- Department of Humanities and Social Science, RUDN University, Moscow, Russia

The resurgence of modern slavery in Libya, marked by the commodification of migrants in detention centers and open-air markets, reflects systemic global inequalities and geopolitical complicity. Using Marxist analysis and a Libya case study, this qualitative study draws on NGO and IGO reports (IOM, MSF, HRW) to reveal how neoliberal capitalism, imperialist interventions, and racial hierarchies sustain trafficking. NATO’s 2011 overthrow of Gaddafi dismantled Libya’s welfare state, enabling militias to privatize oil wealth (85% of revenues) and exploit migration routes. EU policy initiatives between 2017 and 2023 allocated €455 million in funding to Libyan militias, resulting in the interception of 38,000 migrants on the Mediterranean by these militias groups. This cooperation coincided with human rights violations, including torture and forced labor inflicted on 73% of intercepted individuals, alongside a concurrent rise in Mediterranean crossing fatality rates to 1 in 23 during this period. The UN’s reliance on militia cooperation and the AU’s inadequate response perpetuate impunity. Marxist critique frames sub- Saharan Africans, displaced by IMF austerity and climate crises, as capitalism’s “reserve army,” reduced to disposable labor. Racial capitalism exacerbates this, with Black migrants facing disproportionate enslavement. Libya’s fragmentation into rival factions (GNA, HoR/LNA, militias) and corporate complicity, e.g., ENI’s oil extraction via traffickers highlight international culpability. The study recommends redirecting EU funds to Sahelian climate resilience, prosecution of traffickers and corporations via ICC/Magnitsky sanctions, empowerment of local governance, expansion of legal migration pathways, and enforcement of binding corporate accountability. Libya’s crisis epitomizes global capitalism’s moral bankruptcy, demanding structural equity to prioritize dignity over profit.

Introduction

From the 17th to the 19th century, the transatlantic slave trade saw millions of Africans forcibly transported to the Americas under conditions of brutal exploitation and dehumanization, marking a shameful era in human history (Klein, 2010). While the formal abolition of slavery occurred over a century ago, its legacy persists in various forms of coercion and exploitation that remain prevalent today (Murphy, 2019). One alarming manifestation of modern slavery is found in Libya, where conflict and instability have allowed this practice to reemerge. The fall of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 created a vacuum of governance and order, leading to chaotic conditions that human traffickers and armed groups have exploited. Migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, often escaping dire economic circumstances and violence, have been particularly vulnerable to these predators (Lewis et al., 2021; Adepoju, 2008).

In 2017, reports emerged of open slave markets in Libya, where people, among them children and older people, were being traded as mere commodities (BBC News, 2017). The reappearance of slavery in Libya starkly highlights the widespread, ongoing exploitation in today’s world. To comprehend the scope of this issue, it is essential to examine the modern Libyan slave trade in depth, investigating its origins, the factors enabling its persistence, and the severe impact it has on victims. This article aims to provide an account based on the Marxist approach of the resurgence of slave trade in Libya, seeking to deepen our understanding of contemporary human trafficking by examining the structural factors at play and the human cost involved.

Theoretical framework

The resurgence of slavery in Libya, beginning around 2015, demands an analysis that goes beyond humanitarian concerns alone. A Marxist perspective sheds light on the structural inequalities within the global capitalist system that underline this exploitation. This section will explore the core principles of Marxist theory as they apply to the Libyan crisis, highlighting how the slave trade reflects broader systemic issues. Founders of Marxist thought, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels argued that capitalism inherently produces class struggles and exploitation, primarily by extracting surplus value where workers receive less than the value they create. This drive to maximize profits can result in the degradation and dehumanization of workers, and this dynamic extends beyond formal economies to areas where labor is commodified solely for profit. World- systems theory, a derivative of Marxist analysis, expands this view to a global scale, emphasizing a core-periphery relationship in which wealthier core nations exploit peripheral nations for cheap labor and resources (Wallerstein, 1974). In this framework, Libya’s contemporary slave trade can be understood as an outcome of global inequality and economic exploitation.

A Marxist analysis of Libya’s slave trade reveals several critical assumptions

A Marxist analysis of Libya’s slave trade underscores the systemic violence of capitalist accumulation, and the commodification of migrants within a global hierarchy of value extraction, where the interplay of economic desperation, state collapse, and transnational profit-seeking converges to produce conditions akin to modern-day bondage (Poulantzas and Hall, 1978). Migrants, often fleeing poverty and instability exacerbated by neo-colonial economic policies, are funneled into informal labor markets where their status as undocumented workers render them hyper-exploitable. Silvia Federici’s analysis of the dehumanization of labor under capitalism, particularly her examination of how marginalized bodies are rendered ungrievable within global production chains, resonates here (Federici, 2004). Reports of forced labor, torture, and debt bondage in Libya illustrate this dynamic, as migrants, many from sub-Saharan Africa, are entrapped in cycles of exploitation where their labor is extracted at near-zero cost, mirroring Marx’s concept of absolute surplus value (Marx, 1867; HRW (Human Rights Watch), 2017).

The global inequality underpinning this system cannot be disentangled from the legacies of imperialism and the capitalist world-system described by Immanuel Wallerstein, wherein peripheral nations like Libya occupy a subordinate position in the global economy, their instability manipulated by core states and multinational interests (Wallerstein, 1974). Samir Amin’s critique of unequal development further clarifies how structural adjustment programs and resource extraction in sub-Saharan Africa have deepened poverty, displaced populations, and pushed them into perilous migration routes (Amin, 1976). While some actors, such as corrupt officials, directly profit from this system, a Marxist lens emphasizes that their actions are enabled by a global order prioritizing capital mobility over human rights. The extraction of surplus value from migrants through unpaid labor or sexual violence exemplifies what Marx identified as capitalism’s inherent drive to reduce labor to a mere cost of production (Marx, 1867). This process is racialized and gendered, with Black migrants from sub-Saharan Africa facing heightened vulnerability, a reality echoing Cedric Robinson’s theory of racial capitalism, which posits that capitalism emerged and thrives through racial hierarchies and colonial violence (Robinson, 1983).

To frame Libya’s crisis as an isolated aberration obscures its roots in transnational capitalist exploitation. The European Union’s externalization of border controls, for instance, has funneled migration flows through Libya, where EU-funded militias intercept migrants, effectively outsourcing violence to maintain Fortress Europe’s boundaries (Andersson, 2014). This complicity underscores Antonio Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, wherein dominant powers secure consent for exploitation through both coercion and ideological mechanisms, normalizing the dehumanization of racialized labor (Gramsci, 1971). The conflation of terms like trafficking and smuggling in policy discourse further obfuscates the structural nature of exploitation, reducing systemic violence to criminal aberrations rather than outcomes of capitalist logic.

