- 1Faculty of Humanities, North West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

- 2School of Public Policy, Governance and Public Policy, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Introduction: Corruption remains a critical governance challenge globally, yet its role in perpetuating state fragility is underexplored in political science literature. In the South African context, corruption extends beyond ethical or administrative failings, functioning as a structural disorder that erodes institutional resilience, economic development, and political stability.

Methods: This study employs a thematic content analysis, integrating empirical evidence and governance risk frameworks to examine the systemic nature of corruption and its impact on state fragility.

Results: The analysis identifies four key dimensions through which corruption exacerbates governance fragility: institutional weakening and bureaucratic dysfunction; economic stagnation and developmental failure; erosion of public trust and legitimacy; and the perpetuation of a corruption–fragility cycle. The findings reveal that corruption sustains a self-reinforcing dynamic that obstructs reform and deepens state vulnerability.

Discussion: The results underscore the necessity for comprehensive anti-corruption strategies that move beyond punitive measures. Strengthening institutional integrity, promoting economic diversification, and enhancing public accountability are crucial to breaking the corruption–fragility cycle. By framing corruption as a central determinant of political and economic instability in fragile states, this study contributes to advancing scholarship on governance, state resilience, and sustainable development.

1 Introduction

Corruption is widely recognised as one of the most entrenched governance challenges of the 21st century. Traditional frameworks often approach it through legal, ethical, or economic lenses, which, while useful, tend to obscure its systemic nature and political embeddedness. Particularly in fragile states, corruption is not merely a set of isolated infractions but a deeply integrated governance disorder that weakens institutional resilience and perpetuates instability (Rothstein, 2011). This study critically re-examines how corruption is conceptualised within governance and risk management paradigms. It contends that existing models insufficiently account for the recursive and structural dimensions of corruption, which serve to undermine state institutions from within. Corruption in such contexts operates less as an administrative anomaly and more as a central mechanism through which political power is consolidated and economic extraction is sustained (North et al., 2009; Fukuyama, 2018). Rather than viewing corruption as an external or manageable risk, this study reframes it as an endogenous force embedded in institutional networks and political economies (Marquette and Peiffer, 2018; Khan et al., 2017).

South Africa provides a compelling case for this reframing. Despite a robust constitutional and legal anti-corruption framework, the country continues to experience recurrent governance failures, institutional collapse, and high-profile corruption scandals (Chipkin and Swilling, 2018; Vyas-Doorgapersad, 2024). These patterns signal more than enforcement failures; they reveal a structurally embedded risk that threatens the very foundations of public accountability and state legitimacy. By drawing on historical institutionalism, political economy, and governance risk analysis, this study explores the causal mechanisms through which corruption contributes to state fragility. It examines how entrenched networks of patronage, institutional erosion, and elite-driven resource capture sustain governance breakdowns, particularly in the post-apartheid state. This interdisciplinary approach allows for a more holistic understanding of corruption, not merely as a symptom but as a central driver of systemic dysfunction (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012; Rotberg, 2019).

The central aim of this study is twofold. First, it interrogates the limitations of dominant corruption paradigms by developing a reconceptualisation that reflects its systemic character. Second, it applies this reconceptualisation to the South African context, illustrating how corruption undermines institutional resilience through political, economic, and administrative channels. In doing so, the study contributes to a growing body of research that seeks not only to understand corruption as a risk but to reframe it as a constitutive element of fragile governance systems.

2 Research methodological orientation

This research is conceptual and descriptive in nature and critically examines the interconnectedness between corruption risk, risk management, and state fragility, with a specific focus on South Africa. Unobtrusive research techniques are used to analyse data. Firstly, conceptual analysis is particularly suitable for this study because it enables a systematic examination of theoretical constructs and governance frameworks, providing a structured means of understanding corruption as a systemic governance disorder rather than a mere isolated administrative issue. However, it is important to clarify that the aim of this study is to explore theoretical linkages between corruption and state fragility, rather than to establish a deterministic or causal relationship. This distinction is critical because while conceptual analysis facilitates an examination of how theoretical constructs interact and influence governance processes, it does not provide a basis for inferring causality (Maguire and Delahunt, 2017; Maxwell, 2013). Secondly, to deepen the analysis and ensure robust methodological rigor, thematic analysis was also employed to identify and interpret recurring patterns within textual data. Unlike mere descriptive summaries, thematic analysis enables deeper analytical engagement by revealing underlying conceptual links between corruption and governance fragility, thereby ensuring that the study’s findings are not only theoretically sound but also practically relevant to governance discourses (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

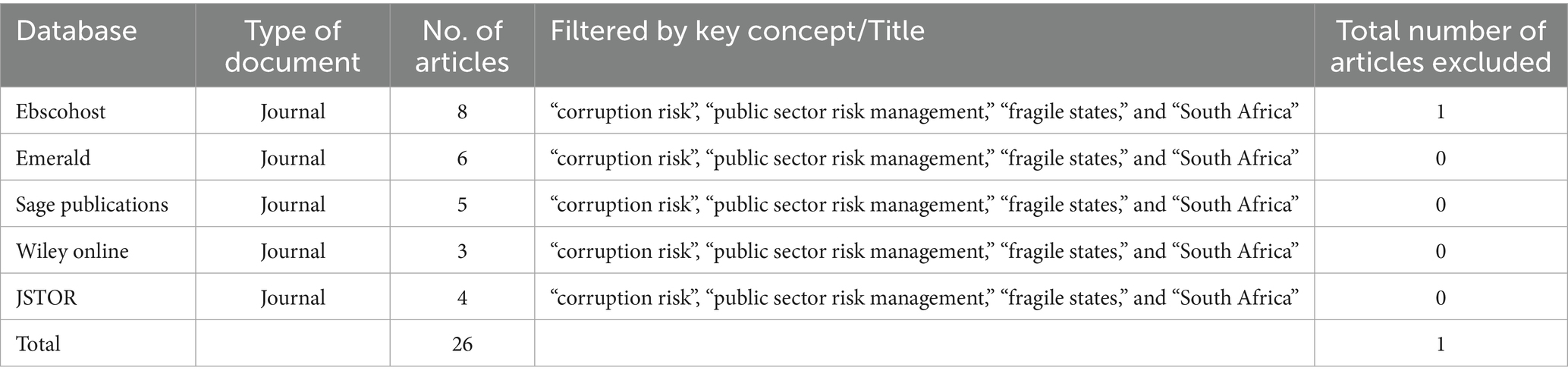

The research process followed a multi-phase approach. The initial stage involved an extensive literature search conducted through several reputable and credible scholarly databases, including Taylor & Francis, Elsevier, EBSCO, Sage, JSTOR, ProQuest, and Wiley Online Library. To refine the search process, keywords such as “corruption risk,” “public sector risk management,” “fragile states,” and “South Africa” were applied using Boolean search operations. The inclusion criteria were carefully restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles, books, institutional reports, and policy documents published between 2015 and 2023. To ensure relevance and robustness, the literature review focused on research within the disciplines of political science, economics, criminology, law, public management/administration, and interdisciplinary social sciences, which provide the most pertinent theoretical and empirical perspectives on corruption and state fragility (Maguire and Delahunt, 2017; OECD, 2020) (see Table 1).

