- Faculty of Health, School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

Introduction: One of the most significant drivers of the public's decision-making is trust. Trust is a critical factor when making decisions in the face of uncertainty and risk. This same principle applies to trust in our social institutions, which is the topic this paper explores. Institutional trust may be especially important for migrant groups whose vulnerabilities are furthered by the decrease in institutional trust. As such, this review aims to investigate the nature and extent of immigrants, migrants, and refugees' institutional trust (and adjacent concepts) in social institutions.

Methods: A scoping review was done using the PRISMA-ScR's guideline and Arksey and O'Malley's framework. A total of 81 articles were selected from four databases following screening, and then data were charted using three extraction tables. Data were organized following 5 main objectives relating to: trust theories and explanations (objective 1), recommendations and solutions targeting different social institutions (objective 2), across population group comparisons (objective 3), defining trust concepts (objective 4), and areas for future research (objective 5).

Results: Findings revealed that many different theories and definitions of institutional trust exist across studies suggesting that institutional trust is a complex and nuanced concept that may vary across different migrant groups, contextual factors, and social institutions of focus. As well, we note the heterogeneity of immigrant groups and how this may relate to the various factors identified as shaping institutional trust. Not a lot of recommendations were presented, and these were mostly community-based. Lastly, research gaps were identified to inform future research and inform efforts and strategies to build institutional trust among migrant groups.

Discussion: These findings, accompanied by other results, demonstrated the significance of trust in migrants when it comes to their successful integration, as well as their health and well-being over time. We emphasize the need for trust interventions at different societal levels, and the need to target both immigrant populations and social institutions. We conclude that establishing trust in one institution will help build trust in other institutions, such as the public health and healthcare system institutions.

1 Introduction

Trust in the context of health is critical for population health. Trust is associated with greater use of health services, acceptance of official health recommendations and behavior change that works in the interest of individual and population health (Meyer et al., 2008; Aboueid et al., 2023; Rădoi and Lupu, 2017). Trust as it relates to health implications, however, goes beyond trust in health officials and healthcare institutions within which they operate. Rather, it extends to the systems that influence and impact the operation of health systems and drive health policy—for example, government, legal and other systems that guide regulation in a given country, state or municipality. Hence, to understand trust as it relates to healthcare, it is important to also investigate the nature of public trust in social institutions more broadly and consider how this trust, or lack of trust, influences decisions that ultimately impact on individual and population health. For example, a recent study from South Korea highlights the crucial impact of institutional trust on health-related behaviors beyond clinical and/or acute care settings, through evidence suggesting that institutional trust (such as trust in government) is positively associated with formal long-term care services use, among older adults in the community (Fong, 2025). Also interesting, are the recent findings that during the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals were willing to overlook their lack of trust in government if the messages government were sharing regarding pandemic countermeasures actually came from public health [see (Herati et al., 2023a)]. In this case, individuals' lack of trust in one institution (i.e., government), did not have a bearing on their trust in other institutions (i.e., Public Health). Instead, public trust in Public Health worked to support their acceptance of recommendations that supported population health. This finding tells us a bit more about how trust can be maintained and support population health in light of trust being lost elsewhere. Better understanding of this interplay between trust in various systems, as well as if or how this works in immigrant populations, would be important to know. This nuanced and contextual information is something we are interested to understand in the context of migrants, immigrants, and refugees and their trust in social institutions.

Institutional trust is integral to the success, sustainability, and wellbeing of societies (Herati et al., 2023b; UN-iLibrary, 2021), and central to the present work. This may be especially important for immigrants, migrants, and refugee groups whose inequities and vulnerabilities are furthered with the decrease in institutional trust (Hermesh et al., 2020; Ike et al., 2023). However, the nature and extent of trust among these populations in the social institutions of their host countries has not been systematically documented. This information is critical if we are to understand the health of these populations as it relates to the actions of social institutions, or the perceptions and experience of immigrants, migrants, and refugee groups. The aim of the present scoping review is to document the extent of the literature on trust in social institutions with the goal of identifying evidence-informed strategies to support the development/maintenance of trust and identify gaps in need of further investigation.

According to the United Nations, a migrant is defined as “any person who is moving or has moved across an international border or within a State away from [their] habitual place of residence, regardless of the person's legal status, whether the movement is voluntary or involuntary, what the causes for the movement are and what the length of the stay is” (United Nations, 2025). For the purpose of this review, we focus on long-term migration (i.e., not individuals relocating for the short term for work/pleasure). In contrast, for the purpose of this review, an immigrant “refers to a person who is, or who has ever been, a landed immigrant or permanent resident” (Statistics Canada, 2016). Lastly, refugees are identified as “people who have fled their countries to escape conflict, violence, or persecution and have sought safety in another country” (The UN Refugee Agency, 2025a).

These groups can be further characterized by how long they have been in the country, as well as defined by either generational status and/or documentation status. For instance, the term newcomer has been used to describe individuals who have been in a host country for <5 years and can be either an immigrant, migrant or refugee [e.g., (NewYouth, 2025)]. Generation status can include first-generation (persons who were born outside Canada), second-generation (persons who were born outside the host country and had at least one parent born outside the host country) and third- or more generation (persons who were born in the host country but both parents born outside of the host country; Statistics Canada, 2021). Documentation status is used to distinguish populations groups seeking protection in a country in which they are not a citizen (e.g., asylum seekers; The UN Refugee Agency, 2025b) and illegal immigrants (individuals who arrive to a country undocumented and/or through illegal means, or individuals who overstay in the host country without official status; Thrift and Kitchin, 2009). We note the above terminology as it is critical to our search of the literature but note that alternative and similarly defined terms have been used across the literature, reflecting the evolution of terminology (e.g., no longer using terms that promote discrimination or stigmatization of certain groups of individuals—such as “illegal aliens”) and changes in migration policies and laws (Washington State Department of Social Health Services, 2025; Kashyap, 2021; Ruz, 2025; Rose, 2021; Governemnt of Canada, 2023a). These different terms are also partially a reflection of the different migration pathways that individuals undergo. For instance, some individuals voluntarily or involuntarily leave their homes due to conflict, violence, or persecution (The UN Refugee Agency, 2025a; European Parliament, 2024), while other individuals may be migrating with hopes of greater financial stability (Government of Canada, 2023b) or due to environmental and climate crisis (European Parliament, 2024).

The noted pathways to a host country, coupled with the unique conditions and contexts that drive the migration, may shape immigrants and migrant's institutional trust and ultimately their health within a host country. For example, literature suggests that newcomers‘ trust may decrease over time (Röder and Mühlau, 2012a) and that migrants are commonly less trusting of the health system of a given country (Savas et al., 2024), which aligns with work suggesting that immigrants tend to use fewer health services than the native population (Sarría-Santamera et al., 2016). This may be caused by skepticism toward public institutions in general, due to legal status and deportation fears (Savas et al., 2024). We further note that the decrease in trust may also be amplified by experiences of exclusion, marginalization, racial discrimination, and violence that may occur pre-, during and post-migration (Savas et al., 2024), which supports the need to understand, not only why and how migrant groups' trust social institutions, but also how it may vary (or not) across different migrant groups and contexts.

Migrant groups are an important group for whom to consider institutional trust, as the number of migrants, immigrants, and refugees has increased substantially over the years. Even though the percentage of people living outside their birth country increases yearly (NewYouth, 2025; Statistics Canada, 2021), the nature and extent of immigrants, migrants, and refugees' trust in social institutions, or why it may be (or not) declining over time, has not been systematically documented despite the critical role of this literature in understanding how we might support the development or maintenance of trust in these growing populations. To fill this gap, the present research aims to investigate the nature and extent of immigrants, migrants and refugees' trust in social institutions, document practice recommendations to support (re)building trust and highlight areas for future research. To meet the aim of the present research, data extracted from articles are organized according to five key objectives: Objective 1 reports on information relating to trust theories and explanations for trust formation or deterioration; Objective 2 reports on any trust recommendations and solutions targeting social institutions as they relate to building trust amongst populations of interest; Objective 3 focuses on comparing population groups across studies; Objective 4 reports on trust definitions and conceptualizations of institutional trust; and Objective 5 reports on identified areas for future research. This knowledge will provide a comprehensive understanding of how trusting relationships between the population groups, and the institutions are formed and how they may be lost, which can then be used to inform health policy and practice aimed at improving the health and wellbeing of migrants, immigrants, and refugees' groups engaging with social institutions of host countries. Our overall goal is to provide knowledge on current challenges and barriers to trust building, as well as efforts that promote institutional trust and consequently promote population health for migrant groups, that can be used by researchers, industry, policymakers, and other important stakeholders, to inform future research, health policy, and practice.

1.1 Conceptual framework

The concept of trust has been a central focus in behavioral health research across many disciplines (Taylor et al., 2023). Accordingly, there is no single definition of trust, despite many forms of trust being described in the literature. Within the present research, we draw on conceptualizations of trust most commonly described in the health context (Taylor et al., 2023) and consider trust to be shaped by perceptions of benefits and risks, uncertainty, credibility, and vulnerability, in consideration of both institutions (e.g., healthcare system) and individual actors (e.g., health care providers; Lewis and Weigert, 1985; Roundtable on Public Interfaces of the Life Sciences, 2015). We also align with the perspective that fundamentally, public trust is shaped by the belief that the trustee is both capable and committed to act in the truster's best interests, and this belief is both individual and context-specific (Lewis and Weigert, 1985).