Contextualization of the study

Clarifications of terms

The slave trade, defined as the systematic capture, transport, and commodification of human beings through coercion or violence for economic gain, represents a continuum of exploitation rooted in historical and modern contexts. Historically epitomized by the transatlantic trade, in which millions of Africans were forcibly displaced to the Americas via triangular trade routes, this practice institutionalized the dehumanization of individuals as property (Ilesanmi and Iyer-Raniga, 2024). Contemporary manifestations, however, diverge in structure, operating within informal economies and transnational criminal networks. For instance, in post-2011 Libya, the collapse of governance has enabled open-air markets where migrants—many fleeing conflict or climate- induced displacement are traded for labor, sexual exploitation, or ransom (Didier et al., 2022). This modern iteration reflects a commodification process that, while lacking the legal frameworks of historical chattel slavery, perpetuates analogous cycles of dehumanization and profit.

Closely related to the slave trade is forced labor, a subset characterized by work extracted through force, fraud, or coercion. While forced labor emphasizes compulsion, the slave trade centers on the transactional exchange of humans as commodities. These concepts intersect in contexts such as Libya, where migrants detained by militias are forced into construction or agricultural labor under brutal conditions, their exploitation embedded within broader networks of human trafficking (Didier et al., 2022). Forced labor practices like debt bondage or domestic servitude (Palumbo, 2024) thus function as both outcomes and enablers of the slave trade, illustrating how systemic violence sustains profit-driven hierarchies.

Human trafficking, meanwhile, encompasses the recruitment and movement of individuals for exploitation, overlapping with but extending beyond the slave trade. While trafficking includes diverse purposes—from organ harvesting to sexual exploitation—its methods of abduction and deception often facilitate the commodification central to slave trade dynamics. The racialized dimensions of trafficking are evident in Libya, where sub-Saharan Africans, displaced by intersecting crises, are funneled into detention centers operated by militias and state-aligned actors. These individuals are subsequently sold into forced labor or sexual slavery, a process that underscores how global migration routes intersect with systemic exploitation (Karasapan and Sajjad, 2018). Here, trafficking operates as both a mechanism and a consequence of the slave trade, reinforcing cycles of marginalization.

Extreme exploitation, a concept that encapsulates labor conditions marked by severe abuse, negligible remuneration, and life-threatening environments, further contextualizes these phenomena. In Marxist terms, such exploitation reflects the extraction of “surplus value” through the dehumanization of vulnerable populations. Libya’s detention centers exemplify this: migrants endure torture, forced labor, and sexual violence while contributing to supply chains linked to European markets (Didier et al., 2022). This extreme exploitation not only maximizes profit for militias and their collaborators but also reveals how capitalist imperatives intersect with militarized economies to perpetuate modern slave trade networks.

The Libyan case thus serves as a microcosm of the interplay between these concepts. State collapse, compounded by international policies such as EU-funded migration interdiction efforts, has created an ecosystem where trafficking, forced labor, and extreme exploitation converge. Migrants intercepted by the Libyan Coast Guard are cycled into detention systems where their commodification—whether through sale, extortion, or coerced labor—mirrors historical slave trade patterns, albeit within a fragmented, neoliberal global order. This illustrates the enduring legacies of systemic violence, where structural inequalities and transnational complicity sustain contemporary forms of human commodification.

Overview of Libya’s political and social post-Gaddafi (2011) landscape

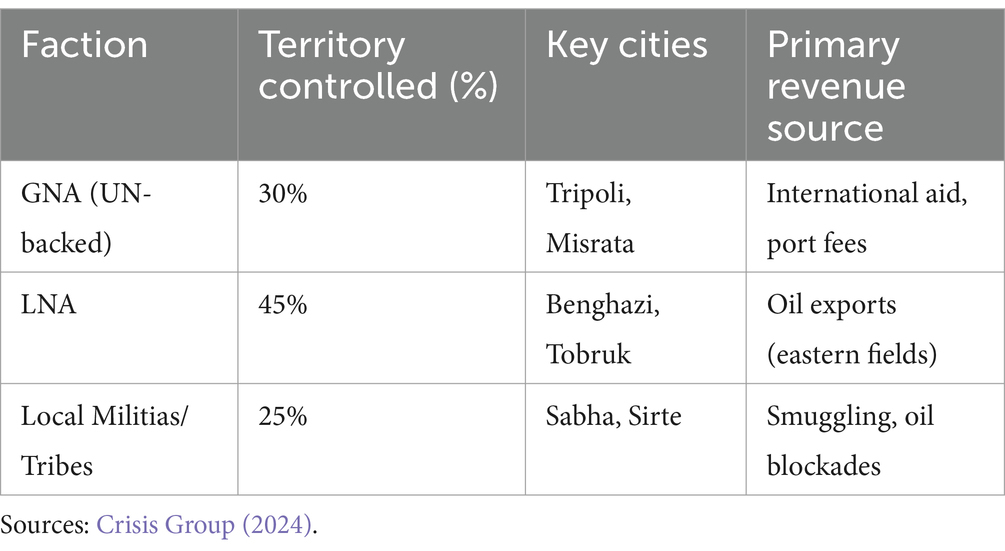

The collapse of Muammar Gaddafi’s regime in 2011 triggered a decade of political chaos, with Libya fractured into competing power centers as three entities vie for legitimacy (Table 1).

The Second Libyan Civil War (2014–2019) marked a critical escalation in Libya’s fragmentation, driven by General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) and his bid to consolidate power under the banner of eradicating terrorism. Haftar’s offensive to capture Tripoli in 2019, dubbed Operation Flood of Dignity, was not merely a military campaign but a calculated attempt to leverage international anti-Islamist sentiment to legitimize his rule. Backed by the UAE, Russia, and Egypt, the LNA deployed advanced weaponry, including drones and Wagner Group mercenaries, transforming the conflict into a proxy war (Selján, 2020). However, the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA), an interim Government for Libya formed under the terms of the UN-sponsored Libyan political agreement, signed on the 17th December 2015 and supported by Turkey and Qatar, repelled the assault using Syrian mercenaries and Turkish drones, resulting in over 2,500 fatalities and displacing 150,000 civilians (ACLED (Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project), 2024).

The fragmentation of Libya’s political and social fabric escalated dramatically following the outbreak of civil war in 2014, a conflict that entrenched regional divides and unleashed devastating humanitarian consequences. The violence, particularly during General Khalifa Haftar’s 2019–2020 siege of Tripoli, resulted in over 2,500 fatalities and displaced more than 400,000 Libyans, many of whom remain unable to return home due to persistent insecurity and destroyed infrastructure (UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), 2023). This displacement crisis has strained public services to breaking point: by 2023, only 35% of hospitals in conflict-affected areas were fully operational, while 82% of schools in cities like Benghazi and Sirte lay in ruins, depriving a generation of education (UNICEF, 2023).