Table 1 illustrates the initial literature search yielding a total of 26 studies. To enhance the relevance of the study, a critical appraisal of these sources was conducted through a systematic examination of abstracts, introductions, and conclusions. This appraisal aimed at evaluating the relevance of each study to the specific topic of corruption dynamics in fragile states, public sector governance risks, and institutional resilience. Studies that did not adequately address these keywords were excluded from the final analysis, resulting in 25 sources. Exclusion criteria applied during this process included studies published before 2015, articles that fell outside the relevant disciplines, studies focusing on corruption unrelated to governance or institutional resilience, and publications that did not provide empirical or theoretical contributions relevant to the South African context.

For data synthesis and interpretation, the study employed thematic analysis, a qualitative methodology that allows for the identification of recurring patterns and themes within the selected literature. Following the analytical framework for thematic analysis proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006), the thematic analysis was conducted through several steps, which included familiarization, coding, theme identification, reviewing and refining themes, and defining and naming themes. The familiarization process involved reading and re-reading the selected studies to gain a thorough understanding of the data. Coding was performed systematically, with attention to theoretical constructions, governance frameworks, and corruption risk resilience mechanisms. During the theme identification stage, related codes were grouped into overarching themes that captured significant patterns and conceptual linkages. The themes were then reviewed and refined to ensure coherence and relevance to the research objectives, followed by a final step of defining and naming themes to articulate their significance.

The thematic analysis process revealed four dominant themes relevant to the research objectives: corruption in procurement processes, compliance and risk management gaps, accountability mechanisms and enforcement deficiencies, and crisis vulnerabilities and institutional fragility. The theme concerning corruption in procurement processes highlighted how governance failures within procurement frameworks facilitate corruption risk migration. The compliance and risk management gap’s theme underscores in policy implementation and weak accountability frameworks. The accountability mechanism’s theme exposed institutional weaknesses in oversight and enforcement, while the crisis vulnerability’s theme demonstrated how emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbate corruption risks by revealing structural weaknesses.

The integration of conceptual analysis and thematic analysis offers a methodologically sound and analytically rigorous examination of corruption risk as a structural driver of state fragility. This approach enhances the validity of the research findings and contributes to the broader discourse on governance, risk management, and anti-corruption strategies in fragile states. It also provides a valuable framework for understanding the complex interactions between corruption risk, governance processes, and institutional resilience.

3 Literature review

3.1 Corruption risk and state fragility in Africa

Across the African continent, the relationship between corruption and state fragility is well-documented. Countries scoring poorly on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) and the Fragile States Index (FSI) such as South Sudan, Sudan, and the DRC, are plagued by weak institutions, elite capture, and regulatory failure (Transparency International, 2025). In contrast, countries like Botswana and Rwanda, with relatively lower corruption levels, exhibit greater institutional resilience. The correlation is especially strong where patronage systems and rent-seeking behaviors supplant the rule of law and distort development priorities (Mungiu-Pippidi, 2017; North et al., 2009).

Corruption undermines not only economic development through mismanagement of public funds and diversion of resources from sectors like health and education—but also public trust. As government officials evade accountability and engage in bribery and preferential contracting, citizens respond with protest, disengagement, and in some cases, rebellion (OECD, 2020). Civil unrest in fragile states such as Somalia, South Sudan, and the DRC further illustrates how governance failures fed by corruption generate cascading political and humanitarian crises (World Bank, 2022). South Africa mirrors this trend. Despite a sophisticated anti-corruption legal framework, ongoing scandals and regulatory breakdowns point to corruption’s deep structural roots. The country’s experience suggests that corruption is not just an enforcement issue but a fundamental driver of state fragility (Chipkin and Swilling, 2018; Vyas-Doorgapersad, 2024). A critical connection can be drawn between the structural risks of corruption and the neopatrimonialism character of many African governance systems, wherein informal networks and hybrid authorities reinforce the very fragility they are expected to mitigate.

Neopatrimonialism is one of the most enduring frameworks for understanding corruption in African governance. Bratton and van de Walle (1997) argue that many African states exhibit a dual logic of authority: formal bureaucratic institutions coexist with informal patron-client networks. This hybrid governance system often facilitates corruption by allowing rulers to distribute rents to political allies while maintaining the façade of legal-rational authority. In fragile states, the dominance of informal networks means that anti-corruption laws are selectively enforced or entirely ignored. The role of international actors in addressing corruption and fragility in Africa is deeply contested. On the one hand, multilateral organizations like the African Union, World Bank, and UNDP have supported anti-corruption frameworks and capacity-building initiatives. The African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption (AUCPCC, 2003) and the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) represent regionally owned responses to corruption. On the other hand, scholars such as Mungiu-Pippidi (2015) and Booth (2012) argue that donor interventions often fail to account for the political settlement dynamics within recipient countries. Technical solutions such as anti-corruption agencies or transparency portals may improve indicators but do little to alter the power structures that enable corruption. In some cases, foreign aid itself becomes a source of corruption when it is channelled through unaccountable state structures or siphoned off by ruling elites.

Comparative studies provide valuable insights into how corruption contributes to fragility across different African contexts. Each country presents a distinct configuration of political institutions, historical legacies, and governance capacities, shaping the manifestation of corruption and its consequences for state resilience. South Sudan remains one of the most illustrative cases of how corruption entrenches state failure (Mkhize et al., 2024). Since its independence in 2011, the political elite has siphoned off billions of dollars from oil revenues while state institutions remain largely dysfunctional (De Waal, 2014). Efforts at building bureaucratic systems have been continuously undermined by ethnicized patronage and elite competition over resources, exacerbating the country’s chronic instability and humanitarian crises.

Botswana, in contrast, is regularly cited as a model of integrity on the continent (see Omotoye and Holtzhausen, 2024; Jones, 2017). It has historically maintained a strong public sector ethos, transparent mineral governance, and independent institutions such as the Directorate on Corruption and Economic Crime (DCEC). Its success has been attributed to early state-building efforts, elite consensus around the rule of law, and a relatively small, cohesive political class (Acemoglu et al., 2003; South Africa Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), 2021). Nigeria offers a complex case of democratic fragility underpinned by systemic corruption. Despite significant oil wealth and the creation of dedicated institutions like the EFCC and ICPC, political interference and a weak judiciary have consistently undermined enforcement efforts. The “petro-state” dynamic has reinforced rentierism, enabled electoral malpractice, and deepened regional inequalities, especially in the Niger Delta where oil theft and environmental degradation reflect the governance vacuum (Ibeanu, 2008; Ukeje, 2011). Zimbabwe highlights how state-led corruption can destroy both economic and institutional stability. The land reform program, while addressing historical injustice, was implemented through clientelist mechanisms that benefitted political elites. Simultaneously, the misuse of diamond revenues in Marange and extensive patronage networks have hollowed out public institutions, contributing to economic collapse, hyperinflation, and mass migration (Raftopoulos, 2009; Sachikonye, 2011).