Within the present work, we specifically focus on institutional trust; that is, the confidence individuals place in institutions (e.g., government, police, healthcare systems), based on their belief or expectation that these institutions act competently, fairly, and in the best interests of those trusting them (Quaranta, 2024). This is distinct from interpersonal trust, social trust, generalized trust, and relational trust (Kaasa and Andriani, 2022; Campos-Castillo et al., 2016; Frederiksen, 2014; You, 2012; Alesina and La Ferrara, 2002): Interpersonal trust can be defined as the trust an individual places on individuals they know personally (e.g., their close friends, family, or family doctor; Jovanović et al., 2023); Social trust (or generalized interpersonal trust) can be defined as a trust in most people broadly across society beyond individuals we know (You, 2012); Generalized trust has be defined as a “general propensity to trust others” (Kaasa and Andriani, 2022), which could include strangers (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2002); and Relational trust describes trust as going beyond an emotional or rational decision, to being the result of both ongoing social interactions over time (i.e., experience) and the context of the particular situation or interaction happening in the moment (Frederiksen, 2014).

Though distinct, relevant to our work are considerations of the relationship between institutional trust and interpersonal trust. For instance, it has been argued that institutional trust is an extension of personal trust, which may occur via socialization between citizens and greater civic engagement (Kaasa and Andriani, 2022). This may also relate to how institutions and the individuals performing duties within them are not separate from one another (Aboueid et al., 2023). Indeed, Giddens argues that in order to trust the medical system, which is a more abstract thing, one must first trust the physician which is the access point representing the medical system (Giddens, 1997). Luhmann, on the other hand, believes the opposite is true and that one must first trust the system in order to trust a representative of the system (Meyer et al., 2008). Despite different theories, which have limitations in their application (Meyer et al., 2008), it is evident that a relationship between institutional trust and interpersonal trust exists.

Trust can be influenced by many factors. For instance, a study investigating predictors of interpersonal trust has found that a history of traumatic experiences, belonging to a group that historically felt discriminated against (i.e., minority groups), being economically unsuccessful in terms of income and education, and living in a racially mixed community and/or in one with a high degree of income disparity, are all factors contributing to low levels of interpersonal trust (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2002). As such, both individual and community characteristics shape interpersonal trust levels (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2002). Individual level factors (e.g., personal experiences and demographic factors) are documented to impact trust in institutions (Wang and Gordon, 2011), as do macro-level factors (e.g., institutional quality and governance; Wang and Gordon, 2011). For example, research has found that factors shaping individuals' generalized trust and trust in local governments include the quality of local services, with local public services perceived as good resulting in higher levels of trust (Camussi and Mancini, 2019). Relatedly, the OECD argue that trust can be built and reinforced from better governance of societies and populations, which requires transparent, fair, inclusive and responsive practices from our governments (OECD, 2017). Further validating these works is research investigating institutional trust during the COVID-19 pandemic, a time of crisis where trust was greatly challenged. A recent study found that government support measures including financial aid and protective policies, contributed toward an increased trust in institutions, which in turn helped increase citizens' satisfaction with democracy (Poma and Pistoresi, 2024).

Additionally, within the present work we consider trust to be a multidimensional concept. A 2023 systematic review documenting the extent of literature investigating trust in social institutions documented dimensions of trust, including competence, integrity, communication, benevolence, fidelity, fairness, global trust, confidentiality, relational comfort, and dependability as recurring when measuring trust levels of individuals in a population (Aboueid et al., 2023). These dimensions are complex and context-specific, with evidence suggesting that there is overlap between these dimensions across different forms of trust. For example, fairness appears to be an important dimension of both social and institutional trust, as supported by the previously mentioned systematic review (Aboueid et al., 2023), and a multilevel analysis conducted in 2012 arguing that fairness can better explain cross-national variations in social trust than ethnic or cultural homogeneity (You, 2012). Building on the discussion of trust, it is important to recognize its close relationship with social capital within the context of our population of interest. Social capital, for many scholars, has been discussed in relation to trust (Son and Feng, 2019; Meyer et al., 2008; Routledge, 2007), with trust often playing a critical role in both bonding and bridging social capital (Son and Feng, 2019; Füzér, 2016). Social capital refers to the value of having social relationships with others, being part of large social networks and adhering to social norms (McDonald et al., 2010), and it is an important consideration for immigrant trust. This is because social capital promotes health/wellbeing among newcomers as they navigate new services (e.g., health and employment services) and settle/integrate into the host country's society post-migration (McDonald et al., 2010; Steinbach, 2007). As such, social capital can help with observing and interpreting the role of trust in institutions as it relates to health and wellbeing of migrants, immigrants, and refugees. As noted, within the present research, we focus on institutional trust. However, given the conceptual conflation of trust with related concepts in the literature, we also included similar concepts commonly used to describe and explain the relationship between individuals and social/public institutions as part of our search strategy (Wang and Gordon, 2011). These included confidence in institutions which can be described as a “multidimensional concept which generally refers to citizens' assessments or beliefs that several types of institutions […], as well as their representatives, will at least do no harm to or at best serve public interests” (Wang, 2014), distrust in institutions which can be described as “the refusal to accept vulnerability based on negative expectations regarding another's intention or conduct” (Verhoest et al., 2024), mistrust described as a “doubt or skepticism about the trustworthiness of the other” (Citrin and Stoker, 2018), and finally trustworthiness which differently than the other concepts, “[places] the onus of responsibility on the entity looking to be trusted—most commonly, the clinician, the organization, or the system—to be worthy of trust” (Meyer et al., 2024). In other words, the decision to trust institutions comes from the individuals' assessment of the institution as having attributes such as competence, willingness, integrity and capacity (Meyer et al., 2024).

Finally, within the present work we identify social institutions, as “the social structure and machinery through which human society organizes, directs and executes the multifarious activities required for human need” (Barnes, 1942), which could include systems such as, among others, the healthcare, military, legal, judiciary, educational, and political systems. Theoretically, we draw on the Luhmann's social systems theory as rationale for our decision to investigate trust in social institutions broadly, beyond that of medical institutions or the healthcare system, as a mechanism for promoting the health and wellbeing of immigrants. Indeed, trust in the healthcare system cannot be understood in isolation and it must be instead understood as connected with trusting other social systems such as trust in political and judicial systems, among others (Meyer et al., 2008). For example, Luhmann argues that trusting one social system is dependent on trust in other social systems (Luhmann, 1979), suggesting that trust in institution(s) is multidimensional (Brown, 2008) and rather than a linear path, should be considered as a complex web of interactions (Meyer et al., 2008; Luhmann, 1979). We adopt systems thinking theory in the present work and consider the critical role of trust across institutions as migrants integrate into the society of a host country.

2 Methods

The aim of this review is to systematically document the nature and extent of immigrants, migrants and refugees' trust in social institutions. Our approach followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018), and the framework proposed by Arksey and O'Malley (2005).

2.1 Identifying the research question (framework stage 1)

The present work was designed to answer the following research question: what is nature and extent and nature of immigrants, migrants and refugees' trust in the social institutions of their host countries?

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Articles included in the review meet the following inclusion criteria: Peer-reviewed empirical papers; focused on migrants, immigrant, and refugee populations; focused on institutional trust and adjacent concepts (i.e., institutional distrust, mistrust, confidence and trustworthiness); focused on institutions and organizations. The search was limited to English-language articles because of the research team's primary fluency in English but not limited to a year range so to ensure a comprehensive review of the literature. Articles excluded in the review meet the following summarized exclusion criteria: Focus on generalized trust, interpersonal trust, and social cohesion; focus on temporary migration and internal migrants; focus on trust in services, providers and professionals; papers not written in English. For a more detailed list of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, please refer to the Supplementary material.

2.3 Information sources (framework stage 2)

Four databases were utilized: Scopus (Multidisciplinary), Sociological abstracts (Sociology discipline), PubMed (Health discipline), and PsycINFO (Psychology and behavioral health disciplines).

2.4 Search (framework stage 3)

The search strategy, developed and refined with the assistance of a library scientist, was finalized on September 23rd, 2024. The full search strategy for each database is available in the Supplementary material.

2.5 Selection of sources of evidence (framework stage 3)

To ensure greater quality, HGN, SA, and GA independently screened a subset of the titles and abstracts as a practice screening exercise, where differences in inclusion/exclusion criteria interpretations were identified and addressed as a group. Following this exercise, the screening comprehensive process was conducted independently by three researchers (HGN, SA, and GA). Covidence software was used to identify duplicates and to conduct the title and abstract, as well as the full-text screening stages. Every article was screened by HGN, while the second reviewer for each article was either SA or GA. This was done for both screening stages (title and abstract, and the full-text screening stages). Any conflicts that arose during the screening were discussed and resolved through group consensus.

2.6 Data charting process (framework stage 4)

One researcher HGN independently developed data charting. To meet the aim of the work, articles were reviewed to identify information that fell under one or more of the following areas: theories and explanations (objective 1), recommendations and solutions (objective 2), across population groups comparisons (objective 3), defining trust concepts (objective 4), and areas for future research (objective 5). Two researchers then conducted data charting independently (HGN extracted 36 studies, while SA extracted 45 studies). Any challenges encountered at this stage were addressed as a team through group consensus.

2.7 Data items

The information collected during the extraction and data charting stages are as follows: title, year, authors, country of publication, study population characteristics, study location, social institutions of focus, study purpose, study design, approach, study variables, main findings, limitations, future research directions, type of trust/adjacent concept, definition of trust/adjacent concept, dimensions of trust/adjacent concept, measures/items, factors influencing trust, insights into the relationship, theories, frameworks, models, explanations and hypothesis that may explain the nature and extent of trust, and recommendations.

2.8 Synthesis of results (framework stage 5)

The data that were extracted and charted were organized into three different extraction tables: Extraction Table 1 in Supplementary material is a summary of the different studies included, and gives an overview of the studies' purpose, methods and main findings; Extraction Table 2 in Supplementary material focuses on the conceptualization of institutional trust and adjacent concepts and it presents information on how concepts are defined and measured; and Extraction Table 1 in Supplementary material attempts to describe the scope of institutional trust and adjacent concepts by reporting potential factors shaping institutional trust and adjacent concepts, related theories and frameworks, and finally recommendations to increase trust or confidence.

