- 1College of Politics and Governance, Mahasarakham University, Mahasarakham, Thailand

- 2Department of Civil Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

This study examines how Thai citizens perceive China as a potential threat, with a focus on the differences between urban and rural populations. Using data from the Asian Barometer Survey’s third to sixth waves, spanning from 2010 to 2022, the analysis employs ordered probit regression to assess how residential location, democratic values, and trade protectionist attitudes influence perceptions of China’s influence in Thailand and across Asia. The study reveals a notable divide in how Thai citizens perceive China, with urban residents more inclined to view China as a threat compared to their rural counterparts. Urban skepticism reflects exposure to competitive markets, critical media, and global political discourse, which frame China’s regional behavior as a challenge to democratic norms and national autonomy. In contrast, rural populations tend to hold more neutral or positive views, likely influenced by the tangible material benefits derived from Chinese engagement, such as infrastructure investment and agricultural trade. The findings highlight the need for targeted policy responses in Thailand. Officials should implement targeted policy responses: increasing transparency in bilateral agreements, promoting civic oversight of foreign investment, and strengthening media literacy to address public distrust in urban areas. In rural areas, efforts should prioritize inclusive benefit-sharing and protecting local autonomy in development planning. For Chinese policymakers, the results underscore the limits of uniform public diplomacy, calling for adaptive strategies that respect Thailand’s internal diversity.

1 Introduction

Understanding how populations in Southeast Asia perceive China’s expanding influence has become increasingly crucial amid intensifying economic interdependence and geopolitical competition in the region (Tu et al., 2024). Although extensive scholarship has examined perceptions of China in Northeast Asia—especially in the context of strategic rivalry involving Japan and South Korea (Chu, 2021; Gong and Nagayoshi, 2019)—Southeast Asia remains underexplored by comparison, despite its increasing exposure to Chinese trade, infrastructure projects, and political diplomacy (Karim et al., 2025). Within this broader landscape, Thailand presents a compelling setting to examine public attitudes toward China, given its historical relationship, cultural ties, and dual alignment with both China and the United States (Skaggs et al., 2024). Rather than asserting centrality, the current study uses Thailand as an illustrative case that reflects wider patterns of ambivalence and diversity in threat perception across the region.

When it comes to Thailand-China relations, many studies describe an overall positive relationship between the two countries, noting the long-standing historical connections, geographical proximity, and mutually beneficial economic cooperation (e.g., Cai et al., 2024; Lauridsen, 2020; Hewison, 2018). Chinwanno (2009) argues that Thailand and China share a deep connection through the Lancang-Mekong River, resulting in strong historical, cultural, economic, and security ties. Similarly, Lee (2024) characterizes the diplomatic relationship between China and Thailand as one of peaceful coexistence and mutually beneficial cooperation.

However, a closer examination of the historical relationship reveals a more complex picture—one in which the past plays a significant role in shaping perceptions of China’s influence (Raymond, 2017; Zhang and Zhu, 2023) across different population centers. After the Chinese Communist Party took control of mainland China in 1949, Thailand’s approach to China was shaped by the former’s concerns about the potential spread of revolutionary ideas from China (Chambers, 2005; Withitwinyuchon, 2024). As a result, the Royal Thai government implemented measures to control and assimilate the growing Chinese population within the country, including efforts to promote the Thai language and culture as well as restrictions on their political activities (Von Feigenblatt et al., 2010). Propaganda campaigns and public education programs throughout the Cold War era significantly damaged China’s image among the Thai people (Hewison, 2020; Meesuwan, 2023).

The end of the Cold War in the early 1990s and China’s economic rise, which began in the late 1990s and accelerated through the 2000s, dramatically transformed the bilateral dynamic. Much of China’s outward economic engagement has flowed through maritime routes, particularly via the South China Sea and the Strait of Malacca, linking Chinese ports with key Southeast Asian economies. Within this network, Thailand has emerged as one of the strategic destinations for Chinese trade and investment. China has surpassed Japan as Thailand’s largest trading partner since 2013, with trade between the two countries reaching nearly $105 billion in 2023 (Ministry of Commerce Thailand, 2024). Chinese investment has also flowed into Thailand, especially in the transportation, technology, and agriculture sectors. In 2023, Chinese investment in Thailand totaled 430 projects, accounting for 30.85% of all foreign direct investment projects in the country. The combined investment value from China totaled approximately $4.55 billion, representing 24.03% of the total foreign investment value. The machinery and automotive sector, which includes battery electric vehicle (BEV) manufacturing, emerged as the leading site of Chinese investment, followed by the electrical appliances and electronics sector and then the metal and materials sector (Thailand Board of Investment, 2024).

Through Confucius Institutes and royal family relationships, China has systematically fortified its cultural influence in Thailand (Zhou, 2021). Regarding the former, since its establishment at Khon Kaen University in 2006, Thailand’s Confucius Institute network has expanded to 17 locations—the highest national count in Southeast Asia—with Mahidol University marking the latest addition on June 26, 2023 (Confucius Institute, 2024). Beyond promoting Chinese language education, the Chinese government utilizes these institutes as strategic platforms from which to disseminate Beijing’s official narratives on history, society, and politics while cultivating stronger economic bonds. By 2018, the impact of China’s educational diplomacy had become readily apparent: Thailand was China’s second-largest source of international students after South Korea, boasting 28,608 enrollees (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 2019). Most significantly, Thai students who study in China consistently develop more favorable attitudes toward the country, underscoring the remarkable success of China’s educational and cultural diplomacy initiatives (Lin and Kingminghae, 2023; Yan, 2023).

At the same time, China has cultivated strong ties with Thailand’s royal family. Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, who began studying Chinese in 1980 and became the first Thai royal family member to visit China in 1981, has played a crucial role in cultural diplomacy between the two countries. Her contributions include authoring 24 books about China and translating Chinese works into Thai (Kietigaroon, 2020; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2022). These diplomatic bonds deepened when Queen Sirikit, accompanied by Princess Sirindhorn, represented King Bhumibol on a 15-day official visit to China in 2000. The effectiveness of the royal engagement approach has not gone unnoticed by Thai officials; documents from Thailand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs acknowledge China’s deliberate strategy of leveraging the Thai royal family’s influence to construct a positive image of the country among the Thai population (Ministry of Foreign Affairs Thailand, 2001).

The intensifying competition between China and the United States has, in addition, reshaped how various segments of Thai society perceive China’s growing presence. The rivalry appears to reinforce existing domestic divisions rooted in political identity, historical memory, and spatial experience (Pepinsky and Weiss, 2021; Lertpusit, 2018). These spatial differences, often manifesting as an urban–rural divide, can expose populations to distinct economic opportunities, information flows, and state presence, thereby shaping their perceptions of external actors, such as China. The Thai context demonstrates that internal divisions contribute to complex patterns of perception regarding China. Charoensri (2022) elaborates on Thailand’s involvement in regional connectivity schemes, positioning the country to navigate overlapping spheres of influence. Further elaborating, Charoensri (2024) documents that Thai government officials regard China as a strategic partner, specifically in domains such as trade expansion and geopolitical coalition. In contrast, NGOs in Thailand emphasize risks associated with environmental harm, economic overreliance, and political interference, reflecting differing institutional priorities and public constituencies.

Chow et al. (2025) provide additional insight by examining how Thailand’s authoritarian governance structure aligns with China’s regional presence. Their findings demonstrate that pro-government actors perceive China as a normative partner and a source of regime security, without adequately accounting for rural and urban populations’ perspectives. Opposition groups, including pro-democracy movements, tend to express distrust toward China, associating its role with authoritarian entrenchment and elite collusion. These divergent responses stem from ideological fragmentation and demonstrate that threat perception operates through layered domestic filters rather than a singular national logic.

Despite growing scholarly interest in China’s increasing influence in Southeast Asia, a critical gap remains in understanding how these patterns are perceived at the individual level, particularly across rural and urban populations. Previous research has rarely used empirical methods to assess how perceptions of China as a potential threat differ within these diverse communities. The absence of empirical data limits our ability to grasp the nuanced impact of China’s presence and inform policy responses.

To address the crucial research lacuna, this study aims to provide a more granular understanding of these dynamics in Thailand. We have two primary objectives:

1. To empirically examine the extent of the urban–rural divide in Thai perceptions of China.

2. To identify the key demographic, ideological, and contextual factors—such as economic attitudes and political values—that shape these perceptions across different population centers.

By achieving these objectives, our study will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of how everyday political experiences and internal diversity influence perceptions of external actors, ultimately providing a more nuanced view of threat perception in Southeast Asia.

2 Literature review and research framework

The conceptual development of threat perception in international relations (IR) has undergone a significant shift, evolving from materialist, state-focused paradigms toward cognitively complex models that incorporate psychological and experiential elements at the individual level. The following literature review outlines the intellectual trajectory, emphasizing how public evaluations of China’s international position are shaped. A central contention is that many existing studies disregard the role of ordinary citizens in shaping assessments of external danger. Crucially, the discussion highlights the importance of spatial context—above all, the divide between rural and urban populations—in influencing divergent evaluations of China, alongside other explanatory factors, including age, educational background, income level, and ideological leanings.

Threat perception, at its core, involves recognizing that a foreign actor possesses both the capability and the intent to inflict harm or obstruct critical interests. The conceptual basis, originally formalized by Davis (2003), underscores the importance of both material capacity and hostile motivation. Stein (2013) enhances the view by underscoring the significance of belief structures, suggesting that individual interpretations frequently determine whether another actor is viewed as a threat. Foundational insights of this kind helped pivot IR theory away from strictly material factors and toward an acknowledgment of subjective, emotionally mediated judgments, setting the stage for an expanded role of psychological inquiry in foreign policy analysis.

Early contributions to the study of threat in IR were dominated by realism. Within both classical and neorealist branches, danger is presumed to emerge from the anarchic character of the global system. States, driven by the imperative of survival, view shifts in power capabilities with suspicion. Waltz (1979) emphasizes military strength, resource control, and regime durability as the primary components influencing a state’s vulnerability to aggression. Mearsheimer’s offensive realism posits that all-powerful states trigger caution in others due to the constant potential for dominance. Although valuable for understanding macro-level trends, realist models cannot explain why similar material circumstances prompt differences.

A significant refinement of realist thought emerged with Walt (1987) “balance of threat” theory, which included perceived intent, geographical proximity, and offensive potential as crucial variables. However, this framework still centers on structural determinants and does not explore how individuals come to interpret other nations as threatening.

