- 1Department for Democracy and Political Theory, Institute for Political Science, Hungarian Research Network (HUN-REN) Centre for Social Sciences, Budapest, Hungary

- 2Department of Political Science, Institute of Social and Political Science, Corvinus University of Budapest, Budapest, Hungary

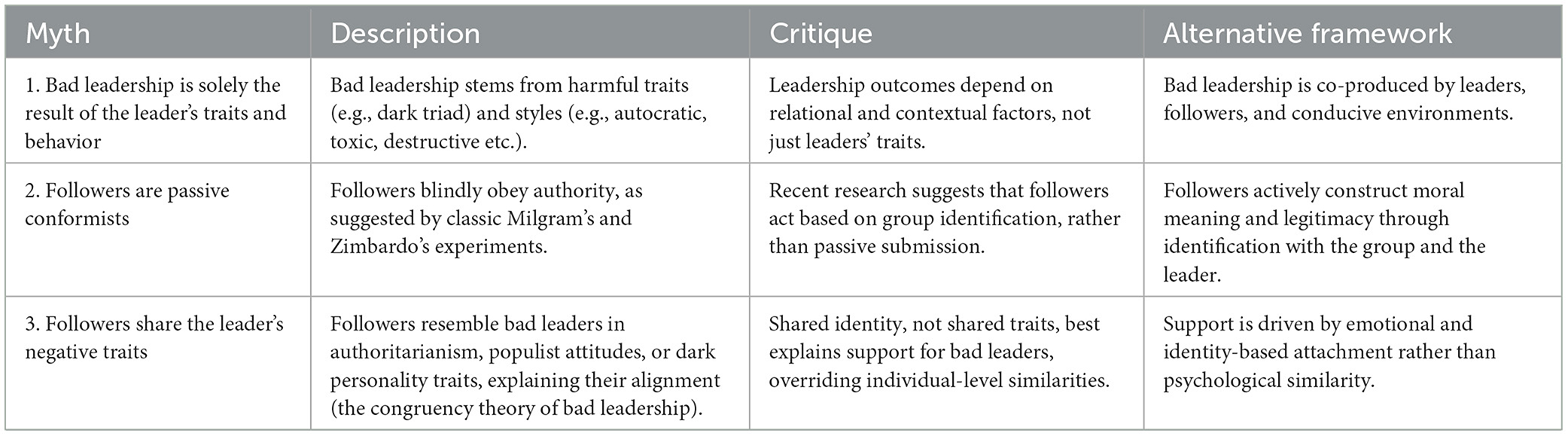

Introduction: Scholarship on bad leadership remains dominated by leader-centric paradigms that overstate the explanatory power of individual traits while neglecting the relational and identity-based processes that sustain harmful authority. This study challenges three influential myths: that bad leadership stems solely from leader pathology, that followers are passive conformists, and that support arises from psychological similarity between leaders and followers.

Methods: Through a critical and conceptual review of political science and social psychology literature, the study integrates conceptual and empirical findings to reassess prevailing assumptions about bad leadership and followership.

Results: The analysis reveals that bad leadership is not a deviation from normal leadership but an expression of its underlying dynamics. Harmful leadership emerges through interactive processes among leaders, followers, and permissive environments. Followers are not merely obedient or trait-aligned individuals; rather, they actively co-produce legitimacy through engaged followership based on identification and identity leadership. Individual-level dispositions such as authoritarianism, populism, or dark personality traits influence leader tolerance primarily within the framework of group identity and ideological alignment.

Discussion: The findings challenge simplistic narratives of deviance and emphasize the central role of shared identity, group prototypicality, and affective polarization in shaping moral judgment and political legitimacy. Norm violations by in-group leaders are more likely to be tolerated or justified, particularly when perceived as benefiting the group. Future research should further explore the interaction between personality, identity, and institutional context in enabling or constraining bad leadership.

1 Introduction

While character assassination, name-calling, and scapegoating have long been embedded in political discourse, their prevalence has intensified in modern mediatized democracies. Politicians now routinely deploy these tactics to frame opponents as flawed or incompetent, often disregarding factual accuracy. Negative personalization increasingly overshadows positive leader evaluation, reflecting broader trends in voter behavior (Garzia and Ferreira da Silva, 2021, 2022). In polarized contexts, such attacks often draw on scientific-sounding labels and psychological diagnoses. The 2024 U.S. presidential race, for example, revolved around debates about the candidates' cognitive fitness, echoing institutional frameworks like the 25th Amendment (Smith et al., 2024). In populist regimes, similar tactics serve to delegitimize challengers: in Hungary, for instance, opposition figure Péter Magyar was portrayed through psychiatric language and moral disqualification. These cases exemplify how political discourse is increasingly weaponized through psychological and moral framing to exclude opponents from legitimacy.