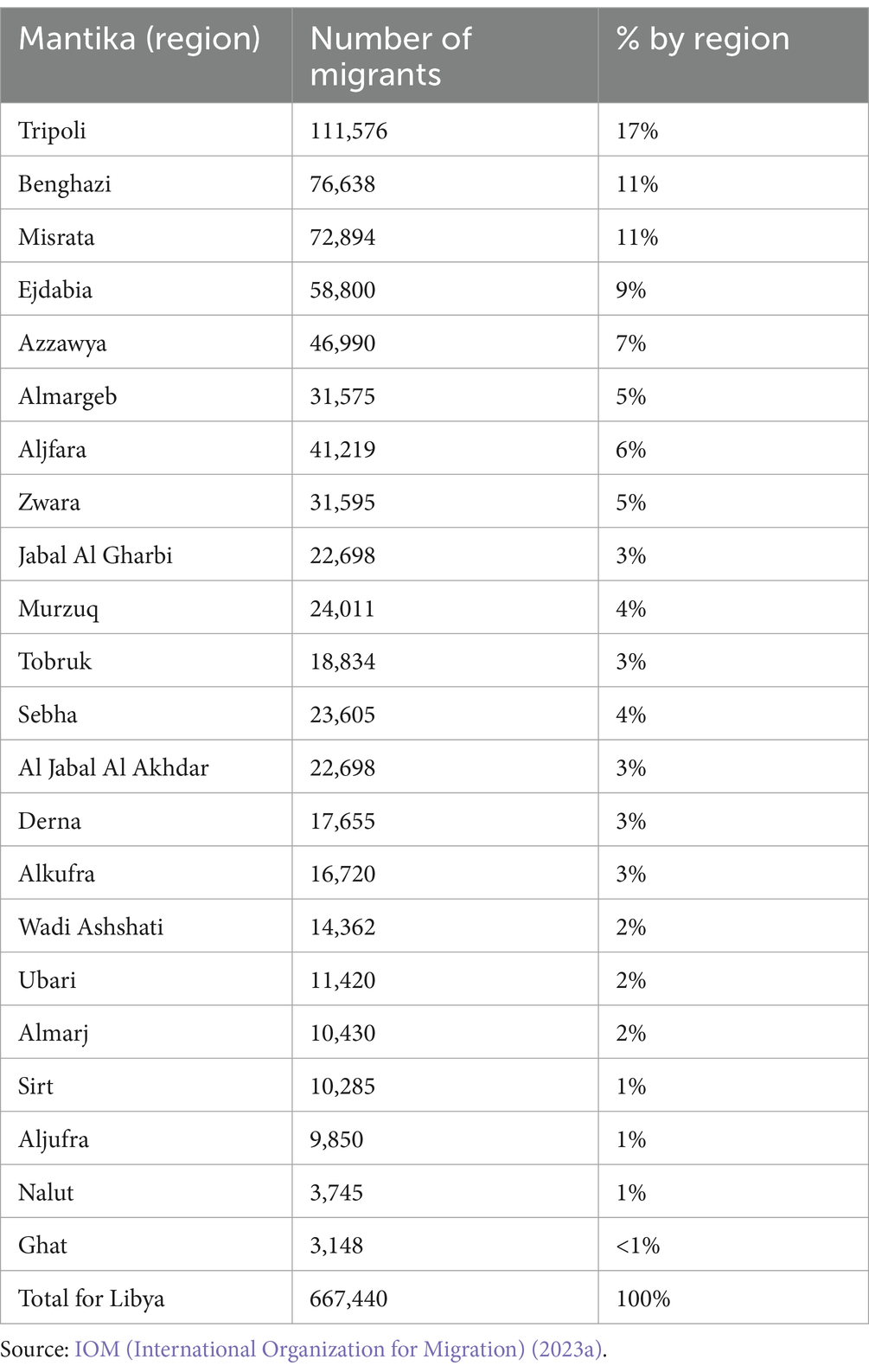

Simultaneously, Libya’s role as a nexus for migration routes amplified the crisis. By 2023, an estimated 700,000 migrants and refugees, primarily from sub-Saharan Africa, were trapped in the country, many subjected to exploitation in detention centers or forced labor (IOM, 2023) (Table 2).

The EU’s policy of outsourcing border control to Libyan militias, which intercepted 38,000 migrants in 2023 alone, has effectively turned Libya into an open-air prison. Reports indicate that 73% of detained migrants face torture, extortion, or sexual violence, with smuggling networks in cities like Sabha operating with impunity (ECCHR, FIDH, LFJL, 2021). This confluence of internal displacement and migration pressures has shattered social cohesion. Tribal and regional loyalties have supplanted national identity, with 67% of Libyans expressing greater trust in local tribal leaders than in any government (Onitiri, 2023). The governance vacuum has allowed armed groups to monopolize resources from oil revenues to humanitarian aid, deepening public disillusionment. For instance, 2022, militias siphoned $60 billion from blocked oil exports, exacerbating inflation and unemployment, which stood at 31% (World Bank, 2023; UNSC (United Nations Security Council), 2023). In essence, the 2014 civil war did not merely deepen existing divides; it catalyzed a self- perpetuating cycle of instability, where political rivalries, economic collapse, and humanitarian suffering reinforce one another. The international community’s focus on containment over resolution has only prolonged the crisis, leaving Libyans and migrants alike ensnared in a landscape of unaccountable power and systemic violence.

Causes of the new slave trade in Libya

The resurgence of slavery in post-2011 Libya, characterized by the brazen commodification of migrants in open-air markets and squalid detention centers, stands as a grotesque testament to the exploitative machinery of global capitalism. Marxist theory, which diagnoses capitalism as a system sustained by extracting surplus value from marginalized labor, offers a piercing lens to dissect this crisis (HRW (Human Rights Watch), 2017). Far from an isolated barbarity, Libya’s slave trade is a logical outcome of neoliberal globalization, imperialist intervention, and the deliberate creation of a racialized underclass. This process lays bare capitalism’s reliance on dehumanization for profit.

Marx’s concept of the reserve army of labor is at the heart of this tragedy, a surplus population stripped of rights and reduced to expendable commodities (Kadri, 2020). Sub-Saharan African migrants, displaced by climate catastrophes, war, and IMF-imposed austerity in nations like Niger and Chad, are funneled into Libya as stateless laborers. Denied legal protections, they become fodder for an informal economy controlled by militias. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) reveals that 73% of migrants in Libya endure forced labor, toiling on construction sites, farms, or within detention centers where their subjugation generates profit for armed groups (IOM, 2023). This systemic exploitation mirrors Marx’s notion of primitive accumulation, where violence, not market exchange, transforms human beings into tradable goods. In cities like Sabha, people are sold for as little as $200–500 (CNN, 2017), their bodies commodified to enrich traffickers and militia networks. The UN Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) estimates that armed groups earn $1 billion annually from trafficking and EU-funded detention contracts (UNSMIL, 2021), while a 2023 Human Rights Watch report ties these centers to global supply chains, with migrants coerced into producing goods for European markets.

