- School of Business, Social and Decision Sciences, Bremen, Germany

This article asks whether a unified framework can integrate established traits of populist leadership, propose novel ones, and link populist leaders to their social support. To do so, it uses Mary Douglas’s cultural theory, and especially its typology of four “ways of life” (hierarchy, egalitarianism, individualism and fatalism), in combination with Jan-Werner Müller’s definition of populism (as movements with leaders who claim to be the sole representatives of a homogenous people). This theoretical approach is illustrated through a congruence analysis of Donald J. Trump’s first presidency using secondary data. The analysis finds that the fatalistic way of life encapsulates populist leadership. All features of populist rule identified in the literature—such as corruption, nepotism, and protectionism—are consistent with fatalism. The framework also highlights additional traits (for instance, secretiveness, vengeance, and conspiracy-proneness) implied by fatalism. The Trump case exemplifies these arguments: his administration’s conspiratorial rhetoric, punitive governance style and zero-sum outlook reflect a fatalistic ethos. Crucially, cultural theory bridges leaders and followers: fatalism links the supply side of populism to its demand size. Overall, Douglas’s cultural theory unifies scattered populist traits under a coherent logic and provides a bridge between populist leadership and people’s support of such leadership. This integrated approach advances theoretical understanding of populist leadership while suggesting new avenues for empirical research.

Introduction

The resurgence of populist movements and parties in the last fifteen years initially caught the social sciences by surprise (Lamont, 2016). According to one influential definition (Müller, 2016a), such movements and parties claim the sole right to speak for a supposedly homogenous people, and as such are anti-pluralist and undemocratic. Their rise appeared to contradict leading social and political theories, such as democratic consolidation theory (Foa and Mounk, 2018) and neo-functionalism (Hooghe and Marks, 2019). Similarly, in the study of leadership, it was argued that influential typologies did not adequately capture the behavior and ideas of populist leaders (Foroughi et al., 2019). This criticism was for instance levelled at the two political leadership styles that Burns (1978) had proposed (Spector and Wilson, 2018). When distinguishing between “transactional” and “transformational” leadership styles, Burns (1978, p. 417) had argued that “Coercive strategies need not detain us here since we exclude coercion from the definition of leadership”—a premise maintained in later typologies influenced by Burns’ classification (such as Bass and Avolio, 1993; Pearce et al., 2003). This aversion to analyze coercive leadership has not been limited to research inspired by Burns. According to Kellerman (2004, p. 40): “Although a few authors have recently taken exception to the blind belief in the inherent goodness of leadership… most of the hugely successful scholars argue, often with passion, that effective leaders are persons of merit, or at least of good intentions. It almost seems that by definition bad people cannot be good leaders.” This unwillingness to consider power-wielding, deceit and coercion as possible facets of leadership has made it more difficult to dissect the resurgence of populist politicians.

Moreover, the rise of populism around the world has not abated in recent years. Contrary to assurances in academia and the media that “peak populism” had finally been scaled (e.g., Pinker, 2018, p. 451; Taylor, 2019), populist movements have continued to grow stronger (Wike et al., 2024)—notwithstanding a brief decline in popularity due to the inadequate response of several populist governments to the COVID-19 pandemic (Foa et al., 2022). The three most populous democracies—India, the United States and Indonesia—are currently led by populist politicians. In the European Parliament elections of 2024, populist parties garnered 36% of the total vote, or 4% more than in the previous round.

In reaction to populism’s return, a thousand research enterprises were launched. Between 2012 and 2024 the annual number of articles on the Web of Science database with the terms “populism” or “populist” in their titles increased more than fivefold. In the study of leadership, this renewed attention has resulted in the identification of various features of populist rule. For example, it has been shown that such leadership tends to be “personalistic” (Weyland, 2024), “corrupt” (Zhang, 2024), “protectionist” (Funke et al., 2023) and “narcissistic” (Nai and Martinez i Coma, 2019), among other features. Nevertheless, challenges remain. First, it is unclear whether, and if, how, these features are connected to each other or whether they just form a random list of behaviors and beliefs that populist rulers happen to display. Second, it is still to be determined whether other traits can be added to the list. Finally, it would be helpful if these features of the supply side of populism (i.e., the leadership of populist parties) could be linked to the demand side of populism (that is, the support for populism). Both sides appear necessary for a full explanation (Mols and Jetten, 2020).

In this paper, I assess the extent to which the theory of sociocultural viability (or, for short, cultural theory) pioneered by anthropologist Douglas can meet these three challenges. I focus on this approach for various reasons. First, the theory has already been advocated and applied in the study of leadership (Ellis, 1989; Grint, 2010; Grint, 2024; Wildavsky, 1989), though not yet in an analysis of populist leadership. Second, the theory has been used in analyses of social domains characterized by coercion and violence, i.e., practices not sufficiently captured by many influential typologies of leadership. For example, cultural theory has been employed to illuminate the functioning of slavery (Ellis, 1994), as well as the planning and execution of genocide (Verweij, 2011). Third, as I argue below, each of cultural theory’s central concepts—consisting of four alternative ways of organizing, perceiving, justifying and experiencing social relations—encompasses a range of beliefs, preferences and values as well as a distinct pattern of behavior. As such, the approach may in principle be able to rise to the first two challenges listed above, namely, to connect the cognitive and behavioral features of populist leadership that have been identified in the literature and to suggest additional traits. Fourth, cultural theory has recently been applied in an empirical analysis of what drives voters to support a populist candidate (Swedlow et al., 2024). Hence, if the theory can also be applied to populist leadership, then it may meet the third challenge listed above, i.e., to link the supply of, and demand for, populism. For these various reasons, it appears to make sense to consider whether the theory of sociocultural viability offers novel insights into populist leadership.

I build my argument as follows. First, I set out how populism can be understood, and which traits of populist leadership have thus far been identified. Thereafter, I describe a version of Douglas’s cultural analysis that accommodates a persistent criticism of the approach. Subsequently, I explain how this slightly revised version of cultural theory can reveal the invisible ties connecting many of the features of populist leadership that have been discovered, can add items to this list, and can link these features of the supply side of populism to the demand side. I then illustrate the argument with an analysis of the first presidency of Donald J. Trump (2016–2020). This empirical part constitutes a congruence analysis (Blatter, 2012), and is based on informal, but comprehensive, secondary research. Finally, I conclude by describing the empirical research that still need to be undertaken to fully test the argument.

Populist leadership

In this article, I adopt Müller’s (2016b) definition of populism. As mentioned above, according to Müller’s account, the leaders of populist parties assert that they are the sole legitimate representatives of the “real” people of their country. That is, populist politicians claim that only they can know who the real people are, what these people uniformly want, and how it can be delivered to them. They also claim that the real people have been hoodwinked by corrupt political, economic and cultural elites. Invariably, those who are designated by populists as the real people are but a segment of the population. Populists frequently accuse elites not only of having used their power to benefit themselves, but also of having unfairly favored those who do not belong to the real people. Thus, populist leaders and parties are anti-pluralist, and therefore undemocratic. Their rise to power is often followed by efforts to abolish or ignore constitutional checks and balances. Consequently, the ascendency of populism has eroded democracies around the globe (Benasaglio Berlucchi and Kellam, 2023; Muno and Pfeiffer, 2022). Müller’s understanding of populism overlaps with what other writers have labelled “authoritarian populism” (e.g., Elçi, 2024; Inglehart and Norris, 2017).

I make use of Müller’s conceptualization for several reasons. To start, it perceives populism as a form of discourse. According to Müller (2016b, p. 199): “The decisive criterion [for recognizing populism] is that there is a decided anti-pluralism in the discourse of the populists and that they always refer to the people as a clearly moral entity.”1 As a consequence, Müller’s conceptualization is compatible with other discursive understandings of populism (Poblete, 2015). This is helpful as Douglas’s cultural theory, with its emphasis on the social and linguistic construction of politics, lends itself well to a discursive analysis of politics (Thompson et al., 1999, p. 12; Hoppe, 2007). Moreover, understanding populism as discourse focuses attention on how such movements are created through political action and leadership. For instance, Miscoiu (2012, p. 63) describes populism as “a discursive register with a hegemonic vocation that is based on the exaltation of popular identification through the ideological articulation of the supposed characteristics of a community (the ‘People’) and the exclusion of otherness responsible for the incompleteness of the identity of this community.”2 Hence, a discursive approach emphasizes how the flourishing of populism requires the formulation and imposition of an exclusionary ideology, and therefore agency and leadership—the topic of this article. Finally, I have a normative reason for selecting Müller’s understanding. By definition, his understanding slaps the populist label only onto politicians who threaten to undermine democracy. Broader conceptualizations of populism also assign to the populist camp leaders who do not wish to harm democracy, such as the Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn or the former leader of the British Labour Party Jeremy Corbyn. This is for example the case for the influential one offered by Mudde (2004), according to which populist parties are illiberal (as they portray the people to be homogenous) but not necessarily undemocratic (as they represent perspectives ignored by the political and media elites, and as they do not claim to be the only legitimate spokespersons of the people). In comparison, Müller’s conceptualization is more restrictive and allows one to focus exclusively on the discourses dominated by politicians keen to curb democracy.