In response to the limitations of state-level analysis, liberal and constructivist approaches broadened the analytical repertoire. Democratic peace theory, for instance, asserts that political systems with similar norms and institutions are less prone to mutual hostility. Constructivists go further, proposing that historical narratives, collective memory, and culturally embedded identities mediate foreign policy outlooks. Wendt (1999) famous observation that “anarchy is what states make of it” frames international danger as a socially constructed rather than objectively determined phenomenon. Empirical research supports constructivist propositions. Rousseau and Garcia-Retamero (2007) show that shared identity traits between states significantly diminish perceived danger—even when capability asymmetries exist. Their findings affirm that cultural familiarity and recognition can temper materialist threat evaluations.

Nevertheless, the prevailing emphasis on IR remains state-centric. Even social constructivism tends to equate identity with national categories, neglecting variation at the citizen level. Recent work in neuroscience and political psychology has emphasized the importance of individual cognition. Landau-Wells (2024) critiques the conceptual rigidity of traditional IR theories, proposing a typology that separates general fear from targeted recognition of hostility. These threat categories map onto distinct brain processes—especially within the amygdala and prefrontal cortex—that influence both emotional responses and analytical reasoning.

The neurocognitive perspective rejects the assumption that individuals evaluate global developments through emotionless calculation. Instead, it argues that personal background, experience, and affective responses play key roles. These arguments are particularly salient for examining reactions to China’s emergence as a global actor.

The narrative surrounding China’s rise—often described as the “China threat”—is shaped not only by Beijing’s external actions but also by internal interpretations across societies. Concerns over Chinese expansion, as noted by Goodman (2017, 2021), reflect fears of military, economic, and cultural domination. Gezgin (2023) identifies specific actions, including assertive diplomacy and defense modernization, as triggers for anxiety. Yet, the interpretation of foreign behaviors differs considerably by country and by population segment.

Historical legacy, national mythmaking, and elite discourse all influence the reception of China’s global behavior. In states with memories of territorial disputes or ideological rivalry, China is more likely to be viewed with mistrust (Yee and Storey, 2002). By contrast, where cultural affinity or economic integration is strong, perceptions tend to be more favorable. State-level theories cannot account for variation rooted in individual contexts.

What remains underexplored in the literature is how different population groups form their judgments. Much existing work relies on elite narratives or assumes uniform opinion across the citizenry. The blind spot in existing literature is particularly problematic in democratic settings, where public attitudes significantly influence foreign policy decisions. Few studies examine how citizens, especially those in varied social environments, interpret external developments.

Pomeroy (2005) states that self-perceived national strength is correlated with heightened external fear. When individuals believe their country is powerful, they may become more sensitive to potential challenges, leading to exaggerated interpretations of foreign intentions. The finding emphasizes the role of national self-image in calibrating assessments of foreign powers.

A global overview by Xie and Jin (2022) shows that favorable views of China are found in less-developed countries with high levels of economic engagement, whereas developed democracies tend to interpret China through an ideological lens. The divergence between national contexts points to the importance of domestic conditions and the necessity of incorporating micro-level dynamics into the analysis of threats.

Public opinion data underscore the need for analytical granularity when examining perceptions of China. For instance, cultural proximity, historical ties, and territorial disputes significantly influence regional views of China, as revealed by Chu et al. (2015). Although geographic neighbors may perceive China as a dominant force in Asia, attitudes vary considerably based on national experiences and internal divisions.

Focusing on Pacific Island countries, Zhang (2022) illustrates the coexistence of both positive and negative sentiments toward China. While state elites in these nations often welcome Chinese investment, civil society actors frequently voice concerns about governance and transparency (Jain and Chakrabarti, 2023). Additionally, an analysis by Sonoda (2021) of Pew and Asian Student Survey data from 2002 to 2019 suggests that many Asians perceive China as a significant and economically influential actor. However, this perceived influence does not consistently translate into favorable attitudes. The study highlights that generational factors, education, and specific bilateral relations significantly shape these perceptions. Respondents from societies involved in serious territorial disputes with China, for example, tend to express greater skepticism. These empirical results emphasize the multidimensional nature of Asian views of China and the profound impact of geopolitical, historical, and domestic factors on regional outlooks.

Geographical location is a significant factor behind people’s political and social perspectives, including their interpretations of external threats. Through extensive research on “rural consciousness,” Cramer (2016) reveals how physical location shapes worldviews and threat assessments. Conversely, Woods (2010) demonstrates how rurality can transcend geographical boundaries, incorporating distinct cultural and social phenomena that affect patterns of threat perception. The nature of urban and rural identities reveals intricate patterns of social organization and meaning. Agyeman and Neal (2009) emphasize the fluid boundaries between urban and rural spaces, and Belanche et al. (2021) characterize rurality through a focus on community and interpersonal relationships. Furthermore, Alkon and Traugot (2008) stress the role that agriculture plays in forming the rural identity, even as Murdoch and Marsden (2013) note the rural identity’s persistence in the face of rising urban convergence.

Starr and Thomas (2005) demonstrate that geographical proximity has a significant influence on patterns of threat perception. Media consumption can also significantly influence perceptions, with Jung and Jeong (2016) showcasing how coverage of China’s military rise can shape regional attitudes. When different segments of society encounter varying degrees of competition or cooperation in response to a perceived threat, the resulting dynamics become increasingly complex. Various studies have pointed to a distinct urban–rural divide when it comes to threat perceptions, with Tabory and Smeltz (2017) notably demonstrating that “urbanicity” significantly influences how people perceive foreign policy decisions. Urban populations, due to their more substantial exposure to international media and direct competition with Chinese businesses, may develop different threat assessments than rural populations, whose primary interactions with China come through trade in agricultural products and consumer goods.

Recent research has demonstrated that physical distance interacts with economic distance and social distance to influence how populations evaluate potential threats from rising powers (Ho and Lee, 2024; Tzeng et al., 2017). Economic considerations play a central role, as Li et al. (2016) have revealed that perceived conflicts of financial interest significantly impact threat assessments. When different segments of society encounter varying degrees of competition or cooperation with a country perceived as a threat, the dynamics that stem from this variance become increasingly intricate. Along both geographical and socioeconomic boundaries, the confluence of spatial, social, and economic variables demands rigorous scientific scrutiny to understand the formation of patterns in threat perceptions (Sinkkonen and Elovainio, 2020; Zhai, 2023). The emergent patterns of public attitudes carry particular significance for Thailand due to its complex relationship with China as an emerging regional power. By revealing how internal societal divisions shape foreign threat perceptions of an emerging superpower, the longitudinal and cross-sectional scholarship enriches international relations theory.

Despite advances in theory, empirical studies generally overlook variation at the level of individual citizens. Most investigations concentrate on elite decision-making, cultural narratives, or national-level rhetoric, typically assuming uniform threat interpretation within a given society. The assumption of uniformity, however, does not reflect how public opinion operates in pluralistic contexts. In democratic systems especially, public beliefs influence state behavior in ways that demand analytical attention. Rousseau and Garcia-Retamero (2007) emphasize that citizen-level threat assessments are informed by group identification, personal vulnerability, and varying exposure to information sources.

To disentangle the complexity of threat perception, it is crucial to incorporate control variables that account for socio-demographic variations. Age reflects generational narratives, with younger cohorts being more globally oriented and more critical of perceived authoritarianism. Education increases exposure to transnational political values, while income influences perceptions of competition and vulnerability. Media exposure, as observed in multiple studies, acts as a filter and an amplifier, conditioning the information environment in which individuals form judgments (Zheng et al., 2024).

