- Department of Sociology, The University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

The concept of passport power has become an increasingly relevant measure of a country’s soft power and global standing. Existing scholarship usually ranks countries’ passport power by the number of visa-free travel destinations its passport holders can enjoy. Despite being informative, such an understanding is overly generic, which may not necessarily fully assess the passport power itself. The research question is studying how many travel destinations accepting and denying visa-free access to China belong to Western powers and advanced economies. Such an assessment enriches existing understanding of China’s passport power. For methodology, this research examines the distribution of 77 destinations offering visa-free access to Singaporean, Japanese, South Korean, and Chinese passport holders. It further explores the distribution of 102 destinations that permit visa-free entry to Singaporean, Japanese, and South Korean citizens but not to Chinese nationals. The comparative analysis approach further allows our evaluation of the existing passport power gap between China and its neighbouring counterparts. The findings indicate that most major global powers (especially major Western powers) and advanced economies (such as high-income and upper-middle-income countries or territories), are inclined to establish visa-free agreements with Singapore, Japan, and South Korea. However, China’s passport power lags behind its regional counterparts. Consequently, compared to its neighbouring countries with strong passport power, such as Singapore, Japan, and South Korea, China’s passport power still has significant room for improvement. This research concludes that the lack of democratic values, the concerning human rights issues, the western scepticism of China’s threats and regional assertiveness, and the rising United States-China tensions across different fields (geopolitics, technology, etc.) all contribute to the relatively weak passport power of China, compared to that of its regional counterparts.

1 Introduction

Passport power and relations are significantly underexplored in existing scholarship. However, with the continual rise of globalisation and international trade and exchange, passport power and relations deserve more discussion and investigation. One of the reasons, as highlighted in this research paper, why addressing passport power is timely and relevant is because it represents a part of soft power. In the dynamics of global competition and imbalance of powers, examining and comparing countries’ soft power are increasingly important and extensively researched. However, the examination and comparative analysis of countries’ passport power remain significantly underexplored.

Among the discussion about global powers and competition, the discourse on China’s soft power and, therefore, passport power always gain significant traction regionally and globally. Thus, in this research paper, I would present a literature review to briefly articulate the relationship between passport and soft power, discuss passport power relations, and address the relationship between passport power and global travels. Then, I would justify how this research paper relies on analysing existing data from the Henley Passport Index database to comparative analyse China’s passport power in relation to that of the regional counterparts that dominate global passport powers, namely Singapore, Japan and South Korea. The Henley Passport Index methodology ranks passports globally, where the ranking is based on exclusive data from the International Air Transport Association (IATA) and research conducted by Henley and Partners research team (Henley and Partners, 2024).

I would further identify existing research gap in passport power: the Henley Passport Index ranks passport powers based on the numbers of visa-free travel destinations. Despite being informative, such an understanding fails to extensively or comprehensively present the nuances of passport power and relations. In response, I would study how many travel destinations giving Singaporean, Japanese, South Korean and Chinese passport holders visa-free access are Western powers and affluent economies. In addition, I would study how many travel destinations giving Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean passport holders visa-free access while denying Chinese passport holders the same privilege are Western powers and affluent economies. Such an extensive comparative analysis helps enrich existing understanding of China’s passport power and China’s passport relations with the West or higher-income economies.

I would further engage in discussion to justify why Singapore, Japan and South Korea enjoy world-leading passport powers, while China’s passport power, despite rising rapidly, has yet to catch the heights of its regional counterparts. Such discussion clarifies the passport power gaps between China and its frontier regional counterparts.

In specific, in this research article, I examine the distribution of a total of 77 travel destinations that offer visa-free access to Singaporean, Japanese, South Korean, and Chinese passport holders (see Table 1 in the following). I then explore the distribution of a total of 102 destinations that provide visa-free access to Singaporean, Japanese, and South Korean passport holders but deny it to Chinese passport holders (see Table 2 in the following).

Table 1. Among 180 travel destinations that give Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean citizens visa-free access, which of them deliver visa-free to Chinese nationals too?

Table 2. Among 180 travel destinations that give Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean citizens visa-free access, which of them deny visa-free to Chinese nationals?

This research shares broader implications beyond global movement to enrich the understanding of international relations and the global political economy by examining China’s passport power—a tangible yet understudied dimension of state influence—in comparative perspective. By systematically analysing visa-free access disparities between China and its regional peers (Singapore, Japan, and South Korea), the research illustrates how passport mobility intersects with geopolitical alliances, economic interdependence, and perceptions of state legitimacy (Avdan, 2013; Pereira, 2013). In a contemporary epoch focusing on strategic competition and shifting migration regimes, the findings contribute to debates about the hierarchies of global mobility, the limits of Chinese soft power, and the role of non-Western states in reshaping border governance norms. The research thus moves beyond simply counting the number of visa-free access travel destinations Chinese passport holders or their neighbouring counterparts can enjoy to reveal how passport power reflects, and potentially reinforces, asymmetries in the international system—a pressing concern given China’s dual status as an economic powerhouse and a politically contested actor (Amighini, 2018).

2 Literature review

2.1 Passport power and soft power

In recent decades, China has joined the United States as a world’s leading economy. The United States, along with some major Western powers, is known as a state dominating hard and soft powers. Here this research paper refers major Western powers to major international players from the West, which are Western European countries, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Unlike the United States, while China has demonstrated its rapid development of hard power (such as military advancement and rapid economic and technological development), international, including Western, narratives remain sceptical about its soft power (Liang and Yang, 2019; Pan and Mishra, 2018). This research article examines one of the underexplored but relevant and topical aspects of China’s soft power—its passport power. Passport power refers to a state’s capacity to enable its citizens’ global mobility through visa-free or visa-on-arrival access, shaped by geopolitical relationships, economic competence and partnerships, and perceptions of state credibility (Pereira, 2013). It symbolises a nation’s international standing, acting as both a measure of soft power and a tool for reinforcing hierarchies in global politics and economic interdependence.

