- George Mason University, Schar School of Policy and Government, Arlington, VA, United States

Introduction: The taxation of multinational digital firms presents unique challenges due to the decoupling of value creation from physical presence. While international bodies like the OECD have advanced policy proposals—most notably through Pillar One—there remains a broader conceptual debate on how digitalization reshapes traditional tax norms. This study seeks to document and categorize emerging, arguments for reforming global tax rules in response to digital economic activity.

Methods: The study analyzes all stakeholder submissions to the OECD’s Pillar One consultation process. A qualitative coding approach was used to identify recurring themes and conceptual justifications for reforming the allocation of taxing rights.

Results: The analysis identified several categories of nontraditional arguments for revising international tax norms. These include proposals to shift taxing rights away from residence-based physical presence rules; arguments to internalize the societal costs of digital marketplaces; and the use of taxation as a regulatory mechanism to constrain digital platform dominance. These conceptual innovations go beyond traditional efficiency or fairness arguments in tax policy.

Discussion: While not always reflected in final OECD policy outcomes, these arguments provide a taxonomy of emerging ideas that could influence future tax debates—particularly as generative AI and digital platforms increasingly dissociate economic activity from territorial nexus.

Introduction

The global shift towards digitalization is reshaping the international tax landscape significantly. The rapid emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) is poised to further upend long-standing tax principles, raising foundational questions about how and where value is created in the global economy. Much like the digital platforms that preceded it, AI relies heavily on user data, network effects, and the extraction of value from participation by individuals and firms located in specific jurisdictions—even in the absence of a physical corporate presence. But the nature of AI makes this dynamic even more complex: by training on localized user inputs, language, behavioral patterns, and demographic data, AI systems often generate value that is inextricably tied to the geographic locations of users. This suggests a future in which the traditional legal standards of “source” and “nexus” are rendered increasingly obsolete, and in which claims of taxing rights may be rooted in the participation of users, rather than the operations of firms. In this way, AI presents not just a technological disruption, but a conceptual challenge to the geographic boundaries that underpin international tax law.

Understanding how the global tax community has responded to similar challenges posed by earlier waves of digitalization—particularly through Digital Services Taxes (DSTs) and the OECD’s Pillar One proposal—offers a critical lens for anticipating the next phase of tax debates. The arguments advanced in favor of DSTs and Pillar One are not only about fiscal fairness or tax base protection; they represent an attempt to redefine the boundaries of markets, and to assign value to user engagement, data generation, and intangible participation. As policymakers around the world grapple with the implications of AI—especially as AI-specific firms gain prominence and traditional multinationals embed AI into their business models—these same arguments are likely to reemerge, adapted to a new technological context. Indeed, scholars have begun to argue that AI will require new frameworks for value attribution, nexus thresholds, and source rules in international tax law (e.g., Turina, 2020; Oberson, 2025). Others have gone even further, proposing the taxation of AI systems themselves as a means of offsetting job displacement and social disruption—a logic that draws more from regulatory taxation and externality theory than from traditional corporate income tax principles. These proposals invoke a regulatory model akin to Pigouvian taxation, targeting AI-generated externalities to fund worker retraining and to slow the rapid erosion of labor markets (Kovacev, 2020; Acemoglu, 2020).

This article offers a descriptive analysis of the arguments made in support of the OECD’s Pillar One proposals and reports leading up to the Multilateral Convention (MLC), based on responses to public consultations and stakeholder feedback. Its focus is on nontraditional public finance parameters like tax incidence, efficiency, and equity, and highlights a broader set of normative and structural arguments used in support of new digital taxes. The article will highlight proposals to redefine market participation; efforts to tie taxation rights to user value creation; and the use of taxation as a regulatory or corrective instrument to rein in platform power. These arguments reflect a shift in tax discourse—one that blurs the lines between taxation, competition policy, and digital governance.

Numerous articles have examined the OECD Pillar One frameworks and Digital Services Taxes (DSTs) more generally, offering both legal and economic analyses of the evolving international tax landscape. For instance, Olbert and Spengel (2019) trace the conceptual and legal shift away from physical presence as a basis for taxation, emphasizing the challenges traditional tax systems face in attributing value to digital services. Their analysis provides one of the most comprehensive frameworks for understanding why digitalization pressures existing nexus and profit allocation rules. Harpaz (2021) analyzes the evolution of national DSTs and how they interact with OECD efforts, noting the tension between multilateral coordination and unilateral implementation. He observes that DSTs have emerged in part because of frustrations with the slow pace of OECD negotiations, but also because national governments see them as mechanisms for addressing the unique value generated by user data and platform intermediation.

Avi-Yonah et al. (2022) provide a comparative analysis of various national DST frameworks and the OECD Pillar One Blueprint, emphasizing where unilateral and multilateral approaches converge and diverge. Their article helps clarify how many of the underlying concerns—such as the perceived under-taxation of highly digitalized firms and the impact of retaliatory DSTs—are addressed differently under each model. Expanding the scope of inquiry, Friedan and Lindhoml (2023) develop a taxonomy of theoretical justifications for U. S. state-level DST proposals, including rationales such as regulatory taxation, severance taxation, and value extraction analogies. They argue that while the economic logic overlaps with Pillar One in many cases, subnational DSTs are structurally different in two key ways: (1) they are often structured as gross receipts or sales taxes, not income taxes; and (2) they lack the anti-base erosion or BEPS rationale that underpins OECD efforts. This distinction is especially important for understanding the broader policy logics at play.

Further scholarly work emphasizes how the debate over digital taxation raises fundamental questions about the purpose of the tax system. In particular, the focus on user value and data as sources of taxable income reopens longstanding questions about where economic activity occurs and who benefits from digital transactions. In this way, digital tax scholarship is not only about efficiency or incidence, but about the legitimacy of tax systems in an increasingly intangible global economy.

These works collectively demonstrate that arguments in favor of taxing digital services companies—whether through DSTs or the Pillar One framework—are not confined to standard corporate tax paradigms. Instead, they incorporate regulatory, distributive, and sovereignty-based rationales. The DST and Pillar One debates thus reflect a broader transformation in international tax discourse, in which the digital economy challenges not just tax policy but core legal and conceptual categories of global economic governance.

By cataloging the arguments advanced in support of taxing user-based value in digital business models, this article contributes to a deeper understanding of the evolving intellectual and policy landscape. These arguments are likely to be foundational as policymakers revisit the structure of international tax law in an era increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence.