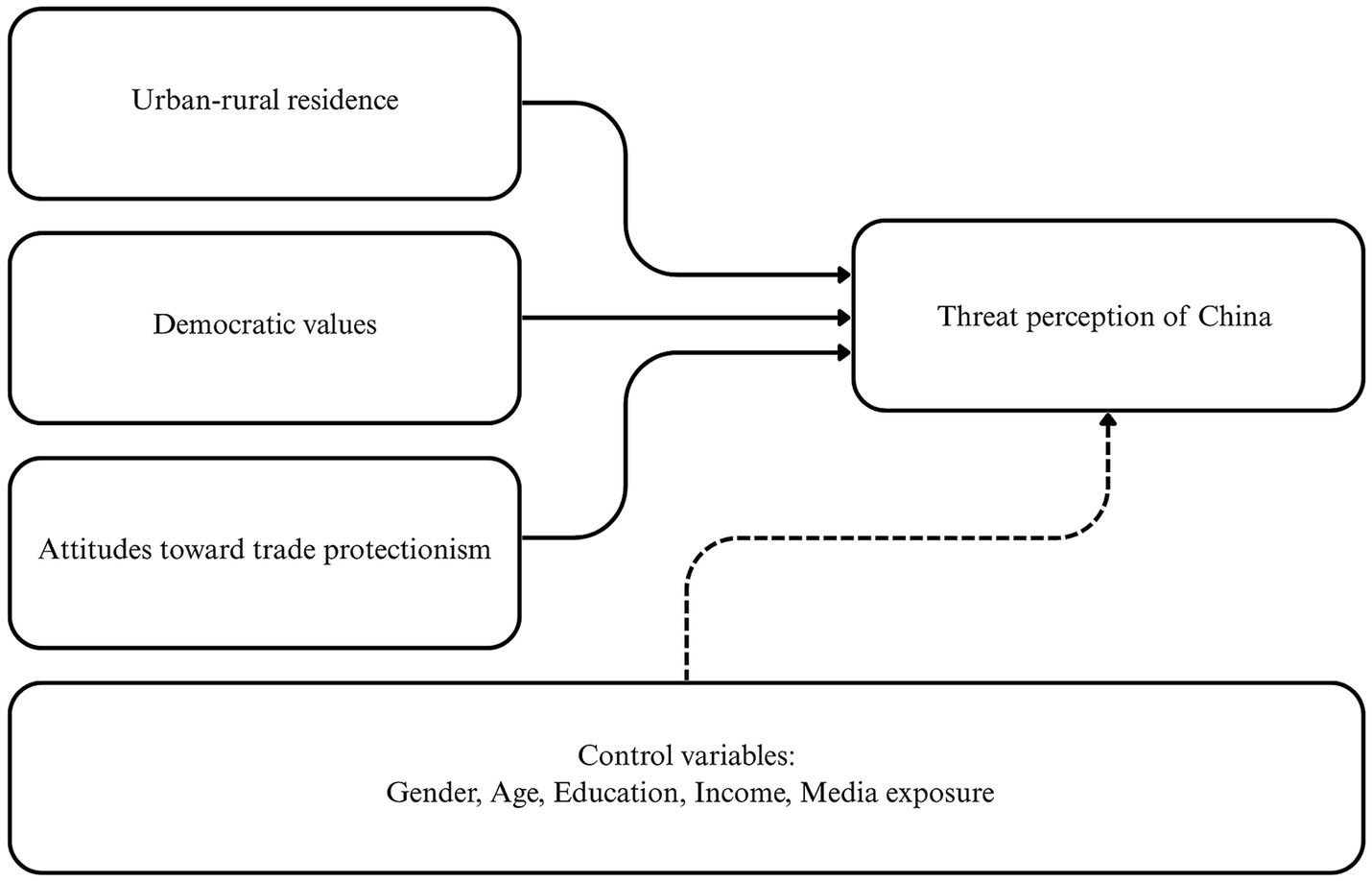

The empirical and theoretical insights from international relations and political psychology support the formulation of a conceptual framework that models threat perception as an outcome of spatial, ideational, and economic logic. The framework, as illustrated in Figure 1, incorporates three core elements. First, urban–rural residence captures geographic and socio-political positioning within national development and globalization processes. Second, democratic values and attitudes toward trade protectionism serve as mediating variables that explain how place-based identity translates into the evaluation of China’s role. Third, control variables—gender, age, education, income, and media exposure—are included to isolate the effects of primary predictors and account for heterogeneity in political cognition.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework linking urban–rural residence, democratic values, and attitudes toward trade protectionism to threat perception of China.

By incorporating explanatory theories from multiple disciplines, the framework on subnational threat perception advances the understanding of how attitudes toward China are formed, mediated, and contested. The conceptual structure allows for the identification of ideological, structural, and informational mechanisms that mediate public responses to rising powers. This layered approach examines whether the urban–rural divide persists when accounting for these additional factors.

From the conceptual framework, two hypotheses were developed as follows:

H1: Urban and rural residents perceived that China treats them differently, controlling for age, gender, news exposure, education, and household income.

H2: The urban-rural perception divide remains significant even after controlling for ideological factors, namely democratic values and attitudes toward trade liberalism.

Thailand presents a vibrant case for exploring these dynamics. The country’s geopolitical orientation, economic dependence on China, and pluralistic political environment create fertile ground for divergent interpretations. Rural populations often encounter China through agricultural trade or state-led investment, while urban residents engage with global political discourse and Chinese firms competing in the service sector. Mapping these perceptions requires an integrated analytical framework that places social geography and individual psychology at the center of threat analysis.

By accounting for how geography and individual traits interact with macroeconomic and ideological trends, researchers can better explain why citizens form divergent assessments of China’s role. The approach shifts the focus away from undifferentiated national narratives toward a more nuanced understanding rooted in local experiences and identities.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Data source

The dataset used in this research originates from the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS), an organization that conducts opinion surveys related to political participation, political values, attitudes toward globalization, and perceptions of foreign powers among populations across various Asian countries (Asian Barometer Survey, 2024). Thailand has consistently participated since the first wave began in 2005, extending to the most recent sixth wave, conducted in 2022. This study leverages explicitly data from the third through the sixth waves, as questions addressing perceptions of China at national and regional levels were first introduced in the third wave.

In Thailand, the ABS collaborates closely with King Prajadhipok’s Institute to administer surveys across all waves. The targeted respondents are Thai citizens aged 18 years and older. The third through sixth waves comprise samples of 1,512, 1,200, 1,200, and 1,200 respondents, respectively, totaling 5,112 respondents when combined.

This research uses pooled data from multiple survey waves. Utilizing pooled data enhances statistical validity by increasing sample size and statistical power, thereby enabling more robust and reliable inferences about longitudinal trends and patterns (Fitzmaurice et al., 2012). Additionally, pooling data helps manage and mitigate inconsistencies or anomalies across individual survey periods, improving overall reliability and representativeness (Curran et al., 2008). Importantly, from the third to the sixth wave, Thailand predominantly experienced military governance with brief interludes of democratic transition. By pooling data across these politically similar periods, the analysis captures consistent contextual conditions, allowing for more accurate evaluations of public perceptions.

3.2 Variables in the study

3.2.1 Dependent variables

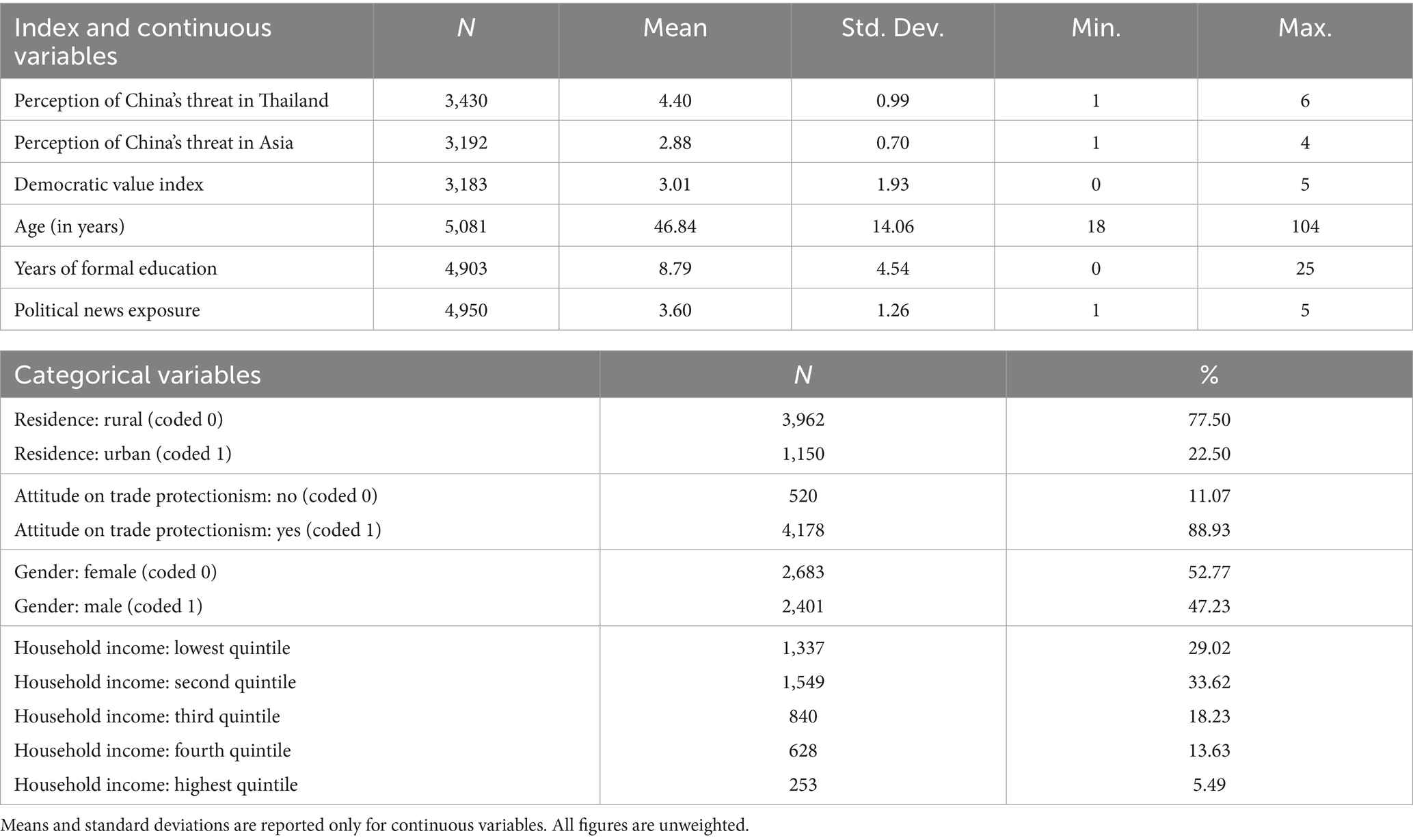

The item “Generally speaking, the influence China has on our country is?” from the ABS was adopted based on the definition of threat perception explained in Section 2, serving as one of the study’s dependent variables. Respondents indicated their perceptions on a six-point ordinal scale ranging from 1 (very positive) to 6 (very negative). This measure explicitly captured Thai respondents’ perceptions of the potential threat posed by China’s influence or actions within Thailand, effectively evaluating perceptions of Chinese influence at the national level. To measure threat perceptions toward China at the regional level, the survey included the item “Does China do more good or harm to the region?.” Responses were recorded using a four-point ordinal scale: (1) “Much more good than harm”; (2) “Somewhat more good than harm”; (3) “Somewhat more harm than good”; or (4) “Much more harm than good” (Table 1).

These two dependent variables complemented each other by jointly covering national and regional perceptions, thus providing a comprehensive evaluation of varying levels of perceived threat from China. Before statistical analysis, both measures were recoded to ensure consistent alignment of their interpretative directionality. This recoding ensured that lower numerical scores represented negative perceptions toward China, while higher scores indicated more positive attitudes. Treating these variables as ordinal allowed the subsequent statistical analysis, particularly ordered probit regression, to accurately reflect the inherently ranked structure of respondents’ threat perceptions.

3.2.2 Explanatory variables

The primary explanatory variable is residential location. According to the ABS Thailand Technical Reports, the surveys conducted in Thailand from the third through the sixth waves applied systematic, multi-stage sampling techniques to achieve comprehensive coverage of both rural and urban populations. Across all waves, the sampling process involved selecting provinces, districts (Amphoe), sub-districts (Tambol), and villages (Muban) proportionate to their populations. This hierarchical sampling structure ensured representative inclusion of diverse geographic and socio-economic contexts. Greater Bangkok was frequently designated as a distinct sampling region due to its urban characteristics and high population density, underscoring the methodological rigor in explicitly distinguishing between urban and rural contexts within the sampling framework (Asian Barometer Survey, 2024).

