- Chair of Political Sociology, Institute of Political Science, University of Bamberg, Bamberg, Germany

Radical right parties are widely regarded as influential political actors, particularly in the domain of immigration policy. In recent times, greater attention has been directed towards the potential influence of these new parties on the output of the legislative process. As radical right parties are predominantly opposition parties, the radical right aims to exert indirect effects. The article extends research on the indirect policy effects of the radical right on immigration legislation. By utilizing the concepts of salience and distance in policy preferences, the article provides a more accurate depiction of the radical right’s potential for policy influence than previous accounts. The analysis encompasses 11 West European democracies from 1985 to 2017, a period that covers the consolidation of radical right parties. The results of linear regressions with country fixed effects illustrate that indirect effects by the radical right are not a pivotal element of immigration policy change. In the event of conservative office holders, radical right parties, however, have the capacity to exert an indirect effect on policy reforms through the interplay of salience and distance in policy preferences. An indirect effect is also evident in the highly symbolic sub-area securitization of immigration. The article provides evidence that new parties can influence the political future of a country through their indirect influence in shaping immigration policy. Whilst the influence on political competitors has been frequently discussed, the article demonstrates that the consequences of the radical right extend to public policy.

1 Introduction

“You do not need [political] power to have a lot of influence” (Akkerman, 2018, p. 12) proclaimed the leader of the Dutch Party for Freedom in 2014. This statement exemplifies public and academic debates indicating that radical right (parties)1 affect legislative processes. Governments have the mandate to policy-making, however it is widely perceived that RRP exert influence over public policies through their behavior within the national party competition. The focus of the discussion is predominantly on the RR’s core issue, namely immigration. Heretofore, research has examined the factors that determine the electoral performance of the RR, and the consequences of their electoral success on the policy stances of their political competitors. A more recent approach expands the view on the party competition between new2 parties and established parties. This approach emphasizes the role of the strategic behavior of the established mainstream parties in immigration policy (Heinze, 2017; Downes et al., 2021; Williams and Hunger, 2022). The present study utilizes these findings as a foundation for an examination of the effects of the RR on national immigration legislation.

In light of the involvement of the RR as a junior coalition partner, scholars have placed emphasis on the direct effects by incumbents. Despite the RR’s growing electoral support, RRP are rarely involved in government formation. Consequently, the article analyzes the prevailing case that the RR as opposition parties seek to exert indirect influence. It is evident that the RR has had a significant impact on the political agenda and the discourse on immigration. The concept of contagion effects delineates that mainstream parties have adopted more restrictive positions on immigration-related issues and multiculturalism in response to electorally successful RRP. With the exception of notable case studies and comparative approaches (Schain, 2006; Williams, 2006; Carvalho, 2014), the knowledge about the RR’s effect on the legislative output through party competition remains scarce (Biard et al., 2019). It is acknowledged that immigration can be regarded as a yardstick for the policy effect of RRP. The article therefore addresses the following question: How influential are radical right parties in affecting changes of national immigration policy in West European democracies? The article draws attention to the indirect influence that RRP exert on immigration laws.

The present study is grounded in two theoretical concepts, issue ownership and issue entrepreneurship, which emphasize the role of RRP as strategic drivers of immigration issues. With regard to the indirect effects on immigration laws, the paper employs Sulkin’s (2005) theory on issue uptake. Sulkin expounds that incumbents utilize legislative activities to address prominent campaign issues. An uptake strategy enables incumbents to forestall criticism and to address policy issues at an early stage. Building on her reasoning, the paper argues that the interplay of salience and distance in policy preferences is decisive for legislative change. Salience refers to the importance that parties attach to an issue. Distance in policy preferences is defined as the discrepancy in positioning between RRP and their political competitors, the center-right and the center-left. The combination of these two concepts provides a more comprehensive understanding of the indirect effect of the RR on immigration legislation.

The article makes three contributions to the existing literature. Firstly, the utilization of the interplay of salience and distance in policy preferences as a factor for changes of immigration policy constitutes an original contribution. This approach provides a more accurate representation of the indirect effects of RRP than previous accounts. Secondly, the article considers RRP in a more differentiated way. Previous approaches regard the RR as a homogeneous party group. By contrast, the article acknowledges the variation within RRP and offers a more accurate reflection of the complex immigration stances of these parties.3 Thirdly, the article considers the multidimensionality of immigration. The present study goes beyond general immigration policy4 by examining the sub-area of securitization of immigration. The policy area of securitization pertains to issues of national border security and the enforcement of entry criteria. Securitization is of great symbolic significance for the public debate on immigration policy.

The data on immigration policy derives from the recently updated Immigration Policies in Comparison dataset (Helbling et al., 2024). The data on political parties draws from both the Immigration in Party Manifestos dataset (Dancygier and Margalit, 2020) as well as the Party Government in Europe Database (Hellström et al., 2023). These comprehensive data sources enable the investigation of 11 West European democracies5 from 1985 to 2017. As RRP are established political actors in Western Europe, central research findings are derived from this region. The data spans a period of more than three decades and provides a comprehensive overview of the consolidation of RRP within the national party system, as well as the emergence of the politicization of immigration.

Regression models demonstrate that indirect effects based on salience and distance in policy preferences are not a pivotal element of legislative reforms. With regard to immigration policy, there is no discernible influence of indirect effects. In the event of conservative office holders, RRP, however, have the capacity to exert an indirect effect on policy changes. Investigating securitization of immigration, indirect effects on reforms are evident, and these effects are not contingent upon conservative office holders. The findings on securitization confirm the exceptional status of this policy area. In conclusion, the article contributes to our understanding of the policy influence of new parties. The findings illustrate that new parties have the capacity to influence the political future by exerting indirect effects on public policy. However, the results also indicate a limited degree of influence. Indirect effects by the radical right are contingent upon the strategic behavior of mainstream parties, particularly the center-right.

2 Direct and indirect effects of parties on immigration policy

Scholarship pertaining to the political consequences of parties has distinguished between direct and indirect effects. The majority of research concentrates on the direct effects of office holders. In the case of RRP and most new parties, the status of incumbency relates to that of a junior coalition partner. Scholars also designate the support of minority governments as a variant of direct effects. The status of being a support party for a minority government represents an intermediary role between incumbency and opposition. The argument is that the dynamics are similar to those of governments (Taggart and Szczerbiak, 2013). Significant changes resulting from the government participation of the RR have for instance been observed in Austria (e.g., new Asylum Law in 2003) and Denmark (e.g., changes of the Nationality Law during 2001 and 2005) (Akkerman and de Lange, 2012). Overall, the evidence for direct policy effects by the RR is mixed. Qualitative case studies note difficulties for RRP in realizing their policy objectives. Furthermore, it is indicated that the influence of the RRP is dependent on the national context. In summary, Akkerman (2012) refutes that the RR’s incumbency constitutes a decisive factor for legislative changes. By contrast, a quantitative study acknowledges that RRP as office holders implement more restrictive policies (Lutz, 2019a).

In the absence of the authority to exert legislative power, opposition parties aim to exert indirect effects by inducing governments to adopt policy proposals advanced by the opposition. Parliamentary democracies are systems in which the opposition is able to influence the policy-making process. Consequently, access to institutionalized power relations, such as the entry into the national parliament, is associated with political impact (Verbeek and Zaslove, 2015). To provide an illustration, the French RR exerted a considerable indirect effect on the formulation of the 2003 Immigration Law (Carvalho, 2016).

Van Spanje’s (2010) work on contagion effects sparked research on the RR’s indirect impact on the policy stances of political competitors. The term contagion denotes the phenomenon of mainstream parties (MP) advocating a more restrictive line on immigration in the aftermath of the electoral success of RRP. Meguid (2005) has designated this adaptation of policy positions as an accommodative strategy. Scholars acknowledge that MP are responsive to popular RRP, particularly in the context of immigration-related issues (Davis, 2012; Han, 2022; Minkenberg and Végh, 2023) and multiculturalism (Han, 2015a; Schumacher and van Kersbergen, 2016). However, Mudde (2013) cautions against overestimating the RR’s influence. Research findings indicate that contagion effects are confined to center-right MP (Abou-Chadi, 2016a; Han, 2015a).6 A quasi-experiment reveals an independent effect of RR’s parliamentary entry on the multiculturalist stance of conservative MP (Abou-Chadi and Krause, 2020). Recent studies have examined the consequences of accommodative strategies employed by center-right MP on the electoral outcome (Downes et al., 2021; Hutter and Kriesi, 2022). Overall, contagion effects are particularly evident in the context of immigration policy.

Indirect effects of RRP on public policies are sparsely researched. Biard (2020, p. 235) argues that the respective research “is still in its infancy.” Williams (2015, p. 1330) compares the knowledge on the RR’s political impact to the limited understanding of “black holes in space.” Case studies are employed as a prevalent analysis method. Carvalho’s (2014) work demonstrates that, in addition to the electoral threat induced by RRP, the agency of MP is also essential to comprehend the influence on public policies. The prevailing method of qualitative studies is being called into question, however. In consideration of the identified shortcomings, the narrow thematic focus (Mudde, 2017) and the absence of a cross-national perspective (Biard, 2020; Green-Pedersen and Otjes, 2019), it is recommended that subsequent research be conducted.

The majority of quantitative studies focus on the electoral threat generated by the RRP’s strong election results. These studies consider electoral threat to be the main factor of indirect influence. The respective analyses encompass the principal parliamentary representation or the RR’s vote share. Abou-Chadi (2016b) reports that the former reduces the probability of liberal immigration reforms. In consideration of the RR’s vote share, Han (2015b) ascertains that the restrictive influence on policies is contingent upon the investigated policy sub-area. These findings are controversial. A body of research comprising both qualitative and quantitative studies has demonstrated that electoral success by RRP does not necessarily result in the passing of more restrictive immigration policies (Carvalho, 2014; Lutz, 2019b).

Overall, research has started to adopt a cross-national perspective. Nevertheless, further improvements in the conceptualization of RR’s indirect effects are essential. The prevailing focus on election results has hitherto failed to accurately delineate the influence of RRP. The article contributes to the advancement of research by employing a more accurate understanding of the effect that the RR has on legislation. The emphasis on election results is predicated on the assumption of homogenous RRP, which is a potentially problematic assumption. Consequently, the RR’s multifaceted policy orientations have been disregarded. It is evident that RRP do not advocate for restrictive reforms across all policy sub-areas of immigration. An initial attempt by Lutz (2019b) to consider the ideological variation of the RR is creditable. However, his approach is constrained in terms of both time and geographical scope. The objective of the present paper is to provide a more fine-grained analysis of the RR’s indirect influence on immigration policies.