3 Results

3.1 Selection of studies

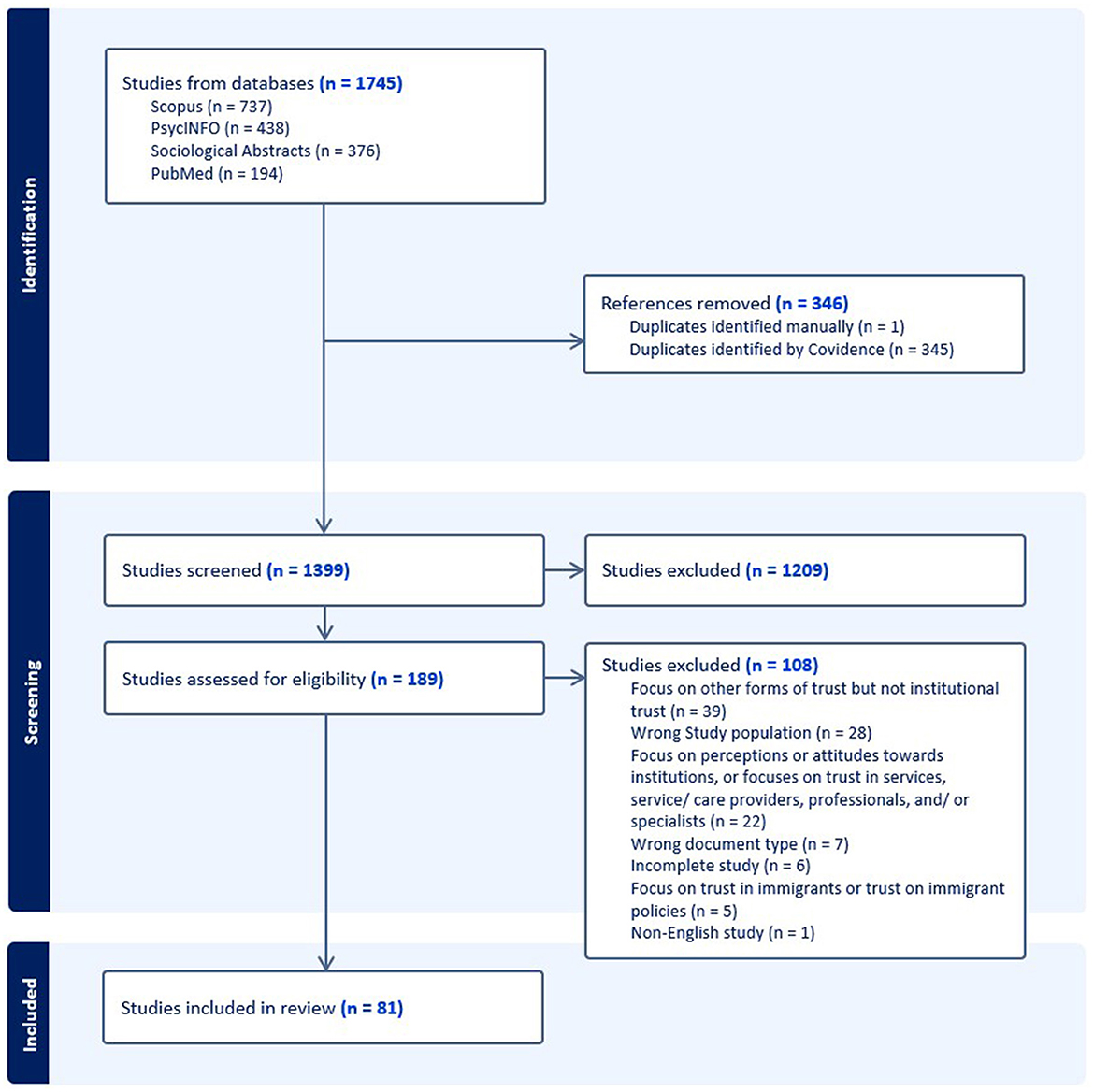

Our systematic search yielded a total of 1,745 studies, of which 346 were duplicates (Figure 1). Following title and abstract screening (n = 1,399), n = 1,209 were deemed irrelevant in accordance with the eligibility criteria (See the Supplementary material). A total of 189 articles were selected for full-text review and reviewed in their entirety for relevance. From the full-text screening, 108 studies were excluded based on 7 summarized items from the complete exclusion criteria (See the Supplementary material). A total of 81 articles met the stated inclusion criteria.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart summarizing the results of the systematic search and selection of evidence for this scoping review.

3.1.1 Characteristics of studies

Additional characteristics of the studies included in this review can be found in the extraction tables within the Supplementary material.

3.1.2 Study design of focus

Papers were published between 1996 and 2024. Most studies were quantitative in design (n = 65), with most employing a cross-sectional survey design (n = 15; See Extraction Table 1 in the Supplementary material). Few used longitudinal data (n = 4), despite many studies noting that to be an important area for future research (Becerra et al., 2017; Shin and Yoon, 2023; van den Broek, 2021; Wals, 2011; Born et al., 2015; Krieg et al., 2023; Politi et al., 2023). Other study designs included qualitative studies (n = 13), and mixed-method studies (n = 6). Qualitative methods for data collection most reported were interviews (n = 9) and focus groups (n = 8). One study conducted a literature analysis (Rakiibu and Malatji, 2023).

Most studies focused on institutional trust (n = 57), while the remaining focused on adjacent concepts, namely institutional confidence (n = 8), and institutional distrust (n = 7). Of the 57 studies focusing on institutional trust, specifically categorized institutional trust as political trust (n = 20).

3.1.3 Institutions of focus

The institutions of focus for which trust (or adjacent concepts) were studied was another key aspect. Included studies looked at institutions of the host country such as, police/law enforcement (n = 39), judiciary/courts of justice/justice system/justice department/legal system (n = 19), healthcare system/healthcare institutions/medical institutions (n = 16), federal/national parliament (n = 14), and federal/national government (n = 9). Other institutions of the host country were also identified in less frequency, such as child welfare/welfare system (n = 3), education/school system (n = 2), local/provincial government (n = 1), financial institutions (n = 1), and support institutions (n = 1).

Some studies did not specify the institutions, broadly speaking to public institutions (n = 3), political institutions (n = 2), government (n = 15). While some studies looking at immigrants in Europe looked at institutions related to the European union and not the specific country's' institutions, including European union (n = 1), European parliament (n = 1), and United Nations (n = 1).

Lastly, in addition to institutions, some of the included studies looked at services, organizations and key characters within the institutions such as, politicians (n = 7), political parties (n = 7), the civil service (n = 2), healthcare organizations (n = 1), social services (n = 1), cabinet (n = 1), legal authorities (n = 1), politics (n = 1), and municipal boards (n = 1).

3.1.4 Host countries of focus

The following host countries were reported across the papers: USA (n = 24), Australia (n = 7), Canada (n = 6), Germany (n = 5), South Korea (n = 3), Norway (n = 3), Israel (n = 3), Finland (n = 2), Denmark (n = 2), Belgium (n = 2), Netherlands (n = 2), Sweden (n = 1), Turkey (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), Lebanon (n = 1), England (n = 1), Poland (n = 1), France (n = 1), and South Africa (n = 1).

Some studies looked at a vast list of host countries, and as such were categorized as European countries (n = 9), or even more broadly as multiple countries (n = 6).

3.1.5 Study population of focus

We reviewed studies focusing on the following immigrant groups based on nationality: Polish (n = 6), Turkish (n = 5), Mexican (n = 4), Vietnamese (n = 4), Pakistani (n = 3), Iraqi (n = 3), Somalian (n = 3), Chinese (n = 3), Syrian (n = 2), Americans (USA; n = 2), Filipino (n = 2), Russian (n = 2), Ethiopia (n = 2), Indian (n = 1), Moroccan (n = 1), Cuban (n = 1), Puerto Rican (n = 1), Dominican (n = 1), Taiwanese (n = 1), Indonesian (n = 1), Uzbekistani (n = 1), Mongolian (n = 1), Sri Lankan (n = 1), Lebanese (n = 1), Iranian (n = 1), Ex-Yugoslav (n = 1), Korean (n = 1), Ghanaian (n = 1), Bangladeshi (n = 1), Nigerian (n = 1), and Canadian (n = 1).

Rather than specify nationality, some studies focus on immigrants from regions such as continental Africa migrants (n = 1), and Latin-American immigrants (n = 1), Spanish speaking countries of Latin America immigrants (n = 1), MENA region (Middle East and North Africa) immigrants (n = 1), Caribbean immigrants (n = 1), UK immigrants (n = 1), and Middle eastern immigrants (n = 1).

Some papers also focused on ethnicity, specifically minority immigrants (n = 6), Latino immigrants (n = 12), Muslim immigrants (n = 3), and Jews immigrants (n = 2).

In addition to nationality, region and ethnicity, studies also investigated intergenerational immigrants. Majority of studies looked at first-generation immigrants, while others looked at second-generation immigrants (n = 21), third-generation immigrants (n = 1), fourth-generation immigrants (n = 1), Newcomers (n = 1), and even 1.5 generation immigrants (n = 2), which is when an “immigrant arrives in the destination country as a child and is socialized as a member of that society” (Sibblis et al., 2022).

Differences were observed across papers in terms of migration status. Most studies focused on general immigrant and migrant groups (n = 75), with a few papers looking at more specific groups such as refugee groups (n = 3), undocumented migrants/immigrants (n = 2), and illicit immigrants (n = 1).

Other studies (n = 27) included immigrants from various countries instead of targeting one specific immigrant group. For example, Sun et al. (2024) study looked at different immigrant groups by using datasets from the World Value Survey and the European Value Study (Sun et al., 2024).