Existing scholarship (such as Gill and Huang, 2006; Nye, 2023; Repnikova, 2022) examines the opportunities and barriers for China to promote its soft power, specifically analysing how China has been committed to improve its soft power. Nye, for example, evaluates how cultural and political values and foreign policies can affect soft power. In addition, while Gill and Huang (2006) argue that China’s rising soft power, since the 1990s, has been conducive to its foreign policy outcomes, the country’s legitimacy concerns, such as its human rights concerns, nationalism ideological differences from the West are all barriers to the growth of its soft power. Repnikova (2022) further addresses the expansiveness of China’s soft power. Here China has instrumentalised on media platforms to assert global political influence, as media plays a significant role in shaping public opinion and perception. Repnikova’s argument is in alignment with my later discussion on how China’s increasingly regional assertiveness might be concerning among the West, leading to the lack of Western powers giving visa-free access to China. Here, existing scholarship primarily focuses on examining China’s soft power, where its passport power is rarely discussed. This research would like to close such a research gap by evaluating China’s passport power, followed by engaging in the discourse on how Western powers and richer economies denying visa-free access to China but not to its regional counterparts indicates the aforementioned existing scholarship on China’s (barriers to) soft power development.

In global movement and tourism, having more powerful passports usually comes with more opportunities than restrictions. Advanced countries are capitalising their more desirable passports by allowing competitive, skilled and especially rich individuals overseas to earn their passports through substantial investment in the host economies. Citizenship by investment, for example, is a fast-growing practice nowadays that suggests the popularity and preferability of enjoying a strong passport power (Surak, 2024). Earning a passport with strong power notably facilitates our international mobilisation and freedom (Freisleben, 2019). The discussion of the citizenship by investment schemes highlights the market values of more powerful passports, in order to demonstrate the preference and benefits of holding a stronger passport in international travels. This circumstance reflects the power of passports issued by globally respected and advanced countries or territories.

There are several ways to measure passport power. Recent studies refer to the Henley Passport Index, which ranks passports according to the number of travel destinations their holders can visit without a prior visa (e.g., Fidow, 2023; Okagbue et al., 2021). This index is regularly updated to reflect the constantly changing landscape of international travel regulations. The Henley Passport Index, produced by the consultancy Henley and Partners, is widely regarded as one of the most authoritative and frequently cited benchmarks for measuring global passport power (Whyte, 2008). The index is regularly referenced by global media outlets, governments, and individuals tracking mobility freedom and the relative strength of national passports.

The Henley Passport Index, initiated and launched by Henley and Partners in collaboration with the International Air Transport Association, offers an insightful look into the accessibility of the world based on the visa restrictions of each country. To date, the Index presents a list of 199 passports and 227 travel destinations, reflecting the current state of global movement and migration trends. It is noteworthy that not all travel destinations recorded and calculated by this Index are sovereign states. For example, Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan are considered as travel destinations, despite these territories not having (globally-recognised) sovereignty (Denny, 2015).

By assessing the number of travel destinations passport holders can enter without a visa, the Henley Passport Index becomes a vital tool for understanding travel rights. It highlights the mobility power of countries and provides an invaluable resource not only for individuals and global travellers but also for governments and international organisations to gauge the international standing of passports. An advantage of assessing the Index is its availability to compare multiple passports’ visa-free travel destination access simultaneously. Such a function enables the comparison between multiple passport powers, in a way to examine the (in)convenience of China’s passport, compared to other Asian counterparts.

The Index ranks passports by the total number of accessible travel destinations, painting a vivid picture of global travel freedom. Passports from countries at the top of the ranking allow entry to a vast majority of the world, often exceeding 180 travel destinations. These passports typically hail from economically and diplomatically stable nations with strong international alliances (Pereira, 2013). The upper ranks of the Index are frequently dominated by Singapore, Japan and South Korea, reflecting their compelling diplomatic relations and agreements that have opened many borders to their citizens.

However, the Henley Passport Index also brings to light the substantial mobility gap between countries. Passports at the lower end of the spectrum might be offered visa-free access to fewer than 40 destinations, unveiling notable disparities in freedom of movement across different regions (Gulddal and Payne, 2017). This divide not only affects tourism and overseas work and studies but has profound implications about global inequality and economic opportunity.

2.2 Passport power disparities

Harpaz (2021) argues that rich and major Western democratic countries, such as the United States, Canada and Germany, may visit between 180 and 190 visa-free travel destinations, while citizens of Russia, Turkey or Colombia have visa-free access to some 110–130 destinations. Egyptians, Iranians and Indians may enter only between 40 and 60 destinations without holding a visa. The different levels of global travel freedom perpetuate a global hierarchy.

When understanding the power of a passport, factors such as ethnicity and class come to interact and intersect, producing inequalities and gaps between mobility (of favourable populations) and immobility (of unprivileged populations) (Keshavarz, 2015). Passports can reflect global mobility inequalities. Under the unequal power relations of the existing social order, countries with less valuable passports are often non-white or non-Western beyond the Global North (ibid). While Singapore, Japan and South Korea are non-white and non-Western countries, they are among the most advanced countries from the Global North who exhibit notable democratic values. Therefore, these three Asian countries have held among the most powerful passports globally.

In essence, the Henley Passport Index is not just a ranking but a mirror to the complex dynamics of international relations and human mobility. It highlights the power of passports, the freedom they grant, and the doors they open across the globe. The Index (as will be discussed later on) employs as standardised methodology as possible to evaluate which countries or territories enjoy the strongest—meaning the most convenient—passport power. Using available data from the Henley Passport Index for data analysis paths the way for this research to evaluate global issues beyond international movements, such as politically and culturally diplomatic and economic relations which are especially highlighted in the conclusion section.

Per the latest Henley Passport Index 2024 data, Singapore and Japan are tied with France, Germany, Italy, and Spain at the top of the passport power rankings. South Korea is tied with Finland, the Netherlands, and Sweden for the second place in the global rankings. Here, the passports of Singapore, Japan, and South Korea lead Asia, standing at the very top of this ranking list. Holders of Singaporean and Japanese passports can enjoy visa-free access to 194 out of the 227 travel destinations accounted for globally. South Korea stands shoulder-to-shoulder with them, with access to 193 visa-free travel destinations, just one fewer than its Singaporean and Japanese peers. Notably, mainland China ranks 62nd globally on the list of the most powerful passports, with access to 88 visa-free travel destinations. Within East and Southeast Asia, mainland China ranks behind Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Brunei, Macao and Taiwan.