Kenya represents a case of recurrent reform attempts thwarted by entrenched corruption networks. Scandals such as the Goldenberg and Anglo Leasing affairs underscore how grand corruption persists despite constitutional reforms and a vibrant civil society. The 2010 Constitution introduced a devolved governance system, but corruption has since migrated to county governments, raising questions about local elite capture (Kramon and Posner, 2011; Cheeseman et al., 2016). Rwanda, meanwhile, presents a hybrid model of authoritarian developmentalism, where corruption is tightly controlled from above, but political freedoms are restricted (Friedman, 2011). The government’s Imihigo performance contracts and zero-tolerance policy have delivered relative success in curbing bureaucratic corruption. However, critics argue that the absence of media freedom and civic space limits long-term democratic accountability (Golooba-Mutebi, 2008; Chemouni, 2014).

These comparative experiences underscore that anti-corruption success in fragile states depends on context-specific factors including political will, institutional independence, historical trajectories, and the ability to insulate reform processes from vested interests. They also reveal that one-size-fits-all solutions are ineffective, and that strategies must be embedded within broader governance and development frameworks. In Zimbabwe, the erosion of judicial independence and land governance institutions has facilitated high-level corruption while simultaneously accelerating economic collapse and citizen outmigration. Meanwhile, Nigeria’s experience with anti-corruption reform shows that without prosecutorial independence and judicial efficiency, even well-funded institutions like Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) struggle to deliver sustainable results (Akinola, 2019). Furthermore, traditional and religious authorities often exercise substantial influence, especially in rural or peri-urban areas where state presence is weak. These actors may act as alternative sources of legitimacy but can also contribute to corruption if they collude with political elites or engage in unregulated dispute resolution (Logan, 2009). The resulting fragmentation of authority complicates efforts to build coherent and accountable state institutions.

Comparative analysis of these cases reveals a continuum of corruption’s impact on state integrity. On one end, in cases like South Sudan, corruption is so systemically destructive that it directly fuels conflict and collapse; in the middle, cases like Nigeria, Kenya, and Zimbabwe suffer serious governance deficits and episodic crises due to entrenched corruption, yet muddle through with partial functionality; and on the other end, cases like Rwanda and Botswana manage to contain corruption’s worst effects, resulting in more resilient governance. The differences often stem from historical and structural factors: colonial legacies, leadership choices, the presence (or absence) of abundant natural resources, ethnic power balances, and external influences (such as donor pressure or sanctions) all shape how corruption is practiced and constrained. Importantly, the role of political will and leadership comes up repeatedly—where leaders decisively set norms against graft (Botswana, Rwanda), corruption has been checked; where leaders themselves are drivers of corruption (South Sudan’s warlords, Zimbabwe’s party bosses, Nigeria’s powerbrokers), institutions have faltered. Yet even Rwanda and Botswana had advantages—a relatively cohesive national identity or small elite circles—that enabled a break from the patrimonial mold. The broader lesson is that while corruption is systemic, it is not monolithic: it adapts to its environment. Understanding those nuances is crucial for any reconceptualization of corruption, as one-size-fits-all theories or solutions often misfire in the face of such complexity.

3.2 Corruption as a governance disorder and its causal link to fragility

Conventional approaches frame corruption as an administrative infraction or economic inefficiency (Rose-Ackerman and Palifka, 2016), yet such perspectives neglect its structural entrenchment. In fragile contexts, corruption is a mechanism for elite power consolidation, not a deviation from governance norms (Fukuyama, 2018; Khan et al., 2017). Rather than a technical risk, it functions as a governance disorder embedded in institutional networks resistant to reform (Marquette and Peiffer, 2018; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2017). A system-thinking approach reveals corruption’s feedback loops within governance structures, how it reinforces institutional erosion, undermines reform initiatives, and perpetuates instability. This analytical shift is essential to understanding why anti-corruption strategies in fragile states consistently underperform despite robust legal infrastructures.

