- 1Research Institute Transitions, University of Namur, Namur, Belgium

- 2Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

The rise of radical right parties (RRPs) across democracies has raised pressing questions, particularly as they gain parliamentary representation even in contexts previously considered resistant to their influence. Typically adopting confrontational and polarizing approaches, RRPs challenge not only government policies but also foundational political norms, creating significant uncertainty within legislative bodies. While much of the existing research has focused on their discourse strategies, there remains a limited understanding of how these parties influence parliamentary dynamics after they enter national parliaments. We examine the role of the Portuguese radical right party Chega in reshaping parliamentary dynamics, specifically conflict, following its rapid rise in 2019—a striking development in a country previously considered immune to such phenomena and with a party system known for being highly stable. We approach conflict by examining unanimous and without opposition votes, assessing the frequency with which each party finds itself on the losing side of a vote, and calculating a disagreement index (DI) for each legislative term. Additionally, we measure conflict across various policy areas and identify its sources by distinguishing between conflict driven by Chega’s behavior toward other parties and conflict triggered by other parties’ responses to Chega’s legislative proposals. Our analysis draws on parliamentary votes from 2002 to 2024, encompassing all parties with representation in the Assembleia da República. Our findings reveal that Chega’s entry has significantly accelerated the ongoing erosion of parliamentary consensus, further reinforcing broader transformations within the Portuguese parliament. The study demonstrates how radical right parties serve as powerful drivers of parliamentary conflict, both by introducing highly polarizing issues—primarily related to Civil Rights and Liberties, as well as Law, Crime, and Defense—and by provoking strong, often adversarial responses from other parties, including a de facto cordon sanitaire strategy, where certain parties categorically refuse to support Chega’s legislative proposals regardless of the substance. This paper contributes to the broader literature by providing new insights into how RRPs reshape parliamentary behavior, offering a case study of Portugal’s late and rapid RRP emergence. The findings underscore the critical role of these parties in disrupting consensus-driven political cultures and shaping the political debate.

Introduction

The rise and consolidation of populist and radical right parties across various democracies (Rensmann, 2018) raise important questions about the consequences of their entry into parliamentary institutions, particularly the uncertainty they introduce. Typically, radical right parties (RRPs) adopt confrontational stances, engaging in debates marked by negative emotions and polarized rhetoric (e.g., Valentim and Widmann, 2023), particularly on their flagship issues, such as immigration (Van Kessel, 2021; Schwalbach, 2023). These parties build their platforms on challenging the political status quo, often making their role in opposition especially fraught, as they repeatedly contest not only government policies but also established political norms (Valentim, 2024), thus challenging foundational political institutions (Lewandowsky et al., 2021).

Portugal, for a long time, stood as one of the few exceptions to this trend in Europe. However, the election of the RRP Chega (Enough, in English), in 2019, marked the end of the Portuguese exceptionalism. With Chega becoming the third-largest party in the Portuguese parliament in 2022 and the second-largest after the 2025 snap elections, one of the fastest growing paces of RRPs in Europe,1 the parliament faces a new situation that could test its historically consensus-driven political culture (De Giorgi et al., 2017). This late and rapid rise of Chega, in Portugal, presents us with an opportunity to assess how the emergence of RRPs influence well consolidated dynamics of cooperation, and conflict, in a national parliament.

New entrants, particularly at the ideological extremes, are known to disrupt policy stability—a key condition for political systems’ development (Tavits, 2006). Yet, our understanding of how RPPs influence parliamentary dynamics and policy-making remains limited (Heinze, 2022; Schwalbach, 2023). The research on this topic has largely concentrated on their language and discourse strategies (Magnusson et al., 2018; Rensmann, 2018; Atzpodien, 2022; Esguerra et al., 2023; Schwalbach, 2023), with less emphasis on concrete actions, namely their voting behavior (Greilinger and Mudde, 2024). While recent studies, especially those examining the European Parliament (e.g., Brack and Marié, 2024; Greilinger and Mudde, 2024), have started to address this gap, our understanding of how the presence of RRPs reshapes the dynamics of conflict, consensus, and policymaking within legislative bodies remains in its initial steps. How does the parliamentary presence of a radical right party like Chega reshape patterns of conflict and consensus?

This paper examines the voting behavior of parties in the Portuguese parliament, offering insights into the role of a RRP (Chega) in shaping parliamentary dynamics following its entry. To achieve this, we approach conflict through various analytical lenses, including examining unanimous and without opposition votes, assessing the frequency with which each party finds itself on the losing side of a vote, and calculating a disagreement index (DI) for each legislative term. Additionally, we measure conflict across various policy areas and identify its sources by distinguishing between conflict driven by Chega’s behavior toward other parties and conflict triggered by other parties’ responses to Chega’s legislative proposals. Our analysis draws on parliamentary votes from 2002 to 2024, encompassing all parties with representation in the Assembleia da República. Parliamentary votes are well suited for studying parties’ behavior, shaped by the interplay between cooperation and conflict, as they reveal not only parties’ positions on different issues but also the messages they seek to convey to voters (Hohendorf et al., 2020).

The findings of the paper demonstrate how the presence of a RRP can intensify the decline in parliamentary consensus, reinforcing an ongoing transformation. They also show how these parties can be a key driver of parliamentary conflict—both through the polarizing issues they introduce to the legislative agenda and through the strong, often adversarial, reactions they provoke from other parties.

The remainder of this article is organized in five main sections. The first section outlines the theoretical framework and develops the expectations that guide the analysis. The second section provides an overview of the case under study, explaining its relevance to the broader literature on radical right parties and conflict in the parliamentary arena. The third section details the research design, methods, and data used to test the hypotheses. The fourth section presents the results of the analysis, highlighting the key findings. Finally, the article concludes by discussing the implications of the findings (and its shortcomings), their contribution to the literature, and directions for future research.

Theory and expectations

The growing parliamentary presence of RRPs has attracted scholarly attention across several areas, inter alia, their entry into government coalitions (e.g., Lange, 2012), their influence on public attitudes toward immigration (e.g., Gul, 2023), the reactions of mainstream parties to their rise (e.g., Bale et al., 2010; Van Spanje, 2010; Rooduijn et al., 2014; Schumacher and Van Kersbergen, 2016), and their policy impact on issues like immigration and welfare state (e.g., Afonso and Papadopoulos, 2015; Lutz, 2019). However, as recently noted by Heinze (2022) and Schwalbach (2023), there is a gap in research regarding our understanding of RRPs’ influence within the more institutionally constrained context of parliaments. Drawing on literature examining the rise and influence of RRPs, opposition party behavior, and parliamentary dynamics, we aim to explore to what extent Chega’s entry into the Portuguese parliament reshaped patterns of conflict and cooperation in legislative voting. To do so, we formulate a set of expectations (E1–E6) that reflect the descriptive and exploratory nature of our claims, grounded in existing research and theoretical reasoning. These expectations vary in analytical scope: some pertain to general patterns of parliamentary conflict, while others focus on inter-party behavior or specific policy domains.

Should more conflict be expected? On which issues?

Empirical research across various countries demonstrates that opposition parties in parliaments frequently adopt cooperative behavior (Cowley and Stuart, 2005; Mújica and Sánchez-Cuenca, 2006; Andeweg et al., 2008; Christiansen and Damgaard, 2008; Giuliani, 2008), suggesting that opposition does not inherently translate to perpetual conflict (Norton, 2008).2 However, the surge of RRPs in national parliaments (Krouwel and Lucardie, 2008; Bolleyer and Bytzek, 2013; Vries and Hobolt, 2020) challenged this assumption. These parties frequently adopt political strategies centered on confrontational tactics, populist rhetoric, sharp divergences from mainstream policies, particularly on polarizing issues such as immigration, national identity, and law and order (Mudde, 2007; Wagner and Meyer, 2017). Since RRPs build their platforms on challenging the status quo, their role as opposition parties tends to be especially contentious, as they consistently confront both government policies and broader political norms (Valentim, 2024).

This is not to say that consensus and conflict in a parliamentary arena is not influenced by other factors, such as the type of government (Duverger, 1951; Sartori, 1976; Roqué and Márquez, 2015) or the sway of external forces, such as severe economic and political crises (Bosco and Verney, 2012; Moury and De Giorgi, 2015). Yet, one particularly disruptive factor is the entry of new political parties, which can significantly alter the political landscape and reshape patterns of party competition (Tavits, 2006; Grotz and Weber, 2016). We argue this effect is especially pronounced with the arrival of radical right parties, given their tendency to challenge established norms, polarize debates, and introduce new lines of political division, as the literature suggests (Bischof and Wagner, 2019).

By their very nature, “new parliamentary parties are less predictable in their behavior than established ones” (Grotz and Weber, 2016, p. 449). Successful new entrants, especially those situated at the ideological extremes, can disrupt policy stability—an essential condition for the stable development of political systems (e.g., Tavits, 2006). The arrival of parties or candidates representing a novel ideological space and seeking to challenge dominant players, and the status quo, often raises concerns about their consequences on parliamentary dynamics, making uncertainty a central issue (Grotz and Weber, 2016). This is particularly true for RRPs, which have gained footholds in national parliaments (e.g., Vries and Hobolt, 2020) and are considered the most significant threat to contemporary democracy (Bichay, 2022), as they challenge both the form and substance of democratic institutions (Valentim, 2024). These concerns are particularly relevant in Portugal, a parliament accustomed to a consensus politics tradition, where Chega’s confrontational style and anti-establishment rhetoric may directly challenge established parties and disrupt parliamentary norms. Thus, following previous literature, we anticipate that overall parliamentary conflict levels have risen with the entry of Chega into the parliamentary arena in 2019 (E1). This first expectation underlines the dual nature of RRPs as both drivers of heightened conflict and disruptors of established patterns of parliamentary behavior among existing parties.

One of the most defining characteristics of RRPs is their strong opposition to immigration and the rights of ethnic minorities (Mudde, 2007; Pirro, 2014; Sakki and Pettersson, 2016; Rydgren, 2017). While opposition parties often cooperate within the legislative process to maximize their influence, we believe RRPs in opposition are more likely to adopt a confrontational stance, particularly on issues that align with their core ideological priorities. On topics such as immigration and national identity, where they hold uncompromising views, RRPs are less inclined to seek common ground, either due to a policy-seeking strategy or by fearing that cooperation may alienate their core supporters as it makes them appear aligned with the political establishment (Mújica and Sánchez-Cuenca, 2006).

