- Department of Audiovisual Communication and Advertising, Faculty of Communication Sciences, University of Malaga, Málaga, Spain

Digital technologies have made it easier for lobbies to reach a larger audience, generate support, and collect data to bolster their campaigns. At the same time, digital tools have contributed to increasing participation in lobbying activities, as information is more readily accessible to the public. Policymakers are also leveraging digital technologies to engage with a broader range of stakeholders, gather input on policy issues, and enhance transparency in the policymaking process. Lobbies, or interest groups, use digital tools and platforms to interact with policymakers, communicate their interests, and influence decision-making. However, there are concerns about the influence of big tech companies and the potential for digital lobbying to distort public policy outcomes. Overall, the digital age has reshaped the dynamics between lobbies and public policies, presenting both opportunities and challenges for achieving transparent and accountable governance. Currently, the EU lacks an evaluation or regulatory service to scrutinize digital lobbying strategies. In this digital age, the relationship between lobbyists and public policies has changed significantly, with technology playing a critical role. Although the EU Transparency Register attempts to improve transparency and accountability in interactions between interest groups and EU institutions, further development is needed in examining the digital discourse strategies of interest groups. The purpose of this study is to examine the digital strategies of lobbies in the EU through web mining, social media tracking, and text mining techniques. Content analysis will be conducted to identify and describe the digital strategies that EU lobbyists employ: online media, social media, online formats, and publications to advocate for and influence public policies. The results will reveal the strategies of lobby influence in digital environments and the scope and scale of the digital discourse created by these activities. This will provide deeper insights into the impact of these organizations on public policies in the EU across various sectors in terms of digital communication and the online factors influencing the policymaking process with engaged stakeholders. Finally, the methodology serves as a proposal for an analytical framework for monitoring the development of political communication by these entities with their stakeholders in the digital ecosystem and the resulting digital discourse.

1 Introduction

The present study examines digital communication strategies of lobbying in the European Union using advanced research methods of social media analysis in a two-fold manner. On one hand, it investigates the development of political communication related to lobbying in the EU within the digital ecosystem; on the other, it analyzes the discourse on lobbying in the EU generated by this communication activity in online media, with a particular focus on social media and its content.

The communication of lobbying, especially from a PR perspective, in the European Union (EU) has been sufficiently described in the academic literature (Haug and Koppang, 1997; Castillo-Esparcia, 2011). In the 21st century, lobbying strategies through digital media have evolved significantly, reflecting broader trends in political advocacy and public engagement (Anduiza et al., 2009). However, while social media can enhance visibility and public engagement, it is important to note that direct lobbying strategies (Chalmers and Shotton, 2016) and media presence (Moreno Cabanillas et al., 2024) remain crucial for effective advocacy within EU institutions. This multifaceted approach—leveraging both digital and traditional lobbying methods—reflects the complex landscape of EU lobbying (Bernhagen, 2014; Baumgartner, 2007; Andersen and Eliassen, 1991), where various strategies of advocacy and influence (Almiron and Xifra, 2016) are employed based on the context and objectives of the interest groups involved.

The integration of social media into lobbying strategies has transformed the landscape of interest group communication and political communication in general (Almansa Martínez et al., 2022), allowing for more dynamic interactions between lobbyists, policymakers, and the public.

This transformation cannot be reduced to a mere shift in medium but represents a fundamental change in how advocacy is conducted and perceived within the EU context and computer-mediated communication framework (Carty, 2010). Interest organizations increasingly leverage social media platforms (Casero-Ripollés, 2015) to shape public discourse and mobilize support for their causes through CMC/DMC (computer-mediated communication/digitally mediated communication)-driven discourse across digital media. Thus, social media has become a tool and platform to help “produce” society through widespread social movements (Pleyers and Álvarez-Benavides, 2019) that generate a variety of limitless debates on key, divergent issues.

However, the effectiveness of social media in achieving tangible policy outcomes remains a subject of debate, as the nuances of EU policymaking (Bocse, 2013) often favor more direct forms of lobbying (Chalmers and Shotton, 2016). Moreover, the role of media in the lobbying process cannot be understated (Castillo Esparcia et al., 2017). Social media has become a platform with almost infinite capacity (Fuchs, 2014) to enhance the presence, message, and influence of interest groups, given its transnational and immediate effects as well as the fluid and open nature of communication across multiple digital media platforms. As such, it can become a powerful tool for political marketing (Harris and McGrath, 2012).

Hanegraaff and Berkhout (2018), who emphasize that the presence of organized interests in media discussions correlates with their lobbying success, further support this trend. They suggest that visibility in public discourse can translate into political influence. The dynamics of lobbying in the EU are also shaped by the nature of the actors involved. Business associations often dominate the lobbying landscape, reflecting a broader trend where economic interests are prioritized over other types of advocacy (Poletti and De Bièvre, 2014).

As foreign lobbying laws gain traction, the EU’s approach to regulating lobbying activities is evolving, necessitating a more strategic and transparent communication framework for lobbyists operating within its institutions. Furthermore, the impact of digital media on lobbying is evident in the way civic organizations, particularly those representing marginalized groups, utilize online platforms to amplify their voices.

While the rise of digital media has opened new avenues for lobbying, and social media presents new tactics (Chalmers and Shotton, 2016), offering opportunities for grassroots mobilization and public engagement, it has also introduced challenges related to information overload and the quality of discourse via CMC/DMC techniques.

Furthermore, this transformation reflects a broader trend in advocacy where traditional lobbying methods are supplemented or replaced by digital tactics, allowing for more direct engagement with both policymakers and the public (Micó and Casero-Ripollés, 2014; Smolak Lozano et al., 2018). These changes necessitate an examination of the lobbying image in contemporary times (Xifra and Collell, 2015), as mass media and social media together can impact political perceptions and preferences (Kleinnijenhuis et al., 2019). The interplay between public opinion and lobbying success is another critical aspect of communication models in EU lobbying. Research suggests that interest groups aligning their messages with prevailing public sentiments are more likely to achieve their advocacy goals (De Bruycker and Colli, 2023). This alignment is particularly relevant in a politicized environment, where public perception can significantly influence policy decisions. Consequently, interest groups are increasingly tasked with not only crafting compelling messages but also ensuring that these messages resonate with the broader public discourse (Rasmussen et al., 2018).

Nevertheless, the proliferation of information online can lead to confusion and misinformation, complicating interest groups’ efforts to communicate their messages effectively. The intersection of lobbying and digital media also raises questions about the ethical implications of online advocacy and issues related to balanced representation and discourse creation, which are influenced by the resources of the interest groups (van der Graaf et al., 2016).

This dual approach, using traditional and digital media, allows organizations to influence decision-makers directly while also engaging the public in advocacy efforts, thereby amplifying their message and increasing visibility and influence within the EU legislative framework (De Bruycker and Beyers, 2015). This is achieved by utilizing media strategies to frame public debates, which underscores the importance of media relations in contemporary lobbying practices. Beyers and De Bruycker (2017) argue that this creates a skewed representation of interests within the EU policymaking process, where business voices are amplified at the expense of non-business interests. This imbalance raises critical questions about the inclusivity of the EU’s democratic processes and the extent to which diverse voices can be heard in the digital arena. Gorostiza-Cerviño et al. (2023) concluded that the lobbies affiliated with the European Transparency Register employ digital media extensively: 98% have websites and 68% use social media platforms. van der Graaf et al. (2016) examined the range and volume of social media use by interest groups in the EU, focusing on content creation and global interaction in the cyber public sphere. Their findings did not confirm the democratic and empowering role of social media in combating the unequal representation of interests in democratic processes, highlighting the dominance of strong lobbies that use a wide range of social media platforms, with Facebook and Twitter being the most powerful tools. Similarly, the use of digital media allows interest groups to align their positions with policymakers through open consultations, which can shape lobbying strategies based on the perceived preferences of decision-makers (Bunea, 2014). Moreover, the dynamics of lobbying in the EU are influenced by the salience of issues and the complexity of the legislative environment. Research indicates that the success of lobbying efforts is often contingent upon the ability of interest groups to effectively communicate their positions and align them with the interests of the European Commission and other EU institutions (Bernhagen, 2014; Boräng and Naurin, 2015).

In addition to lobbying strategies, the emergence of anticipatory narratives and storylines has become a critical component of lobbying efforts due to their resonating power with both policymakers and the public, thereby influencing the framing of policy issues (Minkkinen, 2018). This narrative-driven approach is particularly relevant in the context of digital media, where storytelling can serve as a powerful tool for engagement and persuasion, transforming lobbying campaigns through a digital grassroots movement that employs storytelling to influence governments in EU countries (Figenschou and Thorbjørnsrud, 2020). Vathi and Trandafoiu (2023) explore how organizations have used social media to mobilize EU citizens in the UK post-Brexit, highlighting the effectiveness of digital communication in grassroots advocacy. One prominent model of communication in this context is the use of social media as a tool for advocacy and mobilization. Research indicates that social media platforms enable interest groups to engage in “networked advocacy,” which enhances awareness-raising and community-building efforts (Beyers et al., 2015). This model allows for the efficient and targeted dissemination of information and mobilization of support. For instance, the study by Figenschou and Fredheim highlights how social media affordances facilitate the organization of campaigns that can quickly reach a broad audience, thereby amplifying the voices of interest groups (Figenschou and Fredheim, 2020).

The ability to shape narratives online allows interest groups to proactively address potential opposition and mobilize support more effectively. Figenschou and Fredheim (2020, p.2) examine the social media use by interest groups as a model for networked advocacy: “Theoretically, it combines insights from networked media logics, social affordances, and interest group advocacy to conceptualize how networked media can afford a new form of lobbying conducted as real-time, semi-private direct communication with decision makers.”

Moreover, the emotional and personal storytelling aspects of social media campaigns can resonate more deeply with the public, fostering a sense of community and shared purpose (Figenschou and Thorbjørnsrud, 2020).

Altogether, both digital advocacy and narratives create a CMC/DMC discourse that enables connection and collaboration among collectives from diverse backgrounds. In this way, online platforms not only facilitate the exchange of information and ideas but also enable social and political activism, empowering marginalized groups to advocate for change.

The above-mentioned cases illustrate the potential of digital media to democratize lobbying efforts, allowing for broader participation and engagement in the policymaking process. The interplay between globalization and social media is crucial for lobbying strategies, according to the international perspective study by Brown (2016). Furthermore, the effectiveness of digital lobbying strategies can vary significantly based on the resources available to interest groups. Larger organizations with greater financial and technical capabilities are often more adept at utilizing social media for lobbying purposes, as seen in the case of tech companies (Popiel, 2018), while smaller groups may struggle to achieve similar levels of impact (Figenschou and Fredheim, 2020). This disparity raises questions about equity in advocacy, as resource-rich organizations can dominate the digital space, potentially sidelining less affluent voices (Brown, 2016; Klüver, 2012). Understanding the entire lobbying process, from mobilization to influence, highlights the role of digital media in facilitating these interactions (Hanegraaff and Berkhout, 2018; Beyers et al., 2014).

The digital landscape also presents challenges for transparency and accountability in lobbying activities. Leveraging both digital and traditional lobbying methods reflects the complex nature of EU lobbying, where different strategies are employed based on the context and objectives of the interest groups involved. As interest groups increasingly rely on digital platforms to influence public opinion and policymaking, the potential for manipulation and disinformation becomes a pressing concern. The EU’s lobbying transparency register, as discussed by Dinan (2021), aims to address these issues by promoting accountability and openness in lobbying practices. However, the effectiveness of such measures in curbing unethical practices remains uncertain, necessitating ongoing scrutiny and reform. The lack of formal regulation and transparency around lobbying practices in the EU has raised concerns about the potential for undue influence by powerful interest groups (Svendsen, 2011; Korkea-aho, 2022). The regulatory environment surrounding lobbying in the EU also plays a significant role in shaping communication strategies (Chari and O'Donovan, 2011). Korkea-aho (2023) notes that the increasing scrutiny of lobbying activities, particularly regarding transparency and accountability, has prompted interest groups to adapt their strategies. In the EU context, the Register of Interest Representatives serves as a formal mechanism to enhance the engagement of lobby groups and civil society in the policymaking process (Gorostiza-Cerviño et al., 2023). This initiative emphasizes the importance of transparency and inclusivity in lobbying efforts, as it provides a platform for various stakeholders to present their views and influence policy outcomes.