The article proceeds as follows. The next section provides a brief overview of the OECD Pillar One and Pillar Two proposals, followed by a description of the consultation letters data and methodology. The spectrum of justifications for the digital taxes in the consultation letters are described and the paper then concludes.

OECD Pillar One and Pillar Two background

In response to the challenges posed by the digitalization of the economy and the erosion of traditional tax bases, the OECD has proposed a comprehensive framework known as Pillar One and Pillar Two. These pillars represent a paradigm shift in international taxation, aiming to address the issues of profit allocation and taxation rights in an increasingly interconnected and digitalized global economy (Navarro, 2021).

Pillar One focuses on the allocation of taxing rights, particularly in the context of digital businesses. Traditionally, tax rules were designed for a world where businesses had a physical presence in a country, making it relatively straightforward to determine where profits were generated and consequently where taxes should be paid. However, the rise of digital business models has challenged this traditional framework, as these companies can generate significant value in jurisdictions without a physical presence.

Pillar One introduces new rules for the allocation of taxing rights, particularly for highly digitalized businesses. It suggests a reallocation of taxing rights based on a nexus approach, considering factors such as user participation, marketing intangibles, and significant economic presence. This aims to ensure that businesses are taxed in jurisdictions where they have a substantial economic impact, irrespective of their physical presence (Eden, 2021).

Pillar One is not a Digital Services Tax (DST) like those proposed or passed in the UK, India and France. Whereas DSTs are unilateral measures to address the challenges posed by digital businesses that can operate and generate significant value in a jurisdiction without having a physical presence, Pillar One is a coordinated effort to redefine the allocation of taxing rights in the digital economy. This is a critical context of the responses to Pillar One, as it is offered as an alternative to fragmented rules and trade tensions (Friedan and Lindhoml, 2023).

There are key elements of overlap, however, between many of the unilateral DSTs and the Pillar One discussions. DSTs often rely on a concept of significant economic presence or user participation to establish a nexus for taxation, though the criteria and thresholds for such presence vary between countries. Pillar One also introduces a nexus-based approach for profit allocation but aims to establish a more standardized set of criteria. It considers factors such as user participation, marketing intangibles, and other indicators to determine where a business has a taxable presence.

The Digital Services Taxes (DSTs) supersede the conventional physical presence standard and income-producing activity sourcing rules, specifically for the taxation of designated digital business sectors. Employing an economic presence standard, DSTs ascertain the businesses mandated to register and adhere to taxation requirements. Furthermore, DSTs incorporate sourcing rules that allocate gross receipts to individual countries based on customer location, diverging from the traditional approach of linking it to the seller’s location of income-producing activities.

The Pillar One negotiations have evolved away from pivotal reforms to align international tax laws with the evolving landscape of digital business models (Friedan and Do, 2021). In October 2023, the OECD released the draft text of a Multilateral Convention (MLC) for Pillar One, narrowing its focus on reallocating a portion of residual profits—termed Amount A—from the largest and most profitable multinational firms to market jurisdictions. While early proposals emphasized user participation and the value created by user data, the final MLC no longer includes these features as formal allocation factors. The concept of user-generated value, which once formed the intellectual foundation of several DSTs and Pillar One drafts, was removed in favor of a simpler formula based on revenue thresholds and profitability. A timeline of Pillar One developments, including the release of the key reports with invitations for public comment is included in Table 1.

Pillar Two focuses on addressing the challenges of base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). While it is not the focus of this article, it is important to note that many responses to Pillar One include references to BEPS proposals. Pillar Two aims to establish a global minimum tax rate to prevent companies from shifting profits to low-tax jurisdictions, thus ensuring a fair and level playing field for businesses around the world. The proposal includes the introduction of an income inclusion rule (IIR) and an undertaxed payment rule (UTPR) that requires countries to tax the income of their resident companies if it has not been taxed elsewhere at or above the agreed minimum rate. The UTPR allows a jurisdiction to deny deductions or apply withholding taxes on payments made to related entities in low-tax jurisdictions.

Since the initial proposal, Pillar Two has gained substantial traction globally. As of 2025, more than 90 percent of in-scope multinational enterprises operate in jurisdictions that have implemented or are in the process of implementing key components of the Pillar Two framework. These include qualified domestic minimum top-up taxes, often based on the OECD’s Global Anti-Base Erosion (GloBE) model rules. The OECD has released multiple rounds of guidance, including a consolidated commentary in 2025 to clarify key technical elements and aid harmonization across countries. Numerous jurisdictions have enacted Pillar Two legislation or are conducting public consultations on its implementation, while negotiations over treatment of a U. S. standard for a global minimum tax.

The implementation of Pillar One and Pillar Two carries significant implications for multinational enterprises, tax administrations, and the global economy. It seeks to create a more equitable distribution of taxing rights and revenue among countries, reducing the incentives for profit shifting and tax avoidance. Yet serious challenges remain, including sustaining broad international consensus, ensuring coordination between different domestic legal systems, and navigating unresolved tensions between major economies. These issues are especially acute for developing countries, which continue to raise concerns about the administrative burdens, legislative restrictions and revenue-sharing formulas embedded in the current framework.

Consultation letters – data and methodology

There is a sizeable academic literature that examines requests for input from stakeholders in collective decision making. Stakeholder engagement in public decision making is a crucial element of governance. Ayres and Braithwaite (1992) and subsequent work on responsive regulation argue that stakeholder engagement in public decisions is a crucial element of governance and can improve regulatory outcomes by expanding information and accuracy. Consultation processes can serve as a means of collecting information and viewpoints to improve legal and regulatory outcomes and increasing public trust of outcomes (Friedan and Do, 2021; Harpaz, 2021; Olbert and Spengel, 2019). However, there are mixed results as to the impact of stakeholder engagement processes on decision outcomes, depending in part on the timing of request for input and the complexity of the of the issue (Fink et al., 2021; Pedersen, 2021).

Aside from their efficacy in influencing final outcomes, stakeholder inputs are useful to gain understanding of interest group participation, coordination across networks, and the types of arguments used to support or dispute a proposal. Often, studies of consultations focus on quantitative analysis of participants or the content of the letters themselves (Akhmouch and Clavreul, 2016; Kidwell and Lowensohn, 2019). A study of EU financial regulatory consultations between 2010 and 2018 examined lobbying coordination based on duplicate language in letters (James et al., 2021). Another studied interest group participation in financial regulations internationally and found that there is substantially less mobilization and participation in consultations by interest groups outside of the business community. In addition, the level of non-business group participation is impacted by the technical complexity and institutional context of the regulation in question (Pagliari and Young, 2016). Interestingly, policy losers and those with access to other means of communication are more likely to write public letters that differ from private communications (Ingold et al., 2020).