3 Policy effects of the radical right on immigration policy

The defining issue of the RR is immigration policy, which is why these parties are also referred to as anti-immigration parties. Consequently, RRP hold issue ownership on immigration (Burscher et al., 2015; Van der Brug and Berkhout, 2024). The concept of issue ownership assumes that voters ascribe to political parties a stable reputation for competence in a particular issue area (Petrocik, 1996). The electorate’s perception that RRP own the issue of immigration is a key factor in the electoral strategy of the RR, as these parties accentuate this topic in order to gain electoral advantage. Hobolt and De Vries (2015) add the concept of issue entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship is defined as the mobilization of previously disregarded issues by adopting a stance that substantially diverges from the prevailing political consensus. Consequently, RRP seek to reap electoral benefits by adopting a firmly restrictive position on immigration. It is evident that both theoretical concepts denote RRP as strategic issue drivers. However, the two concepts diverge in the RR’s strategy for achieving this objective. Issue ownership underscores the issue salience, while issue entrepreneurship highlights the distance in policy preferences as pivotal influence factors of RRP. The analysis of the RR’s indirect policy effects through these two factors is embedded in the theoretical framework of issue uptake.

Issue uptake conceptualized by Sulkin (2005) focuses on incumbents that use legislative activities to address prominent campaign topics of their political competitors.7 Scholarship highlights the effect of campaigns on immigration policy (e.g., Hadj-Abdou et al., 2022). During electoral campaigns, opposition parties endeavor to emphasize the thematic shortcomings of office holders. Consequently, election campaigns serve incumbents as an efficient information signal. In the course of the ensuing term in office, governments have the possibility to take up campaign issues selectively. Hence, strategic reasoning by office holders indicates an increased legislative focus on prominent campaign topics.

It is an essential prerequisite for the implementation of an uptake strategy by incumbents that they first recognize an issue and subsequently assign importance to it. Given that office holders are unable to allocate their limited legislative attention equally to all policy areas, office holders need to identify promising topics. The implementation of an uptake strategy signals responsiveness to public demands. Furthermore, uptake is electorally motivated, as it provides incumbents with an opportunity to promote their re-election. It is therefore argued that governments use this strategy as a means of safeguarding themselves against both current and future criticism (Christiansen and Seeberg, 2016). Once office holders allocate legislative activities to a particular issue, competitors are effectively prevented from successfully politicizing the topic. Consequently, an uptake strategy provides incumbents with the opportunity to push an unfavorable topic aside the political agenda (Gordon and Huber, 2007).

The implementation of an uptake strategy has the potential to involve certain drawbacks. In addition to misplaced attention, an uptake strategy may result in discrepancies within the parties, potentially leading to the alienation of voters or the impediment of future coalition-building (Hadj-Abdou et al., 2022). Despite the fact that office holders pursue an uptake strategy to reduce their competitors’ electoral prospects, it is possible that the strategy may backfire and strengthen the opposition (Froio et al., 2017). Consequently, incumbents must exercise caution when selecting an uptake strategy.

The rationale underpinning influential RRP builds on the findings of prior research on issue ownership, with salience identified as a decisive factor. Office holders recognize salient topics as societal problems that they must address. The failure to acknowledge these significant issues carries risk. Consequently, prominent issues become almost impossible to avoid (Van der Brug and Berkhout, 2024). In light of the obstacles associated with legislative reforms, incumbents allocate substantial resources to issue areas that are of high prominence on the political agenda. In circumstances in which the salience of an issue is low, policymakers are unlikely to bear the risks associated with the implementation of an uptake strategy.

With regard to the concept of issue entrepreneurship, a distance in policy preferences between the RR and MP is a prerequisite for an uptake strategy. In the event of the proposed policy concepts converging, incumbents have no incentive to initiate a legislative change. The greater the deviation of the policy preference of the issue entrepreneur from the prevailing political consensus, the greater the pressure on incumbents to address the issue of the entrepreneur. In conclusion, it is evident that the RR has the capacity to exert an indirect effect on immigration policy by drawing on issue salience and deviant position-taking.

The present paper posits the argument that the interplay of salience and distance in policy preferences is pivotal for the introduction of restrictive policy reforms.8 The absence of distance in policy preferences on salient issues engenders minimal pressure on governments to take legislative action. In the event of a consensus issue becoming salient, incumbents are subject to little pressure to act. Similarly, in instances where a discernible distance in policy preferences is evident, the issue remains latent in the absence of salience (Van der Brug et al., 2015). Therefore, restrictive reforms require an interplay in which a marked discrepancy in policy preferences between MP and the RR attracts considerable attention.

In principle, incumbents act strategically and effectuate an accommodative strategy by taking up crucial issues of the party competition. The primary objective of office holders is to claim recognition for addressing the topic, while simultaneously seeking to deprive opposition parties of a popular subject. It is important to note that while all incumbents experience the pressure by the RR and need to react to issues that gain salience, it is imperative that the thematic distance between the actors is not excessively pronounced. Parties pay close attention to their credibility as perceived by voters and the general public. Consequently, a substantial discrepancy in policy preferences may appear unbridgeable via an uptake strategy. This consideration is likely to facilitate the bridging of smaller policy distances. This reasoning is of particular relevance to conservative, respectively, center-right parties (see Hypothesis 2). The first hypothesis depicts the RR’s indirect effect on immigration policies.

Hypothesis 1 (Indirect Effect of RRP): The more intense the interaction between salience and distance in policy preferences, the more restrictive the legislative changes of immigration policies.

Research indicates that the strategic approach of MP within the party competition are influenced by contagion effects, with conservative parties being particularly impacted (Abou-Chadi, 2016a; Han, 2015a). In the context of immigration policy, center-right parties find themselves situated between two conflicting ideals. The principles of economic liberalism advocate policy openness, whilst those of cultural conservatism advocate restrictions. The mounting electoral pressure on conservative parties is attributable to the fact that their voters are increasingly drawn to the appeal of RRP. This aforementioned logic is also applicable when considering government partisanship. Carvalho (2014) posits that the strategic dilemma is particularly applicable to center-right incumbents. Akkerman (2012) likewise indicates that the primary responsibility for implementing restrictive policy changes lies with conservative parties. Center-right governments are also inclined to implement a greater number of changes to policy sub-areas, with the example of high-skilled immigration (Kolbe, 2021). Hypothesis 1 is thus expanded to encompass a focus on conservative governments.

Hypothesis 2 (Indirect Effect of RRP on Conservative Governments): The more intense the interaction between salience and distance in policy preferences, the more restrictive the legislative changes of immigration policies implemented by conservative governments.

The RR’s electoral performance is frequently referenced by scholars as a predictor of restrictive policy reforms (Carvalho, 2014; Biard, 2020). In light of the aforementioned inaccuracy inherent in the concentration on election results, the analysis employs election results of RRP as a control variable.

Research on immigration reforms highlights the necessity to acknowledge the multidimensionality of immigration (Natter et al., 2020). The present paper focuses on the securitization of immigration as a distinctive policy sub-area. Securitization pertains to issues of national border security and immigration control, such as measures to combat illegal immigration. These aspects are crucial for the public perception of immigration policy, as immigration is commonly framed as a security issue. Securitization can thus be regarded as a highly symbolic sub-area for the implementation of restrictive immigration policies (Natter et al., 2020). The scholarship has indicated early on the exceptional character of these policy aspects (Freeman, 1994). This assertion is corroborated by the findings of recent studies (Helbling and Meierrieks, 2020; Lutz, 2024). In consideration of the distinctive characteristic of this policy sub-area, the analysis broadens the scope by testing both hypotheses within the context of the securitization of immigration.

4 Data and research design

The analysis encompasses eleven West European democracies from 1985 to 2017.9 A comparison of these eleven countries reveals numerous similarities. These countries are all industrialized nations that are characterized by comparable socio-economic dynamics and a reliance on immigration for the maintenance of their socio-economic stability (Lutz, 2019a). In addition, these eleven countries are established democracies that cooperate within the framework of the European Union. Furthermore, the primary research conclusions concerning the RR are founded on Western Europe, given the particular relevance of these party actors within the region. Consequently, all the analyzed countries exhibit a comparable economic and political context.

The investigation period starts in the mid-1980s, covering the RR’s entry and consolidation within the national party system. The timeframe is a consequence of the temporal overlap between the Immigration Policies in Comparison (IMPIC) and Immigration in Party Manifestos (IPM) dataset.10 The aforementioned period corresponds to the start of the politicization of immigration (Hutter and Kriesi, 2022). Immigration policy is an ideal domain for testing the central arguments of this paper, as the policy effects of RRP should be most clearly evident within this policy domain. Relying on annual data as unit of analysis, 236 country-year dyads are covered. Based on the 236 observations, Supplementary Table A.2 provides a descriptive overview of all variables employed.

Yearly changes of national immigration policies depict the dependent variable. The recently updated IMPIC dataset (Helbling et al., 2024) covers immigration policy in the member states of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2024) (OECD) from 1980 to 2018. IMPIC quantifies the extent to which laws liberalize or limit the rights and freedoms of immigrants (Berger et al., 2024). Scores are rescaled from 0 (open) to 100 (restrictive) so that higher values denote restrictive policy changes. The dataset facilitates the investigation of general immigration policy and the sub-area securitization of immigration.11 The policy area of securitization pertains to issues of national border security and immigration control. Such matters include international information sharing and measures against illegal immigration. Securitization has been assigned a high symbolic significance in the public debate on immigration policy, due to the presence of political controversies and the level of public attention it has attracted.

Salience and distance in policy preferences are the primary predictor variables. The two variables are derived from the IPM dataset (Dancygier and Margalit, 2020), which is based on party manifestos. Covering national elections in 12 West European democracies from 1960 onwards, the coding scheme for immigration policy consists of 30 categories. Coders assessed the salience and the position on immigration of the major center-left, major center-right and, if applicable, RRP.12 Establishing consistency with IMPIC’s coding, the author adapted the IPM categories to securitization of immigration.

