- Centre for Global Studies, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada

This manuscript examines the transformation of centre-right politics in Germany and the United Kingdom, focusing on how “culture wars” rhetoric and identity politics have influenced the political strategies of the CDU (Christian Democratic Union) and the UK Conservative Party. It explores how these parties have responded to the rise of right-wing populism, prominently through the framing of cultural issues such as migration, national identity, and gender politics. While the UK Conservatives have embraced nationalist-populist rhetoric, especially during the Brexit campaign, the CDU has maintained a more policy-driven, pragmatic approach. The article argues that while identity politics can be a powerful tool for voter mobilization, it risks alienating moderates and deepening societal divisions. Reflecting on the impact of the “cultural wars” rhetoric on competitive party politics, the study highlights the challenge for centre-right parties in balancing the demands of an increasingly polarized electorate with the need to preserve their traditional policy-focused, moderate conservatism in the face of populist pressures.

Introduction

“Culture wars” and their polarizing effects have transformed party politics in Western democracies. This profound change is evident in how parties conduct their political mobilization, communicate publicly, and define their core political ideologies. In public debates, “culture wars”—primarily associated with how American politics has increasingly been defined by two competing and seemingly incompatible views of the country’s identity and cultural values since the 1990s (Hartman, 2019; Hunter, 1991, 1996)—have become a global phenomenon shaping political identities and conflicts. At their core, “culture wars” are less about specific policy agendas and more about competing visions of what a society ought to look like in terms of its fundamental values and comprehensive worldview about the future of the country. These “culture wars” address the foundational collective identity of social groups, establishing an ideational framework upon which political preferences and key policies are formulated (Gidron and Ziblatt, 2019).

This article focuses on the impact that “culture wars” have had on competitive party and electoral politics. More specifically, I discuss the degree to which the polarization of American politics (Hartman, 2019) is shaping the European context, particularly the political mobilization of the centre-right (Ozzano and Giorgi, 2015). With the rise of the populist-nationalist right in many European countries, mainstream conservative or Christian Democratic parties have come under considerable pressure to readjust their strategies to ensure their electoral competitiveness (Art, 2018; Vachudova, 2021). Europe’s centre-right parties struggle to maintain their traditional political identity—predominantly defined by neoliberal economic policies and conservative social values—while remaining appealing in a rapidly changing political environment. The resurgence of anti-elitist, anti-immigrant political entrepreneurs has posed significant challenges to their conservatism. In this respect, this article also examines how the polarization over cultural cleavages—conceptualized as the “cultural backlash” (Norris and Inglehart, 2019)—has transformed conservative positioning in electoral politics.

Empirically, I analyze the political discourse of Germany’s Christian Democratic Party (CDU) and the United Kingdom’s Conservative Party (officially the Conservative and Unionist Party). Germany and the UK were deliberately chosen as similar cases with notable stability and continuity in electoral politics, and for the prominent role the centre-right plays in both national contexts (Corduwener, 2016). Both parties have avoided the fate of other conservative parties across the continent. For example, in France and Italy, the centre-right has seen an end to some mainstream parties that shaped much of the post-war decades, leading to a thorough reconfiguration of the party system (Anderson, 2023; Donà, 2022). In contrast, Germany and the UK have not experienced far-reaching institutional changes that have transformed party politics (Mair et al., 2004). For instance, in 2017, March concluded that the “much-touted populist Zeitgeist in the United Kingdom barely exists” (March, 2017: 282).

Indeed, the German and British centre-right have retained a substantial amount of electoral support and have formed long-lasting governments (the CDU from 2005–2021 under Angela Merkel, and the Tories from 2010 to 2024 under a range of prime ministers). At first glance, one might assume that both parties would be largely immune to the populist agenda, regularly associated with the polarizing drive of “culture wars.” However, both the British Conservative Party and the German Christian Democrats have had to contend with competition from the far-right (most prominently, the United Kingdom Independence Party, UKIP, now Reform UK since 2021, and the Alternative für Deutschland, AfD). Right-wing populism’s identity-based, culturally framed political campaigns have challenged how the centre-right positions itself, in light of these political contenders and their systematic appeal to cultural cleavages and identity politics.

This article investigates the degree to which the political mobilization and discourse of the centre-right in the UK and Germany have adopted and utilized elements of “culture wars” rhetoric. As established political parties, how have the Conservative Party and the CDU reacted to the growing prominence of culturally framed issues (“wokeness,” sexual orientation, gender politics, abortion, national identity, etc.) in their respective electoral campaigns? The article empirically examines the discursive practices of the centre-right during their national electoral campaigns over the past two decades.

The analysis proceeds in two steps. First, the article presents the results of a discourse analysis regarding the prominence of themes in electoral campaigns closely related to “culture wars.” Second, it presents the results of a qualitative textual analysis of the framing strategies that inform the discursive practices in these thematic fields. This interpretative investigation sheds light on how, and to what extent, symbolic and emotive approaches to political communication have gained a notable foothold in centre-right electoral politics. The findings of this analysis offer insights into the increasing prominence of divisive cultural issues in British and German competitive party politics and the role conservative parties play in promoting or containing them. In the concluding section, I will address the driving forces behind the growing salience of “cultural wars” rhetoric and what might account for the difference between both conservative parties. Interpreting the findings in a broader comparative framework, I argue that the temptation to engage in divisive identity politics has the potential to fundamentally transform the electoral politics of Europe’s conservatism.

Cultural wars rhetoric and populist identity politics

Party politics is in constant flux; yet the nature of scope of this change varies substantially. Electoral strategies need to adapt to changing socio-economic realities, and new policy challenges have the potential to transform traditional party positions. Yet, what we have witnessed over the past two decades is a degree of profound change in party politics that would have been almost impossible during the post-war decades. During this period, Western Europe was characterized by extraordinary stability in terms of party formations and the core political identities they represented (Bértoa and Enyedi, 2021). Even the rise of smaller parties, such as the Greens, did not challenge the overall architecture of traditional party politics, nor the ideological and key policy positions promoted by their representatives.

However, over the past 10–20 years, we have witnessed changes in party politics that are transformative in a radical sense (Zulianello, 2020). For instance, in Italy, the parties that shaped the country’s politics for decades have either disappeared or morphed into distinctly different party formations. Emanuele and Chiaramonte (2020) refer to this as the “de-institutionalization of the Italian party system.” One key driving force behind this transformation has been the declining trust in established elites, accompanied by the resurgence of right-wing populism or nationalism as an anti-elitist political force (Chiaramonte et al., 2022). This anti-establishment resurgence has undermined the political capital and, in many cases, the very existence of traditional political parties on both the centre-right and centre-left.

More central to the focus of this article, conservative parties have had to contend with the ideological challenge of right-wing populism, which I consider to be more than just an “ideologically thin” anti-elitist impulse (Schroeder, 2020). Its core claim is to provide a more direct and authentic voice to the people, who are portrayed as being deprived by established elites. In this context, the reference to the “sovereign people” or “sovereignty” is a prominent feature of populist political campaigns (Breeze, 2019). This rhetoric does not occur by accident. First, the claim to restore the “will of the sovereign people” speaks to populist opposition to internationalization and globalization. Slogans such as “America First,” “France First,” and “Italy First” conjure the notion of a nation-state with a clearly defined political community, protected from the threats and uncertainties associated with a globalizing world.

In this respect, the evocation of sovereignty as a mode of organizing the political commons reflects the scholarly debate on the declining power of the nation-state in an increasingly cross-border and globalized environment. Discursively, contemporary populism mobilizes the idea of the territorially delineated nation-state, demarcating the political community and promising protection to its citizens (Kallis, 2018; Schmidtke, 2015). Populist political campaigns often construct a dramatized contrast between the supposedly simple and protected world of the sovereign nation-state, on the one hand, and the uncertainty and threats associated with the international world, on the other (see: Stavrakakis, 2014). The “culture wars” rhetoric plays a central role in this context, providing the cultural underpinning for notions of a community depicted as being deprived of its sense of identity and security.

Second, populists portray themselves as the guardians of the “will of the people,” referencing the tradition of a less state-centric notion of “popular sovereignty” with an emphasis on political struggles and legitimacy. Blühdorn and Butzlaff (2019, 194) describe this as a “discursive arena for the performance of sovereignty” that populist actors employ in their political rhetoric to boost their democratic legitimacy and broader popularity. Populist parties mobilize the notion of popular sovereignty, asserting to advocate for the silent majority. As their champions, these parties claim to represent a polity deprived of its voice and the means to defend its fundamental interests. From this perspective, these political actors thrive on distinguishing themselves from old-style political parties, like those of the centre-right, which they accuse of being unable or unwilling to defend the “true interests of the people.” They have popularized “culture wars,” whose modus operandi relates to irreconcilable cultural or political identities of social groups.