OECD consultations are frequently cited as having consultation processes relatively early and frequently to build consensus (Pedersen, 2021). In 2014, the OECD did a study of its own stakeholder engagement specifically related to water governance decisions to determine the drivers of engagement in the consultation process, the types of stakeholders involved, and the costs and benefits of the process (Akhmouch and Clavreul, 2016). This study found that stakeholder engagement improved capacity of knowledge development, economic efficiency, and social equity but that stakeholders were overwhelmingly those with greater resources or capacity to engage. A study similar to this one uses qualitative content analysis of the OECD consultation process letters for the corporate tax transparency standard of Country by Country Reporting (Müller et al., 2022). That study found that the majority of respondents were business representatives and about a quarter were non-governmental organizations or trade and labor groups. The article created a simple taxonomy of stakeholder positions, arguing that the consultation letters provide a unique opportunity to view differing viewpoints on a level playing field.

A study with particular relevance to this examined the consultation letters for all OECD BEPS actions, including the two requests for inputs included in this study. While this study was not interested in the details of value creation and the issue of digital taxation, it does provide simple classifications for participant types (business/government/academic/individual), positions on BEPS (positive/negative/neutral) and the letter approach (normative/analytical) (Procházka, 2020).

To facilitate a systematic examination of the consultation letters, a qualitative content analysis methodology has been employed (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). The goal is to categorize extensive textual inputs into concise content categories. Because the data is systematically assigned to predefined categories of arguments for digital taxes in the international framework derived from prior papers this is a directed content analysis. Each category represents a distinct set of criteria distinguishing it from others.

The analysis encompasses all comments submitted and reported by interested stakeholders to the OECD’s Task Force on the Digital Economy during two key periods, on separate reports related to the tax challenges raised by digitalization. In the development to address BEPS, the OECD and G20 countries adopted a 15-point Action Plan in 2013, and significant reports from the OECD followed from this action plan were presented with time periods for consultation. The first report is the Action 1 Final Report from 2015, entitled “Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy (OECD, 2015; OECD, 2022).” The report lays out the tax challenges for international taxation of the digital economy. The request for input spanned the period between September 22–October 13, 2017. The second report studied here is a follow up to the 2015 Action 1 report, “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018 (OECD, 2018).” This report offers more specific frameworks for international tax rules related both to digitalization and BEPS, outlining possible solutions to the tax challenges arising from the digitalization of the economy. The public consultation period spanned the period between February 13–March 6, 2019.1

It is important to note that these consultation requests were specific and prompted stakeholders to specifically consider user value creation. The ongoing work on BEPS challenges are included in these consultation documents, but there are clear delineations on highly digitized business models involved with data and user value creation. The 2017 consultation specifically requested input on business models, value creation and data collection (the full list of questions is included in Supplementary material).

The 2019 consultation focused on three proposals for businesses characterized by scale without mass and a heavy reliance on intangible assets and data and user participation. The three proposals are roughly described as:

• The user participation proposal – revises profit allocation rules to accommodate the value creating activities of users, restricted to social media platforms, search engines and online marketplaces meeting threshold criteria

• The marketing intangibles proposal – revises profit allocation rules for a broader set of businesses to allow the market jurisdiction to tax some or all of the non-routine income associated with marketing intangibles and their attendant risks

• The significant economic presence proposal – existing nexus and profit allocation rules are revised substantially for all entities. For those businesses where users meaningfully contribute content, users would be taken in account in apportioning income

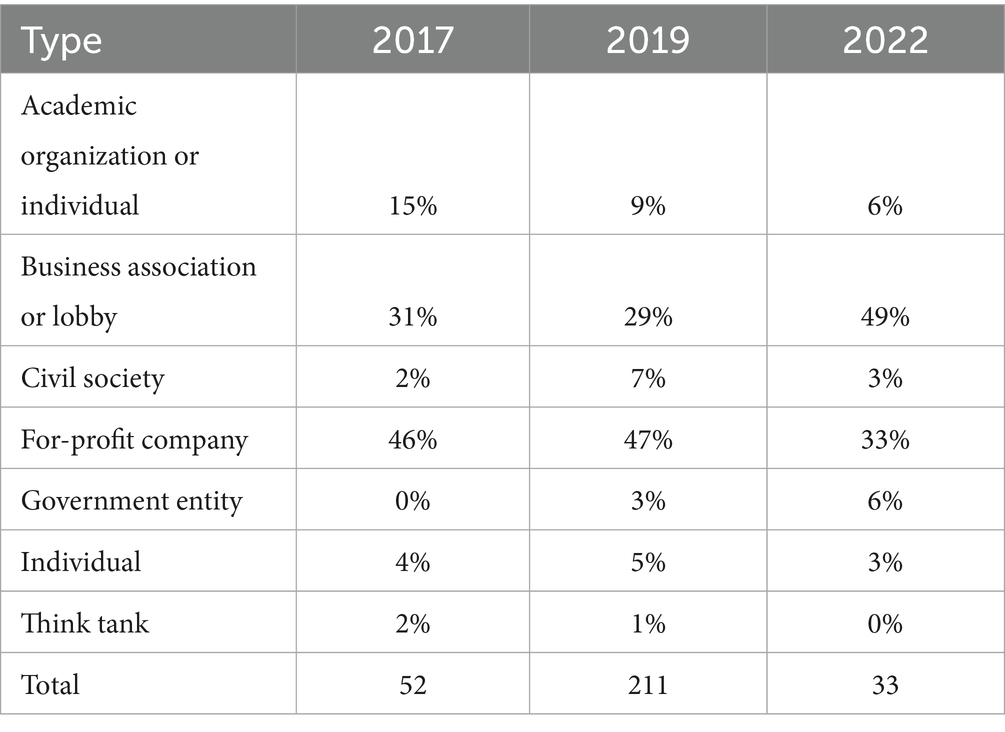

A total of 265 comments were received (53, 212 and 33 in 2017, 2019, and 2022, respectively). A summary table of the types of respondents is included in Table 2. Three letters not written in English were excluded. Of these, 41 were in favor of the idea of basing some elements of profit allocation for tax purposes on user participation or value creation from users. This is somewhat contradictory of a previous study of BEPS consultation responses, which found that roughly half of the BEPS consultation letters were supportive (Procházka, 2020). A key difference between this paper and the prior study is that the previous article categorized general statements of support for the OECD process and multilateral coordination as supportive. In this study, the criteria for inclusion was more than a tepid endorsement of a vague concept of tax coordination or modernization.