Less often discussed is the negative romanticization of leadership, the tendency to demonize individuals as scapegoats for collective failures, when they are perceived to lack key skills or possess undesirable traits (Bligh et al., 2007). The seminal works of Meindl et al. (1985) have highlighted a pervasive attributional bias in society, the media, and leadership scholarship: the tendency to overemphasize leaders as the primary source of both success and failure. This insight laid the groundwork for the post-heroic turn in leadership studies, which aimed to decenter the leader and foreground relational dynamics. However, despite this paradigmatic shift, leader-centrism persists, even in critical and post-heroic frameworks, through the continued idealization of certain leadership forms, whether ethically pure or collective, and of exemplary follower types (Collinson et al., 2018). This moral idealization has, paradoxically, heightened scholarly sensitivity to the darker sides of leadership, which are now often explored not only as threats to be managed but as moral inversions of the heroic ideal. As a result, the study of “bad leadership” frequently carries an implicit or explicit ambition to expose and neutralize perceived harm.

Ironically, leader-centrism persists in contemporary discourse, albeit now framed in a predominantly negative light (cf. Padilla et al., 2007; Thoroughgood et al., 2012, 2018). Since the early 2000s, leadership studies have grappled with palpable anxiety, reflected in strong reactions to controversial political figures (e.g., George W. Bush, Tony Blair, Donald Trump) and high-profile corporate scandals (e.g., Enron, Madoff, Theranos). This renewed scrutiny has revived interest in authoritarian leadership research (Harms et al., 2018), while the specter of 20th-century traumas, often encapsulated in references to “Hitler's ghost” (Kellerman, 2000), continues to shape leadership discourse, symbolizing the perceived dangers of unchecked power. Recent scholarship has increasingly employed narrative analysis (e.g., Kellerman, 2004, 2024; Lipman-Blumen, 2006) alongside a rise in quantitative studies (Harms et al., 2018; Camgoz and Karapinar, 2021). However, both approaches often lack robust theoretical foundations, resulting in competing labels and inconsistent integration of traits and behaviors. Some scholars have shifted from simply asking, “What constitutes bad leadership?” to deeper inquiries: “Why do free individuals willingly support leaders perceived as curtailing their freedoms?” (Lipman-Blumen, 2006) and “How does harmful behavior become celebrated?” (Reicher et al., 2008). Despite these efforts, the paradox remains: a leader deemed toxic by some may simultaneously be revered as a hero or idol by others.

This theoretical and conceptual investigation is grounded in the premise that bad leadership functions through the exact relational and identity-driven mechanisms as good leadership, an unsettling recognition that exposes the inner mechanics of leadership itself. Rather than treating bad leadership as a deviation from the norm, I approach it as an expression of leadership's core dynamics: the interplay between leaders and followers, embedded in shared perceptions of competence, morality, and legitimacy. Leadership, in this view, is not reducible to supervision, authority, management, or headship; it hinges on voluntary followership (Grint, 2005; Kort, 2008), on individuals aligning themselves with a leader's vision and accepting their claim to represent the group. This alignment may be sincere or manipulated, ethical or fraught with ethical concerns, but it is always negotiated within the context of the relationship.

Instead of displacing moral questions onto adjacent domains, such as administration or governance, I examine how leadership participants actively navigate normative tensions. Even in enclosed settings, such as military units, organizations, or sports teams, leadership cannot be said to occur where voluntary compliance is absent. In democratic systems, this condition of negotiated legitimacy renders leadership both essential and inescapable (Metz, 2021). Thus, bad leadership is not an aberration but a relational outcome that becomes durable when followers uphold it as legitimate, even in the face of norm violations or moral compromise.

Accordingly, this study defines bad leadership as a relational and context-dependent phenomenon in which leaders, followers, and environments co-produce harmful leadership outcomes through dynamics of social identity. It is not reducible to individual traits or leadership styles but emerges where legitimacy is sustained despite ethical or democratic violations.