2.3 China’s passport power and tourism

The concept of passport power has become an increasingly relevant and important metric of a country’s standing on the world stage. For decades, the Chinese passport languished at the lower end of global rankings in terms of travel freedom. The Henley Passport Index only makes the recent decade of rankings publicly available. From the available data, we can see that China’s passport power ranked 87th in 2016 (with 50 visa-free travel destinations). Its passport power rose to 67th in 2020 (with 75 visa-free travel destinations). It further climbed to 62nd in 2024 (with 85 visa-free travel destinations). This suggests that today’s passport power of China is much stronger than its power in the past. In the late 20th century, China’s international influence was limited, and its citizens faced stringent travel restrictions. Before China’s implementation of the Open Door Policy in 1978 to allow foreign businesses to invest in the country, the prospect of travelling abroad was a distant dream for ample average Chinese citizens (Naughton, 2007). Since 1978, as China’s economy has surged, the Chinese Government has begun gradually easing international travel restrictions. Since China’s implementation of the open-door policy, outbound tourism development has experienced rapid growth. China has become an important inbound international tourism market too, especially for countries in the Asia-Pacific region (Lim and Wang, 2008). The country’s accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001 further integrated it into the global economy, necessitating and encouraging cross-border travel for both business and tourism. Since joining the WTO, China has increasingly opened major service areas to foreign competition, including travel and tourism (Wu, 2011).

Chinese outbound tourism has been managed and regulated by the Approved Destination Status (ADS) system. The ADS system is based on bilateral tourism agreements between China and overseas destinations. With Chinese citizens’ rapidly growing personal disposable income over recent decades, the rise in purchasing power has been a strong impetus for Chinese outbound travellers (Lim and Wang, 2008). Consequently, many Chinese citizens have applied for passports for overseas travel purposes. With more overseas travel destinations forming bilateral travel agreements with China, such as granting visa-free access, Chinese citizens are even more incentivised to travel internationally (ibid). This increasing number of visa-free travel privileges indicates that China’s passport power is growing, reflecting the rise of economic competitiveness of both the country and its citizens.

China’s meteoric economic rise in the 21st century has been a crucial factor in enhancing the power of its passport. The transformation from a predominantly agricultural society to an industrial powerhouse has resulted in an explosive growth in the middle class, fostering a new wave of outbound tourism. Given China’s rapid economic development and emergence of middle-class consumers, today’s Chinese travellers are often deemed luxurious and high-end consumers overseas. Their travel and shopping pattern and preference have been driven by brand consciousness, social comparison and innovative fashion (Hung et al., 2021).

International literature published as early as in the 2000s already discussed how China became an emerging and regional technological power (U. S. Government Print Office, 2004). In the most recent decade, China has proven that it has been transitioning into a technologically innovative powerhouse. Such an advancement has helped China boost its global influence, especially from an economic aspect (Chhabra et al., 2020). In international tourism, Chinese tourists have become a ubiquitous presence across the globe, and their consumption power, as indicated above, is courted by many countries, resulting in a growth of bilateral and multilateral agreements that often include visa liberalisation.

3 Methodology

While focusing on the measurement of China’s passport power, this research article does not investigate the Chinese passport power individually, but it comparatively analyses the Chinese passport power relative to those of the Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean counterparts. In the above section, we already discuss that (1) China’s passport power has been growing swiftly and (2) its neighbouring regional counterparts, such as Singapore, Japan and South Korea, hold the world’s most powerful passports. By comparatively analysing China’s passport power relative to that of the regional counterparts, we are able to understand the existing gap in passport power between China and its regional counterparts. Such an understanding helps indicate how much less favourable China’s passport power and, thus, soft power are compared to those of its regional counterparts with world-leading passport power. More importantly, this research helps inform the key barriers to improving China’s passport power to a world-class level which, in turn, suggests areas that China needs to continue to make progress to further enhance its passport power and, thus, soft power over the long term.

It is noteworthy that one of the benefits of using the Henley Passport Power Index is that the database allows users to directly compare the lists of (denial of) visa-free travel destinations of up to four passport holders. Therefore, without the need of using any external statistical software package for data analysis, this research simply navigates the database to compare which countries or territories offer or deny visa-free access to Singaporean, Japanese, South Korean and Chinese passport holders.

This research utilises data derived from the Henley Passport Index to quantify passport power, primarily focusing on its “visa-free score.” This score represents the total number of destinations a specific passport holder can access without requiring a traditional visa obtained in advance. Crucially, the methodology assigns a score of 1 not only for completely visa-free access but also for destinations offering a visa on arrival (VOA) or an electronic travel authority (ETA), provided these do not necessitate pre-departure government approval. Conversely, destinations requiring a standard visa application or even an electronic visa (e-Visa) that must be approved before travelling are assigned a score of 0, as are any VOA schemes that mandate pre-departure clearance. The total visa-free score for any given passport is simply the sum of destinations where access is granted under these “score = 1” conditions (Henley and Partners, 2024).

It is important to acknowledge the specific conditions and assumptions underpinning this data, ensuring consistent comparison. The Henley Passport Index methodology presumes the traveller holds a valid, “normal” adult passport (not diplomatic or temporary) and is a citizen of the issuing country travelling alone for a short tourist or business stay (typically a few days to several months, not transit). Furthermore, it assumes the traveller meets standard entry requirements such as proof of sufficient funds or necessary vaccinations, arrives and departs from the same major airport, and does not face complex entry barriers requiring special government letters. These standardised parameters allow for a direct comparison of visa-access privileges afforded by different passports based solely on the pre-travel requirements imposed by destination countries (Henley and Partners, 2024).