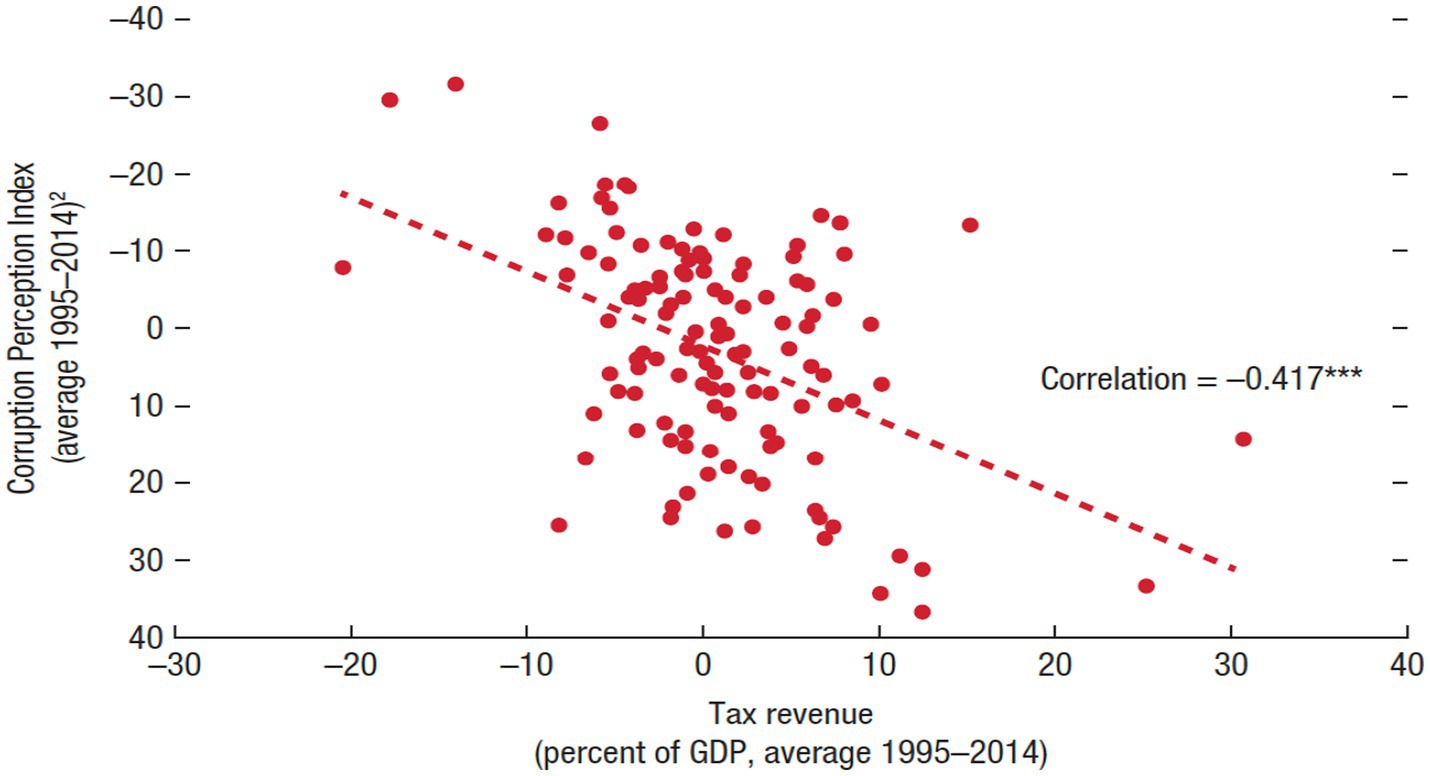

The connection between corruption and fragility is not merely associative but causal. In fragile states, corruption serves as a tool for elite enrichment, political control, and institutional weakening (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012; Rotberg, 2019). According to GiZ (2020), fragile states are distinct political environments where weakened governance, corruption, and insecurity halt development processes entirely. Corruption’s economic and social consequences are severe: reduced tax revenues, underinvestment in public services, and deepening inequality (IMF, 2019; Hammadi et al., 2019). Sub-Saharan Africa, where half of the lowest-ranking countries on the CPI reside, remains especially affected. Fragility is perpetuated by unequal development, weak institutional autonomy, and exclusionary politics, which foster economic vulnerability and cyclical instability GiZ (2020). Figures from the IMF (2019) and World Bank (2021) show a direct inverse relationship between corruption and tax revenue mobilisation. In high-corruption settings, tax bases shrink, undermining fiscal capacity and increasing reliance on debt or aid. Fragile states, particularly in Africa, remain trapped in this cycle, with many experiencing more than a decade of entrenched fragility. Cilliers and Sisk (2013) estimate that escaping such fragility requires at least 25 years of consistent governance and development reform—an outcome rarely achieved due to the complexity of corruption’s integration into state systems. Figure 1 illustrates the inverse relationship between perceived corruption and tax revenue as a percentage of GDP, using data from Transparency International (2020a, 2020b) and IMF (2019). Countries with high corruption levels experience lower tax collection and fiscal capacity, limiting public investment and increasing state fragility.

Figure 1. Corruption and tax revenue mobilisation in fragile states. Source: IMF (2019).

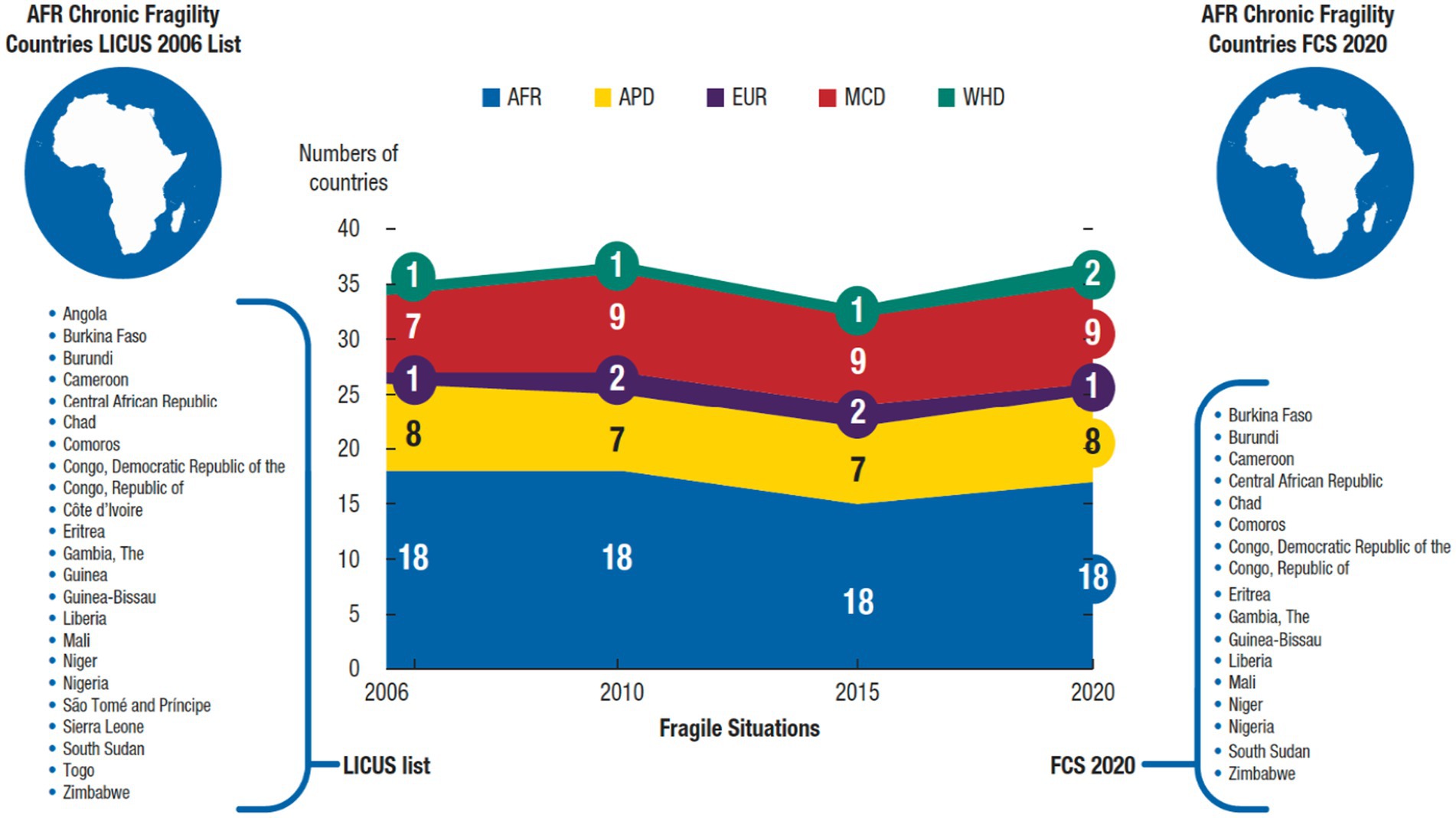

Furthermore, based on World Bank (2021) data, Figure 2 demonstrates the regional distribution of fragile states, highlighting Sub-Saharan Africa as the region with the highest concentration of long-term fragile states.

Figure 2. Regional breakdown of Fragile States (2006–2020). Source: World Bank (2021).