As early, Feenstra and Casero-Ripollés (2014) proposed a political monitoring process for democracy developing in a digital environment. Additionally, the modern PR practice of “grassroots lobbying” poses legal implications for further regulation of the communication activities of lobbyists (Myers, 2018). Chalmers (2013) emphasizes the importance of providing policymakers with relevant and high-quality information to facilitate informed decision-making, suggesting that the quality of communication is as crucial as the medium used. This underscores the need for interest groups to develop sophisticated communication strategies that prioritize clarity and relevance in their messaging.

Taking into account the aforementioned considerations, the study implements social media listening (Rikkonen and Isotalus, 2024; Erkkilä and Luoma-aho, 2023; Fontenla-Pedreira et al., 2023). Additionally, it applies CMC/DMC discourse tracking (López Delacruz and Martínez Núñez, 2023; Jucker, 2021; Durán Vilches et al., 2023) to scrutinize lobbying communication in the EU’s digital environments and reflect the state of public debate. As such, the study attempts to design and implement an analytical framework aimed at analyzing lobbying political communication on social media and the resulting online debates. It takes into account various elements specific to this type of digitally mediated communication process, such as textual data, large data sets, public interactions, community engagement, generated sentiment, user-generated content (UGC), narratives around key topics, active platforms, influencers, and geographical or time constraints.

Thus, the present study can be positioned within the emerging and continually evolving research landscape that incorporates diverse methods and techniques to explore the richness of online media data. Among these are automated tracking and/or computational linguistics in the study of opinion and discourse in communication networks in online media, as well as the use of textual data to determine policy positions (Laver et al., 2003; Schuld et al., 2023; Banisch et al., 2010; Christner et al., 2022). Studies of social media, like the present one, while searching for new models and attempting to move beyond commercial solutions, face challenges, as noted by de Vreese and Neijens (2016), regarding the measurement of media exposure in a changing communication environment and the implications of big data for academics (Bruns, 2013). These challenges include automated data collection on the web (Jünger, 2018) and the requirements of natural language processing (Goldberg, 2017), given the wide range of methods and data sources available in public opinion research on online communication (González-Bailón and Paltoglou, 2015). The ambition of the study is to contribute to computational communication studies by integrating big data into the communication field (Hilbert et al., 2019; Margolin, 2019).

2 Materials and methods

Internet audience studies (Coffey, 2001), online opinion studies (Liu et al., 2005), and opinion mining (Pang and Lee, 2008) inform the applicable approach.

It employs a wide range of contemporary methodological perspectives in online communication research, including the Big Data approach (Wieland et al., 2018); web data mining (Liu, 2008); live social research (Marres and Weltevrede, 2013); digital trace data (Stier et al., 2020); sentiment analysis in political communication textual data in conjunction with computational linguistics (van Atteveldt et al., 2021; Benoit et al., 2016; Cho, 2013; Haselmayer and Jenny, 2017); and, finally, automated tools for content analysis and political textual data (Boumans and Trilling, 2016; Grimmer and Stewart, 2013; Krippendorff, 2012; Hopkins and King, 2010).

As such, it involves observing and collecting data in the digital world through automated tracking, web mining, and text mining of large datasets in social media to comprehend interactions and meanings in online spaces. It enables the collection of various types of data, such as text-based chats, photographs, videos, and other digital messages generated by users in online media. Because of the data richness and broad access to multiple online communities, it is possible to uncover real-time patterns, themes, and underlying meanings in interactions occurring across various digital platforms.

The object of the study is the digital lobbying strategies in EU and CMC/DMC discourse created by them, combining both quantitative and qualitative approaches, as this proves productive, according to Ilbury (2024). It employs a range of methodologies, including content analysis, social media listening, and semantic analysis through computational linguistics with natural language processing (LDA models included in commercial software Brand24). This research strategy offers the most comprehensive investigation, allowing for a broader understanding of patterns and dynamics while also providing deeper insights into the dataset.

Social listening is a technique increasingly used in social science research. Using technologies like Brand24 requires systematic monitoring and analysis of online conversations, interactions, and published content for the searched keywords. It also enables the evaluation of public opinion (positive, negative, or neutral), identifying trends, determining participation (shares, likes, and comments), and tracking activities in the lobbying sector on social media. Monitoring tools use social media APIs or web scraping software to gather information from posts, comments, and other relevant content. It employs the following methods, as used in the present research: keyword monitoring to track mentions of specific keywords or phrases, sentiment analysis of social media conversations, topic modeling to identify the main topics discussed in social media conversations, and text mining to extract meaningful information from unstructured text data.

This method has been integrated with content analysis, which systematically investigates various types of communication in the complex environment of social media channels (Vitouladiti, 2014). This method enables researchers to detect and quantify the occurrence of specific words, themes, or concepts within a given textual data set, providing a structured mechanism for extracting relevant insights from the vast amounts of data that characterize social media research. We were able to identify the relevant social media platforms, the most pertinent keywords and hashtags, the most popular content formats (text, images, video), the sources (individual, organization, media), and the themes and topics of discussion using content analysis.

The area of content analysis has expanded from its initial concentration on quantitative analysis to include both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, allowing researchers to reveal both the manifest and latent content of communication, particularly when applied to online social discussions. As a result, natural language processing and computational linguistics have been combined using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) models, a statistical method used for classification and dimensionality reduction. On one side, it determines the features that best discriminate between distinct classes, while on the other, it projects high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving class separability, allowing for data categorization. The present study employed it to classify textual data (conversation topics, thematic pools in narratives, sentiment). Dimensionality reduction through feature selection (identifying the most important features that contribute to class separation) and visualization (reducing high-dimensional data) enables the extraction and description of complex textual data from nearly 60,000 mentions examined, as it aids in the effective handling of high-dimensional data and, due to its linear nature, facilitates the interpretation of the results.

The primary research question for this study is the following: “How do lobbies use social media to shape their public image, advocate for causes, and influence public discourse?” Subsequently, we divide this into two major research questions:

Q1: How do EU lobbyists shape their communication strategy in digital media, particularly social media?

Q2: What is the CMC/DMC discourse on EU lobbying like in terms of communication patterns, methods, and dynamics in digital media, particularly social media?

To determine the appropriate response, the main objective of the study is to examine the application of social media in shaping the DMC discourse related to lobbying communication practices, divided into the following specific objectives:

SO1: Determine advocacy and grassroots mobilization techniques based on the use of social media platforms to mobilize supporters and the use of UGC (strategies and techniques, including content type, channels of content promotion, live streaming, and paid content).

SO2: Identify the key elements and describe the mechanisms of opinion shaping and framing in social media conversations: narrative strategies used by lobbies to surround their issues to strategically disseminate information, frame debates, and pursue their interests in social media through highlighted issues and features, as well as identifying the hashtags and keywords that amplify the messages.

SO3: Describe the patterns of community building to establish the level of engagement and dialogue: interaction with public opinion, mechanisms and dynamics of collaboration with influencers and thought leaders to amplify the message and reach new audiences, as well as creating interactive experiences using social media features and encouraging audience participation (UGC).

For this purpose, the social media monitoring tool Brand24, a commercial software, monitored social media for 60 days during August and September of 2024 for the keywords “lobby,” “EU,” and “lobby in EU’ (including another version of the word “lobbying”), resulting in a total of 53,679 mentions. The gathered data (mentions) were further analyzed using content analysis and LDA techniques on sentiment, volume, and engagement metrics. As far as social media monitoring is concerned, a 60-day cycle is an industry standard as it provides measurable outcomes (e.g., follower growth, sentiment shifts) while remaining short enough to act on insights. A 60-day period of randomly chosen months across two different seasons constitutes a natural midpoint to assess organizational voice, content quality, and the overall effect of social media communication, which, in turn, helps build actionable insights. A 60-day window on the selected months of August and September captures emerging issues while the choice of these specific months helps avoid seasonal alignment and challenges or being solely tied to key events or cultural/seasonal patterns. This selection allows for a focus on baseline metrics while not emphasizing campaign-specific performance. The monitoring practice of social media is based on practical applications; thus, 60 days optimizes crisis prevention, issue management, content management in social media, and ROI measurement. For this reason, monitoring platforms automate sentiment tracking, competitor comparisons, and real-time alerts, enabling efficient analysis within 60-day windows. Randomly chosen months across two different seasons provide contextual layers to reports, distinguishing organic growth from event-driven anomalies.

The study embraces the main and most important social media channels: traditional social networks such as X (formerly called Twitter), Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, blogs, news media, forums, websites, and podcasts. TikTok falls into the video category due to the methods applied by the Brand24 tool. The variable values were calculated for overall data, including Facebook and Instagram, although the downloaded mentions exclude those from Meta platforms due to restrictions on Brand24 APIs for the Meta ecosystem, which might affect content and topic/theme analysis. Because the search keywords were in English, only mentions in English were analyzed, without geographical limitations, although the tool also provides mentions in other languages.

First, the data were extracted and downloaded to an Excel file with dates, links, titles, message content, and metatags to proceed with data coding and organization to categorize and classify the content. The coding scheme follows the process available in the Brand24 tool, containing categories such as content, themes, sentiments, language, sources, engagement, and geographical localizations. The quantitative analysis used statistical methods such as frequency counts, percentages, and averages. For qualitative analysis, thematic analysis was conducted to identify patterns and key themes in the textual data.

The research applied the following metrics:

1 Volume: the number of mentions.

2 Sentiment: the overall sentiment of the conversation, whether it is positive, negative, or neutral.

3 Reach: the number of people who have seen mentions regarding lobbying and policies.

4 Engagement: the number of likes, shares, comments, and other interactions with the detected mentions.

5 Share of Voice: the percentage of conversations about the topic.

6 Frequency of publications, reactions, keywords, and hashtags.

Below are the following key areas of measurement:

1 Public sentiment analysis and tracking sentiment shifts over time.

2 Public opinion: quantifying public sentiment towards specific topics.

3 Key topics and thematic axes in online social conversations surrounding lobbying and their pursued issues.

4 Key influencers that shape public opinion in online media, particularly social media.

5 Key trends: identifying emerging trends and topics that are gaining popularity.

6 Cultural shifts: analyzing how cultural shifts are reflected in social media conversations.

7 Social media activity: monitoring social media presence and identifying key strategies.

8 Potential threats: monitoring for negative sentiment towards issues that could impact the lobby’s discourse and narrative.

9 Monitoring public reaction: tracking public reactions to mentions, topics, issues and online conversations.

10 Audience needs: identifying public needs and preferences and gathering feedback.

By combining quantitative and qualitative approaches for a more comprehensive analysis, we gain insights into the thoughts, behaviors, and attitudes of audiences, as well as the ability to map the publication’s content and patterns. This allows for the analysis of large data sets from a wide range of social media channels in both qualitative and quantitative manners. The mixed methodology based on social media mining, big data, and automated tracking of live social data, including textual data and sentiment analysis, provides valuable opportunities to explore the rich context of social media discourse, which is extensive. Although it may seem complicated and difficult to grasp., the advanced methods of computational communication research facilitate its analysis and systematization.