The consistent and proportional selection of primary and secondary sampling units, based on population distribution, guarantees a robust representation of the urban–rural divide. Each wave’s sampling closely reflected demographic realities by systematically drawing respondents from administrative units proportionally to their population sizes. Reserve samples were extensively prepared and effectively utilized to address potential non-responses, thereby enhancing statistical robustness. Consequently, the urban–rural classification derived from these systematically stratified samples accurately captures Thailand’s geographic and demographic diversity, offering a solid empirical basis for analyzing rural–urban divides in political attitudes and perceptions toward external actors, such as China. As a dichotomous variable, the residential location was transformed into a binary indicator, with 1 for urban and 0 for rural. Table 1 displays the distribution of respondents by urban–rural residence, revealing that rural respondents comprise the majority at 77.50% of the total sample.

Another explanatory variable added is democratic values. According to Huang (2024), understanding democracy involves assessing whether individuals recognize and value institutional components, such as competitive elections, independent media, and constraints on authoritarian rule. The following five survey questions from the ABS—focused on regime preference and essential beliefs about political governance—serve as a reliable instrument to evaluate citizens’ cognitive grasp of democratic norms.

1. “Which of the following statements comes closest to your own opinion?” with options: (a) “Democracy is always preferable to any other kind of government”; (b) “Under some circumstances, an authoritarian government can be preferable to a democratic one”; (c) “For people like me, it does not matter whether we have a democratic or a non-democratic regime.”

2. “Which of the following statements comes closer to your own view?” with options: (a) “Democracy is capable of solving the problems of our society”; (b) “Democracy cannot solve our society’s problems.”

3. “If you had to choose between democracy and economic development, which would you say is more important?”

4. “If you had to choose between reducing economic inequality and protecting political freedom, which would you say is more important?”

5. “Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: ‘Democracy may have its problems, but it is still the best form of government.’”

Each question captures a distinct aspect of cognitive endorsement of democratic governance—ranging from general regime preference to trade-off decisions involving democracy versus economic priorities. These survey items correspond to widely accepted theoretical definitions of democratic commitment, where the emphasis lies on citizens’ ability to recognize key features of democratic rule, differentiate them from alternatives, and express consistent normative support (Shin and Kim, 2018).

To operationalize responses for analysis, each item was converted into a binary format, where “yes” indicates correct recognition of a democratic principle and “no” reflects the absence of such recognition. Then, the five items were aggregated into a single index ranging from 0 to 5. A score of 0 indicates no evidence of democratic cognition, while a score of 5 reflects a high level of cognitive engagement with democratic values. The binary recoding and summation method are grounded in previous empirical work that treats belief consistency and conceptual understanding as indicators of internalized democratic orientation (Freeze and Montgomery, 2016).

The resulting index offers a coherent and interpretable measure of democratic commitment. By combining regime evaluation, institutional preference, and willingness to prioritize civil liberties over other objectives, the measure provides a nuanced understanding of the public’s perception of democracy. The composite variable is instrumental in assessing variation across individuals or social groups and supports the analysis of cognitive prerequisites for democratic legitimacy. Scholars, including Dahl (2008) and Schmitter and Karl (1991), have emphasized that democratic durability depends not only on institutional design but also on the extent to which citizens endorse foundational political principles.

The final explanatory variable captures attitudes toward trade protectionism, which, as discussed in Section 2, may influence how individuals perceive China as a threat. The survey item “We should protect our farmers and workers by limiting the import of foreign goods” was used to measure this economic orientation. Responses were recoded into a binary format, where a value of 1 represents agreement and expresses support for protectionist trade policy, while a value of 0 represents disagreement. The wording of the item reflects a generally accepted approach in political economy scholarship, where preference for trade restrictions is associated with perceived economic vulnerability and opposition to global market integration (Mansfield and Mutz, 2009; Scheve and Slaughter, 2001). The emphasis on safeguarding domestic producers—specifically farmers and workers—corresponds with empirical findings that individuals experiencing economic insecurity or fearing foreign competition tend to endorse restrictive trade policies (Hainmueller and Hiscox, 2006). Given China’s dominant role in international trade, endorsement of import limitations serves as a meaningful indicator of economic defensiveness. It helps explain variations in perceptions of China’s influence as either beneficial or threatening.

3.2.3 Control variables

To ensure the validity of the analysis investigating how urban–rural residence influences perceptions of China as a threat, the study controls for key demographic and informational factors that could otherwise confound the observed relationships. These encompass gender, age, years of education, household income, and frequency of exposure to political media. Gender, recoded as a binary variable (male = 1, female = 0), adopts a standard approach supported by existing research, which indicates that men and women may diverge in their geopolitical attitudes. Studies frequently show men exhibiting greater political efficacy and assertiveness in foreign affairs (Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Age, a continuous variable, captures generational variation in political outlook (Jennings and Richard, 2014). We measure education by total years of formal schooling, controlling for cognitive sophistication and exposure to abstract political concepts—factors that research suggests link to broader political attitudes, including those relevant to foreign policy (Inglehart and Welzel, 2005).

Household income, categorized into quintiles by the ABS (1 = lowest income group, 5 = highest), accounts for material conditions that may shape sensitivity to China’s economic and strategic presence. Media exposure is measured using the item “How often do you follow news about politics and government?” with responses recoded on a five-point scale where higher values reflect more frequent engagement. Regular political media consumers are more likely to encounter narratives that frame China in either adversarial or cooperative terms, which may shape attitudes independently of residential location (Li and Chitty, 2009). Including these control variables allows the model to isolate the independent effect of urban–rural location on threat perception, ensuring that the explanatory power of geography is not conflated with differences in demographic structure, socioeconomic position, or informational access. Details of all control variables are presented in Table 1.

3.3 Analytic strategy

As the dependent variables—threat perceptions of China—are ordinal, ordered probit regression was employed to estimate the models. This method is suitable for ordinal outcome variables, which are ranked, but the intervals between categories are not assumed to be equal (Greene, 2012; Long, 1997). Two levels of perceived threat are examined: (1) China’s influence inside Thailand and (2) China’s influence in Asia. Ordered probit regression enables the estimation of the probability that an individual falls into a given category of threat perception while accounting for latent, continuous attitudes underlying the observed ordinal responses.

At each level of analysis (Thailand and Asia), two models are estimated. The first model examines whether urban–rural residence is associated with threat perception, controlling for demographic and informational variables (H1). The second model extends the analysis to test H2, examining whether democratic values and attitudes toward trade protectionism further explain variation in threat perception beyond the baseline controls. In addition, since this study pools data from four waves of the ABS, wave-fixed effects are included to control for unobserved time-specific variations that may influence perceptions of China across years.

The ordered probit specifications for Model I and Model II are as follows:

Model 1:

Model 2:

In both equations, Yi* represents the unobserved latent variable for threat perception, with the observed ordinal categories determined by estimated cut points. Coefficients are interpreted in terms of the direction of association with the probability of falling into higher categories of threat perception. The models were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation, appropriate for nonlinear categorical outcomes.

4 Results

4.1 Thai perceptions of China’s threat to Thailand and Asia

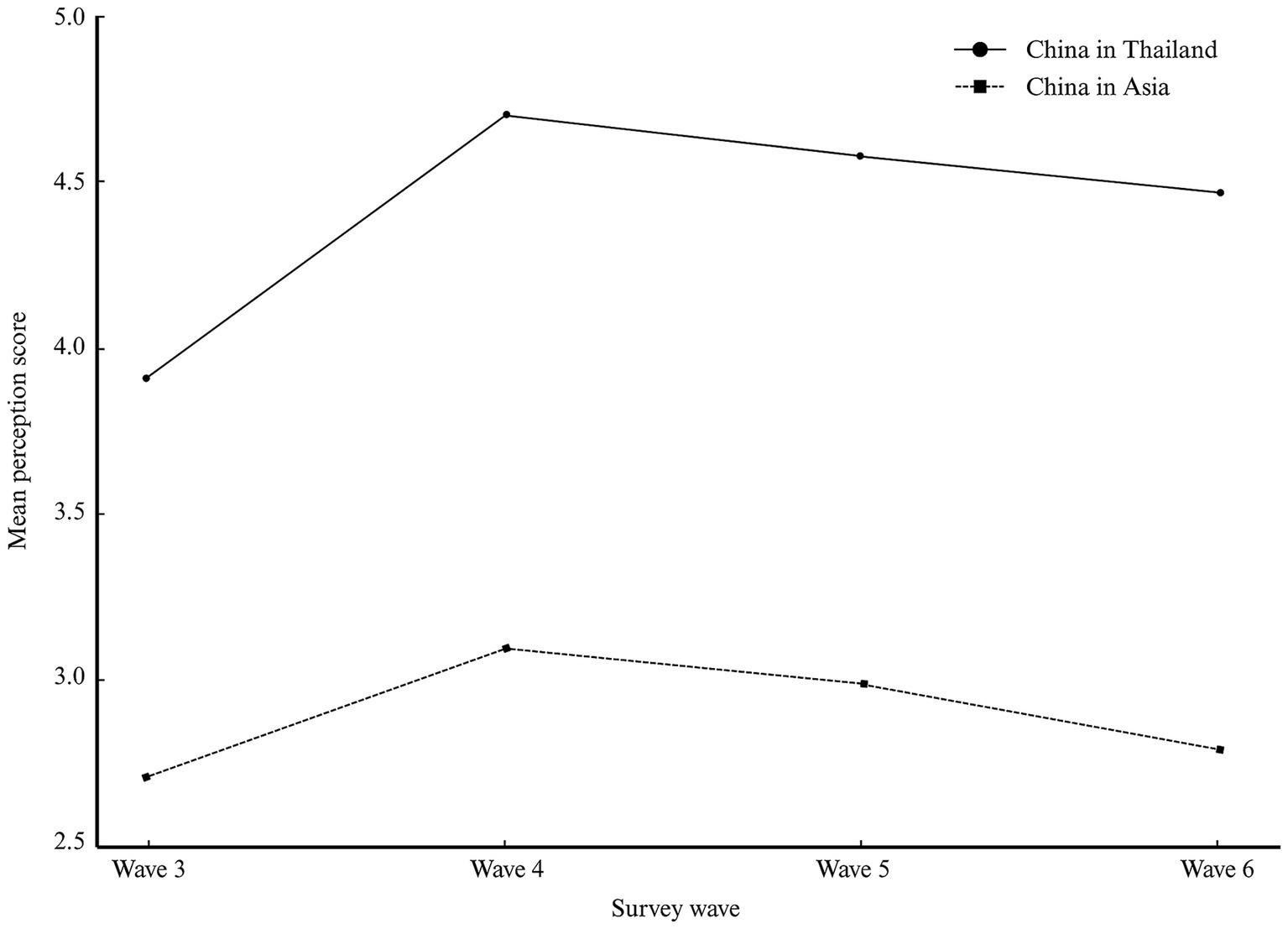

Public attitudes in Thailand toward China’s influence have evolved, influenced by domestic political developments and shifting regional geopolitics. Figure 2 illustrates these trendlines, showing Thai perceptions of China from Wave 3 to Wave 6 at two levels. More details on the descriptive statistics of Thai perceptions of China by survey wave are provided in Supplementary Appendix Table A1. Both measures use ordinal scales, with higher scores indicating more favorable views of China. The observed patterns underscore that Thai sentiment is dynamic and influenced by contextual factors that shape the public’s interpretation of China’s role.