It is within this logic of “popular sovereignty” as a mode of political contestation and struggle that populist actors make explicit reference to an essential alienation from the polity and its modes of self-governance. Mair (2006, 25) spoke of “a notion of democracy that is being steadily stripped of its popular component—democracy without a demos.” The idea of “popular sovereignty” allows populists to challenge the political establishment, postulating that those in power lack the proper consent of the citizens. In response, they use popular sovereignty as a political tool to extract rights and privileges from unresponsive elites. Such a basic democratic claim—the invocation of an ideal of popular sovereignty against what populists say are insufficient and improper means of holding rulers to account—grants legitimacy and appeal to the defining mark of populism. In this respect, the core populist claim is vested in an idea “which pits a virtuous and homogeneous people against a set of elites and dangerous “others,” who are together depicted as depriving (or attempting to deprive) the sovereign people of their rights, values, prosperity, identity, and voice” (Albertazzi and McDonnell, 2008: 3).

The political rhetoric based on a culture war framing exploits and politically mobilizes this binary logic. It provides a tangible notion of a homogeneous people whose basic rights and identity are depicted as being compromised by an irresponsible elite. Framing issues based on a fundamental cultural divide allows political actors to dramatize conflicts in terms of an existential threat to ordinary citizens’ well-being. In Central and Eastern European countries, Hesová (2021) depicts culture wars as integral to populism’s political repertoire and its polarizing strategy based on the politics of identity and morality. The culture wars repertoire facilitates the popularization of identity politics as an indispensable part of the anti-elitist ideology of populism (see: Noury and Roland, 2020).

The common reference point is the sovereigntist claim to defend the integrity and viability of the political community against imminent internal and external threats. Populism’s political appeal critically rests on the dramatized invocation of the friend-enemy binary, which draws a clear distinction between friendly insiders and threatening outsiders. In essence, populist politics raises the specter of a permanent state of exception, in which the voice of the people is silenced and the interests or identity of the community are perpetually compromised by corrupt or unresponsive elites.

Conservatism and the challenge of right wing, populist politics

There are two opposing ways for the centre-right to address the rising fortunes of right-wing populism with its culturally charged agenda. The first is to discredit the competition from the right by characterizing them as a xenophobic, anti-democratic force with whom collaboration is unacceptable. In the German context, this strategy is based on the so-called Brandmauer (firewall), the cordon sanitaire that isolates the extreme right and deprives them of any realistic chance to gain access to power as a governing party (Cremer, 2023). The key is the uncompromising demarcation from the radical right, with the CDU almost unanimously depicting the AfD as outside the realm of acceptable politics and as a genuine threat to democracy. Alternatively, the centre-right could offer strategic partnerships with the extreme right in an effort to bolster their electoral fortunes. In Germany, we observe the first glimpses of this approach at the local or regional level in East Germany, where the relative strength of the AfD makes it difficult for the CDU to find a feasible pathway to forming governments at regional and local levels.1

The results of the recent (September 2024) state elections in Germany’s East are a case in point: the extremist Alternative for Germany (AfD) became the strongest party in Thuringia (32.8%) and came in a close second to the centre-right Christian Democrats in Saxony (30.6%) and to the Social Democrats in Brandenburg (23.5%). These election outcomes constitute a watershed moment in German politics. What unfolded in these two former Communist states indicates the widespread acceptability of an extremist right-wing ideology (Germany’s intelligence agencies officially declared the AfD in Thuringia and Saxony as “assured right-wing extremist”) that propagates aggressive anti-immigrant and authoritarian ideas.

With the striking success of the AfD, forming a stable government without the right-wing extremists has become be a formidable task. Recent political developments in Austria illustrate this point, keeping the right-wing, populist party from government has proven to be extremely challenging. If the CDU follows through with its categorical commitment not to collaborate with the AfD and maintains the cordon sanitaire towards the extreme right, the prospects of a stable and effective government are slim. Some commentators have already raised the prospect of a state of “ungovernability” or a political stalemate with no obvious path forward. In the wake of these state elections, the CDU has begun propagating an aggressive anti-immigrant stance, partially incorporating policy ideas from the AfD. As Patton observed already in 2020, “established parties have responded to the AfD with a combination of parliamentary exclusion and the partial inclusion of its themes” (Patton, 2020: 96).

In the British context, the cooptation approach was on display during the Brexit campaign and its subsequent implementation. Yet, as some observers (Bale, 2022) have argued, the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and Reform UK have had a radicalizing effect on the Conservative Party in the wake of the public debate leading up to the referendum on leaving the European Union (Alexandre-Collier, 2018). While the Tories were initially torn about Brexit, with then-Prime Minister Cameron being a vocal supporter of the UK remaining in the EU, they embarked on an aggressive Leave campaign and, in the dominant framing, adopted some of the central political arguments promoted by UKIP. Bale (2018) speaks of a symbiotic relationship between UKIP and the Conservatives, considering the prevalence of Euroscepticism on the centre and far right in the UK. The 2016 referendum created a political environment in which the Conservative Party adopted increasingly nationalist-populist positions and competed with the far-right UKIP for popular support (Hayton, 2022; Lynch and Whitaker, 2018; Webb and Bale, 2014).

The Conservative Party mobilized the fear of migration as a central building block of its Leave campaign. For the master frame of the campaign, “win back control,” a strong and tangible sense of external forces threatening the sovereignty of the UK was instrumental. Migration offered an emotionally charged reference point for depicting the alleged threat from outside and the need to defend the integrity of the country’s borders (Schmidtke, 2021). The large number of refugees seeking shelter in Europe during that period was a major factor leading up to the referendum (2015–2016) and its sovereigntist claim of protecting borders and curtailing immigration. Indeed, the so-called “refugee crisis” allowed the Leave campaign to link anti-immigrant arguments directly with the EU, which was accused of facilitating refugees’ irregular arrival to the British Isles.

Against this background, this article asks whether, based on an empirical study of both mainstream centre-right parties, we can detect a shift towards the populist reliance on “culture wars” as a central component of their political mobilization. In other words, this study probes the degree to which conservative parties in two Western European democracies have adopted some key tropes of the culture wars rhetoric in their political communication. This research question speaks to a critical period in which conservatism in Western democracies redefine their political distinctiveness. With a view to the German Christ-Democratic parties, Biebricher (2024) speaks of an “identity crisis” in form of a loss of stable and attractive ideological profile.

In spite of the veritable challenges that right-wing populism poses to the centre-right, it is worth noting that Germany and the United Kingdom are two cases where conservative parties have enjoyed widespread electoral support and have formed governments for long periods (Chancellor Merkel’s government was in power from 2005–2021, and the Conservatives formed government from 2010 until their 2024 defeat to the Labour Party under various Prime Ministers). Even though the result for the Christian Democratic Union and its Bavarian sister Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CDU/CSU) in the 2025 federal election is low compared to the Merkel years, the conservatives are still the strongest party with 28.6% of the total vote.

Similarly, the British Conservative Party has been able to garner gradually more support over the past 20 years until the 2024 elections reversed this trend in a dramatic fashion. In this respect, there seems to be no immediate pressure to adhere to the populist rhetoric and political resurgence at first sight. The British First-Past-the-Post electoral has traditionally provided a safety net for the Conservative Party when it comes to be being challenged by right-wing nationalists or populists.

Frame analysis: probing the prevalence of culture wars

When probing the prevalence of “culture wars” ideas and frames, this analysis relies on a broad understanding of the concept. Originally, the term “culture war” was coined in reference to Germany in the second half of the 19th century, when Bismarck’s government and his reform agenda were pitched against the Catholic Church (Kraus, 2016). Essentially, the concept relates to a conflict framed in terms of competing ideas regarding the cultural-religious foundations of the modern state (Clark and Kaiser, 2003). In its more contemporary iteration, the concept of “culture wars” was popularized again by Hunter (1991), who used it to describe the “struggle to define America,” in which, according to his interpretation, “orthodox” forces were pitched against “progressive” ones.

For the purpose of this article, I rely on the notion of “culture wars” as a systematic attempt to employ culturally framed (group) identities in political mobilization, depicting fundamental choices about the future political fate of a society (for instance, related to religion, the nation, family models, gender roles, or sexual preferences). Using political rhetoric framed within the rationale of “culture wars” seeks to create strong dichotomies between these cultures or collective identities, presenting them as the essential lens through which to perceive key political and policy decisions (Kądzielska, 2023). In particular, in Europe, the religious component is only one of the determinants of the concept – and not necessarily the decisive one.

This empirical study undertakes a qualitative discourse analysis of political communication strategies employed by the UK Conservative Party and the German Christian Democratic Union (CDU) during national electoral campaigns from 2005 to 2024. The primary aim is to examine the extent and manner in which “culture wars” narratives have been integrated into their political messaging.

The textual corpus for the discourse analysis was compiled through targeted sampling (focused on four core thematic issues) and consists of a diverse range of materials representative of the parties’ official communication strategies across multiple election cycles. This material includes party programs and manifestos, electoral pamphlets and brochures distributed during campaigns, key speeches by party leaders and prominent candidates (particularly campaign launches, convention addresses, and major public speeches), press releases and newspaper op-eds authored by senior party figures, as well as social media content in the form of prominent Twitter and Facebook campaign posts and advertisements.2 The collection prioritized documents that were publicly disseminated and played a significant role in shaping the parties’ electoral narratives.