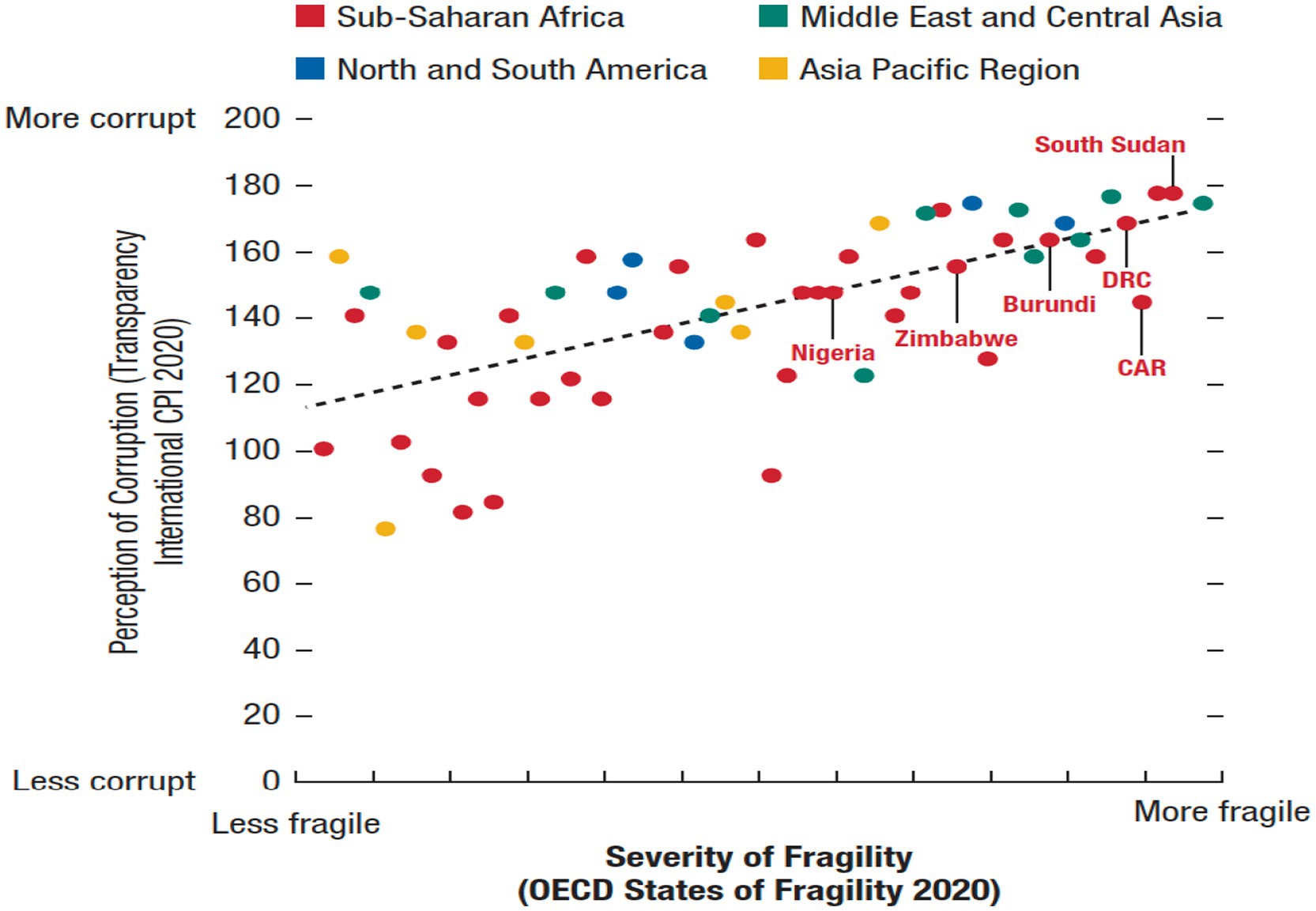

Furthermore, Figure 3 correlates CPI scores and FSI rankings for African countries, showing a strong relationship between high perceived corruption and elevated fragility metrics (OECD, 2020; Transparency International, 2020a, 2020b).

Figure 3. Corruption perceptions vs. fragility index scores. Source: Transparency International (2020b); OECD (2020).

4 Corruption risk and governance fragility in South Africa

South Africa exemplifies how corruption can evolve into a systemic threat to governance. Despite progressive institutional reforms and constitutional safeguards, post-apartheid efforts have been undermined by elite networks, regulatory capture, and administrative inefficiencies (Chipkin and Swilling, 2018; Mkhize et al., 2024). Corruption has led to institutional hollowing, with merit-based appointments often replaced by politically motivated selections. This has produced policy incoherence, service delivery failures, and parallel structures of decision-making. Critical sectors such as health, infrastructure, education, suffer from resource misallocation and embezzlement, further exacerbating inequality and stagnation (Fukuyama, 2014; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2017). Political legitimacy is eroding as public trust declines. Scandals such as state capture and COVID-19 fund mismanagement illustrate how repeated ethical breaches foster disillusionment and civil unrest (Vyas-Doorgapersad, 2024). Oversight institutions such as the NPA and SIU, while constitutionally mandated, are frequently hampered by political interference and underfunding, perpetuating a culture of impunity. The Zondo Commission revealed the scale of elite corruption in sectors like energy and transport, with extensive regulatory gaps enabling fraud and financial mismanagement (Zondo, 2022). Addressing these issues requires more than legal reform; it necessitates a transformation of the political economy and the restoration of institutional autonomy.

