brien, K. L. (2012). Global environmental change II: From adaptation to deliberate transformation. Progr. Hum. Geogr. 36, 667–676. doi: 10.1177/0309132511425767

Oels, A. (2003). Evaluating Stakeholder Participation in the Transition to Sustainable Development: Methodology, Case Studies, Policy Implications. Münster: Lit.

Patterson, J., Schulz, K., Vervoort, J., van der Hel, S., Widerberg, O., Adler, C., et al. (2017). Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 24, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2016.09.001

Pavenstädt, C. N. (2024). Another world is possible? Climate movements' bounded politicization between science and politics. Front. Pol. Sci. 6, 1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1410833

Pepermans, Y., and Maeseele, P. (2016). The politicization of climate change: problem or solution? WIREs Clim. Change 7, 478–485. doi: 10.1002/wcc.405

Pickering, J., Hickmann, T., Bäckstrand, K., Kalfagianni, A., Bloomfield, M., Mert, A., et al. (2022). Democratising sustainability transformations: assessing the transformative potential of democratic practices in environmental governance. Earth Syst. Govern. 11:100131. doi: 10.1016/j.esg.2021.100131

Politico (2024). Farmer Protest. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/tag/farmer-protest/ (Accessed October 28, 2024).

Scoones, I., Newell, P., and Leach, M. (2015). “The politics of green transformations,” in The Politics of Green Transformations, eds. I. Scoones, M. Leach, and P. Newell (Routledge), 1–21.

Scoones, I., Stirling, A., Abrol, D., et al. (2020). Transformations to sustainability: Combining structural, systemic and enabling approaches. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 42, 65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.12.004

Sommer, B., and Schad, M. (2022). Sozial-ökologische Transformationskonflikte. Konturen eines Forschungsfeldes. ZfP Zeitschrift für Politik 69, 451–468. doi: 10.5771/0044-3360-2022-4-451

Sprengholz, P., and Meier, V. T. (2024). Radical climate movements: Associations between government response and public support. Environ. Behav. 56, 3–18. doi: 10.1177/00139165241272468

Straßheim, H. (2020). De-biasing democracy. Behavioural public policy and the post-democratic turn. Democratization 27, 461–476. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2019.1663501

Swyngedouw, E. (2011). Depoliticized environments: the end of nature, climate change and the post-political condition. R. Inst. Philos. Suppl. 69, 253–274. doi: 10.1017/S1358246111000300

Swyngedouw, E. (2015). The non-political politics of climate change. ACME Int J Crit Geograph. 12, 1–8. doi: 10.14288/acme.v12i1.948

The Guardian (2024). Thousands of Tractors Block Berlin as Farmers Protest Over Fuel Subsidy Cuts. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/jan/15/thousands-tractors-block-berlin-farmers-protest-fuel-subsidy-cuts (accessed October 28, 2024).

Walker, R. B. J., Shilliam, R., Weber, H., and Plessis, G. D. (2018). Collective discussion: diagnosing the present. Int. Polit. Sociol. 12, 88–107. doi: 10.1093/ips/olx022

Wiesner, C., (ed.). (2021). Rethinking Politicisation in Politics, Sociology and International Relations. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wilson, J., and Swyngedouw, E. (2014). “Seeds of dystopia: Post-politics and the return of the political,” in The Post-Political and Its Discontents: Spaces of Depoliticization, Spectres of Radical Politics, eds. J. Wilson and E. Swyngedouw (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 1–22.

Keywords: politicization, transformation, sustainability, barriers to change, political dynamics

Citation: Bornemann B, Strassheim H and Weiland S (2025) Stalling, straining, severing, shallowing, simulating: how politicization can negatively affect sustainability transformation. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1524566. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1524566

Received: 07 November 2024; Accepted: 07 July 2025;

Published: 07 August 2025.

Edited by:

Stylianos Ioannis Tzagkarakis, Hellenic Open University, GreeceReviewed by:

Andrew Paul Kythreotis, University of Lincoln, United KingdomVeronica Brodén Gyberg, Linköping University, Sweden

Copyright © 2025 Bornemann, Strassheim and Weiland. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Holger Strassheim, aG9sZ2VyLnN0cmFzc2hlaW1AdW5pLWJpZWxlZmVsZC5kZQ==

Basil Bornemann

Basil Bornemann Holger Strassheim

Holger Strassheim Sabine Weiland

Sabine Weiland