3 Results

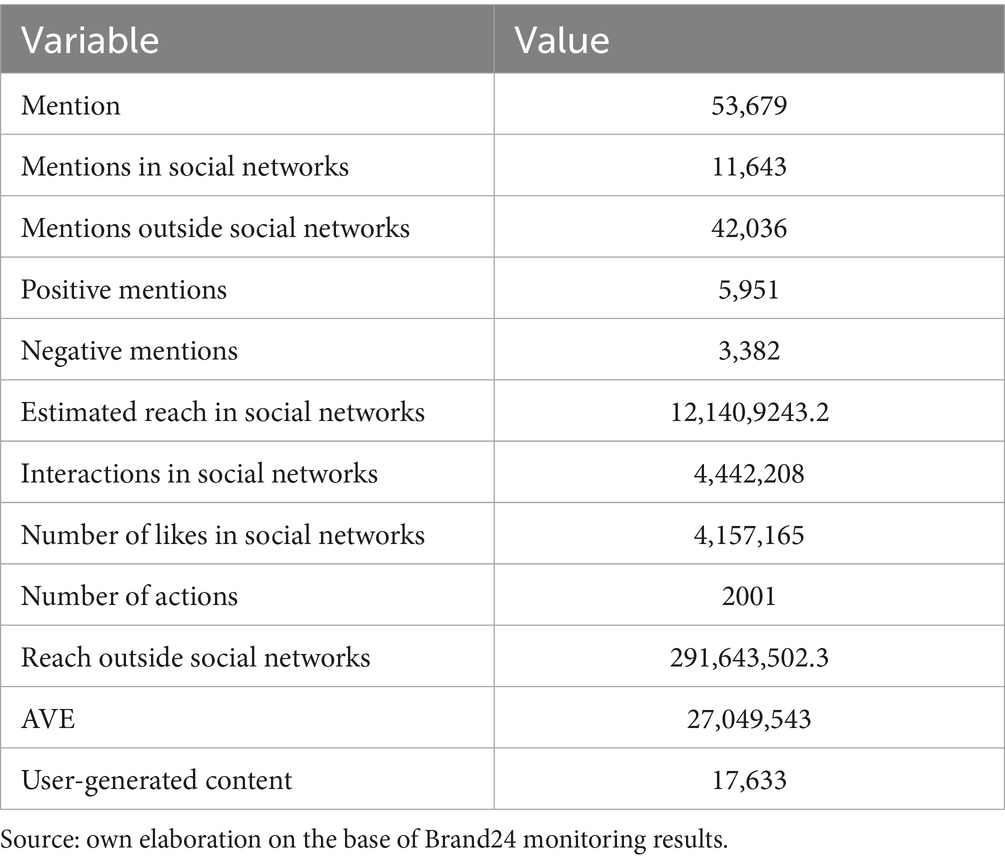

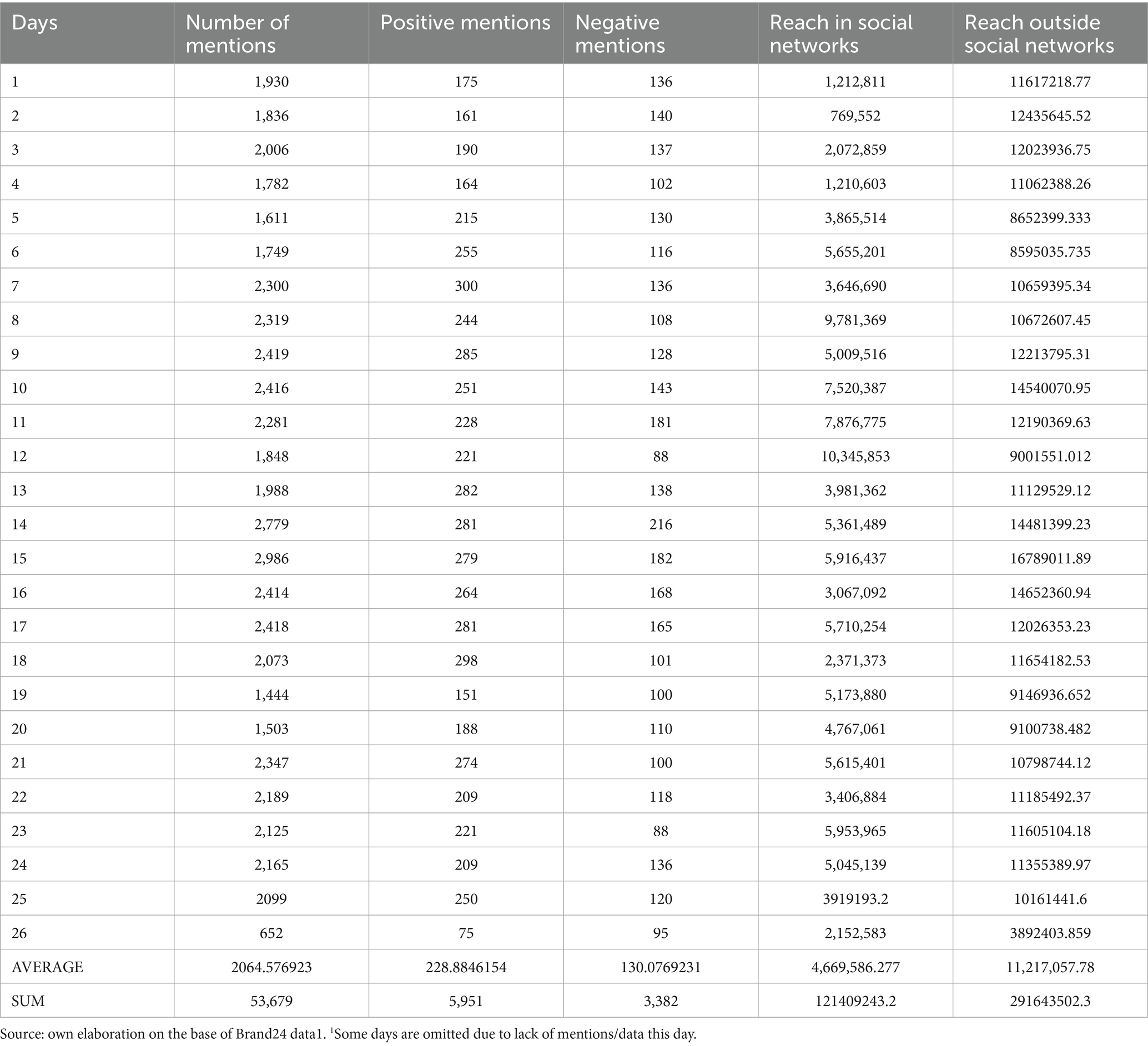

For the established keywords, “lobby(−ing)” and “EU,” there have been 53,679 mentions in total over 60 days of monitoring, generating 3.9 million “likes” and 2,001 interactions on social networks, as shown in Table 1. Among those mentions, 42,036 originate from online media other than social networking sites, while 11,643 come from various social networking sites (only 87 are from Twitter). The majority of mentions occur on Monday mornings around 8 a.m.

Regarding SO1, we can see in Table 2 that grassroots and mobilization activities primarily take place outside social networking sites—42,036mentions compared to 11,643 mentions on social networks. The estimated reach of all 53,679 mentions is 121,409,243 users on social networking sites and 291643502.3 on other social media platforms, with a total of 4,442,208 interactions and 4,157,165 likes on social networking platforms. Among the mentions examined, 17,633 are classified as user-generated content. The total equivalent value of advertising for all these social media and further digital media actions is estimated at over 27 million dollars. This indicates that the value of social conversations, content, and activity equates to a 27 million dollar investment in advertising for the analyzed period.

As shown in Figure 1, the most active channels were mentions about lobbying in the EU, which appeared in news (29,449 mentions), video platforms (10,991 mentions), and the web (6,597 mentions). The most active social media platform was YouTube, with 10,598 mentions.

Of the 53,679 mentions gathered in the study, 10,626 are videos (including 80 from TikTok); 23,774 are classified as news; 5,359 come from websites; 3,397 from blogs; 1,431 mentions are published on forums; and 133 are categorized as podcasts.

The main sources are news (23,774 mentions), video (10,253 mentions), and web (5,359 mentions), followed by blogs (3,397), forums (1,431), and podcasts (133). Surprisingly, X (Twitter) is not one of the most active channels for mentions, with only 87.

The most influential mentions come from youtube.com (9,860) with 30 billion visits, yahoo.com (21) with over 3.6 billion visits, reddit.com (919) with over 3.5 billion visits, and TikTok with 80 mentions and 2.7 billion visits. The most popular mentions come from youtube.com and Twitter (X), published and shared by private individuals or influencers.

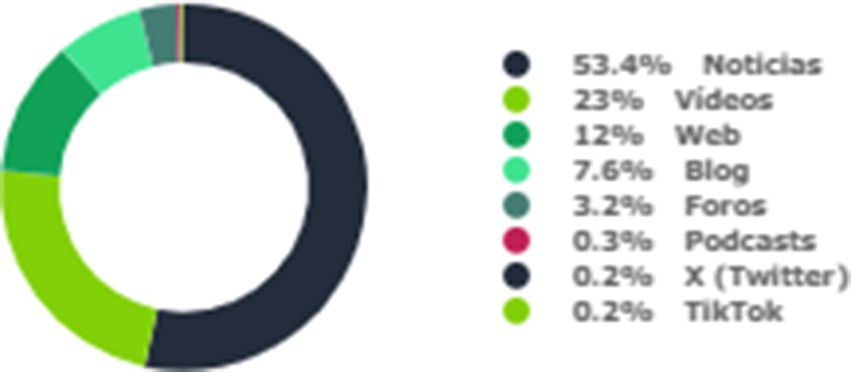

The sources of the mentions generated in digital discourse on predominant topics are diverse, with news being a well-established source, generating over 80% of the mentions on each of the analyzed topics, as shown below in Figure 2:

The other most popular sources are the web, videos, and blogs. Forums, podcasts, newsletters, and X (Twitter) are the online resources that are the least frequently mentioned across any of the 10 topics. News is the main source in the case of the aviation industry in the EU (83% of mentions), followed by monkeypox vaccines and EU environmental policies (81 and 80%, respectively). USA politics and the conflict in the Middle East are topics in which news is cited as the source between 63 and 65% of the time. These two topics also see blogs as the second most important source of mentions, with 15 and 18%, respectively. Meanwhile, videos generate 14% of mentions for the topic of geopolitics and 10% for EU regulations on AI. Web sources account for 15% of mentions regarding EU policies. Forums do not exceed 5% of all mentions—4% for the EV market and 5% for US politics. Newslettersaccount for mentions related to US policies and the conflict in the Middle East (4% in total), while X accounts only for the latter, at 1%. TikTok appears as a source for environmental policies in the EU and geopolitics, contributing only 0.7% of mentions. LinkedIn and podcasts generated mentions regarding EU regulations on AI, totaling 2%. Podcasts are rarely used but also generated mentions about the conflict in the Middle East (0.5%) and monkeypox vaccines (1%).

As per SO2, the average number of mentions per day is 2,064, with 228 positive and 130 negative mentions. The average reach on social networks is 4,669,586.277 users, which is outweighed by 2.5,an average daily reach outside social networks of 11,217,057.78 users.

In terms of sentiment, among the 53,679 mentions, 5,951 are positive, 3,382 indicate negative sentiment, and the rest are marked as neutral.

