- 1Department of Political Science and Social and Philosophical Disciplines, Abai Kazakh National Pedagogical University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

- 2Department of Political Science, M. Auezov South Kazakhstan University, Shymkent, Kazakhstan

This study aims to analyze the factors influencing youth political participation, focusing on the role of political culture, transforming youth activities, patriotism, and civic responsibility in the context of developing democracies. Using data collected from 350 young people across five major universities in the large cities of Kazakhstan, we employed structural equation modeling to test our hypotheses. The results reveal that political culture significantly influences political participation, and this relationship is strengthened by civic responsibility, but not by patriotic sentiment. Interestingly, while youth with strong democratic values actively participate in political processes, they prefer to work within existing institutional frameworks rather than engage in transformative activities. This study provides theoretical and practical recommendations for increasing political engagement among the youth in Kazakhstan. Unlike existing studies that focus on institutional forms of youth participation, this study is the first to systematically analyze the role of civic responsibility and patriotism and their links to political culture and political participation, which opens new perspectives for understanding the mechanisms of youth engagement in the political process in emerging democracies.

1 Introduction

Participation in politics is essential for strong democracy and active citizenship. As global democracies change and with the rise of digital technology and increasing political indifference in many places, understanding what influences young people’s engagement in politics has become very important both academically and practically. This issue is particularly urgent in countries such as Kazakhstan, where the reform of government institutions occurs alongside political growth of the younger generation.

At the international level, research on youth political participation highlights both universal and culturally specific trends in how young people build their civic identities, develop an interest in politics, and choose to become involved in formal and informal political activities. As global inequality, instability, and misinformation grow, young people become more vulnerable and vital for fostering democratic change.

Kazakhstan is located at the intersection of various cultural and political influences from Eurasia, making it an interesting location to examine how young people engage in politics. On the one hand, the state actively promotes an agenda of political modernization and adopts a more responsive approach. On the other hand, barriers still limit young people’s ability to subjectively participate in politics. This allows for a closer analysis of how a combination of institutional, cultural, digital, emotional, and moral factors affects youth involvement in political processes.

Democratic governance is fundamental to modern political systems, as it offers citizens the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes that affect their lives and society. Robust democracy ensures political rights, civil liberties, and equal representation, leading to more stable and prosperous societies (Silander, 2022). Research has shown that democratic systems tend to better protect human rights, promote economic development, and foster social progress through citizen participation and accountability mechanisms (Zarate-Tenorio, 2023).

However, motivating citizens to participate in democratic processes remains a significant global challenge. Low voter turnout, political apathy, and declining trust in democratic institutions are common issues that threaten democratic vitality (Elsässer and Schäfer, 2023). Young people, in particular, often show lower levels of political engagement than older generations, raising concerns about the future of democratic systems (Tzankova et al., 2022). These challenges are particularly acute in emerging democracies where democratic traditions are still developing.

Kazakhstan has presented a unique case of democratic development. Since gaining independence in 1991, the country has transitioned from an authoritarian system toward democratic governance, although this process has faced various challenges. Political culture reflects a mix of traditional values and modern democratic aspirations, with institutions still evolving to support democratic practices (Carley, 2024; Burkhanov and Collins, 2019). Recent reforms have aimed to increase democratic participation; however, the transformation of political culture remains a complex process (Yesdauletova et al., 2024; Tolen, 2020).

Youth participation is particularly crucial in Kazakhstan’s democratic development, as young people represent over 25% of the population and will shape the country’s political future (Kilybayeva et al., 2017). The engagement of the youth in democratic processes is essential for developing sustainable democratic institutions and practices. Moreover, Kazakhstan’s youth, having grown up in the post-Soviet era, potentially bring new perspectives to democratic participation (Sairambay, 2021).

Political participation and civic engagement are essential for understanding democracy, the legitimacy of power, and the functionality of civil society, especially in the face of global instability and digitalization of public life. Traditional definitions, as established by scholars such as Verba et al. (1996), focus on institutional forms of influence such as voting and party membership. However, recent studies increasingly emphasize non-institutional, digital, and symbolic forms of activism, suggesting that participation should be viewed as a continuum from latent engagement to overt political action (Theocharis and van Deth, 2018; Ekman and Amnå, 2012). Koc-Michalska et al. (2016) highlighted that social media not only enhances opportunities for political expression, but also facilitates the creation of new engagement structures.

In Kazakhstan, the current literature has largely concentrated on institutional approaches to youth democratic participation, such as youth organizations and formal political structures (Beylur, 2021). Some studies have explored social media’s role in political engagement (Sairambay, 2021) and the impact of educational institutions (Tokbolat, 2022), but there remains a limited understanding of the psychological and social factors that motivate young Kazakhs to engage in democratic processes. Many studies have described participation patterns without delving into the motivational factors.

Political culture, characterized as the set of values, beliefs, and attitudes that shape citizen engagement with the political system, remains underexplored in the context of Kazakhstan. Modern research seeks to adapt and refine political cultural concepts in a country’s unique situation. Studies indicate a predominantly parochial and subordinate political culture in Kazakhstan with minimal citizen participation in political processes (Kurganskaya et al., 2023). Despite the rising number of online activists, many young people still seem apolitical, although new media can foster political interests and knowledge (Sairambay, 2024).

Research on political-administrative culture highlights that the high-power distance from the Soviet era contributes to societal autocratization, hindering effective reform (Karini, 2024). To assess political culture, researchers often rely on sociological surveys, media content analysis, and the digital behavior of citizens. While some progress has been made, such as the integration of quantitative and qualitative methods to understand political attitudes, significant gaps remain in the literature. For example, most Kazakhstani studies still rely on the Almondian typology of political culture without adapting to modern realities (Welzel, 2021) and often lack operationalized key indicators such as intergenerational trust in institutions and civic identity. Furthermore, research generally overlooks regional, ethnic, and generational differences within Kazakhstan’s political culture, despite international studies emphasizing the importance of political-cultural pluralism.

Although some studies have addressed the impact of social media on youth political socialization (Sairambay, 2024), there is a lack of systematic analysis regarding digital political culture, including aspects such as algorithmic influences, digital citizenship, and clicktivism. Ultimately, Kazakhstan’s academic literature tends to be introverted and poorly integrated into global research networks, thus limiting the use of comparative approaches.

This research gap necessitates a closer examination of what drives Kazakh youth to participate in the democratic processes. Understanding these motivational factors, particularly the roles of political culture, civic responsibility, and patriotism, could provide valuable insights for developing more effective strategies to enhance youth democratic participation in Kazakhstan.

2 Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1 Political culture

Political culture, a critical framework introduced by Almond and Verba (1963) and evolving through decades of scholarship, encompasses shared attitudes, beliefs, values, symbols, and behavioral norms that shape how citizens perceive political systems and their roles within them (Almond and Verba, 1963; Welzel, 2021). This concept is central to understanding political participation, influencing it by shaping perceptions of citizen efficacy, defining normative expectations of engagement, and establishing the legitimacy of different participation forms (Dalton, 2019). While established democracies increasingly see non-institutional participation alongside traditional forms (Theocharis and van Deth, 2018), emerging democracies, such as Kazakhstan, exhibit transitional patterns combining authority deference with growing citizen voice expectations (Sairambay, 2022a). For Kazakh youth specifically, political culture shapes participation through three mechanisms: influencing their sense of political efficacy, forming their understanding of citizenship norms, and establishing the legitimacy of various participation forms from conventional voting to digital activism (Zhampetova et al., 2024; Alisherova, 2024). This framework helps explain the paradox of democratic values coexisting with limited transformative engagement, as Kazakhstan’s hybrid political culture encourages political interest while promoting institutional rather than transformative approaches.

Political culture encompasses cognitive (knowledge of political systems), affective (emotional attachments), and evaluative (judgments about performance) dimensions, which together create diverse patterns across societies (Welzel, 2021). Almond and Verba (1963) identified three primary types: parochial (minimal awareness), subject (awareness without participation), and participant (awareness with active engagement). Most societies exhibit mixed patterns. Contemporary scholarship has evolved this framework, with Dalton and Welzel (2014) distinguishing between “allegiant” cultures that emphasize authority deference and “assertive” cultures that prioritize critical citizenship—a particularly relevant distinction for emerging democracies like Kazakhstan where citizen-state relationships continue to transform.

The bidirectional relationship between political culture and institutions is central to democratic development. Diamond (2016) emphasized that democratic consolidation requires alignment between formal structures and cultural values. While institutions shape citizen orientations, political culture simultaneously influences institutional effectiveness through expectations and norms (Putnam, 2024; Fukuyama, 2018). This relationship becomes particularly complex in transitional societies, where institutional reforms often outpace cultural adaptation, potentially creating what Welzel (2021) describes as formal democratic structures without substantive democratic governance. Post-Soviet political cultures exhibit distinct characteristics, with Jowitt (2023) identifying a “fragmented identity” where Soviet-era values coexist with emerging democratic orientations, and Burkhanov and Collins (2019) highlighting features including high power distance, personalized authority, emphasis on stability, and informal networks that often override formal institutions—all of which significantly shape citizen-state relationships and participation strategies.