While almost all studies collected demographic data on study participants, few specifically focused on groups based on age [youth/children (n = 4); older adults (n = 2)], income/SES [low income (n = 1); developing countries (n = 1)], sex [woman (n = 5); men (n = 1)], marriage/relationship status (n = 2), race [whites (n = 1); people of color (n = 1)], and language [Arabic-speaking immigrants (n = 1); Spanish speaking (n = 1)]. However, we do importantly note that some of these characteristics, and others (e.g., age of arrival, level of education, political ideology, religion), were considered as important factors shaping institutional trust (and adjacent concepts), especially in quantitative studies, and thus were controlled for in the analysis (See Extraction Table 1 in the Supplementary material). Specific to the marriage/relationship status, we note that one study specifically focused on marriage immigrants, which is an immigration process involving individuals marrying an individual from the country they are immigrating to Yang et al. (2012).

3.2 Charting results

This review aimed to investigate the nature and extent of immigrants, migrants and refugees' trust in the social institutions of their host countries. To do this, we charted the data in alignment with five objectives below. All complete extraction charts can be found in the Supplementary material.

3.2.1 Objective 1

This objective relates to the existing theories, frameworks and models used across studies that may explain the nature and extent of immigrants, migrants, and refugees' trust in various social institutions. About half of the studies (n = 41/81) included in this review relied on these to support or frame their findings (See Extraction Table 3 in the Supplementary material).

Different theories were used to explain the same concept. For instance, representative bureaucracy theory (Campbell, 2021) suggests that increased diversity in the public workforce is needed to trust, cultural approach (Quaranta, 2024) suggests that trust is rooted in cultural norms and learned through early-life socialization which can impact institutional trust, and institutional approach (Quaranta, 2024) suggests institutions must meet the expectations and needs of individuals they serve for them to trust institutions. While not an exhaustive list, from these we can see that more than one theory or approach exists to explain the formation of institutional trust. Interestingly, some authors argue that while multiple theories exist, these are not necessarily exclusive from one another. For instance, individuals may be more trusting of institutions due to the cultural norms to which they have been exposed while growing up, which could then be reinforced if these said individuals believe as though they are understood by the institution of their host countries, their needs are met, and thus, the institution is performing well [see, (Quaranta, 2024; Shaleva, 2016)].

In the conceptual framework section of this paper, we also acknowledge that while related to one another, conceptually trust differs from that of confidence and distrust. From this, one could assume that different theories and explanations would be presented for each of the concepts. While some theories were uniquely applied to individual concepts [e.g., model for predicting trust in HCS (Pinchas-Mizrachi et al., 2020) was specific to institutional trust], we also observed the same theories being applicable uniformly across concepts. For example, the group position theory No Matches Found, which suggest that intergroup relations are influenced by individuals' perceptions of their group position in society, where there is competition for power, status, and rewards between dominant and the subordinate group (Piatkowska, 2015), was used to explain both the concepts of institutional trust and confidence. As well, an extension of this theory known as the group consciousness theory (Rakiibu and Malatji, 2023), was used to explain institutional distrust. Another example is cultural-persistence model (Sun et al., 2024), also known as the cultural approach/theory (Quaranta, 2024; Shaleva, 2016), being used to explain institutional confidence, while also used to explain institutional trust. From this, we note the following possibilities: (a) perhaps at the theory level these concepts overlap; (b) authors are not appropriately differentiating between similar yet conceptually distinct concepts such as confidence, trust and distrust; and/or (c) these theories are more a reflection of the relationship between individuals and institutions (i.e., interactions and perceptions of one another), more so than a reflection of whether the nature of the relationship is based on trust, confidence or distrust. Indeed, in relation to the last point, we note how procedural (justice) theory (Piatkowska, 2015; Kääriäinen and Niemi, 2014; Nägel and Lutter, 2023; Van Craen and Skogan, 2015), was cited across all concepts within the context of the relationship between individuals and police/justice system.

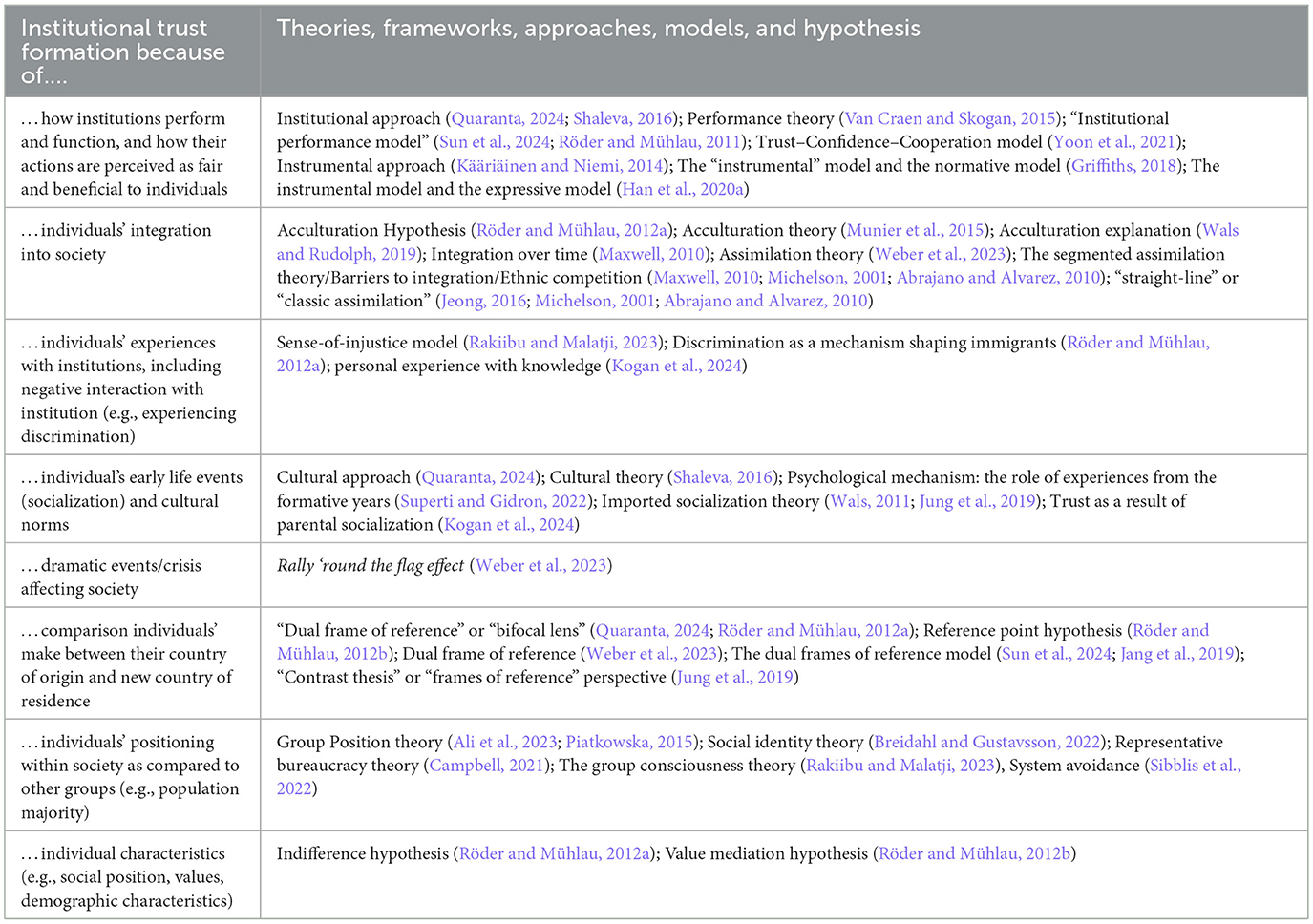

The most prominent theories are presented in Table 1. These theories showed up multiple times across various studies, despite differences in population groups, institutions, and contexts of the host and original countries, as were group based on how they explained institutional trust formation. These are important considerations not only to understand trust, but also when developing strategies to (re)build institutional trust of immigrants, migrants and refugees. For more details on these and other less prominent theories, please see Extraction Table 3 in Supplementary material.