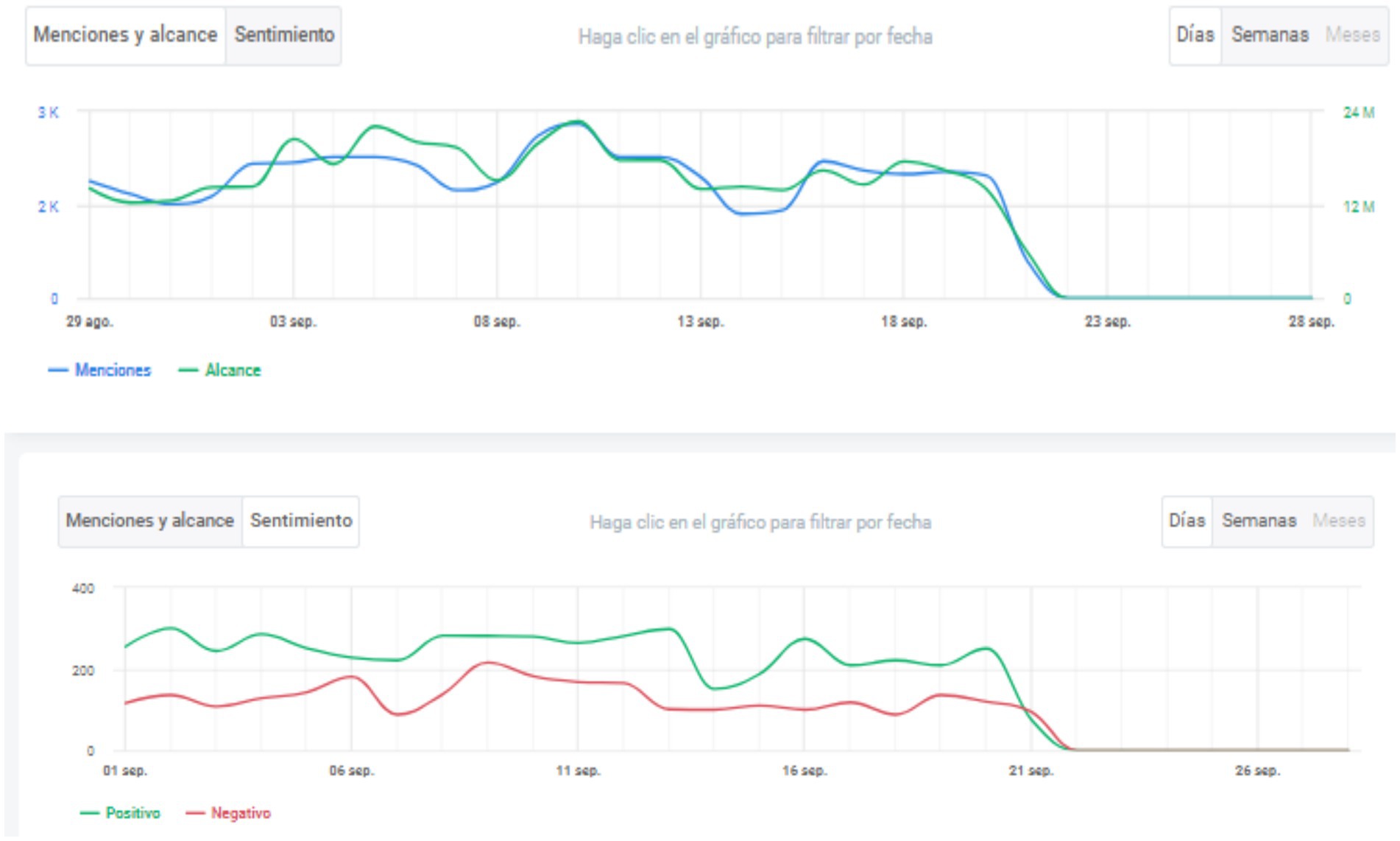

The evolution of mentions and reach, shown in Figure 3, reveals the scope and intensity of the lobby discourse on different policies in the EU, demonstrating generally few peaks in the first 2 weeks—between the 2nd and 12th of September—along with a downward trend toward the end of the analysis period.

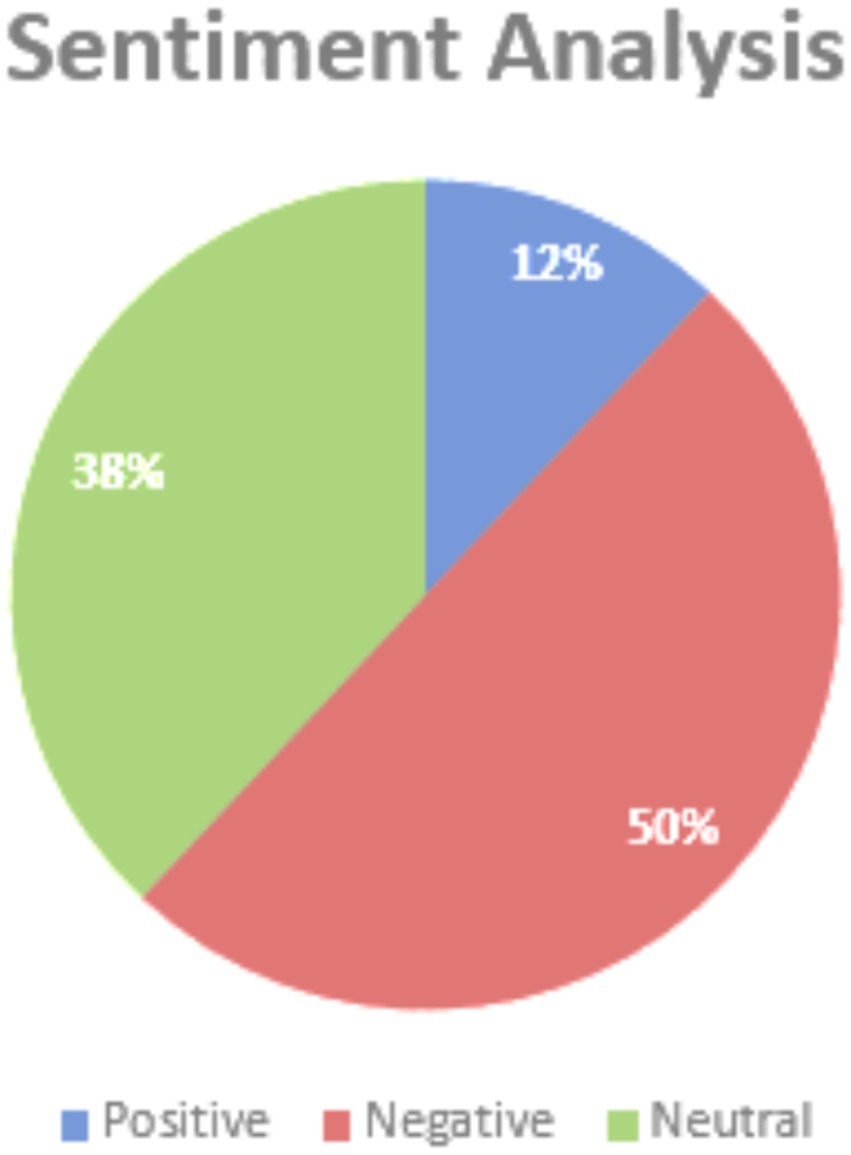

The trend of reach and mentions coincides with the evolution of sentiment in social conversations across digital media. Fifty percent of all mentions indicate negative sentiment (26,839 mentions), 38% are neutral (20,398 mentions), and only 12% (6,441 mentions) reflect positive sentiment in the analyzed conversations (Figure 4).

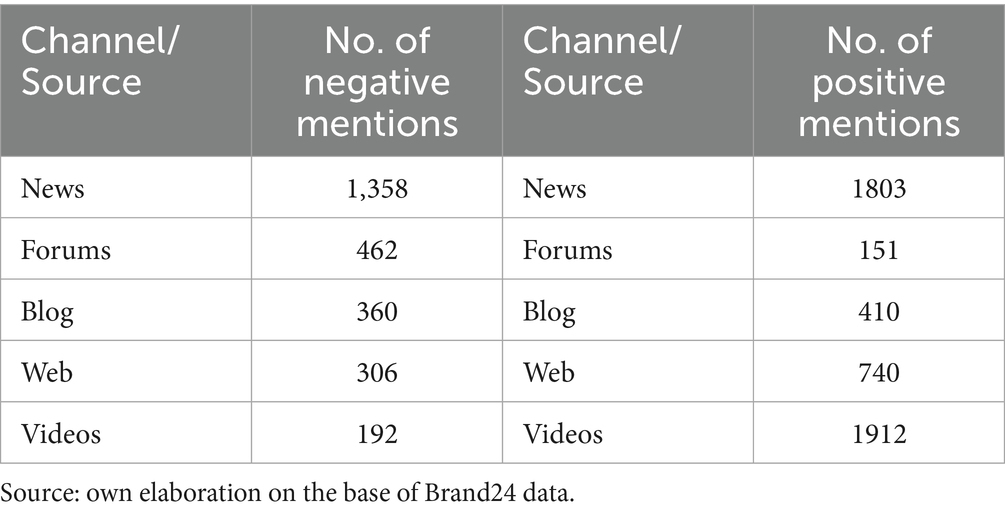

However, positive and negative sentiments demonstrate different dynamics in terms of sources (Table 3). The main channels of social conversations with more than 100 mentions over the examined period that provide a higher number of positive mentions are news, blogs, websites, and videos, while the primary source of negative mentions is mainly forums. Notably, videos significantly outweigh other sources with much more positive sentiment—1,912 mentions—in contrast to just 192 negative ones. Considering the Paid-Earned-Shared-Owned model, it is clear that positive mentions stem from Owned and Earned content (news created based on press releases, websites, blogs, and videos), while debates on forums may lead to more negative mentions when there is no control over the message.

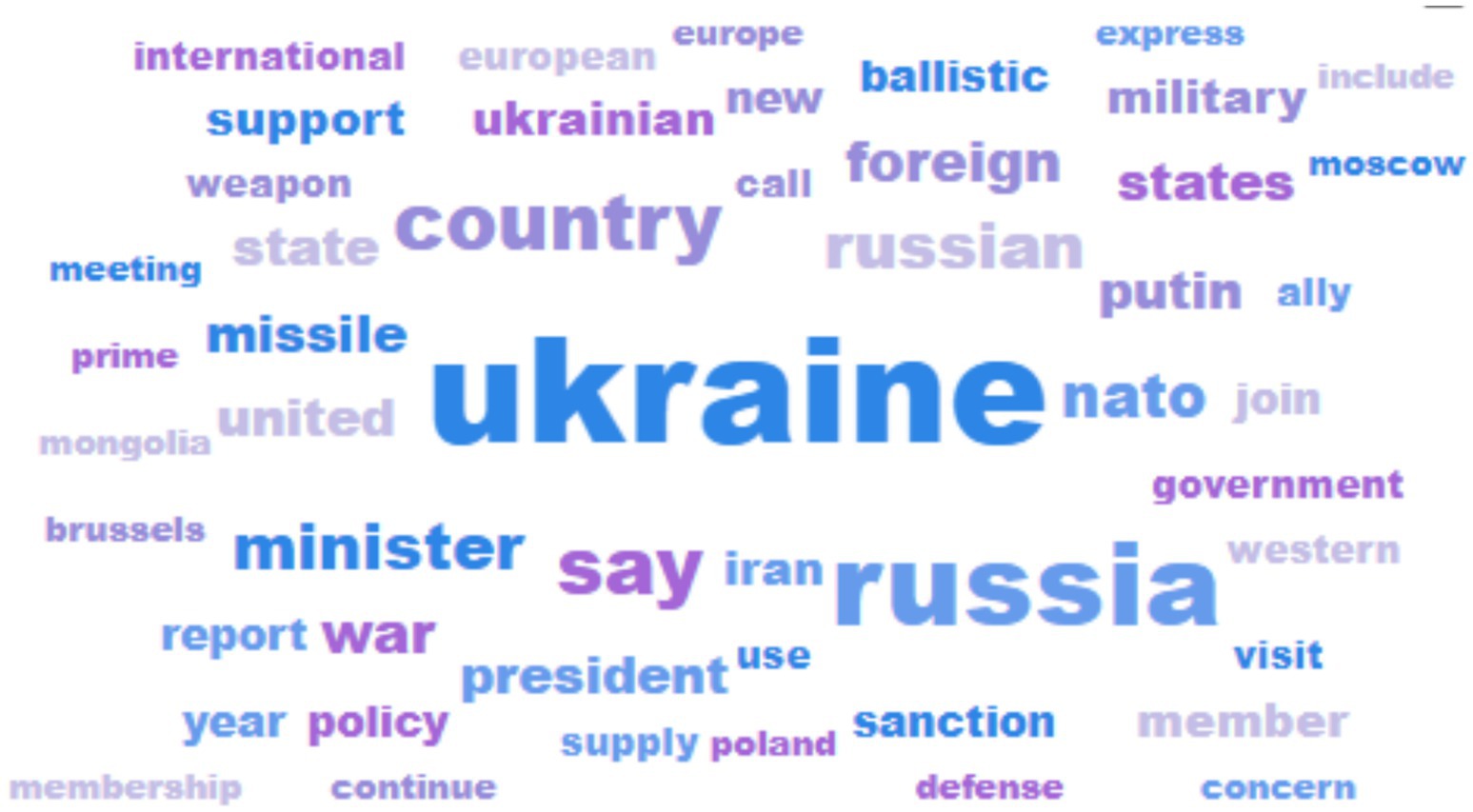

The most used keywords are the following: European, government, global, good, right, report, international, Russia, country, people, state, united, market, support, Europe, China, regulation, policy, Ukraine, business, and India. Therefore, the main focus is on international policies, with the market and business perspective concentrating on regulations and the role of emerging powers such as China and India, alongside the central topic of the Russia–Ukraine war. These topics address global issues, right-wing politics, and various countries or states.