Kazakhstan’s political culture represents a unique case of post-Soviet transition, exhibiting a predominantly parochial-subject orientation with emerging participant elements among younger, urban, and educated populations (Tolen, 2020; Kurganskaya et al., 2023). This hybrid culture, shaped by Kazakhstan’s nomadic heritage, Soviet legacy, and post-independence nation-building, is characterized by four key features: a strong emphasis on stability and orderly transitions manifesting as support for strong leadership and gradualist reforms (Burkhanov and Collins, 2019); a complex relationship with authority where traditional hierarchical respect coexists with growing expectations for governmental responsiveness, particularly among youth (Zhampetova et al., 2024); distinctive patterns of political communication creating what Sairambay (2021) describes as a “digital-traditional hybrid” information environment; and a diversity of political subcultures reflecting Kazakhstan’s multi-ethnic composition and regional variations, with differing orientations toward authority, state service expectations, and participation patterns (Beylur, 2021).

2.2 Transforming activities

Transforming activities represent youth-driven actions aimed at influencing political and social structures, ranging from institutional participation to non-conventional activism. Contemporary scholarship recognizes a spectrum beyond traditional electoral behaviors, with Theocharis and van Deth (2018) distinguishing between institutionalized forms and increasingly popular non-institutionalized activities such as protests and social media campaigns.

In Kazakhstan, digital platforms have become crucial for youth engagement, with Tolen and Alisherova (2023) demonstrating how online petitions and civic initiatives create “networked activism” that bypasses traditional gatekeepers. The psychological foundations of these activities are rooted in political efficacy, and Alisherova (2024) found that youth who understood the practical impacts of their engagement were more likely to participate in transformative activities.

The relationship between these activities and political structure is bidirectional. While institutions shape opportunities for engagement, youth activism also influences institutional development. Beylur (2021) documents how youth-led initiatives have contributed to governance reforms, while Kilybayeva et al. (2017) highlight instances in which youth activism has shaped national policy priorities, particularly in education and environmental protection.

2.3 Patriotism

Patriotism represents an emotional and psychological attachment to one’s nation, encompassing feelings of national pride, loyalty, and identification with a country’s symbols, values, and achievements. Unlike civic responsibility, which focuses on duty and obligation, patriotism centers on affective connections to the national community (Bitschnau and Mußotter, 2022; Huddy and Khatib, 2007). In Kazakhstan’s context, as a young nation-state still developing its post-Soviet identity, patriotism holds particular significance in shaping youth political engagement.

Contemporary scholarship distinguishes between multiple forms of patriotic sentiments with different implications for political behavior. Alekseyenok et al. (2024) differentiate between “blind patriotism,” characterized by uncritical acceptance of national policies, and “constructive patriotism,” which combines national loyalty with critical evaluation of government actions. Similarly, Kołeczek et al. (2025) identified symbolic patriotism (emotional attachment to national symbols) and behavioral patriotism (active participation in nation-building), noting their distinct effects on civic engagement.

In Kazakhstan, patriotism plays a complex role in the political development of the youth. Zharkynbekova et al. (2025) show how state patriotic initiatives shape political identity formation among young Kazakhs, while Gabdulina and Ykylas (2018) highlight patriotism’s role in reducing partisan polarization and promoting electoral participation. These findings align with Kamaldinova et al.’s (2015) observation that patriotic sentiments facilitate participation in formal political activities such as voting and youth assemblies.

The relationship between patriotism and digital political engagement reveals distinctive patterns among Kazakhstani youth (GOV.UK, 2024). Nurmatov et al. (2022) observe that social media platforms serve as spaces for expressing patriotic sentiments by sharing national symbols and commemorating historical events. However, Zhong (2014) note that online patriotism does not consistently translate into offline political action, creating a potential disconnect between patriotic expression and substantive political engagement.

In Kazakhstan’s democratic development, patriotism presents both opportunities and challenges. While patriotic sentiments can mobilize youth participation in state-sanctioned activities, Li and Li (2024) cautioned that emphasizing nationalist attachment without corresponding civic consciousness may limit critical engagement with governance issues. This suggests that balanced approaches integrating patriotic sentiment and civic responsibility may be most effective for fostering meaningful youth political participation, as Kazakhstan continues its democratic journey.

2.4 Civic responsibility

Civic responsibility encompasses individuals’ perceived duties toward their political community, focusing on the normative dimension of citizenship rather than emotional attachment to the nation (Blais and Galais, 2015). In Kazakhstan, this concept manifests through specific participatory behaviors, such as a 62.79% turnout in the country’s first direct local elections (Haidar, 2023), indicating strengthening civic consciousness in local governance.

The relationship between civic responsibility and youth political participation operates through multiple psychological mechanisms: it creates an internal motivation that remains resilient when external incentives are weak, establishes participation as a normative expectation, and provides moral justification for political action (Reuter, 2020). Research shows that youths who internalize strong civic responsibility are more likely to engage in both institutional and non-institutional political activities.

For Kazakhstan’s emerging democracy, developing civic responsibility among the youth represents both a challenge and an opportunity. While traditional approaches often emphasize patriotic sentiments, recent initiatives suggest growing recognition of the importance of civic responsibility. Tolen and Alisherova (2023) document emerging educational programs focused on civic duty, whereas Sairambay (2021) notes how digital platforms increasingly frame political participation as a responsibility rather than merely a right.

2.5 Hypotheses development

Participation in democratic processes is fundamental to the health and sustainability of societies. Active citizen participation ensures government accountability, represents diverse societal interests, and contributes to more effective policymaking (Kamaldinova et al., 2015; Diamond, 2016). However, declining political participation, particularly among young people, poses a significant challenge to democratic systems worldwide (Tzankova et al., 2022).

Political Socialization Theory provides a crucial framework for understanding how individuals develop political attitudes and behaviors. According to this theory, people’s political orientations are shaped by various socialization agents, including family, educational institutions, media, and peer groups (Hyman, 1959). The theory suggests that these agents play critical roles in transmitting political values, norms, and behaviors across generations, ultimately influencing individuals’ likelihood of participating in political processes (Janmaat and Hoskins, 2021).

Cultural factors significantly influence patterns of political participation. Political culture, encompassing shared attitudes, beliefs, and values about political systems, shapes how individuals view their roles in democratic processes and their willingness to participate (Kurganskaya et al., 2023; Almond and Verba, 1963). This is particularly evident in Kazakhstan, where traditional cultural values and post-Soviet political heritage have created a unique political culture that influences citizen engagement (Burkhanov and Collins, 2019). Research has demonstrated that societies with political cultures that emphasize citizen engagement tend to have higher levels of political participation (Elsässer and Schäfer, 2023). In emerging democracies, such as Kazakhstan, political culture plays a particularly crucial role in determining whether citizens view political participation as meaningful and legitimate, especially as the country navigates its transition from authoritarian to democratic practices (Zarate-Tenorio, 2023; Tolen, 2020).

H1: Political culture has a positive influence on political life participation among Kazakh youths.

Beyond cultural influences, individuals’ motivation to create change, manifested by transforming activities, represents another significant driver of political participation. Transforming activities encompass actions aimed at influencing political decisions and creating social change (Meyer, 2021). Studies have shown that individuals who believe in their capacity to affect change are more likely to engage in political activities, ranging from voting to active civic engagement (Alscher et al., 2022).

Zhampetova et al. (2024) analyzed the political values of Kazakhstani student youth. The authors note that, despite the combination of traditional and modern values, the level of political activity remains low. The main reasons for the youth ‘cold’ from political participation are lack of trust in institutions and insufficient awareness of political processes. However, there is a tendency toward non-institutional forms of political activity, confirming the changing forms of participation of the modern youth. Alisherova (2024) emphasized the importance of political education in increasing the level of youth involvement in political processes. This article suggests strategies to improve political awareness, including integrating political education into curricula and using digital platforms to disseminate information. Tolen and Alisherova (2023) investigated the impact of the new media on the political participation of Kazakhstani youth. The authors concluded that social networks are becoming an important tool for obtaining political information and organizing civic engagement, especially among young people in rural areas. Sairambay (2024) shows that the use of new media by youth in rural areas of Kazakhstan contributes to increased political awareness and interest in political processes, despite the overall low level of engagement.

H2: Transforming activities have a positive influence on political life participation among Kazakh youths.

The relationship between political culture and transformation activities is noteworthy. Political culture shapes how individuals perceive opportunities for change and their roles in transformation processes. Research indicates that political cultures that support citizen initiatives and value democratic change tend to foster more active engagement in transforming activities (Jelili, 2024). This relationship is especially relevant in transitional democracies, where political culture is evolving along with democratic institutions.

H3: Political culture has a positive influence on transforming activities among Kazakh youths.

Recent research shows that young people in Kazakhstan are shifting from being passive about politics to actively seeking new ways to engage, such as volunteering and participating in online civic initiatives (Zhampetova et al., 2024). Tolen and Alisherova (2023) note that new media makes it easier for them to access information and participate in online petitions and digital activism, lowering barriers to involvement and promoting more informal, networked activism. Alisherova (2024) highlighted the role of both formal and informal political education in building political culture, which encourages local participation. Sairambay (2024) adds that rural youth, who were once excluded from political discussions, are now engaging with important social topics online, showcasing a growing ‘digital political culture’ that fosters new forms of civic engagement. Together, these studies show how improved political culture and access to digital media are transforming the political involvement of young people in Kazakhstan, leading to a shift from passive to active, institutional to informal, and centralized to networked participation. Therefore, the way they engage in politics largely depends on the quality of their political culture and the digital environment in which they interact.

H4: Patriotism moderates the relationship between political culture and political life participation among Kazakh youths.

Traditionally, patriotism has been viewed as a significant motivator of political participation. Scholars have found that emotional attachment to one’s country often correlates with higher levels of political engagement (Kaya, 2022). However, the relationship between patriotism and political participation is complex and varies across political contexts and cultures (Huddy et al., 2021).