4.1 The corruption-fragility cycle

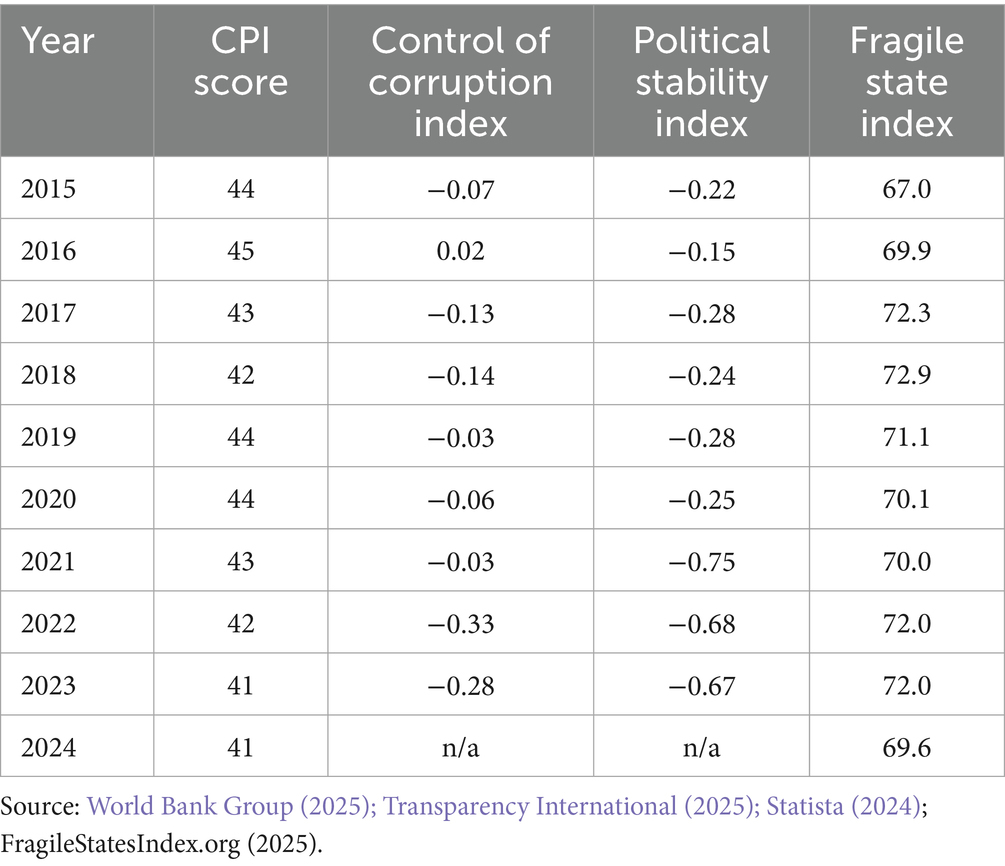

South Africa’s corruption crisis has created a feedback loop where governance failures fuel economic decline and social unrest, which in turn weaken institutions further. Table 2 shows a steady decline in governance indicators such as the CPI and World Bank’s Control of Corruption index. The Fragile States Index underscores this vulnerability, showing consistent fragility across metrics like state legitimacy and rule of law. These governance metrics highlight the structural nature of corruption in South Africa and its direct link to increasing state fragility. Addressing this requires institutional independence, rigorous oversight, and depoliticized public administration. The Corruption Perception Index (CPI), compiled by Transparency International, measures perceived levels of corruption in the public sector. South Africa’s CPI score has fluctuated between 41 and 45, reflecting persistent corruption concerns. A steady decline in the World Governance Indicator for control of corruption signals weakening institutional safeguards against corrupt activities. Simultaneously, the Political Stability Index demonstrates an increasing trend of governance fragility, with frequent protests and rising dissatisfaction over government inefficiency. In addition, the Fragile State Index indicates is a score that ranges from 0 (low) to 120 (high) (Fragile States Index, 2025). A lower score indicates a country is less fragile, while a higher score indicates greater instability. The FSI is based on 12 indicators that measure a country’s condition at a given time (Fragile States Index, 2025). These indicators include public services, human rights and rule of law, and state legitimacy. These three indexes as well as their indicators highlight the structural nature of corruption in South Africa and its direct link to state fragility.

5 Discussion of findings

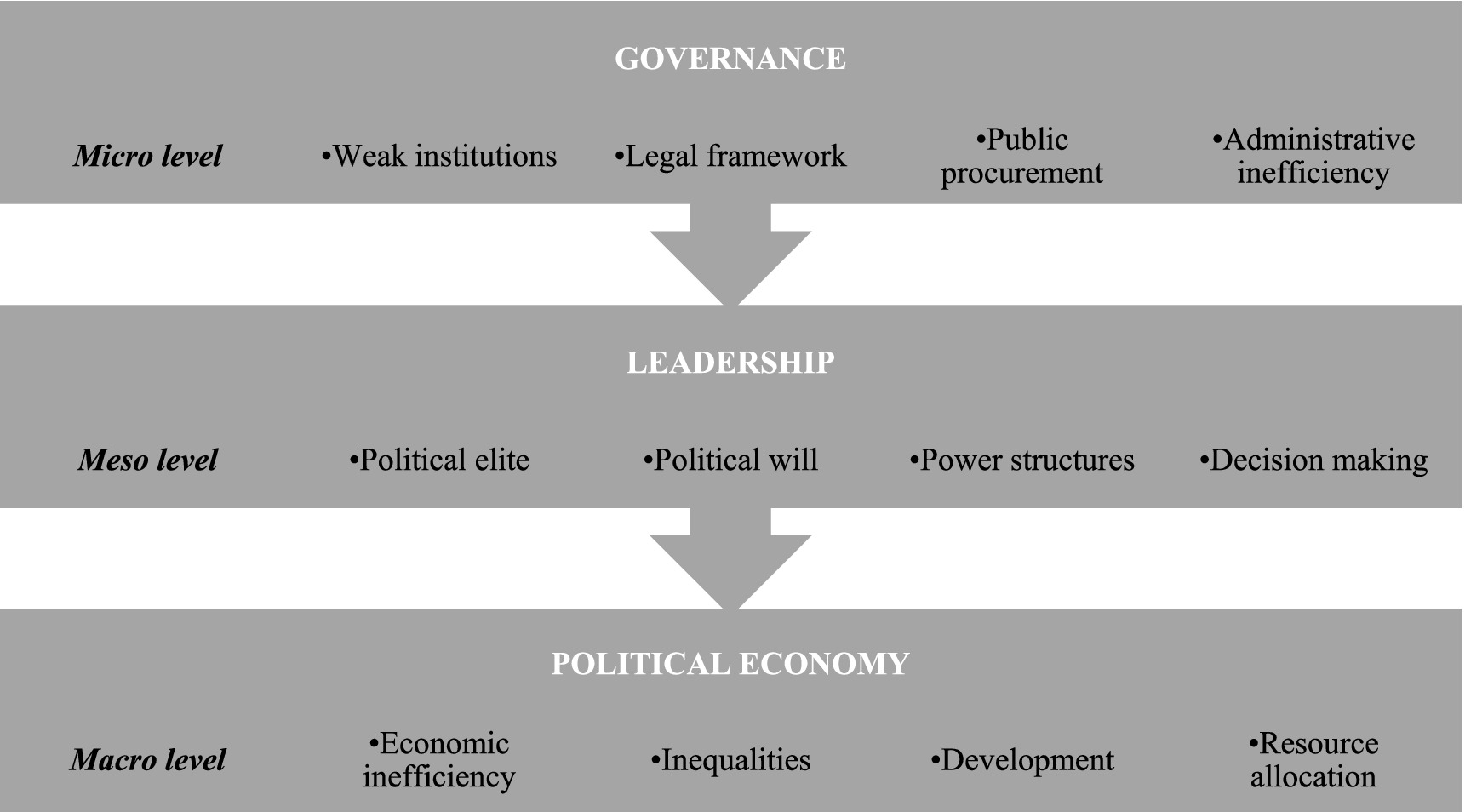

Figure 4 illustrates the themes identified during the thematic analysis, these themes underpin and contribute to the systemic nature corruption risk.

The results from the thematic analysis reveal that corruption can indeed be classified as a systemic risk. Three main themes were identified, namely: governance, leadership and political economy, with several sub-themes. This is relevant to the micro, meso and macro level analysis of a country. Furthermore, the reconceptualized view of corruption as systemic can be applied to contemporary South Africa, which is the focal point for illustrating how entrenched corruption undermines even relatively strong states. South Africa has long been regarded as one of the more institutionalized states in Africa—it boasts a well-developed legal framework, a robust constitution, and historically effective public agencies. Yet, in the past decade, the country has experienced what has been termed “state capture”: a phenomenon whereby a network of political and business elites, centered around former President Jacob Zuma and the Gupta family, effectively subverted key institutions for private gain (David-Barrett et al., 2023). The Zondo Commission (2018–2022), a sweeping inquiry into these events, laid bare how deeply systemic the corruption was (PARI, 2022). The findings showed that the state capturers were able to (i) install loyalists (or “willing collaborators”) in strategic positions across the bureaucracy and state-owned enterprises, (ii) cripple anti-corruption bodies and law enforcement agencies—even turning some into accomplices, (iii) weaken the checks and balances of democracy, for instance by neutering parliamentary oversight, and (iv) even influence independent media to shape the narrative. In essence, every pillar of governance was targeted. This was not random corruption by rogue officials; it was a coordinated strategy from the apex of power to repurpose the state’s machinery for factional benefit. The South African experience thus powerfully underscores the review’s central argument: corruption must be seen as a systemic risk to governance.