By now, numerous features of populist leadership have been identified. A first trait of populist leadership is corruption. Drawing on a dataset of 155 countries from 1960 to 2020, Zhang (2024) shows that populist leadership is associated with a substantial increase in especially executive corruption. This corruption often comes in the form of patronage (i.e., the illicit use of state resources to reward followers) (Pappas, 2019) and nepotism (the appointment of relatives or friends to positions of power they are not qualified for) (Weyland, 2022). Another feature of populist rule turns out to be protectionist economic policies. On the basis of a study of 51 populist presidents and prime ministers from 1900 to 2020, Funke et al. (2023, p. 32) conclude that such leaders tend to enact measures that shield domestic producers from foreign competition. Likewise, Destradi and Vüllers (2024) infer, from an analysis of voting in the United Nations General Assembly between 1975 and 2015, that populist leaders prefer a closed (to an open) world economy. A further characteristic is the spreading of conspiracy theories. Analyzing five populist leaders in total (namely, Hugo Chávez, Viktor Orbán, Róbert Fico, Donald Trump and Geert Wilders), Plenta (2020), Hameleers (2021) and Pirro and Taggart (2023) find that such leaders are heavily involved in the dissemination (and sometimes creation) of conspiracy theories. In addition, dishonesty appears to blight populist rule (Foroughi et al., 2019, pp. 145–146; Spector, 2020; Waisbord, 2018). This has been ascertained for populist leaders in Brazil (De Moraes, 2022), Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany and Poland (Kluknavská et al., 2024), as well as the United Kingdom and the United States (Lacatus and Meibauer, 2022). Populist rule is also invariably personalistic (Ostiguy, 2017; Viviani, 2023; Weyland, 2022). That is, populist leaders attempt to concentrate decision-making in their own hands. Moreover, they frequently engage in scapegoating of ethnic, religious, sexual or other minorities. They have for instance done so in Brazil, Czechia, Hungary, India, Slovakia, Turkey and the United States (Çinar et al., 2020; Grigoriadis and Işık Canpolat, 2024; Hloušek et al., 2024; de Kets Vries, 2020; Prasad, 2020).

Some scholars (Mazzarella, 2024; Pappas, 2016) have maintained that populist leaders are charismatic, i.e., have an extraordinary, personal appeal. But others have argued against this (Favero, 2023; McDonnell, 2016; Volk, 2023)—either on the grounds that the notion of charisma is not defined in a sufficiently clear manner to be meaningfully tested or because more precise operationalizations tend to define charismatic leadership similarly to populist leadership and thus lead to tautological reasoning. Hence, I do not include charisma among the general traits of populist leadership.

Disagreement has also reigned regarding populists’ foreign policies. Several authors conclude that, in combination with protectionist or mercantilist, economic policies, populist rulers have preferred realist foreign policies (Chryssogelos, 2023, p. 3; Giurlando, 2020, p. 253; Magcamit, 2017, 2020; Taş, 2022). Yet according to others (Destradi and Plagemann, 2019; Lammers and Onderco, 2020; Stengel et al., 2024), this is not sufficiently nuanced and more research needs to be undertaken. Perhaps one day future research will show differently, but for now the foreign policies of many populist leaders—with their emphasis on national sovereignty, lack of qualms about collaborating with despotic rulers, attunement to power, hostility towards human rights, aversion of international organizations, and opposition to a liberal, open world order—appear in sync with realism.

Finally, a set of personality traits of populist leaders has been highlighted, in addition to the institutional features listed above. With help of a dataset based on expert ratings for 152 candidates (including 33 populists) who competed in 73 elections worldwide, Nai and Martinez i Coma (2019) established that populist leaders score lower on agreeableness, emotional stability and conscientiousness, while they rate higher on extraversion, narcissism, psychopathy and Machiavellianism. As an institutional theory (Douglas, 1986), the theory of sociocultural viability has little, if anything, to say about the personalities of individuals, populist or not. But it has a lot to say about the institutional features of populist leadership. Douglasian cultural theory can show what links these features, can add features, and can connect all these to the support for populism. To show this, I first need to set out the theory.

Cultural theory: an update

In various publications Douglas (1970, 1978, 1982) derived cultural theory by reorganizing Durkheim’s work. From The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (Durkheim, 1995), Douglas took two assumptions. The first states that the ways in which people interact shape (and are shaped by) the ways in which they perceive and justify their (inter)actions. These perceptions include views of nature, human nature, risk, technology, justice, time and space, etc. Durkheim had grouped these shared perceptions under the term “collective consciousness”, but Douglas preferred the label “cultural bias”. The second assumption Douglas appropriated from this book was the idea that a limited set of “elementary” ways of organizing, perceiving and justifying social relations underlies (and produces) the vast social and cultural diversity across time and space characterizing human life.

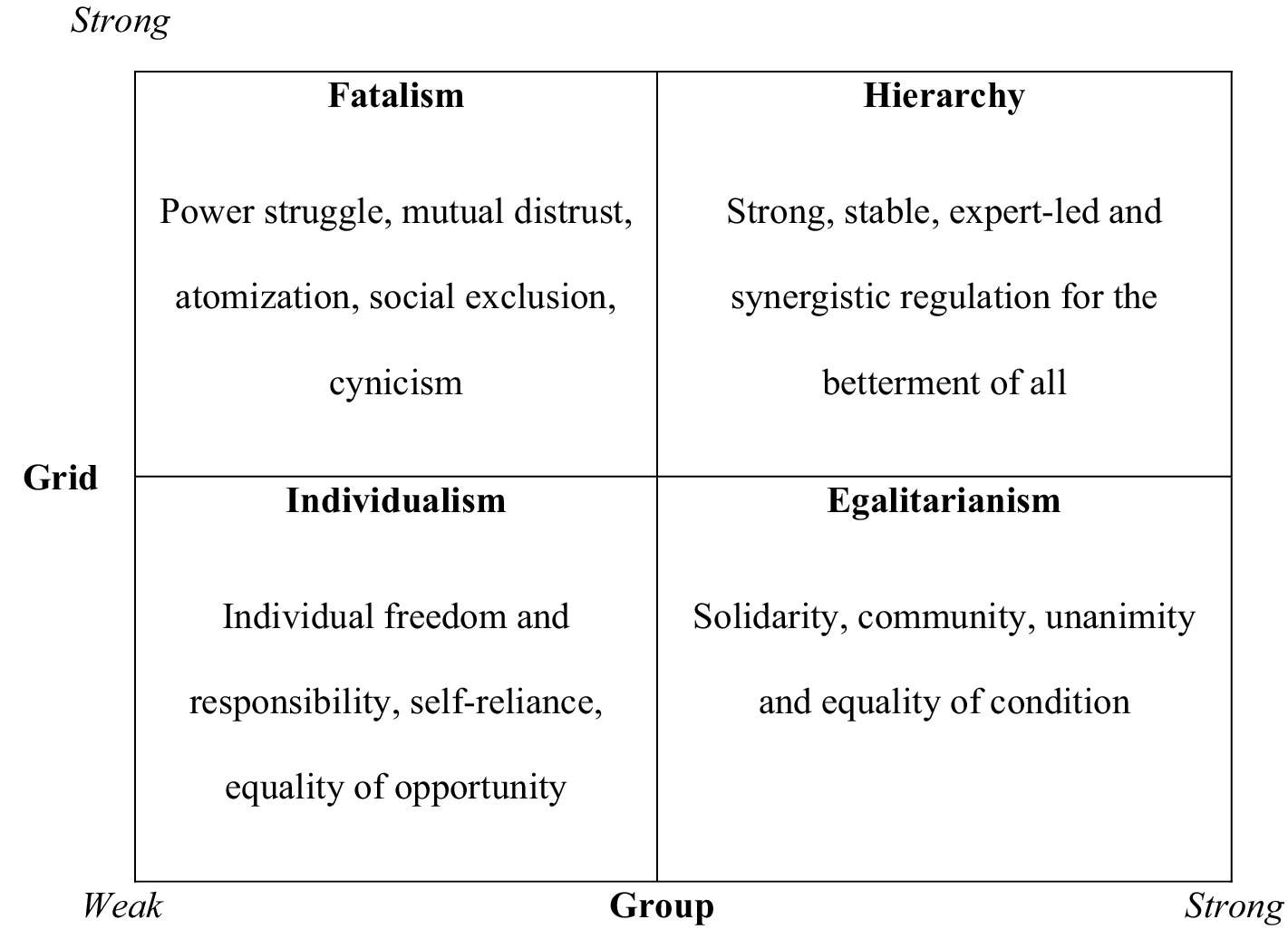

From Durkheim’s (2002) Suicide, Douglas extracted the dimensions that form her typology of elementary ways of organizing, perceiving and justifying social life. She relabeled Durkheim’s notion of regulation as “grid” and defined it as any limitations (such as imposed roles, rules, or taboos) on voluntary transactions among people. She renamed Durkheim’s concept of social integration as “group” and defined it as the extent to which people feel beholden to a larger social unit than the individual. But in contrast to Durkheim (who had produced a fourfold typology by focusing on the extremes of his two variables), Douglas derived her classification by assigning high and low values to both the group and grid dimension, before combining the two dimensions. This resulted in a fourfold typology of ways of organizing, perceiving and justifying social relations: hierarchy (high grid and high group), egalitarianism (high group and low grid), individualism (low group and low grid), and fatalism (low group and high grid) (see Figure 1).