The 2011 NATO-led overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi, masquerading as a humanitarian intervention, catalyzed this descent into barbarism. For all its flaws, Gaddafi’s regime had leveraged oil wealth to fund free housing, healthcare, and education. Post-intervention, IMF austerity measures gutted public services, plunging 60% of Libyans into poverty (World Bank, 2023). This neoliberal dismantling birthed a desperate underclass while foreign-backed militias privatized state assets, seizing control of 85% of Libya’s oil revenues (UN Panel of Experts, 2023). These militias, functioning as de facto capitalist enterprises, now bankroll detention centers where migrants are exploited as disposable labor (HRW (Human Rights Watch), 2017) a stark illustration of Marx’s warning that capitalism reduces human dignity to exchange value.

Imperialist complicity further entrenches this cycle. This policy, framed as migration management, exemplifies what Marxist scholars call racial capitalism, a system that renders Black and Brown bodies hyper-exploitable through racist hierarchies. Migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, deemed expendable by design, are brutalized to sustain profits for Libyan militias and European firms alike. Italy’s energy giant ENI, for instance, continues extracting oil from fields guarded by traffickers’ slavery (Tjønn and Lemberg, 2022), embodying the collusion between corporate capital and state-sponsored violence. Underpinning this exploitation are global capitalist institutions. Structural adjustment programs imposed by the IMF on migrants’ home countries, such as cuts to fuel subsidies in Sudan, deepen poverty, propelling desperate populations into lethal migration routes. Meanwhile, the World Bank’s, 2023 report underscores how Libya’s economic collapse, engineered by foreign-backed conflict over resources, normalizes labor exploitation.

Libya’s trafficking is not a relic of premodern brutality, but a distinctly modern atrocity forged by capitalist logic. It thrives because global systems devalue Black lives, prioritize profit over humanity, and outsource violence to the periphery. Marx’s indictment of capitalism as a system that drips from head to toe, from every pore, with blood and dirt finds grim validation in Sabha’s markets and Tripoli’s detention centers. Dismantling this horror demands more than humanitarian aid; it requires abolishing the global economic order that treats human beings as raw material for extraction. Only by confronting the root structures of capitalist imperialism can we dismantle the machinery of exploitation that fuels Libya’s suffering.

Human trafficking in Libya

Far from being an isolated criminal enterprise, Libya’s human trafficking crisis reflects a convergence of predatory capitalism, geopolitical maneuvering, and the failure of international institutions, with its scale and features deeply rooted in transnational systems of exploitation. The phenomenon spans a vast network, with Libya serving as both a destination and transit hub for migrants and refugees primarily from sub- Saharan Africa, including Niger, Sudan, Chad, Nigeria, who are trafficked for forced labor, sexual exploitation, and ransom-based extortion, according to a CNN (2022) journalist who conducted a hidden camera investigation near Tripoli, the capital city. Slave markets that would take place once or twice a month were thus brought to light; markets where human beings are sold like trinkets to the highest bidder who then uses them as tools in his or her farm(s) or factory(ies). This phenomenon has been normalized and makes it possible to drastically reduce production costs and increase turnover, since there is no longer any need to deduct the wage cost. As of 2023, an estimated 700,000 migrants were trapped in Libya, including 48,000 children, with 65% subjected to forced labor and 33% enduring sexual violence, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM, 2023; Amann, 2024). Gender plays a critical role in shaping vulnerabilities: women and girls, constituting 27% of detected trafficking victims in North Africa, are disproportionately targeted for sexual exploitation (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2022), often sold in markets like Sabha for $400–$1,000, while men are funneled into construction, agriculture, or informal sectors where brutal working conditions mirror modern slavery (OHCHR (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights), 2021).

The trafficking pipeline begins in regions destabilized by climate crises, armed conflict, and economic collapse, such as the Sahel, where droughts and resource scarcity have displaced millions. Migrants fleeing these conditions traverse perilous routes through Niger and Chad, where anti-smuggling laws funded by the EU since 2015 have diverted flows into Libya’s ungoverned spaces, heightening exposure to traffickers (Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 2021). Upon arrival, sub-Saharan Africans face systemic racialized exploitation: 52% of trafficking victims in Libya are from this region, compared to 40% from North Africa and 8% from Middle East and Asia (IOM, 2023), a disparity underscoring how racial capitalism devalues Black lives. Traffickers and militias, such as the Stability Support Apparatus (SSA), exploit these racial disparity, detaining migrants in over 30 official and hundreds of clandestine sites where torture, forced labor, and organ harvesting have been documented (Geray, 2024).

The EU’s border externalization policies have institutionalized this cycle. Between 2017 and 2023, €455 million in EU funding fortified the Libyan Coast Guard’s capacity to intercept over 100,000 migrants, funneling them into detention centers where 73% faced torture or extortion (De Leo, 2024). These centers, often militia-operated, serve as nodes in a transnational economy: migrants are coerced into contacting families for ransoms averaging $1,000–$5,000, with profits reinvested into arms and trafficking operations (World Bank, 2023; UN Security Council, 2023). Meanwhile, European corporations like Italy’s Aeneas and energy giants ENI and Total Energies profit from militia-linked contracts, constructing luxury infrastructure with forced labor while extracting oil from facilities guarded by traffickers (Tjønn and Lemberg, 2022). This complicity extends to the UN, whose Libya mission (UNSMIL) relies on militia cooperation for access, tacitly legitimizing perpetrators (HRW, 2023).

The crisis is further gendered through the commodification of reproductive labor. Women detained in centers like Triq al-Sikka are forced into domestic servitude, with survivors reporting pregnancies from systematic rape, a tactic of control that echoes patriarchal capitalist structures (Amnesty International, 2022). Children, comprising 7% of Libya’s migrant population, are exploited for begging and drug trafficking or sold to underground adoption networks (IOM (International Organization for Migration), 2023b). These intersections of gender, race, and class reveal trafficking not as a series of isolated crimes but as a mode of accumulation under global capitalism, where vulnerability is manufactured through neo-colonial policies, militarized borders, and corporate greed. Libya’s trafficking economy, generating up to $323 million annually, thrives because it is embedded in a global order that treats migrants as disposable inputs (Global Financial Integrity, 2021). Dismantling this system demands confronting its root causes: the climate collapse displacing Sahelian communities, the arms trade fueling militia dominance, and the EU’s border regime outsourcing violence. Until these structures are challenged, human trafficking will persist as a grotesque feature of an interconnected world-one where the value of human life is dictated by profit.

International response to the new slave trade in Libya

The international response to Libya’s modern slave trade has been a study in stark contradictions: public condemnations of trafficking coexist with policies that perpetuate exploitation, revealing a systemic hypocrisy rooted in geopolitical interests and economic pragmatism (BBC News, 2017). While institutions like the United Nations and European Union espouse commitments to human rights, their actions or inactions often deepen the crisis they claim to resolve.

