- Department of Psychology, Rutgers University, Camden, NJ, United States

How can emotions, and their influence on individuals and groups, be best conceptualized and studied by political scientists as well as by psychologists? Empirical work indicates that psychological theories, and research conducted by psychologists about emotions, are not only relevant but indeed important for understanding and predicting political phenomena. Building on a recent article by George Marcus, gaps are identified in Affective Intelligence Theory (AIT) and other theories of emotion that Marcus reviews, and an alternative, more comprehensive theory is delineated. The Emotion System Theory, here referred to as EST, encompasses a wider range of emotions and emotion-eliciting appraisals, and makes predictions differing from those in AIT about the determinants of political processes and specific political behaviors. For example, as distinct from AIT's focus primarily on enthusiasm, fear, and anger EST (a) defines and distinguishes among 16 positively- or negatively-valenced emotions plus the neutral-valenced emotion of surprise; (b) proposes five ways in which they can be measured; (c) specifies distinctive causes and components for each emotion; and (d) discusses their wide-ranging and often powerful impact e.g., on political information processing, communication (e.g., in campaigns and ads), candidate evaluation, voting, and various types of political participation. Together, these emotions constitute a coherent set of general-purpose response strategies for coping with crises and opportunities, within and outside of the political domain.

1 Introduction

Recent reviews (e.g., Gadarian and Brader, 2023; Redlawsk and Mattes, 2022; Redlawsk and Pierce, 2017) and empirical articles (e.g., Clifford et al., 2023; Cohen-Chen and Van Zomeren, 2018; Huddy et al., 2021; Roseman et al., 2020; Vasilopoulos et al., 2019) make clear that emotions are often manifest in political events and are important influences on political actors and processes. To cite just a few salient examples, consider the anger seen in the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol, with rioters beating police officers and threatening to kill government officials (Riley, 2022); the fear of becoming ill from COVID-19 that increased support for mask mandates among Republicans and decreased voting for Donald Trump among independents in 2020 (Mehlhaff et al., 2024); and the hope that fueled voting for Barack Obama in 2008 (Finn and Glaser, 2010).

In his ambitious target article, Marcus (2023) makes multiple contributions to advancing understanding of the nature of emotions in political science and psychology. These include affirming the importance of a comprehensive theory of emotions for understanding and predicting outcomes in political science; calling attention to the influence of multiple emotions, multiple intensities of emotions, and the multiple concurrent appraisals—each assessing a “strategically vital aspect” of situations—that elicit emotional responses; and proposing criteria for a comprehensive emotion theory. Moreover, in reviewing four theories of emotion, including Affective Intelligence Theory (AIT) which he has pioneered (e.g., Marcus et al., 2000), Marcus (2023), p. 10) is admirably modest, acknowledging that AIT is incomplete, and that more can and should be done to identify additional appraisals and emotions (see also Sirin and Villalobos, 2021) which might play a role in politics (following his counsel that a theory should be interested in “expanding its reach rather than defending its current formulation”).

In the sections that follow, I employ Marcus' (2023) criteria, phrased here as questions that can be asked of theories of emotions; identify gaps in the answers provided by the theories he reviews (especially AIT, in view of its extensive influence in political science); and compare the answers given by the Emotion System Theory (e.g., Roseman, 2011, 2013, 2018) which may fill some of these gaps. I conclude with comments on unanswered questions to be addressed by future research on emotions in political science.

According to Marcus' (2023) criteria, a theory of emotion should:

• Offer an explicit definition of emotion (Question, as per James, 1890: What is an emotion?)

• Offer a taxonomy of emotions (Question: What are the emotions?)

• Specify a measurement component (Question: How can emotions be measured?)

• Advance testable claims (Question: What are the causes and effects of emotions?)

• Be empirically falsifiable, in comparison to competing theories (Question: Has the theory been tested against alternatives?)

• Incorporate parallel processing (Question: Are multiple emotions and their elicitors processed simultaneously?)

• Integrate preconscious processing (Question: Can these emotions be elicited without reflective consciousness?)

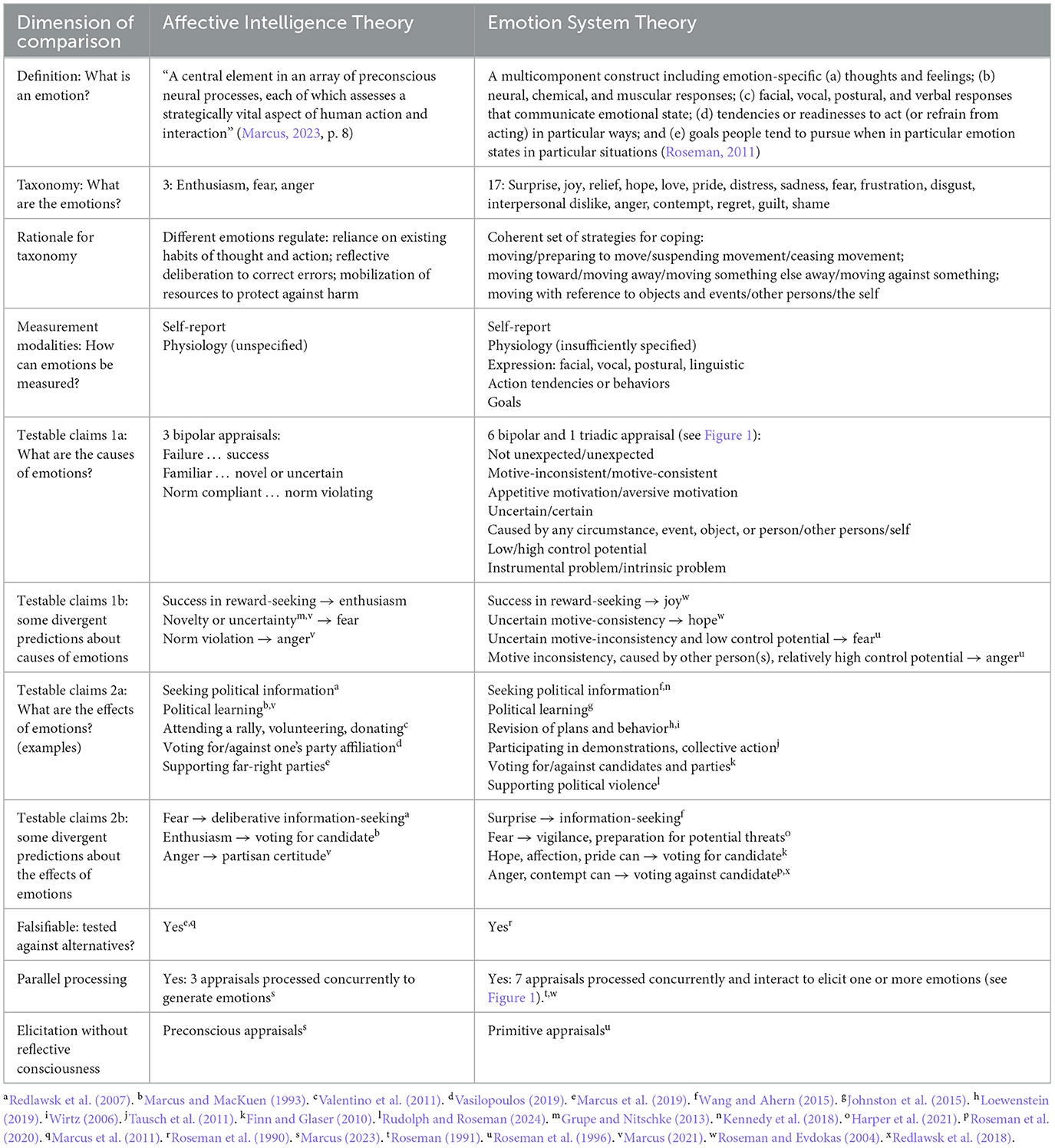

Table 1 addresses each of these questions, briefly summarizing answers provided by EST and AIT, previewing what can be found in the body of this article.

Table 1. Some important differences between Affective Intelligence Theory and Emotion System Theory.

2 Definition: what is an emotion?

Although many, including Marcus (2023), lament a lack of consensus among specific authors, there is in fact some agreement among many contemporary emotion theorists and researchers (see e.g., Ellsworth, 2024b; Fontaine et al., 2013; Moors, 2022, Axis 1; Roseman, 2011; Scarantino, 2024) on the properties of emotions (despite considerable disagreement about causal mechanisms and emotion taxonomies; see, e.g., Moors, 2022, Axes 2–4). These show that the different definitions cited by Marcus (2023) are focusing on different aspects of emotions (components and causes vs. functions), rather than incompatibilities between the theories.