In line with other radical right parties, Chega bases much of its platform on law and order, anti-establishment critiques, restrictive immigration policies, and a limited state (e.g., Carvalho, 2022b). Analysis of Chega’s social media communication reveals a consistent focus on immigration and diversity, marked by explicitly nationalist rhetoric (Mendes, 2021). This combination of issues and rhetoric positions Chega as a confrontational force in parliament, particularly on topics of their ‘owned issues’, such as law and order, immigration, and multiculturalism. However, these issues have historically played a secondary role in Portuguese politics, where socioeconomic debates have traditionally dominated (Hutter and Kriesi, 2019; Carvalho and Duarte, 2020; Mendes and Dennison, 2021). Nevertheless, considering Chega’s platform, it is likely that an intensification of the conflict on these issues has followed as they bring a new cultural conflict dimension to the parliament, reshaping the nature of parliamentary debate. In short, we expect Chega to adopt a more confrontational stance on issues concerning “civil rights and liberties” and “law, order and defense” (E2).

Who drives more conflict? Identifying the sources of disagreement

The anticipated increase in parliamentary conflict following the entry of a RRP, like Chega, can be explained by the necessity for every party to define its stance toward others, including the decision of whether to cooperate politically (Van Spanje, 2010). This situation gives rise to two interconnected dynamics that drive disagreement. First, conflict is shaped by Chega’s own parliamentary behavior—whether it attempts to engage cooperatively by supporting proposals from other parties or, alternatively, takes an oppositional stance by systematically rejecting them. Second, the level of conflict depends as well on how established parties respond to Chega’s legislative initiatives—whether they adopt a confrontational approach by voting against its proposals or choose a more cooperative stance by voting in favor or abstaining.3

Regarding the first dynamic, the RRPs’ sharp critiques of established politics might lead to their refusal to align with perceived elites, as they position themselves as defenders of the “ordinary” citizen against a corrupt establishment (Mudde, 2007). Furthermore, they frequently delegitimize and demonize political opponents, portraying them as morally corrupt and acting against the interests of “the people” (Mudde, 2015; Müller, 2016). This is also true in the Portuguese case, where Chega frequently portrays political elites, and the State, as deeply corrupt, accusing them of mismanaging taxpayer money and branding the current fiscal system as an act of “extortion” against hardworking individuals (Mendes, 2021). This rhetoric often manifests as strong anti-establishment stances, framing the political system as “corrupt and rotten” and arguing that it fails to serve the industrious members of society (Mendes, 2022). Such messaging may make Chega reluctant to engage in legislative cooperation, as aligning with other parties risks being perceived as collusion with the very elites the party publicly opposes. Consequently, we expect Chega to reject cooperation with established parties across the political spectrum and to consistently oppose proposals advanced by others (E3).

Furthermore, established parties’ responses also play a crucial role in shaping conflict—the second dynamic previously underlined. While RRPs can often be excluded or ignored during campaigns, such strategies rarely apply in parliament, where all parties enjoy rights such as proposing legislation and influencing the agenda (Heinze, 2022). The presence of RRPs forces established parties to take positions on new issues, and they can either opt for an accommodative or adversarial strategy (Meguid, 2005). These responses have the potential to reshape discussions and the legislative agenda while influencing the dynamics of consensus and conflict (Meguid, 2008; Abou-Chadi and Krause, 2020).

Right-wing mainstream parties often respond to the rise of successful radical right populist parties (RPPs) with an accommodative strategy (Meguid, 2005; Van Spanje, 2010). In Portugal, although the center-right party (PSD) emerged as the leading party in the 2024 and 2025 snap elections, it chose not to form a governing alliance with Chega. Instead, it opted to govern with a relative majority—likely to avoid reputational costs and the risk of alienating segments of its vote base (Akkerman and Rooduijn, 2015; McDonnell and Werner, 2019). Nonetheless, there are reasons to expect a different dynamic within the parliamentary arena. First, the PSD and Chega have already collaborated in Portugal’s autonomous regions, suggesting that cooperation in parliament is far from improbable. since Chega’s parliamentary debut in 2019 and until 2024—during a period when the Socialist Party was in government—both the PSD and Chega have operated in opposition, making them natural allies in that context. Third, when new parties emerge and pose an electoral threat, established parties often respond by adjusting their strategies and moving ideologically closer to the challenger (Harmel and Svåsand, 1997; Van Spanje, 2010). Taken together, these considerations lead us to expect that right-wing parties—particularly the PSD—are more likely to cooperate with Chega (E4).

Conversely, in the case of left-wing mainstream parties (PS), we do not expect significant cooperation to emerge (E5) for two main reasons. First, from Chega’s entry into parliament until the 2024 general election—which marks the endpoint of this analysis—the Socialist Party (PS) has held governing power. Moreover, starting in 2022, the Socialist Party has governed with a single-party absolute majority in parliament. Second, although the agenda of radical-right parties can influence entire party systems—not just mainstream right-wing parties (e.g., Bale et al., 2010)—opposition parties are generally more susceptible to this contagion effect than those in government (Van Spanje, 2010).

Regarding radical-left parties, such as BE (Left Bloc) and CDU (Democratic Unity Coalition), which traditionally occupy a permanent opposition role (De Giorgi and Russo, 2018), are expected to refuse any form of cooperation with Chega. These parties are likely to systematically vote against Chega’s proposals, employing what resembles a cordon sanitaire strategy within the parliamentary arena (E6). This deliberate adversarial stance aligns with what scholars like Downs (2001, 2002, 2012), van Spanje (2010) and Van Spanje and de Graaf (2017) describe as a strategy of “ostracism”—a concerted effort to marginalize another party. The logic behind this expectation is that, as argued in van Spanje (2010), other niche parties, such as (former) communist and green parties, not only are fundamentally different from the RRPs, they also have more to lose when changing positions and aligning with the radical right. While government-opposition dynamics can sometimes foster cooperation between parties on opposite ends of the political spectrum, the relationship between radical-left and radical-right parties is distinct. Here, ideological antagonism and the radical left’s commitment to countering the influence of RRPs make cooperation far less likely, if not entirely absent. Together, the interplay of Chega’s confrontational behavior and the strategic (but expectably different) responses of established parties have potentially created a scenario of heightened parliamentary conflict in Portugal.

Exploring Chega’s rise in Portugal: significance and case context

While many democracies have faced rising unpredictability, volatility (Vries and Hobolt, 2020; Draca and Schwarz, 2024), and a surge in populist and far-right movements over recent decades (Rensmann, 2018), Portugal stood as a notable exception until recently. The country’s party system remained remarkably stable, even in the face of significant challenges like the eurozone crisis (Jalali, 2019; Pinto and Teixeira, 2019; Lisi et al., 2020). However, this stability experienced a major shift in 2019 with the entrance of Chega into parliament—a historic breakthrough for the radical right in Portugal (Heyne and Manucci, 2021).

The notion of “Iberian exceptionalism,” previously used to categorize Portugal4 alongside Spain (e.g., Heyne and Manucci, 2021), was effectively challenged with the 2019 legislative elections, which marked Chega’s entry into parliament by securing its first seat. Led by André Ventura, Chega secured 1.3% of the vote, marking a symbolic entry of the radical right into Portuguese politics. This breakthrough, alongside the parliamentary representation achieved by other small parties since 2015, has already contributed to a clear trend of increasing party system polarization in Portugal, as demonstrated by recent data (Emanuele and Marino, 2024).

The relevance of Chega in Portuguese politics has grown considerably since its foundation in 2019. In their second election (2022), Chega became the third most voted party, winning 12 seats with 7.2% of the vote. Only 2 years later, in the 2024 general legislative elections, this party consolidated its position as the third biggest party in parliament, winning 18% (3.7 times more than the fourth most voted party) and electing 50 MPs. Finally, in the 2025 election, Chega became the second-largest party in parliament, securing 23% of the vote and electing 60 MPs. In only 6 years since its foundation (in 2019) Chega has become a key and pivotal actor in the Portuguese political system,5 campaigning primarily on the issues of immigration, crime and corruption (Mendes, 2021) and appealing, like other European RRPs, to a young, religious and less educated electorate (Heyne and Manucci, 2021). This recent success has been attributed to Chega’s strong appeal among young, less-educated men and, more significantly, among middle-aged voters without a college degree (Cancela and Magalhães, 2024). Additionally, citizens in rural areas are also more likely to vote for Chega, driven by feelings of political neglect (Magalhães and Cancela, 2025).

Portugal offers, for three main reasons, a compelling context to examine to what extent a RRP reshapes parliamentary dynamics once it gains representation, particularly considering (1) Chega’s anti-establishment position, (2) the new issues it introduces, and (3) the lack of exclusionary tactics toward Chega so far. First, Portugal has long been characterized by having a stable party system6 (Jalali, 2019; Pinto and Teixeira, 2019; Lisi et al., 2020) and a historically consensus-driven political culture (Lijphart et al., 1988; Lijphart, 2012; De Giorgi et al., 2017). This stability, however, was disrupted by recent elections that transformed the political scene. In the past 10 years, five new parties achieved parliamentary representation—a development not seen since 1999 in the Portuguese parliament. Among them, only one experienced exponential growth: Chega, the first radical-right party to enter Portugal’s parliament since the country’s transition to democracy in 1974 (Heyne and Manucci, 2021; Valentim, 2024). Its platform is marked by an “anti-system” stance, emphasizing its distinction from other parties, while advocating for the replacement of the Third Republic and greater concentration of executive powers (Carvalho, 2022b; Mendes, 2022). While this does not align with overtly “antidemocratic” agendas, it reflects what Betz (2005) describes as opposition to a particular form of “representative” democracy—it presents an alternative vision of democracy that might threaten consensus-driven politics (Papadopoulos, 2005).

Second, even in contrast to the CDS-PP, which had traditionally occupied the most right-wing and conservative space in parliament, Chega has adopted a more radical stance (Serra-Silva and Santos, 2023) and introduced political issues that previously lacked prominence in Portugal, particularly immigration7 (Carvalho and Duarte, 2020). Within this, opposition to the Roma minority8 has been a central theme (Heyne and Manucci, 2021), serving as a “core element of its rhetoric” (Magalhães and Lopes, 2024, p. 788). Chega frequently portrays the Roma minority as welfare abusers,9 reinforcing this narrative to mobilize support (Carvalho, 2022b; Mendes, 2022). This marks a significant departure from the past and provides a unique microcosm for examining how established practices of cooperation can survive or adapt in a landscape increasingly marked by radical political actors and the politicization of their typically owned issues.