Since 2017, the European Union has allocated €455 million to Libya under the guise of “managing migration,” primarily funding the Libyan Coast Guard to intercept migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean. In 2023 alone, these EU-trained forces intercepted 38,000 migrants, 87% of whom were funneled into detention centers. A damning 2023 report by Forensic Oceanography (2023) revealed that Frontex, the EU’s border agency, shares surveillance data with Libyan militias, directly enabling interceptions that feed trafficking networks. Meanwhile, a token €80 million in humanitarian aid for shelters and voluntary returns has done little to offset the harm, with only 60,000 migrants repatriated since 2017. Corporate profiteering further stains the EU’s record. Italian construction firm Aeneas and French security giant Sopra Steria secured lucrative EU contracts to build and manage detention infrastructure in Libya, despite evidence linking these facilities to militia abuses. According to Sunderland (2023), the EU has effectively “outsourced torture,” prioritizing border containment over the non-refoulement principle a cornerstone of international law.

To access detention centers in Libya, the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) engages in dialogue with local armed groups, including the support apparatus, a Tripoli-based force. While such engagement is part of the UN’s operational effort to facilitate humanitarian access, the SSA has faced allegations of involvement in human trafficking. However, negotiating with groups accused of rights abuses risks inadvertently legitimizing their activities highlighting the complex dynamics of operating in conflict zones.

The African Union has condemned trafficking but lacks the political will to address its root causes. Its 2017 joint task force with the EU and UN evacuated just 4,000 migrants by 2023- a drop in the ocean compared to the 700,000 trapped in Libya. The AU’s 2018 Migration Policy Framework, while progressive on paper, remains unfunded and ignores structural drivers like EU extractive policies in the Sahel, which displace millions into trafficking routes. Humanitarian organizations like Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and Human Rights Watch (HRW) have courageously exposed abuses. MSF’s 2023 report revealed that 73% of detainees in Tripoli’s Al-Mabani center endure torture, with 40% suffering malnutrition. Yet their efforts are increasingly stifled: in 2022, Libyan authorities expelled MSF from Misrata, accusing it of “encouraging migration.” While the International Organization for Migration (IOM) facilitates voluntary returns, such efforts are dwarfed by the scale of exploitation, underscoring the limits of humanitarian band-aids.

Individual states have taken selective accountability measures. The U.S. sanctioned Libya’s Al-Nasr Martyrs Brigade in 2020 for trafficking, and the ICC’s Prosecutor Karim Khan pledged in 2023 to investigate slavery as crimes against humanity, however, these measures target low-level actors. The European Union has imposed targeted sanctions on the Wagner Group and its leaders, such as Yevgeny Prigozhin and commanders Aleksandr Kuznetsov and Dmitriy Utkin, for their destabilizing role in Libya, including arms embargo violations, human rights abuses, and collusion with warlord Khalifa Haftar. These measures, however, have been criticized for focusing disproportionately on mid-level actors and commercial front companies while avoiding accountability for regional powers like the UAE and Turkey, which have armed opposing Libyan factions and deepened the conflict. Despite Wagner’s rebranding into new entities like the Expeditionary Corps to evade sanctions, the EU has struggled to address the group’s systemic evasion tactics or its reliance on proxy networks in Libya, such as subcontracting migrant detention and resource looting to local militias (European Union, 2023; Smith, 2024).

The international response is riddled with contradictions. The EU funds abuse while touting humanitarian values; the UN condemns trafficking but collaborates with perpetrators; the AU advocates for rights but lacks political will. A 2022 EU “Protection Services” program designed to improve detention conditions saw €10 million diverted to militia-linked contractors—a microcosm of systemic failure. Meaningful change demands a fundamental shift in approach. The EU must end its funding to Libyan militias and redirect resources to climate resilience in the Sahel to reduce forced migration. The ICC must prosecute high-ranking militia leaders and foreign enablers under international law. Finally, global wealth redistribution is essential, dismantling IMF austerity and extractive policies that displace vulnerable populations. As Libyan activist Hameda al-Magariaf starkly observed: The world sees our suffering but profits from it. Until the global north confronts its role in perpetuating trafficking through border policies, corporate greed, and militarized intervention, Libya will remain a grotesque symbol of international failure.

Discussion

The resurgence of slavery in Libya is not an isolated phenomenon but a symptom of global systems that prioritize profit over human dignity. This crisis, rooted in neoliberal capitalism, imperialist interventions, and racialized exploitation, exposes the profound contradictions of the international order. While institutions like the European Union (EU) condemn human trafficking in rhetoric, their policies of funding abusive militias, outsourcing border control, and prioritizing geopolitical stability perpetuate the very systems they claim to oppose. To dismantle this cycle of exploitation, it is critical to confront the structural drivers of Libya’s slave trade, critique the failures of international institutions, and chart actionable pathways toward justice.

Structural drivers: capitalism, imperialism, and racial hierarchy

Libya’s descent into lawlessness after the 2011 NATO-led intervention created a vacuum where militias and traffickers commodified human lives with impunity. However, this chaos was not inevitable. Three intersecting forces engineered it:

Neoliberal Dismantling: The overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi, framed as a humanitarian intervention, dismantled Libya’s welfare state. Post-regime change, International Monetary Fund (IMF) austerity measures gutted public services, plunging 60% of Libyans into poverty. Foreign-backed militias privatized the country’s oil wealth, capturing 85% of revenues and transforming state assets into tools of exploitation (World Bank, 2023).

Global Capitalism’s Reserve Army: Sub-Saharan African migrants, displaced by intersecting crises of climate collapse and IMF-imposed austerity programs in their home countries, constitute a surplus labor pool exploited within Libya’s informal economy. IMF structural adjustment mandates including privatization, public spending cuts, and deregulation have eroded social services and livelihoods across the region, propelling economic desperation and migration. Once trapped in Libyan detention centers, captured migrants endure forced labor in sectors like construction and agriculture, generating profits for militias and transnational firms (Al-Dayel et al., 2021). This system mirrors Marx’s concept of a reserve army of labor, wherein austerity and ecological breakdown render marginalized populations hyper-exploitable, reducing them to disposable commodities within global capitalist supply chains.

Racial Capitalism: The stark disparity in enslavement rates between sub-Saharan African migrants and their Arab or Asian counterparts in Libya reflects entrenched racial hierarchies rooted in anti-Blackness and colonial legacies. Sub-Saharan Africans are disproportionately targeted due to systemic dehumanization that frames Black lives as disposable commodities within Libya’s trafficking networks. Historical and ongoing racism, compounded by their frequent lack of diplomatic protections or transnational kinship networks, renders them hyper visible to exploitation. By contrast, Arab and Asian migrants often benefit from perceived ethnic or geopolitical affiliations (e.g., shared linguistic, religious, or regional ties to North African or Middle Eastern actors) that afford them marginal bargaining power or protection from militias. For instance, Asian migrants may leverage home-country embassies to negotiate release, while Arab migrants are less frequently racialized as “outsiders” in the Maghreb context (IOM, 2023).

