- 1Department of Economics, Democritus University of Thrace, Komotini, Greece

- 2Knowledge Management, Innovation and Strategy Center (KISC), University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

- 3School of Business, University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

This integrative review examines the evolving landscape of globalization, aiming to understand the possible paths of the emerging global order. In a world marked by historical shifts, the research identifies three main paths: New Nation-Centric Fragmentation, New Multipolarity, and New Realistic and Innovative Global Liberalism. The last path looks most promising yet, regrettably, that prospect is fading as a driving force in today’s landscape—despite its promise of solid geopolitical stability, brisk economic growth, and vigorous technological progress. Recent global shifts, however, make such an outcome look increasingly remote.

1 Introduction

In an era marked by rapid global transformations and the unsettling challenges of the 21st century, we find ourselves standing at a critical juncture of historical evolution. As the previous phase of globalization recedes, yielding to what many scholars denote as a new phase of globalization, there is a pressing need to understand the nature and potential trajectories of this emerging global order (Baldwin, 2016; Nobis, 2017; Wang, 2020). This paper aims to shed light on the character of the new globalization, its potential trajectories, and the context required to navigate these uncharted waters, while fostering a global innovative liberalism.

The term “globalization” has historically conjured images of an interconnected world—a network of nations linked by economics, politics, and technology. While the process has integrated markets, reduced the costs of communication, and led to unprecedented technological advancements, it has not been without its challenges and contradictions. The last decade has seen growing sentiments of nationalism, mounting trade tensions, and questions about the very benefits of globalization. We therefore see a new phase of globalization that combines past lessons with future prospects (Marinova, 2020; Rodrik, 2011; Wang, 2020).