4 Findings

4.1 Travel destinations providing and/or denying visa-free access to China

Table 1 shows that there are 77 countries or territories that give visa-free access to Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean nationals and also to Chinese nationals. Alternatively, among travel destinations giving visa-free access to Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean nationals, the majority of them deny visa-free access to Chinese nationals. Table 2 lists out all 102 countries or territories that deny visa-free access to Chinese nationals. On the list, we can find a lot of Western powers not only from Western Europe, but also from the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, for example. It is noteworthy that the major focus of Table 2 is not about which 102 countries or territories deny visa-free access to Chinese nationals, but rather how as many as 102 travel destinations all decide to give visa-free access to Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean citizens but not to Chinese nationals. We should apply a comparative approach when interpreting the list. To these 102 travel destinations, Singapore, Japan and South Korea seemingly are more favourable countries when forming visa-free travel agreements. However, mainland China is relatively less favourable, that as many as 102 travel destinations require the visa application process for entry. While passport power is not the sole factor to measure soft power, passport power is a prominent indicator that suggests how influential a country or territory is on the global stage. In such an understanding, mainland China is apparently less favourable than its neighbouring advanced economies, namely Singapore, Japan and South Korea.

Existing scholarship argues that relations between states in the post-Cold War period have been shaped by geoeconomics. Geoeconomics is an interdisciplinary analysis that includes geopolitical factors and economic intelligence to examine contemporary dynamics of power rivalries (Csurgai, 2018; Wigell et al., 2019). This research paper, in response, primarily studies the geopolitical power and economic strength of countries or territories that give or deny visa-access to China. In the following sections, this research paper studies how (1) Western powers all deny visa-free to Chinese but not Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean passport holders, and (2) how rich states are more likely to deny visa-free access to Chinese rather than Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean passport holders.

4.2 Western powers all deny visa-free to Chinese passport holders

The Chinese passport power may serve as an indication of the increasing political and diplomatic tensions between China and Western powers. Major Western powers all offer visa-free access to Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean citizens, but none deliver visa-free access to Chinese citizens. Table 3 is a list of all 24 Western European countries that all deny visa-free access to China. The list includes major Western powers within the region, namely the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy and Spain.

Table 3. Countries/territories from Western Europe that deny visa-free access to Chinese citizens but not Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean citizens.

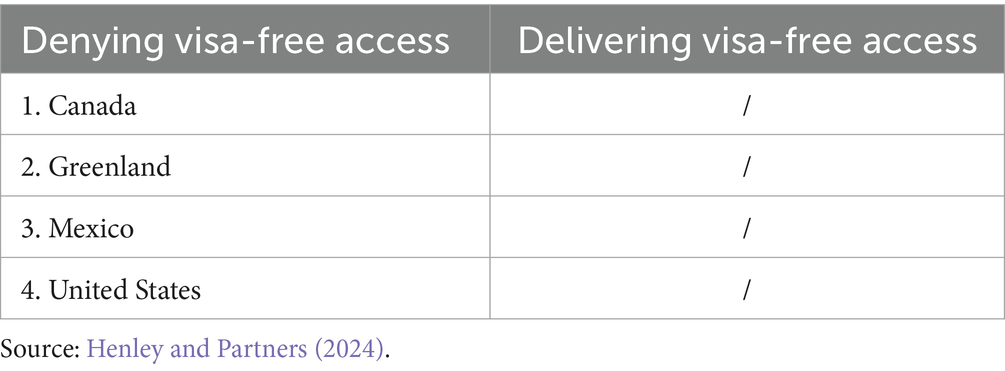

Like Western Europe, Table 4 shows that all countries from North America deny visa-free access to China but not to Singapore, Japan and South Korea. North America is another region that is dominated by major Western powers, led by the United States and Canada. Western powers like the United States, Canada and Greenland, in addition to Spanish-speaking Mexico, all require Chinese nationals to hold a visa for entry. However, Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean passport holders are allowed for visa-free entry.

Table 4. Countries/territories from North America that deny visa-free access to Chinese citizens but not Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean citizens.