The analysis employed a hybrid coding strategy, integrating both deductive and inductive approaches. Deductively, the coding was informed by the literature on “culture wars” and focused on identifying rhetorical patterns and discursive features typically associated with this mode of communication—such as polarization, emotive language, and symbolic politics—especially in relation to issues of identity and values. Inductively, the material was interpreted through close reading, allowing themes and narrative structures to emerge organically from the text. This approach enabled attentiveness to context-specific framings and discursive nuances. Each document was coded using qualitative data analysis software to ensure consistency in categorization.3

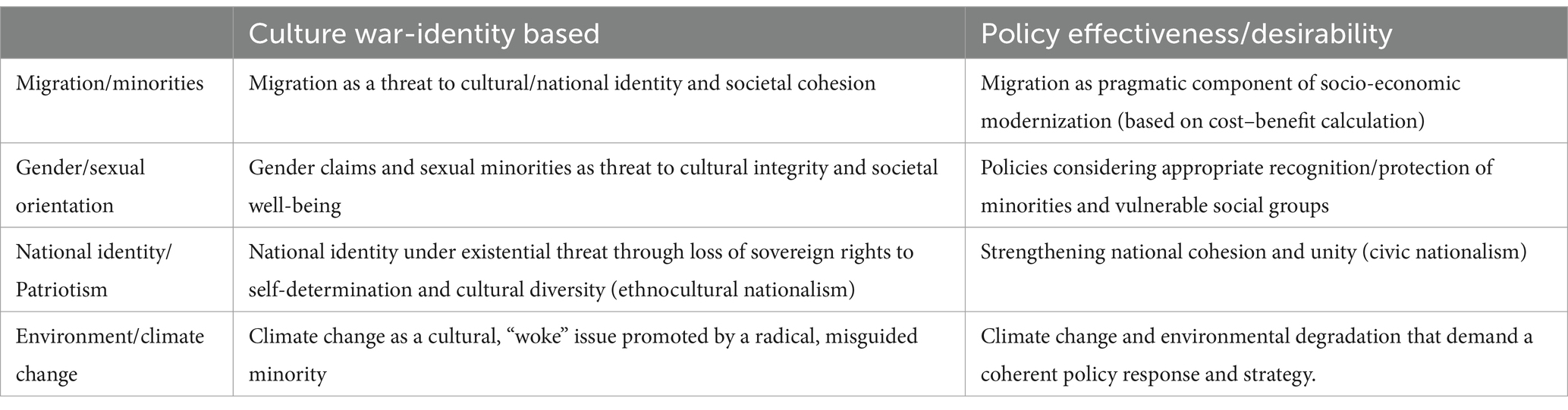

Four broad thematic domains—migration, gender and sexual identity, national identity, and the environment—were selected for focused analysis due to their frequent invocation in culture wars discourse and their salience in party communications. The analysis proceeded in two stages: In the first, a quantitative-descriptive phase, the relative frequency of these themes across time and between parties was documented to map their evolving prominence. In the second, an interpretive-analytical phase, each instance was further classified along a binary dimension: whether the theme was primarily framed as a matter of policy preference or as part of a culture wars narrative. This distinction was operationalized through contrasting indicators: policy framing was characterized by technical, pragmatic, or interest-based language, including references to institutional processes, empirical evidence, or policy efficacy; culture wars framing was marked by identity-based rhetoric, symbolic appeals, tradition or national values, dichotomous “us vs. them” narratives, and moralized depictions of threat or decay.

Throughout the analysis, the culture wars lens was applied critically, with caution against overgeneralizing or reifying campaign strategies that may serve varied communicative purposes. While the study does not claim statistical generalizability, it offers a rich interpretive account of how culture wars themes have appeared and evolved in the discourse of mainstream centre-right parties in the UK and Germany over the past two decades.

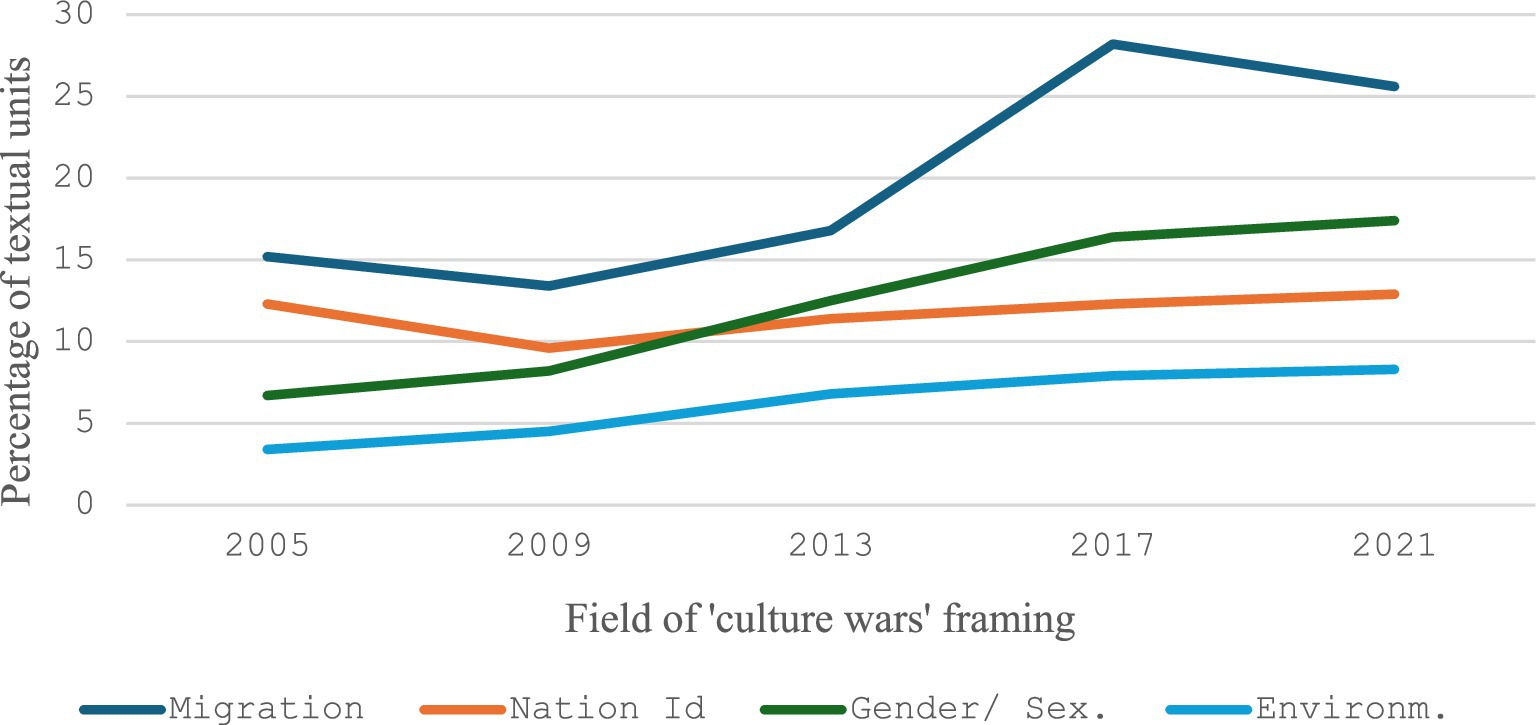

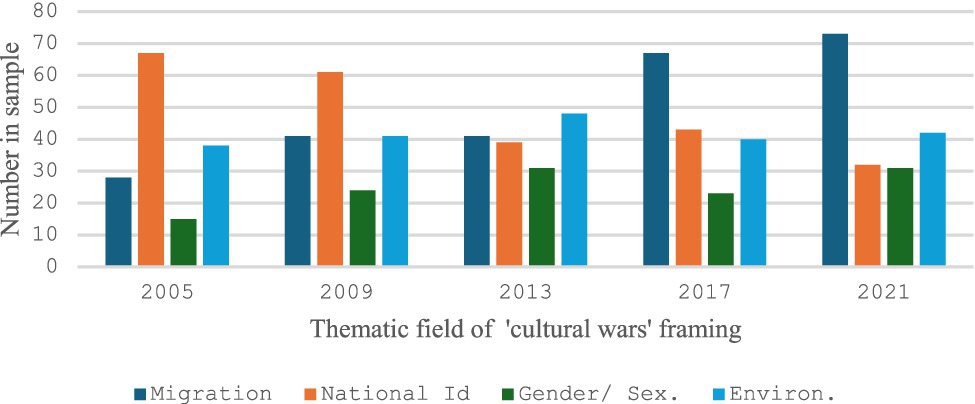

Regarding the overall prominence of the four thematic fields in party political communication over the past two decades, it is evident that these issues have played an increasingly central role in shaping electoral campaigns. In the case of the German Christian Democrats, migration and environmental issues have emerged as dominant themes, whereas national identity and gender/sexual orientation have seen only a moderate increase in visibility. Figures 1, 2 illustrate the extent to which these four themes are represented—measured by their frequency—in the data sample. For simplicity I coded each document only for its predominant framing.

Figure 1. Frequency of themes in CDU’s political communication (number of documents in sample; 2005–2021).