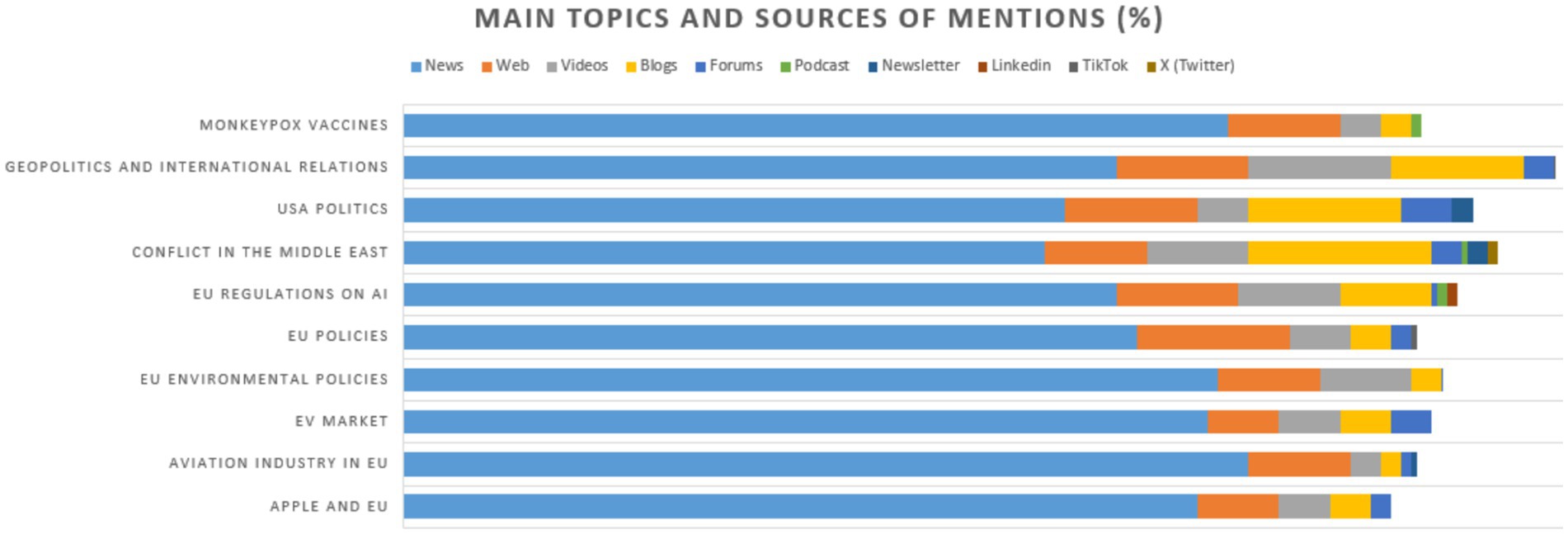

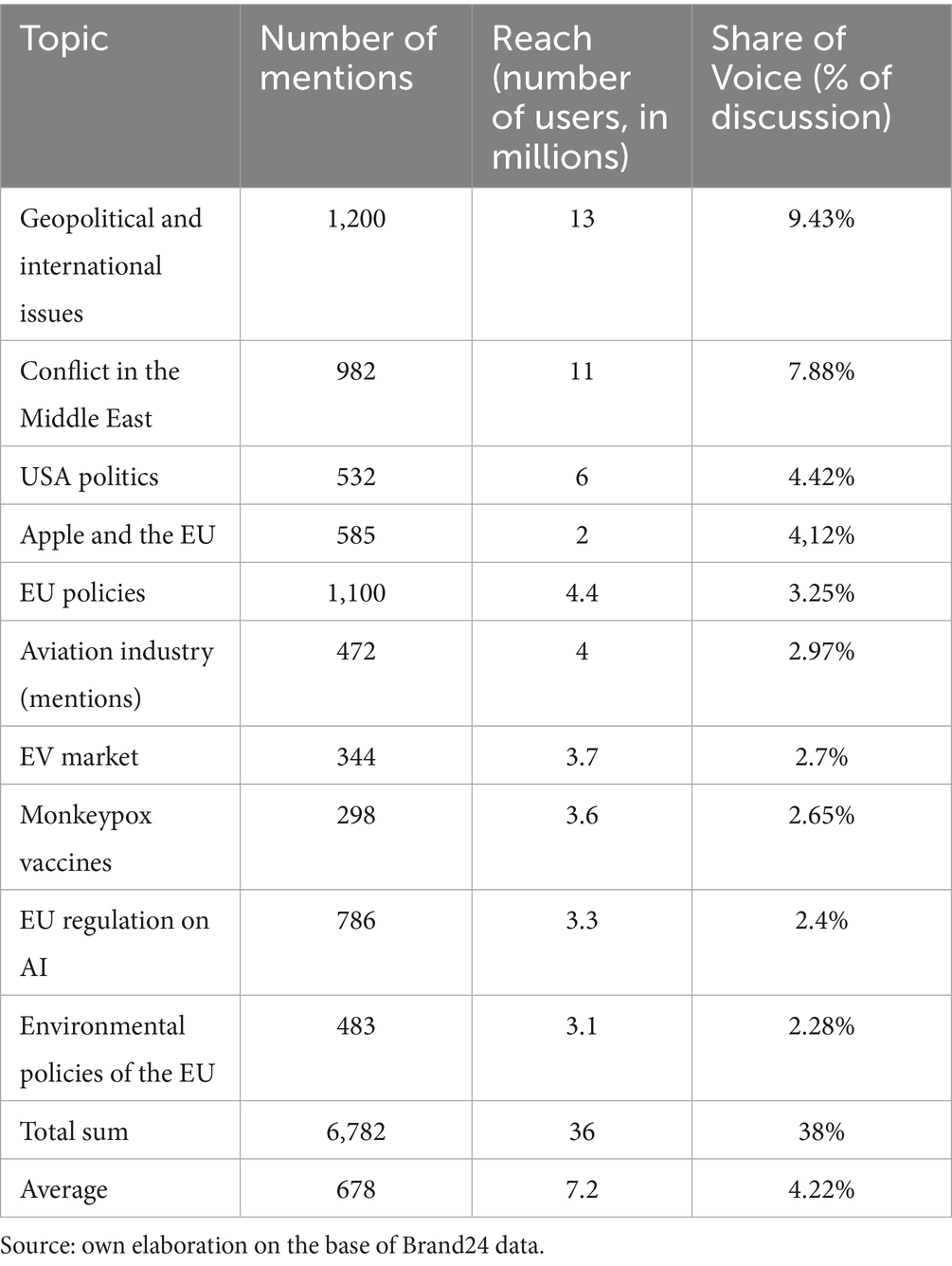

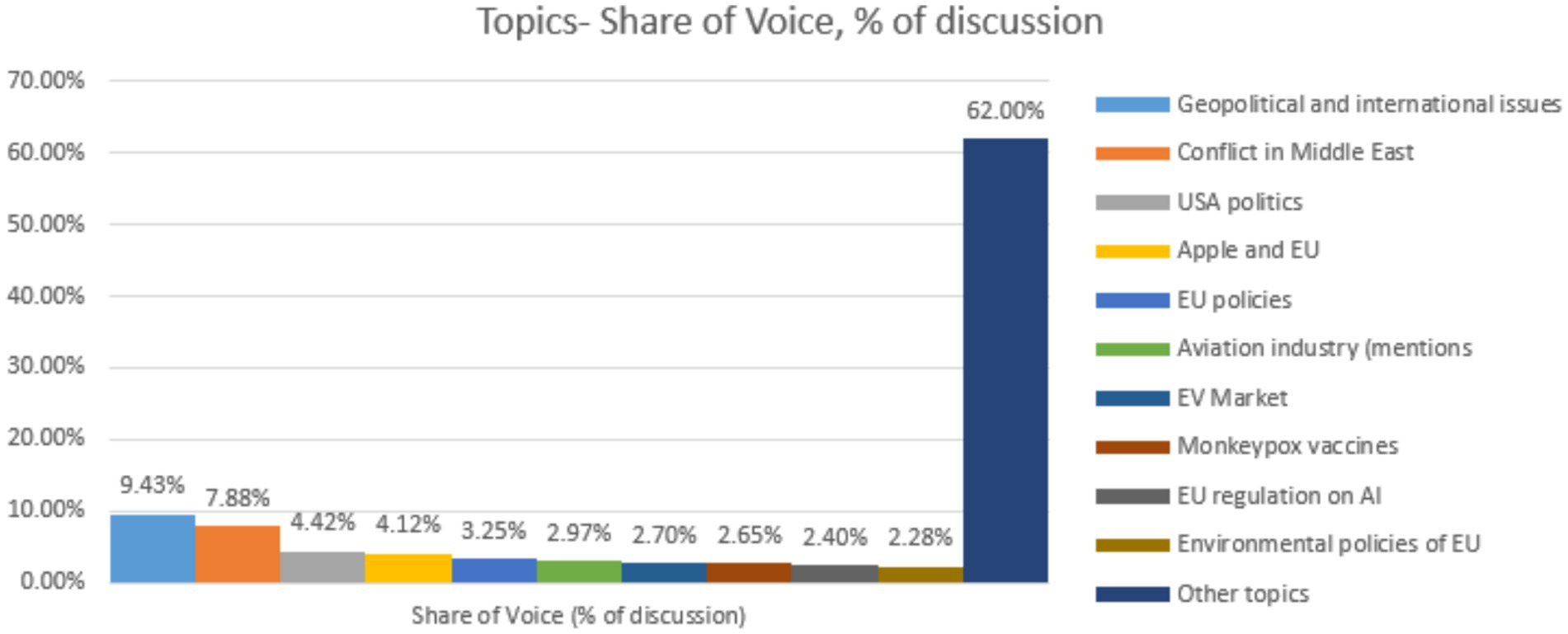

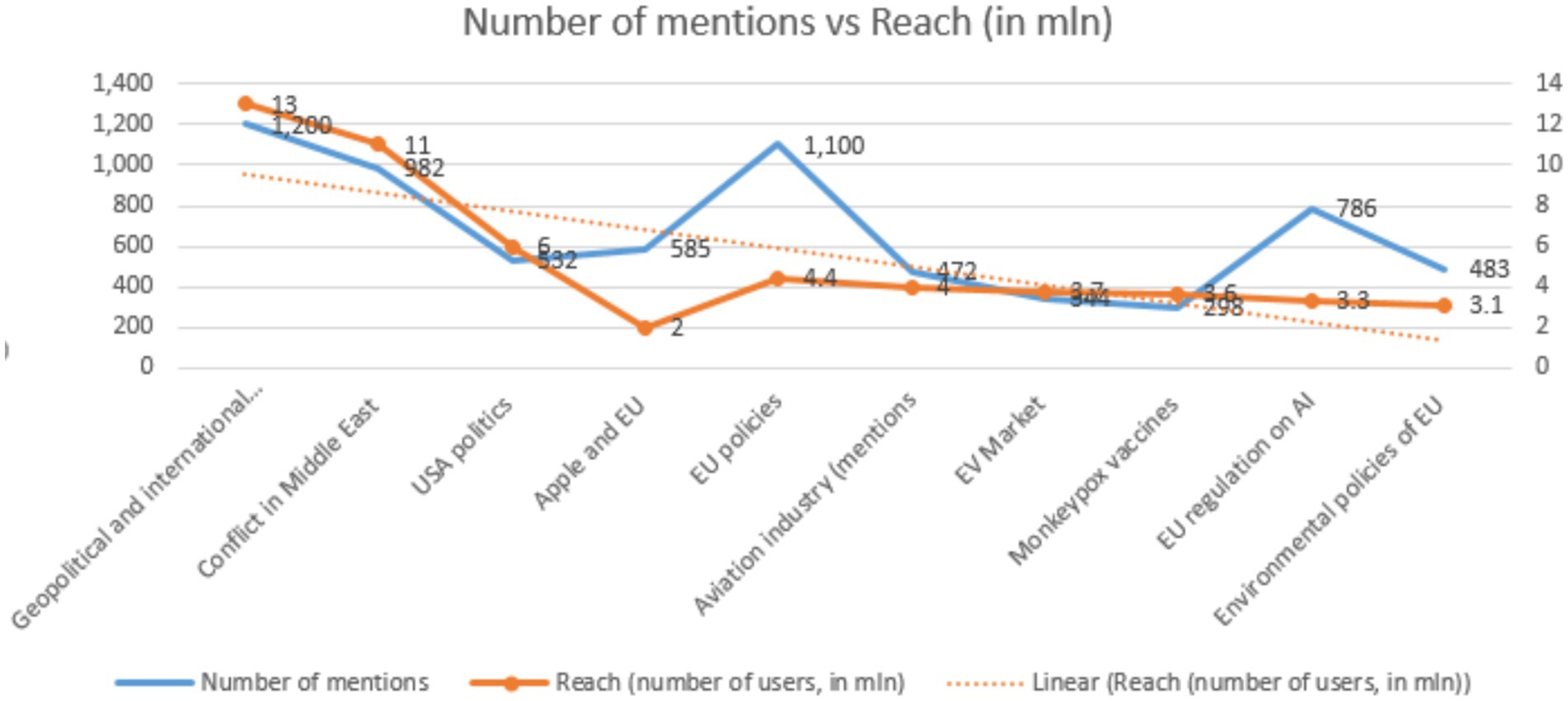

The dominant topics (Table 4) in online discussions regarding lobbying in the EU revolve around geopolitical and international issues, particularly the war in Ukraine, the conflict in the Middle East, and USA and EU policies, especially concerning the environment. Additionally, key industries or legal/business issues are highlighted, such as aviation regulation, the AI legal framework, the practices of Apple and Google in the EU, the EV market in light of Chinese competition, and medical aspects (e.g., Monkeypox vaccines for a potential epidemic). In total, these 10 topics have generated 6,782 mentions, reaching 36 million users, with a 38% share of voice in digital discourse regarding lobbying in the EU. On average, the main topics, as shown in Table 4, generated 678 mentions that reached 7.2 million people, accounting for 4.2% of online discussion during the analysis period. The other topics are given in Table 4.

The topic occupying the majority of online discussion (9.43%) concerns geopolitical and international issues, with the highest number of mentions (1,200) and the largest reach (13 million users), demonstrating a prevailing negative sentiment. The second topic reaching the highest number of users (11 million) is the conflict in the Middle East, which also has the highest share of voice—7.9%—and is the third most discussed topic in terms of number of mentions (982). The second and third most discussed topics, in terms of mentions, are EU policies and EU regulation on AI, with 1,100 mentions and 786 mentions, respectively. Regarding share of voice, USA politics ranks third, behind geopolitical issues and the Middle East conflict, with 4.42%, slightly above average. Environmental policies of the EU occupy 2.3% of overall discourse but generate more mentions—483—than monkeypox vaccines (298), and they are also the topic with the smallest reach of all 10 topics identified—only 3.1 million users, even less than EU regulations on AI and monkeypox vaccines, which reached 3.3 million and 3.6 million users, respectively.

Figure 5 shows the comparison of the size of discourse on each of the 10 topics, which together account for 38% of all digital discourse on lobbying in the EU:

The hashtag analysis, due to the limitations of the monitoring tool, did not yield significant results, with #shorts being the most used hashtag (2,013 occurrences). The most popular links come from YouTube, Instagram, and Google Maps. The most active public profiles include Military Tube (YouTube) with 136 mentions, focused on military issues and relations, and EU Debates (eudebates.tv) with over 153,000 followers and 68 mentions on the topic. Among the most influential digital media in the ongoing discourse on lobbying in the EU, social media platforms dominate: first is YouTube (9,860 mentions), followed by Yahoo, Reddit (919 mentions), and TikTok. Among the most active platforms are social networking sites such as Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn. Wikipedia and Quora (401 mentions) also appear as influential and active digital media, but they rank below social media and social networks.

Among the above-determined topics, those with the most negative sentiment are the conflict in the Middle East, USA politics, and the environmental policies of the EU. The other topics generating the highest number of mentions include EU policies, the conflict in the Middle East, EU regulations on AI, and Apple’s relations with the EU. Although the majority of mentions are neutral, negative sentiment is more frequent across all topics, except for the aviation industry, where the predominant sentiment is positive. However, the environmental policies of the EU are the least discussed among all indicated topics, accounting for only 2.28% compared to international and geopolitical concerns. The qualitative evaluation of the most popular mentions confirmed this trend, with comments focusing on the Ukraine and Russia war, the EU, Europe, Western governments, Brussels, and NATO, as shown in Figure 6. This discourse creates an overall negative sentiment, with disgust as the leading emotion (3% of the mentions).

Similarly, the discussion concerning the Middle East focuses on Israel, the USA, terrorism (Hamas), and the military–political and international situation, including security, military operations, government (Israeli president, ministers, political talks, pressure, rights, foreign and domestic policy, diplomacy, the West, support), and war (Gaza, attacks). The most popular keywords cover international topics, mentioning Canada or Borrell and portraying Israel negatively (Zionist, Jewish hostage). The discourse on this topic is predominantly characterized by negative sentiment, with opinions expressing disgust (10% of mentions) and fear (2%).

Another topic focuses on USA politics, including the following issues: security, presidential elections, campaigns, Trump and Harris as candidates, gun policy, abortion, violence, business, and the Republican government. Mentions of policy, lobbying, and political influence occur more often than other keywords. The dominant sentiment is negative, expressing emotions such as disgust (17%), fear (1%), sadness (1%), and anger (1%).

In terms of topics regarding Apple and the EU, the European Commission, European Union, lobbying, Google, and antitrust are frequently mentioned, along with keywords related to the legal framework, regulations, and legal processes (rule, legal, order, appeal, court) as well as tech challenges. It also addresses taxes, Google’s dominant position (“giant,” “rival”), and business perspectives (“taxes” “euros”). It discusses antitrust issues, the EU’s position in terms of regulations, court rulings regarding data privacy, search features, intelligence gathering, and app blocking. It refers to the rivalry and actions taken by Google and Apple, as well as decisions made by the EU and its courts concerning certain features and business practices of big tech companies. Therefore, the context is the legal decisions made by EU courts regarding Apple and Google. The discussion of this topic indicates significantly more negative sentiment than positive.