3.2.2 Objective 2

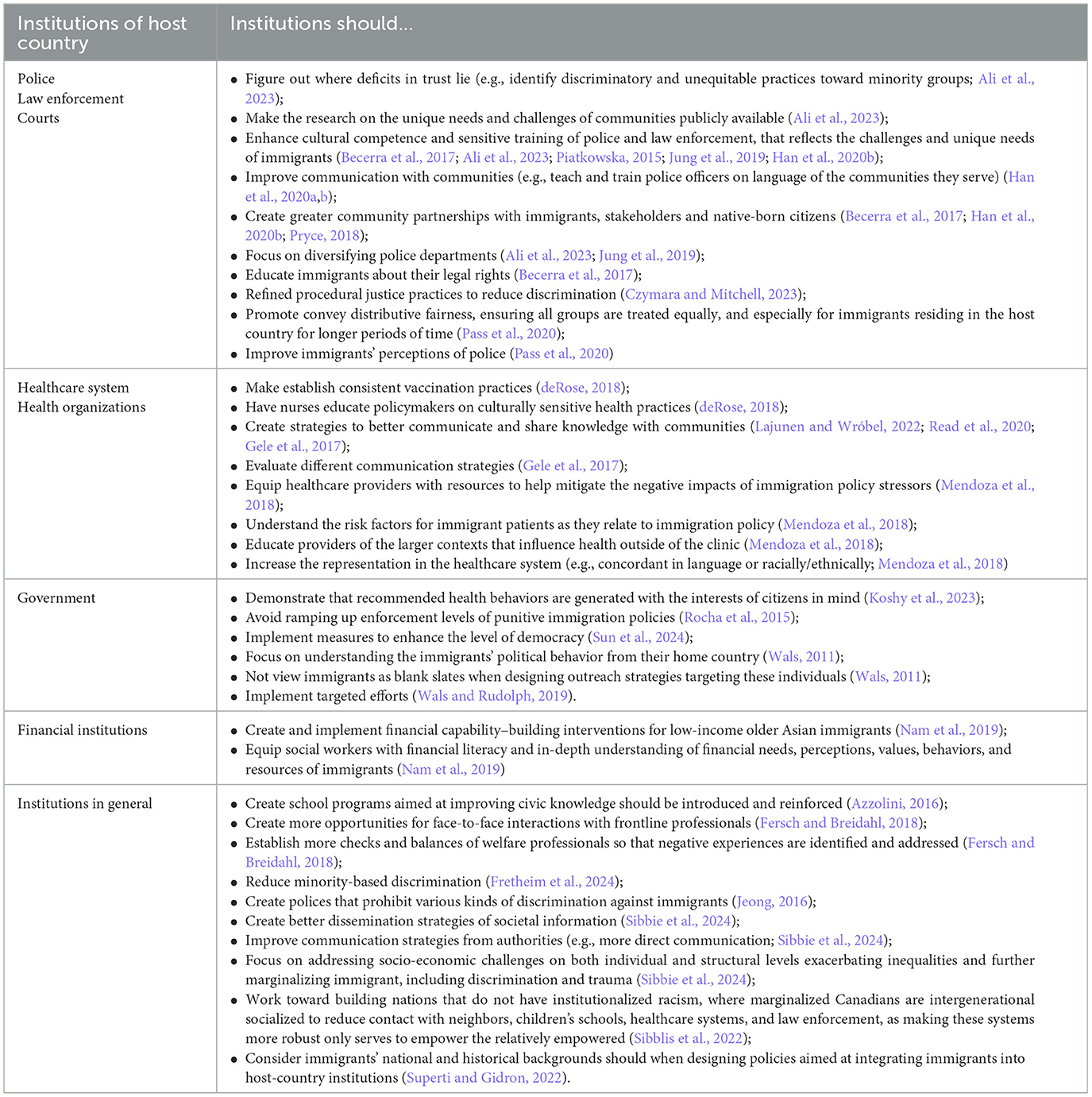

This objective relates to the different recommendations, strategies, and solutions proposed by the studies for different social institutions, that may help inform future health policy and practice aimed at maintaining institutional trust for these population groups. Here we note that 31 studies did not explicitly provide any recommendations to (re)build institutional trust and/or confidence in public institutions.

Only one of the studies that provided recommendations focused on refugees (Hall and Werner, 2022), while all others focused on migrants and immigrants. Despite the inclusion of studies focusing on different migrants and immigrants from different countries of origin and different host countries, recommendations across the papers acknowledged a lack of knowledge and understanding of the needs of the populations (i.e., immigrants and migrants) that institutions are serving, as well as lack of involvement with the same. This information is presented in Table 2, where recommendations are organized by the institution of focus. For more details on these, please refer to Extraction Table 3 in Supplementary material.

Table 2. Main recommendations to improve the relationship between migrant groups and institutions of the host country.

Most of the recommendations focused on institutions such as the police force and law enforcement systems, and relatedly most recommendations were addressed to institutions' representatives such as police officers. Moreover, very few recommendations were provided that addressed specific institutions (e.g., the education system). As well there was a lot of overlap in recommendations across institutions and trustees.

Despite the broad recommendations, which can be applicable across immigrant groups, some studies suggest that interventions or efforts to build trust should take into considerations the intended audience and consider how different groups may react to shifts in policy or practice (Bradford et al., 2022). This further supports the heterogeneity of migrant groups and suggests that there is a need for tailored and specific trust strategies (Lajunen and Wróbel, 2022), which should then be evaluated and adapted based on results of those evaluations. In alignment with this, one study emphasizes the importance of scholars, politicians and policy makers not assuming homogeneous political interests within groups of immigrants from the same region (Superti and Gidron, 2022). Indeed, the recommendation of not making assumptions about migrant groups is interesting, as most recommendations emphasized the need for institutions to become more knowledgeable of the communities they serve, including understanding migrant groups' culture, background, and their unique needs and challenges (see Table 2). These recommendations suggest that a first step in building trust is to connect with and better understand the different immigrant groups. Although not a lot of directions are given as to how to do this. The other main recommendation is the development of better communication strategies, followed by evaluation of said strategies (see Table 2).

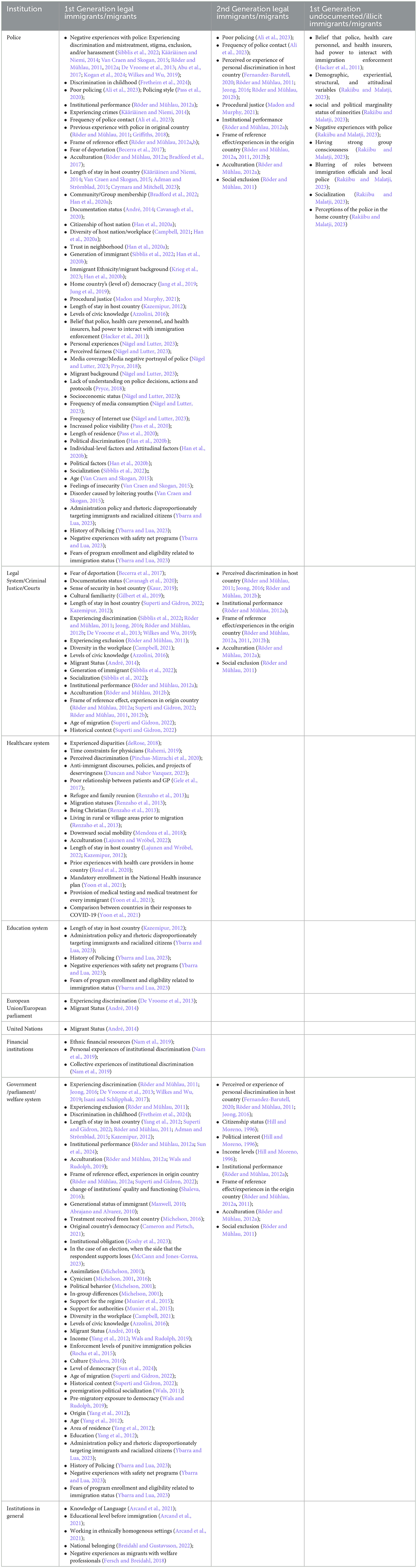

3.2.3 Objective 3

This objective relates to the differences (if any) in trust across different immigrants, migrants and refugees' groups and contexts. While the initial goal was to see if we could observe differences across immigrants, migrants and refugee groups, very few studies looked at refugee groups. Accordingly, all factors measured or hypothesized to impact trust, confidence and distrust levels in institutions reported in included studies are organized by institution, immigrant generation, and status (see Table 3). The three studies focused on refugee groups [see (Bou-Orm et al., 2023; Johnson-Agbakwu et al., 2014)] and two studies focusing undocumented migrants [see (Sudhinaraset et al., 2022)], did not highlight potential factors impacting institutional trust. Various countries, including the US, award citizenship to children born within the country regardless of the parent's immigrant status via the principle of “birthright citizenship” (Reed, 2025). As such in this review, undocumented or illicit immigrants/migrants are considered 1st generation, while their children would be 2nd generation. These categories are reflected in Table 3.

Table 3. Factors and/or variables impacting institutional trust (or adjacent concepts) organized by institutions, generation and immigration status.

Unique to refugees, exposure to violence and associated trauma (including posttraumatic stress) is suggested to have impacted trust across various institutions, including the police, courts and government (Hall and Werner, 2022). It is anticipated, but not yet explored, that institutional trust is shaped by factors identified within migrant and immigrant populations. However, this is an area for future research.

The majority of studies focused on 1st generation immigrants, with only a few (n = 9) looking at 2nd generation immigrants. Within the nine studies that look at 2nd generation immigrants, the majority also focused on 1st generation immigrants within the same study for comparison. Only two studies looked at 2nd generation immigrants (Fernandez-Barutell, 2020; Hill and Moreno, 1996). Once again, the scarcity of studies focused on 2nd generation immigrants, make it more challenging to understand how these different groups differentiate from one another in terms of factors impacting their level of trust. We do note that across studies that there is a difference in levels of trust between 1st and 2nd generation immigrants (Ali et al., 2023) in that 2nd generation immigrants are reported to be less trusting of institutions as compared to the 1st generation immigrants (Röder and Mühlau, 2012a, 2011; Maxwell, 2010; Jeong, 2016; Röder and Mühlau, 2012b). This is because 1st generation immigrants are more sensitive to perceived discrimination, have gone through the disruptive process of changing countries, have lower expectations on institutions, and do not stayed in host country for a longer period of time yet, as compared to their 2nd generation counterparts (Röder and Mühlau, 2012a, 2011; Maxwell, 2010; Jeong, 2016; Röder and Mühlau, 2012b). These reasons are supported by theories presented in objective 1 of this results section. Namely, being more sensitive to discrimination can be explained by the “straight-line” or “classic assimilation” theory (Jeong, 2016; Michelson, 2001; Abrajano and Alvarez, 2010), which explains how immigrants face discrimination in their everyday lives due to stigmatization as “unassimilable outsiders” (Jeong, 2016). As well, low expectations can be explained by the reference point hypothesis, which proposes that immigrants' trust in the institutions of the host country is expected, because in comparison to their country of origin, the quality of institutions are better and so, immigrants are less critical of the host-country institutions (Röder and Mühlau, 2012a). Relatedly, it is suggested that the disruptive process of changing countries may also contribute to more positive evaluations of the host society (Maxwell, 2010). Lastly, the impact of length of stay can be explained by the Acculturation Hypothesis (Röder and Mühlau, 2012a).