Due to the profound coverage, the IPM dataset outperforms other established data sources. The Comparative Manifestos Project (CMP) recently introduced a direct measurement of immigration. To analyze longer periods, CMP categories, like multiculturalism or national way of life, are commonly used as proxies. This approach is criticized for an unclear scope (Green-Pedersen and Otjes, 2019). Dancygier and Margalit (2020) demonstrate that these proxies only vaguely reference to immigration. The Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) started 2001. Apart from the shorter period, CHES does not cover immigration stances extensively. In summary, it is preferable to use the comprehensive and detailed IPM dataset.

Salience is operationalized as percentage of words relating to immigration. Regarding securitization of immigration, salience depicts the share among all references to immigration policy. Higher values indicate a greater importance attached to the issue. Salience captures the average priority within the electoral competition. Salience is a weighted score, with each party being weighted based on the party size.13 The variable on distance in policy preferences reflects the ratio of liberal and restrictive positions on immigration. It is conceptualized as the distance between RRP and the political competitors. The variable is presented in two different versions: the distance between the RR and the center-right, and the distance between the RR and the center-left. Ranging between ±2, values greater than zero highlight a more restrictive policy preference by the RR compared to the respective political competitor. The indirect effect of RRP is additionally captured by the interaction term of salience and distance in policy preferences.14, 15 In accordance with Hypothesis 2, a dummy variable pertaining to conservative, respectively, center-right governments is of particular relevance.

In order to take into account the consequences of the electoral threat induced by the electoral performance of RRP, the RR’s vote share in lower house elections and their government participation is included. The inter-party competition dynamic is captured by comparing the electoral results with those of the preceding ballot. Alternatively, the change in the number of parliamentary seats held by the RR is calculated. A positive value is indicative of electoral gains by RRP. Following prevalent classifications, a dummy variable records the government participation by RRP.16 These variables are derived from the Party Government in Europe Database (PAGED) by Hellström et al. (2023).

Full models utilize additional control variables that are plausible drivers of policy changes: The analysis uses annual data by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2024) to account for the factual pressure on governments to address immigration. The proportion of immigrant population17 and the annual percentage change of the unemployment rate are used. Annual changes of the real gross domestic product (GDP growth) serve as a robustness check of the economic context. A dummy variable encompasses whether or not a country is a member state of the European Union (EU) in a specific year.18 The variable is intended to capture the impact that EU institutions have on national-level immigration policy. The incorporation of the variable occurs in the context of the discourse surrounding the limited competence of the EU in this policy area and the existence of liberal constraints imposed by the EU on its member states (Bonjour et al., 2017; Geddes et al., 2020).

On grounds of the cross-sectional and cross-temporal data structure, the analysis employs linear regressions with country and decade fixed effects19 and robust standard errors clustered by countries. Models make allowance for sources of heterogeneity and autocorrelation. The model specification precludes national characteristics that remain constant during the investigation period, whilst also controlling for unmeasured country-specific factors. All models include the corresponding national policy level to account for ceiling effects. Previous legislative changes potentially influence subsequent reforms. However, the reasoning is less plausible for years with government turnover. The incorporation of a one-year lagged dependent variable thus serves as an additional robustness check.

5 Descriptive statistics

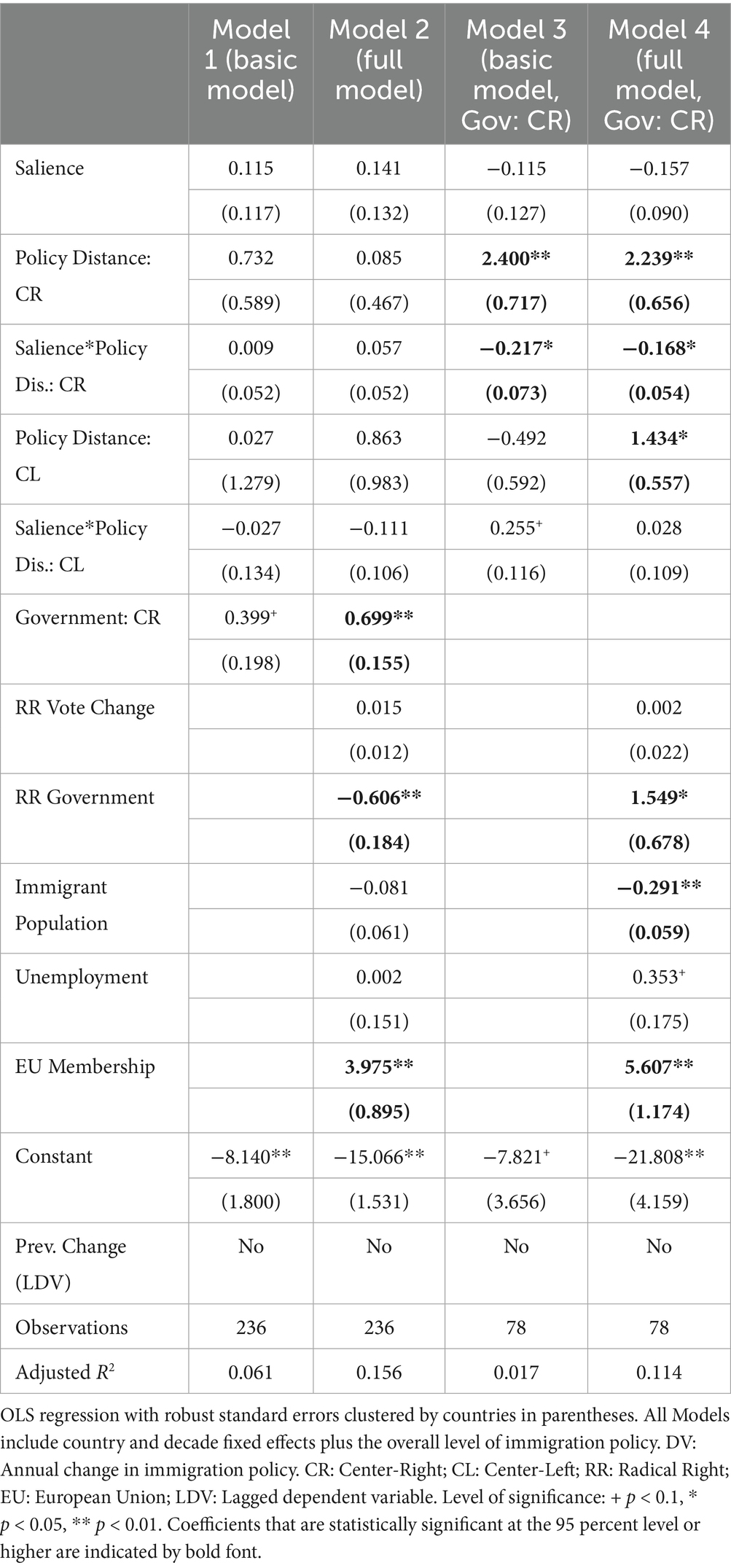

Figure 1 illustrates that immigration reforms are regularly adopted. Governments seeking to implement policy alterations encounter challenges in their attempts to pass reforms, with potential obstacles including the coordination with coalition partners or the approval of a second chamber. In addition, external constraints in the form of agreements or treaties at either the European or the international level limit the leeway of incumbents to change policies to a considerable degree.

Figure 1. Annual change in immigration policy. The potential range of policy scores is from 0 (entirely liberal) to 100 (entirely restrictive). Positive values denote restrictive policy changes; negative values indicate liberal policy changes.

Despite the prevailing assumption that legislative reforms are infrequent and policies remain largely stable, Figure 1 demonstrates that annual changes in immigration policy are frequently implemented. Positive values of the dependent variable indicate restrictive reforms, whilst negative values denote policy liberalizations. There is a slight tendency towards liberalizations for the period under investigation (mean value = −0.02). In summary, changes in immigration policy occur in two-thirds of all cases.

As reforms in different policy sub-areas could lead to the impression of overall stability, Supplementary Figure A.1 compares annual change in immigration policy and securitization. As demonstrated in Supplementary Figure A.1, the examination of immigration policy changes can obscure securitization reforms. Annual changes in immigration policy and securitization are only marginally positively correlated (r = 0.21, p-value: 0.001).20 Incumbents adopt substantial securitization reforms regularly, mainly in a more restrictive direction (mean value = 0.44). The sub-area of securitization has a reform rate of 30%. The descriptive insights regarding the dependent variables highlight the importance of analyzing the securitization separately from immigration policy.

Turning to the predictor variables, Supplementary Figure A.2 depicts the salience of immigration for each country. Only Finland, Italy21 and Norway consistently show a salience level below 5% for the period under investigation. A t-test validates that RRP attach on average significantly more attention to immigration policy than MP (13.06% of the manifesto compared to 3.64% by the center-right and 3.46% by the center-left).22 Immigration, however, is not being ignored by MP. By contrast, MP in eight countries dedicate more than 5% to the issue in at least one election. In view of the fact that MP address a wide range of policy issues, this is a substantial share.23