Another topic relates to aviation and focuses on aircraft safety concerning the incident with Cathay Pacific’s Airbus A350: the aviation safety agency, specifically the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), inspections, (European) directives, Airbus, aircraft, market, and government requirements. Another example is the analysis of keywords in the electric vehicle market. The debate centers on the import tariffs of Chinese electric cars and batteries into the EU and covers topics related to domestic and foreign manufacturers such as Tesla, trade agreements, emission regulations, the vehicle industry in European countries, the EV market, subsidies, and international trade relations with Canada and the USA. It reflects the state of European debates and the influence of international events on EU policies across different industries, as well as the wellbeing of citizens and regulations in the European aviation or EV industry. Regarding sentiment, aviation safety generates a positive sentiment, while EV market regulations are met with prevailing negative sentiment in the analyzed mentions.

As far as EU policies are concerned, the below Figure 7 illustrates the main focus of the online debates:

According to the most frequent keywords analysis, the policies are member country/state focused, primarily concerning migrants or migration and economic challenges, and covering diverse issues of both political and economic nature on an international scale: trade, markets, the euro, work, political support, Germany’s role, regulations, cooperation with the UK, investments, the European Commission, governments, nations, borders, and security. The discussion takes a global perspective, including regulations, decisions, and reports as elements of the political process, while emphasizing the need for policies within the European Union. Although the sentiment analysis is mainly neutral, it indicates that negative opinions prevail over positive ones.

Among these, thanks to LDA, two policies were identified as the most frequently mentioned and co-occurred mostly with EU policies: AI regulations and environmental policies, both within the EU.

The topic of AI regulations reflected in online discussions focuses on law, analyzing both international and national impacts, treaties, and considering risk, privacy, compliance, and the digital framework. It mentions GDPR, legal acts, Russia, and the roles of Europe and its member states, while also addressing economic exchanges (companies, stock market, and economic relations with the UK and the energy sector). Although the sentiment is mainly neutral, negative expressions dominate over positive ones.

The environmental policies cover a wide range of issues, primarily focusing on wine trade and the global wine market. It addresses countries, recognitions, registrations, and regulations, indicating the need to reduce emissions, tackle climate change, geographic recognition in the wine industry, global aspects, green energy in the sector, setting corresponding targets to lower carbon emissions, problems with deforestation, and issues such as strikes and trade deals. The debates centers on EU eAmbrosia—a legal register of the names of agricultural products, wine, and spirit drinks that are registered and protected across the EU. This topic mainly elicits negative sentiment, significantly dominating over positive emotions, with disgust being the primary emotion expressed in the analyzed mentions.

Regarding SO3, the EU countries with significant social conversation reach on lobbying and the EU are Spain (621 mentions, reach of 3,844,491), Poland (603 mentions, reach of 158,511), France (530 mentions, reach of 639,864), and Italy (516 mentions, reach of 180,898), with the UK, as an ex-EU country, being the most active (1,672 mentions, reaches more than 3.5 million people). However, in terms of reach, 79% is achieved in India and the USA (followed by Spain and the UK), whereas 54% of the mentions are found in the USA, India, Australia, Brazil, and Argentina, as well as in Europe in the following countries: the UK, Spain, France, and Poland, respectively. Ninety-one percent of interactions cover a similar area to the origins of mentions; however, it additionally includes countries such as China and Turkey.

The main influencers participating in the debates are primarily international media outlets and news platforms from different parts of the world, with TEDx Talks in the first position and Jamuna TV from Bangladesh in third, followed by CBN News, BBC News, Al Jazeera English, tvOneNews, NDTV, and Inside Edition. It is not that there are no EU television, press, or other media outlets among the most active influencers in the analyzed debates and online conversations. The media outlets account for 53% of total mentions and are primarily sourced from the YouTube platform. These influencers are largely responsible for negative sentiment, while positive sentiment is highly dispersed among multiple authors; meanwhile, negative sentiment is concentrated in the main news titles. That said, neutral sentiment is present in 86% of the mentions by influencers (2,503). The remaining 14% is divided into 8.8% of admiration and 5.2% of negative emotions such as disgust, outrage, sadness, or fear. The emoji analysis yielded inconclusive results, as the emojis appear to be randomly placed and express a variety of meanings, emotions, and clues.

When analyzing the reach and number of mentions for 10 topics, we can observe a declining tendency in interest regarding international issues compared to environmental policies, as shown in Figure 8:

Figure 8. Number of mentions versus Reach (in millions of users). Source: own elaboration on Brand24 data.

Whereas geopolitics, conflict in the Middle East, and USA politics generate both the highest numbers of mentions and reach, topics such as the EV market, monkeypox vaccines, and the aviation industry have the lowest number of mentions and reach. However, higher levels of mentions do not directly result in superior levels of reach. Apple in the EU is discussed fairly often, with almost 600 mentions (one of the most discussed), but has far more limited reach in comparison to other topics (2 million users). Similarly, EU policies produce 1,100 mentions but achieve a reach of 4.4 million users—we can see the discrepancy on the graph—EU policies are far less discussed than international issues and conflicts, including USA politics. EU regulations on AI—with 786 mentions reaching 3.3 million users—demonstrate a similar pattern.