The political channel of erosion was evident as partisan patronage networks (through the ruling ANC’s cadre deployment system) took precedence over merit, thereby undermining the impartiality of institutions. Agencies meant to check executive power (such as the police’s Hawks unit, prosecutorial authorities, and parliamentary committees) were deliberately hobbled or co-opted, erasing the accountability mechanisms that normally safeguard institutional resilience. Through economic channels, massive resources were diverted: public procurement budgets of big state entities like Eskom (electricity utility), Transnet (rail and ports), and others became cash cows for the connected few. The consequence was not only financial loss but also a tangible decline in public services (e.g., recurrent electricity blackouts due in part to looted and mismanaged Eskom contracts) and a dent in investor confidence affecting growth and employment. Meanwhile, the administrative channel of state functioning deteriorated as skilled professionals in the civil service were sidelined or pushed out to make way for cronies, leading to what some analysts call a “hollowed-out” state. Even where good policies existed on paper, implementation faltered because institutions had been stripped of competence and integrity. South Africa, once a model of robust institutions in Africa, saw its institutional resilience tested by these dynamics: the very endurance of its democracy came into question as corruption eroded the rule of law and public trust. However, South Africa’s case also demonstrates a degree of resilience that aligns with the comparative lessons above. Its active media, independent judiciary, and vocal civil society eventually pressured the system to respond—hence the establishment of the Zondo Commission and a public reckoning with state capture. This response illustrates that systemic corruption, while deeply damaging, can be confronted if enough countervailing forces within society and the state mobilize.

The ongoing challenge is translating the commission’s findings into reforms. Recognizing corruption’s systemic nature, the remedies being considered go beyond prosecuting individuals; they include structural changes like insulating key institutions from political interference, strengthening parliamentary oversight, and even proposals for a permanent anti-corruption agency with constitutional status. The study’s reconceptualization of corruption provides the intellectual backing for such measures: if corruption operates through political, economic, and administrative channels, then bolstering each of those channels against capture is vital for restoring institutional integrity. In the South African context, this means reasserting a rules-based governance system where accountability is real, procurement processes are transparent, and meritocracy trumps patronage in public appointments. It is an arduous undertaking, but it reaffirms the idea that state resilience is a function of institutional quality—and that quality in turn hinges on controlling corruption. In summary, viewing corruption as a structural driver of state fragility rather than a peripheral failing leads to a more nuanced and critical understanding of Africa’s governance challenges. The comparative cases show that while the expression of corruption varies—from South Sudan’s warlordism to Botswana’s relative probity—the essence of the problem is a political one: the absence of inclusive, accountable systems to manage power and resources. Dominant paradigms that neglect this systemic character are ill-equipped to explain why conventional reforms often do not stick.

By reconceptualizing corruption as part of the very system of governance (a lens that accounts for neopatrimonialism ties, patronage politics, and the political economy of rents), scholars and practitioners can better identify levers of change. This discussion has illustrated that approach by examining how corruption has undermined institutional resilience through multiple channels, culminating in the case of South Africa’s state capture. The insights reinforce a core message: combating corruption in fragile states is not just a technical endeavor but a profoundly political one. Any serious anti-corruption strategy must therefore engage with the distribution of power in society—challenging the vested interests that benefit from the status quo and empowering the constituencies (within the state and outside it) that demand transparency and rule of law. Only by addressing corruption’s systemic roots can African states strengthen their institutions and escape the trap of fragility that has too often plagued the post-colonial era.

6 Conclusion and study limitations

This study highlights the pervasive impact of corruption on state fragility, demonstrating that corruption is both a symptom and a driver of governance failure. The findings underscore how corruption weakens institutions, and erodes political legitimacy, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that exacerbates governance instability. By analyzing the South African case, this research situates corruption as a systemic disorder rather than an isolated administrative issue, calling for a reconceptualization of anti-corruption strategies that prioritize institutional resilience, economic diversification, and strengthened accountability mechanisms. Addressing corruption in fragile states like South Africa requires a multi-faceted policy approach that acknowledges the systemic and interdependent nature of governance challenges. Institutional reform must be prioritized to strengthen judicial independence, enhance transparency in public procurement, and establish robust oversight mechanisms to prevent political interference. Strengthening anti-corruption agencies and equipping them with greater autonomy, legal backing, and financial resources will also be critical in curbing corruption at higher levels of governance. In addition, the enforcement of whistleblower protection laws and the promotion of civic engagement can play a fundamental role in encouraging public accountability and participation in governance reforms.

From a practical governance perspective, economic diversification strategies should be emphasized to reduce the monopolization of industries by politically connected elites. Encouraging private sector transparency through the adoption of anti-corruption compliance frameworks in corporate governance will also reduce rent-seeking behaviors and illicit financial flows. Furthermore, enhancing public financial management through digital tracking mechanisms can curb fiscal mismanagement, ensuring that government spending aligns with development priorities rather than personal enrichment schemes. On the international front, cross-border cooperation on financial intelligence sharing and asset recovery efforts will strengthen South Africa’s capacity to combat illicit financial activities linked to corruption. Development partners and multilateral institutions must support local governance reforms by aligning financial aid with stringent anti-corruption measures, thus reinforcing institutional integrity in fragile state environments.

The study also contributes to the broader literature on governance and risk management by offering a nuanced understanding of how corruption perpetuates fragility, particularly in politically unstable environments. Future research should explore the potential of adaptive governance models that emphasize transparency, citizen participation, and independent oversight to mitigate corruption risks. As corruption remains one of the most pressing threats to sustainable governance in fragile states, addressing it effectively is imperative for fostering long-term stability and development in South Africa and beyond. In conclusion, breaking the corruption-fragility cycle necessitates a shift in governance paradigms, where reforms are not merely punitive but systemic and preventive, aimed at ensuring long-term resilience. Without decisive action, South Africa risks deeper governance failures, worsening economic stagnation, and the further erosion of public trust in state institutions. Tackling corruption must therefore be viewed as an essential prerequisite for achieving sustainable governance, equitable development, and political stability in fragile states.

This study adopts a conceptual analysis approach to examine the relationship between corruption and state fragility, which, while valuable for theoretical exploration, limits the establishment of causal inferences. The absence of empirical fieldwork restricts the generalizability and contextual specificity of the findings. Additionally, the exclusive reliance on secondary sources—such as academic literature and governance indices like the CPI and FSI—may omit recent developments and localised dynamics not reflected in published data. Furthermore, the time-bound nature of these indices may not adequately capture the evolving and complex realities of corruption and governance in fragile state contexts.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

NM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DN-S: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., and Robinson, J. A. (2003). “An African success story: Botswana” in In search of prosperity: Analytic narratives on economic growth. ed. D. Rodrik (Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Princeton University Press), 80–119.

Acemoglu, D., and Robinson, J. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity and poverty. New York: Crown.

Akinola, A. O. (2019). Anti-corruption reforms and democratic consolidation in Nigeria. J. Afr. Elections 18, 88–109.

AUCPCC. (2003). African union convention on preventing and combating corruption. Available at: https://au.int/en/treaties/african-union-convention-preventing-and-combating-corruption (Accessed January 23, 2025).

Booth, D. (2012). Development as a collective action problem: Addressing the real challenges of African governance : London, United Kingdom: Overseas Development Institute.

Bratton, M., and van de Walle, N. (1997). Democratic experiments in Africa: Regime transitions in comparative perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cheeseman, N., Lynch, G., and Willis, J. (2016). Decentralisation in Kenya: the governance of governors. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 54, 1–35. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X1500097X

Chemouni, B. (2014). Explaining the design of the Rwandan decentralization: elite vulnerability and the territorial repartition of power. J. East. Afr. Stud. 8, 246–262. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2014.891800

Chipkin, I., and Swilling, M. (2018). Shadow state: The politics of state capture. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Cilliers, J., and Sisk, T. (2013). Assessing long-term state fragility in Africa: prospects for 26 ‘more fragile’ countries. ISS Monograph No. 188. doi: 10.2139/SSRN.2690234

David-Barrett, E., Kaufman, D., and Ceballos, J. C. (2023). Measuring state capture. Austria: International Anti-Corruption Academy (IACA).