4.3 Non-western powers may or may not deny visa-free access to Chinese passport holders

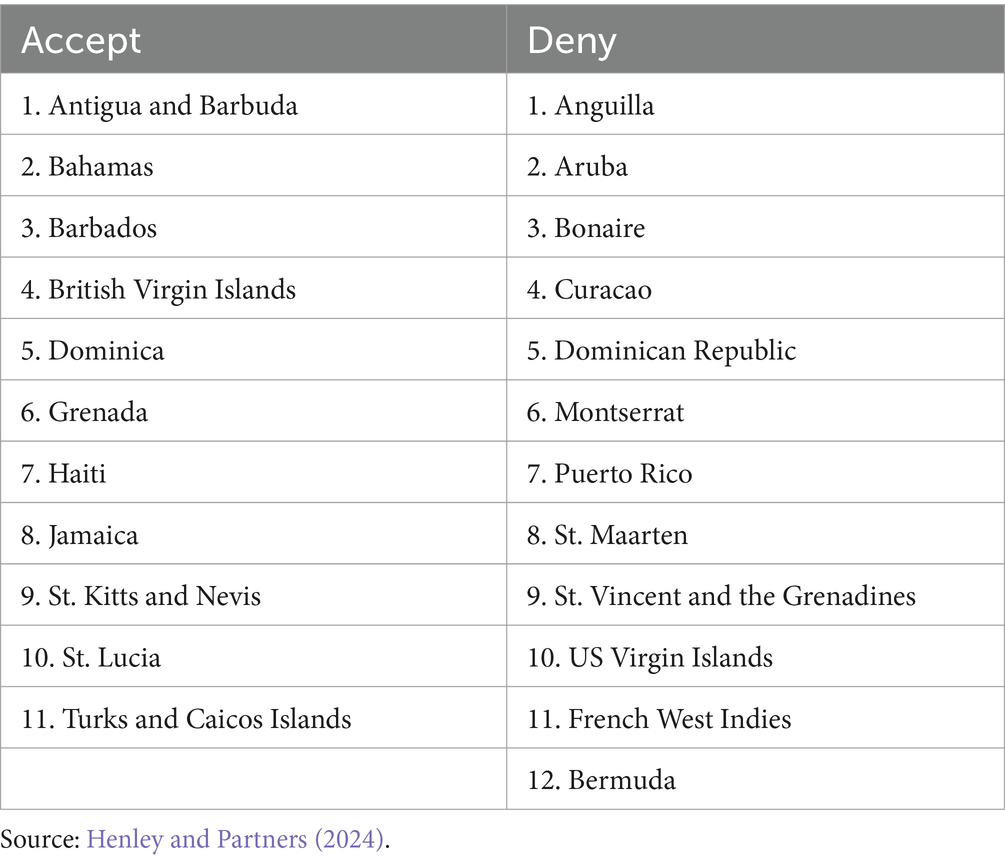

Moving on to the Caribbean, Table 5 shows that the amounts of countries or territories offering and denying visa-free access to China are evenly distributed. Among territories that deliver visa-free access to China, there are British overseas territories like British Virgin Islands and Turks and Caicos Islands. There are also commonwealth countries or territories like Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas and Barbados. While these travel destinations have ties with Western powers, especially the United Kingdom, they are not generally regarded as major players of Western powers. There can be many reasons behind whether these territories deliver visa-free access to China. These include whether these economies rely on inbound tourism and how generously they welcome foreign tourists. Therefore, whether these island countries and territories deliver visa-free access to China may not necessarily be based on geopolitical factors alone. Ostensibly, it may be more feasible for these Caribbean territories to deliver visa-free access to China in the future than countries from Western Europe and North America, given how the relations between China and major Western powers have increasingly been polarised.

Table 5. Countries/territories from the Caribbean that accept or deny visa-free access to Chinese citizens.

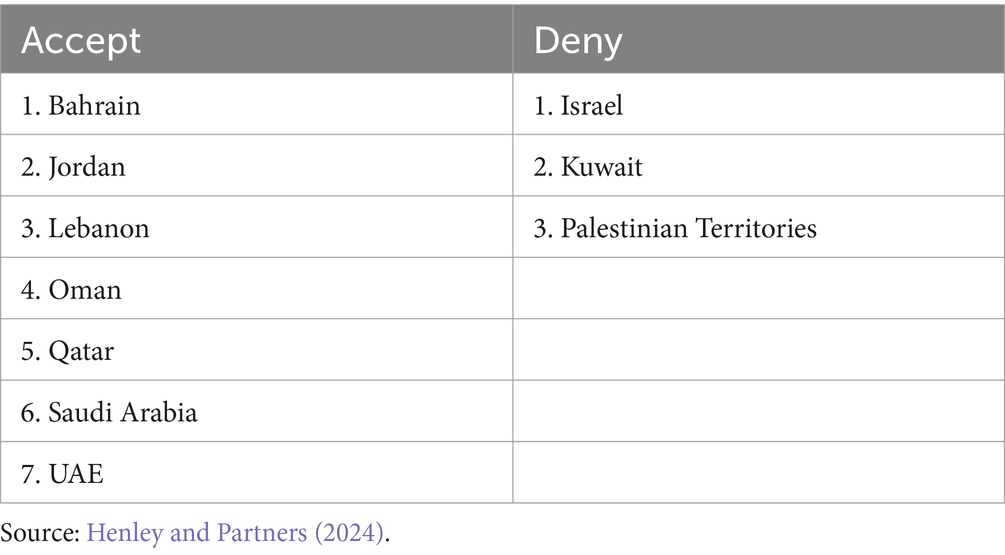

Tables 6, 7 show that China has better relationships with Africa and the Middle East than with Western powers. The majority of African and Middle Eastern countries or territories accept visa-free access for Chinese passport holders. As of writing this journal article, it is noteworthy that Kenya, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Rwanda, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe are Commonwealth member states. However, these Commonwealth member states are commonly not regarded as Western powers, despite sharing remote ties of historical and cultural legacy with the United Kingdom. As China continues to strengthen its belt-and-road initiative (BRI) influence since September 2013, very likely more African and Middle Eastern nations will reinforce their ties with China. The prospective expansion of economic ties between China and each of Africa and the Middle East may trigger more countries to give visa-free access to Chinese passport holders in the long term.

Table 6. Countries/territories from Africa that accept or deny visa-free access to Chinese citizens.

Table 7. Countries/territories from the middle east that accept or deny visa-free access to Chinese citizens.

4.4 Richer states deny visa-free to Chinese passport holders

To further evaluate China’s actual passport power, this section is going to measure the economic competitiveness of travel destinations either giving and denying visa-free access to China. The preceding section explains that Western powers are very unlikely to offer visa-free access to China. As Western powers are considered among the richest globally, China failing to obtain visa-free access from Western powers may imply richer countries or territories, in general, have the disposition to deny visa-free access to China. Table 8 lists out all countries or territories that deny visa-free access to China. In total, there are 44 travel destinations denying visa-free access to China that belong to high-income territories. This list includes all 24 Western European countries, in addition to Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. Also, except Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan, there are a few high-income economies that are non-Western powers and deny visa-free access to China. These economies include Kuwait from the Middle East and Trinidad and Tobago from the Caribbean. Apparently, most countries and territories belonging to high-income economies that deny visa-free access to China are major Western powers. With very few affluent non-Western powers denying visa-free access to China, such an observation may indicate that China has been fairly successful on building its economic and cultural influence among the developing, non-Western regions.

Table 8. High-income countries/territories deny visa-free access to Chinese citizens but Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean citizens.

In addition to 44 high-income economies denying visa-free access to China, there are 34 upper-middle-income economies that reject the provision of visa-free access to China too. While this list contains seven European countries, they are not linked to Western Europe (see Table 9). Also, the majority of economies on the list do not belong to Western powers, such as Brazil, Chile and Colombia. In addition to non-Western Europe, most economies on the list are from South America. Among these upper-middle-income countries or territories, we are able to discover some big names, despite not being associated with the West. These big names include Brazil from South America, Mexico from North/Central America, South Africa from Africa or Turkey between the borders of Asia and Europe. These four countries are among the largest economies globally by gross domestic product. Despite not being associated with Western powers, China failing to secure visa-free access from Brazil, Mexico, South Africa and Turkey may harm its passport power and, in general, soft power. If China wants to improve its passport power in the long term, obtaining visa-free access from these emerging economies may be conducive to the establishment of China’s global presence.

Table 9. Upper-middle-income countries/territories deny visa-free access to Chinese citizens but Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean citizens.