Many of the factors we listed in Table 3 for 2nd generation immigrants are also listed for 1st generation immigrants. This may suggest that the difference in trust between these two groups may not be because of different issues, challenges and barriers, but rather, in the degree (or level) to which these factors matter to the two generations. Differences across institutions and how much different institutions matter to different generation of immigrants (or play a role in the lives of individuals), may also be at play here. For instance, one study suggests that immigrants' overconfidence is somewhat less pronounced for the police than for the legal system, and that the lower trust of the second generation is also more strongly observed for the police (Röder and Mühlau, 2012b). There is also some overlap of factors with 1st generation undocumented/illicit immigrants/migrants, such as negative experiences with police (Rakiibu and Malatji, 2023), also suggest some overlap between the groups. However, we also note some more unique factors such as, the belief that representatives of institutions have the power to interact with immigration enforcement (Hacker et al., 2011), group consciousness (Rakiibu and Malatji, 2023), and blurring of roles between immigration officials and local police (Rakiibu and Malatji, 2023), and how these seem to relate to situations where their residence and safety within the country are at risk from interactions with immigration officers and law enforcement, directly relating to their precarious legal status.

Given than very few studies looked and 2nd generation migrants, refugees and undocumented/illicit immigrants/migrants, we proposed that future research focuses on these populations sub-groups, as comparisons to their 1st generation and citizens/born in the country counterparts, to inform trust strategies aimed to maintain and build trust over time within and across generations.

Further details as to how these factors shape institutional trust, such as whether they promote or hinder institutional trust is presented are presented in Extraction Tables 1, 3 in the Supplementary material. We propose stakeholders want to change policy or create trust strategies, take this into consideration.

3.2.4 Objective 4

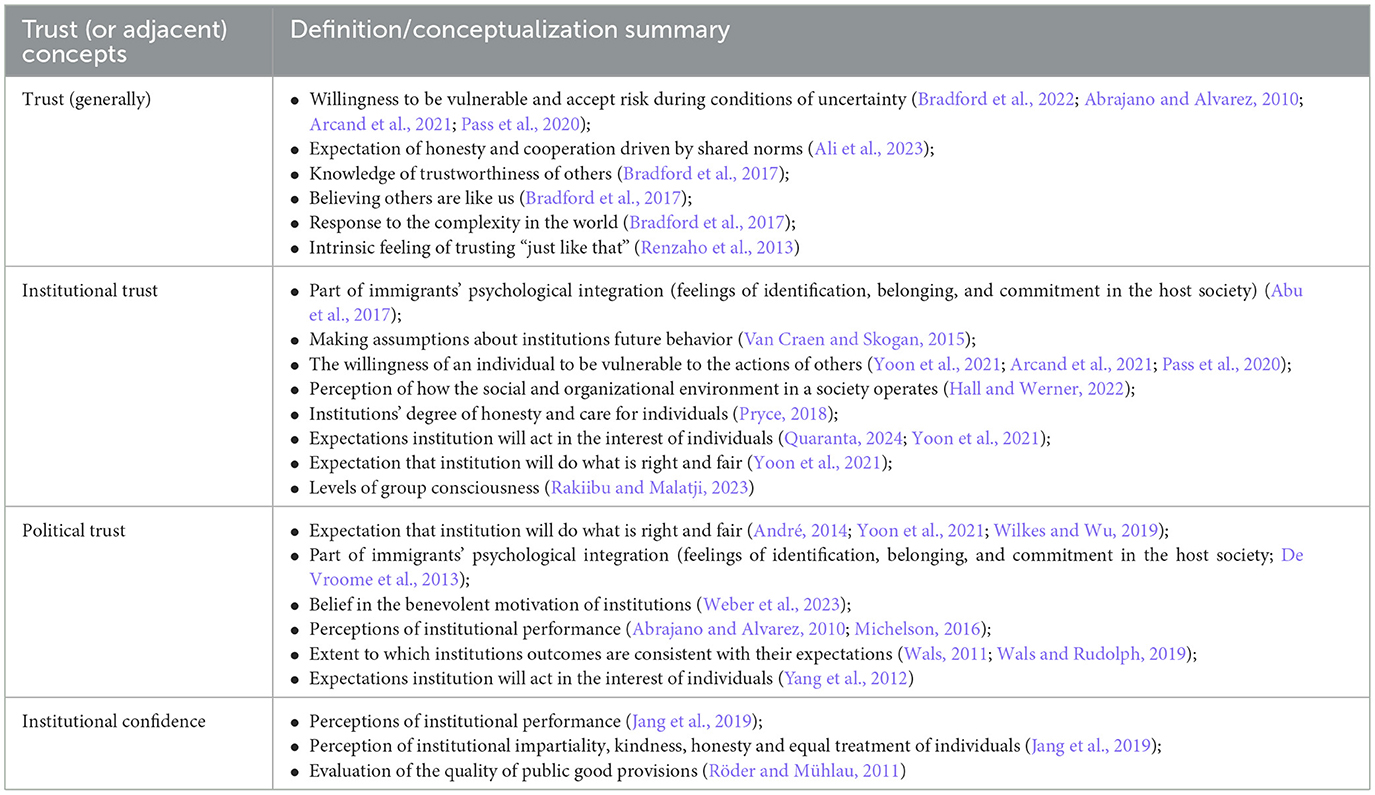

This objective relates to how trust in institutions is defined for immigrant, migrant and refugee' groups. Despite the focus on institutional trust (or adjacent concepts), only a handful of studies (n = 27) explicitly defined the concept of focus for their readers in the background or theoretical section of their paper, and even fewer explicitly identified the dimensions of the studied/measured concept (n = 8). This is problematic when considering that how trust is measured and conceptualized can impact how trust interventions are developed and their success measured. Understanding how trust is defined or conceptualize may inform future items in trust measures, which can be tailored to immigrant and migrant population groups. Table 4 presents a summary of the definitions and conceptualizations of trust and adjacent concepts across included studies. To see the full definitions, see Extraction Table 2 in the Supplementary material.

From Table 4, however, we note inconsistencies in how trust and adjacent concepts are defined and conceptualized. For example, institutional trust was predominantly defined as the willingness of an individual to be vulnerable to the actions of others accepting a certain level of risk (Yoon et al., 2021; Arcand et al., 2021; Pass et al., 2020), but also defined as expectation that institution will act in the interest of individuals (Quaranta, 2024; Yoon et al., 2021), and that they will do what is right and fair (Yoon et al., 2021). This may become a problem, considering that consistency in how a concept is constructed is key for the reliability and validity of measures and consequently the quality of the findings generated from the used measures.

Further, while consistency is crucial when defining and conceptualizing the same concept across papers, so too is clearly outlining the differences between the different concepts. For instance, we note that perceptions of institutional performance (Abrajano and Alvarez, 2010; Michelson, 2016; Jang et al., 2019) is how both institutional confidence and political trust are conceptualized. Because evidence suggests that these two concepts are different, then this should also be reflected in the how they are defined in the papers (see conceptual framework section of this paper). As well we note an overlap between defining trust generally and institutional trust. Indeed, most studies included in this review had very broad definitions of trust and adjacent concepts, which not only could be applied to various institutions, but also applied to different population groups (outside of immigrants, migrants and refugees). Only two papers clearly conceptualized trust (institutional trust and political trust), in relation to the migrant population, such that trust exists immigrants' psychological integration related to feelings of identification, belonging, and commitment in the host society (De Vroome et al., 2013; Abu et al., 2017).

3.2.5 Objective 5

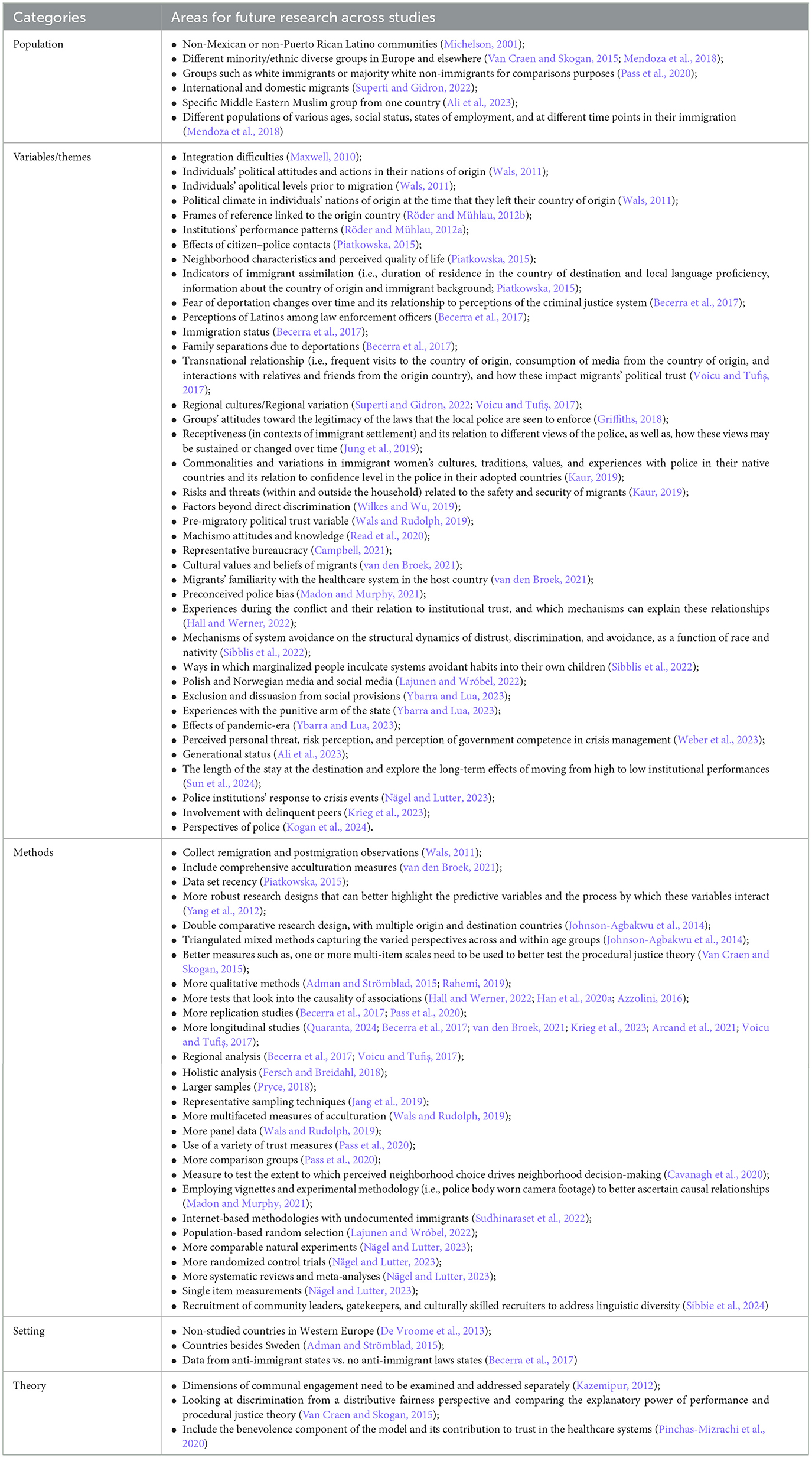

This objective relates to gaps in the literature and areas for future research related to promoting immigrants, migrants and refugees' trust in social institutions from included studies. Notable gaps and areas for future work have been identified for almost all studies included in this review (See Extraction Table 1 in Supplementary material). These were grouped together according to five different categories (i.e., population, variables/themes, theory, methods, and setting) outlining areas that future work should expand on (See Table 5).