Figure 2. Trends in Thai perceptions of China’s influence in Thailand and Asia, 2010–2022. Mean perception scores are plotted by Asian Barometer Survey wave (3 to 6). Higher values indicate more favorable views. “China in Thailand” refers to perceived influence at the national level; “China in Asia” reflects regional-level evaluations.

One-way analysis of Variance (ANOVA) results confirm significant variation in Thai perceptions of China across survey waves, encompassing China’s influence within Thailand and its perceived role in Asia. For China’s domestic influence, the ANOVA shows a statistically significant difference across waves, F(3, 3,426) = 123.54, p < 0.001, indicating a meaningful shift in Thai citizens’ evaluations. Similarly, analysis of China’s regional role reveals significant differences, F(3, 2,772) = 45.92, p < 0.001, highlighting a dynamic trend in how Thais assess Beijing’s actions.

These findings must be interpreted in the context of Thailand’s domestic political developments and China’s evolving international behavior. The third wave, conducted in late 2010 during the Abhisit Vejjajiva’s administration, characterized a period of elite-aligned governance. China had yet to fully adopt the assertive international posture that would define Xi Jinping’s leadership after 2012, contributing to more neutral or moderate public perceptions in both domestic and regional contexts.

The sharp increase in favorable perceptions during the fourth wave directly correlates with Thailand’s major political rupture: the military’s 2014 ousting of Yingluck Shinawatra’s elected government. While Western powers, including the United States and the European Union, imposed diplomatic pressure on Thailand, criticizing the coup and urging a return to democracy, China offered immediate diplomatic support and refrained from criticism. This contrasting international response is likely to have shaped Thai public sentiment (Bunyavejchewin and Buddharaksa, 2024). As Zawacki (2021) explains, the post-coup junta significantly relied on China for political legitimacy and economic partnership amidst waning Western engagement. China, in turn, deepened bilateral ties through infrastructure deals, tourism promotion, and increased financial investments, with a focus on urban areas. Beijing’s consistent engagement and investment have translated into the spike in favorable domestic perceptions observed in the fourth Wave.

Concurrently, China transformed Xi Jinping, marked by the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and ideological campaigns such as the China Dream. These initiatives enhanced China’s visibility as a global actor and reshaped its image across the Southeast Asian public. For many Thais, growing engagement with an assertive and supportive China at a time of diplomatic isolation plausibly presented Beijing as a beneficial partner, mitigating perceptions of threat.

However, the enthusiasm observed in the fourth wave proved unsustainable. By the fifth wave (late 2018 to early 2019), public perceptions began to temper. Even though Thailand remained under General Prayut Chan-o-cha’s military-backed government, the novelty of China’s partnership had waned. While economic ties persisted, a growing awareness emerged regarding the potential downsides of Chinese influence. Urban residents, initially benefiting from increased trade and tourism, began to voice concerns over real estate speculation, tourism-induced crowding, and the growing dominance of Chinese capital. Such issues became even more pronounced by the sixth wave in 2020.

The slight downturn in perception of the sixth wave aligns with several new sources of tension. Although China’s regional footprint continued to expand, Thai public sentiment grew more ambivalent. This may reflect broader fatigue with ongoing domestic military rule, alongside skepticism about whether Chinese influence delivered long-term benefits to ordinary citizens. Furthermore, high-profile controversies, such as China’s actions in the South China Sea, even though geographically distant, likely contributed to an undercurrent of regional anxiety. Xi and Primiano (2020) emphasize that China’s maritime assertiveness, especially its confrontations with the Philippines, casts a long shadow over Southeast Asia’s perception of Beijing, influencing general attitudes even when Thailand is not directly involved.

ANOVA results confirm that fluctuations in Thai perceptions of China are systematic, reflecting deeper structural and political dynamics rather than random occurrences. China’s diplomatic support positively influenced its image during periods of Thai political instability; nonetheless, the long-term implications of its expanding influence, a notable focus in economic and cultural spheres, have introduced new anxieties. For example, reports in the Bangkok Post highlighted public discontent with Chinese investment projects, which were perceived as benefiting elites or undermining local businesses (Chantanusornsiri, 2024). In addition, widely shared complaints on Thai social media (Banterng, 2017; Raymond, 2019) regarding Chinese tourists reinforced perceptions of cultural intrusion, contributing to a more complex and ambivalent image of China among the Thai populace.

In essence, the perceptions of Thai citizens toward China have evolved in tandem with Thailand’s domestic political cycles and China’s rise as a regional power. Initially, public approval surged when Beijing was seen as a source of diplomatic and economic support, especially during times of Thailand’s international isolation. In contrast, the subsequent decline in this approval indicates an emerging wariness concerning China’s intentions and the uneven distribution of benefits stemming from its growing presence in the country.

4.2 Urban–rural differences in perceptions of China in Thailand and Asia

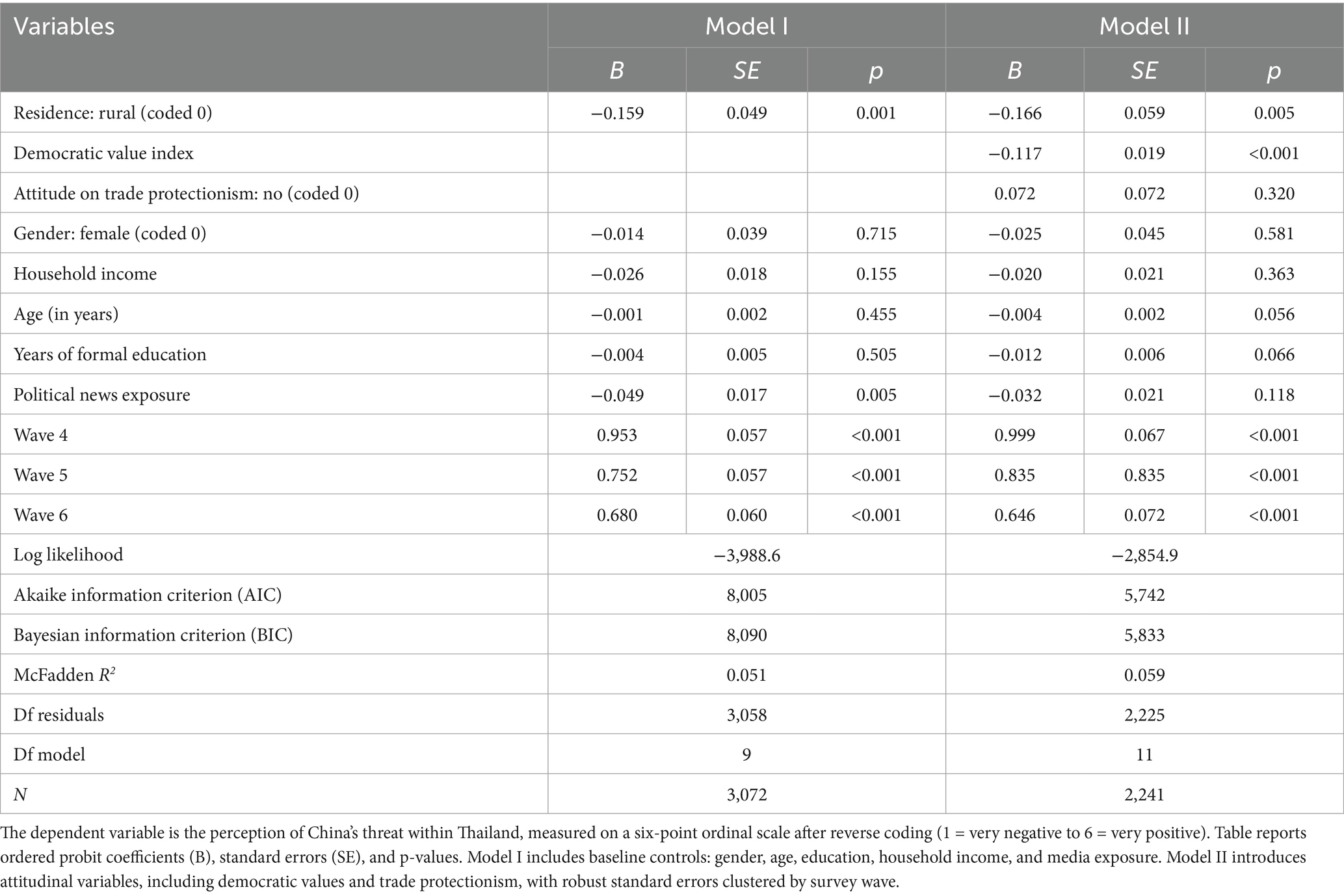

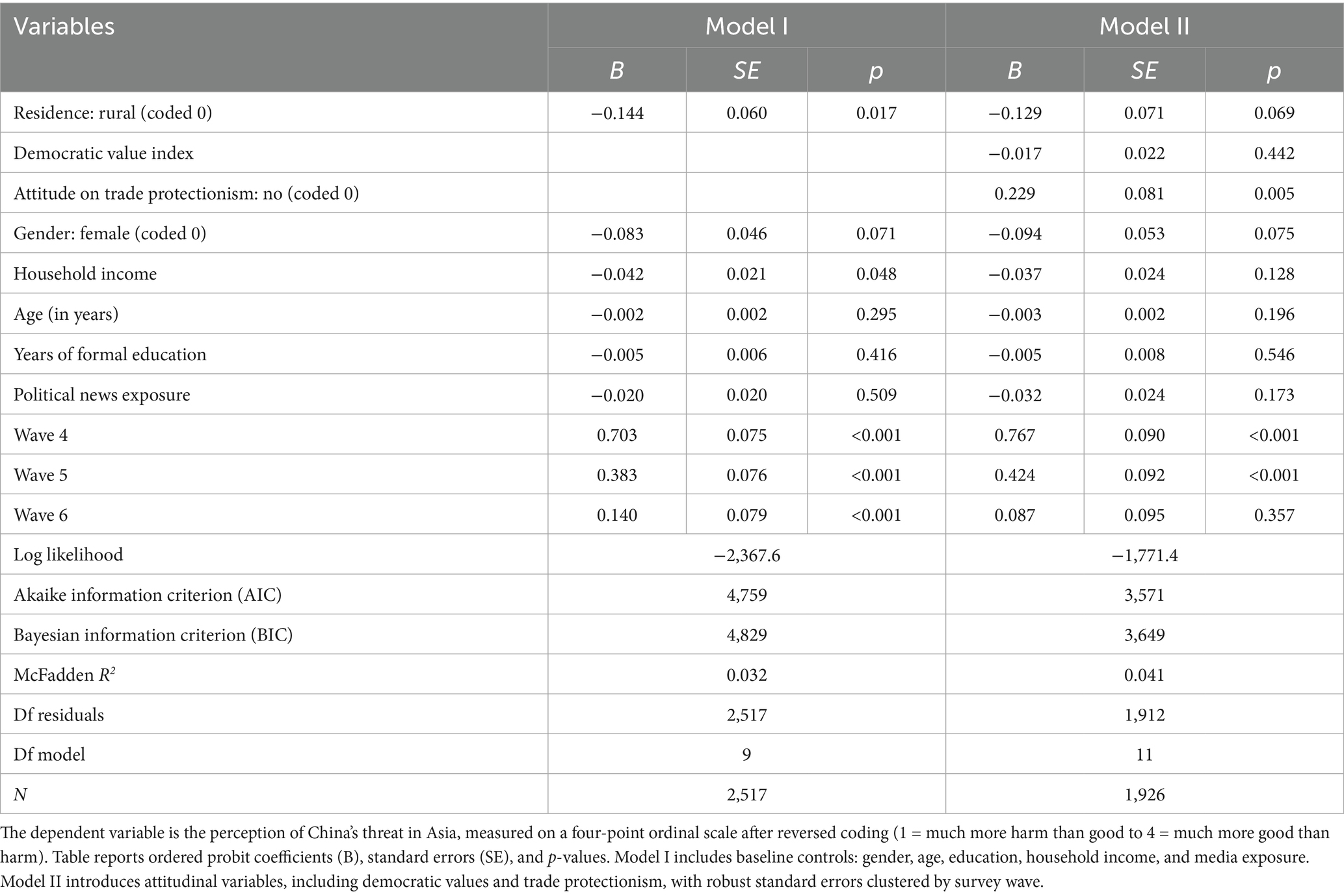

The ordered probit regression models presented in Tables 2, 3 assess the relationship between urban–rural residence and Thai perceptions of China’s influence within Thailand and throughout Asia. These models control for a range of demographic variables and, in their extended forms (Model II), incorporate attitudinal predictors—namely democratic values and trade protectionism preferences.

Beginning with Table 2, urban residents were associated with more negative evaluations of China’s presence compared to their rural counterparts. This relationship remains robust even after accounting for individual characteristics, underscoring that spatial location has a distinct and independent effect on threat perception. The urban–rural coefficient remains negative and statistically meaningful for all models, suggesting that spatial divisions reflect more profound divergences in political cognition and evaluative frameworks.

Model II of Table 2 delineates the ideological dimensions of this spatial divide. Once democratic values and attitudes toward trade protectionism are introduced, the strength of the urban variable persists, while the attitudinal predictors themselves emerge as significant. Democratic commitment appears associated with more skeptical views of China, indicating that perceptions are partly driven by value-based dissonance. Citizens who embrace norms such as political accountability and civic participation tend to view China’s influence as inconsistent with domestic democratic aspirations. Similarly, respondents less favorable to trade openness are more inclined to perceive China as a threat—likely interpreting China’s economic engagement as a source of strategic vulnerability.

Table 3 shifts the focus to perceptions of China’s threat in Asia more broadly. Again, urban residency predicts more negative views, but the strength of this association slightly attenuates once political attitudes are introduced in Model II. Democratic values again play a decisive role, affirming their salience in shaping how regional power dynamics are interpreted. Trade attitudes also exhibit a clear pattern; individuals who favor trade protection tend to view China’s regional ambitions more critically, suggesting that economic nationalism is linked to assessments of strategic threats.

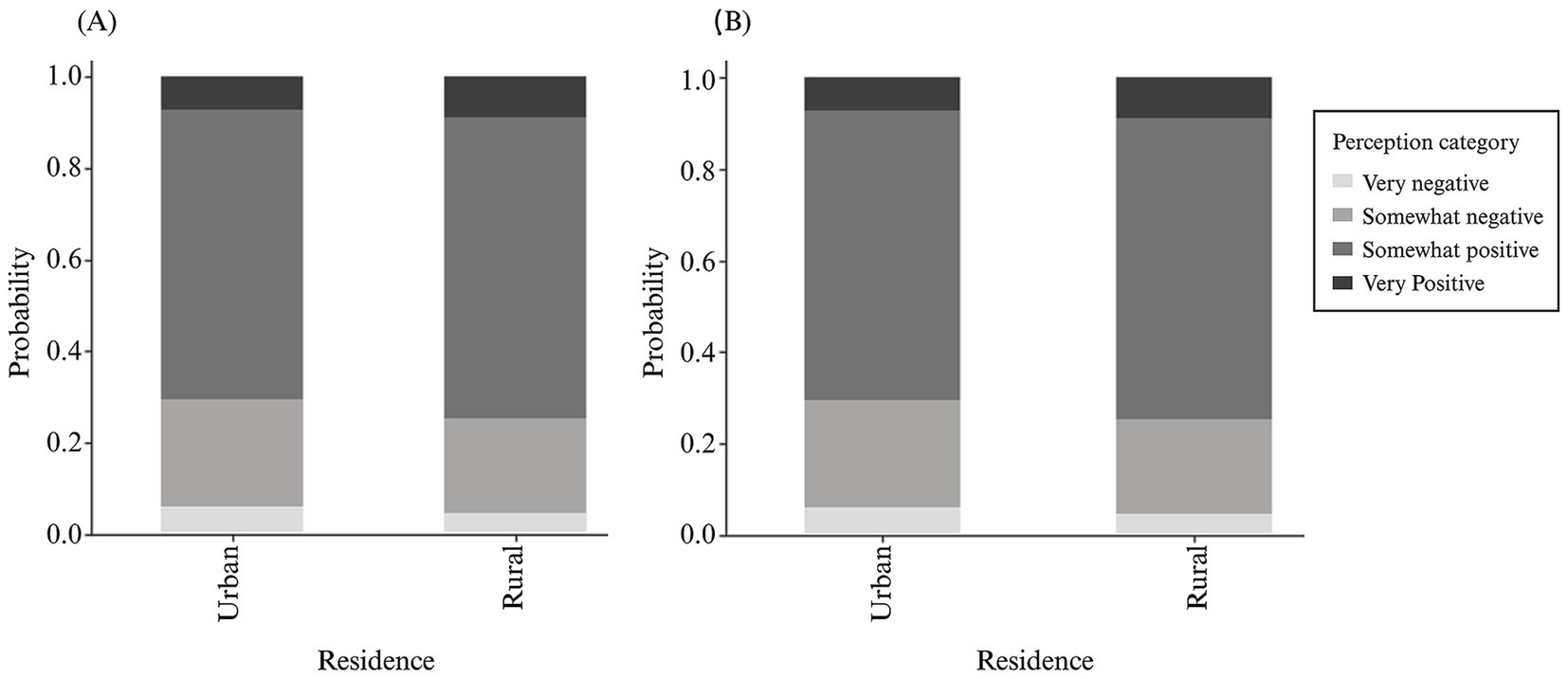

This pattern is further clarified by the predicted probability plot (Figure 3), which shows that urban respondents are modestly more inclined to express “very negative” or “somewhat negative” views about China’s role in Asia compared to rural respondents. However, the gap is narrower than that observed in the domestic context. The majority of responses in each group cluster around “somewhat positive” evaluations, suggesting that views of China’s regional role are more moderate and less polarized.

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities of threat perception of China by urban–rural residence. (A) Predicted probabilities of perception categories for China’s influence in Thailand. (B) Predicted probabilities for China’s influence in Asia. Probabilities are based on ordered probit regression models using Asian Barometer Survey data (waves 3 to 6), controlling for demographic and attitudinal covariates. Urban residents are more likely to select negative response categories, particularly in a national context.

Notably, in the examined models and tables, the inclusion of democratic values and trade preferences improves model fit, as reflected in improved AIC and BIC scores and higher pseudo R-squared values. These shifts confirm that perceptions are not formed in a vacuum; they are shaped and filtered through political beliefs and ideological predispositions that frame China as either a normative challenger or an economic opportunist. The consistent statistical contribution of democratic values for domestic and regional measures suggests that skepticism toward China stems from a broader expression of regime dissonance—China as an illiberal actor in a region where democratic aspirations remain salient—beyond merely reacting to local developments.

Control variables, including education and age, show a relatively muted influence, with few achieving statistical significance. Media exposure consistently registers a negative association with favorable views of China across all models. This directional pattern persists, with statistical significance varying between specifications. The wave dummies reveal temporal shifts in perception, potentially reflecting changes in geopolitical events or domestic Thai politics. A more targeted time-series analysis would be required to precisely unpack those shifts.

To examine the reliability of the estimated coefficients, multicollinearity diagnostics were conducted using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). All predictor variables reported VIF scores well below the threshold of 2, with the highest being 1.70 for education level (see Supplementary Appendix Table B1). The VIF results indicate a low degree of collinearity among the explanatory variables. The absence of problematic multicollinearity strengthens confidence in the estimated effects of urban residency, political attitudes, and socioeconomic controls on perceptions of China’s influence.

5 Discussion

Our findings confirm H1 and H2: significant urban–rural divides persist in China’s threat perception, with urban Thai citizens expressing more negative views of China’s influence than their rural counterparts. This outcome contributes meaningfully to the development of threat perception theory by highlighting how localized social structures and value orientations shape interpretations of China’s influence. In Thailand, urbanity extends beyond a mere spatial designation; it embodies a distinct matrix of political cognition, economic exposure, and information access that collectively intensifies perceptions of China as a normative and strategic threat.

Recent research on cultural messaging helps illuminate the dynamics at work. Tang and Hou (2024) find that younger, educated, urban Thais tend to approach China’s cultural diplomacy with suspicion, even when they acknowledge the country’s technological and economic achievements. For these groups, Chinese cultural exports are not viewed as benign forms of exchange but as calculated instruments of influence. The urban public, shaped by exposure to global narratives and critical discourse, often reads Chinese outreach not as an invitation to mutual understanding but as a strategy to extend political leverage under the guise of cultural cooperation.

Urban residents in Thailand are typically deeply embedded in competitive economic sectors, such as manufacturing, services, and international trade, feeling the impact of China’s rise most acutely (Srisamoot, 2022). Chinese investment and market dominance within these sectors are regarded not only as economic developments, but also as disruptive forces that jeopardize livelihoods and autonomy (Chantasasawat, 2006). This direct exposure to competitive pressure intensifies suspicion toward China’s intentions, prompting an interpretation of its regional assertiveness as an infringement on Thailand’s economic self-determination (Li et al., 2016; Xie and Jin, 2022).

Earlier work by Chinvanno (2015) anticipated this divergence, noting a growing divide between Thailand’s foreign policy elite—who generally embrace closer ties with Beijing—and urban public segments more attuned to concerns about democratic erosion and strategic dependence. As institutional cooperation with China expands, public trust does not necessarily deepen. In fact, for politically active urbanites, China’s growing presence may appear to constrain rather than enable Thailand’s political future.

The influence of democratic values intensifies this critical stance. As Skaggs et al. (2024) argue, attitudes in Thailand are structured not merely by preferences for one regime type over another but by deeper commitments to principles such as transparency, public accountability, and civic participation. From this standpoint, when China is seen to act in ways that sidestep those norms—whether through opaque infrastructure deals or assertive diplomacy—urban citizens are more likely to interpret such behavior as normatively incompatible with democratic ideals. As a result, the association between democratic convictions and wariness toward China is not simply ideological but reflects a broader value-based dissonance.

Information also plays a critical role. Access to global news channels and civil society discourse means urban citizens are more likely to encounter narratives about China’s actions in the South China Sea, crackdowns on dissent, or the export of authoritarian governance models. These exposures reinforce cognitive associations between China and undemocratic behavior, deepening perceptions of threat (Zheng et al., 2024). What begins as geopolitical awareness becomes filtered through ethical and political expectations, making threat perception both moral and strategic.

On the other hand, rural respondents often interpret China’s presence through more immediate, tangible experiences (Punyaratabandhu and Swaspitchayaskun, 2018). In areas that benefit from infrastructure investments or agricultural trade, China may be viewed less as a threat and more as an economic partner. With lower exposure to critical media and global discourse, rural residents tend to frame China’s engagement in pragmatic terms, without the normative overlays that are standard in urban interpretations. This distinction highlights how physical location intersects with political identity to shape perceptions of external actors.

What emerges, then, is a bifurcated interpretive structure that is consistent with Pavlićević and Kratz’s (2018) conceptualization: political values, media consumption, and economic vulnerability to global competition shape urban perceptions of threat. Rural acceptance, conversely, is grounded in localized experience and material evaluation. This divergence supports the proposition of integrated threat theory that perceptions of threat are multidimensional, encompassing both realistic and symbolic, as well as economic and ideational aspects.

These findings offer a corrective to alarmist or overly optimistic paradigms that treat China as either a savior or a menace in simplistic terms. Echoing Pavlićević and Kratz’s (2018) critique of the “bifocal lens,” this study demonstrates that perceptions of China as a threat emerge from the interpretive frameworks available within Thai society, not solely from Beijing’s actions. Those frameworks are shaped by social position, economic interest, and political orientation. In the urban Thai context, China is viewed not as a singular actor but as a symbol of more profound anxieties about the resurgence of authoritarianism, regional hierarchy, and the fragility of democratic norms.

In practical terms, the findings imply that urban Thai skepticism toward China may not diminish even if China undertakes more cooperative or transparent policies. The interpretive lens through which its actions are seen has already been shaped. By contrast, rural support may persist despite broader regional concerns because China is evaluated through the prism of immediate utility instead of long-term strategic calculation. These asymmetries suggest that any policy engagement with Thailand must be attuned to subnational perception structures if it hopes to influence public opinion.

In summary, the development of threat perception toward China in Thailand cannot be reduced to material power balances or elite diplomacy. It emerges from citizens’ social location, their value commitments, and the cognitive filters they apply to international events. Urban–rural divisions serve as both analytical and empirical markers of how the threat is conceptualized—not as a fixed judgment but as a process rooted in differentiated experience. As China’s influence continues to expand across Southeast Asia, these internal divides will become increasingly important for understanding regional responses, affecting not just foreign policy alignment but also the very construction of political meaning itself.

To bridge the growing gap in perceptions, Thai policymakers need to implement tailored engagement strategies that resonate with both urban and rural populations, as follows:

1. Enhancing transparency and informed discourse in urban areas: For urban constituencies, building trust in dealings with China requires greater transparency. This entails openly sharing details about bilateral agreements, particularly in areas such as infrastructure, technology, and education. By aligning these collaborations with democratic norms and public accountability, suspicion can be significantly mitigated. Furthermore, to foster a critically informed public, media literacy campaigns and open forums on foreign policy are essential. These initiatives will empower urban residents to engage thoughtfully and knowledgeably with global affairs.

2. Ensuring equitable benefits and community autonomy in rural areas: In rural communities, where views of China are generally shaped by agricultural investment and employment opportunities, the focus must be on tangible benefits and local control. Policies should prioritize the equitable distribution of economic gains from Chinese ties, ensuring that local communities directly share in prosperity. Crucially, efforts must also safeguard community autonomy, preventing any erosion of local decision-making power as economic connections deepen. This approach will help avoid future backlash and foster sustainable relationships.

3. Fostering regional consensus through cross-national dialog: Beyond national strategies, ASEAN partners, including Thailand, should proactively address potential regional cleavages. This can be achieved by establishing cross-national platforms for public opinion research and dialogue. By understanding and anticipating diverse subnational perspectives on China-related initiatives, ASEAN can strengthen regional consensus and ensure a more unified approach to complex foreign policy challenges.

For Chinese policymakers, the findings underscore the limitations of one-size-fits-all public diplomacy strategies in Thailand; what appeals to rural pragmatism may alienate urban democratic sensibilities, requiring more nuanced and locally adaptive communication.

6 Conclusion

This examination of the rural–urban divide in Thai perceptions of China as a threat reveals complex dynamics demanding further scholarly attention. Notwithstanding prior studies offer valuable insights, significant gaps persist in understanding how these specific perceptions develop and interact with broader societal transformations. Recognizing this, the present study provides novel insights into the urban–rural divide in Thai perceptions of China, though it is subject to several limitations.

Primarily, the reliance on cross-sectional survey data precludes the analysis of longitudinal trends in threat perception or the definitive establishment of causal relationships between specific factors and perceptual shifts. Furthermore, while Thailand offers a compelling illustrative case, directly generalizing these findings to other diverse Southeast Asian nations—each with unique historical contexts and relationships with China—warrants cautious interpretation. Subsequent research can address these limitations by employing longitudinal designs, conducting comparative regional studies, and exploring more nuanced measures of key variables and spatial categorizations.

Moreover, future research should explore the intersection of economic modernization and traditional security concerns across Thailand’s geographical spectrum. The rapid development of digital connectivity and social media penetration in rural areas, for instance, offers a unique opportunity to study how online information flows shape threat perceptions differently than more traditional, urban-centric media channels. This vital aspect remains understudied despite its growing relevance.

Data availability statement

The data used in this study were collected by the Asian Barometer Survey and are available at https://www.asianbarometer.org/datar?page=d10. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Author contributions

SM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PS: Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research project was financially supported by the Mahasarakham University, Thailand.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Generative AI statement

The authors used Claude AI to improve grammar and readability. The authors declare that they reviewed and rewrote the final draft prior to submitting the manuscript for publication and take full responsibility for all content in the research paper.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1564586/full#supplementary-material

References

Agyeman, J., and Neal, S. (2009). “Rural identity and otherness” in International encyclopedia of human geography. eds. R. Kitchin and N. Thrift (Amsterdam: Elsevier Ltd), 227–281.

Alkon, A. H., and Traugot, M. (2008). Place matters, but how? Rural identity, environmental decision making, and the social construction of place. City Community 7, 97–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6040.2008.00248.x

Asian Barometer Survey. (2024). Data release. Available online at: https://www.asianbarometer.org/datar?page=d10 (Accessed November 1, 2024).

Banterng, T. (2017). China’s image repair: the case of Chinese tourists on social media in Thailand. Glob. Media J. 15:84.

Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., and Rubio, M. A. (2021). Local place identity: a comparison between residents of rural and urban communities. J. Rural. Stud. 82, 242–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.01.003

Bunyavejchewin, P., and Buddharaksa, W. (2024). Thailand’s China policy, 2014–2019: hedging against China? Heliyon 10:e33366. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33366

Cai, J., Dong, J., and Zhang, J. (2024). “Relations between China and Thailand after the establishment of the people’s republic of China: analysis of the reasons for the change from antagonism to cooperation” in Addressing global challenges-exploring socio-cultural dynamics and sustainable solutions in a changing world. ed. P. M. Eloundou-Enyegue (London: Routledge), 42–48.

Chambers, M. R. (2005). ‘The Chinese and the Thais are brothers’: the evolution of the Sino- Thai friendship. J. Contemp. China 14, 599–629. doi: 10.1080/10670560500205100

Chantanusornsiri, W. (2024). Analyst wary of Chinese threat perception: negative sentiment growing in Thailand. Available online at: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/general/2853633/analyst-wary-of-chinese-threat-perception (Accessed November 2, 2024).

Chantasasawat, B. (2006). Burgeoning Sino-Thai relations: heightening cooperation, sustaining economic security. China Int. J. 4, 86–112. doi: 10.1353/chn.2006.0002

Charoensri, N. (2022). Thailand and regional connectivity development in the Mekong. Asia Policy 17, 50–56. doi: 10.1353/asp.2022.0026

Charoensri, N. (2024). The clashes within: how do Thai government agencies and NGOs view China’s rise? Asian Perspect. 48, 459–478. doi: 10.1353/apr.2024.a935486

Chinvanno, A. (2015). Rise of China: a perceptual challenge for Thailand. Rangsit J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2, 13–18.

Chinwanno, C. (2009). “Rising China and Thailand’s policy of strategic engagement” in The rise of China: Responses from Southeast Asia and Japan (NIDS joint research series 4), 81–109.

Chow, W., Khemanithathai, S., and Han, E. (2025). Under China’s shadow: authoritarian rule and domestic political divisions in Thailand. Internat. Relations Asia Pacific 25:lcaf002.

Chu, J. A. (2021). Liberal ideology and foreign opinion on China. Int. Stud. Q. 65, 960–972. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqab062

Chu, Y. H., Kang, L., and Huang, M. H. (2015). How east Asians view the rise of China. J. Contemp. China 24, 398–420. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2014.953810

Confucius Institute. (2024). The CI worldwide: Thailand. Available online at: https://ci.cn/en/qqwl (Accessed November 14, 2024).

Cramer, K. J. (2016). The politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Curran, P. J., Hussong, A. M., Cai, L., Huang, W., Chassin, L., Sher, K. J., et al. (2008). Pooling data from multiple longitudinal studies: the role of item response theory in integrative data analysis. Dev. Psychol. 44, 365–380. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.365

Davis, J. W. (2003). Threats and promises: The pursuit of international influence. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Fitzmaurice, G. M., Laird, N. M., and Ware, J. H. (2012). Applied longitudinal analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Freeze, M., and Montgomery, J. M. (2016). Static stability and evolving constraint: preference stability and ideological structure in the mass public. Am. Polit. Res. 44, 415–447. doi: 10.1177/1532673X15607299

Gezgin, U. B. (2023). “The political psychology of ‘China threat’: perceptions and emotions” in Current approaches in social sciences. eds. A. T. Bayram, A. Asrifan, and N. Sharma (Istanbul, Turkey: Muthmainnah (Özgür Yayın Dağıtım Ltd Şti.)), 157–190.

Gong, S., and Nagayoshi, K. (2019). Japanese attitudes toward China and the United States: a sociological analysis. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 51, 251–270. doi: 10.1080/21620555.2019.1611374

Goodman, D. S. (2017). Australia and the China threat: managing ambiguity. Pac. Rev. 30, 769–782. doi: 10.1080/09512748.2017.1339118

Goodman, D. S. (2021). The China threat: global power relations, political opportunism, economic competition. México y la Cuenca del Pacífico 10, 9–32. doi: 10.32870/mycp.v10i30.774

Hainmueller, J., and Hiscox, M. J. (2006). Learning to love globalization: education and individual attitudes toward international trade. Int. Organ. 60, 469–498. doi: 10.1017/S0020818306060140

Hewison, K. (2018). Thailand: an old relationship renewed. Pac. Rev. 31, 116–130. doi: 10.1080/09512748.2017.1357653

Hewison, K. (2020). Black site: the cold war and the shaping of Thailand’s politics. J. Contemp. Asia 50, 551–570. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2020.1717115

Ho, S., and Lee, T. (2024). Elite perceptions of a China-led regional order in Southeast Asia. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 44, 148–173. doi: 10.1177/18681034241294093

Huang, M. (2024). Confucian culture and democratic values: an empirical comparative study in East Asia. J. East Asian Stud. 24, 71–101. doi: 10.1017/jea.2023.23

Inglehart, R., and Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: The human development sequence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jain, S., and Chakrabarti, S. (2023). The dualistic trends of Sinophobia and Sinophilia: impact on foreign policy towards China. China Rep. 59, 95–118. doi: 10.1177/00094455231155212

Jennings, M. K., and Richard, N. G. (2014). Generations and politics: A panel study of young adults and their parents. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Jung, H. J., and Jeong, H. W. (2016). South Korean attitude towards China: threat perception, economic interest, and national identity. African Asian Studies 15, 242–264. doi: 10.1163/15692108-12341361

Karim, M. F., Rahman, A. M., and Suwarno, W. B. (2025). Assessing the China threat: perspectives of university students in Jakarta on the South China Sea dispute and the belt and road initiative. Chin. Polit. Sci. Rev. 10, 123–147. doi: 10.1007/s41111-024-00251-5

Kietigaroon, N. (2020). Thailand as a performative state: An analysis of Thailand’s cultural diplomacy towards the people’s republic of China. [master’s thesis]. [Chulalongkorn University].

Landau-Wells, M. (2024). Building from the brain: advancing the study of threat perception in international relations. Int. Organ. 78, 627–667.

Lauridsen, L. S. (2020). Drivers of China’s regional infrastructure diplomacy: the case of the Sino-Thai railway project. J. Contemp. Asia 50, 380–406.

Lee, K. C. (2024). Promoting a positive shared future through transnational Chinese in Thailand: a case study of a self-styled Sino-Thai folk diplomat. J. Chin. Overseas. 20, 209–230. doi: 10.1163/17932548-12341516

Lertpusit, S. (2018). The patterns of new Chinese immigration in Thailand: the terms of diaspora, overseas Chinese and new migrants comparing in a global context. ABAC J. 38, 74–87.

Li, X., and Chitty, N. (2009). Reframing national image: a methodological framework. Conflict Commun. 8, 1–11.

Li, X., Wang, J., and Chen, D. (2016). Chinese citizens’ trust in Japan and South Korea: findings from a four-city survey. Int. Stud. Q. 60, 778–789. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqw040

Lin, Y., and Kingminghae, W. (2023). Studying in Shanghai and its impacts on Thai international students’ opinions towards the Chinese people and China. Educ. Process Int. J. 12, 103–125.

Long, J. S. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mansfield, E. D., and Mutz, D. C. (2009). Support for free trade: self-interest, sociotropic politics, and out-group anxiety. Int. Organ. 63, 425–457. doi: 10.1017/S0020818309090158

Meesuwan, S. (2023). The impact of collective memory on Thailand’s involvement in the belt and road initiative. J. Liberty Int. Aff. 9, 23–34. doi: 10.47305/JLIA2392022m

Ministry of Commerce Thailand. (2024). International trade statistics report of Thailand (annual). Available online at: https://tradereport.moc.go.th/th (Accessed on December 13, 2024).

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2019). Statistical report on international students in China for 2018. Available online at: http://en.moe.gov.cn/news/press_releases/201904/t20190418_378586.html (Accessed December 5, 2024).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2022). A Thai princess who travels throughout China. Available online at: https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/zy/jj/zggcddwjw100ggs/jszgddzg/202406/t20240606_11377957.html (Accessed December 5, 2024).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs Thailand. (2001). Annual report on people’s republic of China. Archives and library division Ministry of Foreign Affairs Thailand.

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Pavlićević, D., and Kratz, A. (2018). Testing the China threat paradigm: China’s high-speed railway diplomacy in Southeast Asia. Pac. Rev. 31, 151–168. doi: 10.1080/09512748.2017.1341427

Pepinsky, T., and Weiss, J. C. (2021). The clash of systems? Washington should avoid ideological competition with Beijing. Foreign Affairs. Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-06-11/clash-systems (Accessed December 3, 2024).

Pomeroy, C. (2005). The damocles delusion: the sense of power inflates threat perception in world politics. Int. Organ. 79, 1–35. doi: 10.1017/S0020818324000407

Punyaratabandhu, P., and Swaspitchayaskun, J. (2018). The political economy of China–Thailand development under the one belt one road initiative: challenges and opportunities. Chin. Econ. 51, 333–341. doi: 10.1080/10971475.2018.1457326

Raymond, G. (2017). Tipping the balance in Southeast Asia? Thailand, the United States and China. Centre Gravity Series Paper 37. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3330397

Raymond, G. V. (2019). Competing logics: between Thai sovereignty and the China model in 2018. Southeast Asian Aff. 1, 341–358.

Rousseau, D. L., and Garcia-Retamero, R. (2007). Identity, power, and threat perception: a cross-national experimental study. J. Confl. Resolut. 51, 744–771. doi: 10.1177/0022002707304813

Scheve, K. F., and Slaughter, M. J. (2001). What determines individual trade-policy preferences? J. Int. Econ. 54, 267–292. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1996(00)00094-5

Schmitter, P. C., and Karl, T. L. (1991). What democracy is… and is not. J. Democr. 2, 75–88. doi: 10.1353/jod.1991.0033

Shin, D. C., and Kim, H. J. (2018). How global citizenries think about democracy: an evaluation and synthesis of recent public opinion research. Jpn. J. Polit. Sci. 19, 222–249. doi: 10.1017/S1468109918000063

Sinkkonen, E., and Elovainio, M. (2020). Chinese perceptions of threats from the United States and Japan. Polit. Psychol. 41, 265–282. doi: 10.1111/pops.12630

Skaggs, R. D., Chukaew, N., and Stephens, J. (2024). Characterizing Chinese influence in Thailand. J. Indo-Pac. Aff. 7, 7–30.

Sonoda, S. (2021). Asian views of China in the age of China’s rise: interpreting the results of pew survey and Asian student survey in chronological and comparative perspectives, 2002-2019. J. Contemp. East Asia Stud. 10, 262–279. doi: 10.1080/24761028.2021.1943116

Srisamoot, A. (2022). “China, Thailand and globalization” in China and the world in a changing context: Perspectives from ambassadors to China. eds. H. Wang and M. Lu (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore), 181–191.

Starr, H., and Thomas, G. D. (2005). The nature of borders and international conflict: revisiting hypotheses on territory. Int. Stud. Q. 49, 123–139.

Stein, J. G. (2013). “Threat perception in international relations” in The Oxford handbook of political psychology. eds. L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, and J. S. Levy (New York: Oxford University Press), 364–394.

Tabory, S., and Smeltz, D. (2017). The urban-suburban-rural “divide” in American views on foreign policy. Chicago, IL: The Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

Tang, X., and Hou, Y. (2024). Research on the perception and evaluation of Chinese culture dissemination in Thailand: an analysis based on literature review and questionnaire survey. Communication Across border 4, 8–19.

Thailand Board of Investment. (2024). Annual foreign direct investment report 2023. Available online at: https://www.boi.go.th/index.php?page=statistics_situation (Accessed December 1, 2024).

Tu, C. C., Tien, H. P., and Hwang, J. J. (2024). Untangling threat perception in international relations: an empirical analysis of threats posed by China and their implications for security discourse. Cogent Arts Humanities 11. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2024.2335766