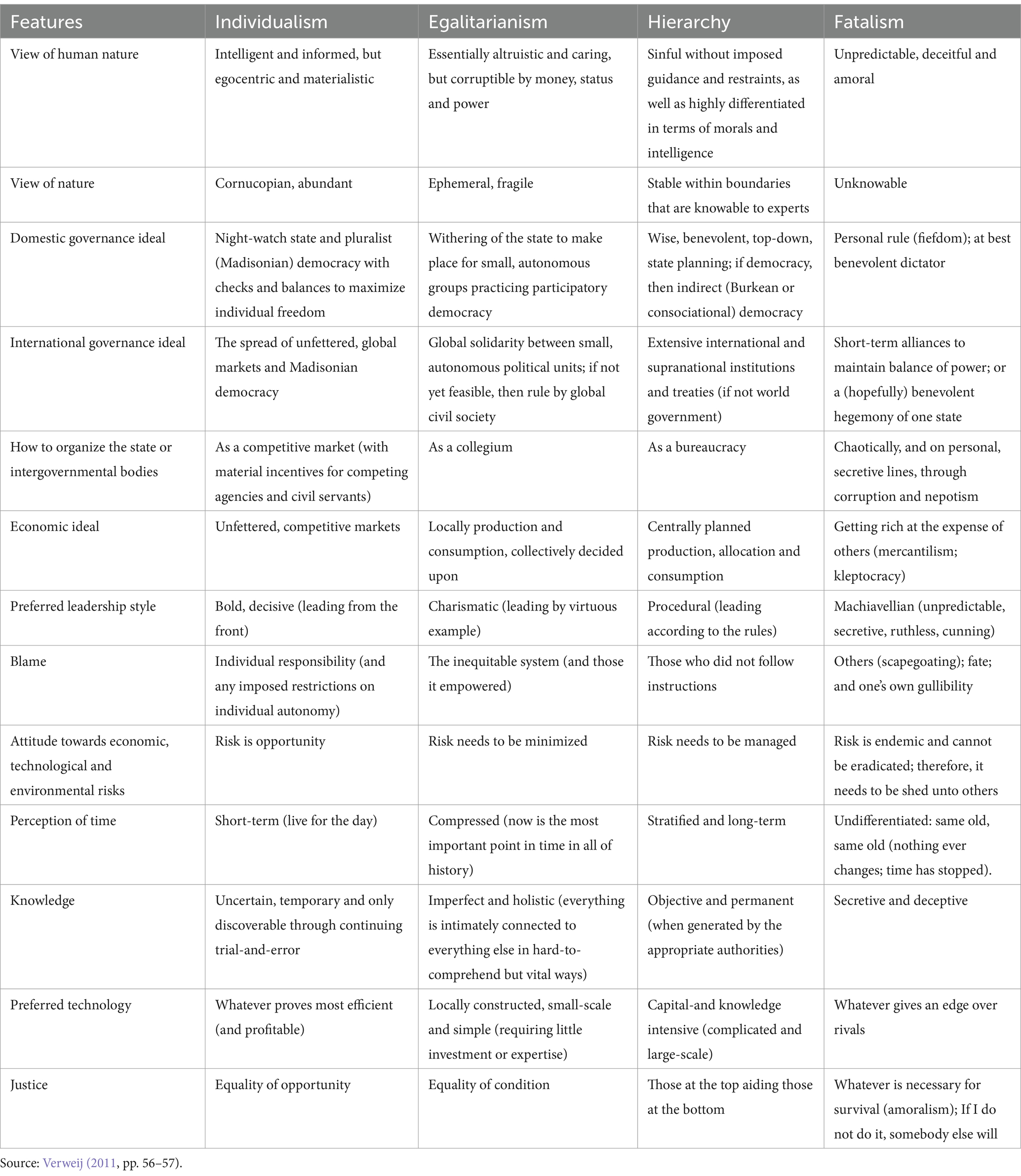

Together with fellow anthropologists Rayner and Thompson, as well as Wildavsky and other political scientists, Douglas then transformed her static grid-group typology into a dynamic approach, which has come to be known as the theory of sociocultural viability or, simply, cultural theory (Perri 6 and Swedlow, 2016; Perri 6 and Richards, 2017; Gross and Rayner, 1985; Hendriks, 2023; Hood, 1998; Thompson, 2008; Thompson et al., 1990). One step along this road was to flesh out the cultural bias of each way of life. In Table 1, thirteen features of cultural bias are highlighted.

Table 1. Thirteen features of Douglas’s four ways of organizing, perceiving and justifying social relations.

In a next step, it was recognized that within each social domain (from a restaurant to an international regime) all four ways of life occur, as each is dependent on all others. Since each way of life is formulated in contradistinction to all others, this also means that social strife is rife, according to Douglas’s cultural theory. Furthermore, this feature ensures individual agency. Individuals compare the claims about nature, human nature, etc. that are part of their preferred way of life with their perceptions of the outside world. They abandon their beliefs, and plumb for another way of life, once they realize that these observations are repeatedly at odds with their beliefs. This also ensures that cultural theory expects social reality to be in flux, with the number of adherents to ways of life waxing and waning. Finally, implications for governance were spelled out. It was predicted that, as ways of life are interdependent, collective efforts to address complex social and environmental issues that do not make creative and flexible use of all ways of life tend not to reach their goals (Garcés-Velástegui, 2022; Lodge, 2009; Verweij and Thompson, 2006). To prevent this from happening, governance efforts need to be “clumsy” or “polyrational”, i.e., inventive, adjustable combinations of all ways of life.

To date, Douglas’s cultural theory has been validated in a plethora of quantitative and qualitative tests (e.g., Johnson and Swedlow, 2021; Dimitrijevska-Markoski and Nukpezah, 2023). Yet one recurring criticism states that cultural theory’s conceptualization of fatalism needs to be expanded or at least relabeled (Coyle, 1994; Mars, 2008; Hollway and Pardo Enrico, 2012; van Eeten and Bouder, 2012). In cultural theory, fatalism is characterized by the imposition of many restrictions on voluntary transactions (high grid) that advance the interests of some individuals rather than those of everyone involved (low group). In such a social setting, people distrust and deceive one another, have little faith in institutions, feel isolated, strive—if necessary by hook or crook—to achieve relative gains for themselves, are unable to engage in collective action, tend to view society as rigged against them, experience life as erratic, and yet have little hope that anything resembling the “good life” can be achieved (e.g., Douglas, 2004; Ellis, 1994; Mars et al., 2023; Thompson et al., 1990, pp. 223–31). None of this has been disputed. What has been criticized are several conclusions frequently drawn from this conceptualization, namely that those who live in fatalistic conditions: (1) tend to find themselves at the bottom of society; (2) are passive and acquiescent; and (3) do not play a prominent role in politics and policymaking. If these conclusions were valid, then fatalism would be unlike cultural theory’s other ways of life, which are supposedly found at any rung of society and are involved in politics and governance. It would also mean that fatalism would not constitute an independent ideal-type and instead would be a by-product of other ways of life.

It has been argued that these are invalid inferences. A way of life in which people attempt to deceive one another and benefit at each other’s expense—by trying to “get their retaliation in early” (Thompson et al., 1999, p. 11)—is an active one, full of scheming. Furthermore, participating in politics and policymaking provides frequent opportunities for self-enrichment, relative gains, and lording it over others. Hence, the criticism is not that the bulk of the concept of fatalism has been misconstrued in cultural theory, but rather that its presence in political life and on all rungs of society has been underestimated (for exceptions, see Stoker, 2002; Ellison, 2007).

Paradoxically, despite frequent assertions that fatalism is a politically “passive” way of life (e.g., Douglas, 2007, p. 9), the strong, reciprocal ties between fatalistic social conditions and authoritarian political rule have long been recognized in cultural theory: “Fatalism generates (and is generated by) authoritarian political systems” (Thompson et al., 1990, p. 256). This paradox is resolved with the argument that: “A population that is withdrawn from the political sphere increases the scope for the exercise of arbitrary governmental power, thus further fuelling the citizenry’s withdrawal from politics” (ibid.). Douglas (1993, p. 511) concurs: “persons in this condition may become victims of tyranny just because forming associations is difficult for them by definition.” Hence, one argument is that those living in fatalistic circumstances do not have sufficient trust in each other to sustain the institutions necessary for democracies to function. Additionally: “Unable to predict when power will be abused and when it will not, the fatalist is predisposed to support authoritarian systems, which give them predictability without responsibility” (Thompson et al., 1990, p. 227).

However, in his application of cultural theory to leadership, Wildavsky (1989) goes beyond the argument that fatalism and authoritarianism are mutually supportive. He does so by equating fatalism with authoritarianism (p. 268) and fatalistic leadership with despotic rule (p. 269). In political science, authoritarianism is usually characterized by centralized power, limited political pluralism, restricted civil liberties, and minimal accountability of leaders (Linz, 2000). This makes authoritarianism high grid in terms of cultural theory, as the approach defines this dimension as the set of rules or roles that are decided upon by some and then imposed on others. In addition, the “canonical view” in political science (Przeworski, 2023, p. 979) is that authoritarian regimes are sustained through violence, repression, corruption, selective rewards to supporters, and manipulation of information (Guriev and Treisman, 2019; Svolik, 2012). These self-serving practices makes authoritarianism low group in cultural theory’s book(s). The combination of high grid and low group typifies fatalism. Hence, Wildavsky’s (1989) equation of fatalism with authoritarianism appears defensible. Moreover, it is in line with calls by other cultural theorists to relabel fatalism as “despotism” (Coyle, 1994) or “tyranny” (Mars, 2008).