The population category refers to specific populations that should be investigated in future research studies. Indeed, investigating institutional trust across different population groups and population make-ups, especially across minority groups, is something acknowledged by studies as needed in future work (Adman and Strömblad, 2015). Interestingly one study mentioned the need to look at international and domestic migrants (Superti and Gidron, 2022), which was part of our exclusion criteria. This means that it is likely that current work on this exists, but findings from these were not something we explored here.

The category of variables/themes speaks to variables, variables' relationship, themes that have not yet been investigated, or not investigated extensively enough, that researchers should consider investigating quantitatively and/or qualitatively in future research studies. We note that some of the variables listed in Table 5, such as generational status (Ali et al., 2023), the length of the stay in the host country (Sun et al., 2024), and others have already been included in some of the studies we reviewed. We advise researchers to focus their work on those still yet needed to be explored.

The category of methods speaks to different approaches to collect and analyze data not yet used that may be relevant for future work. Across the included studies we note the need to collect data on premigration, post migration and remigration, and how trust and institutions change over time. Indeed, a big emphasis across studies, is the need for longitudinal studies. Also, we note the need to include better measures, better sampling techniques, larger samples, more replication studies and more qualitative studies.

The categories with the least number of items are setting and theory, which speak to different countries within which to investigate institutional trust, as well as different theoretical or conceptual considerations needed for future research, respectively. For settings, authors propose looking at states that are not in favor of migration such as states that support and pass anti-immigrant laws, as well as other understudied countries in Europe. For theories, authors propose the comparison of theories, as well as expansion of existing theories.

Overall, there are various directions that future work can take when exploring the nature and the extent of institutional trust among different migrant groups. Most studies highlight that prominent areas of further investigation fall under the categories of methods and variables/themes. This makes sense as we showcase a wide variety of studies from across the world, which looked at various migrant groups from various backgrounds (see the characteristics of the studies section of this review). From Table 5, we conclude that a lot of work is needed to better understand institutional trust (including political trust) formation and disintegration (André, 2014). This is especially important for understudied and underrepresented population groups, which could help establish generalizability and causality claims (Griffiths, 2018; Rahemi, 2019).

4 Discussion

Despite the importance of institutional trust for the wellbeing of populations and success of societies, not enough is known about the nature and extent of immigrants, migrants, and refugees' trust in social institutions, or why it may (or not) be declining over time. To fill this gap, we reviewed the breadth of literature on this topic with hopes to better understand the current factors and theories impacting and explaining trust, the different ways in which trust (and adjacent concepts) are conceptualized and measured, the current recommendations to build trusting relationships with migrant groups, and finally the current literature gaps and areas for future research.

An important focus of this review was the theories cited across papers, which were used to explain the relationships between migrant groups and social institutions as they relate to trust. We highlight how there was a lot of overlap in theories across different institutions and across concepts. This could mean that institutional trust, distrust and confidence may relate to one another theoretically, and that strategies to instill trust and confidence in immigrants on one institution, may be transferable and applicable to other institutions. This aligns with the systems theory we present in the conceptual framework section of our review. Understanding these can help guide the development of potential interventions aimed at building or maintaining trust. For example, theories like institutional approach (Quaranta, 2024), argues that trust emerges when institutions are responsive and meet the expectation and preferences of the individual. From this, we could then hypothesize that institutional trust in the healthcare system would increase if the healthcare system were to become more responsive and better meet the expectations and preferences of the populations they serve.

On the other hand, we also acknowledge context-specific theories, whose application and interpretation varied depending on the specific situation, environment, or population under study. In this case, different migrant groups would have different trust needs. An example of this, is the sense-of-injustice model (Rakiibu and Malatji, 2023), which explains how immigrants (often members of minority groups) feel that they have been unjustly treated by the criminal justice system, including the police (Rakiibu and Malatji, 2023). In this case, it is not just about the performance and well-functioning of the institution to support immigrant needs, but beyond that, it is about addressing the prevailing stigmatization, exclusion, and discrimination faced by these individuals from these institutions. Indeed, we emphasize here that different theories may inform different avenues for action. Some theories suggest that institutional trust is something that is learnt throughout life, others that institutional trust is inherent to the individual, and others that institutional trust is a reaction to the institutions' functioning. Theories, models and frameworks are important as they help frame and explain phenomena, and as such we proposed that future work rely on these when investigating institutional trust among immigrants. We also propose that future studies attempt to build on already established theories or even generate new theories. This is consistent with our other finding that more qualitative studies are needed to more comprehensively investigate institutional trust among migrant groups. Future studies should consider implementing methodologies such as Grounded theory methodology for this purpose (Mey, 2022).

Relatedly, institutional trust would then also vary differently across minorities groups and refugee groups. This becomes even more layered when considering the difference between the country of origin of immigrants and the host country (and respective institutions), and how these also play a role in how immigrants come to trust the institutions of the host country. A more important differentiation perhaps, may come from the different generations and different migration status (e.g., refugee status and undocumented status), and how these may shape trusting relationships differently. This makes sense as one of the main factors affecting all groups were the experiences in home country or political state of home country, and how these shape the perceptions and expectations toward the new host country. It is possible that the unique circumstances between the groups (i.e., reason of migration) may lead them to prioritize concerns that directly impact on their livelihood (e.g., deportation policies) beyond concerns toward institutions' general functioning. This supports the heterogeneity of immigrant groups that the papers acknowledge. Relying on an intersectionality framework [see (Macgregor et al., 2023)] would be recommended for future studies to adequately consider the diversity within migrants as a population group. More specifically we acknowledge the notable gap in the refugee perspective within the body of literature.

Various factors were identified as shaping the relationships between immigrants and social institutions, both positively and negatively, with factors such as discrimination standing out as prominent across population groups and institutions. These factors highlight some of the current challenges and barriers experienced by migrants which in turn may impact on their integration, as well as health and wellbeing post-migration. We also discussed the importance of defining trust and measuring trust and the inconsistencies observed among papers. Lastly, we highlight how various papers failed to define or conceptualize trust and failed to provide recommendations for action.

Another important focus of the paper was on documenting different recommendations and strategies proposed that may help maintain institutional trust for these population groups. Few studies provided recommendations to improve, build, or maintain trust. The ones that did, focused on community-level interventions such as better communication strategies that institutions should rely on when communicating with immigrant groups or educational strategies aimed at better train representatives of institutions for when interacting with immigrant groups. There was also an emphasis on the need to better understand community-specific wants and needs. Interestingly, despite the large body of work on this topic, from the papers we reviewed only one paper published last year by Sibbie et al. commented on an established intervention and its effectiveness (Sibbie et al., 2024). The one intervention we captured, aimed to increase trust among migrant parents in Finland in child welfare and other services through a group programme (Sibbie et al., 2024). Despite its potential, the authors found no change in trust levels pre- and post-intervention (Sibbie et al., 2024). An area for future research is longitudinal intervention-based studies, as currently only one study explicitly examined the long-term effectiveness of a trust intervention. Regardless of the results, Sibbie et al.'s paper (Sibbie et al., 2024) should be used as a guide in the development, implementation and evaluation of future trust interventions for migrant groups. Also interesting is the finding that a lot of recommendations were made with the institution's representatives as the important actors, as opposed to the system at large. While these representatives (e.g., doctors, police officers and politicians), are part of the institutions, it does bring to the forefront all the different arguments pertaining to nature of the relationship between interpersonal trust and institutional trust (please refer to our review's conceptual framework section). It could be that it is first needed to increase interpersonal trust relating to the relationship between migrants and immigrants, which will then lead to the increase in institutional trust toward the systems at large. This, however, should be further explored within the context of the immigrant, migrant and refugee groups. While it may be manageable to investigate and document trust, our findings suggest that it may be a lot harder to act on it. Further, our work also highlights how trust and confidence in institutions depends on both individual migrating and the institutions of the host country. Based on identified variables, we recommend that interventions be developed and implemented at all levels of the Bronfenbrenner's ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1974). Lastly, our findings revealed that only a small number of studies provided practical recommendations, and these were mostly focused on the local (area of the study) or community level. Consequently, we recommend that future research develop more generalizable guidance (i.e., broader policies and system-level strategies), strategies for adapting recommendations to different populations and contexts, and practical approaches for (re)building institutional trust among immigrant, migrant, and refugee groups.