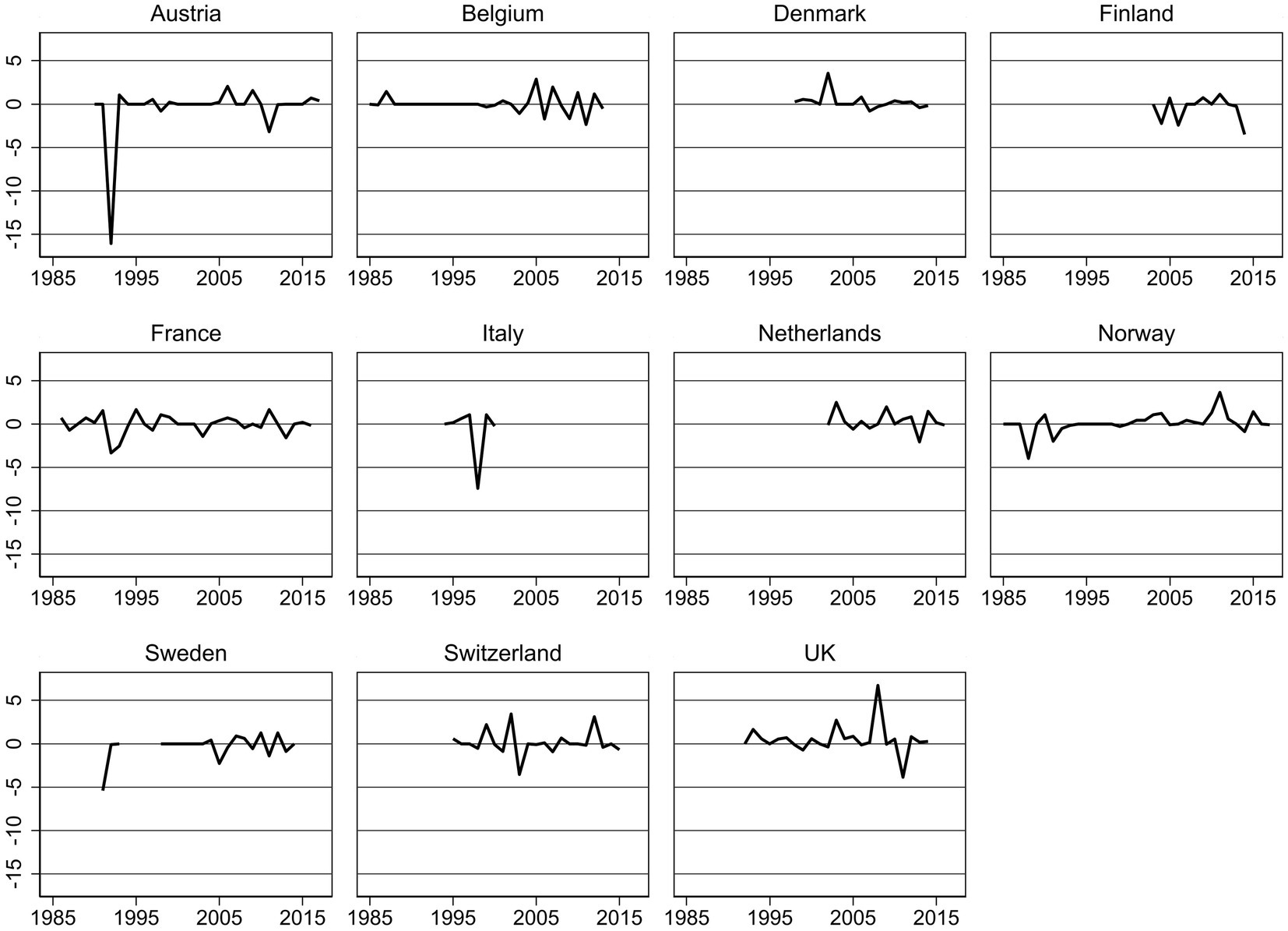

Figure 2 illustrates a substantial degree of distance in policy preferences. Showing the distance in preferences by party type, Figure 2 indicates that the parties of the political mainstream accommodate their stance considerably over time. A t-test corroborates that RRP are significantly more restrictive on immigration than MP. RRP characteristically adopt a position that is substantially restrictive (−0.73). By contrast, the center-right adopts a neutral stance, while the center-left takes a liberal position.24 Overall, the distance in policy preferences between the center-right, respectively, the center-left and the RR is considerable.25, 26 Both variables on distance in policy preferences are moderately positively correlated (r = 0.28, p-value: 0.000).

Figure 2. Distance in policy preferences on immigration by party type. The Figure depicts the distance in policy preferences between the center-right (CR) and the radical right (RR) as well as the center-left (CL) and the radical right (RR) for the period under investigation. Policy preference of a party is measured between a liberal (1) and a restrictive pole (−1). Policy preference distance potentially ranges from +2 to −2.

The two concepts, salience and distance in policy preferences, are moderately correlated in terms of the center-right (r = −0.26, p-value: 0.000), but not significantly linked with regard to the center-left (r = −0.06, p-value: 0.388). This finding suggests that high salience is not necessarily indicative of a large discrepancy in policy preferences. Therefore, the results of the descriptive statistics presented lend support to the reasoning that salience and distance in policy preferences are two independent concepts of indirect influence of the RR.

6 Results

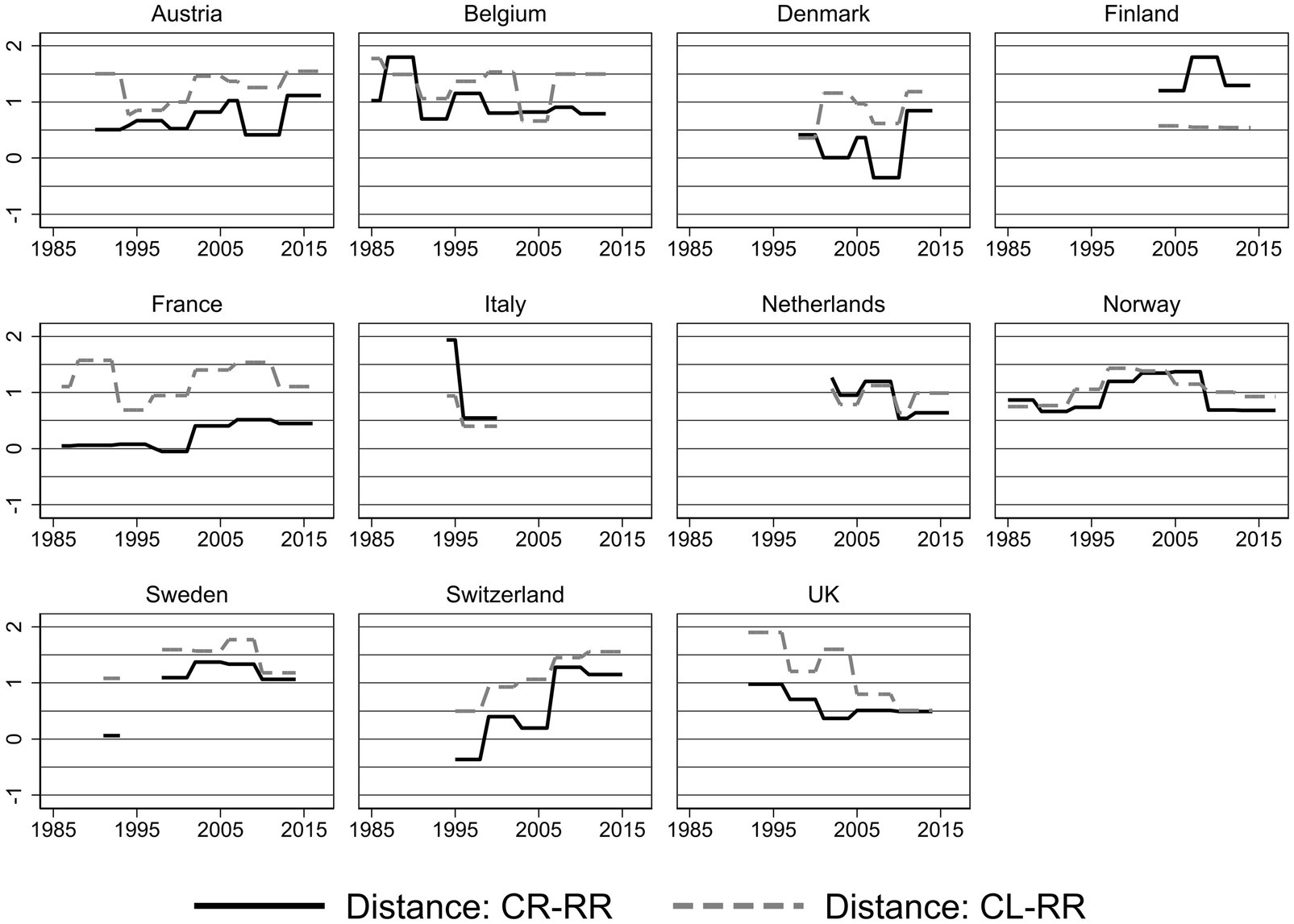

Table 1 provides a test of the hypotheses on the indirect effect of radical right parties by considering the interaction between salience and distance in policy preferences. Initial consideration is given to all cases, with a subsequent focus on conservative governments. Annual changes in immigration policy is the dependent variable. Model 1, the basic model, includes the predictor variables without control variables. Model 2, the full model, adds the control variables. Model 1 and Model 2 demonstrate that salience, distance in policy preferences and the interaction term are unrelated to annual policy changes. This finding is applicable to both the distance in preferences between the RR and the center-right, as well as the distance in preferences between the RR and the center-left. Hence, Hypothesis 1 is rejected for immigration policy.

Turning the focus to conservative governments as outlined in Hypothesis 2, Model 4 provides a test of the hypothesis. The interaction term of salience and distance in policy preferences between RRP and center-right MP has a significantly negative effect on policy change (p-value: 0.013). Figure 3 dives deeper into this result and illustrates the effect plot for the interaction term based on the full model. The effect plot depicts predicted policy changes for five levels of distance in policy preferences at the x-axis (mean distance plus/minus one/two standard deviation (SD)) and two levels of salience indicated by the shape of the marker (triangle for mean salience, circle for mean salience minus one SD).

Figure 3. Effect plot for the indirect effect of radical right parties on immigration policy of conservative governments. The Figure is based on Model 4 in Table 1. Distance in policy preferences denotes the distance between the center-right and the radical right. Positive values of policy change on the y-axis denote restrictive changes; negative values indicate liberal policy changes. 95% confidence intervals are displayed.

Figure 3 supports Hypothesis 2 implying an indirect effect of the RR on policy changes implemented by conservative governments. However, the effect of the interaction term does not entirely align with the expectation. In circumstances where the distance in preferences is high but salience is low, substantial restrictive policy changes are enacted (mean distance plus one SD: 2.27, p-value: 0.01, CI: 0.72 to 3.82/mean distance plus two SD: 3.45, p-value: 0.01, CI: 1.37 to 5.54). This context is congruent with the scenario delineated as latent conflict. The restrictive effects for a high distance in preferences is confirmed in the case of mean salience. Conversely, policy liberalizations do not come into force in the scenario of low distance and low salience, as the 95% confidence interval overlaps the zero line. In instances of low distance and mean salience, conservative government implement liberal reforms (mean distance minus two SD: −1.56, p-value: 0.03, CI: −2.95 to −0.17/mean distance minus one SD: −0.78, p-value: 0.04, CI: −1.54 to −0.03). A scenario of high salience yields no policy changes, irrespective of the level of distance (results not illustrated in Figure 3).