In any case, there are sufficient grounds to reject the idea that cultural theory’s notion of fatalism is not a politically active way of life and can only be found in the margins of society, and not at the center. Recognizing this would also bring the theory’s high grid/low group way of life more fully in line with two studies that according to several cultural theorists (e.g., Thompson et al., 1990, pp. 223–227; Thompson, 2008, p. 130) empirically capture this set of circumstances: Banfield (1958) and Putnam (1993). According to the former (p. 118), “amoral familism is the ethos of the whole society—of the upper class as well as of the lower.” According to the latter (p. 101), “Politics in less civic regions is marked by vertical relations of authority and dependency, as embodied in patron-client relationships.” In the analysis below, I presume that the concept of fatalism can be applied to all social strata, including political leaders.

A cultural theory of populist leadership

Thus tweaked, cultural theory provides a theoretical framework that can potentially meet the three conceptual challenges set out above. In particular, its polythetic concept of fatalism can reveal the dimensions that underlie, and link, the institutional features of populist leadership, add several features to this list, and connect all these features to the factors that explain the global support for populism.

As can be seen in Table 1 (which was originally published in 2011, i.e., before the recent resurgence of populism), all the institutional traits of populist leadership that have been uncovered in empirical research are components of cultural theory’s fatalistic way of organizing, perceiving and justifying social relations. The first of these is corruption, which often (but not always) comes in the form of patronage and nepotism. As Table 1 indicates, corruption, patronage and nepotism are part and parcel of the fatalistic way of how to run the state. The second feature of populist rule is formed by protectionist (or mercantilist) economic policies, which in cultural theory is the fatalistic ideal for structuring a country’s economic relations with those of other countries. The next feature of populist command is the spread of conspiracy theories. This feature is less immediately recognizable in Table 1, as it only mentions that the fatalistic manner of handling knowledge is secretive and deceptive. However, Douglas has long recognized that the spread of conspiracy theories is rampant in fatalistic conditions (Douglas, 1992, p. 110; Douglas, 1996, pp. 186–187; Douglas, 2007). The fourth feature of populist rule concerns dishonesty, which is at the core of the fatalistic approach to producing and disseminating knowledge. A further characteristic of populist sway is personalistic rule, which is listed in Table 1 as the fatalistic preference for governing. Next in line is scapegoating, which is fatalism’s preferred way of attributing blame. The last of the institutional features of populist leadership is a realist foreign policy, which—as Table 1 shows—corresponds to the fatalistic approach to international politics.

Hence, all institutional characteristics of populist rule highlighted in the literature are also elements of cultural theory’s concept of fatalism. Even one of the personality traits of populist leaders that have been highlighted—Machiavellianism—appears in Table 1 (as fatalism’s preferred leadership style), although cultural theory is not a theory of individual personality differences. From this follows that Douglas’s cultural theory can be used to identify the common denominators of all the institutional traits of populist rule. These are the two dimensions that make up the theory’s category of fatalism: high grid [defined as the imposition of many restrictions on voluntary transactions, or what Gelfand and Lorente (2021) call “tightness”] combined with low group (i.e., little solidarity and other-regarding behavior). Hence, Douglas’s cultural theory suggests that recent research on populist leadership has not produced a random collection of unconnected traits, but has uncovered a set of closely linked features that are all aspects of a single way of organizing, perceiving and justifying social relations.

Moreover, the theory of sociocultural viability can be used to propose further elements of populist rule in addition to the ones that have already been confirmed in empirical research. This is the case as the features identified in the literature only correspond to 7 of the 13 fatalistic entries in Table 1. Left out are the fatalistic view of human nature, view of nature, risk attitude, perception of time, preferred type of technology, and sense of justice. It can be surmised that these predispositions must also characterize populist leadership. Plus, it would not be necessary to stop there. Table 1 was distilled from two considerably longer and older overviews of cultural theory’s ways of life (Verweij, 2011, p. 57). One of these overviews (Schwarz and Thompson, 1991, pp. 66–67) distinguishes between 22 features of each way of life (including fatalism), while the other one (Hofstetter, 1998, pp. 55–56) includes no less than 60 such features. Hence, Douglas’s cultural theory may be of help in detecting more general elements of populist rule.

Finally, cultural theory appears capable of linking the supply side of populism (that is, populist leadership) to the demand side (i.e., the support for populism). Many scholars have claimed that a full explanation of populism’s resurgence needs to account for how both sides are connected, but few have proposed how this can be done (for an exception using economic theory, see Benczes and Szabó, 2023). Cultural theory’s concept of fatalism may be helpful in overcoming this conceptual challenge as well. The “social approach” (Gidron and Hall, 2017) has shown that a string of related and similar social conditions ultimately underlies people’s enthusiasm for populism. These conditions comprise social malaise (Giebler et al., 2021), alienation (Cox, 2020), low social capital (Giuliano and Wacziarg, 2020; Boeri et al., 2021), lack of social integration (Gidron and Hall, 2017; Sachweh, 2020), perception that society is breaking down (Sprong et al., 2019) and loneliness (Hertz, 2020). These conditions match how living under fatalistic circumstances has been depicted in sociocultural viability theory. In setting out the theory’s core concepts, Rayner (1992, p. 89) explains “Finally, sector B (high grid/low group) is the category of stratified, often alienated, individuals.” Dake (1992, p. 30) concurs: “fatalists are hypothesized to construct a cultural bias that rationalizes isolation and resignation.” Ellis (1994, p. 123) equates fatalism to “individual atomization,” Thompson et al. (1999, p. 5) liken fatalism to “‘alienation’, ‘marginalisation’, ‘dependencia’ and ‘social exclusion’.” Douglas (1996, p. 84) agrees: “[the fatalist] is alienated.” To stress the loneliness of this way of life, Douglas (2007) usually prefers the term “isolation” over “fatalism”. Moreover, in Dake’s (1992) cultural theory questionnaire (p. 31), one of the five items for eliciting fatalistic attitudes reads: “I have often been treated unfairly.” Finally, as noted above, fatalism is associated with Putnam’s (1993) depiction of “low social capital”. This conceptual overlap suggests that cultural theory can be used to connect the supply side of populism to the demand side—through its concept of fatalism. Thus, the approach is also a promising candidate for meeting the last of the three challenges listed above.

The case of Donald J. Trump’s first presidency (2016–2020)

The proof of this conceptual pudding is in its empirical application. Below, I illustrate the argument that fatalism captures the views and strategies of populist leaders with an analysis of the first U.S. presidency of Donald J. Trump (2016–2020). I do so with the help of the 13 features of fatalism in Table 1, first published at a time when Trump becoming U.S. President still seemed comical (Roberts, 2016). I focus on Trump for one methodological and two practical reasons. First, the Trump presidency appears to represent an “extreme” case of populist leadership (Seawright and Gerring, 2008, pp. 301–302). In a study comparing Trump’s campaign style and personality with those of 21 other populist and 82 mainstream leaders, Nai et al. (2019, p. 609) conclude that Trump is “an outlier among the outliers” when it comes to being abrasive, narcissistic and confrontational. This conclusion holds even when the comparison is restricted to fellow populist politicians. Müller (2021) concurs: “while Trump has been omnipresent, he has never been a typical populist. Right-wing populists in government tend to be more careful when it comes to maintaining a façade of legality and avoiding direct association with street violence.” In particular, focusing on Trump’s presidency amounts to selecting an extreme value on the independent variable. This becomes clear if I reformulate the argument made above in the form of a hypothesis: if a political leader is populist (according to Müller’s definition), then their views and actions will be fatalistic (as per Douglas’s cultural theory). Seawright (2016, p. 502) has shown that “extreme cases on the independent variable offer the best chance of making discoveries across a wide range of case study goals.”

Second, at the time, Trump was leader of the country with the largest economy and strongest military—an office he recently reoccupied. Hence, a focus on his presidency also has practical relevance. Third, Trump’s first presidency has been described in minute detail by many observers, probably to a greater degree than the administration of any other populist. As a result, reams of secondary data are available for analysis. I have opted to mainly work with secondary data provided by journalists who had direct access to the Trump White House and who work for outlets known for rigorous fact-checking. (The other sources of data are academic analyses). The illustration below is based on an informal, but comprehensive, congruence analysis of these secondary data, albeit one that employs a single theoretical framework (Blatter, 2012, pp. 11–12).

In Table 1, fatalism’s first feature is its view of human nature, which states that people are unpredictable, deceitful and amoral. This describes President Trump’s view of other people (Haberman, 2022, p. 233). In his words (Kruse, 2017), “I do not trust people, no. I am a non-trusting person.” His niece, a clinical psychologist, explains what this means: “often the person he’s getting revenge on is somebody he screwed over first” (Trump, 2020, p. 208). Hence the trademark of Trump’s presidency was “not mercy but holding grudges and settling scores” (Hennessey and Wittes, 2020, p. 259). As White House official Joseph Grogan put it: “He is a zero-sum game motherfucker from New York” (Leonnig and Rucker, 2021, p. 99).