Expectations of patriotism to moderate connections between political culture and political participation are found in several theoretical presuppositions:

• Patriotism is a motivational factor (citizens consider their participation a duty to their country, so they are motivated to participate in politics more actively).

• Various effects of patriotism (civil patriotism, nationalism).

• Political culture and identity (election voting as an expression of love for the motherland).

• Dependence on political culture (democratic tradition assumes more common participation, while authoritarism utilizes patriotism as a social mobilization tool). This effect depends on how exactly patriotism is defined and which type of political culture dominates in society.

This can be explained with the following reasons:

• Different type of patriotism (civil patriotism, blind patriotism);

• Cultural and institutional differences (weak influence on stable democracies and propaganda instruments in authoritarian regimes);

• Methodological issues (undefined and vague measurement of patriotism and differences between countries);

• Competing factors (economic interests, ideology, social networks);

• Situative effect (no influence in peaceful times, but activizing people in crisis times).

Patriotism plays a key role in shaping the political culture and participation of Kazakhstani youth by fostering a strong connection with their country and its values, which encourages them to engage more in political processes. Zhampetova et al. (2024) noted that political culture among young people combines traditional values with digital practices, with patriotism serving as an emotional boost that makes political involvement personally important. Gabdulina and Ykylas (2018) show that state patriotism shapes political identity, particularly in a young nation with a developing ideology. Additionally, patriotism helps reduce polarization and promotes participation in formal political activities such as elections and youth assemblies (Kamaldinova et al., 2015). While it can strengthen or weaken the impact of political culture on youth participation, it is essential to differentiate between symbolic patriotism (loyalty and pride) and behavioral patriotism (active participation). To better understand these influences, new ways of assessing patriotism should be developed, especially in light of the digital environment as a platform for expressing patriotic feelings.

H5: Civic responsibility moderates the relationship between political culture and political participation among Kazakh youth, reinforcing the influence of political culture on willingness to engage in institutional and non-institutional forms of political participation.

Civic responsibility is another crucial motivator for political participation, distinct from patriotic sentiments. Research has shown that individuals who view political participation as a civic duty are more likely to engage in democratic processes regardless of their emotional attachment to the nation (Reuter, 2020). This sense of civic responsibility often stems from understanding democracy as a collective enterprise that requires citizen involvement for its proper functioning.

Measuring civic responsibility is a key aspect in assessing the level of citizen engagement in public and political life in both Kazakhstan and the world. The 2024–2025 studies use various approaches to assess this concept, reflecting both quantitative and qualitative methods of analysis.

Surveys are widely used in international practice to assess civic responsibility levels. For example, a 2024 study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) found that 69% of respondents who felt they could influence government action expressed a high level of trust in their national government, while among those who did not feel such influence, this figure was only 22% (OECD, 2024).

In the UK, a 2023/24 survey found that 50% of adults believe it is important to have the opportunity to influence decisions affect their local community. This shows that citizens recognize their responsibility for local issues and want to be involved in the decision-making process (GOV. UK, 2024).

In Kazakhstan, the level of civic responsibility is often assessed by participation in elections. Thus, in November 2023, in the first direct elections of akims of districts and cities of regional significance, voter turnout was 62.79%, which indicates a high level of civic activity (Haidar, 2023).

A 2024 study on social capital and the performance of public councils in Kazakhstan assessed their effectiveness through their impact on social issues in various areas, such as health and the environment. This highlights the importance of citizen participation in solving socially significant problems (Makulbayeva and Sharipova, 2024).

Current research shows that civic responsibility is measured through various indicators, including participation in elections, a sense of ability to influence decisions, trust in state institutions, and membership in public organizations. In Kazakhstan, there is growing interest in direct citizen participation in governance and local issues, which is reflected in the high turnout in local elections and the activity of public councils. International experience also emphasizes the importance of citizen involvement in decision-making processes and the need to strengthen the trust between society and state institutions.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Socio-political approach

As its main approach, this study utilizes socio-political analysis, which fits the aim of investigating how social factors affect the political activity and behavior of Kazakhstan’s youth. Firstly, sociopolitical analysis allows researchers to explore the interplay between social factors and dynamics in the political activity of Kazakhstan’s youth. Young people are not only shaped by their individual experiences, but also by the broader societal norms, values, and institutions that govern their lives. By examining factors such as socioeconomic status, education, cultural background, and community engagement, researchers can gain insights into how these elements affect young people’s political beliefs, behaviors, and participation levels. Secondly, the political landscape of Kazakhstan (or any other country), including its governance, policy frameworks, and historical context, significantly impacts youth political activity. Understanding Kazakhstan’s political environment, such as the presence of democratic institutions, political repression, or active civil society organizations, enables researchers to reveal and analyze the motives for youth’s political participation and the level of youth’s political activity.

One way to implement socio-politics is the application of Political Socialization Theory, which provides a framework for understanding how young people in Kazakhstan develop their political attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. This type of analysis is chosen because it can highlight several key aspects of political activity among youth in Kazakhstan.

Applying socio-political analysis reinforces the practical significance of the study, since it is expected to contribute to more effective strategies for fostering civic engagement among youth in Kazakhstan.

3.2 Estimation model

Three variables (political culture, transforming activity, and political life participation) were defined for this study, and Structural Equation Modeling was employed to assess the degree of fit between the model and the dataset, and concurrently examine the interconnections among several variables. Transformative activities serve as mediators between political culture and involvement. Initially, a measurement model was created and verified, followed by an evaluation of the structural model and determination of various path estimations. The postulated correlations between the various variables are depicted in the measurement model.

3.3 Sample characteristics

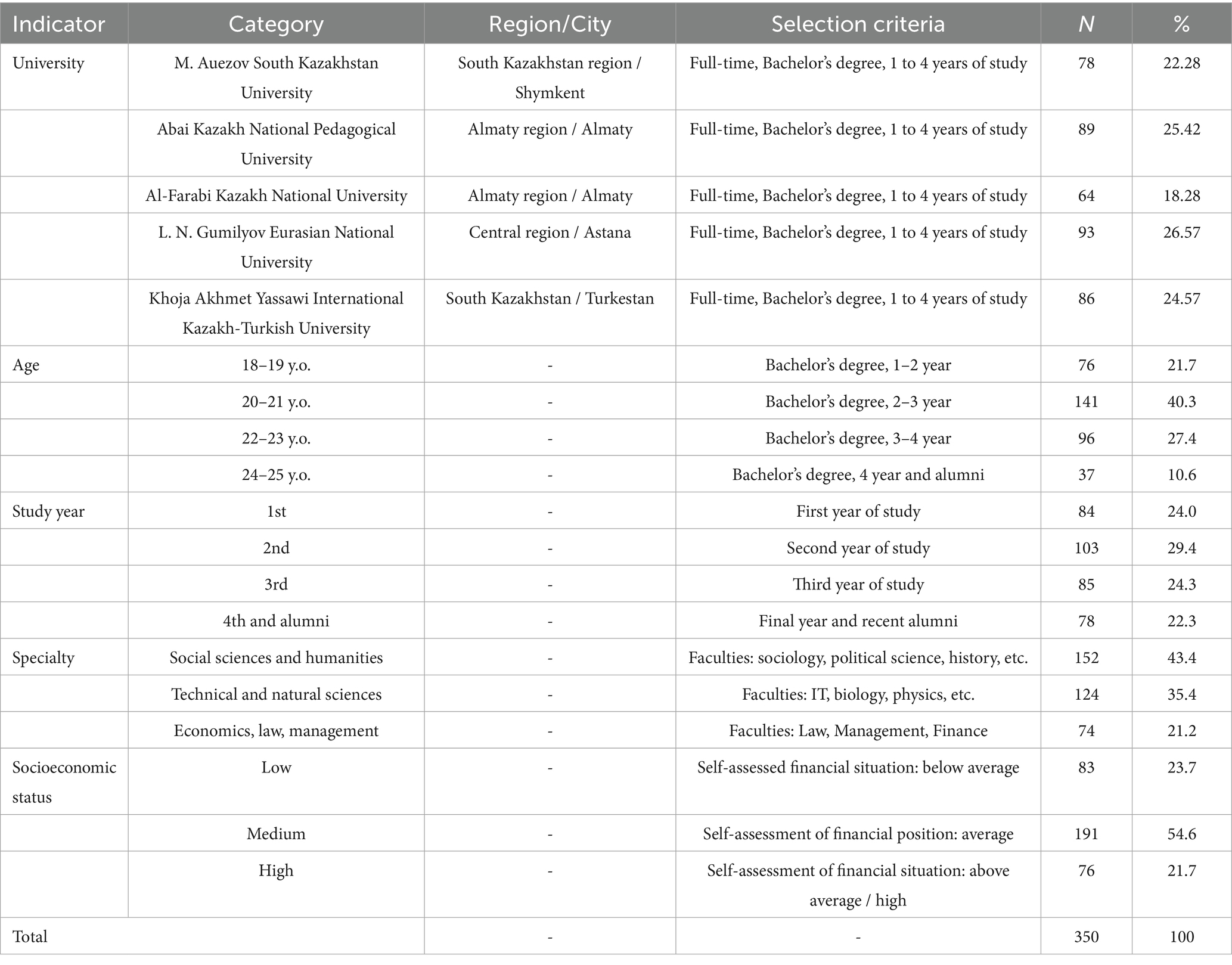

The data on the demographic characteristics of the sample surveyed, which consisted of 350 participants, provided a comprehensive background of age group, gender ratio, institution, and level of education among the respondents. The largest group with respect to the Age Distribution is within 23–27 years with 39.71% shareholding the majority followed by 27–32 at 34.85%. It can infer that most participants were probably undergraduates or early-stage postgraduates, while those below 22 and above 32 accounted for 16.00 and 9.44%, respectively. The Gender Distribution showed a small preponderance of males (56.85%, male respondents versus female respondents), with slightly lower percentage—only (46.15%) pointing to an equal but male-oriented selection bias in this sample. The sample parameters are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics and structure of the respondent sample (Created by authors).