This racialized hierarchy is actively weaponized by EU border externalization policies, which outsource migration enforcement to Libyan militias while ignoring their predatory practices. European corporations like ENI further entrench this system by partnering with local actors in militia-controlled oil fields, effectively subsidizing human trafficking economies (Tjønn and Lemberg, 2022). Profits from resource extraction flow to the Global North, while sub-Saharan Africans stripped of autonomy by racial capitalism are funneled into forced labor to sustain this cycle of exploitation. Thus, Libya’s trafficking economy is not merely a humanitarian crisis but a structural feature of a global order that monetizes anti-Blackness.

The failure of international institutions

The international community’s response to Libya’s slave trade has been marred by systemic failures that reveal a troubling gap between rhetoric and action. The European Union, while positioning itself as a defender of human rights, has prioritized border containment over the dignity of migrants. Through its migration management framework, the EU has allocated millions of Euros to Libya, ostensibly to curb Mediterranean crossings (Michael et al., 2019). In practice, these funds have equipped the Libyan Coast Guard with vessels and training to intercept migrants. Behind this policy lies a darker reality: Frontex, the EU’s border agency, shares surveillance data with Libyan militias, enabling interceptions that directly feed trafficking networks. Frontex drones and patrol aircraft relay migrant boat coordinates to Libyan authorities, knowing detainees face torture, forced labor, and extortion (Forensic Oceanography, 2023). Corporate contractors like Italy’s Aeneas compound this exploitation, profiting from EU-funded detention infrastructure projects in Zawiya and Tripoli, where migrants are forced to build facilities for their imprisonment. While the EU claims its policies “save lives,” the Mediterranean’s death toll tells a different story. The IOM (2023) reports that fatalities per crossing have surged from 1 in 38 in 2017 to 1 in 23 by 2023 as riskier routes emerge to evade interception. This grim calculus underscores how outsourcing migration control to abusive actors has normalized death and despair as collateral damage in the EU’s border regime.

Meanwhile, the United Nations, tasked with upholding global human rights, has compromised its moral authority through pragmatic alliances with perpetrators. The UN Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) meticulously documents atrocities in detention centers yet relies on armed groups like the Stability Support Apparatus, a militia implicated in trafficking for access and security during field visits. This quid pro quo legitimizes warlords as de facto state actors, undermining efforts to hold them accountable. Since 2011, the UN Security Council has sanctioned at least 34 individuals under its Libya sanctions regime (resolutions 1970 and subsequent), primarily targeting destabilizing activities such as arms embargo violations, illicit oil exports, and support for armed groups (Security Council Committee, 2018). Of these, six individuals were explicitly designated for their roles in human trafficking and migrant smuggling networks in 2018, a landmark move as the first UN sanctions targeting traffickers globally. These included figures like Ermias Ghermay, Fitiwi Abdelrazak, and Abd al-Rahman al-Milad, who commanded militias and coastguard units implicated in systematic exploitation (Haenlein and Kadlec, 2018). The Security Council’s paralysis, driven by veto-wielding states like Russia and the US, both suppliers of arms to Libyan factions, ensures impunity for smuggling routes in Southern Libya, while enjoying diplomatic cover in New York. The UN’s 2018 Global Compact on Migration, a non-binding pledge to protect migrants, epitomizes this institutional timidity, offering aspirational guidelines while sidestepping enforceable measures.

Similarly, the African Union (AU), despite its vocal condemnations of trafficking, has failed to translate ambition into meaningful action. This inertia stems from limited resources and political hesitance to confront the root causes of displacement. The AU remains conspicuously silent on EU extractive policies in the Sahel, were land grabs and cooperates resource exploitation- often backed by European development funds- have displaces millions. In Niger, French uranium mines projects have drained groundwater and appropriated farmlands, pushing communities into migration (Larsen and Mamosso, 2013). Yet the AU’s 2018 Migration Policy Framework avoids critiquing these neo-colonial dynamics, instead framing migration as a security challenge to be managed, not a consequence of global inequality (African Union, 2018). This reluctance mirrors the AU’s broader alignment with donor interests, sacrificing migrant lives at the altar of diplomatic convenience.

Together, these institutional failures reveal a pattern of complicity. The EU outsources violence to Libya while corporations’ profit from detention infrastructure; the UN trades access for legitimacy, sanitizing warlords as stakeholders; the AU overlooks extraction-driven displacement to maintain partnerships with former colonial powers. This triad of hypocrisy sustains Libya’s trafficking economy, where human lives are reduced to commodities in a global system that privileges borders over people. Until these institutions reckon with their roles in perpetuating exploitation divesting from militarization, enforcing accountability, and centering the dignity of the displaced their interventions will remain not just ineffective but actively harmful (Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), 2023).

Recommendations

To dismantle Libya’s trafficking economy, the international community must confront its complicity and reorient policies toward equity and accountability:

End EU funding to Libyan militias

Action

Redirect the €455 million border budget to climate resilience programs in the Sahel, addressing droughts and food insecurity that displace millions.

Accountability

While the European Union’s Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime (GHRSR) is primarily intended to target non-EU, actors implicated in grave human rights violations, EU member states possess more direct and legally robust mechanisms to hold their own citizens and corporations accountable for abuses. For example, allegations against EU-based firms such as Aeneas and ENI both accused of benefiting from forced labor and militia collaborations in Libya, could be addressed through existing frameworks that bypass the GHRSR’s jurisdictional constraints.

The EU Anti-Trafficking Directive (2011/36) provides a transnational legal basis for penalizing corporate complicity in forced labor, while public procurement bans (European Union, 2011), like those enacted by Germany in 2023, exclude companies tied to militia contracts from state-funded projects. More recently, the 2024 Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) has introduced binding obligations for EU firms to identify and mitigate human rights risks within their global supply chains (European Union, 2023), however, enforcement remains inconsistent and politically contingent.

Prosecute high-level perpetrators

ICC

Prioritize cases against militia leaders (e.g., Stability Support Apparatus commanders) and foreign enablers. ICC has intensified its efforts to address systematic crimes in Libya, including enslavement, torture, and sexual violence against migrants, perpetrated by militia leaders and foreign enablers operating with state support. In May 2025, Libya formally granted the ICC jurisdiction over crimes committed on its territory from 2011 to 2027 under Article 12(3) of the Rome Statute, signaling a commitment to accountability and cooperation with the Court (LCW, 2025). ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan highlighted this as a profound step toward justice, particularly for victims in detention facilities such as Mitiga Prison in Tripoli, where crimes against humanity and war crimes were documented (United Nations, 2025).

A pivotal case involves Osama Elmasry Njeem, a Libyan police officer accused of overseeing atrocities at Mitiga Prison. Despite his arrest in Italy under an ICC warrant, Italy controversially returned him to Libya, undermining the Court’s investigation and sparking criticism over state cooperation obligations under the Rome Statute. This decision drew condemnation from human rights groups, who argued it perpetuated impunity and violated Italy’s duty to surrender suspects to the ICC (Meloni, 2025).