Fatalism’s second feature concerns its view of nature as essentially unknowable. Hence, there is no sense in worrying about environmental or health issues or trying to plan for these. This perspective characterized Trump’s approach to the two biggest environmental and health issues of his presidency: human-made climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic. Trump’s take on these issues oscillated wildly. Concerning climate change, Trump opined that “nobody really knows” whether climate change is happening (Eilperin, 2016). He himself appeared to be of two minds: he called climate change “mythical,” “non-existent” and “an expensive hoax,” but also a “serious subject” that is “very important to me” and described himself as an “environmentalist” who cares deeply about clean air and water (Cheung, 2020). Given these incompatible views, environmental lawyers Goffman and Gerrard concluded that Trump “believes nothing on climate change” and “does not really understand what climate change is about” (Cheung, 2020). This contradictory, ill-informed understanding of climate change epitomizes the fatalistic view of nature in Douglasian cultural theory.

Trump’s understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have been equally uninformed and contradictory, veering from “We have [the pandemic] under control” to “worse before it gets better” in the span of a few hours (Woodward, 2020, p. 385). For instance, on two occasions in November 2020, after more 200,000 U.S. lives had been lost to the pandemic, Trump seemed genuinely surprised to hear from his Health Secretary that mask wearing and social distancing reduced the chance of infection (Leonnig and Rucker, 2021, pp. 376, 396). Earlier that year, President Trump had not only suggested, against medical advice, to inject bleach into the human body to fight COVID-19 (McGraw and Stein, 2021). He had also, in the middle of a 30-day extension of his administration’s “15 Days to Slow the Spread,” tweeted “Liberate Minnesota,” “Liberate Michigan” and “Liberate Virginia,” thus subverting his own guidelines (Woodward, 2020, p. 353). In general, President Trump never developed a coherent, evidence-based COVID-19 strategy, and marginalized governmental scientists and health officials who tried to do so (Leonnig and Rucker, 2021, pp. 98–99; Woodward, 2020, p. 309). This approach is in line with the fatalistic conviction that nature is unknowable, and that it is therefore futile to develop coherent environmental and health policies. Trump’s approach resulted in the United States experiencing the highest rate of excess deaths per capita of all high-income countries during the pandemic (Islam et al., 2021). The president’s commented on this loss of life with a quintessential fatalistic phrase: “It is what it is” (Holpuch, 2020).

The fatalistic domestic governance ideal is to establish a personal fiefdom. This was Trump’s aim as well. According to Hennessey and Wittes (2020, p. 13), in Trump’s presidency “the institutional office and the personality of its occupant are almost entirely merged—merged in their interests, in their impulses, in their finances, and in their public character.” Leonnig and Rucker (2021, p. 4) concur: “whether managing the coronavirus or addressing racial unrest or reacting to his election defeat, Trump prioritized what he thought to be his political and personal interests over the common good.” One way in which he managed to do so was by constantly pitting governmental officials against each other (Leonnig and Rucker, 2021, p. 316; Haberman, 2022, p. 3). Another way involved demanding that governmental officials were loyal to him rather than follow the U.S. Constitution. Trump “imagined being president as something like being king” (Hennessey and Wittes, 2020, p. 259).

The fatalistic preference for international governance is to build short-term alliances to achieve a balance of power—in other words, to pursue a realist foreign policy. This is what the Trump presidency attempted to achieve (Ashford, 2025; Byers and Schweller, 2024; Brooks, 2016; O’Brien, 2024). It set out its foreign policy ambitions in its first National Security Strategy. In this document (The White House, 2017, p. ii), the President declared that:

We will promote a balance of power that favors the United States, our allies, and our partners…Most of all, we will serve the American people and uphold their right to a government that prioritizes their security, their prosperity, and their interests. This National Security Strategy puts America First.

The text (The White House, 2017, p. 55) also clarified that:

This strategy is guided by principled realism. It is realist because it acknowledges the central role of power in international politics, affirms that sovereign states are the best hope for a peaceful world, and clearly defines our national interests.

The fatalistic manner of organizing the state is chaotically, secretively, corruptly and nepotistically. All four features typified the Trump White House. The president’s management style was chaotic and devoid of planning (Haberman, 2022 p. 11). It has been labelled “a carnival ride” (Leonnig and Rucker, 2021, p. 1), the “Wild West” (Alberta, 2019, p. 462), “dysfunction by design” (Moynihan and Roberts, 2021), and driven by “whim and will” (Hennessey and Wittes, 2020, p. 52). The turnover among senior level advisors to President Trump reached a remarkable 92% (Dunn Tenpas, 2021). One cause of the chaos was that the president encouraged governmental officials to fight each other (Woodward, 2018, pp. 236–237; Leonnig and Rucker, 2021, p. 7). Another cause was that Trump could not be bothered to engage in long-term planning or even staying on top of his briefs and often followed opinions vented on his favorite TV shows (Leonnig and Rucker, 2021, p. 19; Hennessey and Wittes, 2020, p. 103).

Trump attempted to shroud his presidency in secrecy (Restuccia, 2019)—another feature of fatalistic public administration. He was the first president since 1977 to not release his tax returns. Moreover, unlike the preceding Obama and succeeding Biden administrations, the Trump White House did not publish its visitor logs. Trump also frequently and illegally tore up official documents (Karni, 2018), and instructed his officials to not testify in Congressional hearings, not even when subpoenaed.

The Trump presidency also displayed corruption (Confessore et al., 2020). Trump broke with a 40-year tradition by refusing to put his personal wealth in a blind trust. Over the protests of the U.S. Office of Government Ethics, he temporarily handed control over his business empire to his two eldest sons, while maintaining ownership. This opened many ways in which Trump and family members were able to use the office of president to enrich themselves. Donors, lobbyists and foreign governments flocked to his resorts, hotels and golf clubs, and proposed business deals, to curry political favor by enriching the president and his family. Trump’s frequent stays at his own resorts forced the Secret Service to make use of his companies’ services at American taxpayers’ expense. Several cabinet members followed their boss’s lead in financially benefiting from their positions of power. The Trump administration and campaign also engaged in non-pecuniary forms of corruption. In 2019, by withholding hundreds of millions of US$ of military aid, Trump attempted to force Ukrainian President Zelensky into opening a criminal investigation into former US President Biden (his expected opponent in the 2020 presidential elections) and one of Biden’s children. He and his associates also tried to coerce the Zelensky government into fabricating evidence that Ukrainians, rather than the Russian state, had hacked the email server of the Democratic National Committee during the 2016 presidential campaign. The U.S. Governmental Accountability Office (2020) judged these acts to be illegal.

The Trump presidency was nepotistic as well. He appointed his oldest daughter and her husband to influential positions in his administration without either of them having relevant qualifications or experience (Woodward, 2018, pp. 144–145; Hennessey and Wittes, 2020, p. 138). President Trump also made a former manager of one of his golf clubs the White House director of social media (Woodward and Costa, 2021, p. 231).

In sociocultural viability theory, the fatalistic economic ideal is to get rich at the expense of others. President Trump strove to achieve this at two levels. At the state level, he attempted to impose a mercantilist economic policy (Nelson, 2019), viewing a trade surplus for the United States as the “holy grail” of trade policy (Woodward, 2018, p. 208). He was deeply suspicious of free trade (Hennessey and Wittes, 2020, p. 247) and often mused about withdrawing military support from countries with which the United States had a trade deficit. At the personal level, as argued above, Trump did not hesitate to use the presidency to enrich himself.

The leadership style displayed in fatalistic circumstances is Machiavellian, i.e., secretive, unpredictable and ruthless. The level of secrecy and unpredictability of the Trump presidency has been indicated above. His unpredictability is intentional: “I want to be unpredictable. I do not want to tell you exactly what I’m going to do … I do not want the enemies and even our allies to know exactly what I’m thinking” (quoted in Saletan, 2016). Ditto his ruthlessness: “Real power is fear. It’s all about strength. Never show weakness. You’ve always got to be strong. Do not be bullied. There is no choice” (Woodward, 2018, p. xiii).

The fatalistic reaction to things going wrong is to scapegoat others rather than take personal responsibility. Throughout his presidency, Trump pursued a “strategy of self-victimization” (Leonnig and Rucker, 2021, p. 4) whenever things went awry. According to this niece, this is because “Taking responsibility would open him up to blame” (Trump, 2020, p. 210). During the largest crisis of his presidency—the global coronavirus pandemic that broke out in late 2019—Trump alternately blamed migrants, Democratic governors, the Director of the U.S. Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the World Health Organisation and the Chinese state for the fact that the United States had experienced the highest level of excess deaths per capita of all high-income countries (Woodward, 2020, pp. 312, 379 and 383). Asked if his actions had anything to do with it, he replied: “No, I do not take responsibility at all” (Leonnig and Rucker, 2021, p. 84). Forty percent of Trump’s Tweets dedicated to the pandemic blamed others, and not one expressed empathy (Ott and Dickinson, 2020, p. 608). Moreover, throughout his presidency, Trump sought to scapegoat migrants for an assortment of social and economic ills besetting the United States (Löfflmann, 2022).