Since many young people are acting as students or have recently graduated, the study indicates the universities from which the participants are currently studying or have graduated. However, the study does not distinguish graduates from acting students nor are grades indicated, because political activity is not expected to be influenced by the aforementioned parameters any more than by participants’ age in general. However, the university itself can be a factor affecting the political activity or attitude of individuals, since universities usually form their students’ worldview due to certain ideological traditions or political adherence in the institution. As a result, five universities in Kazakhstan were selected for this study.

L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University has the highest participation percentage at 26.57% among the five major universities listed on Institution’s list, closely followed by Abai Kazakh National Pedagogical University with 25.42% as well and Khoja Akhmet Yassawi International Kazakh-Turkish University having 24.57%. M. Auezov South Kazakhstan University and Al-Farabi Kazakh National University supply 22.28 and 18.28%, respectively, which means that there was a good mix of students’ and graduates’ representation from every institution.

3.4 Pre-testing of the instrument

A detailed inventory of objects related to each dimension was compiled, including data from five focus group discussions conducted between May and June of 2024. The initial survey included 20 participants from each category. The questionnaire was developed by reviewing existing studies on political participation (Literat and Kligler-Vilenchik, 2021; Rainsford, 2017; Tham and Wong, 2023; Sairambay, 2022b), patriotism (Schatz et al., 1999), and civic responsibility (Blais and Galais, 2015). Subject matter experts were consulted to authenticate the accuracy, coherence, and comprehensibility of the questionnaire (see the Appendix). A preliminary assessment was conducted on a sample of 25 young people who had studied or graduated from five universities. A total of 26 items were retained from the original collection of 35 items, while the rest were eliminated because of their irrelevance and redundancy. Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale consisting of five points, with 5 representing ‘strongly agree’ and 1 representing ‘strongly disagree’. To assess dependability, item analysis was conducted. This analysis revealed that all dimensions had positive correlations between their respective items, except for one item pertaining to political culture, transforming activities, participation in political life, patriotism, and civic responsibility. Consequently, these items were excluded from analysis. In addition, the presence of positive items with a total correlation and a high Cronbach’s alpha value (above 0.80) suggests that the measuring scale has good reliability, as demonstrated by Raykov et al. (2024).

3.5 Sampling design

This study is characterized by its descriptive nature. This study was conducted among young people in Kazakhstan. Data were collected from 350 young people who are currently studying or have graduated from five universities in Kazakhstan; online questionnaires and quota sampling were used in data collection to ensure representative participation. A quota sampling method was used to increase the probability of obtaining as many respondents as possible. With regard to sample size, this study used G*Power (HHU, 2024). Thus, the analysis of the G*Power study showed that 800 was sufficient to achieve a test power of 90%. Therefore, it can be concluded that the sample size was appropriate according to these standards.

Although our sample included only students, this category represents a socially and politically active segment of Kazakhstani youth (OECD, 2022; Zhampetova et al., 2024). According to the Statistics Committee of the Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan in 2023, more than 60% of young people aged 18 to 25 are enrolled in the higher education system (UNICEF, 2023). Students are one of the groups most involved in digital and socio-political interactions, demonstrating a willingness to participate in both institutional and informal forms of participation. Thus, the sample reflects the current behavioral and value attitudes of a significant portion of Kazakhstani youth.

The sample was formed using stratified purposive sampling to ensure territorial, cultural, and educational diversity. To achieve regional and socio-cultural balance, this study purposefully selected full-time undergraduate students from five leading state universities in Kazakhstan, representing the key socioeconomic and cultural macro-regions of the country. These educational institutions were selected based on the following criteria.

3.5.1 Geographical and cultural representation of the regions of Kazakhstan

M. Auezov South Kazakhstan University (Shymkent) and Khoja Akhmet Yassawi International Kazakh-Turkish University (Turkestan) present the South Kazakhstan region characterized by high-density youth, ethnocultural diversity, and active migration.

Abai Kazakh National Pedagogical University and Al-Farabi Kazakh National University are located in Almaty, the country’s largest metropolis, and a hub for civic activism, digital initiatives, and the NGO sector, making the Almaty region strategically important for the study of civic and political engagement.

L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University (Astana) is the leading university in the central region, located in the capital, where government bodies, international organizations, and elements of emerging civil infrastructure are concentrated.

3.5.2 The strategic importance of universities as centers of political socialization

All five universities are among the top 10 leading state universities in Kazakhstan in terms of student numbers and academic reputations. They have active student councils, debate clubs, and youth organizations that create an environment for the formation of political culture, civic responsibility, and the transformative participation of young people.

3.5.3 Sociological and ethno-confessional heterogeneity

These universities provide coverage of young people with different ethnic, linguistic, religious, and social backgrounds, which makes it possible to analyze political engagement in the context of diversity. This is especially important for Kazakhstan, where political behavior depends on regional identity, interpersonal language, and cultural affiliation.

3.5.4 Logistical feasibility and access to respondents

Universities were also selected based on their institutional willingness to cooperate: administrative support, access to student audiences, and adherence to ethical standards for data collection. This ensured a high proportion of valid responses and minimized the selection bias.

Full-time students were included in this study. The selection took into account the following parameters: gender, age, year of study, and field of study (social sciences, technical, and economic-legal disciplines), which allowed for internal heterogeneity and analytical depth.

3.6 Sampling method

This study used a quota sampling method to ensure the representativeness of the key subgroups of young people studying in higher education institutions in Kazakhstan. Quotas were formed based on demographic and educational characteristics relevant to political participation, including the following:

3.6.1 Gender

According to the Committee on Statistics of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2023), the gender ratio of undergraduate students in Kazakhstan is approximately 50/50. Therefore, the sample had a gender proportion of 52 per cent females and 48 per cent males.

3.6.2 Age

The age range of the quota was determined based on the age category of full-time students (bachelor’s degree), which is the core of Kazakhstani youth and covers the most active phase of political socialization. More than 90% of university students fall within this range, according to the statistics from the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

3.6.3 Region

HEIs from the Southern, Central and Almaty regions of Kazakhstan, which provide wide socio-cultural coverage, were included. The number of participants from each region was selected in proportion to the number of students studying at the respective HEIs (e.g., L. N. Gumilyov ENU in Astana, Abai KazNPU in Almaty, etc.).

3.6.4 Year of study

Course quotas were introduced to analyze possible age-academic differences in political attitudes and participation levels. The sample was representative of all undergraduate courses, including graduates, with an approximately even distribution.

3.6.5 Field of study

To ensure professional and educational diversification, the sample respected the distribution of students in the main academic blocks: humanities, STEM sciences, and the field of management/law. This reflects the structure of university training in the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Thus, the quotas were based on official demographic and educational data, which allowed for a balanced representation of different subgroups of young people within the student population. This approach strengthens the internal validity of the study and provides grounds for analytical (but not statistical) generalizability of the results.

3.7 Recruitment procedure and response rate

Study participants were selected within predetermined quotas based on socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age, region, course of study, and field of study), which was in line with the quota stratified sampling strategy. The recruitment process occurred in three stages.

3.7.1 Organizational stage

Formal contact was made with the administrations and student departments of five public universities representing the key macro-regions of Kazakhstan. The universities agreed to conduct the survey in an online format among full-time undergraduate students.

3.7.2 Recruitment of participants

Students were informed about the aims and conditions of the study through mailing on university email groups and messengers (Telegram, WhatsApp), announcements on Moodle platforms and university portals, and through academic group supervisors and student councils.

Informed online consent was built into the questionnaire to confirm the voluntariness of participation and confidentiality of the data.

3.7.3 Data collection and sorting

A total of 500 invitations were sent out.

Of these:

• 372 respondents completed the questionnaire in full (response rate: 74.4%),

• 22 questionnaires were excluded at the pre-processing stage due to incomplete data or logical inconsistencies (e.g., simultaneous indication of incompatible responses).

The final sample was N = 350 valid observations, which met the minimum sample size norms for structural modeling in social sciences.

Methodological Rationale:

• A response rate of 74.4% is considered high for online surveys, especially among young people, and indicates interest and accessibility of respondents (Dillman et al., 2014).

• The use of formal recruitment channels and university-by-university controls minimized distortion through self-selection and increased the internal validity of the study.

• Ensuring anonymity, voluntariness, and a lack of academic participation contributed to the reliability of the data.

3.8 Measurement model assessment

Control variables were included to increase the precision of the analysis and account for background factors that may influence the relationship between political culture and political participation. This is consistent with the sociopolitical research approach and international practice in modeling youth political behavior (Inglehart and Norris, 2019; OECD, 2022). Our study included the following variables.

Gender differences in the forms and levels of political participation have been widely documented in the literature (Brady et al., 1995; Weldon, 2006). Women are more likely to participate in volunteer and socially oriented initiatives, whereas men are more likely to participate in protests and political acts. Taking gender into account allowed us to reflect on the possible differentiation of participation patterns.