The ICC’s jurisdiction in Libya, initially triggered by a 2011 UN Security Council referral (Resolution 1970), has faced challenges, including political interference and debates over complementarity. While Libya’s recent declaration under Article 12(3) strengthens the legal basis for ICC action, critics question the efficacy of national prosecutions given the country’s instability and alleged collusion between authorities and militias (United Nations, 2025). The Court’s evidence includes survivor testimonies, forensic data, satellite imagery, and verified video footage, underscoring the systematic nature of crimes against migrants (United Nations, 2025). Efforts to prioritize accountability for high-level perpetrators, such as Stability Support Apparatus commanders, align with the ICC’s mandate to deter atrocities and uphold restorative justice. However, enforcement remains fraught, as seen in the Elmasry case, where geopolitical interests, such as Italy’s reliance on Libya to curb migration, overshadowed legal obligations (Meloni, 2025).

UN

The UN Security Council’s Libya sanctions regime, established in 2011 to curb arms trafficking and stabilize the country, has been rendered ineffective by geopolitical divisions and structural flaws. Permanent members’ veto power has enabled selective enforcement: resolutions disproportionately target maritime routes while ignoring aerial arms transfers by states like the UAE and Russia to Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA), and Turkey’s exploitation of legal loopholes to rebrand military support to the Government of National Accord (GNA) as bilateral cooperation. Despite documented violations— including UAE-supplied drones, Russian Wagner mercenaries, and Turkish-deployed Syrian fighters— no state has faced sanctions due to political shielding. Weak enforcement persists, with violators like Jordan and Egypt acting with impunity, and EU states like France undermining sanctions through arms sales to UAE and Egypt. To bypass UNSC vetoes and hold violators accountable, reforms could decentralize enforcement via regional coalitions (e.g., AU oversight of Operation IRINI) and leverage UN General Assembly resolutions to authorize measures against embargo-breakers like UAE and Turkey. Closing legal gaps—expanding sanctions to aerial routes, sanctioning banks facilitating arms deals, and mandating universal jurisdiction for prosecutions would curb state-sponsored trafficking. Conditioning EU aid on compliance and suspending arms exports to violators could further pressure complicit actors. Without structural overhauls to overcome veto paralysis, Libya’s cycle of impunity and instability will endure.

Fair migration pathways

EU

Expand legal migration quotas for sub-Saharan Africans, reducing reliance on dangerous routes.

Regional cooperation

Establish AU-managed asylum centers in Niger and Chad, offering protection without detention.

Conclusion

Libya’s slave trade is a mirror reflecting the global order’s moral and humanitarian decay. As Marxist analysis reveals, this crisis is sustained by capitalist exploitation, imperialist interventions, and racialized violence. The EU’s border policies, UN complicity, and corporate greed are not anomalies but features of a system that monetizes human suffering. Meaningful change demands more than humanitarian gestures; it requires dismantling the architectures of exploitation. Redirecting resources to Sahelian climate resilience, prosecuting perpetrators, and empowering local governance offer tangible pathways to justice. As Libyan activist Hameda al-Magariaf starkly reminds us: “The world’s hands are not tied they are profitably bloodied.” We can only transform Libya from a symbol of failure into a testament of collective moral courage by confronting this hypocrisy.

Author contributions

FL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ACLED (Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project). (2024). Annual Report on Global Political Violence. Brooklyn, NY: ACLED.

African Union. (2018). Au MPFA executive summary. Addis Ababa: African Union. Available at: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/35956-doc-au-mpfa-executive-summary-eng.pdf (Accessed May 15, 2025).

Al-Dayel, N., Anfinson, A., and Anfinson, G. (2021). Captivity, migration, and power in Libya. J. Hum. Traffick. 9, 280–298. doi: 10.1080/23322705.2021.1908032

Amin, S. (1976). Unequal development: An essay on the social formations of peripheral capitalism. New York, USA: Monthly Review Press.

Amnesty International. (2022). Libya: “I wished I would die”: Survivors’ accounts of rape and sexual violence in Libyan detention centers. London: Amnesty International. Available online at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde19/5678/2022/en/ (Accessed January 28, 2025).

Andersson, R. (2014). Illegality, inc.: Clandestine migration and the business of bordering Europe. Oakland, California, USA: University of California Press.

BBC News. (2017). Libya migrant “slave market” footage sparks outrage. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/worldafrica-42038451 (Accessed February 26, 2025).

CNN. (2017). Account onboarding. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/account/onboarding/sso (Accessed February 26, 2025).

CNN. (2022). “Libya’s Migrant Detention Centers: A Crisis Ignored.” CNN International, [Month Day]. Atlanta, GA: Cable News Network, Warner Bros. Discovery

Crisis Group. (2024). Crisis watch database. Available at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/crisiswatch/database?location[]=95 (Accessed February 26, 2025).

De Leo, A. (2024). The court of Crotone on the Libyan coast guard: interception and returns to Libya are not rescue operations. Will it be enough to stop EU funding? REALaw.Blog, 27 September. Available online at: https://realaw.blog/2024/09/27/the-court-of-crotone-on-the-libyan-coast-guard-interception-and-returns-to-libya-are-not-rescue-operations-will-it-be-enough-to-stop-eu-funding-by-andreina-de-leo/ (Accessed May 15, 2024).

Didier, C., Diouf, F., and Lee, J. (2022). The return of slavery in Libya. Grow Think Tank. Available at: https://www.growthinktank.org/en/the-return-of-slavery-in-libya/ (Accessed February 26, 2025).

European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), and Lawyers for Justice in Libya (LFJL) (2021). No way out: Migrants and refugees trapped in Libya face crimes against humanity. European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights. Available at: https://www.ecchr.eu/en/publication/no-way-out-migrants-and-refugees-trapped-in-libya-face-crimes-against-humanity/ (Accessed May 15, 2025).

European Union (2011). Directive 2011/36/EU on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:02011L0036-20240714 (Accessed October 15, 2023).

European Union (2023). Corporate sustainability due diligence directive (CSDDD). Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52022PC0071 (Accessed February 26, 2025).

Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). (2023). EITI standard. Oslo: EITI. Available at: https://eiti.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/2023%20EITI%20Standard.pdf (accessed February 26, 2025).

Federici, S. (2004). Caliban and the witch: women, the body, and primitive accumulation. Brooklyn, New York, USA: Autonomedia.

Forensic Oceanography (2023). Death by rescue: The EU’S complicity in migrant abuse. Geneva: Forensic Oceanography. Available at: https://content.forensic-architecture.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/2016_Report_Death-By-Rescue.pdf (Accessed February 26, 2025).

Geray, L. A. (2024). Fortress Europe: analysing the human rights impact of EU border externalisation in third countries since 2015. Cape Town, South Africa: Doctoral Dissertation. University of Cape Town.