Third, unlike other European contexts, such as Germany or Sweden (over extended periods), where radical right parties have been isolated through exclusionary tactics and coordinated refusals to collaborate—commonly referred to as the “cordon sanitaire” (Axelsen, 2024)—Portugal has adopted a different approach. Since the 2024 elections, Chega has been granted full parliamentary privileges, including the right to hold important offices in parliament, which has allowed it to play a legitimate role in the legislative process. Furthermore, despite the refusal of the center-right and right-wing cabinet (PSD and CDS-PP) to cooperate with Chega in forming a coalition after the snap elections of 2024 and 2025, the party has played a significant role in the Portuguese autonomous region of the Azores since 2020. Following those elections, Chega secured a formal agreement with the regional government, providing crucial support for the governing program of the center-right and right-wing coalition, which ended in 2023. This distinctive situation provides a valuable opportunity to explore how the integration of RRPs by political parties ideologically close, rather than their marginalization, impacts patterns of cooperation and conflict in parliamentary deliberations and decision-making.

Overall, in addition to the academic interest sparked by the end of “Iberian exceptionalism,” there are other compelling factors that, albeit not exclusive to the country, make Portugal a suitable case for testing our hypotheses. On the one hand, there is not much ambiguity, in both academia and public opinion, concerning Chega’s political-agenda and anti-establishment rhetoric. On the other hand, Chega’s clear ownership of certain issues, and the lack of a concerted agreement to isolate this party in the parliament, make the comparisons between topics and parties, conducted in this study, considerably more meaningful.

Research design, data and methods

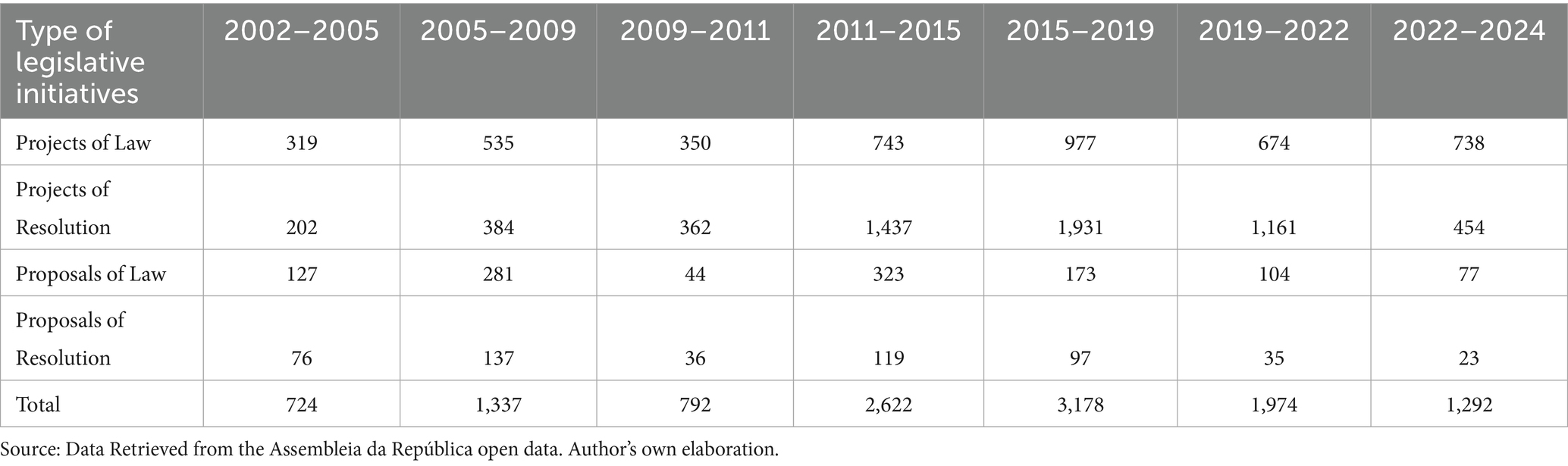

This study relies on a data set of parliamentary votes taken from the Assembleia da República’s website, leveraging their recent open data policy and by using computational methods. The dataset comprises a total of 11,919 parliamentary votes spanning from 2002 to 2024. Each vote corresponds to a single legislative initiative, with only the final vote considered if there were multiple votes. The dataset includes “Proposals of Law” and “Proposals of Resolution” from both the government and regional legislative assemblies,10 as well as “Projects of Law” and “Projects of Resolution”11 from individual MPs and parliamentary groups (Table 1). The period analyzed includes four instances of early elections (2002, 2005, 2011, and 2022), resulting in shorter legislative terms. Data collection ended in April 2024, after the end of the 2022–2024 legislature and before the start of the new legislature term resulting from the 2024 snap general elections. Different government types, such as minority and majority governments, single-party rule, and coalition governments, are present throughout the period.12

Our approach to measuring conflict in the parliamentary arena focuses on parliamentary votes, as they provide a direct means of inferring a political party’s stance and, therefore, the space of political conflict within a legislative body. Parliamentary votes are widely utilized to explore various aspects of political dynamics, including variations in opposition behavior, government-opposition interactions, legislative polarization, and ideological positioning (e.g., Tuttnauer, 2018; Christiansen, 2021). While party voting behavior is shaped by political strategies and tactical compromises (Louwerse, 2011), parliamentary votes remain a crucial tool for assessing ideological or policy divergence among parties in the parliamentary context, as parties frequently use plenary votes, alongside other parliamentary mechanisms, to signal positions and preferences to their voters (Williams, 2016).

Measuring conflict in parliament

To assess conflict and consensus in parliament over time and establish the longitudinal trends occurring in the Portuguese parliament, we first examine parliamentary consensus measured as the frequency in which parties vote in unison in parliament (e.g., Tuttnauer, 2018). To do this, we simply analyze the proportion of unanimous votes and votes without opposition over the years. While some authors have interpreted parliamentary consensus differently—when the main opposition party and the party/parties in government vote in unison (e.g., Mújica and Sánchez-Cuenca, 2006; Palau et al., 2014; De Giorgi et al., 2017)—we adopted a different approach. Within the context of Portugal’s multiparty system, its long-standing stability, which has only recently been disrupted (Serra-Silva and Santos, 2023), and the goal of assessing the impact of RRPs (Chega) in parliament, we have included all parliamentary parties in our measurements of parliamentary consensus.13

This purely and straightforward descriptive approach is valuable for providing a clear overview of general patterns from a longitudinal perspective. However, to more precisely assess the impact of Chega’s entry on parliamentary dynamics, we also zoom in the period starting in 2019 up to 2024. During this period, we measure unanimous votes and votes without opposition while systematically excluding each party (one at a time), excluding both its voting records and the initiatives it proposes. This strategy aims to isolate and evaluate the role that each party, and particularly Chega, plays in intensifying overall parliamentary conflict, on the premise that all other factors remain constant.14

To further explore parliamentary conflict and its evolution over time (beyond the most consensual behaviors such as unanimous and without-opposition votes) we employ a more nuanced measure by calculating the level of disagreement for each parliamentary term, represented by the Disagreement Index (DI). This metric captures the overall degree of conflict surrounding legislative proposals voted on in parliament during each term. The measure is an adaptation of Christiansen’s (2021) formula for assessing disagreement and legislative polarization and we operationalize it as follows:

where the for a given period i, quantifies the average frequency with which an individual MP finds himself on dissent, i.e., on the losing side of parliamentary decisions.

The Index of Disagreement is calculated by weighting the Party Disagreement (the share of times the party finds itself on the losing side)15 on the Number of the Party’s MPs (number of parliamentary seats held by each party),16 reflecting the greater significance of conflict when a larger number of MPs oppose a given bill. While governing parties generally benefit from being on the winning side, they may still find themselves on the losing side in certain votes, particularly in the context of minority governments. Additionally, parties at the ideological extremes of the political spectrum are likely to experience significantly higher levels of disagreement, especially when a government from the opposing ideological camp is in power.

One of the central components of the Index of Disagreement is Party Disagreement. This means our analysis centers on the voting behavior of political parties rather than individual members. In the context of executive-legislative relations in Portugal, political parties constitute the primary organizational entities, and party cohesion is notably high (Leston-Bandeira, 2009). In the infrequent instances when some MPs deviate from their party’s voting line (less than 10%), we have coded the party’s vote in alignment with the majority of its MPs.

Unlike Christiansen’s study, which focuses solely on bills that become laws, our analysis encompasses a broader range of legislative initiatives voted on in parliament. This includes all proposals subjected to a vote, regardless of the outcome, as well as Proposals and Projects of Resolution.17 While these initiatives do not result in laws, they offer valuable insights into the political preferences of parties and are debated and voted on in parliament. Parliamentary votes were categorized as “in favor,” “against,” or “abstention.” In the rare instances when a party missed a vote, their stance was recorded as abstention.

Identifying policy areas

To examine the level of conflict across policy areas, we proceeded with the identification of the main topic of each legislative initiative, relying on transformer-based models. The field of automated text-analysis has seen rapid advancements in the last years, and transformer-based models are the most used to solve different Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks. These models are a form of neural network designed to address sequence transduction challenges, proposing a new network architecture based on attention mechanisms (Vaswani et al., 2017). Unlike many other traditional approaches, transformer-based models consider contextual information and convert entire sentences into vectors within a multidimensional space. These features explain why these models have proven highly effective for a broad range of NLP tasks (e.g., Vaswani et al., 2017; Chinnalagu and Durairaj, 2022; Mugisha and Paik, 2022; Widmann and Wich, 2023).

Therefore, to identify the main policy area of each legislative initiative, we utilized a transformer-based language model, namely XML-RoBERTa (Conneau et al., 2019), which has been previously fine-tuned on political Portuguese data18 to classify political texts according to the major topic codes defined by the Comparative Agendas Project (CAP) (Sebök et al., 2024). The CAP framework encompasses 21 different policy areas, encapsulating the full spectrum of political topics. The model demonstrated an accuracy rate of 0.89 (Sebök et al., 2024). Considering the objectives of this paper, the volume of observations within each policy area, and in the interest of clarity, the 21 major CAP policy areas were consolidated into 11 comprehensive topics.19

To assess the effectiveness of the model in identifying the main policy area for each legislative initiative, we compared its results across the 11 topics with the permanent parliamentary committee responsible for considering and discussing each initiative.20 Since these committees are specialized by subject matter (e.g., “Education and Science,” “Health,” “Environment and Energy”), this comparison allowed us to gauge the model’s performance by examining qualitatively the overlap between the topics assigned by the model and the committees handling each legislative initiative. Despite some limitations,21 this assessment indicates that the model performs considerably well in accurately identifying the topics of the initiatives. For more detailed results on this assessment, please refer to Appendix Figures A1, A2.