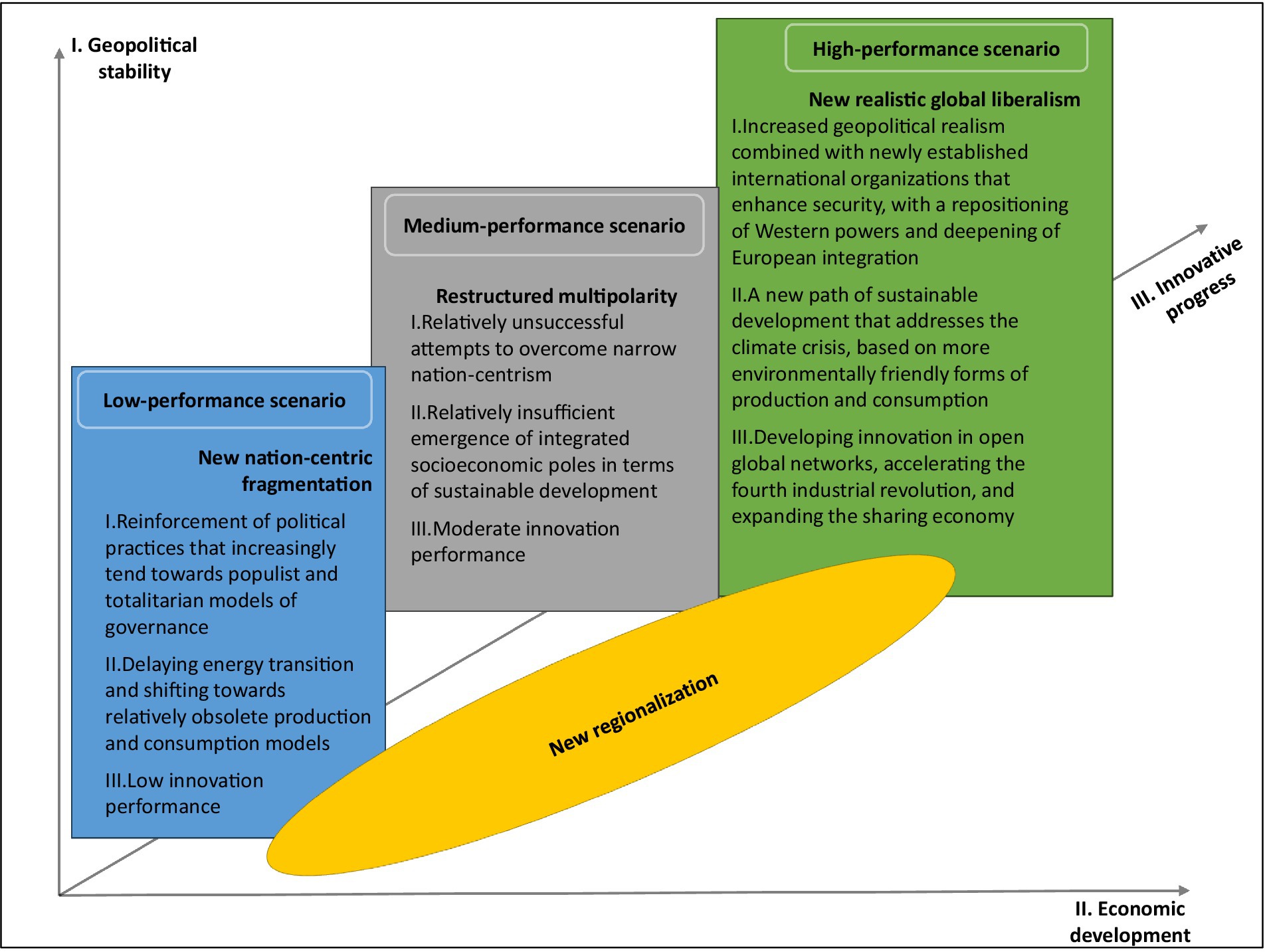

Drawing inspiration from the “evolutionary structural triptych” approach that spans geopolitical stability, economic development, and innovative progress (Chatzinikolaou and Vlados, 2023; Vlados, 2019), this study seeks to map the potential trajectories of the emerging globalization. As Strohmer et al. (2020) posited, this era resembles “Globalization 3.0” concept, wherein we observe a blend of high geopolitical stability, economic development oriented toward sustainable models, and breakthroughs in open innovation.

Despite the vast body of literature dedicated to understanding globalization, there remains a pressing need to decipher the emerging nuances of this new phase. Furthermore, as the world teeters between nation-centric fragmentation and a renewed global liberalism, understanding the potential futures of globalization becomes imperative.

• Question 1: What could be the possible futures for the emerging new globalization?

• Question 2: In what context could we understand this emerging new reality in order to drive toward a new global innovative liberalism?

We identify three possible paths for future globalization, from a revival of nation-centric fragmentation to a promising era marked by a “realistic and innovative liberalism.” Within this spectrum, we stress the importance of regionalization as an enduring theme and the need for a renewed liberal approach to foster sustainable global development.

Following this introduction, Section 2 dives into a comprehensive literature review, grounding our exploration in existing research. Section 3 then sets out the integrative-review methodology that underpins the study. In Section 4, we unveil our findings, detailing the scenarios for the new globalization and pondering the potential of a new realistic global liberalism. Finally, Section 5 consolidates our discoveries into a coherent conclusion, providing insights into the possible futures of this evolving phenomenon and charting out avenues for future research.

2 Literature review

We posit that the ongoing crisis serves as a transitional phase toward the system succeeding globalization—a yet-to-emerge global order (Baldwin, 2016; Nobis, 2017; Vlados and Chatzinikolaou, 2022). This perspective adds depth to the emerging reality as it views the upcoming system as a “new globalization,” irrespective of the regression or advancement of certain social and economic trends. We anticipate that the future global system will also represent a “new globalization,” albeit with distinct parameters and dynamics than the earlier globalization era (Tooze, 2021). Additionally, the consecutive crises post-2008 have served as catalysts, hastening the evolution of this “new global era” across various functional dimensions, such as the surge in remote work, e-commerce, and online education (Bonilla-Molina, 2020). Additionally, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine seems to radically reshape the previous balances, especially accelerating the global energy transition (Bricout et al., 2022).

The evolving global system will not emerge from a “blank slate.” Contrary to “de-globalization” narratives, we assertively do not foresee an end to globalization (Van Bergeijk, 2019; Williamson, 2021). Such a notion feels void, akin to suggesting a “de-capitalism” following capitalism – clearly a misnomer and ahistorical in our viewpoint.

Post the proliferation of the fourth industrial revolution, we forecast the global system will represent a reoriented globalized capitalism. However, this phase of capitalism will have differing dominant players and a distinct global “geometry” from its predecessor (Schwab, 2016). Yet, this “post-globalization” era remains shrouded in uncertainty, predominantly characterized by unresolved dialectical tensions awaiting synthesis.

Complementing these largely Western-centered accounts, a vibrant corpus of Global-South scholarship interrogates the power asymmetries built into global capitalism and proposes alternative imaginaries for a “new globalization.” Some highlight the emergence of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) as evidence of a home-grown, post-neoliberal regionalism that re-centers developmental sovereignty (Carmody, 2019; Leshoele, 2023). Others critique Euro-American universalism and advocate a relational, tianxia-inspired multipolarity (Hui, 2016; Qin, 2016), while Indian economist Ghosh (2022) calls for a “developmental multilateralism” that embeds labor rights and climate justice at the core of global governance.

In this context, the perspective presented by Strohmer et al. (2020) is one of the most comprehensive for understanding the new emerging global reality. They suggest that the global system is at a crossroads with four divergent futures: Globalization 3.0, Polarization, Islandization, and Commonization.