De Waal, A. (2014). When kleptocracy becomes insolvent: brute causes of the civil war in South Sudan. Afr. Aff. 113, 347–369. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adu028

Fragile States Index. (2025). Indicators. Available at: https://fragilestatesindex.org/indicators/ (Accessed May 30, 2025).

Friedman, A. (2011). Kagame’s Rwanda: can an authoritarian development model be squared with democracy and human rights? Oregon Rev. Int. Law. 14, 253–278. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1947111

Fukuyama, F. (2014). Political order and political decay: From the industrial revolution to the globalization of democracy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Fukuyama, F. (2018). “Corruption as a political phenomenon”, In Basu and Cordella (Eds.) Institutions, Governance and the Control of Corruption (pp. 209–251). New York, USA: Springer International Publishing.

GiZ,. (2020). Evaluation report - 2020: Using knowledge. Available at: https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/giz2021_en_GIZ-Evaluation%20report%202020_USING%20KNOWLEDGE_.pdf (Accessed May 22, 2025).

Golooba-Mutebi, F. (2008). Collapse, war and reconstruction in Rwanda: An analytical narrative on state-making. London School of Economics, Crisis States Research Centre.

Hammadi, A., Mills, M., Sobrinho, N., Thakoor, V., and Velloso, V. (2019). A Governance Dividend for Sub-Saharan Africa?. IMF Working Paper WP/19/1.

Ibeanu, O. (2008). Affluence and affliction: The Niger Delta as a critique of political science in Nigeria. Inaugural Lecture Series No. 18. University of Nigeria Press.

Jones, D. S. (2017). Combating corruption in Botswana: lessons for policy makers. Asian Education and Development Studies. 6, 213–226. doi: 10.1108/AEDS-03-2017-0029

Khan, M., Andreoni, A., and Roy, P. (2017). Anti-Corruption in Adverse Contexts: A Strategic Approach. Working Paper. London.

Kramon, E., and Posner, D. N. (2011). Kenya’s new constitution. J. Democr. 22, 89–103. doi: 10.1353/jod.2011.0026

Logan, C. (2009). Selected chiefs elected councillors and hybrid democrats: popular perspectives on the co-existence of democracy and traditional authority in Ghana. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 47, 101–128. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X08003674

Maguire, M., and Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: a practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISHE-J 8, 3351–33514.

Marquette, H., and Peiffer, C. (2018). Grappling with the “real politics” of systemic corruption: theoretical debates versus “real-world” functions. Governance 31, 499–514. doi: 10.1111/gove.12311

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mkhize, N. E., Moyo, S., and Mahoa, S. (2024). African solutions to African problems: a narrative of corruption in postcolonial Africa. Cogent. Soc. Sci. 10, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2024.2327133

Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2015). The quest for Good governance: How societies develop control of corruption. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2017). Corruption as social order. World development report 2017, background paper. Washington, DC: World Bank.

North, D. C., Wallis, J. J., and Weingast, B. R. (2009). Violence and social orders: A conceptual framework for interpreting recorded human history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Omotoye, A. M., and Holtzhausen, N. (2024). Integration of digital technologies in anti-corruption initiatives in Botswana: lessons from Georgia, Ukraine and South Africa. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy. 19, 22–36. doi: 10.1108/TG-01-2024-0002

OECD, J. A. (2020). OECD Public Integrity Handbook. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1787/ac8ed8e8-en

PARI. (2022). The Zondo Commission: a bite-sized summary. Available at: https://pari.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/PARI-Summary-The-Zondo-Commission-A-bite-sized-summary-v360.pdf (Accessed January 13, 2025).

Raftopoulos, B. (2009). “The crisis in Zimbabwe, 1998–2008” in Becoming Zimbabwe: A history from the pre-colonial period to 2008. eds. B. Raftopoulos and A. Mlambo (Harare, Zimbabwe: Weaver Press), 201–232.

Rose-Ackerman, S., and Palifka, B. J. (2016). “Corruption and government: causes, consequences, and reform. 2nd Edition. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Rotberg, R. I. (2019). Corruption in Latin America: How politicians and corporations steal from citizens. New York: Springer International.

Rothstein, B. (2011). The quality of government: Corruption, social trust, and inequality in international perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sachikonye, L. M. (2011). When a state turns on its citizens: Institutionalized violence and political culture. Harare, Zimbabwe: Jacana Media.

South Africa Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA),. (2021). The big governance issues in Botswana a civil society submission to the African peer review mechanism. Available at: https://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/AGDP-BAPS-Report-BOTSWANA-March2021-FINAL-WEB.pdf (Accessed August 07, 2025).

Statista. (2024). Monthly share of people who are worried about financial and political corruption in South Africa from January 2022 to December 2024. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1266540/share-of-south-africans-worried-about-financial-and-political-corruption/ (Accessed February 21, 2025).

Transparency International. (2020a). Together against corruption: Transparency international strategy 2020. Available at: https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/TogetherAgainstCorruption_Strategy2020_EN.pdf

Transparency International. (2020b). Corruption perceptions index. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020

Transparency International. (2025). 2024 corruption perceptions index: corruption is playing a devastating role in the climate crisis. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/press/2024-corruption-perceptions-index-corruption-playing-devastating-role-climate-crisis (Accessed May 18, 2025).

Ukeje, C. (2011). “Oil, conflict and youth exclusion in the Niger Delta” in The transformation of Nigeria: Essays in honour of Toyin Falola. ed. A. Mustapha (Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press), 299–320.

Vyas-Doorgapersad, S. (2024). Corruption in South Africa: an ongoing challenge to good governance. Int. J. Bus. Ecosyst. Strategy 6, 453–462. doi: 10.36096/ijbes.v6i4.636

World Bank. (2021). Classification of fragile and conflict-affected situations. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence/brief/harmonized-list-of-fragile-situations.

World Bank. (2022). The World Bank in South Africa. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/southafrica/overview (Accessed May 24, 2025).

World Bank Group. (2025). Worldwide governance indicators. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?Report_Name=WGI-Table&Id=ceea4d8b. (Accessed May 24, 2025).

Keywords: systemic corruption risk, South Africa, fragile states, public sector risk management, corruption, governance

Citation: Mkhize N and Nel-Sanders D (2025) Corruption risk as a structural driver of state fragility: examining the governance crisis in South Africa. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1575693. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1575693

Edited by:

Oliver Fernando Hidalgo, University of Passau, GermanyReviewed by:

Roberta Troisi, University of Salerno, ItalyIonela Munteanu, Ovidius University, Romania

Copyright © 2025 Mkhize and Nel-Sanders. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nkosingiphile Mkhize, bmtvc2luZ2lwaGlsZS5lLm0xOEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Nkosingiphile Mkhize

Nkosingiphile Mkhize Danielle Nel-Sanders

Danielle Nel-Sanders