Results

Exploring consensus and conflict over time (2002–2024)

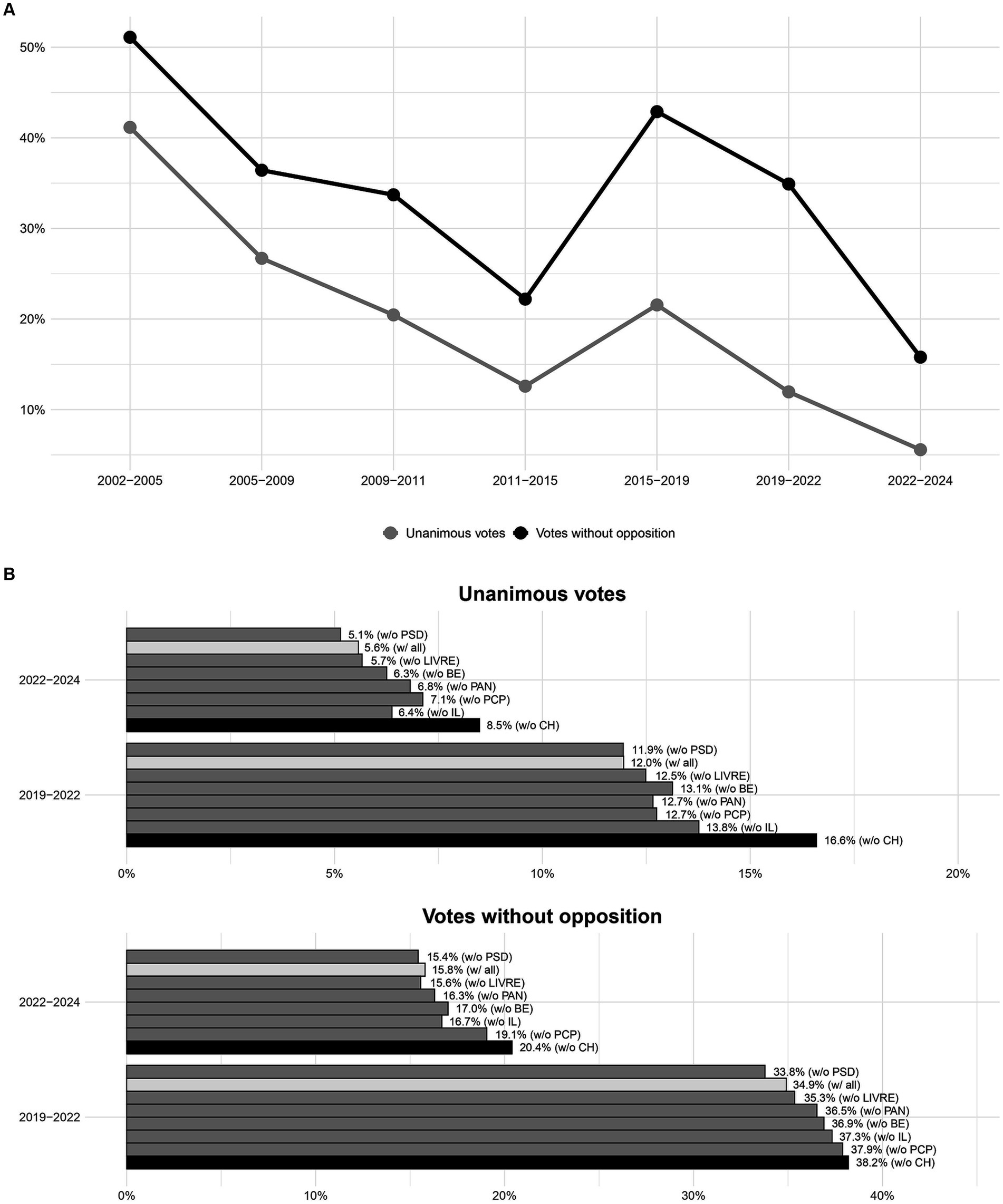

We expected that Chega’s rapid growth in parliamentary representation would likely influence the patterns of consensus and conflict within the parliamentary arena. To investigate this, we analyze parliamentary consensus in two different ways. First, we examine the proportion of unanimous votes and votes without opposition across the entire period (2002–2024) to identify overarching longitudinal trends (Figure 1A). Second, we concentrate on the last two legislative terms under analysis, marking the period since Chega’s entry into parliament (2019–2024, Figure 1B). In this step, we aim to isolate the influence of individual parties on unanimous votes and votes without opposition by systematically excluding each party, one at a time, disregarding both their voting behavior and their legislative initiatives proposed in parliament.

Figure 1. Unanimous and without opposition votes in the Portuguese parliament. (A) Over time (2002–2024). (B) Between 2019 and 2024 and the role of each party. In figure (B), the values represent: (1) the proportion of unanimous votes and votes without opposition when all parties are included (shown in light gray), and (2) the proportion of unanimous votes and votes without opposition when each party is systematically excluded (with Chega represented in black). When a party is excluded, both their votes in parliament and their proposed initiatives are removed from the analysis. This method highlights the specific influence of individual parties on the levels of unanimous votes and votes without opposition.

The results (see Figure 1A) indicate, first and foremost, a pronounced and consistent decline in parliamentary consensus in Portugal. In the early 2000s, over 50% of parliamentary initiatives were approved without opposition, and more than 40% achieved unanimous support. In the most recent term covered by this analysis (2022–2024), these figures had dropped sharply to approximately 15 and 6%, respectively. These levels represent the lowest parliamentary consensus observed in the 21st century. However, this downward trend was notably interrupted during the 2015–2019 legislative term. This was an exceptional period marked by the unprecedented “contract parliamentarism” agreement reached between PS and three radical left parties: BE, PCP, and PEV (Fernandes et al., 2018). This arrangement had, for the first time, brought the radical left parties (BE, PCP, and PEV) closer to the government, allowing them to play a more significant role in shaping executive policy-making (Fernandes et al., 2018). The interruption of this trend during the 2015–2019 legislative term strongly suggests that the rising levels of conflict observed prior to Chega’s entry into parliament were driven primarily by the radical-left parties. When these parties gained greater influence over government policy during this period, parliamentary conflict levels noticeably declined. However, did Chega’s entry into parliament accelerate and accentuate this declining trend?

Examining Figure 1B reveals clearly that across both terms and regardless of the indicator used (unanimous votes or votes without opposition), parliamentary consensus increases most significantly when Chega is excluded from the analysis, compared to the exclusion of any other party. In scenarios where Chega’s voting behavior and initiatives are excluded (simulating a parliament without the party), the proportion of unanimous votes and votes without opposition always increases noticeably. When viewed together, Figures 1A,B reveal that, although the downward trajectory of consensual politics began before Chega’s entry into the Portuguese parliament, its presence appears to have intensified this declining trend. This impact is particularly evident in the reduction of initiatives receiving unanimous support.

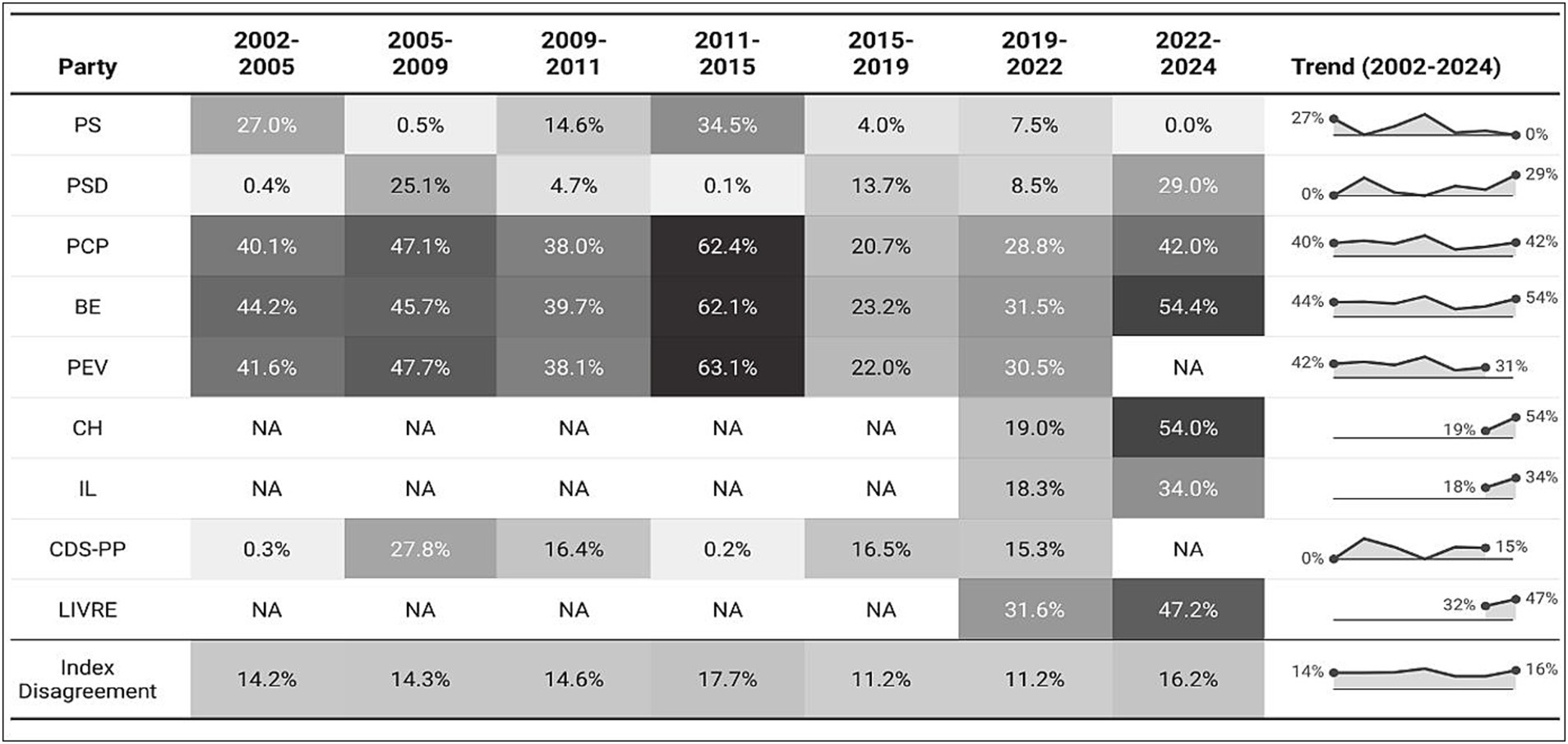

To better understand the consensual and conflictual dynamics of the Portuguese parliament, we have also computed a Disagreement Index (DI) for each legislature. This is a more refined metric to assess the levels of conflict over legislation. Overall, the DI values (last row of Figure 2) similarly suggest that conflict in the Portuguese parliament has increased over time, with these scores shifting from 14.2% in 2002–2005 (and 14.3% in the subsequent legislature) to 16.4% in the last period covered. However, this increase in conflict since 2002 has not been downright gradual as suggested by our previous analysis. Instead, the highest DI value occurred in the 2011–2015 legislative term (17.7%). This term began after the Portuguese request for financial assistance and early elections of 2011 (Fernandes, 2011), which led to unprecedented levels of public contestation and demonstrations from multiple actors and sectors of society (Baumgarten, 2016; Fernandes, 2017; Carvalho, 2022a). This strongly suggests that the eurozone crisis and the implementation of the economic adjustment program were pivotal in shaping the 2011–2015 term as the most conflictual period in the history of the Portuguese parliament in the 21st century. While the contestation was primarily driven by the three radical left parties (PCP, BE, and PEV), which were on the losing side in more than 60% of the voted proposals, PS also contributed greatly, namely 34.5% of the time on the losing side, which is the highest value registered for the main opposition party.