As immigration reforms are principally marginal (mean value: −0.02, median: 0), Figure 3 displays substantial policy reforms in accordance with the configuration of the interaction of salience and distance in preferences. Overall, restrictive policy reforms by conservative incumbents are encouraged in instances where a major distance in preferences and a minor, respectively, mean salience are concomitant. Figure 3 provides partial confirmation of Hypothesis 2, as the implementation of immigration reforms by center-right incumbents is associated with the indirect effects by the RR.

An examination of the individual factors salience and distance in preferences reveals an absence of effects on immigration policy. Salience does not attain statistical significance in the models presented. Focusing on conservative office holders, a significant restrictive effect on immigration reforms is observed for increasing distance in preferences. The importance of distance in preferences in the context of indirect effects by RRP is evidenced in Figure 3, as a high distance in policy preferences appears to be a prerequisite for the implementation of restrictive reforms.

Investigating the influence of electoral threat induced by RRP, the evidence speaks against an effect through mere parliamentary presence of RRP. The RR’s vote share is unrelated to policy reforms.27 Counterintuitively, government participation of RRP is associated with more liberal immigration policy changes (Model 2). The effect of government participation of RRP becomes restrictive when the focus is directed towards center-right office holders (Model 4). Regarding other control variables, a growing proportion of immigrant population is associated with liberal reforms by conservative incumbents. Moreover, EU membership has a restrictive effect in Model 2 and Model 4.

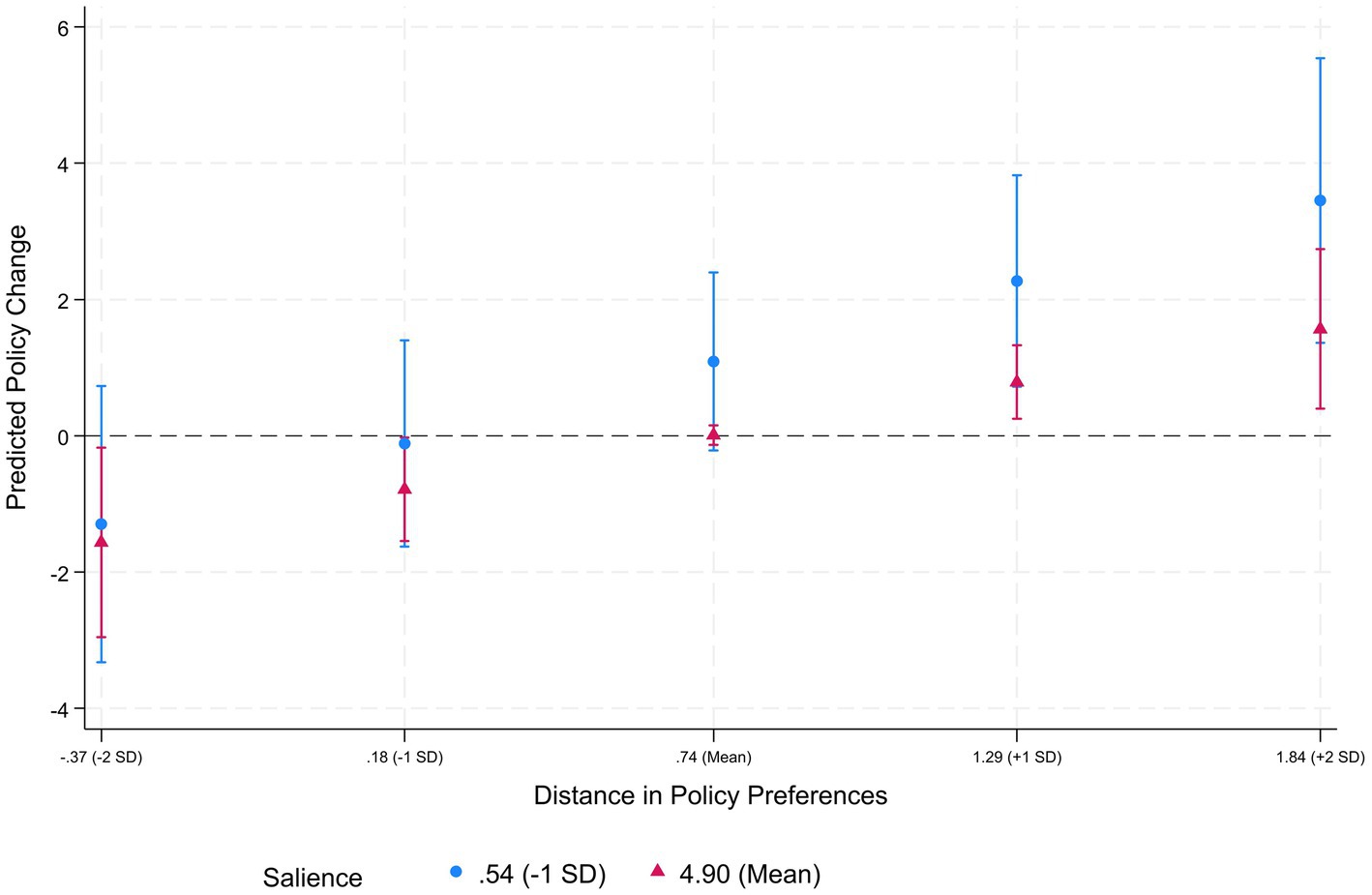

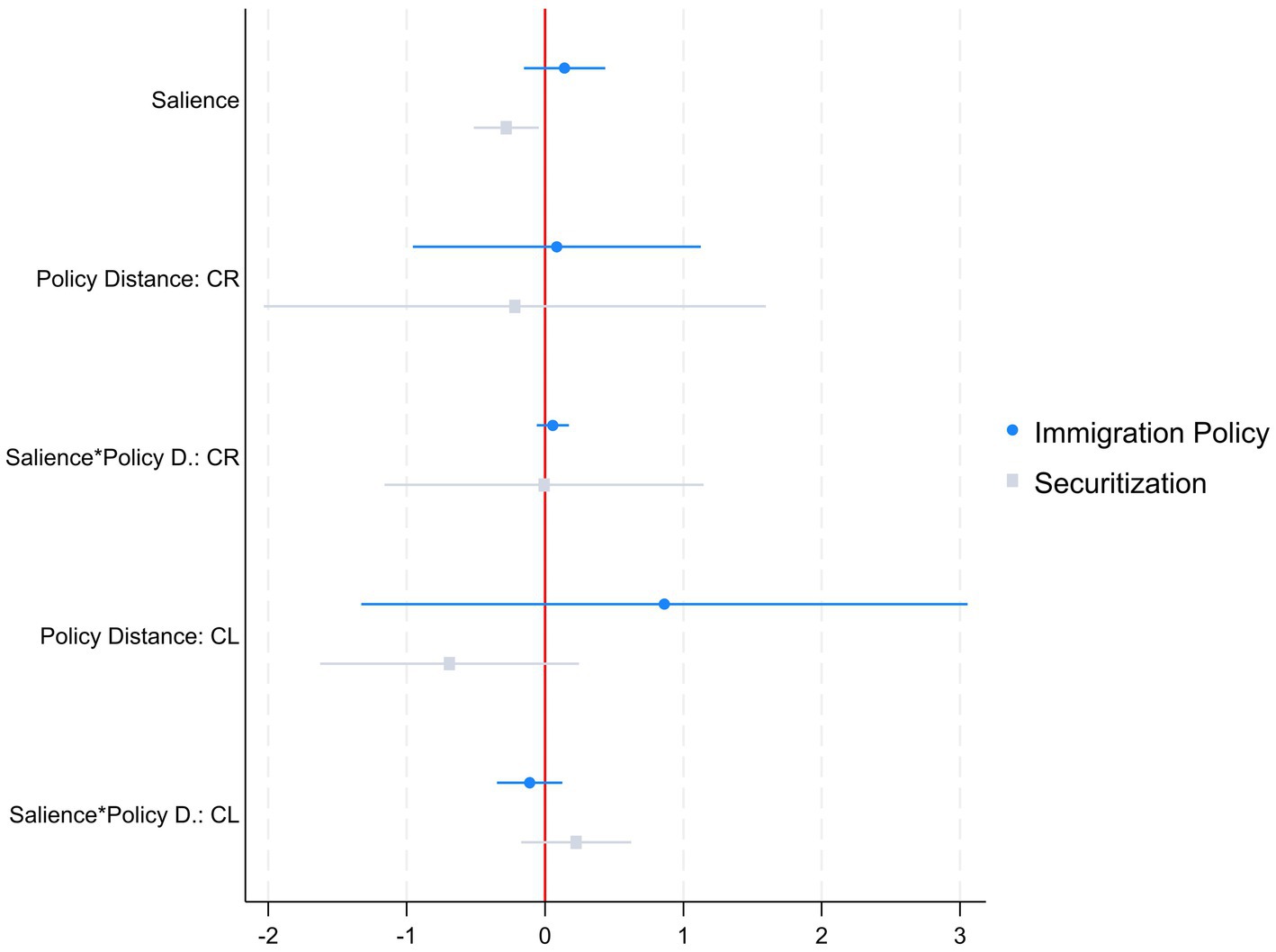

In a next step, the analysis zooms in by focusing on the securitization of immigration policy. Consequently, annual change in securitization is the dependent variable. Supplementary Table A.3 presents the results in the form of a regression table. The coefficient plot in Figure 4 graphically compares the results of the full models for immigration policy and securitization (Model 2 and Model 2S). In line with the expected distinctiveness of securitization, Figure 4 illustrates differences in the direction and the magnitude of the effects.

Figure 4. Coefficient plot for immigration policy and securitization. The Figure is based on Model 2 in Table 1 for immigration policy respectively Model 2S in Supplementary Table A.3 for securitization. Positive coefficients denote a restrictive effect on annual policy changes. 95% confidence intervals are displayed.

As demonstrated by Figure 4, the results on immigration policy cannot be transferred to the sub-area of securitization. Contrary to the results for immigration policy, salience shows a liberal and significant effect on securitization change in Model 2S. In principle, the direction of the effects has shifted towards liberal effects. The liberal effect of policy distance and the interaction term for center-right MP remain insignificant.