Age is an indicator of the life cycle of political socialization: younger respondents (18–20 years old) are more likely to form political views, while older respondents (22–25 years old) have more experience of participation and informational influence.

Territorial context (region by university) influences access to political and civic institutions. The inclusion of a regional factor allows for institutional differences among metropolitan, regional, and cross-border universities.

Year of study is seen as a proxy variable for academic and developmental age-related increases in knowledge, social maturity, and engagement.

Students of different specialties, in particular, humanities and social science, tend to have greater awareness of political issues, whereas technical and economics majors are more likely to demonstrate distance from formal political discourse (Dalton, 2019).

Socioeconomic status (SES) was introduced as a control variable and categorized into three levels (low, average, and high) based on the self-assessment of the family’s financial situation. Its inclusion was justified for the following reasons:

006F; SES is closely related to the resource-based model of political participation (Brady et al., 1995), according to which participation depends on the availability of time, money, skills, and access to information.

006F; Youths from families with high SES are more likely to have access to better education, digital platforms, and international programmes, all of which contribute to the development of political culture and civic responsibility.

006F; The analysis revealed that respondents with high and average SES demonstrated a higher level of involvement in non-institutional forms of participation (discussion clubs, online petitions, and volunteering), while young people with low SES were more often either politically passive or limited to formal participation (pledge voting).

Thus, SES acts not only as a background factor, but also influences the mechanism of translation of political attitudes into behavior. This should be considered when interpreting differences in participation levels and developing recommendations to increase participation among socially vulnerable groups.

3.9 Ethical consideration

International research ethics guidelines state that not all studies need formal ethics committee approval, especially if they do not involve interventions, collect identifiable data, and include vulnerable groups, posing no risks to participants. These studies are often categorized as minimal-risk research and may be exempt from committee submission if allowed by the institution. Key documents supporting this include the Belmont Report (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1979), which permits exemptions for minimal-risk research, and the OECD Guidelines on Research Ethics (OECD, 2021), which recognize exemptions for low-risk, non-invasive anonymous research. The University of Oxford’s CUREC Guidance (University of Oxford, 2022) also states that anonymous online surveys without sensitive data are exempt from mandatory ethics review as long as ethical standards are met. The study described met the criteria for minimal risk research since it was fully anonymized, did not involve vulnerable participants, and was based on voluntary consent, aligning with the guidelines (OECD, 2021; BERA, 2018) emphasizing voluntariness, confidentiality, and informed consent.

4 Results

4.1 Measurement model assessment

The analysis began with examining the descriptive statistics of all the constructs. Examination of response patterns revealed that Political Culture (PC) items showed high mean values ranging from 4.205 to 4.265, with negative skewness (−1.062 to −1.206), indicating responses tending toward the higher end of the scale. Political Life Participation (PP) items similarly demonstrated high means (4.030 to 4.182). Transforming Activities (TA) items showed moderate means (3.226 to 3.355) with relatively normal distribution, as indicated by lower skewness values (−0.165 to −0.288). Notably, both Patriotism (PAT) and Civic Responsibility (CR) items displayed high means (PAT: 4.287 to 4.325; CR: 4.156 to 4.203), suggesting strong patriotic feelings and a sense of civic duty among respondents.

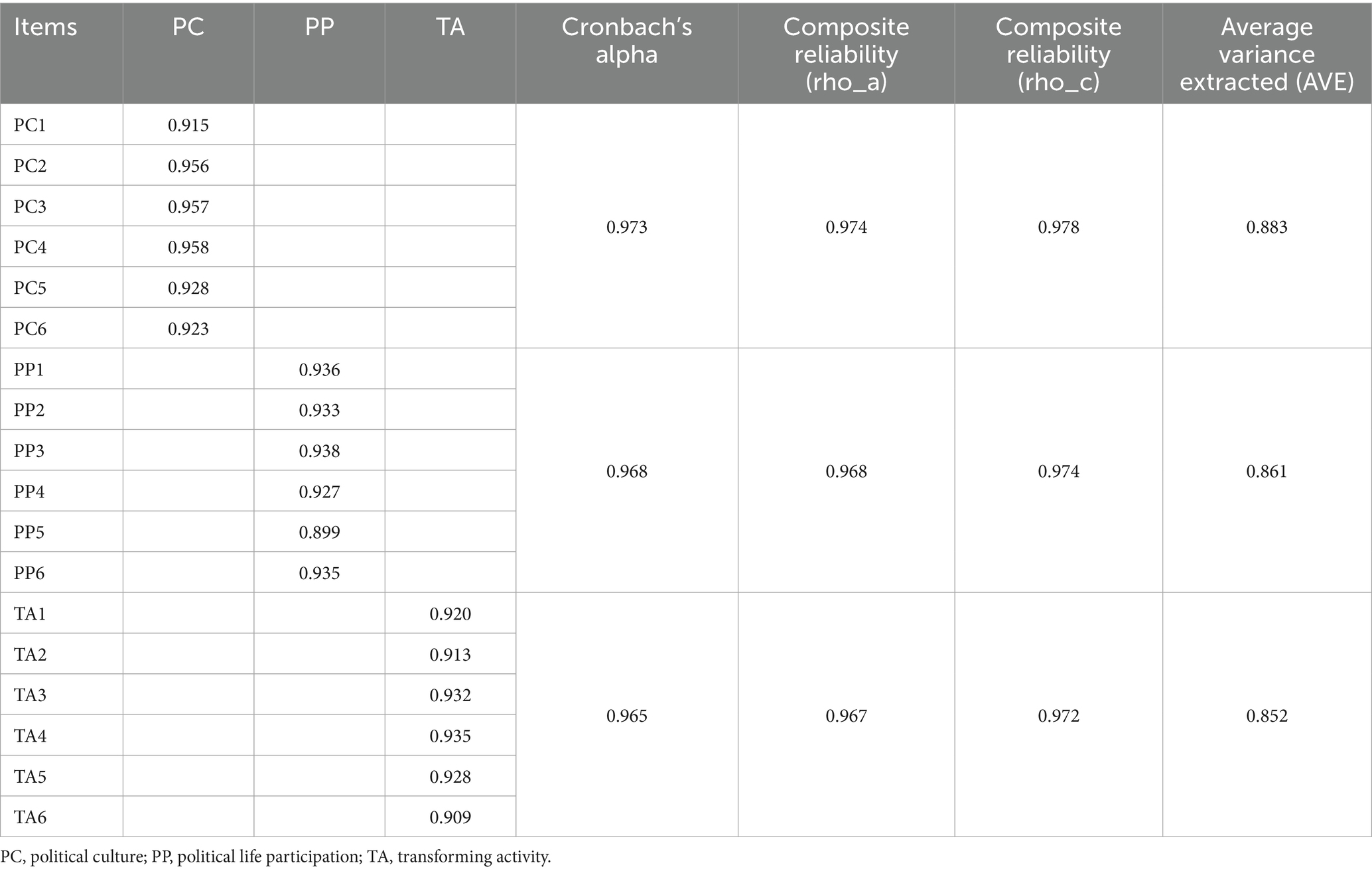

The reliability and validity of the measurement model were assessed using multiple criteria (Table 2). All constructs demonstrated excellent reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha values being well above the recommended threshold of 0.70. Political Culture had the highest reliability (α = 0.973), followed by political life participation (α = 0.968), patriotism (α = 0.965), civic responsibility (α = 0.962), and transforming activities (α = 0.865). The factor loadings for all items were satisfactory, with PC items ranging from 0.915 to 0.958, PP items from 0.899 to 0.938, TA items from 0.709 to 0.735, PAT items from 0.932 to 0.945, and CR items from 0.928 to 0.942. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values exceeded the 0.50 threshold for all constructs, ranging from 0.652 for transforming activities to 0.895 for patriotism, indicating strong convergent validity.

4.2 Discriminant validity

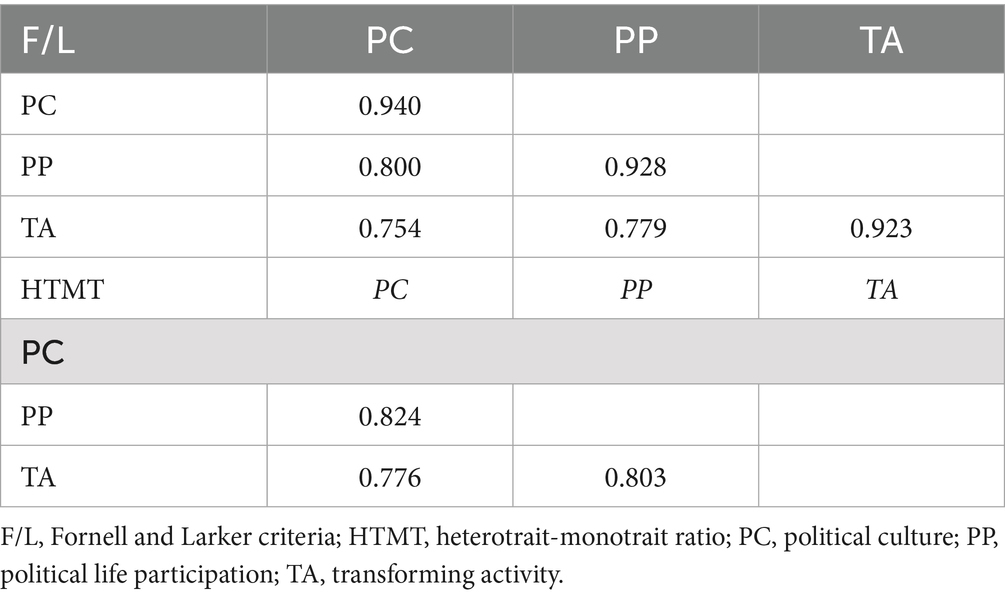

Table 3 presents the discriminant validity assessment using both the Fornell-Larcker criterion and HTMT ratio. The Fornell-Larcker criterion shows that the square root of the AVE for each construct (diagonal values) exceeds its correlations with other constructs. For instance, political culture’s AVE square root (0.940) was greater than its correlations with other constructs (ranging from 0.086 to 0.800). Notably, the correlation between political culture and transforming activities was quite low (0.086), whereas political culture showed stronger correlations with patriotism (0.685) and civic responsibility (0.612). The HTMT ratios all fell below the conservative threshold of 0.85, with values ranging from 0.092 to 0.824, further confirming discriminant validity.