The fatalistic risk attitude is that risk cannot be eradicated or managed; instead, it needs to be deflected onto others. In Trump’s view, risk lurked everywhere: “when you are running a country, it’s full of surprises. There is dynamite behind every door” (Woodward, 2018, p. xx). He often took risks such that advantages would accrue to him while disadvantages would be borne by others (Haberman, 2022, p. 10). Trump did so by employing a Mafia tactic: he would frequently mention to his staff and supporters that reaching certain goals with norm-and/or law-breaking means (such as withholding Congress-approved military aid from Ukraine or challenging the results of the 2020 presidential election) would be advantageous to him without explicitly ordering these courses of action (Farrell, 2021). If these courses of action were successfully undertaken by his staff or supporters, Trump would reap the benefits. If not, he had deniability.

In cultural theory, the fatalistic perception of time is undifferentiated: its passing is experienced as a random sequence of “one damn thing after another” (McAdams, 2021). Trump’s presidency was characterized by a seemingly unending stream of political scandals (including two impeachments and a sacking of Congress), underscored by daily Tweets “in which he lashed out in highly personal terms and often with malicious lies at political foes and at anyone who angered him” (Hennessey and Wittes, 2020, p. 10). As a result, or so many people have said, the Trump presidency appeared to last an eternity (Burdick, 2018).

The fatalistic approach to knowledge is to use it secretively and deceptively. The Trump presidency was, if anything, deceptive. As Hennessey and Wittes (2020, p. 109) put it: “This is Trump’s radical proposed revision to the traditional presidency: that he can be known to everyone as a ‘fucking liar’—not an occasional liar, not a calculating liar, but a pervasive, constant liar and bullshitter on all subjects at all times”. According to the Washington Post Fact Checker (Kessler et al., 2021), Trump made 30,573 false or misleading claims during his four-year presidency and wielded 5 million words to do so. His staff contributed to the deception by frequently furnishing empirically invalid “alternative facts” (Alberta, 2019, p. 429).

Another fatalistic preference listed in Table 1 is for technology that represents dominance and exclusion. President Trump expressed such a preference in a January 2018 Tweet (Woodward, 2018, p. 300):

North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un just stated that the Nuclear Button is on his desk at all times. Will someone from his depleted and food starved regime please inform him that I too have a Nuclear Button, but is much bigger and more powerful than his, and my Button works!

On other occasions, Trump boasted about the United States having airplanes that “you literally cannot see” as well as “super-duper missiles” (Associated Press, 2020). The same aptitude for intimidating technology was evident in Trump’s major infrastructure initiative: the building of a wall covering 1,000 miles of the Mexican-U.S. border to reduce illegal migration. Unlike his predecessors, Trump maintained a strong focus on the wall’s characteristics, employing phrases such as “impenetrable,” “magnificent” and “great” that conjure up images of determination, strength and resolve (Kolås and Oztig, 2022, pp. 8–9). The solicitation document of the U.S. Customs and Border Control specified that the wall must be “physically imposing” (Kolås and Oztig, 2022, p. 9). Trump also ordered the wall to be painted black (at an estimated additional cost of US$ 500 million to 3 billion), insisting that the dark color would enhance its forbidding appearance and leave the steel too hot to touch during summer months (Dawsey and Miroff, 2020).

The final feature of fatalism in Table 1 is its amoral, nihilistic view of justice, according to which anything is allowed that ensures survival in a dog-eats-dog world. This view of justice is premised on the idea that the world is full of danger and unfairness and that therefore one has to strive for relative gain. Or as Trump tweeted in 2012: “When someone attacks me, I always attack back … except 100x more. This has nothing to do with a tirade but rather, a way of life!” This view remained operative during his presidency, when Trump continued to believe that “kindness is weakness, manners are for wimps and the public interest is for suckers” (Hennessey and Wittes, 2020, p. 7). A content analysis of 3,876 of President Trump’s Tweets found that 44% contained personal insults and attacks on the media (Monahan and Maratea, 2021, p. 706).

Hence, all 13 features of fatalism listed in Table 1 typify the Trump presidency. This provides further ammunition for the argument that the fatalistic way of life (as specified in cultural theory) is an empirically viable concept that can be observed at all levels of society and recognized as an active force in politics.

Conclusion

In this article, I have examined the extent to which the theory of sociocultural viability can help meet three challenges in the study of (authoritarian) populist leadership. They are: (1) to find the underlying social dimensions connecting the features of populist leadership that have been uncovered in the literature; (2) to propose additional features of populist leadership; and (3) to link the supply of populist policies with the demand for such policies. The guiding hypothesis was that the theory’s concept of fatalism could meet these challenges (as long as it is recognized that this way of organizing, perceiving and justifying social relations can also be found at the center of political decision-making and not just in the margins of society). I have argued that cultural theory’s concept of fatalism includes all the institutional features of populist leadership that have been identified thus far, suggests additional features of such leadership (such as perceptions of nature, human nature and time), and appears to encompass some of the main causes of the increased support for populism, thus opening a pathway to linking the supply of, and demand for, populism. Finally, I have shown that Donald J. Trump’s first presidency has all the hallmarks of fatalism, as conceived in Douglas’s cultural theory.

These arguments open an expansive research agenda. To complete and test the arguments, it would be important to undertake case studies comparing the discourses of both populist and non-populist leaders around the world. For instance, it can be analyzed whether the actions, perceptions and opinions of contemporary populists such as Rodrigo Duterte, Recep Erdoğan, Javier Milei, Marine le Pen, Narendra Modri and Victor Orbán are fatalistic (as defined in Douglas’s cultural theory). It can also be checked if it is the case that the Brothers of Italy party led by Giorgia Meloni is fatalistic, while the country’s Five Star Movement is not (given that the former is populist, but the latter is not or not fully, according to Müller’s definition). In the same manner, the actions and views of Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn can be contrasted to his (much more populist) compatriot Geert Wilders. Such analyses do not need to be limited to the present but could for example also be undertaken of US Senator Huey Long (who died in 1935) or nineteenth-century US Presidents Millard Fillmore and Andrew Johnson. Only by analyzing a wide range of populist politicians and movements, and comparing these to non-populist leaders and parties, can the central hypothesis I have set out here be fully tested.

It would be helpful to undertake these case studies in a more rigorous fashion than my congruence analysis of Trump’s first presidency. The studies would benefit from using formal content analysis and from checking for inter-rater reliability (Schreier, 2012). Moreover, to explore further aspects of populist rule, the analyses could involve more than the 13 features of fatalism listed in Table 1. Do, for instance, populist leaders espouse a fatalistic aesthetic as well? In addition, it would be interesting to further probe and extend the connections between the supply and demand sides of populism noted above. Are other factors that have been shown to boost the demand for populism elements of cultural theory’s concept of fatalism as well? If so, then the theory may offer more than an analysis that is applicable to both ends of the populist marketplace. Rather than separating a social phenomenon into two halves by applying a market metaphor to it, and then trying to connect these halves again, analyzing populism as a manifestation of fatalism may allow us to view it as a single mode of organizing, perceiving, justifying and emotionally experiencing social relations that spans across levels of analysis.

Finally, it would be helpful to reflect on and analyze the possible practical implications of this research agenda. If it were the case that populist parties and movements are fatalistic, then this would imply that chaotic, contradictory governance is a feature, and not a bug, of populist rule. Moreover, it would suggest that—contrary to the frequently made argument (e.g., Shayegh et al., 2022) that members of populist movements generate solidarity with one another through the creation of a rigid ingroup/outgroup boundary—populists display little inter-personal trust and mutual support. This would then also raise the question what this would signify for the strength and duration of populist movements and for how social and political opposition could undermine these movements. Given that for now populism remains on the rise around the world, implementing this research agenda would be a worthwhile endeavor.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation through their NWO-von Humboldt Award (grant no. 04010.10.011/4703).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Author’s translation of: “Das entscheidende Kriterium ist vielmehr, dass sich im Diskurs der Populisten ein dezidierter Antipluralismus findet und dass sie sich stets auf das Volk als eine eindeutig moralische Größe beziehen.”

2. ^In the original: “registre discursif à vocation hégémonique qui repose sur l’exaltation de l’identification populaire opérée à travers l’articulation idéologique des caractéristiques supposées d’une collectivité (le « Peuple ») et l’exclusion des altérités coupables pour la non-plénitude de l’identité de cette collectivité.”

References

Ashford, E. (2025). Four explanatory models for Trump’s chaos. Foreign Policy, 24 April. Available online at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/04/24/trump-100-days-chaos-explanatory-models-foreign-policy/ (accessed June 10, 2025).

Associated Press (2020). Trump’s talk of secret new weapon fits a pattern of puzzles https://www.politico.com/news/2020/09/11/trump-secret-new-weapon-412539

Bass, B. M., and Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership and organizational culture. Public Adm. Q. 17, 112–121.

Benasaglio Berlucchi, A., and Kellam, M. (2023). Who’s to blame for democratic backsliding: populists, presidents or dominant executives? Democratization 30, 815–835. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2023.2190582

Benczes, I., and Szabó, K. (2023). An economic understanding of populism: a conceptual framework of the demand and the supply side of populism. Polit. Stud. Rev. 21, 680–696. doi: 10.1177/14789299221109449

Blatter, J. (2012). Innovations in case study methodology: Congruence analysis and the relevance of crucial cases. Annual Meeting of the Swiss Political Science Association: 2–3 February; Lucerne. Available online at: www.unilu.ch/fileadmin/fakultaeten/ksf/institute/polsem/Dok/Projekte_Blatter/Case_Study_Methods_and_Qualitative_Comparative_Analysis__QCA_/blatter-congruence-analysis-and-crucial-cases-svpw-conference-2012.pdf (Accessed March 3, 2025).