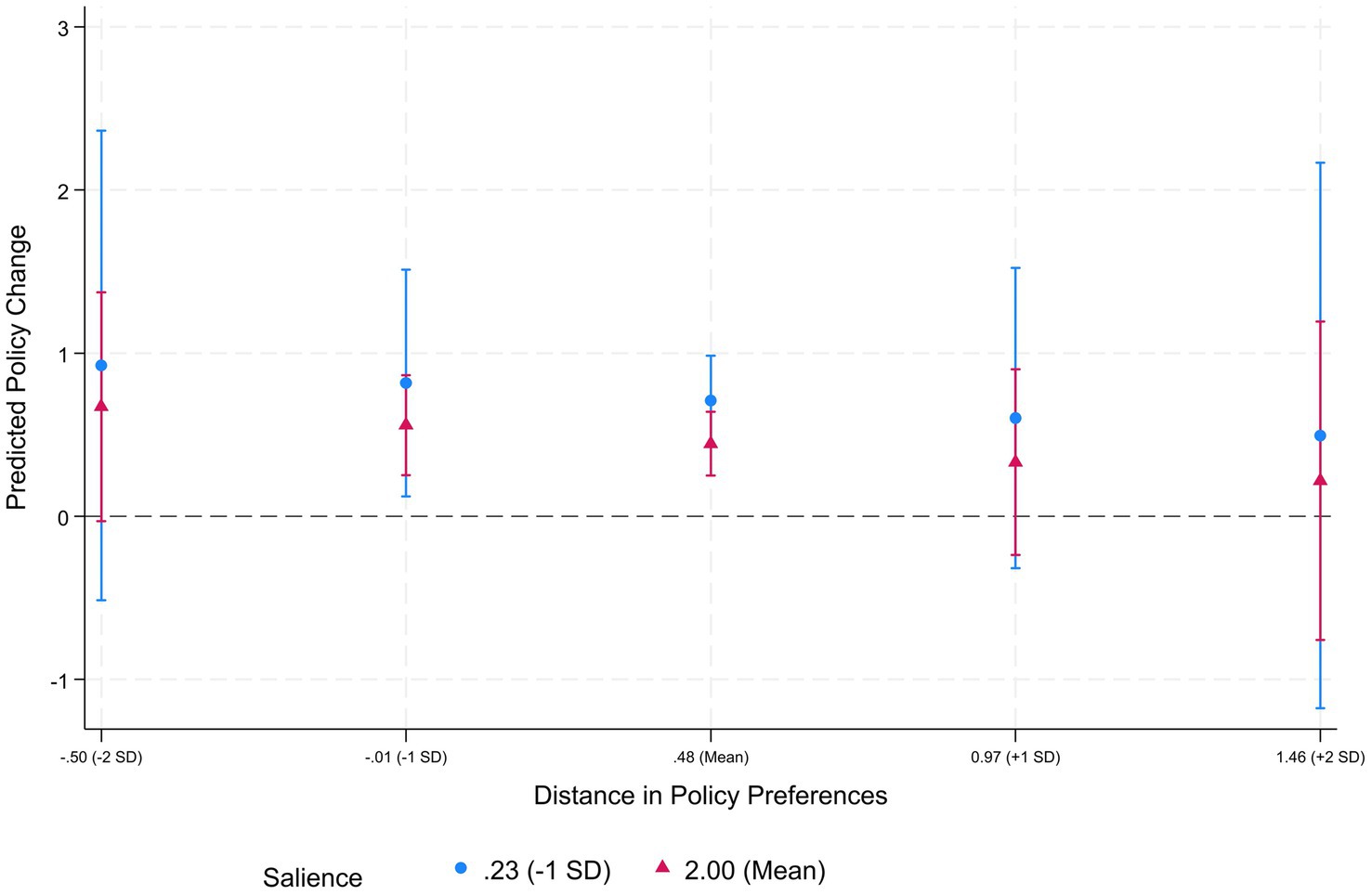

Figure 5 depicts the effect for the interaction of salience and policy distance in more detail. The effect plot based on Model 2S reveals that the indirect influence of RRP on securitization does not align with the results on immigration policy. The combination of minor or mean policy distance with minor salience is associated with restrictive securitization changes (mean distance minus one SD: 0.82, p-value: 0.03, CI: 0.12 to 1.51 / mean distance: 0.71, p-value: 0.00, CI: 0.44 to 0.98). This finding is also corroborated in the context of mean salience. It is noteworthy that this scenario has resulted in liberalizations, within the context of immigration policy and conservative governments. The direction of the effect of policy distance has undergone a shift. Whilst policy restrictions on immigration were seen to increase with distance, this trend is being reversed in the area of securitization. The scenario that results in immigration reforms by center-right governments (latent conflict implying minor, respectively, mean salience and major policy distance) does not change the status quo. In general, major salience of securitization puts the brakes on reforms (results not illustrated in Figure 5). In a scenario of major salience no policy changes are adopted irrespective of the extent of policy distance. The evidence lends support to a partial confirmation of Hypothesis 1 regarding securitization policy, as governments take the interaction of salience and policy distance into consideration when passing securitization reforms.

Figure 5. Effect plot for the indirect effect of radical right parties on securitization. The Figure is based on Model 2S in Supplementary Table A.3. Distance in policy preferences denotes the distance between the center-right and the radical right. Positive values of policy change on the y-axis denote restrictive changes; negative values indicate liberal policy changes. 95% confidence intervals are displayed.

Compared to immigration policy, center-right governments do not significantly influence reforms of securitization legislation. This can be observed in the negligible effect of conservative governments in Model 2C. Consistent with the approach for immigration policy, the analysis places a similar emphasis on conservative office holders. These models further demonstrates an absence of findings with respect to the predictor variables and the control variables (Model 3S and Model 4S, Supplementary Table A.3). The sole exception pertains to the restrictive effect of EU membership. In conclusion, Hypothesis 2 is refuted with regard to securitization.

Model 2S illustrates that an increasing vote share of RRP is associated with restrictive control reforms at a minor significance level (p-value: 0.07). Apart from this finding, no statistically significant effect of government participation of the RR, the factual pressure to address immigration issues, or EU membership materializes. Overall, the analysis of the policy sub-area supports the distinctiveness of securitization aspects and underlines the necessity to consider securitization policy separately.

7 Discussion

The analysis illustrates the potential indirect effect of RRP on legislative changes of immigration policy. In the context of immigration policy, the indirect influence is negligible. The interaction term and the components salience and distance in policy preferences are unrelated to policy reforms. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is rejected for immigration policy. The significant effects for conservative governments and for the RR’s participation in government demonstrate that policy reforms are primarily attributable to the executive branch and to government partisanship. A potential influence of RR through indirect effects does not emerge. Hence, the result is indicative of a limited policy influence exerted by RRP on immigration policy. The presented finding is therefore consistent with research that cautions against overestimating the impact of the RR (Mudde, 2013), especially with regard to immigration policy (Carvalho, 2014).

As stated by the theoretical argument in Hypothesis 2, conservative office holders are particularly likely to be influenced by RRP when passing reforms. Model 2, the full model, demonstrates that center-right incumbents adopt considerably more restrictive legislative changes. The graphical analysis with a focus on conservative governments illustrates that the RR has an indirect effect on legislative changes in this scenario. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 has been partially confirmed for immigration policy. Major distance in policy preferences is a prerequisite for restrictive reforms by conservative governments. The level of distance in positioning between the center-right and RR is primarily determined by the policy stance of RRP. Therefore, the RR can be relevant for legislative changes in a scenario of conservative office holders. However, center-right governments tend to avoid reforms in the scenario of high salience. Instead, reforms are adopted in instances when major distance is accompanied by minor or mean salience. This could speak in favor of an anticipation effect, as governments might take up the issue of immigration before it is salient within the electoral competition. Moreover, incumbents appear to avoid the impression of being driven to restrictive reforms by the RR’s strict policy proposals.

The results are corroborated by various model specifications. Firstly, alternative variables (RR’s share of parliamentary seats; annual changes of the GDP) are incorporated into the models. Secondly, adding previous policy change to the models also affirms the presented findings. Thirdly, the results remain robust, in the absence of weighting of salience based on the election results. If weighting is not applied, all parties are considered equally influential regarding salience. Therefore, salience is calculated based on the mean value of all parties. Fourthly, individual countries were excluded from the analysis. In conclusion, the results remain substantially robust to different model specifications.28

A divergent picture is evident for securitization policy, however. In this sub-area, which is highly symbolic, the interaction between salience and policy distance exerts a different influence on reforms. The implementation of restrictive changes occurs most likely in environments characterized by minor policy distance and minor salience. Overall, the investigation of securitization policy provides partial support for Hypothesis 1. The full model on securitization indicates that government partisanship is not associated with reforms of securitization policy. This finding is also evident in the investigation, which focuses on conservative incumbents. Therefore, it is evident that Hypothesis 2 is to be rejected for securitization policy. The absence of effects for government partisanship is in accordance with findings by Natter et al. (2020), who likewise conclude that government composition does not influence changes of securitization policy.

The results highlight the distinctiveness of securitization policy and raise the question how the differences between immigration policy and securitization policy can be explained. Intra- and inter-party considerations can provide an explanation. Center-right and center-left MP endorse exceptionally restrictive ideas on securitization. Center-right MP partly advocate more restrictive stances on securitization policy than the RR, for example in Austria (2008–2012) and Denmark (2005–2006). Therefore, these parties aspire to implement the restrictive approach when being part of the government. Overly restrictive policy stances imply that the ideological intra-party division of office holders is marginal. Less ideological controversies lead to clearer policy stances on immigration (Han, 2022) and make the adoption of restrictive policies more likely (Natter et al., 2020). Turning to inter-party motives, office holders aim to prevent an increase of the electoral potential of RRP. As measures against illegal immigration are the signature issue of RRP and receive considerable public attention, incumbents might refrain from legislative changes when immigration policy or the securitization of immigration becomes highly salient. Overall, intra- and inter-party motives can provide an explanation for the different findings on securitization policy.

In considering the potential impact of RRP beyond the domain of party competition, the supposed policy influence through election results does not emerge. Changes of the RR’s vote share point towards a restrictive direction, however the variable remains insignificant across model specifications. Considering the RR’s parliamentary presence by utilizing changes in the parliamentary seat share, the results remain insignificant. Overall, growing presence of RRP is linked to more restrictive reforms. The finding is consistent with Lutz (2019a), who similarly observes no significant effect of the RR’s vote share on immigration policy. Government participation by the RR shows a significant liberal effect in Model 2 and a significant restrictive effect in Model 4. The liberal finding is at odds with the prevailing expectations. However, neither finding is valid if the variable government participation is focused on the RR’s coalition participation only.29 Using this more stringent definition of incumbency, policy effects cannot be differentiated from zero. Null findings for the RR’s government participation are consistent with the evidence provided by case studies (Akkerman, 2012).