In addition, this study does not consider letters written to argue industry exclusion from the proposed changes as supportive. Consider this letter with a stated support for the user participation proposal in the 2019 consultation from the Swiss Bankers Association. The Association offers a tepid statement of support along with the following qualification:

“[The] ‘user participation’ proposal should be limited to truly digitalized companies. Contrary to that, banks offer traditional services where user interaction does not play a significant role in the value creation. Therefore, banks should be explicitly carved out from any ‘user participation’ proposal.”

Prochazka’s taxonomy of the supportive/opposed consultation letters included this type of response (“just do not tax us”) as supportive of the proposal; this study excludes these otherwise neutral or supportive stakeholder letters.

Rationales for Pillar One

Defining the market jurisdiction

The first category of arguments in favor of a new value creation standard aligns closely with the foundational justification for OECD Pillar One. At its core, this category critiques the long-standing reliance on the permanent establishment (PE) concept in international tax law, which conditions taxing rights on the physical presence of a firm within a jurisdiction. This framework evolved in an era of brick-and-mortar commerce and manufacturing, where production, sales, and service provision were clearly tied to tangible assets. The rationale argues that in the digital economy, firms can engage deeply with users, generate substantial revenue, and shape consumer behavior in a jurisdiction without setting foot there. As a result, market jurisdictions face systemic constraints in taxing the profits of multinational enterprises (MNEs) that generate economic value from within their borders but lack a recognized legal nexus. Pillar One, by rethinking the allocation of taxing rights toward market jurisdictions based on economic presence, seeks to address this structural asymmetry.

Canadians for Tax Fairness: “We welcome that all three proposals involve a shift away from the arm’s length principle and towards approaches that would shift taxing rights towards market jurisdictions… The degree to which businesses are able to avoid taxes in countries where they have an active presence is becoming ever more apparent, is more pronounced among more digitized businesses, and has accelerated as more types of businesses become increasingly digitized. The extent of this is not yet known because public country-by-country reporting is not yet in place.”

This statement underscores the structural erosion of tax bases under the PE standard. Canadians for Tax Fairness not only endorse the reallocation of taxing rights to market jurisdictions but also emphasize that the problem is growing as more sectors become digitally enabled. Their comment also points to an institutional gap: the lack of public country-by-country reporting obscures the full extent of profit shifting. This connects the technical issues with broader concerns about transparency and tax justice, and it supports Pillar One not merely as a reform of allocation rules but as a mechanism for improving accountability in global taxation.

Schibsted Media Group: Schibsted’s competitors are to a large extent global players like Facebook and Google. The global players’ profits are as the main rule subject to no or low income tax. The countries’ right to tax the global players depend on them having a taxable presence, normally in form of a ‘permanent establishment.’ The PE concept was implemented with traditional business models in mind, and do not catch digital revenues from the global players’ business models. For example, the global players’ business models require no or little need for establishing a physical presence in Europe to retrieve digital advertising revenues from European customers. Thus, the current legislation makes it possible for the global players to legally avoid PT-status and local taxation of digital advertising revenue. If the global players do have a PE or a local company, profits attributed to this PE or local company will regularly be minimized through legal structures shifting profits to low tax countries. The tech giants largely implement tax-planning strategies that exploit gaps in tax rules, in order to shift profits to low-tax or even no-tax locations where there is minimal economic activity, resulting in little or no overall corporate tax being paid. According to current international rules, this is legal.

Schibsted presents a compelling example of how the current PE rule places local firms at a disadvantage. Their argument emphasizes the competitive asymmetry between domestic firms that operate with a local footprint and global tech giants that generate revenue from the same markets without establishing any taxable presence. The commentary elaborates on the legal—but arguably unjust—nature of profit shifting, even in cases where a PE or local entity exists. The observation that tax planning regularly “minimizes” profits in source countries reinforces the view that nexus and attribution standards must evolve together if market-based taxation is to be meaningful. Schibsted’s remarks are particularly useful because they combine principles (fairness, alignment of value and tax) with vivid operational examples.

South African Institute of Professional Accountants: One reason digital businesses can escape taxes is that they need no factories, stores, or other fixed places of business in order to sell their services to consumers in a particular country. Since current international tax rules still rely on the old brick-and-mortar concept of a permanent establishment (PE) to assign tax jurisdiction, the digital economy makes it possible to operate a thriving cross-border business virtually tax-free. Another reason is that corporate value is increasingly concentrated in intangible assets, such as patents and copyrights on software and digital content. Such assets are easily transferred to tax havens in order to minimize the business income taxable in higher-tax jurisdictions.

This response, from a professional association in a developing economy, broadens the geographic lens of the critique. The South African Institute’s statement reinforces the idea that digital disintermediation – selling services without a fixed business presence – undermines the tax sovereignty of many countries, particularly in the Global South. Moreover, they highlight that value creation is increasingly tied to intangible assets, which are far more mobile than traditional capital. This adds a second layer to the argument: not only do outdated nexus rules allow tax base erosion, but intangible-based valuation allows for geographic flexibility in locating that value for tax purposes. Their call implicitly supports not only Pillar One (for nexus reform) but also Pillar Two (for minimum taxation of profits that escape high-tax jurisdictions).

In sum, these three stakeholder responses cohere around a central concern: the PE-based framework of international taxation is no longer sufficient to capture where value is created in a digital economy. They reinforce the normative and practical case for a shift toward economic presence, while also raising issues of transparency, competition, and tax equity. Far from being abstract or merely technocratic, the debate over nexus has real implications for revenue collection, fairness, and the legitimacy of international tax rules.

Tax justice

A related but distinct category of arguments in support of Pillar One reforms centers on tax justice, particularly in the context of global inequality and the under-taxation of multinational enterprises operating in developing countries. While arguments about tax avoidance focus on gaps in legal frameworks—such as the inadequacy of permanent establishment rules or the manipulation of transfer pricing norms—tax justice arguments place these shortcomings in a broader ethical and geopolitical context. They emphasize that existing tax standards systematically disadvantage lower-income countries, which often serve as key markets or sources of data and value creation but lack the economic leverage to tax global firms under current international norms. These perspectives draw from principles of fairness, equity, and even international human rights, calling attention to how tax policy intersects with global development and political legitimacy. Notably, while tax avoidance critiques tend to remain within the technocratic discourse of efficiency and enforcement, tax justice arguments push the debate into normative terrain, questioning whether the international tax order reflects an equitable distribution of power and responsibility among nations.