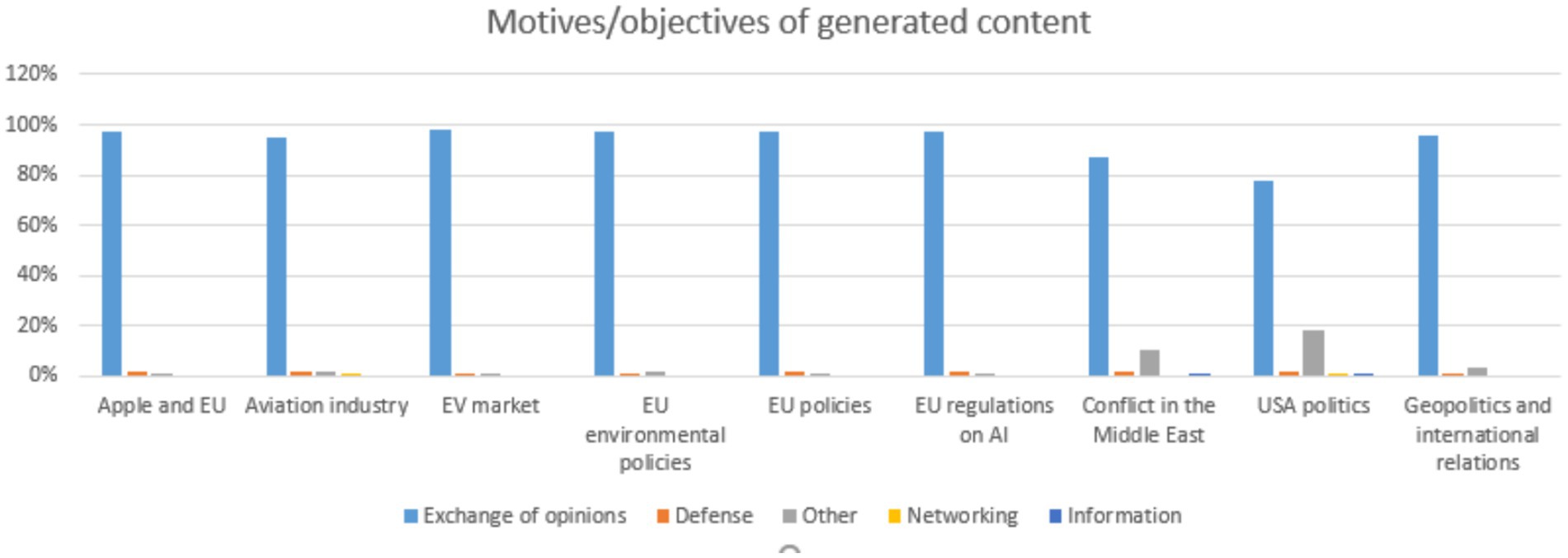

Regardless of the topic and source of mention, the main objectives of the mentions serve the purpose of opinion exchange (from 95 to 98% of mentions for each of the eight topics), as shown in Figure 9.

Conflict in the Middle East indicates lower levels of such motivations (87%), along with USA politics (78%). The defense of opinion or position ranges between 1 and 2% of all mentions, regardless of the topic, while networking appears in 1% of mentions for the aviation industry and USA politics, similar to informational purposes in the case of the conflict in the Middle East and USA policies. Thirty-nine percent of all mentions for all 10 topics are classified as other objectives, including exchanges of greetings, entertainment, emojis, etc.

4 Discussion

The results confirm that social media may not play an empowering role for different interest groups in terms of content creation, visibility, or representation, but they do attest to the existence of “grassroots lobbying.” Additionally, it describes the mechanism, dynamics, and scope—from UGC-created content, its formats, content reach, number of messages, and their motivations and emotional factors to qualitative insights on textual content and presence across different media and channels.

The data evidence a wide range of digital platforms employed, including news outlets, websites, and UGC such as videos, blogs, and podcasts. The latter, although currently limited, may become a powerful tool to balance the discourse on the most popular platforms. In particular, as shown, when X, previously known as Twitter, has been reduced as a source of mentions and messages, LinkedIn (as seen in the case of the AI topic) may serve as a platform for professional discussions. The analyzed messages are oriented toward exchanging opinions rather than defending a particular position, so grassroots mobilization seems to focus more on sharing opinions to influence rather than on direct advocacy for specific purposes. This aligns with previous findings that social media, in particular, and other digital media, in general, serve for open consultations to better align messages with public expectations and preferences.

The communication of lobbying in the EU through digital media represents a complex interplay of strategies, actors, and regulatory frameworks. As interest groups adapt to the digital landscape, the implications for democratic engagement, transparency, and ethical advocacy are significant. The ongoing evolution of lobbying practices in the EU highlights the importance of understanding the multifaceted nature of political communication in a rapidly changing environment, with a particular emphasis on digital media and its role in lobbying practices. Therefore, this research explores the implications of these trends for both policymakers and interest groups, especially in light of the challenges and opportunities presented by digital media, particularly social media. In summary, the communication models employed by lobbyists in the EU combine traditional and digital strategies. Social media serves as a powerful tool for advocacy, enabling interest groups to mobilize support and engage effectively with policymakers. However, the success of these strategies depends on the resources available to the groups and their ability to align with public opinion. As the landscape of lobbying continues to evolve, understanding these dynamics will be crucial for both practitioners and scholars in the field.

The digital lobby practices and DMC discourse on lobbying in the EU illustrate the diverse communication strategies occurring across a wide range of online media, including, but not limited to, social media. In this sense, mentions outside of social networks are predominant—there are three times more mentions outside social networks than within them. This indicates that discussion and dissemination strategies primarily occur outside of social networking sites. The volume of generated mentions demonstrates the public engagement of audiences in these practices. The online media presence is significant as it enhances public visibility in terms of audience reach and created content, both in quantity and quality. As demonstrated, a multifaceted approach encompassing various online sources, including video and audio formats (such as TikTok or podcasts), is central to effective lobbying strategies and fostering broad online debate. The communication practices of advocacy and influence in digital media are complex, ranging from information dissemination to mobilization and grassroots involvement, according to the data, with active participation from a variety of interest groups. The digital landscape has transformed, creating more dynamic interactions among different players in lobbying communication processes, reaching almost 4.5 million interactions in social networks during the analyzed period. The study confirms that social media has become a leverage platform for lobbying digital discourse strategies, not only for main social networks but also for other social media platforms. The strategies encompass dissemination tactics outside social networking, an interactive approach within social networks, and the use of media outlets present in social media to reach audiences with information and issues—from 12 million users in social networks to over 291 million users outside them. The data demonstrate that digital media, especially social media with their digital formats, especially videos on the YouTube platform, can be considered effective in terms of influence (mentions, interactions, sentiment, and reach) when shaping public discourse online. These effects can be measured, making them a powerful tool for political communication aimed at influence and advocacy. The main formats utilized are news articles but also include content published on websites and blogs, with almost 1,500 mentions in forums and 133 podcasts. This indicates that DMC in the lobbying area relies on information and dissemination tactics across different social media platforms while also employing new digital forms such as podcasts and striving to build conversations with stakeholders across online media (forums, blogs). It underscores the importance of media discussions for interest representation, as the news category is the primary source of mentions; this does not exclude media as a whole; it simply modernizes the tools. The discourse, however, reflects both economic and political orientations, with international issues, such as conflicts, being predominant in the online debate generated by digital lobbying strategies. Specific topics concerning marginalized groups receive less participation in the digital lobby’s discourse, both in terms of generated mentions and reach. The online discussion, as analyzed, demonstrates its complexity regarding sources, dynamics, and the variety of topics and issues included in the debate; thus, the EU needs to address concerns regarding the legal framework and scrutiny of lobbying activity online, particularly when foreign affairs and lobbies are involved.

In terms of narratives and framing policy issues, the keyword analysis of the most frequently used expressions and LDA models validates the importance of a narrative-driven approach. Storytelling and the use of adequate formats, such as video or podcasts, can help enhance public engagement by generating a higher number of messages and reaching more users across the digital ecosystem, as observed in cases involving geopolitical issues, EU policies, etc. The detection of the most used keywords, their associations and patterns of discourse, as well as their dynamics, can help mobilize grassroots movements and create “networked advocacy” in the media where the audience actually is, which varies by topic and theme. This approach can increase awareness of a particular subject, build community, and enhance support. It not only broadens the voices, as Reach data showed us, but also amplifies voices, such as experts on AI or citizens concerned with the costs of environmental policies or economic factors in the EVV market. However, as the mention versus reach analysis proved, lobbying efforts need to be more efficient and targeted simultaneously. Emotional factors, narrative, and media type (audio, video) play a crucial role in shaping the digital strategies of lobbying for any of the topics. The data show, however, that connection and collaboration are not the main objectives in the lobbying discourse, nor is information exchange. Nonetheless, these objectives may change from topic to topic (e.g., international security policies and the economy) and will shape the media source strategy differently. The study did not differentiate the size and resources of the lobbying groups but focused on the capacity of the narrative to dominate other topics in terms of reach and scope of online debate. In alignment with previous studies, it provides another example that business voices prevail over non-business interests (Beyers and De Bruycker, 2017), as can be seen in the case of the EVV market or Apple in the EU; however, a properly constructed measurement procedure, as presented, may allow for further steps to balance the democratic process in the EU. The findings of the debate on AI regulations in the EU show a more balanced approach in digital practices that also concern citizens’ protection.

The richness of the content on the major topics discussed online corroborates the complexity of the EU legislative environment on many matters, from aviation safety to vaccine policies. Nevertheless, the prevailing negative sentiment, especially regarding environmental policies and EU actions in member states, provides insight into public attitudes—lobby activity does not guarantee that EU institutions will align public positions or that citizens will influence EU decisions.

Although the analysis of digital lobbying strategies does not directly address equity issues in advocacy, it offers valuable insights confirming that increased public participation in digital discourse and media activity serves as the main source of messages, though it does not clarify which voices are more prominent. These aspects could become subjects for future studies. The data demonstrate varying levels of engagement and interactions among the public across European countries, showcasing different levels of community activity. For instance, Spain and the UK show higher levels of public debate involvement, indicating significant engagement among the public in online conversations. However, UK online debates feature a higher number of mentions than those in Spain, making them more active. Although there was a focus on EU audiences in terms of community building, the data reveal that the major part of mentions and interactions comes from outside the EU. Therefore, it was not possible to determine patterns for building an EU community around issues promoted by lobbying in online media. However, it can be concluded that influencers in this context are primarily media outlets and platforms characterized by relatively high levels of authority and trust. Media as influencers are the most significant in shaping the community around various topics; however, they are mainly sourced from YouTube. Therefore, the community is mainly formed on this platform, influenced by the negative sentiment expressed in official media sources. The negative sentiment surrounding geopolitics appears to be the predominant pattern in shaping the engaged community, but further studies are necessary to confirm the observed social phenomena. Nevertheless, community building hinges on opinion exchange as the main pattern, indicating an interactive orientation toward audience participation and mobilization.

As such, the proposed analytical framework contributes to enhancing the transparency and accountability of digital lobbying in the EU. It may improve openness and provide input for regulatory efforts. The changes in digital media and lobbying strategies, both inside and outside social media, as shown in the study, have widened the scope of public involvement but also present challenges for analyzing such a complex data system. The study demonstrates a possibility to capture and measure this data for further analysis, allowing for the detection of patterns in digital discourse and the examination of lobbyists’ digital communication practices. Moreover, the proper methodological framework helps to determine the overall audience sentiment, sentiment embedded in the messages, the relevance of the issues, and the content of various discussions held across different digital sources and platforms. It can assess the overall public sentiment and the construction of messages to detect misinformation as well as prevailing topics in the proliferating online debates. This would help in adopting measures for ethical concerns.

Although the study continues the tradition of data mining, text mining, online tracking, and internet audience studies, and has been applied multiple times in various research contexts, it is not without certain limitations. Access to diverse communities, including marginalized or less active ones (including those active in less popular channels), real-time data requiring continuous online monitoring, and longitudinal studies to address real-time aspects are some examples of these limitations. Additionally, it may be an expensive and time-consuming endeavor that requires significant human and material resources, raising concerns about cost-effectiveness.