Global Financial Integrity (2021). Illicit financial flows and human trafficking in Libya: The trafficking economy and global capitalism. Washington, D.C.: Global Financial Integrity. Available at: https://www.gfintegrity.org/report/libya-trafficking-economy-2021/ (Accessed May 15, 2024).

Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. (2021). The human trafficking–terrorism nexus in the Sahel: a study of migrant routes and trafficking dynamics. Geneva: Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. Available at: https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/human-trafficking-smuggling-nexus-in-libya/ (Accessed May 15, 2024).

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Edited and translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International Publishers.

Haenlein, C., and Kadlec, A. An unprecedented failure? UN sanctions against human traffickers in Libya. London: Royal United Services Institute. (2018). Available at: https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/unprecedented-failure-un-sanctions-against-human-traffickers-libya (Accessed May 15, 2024).

HRW (Human Rights Watch). (2017). Libya’s Dark Web of Collusion: Abuses Against Europe-Bound Migrants and Refugees. New York: Human Rights Watch.

HRW. (2023). “We Are Detained in Hell”: EU Policies in Libya. New York: HRW. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/01/21/no-escape-hell/eu-policies-contribute-abuse-migrants-libya (Accessed February 26, 2025).

Ilesanmi, O. O., and Iyer-Raniga, U. (2024). 21st century slavery: The various forms of human enslavement in today's world. London, UK: IntechOpen.

IOM. (2023). Libya migration trends report. Geneva: IOM. Available at: https://dtm.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/DTM_Libya_R46_Migrant_Report_23-May-2023.pdf (Accessed February 26, 2025).

IOM (International Organization for Migration). (2023a). World Migration Report 2024. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

IOM (International Organization for Migration). (2023b). Libya: Migrant Vulnerability Assessment. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Kadri, A. (2020). “The Marxian perspective” in A theory of forced labour migration: the proletarianization of the West Bank under occupation (1967–1992), London: Palgrave Macmillan. 155–190.

Karasapan, O., and Sajjad, S. (2018). The slave trade in Libya: What can development actors do? Brookings. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-slave-trade-in-libya-what-can-development-actors-do/ (Accessed February 26, 2025).

Larsen, R. K., and Mamosso, C. A. (2013). Environmental governance of Uranium in Niger: a blind spot for development cooperation? (No. 2013: 02). Copenhagen, Denmark: DIIS Working Paper.

LCW. (2025). “STATEMENT: LIBYA ACCEPTS ICC JURISDICTION AMID POLITICAL DIVISION AND ENTRENCHED IMPUNITY – Libya Crimes Watch.” Libya Crimes Watch. Available at: https://lcw.ngo/en/blog/statement-libya-accepts-icc-jurisdiction-amid-political-division-and-entrenched-impunity/ (Accessed May 23, 2025).

Lewis, A., Amulega, S., and Langmia, K. (2021). ““Arab spring” or Arab winter: social media and the 21st- century slave trade in Libya” in Routledge handbook of African media and communication studies. eds. Mano, W. and milton, v. c. (Abingdon, UK and New York, USA: Routledge), 181–191.

Meloni, C. (2025). Italy, Libya, and the failure of state cooperation with the International Criminal Court in the Elmasry arrest case. Available at: https://www.justsecurity.org/107175/italy-libya-icc-cooperation-elmasry-arrest/ (Accessed May 19, 2025).

Michael, M., Hinnant, L., and Brito, R. (2019). Making misery pay: Libya militias take EU funds for migrants. Pulitzer Center. Available at: https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/making-misery-pay-libya-militias-take-eu-funds-migrants (Accessed May 15, 2025).

Murphy, L. (2019). The new slave narrative: The battle over representations of contemporary slavery. New York, USA: Columbia University Press.

Onitiri, A. (2023). Libyan conflict and identerism: A theoretical approach to understanding unstable political violence (doctoral dissertation). New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA: Rutgers University.

OHCHR (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights). (2021). Report on Human Rights Violations Against Migrants in Libya. Geneva: United Nations.

Palumbo, L. (2024). “Slavery, forced labour, and trafficking” in Taking vulnerabilities to labour exploitation seriously. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 1–30.

Robinson, C. J. (1983). Black marxism: The making of the black radical tradition. Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA: University of North Carolina Press.

Security Council Committee Concerning Libya Adds Six Individuals to its Sanctions List | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. (2018). Available at: https://press.un.org/en/2018/sc13371.doc.htm.

Selján, P. (2020). Military intervention and changing balance of power in Libya. Acad. Appl. Res. Mil. Public Manag. Sci. 19, 71–84. doi: 10.32565/aarms.2020.3.5

Smith, J. (2024). Wagner’s shadow networks: proxy militias and resource exploitation in North Africa. J. Transnatl. Secur. 12, 45–67.

Sunderland, J. (2023). No escape from hell. Human Rights Watch. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/01/21/no-c-libya (Accessed February 26, 2025).

Tjønn, M. H., and Lemberg, M. (2022). “Geopolitics of energy and migration control in Libya” in Postcoloniality and forced migration. eds. Janmyr, M and Nordblad, J. Bristol: Bristol University Press. 125. Available at: https://bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/postcoloniality-and-forced-migration.

UN Panel of Experts. (2023). Final report on Libya. New York: United Nations. Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/4022306 (Accessed February 26, 2025).

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). (2023). Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2022. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

UNSC (United Nations Security Council). (2023). Final Report of the Panel of Experts on Libya (S/2023/88). New York: United Nations.

United Nations (2025). As criminal court prosecutor accelerates work, Libya Must Be Prepared to Carry Out Credible, Effective Proceedings at National Level, Delegate Tells Security Council. Available at: https://press.un.org/en/2025/sc16062.doc.htm (Accessed May 19, 2025).

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (2022). Global report on trafficking in persons 2022. Vienna: UNODC, p. 67. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/2022/GLOTiP_2022_web.pdf (Accessed January 28, 2025).

United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) and Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). (2021). Desert dawn: Human trafficking and modern slavery in Libya. Geneva: OHCHR, pp. 14–16. Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/LY/DesertDawnReport.pdf (Accessed February 3, 2025).

Wallerstein, I. (1974). The modern world-system I: Capitalist agriculture and the origins of the European world-economy in the sixteenth century. (New York, USA and London, UK: Academic Press).

World Bank. (2023). Libya economic monitor, spring 2023: Strengthening resilience in a fragile environment. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/baaff799-31fe-400d-8c0f-8934d997faf3 (Accessed May 15, 2024).

Keywords: slave trade, human trafficking, Libya, migration policies, political instability

Citation: Lahai FJ (2025) The new slave trade in Libya: evaluating the modern humanitarian crisis (2015–2024). Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1536457. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1536457

Edited by:

Paolo De Stefani, University of Padua, ItalyReviewed by:

Uwomano Benjamin Okpevra, Delta State University, Abraka, NigeriaCopyright © 2025 Lahai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Festus Jusu Lahai, ZmVzdHVzbGFoYWlAbWFpbC5jb20=

Festus Jusu Lahai

Festus Jusu Lahai