Initiative for Human Rights: As the process that triggered this public consultation shows, some key aspects of global corporate taxation rules are no longer fit for purpose. Examples include the presence of a physical establishment as the criterion to determine where a company should pay taxes, and the notion that multinational affiliates can be treated as separate entities that make transactions at market prices (the arm’s length principle). These rules are inadequate to ensure multinational enterprises in the digital era pay taxes where they ‘create value’ and are also inadequate to meet broader justice notions such as those contained in international human rights law.

This comment articulates a powerful critique that blends technical obsolescence with normative failure. The Initiative for Human Rights echoes many of the same concerns about outdated legal standards—such as the physical presence test and the arm’s length principle—but reframes them as obstacles to justice, not just enforcement. The reference to international human rights law signals a shift in conceptual framing: taxation is not merely a matter of revenue collection or economic efficiency, but of states’ ability to fund essential services and fulfill social rights. This broadens the scope of the Pillar One debate, making it not just about where profits are taxed, but whether the global tax system upholds a fair social contract in a digitized economy. Their use of quotation marks around “create value” also subtly critiques the subjectivity and contestation around that concept—implying that the current formulation fails to adequately reflect where value is generated, especially in developing markets.

Tax Justice Network Africa: We support the development of the global anti-base erosion proposal to counter any harmful or aggressive tax strategies that may be developed to counter the proposals above. Profit shifting is likely to remain a challenge in the evolving digital economy and, in this context, the needs and challenges of developing countries should be brought to the fore.

The Tax Justice Network Africa reinforces the idea that profit shifting harms developing countries disproportionately, both because they lack the legal tools to police it and because they rely more heavily on corporate tax revenues to fund public services. Their endorsement of anti-base erosion measures suggests support for both Pillar One and Pillar Two, but what distinguishes their contribution is the explicit call to center the perspectives of lower-income countries in the design and implementation of global tax rules. Unlike some business or academic responses that frame BEPS rules primarily as instruments to ensure neutrality and market efficiency, TJN Africa emphasizes that without structural reform, the digital economy risks exacerbating global inequality.

Together, these responses highlight that tax justice arguments are not merely moral appeals—they reflect growing dissatisfaction with the foundational assumptions of international tax law. They push beyond the question of “how to tax” digital services and instead ask “who gets to benefit from the value created in a global economy.” The alignment between these arguments and the goals of Pillar One is partial but important: while the OECD’s focus remains on reallocating taxing rights, tax justice advocates view such reallocation as a step toward rebalancing fiscal sovereignty and advancing equity in global governance.

User participation in value creation

A related set of arguments for the Pillar 1 reforms center more on the issue of value creation in existing international tax rules. Currently, international corporate income tax relies primarily on aligning value creation and the allocation of taxing rights with the physical location of income-generating activities, rather than the market or customer location. This approach is increasingly seen as mismatched with digital business models, especially those that derive significant revenue from user engagement and user-generated data. As a result, countries have struggled to attribute sufficient taxable income to jurisdictions where economic activity—namely, user participation—takes place.

The user participation model proposed in early OECD blueprints represented a significant departure from traditional norms. It acknowledged that users themselves create value by engaging with platforms, generating data, and indirectly enabling revenue through advertising, algorithm training, and market insights. This rationale marks a pivot from arguments about tax avoidance or physical nexus to a substantive theory of where economic value originates. In the context of Pillar One, this theory justified taxing digital services companies in market jurisdictions even without a traditional permanent establishment. Importantly, this model also offers a possible precedent for arguments about AI, where users may help create or refine content through interaction or provide training data for machine learning.

International Bureau of Fiscal Documentation: The [UK DST] proposal distinguishes the user from the consumer and recognizes that ‘users’ participate in much more than allowing the collection of customer data, thus being relevant to a broad range of digital and non-digital businesses. Accordingly, it may be argued that the ‘user participation’ Proposal is not about addressing low-taxed income or levelling an unlevelled playing field (which were the justifications provided for a reform of the rules within the BEPS Project). Rather, as suggested in the literature, the Proposals, including the ‘User Participation’ one, are now clearly about a revenue shift from residence jurisdictions to those where these contributing users are located.

This submission articulates a core conceptual shift: from a tax framework focused on correcting distortions caused by tax avoidance to one premised on reallocating taxing rights based on actual sources of value creation. It clarifies that user engagement is not incidental to the business model but rather an essential component of revenue generation. By emphasizing that the reform is about “revenue shift,” it aligns with a broader critique of outdated residence-based taxation and bolsters the case for structural reform. This recognition of users as contributors—not just passive consumers—also gestures toward future debates on digital labor and data as economic inputs.

Simmons and Simmons: Companies whose business model consists of making available online marketplaces, search engines and platforms, could be considered to make their money nearly exclusively from user participation and user data… We believe that the user participation model benefits from the rationale that it addresses the digital economy conundrum at its core. It addresses the core complaint that the new platform/search engine and online marketplace business models essentially escape corporate taxation in countries where their income is respectively earned.

This submission supports the idea that user participation is not merely incidental, but forms the backbone of digital business revenue models. By arguing that profit is derived “nearly exclusively” from users, Simmons and Simmons strengthen the claim that taxing rights should follow user engagement. They frame the existing tax gap as a consequence of mismatched geographic attribution of value, reinforcing the idea that profit “earned” in user jurisdictions is currently untaxed due to legacy frameworks. The recognition of user participation as core to these models foreshadows possible applications to generative AI, which may rely even more heavily on user prompts, feedback, and behavioral data.

Tax Justice Network Africa: The digitalization of the global economy and business models needs to pay more attention to the growing importance of user data and information in keeping the digital economy alive and growing. Understanding the monetary value associated with user data and information is also important in determining where and how taxing rights are allocated especially in developing regions where this right has and continues to be eroded through aggressive and harmful tax practice.

Tax Justice Network Africa connects the user participation argument to questions of equity and global justice, emphasizing that the economic value of user data is especially vulnerable in developing countries. This submission not only endorses the user participation model but also expands its implications: user-generated value should inform the allocation of taxing rights, particularly where current rules disadvantage jurisdictions with large user bases but little multinational headquarters presence. Their framing adds a global development lens to the technical concept of value creation, arguing that data extraction from developing regions without fair taxation resembles an exploitative dynamic. This is likely to become more salient as AI technologies begin to incorporate data from a global user base, including low- and middle-income countries.