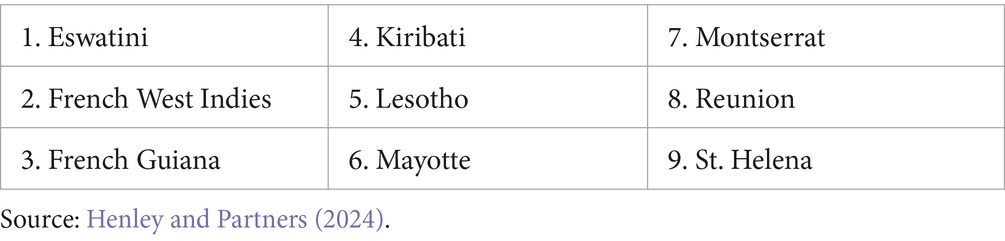

Compared to high-income and upper-middle-income economies, there are fewer countries or territories denying visa-free access to China that belong to lower-middle-income or low-income countries or territories. Table 10 shows that there are only 15 travel destinations denying visa-free access to China that are categorised as lower-middle-income countries or territories. These countries or territories are geographically distributed across the globe. Some of them are island countries or territories. Not only are these travel destinations poor, they are less influential on the global stage than countries or territories discussed above. These countries or territories denying visa-free access to China may not alter the narrative about China’s passport power much.

Table 10. Lower-middle-income countries/territories deny visa-free access to Chinese citizens but Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean citizens.

Likewise, Table 11 indicates that there are nine countries or territories denying visa-free access to China that are low-income economies. These countries or territories are mostly located in Africa. These countries or territories have least economic and geopolitical impacts globally. Existing scholarship suggests that less and least developed economies are smaller players in international economy in both their contributions and bargaining power in terms of trade and finance (Sarpong, 2024). Compared to upper-middle-income and high-income economies, explicitly there are far fewer countries or territories denying visa-free access to China that belong to poorer states. Such findings support the claim that richer countries or territories have the disposition of denying visa-free access to China, while poorer countries or territories are more likely to offer China visa-free access.

Table 11. Low-income countries/territories deny visa-free access to Chinese citizens but Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean citizens.

5 Discussion

Here above findings suggest that, relative to Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean passport holders, those holding a Chinese passport are subject to significant travel freedom restrictions. These travel freedom restrictions are particularly applicable when Chinese passport holders intend to travel to more affluent and Western countries or territories. Unlike their Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean counterparts, they most likely have to apply for a visa in order to travel to richer and more westernised countries and territories. However, if they want to visit relatively economically weak and geopolitically negligible countries and territories, Chinese passport holders’ travel freedom may not be affected much.

Again, such a circumstance demonstrates there is still a long way for China to go before it can catch up Singapore, Japan and South Korea as having a powerful passport, exhibiting impactful cultural influence and earning cultural acceptance. Compared to the world’s best passports, a Chinese passport is far less valuable. This implies that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has to continue to improve its soft power overseas in order to bring more travel convenience to its local citizens in the long term.

From the standpoint of passport power, Singapore, Japan and South Korea are more favourable diplomatic partners with Western powers than China. Such a circumstance contributes to the understanding of why Singaporean, Japanese and South Korean passport holders are preferable travellers in Western powers, however, Chinese passport holders are often deemed secondary or less favoured.

In the 21st century, we are witnessing the transition of our global and regional order. In the long term, such a transition may alter the rankings of passport power, where non-Western powers, other than Singapore, Japan and South Korea, may 1 day be able to dominate the global passport powers. For example, in recent decades, the rapid rise of China, the resurgence of Russia under Vladimir Putin, and the economic emergence of countries like India and Brazil have begun to change the balance of global power. Moreover, the internal challenges facing Western nations, from economic crises to the rise of populism and the questioning of liberal democratic values, have tested the cohesion and resolve of the West (Roberts, 2019). In the face of such challenges, the Western powers have had to redefine their role on the world stage. The United States, while still the preeminent military power, has had to encounter the complexities of a multipolar world. The European Union (EU), representing a unique experiment in supranational governance, has had to contend with Brexit (i.e., the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU; on February 1, 2020) and the tensions between national sovereignty and collective action (Armstrong, 2017).

The cultural aspect of Western power has also evolved. The proliferation of American media and the English language has contributed to a form of soft power that extends beyond the reach of military might or economic prowess (Mirrlees, 2006). The ideals of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law, often associated with the West, continue to resonate around the world, albeit contested by alternative models of governance and cultural norms.

Technological influence is another major factor that affects global power rankings. The technological battlefield is one of the leading fields that determines today’s global power dynamics. In the fields of technology and innovation, the Western powers have remained at the forefront, with Silicon Valley being symbolised and recognised as the pioneer that drives progress. Yet, this sector, too, is witnessing the rise of competitors from Asia and other parts of the world, challenging the West’s dominance in shaping the future of technology (Khan et al., 2022). The Western powers of the 21st century, therefore, are not just a group of countries with shared historical and cultural ties. They represent an idea, a set of values, and a collection of institutions that are in a constant state of flux.

Existing scholarship argues that, despite its decline, our world, to date, remains Western-centric (e.g., Chu and Zheng, 2020). Western powers generally refer to a group of countries with shared democratic values, economic practices, and often, historical ties to Western Europe. The definition can vary depending on the context, but conventionally, major players among the Western powers include the United States, Canada, Western European countries, Australia and New Zealand. These countries typically share commitments to democratic governance, human rights, capitalist economies, and participation in international organisations like NATO and the EU. They often coordinate their foreign policy and defence agendas to reflect shared interests and values.

Additional scholarship presents Western scepticism about China’s increasing geopolitical assertiveness—China more proactively pursues its interests and seeks to exert greater influence within different geographical regions, especially across Southeast Asia—and the CCP’s ambition of global dominance (Bickers, 2017; Boon, 2017; Simons, 2022). These may contribute to the explanation of why no Western powers are willing to give visa-free access to those holding a Chinese passport.

Many regional polls conducted during the global pandemic had shown that Western European’s perception of China had worsened during the course. With Western powers resisting purported China’s media manipulation, technological surveillance and more, there is no sign to indicate that Western powers will change their perception of China, and especially the CCP, in the short term (Brandt, 2021). While many affluent Chinese households still like to visit Western Europe, they must have to apply for a visa for entry.