To ensure that no multicollinearity issues existed between the predictor variables, we calculated the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for all structural model relationships. The VIF values for predictor relationships were all well below the conservative threshold of 3.3, with political culture to political life participation showing a VIF of 2.14, political culture to transforming activities showing a VIF of 1.68, and transforming activities to political life participation with a VIF of 1.75. For the moderating effects, the political culture × patriotism interaction term showed a VIF of 2.27, while the political culture × civic responsibility interaction term had a VIF of 2.03. These values indicate the absence of multicollinearity concerns in our structural model, as all values were substantially below the recommended maximum threshold of 5.0, confirming that predictor variables were sufficiently distinct and did not exhibit problematic levels of correlation that could distort the analysis results. These comprehensive assessments of the measurement model provide strong evidence of construct reliability and validity, allowing us to proceed with confidence in the hypothesis testing. The following section presents the results of the structural model assessment and hypothesis testing.

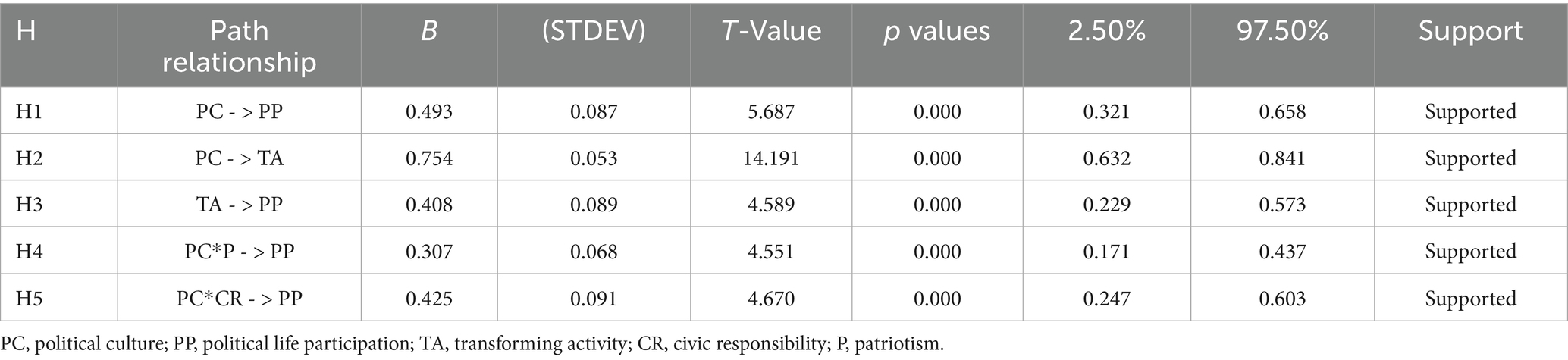

4.3 Hypothesis testing results

The structural equation model demonstrated an excellent fit to the data, as evidenced by the multiple fit indices. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was 0.958 and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) was 0.951, both exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.95, indicating an excellent fit. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.043 (90% CI [0.037, 0.049]), well below the acceptable threshold of 0.08, suggesting good fit. Additionally, the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.032, which is considerably below the recommended cutoff of 0.08. The chi-square test (χ2 = 742.36, df = 365, p < 0.001) was significant, which is common in large samples; however, the ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom (χ2/df = 2.03) was below 3.0, further supporting a good model fit. Collectively, these results indicate that the hypothesized model appropriately represents the relationships among the variables under investigation.

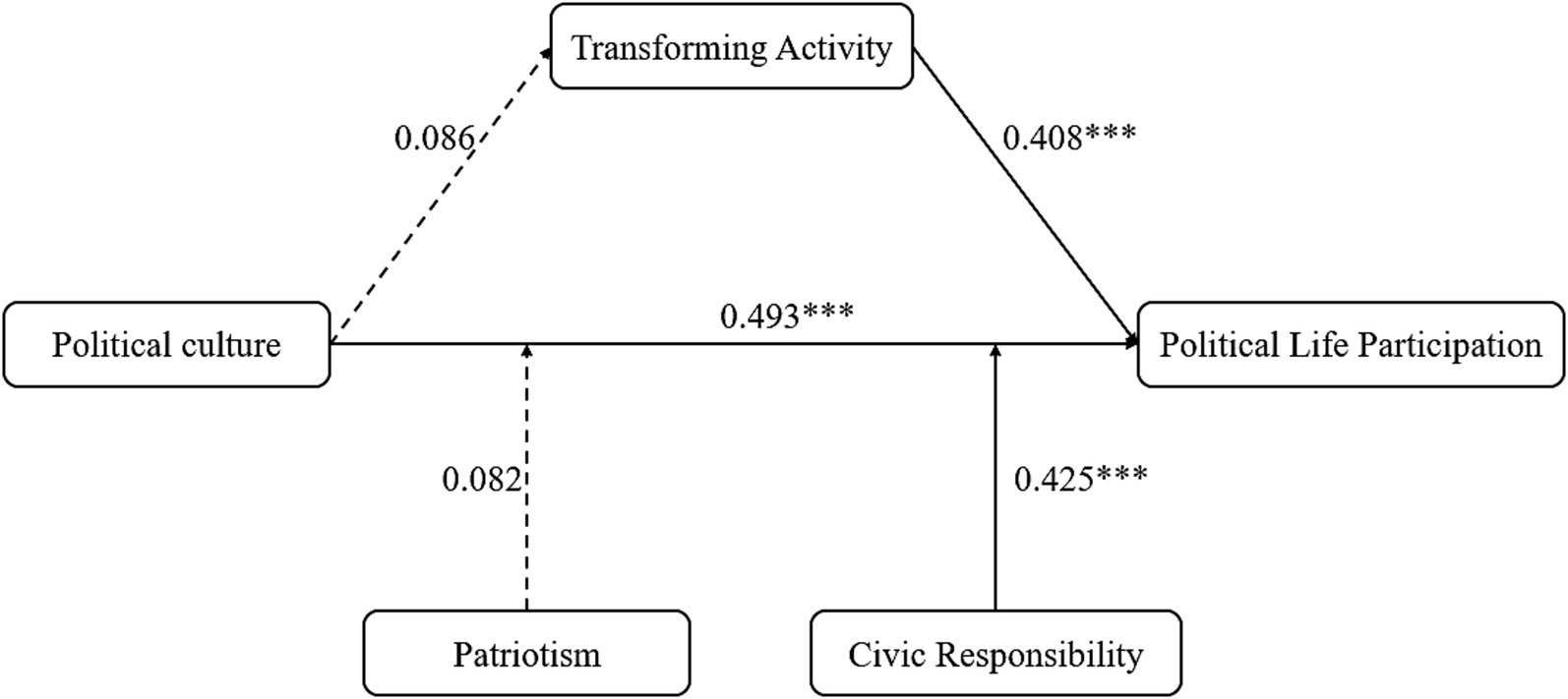

The results of our hypothesis testing are presented in Table 4 and illustrated in Figure 1. Political Culture has a significant positive influence on Political Life Participation (β = 0.493, p < 0.001, CI: 0.321 to 0.658), supporting H1. This indicates that Kazakh youth with stronger democratic values and an understanding of political systems are more likely to engage in political activity. Similarly, Transforming Activities demonstrate a significant positive effect on Political Life Participation (β = 0.408, p < 0.001, CI: 0.229 to 0.573), supporting H2, suggesting that youth who engage in activities aimed at social and political change are more likely to participate in formal political processes. However, contrary to our expectations, the relationship between Political Culture and Transforming Activities was not significant (β = 0.086, p = 0.351, CI: −0.094 to 0.266); thus, H3 was not supported. This finding suggests that strong democratic values do not lead Kazakh youth to engage in transformative activities, reflecting a cultural preference to participate in existing political frameworks rather than seeking system-level changes.

Figure 1. Results of structural equation modeling showing standardized path coefficients and significance levels (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; −-- = not significant).