Strohmer et al. (2020, p. 14) describe various trajectories for the future. In the scenario of “Globalization 3.0” as our destiny, we would return to the heights of economic growth and trade witnessed during the 2000s, before the Great Recession. This would mean stable commodity prices, high prosperity, and a steady progress of information and communication technologies. On the other hand, “Polarization” paints a picture of a world deeply divided by political and economic rivalries, slicing the global economy into competing blocs. The third possibility, “Islandization,” speaks of a resurgence of nationalism in major economies that could introduce stringent protectionist measures, causing a decline in economic transactions. The final trajectory, “Commonization,” presents a radical break from the past, heralding the rise of a new global collectivism fueled by the spread of additive manufacturing and the sharing economy. In this landscape, millennials, many of whom are guided by altruistic motives, would take the lead in political decisions and consumption patterns. Interestingly, the foundational concept for these trajectories came from Laudicina and Peterson (2016), under the Global Business Policy Council at ATKearney. Strohmer and his colleagues further delved into these ideas in a dedicated chapter in 2020.

3 Methodology

Guided by integrative-review methodology, we conceived this literature synthesis as a conceptual-innovation exercise that moves beyond description to construct a new analytical framework for the “new globalization.” Following Snyder’s four-phase model—design, conduct, analysis, and reporting—we selected sources creatively yet transparently, with an explicit focus on theory building (Snyder, 2019). Torraco (2016) likewise defines an integrative review as research that critiques and synthesizes representative studies so that fresh theoretical insights can emerge. In line with these principles, we first cataloged all foundational literature on the emerging phase of globalization. We then identified the scenarios proposed by Strohmer et al. (2020) as particularly actionable, while noting that their bidimensional schema required extension to a tridimensional perspective to capture the full complexity of the phenomenon bringing to the forefront—and weaving into the analysis—the innovation dimension, an axis that is steadily becoming crucial for interpreting these dynamics. As the next sections will demonstrate, recent global developments reinforced the validity of this expanded approach. Consequently, our re-integration of the examined literature situates the resulting globalization scenarios within a broader, theory-driven map of the emerging global order.