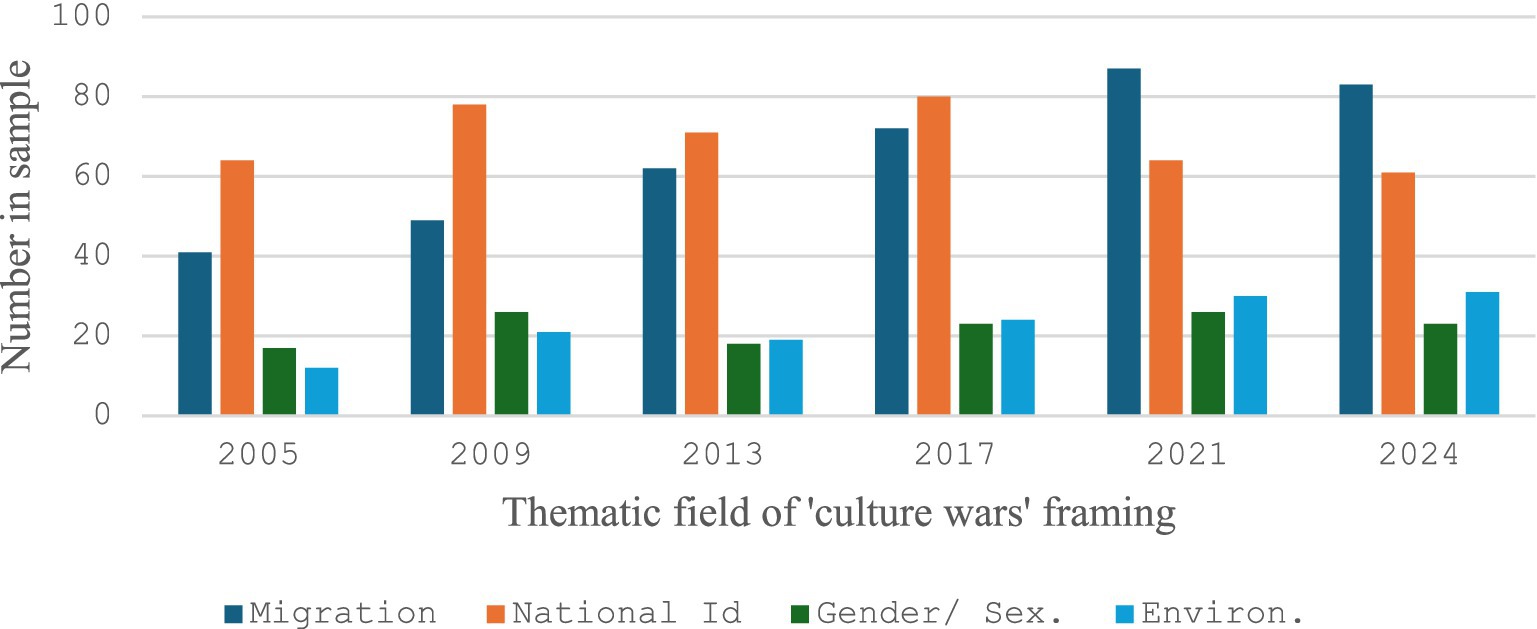

Figure 2. Frequency of themes in Conservative Party’s political communication (number of documents in sample, 2005–2024).

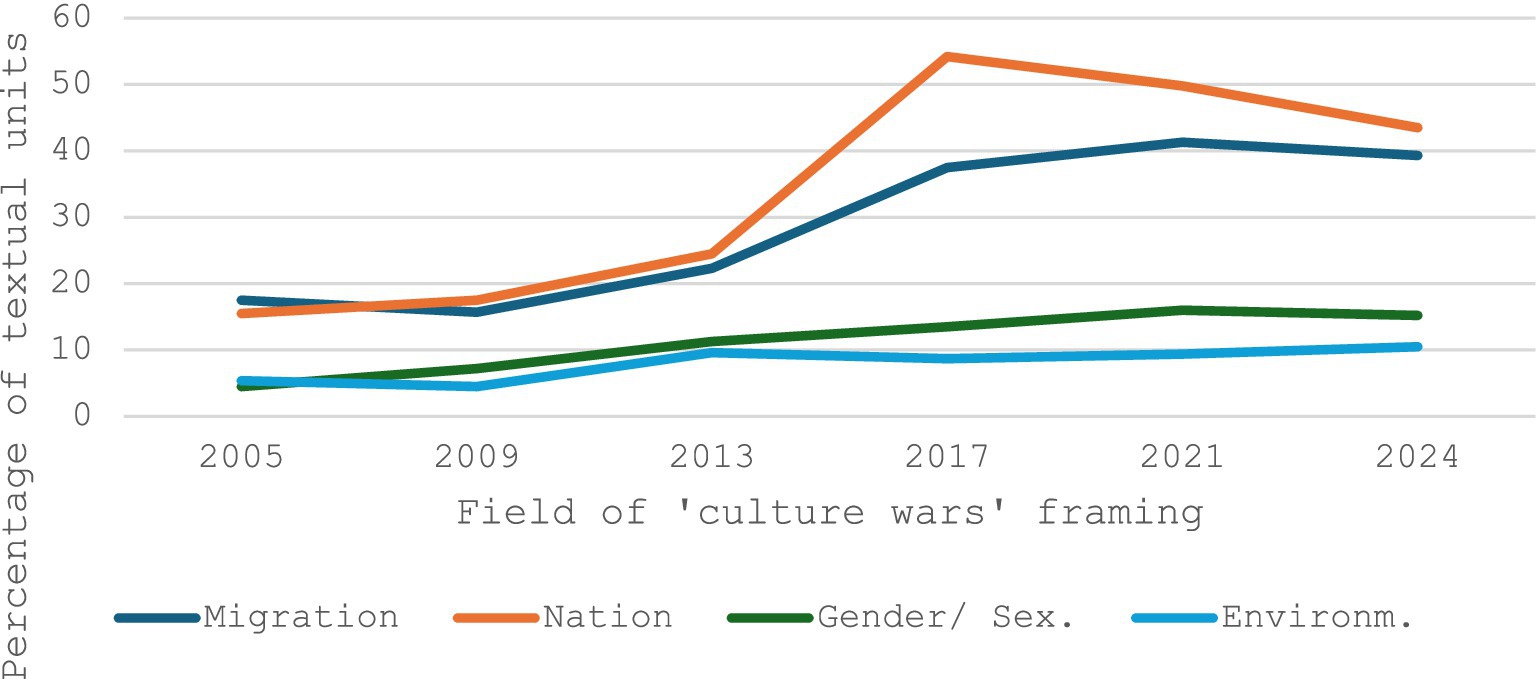

In contrast, the British Conservatives have put much more weight on issues of national identity (as compared to the European one) and migration as they were importantly debated during the Brexit campaign. References to gender, abortion and sexual identities or the environment play a less prominent role in their electoral campaigns (see Figures 3, 4).

Figure 4. The Conservative Party’s use of “culture wars” framing in four thematic fields (2005–24; in %).

The analysis proceeds with coding the compiled textual units according to two contrasting frames: One guided by the idea of “cultural wars” with its irreconcilable, identity-driven conflicts between distinct social groups and the other driven by interest-based, competing policies and their respective advantages or effectiveness.4 Table 1 provides an overview of the competing narratives based on which issues in the four thematic fields are perceived and politically addressed.

Table 1. Competing framing of key political issues: policy effectiveness versus culture and identity.

Migration

In Western democracies, migration and cultural diversity have been the most divisive and politically influential issues in electoral politics (Hadj Abdou et al., 2022). In their political campaigns, the centre-right has needed to balance the resurgence of staunchly anti-immigrant forces on the right (UKIP/ Reform and AfD, respectively) on the one hand, and the increasing demand of Western societies for the influx of skilled labour from abroad on the other hand. Like other European countries, Germany and the United Kingdom have witnessed what has at times been an aggressive rejection of immigrants and cultural diversity. Hollifield et al. (2008; similarly: Boswell and Hough, 2008; Hampshire, 2023) described this tension theoretically in terms of a fundamental “liberal paradox” plaguing the migration state: governments’ attempts to employ immigration as a tool for various socio-economic and political policy goals (most prominently, to address the implications of ageing Western societies) are mirrored by a momentous identity-driven political pushback against expansive immigration policies in liberal democracies.

While even conservative parties have gradually warmed up to the idea of introducing immigration and integration policies, Germany has seen a highly controversial politicization of migration-related issues, particularly after the large influx of refugees in 2015/16 (Atzpodien, 2022; Hertner, 2022). Several studies have highlighted how the rise of the right-wing Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany; AfD; Art, 2018; Arzheimer and Berning, 2019; Decker, 2016; Dilling, 2018), with its aggressive anti-immigrant agenda, has challenged the “modernization” of the CDU’s approach to migration. As a result, the German Christian Democrats have employed deliberate ambiguity in approaching the thorny issue of migration (Clemens, 2018).