Torvik: User data and ongoing user participation in reality functions as significant value drivers—or more precisely; value chain inputs—for the marketing / ad products sold by social media and search engines… the data the user provides to the multinational and the ongoing relationship between the user and the multinational should clearly be seen as marketing intangibles.

Torvik’s argument deepens the technical analysis by interpreting user contributions as intangible assets in the value chain, akin to marketing intangibles under transfer pricing doctrine. This approach elevates user engagement from a conceptual or rhetorical value source to a legally and economically recognizable component of the business model. His framing helps integrate user participation into existing tax law structures by treating users as inputs that produce tradable assets (data, relationships, engagement metrics). It also creates space for more ambitious interpretations of value creation, potentially informing how AI user interactions (which can fine-tune models or generate creative outputs) might be considered taxable contributions in the future.

A subcategory of the user participation argument sharpens the focus by treating user data and user bases not only as contributors to revenue, but as balance sheet assets—potentially measurable, assignable, and monetizable in their own right. While the broader user participation model justifies taxation in the market jurisdiction by emphasizing that users help create the value that generates income (e.g., through attention, engagement, or data), this more asset-oriented argument suggests that accumulated data and user networks themselves should be treated akin to intangible assets.

This framing has two key implications. First, an MNE’s intangible data footprint could alone establish a taxable presence. This builds a novel bridge between existing PE standards and digital-era economics. Second, value can be created well before monetization. A company can accumulate intangible value in its user base and data, even in the absence of current profits, and that value accrues to the firm’s balance sheet and market valuation, rather than its income statement. This is especially important in the digital economy and is potentially applicable to generative AI firms, many of which derive immense market value from training datasets and user interactions even before earning substantial revenue.

Jeffrey Kadet: Without going into unnecessary detail, it is clear that an accumulated user base and the accumulated data on that user base are identifiable assets that have value to specific strategic acquirers and to investors and the markets more generally… One issue is whether a user base and/or accumulated data could be sufficient presence to justify a taxable nexus. I believe that the answer is yes.

Kadet’s quote argues that accumulated user data and user bases function as capital assets—distinct from the flow of value associated with user interaction. He pushes the envelope further by asserting that this asset status could alone justify a PE (permanent establishment), even under existing international tax law. This view blends digital intangibles with traditional asset-based PE thresholds. Importantly, he points out that MNEs often structure operations to fragment physical presence and revenue recognition across jurisdictions, thus sidestepping nexus rules. Kadet calls for a holistic interpretation of business activity, aligning taxation with the economic reality that data and digital assets are often held in one part of the group while value is generated elsewhere.

BEPS Monitoring Group: We do consider that the collection and exploitation of data… amount to sufficient presence to justify a taxable nexus… However, this would normally be treated as a capital gain, not income. Nevertheless, the user base constitutes an asset, although not usually shown in the balance sheet. Hence, it could be taken into consideration in calculating the asset factor if one is used in the formula for allocating profits.

The BEPS Monitoring Group adds nuance by distinguishing between income and asset value. They note that user data and content contribute to firm valuation, often through the logic of capital markets (e.g., IPOs or acquisitions), even if they do not immediately yield profit. The implication is that intangibles like user data merit consideration in profit allocation formulas—for example, through an asset factor in a formulary apportionment system. This introduces a hybrid view, where digital assets can shape both nexus and allocation rules, even outside traditional revenue metrics. Their insight also anticipates difficulties in enforcement: while the asset value of data may be clear in economic terms, it is rarely reported transparently in financial accounts.

Together, these arguments suggest that future international tax frameworks may need to evolve beyond income flows and look more seriously at value stored in intangibles like user data, potentially updating nexus standards, asset recognition practices, and apportionment formulas. They also hint at parallels with AI, where datasets and trained models are core intangible assets whose creation is often user-driven but whose value may not be recognized until later stages of monetization or acquisition.

Severance and regulatory tax

Two closely related arguments—framing Pillar One or digital services taxes (DSTs) as a severance tax and as a response to externalities—offer a distinct rationale from user participation or anti-avoidance logic. While the user participation model emphasizes how value is co-created through the interactive presence of users in market jurisdictions, and tax avoidance arguments focus on mismatches in legal definitions and the need to capture income where it is truly earned, the severance and externality frameworks take a broader view. They suggest that digital platforms extract something valuable—often invisibly—from jurisdictions and their populations, and that taxation can serve as both compensation and regulation. These perspectives could be particularly relevant in emerging debates about artificial intelligence, where the extraction and use of public data, creative content, and behavioral patterns mirror the concerns raised here.

The severance tax analogy likens personal data and digital user interactions to non-renewable natural resources. Traditionally, severance taxes are imposed by states on the extraction of resources like oil or gas that are consumed elsewhere. Applying this logic to the digital economy, some argue that the extraction of user data—especially when that data is intimately tied to a population or jurisdiction—justifies a similar fiscal claim by the state. In a proposed New York state-level DST, for example, the tax was described as “best thought of as analogous to a severance tax. Rather than crude oil or natural gas, the state resource in this instance is data specific to individual New Yorkers. These New Yorkers have a demonstrable legal interest in this data, and the state of New York has a connection to this resource that is similar to its connection to natural resources found within its borders. Both types of resources are closely linked to the state, in one instance to its land, in the other to its people. This linkage gives the state the right to impose a ‘severance tax’ on the resource as it is ‘extracted’ for commercial use” (Plattner 2021).

Ludovici Piccone and Partners: Nobody in 1930s could have imagined that personal data could be labeled as ‘resources’ or refer to ‘extraction’ of such data with respect to data mining activities. … MNEs operating in a digitalized economic environment carry on a significant data-mining activity (the value of which can mirror that of extracting oil or other commodities from the soil of a country). The latter activity, i.e., data sourcing from users in a certain jurisdiction is akin, from a tax standpoint, to the intangible resources with respect to which value is extracted.

Ludovici Piccone and Partners argue that today’s economic reality demands a reinterpretation of the concept of resource extraction. They point out that the OECD definition of permanent establishment in Article 5, paragraph 2(f), historically referred to tangible resources like quarries and gas wells. Their commentary highlights the outdatedness of this view, given the rising economic value of user data. They suggest that data-mining activity in a given jurisdiction should be seen as equivalent, from a tax perspective, to the extraction of physical natural resources—especially as personal data is increasingly central to digital value creation.