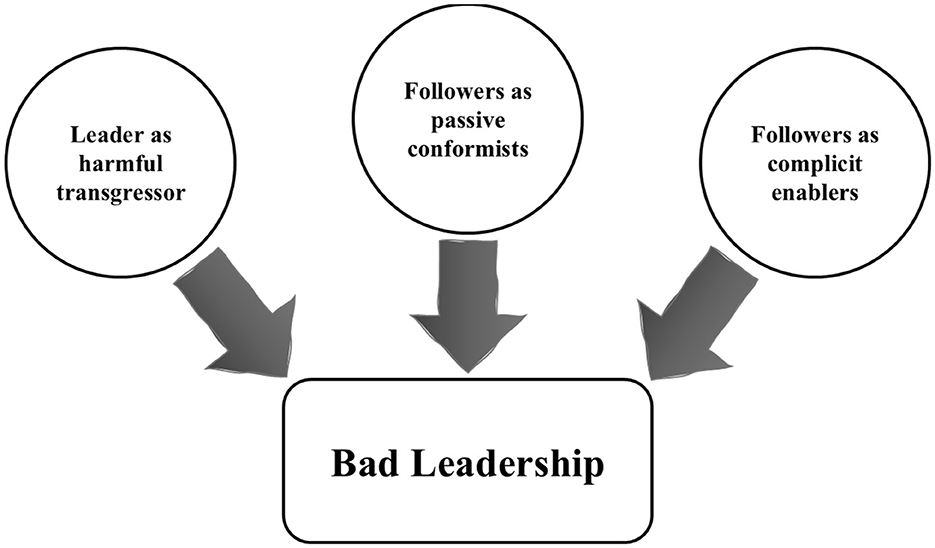

This study aims to debunk three persistent myths that continue to distort our understanding of harmful leadership (Figure 1). The first myth posits that bad leadership can be entirely attributed to a leader's perceived or actual traits and behavior (Kellerman, 2004, 2024; Lipman-Blumen, 2006). While it is tempting to rely on these diagnostic categories to make sense of troubling political or corporate figures, this leader-centric approach suffers from both ethical and analytical limitations: it obscures the relational, institutional, and symbolic conditions that sustain harmful leadership in the first place.

The second myth portrays followers as inherently passive or conformist, a view popularized through loose readings of Hannah Arendt's “banality of evil” thesis and reinforced by the canonical experiments of Milgram (1974) and Zimbardo (2007). These experiments continue to anchor discussions of obedience and complicity in leadership failure (Kellerman, 2004, 2024; Lipman-Blumen, 2006; Thoroughgood et al., 2012, 2018; Tourish, 2013; e.g., Harms et al., 2018; Örtenblad, 2021). Yet recent scholarship in social psychology has challenged this narrative, arguing that obedience is often less about blind submission and more about active identification with a perceived legitimate authority and shared group mission and identity (Haslam et al., 2019; Birney et al., 2024).

The third myth suggests that followers mirror the negative traits of bad leaders, that they are drawn to them because of shared authoritarian personality (Harms et al., 2018), dark personality traits (Paulhus and Williams, 2002; Nai and Toros, 2020), or populist worldviews (Nai, 2022; Lewandowsky and Jankowski, 2023). However, as empirical findings show, followers do not need to resemble their leaders psychologically in order to support them, they need only to perceive them as representative of the group.

Taken together, these myths deflect attention from the relational and contextual mechanisms that allow harmful leadership to emerge and persist. Their persistence is not merely an academic concern: by obscuring the structural and identity-based conditions that sustain harmful authority, they can lead to misguided diagnoses, misplaced interventions, and a dangerous underestimation of the societal costs associated with legitimized norm violations. By rejecting essentialist explanations and shifting the focus to identification and legitimacy, this study offers a framework for understanding bad leadership not as an individual pathology but as a social and political construction—one that, if misunderstood, risks eroding accountability, fostering cynicism, and entrenching authoritarian dynamics under the guise of leadership competence.