4 Results

4.1 Scenarios for the new globalization

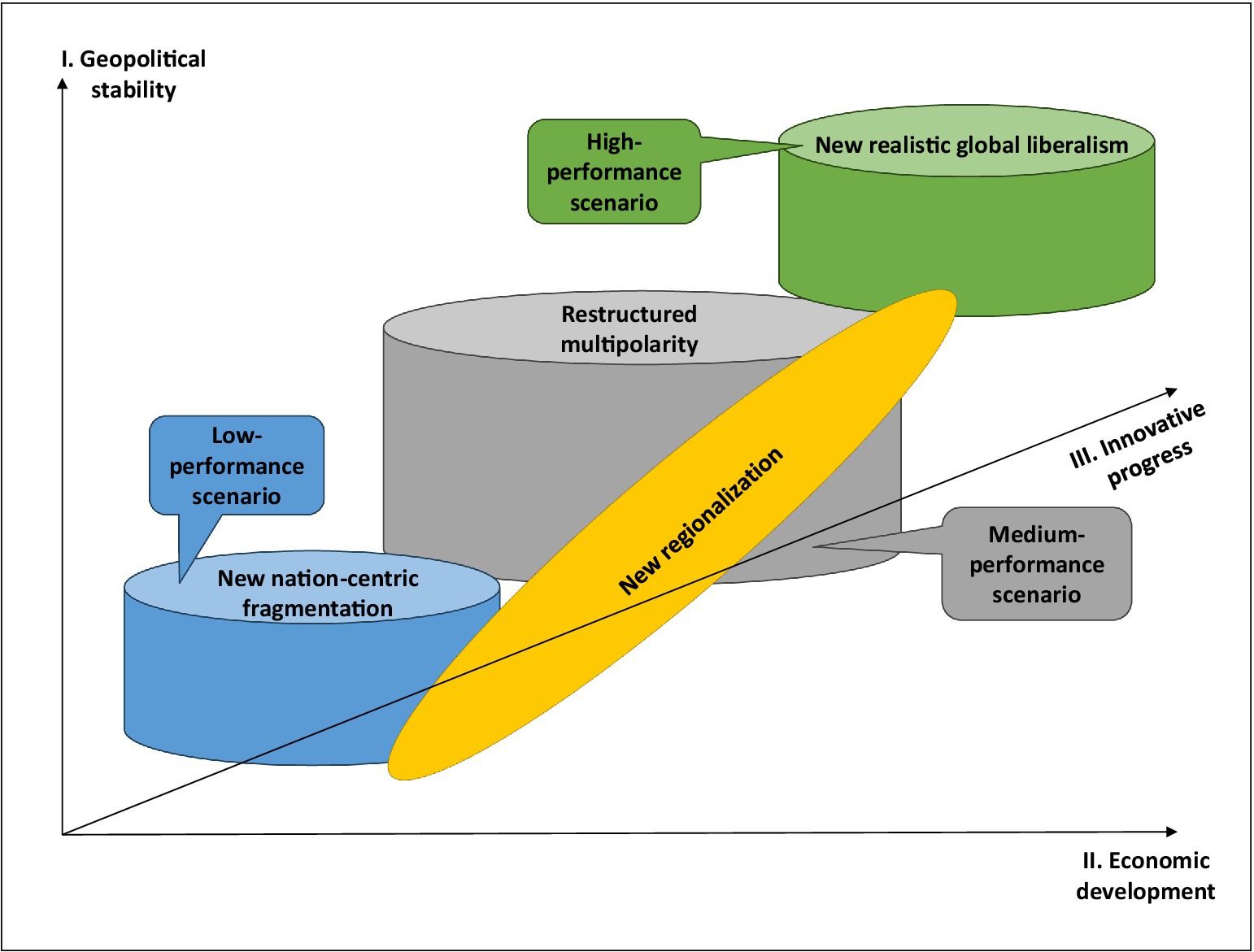

Drawing from the approach by Strohmer et al. (2020), we introduce a three-dimensional categorization of potential scenarios based on the evolutionary structural triptych of the global economy. This categorization integrates the dimensions of politics, economics, and technology-innovation to elucidate the phases of global capitalism. In contrast, Strohmer et al. (2020) focused on two dimensions: geopolitical cohesion and economic growth. Our findings indicate that we are currently entering a new phase of globalization, following the structural maturation of the previous phase (Chatzinikolaou and Vlados, 2023; Vlados, 2019). The triptych, a tool for mapping global equilibria over different periods, considers geopolitical stability, economic development, and innovative progress (Figure 1). Within this framework, the future offers various scenarios, categorized into “zones” based on low, medium, or high performance across these dimensions.

Figure 1. The “evolutionary structural triptych” blends geopolitical stability, economic development, and innovation.

Under a pessimistic lens, the new globalization may give rise to nation-centric fragmentation. Here, a predominantly insular perspective would pervade geopolitical, developmental, and innovation standpoints, laying foundations for robust protectionist forces, fostering national cultural autonomy, and strengthening political shifts toward populist and authoritarian governance. This shift toward nation-centric fragmentation aligns in part with the concept of “Islandization” (Strohmer et al., 2020), potentially resurrecting international regulatory practices reminiscent of the interwar years (Cornell et al., 2020).

In contrast, the medium-performance zone depicts a more optimistic landscape where the hallmark of “new globalization” is a rebirth of multipolarity. It’s pertinent to note Vasconcelos’s (2008) assertion that multipolarity heralds the rise of diverse global actors, like the BRICS, which incrementally challenge the dominance of existing powerhouses. Supporting this, Papic (2021) delves into the ongoing reshaping of multipolarity, emphasizing the post-2010 shift in geopolitical clout, fostering greater pluralism in international diplomacy.

Thus, scenarios within this medium zone encapsulate balanced performances in geopolitical stability, economic momentum, and global innovative advancement. Conversely, the medium-to-low zone likely encompasses failed efforts to transcend restrictive nation-centric perspectives, lacking harmonized and balanced socioeconomic poles. However, the reshaped multipolarity within the medium-to-upper echelon could promote regional unifications, yielding harmonized global geopolitical equilibrium, socioeconomic progression, and commendable innovative advancements.

The upcoming era hinges significantly on a renewed form of regionalization. As Wang (2020) postulates, this rejuvenated regionalization, rooted in the post-Cold War era, fosters robust inter-regional collaborations, paving the way for economic advancement and affluence. Contrarily, Marinova (2020) emphasizes that this revamped regional integration does not resurrect bygone imperial or bipolar Cold War disparities but rather reflects a seamless transition from preceding global influences.

This fresh wave of peripheral collaboration could engineer novel geopolitical and geoeconomic layouts, culminating in the high-performance scenario termed “new realist global liberalism.” Within this construct, the European Union’s integration trajectory and the expanding alliances within NAFTA, MERCOSUR, and the nascent RCEP could play pivotal roles (Kimura, 2021). Explicitly, this “new realist global liberalism” ethos, aligning with the “Globalization 3.0” concept (Strohmer et al., 2020), encapsulates (Figure 2):

A) High geopolitical stability within the redefined multipolarity, forging strengthened democratic underpinnings through enhanced Western geostrategic partnerships, deeper European amalgamation, and punitive measures against destabilizing nations.

B) High-performance economic development oriented toward novel hybrid post-Fordist structures. These structures blend the flexibility, digitization and networked value chains of post-Fordism with the scalable efficiencies of classic Fordist mass production (Amin, 2011). The result is agile, low-carbon, innovation-led growth that embeds social inclusion and environmental stewardship. This blueprint anticipates a sustainable global economic growth trajectory. It places greater emphasis on green production and consumption models (Zehr, 2015). It also fosters resilient, adaptive and inclusive corporate structures (World Economic Forum, 2018).

C) Innovative accomplishments stemming from an organic, ecosystemic, and open innovation landscape. Here, contemporary enterprises, more akin to biological entities than mechanistic structures (Burns and Stalker, 2011), necessitate competitive advantage self-renewal amidst the dynamic global atmosphere. Such innovation, thriving within expansive global networks, will likely hinge on effective combinations of organizational strategy, technology, and management, propelling the fourth industrial revolution and broadening the sharing economy’s horizons (Vlados et al., 2019).