The material that both conservative parties used in their electoral campaigns was coded accordingly: Migration can be depicted through the lens of the country’s socio-economic interests, weighing its costs and benefits when considering policy options. In contrast, an identity-grounded framing that employs the reasoning of a “culture wars” narrative focuses on the alleged incompatibility of cultures and the principled undesirability of non-nationals in the name of protecting the integrity (and identity) of the community. Yet, a cautionary note is warranted here: often these two frames overlap. For instance, if one considers how issues of migration and borders were framed in the Leave campaign, migration has regularly been described as a drain on public resources, particularly with respect to the British healthcare system, the National Health Service (NHS). Yet, this interest-based frame operates with notable ambiguity: while migrants and the costs associated with them are depicted as a liability for the country’s resources, properly managed migration is referred to as a legitimate tool for sustaining the competitiveness of the British economy. Borders are routinely described as tools for defending the UK’s economic interests, allowing for a properly managed migration regime. Still, interpreting the textual material, it becomes quickly apparent if an argument is framed following the “culture wars” logic or one shaped by interest-based consideration of more desirable and effective policies in the field.

Sexual orientation: gender identities, pronouns, and reproductive rights

The issue of gender identity and reproductive rights is at the heart of the “culture wars” agenda (Lewis, 2017). For instance, gender pronouns or gender fluidity have become key reference points in discrediting the so-called “woke” liberal elite. The “culture wars” framing is apparent in those narratives that address the rights of women or sexual minorities in terms of a social identity that is – illegitimately – imposed on the rest of society. In an affective format, these identities are depicted as “unnatural,” decadent, or even depraved (Sauer, 2020). In this narrative, a conservative image of masculinity is contrasted with a feminist and LGBTQ perspective that is portrayed as socially unacceptable (Agius et al., 2020; Naunov, 2024). In this context, gender issues are regularly framed based on religious perspectives in radical-wing populist discourses (Evolvi, 2023; Edenborg 2023; Norocel and Giorgi, 2022). The contrasting frame is grounded in a debate on the appropriate approach to protecting minorities and considering women’s rights in various arenas of societal life.

Environmental issues and climate change

The environment and the challenge of climate change would normally not figure prominently in a list of themes that are subject to the politicizing logic of the “culture wars” narrative. Yet, as the issue has become more central in political and electoral debates, there has been an increasingly aggressive attempt on the populist right to discredit the environmental agenda as “woke” and driven by cultural elites allegedly sacrificing the economic well-being of the nation because of misguided measures to fight climate change and environmental degradation. Electric cars, wind energy, and heat pumps have all been subject to aggressive efforts to discredit them based on cultural grounds. In this field, the defining mark of a “culture wars” framing is easily discernible: The argument about effective measures designed to protect the environment is opposed by those who question environmental measures on principled grounds, suggesting that an irresponsive cultural elite forces this agenda on the public without proper evidence (Foster, 2021).

National identity/European integration

This thematic field addresses the issue of national identity as a central issue of concern for politicians and policymakers. The nationalist agenda operates based on a relatively clearly prescribed bordered community, the demos, defined by territory and historically rooted identity markers. In contrast, the populist notion of the “people” and the political community whose interests, if not very existence, is painted as being under existential threat, varies in accordance with the nature of the community’s foes. Based on a “culture wars” perspective, the nation is perceived to be losing its core identity, which in turn is primarily framed based on an ethno-cultural understanding.

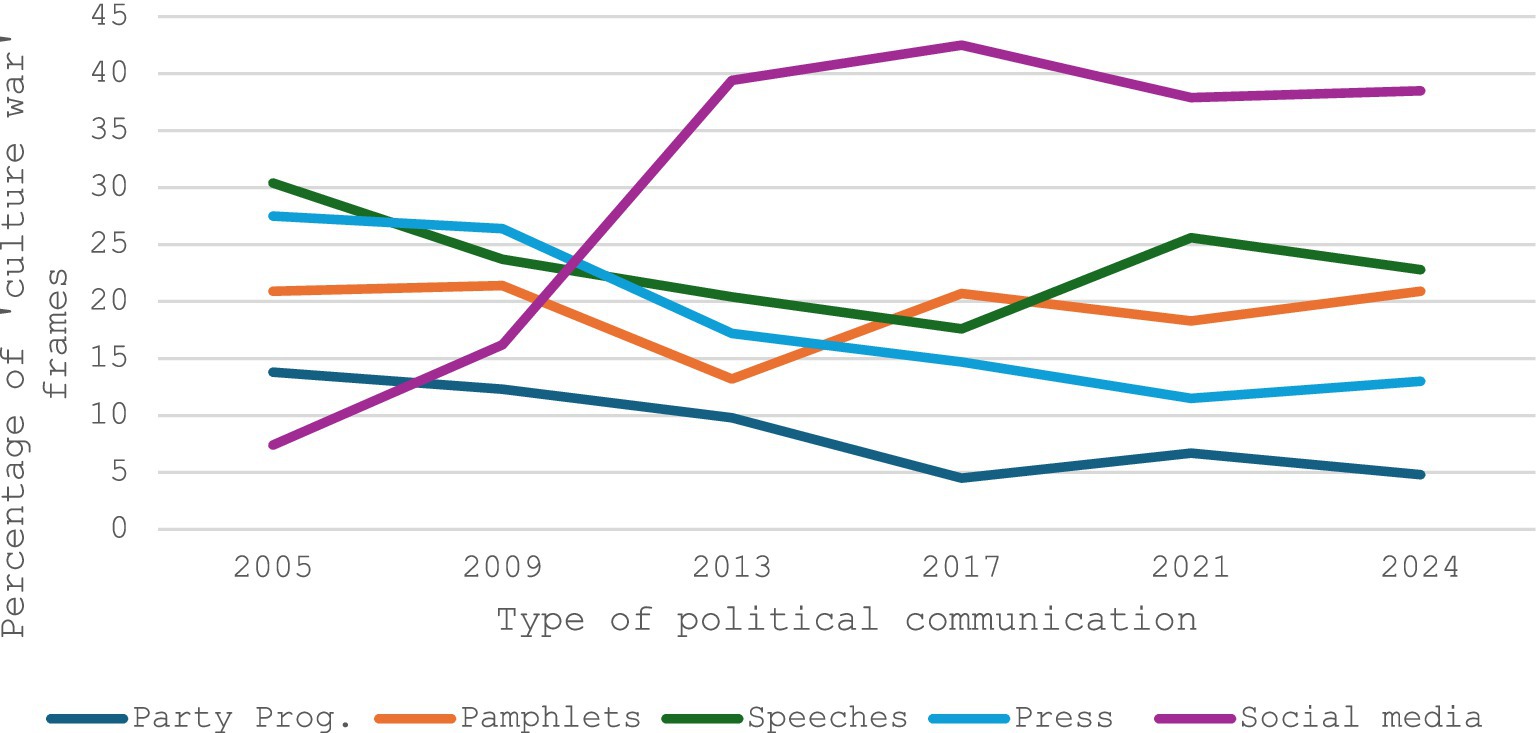

The following two graphs summarize the extent to which the Conservative Party and the CDU have relied on frames rooted in the “culture wars” narrative:

The empirical analysis of both conservative parties is based on an aggregate dataset encompassing various formats of political communication across both cases. However, it is worth considering how the prominence of “culture wars” frames varies with the medium through which messages are delivered. Figure 5 (based on the combined data) illustrates that social-media communication has emerged as the most significant channel for disseminating “culture wars” narratives. These findings underscore the pivotal role social media platforms have played in framing political issues—beyond the fact that they have only become primary arenas for political mobilization over the past fifteen years. Similarly, Bonnet and Kilty (2024) highlight how social media have transformed the environment for political communication, opening new opportunities for the spread of “culture wars” narratives.

Analysis: the gradual erosion of traditional conservative politics

The comparison between the two established centre-right parties demonstrates some similarities and notable differences: Both organizations have significantly embraced a political campaign that frames key issues through a “culture wars” or cultural identity lens. The thematic field in which we can detect this trend is primarily migration and ethno-cultural minorities. Over the past two decades, the Conservative Party and the CDU have increasingly leaned on the divisive power of culture as a medium to generate loyalty, discredit opponents, and promote political agendas in a populist manner. In both electoral arenas, the issue of migration has seen a significant increase in prominence, providing an insider-outsider narrative that gives urgency to culturally framed grievances and societal divides.

In this regard, the interpretation of how these issues have been framed substantiates the initial hypothesis about a growing openness to the populist politicization of issues along culturalist lines. For well-established centre-right parties, such as the Conservative Party or the CDU, such an anti-elitist claim seems to be contradictory at first sight. They have been in office for much of the period under investigation, and they have been pillars of the respective nation’s party politics for decades. Yet, in a climate where anti-establishment sentiments have become a defining feature of politics in many Western democracies, and in which traditional parties are regularly seen as unable to provide satisfactory answers to the fundamental challenges and crises of our times, the “culture wars” rhetoric is an attractive tool in electoral politics. The emotionally charged friend-enemy distinction provides a mobilizing platform that is largely devoid of concrete policy prescriptions but fertile when it comes to straightforward, albeit oversimplified, cultural binaries for political campaigns.

While there is a similar trajectory in terms of increasing reliance on “culture wars” frames, there are also pronounced differences between the two parties. At the most basic level, it is worth pointing out that the British Conservatives operate at a higher level, specifically with respect to politicizing issues of migration and national identity along a culturalist, populist interpretation. In particular, over the past two election cycles, the British Conservative Party has embarked on a sustained campaign portraying migrants as a genuine threat to the integrity and interests of the political community. For instance, the Conservative Party mobilized the fear of migration as a central building block of its Leave campaign in the wake of the Brexit referendum. For the master frame of the campaign, “take back control,” a strong and tangible sense of external forces threatening the sovereignty of the United Kingdom was instrumental. Leading up to and following the Brexit debate, the “culture wars” framing has become the dominant interpretative lens through which the issue is addressed and pitched in electoral competitions. At times, over 50% of the textual material used in the 2017 and 2021 electoral campaigns corresponded to the interpretative logic of the “culture wars” narrative. Compared to migration and national identity, the other two themes—gender/sexual diversity and the environment—have not become subject to the same populist, divisive framing for the Conservatives. For them, migration, diversity, and national identity are the primary issues that are employed in political mobilization based on the divisive and emotive basis of “culture wars”.

Migration has offered an emotionally charged reference point for depicting the alleged threat from outside and the need to defend the integrity of the country’s borders. The large numbers of refugees seeking shelter in Europe during the period leading up to the referendum (2015/16) were a critical element in adding urgency to this agenda. Indeed, the so-called “refugee crisis” allowed the Leave campaign to link the anti-immigrant arguments directly with the EU, which was accused of facilitating refugees’ irregular migration to the British Isles [see for a similar argument: Dennison and Geddes (2018) and Foster and Feldman (2021)].

In comparison, the German Christian Democrats have distanced themselves more strongly from this type of framing. Still, there has been an uptake, specifically regarding the issue of migrants, in the wake of the 2015/16 “refugee crisis.” It is also worth noting that, in the case of the CDU, there is far greater emphasis on the controversial issue of gender and sexual orientation. Particularly, the issue of gendered language has been politicized as a deep cultural divide and a clear sense of tension between the so-called “majority” and a “minority” that is portrayed as undermining the cultural identity and well-being of society at large. In contrast, the CDU has largely abstained from an (ethno-) culturalist framing of Germany’s national identity (see: Schmidtke, 2017) and the culturalist depiction of environmental issues.

Overall, the CDU demonstrates a more solid grounding in promoting policy alternatives in these fields rather than framing them in terms of an essential cultural divide between irreconcilable social groups. Or, to phrase it differently: While the German Christian Democrats have flirted with the “culture wars” vocabulary and framing (particularly when it comes to migration), their political mobilization over the past 20 years displays far more continuity as a policy-centred, interest-driven party of the old type than their British counterparts. This finding can also be related to Chancellor Merkel’s long-lasting attempt to “modernize” the Christian Democratic Party and to “normalize” migration and the integration of newcomers into German society from a pragmatic standpoint (Bogado and Wolf, 2024; Hertner, 2022; Schmidtke, 2024).

One noteworthy finding emerging from the comparative perspective is that the deepening reliance on political rhetoric couched in the divisive logic of the “culture wars” is not a simple result of the populist challenge to the centre-right. Arguably, over the past ten years, the German Christian Democrats have faced a more serious competitor in the Alternative for Germany, which, with the “refugee crisis” in the mid-2010s, positioned itself as a serious competitor for votes on the political right. In contrast, the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom has not faced an electoral challenge from the extreme right to the same degree. Still, one could argue that the Brexit campaign, leading up to the referendum in 2016, shifted the political climate to the right and thus emboldened actors with a more nationalist-populist agenda. While the First-Past-the-Post system might have prevented parties such as UKIP/Reform UK from emerging as serious contenders in competitive party politics (although the 2024 elections provided indications that this logic might come to an end), the political identity of the Conservative Party is clearly in flux and increasingly aligned with a nationalist-populist orientation (see also: Casiraghi, 2021). This finding confirms what Alexandre-Collier (2022) framed as the “populist hypothesis” in the British Conservative Party.

Factor in driving divergent pathways in “culture wars” adoption

Considering the empirical findings of this study, it is worth exploring why the Conservative Party and the CDU, despite similar pressures from rising identity politics, have charted divergent paths in the adoption of culture wars rhetoric. While both parties are undergoing transformation, their different political environments and internal dynamics shape how far and how fast they are willing to depart from traditional policy-centered conservatism in favor of cultural polarization. In this section, I will briefly consider structural and strategic factors that shape the parties’ incentives and constraints when it comes to employing “culture wars” framing.

Significantly, the UK’s First-Past-the-Post electoral system promotes majoritarian competition, incentivizing political actors to adopt emotionally resonant, polarizing rhetoric that mobilizes large electoral blocs. The Conservative Party’s embrace of ‘culture wars’ narratives—particularly around migration and sovereignty—fits within this logic. The “Leave” campaign, with its potent slogan “Take Back Control,” strategically capitalized on this dynamic (Vachudova, 2021). In contrast, Germany’s mixed-member proportional representation system fosters coalition politics and encourages moderation. For the CDU, overt polarization could undermine potential coalitions and alienate centrist voters. As such, the party has exercised more caution in deploying divisive cultural frames, often favoring technocratic and policy-based approaches, especially under Merkel’s leadership.

The electoral system also sets the institutional framework for party system dynamics. In Germany, there has been a well-developed awareness among conservatives that a wholesale embrace of “culture wars” rhetoric by the CDU risks legitimizing AfD narratives focused on the issue of migration and national identity, inadvertently pushing the political discourse further to the right. In its strategic considerations, the CDU has faced the delicate to task not to alienate its centrist voters with a more extremist rhetoric that would embolden the extreme right, while needing to address the growing skepticism towards migration and fear of violence. In contrast, the UK Conservative Party encountered less obstacles in its quest to absorb and internalize populist demands that once squarely belonged to the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and later Reform UK. The Conservatives effectively co-opted these themes, particularly in the Brexit context, without suffering significant fragmentation on their right flank—at least until the 2024 election showed signs of renewed right-wing competition. This enabled the party to embed populist cultural narratives into its mainstream political identity more forcefully.

A dimension that is only indirectly reflected in the data analyzed here are the core events that have provided opportunities for reimagining political rhetoric and priorities. Most prominently, the 2015–2016 refugee crisis and the Brexit referendum offered such exceptional and transformative framing opportunities. In the UK, migration was easily linked to the question of EU membership, creating a highly salient and emotionally resonant narrative of external threat and lost sovereignty. The highly divisive Brexit debate led the Conservative Party to anchor its political identity more strongly around a populist cultural frame. In Germany, Merkel’s decision to open the borders led to political backlash but was followed by a concerted effort to reframe migration as a manageable policy challenge (Mushaben, 2017). While the CDU did increase its cultural rhetoric in response to AfD pressure, the party avoided turning migration into a foundational “culture wars” issue in the same way the Conservatives did.

There is also a broader cultural context that constrains the CDU’s willingness to fully embrace the populist rhetoric often associated with “culture wars” narratives. In Germany, the legacy of the Nazi regime and the post-war commitment to liberal democratic norms impose significant discursive boundaries on how national identity and migration can be framed in public debate (Habermas, 2018; Rensmann, 2018). Although the CDU has at times flirted with anti-immigrant discourse during electoral campaigns, it has generally refrained from adopting openly ethno-nationalist or overtly populist messaging. These cultural and historical constraints on the acceptability of “culture wars” rhetoric became particularly evident during the 2025 electoral campaign, when CDU leader Friedrich Merz sparked widespread controversy by accepting support from the far-right Alternative for Germany to pass a non-binding migration motion in the Bundestag. The move was perceived by many as a breach of the long-standing “firewall” policy that mainstream German parties have upheld to prevent cooperation with extremist parties such as the AfD, known for its nationalist and xenophobic rhetoric. In response, hundreds of thousands took to the streets in protest, with many demonstrators carrying banners reading “Never Again”—a clear reference to Germany’s historical reckoning with its authoritarian past.

In contrast, British political culture has long featured appeals to sovereignty, tradition, and national pride. These themes were revitalized during the Brexit debate and have remained central to Conservative electoral messaging. The relative absence of historical taboos around nationalist rhetoric in the UK has allowed the Conservative Party to engage more fully in culture wars politics without provoking widespread backlash.

Lastly, leadership plays a critical role in shaping rhetorical strategies. Angela Merkel’s tenure as CDU leader and German Chancellor was marked by centrist pragmatism and depolarization. Her approach to migration, for instance, emphasized integration and policy solutions, helping to contain the rise of a more extremist discourse within her party in particular in the wake of the 2015/16 “refugee crisis”. Even under Friedrich Merz, who is poised to be more right-leaning than Merkel, the CDU has shown a more cautious engagement with “culture wars” issues, particularly when compared to its British counterpart. By contrast, Boris Johnson’s leadership was overtly populist and performative. His embrace of emotionally charged rhetoric and nationalist symbolism helped normalize the use of cultural grievance as a central component of political strategy. Current Conservative leadership under Kemi Badenoch appears open to continuing this trajectory, especially on issues like gender identity and political correctness.

Conclusion: the transformation of the centre-right in Germany and the United Kingdom

The comparative analysis of the political discourse used by centre-right parties in Germany (CDU) and the United Kingdom (Conservative Party) reveals a significant shift in their political identities over the past two decades. This transformation has been largely driven by the growing prominence of “culture wars” rhetoric, which has brought cultural identity issues—such as migration, national sovereignty, and gender politics—to the forefront of electoral competition. These issues, traditionally seen as secondary to economic and policy debates, are now central to the political strategies of both parties.

Both the CDU and the Conservative Party have increasingly adopted the language of identity politics, a trend shaped by the rise of right-wing populism and the pressure to remain electorally competitive. While the two parties have responded differently to this challenge, they share a tendency to engage in identity-based political mobilization. The results of this study provide evidence that the traditional cleavage structure defining electoral politics is undergoing a radical transformation (Ford and Jennings, 2020).

The growing reliance on identity politics and “culture wars” rhetoric presents both opportunities and risks for the centre-right. On one hand, these issues provide a powerful tool for mobilizing voters, especially in a political climate where economic debates have lost some of their salience. Cultural identity issues tap into deep-seated emotions and anxieties, allowing parties to present themselves as defenders of the “people” against external threats, whether real or perceived.

On the other hand, the embrace of identity politics risks alienating moderate voters and undermining the traditional policy-driven appeal of centre-right parties. As the empirical analysis shows, the more the CDU and the Conservative Party lean into “culture wars”, the more they risk becoming indistinguishable from their right-wing populist competitors. This could lead to a fragmentation of the centre-right, with some voters gravitating towards more extreme parties like the AfD or UKIP/Reform UK, while others seek more moderate alternatives.

Moreover, the turn towards identity politics could exacerbate social divisions and contribute to the erosion of democratic norms. The “culture wars” narrative is inherently polarizing, framing political debates as existential battles between opposing camps. This binary approach leaves little room for compromise or consensus-building, both of which are essential for stable governance. If the centre-right continues down this path, it risks deepening societal fractures and undermining the democratic principles it has historically championed.

The findings of this report suggest that the centre-right in Europe is at a crossroads. The CDU and the Conservative Party represent two of the most stable and successful conservative parties in Western Europe, yet both are grappling with how to respond to the rise of right-wing populism and the growing influence of identity politics. While their approaches differ, both parties face similar challenges: how to remain electorally competitive without fully succumbing to the populist temptation of the “culture wars” narrative and mode of political mobilization.

The CDU’s more cautious approach, rooted in policy pragmatism, a recognition of Germany’s anti-fascist memory culture, and a commitment to moderate conservatism, offers a potential model for how centre-right parties can navigate these challenges. By focusing on practical solutions to pressing issues like migration and integration, the CDU has avoided the more divisive aspects of identity politics while still addressing voter concerns. However, this strategy requires strong leadership and a willingness to resist the populist impulses that have become so prevalent in contemporary politics.

The British Conservative Party, on the other hand, has embraced a more populist approach, which has yielded short-term electoral gains but could lead to long-term fragmentation. The party’s reliance on nationalist rhetoric and its alignment with Brexit-driven identity politics have reshaped its political brand, making it more susceptible to the same forces that have destabilized other European centre-right parties.

Based on the limited evidence produced by this empirical study, it may be an exaggeration to speak of the gradual “Trumpicization” of centre-right politics in Europe. To make such a sweeping claim, a more comprehensive understanding of the electoral campaigns and political mobilization of centre-right parties across the continent would be necessary. Nevertheless, the study of the CDU and the Conservative Party—two relatively stable and successful mainstream right-wing parties—suggests a notable shift in their political identity, away from interest-based policy agendas and toward culturally framed political cleavages. A more in-depth evaluation of both parties’ political communication would shed light on the growing prominence of cultural divides, which pit ostensibly radical minorities or “leftist” ideas against what is portrayed as the common-sense majority of the population. In this regard, the shift in the political communication of conservative parties—and their increasing reliance on a “culture wars” narrative—can be interpreted as both a reflection and a significant driver of the “cultural backlash” (Norris and Inglehart, 2019) unfolding in Western democracies.

One key feature of this growing reliance on culturally charged conflicts or “culture wars” is the invocation of a unified “people” whose interests and identity are portrayed as being under threat by those on the left. It is worth noting that framing the virtuous people against those promoting “radical” ideas is highly emotive and directed at the very identity of the (national) community. Similarly, there has been a clear shift away from the traditional left–right divide—primarily organized around redistributive conflicts—toward one in which the defense of cultural identities takes on a more pronounced role. The parties’ current leaders—Kemi Badenoch for the British Conservative Party and Friedrich Merz for the German CDU – seem at least open to exploring the use of populist “culture wars” rhetoric more fully.

In conclusion, the centre-right in Europe is faced with the delicate task how to balance the demands of an increasingly polarized electorate with the need to preserve the policy-driven, moderate conservatism that has historically defined these parties. The growing reliance on “culture wars” rhetoric promises to be a potent strategic choice for redefining the centre-right in a rapidly changing political landscape. Whether these parties can navigate this transformation without losing their core political identity remains to be seen.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

OS: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. I would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Council of Canada (SSHRC) that has made the research for this article possible.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In a recent study, Schroeder et al. (2025) demonstrate that there has been a gradual expansion of collaborative modes between centrist parties (including the CDU) and the AfD at the local (Kreisebene) level. They argue that, although the firewall has not yet crumbled, there are clear signs of increasing openness to cooperating with the AfD—primarily driven by pragmatic concerns over effective policy-making.

2. ^In total, the following number of textual units was collected and coded from the respective electoral campaigns: Conservative Party (2005: 135, 2009: 173, 2013: 168, 2017: 201, 2021: 215, 2024: 198. For the CDU, 2005: 148, 2009: 167, 2013: 159, 2017: 173, 2021: 178). The breakdown according to the types of political communication is as follows. For the Conservative Party: 67 party programs and manifestos, 150 electoral brochures, 282 speeches, 219 press, 372 social media. For the CDU: 46 party programs and manifestos, 87 electoral brochures, 241 speeches, 185 press, 266 social media. One document could contain several textual units with distinct framing strategies.

3. ^Throughout the process, intersubjective verification was employed to enhance reliability. At least two coders reviewed and discussed the coding decisions, resolving disagreements through deliberation and thereby validating the thematic categories and interpretations.

4. ^Initially, the interpretation of the textual units according to the competing master narratives proved challenging. Yet, with gradually refining the analysis of the framing, it proved increasingly apparent how a textual unit could be coded according to the binary logic described in Table 1.

References

Agius, C., Rosamond, A. B., and Kinnvall, C. (2020). Populism, ontological insecurity and gendered nationalism: masculinity, climate denial and Covid-19. Polit. Relig. Ideol. 21, 432–450. doi: 10.1080/21567689.2020.1851871

Albertazzi, D., and McDonnell, D. (2008). “Conclusion: populism and twenty-first century Western European democracy” in Twenty-first century populism. eds. D. Albertazzi and D. McDonnel (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan), 217–223.

Alexandre-Collier, A. (2018). “From soft to hard Brexit: UKIP’s not so invisible influence on the Eurosceptic radicalisation of the conservative party since 2015” in Trumping the mainstream, Eds. L.E. Herman and J. Muldoon. (London: Routledge) 204–221.

Alexandre-Collier, A. (2022). David Cameron, Boris Johnson and the ‘populist hypothesis’ in the British conservative party. Comp. Eur. Polit. 20, 527–543. doi: 10.1057/s41295-022-00294-5

Art, D. (2018). The AfD and the end of containment in Germany? German Polit. Soc. 36, 76–86. doi: 10.3167/gps.2018.360205

Arzheimer, K., and Berning, C. C. (2019). How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and their voters veered to the radical right, Electoral Studies, 60:2013–2017. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

Atzpodien, D. S. (2022). Party competition in migration debates: the influence of the AfD on party positions in German state parliaments. German Polit. 31, 381–398. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2020.1860211

Bale, T. (2018). Who leads and who follows? The symbiotic relationship between UKIP and the conservatives–and populism and Euroscepticism. Politics 38, 263–277. doi: 10.1177/0263395718754718

Bale, T. (2022). Policy, office, votes–and integrity. The British conservative party, Brexit, and immigration. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 48, 482–501. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853909

Bértoa, F. C., and Enyedi, Z. (2021). Party system closure: Party alliances, government alternatives, and democracy in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Biebricher, T. (2024). The crisis of American conservatism in historical–comparative perspective. Politische Vierteljahresschrift 65, 233–259. doi: 10.1007/s11615-023-00501-2

Blühdorn, I., and Butzlaff, F. (2019). Rethinking populism: peak democracy, liquid identity and the performance of sovereignty. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 22, 191–211. doi: 10.1177/1368431017754057

Bonnet, A. P., and Kilty, R. (Eds.) (2024). Towards a very British version of the “culture wars”: Populism, social fractures and political communication. London: Routledge.

Boswell, C., and Hough, D. (2008). “Politicizing migration: opportunity or liability for the Centre-right in Germany?” in Immigration and integration policy in Europe (Routledge), 17–34.