Social media, and more broadly, digital media, play a major role in shaping the communication strategies of lobbyists in the online ecosystem, as evidenced by the study. Given its complexity, the measurement procedure may help scrutinize the influence of interest groups and protect stakeholders in light of the lack of formal regulatory mechanisms. It also assists in scanning public opinion for potential manipulation and misinformation and in reforming practices to guarantee a higher level of public participation in shaping EU policies. Consequently, policymakers will rely on high-quality information regarding lobbying practices across diverse digital platforms and from many stakeholders interacting simultaneously, including both textual and quantitative data. The absence of formal regulation and transparency around lobbying practices in the EU has raised concerns about the potential for undue influence by powerful interest groups (Svendsen, 2011; Korkea-aho, 2022). As digital lobbying becomes more prevalent, there is a growing need for frameworks that ensure equitable access to decision-making processes and mitigate the risks of lobbying inequality (Davidson, 2017; Dür et al., 2015). Despite its limitations, the study contributes to a better understanding of the digital lobbying process and the role of digital media in these dynamics. The ability to examine and provide both quantitative and qualitative results of communication activities can address the challenges of transparency and accountability in lobbying within the EU, particularly in online media.

The proposed framework is a valuable tool for understanding the social and cultural dynamics of the digital age concerning digital lobbying in the EU context. By carefully considering the ethical implications and methodological challenges, researchers can gain valuable insights into how key stakeholders in the digital lobbying process interact, communicate, and create meaning in the online world. In doing so, they contribute to shaping discourse and policy outcomes, mobilizing communities, and ultimately enhancing online debates on key subjects related to the EU economy, security, political processes, democracy, and similar topics.

Ethical issues regarding data protection and privacy need to be addressed; however, using commercial software in the EU guarantees compliance with legal requirements. Data overload is a major issue, as the study produces an abundant amount of qualitative and quantitative data that requires further big data techniques to organize and analyze. The next challenge is data interpretation, especially in the case of text data, as contextual and nonverbal cues provide only a limited understanding. The software continues to evolve, offering emoji and visual analysis. Despite these limitations, it allows us to take a closer look at online social and political practices. Future studies may also expand the research to include the organizational communication of lobbies operating in the EU and their interactions with policymakers and audiences in a more direct manner, using digital tools for direct communication.

In conclusion, the communication of lobby activities in the EU through digital media is a multifaceted phenomenon that encompasses various strategies, challenges, and implications for policymaking. The interplay between digital platforms and lobbying practices highlights the necessity for ongoing research and regulatory considerations to foster a more transparent, equitable, and inclusive lobbying environment.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because purchase from funding. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to esmolaklozano@uma.es.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human data in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not required, for either participation in the study or for the publication of potentially/indirectly identifying information, in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platform’s terms of use and all relevant institutional/national regulations.

Author contributions

ES: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by ´´Lobby y Comunicación en la Unión Europea´´, of the Ministry of Science and Innovation (Spain), the State R + D + I Programme for Proofs of Concept of the State Programme for Societal Challenges, the State Programme for Scientific, Technical, and Innovation Research, 2020-2023 (PID2020-118584RB-100).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Almansa Martínez, A., Moreno-Cabanillas, A., and Castillo-Esparcia, A. (2022). “Political communication in Europe. The role of the lobby and its communication strategies” in Communication and smart technologies. Proceedings of ICOMTA 2021. eds. D. Barredo, P. C. López-López, I. Puentes-Rivera, and A. Rocha (Singapore: Springer), 238–248.

Almiron, N., and Xifra, J. (2016). Influence and advocacy: revisiting hot topics under pressure. Am. Behav. Sci. 60, 253–255. doi: 10.1177/0002764215615161

Andersen, S. S., and Eliassen, K. A. (1991). European Community lobbying. Eur J Polit Res 20, 173–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.1991.tb00262.x

Anduiza, E., Cantijoch, M., and Gallego, A. (2009). Political participation and the internet: a field essay. Inf. Commun. Soc. 12, 860–878. doi: 10.1080/13691180802282720

Banisch, S., Araújo, T., and Louçã, J. (2010). Opinion dynamics and communication networks. Adv. Complex Syst. 13, 95–111. doi: 10.1142/S0219525910002438

Baumgartner, F. R. (2007). EU lobbying: a view from the US. J. Eur. Public Policy 14, 482–488. doi: 10.1080/13501760701243830

Benoit, K., Conway, D., Lauderdale, B. E., Laver, M., and Mikhaylov, S. (2016). Crowd-sourced text analysis: reproducible and agile production of political data. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 110, 278–295. doi: 10.1017/S0003055416000058

Bernhagen, P. (2014). Lobbying in the European Union: interest groups, lobbying coalitions, and policy change. West Eur. Polit. 37, 1196–1197. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.924712

Beyers, J., Bonafont, L., Dür, A., Eising, R., Fink-Hafner, D., Lowery, D., et al. (2014). The INTEREURO Project: Logic and structure. Int. Groups. Adv. 3, 126–140. doi: 10.1057/iga.2014.8

Beyers, J., and De Bruycker, I. (2017). Lobbying makes (strange) bedfellows: explaining the formation and composition of lobbying coalitions in EU legislative politics. Political Stud. 1–26. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2015.1008551

Beyers, J., De Bruycker, I., and Baller, I. (2015). The Alignment f Parties and Interest Groups in EU Legislative Politics. A Tale of Two Different Worlds? J. Eur. Public Policy 22, 534–551.

Bocse, A. M. (2013). Lobbying in the European Union: interest groups, lobbying coalitions, and policy change. Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 26, 691–693. doi: 10.1080/09557571.2013.844922

Boräng, F., and Naurin, D. (2015). ‘Try to see it my way!’ Frame congruence between lobbyists and European Commission officials. J. Eur. Public Policy. 22, 499–515. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2015.1008555

Boumans, J. W., and Trilling, D. (2016). Taking stock of the toolkit: an overview of relevant automated content analysis approaches and techniques for digital journalism scholars. Digit. Journal. 4, 8–23. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2015.1096598

Brown, H. (2016). Does globalization drive interest group strategy? A cross-national study of outside lobbying and social media. J. Public Aff. 16, 294–302. doi: 10.1002/pa.1590

Bruns, A. (2013). Faster than the speed of print: reconciling 'big data' social media analysis and academic scholarship. First Monday 18:10. doi: 10.5210/fm.v18i10.4879

Bunea, A. (2014). “Explaining interest groups’ articulation of policy preferences in the European Commission’s open consultations. An analysis of the environmental policy area,” J. Common Mark. Stud. 52, 1224–1241.

Carty, V. (2010). New information communication technologies and grassroots mobilization. Inf. Commun. Soc. 13, 155–173. doi: 10.1080/13691180902915658

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2015). Strategies and communicative practices of political activism on social media in Spain. Hist. Comun. Soc. 20, 535–550. doi: 10.5209/rev-HICS.2015.v20.n2.51399

Castillo Esparcia, A., Smolak Lozano, E., and Fernández Souto, A. B. (2017). Lobby y comunicación en España. Análisis de su presencia en los diarios de referencia. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 72, 783–802. doi: 10.4185/RLCS-2017-1192

Chalmers, A. W. (2013). Trading information for access: informational lobbying strategies and interest group access to the European Union. J. Eur. Public Policy 20, 39–58. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2012.693411

Chalmers, A. W., and Shotton, P. A. (2016). Changing the face of advocacy? Explaining interest organizations’ use of social media strategies. Polit. Commun. 33, 374–391. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2015.1043477

Chari, R., and O'Donovan, D. H. (2011). Lobbying the European commission: open or secret? Social. Democr. 25, 104–124. doi: 10.1080/08854300.2011.579475

Cho, J. (2013). Campaign tone, political affect, and communicative engagement. J. Commun. 63, 1130–1152. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12064

Christner, C., Urman, A., Silke, A., and Maier, M. (2022). Automated tracking approaches for studying online media use: a critical review and recommendations. Commun. Methods Meas. 16, 79–95. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2021.1907841

Coffey, S. (2001). Internet audience measurement: a practitioner’s view. J. Interact. Advert. 1, 10–17. doi: 10.1080/15252019.2001.10722047

Davidson, S. (2017). Public affairs practice and lobbying inequality: Reform and regulation of the influence game. J. Public Aff. 17:e1665.

De Bruycker, I., and Beyers, J. (2015). Balanced or Biased? Interest Groups and Legislative Lobbying in the European News Media. Polit. Commun. 32, 453–474. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2014.958259

De Bruycker, I., and Colli, F. (2023). Affluence, congruence, and lobbying success in EU climate policy. J. Public Policy, 43, 512–532. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X23000120

de Vreese, C. H., and Neijens, P. (2016). Measuring media exposure in a changing communications environment. Commun. Methods Meas. 10, 69–80. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2016.1150441

Dinan, W. (2021). Lobbying Transparency: The Limits of EU Monitory Democracy. Politics Gov. 9, 237–247. doi: 10.17645/pag.v9i1.3936

Durán Vilches, M., Carcelén García, S., and Ruiz San Román, J. A. (2023). La producción de discursos sociales en entornos digitales: La comunidad digital como metodología de investigación social. Teknokultura Rev. Cult. Digit. Mov. Soc. 20, 183–194. doi: 10.5209/tekn.83473

Dür, A., Bernhagen, P., and Marshall, D. (2015). Interest group success in the european union: when (and why) does business lose? Comp. Political Stud. 48, 951–983. doi: 10.1177/0010414014565890 (Original work published 2015).

Erkkilä, T., and Luoma-aho, V. (2023). Alert but somewhat unaligned: public sector organisations' social media listening strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Commun. Manag. 27, 120–135. doi: 10.1108/JCOM-02-2022-0015

Feenstra, R. A., and Casero-Ripollés, A. (2014). Democracy in the digital communication environment: a typology proposal of political monitoring processes. Int. J. Commun. 8, 2448–2468.

Figenschou, T. U., and Fredheim, N. A. (2020). Interest groups on social media: four forms of networked advocacy. J. Public Aff. 20:2012. doi: 10.1002/pa.2012

Figenschou, T. U., and Thorbjørnsrud, K. (2020). ““Hey there in the night”: the strategies, dilemmas and costs of a personalized digital lobbying campaign” in Media health. The personal in public stories. eds. H. Hornmoen, B. K. Fonn, N. Hyde-Clarke, Y. Benestad, and Y. B. Hågvar (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget), 165–185.

Fontenla-Pedreira, J., Arce-Chaves, L., and Máiz-Bar, C. (2023). Conversation and digital sentiment recorded during the first round of the 2022 Costa Rican electoral. Rev. Comun. 22, 127–151. doi: 10.26441/RC22.1-2023-3051

Goldberg, Y. (2017). Neural network methods for natural language processing. Synth. Lect. Hum. Lang. Technol. 10, 1–31. doi: 10.2200/S00762ED1V01Y201703HLT037

González-Bailón, S., and Paltoglou, G. (2015). Signals of public opinion in online communication: a comparison of methods and data sources. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 659, 95–107. doi: 10.1177/0002716215569192

Gorostiza-Cerviño, A., Serna-Ortega, A., Moreno-Cabanillas, A., and Castillo-Esparcia, A. (2023). Navigating the digital sphere: exploring websites, social media, and representation costs—a European Union case study. Sociol. Sci. 12:616. doi: 10.3390/socsci12110616

Grimmer, J., and Stewart, B. M. (2013). Text as data: the promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Polit. Anal. 21, 267–297. doi: 10.1093/pan/mps028

Hanegraaff, M., and Berkhout, J. (2018). More business as usual? Explaining business bias across issues and institutions in the European Union. J. Eur. Public Policy. 26, 843–862. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2018.1492006

Harris, P., and McGrath, C. (2012). Political marketing and lobbying: a neglected perspective and research agenda. J. Political Mark. 11, 75–94. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2012.642745

Haselmayer, M., and Jenny, M. (2017). Sentiment analysis of political communication: combining a dictionary approach with crowdcoding. Qual. Quant. 51, 2623–2646. doi: 10.1007/s11135-016-0412-4

Haug, M., and Koppang, H. (1997). Lobbying and public relations in a European context. Public Relat. Rev. 23, 233–247. doi: 10.1016/S0363-8111(97)90034-5