Figure 2. Disagreement over legislative initiatives in parliament. 1. The values represent how often each party did not vote with the winning side. The index of disagreement captures how often an average MP did not vote with the winning side. 2. Parties in government: 2002–2005 and 2011–2015: PSD & CDS-PP; remaining legislatures: PS.

As previously established, parliamentary conflict decreased considerably in the following term (2015–2019), in line with the results of Christiansen’s (2021), namely due to the unprecedented “contract parliamentarism” agreement reached between PS and three radical left parties, BE, PCP, and PEV (Fernandes et al., 2018). This period of reduced conflict extended beyond the unprecedented term, although the “contract parliamentarism” agreement did not hold beyond the 2019 legislative elections. The management of the COVID-19 crisis may have contributed to maintaining lower levels of parliamentary conflict during the 2019–2022 legislative term. Despite some disagreements regarding the handling of the public health crisis and the necessity of repeated lockdowns (Serra-Silva and Santos, 2022), there was broad consensus among political elites and public opinion on the importance of confinement measures, restrictions, and vaccination efforts (Magalhães et al., 2020; Peralta-Santos et al., 2021), leading to a more consensual behavior in parliament, as occurred in other countries (e.g., Merkley et al., 2020; Lehtonen and Ylä-Anttila, 2024).

After these two “consensual” periods (the less conflictual ones in the 21st century), the Portuguese parliament reached, during the last legislative term covered (2022–2024), the second highest DI (16.4%). This period coincides with the heightened relevance of Chega in parliament, going from 1 to 12 MPs. Although this term has seen a series of cabinet changes and mediatic scandals that culminated with the resignation of its prime minister, Chega has played a role in heightening the conflict in parliament. Alongside BE, Chega emerges as one of the parties more often on the losing side, namely in 54% of votes. While in previous periods the conflict was always led by parties further to the left on the political spectrum (PCP, BE, and PEV), except for 2015–2019, the emergence of Chega brought another strong opposition party, but at the other end of ideological continuum. Additionally, two other parties have expanded the opposition landscape recently. On the left, LIVRE has joined PCP and BE in leading opposition efforts during the most recent legislature, while on the right, IL has contributed to heightened conflict, albeit to a lesser extent than Chega. Furthermore, given the increasing share of Chega’s MPs, their actions in parliament greatly contributed to the increase of the DI recorded in the last term. This finding aligns with existing literature on RRPs, which has observed that they tend to intensify polarization in parliamentary debates (e.g., Schwalbach, 2023).

Combining the insights from unanimous votes, votes without opposition, and the disagreement index, our findings indicate that Chega’s entry into parliament has indeed contributed to increased conflict, thereby confirming our first expectation (E1). However, it is important to note that while Chega has played a role in amplifying parliamentary conflict, the extent of this escalation is not significantly greater than the levels historically associated with established parties on the opposite end of the political spectrum such as the PCP, BE, and PEV. Still, one might ask if Chega is driving conflict in policy areas that were previously less contested?

Conflict across policy areas: not one, but many

Our analysis has thus far revealed a stark decline in consensual behavior and increasing levels of conflict over time. However, this overarching trend may mask crucial differences across different policy areas, as the propensity for parties to shift form their initial positions—and consequently to reach compromises—varies depending on the issue considered (Mújica and Sánchez-Cuenca, 2006; Adler and Wilkerson, 2013). This sets the stage for a pivotal inquiry: how does this heightened conflict manifest across various key policy dimensions, particularly those central to Chega’s agenda? To tackle this question, we have identified the main topic of each voted initiative by considering 11 different policy areas for the period 2019–2024.