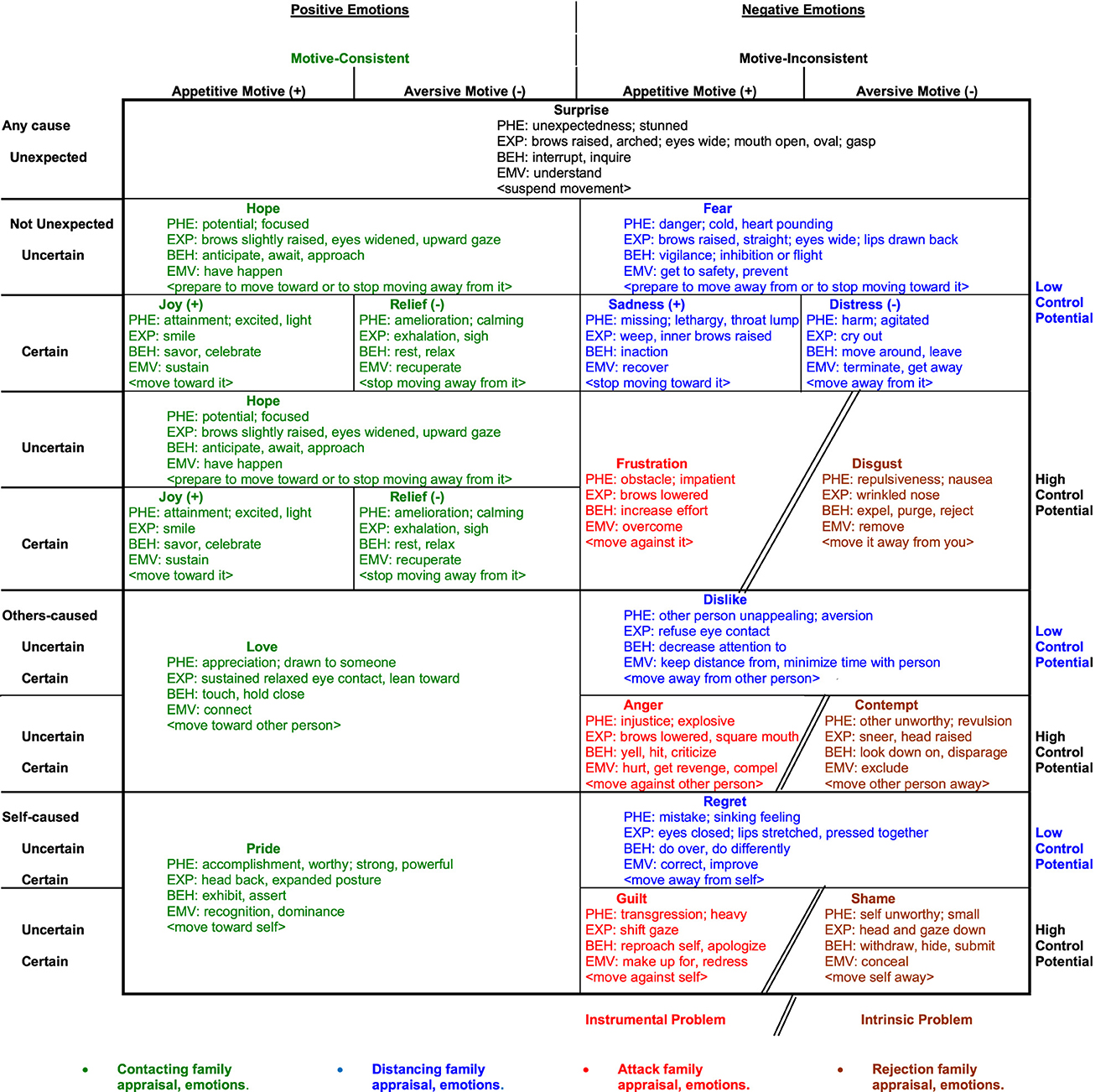

Figure 1. Hypothesized structure of the emotion system, showing appraisals and some resulting emotional responses. Emotion components: PHE, Phenomenological; EXP, expressive; BEH, behavioral; EMV, emotivational goal. Strategies integrating the response components for each emotion are given in angle brackets. Appraisal combinations eliciting each emotion are found by proceeding outward from an emotion box to its borders around the chart. Adapted and revised from Roseman, I. J. Appraisal in the emotion system: Coherence in strategies for coping. Emotion Review, 5, 141–149. Copyright ©391242013 Sage Publications. doi: 10.1177/1754073912469591

In addition, contrary to a claim by Marcus (2023), p. 7), neither the Emotion System Theory nor the appraisal theories of Frijda (1986), Lazarus (1991), or Scherer (2005), maintain that emotions are only “subjective feelings expressed in consciousness.” Instead, as in these other models that view emotions as typically elicited by appraisals, the Emotion System Theory defines an emotion as a multicomponent construct including: (a) a subjective “phenomenological” component, encompassing emotion-specific thoughts and feelings; (b) a physiological component, comprising neural, chemical, and muscular responses; (c) an expressive component, identifying facial, vocal, postural, and verbal responses that communicate a person's emotional state; (d) a behavioral component, consisting of tendencies or readinesses to act (or refrain from acting) in particular ways when in particular emotion states in particular situations; and (e) an “emotivational” (Roseman, 2011) component which distinguishes goals that individuals or groups tend to pursue when in particular emotion states. Each of these components was also specified in what Kleinginna and Kleinginna (1981), after considering 92 possible emotion definitions, viewed as a “model definition” that includes “all traditionally significant aspects of emotion” (p. 345).

For example, on the level of the individual, fear may be characterized (in part, because full specification would exceed the space available here) by thoughts about some danger (Rosen and Schulkin, 1998); feeling aroused and cold (Scherer and Wallbott, 1994); patterns of neural activity in brain networks that include the cortical and medial amygdala, hypothalamus, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and brainstem (Orederu et al., 2024); a facial expression with brows raised and drawn together, widened eyes, and lips drawn back (Ekman, 2003); behaviors such as inhibition or flight (Blanchard et al., 2001); and the goal of getting to safety (Roseman et al., 1994b; cf. Marcus, 2023, “seek[ing] security”).

In contrast, anger may be characterized by thoughts about injustice and retaliation (Averill, 1982; Litvak et al., 2010); feeling aroused (Davitz, 1969), hot (Scherer and Wallbott, 1994), energized (Hackert et al., 2021), and ready to explode (Kövecses, 2010); neural activity in the brain's medial amygdala and periacqueductal gray (Potegal and Stemmler, 2010); a face with lowered, drawn-together, furrowed brows, and tightened, pressed-together or funneled lips (Matsumoto et al., 2008); a readiness to attack others verbally (Averill, 1982) or physically (Harmon-Jones, 2003); and the goal of compelling another person's action, by harming them if need be (Fessler, 2010; Roseman, 2024).

In political contexts, fear responses have been observed, for example, in connection with concerns about terrorist attacks (Huddy et al., 2003), support for policies such as mask mandates and stay-at-home orders in response to the possibility of becoming seriously ill from Covid-19 (Mehlhaff et al., 2024), and the goal of preventing some danger or removing oneself from danger (Gadarian and Brader, 2023). Anger responses have been observed in opposition to health care reform (Banks, 2014), support for military action (Huddy et al., 2007), and voting for anti-immigrant parties (Erisen and Vasilopoulou, 2022).

Note that EST maintains that there may be variation in an emotion's responses depending upon: (a) its specific elicitors on a given occasion; (b) its intensity; (c) situational affordances and constraints on action; and (d) the occurrence of other emotions, emotion regulation, and other non-emotional cognitive, motivational, or behavioral processes at the same time as the emotion (Roseman, 2011). Thus, in people (Blanchard et al., 2001) as in other animals, fear can prompt a variety of behaviors including remaining motionless, assessing risks, fleeing, hiding, or attacking-in-order-to-escape (depending on features of the situation, such as the imminence of the threat and the availability of an escape route or a place to hide).

For example, (a) the fear elicited by planes crashing into the World Trade Center will be processed by different sensory and brain mechanisms, and is likely to elicit different behavioral responses (e.g., running away; Strozier, 2011), than the fear of contracting a deadly virus such as COVID-19 (e.g., limiting social interactions; Luo et al., 2021); (b) The annoyance produced by traffic noise (Riedel et al., 2019) will likely differ in subjective intensity and behavior from the outrage elicited by deadly attacks on one's country, as in the bombing of Pearl Harbor (Schencking, 2022), or the murder of an ingroup member like George Floyd (Rothbart, 2021); (c) The extent of both Israelis' and Palestinians' hope for peace in 2017 was found to be dependent on each group's perception of the other's hope for peace in the situation (Leshem and Halperin, 2020); (d) Anger or its effects can be lessened by co-occurring hope (e.g., for fixing the immigration system; Walter et al., 2021) or thinking about non-emotional topics (Denson et al., 2012), and increased (Zillmann, 1988) or decreased (Pels and Kleinert, 2016) by physical exercise. Disgust responses can be reduced by hunger (Hoefling et al., 2009).

I have reviewed these examples to reply to claims that variability across instances undermines the scientific status of distinct emotions (e.g., Barrett, 2009). These claims ignore the functional comparability of different emotional responses in different situations. They may also reflect the view that an emotion is a “whole body” response (e.g., Wiens, 2005) which is identical each time it occurs.

However, that is manifestly false. People can experience anger, fear, and other emotions while watching campaign ads on television, voting, attending a rally, posting online, etc. (e.g., Redlawsk and Pierce, 2017; Reicher and Haslam, 2017; Van Troost et al., 2013), and the various activities can alter thoughts, feelings, expressions, behaviors, and goals at those times. Emotions are not fixed action patterns or “natural kinds” (Barrett, 2006) that have invariant properties across all occurrences. Rather, like most phenomena in science, there are probabilistic (beyond-chance) relationships between particular emotions and particular responses (Lazarus, 1991; Roseman, 2011). And unless, like Descartes, we adopt a dualistic view, then every variation in thought, feeling, and motivation—as well as behavior—will have a corresponding physical substrate. That makes finding a “signature” for a given emotion across all instances (Barrett, 2009) exceedingly difficult. But as one's focus widens from particular brain circuits or muscle movements to adaptive behavior patterns (Plutchik, 1984) or “emotivational goals” (Roseman, 2011)—such as getting out of danger in fear (Gadarian and Brader, 2023) or compelling others' actions in anger (Sell et al., 2009)—consistencies across instances are more apparent.