Turning to additional control variables, the lack of effects is predominant. Variables accounting for the factual pressure to address the issue like the share of the immigrant population, the level of unemployment, and the annual change of the GDP remain unrelated to changes of immigration and securitization legislation. The liberal effect of the proportion of immigrant population in Model 4 constitutes an exception. EU membership exerts a restrictive effect throughout different model specifications regarding immigration policy.

8 Conclusion

Building on the widely discussed assumption that RRP are influential political actors, the article investigates their indirect influence on the output of the legislative process. While the fact that RRP shape the discourse on immigration is well established, it remains an open question whether the RR is also influential regarding changes of legislation. Hence, the paper examines indirect policy effects through the interaction of salience and distance in policy preferences. Going beyond the RR’s electoral performance, the investigation reflects the potential policy influence of new parties more accurately than previous accounts.

The empirical analysis of changes of immigration policies illustrates two key findings. Firstly, indirect effects by the radical right on immigration are not a pivotal element. The executive branch and government partisanship are the main factors to explain policy reforms. In the event of conservative office holders, RRP, however, have the capacity to exert an indirect effect on legislative changes. Hence, the interplay of salience and distance in policy preferences has the potential to induce immigration reforms. The differentiated perspective on MP and RRP allows a comprehensive understanding of the party competition on immigration. Research concludes that the RR has a key role in the competition concerning immigration (Van der Brug and Berkhout, 2024), but the behavior of MP is also of pivotal significance. In accordance with recent scholarship (Han, 2022; Lehmann, 2024), the article generally casts doubt on claims that RRP are highly influential concerning policies and instead highlights the strategic role of MP, particularly the center-right.

Secondly, the analysis indicates the importance to account for the multidimensionality of immigration policy. The analysis underlines the exceptional character of securitization. Indirect effects of RRP are evident in this policy area. These effects are contingent upon conservative office holders. This part of the analysis remains exploratory, however. For future work, it is worthwhile to address the different aspects of immigration policy in more detail, both in theoretical and empirical respect. Schmid (2021) makes a valuable theoretical contribution in outlining the structural logics of immigration regimes. While initial evidence shows that motives of office holders differ depending on the sub-area of immigration (Kolbe, 2021), future scholarship should test whether similar dynamics also apply to new parties as predominantly opposition actors.

The quantitative analysis of policy effects of RRP would benefit from the inclusion of countries outside West European democracies. With reference to countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), research shows that the political controversy about immigration is of minor importance. As the establishment of RRP in CEE is less evolved, immigration is barely politicized in these countries (Hutter and Kriesi, 2022; Kovář, 2023). Therefore, indirect effects by the RR are generally less likely. A limitation relates to salience and distance in policy preferences. Manifestos have a bearing on parliamentary behavior over the course of a legislative period. However, alternative channels, like speeches or press releases, reflect daily political communication more closely. New parties regularly use these channels to promote own legislative proposals and to comment critically on draft legislation by the government. A potential effect of these more volatile communication channels on immigration policy remains unexplored. In view of the long-term legislative process, these short-term factors, however, are of minor relevance.

The findings provide a broader understanding of policy effects by new parties. The paper advances the debate on the RR’s legislative influence on immigration policy by focusing on indirect effects through salience and distance in policy preferences. Illustrating that new parties can under certain conditions have a long-lasting effect on immigration legislation due to their indirect effects, the paper provides an additional piece of evidence in the endeavor to map more accurately the policy influence of new parties in general and of RRP in particular.

Data availability statement

Information regarding the data sets and the replication file is available online (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JAT5WT). Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

VTZB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research of this article. The publication of this article was supported by the Open Access publication fund of the University of Bamberg.

Acknowledgments

The author is thankful to the editor and the reviewers who have helped to improve the article with their valuable comments. I would like to thank the Bamberg Graduate School of Social Sciences (BAGSS) for continuous support. An earlier version of this manuscript was presented at the DEMSCORE Conference 2024. I would like to thank all participants for the enriching discussion.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1529840/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The prevailing definitions of radical right parties exhibit a substantial degree of similarity, as these concepts consistently recognize an anti-immigration platform as a defining characteristic (Ivarsflaten and Gudbrandsen, 2014; Mudde, 2017). The designation of these actors as anti-immigration parties is based on this conceptual overlap (Van der Brug and Berkhout, 2024). In the subsequent course of the paper, the term radical right (parties) is employed in order to emphasize the distinct policy positions of these actors on socio-cultural issues such as immigration. Henceforth, the acronyms RR (radical right) and RRP (radical right parties) are used interchangeably. An overview of RRP included in the analysis can be found in Supplementary Table A.1.

2. ^The ongoing debate surrounding the definition of new parties remains unresolved (Rahat, 2025). Ideology is one of the multiple criteria discussed in the context of the classification of new parties. Ideology is defined as the ideological distinction between new and established parties (Kosowska-Gąstoł and Sobolewska-Myślik, 2023). This understanding is consistent with the concept of distance in policy preferences adopted by the paper. Consequently, RRP may be considered part of the conceptualization of new parties.

3. ^Ideological shifts by RRP are a recurring phenomenon (Carvalho, 2014).

4. ^In line with IMPIC’s conceptualization (Berger et al., 2024), general immigration policy is understood to encompass the five distinct sub-areas asylum and refugees, co-ethnics, control (securitization), family reunification, and labor migration.

5. ^The eleven countries that are covered are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

6. ^By contrast, Dancygier and Margalit (2020) report no evidence of contagion on the immigration stance of center-left and center-right MP. A similar finding of limited accommodation of positioning has been demonstrated in the analysis of press releases (Gessler and Hunger, 2022).

7. ^Applying issue uptake to West European democracies, political parties as the key actors in the electoral arena are the object of study.

8. ^Abou-Chadi’s (2016b) argument employs a similar line of reasoning. The interaction of salience and electoral competition has been demonstrated to result in a lower probability of liberal immigration reforms, when both factors are pronounced.

9. ^Countries, time periods, and RRP included in the analysis can be found in Supplementary Table A.1.

10. ^In the absence of data on RRP, it is not possible to calculate the variables on salience and distance in policy preferences. Consequently, the analysis encompasses 11 of the 12 countries included in the IPM dataset (Germany is not included based on absent data on RRP). Unavailable or uncoded manifestos limit the interval. A screening shows that the implicit assumption that manifesto data is missing at random appears justified.

11. ^Securitization of immigration comprises the following IPM categories: law and order, deportation, border protection, national security, overpopulation, and illegal immigration.

12. ^The analytical focus on center-left and center-right parties is consistent with the literature on party politics (see Han, 2022; Williams and Hunger, 2022).

13. ^The size of a party is determined by its vote share. The weighting of salience according to the vote share follows the rationale that the size of a party influences its capacity to shape the discourse on the issue.

14. ^In instances where missing values were observed for salience or distance in policy preferences, the calculation of average values was undertaken.

15. ^Predictor variables recorded in election years (e.g., salience and distance in policy preferences) remain constant during a legislative term. This is indicative of the understanding that manifestos serve as a guiding principle for government activities throughout the entire legislative period.

16. ^Incumbency status (including the RR’s external support to minority governments) applies to RRP in Austria (2000–2007); Denmark (2002–2011); the Netherlands (2010–2011); Norway (2002–2005; 2014–2017); and Switzerland (1999–2015).

17. ^Missing data on the immigrant population is complemented by IPM data.

18. ^With the exception of Norway and Switzerland, all countries included became EU member states by 1995 at the latest. This results in a low variance of this variable.

19. ^This statistical approach is customary when analyzing the IPM dataset (Dancygier and Margalit, 2020).

20. ^A correlation analysis between annual changes in immigration policy and securitization across the entire period 1980 to 2018 reveals a marginally diminished positive correlation (r = 0.15, p-value: 0.002).

21. ^Between 2001 and 2005, Italy had a salience level of above 5%.

22. ^Center-left and center-right MP do not differ significantly in their emphasis on immigration.

23. ^The salience of securitization does not differ significantly between RRP and the center-right (2.85% compared to 2.18%). The center-left addresses securitization significantly less frequently (1.37%).

24. ^Center-left MP are on average significantly more open to immigration than center-right MP (0.39 compared to a neutral stance of 0.04).

25. ^The average distance is 0.74 for the center-right and 1.13 for the center-left, a substantial value given the theoretical maximum of 2 in case of entirely restrictive RRP and a entirely liberal MP.

26. ^Securitization also demonstrates a considerable distance, albeit to a lesser extent than that observed in immigration policy (mean value = 0.48 for center-right and 0.59 for center-left). On average, all party types adopt a clearly restrictive stance on the sub-area (RR: −0.90, center-right: −0.42, center-left: −0.29).

27. ^This finding remains consistent when changes of the RR’s share of parliamentary seats are considered.

28. ^Results of the robustness checks are available upon request.

29. ^In contrast to the commonly used measurement of government participation of RRP, this more stringent measurement excludes the external support of governments by RRP.

References

Abou-Chadi, T. (2016a). Niche party success and mainstream party policy shifts. How green and radical right parties differ in their impact. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 46, 417–436. doi: 10.1017/S0007123414000155

Abou-Chadi, T. (2016b). Political and institutional determinants of immigration policies. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 42, 2087–2110. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1166938

Abou-Chadi, T., and Krause, W. (2020). The causal effect of radical right success on mainstream parties’ policy positions: a regression discontinuity approach. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 50, 829–847. doi: 10.1017/S0007123418000029

Akkerman, T. (2012). Comparing radical right parties in government: immigration and integration policies in nine countries (1996-2010). West Eur. Polit. 35, 511–529. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2012.665738

Akkerman, T. (2018). The impact of populist radical-right parties on immigration policy agendas: a look at the Netherlands. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute Report.