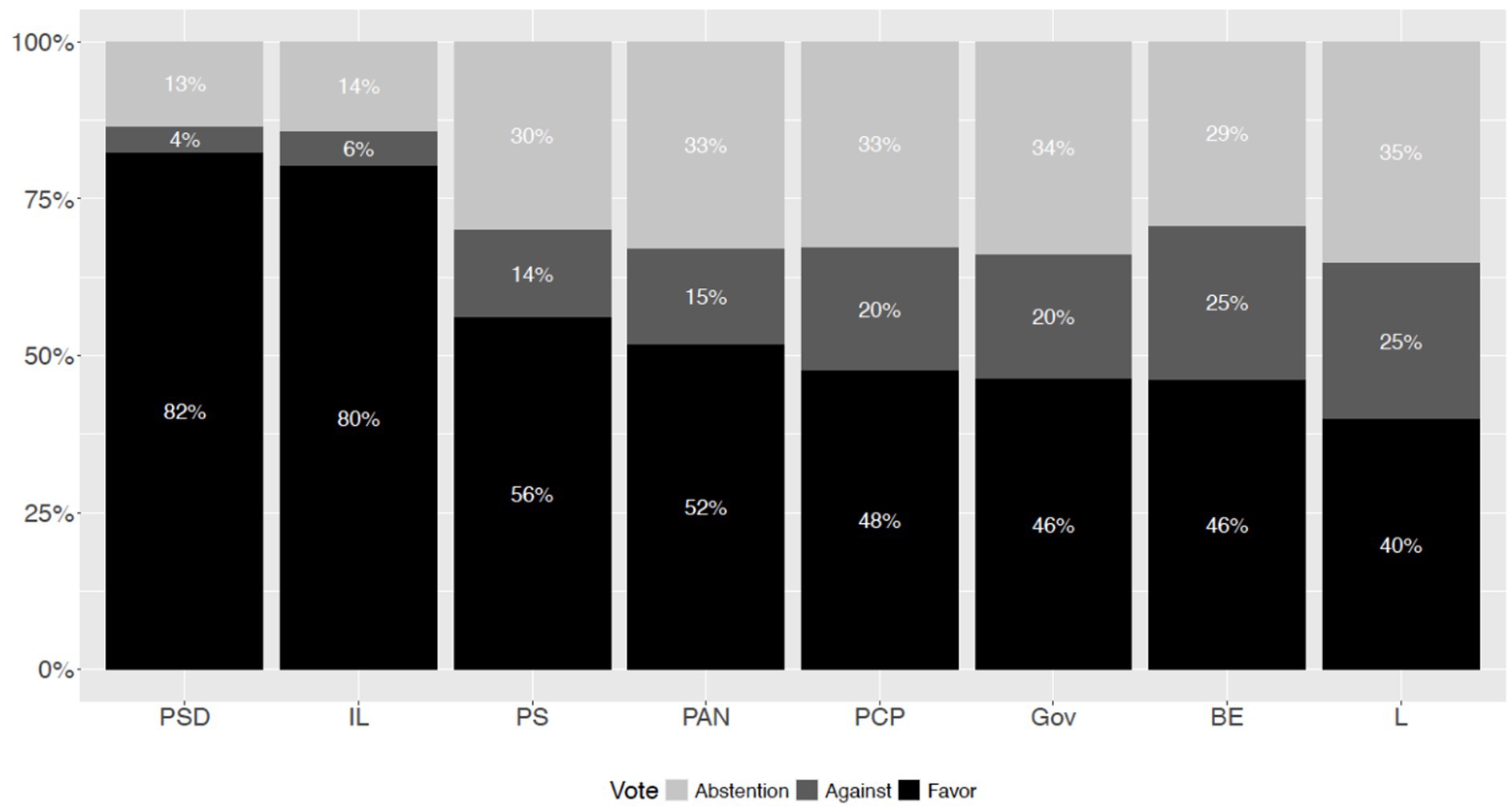

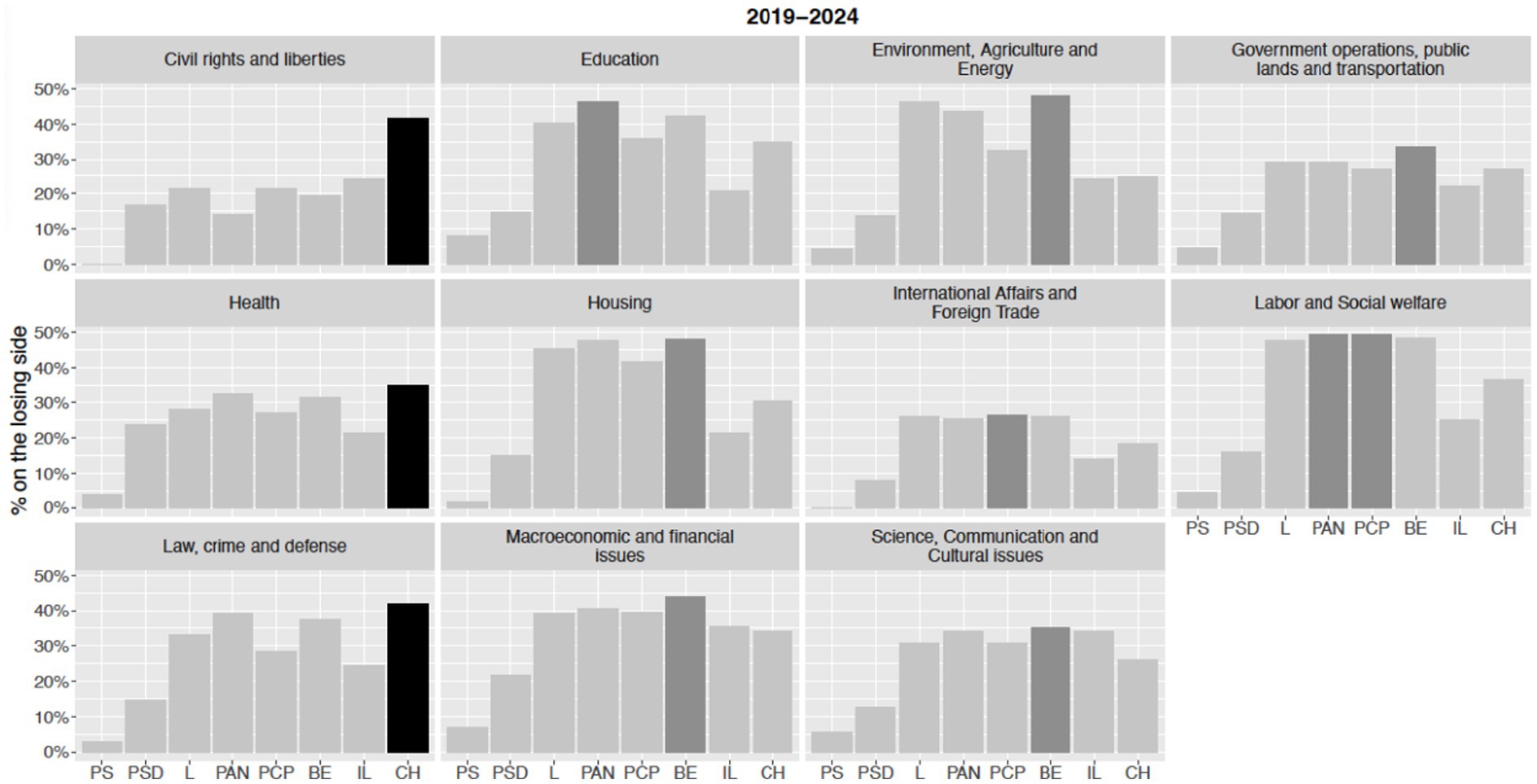

Figure 3 provides a detailed view of the dynamics of cooperation and conflict in the Portuguese parliament across different policy areas, highlighting the role each party plays in these interactions. This analysis is achieved by examining the frequency with which each party finds itself on the losing side of a vote. Focusing on Chega’s parliamentary behavior, the party emerges as the leading force of opposition in three key policy areas: Health, Civil rights and Liberties and Law, Crime and Defense. The latter two are central to the party’s platform and are broadly aligned with the priorities of other RRPs across Europe. Furthermore, Chega’s behavior is remarkably distinct from the remaining parties in the case of Civil rights and Liberties, where it demonstrates levels of conflict that, on average, are twice as high as those of other parties. It is crucial to underscore that both Civil Rights and Liberties and Law, Crime, and Defense have historically played a relatively minor role in Portuguese politics (e.g., Hutter and Kriesi, 2019).

Figure 3. Frequency with which each party ends up on the losing side of votes across policy areas (2019–2024). In this figure, we are only considering the parties that were in parliament in both terms (2019–2022 and 2022–2024). Therefore, CDS-PP and PEV are not considered.

Surprisingly, Chega leads the opposition as well in one policy domain that has not, so far, been considered central to its platform: Health. A closer look at the data suggests that this outcome is likely driven by two distinct but related logics. First, it seems to reflect the party’s strong opposition to pandemic-related measures between 2020 and 2022.22 This aligns with the dynamics of “medical populism,” in which public health becomes a politicized arena for drawing a divide between ‘the people’ and ‘the establishment’ (Lasco and Curato, 2019). These findings appear consistent with Falkenbach and Greer’s (2021) mapping of how populist radical right (PRR) actors responded to the COVID-19 pandemic—often by blaming migrants, institutions, or foreign governments, and by calling for the reopening of borders or services with limited scientific justification.23 Second, these findings seem to also reflect a broader welfare chauvinist stance, grounded in the view that welfare services—including healthcare—should be restricted “to our own” (Andersen and Bjørklund, 1990).

In the remaining areas, most of which are tied to material concerns, the opposition has been primarily driven by radical left parties, with BE taking a particularly prominent role (leading opposition in 5 out of 8 policy areas). The prominence of radical left parties in leading the opposition during the 2019–2024 period, rather than Chega, is particularly striking given that the Socialist Party was in government. Considering the policy distance between parties, one would expect Chega to oppose the government much more frequently than it has, particularly in comparison to the radical-left parties. Nonetheless, these conflictual dynamics reinforce the trends observed throughout the entire period of the 21st century: irrespective of the governing party or coalition (PS or PSD and CDS-PP), the Portuguese political landscape has been characterized by a cohesively bloc of radical-left parties (PCP, BE, and PEV). This bloc has demonstrated a constant and similar parliamentary behavior and has consistently positioned itself in opposition to successive governments (Serra-Silva and Santos, 2023).

Taken together, these results support our second expectation (E2), specifically that Chega adopts a more confrontational stance on issues central to its ideological platform—namely, Civil rights and liberties, as well as Law, crime, and defense—thus increasing conflict. Beyond aligning with our expectations, these results also corroborate previous findings, which indicate that radical-right parties tend to amplify the prominence and conflict, namely over liberal-authoritarian and immigration-related issues (Wagner and Meyer, 2017; Schwalbach, 2023). Moreover, it is crucial to emphasize that the confrontational behavior of RRPs in parliament regarding their flagship issues remains evident even in a country where such concerns have historically been neither salient among public opinion nor prioritized by mainstream parties (Hutter and Kriesi, 2019; Carvalho and Duarte, 2020; Mendes and Dennison, 2021). Indeed, established parties in Portugal have traditionally achieved broad consensus on these matters (e.g., Carvalho and Duarte, 2020), further highlighting the disruptive impact of Chega’s parliamentary presence.

Who drives the conflict? Chega’s behavior toward other parties

Assessing the frequency with which a party finds itself on the losing side of a vote provides a general indication of its parliamentary behavior and the extent to which it aligns or conflicts with other parties. However, to better understand the mechanisms underlying parliamentary conflict and Chega’s influence on these dynamics, it is crucial to explore two potential drivers of conflict: (a) Chega’s voting behavior toward other parties and (b) the voting behavior of the remaining parties concerning Chega’s legislative initiatives.

Despite Chega’s “anti-system” stance and its advocacy for replacing the current Portuguese Republic, the party does not adopt a consistent adversarial position toward all established parties represented in parliament, as shown by Figure 4. In fact, ideological proximity seems to effectively explains Chega’s voting behavior toward other parties’ proposals. As illustrated in Figure 4, a clear division between two blocs emerges. On one side, we find PSD and IL, the parties ideologically closest to Chega, with Chega supporting over 80% of their proposals and rejecting only a small fraction (4 and 6%, respectively). On the other side, we find the remaining parties—from the center-left PS to the radical-left PCP and BE—whose proposals Chega has voted favorably to a significantly lesser extent. Despite Chega’s anti-establishment rhetoric and its overarching hostility toward political elites, the party does not entirely reject cooperation across the political spectrum, thus our third expectation (E3) is not confirmed. Instead, its voting behavior in the parliamentary arena aligns more closely with ideologically proximate parties. Therefore, Chega’s parliamentary behavior seems to follow the same principles that guide other parties, as party behavior in the Portuguese parliament is considerably shaped by ideological proximity (Serra-Silva and Santos, 2023).

Who drives the conflict? Established parties’ behavior toward Chega

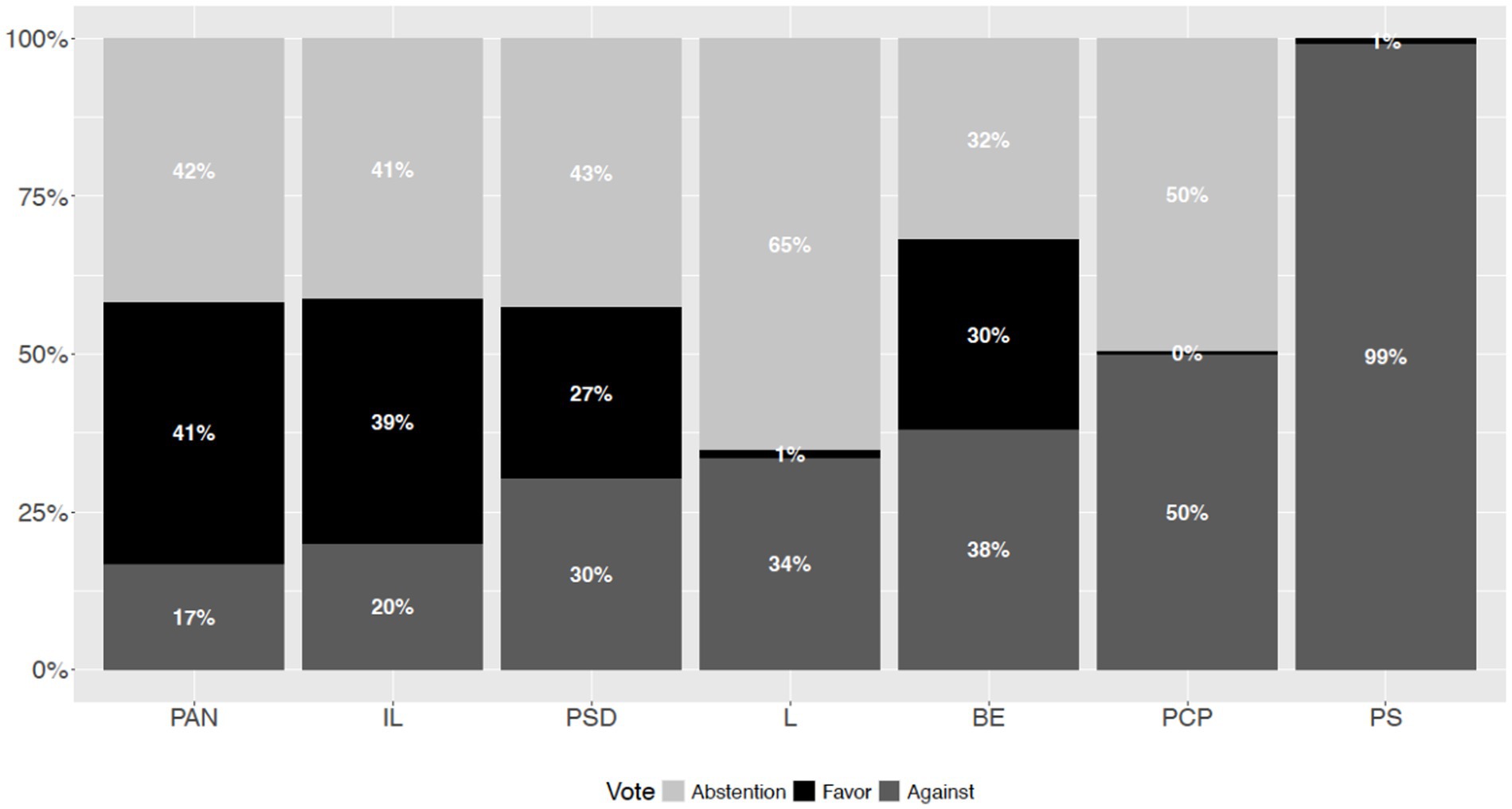

Thus far, we have demonstrated that Chega does not consistently adopt a confrontational stance toward other parties. Instead, the party frequently cooperates with those that are ideologically aligned with it. But how do the remaining parties respond to Chega within parliament? Do they present a unified adversarial front in response to Chega’s ideology and nature, or are their voting patterns similarly influenced by ideological proximity? To answer this, we examined how established parties vote on legislative initiatives authored and proposed by Chega.