2 The first myth: bad leadership as a sole product of leaders' traits and behaviors

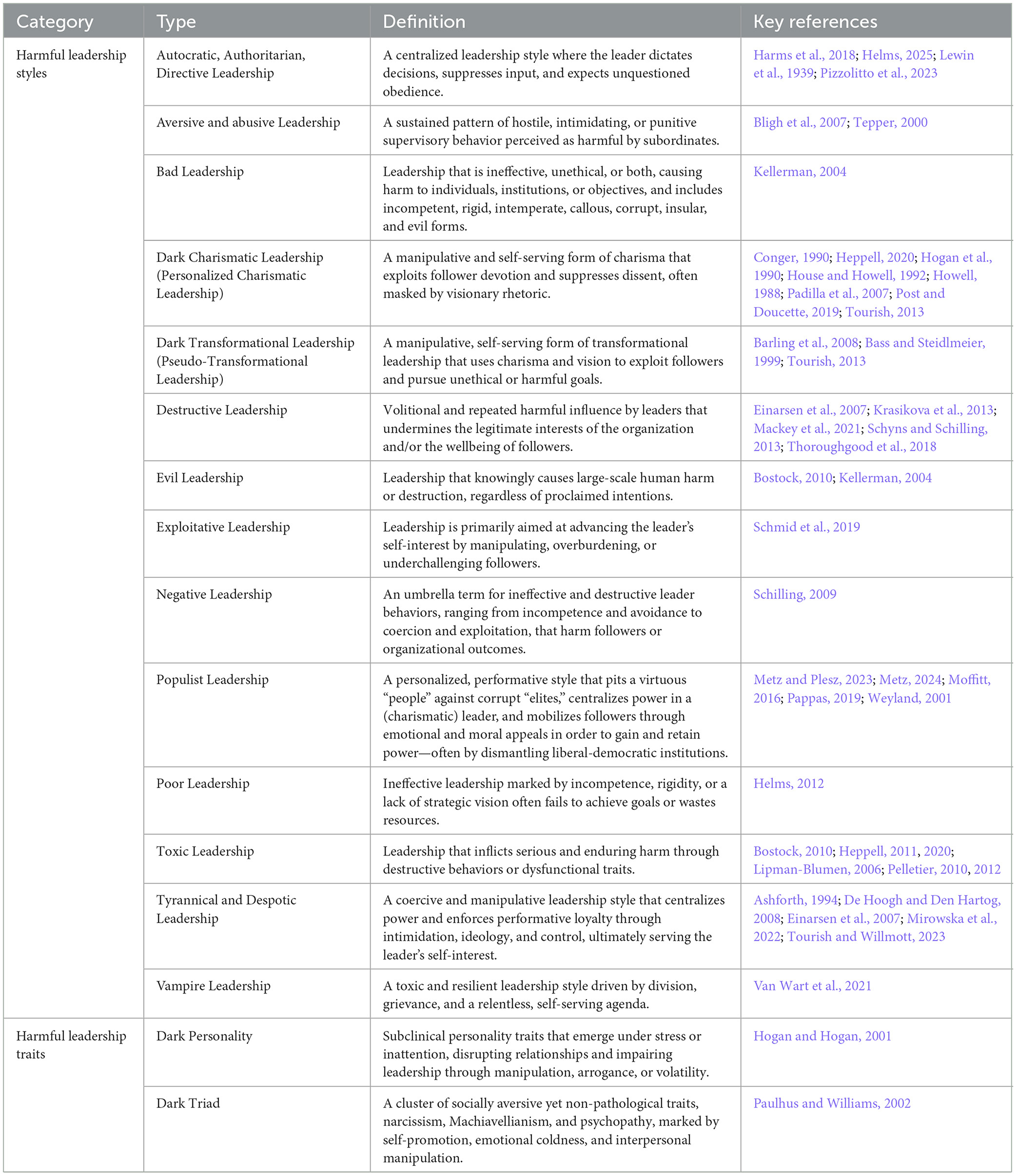

The concept of bad leadership has been interpreted through various lenses (Table 1), shaped by the abundance of historical and contemporary examples available for analysis. While research on leadership's “dark side” has generated valuable theoretical insights, it also warns against reducing complex relational processes to a one-dimensional framework. In this section, I outline the primary conceptual strands that dominate the field: harmful leadership styles, including autocratic, pseudo-transformational/personalized charismatic, populist, and destructive leadership, as well as harmful leader traits, most notably the Dark Triad. Rather than offering a comprehensive typology, my goal is to interrogate the assumptions underlying these categories, examine their conceptual overlaps, and highlight their limitations, particularly in relation to the concept of political leadership.