The same consultation letter offers an externality-based argument for taxation:

[W]hat stands out is the disruption occurred within the value creation process whereby entities (either individuals or separate enterprises) generate value to multinational enterprises by means of what we would refer to as ‘unconscious contributions,’ i.e. value-generating activities not necessarily accompanied by the proactive willingness of the user itself.

Here, the emphasis is on unconscious user contribution, with little understanding of how behavior is monetized. In this framework, data becomes not just a commodity, but a byproduct of user behavior that is extracted without explicit consent or awareness. DSTs or similar taxes serve a compensatory function—akin to regulatory taxes on pollution or sin goods—addressing the social cost of widespread digital surveillance and data commodification.

Matthew Lykken: If most retail entities use the transactional data from their own customers to figure out certain things about those customers that enhance their profitability, then that simply becomes part of a routine retailer’s profit that will show up in the comparables. Comprehensive surveillance data is a different animal. To this extent, the user-participation proposal has a valid point. This is a novel asset that should be recognized and accounted for, so long as it is distinguished from normal transactional data of a discrete business.

Matthew Lykken builds on this idea by distinguishing traditional customer data from the comprehensive surveillance data collected by major digital platforms. He views this data as a novel asset—one that should be acknowledged in both valuation and tax design. His commentary lends support to arguments that current transfer pricing frameworks, which rely on comparables and arm’s length standards, fail to account for the unique value generated by continuous data extraction. As AI systems grow more reliant on vast troves of user data, these distinctions are likely to become even more central in debates over fiscal fairness.

Schibsted Media Group: A consequence of the digitalization of the media industry is that advertising revenues have declined for print media and shifted to other digital marketing channels. The development has also opened up for global players, who are not producing news content themselves, but rather benefit from news produced by the European media industry. These global players compete with the local media business with regard to digital advertising revenues. More and more journalistic content is published on digital platforms operated by global tech players, rather than through media businesses.

Concerns about negative social impacts are especially visible in the media sector. Schibsted Media Group describes how global tech firms profit from journalistic content without supporting its production, thereby undermining the sustainability of traditional news outlets. The shifting of advertising revenue from local journalism to global platforms not only distorts competition but weakens the informational foundations of democratic societies. A tax mechanism, in this context, could help redress that imbalance.

World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers: We strongly believe that finding a solution to the problem of a fair taxation system in the digital economy is strictly intertwined with the sustainability of the news media industry, and ultimately affects the protection of freedom of expression… The difference in applicable regulations represents an objective advantage that tech giants have on traditional media companies while competing for the same public and advertising money.

The World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers goes further by linking fair digital taxation to democratic values. Their argument implies that under-taxation of global tech giants represents not just an economic distortion, but a threat to freedom of expression and pluralism in the media landscape. When these companies outcompete traditional publishers without contributing to public goods, the tax system itself becomes implicated in the erosion of media independence.

Taken together, the severance and externality arguments expand the moral and policy justification for tax reform in the digital economy. They frame taxation not simply as a tool for aligning taxing rights with value creation or correcting legal mismatches, but as a mechanism for compensating jurisdictions and protecting the public interest from systemic imbalances. These rationales offer a useful bridge to future challenges involving artificial intelligence, where data is scraped, knowledge synthesized, and influence exerted without traditional forms of economic presence or transparency. As AI technologies replicate and accelerate the extraction of digital resources, the logic behind severance and externality-based taxation may grow even more urgent and broadly applicable.

Conclusion

This paper has examined the diverse arguments offered by stakeholders in support of the OECD’s Pillar One reform, with a particular focus on public submissions to the OECD’s consultation processes. By closely analyzing the language and rationales used in these stakeholder responses, the paper contributes to a deeper understanding of how different actors—ranging from civil society organizations and accounting associations to multinational firms and advocacy groups—articulate the need for new international tax rules in a digital economy. It highlights a typology of justifications that include tax avoidance and profit shifting, tax justice and fairness, user participation in value creation, the treatment of user data as an asset, and more novel claims rooted in severance and externality-based taxation. These arguments go well beyond technical adjustments to transfer pricing rules; they reflect a broader reimagining of where and how economic value is created, who benefits, and who bears the burdens of the current system.

The findings show that while many stakeholders acknowledged the need for reform, there was significant variation in how they framed the problem and the appropriate response. Among the most compelling insights is the way digital presence—especially through user interaction and data generation—was repeatedly described as a legitimate basis for taxation. In particular, the argument that users create value for digital platforms, and that this value justifies a shift in taxing rights toward market jurisdictions, was invoked both in technical and moral terms. Similarly, several actors likened data to a resource extracted from a jurisdiction, laying the groundwork for viewing certain taxes as a form of severance tax. Others took the argument further, framing digital taxation as a response to negative externalities such as misinformation, loss of privacy, and disruption of local industries like journalism. These claims position taxation not only as a tool for revenue collection but also as a mechanism for social and regulatory accountability.

Yet despite the creativity and normative force of these arguments, it is clear that many of them failed to achieve meaningful incorporation into the final form of Pillar One. The more radical proposals—such as user participation as a basis for nexus, the treatment of data as a balance-sheet asset, or the use of taxation to counterbalance externalities—did not survive the multilateral negotiations. The eventual framework moved away from the idea of user-created value, and instead focused more narrowly on reassigning a portion of residual profits to market jurisdictions under strict thresholds. Similarly, the notion of regulatory or severance-style taxation was excluded from the final compromise, which explicitly aims to replace unilateral digital services taxes that had embodied such concepts. In short, while a wide range of arguments were surfaced in the consultation process, the policy outcome reflects a much narrower consensus—centered largely around curbing tax avoidance and achieving minimal agreement among high-income countries.

This outcome is significant for both policymakers and scholars. It suggests that among the range of rationales for digital taxation, those grounded in concerns about profit shifting and base erosion remain the most politically salient and actionable. Nevertheless, the broader set of arguments documented here provides a critical roadmap for future reform efforts. As the global economy continues to evolve, and as new technologies such as generative AI further challenge the link between physical presence and value creation, the limitations of the current tax framework will become increasingly visible. Scholars can now use this taxonomy of justifications to track and evaluate emerging proposals for taxing AI and other intangible-intensive sectors. For example, as AI systems scrape data and provide services without human input or physical infrastructure, we may see a resurgence of arguments that recall user participation, resource extraction, and externality mitigation.