Akkerman, T., and de Lange, S. L. (2012). Radical right parties in office: incumbency records and the electoral cost of governing. Gov. Oppos. 47, 574–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2012.01375.x

Berger, V., Bjerre, L., Breyer, M., Helbling, M., Römer, F., and Zobel, M. (2024). The immigration policies in comparison (IMPIC) dataset: technical report V2. Berlin: WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

Biard, B. (2020). How do radical right populist parties influence resurging debates over the stripping of citizenship? Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 41, 224–237. doi: 10.1177/0192512118803733

Biard, B., Bernhard, L., and Betz, H.-G. (2019). Do they make a difference? The policy influence of radical right populist parties in Western Europe. London: ECPR Press/Rowman & Littlefield.

Bonjour, S., Ripoll Servent, A., and Thielemann, E. (2017). Beyond venue shopping and liberal constraint: a new research agenda for EU migration policies and politics. J. Eur. Public Policy 25, 409–421. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2016.1268640

Burscher, B., van Spanje, J., and De Vreese, C. H. (2015). Owning the issues of crime and immigration: the relation between immigration and crime news and anti-immigrant voting in 11 countries. Electr. Stud. 38, 59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2015.03.001

Carvalho, J. (2014). Impact of extreme right parties on immigration policy. Comparing Britain, France and Italy. London: Routledge.

Carvalho, J. (2016). The impact of extreme-right parties on immigration policy in Italy and France in the early 2000s. Comp. Eur. Polit. 14, 663–685. doi: 10.1057/cep.2014.47

Christiansen, F. J., and Seeberg, H. B. (2016). Cooperation between counterparts in parliament from an agenda-setting perspective. West Eur. Polit. 39, 1160–1180. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2016.1157744

Dancygier, R., and Margalit, Y. (2020). The evolution of the immigration debate: a study of party positions over the last half-century. Comp. Polit. Stud. 53, 734–774. doi: 10.1177/0010414019858936

Davis, A. J. (2012). The impact of anti-immigration parties on mainstream parties’ immigration positions in the Netherlands, Flanders and the UK 1987–2010. Florence: European University Institute.

Downes, J. F., Loveless, M., and Lam, A. (2021). The looming refugee crisis in the EU: right-wing party competition and strategic positioning. J. Common Mark. Stud. 59, 1103–1123. doi: 10.1111/jcms.13167

Freeman, G. P. (1994). Can liberal states control unwanted migration? Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 534, 17–30. doi: 10.1177/0002716294534001002

Froio, C., Bevan, S., and Jennings, W. (2017). Party mandates and the politics of attention: party platforms, public priorities and the policy agenda in Britain. Party Polit. 23, 692–703. doi: 10.1177/1354068815625228

Geddes, A., Hadj Abdou, L., and Brumat, L. (2020). Migration and mobility in the European Union. 2nd Edn. London: Red Globe Press.

Gessler, T., and Hunger, S. (2022). How the refugee crisis and radical right parties shape party competition on immigration. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 10, 524–544. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2021.64

Gordon, S. C., and Huber, G. A. (2007). The effect of electoral competitiveness on incumbent behavior. Q. J. Polit. Sci. 2, 107–138. doi: 10.1561/100.00006035

Green-Pedersen, C., and Otjes, S. (2019). A hot topic? Immigration on the agenda in Western Europe. Party Polit. 25, 424–434. doi: 10.1177/1354068817728211

Hadj-Abdou, L., Bale, T., and Geddes, A. P. (2022). Centre-right parties and immigration in an era of politicization. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 48, 327–340. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853901

Han, K. J. (2015a). The impact of radical right-wing parties on the positions of mainstream parties regarding multiculturalism. West Eur. Polit. 38, 557–576. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.981448

Han, K. J. (2015b). When will left-wing governments introduce liberal migration policies? An implication of power resources theory. Int. Stud. Q. 59, 602–614. doi: 10.1111/isqu.12156

Han, K. J. (2022). Radical right success and mainstream parties’ position ambiguity on immigration. Acta Polit. 57, 818–835. doi: 10.1057/s41269-021-00227-2

Heinze, A.-S. (2017). Strategies of mainstream parties towards their right-wing populist challengers: Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland in comparison. West Eur. Polit. 41, 287–309. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2017.1389440

Helbling, M., Abou-Chadi, T., Berger, V., Bjerre, L., Breyer, M., Römer, F., et al. (2024). Immigration policies in comparison (IMPIC) database v2. Available online at: http://www.impic-project.eu/data/ (Accessed April 18, 2024).

Helbling, M., and Meierrieks, D. (2020). Transnational terrorism and restrictive immigration policies. J. Peace Res. 57, 564–580. doi: 10.1177/0022343319897105

Hellström, J., Bergman, T., Lindahl, J., and Sychowiec, M. (2023). Party government in Europe database (PAGED) basic dataset, version 2023.12. Available online at: https://repdem.org/index.php/current-dataset/ (Accessed April 18, 2024).

Hobolt, S. B., and De Vries, C. E. (2015). Issue entrepreneurship and multiparty competition. Comp. Polit. Stud. 48, 1159–1185. doi: 10.1177/0010414015575030

Hutter, S., and Kriesi, H. (2022). Politicising immigration in times of crisis. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 48, 341–365. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853902

Ivarsflaten, E., and Gudbrandsen, F. (2014). “The populist radical right in Western Europe” in The Europa regional surveys of the world 2014. ed. Europa Publications (London: Routledge), 1–5.

Kolbe, M. (2021). Who liberalizes high-skilled immigration policy and when? Partisanship and the timing of policy liberalization in 19 European states. Ethnic Racial Stud. 44, 618–638. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2020.1755048

Kosowska-Gąstoł, B., and Sobolewska-Myślik, K. (2023). How can one assess the level of party newness, continuity, and change? Some examples from Poland. East. Eur. Polit. Soc. 37, 950–982. doi: 10.1177/08883254221132289

Kovář, J. (2023). Politicisation of immigration in central and Eastern Europe: evidence from plenary debates in two countries. Probl. Post-Communism 70, 667–678. doi: 10.1080/10758216.2022.2085579

Lehmann, F. (2024). Why accommodate? How niche pressure and intra-party divisions shape mainstream party strategies. J. Eur. Public Policy 31, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2024.2408320

Lutz, P. (2019a). Variation in policy success: radical right populism and migration policy. West Eur. Polit. 42, 517–544. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2018.1504509

Lutz, P. (2019b). “The radical right in power: a comparative analysis of their migration policy influence” in Do they make a difference? The policy influence of radical right populist parties in Western Europe. eds. B. Biard, L. Bernhard, and H.-G. Betz (London: ECPR Press/Rowman & Littlefield), 251–271.

Lutz, P. (2024). Allowing mobility and preventing migration? The combination of entry and stay in immigration policies. West Eur. Polit. 47, 840–866. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2023.2185852

Meguid, B. M. (2005). Competition between unequals: the role of mainstream party strategy in niche party success. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 99, 347–359. doi: 10.1017/S0003055405051701

Minkenberg, M., and Végh, Z. (2023). Depleting democracies. Radical right impact on parties, policies, and polities in Eastern Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Mudde, C. (2013). Three decades of populist radical right parties in Western Europe: so what? Eur J Polit Res 52, 1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02065.x

Mudde, C. (2017). “Introduction to the populist radical right” in The populist radical right. A reader. ed. C. Mudde (New York: Routledge), 1–10.

Natter, K., Czaika, M., and de Haas, H. (2020). Political party ideology and immigration policy reform: an empirical enquiry. Polit. Res. Exch. 2, 1–27. doi: 10.1080/2474736X.2020.1735255

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2024). OECD Data Explorer. Available online at: https://data-explorer.oecd.org (Accessed April 18, 2024).

Petrocik, J. R. (1996). Issue ownership in presidential elections, with a 1980 case study. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 40, 825–850. doi: 10.2307/2111797

Rahat, G. (2025). What constitutes a new party? The lack of a standard operationalization and the way forward. Front. Polit. Sci. 7, 1–4. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1495732

Schain, M. A. (2006). The extreme-right and immigration policy-making: measuring direct and indirect effects. West Eur. Polit. 29, 270–289. doi: 10.1080/01402380500512619

Schmid, S. D. (2021). Do inclusive societies need closed borders? The association between immigration and citizenship regimes. Florence: European University Institute.

Schumacher, G., and van Kersbergen, K. (2016). Do mainstream parties adapt to the welfare chauvinism of populist parties? Party Polit. 22, 300–312. doi: 10.1177/1354068814549345

Taggart, P., and Szczerbiak, A. (2013). Coming in from the cold? Euroscepticism, government participation and party positions on Europe. J. Common Mark. Stud. 51, 17–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2012.02298.x

Van der Brug, W., and Berkhout, J. (2024). Patterns of politicization following triggering events: the indirect effect of issue-owning challengers. Front. Polit. Sci. 6, 1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1314217

Van der Brug, W., D'Amato, G., Berkhout, J., and Ruedin, D. (2015). “A framework for studying the politicisation of immigration” in The politicisation of migration. eds. W. Van der Brug, G. D'Amato, D. Ruedin, and J. Berkhout (London: Routledge), 1–18.

Van Spanje, J. (2010). Contagious parties. Anti-immigration parties and their impact on other parties’ immigration stances in contemporary Western Europe. Party Polit. 16, 563–586. doi: 10.1177/1354068809346002

Verbeek, B., and Zaslove, A. (2015). The impact of populist radical right parties on foreign policy: the northern league as a junior coalition partner in the Berlusconi governments. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 7, 525–546. doi: 10.1017/S1755773914000319

Williams, M. H. (2006). The impact of radical right-wing parties in West European democracies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Williams, M. H. (2015). Are radical right-wing parties the black holes in party space? Implications and limitations in impact assessment of radical right-wing parties. Ethn. Racial Stud. 38, 1329–1338. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2015.1015933

Keywords: radical right parties, immigration policy, securitization, policy change, party competition, west european democracies

Citation: Berger VTZ (2025) New parties, new policies? The influence of radical right parties on immigration policies. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1529840. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1529840

Edited by:

Marco Lisi, NOVA University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Euel Elliott, The University of Texas at Dallas, United StatesJohn Eaton, Florida Gateway College, United States

Copyright © 2025 Berger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Valentin Tim Zacharias Berger, dmFsZW50aW4uYmVyZ2VyQHVuaS1iYW1iZXJnLmRl

Valentin Tim Zacharias Berger

Valentin Tim Zacharias Berger