While passport power of China has been rising, there remains barriers to the country’s maximisation of its passport power growth. The late 20th century was characterised by increasing economic integration between China and Western powers. Since the aforementioned implementation of China’s Open Door policy in December 1978, China has gradually been opening up its economy to foreign investment and international trade. Such a foreign policy has helped China reach unprecedented economic growth and the development of deep trade relations with Western countries over the past decades. Despite these areas of cooperation, the 21st century has seen growing strategic rivalry and tension between China and Western powers, particularly the United States. The West has increasingly viewed China’s rising economic and military capabilities as a challenge to the established international order. Issues such as trade imbalances, intellectual property theft, and China’s assertive foreign policy, especially in the South China Sea, have led to friction. The situation has been further complicated by concerns over human rights, with Western criticism of China’s policies in Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong. The West has also been wary of China’s technological advancements and its ambitions to set global standards in emerging technologies through initiatives like the “Made in China 2025” industrial policy, a national strategic plan and industrial policy of the CCP to further develop the manufacturing sector of China (Li, 2018).

Western powers’ denial of visa-free access to China is an indication of China’s increasing and complex geopolitical and else tensions with major Western powers. Here Western powers continue to dominate the ownership of soft power on the global stage. China’s inability to secure visa-free access from any major Western powers may be deemed a weakness of China’s passport power. Regardless of whether China will choose to develop more positive diplomatic relationships with Western powers or decide to pritorise building ties with BRICS bloc member states (i.e., Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and other major emerging economies, China’s passport power will plausibly improve insofar as the country is able to earn more visa-free access from crucial economic and geopolitical players.

6 Conclusion

China’s rise as a global power is an event of immense historical significance, reshaping the geopolitical order that has existed since the end of the World War II. As China’s economic might has grown, so too has its desire to expand its influence in other spheres, such as politics, culture, and security. One of the more subtle, yet potent, instruments in its diplomatic arsenal is the strength of its passport.

The ability of Chinese citizens to travel visa-free to various countries is not just a matter of convenience; it is a diplomatic achievement that reflects China’s expanding relationships and its attractiveness as a partner on the world stage. The process of enhancing the power of a passport generally involves a series of diplomatic negotiations. Each visa exemption agreement is a complex dance of mutual interest, trust, and strategic importance. When a country grants visa-free access to Chinese passport holders, it is often seen as a gesture of goodwill, a sign of a strengthening partnership, and sometimes, an acknowledgement of China’s growing global status. These agreements are rarely one-sided; they usually come hand-in-hand with reciprocal arrangements that benefit both parties, creating a web of interconnected travel freedoms.

The power of a passport can be seen as a mirror that reflects the internal dynamics of a nation. For China, the strength of its passport can signify to its citizens the effectiveness of its governance and its standing in the world. It is a tangible symbol of national pride and progress. Conversely, any limitations on the Chinese passport can be a source of frustration and a reminder of the boundaries of China’s influence.

For China, enhancing its passport’s power is a clear objective aligning with its broader goal of becoming a preeminent global power, especially by exhibiting more soft power globally. Each step towards visa-free access in another country represents both a diplomatic victory and a strategic advantage. China’s passport power plays a dual role in national pride and diplomacy. It reflects China growing influence; and it also serves as a building block in the country’s global strategy. Currently, while China ranks 62nd globally in terms of passport power, this research finds that most geopolitically and culturally dominant states (such as major Western powers) and advanced economies (such as high-income and upper-middle-income countries or territories) have been keen to establish visa-free agreements with Singapore, Japan, and South Korea, but not with China. Therefore, compared to its neighbouring countries with world-class passport power (i.e., Singapore, Japan, and South Korea), China’s passport power still has notable room for improvement.

As discussed in this research paper, the lack of democratic values, the concerning human rights issues, the western scepticism of China’s threats and China’s increasingly assertive regional diplomacy, and the rising United States-China tensions across different fields (geopolitics, technology, etc.) all contribute to the relatively weak passport power of China, compared to that of its regional counterparts. Also, as mentioned, China’s passport power has been growing rapidly over the past decade, as a result of its growing economic and geopolitical influence on the global stage. Therefore, this research paper is not designed to discredit China’s rise in passport power, but simply to note that, as a status quo, there remains a gap in passport power between China and world-leading countries, such as Singapore, Japan and South Korea.

There is no sign that the Western concerns about China’s lack of democratic and westernised human rights values will be lessened in the foreseeable future. Western states may view liberalising visa policies with China as risky due to concerns about national security, economic competition, and ideological differences. These apprehensions are heightened by ongoing issues related to human rights (in the contexts of Tibet, Hong Kong and Taiwan, for example), intellectual property, and China’s extensive surveillance capabilities. Unlike Singapore, Japan, and South Korea, which maintain close security and economic ties with Western powers, China’s relationships with these states often involve strategic competition. Cultural diplomacy, as a facet of soft power, plays a subtle yet significant role here. Western nations might see visa-free arrangements as indicators of trust and cultural alignment, elements they perceive as lacking in their interactions with China. Restrictive visa regimes could therefore signify scepticism regarding China’s intentions in fostering international exchanges (Grieger, 2016).

Despite the ideological differences between China and major Western countries, the key factor of China’s continual rapid rise in passport power is its growing economic and geopolitical influence. As China continues to expand its BRI partnerships with global partners, especially those in the developing or emerging markets, very likely that China’s passport power will keep rising over time.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Amighini, A. (2018). China's new economic powerhouse. China: Champion of (which) globalisation? Milano: Ledizioni LediPublishing, 13–37.

Armstrong, K. (2017). Brexit time: Leaving the EU-why, how and when? London: Cambridge University Press.

Avdan, N. (2013). Controlling access to territory: economic interdependence, transnational terrorism, and visa policies. J. Confl. Resolut. 58, 592–624. doi: 10.1177/0022002713478795

Bickers, R. (2017). Out of China: How the Chinese ended the era of Western domination. Cambridge, M.A: Harvard University Press.