Boeri, T., Mishra, P., Papageorgiou, C., and Spilimbergo, A. (2021). Populism and civil society. Economica 88, 863–895. doi: 10.1111/ecca.12374

Brooks, R. (2016). Donald Trump has a coherent, realist foreign policy. Foreign Policy. Available online at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/04/12/donald-trump-has-a-coherent-realist-foreign-policy/ (accessed June 10, 2025)

Burdick, A. (2018). Is Trump warping our sense of time? N. Y. Times, 20 January. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/20/opinion/sunday/trump-sense-of-time.html (accessed June 10, 2025).

Byers, A., and Schweller, R. L. (2024). Trump the realist. Foreign Affairs. Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/donald-trump-realist-former-president-american-power-byers-schweller. (Accessed June 10, 2025).

Chryssogelos, A. (2023). Introduction: thinking about populism in international relations. Int. Stud. Rev. 25, 2–8. doi: 10.1093/isr/viad035

Çinar, I., Stokes, S., and Uribe, A. (2020). Presidential rhetoric and populism. President. Stud. Q. 50, 240–263. doi: 10.1111/psq.12656

Confessore, N., Yourish, K., Eder, S., Protess, B., HYPERLINK Haberman, M., Ashford, G., et al. (2020). The swamp that Trump built. N. Y. Times, 10 October. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/10/10/us/trump-properties-swamp.html (accessed June 10, 2025)

Cox, D. (2020). Could social alienation among some Trump supporters help explain why polls underestimated Trump again? Available online at: https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/could-social-alienation-among-some-trump-supporters-help-explain-why-polls-underestimated-trump-again/ (Accessed January 12, 2023).

Coyle, D. J. (1994). “The theory that would be king” in Politics, policy and culture. eds. D. J. Coyle and R. J. Ellis (Boulder, CO: Westview), 219–239.

Dake, K. (1992). Myths of nature: culture and the social construction of risk. J. Soc. Issues 48, 21–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1992.tb01943.x

Dawsey, J., and Miroff, N. (2020). Biden order to halt border wall project would save U.S. $2.6 billion, pentagon estimate shows. Washington Post, 16 December. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/immigration/stopping-border-wall-save-billions/2020/12/16/fa096958-3fd1-11eb-a402-fba110db3b42_story.html (accessed June 10, 2025).

de Kets Vries, M. F. R. (2020). How leaders get the worst out of people: the threat of hate-based populism. INSEAD Working Paper No. 2020/60/EFE, 3 December. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3741909

De Moraes, R. F. (2022). Demagoguery, populism, and foreign policy rhetoric: evidence from Jair Bolsonaro’s tweets. Contemp. Polit. 29, 249–275. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2022.2126155

Destradi, S., and Plagemann, J. (2019). Populism and international relations: (un)predictability, personalisation, and the reinforcement of existing trends in world politics. Rev. Int. Stud. 45, 711–730. doi: 10.1017/S0260210519000184

Destradi, S., and Vüllers, J. (2024). Populism and the liberal international order: an analysis of UN voting patterns. Rev. Int. Organ. doi: 10.1007/s11558-024-09569-w

Dimitrijevska-Markoski, T., and Nukpezah, J. A. (2023). COVID-19 risk perception and support for COVID-19 mitigation measures among local government officials in the US: a test of a cultural theory of risk. Adm. Soc. 55, 351–380. doi: 10.1177/00953997221147243

Douglas, M. (1993). Emotion and culture in theories of justice. Econ. Soc. 22, 501–515. doi: 10.1080/03085149300000031

Douglas, M. (2004). “Traditional culture: let’s hear no more about it” in Culture and public action. eds. V. Rao and M. Woolcock (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press), 85–109.

Douglas, M. (2007) Talking dirty. Am. Inter. 2. Available online at: https://www.the-american-interest.com/2007/03/01/talking-dirty/.

Dunn Tenpas, K. (2021). Tracking turnover in the Trump administration. Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/tracking-turnover-in-the-trump-administration/ (Accessed January 8, 2023).

Eilperin, J. (2016). Trump says ‘nobody really knows’ if climate change is real. Washington Post, 11 December. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/energy-environment/wp/2016/12/11/trump-says-nobody-really-knows-if-climate-change-is-real/ (accessed June 10, 2025)

Elçi, E. (2024). Authoritarian populism. N. Lindstaedt and J. J. J. Boschvan den Research handbook on authoritarianism Cheltenham Edward Elgar 42–58

Ellis, R. J. (1989). Dilemmas of presidential leadership: From Washington to Lincoln. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Ellis, R. J. (1994). “The social construction of slavery” in Politics, policy and culture. eds. D. J. Coyle and R. J. Elis (Boulder, CO: Westview), 117–135.

Ellison, D. (2007). Public administration reform in Eastern Europe. Adm. Soc. 39, 221–232. doi: 10.1177/0095399706298053

Farrell, H. (2021). Free speech or incitement? Here’s how Trump talks like a mob boss. Washington Post, 10 February.

Favero, A. (2023). Myth: All populist leaders are ‘charismatic’. In: The loop: ECPR’s political science blog. Available online at: https://theloop.ecpr.eu/myth-all-populist-leaders-are-charismatic/ (Accessed January 10, 2025).

Foa, R., and Mounk, Y. (2018). The end of the consolidation paradigm. J. Democr. doi: 10.17863/CAM.90407

Foa, R., Romero-Vidal, X., Klassen, A., Fuenzalida Concha, J., Quednau, M., and Fenner, L. (2022) The great reset: public opinion, populism, and the pandemic. Bennett Institute for Public Policy, University of Cambridge. Available online at: www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/342848 (Accessed June 10, 2025).

Foroughi, H., Gabriel, Y., and Fotaki, M. (2019). Leadership in a post-truth era: a new narrative disorder? Leadership 15, 135–151. doi: 10.1177/1742715019835369

Funke, M., Schularick, M., and Trebesch, C. (2023). Populist leaders and the economy. Am. Econ. Rev. 113, 3249–3288. doi: 10.1257/aer.20202045

Garcés-Velástegui, P. (2022). Governancing development in the Andes: from wicked problem to clumsy solutions via messy institutions. Lat. Am. Policy 13, 258–275. doi: 10.1111/lamp.12266

Gelfand, M. J., and Lorente, R. (2021). “Threat, tightness, and the evolutionary appeal of populist leaders” in The psychology of populism. eds. J. P. Forgas, W. D. Crano, and K. Fiedler (London: Routledge), 276–293.

Gidron, N., and Hall, P. (2017) Populism as a problem of social integration. San Francisco, CA: Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association. Available online at: https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/hall/files/gidronhallapsa2017.pdf (Accessed September 2, 2018).

Giebler, H., Hirsch, M., Schürmann, B., and Veit, S. (2021). Discontent with what? Linking self-centered and society-centered discontent to populist party support. Polit. Stud. 69, 900–920. doi: 10.1177/0032321720932115

Giuliano, P., and Wacziarg, R. (2020) Who voted for Trump? Populism and social capital. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series 27651

Giurlando, P. (2020). Populist foreign policy: the case of Italy. Can. Foreign Policy J. 27, 251–267. doi: 10.1080/11926422.2020.1819357

Grigoriadis, I. N., and Işık Canpolat, E. (2024). Elite universities as populist scapegoats: evidence from Hungary and Turkey. East. Eur. Polit. Soc. 38, 432–454. doi: 10.1177/08883254231203338

Grint, K. (2010). “Wicked problems and clumsy solutions: the role of leadership” in The new public leadership challenge. eds. S. Brookes and K. Grint (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 169–186.

Grint, K. (2024). Is leadership the solution to the wicked problem of climate change? Leadership 20, 77–95. doi: 10.1177/17427150231223595

Guriev, S., and Treisman, D. (2019). Informational autocrats. J. Econ. Perspect. 33, 100–127. doi: 10.1257/jep.33.4.100

Haberman, M. (2022). Confidence man: The making of Donald Trump and the breaking of America. London: Penguin.

Hameleers, M. (2021). They are selling themselves out to the enemy! The content and effects of populist conspiracy theories. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 33, 38–56. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edaa004

Hloušek, V., Meislová, M. B., and Havlík, V. (2024). Emotions of fear and anger as a discursive tool of radical right leaders in Central Eastern Europe. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1385338. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1385338

Hollway, J., and Pardo Enrico, C. (2012). Finding fatalism: taking cynics seriously. Paper presented at the Third Annual Douglas Seminar, London: University College London.

Holpuch, A. (2020). 'They're dying… it is what it is'. Guardian, 4 August. Available only at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/aug/04/donald-trump-interview-axios-covid-19-epstein-john-lewis (accessed June 10, 2025).

Hooghe, L., and Marks, G. (2019). Grand theories of European integration in the twenty-first century. J. Eur. Public Policy 26, 1113–1133. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2019.1569711

Hoppe, R. (2007). “Applied cultural theory: tool for policy analysis” in Handbook of public policy analysis, theory, politics and methods. eds. F. Fischer, G. J. Miller, and M. S. Sidney (New York: CRC Press), 289–308.