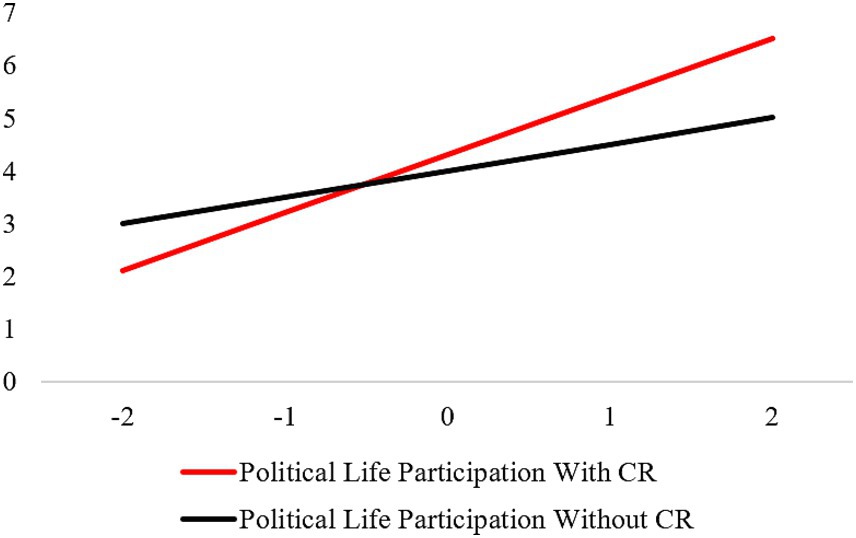

The analysis of the moderation hypotheses revealed interesting patterns. The interaction between Political Culture and Patriotism (H4) was not significant (β = 0.082, p = 0.384, CI: −0.102 to 0.266), indicating that patriotic feelings do not strengthen or weaken the relationship between political culture and participation. This suggests that while Kazakh youth may have strong patriotic feelings, these feelings do not influence how their political culture translates into actual participation. However, Civic Responsibility showed a significant moderating effect (β = 0.425, p < 0.001, CI: 0.247 to 0.603), supporting H5. As shown in Figure 2, when Kazakh youth have a strong sense of civic duty, the positive influence of political culture on political participation becomes even stronger. In other words, understanding one’s civic responsibilities appears to be a crucial factor in converting democratic values into political engagement.

Figure 2. Interaction effect of civic responsibility on the relationship between political culture and political participation, demonstrating how civic responsibility strengthens the influence of political culture on participation levels.

Figure 2 illustrates the moderating effect of civic responsibility on the relationship between political culture and participation. The graph shows two distinct slopes: one representing the relationship between political culture and participation when civic responsibility is present (steeper slope) and the other when it is absent (flatter slope). This visualization clearly demonstrates that the positive relationship between political culture and political participation becomes stronger in the presence of civic responsibility, suggesting that a sense of civic duty enhances the translation of political-cultural values into actual political participation among Kazakh youth.

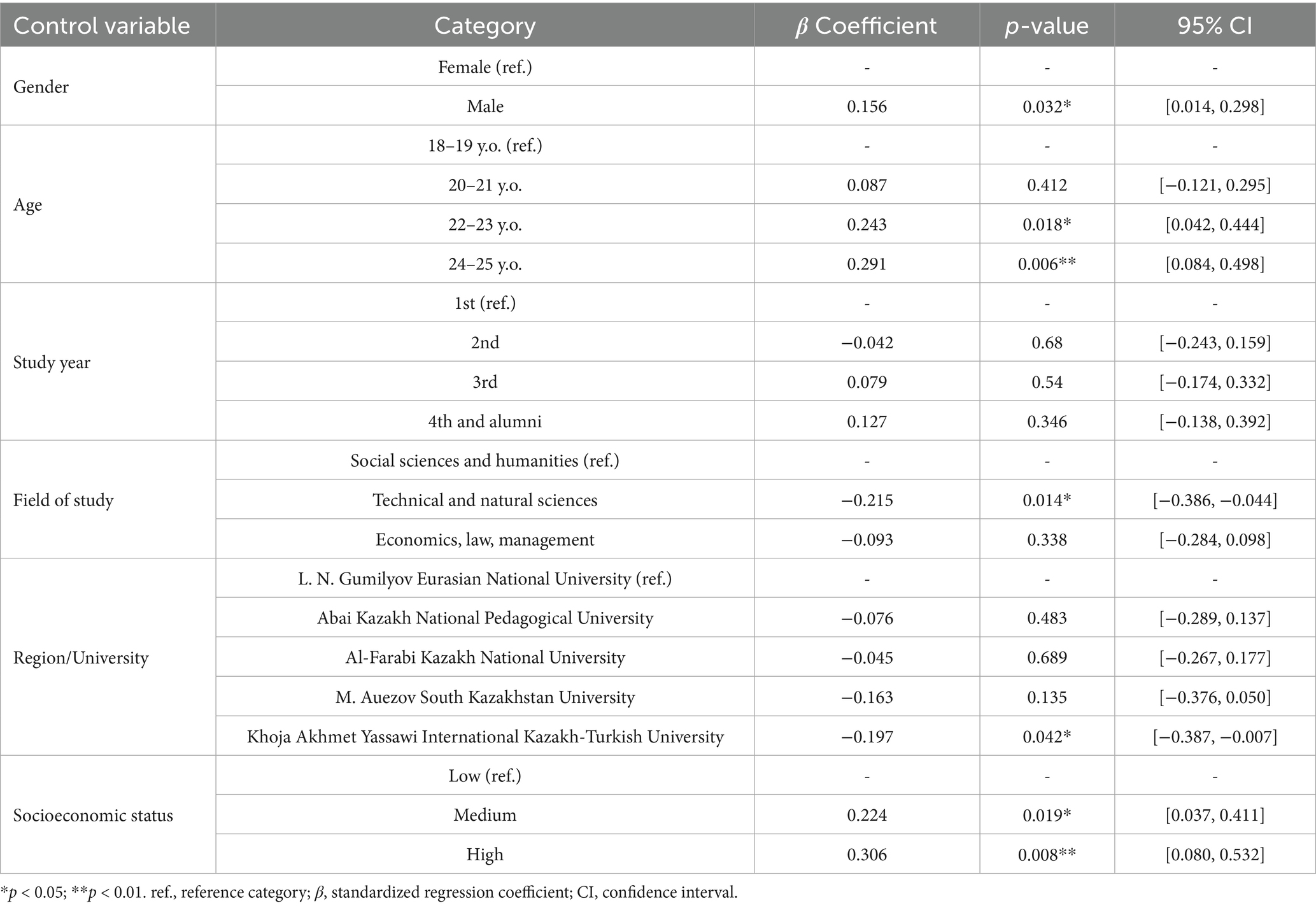

The analysis of the control variables reveals significant demographic influences on political participation among Kazakh youth, as shown in Table 5. Gender differences were evident, with male students showing higher participation than female students (β = 0.156, p = 0.032). Age emerged as a significant factor, with older students (22–23 and 24–25 age groups) demonstrating progressively higher participation levels, suggesting that political engagement increases with maturity. Academic discipline plays a role, as students in technical fields participate less than their social sciences peers (β = −0.215, p = 0.014). Regional variations are modest, with only students from Khoja Akhmet Yassawi International Kazakh-Turkish University showing significantly lower participation. Most notably, socioeconomic status demonstrated a clear graduated effect, with medium (β = 0.224, p = 0.019) and especially high SES students (β = 0.306, p = 0.008) participating more actively than those from lower economic backgrounds. These findings complement those of the main study by highlighting how demographic and contextual factors shape political engagement patterns.

Our findings reveal that young Kazakhs with stronger democratic values (political culture) are significantly more likely to participate in political life (H1), yet this does not translate into seeking systemic change through transformative activities (H3 is not supported). This suggests that Kazakh youth prefer to work within existing institutional frameworks rather than challenging them, a crucial insight for an emerging democracy where stability and institutional development often take precedence over radical change. While those who engage in transformative activities show increased political participation (H2), the missing link between political culture and transformative activities highlights a pragmatic approach to democratic engagement that respects established structures, while promoting greater participation.

Perhaps the most revealing is the differential impact of patriotism versus civic responsibility. While patriotic sentiment—often emphasized in post-Soviet states—does not significantly affect how youth translate their democratic values into action (H4 is not supported), a strong sense of civic duty dramatically enhances this relationship (H5). This finding challenges conventional approaches to youth engagement in Kazakhstan and similar emerging democracies, suggesting that fostering a sense of civic responsibility and duty toward democratic processes may be more effective than appealing to patriotic sentiments. The resulting narrative highlights the youth who value democracy, prefer institutional engagement over transformation, and are motivated more by civic duty than by national attachment. These insights that offer a clear direction for policymakers seeking to strengthen democratic participation in Kazakhstan’s unique political context.

5 Findings and discussion

The findings of this study provide important insights into the dynamics of political participation among the Kazakh youth. Our results confirm the significant role of political culture in shaping political participation (H1), aligning with previous research that emphasizes how cultural values and understanding of political systems influence engagement in democratic processes (Кuanyshbayeva et al., 2021; Almond and Verba, 1963; Elsässer and Schäfer, 2023). This direct relationship between democratic values and participation is consistent with findings from other emerging democracies, such as Ukraine and Georgia, where democratic values have similarly been shown to drive youth engagement (Tzankova et al., 2022). In Kazakhstan’s context, where democratic institutions are still evolving, fostering democratic values could enhance youth participation in political life.

The positive relationship between transforming activities and political participation (H2) indicates that youths who engage in change-oriented activities are more likely to participate in formal political processes. This finding supports previous research on youth political activism (Tzankova et al., 2022; Chernov, 2021) and extends our understanding of how different forms of political engagement interact in Kazakhstan’s unique political environment. Similar patterns have been observed in Poland and Hungary, where youth engagement in civil society activities correlates with increased formal political participation, suggesting a common pathway for political engagement across post-communist contexts (Janmaat and Hoskins, 2021).