Figure 5 reveals that a collective adversarial response to Chega was far from being established in the Portuguese parliament. Instead, two quite distinct strategies have been adopted. On one hand, a group of parties, including PS, PCP, and LIVRE, have maintained a strategy of parliamentary cordon sanitaire around Chega, virtually refraining from approving any initiatives proposed by the party. This approach, uniquely directed at Chega (please refer to Appendix Figures A3–A5), underscores the perception among these parties that Chega is a qualitatively distinct party warranting outright ostracism. Within this group, PS (the governing party in both terms analyzed) adopted a consistently adversarial strategy, while PCP and LIVRE divided their approach between outright rejection and abstention. On the other hand, a different group of parties, including PSD (center-right mainstream party), IL (liberal party), PAN (animalist party), and BE (radical left party), chose not to isolate Chega in parliament and supported a non-negligible number of its initiatives. However, even within this group, differences emerge: PSD and BE rejected more of Chega’s proposals than they supported, whereas IL and PAN supported more initiatives than they opposed. As a result, PAN and IL emerged as the most accommodating parties toward Chega in parliament. Unlike PS, PCP, and LIVRE, whose behavior reflects a clear strategy of exclusion, the parliamentary conduct of PSD, IL, PAN, and BE appears influenced by a combination of government-opposition dynamics and ideological proximity.

A closer examination of the two main parties in the Portuguese political system, PS and PSD, reveals starkly contrasting approaches to Chega. The PS, the leading party on the center-left of the political spectrum, has adopted a consistently adversarial strategy by choosing to not engage with Chega’s proposed legislative initiatives, regardless of the topic. This behavior appears to signal that Chega’s positions fall outside the realm of political acceptability, reinforcing a strategy of exclusion. In contrast, the PSD has shown a more accommodating approach, supporting a significant share of Chega’s initiatives (27%) and abstaining on an even larger proportion (43%). Given that abstention is generally regarded as a cooperative gesture within the Portuguese parliament, though less so than outright support (De Giorgi and Russo, 2018), this pattern suggests a degree of alignment or at least a willingness to engage with Chega’s proposals, clearly distinguishing the PSD’s approach from PS’s adversarial approach. These findings largely support our fourth and fifth expectations (E4 and E5)—that mainstream right-wing parties are more inclined to cooperate with Chega, while the PS has adopted an adversarial stance toward it, setting up a cordon sanitaire strategy that seems to publicly signal that Chega’s positions lie outside the boundaries of political acceptability.

Finally, it is important to closely examine the behavior of radical-left parties, particularly PCP and BE. Although these parties have displayed broadly similar behavior in the parliamentary arena (Serra-Silva and Santos, 2023) and share similar ideological and policy positions (Fernandes et al., 2018), they have pursued markedly different strategies regarding Chega. Much like the Socialist Party (PS), the Communist Party (PCP) has clearly implemented a cordon sanitaire approach, outright rejecting and refusing to vote in favor of any legislative initiatives proposed by Chega. In contrast, BE has supported a minority, yet substantial (30%), share of Chega’s initiatives, despite the significant ideological divide between the two parties. Despite the stark ideological differences between these two parties, such dynamics did not prevent the BE from approving some of Chega’s initiatives—an outcome that could eventually be expected if one considered only the government-opposition divide and anti-establishment positions. However, this behavior by the BE should not be interpreted as evidence of ideological contagion from Chega, as there is no indication that Chega’s policy positions influenced the party’s platform. In sum, considering both PCP and BE strategies, our sixth expectation (E6) is only partially supported—confirmed for PCP, but rejected for BE.

Conclusion

As RRPs continue to gain parliamentary representation, even in contexts previously thought to be resistant to their rise, we explore how the emergence and growth of Chega in Portugal have influenced parliamentary dynamics, particularly the patterns of cooperation and conflict between parties. Using parliamentary data, covering a period of 22 years, our study offers answers to the following question: how does the parliamentary presence of a radical right party like Chega reshape patterns of conflict and consensus? Looking at diverse measures of parliamentary conflict and cooperation, and using state-of-the-art methods for text classification, we were able to shed a new light on the impact that RRPs have on conflict and polarization over legislation in the parliamentary arena.

Our analysis reveals three key findings: first, the presence of a radical right party like Chega intensifies the decline in parliamentary consensus, accelerating a transformation that was already underway in the Portuguese parliament. Second, while Chega contributes to parliamentary conflict, its impact remains comparable to that of radical left parties, suggesting that its significance lies more on the issues it brings more conflict into parliament rather than the sheer level of disagreement it generates. Indeed, Chega’s confrontational stance is particularly evident in policy areas traditionally associated with the radical right, namely Civil rights and liberties and Law, crime and defense, matters previously non-salient in the Portuguese political landscape. Third, despite its anti-establishment rhetoric, Chega has cooperated in the legislative arena with establishment parties, particularly those more ideologically aligned with, such as PSD and IL, by supporting the large majority of their proposals. In contrast, center-left and some of the radical left parties (PS, Livre, and PCP) have largely implemented a parliamentary cordon sanitaire, refusing to support almost any legislative initiative proposed by Chega. Notably, the Socialist Party, which was in government during both terms (2019–2024), rejected 99% of Chega’s proposals, reflecting a deliberate strategy to oppose and isolate the radical right in the legislative process.

These findings carry significant implications for the existing literature. First, they demonstrate how the presence of a RRP can accelerate and intensify parliamentary conflict. Previous research has shown that the entry of new political actors, particularly those situated at ideological extremes, often disrupts established norms and reshapes parliamentary behavior (e.g., Tavits, 2006; Bischof and Wagner, 2019), especially RRPs by polarizing debates and introducing new lines of political division (Mudde, 2007; Valentim, 2024). The findings of this paper highlight that Chega is indeed a pivotal actor in this transformation, particularly by introducing an intensely confrontational stance on issues that are core to its platform, such as Civil rights and liberties and Law, crime, and defense. In doing so, Chega not only reshapes parliamentary conflict but also redefines the political agenda. These issues, once peripheral to political debate in Portugal, have now gained prominence and begun to challenge the traditional structures of the Portuguese party system.

Second, these findings highlight a paradox in Chega’s parliamentary behavior. Despite its anti-establishment rhetoric, Chega often votes in favor of proposals from other parties, showcasing a pragmatic approach that seems indifferent to the identity of the proposing party. Remarkably, the party supports over 40% of proposals made by radical left parties, even from those that refrain from voting favorably any of Chega’s proposals. Moreover, on material or economic issues, Chega often aligns more closely with the status quo than of the radical-left parties, for instance. While Chega leads the opposition on previously non-salient issues, such as Civil rights and liberties and Law, crime and defense, radical-left parties still dominate the opposition on socio-economic matters. This highlights a notable gap between Chega’s rhetoric and its actual voting behavior, a pattern previously observed in the European Parliament by other scholars (e.g., Greilinger and Mudde, 2024).

In stark contrast, some parties treat Chega as a qualitatively distinct and controversial actor, consistently refusing to vote in favor of its initiatives, regardless of their substance. This behavior signals to voters that Chega is perceived as operating outside the boundaries of what is considered acceptable in a democratic regime. While these findings align with previous research showing that radical right parties often provoke strong adversarial responses from mainstream and radical-left parties—who may adopt cordon sanitaire strategies to marginalize RRPs and limit their legislative influence (Van Spanje and de Graaf, 2017; Heinze, 2022)—the reality is more complex. Notably, both the mainstream right-wing party (PSD) and the radical-left party BE have, at times, voted in favor of Chega’s proposals, demonstrating that adversarial strategies are not uniformly applied. These instances reflect a blend of strategic pragmatism, shared policy interests, and government-opposition dynamics. Nevertheless, they definitely challenge the linear narrative of outright rejection.

The findings of this paper highlight that Chega is a significant driver of parliamentary conflict, both by introducing polarizing issues to the legislative agenda and by provoking strong, often adversarial reactions from other parties. These insights pave the way for several avenues of future research. With Chega gaining significant electoral traction, electing 60 MPs and becoming the second-largest party in parliament after the 2025 snap elections, pressing questions emerge about its medium and long-term effects on parliamentary conflict and consensus. Specifically, future studies could explore how these parties are shaping the political agenda and influencing the behavior of other parties. While this study provides descriptive insights and does not aim to establish causality, it identifies patterns that invite further investigation through causal oriented research designs. Moreover, comparative studies are crucial to determine whether the dynamics observed in Portugal—where political competition is primarily shaped by materialist concerns—are unique to this context or indicative of broader trends in RRP behavior across different cases. In countries where structural conditions are more favorable to the rise of RRPs, their impact on parliamentary dynamics is likely to be even more pronounced, offering a fertile ground for deeper exploration. Furthermore, our findings are based on parties’ voting behavior which, while fundamental, represent only one dimension of parliamentary conflict. Chega’s behavior and rhetoric—often disregarding norms of parliamentary decorum—have also emerged as key sources of disruption. A diachronic analysis of parliamentary speeches could therefore serve as a valuable complement to this study in the future.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Author contributions

NS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SS-S: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TS: Data curation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia under the grants 2022.05382.CEECIND/CP1756/CT0007, UIDB/50013/2020, and UIDP/50013/2020.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable feedback provided by several members of CEVIPOL at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, in particular Jean-Benoît Pilet, Sebastian Rojon, Awenig Marié, Piotr Marczyński, and Stine Hesstvedt.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1553921/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Chega achieved extraordinary growth, increasing its vote share from 1.3% in 2019, its first national election, to 23% in 2025—an exceptional rise within just 6 years, translating into an expansion from 1 MP to 60 MPs. To the best of our knowledge, no RRP in Europe has achieved such rapid electoral success at the national level, particularly within their first contested elections.