Inglehart, R., and Norris, P. (2017). Trump and the xenophobic populist parties: the silent revolution in reverse. Perspect. Polit. 15, 443–454. doi: 10.1017/S1537592717000111

Islam, N., Shkolnikov, V. M., Acosta, R. J., Klimkin, I., Kawachi, I., Irizarry, R. A., et al. (2021). Excess deaths associated with covid-19 pandemic in 2020: age and sex disaggregated time series analysis in 29 high income countries. BMJ 373:1137. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1137

Johnson, B., and Swedlow, B. (2021). Cultural theory's contributions to risk analysis. Risk Anal. 41, 429–455. doi: 10.1111/risa.13299

Karni, A. (2018). Meet the guys who tape Trump's papers back together. Politico.com, 10 June. Available online at: https://www.politico.com/story/2018/06/10/trump-papers-filing-system-635164.

Kessler, G., Rizzo, S., and Kelly, M. (2021) Trump’s false or misleading claims total 30, 573 over 4 years. Washington Post, 24 January.

Kluknavská, A., Eisele, O., Bartkowska, M., and Kriegler, N. (2024). A question of truth: accusations of untruthfulness by populist and non-populist politicians on Facebook during the COVID-19 crisis. Inf. Commun. Soc. 28, 258–277. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2024.2357708

Kolås, Å., and Oztig, L. (2022). From towers to walls: Trump’s border wall as entrepreneurial performance. Environ. Plan. C-Gov. Policy. 40, 124–142. doi: 10.1177/23996544211003097

Kruse, M. (2017). The loneliest president. Politico.com, 15 September. Available online at: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/09/15/donald-trump-isolated-alone-trumpology-white-house-215604/.

Lacatus, C., and Meibauer, G. (2022). ‘Saying it like it is’: right-wing populism, international politics, and the performance of authenticity. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 24, 437–457. doi: 10.1177/13691481221089137

Lammers, W., and Onderco, M. (2020). Populism and foreign policy: an assessment and a research agenda. J. Reg. Secur. 15, 199–233. doi: 10.5937/jrs15-24300

Lamont, M. (2016). Trump’s triumph and social science adrift: what is to be done?. American Sociological Association. Available online at: http://www.asanet.org/trumps-triumph-and-social-science-adrift-what-be-done (Accessed September 17, 2017).

Lodge, M. (2009). The public management of risk: the case for deliberating among worldviews. Rev. Policy Res. 26, 395–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-1338.2009.00391.x

Löfflmann, G. (2022). Enemies of the people’: Donald J. Trump and the security imagery of America first. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 24, 543–560. doi: 10.1177/13691481211048499

Magcamit, M. (2017). Explaining the three-way linkage between populism, securitization and realist foreign policies: president Donald Trump and the pursuit of “America first” doctrine. World Aff. 180, 6–35. doi: 10.1177/0043820017746263

Magcamit, M. (2020). The Duterte method: a neoclassical realist guide to understanding a small power’s foreign policy and strategic behaviour in the Asia-Pacific. Asian J. Comp. Polit. 5, 416–436. doi: 10.1177/2057891119882769

Mars, G. (2008). From the enclave to hierarchy – and on to tyranny: the micro-political organization of a consultant’s group. Cult. Organ. 14, 365–378. doi: 10.1080/14759550802489755

Mars, S. G., Koester, K. A., Ondocsin, J., Mars, G., Mars, V., and Ciccarone, D. (2023). The high five Club’: social relations and perspectives on HIV-related stigma during an HIV outbreak in West Virginia. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 47, 329–349. doi: 10.1007/s11013-022-09769-2

Mazzarella, W. (2024) in Populist leadership and charisma. eds. Y. Stavrakakis and G. Katsambekis (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 291–302.Research Handbook on Populism

McAdams, D. P. (2021). The episodic man: how a psychological biography of Donald J. Trump casts new light on empirical research into narrative identity. Eur. J. Psychol. 17, 176–185. doi: 10.5964/ejop.4719

McDonnell, D. (2016). Populist leaders and coterie charisma. Polit. Stud. 64, 719–733. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12195

McGraw, M., and Stein, S. (2021). It’s been exactly one year since Trump suggested injecting bleach. Politico.com, 23 April. Available online at: https://www.politico.com/news/2021/04/23/trump-bleach-one-year-484399

Miscoiu, S. (2012). Au Pouvoir par le Peuple: Le Populisme Saisi par la Théorie du Discours. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Mols, F., and Jetten, J. (2020). Understanding support for populist radical right parties. Front. Commun. 5:57561. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.557561

Monahan, B., and Maratea, R. J. (2021). The art of the spiel: analyzing Donald Trump's tweets as Gonzo storytelling. Symbolic Interact. 44, 699–727. doi: 10.1002/symb.540

Moynihan, D., and Roberts, A. (2021). Dysfunction by design: Trumpism as administrative doctrine. Public Adm. Rev. 81, 152–156. doi: 10.1111/puar.13342

Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Gov. Oppos. 39, 541–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

Müller, J. W. (2021). All quiet on the populist front? Project Syndicate, 21 January. Available online at: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/trump-and-the-fate-of-populist-authoritarian-leaders-worldwide-by-jan-werner-mueller-2021-01.

Muno, W., and Pfeiffer, C. (2022). Populism in power: a comparative analysis of populist governance. Int. Area Stud. Rev. 25, 261–279. doi: 10.1177/22338659221120067

Nai, A., Martínez Coma, F., and Maier, J. (2019). Donald Trump, populism, and the age of extremes: comparing the personality traits and campaigning styles of Trump and other leaders worldwide. President. Stud. Q. 49, 609–643. doi: 10.1111/psq.12511

Nai, A., and Martínez i Coma, F. (2019). The personality of populists: provocateurs, charismatic leaders, or drunken dinner guests? West Eur. Polit. 42, 1337–1367. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2019.1599570

Nelson, D. R. (2019). Facing up to Trump administration mercantilism. World Econ. 42, 3430–3437. doi: 10.1111/twec.12875

O’Brien, R. C. (2024). The return of peace through strength: making the case for Trump’s foreign policy. Foreign Aff. 103, 24–38.

Ostiguy, P. (2017). “Populism: a socio-cultural approach” in The Oxford handbook of populism. eds. R. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 73–97.

Ott, B. L., and Dickinson, G. (2020). The twitter presidency: how Donald Trump's tweets undermine democracy and threaten us all. Polit. Sci. Q. 135, 607–636. doi: 10.1002/polq.13129

Pappas, T. S. (2016). Are populist leaders “charismatic”? The evidence from Europe. Constellations 23, 378–390. doi: 10.1111/1467-8675.12233

Pearce, C. L., Sims, H. P. Jr., Cox, J. F., Ball, G., Schnell, E., Smith, K. A., et al. (2003). Transactors, transformers and beyond: a multi-method development of a theoretical typology of leadership. J. Manage. Dev. 22, 273–307. doi: 10.1108/02621710310467587

Perri 6Richards, P. (2017). Mary Douglas: Understanding social thought and conflict. Oxford: Berghahn.

Perri 6Swedlow, B. (2016). Symposium: An institutional theory of cultural bias, public administration and public policy. Public Admin. 94, 863–1163. doi: 10.1111/padm.12296

Pirro, A. L., and Taggart, P. (2023). Populists in power and conspiracy theories. Party Polit. 29, 413–423. doi: 10.1177/13540688221077071

Plenta, P. (2020). Conspiracy theories as a political instrument: utilization of anti-Soros narratives in Central Europe. Contemp. Polit. 26, 512–530. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2020.1781332

Poblete, M. E. (2015). How to assess populist discourse through three current approaches. J. Polit. Ideol. 20, 201–218. doi: 10.1080/13569317.2015.1034465

Prasad, A. (2020). The organization of ideological discourse in times of unexpected crisis: explaining how COVID-19 is exploited by populist leaders. Leadership 16, 294–302. doi: 10.1177/1742715020926783

Przeworski, A. (2023). Formal models of authoritarian regimes: a critique. Perspect. Polit. 21, 979–988. doi: 10.1017/S1537592722002067

Rayner, S. (1992). “Cultural theory and risk analysis” in Social theories of risk. eds. S. G. Krimsky and D. Golding (Westport, CN: Praeger), 83–115.

Restuccia, A. (2019) Trump's ‘most transparent president’ claim looks cloudy. Politico.com, 23 May. Available online at: https://www.politico.com/story/2019/05/23/trumps-transparency-1342875.

Roberts, R. (2016). I sat next to Donald Trump at the infamous 2011 White House correspondents’ dinner. Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/i-sat-next-to-donald-trump-at-the-infamous-2011-white-house-correspondents-dinner/2016/04/27/5cf46b74-0bea-11e6-8ab8-9ad050f76d7d_story.html (Accessed January 27, 2025)

Sachweh, P. (2020). Social integration and right-wing populist voting in Germany. Anal. Krit. 42, 369–398. doi: 10.1515/auk-2020-0015

Saletan, W. (2016). How Trump’s “unpredictability” dodge became the dumbest doctrine in politics. Slate.com, 3 May. Available online at: https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2016/05/trumps-moronic-unpredictability-doctrine.html.

Schwarz, M., and Thompson, M. (1991). Divided we stand. Philadelphia, PN: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Seawright, J. (2016). The case for selecting cases that are deviant or extreme on the independent variable. Sociol. Methods Res. 45, 493–525. doi: 10.1177/0049124116643556

Seawright, J., and Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research: a menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Polit. Res. Q. 61, 294–308. doi: 10.1177/1065912907313077