3 Taxonomy: what are the emotions?

Marcus (2023) rightly criticizes valence theories as inadequate insofar as distinguishing only positive vs. negative emotions “leaves neither theoretical nor empirical space for any other emotions” (p. 6). However, similar to EST, prominent emotion theories incorporating valence generally also include other dimensions (such as certainty, agency, and control) and more than two emotions (see Ellsworth, 2024a). Indeed, most contemporary theories encompass at least four emotions (happiness or joy; sadness; fear; and anger) and many theories add other EST emotions such as surprise, disgust, contempt, pride, love, and hope (e.g., Ekman, 2003; Fontaine et al., 2013; Keltner et al., 2022; Lazarus, 1991; Smith and Kirby, 2011). None of the aforementioned theories includes enthusiasm, though Redlawsk and Mattes (2022) note that the political science literature typically does not distinguish enthusiasm from hope.

Thus, an important question is: are there really only three emotions that are relevant to politics—enthusiasm, fear, and anger? The current formulation of AIT, which focuses on those states, is vulnerable to the same limitation that Marcus (2023) attributes to valence theories. Below I will discuss the elicitation and impact of each of the 10 emotions mentioned in the previous paragraph. The Emotion System Theory encompasses a total of 16 positive or negative emotions plus the neutral-valenced emotion of surprise. These can be found in Figure 1, which details some of their phenomenological, expressive, behavioral, and goal components, as well as hypothesized appraisal determinants, for each emotion.

Systematicity I: Why these emotions? Marcus (2023) reasonably asks for a comprehensive taxonomy, preferably one not based solely on emotion words (many of which have overlapping meanings and vary from one language to another)—with a rationale for inclusion or exclusion of candidate emotions. Two rationales can be given for the emotions shown in Figure 1.

The first is empirical: although various studies have focused on different sets of emotions, the aggregated body of research has shown differences between each of the Figure 1 emotions in multiple response components (e.g., Fontaine et al., 2013; Keltner et al., 2022; Roseman et al., 1994a,b; Saarimäki et al., 2016; Tracy et al., 2007; Volynets et al., 2020) and appraisal elicitors (e.g., Ellsworth and Smith, 1988; Fontaine et al., 2013; Roseman, 1991; Smith and Ellsworth, 1985; Tong, 2010, 2015).

The second rationale is functional. Though Marcus (2023), p. 7) criticizes the taxonomies of appraisal theories as “largely ad hoc”, the emotions in Figure 1 comprise a coherent repertoire of alternative strategies for coping with the general types of opportunities and crises that people encounter (Roseman, 2013). As shown within the angle brackets at the bottom of each cell in Figure 1, these emotions involve either some form of movement, preparing movement, suspending movement, or ceasing movement; moving toward, moving away, moving something else away, or moving against something; and moving with reference to objects and events, other persons, or the self. Respectively, these function to cope with crises and opportunities that emotion-eliciting appraisals indicate are at hand, imminent, evolving, or ending; in which a typically adaptive response in the situation would be to maximize, minimize, eliminate, or change something; about the world, other persons, or the self (Roseman, 2011).

For example, surprise (an emotion not differentiated in AIT but whose elicitors and responses have been detailed by Ekman et al., 1972; Fontaine et al., 2013; Horstmann and Schützwohl, 2024; and others) involves suspending movement and processing information in order to understand unexpected events (Reisenzein et al., 2019).

The hedonically positive emotions involve different ways of getting more of something (Tolman, 1923). Joy gets more of rewarding outcomes by moving toward them (e.g., increasing contact and engagement with them; see Fredrickson, 2013; Frijda, 1986). Relief enables getting more of something by ceasing to move away from situations which might have been more aversive but in fact are not (e.g., by resting or relaxing; Lazarus, 1991; Roseman et al., 2013). Hope increases the likely experience of positive outcomes by preparing to move toward (approach) or to stop moving away from them (Roseman, 2013; Roseman et al., 2013). Love gets more by moving toward, being with, or forming a relationship with other people who cause positive outcomes (Shaver et al., 1987). Pride gets more by moving toward the self e.g., by exhibiting and asserting oneself or one's group (Weisfeld and Dillon, 2012).

The negative emotions involve different ways of getting less of something (Tolman, 1923), which, in answer to a question raised by Marcus (2023), is the unifying attribute underlying the class of negative emotions. The emotion of distress gets less of something aversive by moving away from it (e.g., Batson et al., 1987). Sadness gets less of losses, or failures to attain rewarding outcomes, by ceasing pursuit of unattainable rewards (reducing movement toward them; see Gadassi-Polack et al., 2024). Fear gets less of negative outcomes (whether aversive events or losses) by preparing people to move away from or to stop moving toward them (Lerner and Keltner, 2001; Mobbs et al., 2015). Frustration gets less by increasing effort to force change in negative outcomes (Amsel, 1992). Disgust rejects things that are intrinsically negative (Rozin et al., 2016). Interpersonal dislike, anger, and contempt (respectively) get less of negative outcomes caused by other people by moving away from (e.g., minimizing time spent with) those people (Roseman, 2024; Steele, 2020), attacking them (Frijda et al., 1989), or moving them away (e.g., breaking relationships with them, excluding them from interactions; Fischer and Roseman, 2007). Regret, guilt, and shame get less of negative outcomes appraised as caused by the self, by moving away from those outcomes (e.g., resolving not to repeat them; Zeelenberg and Pieters, 2006), attacking (e.g., reproaching) the self (Karlsson and Sjöberg, 2009), or moving the self away (e.g., concealing the self; Tangney et al., 1996).

Let us consider some examples of these emotions, functioning as described, in political contexts.

• Cohen-Chen and Van Zomeren (2018) manipulated hope that gun control measures could be implemented, which increased willingness to sign a petition, participate in a demonstration, and contribute money; lowering hope decreased willingness (see also Cohen-Chen et al., 2014).

• Analyses by Sabti and Ramalu (2024) showed that psychological distress mediated the impact of such factors as financial difficulties and political instability on Iraqi doctors' intentions to leave their home country (see also examples of distress migration in other countries in Avis, 2017).

• Sadness was identified in posts from some Parler users when the events of January 6, 2021 did not result in Trump remaining in office (Norgaard and Walbert, 2023; anger, particularly at Mike Pence, was also observed). Using survey data from 23 European countries and Israel, Landwehr and Ojeda (2021) found that symptoms of depression were associated with decreased voting and physical political participation, such as working for a political group and demonstrating in public (but see de León and Trilling, 2021; Weber, 2013).

• Disgust sensitivity is associated with opposition to immigration (Clifford et al., 2023; Karinen et al., 2019), and inducing this emotion increases rejection of gay marriage (Adams et al., 2014).

• Mattes et al. (2018) found that contempt was the emotion viewers perceived most in two broadcast ads attacking either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump in the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. Redlawsk et al. (2018) reported that contempt felt by voters toward either Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, or Donald Trump predicted decreased probability of voting for that candidate in the 2020 Iowa GOP caucus. Roseman et al. (2020) found that contempt was the emotion most strongly predicting voting against three of the four candidates in two U.S. Senate races (looking down on and breaking relations with them).

These studies provide examples of how adding hope, distress, sadness, disgust, and contempt to the emotions in AIT can help account for politically-relevant outcomes. Examples demonstrating the politically-relevant impact of pride, love, guilt, and surprise are discussed below.

The systematic nature of the taxonomy of emotions in Figure 1 can also be seen from the identification of families of emotions (Roseman, 2011), each having members that are specialized to cope with crises or opportunities caused by other persons (shown in the middle third of the chart) or the self (shown in the bottom third), in addition to those whose responses tend to be adaptive regardless of who or what was the cause (shown in the top third of the chart).

Emotions in the contacting family (shown in green in Figure 1) move people toward the events or persons that elicited them, e.g., increasing contact and interaction. Emotions in the distancing family (shown in blue) move people away from their elicitors, decreasing contact and interaction. Attack family emotions (shown in red) move against their elicitors, “contending” with them (Arnold, 1960), i.e., trying to force them to change. Rejection family emotions (shown in brown) move their elicitors away from the self.

The other-person-directed and self- (or own group-) directed emotions in the bottom two thirds of the chart can be understood as specialized members of those families that have evolved because different responses are likely to be adaptive in dealing with animate emotion elicitors. One can cope with animate sources of crises or opportunities through their motives (goals and preferences), which can be fulfilled or thwarted, and their hedonic feelings (i.e., they can be made to feel good or bad).

For example, the emotion of love (affection) moves toward other persons in social space, enhancing interpersonal closeness and connectedness, and forming relationships which increase the likelihood that individuals and groups with whom affection is shared will continue to be sources of positive outcomes. In politics this can be manifest in expressions of support and devotion of followers for a leader, as seen in the affection felt by some supporters of Donald Trump (Warner, 2024) who report completely unqualified warmth/favorability on feeling thermometer scales (Crowell et al., 2018), or wait on line for hours to attend his rallies (Justice, 2020), gratifying his desire for approval (Kohn, 2021). Using ANES data, McDonald (2023) shows that presidential candidates perceived as more compassionate (caring about people like you) got more votes in elections from 1992 to 2020.

Similarly, anger typically moves against other people in ways suited for dealing with animate sources of negative outcomes. These include inflicting physical pain, taking away benefits, and blocking the target's objectives. For example, anger felt toward candidates may be manifest in voting against them (Finn and Glaser, 2010) or working against them in campaigns (Valentino et al., 2011); and populist anger felt toward immigrants predicts support for anti-immigrant candidates and policies (e.g., Rico et al., 2017; Vasilopoulos et al., 2019). Anger felt toward people who have committed crimes motivates passage of laws mandating longer prison sentences and capital punishment (Johnson, 2009); and anger felt toward suspected terrorists underlies harsh interrogations (Carlsmith and Sood, 2009).

Outcomes seen as self-caused elicit intrapersonal ways of moving toward, away, or against. In pride, the subject self (the “I” or “we”) is moved closer to the object self (the “me” or “us”) e.g., by thinking about or displaying one's own individual or group opinions, characteristics, and accomplishments, or asserting dominance (Dickens and Robins, 2022). These are adaptive in that feeling pride enhances perseverance (Williams and DeSteno, 2008), effort, and perceived self-efficacy (Verbeke et al., 2004), and displaying pride (e.g., in parades, or by wearing political buttons or clothing declaring one's group membership or views; Corrigan and Brader, 2011; Graham et al., 2021; Peterson et al., 2018; Weisfeld and Dillon, 2012) is relatively likely to elicit positive responses from in-group members (Mercadante et al., 2021, “authentic” rather than “hubristic” pride). (Panagopoulos 2010) found that a manipulation which increases pride (informing high-propensity voters that their names would be published in a local newspaper) increased turnout in two midwestern cities. Asserting individual or in-group preferences is more likely to extend success when positive outcomes are self-caused.

In guilt, one attacks the self or one's own group in ways suited to negative outcomes which I or we have caused, e.g., via motivating self-criticism or reparative behavior that imposes costs or restrictions. For example, Dutch research participants induced to feel collective guilt about mistreatment of Indonesians (during the colonial period) endorsed giving monetary compensation, and the amount was mediated by collective guilt (Doosje et al., 1998; cf. Barkan, 2001). Guilt among priests who have sexually abused minors can prompt self-punitive behavior (Plante, 1999); and in response to clergy sexual abuse, the Catholic church undertook some reforms to prevent recurrences (Dokecki, 2004).

To account for these phenomena, emotions whose responses are specialized for dealing with other persons or the self, such as love, anger, contempt, pride, and guilt—together with their characteristic responses and effects—should be included in comprehensive models of the impact of emotions in politics. All of these emotions are included in the theories of Scherer (Fontaine et al., 2013) and (with the exception of contempt) Lazarus (1991), though some appraisal antecedents and response components differ from theory to theory (see, e.g., Roseman et al., 1990; Roseman, 2024 for details).

The emotion of surprise should also be accorded a prominent place in theories within political science and psychology, given its key role in information processing and the centrality of information processing in our understanding of important political phenomena including opinion formation, candidate evaluation, and voting (e.g., Jerit and Kam, 2023; Lau and Redlawsk, 2006; Taber and Young, 2013).

Surprise has: distinctive phenomenology—thoughts about discrepancies, and a feeling of mental interruption or interference (Reisenzein, 2000); typical physiology involving coordinated activity in eight brain networks (Zhang and Rosenberg, 2024) along with skin conductance increase, heart rate deceleration, and pupil dilation (Reisenzein et al., 2019); a prototypical facial expression with raised, arched brows, widened eyes, and open, slack-jawed mouth (Ekman, 2003); and behavioral manifestations including pausing action and attending to the eliciting event, with a goal of understanding its nature and causes (Reisenzein et al., 2019).

I noted above that the Emotion System Theory conceptualizes each emotion as a response “strategy.” These are typically not conscious plans undertaken to achieve objectives, but rather syndromes of response that have been shaped over the course of evolution to cope adaptively with particular types of situations when they are encountered. The various responses of surprise have coevolved to cope with the occurrence of something unexpected, by interrupting behavior and processing information in order to enable the modification of knowledge, opinions, actions, plans, and goals.

Each of the responses in an emotion syndrome contributes to implementing that emotion's strategy. For example, in surprise, thoughts about discrepancies from existing schemas and the feeling of mental interference contribute to revising thoughts and actions that may be outdated in light of the unexpected eliciting information. The widened eyes and opened mouth of the surprise expression enhance information intake, and pausing behavior enables reallocation of attention to this information. Information processing aimed at understanding the surprising event helps people change their models of the specific situation (and at times the larger world) and move on from prior beliefs and actions.

Thus, it seems that the emotion of surprise has many of the characteristics, effects, and functions which AIT ascribes to fear. Contrary to AIT's emphasis on fear, it is surprise that more consistently results from unexpected events (Reisenzein et al., 2019; Roseman et al., 1996), reduces reliance on existing beliefs and action patterns, prompts a search for new understanding, and facilitates revision of plans and behaviors (e.g., Loewenstein, 2019). It is surprise which, from the moment of its onset, opens individuals and groups to new information (e.g., Reisenzein et al., 2019), reflective deliberation (Johnston et al., 2015), learning (e.g., Brod et al., 2018), and persuasion (e.g., Petty et al., 2001).

Although the emotion of surprise has received little attention from political psychologists (Gadarian and Brader, 2023)—likely because its place has been occupied by fear—a careful reading of the literature shows its influence and importance. Surprising political events, such as the September 11, 2001 attacks, or the 2016 electoral defeat of Hillary Clinton by Donald Trump, can lead to dramatic disruptions of extant beliefs, actions, and plans, initiating immediate and sometimes prolonged information search, analysis, and consideration of changes in traditional practices and standard operating procedures (see e.g., Kennedy et al., 2018; Wirtz, 2006).

How then should we understand fear? Differentially characteristic responses of fear are shown in Figure 1 and some were discussed above. Unlike surprise, fear focuses especially on thoughts about threat or danger. The widened eyes and flared nostrils of the characteristic fear expression increase intake of both visual and olfactory information about threats that can help locate their sources (Lee and Anderson, 2018; Susskind et al., 2008). That is, the increased vigilance that is part of the fear syndrome particularly involves a search for threats. Unlike surprise, the primary emotivational goal in fear is to get to safety, prevent a potential danger from actually occurring. Thus, inducing fear leads individuals and groups to take actions to remove a danger or remove the self from danger (Gadarian and Brader, 2023), whether the danger involves contracting a deadly virus (Harper et al., 2021), falling victim to a terrorist attack (Gadarian, 2010), or incurring an electoral defeat (Valentino et al., 2018).

Note that according to the Emotion System Theory, the influences of the behavioral and emotivational components of an emotion are distinct and complementary. The behavioral component consists of situation-keyed action readinesses and tendencies (Frijda, 1986), such as stilling behavior in surprise (Camras et al., 2002), and freezing, running, or defensive fighting in fear (Blanchard, 2023). Recognizing the role of the behavioral component incorporates the traditional view of emotions as involving relatively short-term impulsive action (see e.g., Cannon, 1939; Eben et al., 2020) in which felt urgency is the hallmark of emotion (Frijda, 1986, 2010).

The emotivational component reflects a newer view of emotions as including flexible instrumental behavior aimed at attaining emotion-specific goals. The term “emotivational” (Roseman, 1984, 2011; Fischer and Roseman, 2007) was introduced to distinguish goals that are part of an emotion from other (“motivational”) goals (such as hunger, sexual drive, or need for achievement), that are not emotion components, but can, when events are consistent or inconsistent with them, contribute to eliciting emotions (e.g., Lazarus, 1991; Scherer, 2001). As with other goals, there may be an infinite number of ways that an emotivational goal can be instrumentally pursued, and potentially over a long time frame. For example, to understand a surprising electoral defeat, one could interview campaign strategists, examine survey findings, establish commissions of inquiry, etc. (e.g., Masket, 2020; Sides et al., 2017). To seek safety when afraid of contracting a deadly virus, one could wear masks, keep from close contact with others, or vote for a candidate—from one's own party or the opposing party—who seems most likely to take needed measures to protect the public (Lebow, 2024; Shino and Smith, 2021).

The emotivational component is proposed to have a greater influence on emotional behavior when there is time to weigh the consequences of alternative actions. The faster that motive-relevant events are changing, and the larger and more important those changes are, the more intense a resulting emotion is likely to be, and the more that control over behavior is likely to shift from the flexibility of emotivational goal pursuit to the more established action readinesses and tendencies of the behavioral component (Roseman, 2008, 2011). Action tendencies in an emotion's behavioral component tend to be responses that evolution or experience have indicated are likely to attain an emotion's emotivational goal across situations. For example, pausing behavior and looking around and listening, are evolution-shaped ways of seeking understanding of surprising events (Reisenzein et al., 2019). The behaviors of freezing, flight, and physical defensive fighting are evolved ways of reducing danger (Mobbs et al., 2015).

Thus, as long as there is sufficient time to reflect (e.g., when danger is not too imminent and fear not too intense), reflective deliberation can indeed be engendered by fear, as AIT proposes—with a focus on increasing safety (e.g., Lerner and Keltner, 2001). Reflective deliberation can also be engendered by hope—with a focus on making a desirable event happen (as when hope motivates a consideration of actions that can be taken to address climate change; Feldman and Hart, 2018). Or by anger—with a focus on compelling a change in the target's behavior (e.g., when an offended political leader considers how best to get revenge, so that offenses will not be repeated; Arnsdorf et al., 2023; Scheff, 2019).

Behaviors when one feels intensely afraid are not usually calmly considered and deliberatively chosen. Mobbs et al. (2015) describe in detail how, as a threat becomes more imminent, attention is narrowed and behavior options are increasingly constrained. If the danger moves from merely potential to actually occurring and a “danger threshold” is breached, then species-typical defensive responses of freezing, fleeing, or fighting may be elicited (p. 7). Blanchard et al. (2001) find human analogs to these behaviors that were initially observed in rats. LeDoux and Daw (2018), who explicitly allow for “choices” and instrumental defensive behaviors in what corresponds to fear, list nonconscious and conscious deliberation as only two of six processes that influence action in their taxonomy of defensive behavior. Indeed, “it is suggested that slow and computationally laborious deliberation is best suited to situations requiring prevention and avoidance when the agent is fairly safe” (p. 273).

As reviewed by Redlawsk and Mattes (2022): Jepson and Chaiken (1990) found that fear reduced participants' systematic and elaborative processing of persuasive messages; Keinan (1987) found that threats reduced consideration of alternative answers to test questions; and Cheung-Blunden and Ju (2016) found that anxiety impaired recall of information about cyberattacks. Based on this and related work, Redlawsk and Mattes (2022, p. 144) conclude that “Taken together, these studies mostly question the link between anxiety and information search.”

Thus, the unique connection that AIT posits between the emotion of fear and “reflective deliberation” (MacKuen et al., 2010; Marcus, 2023) can be challenged. Open, relatively unbiased information search and information processing is more characteristic of surprise than of fear. Consistent with this view, Johnston et al. (2015) found that, in contrast to AIT predictions, expectancy-disconfirming emotions (including enthusiasm felt toward presidential candidates from the opposing party and anger toward candidates from the party with which voters identified) increased reflective deliberation and reduced the impact of partisanship on voting in presidential elections from 1980 to 2004, while anxiety felt toward outparty candidates increased partisan voting.

4 How can emotions be measured?

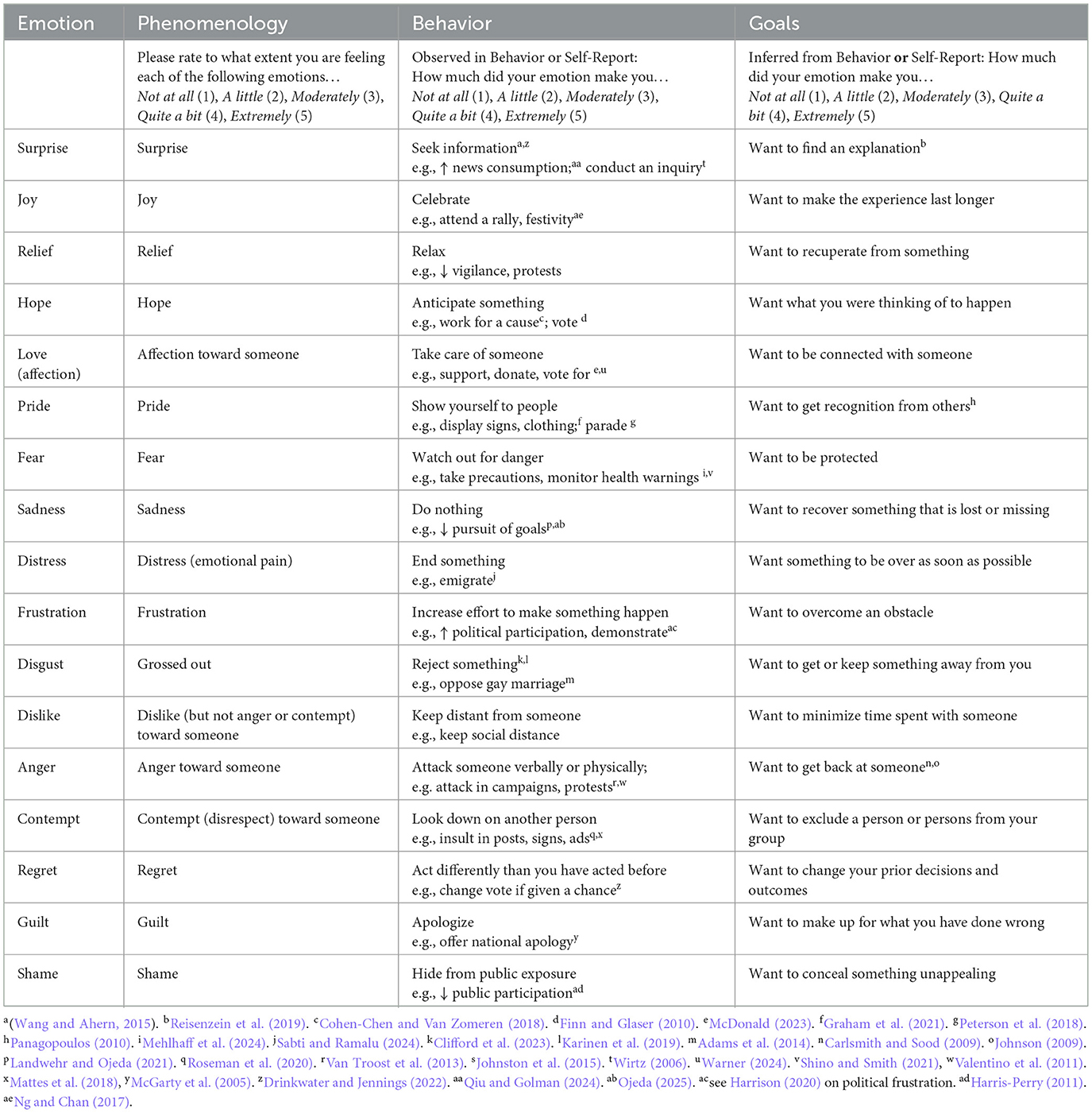

Multicomponent theories (e.g., Kleinginna and Kleinginna, 1981; Izard, 2007; Scherer, 2005), including the Emotion System Theory, offer multiple ways to measure emotions. Insofar as the taxonomy in Figure 1 differentiates emotions that are distinct from each other in typical phenomenology, expressions, behaviors, and goals, each of those response types can be employed in emotion measurement. For example, Table 2 provides for researchers three ways in which each of the EST emotions could be measured (i.e., by emotion phenomenology, behaviors, or goals).

Table 2. Three ways to measure EST emotions, with political examples (examples not to be included in the measures).

To date, most research in political science as well as psychology depends on self-reports (phenomenology) to measure emotions. Examples include the ANES feeling thermometers and affect batteries (American National Election Studies, 2021), the Differential Emotions Scale (Izard et al., 1974), and the revised PANAS-X (Watson and Clark, 1994). Although these measures rely on verbal labels of emotions, reports of body feelings could also be employed, as evidence suggests that these are universal (Volynets et al., 2020).

The measurement of emotivational goals (what individuals or groups want when experiencing an emotion) are similarly most readily accessible through self-report, though goals could also be inferred from patterns of action over time (see Frijda et al., 1989). For example, anger might be inferred from a political leader's repeated attempts to get back at those perceived to have treated him unfairly or humiliated him (Breeze, 2020; Zlotnik, 2003).

Another approach is measuring emotions by the words that people use, as in the speeches of political leaders (Matsumoto et al., 2013). Indeed, researchers have developed dictionaries to code emotions from political communications (e.g., Boyd et al., 2022; Kahn et al., 2007). For example, contempt can be inferred from the belittling insults and exclusionary rhetoric in a leader's tweets and speeches (Ali, 2019; Quealy, 2021). Sentiment analysis of social media posts has been employed to assess positive or negative reactions of the public during a political campaign (Ceron et al., 2015).

Emotions can also be measured physiologically. There is now evidence that at least some of the emotions in Figure 1, such as surprise, happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and disgust, consistently differ from others in brain physiology (see, e.g., Engen and Singer, 2013; Friedman and Thayer, 2024; Harris and Fiske, 2006; Saarimäki et al., 2016), and/or peripheral responses such as heart rate and blood pressure variables (e.g., Kreibig, 2010, 2014; Lench et al., 2011; Stemmler, 2010); but see also Behnke et al. (2022), Lang (2014), and Quigley and Barrett (2014).

Expressions, especially facial muscle movements, have been widely used to measure emotions. Facial expressions have been used to assess the emotions of political leaders (Matsumoto et al., 2014) and candidates in debates (Rodríguez-Fuertes et al., 2022) as well as the emotions of debate audiences (Fridkin et al., 2021).

Accuracy in measurement is complicated by the conceptualization of emotions as syndromes of response (Averill, 1980) in which the presence of particular syndrome constituents may not be essential every time the emotion is present. For example, Reisenzein et al. (2019) report that the characteristic facial expression of surprise is present in only 10%−30% of tested situations in which participants report feeling surprise, and there are also low correlations between other felt emotions and their expressions. It seems clear that people don't make a facial expression each time they feel an emotion; and people may also simulate expressions, more or less well, in the absence of actually feeling an emotion, as in smiles shown by people who are not feeling happy (Ekman and Friesen, 1982). However, there is cross-cultural agreement far beyond chance in the emotion-specific facial, vocal, and postural responses people make when they do express surprise, happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and other emotions (e.g., Cordaro et al., 2018; Coulson, 2004; Elfenbein et al., 2007; Sauter et al., 2015; Shiota, 2024; Volynets et al., 2020), and in the specific emotions inferred from those expressions (e.g., Elfenbein and Ambady, 2002); for a cautionary view, see Sauter and Russell, 2024).

When measuring emotions (e.g., employing Table 2) it is important to remember that the same emotion may be manifest in different responses in different situations, as discussed above (cf. Barrett, 2009), and different emotions manifest in similar responses (Tomkins, 1962). In both cases, combining the multiple response components characterizing a given emotion in Figure 1 may allow researchers to triangulate on a person's actual emotion state (the more characteristic components that are present, the more likely it is that the corresponding emotion is occurring). Obtaining evidence on the emotivational component—the main goal(s) being pursued at a particular time—would be especially helpful in identifying the emotion(s) occurring at that time and predicting likely responses. For example, if a demographic group is choosing which party to vote for in order to avert an undesirable outcome (a protection goal, such as avoiding erosion of group members' economic prospects) that they've been warning could occur (a vigilance behavior, as in watching out for signs of inflation), then they are likely being influenced by fear. Feeling fear could lead them to defect from their traditional party, or to stick with it, depending on which they think would better achieve protection. If instead a group is voting against a candidate or party (a political attack behavior) to get back at them for some perceived harm (a revenge goal), then that group is likely being influenced by anger. Feeling anger could also lead to defecting from or sticking with their historically affiliated party, depending on who is blamed for the perceived harm, and whether defection or its opposite is perceived as more effective at forcing a change in the target's actions (cf. Bol and Verthé, 2019). Thus, the Emotion System Theory's multicomponent definition, and its specification of characteristic responses distinguishing one emotion from another, offer multiple ways to operationalize emotions that can satisfy Marcus' (2023) measurement criterion.

5 Testable causal claims: what are the causes and effects of emotions?

Consistent with its identification of only three principal emotions, AIT posits just three fundamental appraisals that elicit these responses: an appraisal of failure…success underlies the emotion of enthusiasm, familiarity…novelty/uncertainty underlies fear, and norm compliance…norm violation underlies anger.1

In the Emotion System Theory, particular emotions are held to be elicited by a combination of appraisals, which interact to determine which emotion or emotions will result. Since their first modern incarnation, all prominent appraisal theories (e.g., Arnold, 1960; Lazarus, 1991; Roseman, 2013; Scherer, 2009; Smith and Kirby, 2011) agree that particular emotions are elicited by combinations of appraisals.

In Figure 1, emotion-eliciting appraisals are found by moving outward from each emotion to its borders around the chart. For example, it is hypothesized that hope is elicited by appraisals that (a) an outcome is consistent with a person's motives (goals or preferences) and (b) uncertain. Fear results from appraisals that (a) an outcome is inconsistent with a person's motives, and (b) uncertain, when (c) the person feeling the emotion perceives that they have relatively low control potential. Anger results from appraisals that (a) an outcome is inconsistent with a person's motives, and (b) caused by another person or persons, when (c) the person feeling the emotion perceives relatively high control potential and (d) the situation is appraised as an instrumental problem (rather than an intrinsic problem). Where Figure 1 shows more than one appraisal value for a particular emotion, this indicates that the emotion can be felt regardless of the value on that appraisal. For example, surprise can be felt in response to unexpected events whether they are consistent or inconsistent with a person's motives.

The Emotion System Theory includes analogs to AIT's appraisals, but with differences in conceptualization, the number of appraisals identified, and the testable causal claims made.

First, EST's appraisal of motive-inconsistency…motive-consistency is similar to AIT's dimension of failure…success. But whereas AIT focuses this appraisal on “reward-seeking actions” (Marcus, 2023), the Emotion System Theory maintains that virtually anything can be appraised as wanted or unwanted by a person or a group (e.g., success or failure in obtaining something rewarding, such as candidate's electoral victory, or in reducing something aversive, such as violent crime). And whereas in AIT, this appraisal is held to influence “levels of enthusiasm” (Marcus, 2023), in the Emotion System Theory, the motive-inconsistent…motive consistent appraisal contributes to distinguishing all negative emotions from all positive emotions.

Indeed, most theories of emotions in psychology (in contrast to AIT) recognize a distinction between groups of hedonically negative and hedonically positive emotions (e.g., Arnold, 1960; Ekman, 2003; Fontaine et al., 2013; Izard, 2007; Lazarus, 1991; Ortony et al., 2022; Russell, 2003; Smith and Kirby, 2011; Tomkins, 1962, 1963; Wundt, 1902). Empirically, this is supported by data from numerous studies which find emotions or their component responses differentiated, in similarity or co-occurrence data, into negative vs. positive emotion groups (e.g., Abelson et al., 1982; Cacioppo et al., 2004; Gillioz et al., 2016), with this distinction, and its underlying appraisal, typically the factor accounting for the largest share of variance.

Second, the Emotion System Theory's appraisal distinguishing certain vs. uncertain outcomes is similar but not identical to the familiar…novel/uncertain dimension which in AIT determines “levels of fear.” Marcus (2023) sometimes also conceptualizes the high end of this dimension as “the novel and the unexpected” (p. 4). However, it is questionable whether novelty, uncertainty, and unexpectedness are synonymous, and the Emotion System Theory distinguishes among these three perceptions, according them different roles in the causation of emotions. Uncertainty (as opposed to certainty) is proposed as contributing to the elicitation of fear (as in AIT), but also of hope, in combination with other appraisals (Figure 1). As discussed above, in contrast to AIT, unexpectedness is proposed to elicit surprise, and this is empirically supported by multiple carefully conducted studies (reviewed by Reisenzein et al., 2019).

Novelty is not shown in Figure 1 because it is not proposed to distinguish one emotion from another. Rather, the Emotion System Theory cites motive-relevant change as affecting all emotions (Roseman, 2008). If there is no perception or change of relevance to motives in a situation, then no emotion would be felt. Frijda (2007) states this clearly and provides evidence for the “Law of Change”: emotions are elicited by changes in favorable or unfavorable conditions, rather than by the mere presence of those conditions; and greater change produces more intense emotions.

Third, the Emotion System Theory proposes control potential—one's perceived ability to do something about a motive-inconsistent outcome—as a crucial contributor to anger, whereas AIT proposes norm violation (cf. Scherer, 2001). Consistent with AIT, research findings have supported the link between anger and appraisals of being unjustly or unfairly treated (e.g., Averill, 1982; Kuppens et al., 2003; Tong, 2010). An earlier version of the Emotion System Theory assigned this role to an appraisal of “legitimacy” (whether a negative or a positive outcome was deserved; Roseman, 1984). But empirical results (reported in Roseman, 1991) found that ratings of deservingness failed to distinguish distancing emotions such as distress and sorrow (sadness) from attack emotions such as anger, as had been predicted. These findings, along with other empirical results and theoretical considerations, led to reconceptualizing this appraisal as low vs. high control potential (Roseman et al., 1996).

Why prefer control potential over norm compliance as a determinant of emotions such as anger? For one thing, appraisals of legitimacy or norm violation seem too cognitively complex to account for the appearance of anger-related responses in animals (e.g., Blanchard and Blanchard, 2003; Panksepp, 2004) or in four-month-old infants (Lewis et al., 1990). In contrast, appraisals of control potential (or “efficacy,” as it is often studied) are comparatively simple, requiring no understanding of social norms or deservingness. For example, Lewis et al. (1990) found that the infants showed anger-related facial expressions after they'd been trained to be able to control a desirable event, and then had that contingency extinguished. Osgood et al. (1957) established that perceptions of “potency” (from weak to strong) are universal in judging any object, person, or group. The Semantic Differential scale measuring the dimensions of evaluation, potency, and activity has been used, for example, in studies of how people perceive political parties (Petrenko et al., 1995), illegal immigrants (Short and Magaña, 2002), and nations (Smith et al., 1990). If one individual or group is strong relative to another, then they have the potential to control or do something about actions or outcomes the latter causes.

Moreover, a number of empirical findings support the connection between control potential and anger. For example, data relevant to the J-curve theory of revolutions (Davies, 1962) indicate that protests and rebellions tend to occur when a sudden downturn in outcomes follows a period of improvement (which may suggest that change, and thus some control, is possible). Two studies by Lemay et al. (2012) found that appraisals of control were significantly correlated with the intensity of felt anger. When viewing photographs of the September 11 attacks, Americans' perceived group efficacy predicted their feeling of anger (Cheung-Blunden and Blunden, 2008). A measure of “internal efficacy” (believing you are able to understand political events) predicted feeling angry at both Bill Clinton and George Bush in the 1992 presidential election (Valentino et al., 2009). Tausch and Becker (2013) found that students' perceived group efficacy in preventing tuition increases predicted the intensity of their felt anger.

Appraisals of norm violation and control potential are often correlated. One way to understand this is to see norm violation as a distal determinant, which often affects anger through the proximal influence of control potential (Roseman, 2018). In a highly cited publication, French and Raven (1959) proposed that having justice on one's side confers what they called “legitimate power.” Having justice on one's side helps to put a person into a position of relative strength: confronting those who have inflicted harm with evidence that they've behaved unjustly (violating norms) may get them to agree to alter their behavior. In addition, other individuals or groups, perceiving injustices, may support an injured party in compelling an offender to change behavior. In contrast, if one deserves a negative event, one has less potential to influence the harm-doer or recruit support from others.

Lerner (2015) describes how people develop the belief that they will, most of the time, get what they deserve, and presents much evidence for the prevalence of such “just world” beliefs. The widespread conviction that wrongs will ultimately be righted shows that encountering injustice can promote a sense of control potential. In the political domain, Huddy (2013) concludes that the perceived strength of one's group “includes a sense of moral strength” (p. 756; cf. Mackie et al., 2000).

Systematicity II: Why are these appraisals crucial causes of the emotions in the Emotion System? In addition to empirical support, the Emotion System Theory offers functional explanations for the role of each appraisal in eliciting emotions.

The perception of unexpectedness indicates that one's current understanding is inadequate in some respect, and therefore behavior based on that understanding may be inappropriate. It is consistent with this view that unexpectedness functions as the elicitor of surprise, which seeks information that enables revision of mental models and behavior (as when Israelis sought to understand the unexpected October 7 Hamas attacks and considered changes in their beliefs and behaviors; Hitman, 2024).

An appraisal of motive-consistency flexibly assesses current adaptive value. If something is consistent with one's current motives (goals and preferences), then eliciting one or more positive emotions, which function to get more of it, can maximize its benefits. If something is motive-inconsistent, then eliciting one or more negative emotions, which function to get less of it, can minimize harm. For example, if the benefits of the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program are appraised to exceed its costs, positive emotions such as hope or pride would tend to increase the likelihood of its continued implementation; if the costs are seen as higher, negative emotions such as fear or anger would tend to decrease that likelihood (Tollen, 2024).

According to the Emotion System Theory, having an appraisal of whether a situation involves increasing and decreasing reward-seeking vs. punishment-avoiding motives allows the prioritization of coping with more urgent concerns, consistent with findings that negative events have greater impact than positive events (Baumeister et al., 2001). For example, as shown in Figure 1, prolonged heat waves or market crashes would give rise to distress (when they occur) and relief (when they abate) and more urgent behavioral changes; whereas runs of pleasant weather and market rallies would elicit joy when (when they occur) and sadness (when they subside), and comparatively less urgent behavioral effects.

The Emotion System Theory conceptualizes hope and fear as “proactive” emotions (preparing for action), influenced by appraisals of uncertainty about whether potentially motive-consistent (or motive-inconsistent) outcomes will actually occur. In contrast, joy, relief, sadness, and distress are seen as “reactive” emotions, coping with motive-inconsistent or motive-consistent events appraised as certain to occur (including outcomes that are occurring now or have already taken place). Functionally, if an event is uncertain, it is prudent to prepare but perhaps not yet react as one would ultimately. If the event is certain to occur or already happening, then reacting immediately may be more adaptive. For example, Casas and Williams (2019) reported that images from the Black Lives Matter protests which evoked fear (e.g., images of police violence) were retweeted more than images evoking sadness (e.g., memorials to protesters who died). In this case, images suggesting the possible recurrence of police violence may motivate people to prepare for that eventuality together with retweet recipients, whereas the certainty of a protester's death is comparatively likely to lead to acceptance of the loss (cf. Brader and Marcus, 2013; O'Hara et al., 2023).

When encountering a motive-inconsistent event, it also makes functional sense for appraisals of high vs. low control potential to determine whether to get less of it by reacting with “contending” emotions (Arnold, 1960), such as disgust, anger, and contempt (whose responses aim to change a situation), or “accommodating” emotions, such as distress, fear, and interpersonal dislike (whose responses increase distance between the self and the elicitor). If an individual's or group's control potential is low, attempts to push for change would likely fail. But if control potential is high, there may be a chance of succeeding, and a motive-inconsistent outcome may not have to be accepted. For example, Klandermans et al. (2008) report that immigrants who perceived themselves as victims of discrimination felt angry if they also appraised themselves as efficacious, but fear in the absence of perceived efficacy. Although having justice on one's side typically confers some power, if an individual or group has low control potential, then attacking or trying to compel the behavior of others—even if those others are violating norms—may invite strong opposition and damaging counterattacks. Facing immoral but overwhelmingly powerful authorities tends to elicit emotions such as fear or sadness that sap anger (e.g., Burnette et al., 2019; Garg and Lerner, 2013).

This is an important functional reason why control potential (as EST proposes), rather than norm violation (as in AIT) is a crucial proximal determinant of anger, with its characteristic confrontation and attack responses. Although, as noted above, being the victim of some norm violation often confers a sense of control potential, it does not always do so; and when individuals or groups face norm violations but are irremediably weak, responding with anger and attack behaviors may be counterproductive and even fatal. Moreover, people can and do get angry even when there has been no norm violation (Berkowitz, 2010). People also sometimes do get angry when they are powerless, but these instances may involve the belief that some third party (powerful others, perhaps a deity) or people in the future will be able to ultimately change the situation (which provides a sense of control potential). Wortman and Brehm (1975) found evidence that reactance, an anger-related response to being confronted with threats to freedom (Brehm and Brehm, 1981) occurs in response to negative outcomes as long as they are believed to be controllable; but gives way to learned helplessness (a sadness-like response) when control is seen as impossible.

When events are motive-inconsistent and control potential is high, the Emotion System Theory proposes that the type of motive-inconsistency or problem that an individual or group is facing determines whether attack emotions or rejection emotions are likely to be more adaptive. If something is unwanted merely because it blocks a goal (“instrumental problem type”; see Dollard et al., 1939), then emotions which attack the source of the goal blockage (frustration, anger, and guilt) may be able to force a change. But if something or someone is unwanted in itself (see Janoff-Bulman, 1979; Lewis, 1971; Tangney, 1995), because of some intrinsic problem such as inherent offensiveness (Rozin et al., 2016), immorality (Bell, 2013), or incompetence (Hutcherson and Gross, 2011), then such problems may not be modifiable, even if attacked (Fischer and Giner-Sorolla, 2016). In those cases, emotions that reject the unacceptable object, other person, or part of the self, e.g., by removing it in disgust (Plutchik, 1984), excluding them in contempt (Fischer and Roseman, 2007), or withdrawing in shame (Tangney et al., 1996) may be the most effective way to minimize its impact. For example, (Fischer and Roseman 2007) found that low vs. high appraisals of bad character distinguished anger (and short-term attacks) from contempt (and social exclusion).

I discussed above how emotions in the middle third and bottom third of Figure 1 are specialized for dealing with other people and the self, respectively. To be relevant to their elicitors, the responses of emotions felt toward others or the self should be elicited (respectively) by events caused by other people or the self , which they might therefore influence. An example of other-person causation and associated potential influence is when anger among middle-aged German men over perceived displacement by women was felt toward Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose family-work reconciliation policies were seen as a cause of the problem (Mushaben, 2020). Perceiving harm (against Namibians and Jews) as intentionally caused by Germans themselves (self-agency) led German students to support personal apologies to the victims and group reparations (Imhoff et al., 2013).

Thus, it is proposed that the appraisals identified in the Emotion System Theory process basic dimensions of situations that interact to predict which emotions are most likely to be adaptive in the type of situation that a person or group faces.

With regard to empirical evidence, as Parkinson and Manstead (1992) noted, most studies that establish relations between appraisals and emotions have been correlational (e.g., Frijda et al., 1989; Levine, 1996; Roseman et al., 1996; Smith and Ellsworth, 1985), and such correlational research cannot prove causation. Testing claims about causal influence requires experimental research, in which appraisals are manipulated and the resulting emotions measured. A number of hypotheses from the Emotion System Theory have been tested in this way.

Roseman (1991) manipulated five appraisals from an earlier version of EST (Roseman, 1984) in vignettes, and measured the emotions that research participants said the story characters felt. This study encompassed four of the six appraisals and all of the emotions in Figure 1 except surprise. A priori predictions from the theory were tested, and a predicted 5-way interaction was obtained. Results provided overall significant support for theory's hypotheses regarding how particular combinations of appraisals would lead to particular emotions. But as less than half of the emotion-specific predictions for the legitimacy and agency appraisals were significantly supported, the theory was revised (Roseman et al., 1996) to change from legitimacy to control potential as a determinant of attack emotions, and to propose that the emotions in the top third of the chart could result from events regardless of their cause.

Roseman and Evdokas (2004) manipulated appraisals of outcome probability and motivational state. They found that certainty about getting a pleasant taste led to feeling joy; certainty about not getting an unpleasant taste elicited relief; and uncertainty about getting a pleasant taste led to feeling hope (as predicted by Emotion System Theory). Contrary to predictions for the emotions in this study, but in line with Figure 1, uncertainty about avoiding unpleasant tastes led to feeling fear (rather than hope), seemingly because (according to a manipulation check) most participants in this condition thought that they would probably get an unpleasant taste.

Several studies by Reisenzein and his colleagues have manipulated unexpectedness and measured whether surprise results. Unexpectedness has been manipulated by (a) inducing and then disconfirming participants' expectations about the sequence in which stimuli would be shown (Reisenzein et al., 2006), (b) arranging for participants to unexpectedly succeed when working on a task (Stiensmeier-Pelster et al., 1995), and (c) presenting unexpected outcomes of a lottery (Juergensen et al., 2014). Across induction methods, unexpectedness caused participants to be surprised.

The full functional framework of which the Emotion System Theory is a part views emotions as only one of several influences on political phenomena. For example, in addition to supporting Donald Trump because he made them feel the emotion of hope (Hochschild, 2016), some people may have voted for him from a motive to improve their status (see Lamont, 2018), or based on cognitive factors such as ideology (Broockman and Kalla, 2024). When there has been no change in motive-relevant events, political outcomes may be primarily explained by cognitive factors; with small to moderate change, by motivational factors (Roseman, 2008); and with large or rapid change, by emotional factors (e.g., Mutz, 2018). When elicited, emotions add urgency (Frijda, 1986) as well as tendencies for the various responses shown in Figure 1, which would be less likely if only motives or cognitions were producing behavior. However, even if they are differentiable, the effects of cognition, motivation, and emotion on political behavior may co-occur and be intertwined.

Thus far, our consideration of causal claims has focused on hypotheses about causes of emotions. The following discussion of the effects of emotions will be relatively brief because it can be difficult to separate responses that are part of an emotion (already discussed above) from the emotion's effects. This is in part because the Emotion System Theory does not define emotions as purely mental states, or mental states having a neural substrate, which in turn cause behavior. Rather, as discussed above, emotions are conceptualized as having behavioral and motivational components (as in other contemporary emotion theories). The remainder of this section will discuss a number of additional responses of political actors that are associated with emotions, without resolving whether they should ultimately be considered consequences of the emotions or parts of their behavioral and emotivational components.

As shown in Figure 1, the Emotion System Theory predicts that hope will be associated with anticipation and potential approach, and a goal of having hoped-for events occur. According to Reicher and Haslam (2017), attendees at Trump rallies in 2016 were led to anticipate that he would make American great again. For example, after asking rally-goers in Monessen (Pennsylvania) when was the last time that the U.S. bested China in a trade deal, Trump said “I beat China all the time. All the time.” To which the crowd responded “We want Trump! We want Trump!” (p. 32). Phoenix (2020) found that felt hope motivated black people in Detroit to say they'd contact officials about a local political issue, and Finn and Glaser (2010) found that felt hope predicted voting for Barack Obama in 2008 (cf. Redlawsk et al., 2018 on hope for Cruz, Rubio, and Trump).

Fear is hypothesized to be associated with inhibition or flight, and to prepare people to move away from or to stop moving toward something. For example, Lerner and Keltner (2001) found that fear inhibits risk-taking. Valentino et al. (2018) found that showing survey participants the face of a woman expressing fear (in order to elicit that emotion) reduced the extent to which hostile sexism predicted voting for Donald Trump (thus, fear inhibited participants' sexism-related behavior).

Anger is hypothesized to involve a tendency to verbal or physical aggression, and a goal of compelling other people to alter their behavior. In a study by Sadler et al. (2005), anger after seeing videos of the September 11 attacks predicted Americans' ratings of the acceptability of verbally confronting a Muslim person, leaving a threatening message on a Muslim's answering machine, and defacing a mosque. Vasilopoulos et al. (2019) found that anger after the 2015 Paris terror attacks predicted voting for the far right in France (an Emotion System perspective would interpret this as representing support for aggression by the anti-immigrant National Front party). Tausch et al. (2011) found that anger predicted people's willingness to act “to change British foreign policy toward Muslim countries,” as well as support for violence “to stop Western interference in Muslim countries.”

Thus, there is some evidence that hope, fear, and anger cause political behavior in line with Emotion System Theory predictions. With the exception of the Valentino et al. (2018) study, each of these findings comes from correlational research. To firmly establish causal relationships, more experimental research will be needed.

6 Falsifiability: has the theory been empirically tested against alternatives?

Consistent with Marcus' (2023) criteria, hypotheses from the Emotion System Theory have been tested against a number of alternatives, and revised based on results of this research.

Roseman et al. (1990) tested predictions from the 1984 version of the Emotion System Theory against predictions from the competing appraisal theories of Arnold (1960) and Scherer (1988). Participants recalled experiences of all the emotions in Figure 1 except contempt, and rated measures of eight appraisals. Results supported Emotion System Theory predictions for motive-consistency, appetitive vs. aversive motivational state, and agency, but suggested that appraisals of ability to cope with an event (Arnold, 1960) rather than power (Osgood et al., 1957; Roseman, 1984) distinguished emotions that accommodate to negative outcomes (such as sadness) from emotions that contend with them (such as anger). There was no support for the prediction that extreme uncertainty caused surprise (Roseman, 1984).

Roseman et al. (1996) tested theory revisions based on these and other findings. Participants recalled experiences of particular emotions and rated a larger set of appraisals. Results showed that unexpectedness (Izard, 1977)—rather than novelty (Scherer, 1984), unfamiliarity (Scherer, 1988), or uncertainty (Roseman, 1984)—was associated with surprise (in agreement with later findings from Reisenzein's lab, discussed above). Appraisals of who caused an event (Kemper, 1978; Roseman, 1984; Weiner, 1985), more than appraisals of who was responsible (Lazarus and Smith, 1988), distinguished emotions felt toward other people (e.g., love and anger) and the self (e.g., pride and shame).

Contending emotions were not consistently distinguished from accommodating emotions by appraisals of one's power (Kemper, 1978; Roseman, 1984), or the potency of the eliciting stimulus (Osgood et al., 1975), or the extent to which eliciting stimulus was controllable by the person feeling the emotion (Frijda, 1986; cf. Bandura, 1977). Only the appraisal of whether there was “something I could do about” (as opposed to “nothing I could do about”) an event significantly did so. This led the hypothesis about the role of control potential, as discussed above and now shown in Figure 1.

The attack emotions in Figure 1 were not distinguished from the exclusion emotions by appraisals of legitimacy (Ausubel, 1955; Izard, 1991). Instead, an item measuring whether the emotion-eliciting event was or was not an intrinsic problem (revealing “the basic nature of someone or something”) distinguished contempt from anger, and shame from guilt, in both experiences recalled by participants (though it only differentiated disgust from frustration in one of two experiences).

Research has also evaluated aspects of the definition of emotion proposed by the Emotion System Theory. Several studies have addressed the question of whether emotions should be conceptualized as discrete, with multiple states differing in multiple properties (e.g., Marcus et al., 2019; Roseman, 1984) or dimensional, either unidimensional (positive…negative; Lodge and Taber, 2013), or two dimensional (positive…negative and low…high arousal; e.g., Russell, 1980, 2003). For example, differences in multiple response components have been found among 10 negative emotions (Roseman et al., 1994b) as well as five positive emotions and surprise (Roseman et al., 1994a, 2013). In a meta-analysis of 687 studies with over 49,000 participants, Lench et al. (2011) found greater support for discrete than dimensional theories, with differences in behavior, experience, and physiology among happiness, sadness, anxiety, and anger. In the political science literature, Huddy et al. (2007) found support for the discrete perspective in distinguishing anger from anxiety (see also Marcus, 2023), and Redlawsk (2023) reviews evidence for distinguishing contempt and disgust.

Research has also tested hypothesized responses in the Emotion System Theory against hypotheses from other theories. For example, Roseman et al. (1994a) examined whether action tendencies in hope involved preparation for action or rather actual approach behavior (e.g., Mowrer, 1960). Participants differentially said they felt like “planning for the future” rather than moving toward something, consistent with the view that hope more often prepares for (rather than initiates) action. Hope thus seems more conditional and future oriented than enthusiasm, as the latter is conceptualized in AIT (Gadarian and Brader, 2023).

Ongoing studies in our lab are continuing to attempt to replicate prior findings and test alternative hypotheses (e.g., Roseman et al., 2018; Steele et al., 2024).

7 Parallel processing: are multiple emotions and their elicitors processed simultaneously?

Marcus (2023) maintains that the appraisals which cause emotional responses should be processed continuously in parallel, and the Emotion System Theory shares this view. The appraisals around the borders of Figure 1 are hypothesized to combine as shown to elicit each of the emotions (empirical support was discussed above). Functionally, it would seem that multiple appraisals must be able to be processed together in order to allow a situation-appropriate emotion to be generated. For example, if an event is appraised as motive-inconsistent without appraising control potential, it is impossible to know whether it would be more adaptive to accommodate to it (e.g., feel fear and prepare to avoid it) or contend with it (e.g., feel anger and prepare to attack it). Coping adaptively with enemy soldiers on the battlefield, or an autocrat's demands, or a rival candidate's invitation to debate, provide examples that require processing both of these appraisals.

Some work of emotion theorists and researchers may seem to suggest that only one emotion, with a distinctive response profile or neural signature, can be experienced at a time. This may be a holdover from theories that conceptualize emotions as emergency responses (Cannon, 1939), if this implies that only one overall response pattern (e.g., fight or flight) can exist at a given time. If emotions have evolved to cope with crises and time-limited opportunities, perhaps all the resources of the brain and body must be mobilized at once, leaving no room for extraneous processes.

Empirically, Ekman (2003) reports that he has seen rapidly changing emotions more often than the once-anticipated emotion “blends” (Ekman et al., 1972). This could reflect a focus on emotional facial expressions, as it is hard to see how one could simultaneously turn the corners of the lips up when smiling in joy while turning them down in sadness, or raise the brows in fear while lowering them in anger. The same might be said of emotional behaviors: How can a person move both toward and away, approach and avoid, or accommodate and contend at the same time?

Yet as Marcus (2023) correctly observes, research participants often report that they are experiencing multiple emotions (e.g., Marcus et al., 2017; Neuman et al., 2018; Smith and Ellsworth, 1985; Watson and Clark, 1992). Plutchik (1984) explicitly built his theory to include combinations of “primary” emotions, even though each primary represented a distinctive pattern of adaptive behavior. For example, awe was held to be a combination of fear and surprise; disappointment a combination of surprise and sadness; and contempt a combination of anger and disgust.

It is understandable that the specification of which appraisal combinations elicit which emotions (as in Figure 1, or Table 5.4 in Scherer, 2001) could lead a reader to assume that only one emotion can occur at a given time. But if multiple appraisals can be made simultaneously, this need not be the case. For example, Larsen and McGraw (2014) maintained that “bittersweet” events (such as graduating from college) could simultaneously elicit both happiness and sadness, insofar as such events have both positive (successfully completing a degree) and negative (leaving good friends behind) aspects.

Indeed, couldn't a U.S. Senator feel both afraid of and angry at a powerful and vengeful president (and even feel both emotions about his vengefulness)? And couldn't that combination lead to attacking him but cautiously? Don't hope and fear often co-occur, as in “risk assessment” behavior that involves a combination of approach and avoidance (e.g., Blanchard et al., 2011; Lopes, 1987)?