However, our study revealed that political culture does not necessarily lead to transforming activities among Kazakh youth (H3 is not supported), suggesting a preference for working within existing political frameworks rather than seeking systemic changes. This finding contrasts with Western studies, which often link democratic values to reform-oriented activities (Meyer, 2021). Unlike Western democracies, Kazakh youth appear to separate their beliefs from transformative actions. This disconnect reflects Kazakhstan’s distinct post-Soviet political environment, in which institutional stability is highly valued after decades of uncertainty following independence. This preference for institutional engagement over transformation differs from patterns observed in emerging Latin American democracies such as Brazil and Chile, where democratic values more commonly translate into reform-oriented activism (Zarate-Tenorio, 2023), highlighting the importance of regional and historical contexts in shaping youth political behavior.

The contrasting results regarding our moderation hypotheses reveal a compelling story about what motivates political participation among the Kazakh youth. The non-significant moderating effect of patriotism (H4 not supported) challenges the conventional assumptions about the role of national attachment in political participation. While previous research has suggested that patriotic sentiments enhance political engagement (Alexeev and Pyle, 2023), our findings indicate that in Kazakhstan, the relationship between political culture and participation operates independently of patriotic feelings. This pattern has been observed in other post-Soviet states, such as Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan (Burkhanov and Collins, 2019), suggesting a regional trend in which patriotism focuses more on cultural identity and national unity than on civic participation.

The significant moderating role of civic responsibility (H5 supported) is perhaps the most important finding in understanding youth engagement in Kazakhstan. This result aligns with and extends previous research on civic duty and political participation (Reuter, 2020), suggesting that a sense of civic responsibility is crucial for translating democratic values into actual political engagement. This finding echoes similar results from studies in Estonia and Lithuania, where civic consciousness has been shown to be a stronger predictor of political participation than national sentiment (Huddy et al., 2021). In Kazakhstan’s context, this finding is particularly important as it suggests that developing civic consciousness might be more effective in encouraging youth political participation than focusing on patriotic education.

Taken together, these findings tell a compelling story about what drives political participation among Kazakh youth in emerging democracies. Young Kazakhs with democratic values actively participate in political life but prefer to work within existing institutional frameworks rather than pursuing transformative change. Their engagement is primarily motivated by a sense of civic duty rather than patriotic sentiments. This pattern of politically engaged youth who value both democracy and stability reflects Kazakhstan’s unique position as an emerging democracy that navigates the complex legacies of its Soviet past while developing its own democratic traditions.

5.1 Theoretical contributions

This study makes several important theoretical contributions to our understanding of political participation, particularly in emerging democracies. First, it extends Political Socialization Theory by demonstrating how different factors interact in shaping youth political participation in a post-Soviet context. While traditional applications of the theory emphasize the role of socialization agents, such as family and education (Hyman, 1959), our findings reveal that the relationship between political culture and participation is more complex and is significantly moderated by civic responsibility but not by patriotic sentiments. This nuanced understanding helps to refine the application of Political Socialization Theory in non-Western contexts.

Second, it contributes to the literature on political culture by challenging the assumed relationship between democratic values and transformative activities. Previous theoretical frameworks often suggest that strong democratic values lead to reform-oriented activities (Meyer, 2021). However, our findings indicate that, in Kazakhstan’s context, youth with strong democratic values may choose to work within existing systems rather than pursue transformative change. This insight enriches our theoretical understanding of how political culture operates in emerging democracies, suggesting that the relationship between democratic values and political action may be more context-dependent than previously theorized.

Third, this study advances our theoretical understanding of the roles of patriotism and civic responsibility in political participation. By distinguishing between these two constructs and examining their moderating effects separately, we demonstrated that civic consciousness, rather than emotional attachment to the nation, plays a crucial role in translating political culture into participation. This finding contributes to ongoing theoretical debates on the relative importance of affective versus duty-based motivations in political behavior (Reuter, 2020).

5.2 Policy recommendations

An analysis of Kazakhstan’s youth political engagement shows important changes in how they participate in and view politics. Our research indicates that while young people are getting involved in public initiatives, their participation in traditional political activities, such as elections and parties, is still low. This suggests the need to update educational and institutional strategies to better involve the youth in democracy.

5.2.1 Strengthening civic responsibility through education

Modern research emphasizes the importance of developing civic responsibility among young people. Young people are active in public initiatives aimed at solving social problems such as the fight against vandalism and illegal dumping. This indicates a high level of civic responsibility and young people’s readiness to participate actively in public life. Should incorporate civic education into their programs to foster critical thinking, understanding democracy, and social responsibility. These may include practical exercises, debates, participation in social projects, and volunteer activities.

5.2.2 Developing political literacy and engagement

Young people in Kazakhstan are interested in politics but mostly participate in online discussions. This demonstrates the need for better political literacy and opportunities for deeper involvement. To address this, state authorities and civil society should create programs to improve political understanding among youth, such as youth parliaments, educational events, training sessions, and forums, as well as using digital platforms to share information and encourage discussion.

5.2.3 Institutional mechanisms for youth participation

Current initiatives demonstrate strong youth activism in tackling social issues. However, to enhance their engagement in politics, we need to establish systems that allow youth to participate in decision-making. Suggested measures include creating youth advisory councils for government bodies, expanding youth parliament programs, and establishing platforms for discussing and implementing youth initiatives. These steps will provide young people with the opportunity to influence decision-making processes and increase their involvement in the country’s political life.

5.2.4 Using digital platforms for political engagement

It is recommended that strategies be developed to use digital platforms to increase political literacy, organize online discussions, conduct surveys, and engage young people in discussions on current political issues. This will enable young people to become more politically engaged and to express their views on important issues.

Thus, trends in the political participation of Kazakhstan’s youth emphasize the need to adapt educational, institutional, and digital approaches to better engage the youth in democratic processes. The implementation of the proposed recommendations will strengthen civic responsibility, increase political literacy, and create conditions for the active participation of the youth in the political life of Kazakhstan. However, these online initiatives should be designed to complement traditional forms of political participation rather than replace them.

6 Conclusion

This study advances our understanding of youth political participation in emerging democracies by revealing the complex interplay between factors influencing Kazakh youth engagement. Rather than simply participating in or abstaining from politics, we discovered that young Kazakhs navigated democratic engagement through a nuanced approach that reflected their country’s unique post-Soviet context. The preference for institutional engagement over transformative approaches challenges Western-centric assumptions about youth political behavior and suggests that emerging democracies may develop distinct participation patterns shaped by their historical and cultural contexts.

The finding that civic responsibility, not patriotism, strengthens the relationship between political culture and participation represents a paradigm shift in youth engagement strategies in Kazakhstan and potentially other post-Soviet states. This insight suggests that democratic development efforts should focus on building civic consciousness rather than relying on nationalist sentiments—a significant departure from traditional approaches in the region. Moreover, the disconnect between democratic values and transformative activities indicates that Kazakh youth prioritize stability and incremental change within existing systems, reflecting a pragmatic approach to democratic participation that balances aspirations for greater democracy with concerns for institutional continuity.

6.1 Limitations

Despite the importance of these findings, several limitations may affect their validity and universality.

6.1.1 Sample size and demographic representation

The study involved 350 respondents from five major universities in Kazakhstan, which is adequate for structural equation modeling but may not represent the country’s diverse youth. Since the focus was on university students, it excluded many young people, such as vocational students or working youth, whose political views may differ significantly.

6.1.2 Cross-sectional design

This study used a cross-sectional design, which limits its ability to establish causal relationships between political culture, civic responsibility, patriotism, and political participation. While structural equation modeling tests variable relationships, it does not track changes in youth political attitudes and behaviors over time. Political participation evolves and is influenced by various events. A longitudinal study would better capture how youth political participation changes, and the factors that drive these changes.

6.1.3 Geographical and institutional bias

The study surveyed respondents from five large universities in major Kazakh cities: Almaty, Shymkent, and Astana, which are known to have higher levels of youth political activity and better educational resources. This focus may not represent youths from rural areas with limited access to these resources. Consequently, the findings might be biased toward more politically active and aware youths, reducing their applicability to the broader youth population across the country.

6.1.4 Socially desirable behavior

These results may be affected by the social desirability effect, causing respondents to exaggerate their political involvement to meet social expectations, which reduces data accuracy. Combining self-reports with objective measures such as participation in events or voting could provide a clearer picture of political engagement.

6.1.5 Cultural and contextual specificity

While this study offers useful insights into political participation in Kazakhstan, the results may not apply to other post-Soviet or developing democracies with different political structures and histories. Kazakhstan’s specific socio-political factors, including Soviet legacy, can influence youth political participation, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other regions.

6.1.6 Influence of external factors

This study did not consider the impact of external factors, such as political events or reforms, that could have influenced youth political participation. Such factors can temporarily increase or decrease young people’s engagement.

6.2 Future studies

Future research should focus on evaluating the effectiveness of civic education programs in various contexts to determine how they impact political literacy, election participation, and other forms of political action. This provides specific recommendations for educational institutions to boost youth engagement. Although this study is centered on Kazakhstan, insights from youth political participation in other post-Soviet developing democracies such as Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, as well as regions in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, could enhance the analysis. Comparative studies will help to identify common trends in transitional societies. Additionally, while this research highlights that political culture significantly influences youth participation, its effects may vary according to the type of participation. Future studies could investigate how different aspects of political culture, such as trust in institutions and attitudes toward the political system, impact youth engagement in various ways. It could also examine the role of youth organizations (student unions and civic groups) in shaping political attitudes and encouraging participation. Lastly, given Kazakhstan’s multi-ethnic character, future research should examine how ethnicity, regional identity, and socioeconomic factors affect youth political engagement, leading to more tailored strategies for reaching diverse groups.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions