- Department of Police Practice, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

Introduction: This study revisits the debate surrounding the security-development nexus by analyzing the motivations and impacts of two key insurgent groups: Boko Haram and the Niger Delta Avengers in Nigeria. It seeks to understand how socio-economic, ideological, and governance-related factors contribute to the existence of both groups in similar and/or different ways, and the overall implications for sustainable peace and development in Nigeria.

Methodological and theoretical frameworks: The research employs a qualitative methodology, utilizing both primary and secondary data sources, including academic literature, policy reports, media analysis, and semi-structured interviews with experts. Thematic analysis is conducted within the conceptual framework of the “Greed, Need, and Creed Spectrum,” which categorizes the drivers of conflict into economic incentives (greed), socioeconomic deprivation (need), and ideological or religious motivations (creed). In addition, this study combines the analytical potential of the Rational Choice and Root Cause theories (2RCs) to illuminate how the greed-need-creed spectrum can help in deepening the understanding of the security-development nexus in Nigeria, especially regarding the two insurgencies in question.

Results: Findings reveal a complex interplay between economic inequality, underdevelopment, and governance deficits across Nigeria’s geopolitical zones. Boko Haram’s insurgency is primarily fueled by religious ideology and socio-political exclusion in the Northeast, while the Niger Delta Avengers capitalize on environmental grievances and resource control claims to justify economically motivated sabotage. Meanwhile, socioeconomic deprivation serves as a foundational grievance that enables both groups to mobilize support. Informed by the 2RCs, the study highlights that responses rooted solely in militarization fail to address the deeper structural causes of these similar but different insurgencies, considering relevant contextual factors. It re-echoes the calls for a shift toward integrated policy approaches that target the root causes of insecurity, including poor governance, youth unemployment, and environmental injustice, while considering the regional peculiarities of both insurgencies and like-minded groups.

Conclusion and recommendation: This study essentially underscores how the Greed-Need-Creed framework provides a valuable perspective necessary for crafting multidimensional counter-insurgency strategies that align national security with human development objectives, including participatory governance, localized economic development, and community-driven deradicalization programs.

1 Introduction

A large body of studies has explored the relationship between insurgency/terrorism and underdevelopment, especially following the increase in terrorism and insurgency since the 9/11 attacks, producing varying conclusions (Amer et al., 2013). On the one hand, insurgency and terrorism have been predicated on socioeconomic factors such as education, poverty, and inequality (Krieger and Meierreiks, 2015). On the other hand, this relationship is rejected as lacking empirical evidence and is even considered a myth (Piazza, 2006). The role of misinterpretation of religion, particularly Islam, in driving terrorism has also shaped the security development discussion, especially studies that examine the ideological side of the issue (Bravo and Dias, 2006). While there is a wealth of insights from these studies, there is still a lack of consensus on how to best understand how underdevelopment correlates with insecurity, especially one posed by non-state actors using terrorist tactics. This lack of agreement is not surprising, given notable nuances in the debate and the significance of context, which is often overlooked in cross-sectional studies that rely heavily on aggregated quantitative data (BjØrgo, 2005). This study adds to the discourse by highlighting the importance of context in understanding the complexities of the security-development nexus in Nigeria.

Nigeria is facing significant security challenges from various sources, including terrorism by non-state armed groups like Boko Haram and its splinter groups in the northeast, street gangs and cultists in the southwest, Biafran separatists in the southeast, farmer-pastoralist conflicts in the northwest and Middle Belt, oil militancy in the Niger Delta, and maritime piracy in the Gulf of Guinea (Adetiba, 2022; David, 2024). As a result, Nigeria is considered one of the most insecure states in the world. Some scholars argue that the militants have been successful because some parts of Nigeria have been doing poorly, while critics at least acknowledge an inherent complexity that transcends poverty. The study seeks to answer the question: how do socioeconomic factors explain the Boko Haram terrorism and the militancy in the Niger Delta region with references to the security-development discourse? To address this question, both groups are assessed on a “creed-need-greed” spectrum, which helps illuminate our understanding of their similarities and differences within the broader security-development discourse.

Although only Boko Haram was formally proscribed as a terrorist organization, Nigeria’s 2011 Terrorism Prevention Acts categorizes the activities of both Niger Delta Avengers (the latest group in the long chain of militants in the Niger Delta region) and Boko Haram as “acts of terrorism” defined as:

an act which is deliberately done with malice, aforethought and which: (a) may seriously harm or damage a country or an international organization; (b) is intended or can reasonably be regarded as having been intended to - (i) unduly compel a government or international organization to perform or abstain from performing any act, (ii) seriously intimidate a population, (iii) seriously destabilize or destroy the fundamental political, constitutional, economic or social structures of a country or an international organization, or (iv) otherwise influence such government or international organization by intimidation or coercion…. (Adoke, 2013)

By implication, similar response strategies, especially heavy-handed military counterinsurgency, have been employed by the Nigerian government to combat both groups. The effectiveness of this approach has been questioned, considering the complexity of the causal drivers and regional peculiarities that shape the resistance (Aghedo and Osumah, 2014a, 2014b). This warrants a nuanced understanding of the similarities between the two groups or other similar rebel groups in terms of their overall motivations. While there are divergent views regarding what differentiates these groups, the convergence of the negative effects of both insurgencies on Nigeria’s overall development, which have also served as reinforcing factors over time, warrants a nuanced understanding of the issues of underdevelopment that underpin both. While Boko Haram is predominantly described in religious or ideological terms, many analysts and scholars believe that the group’s actions are rooted in a complex array of factors, including poverty, unemployment, marginalization, and a sense of political disenfranchisement (David, 2024). Similarly, in the Niger Delta region, poverty and economic marginalization have been major drivers of militancy.

Since virtually all past and present Nigerian presidents, as well as presidential aspirants, often allude to socio-economic solutions to these security crises, these policy orientations or dispositions must be based on an accurate diagnosis of the issues to be effective. Cognizant of Richardson’s apt observation that ‘until policy-makers can understand the root causes of terrorism, they will be unable to implement effective measures to prevent it, it is imperative to address the divergent views on the nature and causal motivation of the groups (Richardson, 2011). Hence, this analysis examines how Nigeria’s complex security-development dynamics manifest in these two insurgencies, for instance, by emphasizing the role of contextual factors. The study suggests that a lack of nuanced understanding undermines sustainable counterinsurgency (COIN) efforts and makes groups like the Niger Delta Avengers and Boko Haram an ever-present threat to the state and economy. The study evaluates the socioeconomic dimensions through the greed-need-creed framework, comparing these groups. Thus, following an outline of the methodology in the next section, a conceptual overview of security-development debates is presented to foreground this study’s theoretical framing. Subsequently, the results and discussion are presented, and relevant recommendations are offered in conclusion.

2 Materials and methods

This qualitative research study delves into the complex interplay of greed, need, and creed as a conceptual framework to enhance the understanding of various insurgencies in Nigeria, with a particular focus on Boko Haram and the Niger Delta Avengers. By exploring this triad, the research aims to reveal the nuanced relationships between these insurgent groups and the broader security-development nexus in the region. The dataset utilized in this investigation includes information gathered from a segment of a previous study conducted over the span of 4 years, from 2015 to 2019, which provides a longitudinal perspective on these dynamics. To ensure ethical rigor in the data collection process, ethical clearance was obtained (Cert UZREC 171110-030 PGD 2015/114). This includes both primary and secondary data analysis. The primary data collection involved semi-structured interviews with a diverse group of experts, whose insights come from both Nigerian and international contexts.

This approach allows for a multifaceted understanding of the socioeconomic dimensions influencing the insurgencies. It is crucial to note that the data have been revised and updated to reflect the ongoing transformation of Boko Haram, which has not only persisted over time but has also diversified into various affiliated insurgent factions. In contrast, the Niger Delta Avengers are characterized by a different trajectory, offering a compelling comparison between the two groups. Additional data sources include first-hand reports and materials pertinent to the relevant timeframe, such as publications by influential organizations and [inter]governmental agencies. Key contributors to this repository of information are the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the World Bank, UNESCO, the World Poverty Clock, and the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI). Furthermore, the research incorporates multimedia resources, including video documentaries that provide visual context to the activities and influences of the insurgent groups.

The analysis also draws from reports published in mainstream media, policy briefs, and analytical documents produced by various think tanks, enriching the understanding of the challenges posed by these insurgencies. The theoretical framework is reinforced by insights gleaned from an extensive review of the existing literature, including published journal articles, authoritative books, and relevant academic dissertations focused on security issues in Nigeria. To effectively communicate the findings, descriptive statistics such as tables and charts are incorporated into the study. These visual aids complement the thematic content analysis, enabling a clear presentation of the data and supporting the overarching narrative of the research.

3 The complexity of security-development debate

The link between terrorism and socioeconomic factors like poverty, inequality, exclusion, and education, both at individual and collective levels, is still hotly contested despite various studies in these areas in the past decades (Piazza, 2011). Some studies challenge the idea that poverty causes terrorism, showing that cross-national data analysis reveals that underdeveloped countries with poor socioeconomic conditions, as measured by macroeconomic indicators, are not more likely to be prone to terrorism than middle or high-income countries (Abadie, 2006; Botha and Abdile, 2016). Accordingly, Freytag et al. (2010) argue that the notion of a link between socioeconomic conditions and terrorism is based on faith rather than scientific evidence. This viewpoint is reinforced by the fact that the 9/11 perpetrators were “middle-class, well-educated individuals led by a wealthy religious extremist” (Burgoon, 2006). Similarly, Schmid and Jongman (2005) maintain that a range of socio-economic indicators—illiteracy, infant mortality, and gross domestic product per capita—are unrelated to involvement in terrorism.’ Accordingly, some have questioned the socio-economic argument for both Boko Haram and the Niger Delta uprising, pointing to other factors such as politics, religious fundamentalism, and cultural factors for Boko Haram and factors such as environmental degradation, politics, and intra-ethnic tensions (among others) for the Niger Delta crisis (Alozieuwa, 2012).

While the nexus remains inconclusive due to its complexity, the socioeconomic causal argument is still popular among scholars and policymakers worldwide (USAID Policy, 2011). The importance of lack of development in the underlying factors that enable insurgency and terrorism is recognized, and this view has been applied in understanding modern insurgent and terrorist movements such as Boko Haram and the militancy in Niger Delta, among others in Nigeria (Aghedo and Osumah, 2014b). The human development model highlights a comprehensive approach to poverty issues, including income and lack of choices and opportunities for a tolerable life, and recognizes that development can have significant implications for violent protest and conflict, even in Nigeria (UNDP, 2009). Conflicts often reverse development, but lack of development can also be a major source of grievances, fueled by poverty, inequality, marginalization, and exclusion, which can lead to violent outbreaks (Ocampo, 2004). As the former World Bank President James Wolfensohn argues, to prevent violent conflict, a comprehensive, equitable, and inclusive approach to development is necessary (Thomas, 2001).

These alternative conclusions reached in other studies are often based on the acknowledgment of the nuanced conceptualization of variables such as poverty and inequality (Nagel, 2011). For example, poverty is not limited to just a monetary definition, but is also seen as ‘the absence of acceptable choices across a range of life decisions, resulting in a severe lack of freedom.” (Foster et al., 2013). This perspective is supported by the Human Poverty Index, developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which views poverty as the inability to lead a long, healthy, creative life and to enjoy a decent standard of living, freedom, dignity, self-respect, and the respect of others (Oshewolo, 2010). Poverty can be measured either in relative or absolute terms. Absolute poverty refers to the severe deprivation of basic human needs such as food, water, and health, while relative poverty refers to inequality and relative deprivation where a minimum standard is guaranteed (Oshewolo, 2010).

In this regard, Thomas noted a correlation between the level of human security and the likelihood of conflict, including intra-state warfare. Li and Schaub (2004) used a pooled time-series analysis to find that developing countries are more susceptible to international terrorism attacks than developed OECD countries. The differences in socio-economic conditions in these two types of countries play a role in the encouragement or discouragement of terrorism. Bravo and Dias also found a negative correlation between terrorism and the level of development based on geopolitical factors in Eurasia, supporting the hypothesis that socio-economic variables are crucial to the proliferation of terrorism (Bravo and Dias, 2006). O’Neill observed that a significant improvement in the local population’s economic situation can make them less likely to support terrorist organizations. The decline in insurgency among Muslim youths in Mindanao, the Philippines, after investment from the US and Japan, and the decline in support for groups like the IRA, ETA, Red Brigades, Baader-Meinhof, November 17, and Japanese Red Army shows that this can be the case (O’Neill, 2002).

By the same token, USAID’s field research suggests that unmet socio-economic needs, regardless of actual material deprivation, may contribute to terrorism due to the related perception of marginalized populations who feel abandoned by the state and society (USAID Policy, 2011). While it’s not accurate to say that poverty exhaustively explains terrorism, it is also too simplistic to say that there’s a direct causal link between the two. Impliedly, the socioeconomic arguments for Boko Haram and the Niger Delta insurgency in Nigeria have been framed around this rather inconclusive nexus. It is against this backdrop that the greed-need-creed triad can further clarify the place of socioeconomic factors by underscoring both the similarities and differences between the two uprisings and highlighting other salient factors that solidify the perspective.

4 Theoretical framework

This study combines the analytical potential of the Rational Choice and Root Cause theories to illuminate how the greed-need-creed spectrum can help in deepening the understanding of the security-development nexus in Nigeria. The Rational Choice theory is a popular explanation for conflict and terrorism, particularly among economists and criminologists, which aims to shine a light on individual motivation for participation (Darcy and Noricks, 2009; Gupta, 2005). Accordingly, the motivation for terrorism is based on an individual’s cost–benefit analysis, where they weigh the benefits of participating in violent extremism against the costs (Darcy and Noricks, 2009). The benefits can be political, economic, social, or cultural/religious, and depend on the priorities of the individual or group. Its analytical contribution to this study rests in its ability to further disaggregate causal factors to the individual level, thereby reasonably accounting for why, despite general economic malaise, non-state actors may still choose not to participate in insurgency or/ terrorism. However, scholars have noted some limitations of rational choice. For instance, it has been noted that the limited benefits from collective violent activities to the individual and the ineffectiveness of their efforts when the group is large make the theory problematic (Gupta, 2005). In this regard, it is argued the theory fails to explain why individuals would participate in such activities from an economic perspective, suggesting that they are either irrational or have hidden motivations for sacrificing their wellbeing for the group’s objectives, despite receiving little personal benefit. Gupta argues that this traditional economic assumption of self-utility maximization provides a limited view of human rationality, which can lead to flawed policy prescriptions in addressing terrorism.

Regarding the root cause theory, Newman identifies several independent variables that play a role in explaining the occurrence of terrorism. These variables include poverty, population growth, social inequality and exclusion, loss of possessions, and political grievances, as well as oppression and human rights violations (Newman, 2006). The root cause theory complements socio-economic theories like relative deprivation, linking terrorism to poverty and inequality, and emphasizes addressing grievances that drive insurgency for long-term solutions. It also accounts for globalization and economic crises in contemporary conflicts. Combining root cause and rational choice theories (2RCs) explains Boko Haram and Niger Delta uprisings by integrating group inequality, private motivation, and social contract failure. This hybrid framework reveals the socio-economic nuances of these insurgencies, focusing on their similarities and differences within the greed-need-creed spectrum. In the case of Boko Haram, poverty, unemployment, low level of education, and inequality have been identified as significant factors that have contributed to the group’s emergence and persistence (Aghedo and Osumah, 2014a; David, 2013). This is observable elsewhere, for instance, in the attraction toward AQIM, considering the extreme poverty in the countries like Niger, Mauritania, and Mali where the group has its footholds (Okumu, 2009).

Northern Nigeria, where Boko Haram is primarily active, has long been one of the poorest regions in the country, with high levels of unemployment, low levels of education, and limited economic opportunities. Some Boko Haram ex-fighters admitted that they joined the group with the hope of economic opportunities (Botha and Abdile, 2016). The desire for material possessions is not the only driving force behind the seemingly irrational decisions of Islamist terrorists, including suicide bombers. References to the allure of heaven and rewards such as 72 virgins have also been identified as important factors in the cost–benefit calculations of these terrorists (Darcy and Noricks, 2009).

The benefit and/or cost analysis ought to be measured against the context of the general absence of freedom from fear and want. Considering the ineptitude of the government to provide security for the people, often the choice of participation is not entirely left to the people in the region in the face of threats from the sect for non-participation. The resultant coercive recruitment of youths in the locality is one step toward understanding the place of underdevelopment in aiding and abetting the movement. The rhetoric of heavenly bliss and the heroic feeling of bringing down the corrupt system provides a beneficial view for the largely poor local population in their decision-making process.

5 Results and discussion

5.1 Non-state terrorism in Nigeria: Niger Delta Avengers and Boko Haram

Despite the extensive literature on insurgency and insecurity in Nigeria, this analysis briefly overviews Niger Delta Militancy and Boko Haram terrorism to contextualize the discussion. Insurgency, present since the 1980s, has intensified over the last two decades. Militancy in the Niger Delta, marked by hostage-taking, kidnappings, and attacks on oil facilities, has severely disrupted oil production and posed ongoing threats to peace and stability in southern Nigeria. In the 1990s, after the dust from the Nigerian Civil War appeared to have reasonably settled, various militia groups gradually [re]surfaced. In effect, less than a decade between 1990 and 1999, over 24 ethnic-based minority rights groups rose in the region (Adejumobi, 2003; Tenuche and Achegbulu, 2020). For instance, a study conducted in 2007 in Delta states revealed ‘forty-eight recognizable groups in the Delta State alone, boasting more than 25,000 members and with an arsenal of approximately 10,000 weapons’ (Asuni, 2009). Similarly, the study claims there may be ‘up to 60,000 members of armed groups in the Niger Delta as a whole’ (Ikelegbe, 2001).

These various groups’ agitations arise from the region’s long history of resource-related conflict, dating back to 1894 when King Koko of Nembe resisted attempts to exclude the Nembe people from the palm oil trade. However, the region’s prominence as a source of global energy supply since 1956 has brought oil-related resistance to the forefront. In 1996, the Niger Delta Vigilantes, led by Isaac Jasper Adaka Boro, staged a 12-day revolution against oil exploration in the region, with the goal of secession and the establishment of the Niger Delta Republic. Despite being overcome by national security forces, the use of amnesty to deal with troublemakers rather than the underlying issues in the region was established. Scholars have thus classified the wave of insurrection in the region into three, with the first wave led by Isaac Adaka Boro in February 1966, the second by the Movement for the Emancipation of Niger Delta (MEND), and the third by the Niger Delta Avengers (NDA).

Like MEND, the Avengers also highlight the government’s disregard for the people in the Niger Delta. However, MEND’s use of the environmental justice frame was overshadowed by the ‘imperative of violence master frame’ (Oriola and Adeakin, 2018). The Avengers, as the latest [third] wave continuing the unfinished struggles, focus on four entities—transnational oil corporations, the Nigerian government, political elites from the Niger Delta, and key players from the second wave of the insurgency led by MEND. They use an injustice frame to assign blame for the problems in the Niger Delta, emphasize the poor conditions of the people, provide justification for their actions, and motivate their followers and supporters (Agbana, 2022). The framing also incorporates a transnational discourse of social justice and fairness, given especially the role of multinational oil companies in the historical underdevelopment of the region that continues to play out (Agbana, 2022; Mukhtar and Abdullahi, 2022).

Furthermore, the Avengers have various grievances against the Nigerian government including the use of the military as ‘thugs’ during elections in the Niger Delta, extrajudicial killings during military operations, involvement of top military officials in illegal oil bunkering and criminal enrichment, lack of respect for Nigeria’s constitution with regards to federalism and freedom of speech, and neglect of the Niger Delta region for over 50 years and failure to implement development policies. This historical context underscores the need to address the root socio-economic drivers of conflict in the region (Agbana, 2022).

Meanwhile, the dramatic rise, especially in 2009, of the Islamist group, Boko Haram, brought terror campaigns to the northeastern part of the country, spreading to other northern states. Boko Haram is a non-monolithic group with a highly diffused organizational structure, believed to have at least six splinter groups. The most well-known is Ansaru, or Jama’at Ansar al-Muslim, which seeks to reinstate the Caliphate across Nigeria, Cameroon, and Niger, like Boko Haram. Given is overarching Islamist perspective of Boko Haram, its socio-economic drivers have been hotly debated in policy and academic circles (David, 2013). In what follows thus, the socio-economic predicates of the sect are discussed to present a nuanced understanding of its similarities to and differences from the militancy in the Niger Delta region. Especially, within the greed-need-creed spectrum.

5.2 Socio-economic deprivations and low human development

The notable shift toward a multidimensional understanding of development from the mono-cultural perspective of modernization and Westernization has humanized security discourse, rendering it more relevant to the focus of this study (Sen, 1999). Sen’s definition of development as a process of expanding real freedoms that people enjoy, which requires the removal of major sources of un-freedom, that is, freedom from want and fear, is central to security in Nigeria (Mukhtar and Abdullahi, 2022). Such ‘unfreedom’ as unemployment, poverty, tyranny, poor economic opportunities, systematic social deprivation, and neglect of public facilities have been shown to matter in the understanding of human security (Alkire, 2002). This human-centered approach illuminates the security-development nexus in Nigeria’s insurgencies since poverty is a lack of human development.

Back in 2009, when Boko Haram first became violent and aggressive, it was noted that the north-eastern region of Nigeria was the least developed area in the country, with a Human Poverty Index (HPI) of 48.9 and a corresponding low Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.332 (Mukhtar and Abdullahi, 2022). The HDI is calculated based on indicators such as life expectancy at birth, mean years of schooling, and gross national income (GNI) per capita. These indicators are then standardized and combined to generate an overall score, which ranges from 0 to 1, with a higher score indicating higher levels of human development (cited in David, 2019). Relative to the above holistic view of human development, the reductive money-metric perspective on poverty, which often focuses on the material and quantifiable aspects, does not fully capture the qualitative aspects of poverty, which is why it tends to polarize the debate on the poverty-terrorism correlation. Let us now turn to how poor economic opportunities and socio-issues manifest at both group and individual levels in terms of motivations to join the Boko Haram or Niger Delta militancy.

5.2.1 Unemployment, poverty, and education

One of the key measures of economic development in a country is the economic productivity of the populace. Evidence-based direct conversations with violent youths show that there is no clear-cut relationship between unemployment and insurgency (Mercy Corps, 2016). Motivation to participate in insurgency varies from person to person, as individuals who have decent jobs may still be attracted to terrorism. For instance, when Mercy Corps mapped the demographic profiles of former Boko Haram members interviewed, they discovered that ‘some had jobs, and others did not’ (Mercy Corps, 2016; Proctor, 2015). Hence, the association between unemployment and these insurgencies requires deeper examination because ‘employment status alone does not appear to determine whether a young person is likely to join an insurgency’ (Mercy Corps, 2016; Proctor, 2015).

Nevertheless, material gains have been shown to shape the rise and persistence of the insurgency by Boko Haram. Among these are the proceeds of looting, bank robbery, extortion, stealing from shops and community farms, financial compensation for carrying out attacks, and proceeds from ransoms. Correspondingly, the motivation for the violent and virulent behavior of Boko Haram in 2009 was largely driven by the immediate financial benefits of monetary inducement and looting opportunities. This enticed widespread support for the group’s attacks on non-indigenous people, as Boko Haram’s members hoped to loot or take over the victims’ businesses and assets after the attacks. An earlier study shows how young people were paid as little as N5,000 (i.e., approximately $23) to burn down schools at the group’s behest (David, 2013). This form of inducement was confirmed by two of the respondents (Youth1, 2016).

Respondents from Borno indicated that their peers cooperated with Boko Haram for as little as N2,000 (that is approximately $9 as of June 2016 when the interview was conducted). One respondent confirmed that financial inducements were used to lure the largely poor residents of Maiduguri into cooperating with Boko Haram. They noted that at some point, ‘there was a lot of money being pumped into these things…there was a price tag on each soldier. If you kill one soldier, you have a million Naira (i.e., approximately $4,329 as of June 2016). Yes! A million Naira was the price tag on each Nigerian soldier’ (Peace-builder3, 2016). The case of an 18-year-old female suicide bomber, Amina, who confessed to being paid a meager N200 (less than 1$) to detonate a bomb in Maiduguri, highlights how financial incentives are still being used by extremist groups like Boko Haram. Accordingly, the BBC’s reporter, Farouk Chothia observes that the sect’s appeal in Northern parts of the country, ‘where poverty and underdevelopment are most severe’ is understandable (Chothia, 2012).

Studies also observed that Boko Haram’s founder, Yusuf, was initially motivated by financial compensation. Despite becoming reluctant to support the group at some point, its sponsors ‘worked hard to win him back and heavily remunerated him financially, making life much easier for him and above the poverty line’ (Chothia, 2012). These various material benefits corroborate Botha and Abdile’s empirical findings that 5.88% were attracted to the group due to the employment opportunities that the group presented, while another 5.88% referred to feeling frustrated with life as contributing to their vulnerability to the organization (Botha and Abdile, 2016).

An empirical study conducted in 2012 on poverty incidence in Nigeria by senatorial zones also revealed widespread poverty, with a high of 74.5% across all senatorial zones in the northeast (Sowunmi et al., 2012). The study found that poverty is more entrenched in rural areas and that the Northeast and Northwest zones, which are predominantly rural, had more than 34% of their population classified as core poor compared to those in urban areas (Omotola, 2008). Additionally, the national poverty average was lower than that of states such as Adamawa (34.4%), Bauchi (43.9%), Taraba (36.1%), Yobe (49.6%), Kebbi (47.2%), Sokoto (55.2%), Kogi (61.1%), and Kwara (34.9%), all of which are in the Northern region (Omotola, 2008). This is hardly surprising given the overall economic outlook of Nigeria, which has deteriorated over the years.

The World Poverty Clock estimated that as of 2020, about 105 million people in Nigeria lived in extreme poverty, which represents about 50% of the country’s population, with the northern region generally having higher poverty rates than the southern region. Unsurprisingly, Botha and Abdile’s empirical study found that 15.13% of Boko Haram respondents joined the organization because of poverty. Understood against the backdrop of the severe problem of unemployment in Nigeria, it is plausible to argue that this economic measure is vital to the emergence and flourishing of the sect over the years.

In the Niger Delta region, poverty and economic marginalization have been major drivers of militancy. The Niger Delta is home to Nigeria’s oil industry, which has brought enormous wealth to the country but has done little to benefit the local communities. Many people in the Niger Delta live in poverty, with limited access to basic services such as healthcare, education, and clean water (Director2, 2016). Thus, a respondent maintained that the Niger Delta militants and Boko Haram insurgents have capitalized on this discontentment among the people to gain support (Peace-builder3, 2016). This dynamic affects the motivation of the terrorists, the support and sympathy of the populace, the attitude and disposition of security personnel, and the politicians’ proclivity to manipulate the situation, which ultimately contributes to the persistence of the attacks and violence. The economic benefit calculation in the Niger Delta includes the gainful operation of illegal refineries, and the vandalization of pipelines to extract crude oil or attract clean-up contracts.

These economic dimensions have given much credence to the poverty thesis of both insurgent groups. And though the southern region in aggregate terms may be considered to have lower poverty rates, the Niger Deltans have rightly blamed their poverty on the destruction of livelihood through oil exploration in the region. There are many ‘very poor’ communities in both the northern and southern regions. For instance, a 2015 study suggests a similarity between the membership following of both groups.

Boko Haram and Niger Delta militants are comprised mainly of the less privileged and poverty-stricken members of the society. The hotbed of Boko Haram in Nigeria is the region having high figures of people living below the poverty line according to NBS estimates’ similar finding by NBS reveals that over 70% of Niger Delta’s people consider themselves poor (Yahaya, 2015).

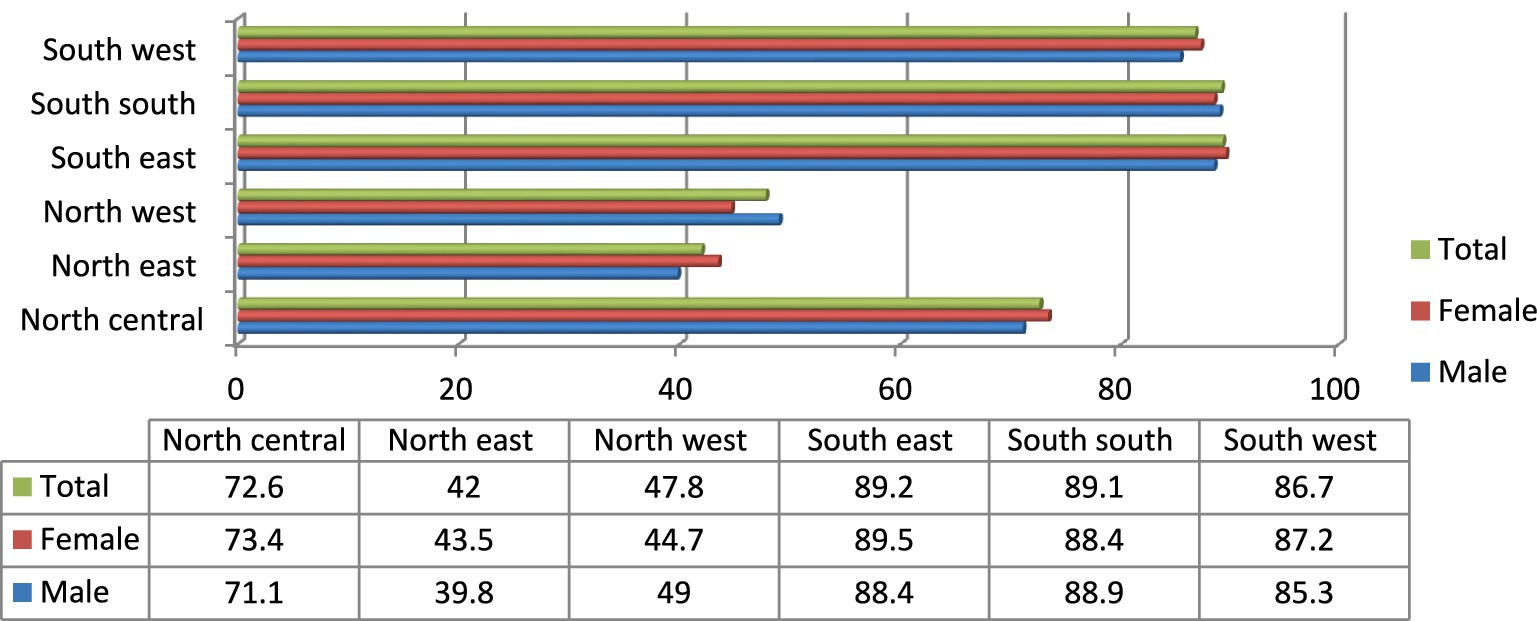

Furthermore, education is a crucial factor in the prevalence of terrorism, particularly when it comes to ideologically driven groups like Boko Haram. One argument suggests that the group is more likely to recruit individuals who lack education and critical thinking skills, which is a major problem in the northern region of Nigeria. In fact, as Figure 1 shows, education is significantly poorer in the north compared to the south, making it easier for Boko Haram to persuade individuals to join the movement without questioning their ideologies. Statistics from various reports indicate the gravity of the problem. For instance, a report by the International Crisis Group states that ‘Many youths in the north lack education, have few or no skills, and are hardly employable’ (ICG, 2014).

Figure 1. Percentage of children of primary school age attending primary or secondary school (net attendance ratio), geopolitical zones. Data source: UNDP (2009).

This finding is consistent with previous research, which highlighted the social phenomenon of sending millions of Almajiri students to Quranic schools far from their families, where they are required to beg for alms (Almajiranchi) or work as domestic help to pay for their upkeep (ICG, 2014). The northeast region of Nigeria is particularly affected, as data from the DHS Education Data Survey 2011 reveals. According to the report, two states in the north region, Borno and Zamfara, have the highest percentage of out-of-school children, with 12 and 68%, respectively. Moreover, 72% of children in Borno have never been to school, compared to just 4% in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT; Patrick and Felix, 2013). The report also indicates that only an average of 28 children out of over 120 attend school in Zamfara. Consequently, these out-of-school children become vulnerable to the teachings of radical instructors in Quranic schools, making them more susceptible to joining extremist groups like Boko Haram.

These figures highlight the extent of the problem in Nigeria and the urgent need to address the issue of education in the northern region to combat the prevalence of terrorism, especially when it comes to groups like Boko Haram. We now turn to how this neediness, in conjunction with greed and/or creed, shapes either of the groups in their regional peculiarity.

5.3 The greed-need-creed spectrum

The three broad perspectives in the literature regarding the relationship between poverty and conflict are cost-based, grievance-based, and greed-based (Goodhand, 2003). These categorizations resonate with the central arguments of greed theory by Collier and Hoeffler (2004) and grievance theories such as Tedd Gurr’s relative deprivation thesis (Gurr, 2011) ‘Individuals sometimes move toward or away from terrorist organizations in part according to whether personal-level opportunities exist’ (Darcy and Noricks, 2009). This personal benefit need not be limited to material benefits, as it can be ideological or spiritual. Thus, theories that attempt to reduce the cause of conflict to economic predation or need are limited in explaining the ideological and religious drive behind terrorism. The decision of individuals to participate in insurgency is influenced by a combination of grievances, greed, and belief systems. This study highlights the spectrum of motivations—greed, need, and creed—in the context of the two regional conflicts (2RCs), providing insight into conflicts driven by groups with political, ideological, and economic motivations. The framework captures the intricate interaction among these motivations in Boko Haram and Niger Delta militancy, illustrating how these motivations often overlap, particularly over time.

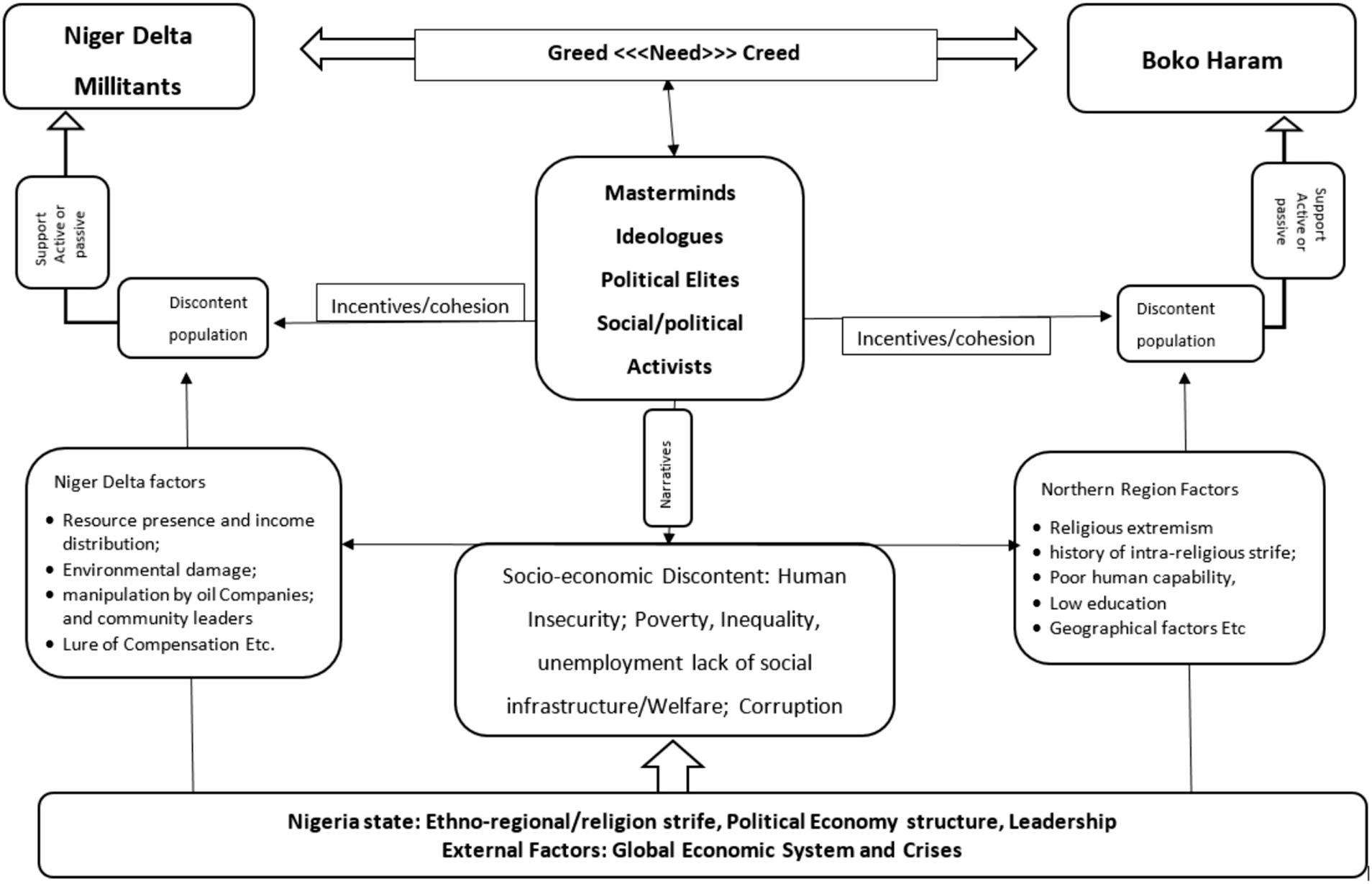

As depicted in Figure 2, there is a complex dynamic in the similarities and differences between the two groups. Considering contextual disparities, both insurgencies are fundamentally rooted in the severe underdevelopment of the Nigerian state, evident in its deficient political-economic structure and poor leadership, in conjunction with other global economic factors. The role of socio-economic factors is influenced by the socio-religious and political context in each region, leading to different objectives and operational methods employed by the insurgency.

Figure 2. Contextual similarities and differences in the socioeconomic drivers of Boko Haram and Niger Delta Militancy. Source: Author’s design.

For Boko Haram, religious ideology (creed) prioritizes the rule of Allah, the extermination of infidels, and promised rewards in the afterlife. Simultaneously, grievances from poverty and deprivation, combined with the prospect of personal enrichment (greed), influence decisions to support the group, either actively or passively. Absolute or relative deprivation drives individuals to join groups seeking change, making insurgency a “rational livelihood strategy” for the poor. These grievances, rooted in political repression and economic deprivation, fuel mobilization efforts and foster a sense of heroism among fighters. The disparity between Nigeria’s abundant resources and human development challenges underscores socio-economic deprivations, shaping insurgencies within regional contexts. The leaders and masterminds behind radical movements like Boko Haram thus recognize the socio-economic injustices that contribute to the neediness of the population and use a religious narrative/framing to present participation in Jihad as a heroic act with greater spiritual benefits than short-term costs.

Reports show that, besides addressing the lack of basic social amenities within some captured localities, the sect has occasionally provided material incentives (David, 2019). Beyond this, it uses force to create the perception of higher benefits over costs, through which it either appeals to the population’s grievances or indirectly dissuades them from resisting the group. Thus, considering the rational choice theory, force and threats are used to sway the cost–benefit analysis by the individual decision-makers, raising the cost of non-participation for the population. The success of this forceful approach lies in the fact that the population is often without adequate state security protection due to the enduring failure of governance that has severely underdeveloped the region. The same failures breed the political exploitation of the crisis by elites promoting their own ethnic or political interests, as demonstrated in their lack of determination and cooperation to address Boko Haram ab initio, and to date. Reports have shown that the sect is financed by political elites, and these have remained unpunished to date (David, 2019).

Similar dynamics are at play in the Niger Delta militancy, though the narrative, in this case, is not centered around creed, but rather on grievance and manifests in the greed of certain few actors (Director2, 2016; Peace-builder3, 2016). Unlike Boko Haram, the militants do not necessarily possess the drive for ‘supreme values’ or a ‘supreme trap’ that pushes members to extreme acts of violence. Arguably, the heroism once associated with the Niger Delta struggle, led by figures such as Ken Saro-Wiwa and others, has diminished over the years, especially as elite corruption and impunity have bolstered this shift from its initial ethnic-regional ideological impetus to more material and individualistic drive (Director2, 2016). Ogoloma argued that Boko Haram and Niger Delta insurgencies have different natures, with the former being insurrectional and terrorism-focused and the latter being militant due to their respective goals of religion and ethnonationalism (Ogoloma, 2013).

However, both insurgencies share socio-economic drivers that must be addressed for a sustainable resolution (Ayelowo, 2016). Indeed, the criticism that some terrorists are affluent and educated underestimates the ‘Robin Hood effect,’ which refers to the motivation to fight for fellow citizens rather than for one’s socio-economic according to Krueger and Laitin (2008). While the authors focused on transnational terrorism, their findings could be applied to domestic terrorism, as seen with Niger Delta and Boko Haram insurgents. These groups frame their objectives as liberation struggles against Nigeria’s oppressive and corrupt system, garnering active participation, logistical support, or passive sympathy from local populations. The socio-economic narrative exploited by rebel leaders heightens its relevance in clarifying the security-development nexus debate. While poverty and education levels are necessary but insufficient explanatory factors, their significance increases within these contextual dynamics, which are key to understanding the mobilization and support for such groups.

Unlike the Niger Delta militancy, however, the Boko Haram insurgency is presented in religious terms by the group itself, and this has resulted in its messaging being framed around the call for an Islamic state (David, 2019). The totalistic view of Boko Haram is in line with the notion that ‘religiously motivated groups are more inclined to view their struggle in absolute terms’ (Sederberg, 1995). This has made it appealing to those in the region facing socio-economic issues, who see it as a possible solution. A respondent noted that ‘religion was used as a means to garner support, however, the root cause of Boko Haram can be traced back to economic problems,’ highlighting that there is no distinction between northern and southern Nigeria in terms of political and economic injustices (Peace-builder3, 2016). Thus, the prevalent broad comparison of poverty levels between the North and South of Nigeria does not accurately reflect the prevalence of the Niger Delta insurgency in the wealthy South. This explains why respondents were divided on the socio-economic drivers of the Boko Haram insurgency, with some denying poverty as a cause and others seeing it as a key factor in the manipulation of youths in the region. For example, a respondent, who has lived in and studied both the North and South, argued that the socioeconomic marginalization in Northern Nigeria and its impact on Boko Haram is scarcely well captured in the literature (Researcher1, 2016).

Based on the foregoing, the spectrum suggests that other stronger factors like religion and culture in the north, have a significant influence on the Boko Haram insurgency without disregarding the socioeconomic impetus. Research corroborates the direct connection between economic motives and Boko Haram, demonstrating that (un)employment and education level do impact individuals’ motivations to join the organization (Botha and Abdile, 2016). Impliedly, despite the different approaches taken by both insurgencies, their underlying drivers converge in this intricate triad of greed, need, and creed as shaped by regional peculiarity. Goodhand’s assertion that the absolute level of poverty may be less significant than poor people’s expectations and a sense of grievance as triggers to violence sheds light on why poverty may not be as apparent in the Boko Haram insurgency (Goodhand, 2003). In this context, the romanticized narrative of the Caliphate acts as a motivating force for individuals whose material needs have been overlooked. Thus, socio-economic underdevelopment plays a significant role in the emergence and persistence of these insurgencies within their distinctly constructed regional environments. For instance, in the case of Boko Haram, widespread poverty and inequality perceived as ‘northern phenomena’ are among the grievances that some of the locals and members or sympathizers believe can be addressed by the reign of Allah through the Islamic Caliphate (David, 2019). Indeed, conditions of marginalization and frustration have drawn many young people to Boko Haram’s ideology and its promises of a better life.

Thus, on the Greed-Need-Creed spectrum, Boko Haram arguably leans more toward the creed end, while the Niger Delta insurgency aligns more with greed. In the Niger Delta, the initial demand for resource control has been overshadowed by the enrichment of elites who have hijacked the struggle. Despite ongoing grievances around economic marginalization, environmental degradation, and political exclusion, horizontal inequalities persist. As a few respondents highlighted, many militants have become wealthy, with elite corruption redirecting developmental aid and oil revenue to a privileged few, distorting the region’s original objectives (David, 2019). This has not only aggravated poverty in the region but also the sense of relative deprivation that underlies the angst that fuels anti-state resistance in the region. It is against such a backdrop that both insurgencies share some common socio-economic undertone.

It’s important to note that this distinction is not an absolute one, as instances of the economic and ideological drivers are noticeable in varying degrees in both rebellions (Nwankpa, 2014). Furthermore, the centrality of poverty (in terms of need) to both insurgencies makes their criminal dimensions a profitable venture from a utility maximization perspective in the rational choice sense, which can influence an individual’s decision to participate in violence or not. As Stevens and Cloete rightly pointed out regarding the economic causes of crime: firstly poor people desire the possessions of the rich, which can drive them to theft; secondly, the desire to possess certain riches, coupled with a lack of money, causes crime; and thirdly, peer pressure and the need to possess beautiful things drive crime (Stevens and Cloete, 1993). Some respondents from the Niger Delta region observed how youths in the Niger Delta openly admitted during a workshop with SACA that they vandalize oil pipes, a practice they alleged was usually in collaboration with oil company staff for the latter to secure new clean-up contracts, the benefits of which could trickle down to the youths (Director2, 2016). ‘With the lack of economic opportunity in the Niger Delta and constant reminders of the high-level fleecing of the region’s natural wealth by lawmakers, locals are left feeling that they are not only forced into criminal activities such as bunkering or piracy but also morally justified in committing them’ (McNamee, 2013).

Accordingly, scholars have suggested socio-economic development as an important strategy to address both insurgencies, despite their differences (Aghedo and Osumah, 2014a). Nwankpa (2014) also highlighted the importance of socio-economic interventions, such as infrastructure development, job creation, and poverty alleviation, to disincentivize impoverished youth from joining these groups, who share common grievances and/or can be attracted by certain incentives. The preceding underscores the importance of prioritizing development over the usual heavy-handed approach often adopted by the Nigerian state in its counter-insurgency. For instance, the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC) was allocated N69 billion for development, while N444 billion was allocated to security in the Niger Delta in hard power terms (Courson, 2009). This demonstrates that the allocation of funds favors security over development in the region. However, corruption and secrecy surround the security votes in Nigeria, leading to the embezzlement of large sums of money by governors who fail to secure their states (Omilusi, 2016). Despite the soaring insecurity, they often justify the expenditure on equipping the police and manning various checkpoints in their states, indicating that the security budget may not serve the majority’s interests. The Dasukigates, which involves the allegation of an estimated $2.1 billion meant for the procurement of arms and ammunition in the fight against Boko Haram insurgency being diverted and shared among government officials, is a case in point (Omilusi, 2016).

The “greed, need, and creed” analytical spectrum illustrates how socio-economic motivations manifest differently in each insurgency. In the case of the Niger Delta insurgency, these socio-economic drivers appear more readily identifiable as legitimate grievances compared to those in Boko Haram, which primarily manipulates these drivers for ideological motives and to garner support through financial incentives. This analysis underscores the intricate interplay among these factors in both insurgencies, carrying significant implications for the security-development discourse. Thus, outright dismissing the socio-economic driver as a mere myth is counterproductive to long-term peacebuilding and development, as the adverse effects of insurgency on human and social underdevelopment are likely to foster future conflicts rooted in profound underdevelopment.

6 Conclusion and recommendations

This study sought to demonstrate the contextual determinants of the security-development nexus, particularly focusing on how socio-economic conditions are non-negligible driving factors in the Boko Haram and Niger Delta insecurities, even though other factors such as religion and ethnonationalism play a critical role in each of the conflicts. The study employs the trinity of greed, need, and creed analytical spectrum to show how socio-economic motivation plays out in a similar but different manner in both insurgencies. This spectrum accounts for the relative perception or articulation of socioeconomic factors in each insurgency, particularly in terms of legitimacy. Despite the controversial poverty-terrorism nexus, evidence from interviews, available documentaries, and literature suggests that the socio-economic causes of the Niger Delta insurgency are more easily, and readily identifiable as legitimate grievances compared to those of Boko Haram. The latter’s socioeconomic factors are manipulated ideologically to mobilize support through monetary incentives and leveraging the vulnerability of the population, particularly due to a lack of education among its ranks of foot soldiers.

Analysis of the intricacies involved highlights the significance of economic deprivation and social marginalization of inner-city youths in the Kanuri city of Maiduguri as an important context for the initial mobilization of the Boko Haram insurgency (Office of the National Security Adviser, 2015). Thus, in addition to responding to identified underdevelopment indices in both regions, diplomacy is crucial to dealing with the persistent threats of militancy in Nigeria. The concept of diplomacy in conflict resolution must, however, not be reduced to mere negotiation or dialogue with the opposing party. Beyond these narrow interpretations, diplomacy is a critical aspect of governance that is used to regain government legitimacy and address issues of human rights abuses and reconciliatory approaches to ending violence. Diplomacy is often used interchangeably with governance in the 3D (development, diplomacy, and defense) conceptual framework, and it prioritizes the use of soft power to tactfully address grievances and incentivize need-based situations to receive government attention (David, 2024). Diplomatic governance can even create opportunities for creed-based groups to overcome their fears and close possibilities for greed-based leaders to achieve their goals by destroying other groups (Zartman, 2000).

Accordingly, the significance of diplomatic governance in addressing the complex dynamics of the Niger Delta and Boko Haram insurgencies cannot be overemphasized. The survival and persistence of any insurgent group, including the likes of NDA and Boko Haram, are often dependent on the quality of their leadership and the ability of the government to manage their actions. Effective diplomatic governance plays a key role in predicting and managing the actions of these groups in different situations. Thus, addressing the socio-economic drivers of political conflicts is an essential part of any strategy to address violence and promote peace. This should include efforts to improve access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities, as well as measures to reduce inequality and promote social inclusion. These efforts should be complemented by initiatives to promote good governance, human rights, and the rule of law, as these factors are also crucial to building peaceful and stable societies.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: University of Zululand library.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The University of Zululand, ethics committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to my Ph.D. Supervisors for their meaningful comments and reviews.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abadie, A. (2006). Poverty, political freedom, and the roots of terrorism. Am. Econ. Rev. 96, 50–56. doi: 10.1257/000282806777211847

Adejumobi, S. (2003). Ethnic militia groups and the national question. Working Paper 11/03. Available online at: https://socialsciencelibrary.org/political-science/international-relations/conflict-peace-and-security/war-and-conflict-resolution/ethnic-militia-groups-and-the-national-question-in-nigeria/

Adetiba, T. C. (2022). Public diplomacy and Nigeria’s response to its internal political crises. EUREKA Soc. Human. 6, 105–118. doi: 10.21303/2504-5571.2022.002574

Adoke, M. B. (2013). Terrorism (prevention) act 2011 (as amended). Abuja: Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Agbana, Z. E. (2022). The uprising militancy as it affects development in Nigeria (a case study of Niger Delta). Int. J. Peace Confl. Stud. 7, 78–89.

Aghedo, I., and Osumah, O. (2014a). Bread, not bullets: Boko haram and insecurity management in northern Nigeria. African Study Monogr. 35, 205–229.

Aghedo, I., and Osumah, O. (2014b). Insurgency in Nigeria: a comparative study of Niger Delta and Boko haram uprisings. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 50, 208–222. doi: 10.1177/0021909614520726

Alkire, S. (2002). Valuing freedoms: Sen’s capability approach and poverty reduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Alozieuwa, S. H. O. (2012). Contending theories on Nigeria’s security challenge in the era of Boko haram insurgency. Peace Conflict Rev. 7, 1–8.

Amer, R., Swain, A., and Öjendal, J. (2013). The security-development nexus: peace, conflict and development. New York: Anthem Press.

Asuni, J. B. (2009). Understanding the armed groups of the Niger Delta. New York: Council on Foreign Relations.

Ayelowo, M. (2016). Stemming the tide of terrorism in Nigeria: the imperatives. Available online at: eprints.covenantuniversity.edu.ng/6934/1/Main_Paper_Air_Cmdr_Ayelowo.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2017).

Botha, A., and Abdile, M. (2016). Getting behind the profiles of Boko Haram members and factors contributing to radicalisation versus working towards peace. Available online at: http://www.salvationarmy.org/isjc/03-10-16 (Accessed November 3, 2016).

Bravo, A. B. S., and Dias, C. M. M. (2006). An empirical analysis of terrorism: deprivation, Islamism and geopolitical factors. Def. Peace Econ. 17, 329–341. doi: 10.1080/10242690500526509

Burgoon, B. (2006). On welfare and terror social welfare policies and political-economic roots of terrorism. J. Confl. Resolut. 50, 176–203. doi: 10.1177/0022002705284829

Chothia, F. (2012). Who are Nigeria's Boko haram Islamists? British Broadcasting Corporation. Available online at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-13809501

Collier, P., and Hoeffler, A. (2004). Greed and grievance in civil war. Oxf. Econ. Pap.-New Ser. 56, 563–595. doi: 10.1093/oep/gpf064

Courson, E. (2009). Movement for the emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND): political marginalization, repression and petro-insurgency in the Niger Delta. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

Darcy, M., and Noricks, E. (2009). “Root causes of terrorism” in Social science for counterterrorism: putting the pieces together. eds. P. K. Davis and K. Cragin. (Pittsburgh: RAND Corporation).

David, J. O. (2013). The root causes of terrorism: an appraisal of the socio-economic determinants of Boko Haram terrorism in Nigeria (Unpublished Thesis MA Diss). Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal.

David, J. O. (2019). A comparative assessment of the socio-economic dimension of Niger delta militancy and Boko Haram insurgency: towards the security-development nexus in Nigeria. Ph.D Dissertation, University of Zululand. Unpublished.

David, J. O. (2024). The 3Ds (development, diplomacy, and defense) in Nigerian counterinsurgency: lessons from Uruzgan. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1283237. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1283237

Foster, J., Seth, S., Lokshin, M., and Sajaia, Z. (2013). Introduction: a unified approach to measuring poverty and inequality. Washington DC: The World Bank.

Freytag, A., Krüger, J. J., Meierrieks, D., and Schneider, F. (2010). The origins of terrorism cross-country estimates on socio-economic determinants of terrorism. Economics of Security Working Paper 27(27). Available online at: https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.354169.de/diw_econsec0027.pdf (Accessed March 4, 2016).

Goodhand, J. (2003). Enduring disorder and persistent poverty: a review of the linkages between war and chronic poverty. World Dev. 31, 629–646. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750x(03)00009-3

Gupta, D. K. (2005). “Exploring roots of terrorism” in Root causes of terrorism: myths, reality and ways forward. ed. T. Bjorgo. (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group).

Gurr, T. R. (2011). Why men rebel redux: how valid are its arguments 40 years on?. E-International Relations. Available online at: http://www.e-ir.info/2011/11/17/why-men-rebel-redux-how-valid-are-its-arguments-40-years-on/ (Accessed December 15, 2016).

ICG (2014). Curbing Violence in Nigeria (II): The Boko Haram Insurgency. Peace-builder 3. Brussels: International Crisis Group.

Ikelegbe, A. (2001). Civil society, oil and conflict in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria: ramifications of civil society for a regional resource struggle. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 39, 437–469. doi: 10.1017/S0022278x01003676

Krieger, T., and Meierreiks, D. (2015). Does income inequality lead to terrorism? Evidence from the post-9/11 era. Discussion Paper Series. Available online at: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/111351/1/827719736.pdf (Accessed June 7, 2016).

Krueger, A. B., and Laitin, D. D. (2008). “Kto-Kogo? A cross-country study of the origins and targets of terrorism” in Terrorism, economic development, and political openness. eds. P. Keefer and N. Loayza. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 148–173.

Li, Q., and Schaub, D. (2004). Economic globalization and transnational terrorism - a pooled time-series analysis. J. Confl. Resolut. 48, 230–258. doi: 10.1177/0022002703262869

McNamee, M. (2013). No end in sight: violence in the Niger Delta and gulf of Guinea. Jamestown Found. Terror. Monit. 11, 8–11.

Mercy Corps. (2016). “Motivations And Empty Promises”: Voices Of Former Boko Haram Combatants and Nigerian youth. Available online at: https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/Motivations%20and%20Empty%20Promises_Mercy%20Corps_Full%20Report_0.pdf

Mukhtar, J. I., and Abdullahi, A. S. (2022). Security-development nexus: a review of Nigeria’s security challenges. J. Contemp. Sociol. Iss. 2, 18–39. doi: 10.19184/csi.v2i1.25815

Nagel, J. (2011). Inequality and discontent: a nonlinear hypothesis. World Polit. 26, 453–472. doi: 10.2307/2010097

Newman, E. (2006). Exploring the "root causes" of terrorism. Stud. Conflict Terrorism 29, 749–772. doi: 10.1080/10576100600704069

Nwankpa, M. (2014). The politics of amnesty in Nigeria: a comparative analysis of the Boko Haram and Niger Delta insurgencies. J. Terrorism Res. 5, 67–77. doi: 10.15664/jtr.830

O’Neill, W. (2002). “Concept paper-beyond the slogans: how can the UN respond to terrorism?” in Responding to terrorism: what role for the United Nations? (New York: International Peace Academy), 18–26.

Ocampo, J. A. (2004). Multidimensionality of peace and development: a DESA perspective. New York: United Nations.

Office of the National Security Adviser. (2015). Violent radicalisation in northern Nigeria: economy & society. Policy Brief. Available online at: http://www.nsrp-nigeria.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/PB-5-Economy-and-Society.pdf (Accessed June 3, 2016).

Ogoloma, F. I. (2013). Niger Delta militants and the Boko Haram: a comparative appraisal. AFRREV IJAH Int. J. Arts Human. 2, 114–131.

Okumu, W. (2009). “Domestic terrorism in Africa: defining, addressing and understanding its impact on human security” in Domestic terrorism in Africa: Defining, addressing and understanding its impact on human security. ed. W. Okumu. (Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies).

Omilusi, M. (2016). The multi-dimensional impacts of insurgency and armed conflicts on Nigeria. Asian J. Soc. Sci. Arts Human. 4, 29–39.

Omotola, J. S. (2008). Combating poverty for sustainable human development in Nigeria: the continuing struggle. J. Poverty 12, 496–517. doi: 10.1080/10875540802352621

Oriola, T. B., and Adeakin, I. (2018). “The framing strategies of the Niger Delta avengers” in The unfinished revolution in Nigeria’s Niger Delta. (London: Routledge), 138–158.

Oshewolo, S. (2010). Galloping poverty in Nigeria: an appraisal of the government's interventionist policies. J. Sustain. Dev. Afr. 12, 264–274.

Patrick, O., and Felix, O. (2013). Effect of Boko Haram on school attendance in Northern Nigeria. Br. J. Educ. 1, 1–9. doi: 10.3750/AIP2010.40.1.03

Piazza, J. A. (2006). Rooted in poverty?: terrorism, poor economic development, and social cleavages 1. Terrorism Polit. Violence 18, 159–177. doi: 10.1080/095465590944578

Piazza, J. A. (2011). Poverty, minority economic discrimination, and domestic terrorism. J. Peace Res. 48, 339–353. doi: 10.1177/0022343310397404

Proctor, K. (2015). Youth & consequences: unemployment, injustice and violence. Available online at: https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/MercyCorps_YouthConsequencesReport_2015.pdf

Richardson, C. (2011). Relative deprivation theory in terrorism: a study of higher education and unemployment as predictors of terrorism. (Unpublished Thesis): New York University.

Schmid, A. P., and Jongman, A. J. (2005). Political terrorism: a new guide to actors, authors, concepts, data bases, theories, and literature. London: Transaction Publications.

Sederberg, P. C. (1995). Conciliation as counter-terrorist strategy. J. Peace Res. 32, 295–312. doi: 10.1177/0022343395032003004

Sowunmi, F., Akinyosoye, V., Okoruwa, V., and Omonona, B. (2012). The landscape of poverty in Nigeria: a spatial analysis using senatorial districts-level data. Am. J. Econ. 2, 61–74. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20120205.01

Stevens, R., and Cloete, M. G. T. (1993). Introduction to criminology. Southern Africa: International Thomson Publishing.

Tenuche, M. S., and Achegbulu, J. O. (2020). Restructuring: resolving the national question in Nigeria. Glob. J. Polit. Sci. Admin. 8, 1–21.

Thomas, C. (2001). Global governance, development and human security: exploring the links. Third World Q. 22, 159–175. doi: 10.1080/01436590120037018

USAID Policy (2011). The development response to violent extremism and insurgency. Putting principles into practice. Available online at: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pdacs400.pdf (Accessed January 5, 2016).

Yahaya, A. (2015). Analysis of the economics of terrorism in Nigeria: Boko Haram and Movement for Emancipation of the Niger Delta in perspective Eastern Mediterranean University. Gazimagusa.

Keywords: security-development nexus, Boko Haram, Niger Delta Avengers, greed-need-creed spectrum, sustainable peace, governance

Citation: David JO (2025) Boko Haram and Niger Delta Avengers: unraveling the greed-need-creed spectrum in Nigeria’s security-development nexus. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1562472. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1562472

Edited by:

Friedrich Plank, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, GermanyReviewed by:

Sulaimon Adigun Muse, Lagos State University of Education LASUED, NigeriaBarkhad M. Kaariye, ARDAA Research Institute, Ethiopia

Copyright © 2025 David. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: James Ojochenemi David, b2pvY2hlbmVtaWRhdmlkQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; ZGF2aWRqb0B1bmlzYS5hYy56YQ==

James Ojochenemi David

James Ojochenemi David