A core aspect of the evolutionary structural triptych that deserves attention is the symbiotic relationship between the spheres it encompasses. When faced with geopolitical unrest combined with stagnant economic growth, there may not be sufficient resources or potential for profitability to drive strong innovative breakthroughs. This economic stagnation, paired with a lack of innovation momentum, can cause political upheaval within any socioeconomic framework. Such structures might confront issues of poverty and technological stagnation. In these circumstances, it’s difficult for one of the three aspects to progress rapidly while the other two lag, considering their interconnectedness. This mutual influence is apparent in contexts of both moderate and exceptional accomplishments. For example, to achieve top-tier performance, it’s essential to align heightened geopolitical stability with an emerging multipolarity, potentially catalyzing sustainable economic upturn based on intrinsic innovations. It’s worth mentioning that although interdependence is implied in the approach of Strohmer et al. (2020) it’s not overtly defined. Strohmer et al. (2020) do not directly tie the performance areas they delineate to the synergy of the two primary dimensions they scrutinize: geopolitical cohesion and economic growth.

Considering the evolutionary structural triptych and the extant global trajectories, it’s improbable to pinpoint a deterministic future for the burgeoning globalization. Nonetheless, forthcoming developments likely reside within the outlined global performance domains (low, medium, or high). A hybrid globalization scenario comprising disparate performances across the three dimensions appears implausible. As Vlados (2019) also noted, these structural realms manifest co-evolutionarily, interdependent on one another.

Recent analysis of the two largest mega-regional trade accords—the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)—demonstrates how the evolutionary structural triptych can be operationalized in practice (Chatzinikolaou and Vlados, 2024). Both pacts pull the world economy toward the framework’s medium–high performance corridor, yet by different routes: the CPTPP diffuses high-standard rules on labor, environment and digital trade, empowering middle powers and tempering great-power rivalry across the Pacific, whereas the RCEP deepens East-Asian interdependence under ASEAN stewardship and encourages regulatory convergence. Together these cases validate the “new globalization” lens as a useful tool for translating abstract scenario building into concrete assessments of real-world policy instruments and their capacity to foster—or hinder—sustainable, innovative liberalism (Chatzinikolaou and Vlados, 2024).

4.2 Toward a new realistic global liberalism?

Drawing from the evolutionary structural triptych, the “Commonization” scenario posited by Strohmer et al. (2020) seems relatively weak. In an environment characterized by constrained economic growth, effectively addressing climate change, expanding the knowledge economy, and assimilating tools from the fourth industrial revolution appears unattainable. Suboptimal economic outcomes pose a significant challenge to maintaining and amplifying innovative dynamism in socioeconomic systems and achieving geopolitical cohesion and stability. As such, Strohmer et al.’s (2020) scenario, which stems from a “global commons” ethos, may not be pragmatically realized.

Within this context, certain global approaches merit re-evaluation. Notably, most BRICS nations, to date, have pursued hyper-globalization—abolishing virtually all border-related costs and non-cost barriers on the cross-border movement of goods, services, capital, and finance—while fortifying their national sovereignty. This seems at odds with Rodrik’s trilemma which proposes an incompatibility among national sovereignty, democracy, and globalization (Rodrik, 2011). China serves as a clear example, as it has, for the most part, not prioritized the strengthening of democratic institutions (McAllister and White, 2017). In the West, nations like those in the European Union have been gravitating toward embracing globalization and enhancing democratic institutions, while possibly downplaying traditional national sovereignty. Conversely, some nations have bolstered their national and democratic sovereignty by tempering their globalization efforts, leaning toward nation-centric governance and trade protectionism. However, the sustainability of these paths in the new globalization era is questionable (Vlados and Chatzinikolaou, 2022).

Contrary to Rodrik’s trilemma, we advocate for the BRICS—and all nations—to prioritize the development of their democratic institutions, ensuring an emphasis on pluralism and human rights (Vlados and Chatzinikolaou, 2022). Key global players, such as the USA and the EU, must re-assess their stances on national sovereignty while staying receptive to the shifting global economic landscape. Countries that have predominantly emphasized the dichotomy of national sovereignty and democratic institution building should now be more receptive to the new form of globalization.

The tariff shock unleashed by the Trump Administration in early 2025 already offers a live “stress test” for the evolutionary structural triptych (Contractor, 2025). Geopolitically, it pushes the system toward a more confrontational, nation-centric axis; economically, the sudden hike in cross-border costs threatens growth in tightly intertwined supply chains; yet the rapid co-ordination among BRICS states and the tentative North-American renegotiation talks reveal an equally potent centrifugal pull toward a renewed multipolar equilibrium. Predictably, the Trump policy mix has triggered tit-for-tat responses that ratchet up global tensions—political, technological, and economic. Across its interlocking fronts—tariffs, fiscal and monetary tools, migration rules, diplomacy, defense, and energy—the administration is steering the world toward neo-nationalist fragmentation. The result is a sharp shake-up of geopolitical balances, a drag on growth, and a marked erosion of the international networks that generate and spread cutting-edge technology. Whether this friction stabilizes in the lower-performance “fragmentation” zone or is channeled upward into the medium-performance “new multipolarity” corridor will depend on how key actors translate short-term protectionism into longer-term, rules-based reforms that can re-ignite innovation instead of locking the triptych’s three spheres into a retaliatory downward spiral (ABC News, 2025; Dmitracova, 2025).

Interestingly, the current trajectory suggests a convergence of challenges and paths for global entities, leading to a trend of “homogenization,” but within an increasingly heterogeneous and diverse world. In this vein, Fukuyama’s “end of history” proposition (Fukuyama, 1992, p. xi) may be ripe for a revision. Although we do not assert that the emerging “new globalization” signifies an ideological terminus with a universalized western liberal democracy, there’s some merit in Fukuyama’s call for a unified, realistic liberal approach globally.

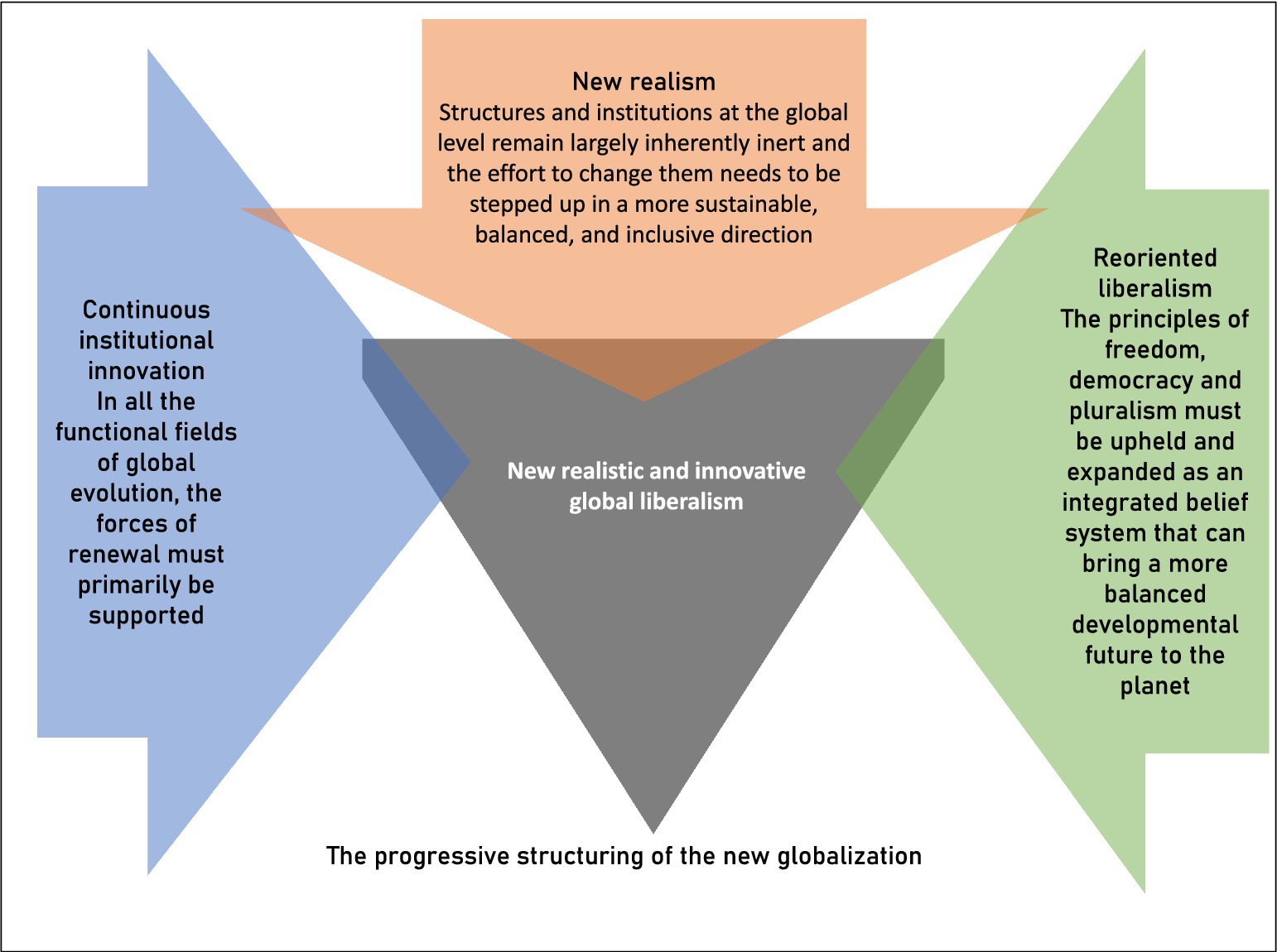

In envisioning the contours of new globalization, social resilience and environmental sustainability are pressing concerns (Bartelmus, 2013). The optimal poverty alleviation strategy should transition from ephemeral growth to long-term structural socioeconomic transformation. To combat inequality, external assistance might be less effective than bolstering developmental opportunities universally. Curtailing extreme financial speculation will necessitate a reimagined global financial regulatory framework. Additionally, augmenting freedom and political rights necessitates refocused state intervention, one that amplifies each socioeconomic system’s developmental and innovative potential. Promoting tolerance and pluralism becomes paramount for preserving global cultural diversity. These priorities, we believe, coalesce into what could be termed a new, realistic, and innovative global liberalism (Figure 3).