Finally, this paper adds to existing literature on the political economy of international tax reform by offering a detailed look at how stakeholder discourse shapes the scope and ambition of multilateral negotiations. While prior scholarship has often focused on legal texts or intergovernmental bargaining, this analysis demonstrates that public consultations offer a rich, underexplored source of evidence about the ideational currents behind tax reform. The public record of the Pillar One debate offers valuable insight into which arguments resonate, which fall flat, and why—and these dynamics will be critical to understand as the international community turns toward new challenges in taxing the digital economy.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

SL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The author is grateful for research funding provided by the Law and Economics Center at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT assisted in searching for "organization type" in the consultation letters. ChatGPT additionally assisted in formatting the tables and in properly formatting the reference list to MLA specifications (I provided the references).

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1561283/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Note that this article examined consultation letters for the December 2022 draft Multilateral Convention (MLC), including alignment with DST’s. However, this draft was considerably more technical than the previous two reports, and received far fewer responses.

References

Acemoglu, D. (2020). Andrea Manera, and Pascual Restrepo. (2020). Does the US tax code favor automation?. No. w27052. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of economic Research.

Akhmouch, A., and Clavreul, D. (2016). Stakeholder engagement for inclusive water governance: “practicing what we preach” with the OECD water governance initiative. Water 8:5. doi: 10.3390/w8050204

Avi-Yonah, R., Kim, Y. R., and Sam, K. (2022). A new framework for digital taxation. Harv. Int'l LJ 63:279. Available online at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/law_econ_current/222/

Ayres, I., and Braithwaite, J. (1992). Responsive regulation: Transcending the deregulation debate. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Eden, L. (2021). The simple analytics of pillar one amount a. Tax Manage. Int. J. 50, 137–142. Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3800017

Fink, S., Ruffing, E., Burst, T., and Chinnow, S. K. (2021). Less complex language, more participation: how consultation documents shape participatory patterns. Interes. Groups Advocacy 10, 199–220. doi: 10.1057/s41309-021-00123-2

Friedan, K., and Do, S. (2021). State adoption of European DSTs: misguided and unnecessary | tax notes. Tax Notes. Available online at: https://www.taxnotes.com/special-reports/nexus/state-adoption-european-dsts-misguided-and-unnecessary/2021/05/06/59p2l (Accessed June 5, 2021).

Friedan, K., and Lindhoml, D. (2023). State digital services taxes: a bad idea under any theory | tax notes. Tax Notes. Available online at: https://www.taxnotes.com/special-reports/digital-economy/state-digital-services-taxes-bad-idea-under-any-theory/2023/04/07/7g9bc (Accessed July 4, 2021).

Harpaz, A. (2021). Taxation of the digital economy: adapting a twentieth-century tax system to a twenty-first-century economy. Yale J. Int. Law 46:57. Available online at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/yjil46&div=7&id=&page=

Hsieh, H.-F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Ingold, K., Varone, F., Kammerer, M., Metz, F., Kammermann, L., and Strotz, C. (2020). Are responses to official consultations and stakeholder surveys reliable guides to policy actors’ positions? Policy Polit. 48, 193–222. doi: 10.1332/030557319X15613699478503

James, S., Pagliari, S., and Young, K. L. (2021). The internationalization of European financial networks: a quantitative text analysis of EU consultation responses. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 28, 898–925. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2020.1779781

Kidwell, L., and Lowensohn, S. (2019). Participation in the process of setting public sector accounting standards: the case of IPSASB. Account. Eur. 16, 177–194. doi: 10.1080/17449480.2019.1632466

Kovacev, R. (2020). A taxing dilemma: robot taxes and the challenges of effective taxation of AI, automation and robotics in the fourth industrial revolution. Ohio St. Tech. LJ 9:182. doi: 10.31979/2381-3679.2020.090204

Müller, R., Schoenrock, M., and Spengel, C. (2022). How to Move Forward with Country-by-Country Reporting?: A Qualitative Content Analysis of the Stakeholders’ Comments in the OECD 2020 Review (SSRN Scholarly Paper 4194628). Paris: OECD.

Navarro, A. (2021). The allocation of taxing rights under pillar one of the OECD proposal (SSRN scholarly paper 3825612). Paris: OECD.

Oberson, X. (2025). “Taxation of artificial intelligence” in Research handbook on the law of artificial intelligence. eds. W. Barfield and U. Pagallo (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 636–651.

OECD (2015). Addressing the tax challenges of the digital economy, action 1—2015 final report, OECD/G20 base Erosion and profit shifting project. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2018). Tax challenges arising from digitalisation – Interim report 2018: Inclusive framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 base Erosion and profit shifting project. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2022). Pillar one – Amount a: Draft multilateral convention provisions on digital services taxes and other relevant similar measures. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Olbert, M., and Spengel, C. (2019). Taxation in the digital economy—recent policy developments and the question of value creation. Int. Tax Stu. 2, 1–15. doi: 10.59403/1rhzhcm

Pagliari, S., and Young, K. (2016). The interest ecology of financial regulation: interest group plurality in the design of financial regulatory policies. Soc. Econ. Rev. 14, 309–337. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwv024

Pedersen, M. J. (2021). Making better regulation: how efficient is consultation? Scandinavian journal of public administration, 25(1). Art 25, 43–57. doi: 10.58235/sjpa.v25i1.7129

Procházka, P. (2020). Stakeholder contribution to global tax governance: analysis of public comments on OECD/G20 BEPS action plan [draft for 33rd EBES conference Madrid]. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Petr-Prochazka-5/publication/331715780_Stakeholder_contribution_to_global_tax_governance_Analysis_of_public_comments_on_OECDG20_BEPS_Action_Plan/links/5ca2196fa6fdcc1ab5ba225d/Stakeholder-contribution-to-global-tax-governance-Analysis-of-public-comments-on-OECD-G20-BEPS-Action-Plan.pdf (Accessed August 18, 2025).

Keywords: international tax, international tax avoidance, artificial intelligence (AI), tax justice, pillar 1

Citation: Listokin S (2025) New rationales for taxing the digital economy: lessons from the OECD Pillar One consultations. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1561283. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1561283

Edited by:

Najabat Ali, Soochow University, Suzhou, ChinaReviewed by:

Liziane Meira, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, BrazilSonia Elizabeth Ramos-Medina, Autonomous University of Sinaloa, Mexico

Copyright © 2025 Listokin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Siona Listokin, c2xpc3Rva2lAZ211LmVkdQ==

Siona Listokin

Siona Listokin