All these important theories and considerations help paint a complex picture, one that suggests institutional trust is layered and nuanced. This is supported by our findings that showcase many different definitions and conceptualizations of institutional trust, various measures utilization, and inconsistencies across studies regarding these. Some studies used the terms of institutional trust and institutional confidence, interchangeably. For example, some studies defined institutional/political trust using the concept of confidence [see, (Yang et al., 2012; Yoon et al., 2021)], which may suggest that they are related to one another or the same. Furthermore, some studies measure confidence but then included trust items [see e.g., (Krieg et al., 2023)], or vice-versa. Despite very few papers reporting on the dimensions of the concepts measured, it seems plausible that institutional trust would be a multidimension construct. Future research on the development and/or validation of trust measures should report on this.

Our results demonstrate that there is a lot of literature that looks at institutional trust and similar concepts such as confidence and distrust, but that this is a growing field within the study of migrant population groups. For instance, important studies relating to institutional trust among migrant groups emerged during the COVID-19, a time of great uncertainty and risk for many [see (Lajunen and Wróbel, 2022; Yoon et al., 2021; Weber et al., 2023; Koshy et al., 2023; Ybarra and Lua, 2023; Duncan and Nabor Vazquez, 2023)]. Future research should focus on investigating trust changes over time. Not only in terms of how many years immigrants stay in a country, but also in terms of how societal norms, values and politics change during that time. Furthermore, we also recommend that future work consider the role of media in public perceptions of institutions. This relates to evidence suggesting that action should be taken to ensure that police are not perceived to be harassing specific immigrant groups in hopes to build trust in the police intentions (Pass et al., 2020). Considerations regarding transparency and accountability, as related to the need for greater checks and balances (Fersch and Breidahl, 2018), as well as how certain institutions or population groups are portrayed in media, would also be important in future work. Another interesting variable that has not been fully explored is the different immigration pathways (i.e., whether the immigrant was “invited” or “forced” to immigrate), and how these relate to institutional trust. This may be especially interesting to study within circumstances where migrants feel “obligated” or “coerced” to engage with systems (i.e., adhering to healthcare recommendations) due to feelings of gratefulness toward institutions, and/or fear of repercussions for not doing so, that may impact their immigration status (Koshy et al., 2023). Additional interesting areas for future investigation not currently present in the body of literature would include, migrants' career and profession in the host country, immigrants' perspectives on immigrant policies/law changes, remigration (returning to home country post-emigration), investigating institutional trust for immigrants who have immigrated more than once, and finally, at the individual-level, how the trust level of second-generation immigrants (i.e., immigrants' children), as well as factors unique to them that shape this trust, may influence the trust of the 1st-generation immigrant parents. Lastly, considering the theoretical and empirical connection between social capital and trust (see our conceptual framework section), future research should explore how strengthening social capital, both within migrant communities and between migrants and institutions, may help foster interpersonal and institutional trust. Approaches such as community engagement initiatives or programs that facilitate interaction between migrants and institutional representatives may be particularly valuable. While our review did not search for studies on social capital, recognizing the relationship between trust and social capital highlights an important area for future investigation and practice.

5 Limitations

This review allowed us to showcase the breadth of literature on works investigating institutional trust among various immigrants, migrants, and refugee groups of individuals across the globe, which we did systematically and rigorously following the PRISMA-ScR's checklist and the Arksey and O'Malley's framework. Despite this, our work is not without limitations. Firstly, we did not publish or register a protocol in advance of this review. While this step is encouraged, it can be time-consuming, and the authors decided not to go this route. To maintain the integrity of the work, detailed reports were kept on the development of the review and decisions made along the way that all authors could refer to at all stages of the review. Secondly, we did not conduct a critical appraisal of the sources of evidence. As such, we make no claims about the quality, strength, or rigor of each of the studies included in this review. We do present information extracted from the included studies on reported limitations and methods used, including how variables were measured, that readers may choose to review (See Extraction Table 1 in the Supplementary material). Thirdly, while search terms were selected to create a comprehensive and exhaustive list of relevant studies for screening and later extraction, it is possible that some terms were missed. Consequently, some relevant studies may not have been captured by our search. For instance, while conducting this review, more specifically during the screening and extraction stages, authors noted that many different terminologies were used to characterize the migrant and immigrant groups, such as illicit immigrants, 1.5 immigrants, expat/expatriate, and others. However, we were not familiar with these terms beforehand. Consequently, despite efforts to create an exhaustive list of key search terms, we may still not have captured all the different papers on our topic of focus. To minimize this risk, we consulted with a library scientist to help in the development of search strategies. Lastly, it is also possible that relevant information was missing from the development and interpretations of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. For instance, we only included empirical papers, and as such, other document types such as government documents, reports, and books, were omitted from this review.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, we hope that readers have come to appreciate the complexity of understanding and conceptualizing institutional trust. Many factors shape these levels of trust, and these factors vary slightly across different migrant groups, institutions, and contexts. As such we argue that institutional trust is complex and nuanced and must be addressed with strategies at the individual and organizational levels, as well as with both broad and tailored strategic goals. Despite the large body of work, there is still a lot that is not known. We outline key areas for future research with hopes to guide future studies. While trust is needed for the health and wellbeing of migrant groups and societies at large, trust is quick to weaken, and as such, trust in social institutions can no longer be taken for granted or expected. It must instead become something that institutions and organizations actively prioritize, promote, and nurture. We argue that this is especially important for immigrants, migrants, and refugees who are most impacted during times of greater risk and uncertainty. The information we present here can be used by researchers, industry, policymakers, and other important stakeholders to inform future research, health policy, and health promotion practices.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HGN: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SA: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. GA: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research Op. Grant: Emerging COVID-19 Research Gaps and Priorities-Confidence in science [Grant #GA3-177730]; and a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Network Insight Development Grant [Grant # 430-2020-00447].

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Jackie Stapleton, Library Scientist at the University of Waterloo, for her contributions to our research design.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1573017/full#supplementary-material

Table 1 | Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria used for the selection of studies.

Table 2 | Complete search strategy for each included database used for the acquisition of studies screened.

Table 3 | Extraction table 1 summarizing key characteristics and findings of studies.

Table 4 | Extraction table 2 conceptualizing institutional trust and adjacent concepts.

Table 5 | Extraction table 3 reporting on determinants and the scope of institutional trust and adjacent concepts.

References

Aboueid, S. E., Herati, H., Nascimento, M. H. G., Ward, P. R., Brown, P. R., Calnan, M., et al. (2023). How do you measure trust in social institutions and health professionals? A systematic review of the literature (2012–2021). Sociol Compass 17:e13101. doi: 10.1111/soc4.13101

Abrajano, M. A., and Alvarez, R. M. (2010). Assessing the causes and effects of political trust among U.S. latinos. Am. Polit. Res. 38, 110–141. doi: 10.1177/1532673X08330273

Abu, O., Yuval, F., and Ben-Porat, G. (2017). Race, racism, and policing: responses of Ethiopian jews in Israel to stigmatization by the police. Ethnicities 17, 688–706. doi: 10.1177/1468796816664750

Adman, P., and Strömblad, P. (2015). Political trust as modest expectations. Nord. J. Migr. Res. 5, 107–116. doi: 10.1515/njmr-2015-0007

Alesina, A., and La Ferrara, E. (2002). Who trusts others? J. Public Econ. 85, 207–234. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00084-6

Ali, M. M., Murphy, K., and Sargeant, E. (2023). Advancing our understanding of immigrants' trust in police: the role of ethnicity, immigrant generational status and measurement. Polic Soc. 33, 187–204. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2022.2085267

André, S. (2014). Does trust mean the same for migrants and natives? Testing measurement models of political trust with multi-group confirmatory factor analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 115, 963–982. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0246-6

Arcand, S., Facal, J., and Armony, V. (2021). Understanding the integration process through the concept of trust: a case study of latin American professionals in Québec. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 22, 749–767. doi: 10.1007/s12134-020-00765-2

Arksey, H., and O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Azzolini, D. (2016). Investigating the link between migration and civicness in Italy. Which individual and school factors matter? J. Youth Stud. 19, 1022–1042. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2015.1136056

Barnes, H. E. (1942). Social Institutions in An Era of World Upheaval. New York, NY: Prentice-Hall Inc.

Becerra, D., Wagaman, M. A., Androff, D., Messing, J., and Castillo, J. (2017). Policing immigrants: fear of deportations and perceptions of law enforcement and criminal justice. J. Soc. Work 17, 715–731. doi: 10.1177/1468017316651995

Born, M., Marzana, D., Alfieri, S., and Gavray, C. (2015). “If it helps, I'll carry on”: factors supporting the participation of native and immigrant youth in Belgium and Germany. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 149, 711–736. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2014.972307

Bou-Orm, I., Devos, P., and Diaconu, K. (2023). Experiences of communities with Lebanon's model of care for non-communicable diseases: a cross-sectional household survey from Greater Beirut. BMJ Open 13:e070580. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070580

Bradford, B., Jackson, J., Murphy, K., and Sargeant, E. (2022). The space between: trustworthiness and trust in the police among three immigrant groups in Australia. J. Trust Res. 12, 125–152. doi: 10.1080/21515581.2022.2155659

Bradford, B., Sargeant, E., Murphy, K., and Jackson, J. (2017). A leap of faith? Trust in the police among immigrants in England and Wales. Br. J. Criminol. 57, 381–401. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azv126

Breidahl, K. N., and Gustavsson, G. (2022). Can we trust the natives? Exploring the relationship between national identity and trust among immigrants and their descendants in Denmark. Nations Natl. 28, 592–611. doi: 10.1111/nana.12834

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Dev. 45:1. doi: 10.2307/1127743

Brown, P. R. (2008). Trusting in the New NHS: instrumental versus communicative action. Sociol. Health Illn. 30, 349–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01065.x

Cameron, S., and Pietsch, J. (2021). Migrant attitudes towards democracy in Australia: excluded or allegiant citizens? Aust. J. Polit. Hist. 67, 260–275. doi: 10.1111/ajph.12727