Bogado, N., and Wolf, T. (2024). The CDU and the Leitkultur Debate: An Analysis of Angela Merkel’s Integration Discourse Before and After the 2015 Syrian Refugee Crisis. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 25, 2123–2141. doi: 10.1007/s12134-024-01159-4

Breeze, R. (2019). Positioning “the people” and its enemies: populism and nationalism in AfD and UKIP. Javnost-Public 26, 89–104. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2018.1531339

Casiraghi, M. C. (2021). ‘You’re a populist! No, you are a populist!’: The rhetorical analysis of a popular insult in the United Kingdom, 1970–2018. Br. J. Polit. Int. Rel. 23, 555–575. doi: 10.1177/1369148120978646

Chiaramonte, A., Emanuele, V., Maggini, N., and Paparo, A. (2022). Radical-right surge in a deinstitutionalised party system: the 2022 Italian general election. South Europ. Soc. Polit. 27, 329–357. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2022.2160088

Clark, C., and Kaiser, W. (Eds.) (2003). Culture wars: Secular-Catholic conflict in nineteenth-century Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clemens, C. (2018). The CDU/CSU’s ambivalent 2017 campaign. German Polit. Soc. 36, 55–75. doi: 10.3167/gps.2018.360204

Corduwener, P. (2016). The problem of democracy in postwar Europe: Political actors and the formation of the postwar model of democracy in France, West Germany and Italy. London: Routledge.

Cremer, T. (2023). A religious vaccination? How Christian communities react to right-wing populism in Germany, France and the US. Gov. Oppos. 58, 162–182. doi: 10.1017/gov.2021.18

Dilling, M. (2018). Two of the same kind?: the rise of the AfD and its implications for the CDU/CSU. German Polit. Soc. 36, 84–104. doi: 10.3167/gps.2018.360105

Decker, F. (2016). The Alternative for Germany: factors behind its emergence and profile of a new right-wing populist party. German Politics and Society. 34: 1–16. doi: 10.3167/gps.2016.340201

Dennison, J., and Geddes, A. (2018). Brexit and the perils of ‘Europeanised’ migration. Journal of European Public Policy. 25: 1137–1153. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2018.1467953

Donà, A. (2022). The rise of the radical right in Italy: the case of Fratelli d’Italia. J. Mod. Ital. Stud. 27, 775–794. doi: 10.1080/1354571X.2022.2113216

Edenborg, E. (2023). Anti-gender Politics as Discourse Coalitions: Russia’s Domestic and International Promotion of “Traditional Values”. Prob. Post Commun. 70, 175–184. doi: 10.1080/10758216.2021.1987269

Emanuele, V., and Chiaramonte, A. (2020). Going out of the ordinary. The de-institutionalization of the Italian party system in comparative perspective. Contemp. Ital. Politics 12, 4–22. doi: 10.1080/23248823.2020.1711608

Evolvi, G. (2023). Global populism: its roots in media and religion| the world congress of families: anti-gender Christianity and digital far-right populism. Int. J. Commun. 17:18.

Ford, R., and Jennings, W. (2020). The changing cleavage politics of Western Europe. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 23, 295–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-052217-104957

Foster, E. (2021). “Environmentalism and LGBTQIA+ politics and activism” in Diversity and inclusion in environmentalism, Ed. K. Bell, (London: Routledge), 82–97.

Foster, R., and Feldman, M. (2021). From ‘brexhaustion’to ‘covidiots’: the UK United Kingdom and the populist future. J. Contemp. Eur. Res. 17. doi: 10.30950/jcer.v17i2.1231

Gidron, N., and Ziblatt, D. (2019). Centre-right political parties in advanced democracies. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 17–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-090717-092750

Habermas, J. (2018). The new conservatism: Cultural criticism and the historian's debate. Hoboken (NJ) John Wiley & Sons.

Hadj Abdou, L., Bale, T., and Geddes, A. (2022). Centre-right parties and immigration in an era of politicisation. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 48, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853901

Hampshire, J. (2023). The politics of immigration: Contradictions of a Liberal state. Cambridge MA: Policy Press.

Hartman, A. (2019). A war for the soul of America: A history of the culture wars. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hayton, R. (2022). Brexit and party change: the conservatives and labour at Westminster. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 43, 345–358. doi: 10.1177/01925121211003787

Hertner, I. (2022). Germany as ‘a country of integration’? The CDU/CSU’s policies and discourses on immigration during Angela Merkel’s chancellorship. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 48, 461–481. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853908

Hesová, Z. (2021). Three types of culture wars and the populist strategies in Central Europe. Politologický časopis-Czech Journal of Political Science 28, 130–150. doi: 10.5817/PC2021-2-130

Hollifield, J. F., Hunt, V. F., and Tichenor, D. J. (2008). The liberal paradox: Immigrants, markets and rights in the United States. SMU Law Review : 61, 67.

Hunter, J. D. (1996). “Reflections on the culture wars hypothesis” in The American culture wars: Current contests and future prospects, Ed. J. L. Nolan. Charlottesville (VI) University of Virginia Press. 243–256.

Kądzielska, M. (2023). Philosophical foundations of worldview conflict within Western thought in the conservative perspective. Dialogi Polityczne 34. doi: 10.12775/DP.2023.003

Kallis, A. (2018). Populism, sovereigntism, and the unlikely re-emergence of the territorial nation-state. Fudan J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 11, 285–302. doi: 10.1007/s40647-018-0233-z

Kraus, H. C. (2016). Bismarck, die Konservativen und der Kulturkampf im Deutschen Reich. Studia 63, 87–104. doi: 10.5817/SHB2016-2-6

Lewis, A. R. (2017). The rights turn in conservative Christian politics: How abortion transformed the culture wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lynch, P., and Whitaker, R. (2018). All Brexiteers now? Brexit, the Conservatives and party change. British Politics, 13, 31–47. doi: 10.1057/s41293-017-0064-6

Mair, P., Müller, W. C., and Plasser, F. (2004). Political parties and electoral change: Party responses to electoral markets. London: Sage.

March, L. (2017). Left and right populism compared: the British case. Br. J. Polit. Int. Rel. 19, 282–303. doi: 10.1177/1369148117701753

Mushaben, J. M. (2017). Wir schaffen das! Angela Merkel and the European refugee crisis. German Polit. 26, 516–533. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2017.1366988

Naunov, M. (2024). The effect of protesters’ gender on public reactions to protests and protest repression. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev., 119, 1–17. doi: 10.1017/S0003055424000133

Norocel, O. C., and Giorgi, A. (2022). Disentangling radical right populism, gender, and religion: an introduction. Identities 29, 417–428. doi: 10.1080/1070289X.2022.2079307

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit and authoritarian populism. Cambridge MA: Cambridge University Press.

Noury, A., and Roland, G. (2020). Identity politics and populism in Europe. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 23, 421–439. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-033542

Ozzano, L., and Giorgi, A. (2015). European culture wars and the Italian case: Which side are you on? London: Routledge.

Patton, D. F. (2020). Party-political responses to the alternative for Germany in comparative perspective. German Polit. Soc. 38, 77–104. doi: 10.3167/gps.2020.380105

Rensmann, L. (2018). Radical right-wing populists in parliament: examining the alternative for Germany in European context. Germ. Polit. Soc. 36, 41–73. doi: 10.3167/gps.2018.360303

Sauer, B. (2020). “Authoritarian right-wing populism as masculinist identity politics. The role of affects” in Right-wing populism and gender: European perspectives and beyond, Eds. G. Dietze and J. Roth. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. 23–40.

Schmidtke, O. (2015). Between populist rhetoric and pragmatic policymaking: the normalization of migration as an electoral issue in German politics. Acta Politica 50, 379–398. doi: 10.1057/ap.2014.32

Schmidtke, O. (2017). Reinventing the nation: Germany’s post-unification drive towards becoming a ‘country of immigration’. German Polit. 4, 498–515. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2017.1365137

Schmidtke, O. (2021). ‘Winning Back control’: migration, Borders, and visions of political community. Int. Stud. 58, 150–167. doi: 10.1177/00208817211002001

Schmidtke, O. (2024). Migration as a building bloc of middle-class nation-building? The growing rift between Germany’s Centre-right and right-wing parties. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 50, 1677–1695. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2024.2315350

Schroeder, R. (2020). The dangerous myth of populism as a thin ideology. Populism 3, 13–28. doi: 10.1163/25888072-02021042

Schroeder, W., Ziblatt, D., and Bochert, F. (2025). Hält die Brandmauer? Eine gesamtdeutsche Analyse: Wer unterstützt die AfD in den deutschen Kreistagen (2019–2024) (No. SP V 2025–501). WZB Discussion Paper.

Stavrakakis, Y. (2014). The return of “the people”: populism and anti-populism in the shadow of the European crisis. Constellations 21, 505–517. doi: 10.1111/1467-8675.12127

Vachudova, M. A. (2021). Populism, democracy, and party system change in Europe. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 24, 471–498. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102711

Webb, P., and Bale, T. (2014). Why do Tories defect to UKIP? Conservative party members and the temptations of the populist radical right. Polit. Stud. 62, 961–970. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12130

Keywords: conservative parties, culture wars, populism, Germany, United Kingdom, electoral politics

Citation: Schmidtke O (2025) Transforming the centre right in Germany and the United Kingdom: the increasing prominence of identity politics and “culture wars” narratives. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1562638. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1562638

Edited by:

Marco Lisi, NOVA University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Santiago Pérez-Nievas, Autonomous University of Madrid, SpainUwe Jun, University of Trier, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Schmidtke. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Oliver Schmidtke, b2ZzQHV2aWMuY2E=

Oliver Schmidtke

Oliver Schmidtke