5 Conclusion

In our exploration of the evolving phenomenon of new globalization, we investigated potential trajectories and the framework within which this new reality could be comprehended and channeled toward a new global innovative liberalism. Our primary findings are:

• We identified three distinct trajectories shaping the landscape of new globalization. The first trajectory, “New Nation-Centric Fragmentation,” signals a movement toward populist governance, coupled with a lag in energy transition and a decline in innovation. The second, “New Multipolarity,” captures a restrained effort to transcend nation-centrism, leading to a moderate integration for sustainable development and middling innovation outcomes. The final trajectory, “New Realistic and Innovative Global Liberalism,” stands out by advocating for geopolitical realism. It emphasizes the creation of new international organizations, repositioning of Western interests, consolidation of European integration, dedication to sustainable growth that addresses climate change, and a thriving innovative spirit nurtured by open global networks. All three scenarios share one element: a new kind of regional cooperation and the emergence of a new global polarization geometry.

• Our vision for a “new globalization” necessitates a perspective we term “realistic and innovative liberalism.” Realistically, it respects the resilience of global structures, acknowledging the enduring relevance of national entities. Innovatively, it anticipates continual forces of renewal in functional global development networks, emphasizing their increased efficiency in addressing global challenges. The essence of “liberalism” underscores freedom, democracy, and pluralism as guiding principles, anticipating a balanced phase of globalization to address potential destabilizations across various domains.

To elucidate our findings further, these two central insights that emerged from our study can be distilled as follows. First, the future of globalization can take multiple paths, with the most promising trajectory anchored in “realistic and innovative liberalism” that balances respect for existing global structures with the continual forces of renewal. Second, adopting this perspective, centered on freedom, democracy, and pluralism, can pave the way for a balanced and sustainable phase of globalization.

This study, like all others, has its limitations. We offered a cursory overview of the new globalization, stressing the need for a renewed liberal approach. To make the evolutionary structural triptych more operational in interpretive terms, future work could translate each pillar into tractable analytical dimensions: geopolitical stability (such as polity effectiveness scores, conflict incidence), economic development (such as GDP-per-capita growth, trade-to-GDP, green-investment share), and innovation capacity (such as R&D intensity, high-tech exports). Synthesizing this multilevel approach into a composite, holistic, and evolutionary “triptych index” would allow longitudinal panel tests and cluster analysis to classify countries or regional blocs into the proposed scenarios and examine their developmental pay-offs. Applying the same protocol to mega-regional agreements such as the CPTPP, the RCEP, and the AfCFTA would provide concrete and more cohesive tests of the framework’s explanatory and predictive power.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ABC News. (2025). “Will Trump’s tariffs threaten the Fed’s soft landing? Experts weigh in.” Available online at: https://abcnews.go.com/Business/trumps-tariffs-threaten-feds-soft-landing-experts-weigh/story?id=119906069. (Accessed April 29, 2025).

Baldwin, R. (2016). The great convergence: Information technology and the new globalization. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press.

Bartelmus, P. (2013). The future we want: green growth or sustainable development? Environ. Devel. 7, 165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2013.04.001

Bonilla-Molina, L. (2020). Covid-19 on route of the fourth industrial revolution. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2, 562–568. doi: 10.1007/s42438-020-00179-4

Bricout, A., Slade, R., Staffell, I., and Halttunen, K. (2022). From the geopolitics of oil and gas to the geopolitics of the energy transition: is there a role for European supermajors? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 88:102634. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2022.102634

Burns, T., and Stalker, G. M. (2011). “Mechanistic and organic systems of management”, sociology of organizations: Structures and relationships. Washington, DC: Sage Publications, 14–18.

Carmody, P. (2019). “Globalization and regionalism in Africa”, oxford research encyclopedia of politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chatzinikolaou, D., and Vlados, C. (2023), “Unravelling the new globalization: an evolutionary structural analysis of postwar world capitalism and policy implications”, In Presented at the the 35th annual EAEPE conference on “power and empowerment in times of multiple crisis”, EAEPE, Leeds, UK.