2. ^This tendency is particularly pronounced in multiparty systems with frequent coalition and minority governments, where institutional rules and the dynamics of coalition politics provide opportunities for minority parties to shape policy. In these settings, incentives are created for opposition parties to adopt a cooperative stance on specific issues, despite their minority position (Hohendorf et al., 2020).

3. ^In the Portuguese Parliament, abstention is typically regarded as a cooperative gesture, albeit less so than voting in favor (De Giorgi and Russo, 2018).

4. ^The prolonged absence of radical-right parties in Portugal is often attributed to the country’s historical experience with dictatorship and the ability of established parties to assimilate their potential demand side (Halikopoulou and Vasilopulou, 2014).

5. ^Chega’s growing political significance in national politics was further demonstrated during the 2021 Presidential elections, where its leader, André Ventura, ranked as the third most-voted candidate, securing 11.9% of the total vote and garnering the support of 496,653 voters (CNE, 2021).

6. ^Most parties were founded either immediately before or shortly after the transition to democracy, with the notable exception of the Partido Comunista Português (PCP—Communist Party), established in 1921. Since 1974, the PCP, the right-wing CDS-PP, the center-right Partido Social Democrata (PSD—Social Democratic Party), and the center-left Partido Socialista (PS—Socialist Party) have dominated the political landscape. In 1999, the Bloco de Esquerda (BE—Left Bloc), a left-libertarian/radical party, gained parliamentary representation. Until recently, these four main parties, along with the BE, effectively monopolized parliamentary representation. More recently, three new parties have entered Parliament: the environmentalist party PAN (People–Animals–Nature) in 2015; the economically libertarian IL (Liberal Initiative); and the pro-European, left-wing party LIVRE (Free), both in 2019.

7. ^In addition to the lack of salience in public opinion, Portugal has not experienced any significant influx of migrants during the period surrounding Chega’s emergence and rapid rise (Mendes, 2021; Gonçalves and Pereira, 2024).

8. ^The Roma community in Portugal, settled since the 15th century with a final wave in the 19th, is primarily native-born and not immigrants. Although the Portuguese Census does not track ethnicity, Roma (ciganos) are estimated to make up only about 0.5 percent of the population (Magalhães and Lopes, 2024).

9. ^One of the earliest and most pronounced (and consistent) features of Chega’s political agenda has been its targeting of the Roma population, claiming that “gypsies mainly live on state subsidies and refuse to abide by the law” (Mendes, 2022, p. 332).

10. ^According to the Regimento da Assembleia da República [RAR], regional legislative assemblies also have the ability to submit legislative initiatives to the national parliament.

11. ^While not frequently employed, it’s important to note that the President of the Republic also possesses the authority to present Projects of Resolution, and these too have been incorporated into the analysis.

12. ^See Table A1 in Supplementary material for more details.

13. ^Including all parliamentary parties may not be the most suitable approach in comparative studies, particularly when considering significantly different institutional contexts and varying levels of party system fragmentation and polarization, as these factors can heavily impact the results.

14. ^While the premise is not entirely accurate—given that the presence of any party influences the behavior of others—this effect applies universally to all excluded parties, not solely to Chega.

15. ^Whenever a party abstained, we classified it as being on the winning side of the vote for two reasons: (1) in the Portuguese Parliament, abstention is typically seen as a cooperative stance (De Giorgi and Russo, 2018); (2) when a single party holds an absolute majority and abstains on a bill proposed by another party, it is likely because the party agrees with the expected outcome of the vote. Treating such instances as being on the losing side would not be logical in this context.

16. ^For the seat share of each party in each Legislature, please refer to Appendix Table A2.

17. ^Projects of Resolution are initiatives proposed by Members of Parliament or parliamentary groups that, even if approved, do not take the form of law and are generally of a political nature. In contrast, Proposals of Resolution are initiatives presented by the Government to the Assembly of the Republic for the purpose of reviewing and approving treaties or international agreements.

18. ^The Portuguese training data encompasses data from three domains: legislative documents, executive speeches and executive orders.

19. ^The consolidated topics are the following: “Civil rights and liberties,” “Education,” “Environment, Agriculture and Energy,” “Government operations, public lands and transportation,” “Health,” “Housing,” “International affairs and foreign trade,” “Labor and social welfare,” “Law, crime and defense,” “Macroeconomic and financial issues” and “Science, communication and cultural issues.” Please refer to Appendix Table A3 for more detailed information on the merging of the CAP topics.

20. ^The Parliamentary Commissions have experienced changes during the period under analysis. Both their number and the scope of issues they address have shifted over time, though.

21. ^Since the scope of the 11 topics and the areas covered by each committee do not align perfectly, a quantitative evaluation using common performance metrics (e.g., precision, accuracy, and recall) was not feasible.

22. ^By searching for the words ‘pandemia’ and ‘covid’ in the body of each initiative classified as health-related, we found that 43% of these measures are associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

23. ^For instance, in February 2021—when Portugal recorded the highest rates of new infections and deaths per million globally (Reuters, 2021)—Chega proposed a resolution in parliament (990/XIV/2) calling for the reopening of hair salons and barbershops. The proposal was rejected or met with abstention by the majority of parties.

References

Abou-Chadi, T., and Krause, W. (2020). The causal effect of radical right success on mainstream parties’ policy positions: a regression discontinuity approach. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 50, 829–847. doi: 10.1017/S0007123418000029

Adler, E. S., and Wilkerson, J. D. (2013). Congress and the politics of problem solving. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Afonso, A., and Papadopoulos, Y. (2015). How the populist radical right transformed Swiss welfare politics: from compromises to polarization. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 21, 617–635. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12182

Akkerman, T., and Rooduijn, M. (2015). Pariahs or partners? Inclusion and exclusion of radical right parties and the effects on their policy positions. Polit. Stud. 63, 1140–1157. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12146

Andersen, J. G., and Bjørklund, T. (1990). Structural changes and new cleavages: The progress parties in Denmark and Norway. Acta Sociologica, 33, 195–217. doi: 10.1177/000169939003300303

Andeweg, R. B., De Winter, L., and Müller, W. C. (2008). Parliamentary opposition in post-consociational democracies: Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands. J. Legis. Stud. 14, 77–112. doi: 10.1080/13572330801921034

Atzpodien, D. S. (2022). Party competition in migration debates: the influence of the AfD on party positions in German state parliaments. Ger. Polit. 31, 381–398. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2020.1860211

Axelsen, J. E. (2024). The cordon sanitaire: a social norm-based model. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties 34, 277–297. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2023.2168272

Bale, T., Green-Pedersen, C., Krouwel, A., Luther, K. R., and Sitter, N. (2010). If you can't beat them, join them? Explaining social democratic responses to the challenge from the populist radical right in Western Europe. Polit. Stud. 58, 410–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00783.x

Baumgarten, B. (2016). “Time to get re-organized! The structure of the Portuguese anti-austerity protests” in Narratives of identity in social movements, conflicts and change (Research in social movements, conflicts and change). ed. L. E. Hancock, vol. 40 (Leeds: Emerald Publishing), 155–187.

Betz, H. G. (2005). “Against the system: radical right-wing populism’s challenge to liberal democracy” in Movements of exclusion: radical right-wing populism in the Western world. ed. J. Rydgren (Commack, NY: Nova Science Publ), 25–40.

Bichay, N. (2022). Populist radical-right junior coalition partners and liberal democracy in Europe. Party Politics, 30, 236–246. doi: 10.1177/13540688221144698

Bischof, D., and Wagner, M. (2019). Do voters polarize when radical parties enter parliament? Am. J. Polit. Sci. 63, 888–904. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12449

Bolleyer, N., and Bytzek, E. (2013). Origins of party formation and new party success. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 52, 773–796. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12013

Bosco, A., and Verney, S. (2012). Electoral epidemic: the political cost of economic crisis in southern Europe, 2010–11. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 17, 129–154. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2012.747272

Brack, N., and Marié, A. (2024). From fringe to front? Assessing the voting influence of the radical right in the European Parliament. Eur. Union Polit. 25, 748–771. doi: 10.1177/14651165241268127

Cancela, J., and Magalhães, P.. (2024). As bases sociais do novo sistema partidário. Available online at: https://sondagens-ics-ul.iscte-iul.pt/2024/03/15/as-bases-sociais-do-novo-sistema-partidario/ (Accessed December 20, 2024).

Carvalho, J. (2022a). Understanding the emergence of extreme right parties in Portugal in the late 2010s. Parliament. Aff. 76, 879–899. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsac001

Carvalho, J., and Duarte, M. (2020). The politicization of immigration in Portugal between 1995 and 2014: a European exception? J. Common Market Stud. 58, 1469–1487. doi: 10.1111/jcms.13048

Carvalho, T. (2022b). Contesting austerity: social movements and the left in Portugal and Spain (2008–2015) Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Chinnalagu, A., and Durairaj, A. K. (2022). Comparative analysis of BERT-base transformers and deep learning sentiment prediction models. Proceedings of the 2022 11th international conference on system modeling and advancement in research trends.

Christiansen, F. J. (2021). The polarization of legislative party votes: comparative illustrations from Denmark and Portugal. Parliament. Aff. 74, 741–759. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsab029

Christiansen, F. J., and Damgaard, E. (2008). Parliamentary opposition under minority parliamentarism: Scandinavia. J. Legisl. Stud. 14, 46–76. doi: 10.1080/13572330801920937

CNE (2021). Resultados Globais. Eleições Presidenciais. Available online at: https://www.eleicoes.mai.gov.pt/presidenciais2021/resultados/globais (Accessed November 15, 2024).

Conneau, A., Khandelwal, K., Goyal, N., Chaudhary, V., Wenzek, G., Guzmán, F., et al. (2019). Unsupervised cross-lingual representation learning at scale. Proceedings of the annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics, 8440–8451.

Cowley, P., and Stuart, M. (2005). Parliament: hunting for votes. Parliament. Aff. 58, 258–271. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsi021