- School of Law, The University of Juba, Juba, South Sudan

Pursuant to the 2018 Agreement, South Sudan is set to go to the polls in December, 2026, marking the world’s youngest country’s first ever democratic election since independence. Using both qualitative and quantitative analyses, this article evaluates the country’s institutional readiness for this transformative exercise as well as examines, more broadly, the historicity of democracy, having regard to the timeliness of transplanting democracy in South Sudan and the country’s fragile socio-politico-economic structures. The article finds that South Sudan’s low GDP per capita, low literacy rate, heavy dependence on oil revenues, lack of vibrant middle class and civil society organizations, inability to sustain institutions of democracy as well as its post-conflict state fragility, renders it unable to attain liberal democracy. To arrive at this conclusion, the article appraises, a priori, the relationship between a nation’s level of economic development and democracy, having regard to the empirical findings that non-democratic countries that solely rely on natural resources for their economic development, rather than on economic growth berthed at the pier of capitalist ingenuity, tend to retard their transition to liberal democracy. It follows that, in order to appreciate (a) whether South Sudan’s current socio-economic and political climate mirrors the models of developing countries that have successfully transitioned into liberal democracies;(b) whether the upcoming elections could usher in the country’s era of sustainable transition to liberal democracy; or (c) whether such elections are purely a veneer of democracy; the article systematically analyzes the country’s current socio-economic and political conditions vis-à-vis its potential to leapfrog to liberal democracy and, therefore, achieve democratic immortality. In light of these material realities in South Sudan as well as the importance of balancing the inherent trade-off between the imperatives of nationbuilding and the ‘dark sides’ of democracy, the article concludes that the efforts to adopt democracy, at this stage, could only leave South Sudan deeply entangled in illiberal democracy-at least in the short run.

1 Introduction

1.1 The country’s background

South Sudan, a nation torn between solidarity and fragmentation among its diverse political and organic composites, is the world’s youngest member of the Society of Sovereign Nations (SSNs), having split with its northern counterpart in the Old Sudan to proclaim independence in 2011. For decades in the lead-up to South Sudan’s independence, the two geographical antipodes of the then Africa’s largest country by landmass, had been in torrid confrontations with each other, first from 1955 to 1972, and second from 1983 to 2005.

In 2005, however, an agreement between the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A), largely based in the then Southern Sudan, and the National Islamic Front (NIF) Government, based in Khartoum, granted the people of Southern Sudan the right to determine, in a referendum, whether they would settle for a united Old Sudan or plump for an independent state (United Nations, 2005). The results of the ensuing referendum vote, held on January 9, 2011, confirmed the people of Southern Sudan’s long-held aspirations for independence, at 98.83% in favor (Abbass, 2023). This transformative political event birthed the world’s youngest country on July 9, 2011.

Among its lofty national ideals during the liberation struggle, from 1983 to 2005, the SPLM/A grappled to establish the model of a united, secular democratic New Sudan, pursuant to which there would be unequivocal separation between state and religion (Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, 1983). However, considering that the NIF would not countenance the SPLM/A’s celestial creed respecting the separation of state and religion as well as its insistence that the Islamic orientation was antithetical and, therefore, diametrically opposed to secularism, the country would ultimately split into South Sudan and the Sudan for the predominantly Christian south and Islamic north, respectively (Olowu, 2011).

Nevertheless, although South Sudan’s independence was greeted with commensurate fanfare, euphoria, and flamboyance, especially domestically, the country would, at full tilt, descend into a brutal civil conflict in 2013, partly due to zealous power struggle within the ruling SPLM and partly due to historical rancor and antagonisms among political leaders who have held positions of influence within the party but have also sharply differed with one another over the decades. The ensuing political violence claimed thousands of human lives, wreaked havoc on economic and political structures, polarized the country on natural and political cleavages and shattered social cohesion among South Sudan’s diverse composites (Krause, 2019; Checchi, 2023).

On September 12, 2018, however, the region cajoled the Government and several rebel groups to sign a peace agreement, known as the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCISS), in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The R-ARCISS was initially slated to last for 36 months, from the establishment of the Transitional Government (TG) on February 22, 2020 (IGAD, 2018). However, the Transitional Period (TP) has since been extended twice, arguably, on account of non-implementation of some key provisions of the R-ARCIS (Vitaliano, 2024). In their last extension in 2024, however, the signatories agreed to extend the TP by two more years, from February 22, 2025, to February 22, 2027, with the view to conducting democratic elections towards the end of the TP, specifically on December 26, 2026 (Vitaliano, ibid). This paradigm shift is clearly coextensive with the people of South Sudan’s historical aspirations for a free, liberal and secular democratic country.

1.2 Research questions and objectives

Is South Sudan ready, willing and able to transition to liberal democracy, considering the country’s low level of economic development; low literacy rate; absence of potent middle class; lack of vibrant civil society organizations; post-conflict state fragility; lack of financial capacity to sustain institutions of democracy; and, more importantly, the need for balancing the inherent trade-off between the imperatives of nationbuilding and the ‘dark sides’ of democracy?

Based on these multifaceted questions as well as on quantitative and qualitative data, this article examines whether the country’s 2026 elections could enhance the establishment of a robust and sustainable political convention and, thus, indissolubly transition the country into a free and liberal democracy or whether such elections could merely leave the country deeply entangled in illiberal democracy—the cosmetic and ceremonial rituals by which authoritarian governments often seek to ostensibly purchase political legitimacy by going to the polls on the day of elections, only to confirm the reign of the incumbents.

This study’s findings are important not only for academics but also for South Sudan’s policymakers, particularly as regards the intricate nexus between liberal democracy and economic development.

1.3 The conceptual framework: a summary

The historicity of liberal democracy is not as old as often espoused in pop culture. Even in the West, where academics and practitioners often arrogate to themselves the ingenuity of democratic experiment, liberal democracy is largely a novelty. It is in this sense that there is not a single country that can pride itself on being a100-year old democracy. Indeed, by “1900s, not a single country had what we would today consider a democracy: a government created by elections in which every adult citizen would vote” (Zakaria, 2007, p. 13). In fact, as recently as 1830, Great Brain “barely allowed 2 percent of its population to vote….” (ibid, p. 20). Literature suggests that most Western countries only became full-fledged democracies in the 1940s, having then given credence to the universal adult suffrage. The last Western countries to embrace liberal democracy were Spain, Greece and Portugal, all in the 1970s (ibid, p. 68).

Whereas this may be surprising to many an observer, the rationale is predicated on the inextricable relationship between the level of a country’s economic development and its transition to liberal democracy (Mohammadi et al., 2023). Furthermore, whereas there is no consensus as to the direction of this relationship, considering that some empirical findings suggest that both democracy and economic development reciprocally influence each other (Madsen et al., 2015), most empirical findings point to a unidirectional influence: economic development is a condition precedent for liberal democratic culture (Tang, 2008).

The article also strives to accentuate the ‘dark sides’ of democracy in the context of South Sudan, considering the country’s virtual lack of financial and institutional readiness to withstand the deleterious effects that organically arise from disorderliness of democratic dissensus.

Nevertheless, South Sudan’s determination to transition to democratic governance is not negotiable. This contention is plausible, since democracy is, indisputably, coterminous with the way of life in the contemporary world. What was once a peculiar political concept and practice by a handful of countries in North America and Western Europe has now become the gold standard for governance-the conventional standard recognized and cherished by almost all members of the SSNs and corporate entities. Democracy has, thus, utterly discredited alternative forms of government, having positioned itself as the sole “source of political legitimacy” (Zakaria, 2007, p. 13). So influential is the allure of the democratic creed that even authoritarian leaders, who frequently gaslight their way into power, tend to justify their reign by invoking democratic values, making democracy the most preferable instrument for rising through socio-political ranks and by which many political leaders legitimately-or perceivably so-arrogate to themselves public authority, irrespective of their prior socio-economic ranks. This makes democracy inherently transformative-being able to rupture traditional aristocracy and rearrange socio-economic hierarchies through meritocracy (Pickering et al., 2022). This, in turn, enables democracy to beget a novel set of vicissitudes that inherently transform or deform societies-socially, culturally and politically.

Despite the preeminence and traction that democracy has garnered over the decades, there are ‘dark sides’ to this political experiment. Democracy, for instance, tends to gravitate towards or engender political disorder, terror and, indeed, violence due to the nefarious conduct of states and non-state actors alike (Hier, 2008). With respect to violence in particular, Fareed Zakaria notes that:

The democratization of violence is one of the fundamental-and terrifying-features of the world today. For centuries, the state has had a monopoly over the legitimate use of force in human societies. This inequality of power between the state and citizens created order and was part of the glue that held modern civilization together (Zakaria, 2007, p. 16).

Besides its tendency to propel individuals with moral blemish to the top, democracy may give rise to its own malaises, such as the tyranny of numbers or autocracy of the masses (Guinier, 1994, De Tocqueville, 2002). This observation discloses two major sources of democracy’s abuses: “If the first source of abuses in a democratic system comes from elected autocrats, the second comes from the people themselves” (Zakaria, 2007, p. 105).

So considered, a comprehensive examination of the ‘dark sides’ of democracy presents an imperative discourse for the post-conflict South Sudanese state, which yearns to transition to liberal democracy. The limitations that are organic to the democratic tradition must, therefore, be highlighted, having regard to their adverse consequences that cut across diverse spheres of societal life. Such consequences are sometimes not only irreversible but are also terrifying. Without highlighting these deficiencies, South Sudan may inadvertently fall victim to the elusive pursuit of the Holy Grail: democracy.

Pivotal to the analytical approach of this article is the linkage between a country’s level of economic development and liberal democracy or democratic immortality. For any materially disadvantaged country, such as South Sudan, the bridle path to liberal democracy or effort to consolidate democratic gains proves “to be the most difficult challenge” (Zakaria, 2007, p. 69). Indeed, if one inspects the success stories of recent decades in Western Europe as well as the trail blazed by countries in Southeast Asia and other developing countries that have successfully transitioned into liberal democracies, it is evident that these countries became democratic only after attaining high per capita incomes (Madison, 2001; Rowen, 1997). Thus, whereas it may be difficult to predict with an exactitude as to when a given country may leapfrog to liberal democracy, the most important indicator is the high per capita income (Fayad and Hoeffler, 2012). The latter must emanate from duly earned wealth: wealth berthed at the pier of the capitalist ingenuity, not solely from natural resource endowments such as oil and/or minerals (Sachs and Warner, 2001). Once authoritarian tendencies are almost eliminated and governance based on democratic principles has become an irresistible reality at all levels of leadership, it is plausible to contend that democracy has become the means by which citizens and political actors alike define themselves. At this point, a country is said to have achieved democratic immortality.

1.4 Methodology

The causal relationship between economic development and democracy has sparked academic curiosity for decades. It is against this backdrop that this study relies on both empirical and theoretical literature, particularly the works of scholars such as Seymour Lipset, Adam Przeworski and Fernando Limongi, Fareed Zakaria and Hossein Mohammadi, among other scholars whose critical perspectives provide the analytical framework for this paper.

The study, therefore, relies on a copious amount of data using both qualitative and quantitative approaches.

Qualitatively, the paper relies on secondary sources such as online databases; books; and journal articles published over the decades on the intricate relationship between economic development and democratic immortality. Other pertinent secondary sources include government reports and publications of international and multilateral organizations on a wide range of issues in and about South Sudan. In this connection, the paper examines primary sources such as South Sudan’s peace agreement documents and data from workshops on good governance and democracy in South Sudan.

Quantitatively, the paper relies on empirical findings in relation to the threshold of economic development needed to propel a country to liberal democracy. In this context, the paper mechanically converts the numerical data in the original empirical findings into 2024 values, having regard to inflation. For instance, to convert 2007 prices into 2024 prices in USD, the article uses the US consumer price indices (CPI) for 2007 and 2024, since the 2025 prices were, at the time of this writing, barely average yet. The conversion methodology is illustrated below (US CPI Data, 2025).

Step 1: According to the CPI data:

the average CPI for 2007 was 207.3.

the average CPI for 2024 was 313.689.

Step 2: 2007 price = 2007 CPI.

2024 Price = 2024 CPI.

2024 Price = (2007 Price × 2024 CPI)/2007 CPI.

Step 3: Using the above formula, the article converts USD 1,500 in 2007 to its 2024 equivalent value as follows: 1,500 × 313.689/207.3 = $2,269.819 ≈ $2,270 in 2024 prices. The other values shown in Section 3, were converted into 2024 prices using the same procedure.

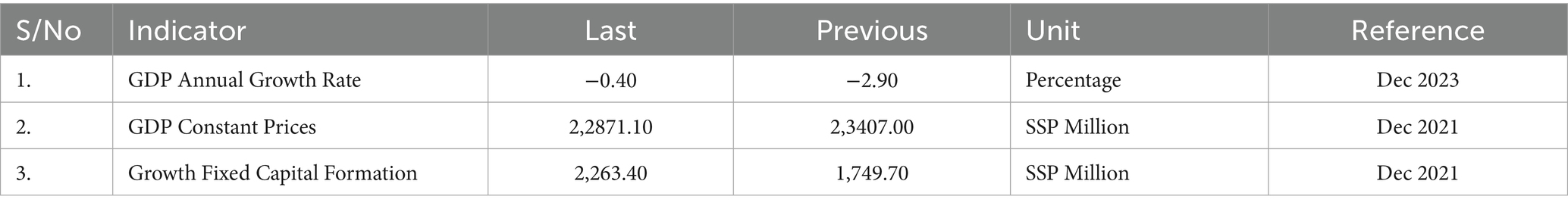

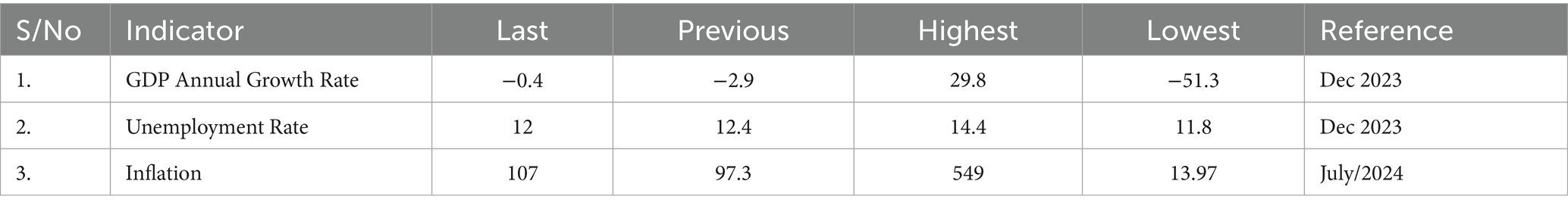

The data in Tables 1–3 in Section 4, are indicators used to explain South Sudan’s GDP evolution as well as economic and human development over the years indicated. They are, therefore, indicia for measuring South Sudan’s level of economic development.

Table 1. South Sudan indicators and the country’s GDP evolution over the years (Trading Economics, 2025a, 2025c, 2025d).

Table 2. South Sudan’s GDP growth (Trading Economics, 2025a, 2025c, 2025d).

Table 3. South Sudan indicators in percentage (Trading Economics, 2025e).

Sources excluded from the study are (a) South Sudan’s development reports published over the past 10 years, and (b) newspaper opinions and commentaries as well as media reports that are not grounded in empirical findings, or sources whose origins are unverifiable. This exclusion enhances not only the relevancy and credibility of the study but also the currency of the data. Finally, the data analysis has been used to structure the paper into several thematic areas shown in the discussion below.

1.5 The structure and organization of the article

Section 2 examines the concept, practice, historicity and impact of democracy as a form of government that enjoys currency in the contemporary world. It then highlights the significance of both liberal and illiberal variants of democracy as well as underscores the essence of democratic immortality. Section 3 examines the inextricable nexus between a country’s level of economic development and democratic immortality. Section 4 applies the concept and practice of democracy to the context of South Sudan to accentuate the timeliness of transplanting the democratic model in South Sudan. Finally, Section 5 synthesizes the data by way of conclusion.

2 Democracy

Etymologically, the term “democracy” originated from two ancient Greek words namely, “demos” which means “people” and “kratus” which means “rule” or “strength.” Combined, the word ‘democracy’ simply means “people’s rule.” Once anglicized in the 18th century, the term took on a life of its own. Today, ‘democracy’ translates into the “government of the people for the people and by the people (Wiltse, 1986, p. 6; Current, 1855, p. 307).

In its pioneering1 American conceptualization, Abraham Lincoln’s recharacterization of democracy, during his Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863, is both enduring and pivotal. Lincoln viewed democracy as a system in which governance, leadership, laws, policies and all other commitments by the state are undertaken directly or indirectly in consultations with the ‘citizens (Zakaria, ibid, pp. 32–33). This view highlights the notion that a democratic government is elected to exercise legitimate authority “over all the people, for all the people, by all the people” (Herndon and Welk, 1892, p. 65).

Since then, democratic ideas have continued to receive moral purchase and universal assent, with democracy now being expropriated in various forms and manifestations by almost all members of the SSNs and corporate societies. For most people, democracy is not just about going to the polls to elect leaders. Elected leaders, themselves, are and must be accountable to their citizens, right from the day of elections all through to the next election cycle. This practice stands in contradistinction to the one that prevailed-even in the West-prior to 1945 during which several autocratic rulers were chosen via free and fair elections (Zakaria, ibid, p. 19).

In its essential formulation, democracy presupposes a catalogue of guarantees such as freedoms of speech, conscience, association as well as a minimum requirement of economic, social and cultural rights, committed to, in a party’s manifesto. These requirements, nevertheless, are rudimentary, being insufficient in terms of capturing the essence of contemporary democratic practice. Accordingly, it would be inordinate to label a country as a ‘democracy,’ simply because it has satisfied the minimum requirements of democratic procedures. To do so would render the word ‘democracy’ ‘meaningless’ (Zakaria, ibid, p. 19). Democracy must, thus, be understood in a substantive sense, not just as a procedural process. Yet, for much of the world, including Africa especially, democracy is practically truncated-having been trifled to going to the polls on the day of elections but not much else.

To succinctly conceptualize the evolving standards of democratic practice globally, the following subsections underline two variants of democracy namely, ‘liberal democracy’ and ‘illiberal democracy.’ Whereas Daniel Bell is credited with originating the two variants (Bell et al., 1995) these expressions were largely popularized by Fareed Zakaria in 1997 (Zakaria, 1997).

2.1 Liberal democracy

‘Liberal democracy,’ connotes a political system marked by open, free and fair elections, the rule of law, robust protection of basic civil liberties, including free speech, conscience, assembly and property rights. Liberal democracy, as such, incorporates aspects of constitutional liberalism which “seeks to protect an individual’s autonomy and dignity against coercion, whatever the source-state, church, or society” (Zakaria, ibid, p. 19).

‘Constitutional liberalism,’ thus, marries two descriptors namely, ‘liberal’ and ‘constitutional.’ “It is ‘liberal’ because it draws on [a] philosophical strain…that emphasizes individual liberty. It is ‘constitutional’ because it places the rule of law at the center of politics” (Zakaria, ibid, p. 19). This distinction is illuminating. What distinguishes democracy as a practice from democracy as a procedure is not just free and fair elections but, more importantly, the infusion of democracy with ideas of constitutional liberalism. Once liberal ideas are alloyed with those of democracy, what obtains is liberal democracy.

The distinction between constitutional liberalism and democracy hinges on the scope of governmental power. Constitutional liberalism operates to limit the reach of public power whereas democracy seeks to maximize the use of that power. Left to its own device, ergo, an elected government may exercise democracy adversely, much to the detriment of the governed. Accordingly, it is critical to circumscribe the reach of democratic reign by constraining the propensity for elected governments to suppose that they have an unfettered authority over the exercise of sovereign power, often beyond the limits prescribed by law. It stands to reason that constitutional liberalism is designed to mitigate state excesses, including, especially, the state intrusion in the exclusive domain of individual liberties (Croce, 2024). It delineates the role of democratic government; promotes equality under the law; separates state from religion and empowers neutral arbiters-the courts-to adjudicate over matters between citizens and the state (Tsesis, 2013). A government that operates consistently with these requirements is referred to as a liberal democracy (Bollen, 1993). Other concepts used interchangeably with liberal democracy are “democratic immortality,” and “sustainable democracy.”

However, whereas the phrase democratic immortality, as discussed in Section 2.3, is used synonymously with ‘liberal or sustainable democracy,’ democratic immorality is more expansive than liberal or sustainable democracy.

2.2 Illiberal democracy

The truncated form of liberal democracy is referred to as ‘illiberal democracy.’ This variant presupposes that whereas a government may claim legitimate authority through free and fair elections or similar modalities as prescribed by law or political conventions, it willfully remains oblivious to the limits constitutionally imposed upon its authority. These limits are aimed at protecting the basic rights and freedoms of the governed. Illiberal democracies, therefore, merely place a premium on electoral procedures but practically operate in wanton disregard for the application of substantive democratic rules and policies. Their modus operandi is not at variance with the one deployed by authoritarian regimes.

An illiberal democracy does no more than going to the polls on the day of elections only to revert to authoritarianism the minute the election results confirm the triumph of incumbents. This is why an illiberal democracy is sometimes referred to as an ‘elected autocracy,’ tending to ensure that democratic rights and freedoms are only secure in principle but are wantonly violated in almost every aspect of political and economic life of society. Fareed Zakaria, however, hastens to add that frustrations with illiberal democracies should not justify the abandonment of democratic ideals (Zakaria, 2007, p. 100).

In some cases, elections in illiberal democracies are not free and fair, even if the optics suggest the semblance of popular participation. They have, therefore, not been shown to be an effective path to democratic immortality. Hence, a non-democratic country aspiring to adopt a democratic system via illiberal democracy is more likely to retard its transition to liberal democracy (Nyyssönen et al., 2020) from which democratic immortality flows.

2.3 Democratic immortality

Whereas democracy, as considered in the foregoing, refers to a system of government characterized by free elections, protection of civil liberties, the rule of law, popular participation in the political process as well as accountable government, a non-institutionalized democratic transition may, however, gradually lose its strength or degenerate overtime, depending on who holds and controls the levers of public power. That is because, whereas a particular political leader may, by their own initiative-not by institutional design-advance democratic ideals during his or her tenure, such a system is still susceptible to collapse if public institutions are not independent and strong enough to withstand authoritarian tendencies. Consequently, such a democracy may crumble once a leader who is not democratic takes over the control of the levers of political and economic power. However, if public institutions are strong enough to sustain the weight of endogenous and exogenous pressures or tendencies for authoritarian leadership, regardless of who is in charge, such a country may achieve democratic immortality.

Nevertheless, it is worth emphasizing that, as considered in Section 4 below, democratic immortality is achievable at this point where a nation has reached a high threshold of economic development (Przeworski and Limongi, 1997, pp. 155–183). Indeed, whereas other features of a democratic tradition include but are not limited to a cogent and an independent middle class, a high level of literacy, vibrant civil society organizations, independent institutions (such as the executive, judiciary and legislature), freedom of press, popular participation, the rule of law, strict adherence to political conventions as well as adoption of liberal political culture that outlives generations, it is worth reiterating that high per capital income is the prerequisite for the implementation of democratic resilience in non-democratic countries. To attain democratic immortality, therefore, a liberal democracy must preserve and sustain these democratic values, practices and structures. As a country strives to perfect its democratic practice perpetually, it becomes immune from any relapse into authoritarian rule. At this stage, a democracy is deemed to have captivated and customized a set of non-derogatory standards and liberal democratic values by which citizens and political actors alike define and conduct themselves.

In this paper, therefore, democratic immortality refers to the ability of a newly emergent democratic country to maintain a strong democratic tradition, due to the resilience of its institutions, notwithstanding the weight of endogenous and exogenous pressures of relapsing into authoritarianism.

3 The relationship between economic development and liberal democracy

3.1 Economic development versus economic growth

Economic development maybe described as a quantitative and qualitative measure of improvement in the socio-economic wellbeing of the population in a specific country. These include the introduction of new goods and services; expansion of productive capabilities of citizens and existing products; increasing the size of the markets for such goods/services and labor force; surge in housing demands; and advancement in the country’s industrial capabilities and physical infrastructure (Hill, 2023).

Whereas the concept of ‘economic development’ is often used conterminously with that of ‘economic growth,’ these notions are intelligibly distinguishable. ‘Economic growth’ is strictly measured in terms of quantitative changes in a country’s production output per a given year, whereas ‘economic development’ measures not only the structural transformations of society’s productive capabilities but also the quality of life for all citizens (Flammang, 1979). Properly understood, thus, economic growth is a subset of economic development.

Since this section and the article, more broadly, strive to accentuate the relationship between economic development and South Sudan’s transition to democracy, both terms are used conterminously.

3.2 Theoretical and empirical perspectives on development-democracy nexus

The relationship between economic development and liberal democracy has, for decades, been a phenomenon of empirical and theoretical inquisitiveness. Since economic development is a multidimensional phenomenon that depends on a variety of factors and conditions, an in-depth comprehension of this linkage is peremptory (Mohammadi, ibid) especially for policymakers, literature suggests that, since 17th century, capitalism has operated to produce its own favored form of government-the bourgeoisie democracy-which inherently seeks to establish a government that jealously protects private property and liberty of contracts as well as enhances individual ingenuity and the rule of law (Marenco, 2022).

In this vein, several empirical and theoretical studies have sought to establish the logical linkage between economic development and democratic immortality. Accordingly, a country is more likely to transition into a liberal democracy if or when it has achieved a certain level of per capita income. This indicates that when a materially disadvantaged country adopts democracy prior to achieving the necessary threshold of per capita income, it tends to relapse into authoritarianism. This general experience, however, has exceptions. For instance, countries such as India and South Africa became liberal democracies when they were still more materially disadvantaged than they currently are. However, these countries are what they are: exceptions, not the rule.

The corollary to this background is, ‘how does a country’s increase in per capita income induce changes in a political system that favors liberal democracy’? (Mohammadi, ibid, p. 2).

In the quest for the answer to this inquiry, several researchers have, theoretically and empirically, sought to ascertain the validity of the relationship between democratic immortality and economic development for nearly 80 years. Whereas a few empirical findings have concluded that this relationship is not statistically significant, an overwhelming number of findings on the same have concluded that a high level of economic development, by default, induces a country’s transition to liberal democracy (Nayan et al., 2011), not the other way round.

In this connection, the seminal work of Seymour Martin Lipset is instructive (Lipset, 1959; Griffith et al., 1956). Lipset was the first academic to introduce a hypothesis as to the existence of a positive relationship between economic development and liberal democracy in the 1950s. For Lipset, economic growth first, requires the state to invest in the production of goods and services for basic consumption. Second, a vast amount of money is spent on essential needs, including higher education and civil, political, economic and social rights. This, by default, triggers the quest for democracy (Lipset, ibid; Jaunky, 2013).

Accordingly, the more economically advanced a country is, “the greater its chances to sustain democracy” (Lipset, ibid, p. 73). That is because, “as countries develop economically, their societies also develop the strengths, [desire], and skills to sustain liberal democratic governance” (Zakaria, 2007, p. 69). The causal relationship between the two variables flows from the direction of economic growth to democratic transition which, in turn, improves with increasing economic growth and development (Jaunky, ibid).

Over the decades, the Lipset Hypothesis has engendered both academic curiosity and the yearn for its application in public policy, having spanned schools and counter schools of thought, “gathering data, running regressions and checking assumptions. After 40-years of research with some caveats, and qualifications, his fundamental point still holds” (Zakaria, 2007, p. 69).

Another important and, certainly, the most comprehensive study regarding the relationship between economic development and transition to liberal democracy was conducted between 1950s and 2000s by Adam Przeworski and Fernando Limongi. This and many studies looked at the level of economic development and democratic immortality in each of the 135 countries they had investigated. They concluded that in every country that was democratic in practice and with a per capita income of USD 2,270 (in 2024 dollars), the regime, on average, had a life span of just 8 years. Similarly, when a country’s per capita income was between USD 2,270 and USD 4,540, a purportedly democratic regime was found to survive, on average, for about 18 years. If a country had over USD 9,000 per capita income, its democratic tradition was sustainable, with the result that the odds of a democratic regime dying being 1 in 500 years (Przeworski and Limongi, 1997). Once nations are wealthy, their democratic traditions are immune from relapsing into authoritarianism: ‘they become immortal.’ This was evident in the case of the 32 democratic regimes studied, each with an average per capita income of USD 13,620 and all had a combined total of 736 years. None of them, however, died. The same study found that, of the 69 democratic regimes that were considered poor, having an average per capita income of less than USD 4,540, 39 of them failed, a death rate of 56% (Przeworski and Limongi, ibid).

These findings led Przeworski and Limongi to conclude that countries are successful when they adopt democracy after attaining a per capita income of between USD 4,540 and USD 9,000 (ibid).

Other scholars have similarly sought to verify the validity of these findings, with bold conclusions that the necessary threshold of economic development for a sustainable transition to a democratic culture holds true throughout the history. Fareed Zakaria, for instance, postulates that the per capita GDP of many European countries in 1820 when they took practical steps towards widening democratic franchise, was USD 2,570. This per capita income grew to USD 3,330 in 1870, and USD 7,260 by 1913, prior to WW I struck (Zakaria, 2007, pp. 69–75). As a result of their economic development, “many of these countries became securely liberal democracies only after 1945, having then achieved approximately USD 9,000 per capita GDP” (Przeworski and Limongi, ibid, p. 155).

It stands to reason that even in Europe as a whole, this correlation historically holds. It is edifying to note that “no one factor tells the whole story, but given the sheer number of countries being examined, on different continents, with vastly different cultures, and at different historical phases, it is remarkable that one simple explanation-per capita GDP-can explain so much” (Zakaria, 2007, pp. 70–72).

Aptly put, thus, a country’s high per capita income affords citizens with economic empowerment and immunizes them from state capture, having the ability to create a bourgeoisie which, owing to its economic strength becomes independent from the government. In these circumstances, two things ensue. First, the prevailing economic situation licenses key segments of society, such as private businesses, middle class workers and broader working class, to gain political and economic power, independent of the state. Second, once aware of the fact that these key segments of society have influence, the state is compelled to embark on bona fide bargains with these segments. The state circumspectly begins to concede certain liberties and freedoms to the rising bourgeoisie and becomes “less rapacious and capricious” (Zakaria, 2007, pp. 71–72) in the exercise of public authority. In this sense, the state is more rule oriented and, indeed, responsive to the needs of the larger society. In this process, “an independent judiciary, respect for law and individual rights, are necessary for a stable democratic system and for securing property and legal contracts” (Mohammadi et al., ibid, p. 2). This inadvertently eventuates in the liberalizing conditions that translate into democratic gains. It is in this connection that Minxin Pei notes with respect to Taiwan that the rapid economic gains in Taiwan, in 1980s/90s, had unintentionally:

liberalizing consequences that the ruling regime had not fully anticipated. With economic take off, Taiwan displayed the features common to all growing capitalist societies; per capita income rose, and a differentiated urban sector-including labor, a professional middle class, and a business entrepreneurial class-came into being. The business class was remarkable for its independence. Although individual enterprises were small and unorganized, they were beyond capture of the party-state (Pei, 1997, pp. 39–59).

Economic development, thus, “causes structural changes in the relative strength of various classes in society, thereby, increasing the probability of the spread of democracy” (Tang, ibid, p. 122). That is, due to the fact that as societies develop, the level of education and consciousness among the citizenry, equally increases. This prompts the populace to strictly hold their leaders accountable. Political leaders, in turn, become more sensitive to their own conduct by way of self-censoring, in an anticipation of democratic reprisals.

For economic development to induce democratic culture, however, the source of such development must emanate from capitalist growth. It is not just any high per capita income or wealth that engenders liberalizing conditions that, in turn, induce a liberal democratic culture. Rather “it must be earned wealth,” which is closely linked to a variety of factors such as human capital; capital investments and creative innovation (Canuto and Cavallari, 2012).

Indeed, in the past few decades, some countries have grown richer but have, ironically, remained autocratic, as seen, for instance, in Venezuela and most Gulf states, whose wealth comes from natural resources. This suggests that economic development not tethered to the capitalist ingenuity, does not spur democratic culture (Nord, 1995). Seen as such, many Gulf countries have not become democratic. They only use their natural wealth to purchase modernity in the form of new flashy buildings, skyscrapers, mansions and luxurious possessions like cars and televisions, among others. Yet, their citizens remain substantially unexposed to capitalist enterprise. The prime results have been the growth of business and middle classes that remain heavily dependent on their governments. For instance, despite its high per capita income, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia exhibits very low literacy level, standing only at 62% with only 50% of female adults being able to read and write (Zakaria, 2007, pp. 72–74). This means that “if an educated populace or at least a literate one-is a prerequisite for democratic and participatory government, it is one that the oil producing Arab states are still lacking after decades of fabulous wealth” (Zakaria, 2007, p. 74).

In summary, abundant endowments in natural resources tends to undermine both state and political modernization (van der Ploeg, 2010; Brooks and Kurtz, 2016). This proposition has been confirmed by a series of studies conducted for nearly a decade by Jeffrey Sachs and Andrew Warner. Their findings led them to conclude that the richer a country is in natural resources, including agriculture, the slower its economic growth or development (Sachs and Warner, 1995). Accordingly, whereas countries with abundance natural resources have the least economic growth rates, countries with almost no natural resource endowments grow the fastest whereas those with moderate endowment in such resources grow at a rate that falls in between (Sachs and Warner, ibid; Wu et al., 2018).

Empirical findings also suggest that there are variations as regards the relationship between democracy and economic development in developed and developing countries. A series of studies by Hossein Mohammadi and colleagues, for instance, found that:

For OECD countries, real per capita economic growth was mainly affected by previous per capita GDP growth, and the effect of democracy on per capita economic growth was negative. Moreover, the results indicated that in developing countries, democracy alone had not triggered economic growth, and that per capita GDP growth depended on other important structural variables such as social and physical infrastructure (Mohammadi et al., pp. 1–2).

This suggests that “the democracy-growth nexus is not similar across world regions and decades” (Calgarossi et al., 2020; also, Mohammadi et al., ibid., p. 4).

Khodaverdian specifically demonstrates that democracy in Africa does not have effect on per capita income “without improvements in health [adding that], democracy in Africa was pushing these countries into the Malthusian Trap” (Mohammedi et al., ibid, p. 4, see also Khodaverdian, 2022, pp. 1147–1175).

For this reason, a premature transplantation of democracy may ‘retard economic development’ due to the fact that democracy inversely relates to economic growth when democracy proceeds economic development (Mohammadi et al., ibid, p. 4).

Finally, whereas some findings suggest that democracy provides a better platform for a meaningful dialogue through political negotiations or discourses that are necessary to ensure sustainable economic development more recent findings suggest a unidirectional relationship: economic development fosters the adoption of liberal democratic government, at least in the short run (Banik, 2022). These findings slightly contrast with Daron Acemoglu’s findings that democracy induces economic growth by a factor of 20 percent in the long run (Acemoglu et al., 2019).

As evident above, however, most findings support the conclusion that the causal relationship between economic growth and democracy is unidirectional, with causality flowing from the direction of economic growth to democracy in the short run whereas the causality is bidirectional in the long run (Mohammadi et al., ibid, p. 2).

4 Application of the concept and practice of democracy to the context of South Sudan

If the foregoing discussion on the nexus between a high level of economic development and democratization is tenable, then a compelling argument can be made that South Sudan’s transition into a free and liberal democratic society is a tall order. This proposition is supported by a wide range of material realities in South Sudan. Evidently, South Sudan has consistently been ranked as the world’s poorest country. It also ranks among the countries with the lowest credit ratings (Trading Economics, 2025a, 2025b, 2025c, 2025d). These include South Sudan’s low level of literacy; passive civil society organizations; heavy reliance on oil revenues; absence of a vibrant middle class, untenable costs of maintaining institutions of democracy; South Sudan’s post-conflict state fragility; and the delicate balance between the imperatives of nationbuilding and the ‘dark sides’ of democracy. If this contention is within reason and having regard to the findings of a positive correlation between a high level of economic development and democratization, one may well expostulate that South Sudan is simply chasing a mirage of democracy: an entanglement in illiberal democracy. The pertinence of this claim is further considered below.

4.1 Low level of economic development in South Sudan

The foregoing establishes that a high per capita income is a prime catalyst for democratization (Banik, 2022; Mohammadi et al., ibid, p. 2; Tang, 2008). However, as alluded to previously, South Sudan is also ranked as the world’s poorest country. This tag is discernable from several objective findings. For instance, in 2024, South Sudan’s GDP per capita was the world’s lowest, at USD 455.16, down from USD 1071.78 in 2015, which was also lower than what it was between 2008 and 2015, when it stood at USD 1685.89 on average. In fact, in 2010, South Sudan’s GDP per capita reached an all-time high at USD 2302.52, being the highest in the region then (See Tables 1–3 below).

Conventionally, per capita income is calculated by dividing the country’s GDP to the total population (Murry and Nan, 1994).

As well, South Sudan’s poverty index which ranges between 82.3 and 92%, suggesting that between 82.3% and 92% of the country’s total population lives below poverty line, or lives on less than USD 2.15 per day (World Bank, 2024; Radio Tamazuj, 2025; Mercy Corps, 2019). This essentially means that poverty in South Sudan is both extreme and widespread due to a combination of factors including political instability; heavy dependency on limited oil revenues; and the adverse impact of natural disasters such as floods and droughts; resource mismanagement, inadequate state capacity to deliver services; almost non-existent physical infrastructure; low literacy; communal violence and culture that places primacy on family dependency; just to list but a few. Consequently, more than 60% of South Sudan’s population is, arguably, dependent on humanitarian aid (Mercy Corps, ibid; Pape and Finn, 2019).

Holding everything else constant, one may submit that the world’s youngest country can only-at least for now-romanticize the idea of transitioning to liberal democracy. This view is in tandem with the postulation that “the simplest explanation for a new democracy’s success is its economic success, or to be more specific, high per capita income” (Zakaria, 2007, pp. 116, 69) since the causality direction between democracy and democratic immortality flows from economic development to democracy, especially in the short run (Tang, ibid; Nayan et al., ibid). Furthermore, when countries are pressured to adopt democracy while they are economically and institutionally weak, they are simply pushed “into the Malthusian trap” (Mohammadi et al., ibid, p. 4), resulting in abject and widespread poverty in society (Malthus, 1798, p. 61). It is for the same reasons that some scholars have interestingly postulated that, at a certain stage of a country’s economic development, non-democratic regimes may well be more favorable to robust economic growth than a democracy (Mohammadi et al., ibid, p. 4).

The adoption of democracy at this stage is, therefore, unlikely to expedite South Sudan’s transition to liberal democracy nor support robust economic growth.

4.2 Low literacy in South Sudan

Both domestic and external sources establish that South Sudan, at 27%, has the lowest literacy rate in the world, with more than 70% of its population above 15 years of age being illiterate (UNESCO, 2020).

Since literacy and education are critical factors for both economic development and democratization, South Sudan’s lagging literacy suggests a state of stagnation for a viable democratic transition, considering that education inherently predisposes citizens to appreciate their civic duties and responsibilities. It also unlocks the ability of the masses to appreciate the importance of cohesive society; equips them with the skills to resolve conflicts through dialogue and tolerance, and with the ability to treat one another with respect and consideration. These virtues, in turn, foster agitation for democratic values and good governance (Crittenden, 2018).

It follows that since an educated populace is a quintessential aspect of participatory and democratic governance, South Sudan is ill-equipped, both institutionally and economically, for a democratic culture.

4.3 Passive civil society organization in South Sudan

Civil society organizations consist of voluntary institutions and loose set of individual players, acting entirely independently from the government. When the space for civil activism is unconstrained, there is a platform on which to defend and promote individual and group interests; enhance political pluralism; and cherish diversity of thoughts and opinions. In developing countries, the role of civil society organizations in spurring transition to democracy may include an effort to limit and constrain the exercise of public power by controlling the conduct of the operating minds of the state. The synergy derived from this chain of activism operates to expose the conduct of state actors and promote the participation of ordinary people in political processes. Civil society organizations may also design programs for civic education and agitate for reforms with the view to expanding not only the democratic space but also advocating for the concerns of those who have historically been left to fend for themselves on the margins of society, including women, youths, people with disabilities, among others. Finally, civil society organizations play a vital role in monitoring democratic processes such as elections as well as advocate for legislative reforms (Modavanova et al., 2023). In this respect, a post-conflict country, such as South Sudan, needs vibrant-not passive-civil society organizations, to promote economic development and agitate for democracy.

South Sudan, however, currently lacks civil society organizations that are bold enough to put at bay the conduct of the operating minds of the state or promote popular interests. The few that are currently based in Juba are largely passive and have often been accused of acting in cahoots with the government, contrary to the imperatives of their profession’s creed. Where a few voices, such as those in the People’s Coalition for Civic Action (PCCA), have sought to boldly check the government, they have either been subjected to sinuous interments or forced into involuntary exile (NDSC, 2020). This demonstrates that civil society organizations in South Sudan cannot meaningfully pursue sustainable development and democratic goals when they are, visibly, either dependent on the state or have an ineffective platform to advance their goals. This situation is consonant with the submission that democratic transition is almost “an impossible task for countries struggling with poverty and deprivation” (Mohammadi et al., ibid, p. 4), such as South Sudan.

4.4 Overreliance on oil revenues and absence of vibrant middle class in South Sudan

The foregoing highlights the fact that, for a country to enjoy sustainable economic development that potentially spurs democratization, its wealth must not solely come from natural endowments such as oil and mineral reserves. Revenues that come from natural endowments are considered as ‘easy money.’ Nevertheless:

easy money means the government does not need to tax its citizens. When government taxes people, it has to provide benefits in return, beginning with services, accountability and good governance but ending with liberalization and representation…. (Zakaria, 2007, pp. 75–76).

This makes capitalist growth the ideal instrument by which the bourgeoise forges a new form of government, usually a liberal democracy. For a high GDP per capita income to generate economic growth, it must be one berthed at the pier of the capitalist ingenuity (ibid).

In South Sudan, however, one is confronted forthwith, by unavoidable realities that militate against the country’s potential for transitioning to liberal democracy. As of this writing, South Sudan was, on average, producing 180,000 barrels of crude oil a day. For long, oil revenues have accounted for almost 90% of the country’s exports and about 80% of the government’s revenue as well as almost 40% of the country’s GDP (International Crisis Group, 2024; Chol, 2016). This year, 2025, South Sudan appears to have improved in terms of non-oil revenue collection as the South Sudan Revenue Authority (SSRA) has set a target of SSP 1.788 trillion. This value is slated to account for 34% of the FY 2025/2026 Government’s Budget of SSP 5.2 trillion (Madut, 2025). Yet it is worth reiterating that this improvement in non-oil revenue sector is spurred by oil revenues and may, therefore, be elusive if the oil sector’s production continues to dwindle.

Furthermore, South Sudan’s heavy reliance on oil revenues has also induced an alarming and widespread level of resource mismanagement; lack of transparency; influence peddling; avarice, abuse of discretion; and fraudulent schemes with no shred of accountability. The world’s young nation has, in fact, been consistently ranked among the four most corrupt countries in the world (Transparency International, 2023; Transparency Organization, 2023).

Furthermore, the benefits accruing from oil wealth generally and management of oil resources in South Sudan is a monopoly of a few. This wealth rarely trickles down to the hoi polloi who would constitute the bourgeoisie if permitted to meaningfully participate in the country’s economic life. In the absence of the capitalist development in South Sudan, thus, there is no bourgeoisie class. This adversely impacts on sustainable transition to liberal democracy. Consequently, one would be hard-pressed to postulate that the country’s upcoming elections in 2026 could usher in the dawn of sustainable democracy. That is because South Sudan is, nevertheless, institutionally and economically unprepared to tackle the arduous task of managing and mitigating democratic maladies, suggesting that the country has a long and difficult road to democratic immortality.

Moreover, since those who have unjustly enriched themselves with oil wealth in South Sudan are also the ones who run the state, it is unlikely that they would be inclined to favor political liberalization. Doing so potentially plays into the hands of disadvantaged masses who have the latent potency to dispossess the ruling political and economic elites of the tools of the state control. This stands in contradistinction to the situation engendered by a capitalist system in which those with talents, regardless of their prior socio-economic backgrounds, procure their wealth independently. It also confirms, yet again, that unearned wealth can be a curse, not only vis-à-vis economic development but also democracy. In the main, abundance of natural resources “impede the development of modern political institutions, laws and bureaucracies” (Zakaria, 2007, p. 75).

In addition, the business and political elite which monopolizes the management of oil wealth in South Sudan is not only notorious for tax evasion with impunity but is also too insignificant to induce democratic change. Thus, even though this class of domestic elite wallows in opulence, it does not constitute the critical mass needed for sustainable democratic change. This perspective is in line with the contention that for a society to achieve sustainable economic development, the state must be wealthy. Yet, the state can only be wealthy if the wider society is wealthy. This, in turn, enables the government to tax this wealth. For the people to be wealthy, however, laws must be fair and just. If one of these prerequisites is missing, then the dream for a wealthy society and government is elusive. This suggests that massive wealth distribution is necessary to enhance efficiency in both capitalist system and political liberalization (Zakaria, 2007, p. 75).

4.5 South Sudan’s inability to sustain institutions of democracy

Barack Obama once observed that Africa needs not just strong leadership but also strong institutions (Obama, 2009). This statement is in keeping with the notion that strong political leaders and resilient institutions are needed to spur Africa’s economic development and, thus, the transition to democracy (Tshiyoyo, 2015).

Yet, inadequate institutional capacity in the developing world remains a present and pressing challenge. For this reason, institutions that safeguard democratic values must be strengthened to enable Africa to leapfrog to economic development and democratic governance. This requires visionary politics and a great deal of money. A lot of money. Money is essential for implementing various visions associated with building institutions of democracy (Casas-Zamora and Zovatto, 2026).

As well, several objectives relating to democratic institutions can be pursued by effectively regulating political financing, such as making the flow of money more transparent; leveling the political playing field by evening out conditions that militate against fair political competitions; and/or making political parties less vulnerable to the undue monopoly of the ruling elites (Drew, 1983; Sunstein, 1994; Mutch, 1988, pp. xvii, 7–42).

Considering the primacy of money in democratic liberalization and tradition, thus, the enormity of South Sudan’s financial limitations and the necessity for strengthening electoral institutions, such as National Elections Commission, National Bureau of Statistics, and Political Parties’ Council, among others, and having regard to the country’s evident inability to provide adequate financing for their effective operationalization, the world’s newest country is more likely to fall short in respect of shouldering the responsibility of gendering and sustaining democratic institutions. In fact, the country’s widespread level of abject poverty indicates that the wider society, not just its electoral institutions, is yet to develop the capacity to sustain liberal democracy (Drew, 1983; Sunstein, 1994; Mutch, 1988, pp. xvii, 7–42).

4.6 Post-conflict state fragility in South Sudan

In post-conflict societies, such as South Sudan, peacebuilding and nationbuilding are not optional programs. They are quintessential aspects of forging a stable, cohesive and democratic society. However, building a democratic culture in a post-conflict country is a daunting task, in part, due to state fragility.

State fragility refers to the deficiencies in a nation’s ability to discharge its sovereign responsibilities in at least three main areas namely, the state capacity; state authority; and state legitimacy. The concept of state authority refers to a nation’s ability to control political or criminal violence whereas state capacity connotes a nation’s ability to provide basic public goods and services. Finally, state legitimacy refers to a nation’s ability to enjoy popular acceptance or sovereign rule over the population within its sovereign jurisdiction (Saeed, 2020).

State fragility bears serious ramifications on a country’s readiness, or lack thereof, to transition to democracy. Democracy, by its very nature, is contested, chaotic and noisy. That is because the cardinal characteristic of democracy is the political competition of ideas with the view to winning elections. In essence, democracy has the capacity to destroy, not just rupture, a society when it is not methodically phased and cautiously managed. Thus, in the post-conflict South Sudan, the first step in building a democratic culture is to pacify the populations and prioritize building structures of good governance. These structures may exist alongside or outside of democracy. A government that protects the interests of its people (such as fighting corruption and effectively responds to their critical needs) does not necessarily have to be democratic.

Good governance is the process of managing national resources and public affairs with the view to enhancing transparency, accountability, fairness, the rule of law, equity, respect for human rights and state responsibility while mitigating systemic sharp practices and abuse of public power (United Nations, 2025; Weiss, 2000). This does not only promote political legitimacy but also boosts administrative efficiency, having the capacity to unleash productive cooperation between the government and the citizenry (Keping, 2017).

It stands to reason that the project of pacifying a post-conflict society is a call for building institutions of good governance, promoting social cohesion, political resilience and the rule of law, respect for human rights and placing a premium, especially, on egalité without sacrificing liberté. Within the framework of this reasoning is the postulation that “reforming a country’s economics and legal structures before politics is preferrable, if one cannot reform both simultaneously” (Keping, 2017, pp. 91–92). Indeed, when in conflict, premium ought to be placed on the “right to bread” over the right to vote. The “right to bread” approach has come to be known as the “full-belly thesis,” which states that an individual must have a full stomach prior to indulging in political rights such as the right to vote (Howard, 1983; and Nyerere, 1969/70).

In the context of South Sudan, a country viciously torn between solidarity and fragmentation among its natural and political composites due to many decades of conflict and violence, a delicate balance between the imperatives of statebuilding and nationbuilding, on the one hand, and the lofty and historical aspirations of the people of South Sudan for democracy, on the other hand, must be struck. This suggests that a rush to democracy at the expense of building institutions of good governance, strong social and political bonds among various communities and nurturing strong political culture without prioritizing economic development, coupled with the curse of natural resources, may have to be momentarily paused in order to find a more organic way of achieving liberal democratic governance without frustrating the gains of independence, or rupturing social bonds among the country’s composites.

It follows that, for South Sudan, pacifying the masses and creating a culture of self-reliance are not negotiable. They are prerequisites for democratic governance and achieving democratic immortality.

4.7 Balancing the ‘dark sides’ of democracy with imperatives of nationbuilding

Winston Churchill is accredited with having noted that “democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others” (Langworth, 2008). Churchill’s contention underscores the notion that democracy is a system of government that has only come to be accepted, among other alternatives, notwithstanding its imperfections. In fact, concerns about the limitations of democracy led many Western liberal scholars in the 18th century to view democracy with deep suspicions, seeing it as a “force that could undermine liberty” (Langworth, 2008, pp. 100–102).

The same concerns were echoed more recently by Michael Mann (Mann, 2004; Breuilly, 2006) who noted that heated political contestation that inheres in democracy may engender mass political violence. The latter is sometimes deployed as an instrument of state policy (Mithun, 2018). According to Mann, history is replete with political leaders who have either ordered or acquiesced to the liquidation of subsets of human groups to promote ethnic homogeneity (Mann, ibid).

Other scholars concur with these sentiments, pointing to political upheavals in Central Asia and much of Africa where elections have not only paved the way for autocracies but also exacerbated group conflicts. Indeed, in fragile states and transitional democracies, elections may not improve the situation but induce long term underdevelopment or enthrone political leaders bent-on intolerance, vengeance and bigotry. Such leaders can be more destabilizing and pernicious to society than the dictatorships they seek to dislodge (Zakaria, 2007, pp. 100–102). In the context of Africa, some studies have shown that:

although democratic transitions have, in many ways, opened up African politics and brought people liberty, it has also produced a degree of chaos and instability that has actually made corruption and lawlessness worse in many countries (Joseph, 2016; Cooper, 2001; Sklar, 1983).

Along these lines, Chege and Diamond maintain that the African continent has often placed undue emphasis on multiparty politics and democratic elections but has correspondingly neglected the tenets of good governance and liberal constitutionalism. They further claim-and rightly so-that more than anything else, what Africa urgently needs is good governance rather than democracy (Chege, 1995; Diamond, 2007). Others similarly claim that the “rapid moves towards democracy have undermined state authority and produced regional and ethnic challenges to central rule” (Zakaria, 2007, p. 98). For some yet, elections that are not cautiously managed have operated to spur rebellions, coup d’états, and stimulated ethnic based violence against governments that come to power through elections in Africa (Rabushka and Shepsle, 1972). This has led some to infer that the divisive nature of political competitions makes democratic governance infeasible in a “charged political environment of intense ethnic cleavages and preferences” (Rabushka and Shepsle, ibid, pp. 62–92).

In these circumstances, South Sudan’s quest for democracy must be juxtaposed against the imperatives of political stability and nationbuilding. The latter is potentially tenable if South Sudan’s leadership places a premium on promoting institutions of good governance, rather than on an exogenous model of governance-democracy-whose conditions are yet to be practical in the context of South Sudan. This is not to say that democracy must wait. It is rather a proposition for a phased implementation of national priorities. A distorted hierarchy of public needs potentially renders South Sudan more vulnerable, vanishing its lofty aspirations in the cracks of the imperfections of the Holy Grail: democracy.

As of this writing, South Sudan was only 16 months away from the December 2026 elections. Yet, considering the enduring and incorrigible political brinkmanship demonstrated by South Sudan’s political actors, one would be remiss to ignore that some of the presidential candidates who are set to lose elections are predisposed to dispute the elections results. Their practical response may not consist in challenging the results in the Supreme Court but in mobilizing their ethnic bastions to wage mass political violence, eventuating in yet another civil war whose impact may be more deleterious and, obviously, consequential than the state of methodically phased democratic transition.

Furthermore, at the time of this writing, South Sudan’s President, Salva Kiir Mayardit, who also doubled as the Chairperson of the SPLM (the major party in RTGONU), had single-handedly restructured the leadership lineup in the party, having ‘unilaterally’ appointed, through a presidential decree, the youthful Dr. Benjamin Bol Mel as First Deputy Chairperson of the SPLM. This move potentially makes Mr. Bol President Kiir’s successor. With this move, however, President Kiir appears to have exasperated several senior SPLM loyalists who are of the view that not only have they been scorned but have also been willfully ignored, despite their historical contributions to the liberation struggle. Nevertheless, the vast majority of SPLM party members appear to have welcomed this restructuring, not on account of the personalities who have been elevated to these party positions but because the status quo ante was not working. Prior to these changes, the old SPLM hierarchy was based on a trite liberation military seniority, even though such seniority has ceased to be relevant, insofar as the requisite leadership for transforming South Sudan into a modern bureaucratic state is concerned. This suggests that, although many members have reservations as regards these appointments, they also recognize that change, in and of itself, is desirable. It follows that, even if President Kiir’s ‘unilateral’ decree is deemed ultra vires the authority of the SPLM’s Chairperson, being as undemocratic as the old SPLM hierarchy it sought to undo, many still view change in the context of the SPLM as a catalyst for more change.

Whether President Kiir’s move could eventuate in the party’s internal implosion, as some expect, is yet to be seen. From an independent viewpoint, however, there are reasonable grounds to believe that, unless Mr. Bol does something truly extraordinary to further antagonize internal discontent, the optics point to a situation where the SPLM may remain intact. This is because Mr. Bol has several advantages over and above his political rivals, including the authority to oversee the management of public finances in his capacity as Vice President for Economic Cluster and, more importantly, being a close confidante of the President. The latter is predicated on the conviction that many SPLM members are historically deferential to President Kiir, their political differences notwithstanding.

5 Conclusion

Considered in the totality of the foregoing circumstances, some readers may find themselves thrown off the scent of assuming that the object of this article is the repudiation of democracy in South Sudan. Far from it! This article is a clarion call for a phased and methodical management of the world’s youngest country’s transition to democracy with the view to nurturing and consolidating the gains of independence as well as building a strong political culture, one that is similar but not identical to the model seen in countries such as Singapore or Rwanda, not on account of the authoritarian approach of the latter’s current leadership but in spite of it.

In this vein, the article has navigated vast literature on the historicity of democracy and, more broadly, the inextricable nexus between a nation’s level of economic development and democratic immortality.

The article has specifically emphasized that South Sudan has yet to satisfy the necessary and sufficient conditions for democratic immortality. That is because, for a nation to trigger a viable transition to liberal democracy and, ultimately, to democratic immortality, its per capita income must not only be high, but the source of its economic development must also be berthed at the pier of capitalist ingenuity.

The article has further underscored that, elections, by their very nature, are poised on the foundations of political competitions for people’s votes. Yet, in countries that are materially disadvantaged or have fragile institutions, democratic competitions tend to gravitate towards an organization along polarizing lines-ethnic, racial or religious-much to the detriment of national cohesion, pursuit of common national identity and political stability. The article has stressed that the upcoming South Sudan’s first democratic elections may not only leave the country deeply entangled in illiberal democracy, at least in the short run, but also one that could adversely be consequential, including the potential for mass political violence.

In this connection, the article suggests that South Sudan should place primacy on reforming its economic structures, building bureaucratic institutions and placing a premium on promoting enlightened leadership. The latter is necessary for setting the tone, designing the vision and establishing rules and parameters that are necessary for exacting compliance with public policies tailored to building a more cohesive; free and liberal society, enhancing economic development and, ultimately, democracy.

What South Sudan urgently needs is, therefore, good governance, without sacrificing the country’s aspirations for democratic governance. This salient conclusion derives its essence from a myriad of material facts about South Sudan, a nation tagged as the least developed country in the world; has little to no financial capacity to sustain institutions of democracy; does not have a copious and independent middle class; suffers from severe and chronic post-conflict state fragility; is torn between fragmentation and solidarity among its diverse composites and is incapable of sustaining the storm of political pressures emanating from the ‘dark sides’ of democracy.

In summary, the ills of democracy in a fragile and divided society, such as South Sudan, are far worse than those engendered by unelected regimes led by benevolent autocrats. At this point, South Sudan may be willing, but it is neither ready nor able to transition to sustainable or liberal democracy. It must, therefore, first take deliberate and practical steps to creating fertile conditions for democratic tradition. Without these considerations, South Sudan, least arguably, has a long and difficult road to democratic immortality. What obtains suggests that the pursuit of the Holy Grail could only leave the world’s youngest country deeply entangled in illiberal democracy, at least in the short run.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SD: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The author is deeply indebted to Dr. Nhial Kuch Chol, a senior economist at IGC, and Dr. Augustino Ting Mayai, the Managing Director of the South Sudan’s Bureau of Statistics, for their valuable inputs.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The attribution of the contemporary phase of democracy to the US does not discount the contribution of Ancient Greece to the development of the concept. Ancient Greece was, indeed, the seedbed of liberty, political equality and devotion to philosophy, literature and science. The Greek version was, however, short lived, lasting for about 100 years after which it perished, following the Macedonian conquest of Athens in 335 B.C. Nevertheless, it still served as an inspiration and, perhaps the greatest influence on the West, centuries later (For more details, see Zakaria, 2007, pp. 32–33).

References

Abbass, A. S. M. (2023). Post-secession Sudan and South Sudan: a comparative study of economic performance, export diversification, and institutions. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 58, 864–887. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359015166_Postsecession_Sudan_and_South_Sudan_A_Comparative_Study_of_Economic_Performance_Export_Diversification_and_Institutions (retrieved on July 31, 2025).

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., and Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. J. Pol. Administratio Publica 127, 139–160. Available online at: https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/publications/Democracy%20Does%20Cause%20Growth.pdf (retrieved on July 31, 2025).

Banik, D. (2022). Democracy and sustainable development. Anth. Sci. 1, 233–245. doi: 10.1007/s44177-022-00019-z

Bell, D., Brown, D., and Jayasuriya, K. (1995). Towards illiberal democracy in pacific Asia. St. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bollen, K. (1993). Liberal democracy: validity and method factors in cross-national measures. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 37, 1207–1230. doi: 10.2307/2111550

Breuilly, J. (2006). Debate on Michael Mann's the dark sides of democracy: explaining ethnic cleansing. Nations Nationalism 12, 389–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8129.2006.00251.x

Brooks, S., and Kurtz, M. J. (2016). Oil and democracy: endogenous natural resources and the political ‘resource curse’. Int. Organ. 70, 279–311. doi: 10.1017/S0020818316000072

Calgarossi, M., Rossignoli, D., and Maggioni, M. A. (2020). Does democracy cause growth: a meta-analysis (of 2000 regressions). Eur. J. Pol. 61:101824. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2019.101824

Canuto, O., and Cavallari, M. (2012). Natural capital and the resource course, economic premise. The World Bank: Washington, DC.

Casas-Zamora, K., and Zovatto, D. (2026). The cost of democracy: essays on political finance in latin America. Washington DC: International IDEA.

Checchi, F. (2023). Inferring the impact of humanitarian responses on population mortality: methodological problems and proposals. Confl. Heal. 17:16. doi: 10.1186/s13031-023-00516-x

Chol, J. (2016). The reality of petroleum resource curse in South Sudan: can this be avoided? Afr. Rev. 43, 17–50. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45341720 (retrieved on July 31, 2025).

Cooper, R. (2001), The breaking of nations: order and Chaos in the twenty-first century, London: Atlantic Books Cooperation and Development

Crittenden, J. (2018). Civic Education. Stanf. Encycl. Philos. Available online at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/civic-education/ (retrieved on July 31, 2025).

Croce, M. (2024). Democracy: constrained or militant? Carl Schmitt and Karl Loewenstein on what it means to defend the constitution. Intellect. Hist. Rev. 1, 1–20. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382095901_Democracy_constrained_or_militant_Carl_Schmitt_and_Karl_Loewenstein_on_what_it_means_to_defend_the_constitution (retrieved on July 31, 2025).

De Tocqueville, A. (2002). Democracy in America: historical-critical edition, Translation by James T. Schleifer. Philadelphia, PA: Pennsylvania, UP.

Diamond, L. (2007). Developing democracy in Africa: Africa and international imperatives. Cambridge Int’l Rev. of Affairs 14, 191–213.

Fayad, B., and Hoeffler, A. (2012). “Income and Democracy: Lipset's Law Revisited,” IMF Working Paper, Available online at: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12295.pdf (Accessed March 30, 2025).