Chatzinikolaou, D., and Vlados, C. (2024). New globalization and energy transition: insights from recent global developments. Societies 14:166. doi: 10.3390/soc14090166

Contractor, F. J. (2025). Assessing the economic impact of tariffs: adaptations by multinationals and traders to mitigate tariffs. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 35, 190–213. doi: 10.1108/RIBS-01-2025-0013

Cornell, A., Møller, J., and Skaaning, S.-E. (2020). Democratic stability in an age of crisis: reassessing the interwar period. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dmitracova, O. (2025), “Trump’s trade war will hit US prosperity hard, IMF warns. Available online at: https://www.cnn.com/2025/04/22/economy/imf-us-global-economies-tariffs-intl/index.html. (Accessed April 29, 2025).

Ghosh, J. (2022). The making of a catastrophe: the disastrous economic fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic in India. New Delhi: Aleph.

Hui, W. (2016). China’s twentieth century: revolution retreat and the road to equality. New York: Verso Books.

Kimura, F. (2021). RCEP from the middle powers’ perspective. China Econ. J. 14, 162–170. doi: 10.1080/17538963.2021.1933059

Laudicina, P. A., and Peterson, E. R. (2016). From globalization to Islandization. Chicago: ATKearney.

Leshoele, M. (2023). AfCFTA and regional integration in Africa: is African union government a dream deferred or denied? J. Contemp. Afr. Stud. 41, 393–407. doi: 10.1080/02589001.2020.1795091

Marinova, S. T. (2020). “Disrupting globalization: prospects for states and firms in international business” in COVID-19 and international business. eds. M. A. Marinov and S. T. Marinova (New York: Routledge), 365–377.

McAllister, I., and White, S. (2017). Economic change and public support for democracy in China and Russia. Eur.-Asia Stud. 69, 76–91. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2016.1267713

Nobis, A. (2017). The new silk road, old concepts of globalization, and new questions. Open Cult. Stud. 1, 203–213. doi: 10.1515/culture-2017-0019

Papic, M. (2021). Geopolitical alpha: An investment framework for predicting the future. Hoboken: John Wiley.

Qin, Y. (2016). “A relational theory of world politics”. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Wiley, The International Studies Association.

Rodrik, D. (2011). The globalization paradox: democracy and the future of the world economy. New York: W Norton & Company.

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 104, 333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Strohmer, M. F., Easton, S., Eisenhut, M., Epstein, E., Kromoser, R., Peterson, E. R., et al. (2020). “Introduction” in Disruptive procurement: winning in a digital world. eds. M. F. Strohmer, S. Easton, M. Eisenhut, E. Epstein, R. Kromoser, and E. R. Peterson, et al. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 1–17.

Torraco, R. J. (2016). Writing integrative literature reviews: using the past and present to explore the future. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 15, 404–428. doi: 10.1177/1534484316671606

Van Bergeijk, P. A. G. (2019). Deglobalization 2.0: trade and openness during the great depression and the great recession. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Vasconcelos, Á. (2008). “Multilateralising ‘multipolarity’” in Partnerships for effective multilateralism: EU Relations with Brazil, China, India and Russia. ed. A. Vasconcellos (Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies).

Vlados, C. (2019). The phases of the postwar evolution of capitalism: the transition from the current crisis into a new worldwide developmental trajectory. Perspect. Glob. Dev. Technol. 18, 457–488. doi: 10.1163/15691497-12341528

Vlados, C., and Chatzinikolaou, D. (2022). Mutations of the emerging new globalization in the post-COVID-19 era: beyond Rodrik’s trilemma. Territ. Politics Gov. 10, 855–875. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2021.1954081

Vlados, C., Katimertzopoulos, F., Chatzinikolaou, D., Deniozos, N., and Koutroukis, T. (2019). Crisis, innovation, and change management in less developed local business ecosystems: the case of eastern Macedonia and Thrace. Perpect. Innov. Econ. Bus. 19, 114–140.

Wang, Y. (2020). New regionalism reshaping the future of globalization. China Q. Int. Strateg. Stud. 6, 249–265. doi: 10.1142/S2377740020500116

Williamson, P. (2021). De-globalisation and decoupling: post-COVID-19 myths versus realities. Manag. Organ. Rev. 17, 29–34. doi: 10.1017/mor.2020.80

World Economic Forum (2018). Agile governance: Reimagining policy-making in the fourth industrial revolution. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Keywords: globalization crisis, new globalization, innovative liberalism, evolutionary structural triptych, sustainable global development

Citation: Vlados CM and Chatzinikolaou D (2025) The transformational crisis of globalization and the contingent trajectories towards innovative liberalism. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1528246. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1528246

Edited by:

Seulki Lee-Geiller, Yale University, United StatesReviewed by:

Hamid Mattiello, Fachhochschule des Mittelstands, GermanyYaffa Machnes, Bar-Ilan University, Israel

Copyright © 2025 Vlados and Chatzinikolaou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Charis Michael Vlados, Y3ZsYWRvc0BlY29uLmR1dGguZ3I=

Charis Michael Vlados

Charis Michael Vlados Dimos Chatzinikolaou

Dimos Chatzinikolaou