Boon, H. (2017). Hardening the hard, softening the soft: assertiveness and China's regional strategy. J. Strateg. Stud. 40, 639–662. doi: 10.1080/01402390.2016.1221820

Brandt, J. (2021). How autocrats manipulate online information: Putin’s and xi’s playbooks. Wash. Q. 44, 127–154. doi: 10.1080/0163660X.2021.1970902

Chhabra, T., Doshi, R., Hass, R., and Kimball, E. (2020). Global China: technology. Brookings. Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/global-china-technology/ (Accessed April 26, 2025).

Chu, Y., and Zheng, Y. (2020). The decline of the Western-centric world and the emerging new global order. London: Routledge.

Csurgai, G. (2018). The increasing importance of geoeconomics in power rivalries in the twenty-first century. Geopolitics 23, 38–46. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2017.1359547

Denny, B. (2015). “Comparing political communities in Hong Kong and Taiwan,” in Presented at the 12th Annual California Graduate Student Conference on May 7, 2015. Irvine, CA: The University of California.

Fidow, A. (2023). Effect of strong passport on economic growth: how African politics have incapacitated their passports. J. Polit. Sci. Int. Relat. 6, 9–15. doi: 10.11648/j.jpsir.20230601.12

Freisleben, I. (2019). Passport power - citizenship by investment programmes exploiting spatiotemporal hierarchies of passports. A master’s thesis submitted to the department of social and welfare studies in partial fulfilment of the MA in ethnic and migration studies. Linköping: Linköping University.

Gill, B., and Huang, Y. (2006). Sources and limits of Chinese "soft power". Survival 48, 17–36. doi: 10.1080/00396330600765377

Grieger, G. (2016). One belt, one road (OBOR): China's regional integration initiative. Policy Commons. Belgium: European Parliamentary Research Service.

Gulddal, J., and Payne, C. (2017). Passports: on the politics and cultural impact of modern movement control. Passports 25, 9–23. doi: 10.5250/symploke.25.1-2.0009

Harpaz, Y. (2021). Conspicuous mobility: the status dimensions of the global passport hierarchy. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 697, 32–48. doi: 10.1177/00027162211052859

Henley and Partners. (2024). The Henley passport index - methodology. Available online at: https://www.henleyglobal.com/passport-index/about#:~:text=Global%20ranking%20and%20visa%20lists,up%20relevant%20visa-policy%20shifts (Accessed April 26, 2025).

Hung, K., Ren, L., and Qiu, H. (2021). Luxury shopping abroad: what do Chinese tourists look for? Tour. Manag. 82:104182. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104182

Keshavarz, M. (2015). Material practices of power - part I: passports and passporting. Des. Philos. Pap. 13, 97–113. doi: 10.1080/14487136.2015.1133130

Khan, K., Su, C., Umar, M., and Zhang, W. (2022). Geopolitics of technology: a new battleground? Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 28, 442–462. doi: 10.3846/tede.2022.16028

Li, L. (2018). China’s manufacturing locus in 2025: With a comparison of “made-in-China 2025” and “industry 4.0”. Tech. Forecast. and Soc. Change. 135, 66–74.

Liang, W., and Yang, M. (2019). Urbanisation, economic growth and environmental pollution: evidence from China. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 21, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.suscom.2018.11.007

Lim, C., and Wang, Y. (2008). China’s Post-1978 experience in outbound tourism. Math. Comput. Simul. 78, 450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.matcom.2008.01.033

Mirrlees, T. (2006). “American soft power or American cultural imperialism?” in The new imperialists: Ideologies of empire. ed. C. Mooers (Oxford: One World Press), 198–228.

Nye, J. (2023). Soft power and great-power competition: Shifting sands in the balance of power between the United States and China. Singapore: Springer.

Okagbue, H., Oguntunde, P., and Bishop, S. (2021). Significant predictors of Henley passport index. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 22, 21–32. doi: 10.1007/s12134-019-00726-4

Pan, L., and Mishra, V. (2018). Stock market development and economic growth: empirical evidence from China. Econ. Model. 68, 661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2017.07.005

Pereira, V. (2013). “The papers of state power: the passport and the control of mobility” in The making of modern Portugal. ed. L. Trindade (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 17–43.

Roberts, K. (2019). Crises of representation and populist challenges to liberal democracy. Chin. Polit. Sci. Rev. 4, 188–199. doi: 10.1007/s41111-019-00117-1

Sarpong, S. (2024). “"we are poor, because you are rich": revisiting the equity phenomenon in geopolitics” in Equity and sustainability. Approaches to global sustainability, markets, and governance. eds. S. Seifi and D. Crowther (Singapore: Springer), 3–21.

Simons, G. (2022). “Inevitable” and “imminent” invasions: the logic behind Western media war stories. J. Int. Anal. 13, 43–58. doi: 10.46272/2587-8476-2022-13-2-43-58

Surak, K. (2024). The misuse of citizenship and residence by investment: Going beyond the FATF/OECD report to assess key risks. Working paper 02–24. London: LSE Department of Social Policy.

U. S. Government Print Office (2004). China as an emerging regional and technology power - implications for U.S. economic and security interests. Hearing before the U.S.-China economic and security review commission on February 12-13, 2004. Available online at: https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/transcripts/2.12.04HT.pdf (Accessed March 23, 2024).

Whyte, B. (2008). Visa-free travel privileges: an explanatory geographical analysis. Tour. Geogr. 10, 127–149. doi: 10.1080/14616680801999984

Wigell, M., Scholvin, S., and Aaltola, M. (2019). Geo-economics and power politics in the 21st century: The revival of economic statecraft. Oxon: Routledge.

Keywords: passport power, soft power, Chinese politics, international politics, diplomatic relations

Citation: Hung J (2025) China’s passport power: a comparative analysis of visa-free access in advanced economies. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1550833. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1550833

Edited by:

Kilian Spandler, University of Gothenburg, SwedenReviewed by:

Elyta Elyta, Tanjungpura University, IndonesiaMehraj Wani, University of Kashmir, India

Copyright © 2025 Hung. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jason Hung, eXNoMjZAY2FtLmFjLnVr

Jason Hung

Jason Hung