Autocratic leadership, long associated with authoritarian regimes, represents one of the earliest and most studied forms of harmful leadership (Harms et al., 2018; Helms, 2025). Seminal work by Lewin et al. (1939) laid the empirical foundation for assessing leadership styles, contrasting authoritarian control with democratic engagement. Their experiments showed that while autocratic leadership could drive short-term productivity under close supervision, it fostered passivity, scapegoating, and dependence, dynamics that quickly unraveled in the leader's absence. These findings not only exposed the fragility of authoritarian systems but also elevated democratic leadership as a normative ideal. Yet despite declining scholarly attention since the 1980s, autocratic leadership continues to thrive in various political and organizational settings (Harms et al., 2018). The systematic literature review by Pizzolitto et al. (2023) adds important nuance to this puzzle by examining how authoritarian leadership functions within micro-level workplace contexts. Their findings reveal that while Western research tends to emphasize the negative outcomes of authoritarian, autocratic, and directive leadership, such as diminished trust, emotional suppression, and disengagement, Eastern studies point to context-dependent effectiveness, particularly within paternalistic environment. Rather than being universally harmful, authoritarian styles appear sensitive to team dynamics, cultural values, and situational demands. This challenges the optimistic assumption that democratic norms naturally displace authoritarian preferences, raising a more difficult question: why do individuals and groups still gravitate toward leaders who demand obedience over participation?

One of the pivotal insights of the post-heroic turn was the growing recognition that charisma (Howell, 1988; Conger, 1990; Hogan et al., 1990; House and Howell, 1992; Padilla et al., 2007; Tourish, 2013; Post and Doucette, 2019; Heppell, 2020) and transformation (Bass and Steidlmeier, 1999; Barling et al., 2008; Tourish, 2013), once celebrated as the essence of inspirational leadership, could also operate as vehicles for manipulation, coercion, and norm violation. This strand of critique has drawn particular attention to the distinction between socialized and personalized charisma (Howell, 1988; House and Howell, 1992): while the former channels influence toward collective and egalitarian goals, the latter reinforces self-glorification, control, and authoritarian tendencies. As Conger (1990) and Conger and Kanungo (1998) show, the charismatic leader's visionary appeal can easily be weaponized to suppress dissent and demand unconditional loyalty. This concern also informs the literature on pseudo-transformational leadership, which refers to leaders who adopt the appearance of transformational influence but ultimately pursue unethical, self-serving ends (Bass and Steidlmeier, 1999; Barling et al., 2008). These figures initially offer individualized attention and moral rhetoric, only to shift toward coercion once trust has been secured. In political contexts, such deviations often intersect with populist rhetoric, where charismatic authority merges with anti-elitist performance and exclusionary moral claims (Metz and Plesz, 2023; Metz, 2024; Pappas, 2019). Whether defined as a performative style (Moffitt, 2016) or a strategic logic (Weyland, 2001), populism relies on sharp moral binaries that mobilize “the people” against elites and perceived out-groups, including ethnic and sexual minorities, thus creating fertile ground for norm erosion under the guise of popular empowerment.

The concept of destructive leadership has emerged as an umbrella framework for capturing a wide range of harmful behaviors and traits that produce adverse outcomes for followers, organizations, or both. While the term is conceptually expansive, it has proved useful in organizing diverse manifestations of “bad” leadership under a single analytic lens. Notably, much of this literature draws on high-profile political figures, such as George W. Bush, Tony Blair, Silvio Berlusconi, Robert Mugabe, or Fidel Castro, as illustrative cases (Lipman-Blumen, 2006; Padilla et al., 2007; Heppell, 2011, 2020). These examples underscore the political salience of destructive leadership, yet the concept remains underutilized in mainstream political science debates (Heppell, 2011, 2020; Helms, 2012). In recent years, political developments such as populism, presidentialization and personalization, illiberalism, and affective polarization have drawn renewed attention to the dark side of leadership. Yet, despite its growing political relevance, the scholarly examination of bad leadership in political science remains fragmented and underdeveloped. As Helms (2012) notes, the discipline has traditionally focused more on the “ineffective” or “poor” side of leadership, failures of competence or policy delivery, than on its destructive or unethical dimensions. This gap is particularly striking given the extent to which leadership failures contribute to institutional decay, democratic erosion, and geopolitical instability.

At the same time, empirical research on destructive leadership has predominantly focused on organizational and workplace contexts, where methodological control is more feasible (Camgoz and Karapinar, 2021). While this has yielded important insights into abusive supervision and toxic team dynamics, it has also narrowed the field's analytic scope, often sidelining the systemic and symbolic dimensions of political leadership. What remains underdeveloped is a framework that can bridge the micro-dynamics of leader-follower relations with the macro-contexts of political authority and institutional legitimacy.

Some of the most influential contributions to the study of leadership's dark side have deliberately eschewed empirical precision in favor of narrative interpretation (Kellerman, 2004, 2024; Lipman-Blumen, 2006). These works have been pivotal not despite, but because of, their refusal to constrain bad leadership within narrow typologies. In contrast, a growing body of research has attempted to reconceptualize and systematize the field through empirical and theoretical refinement (Einarsen et al., 2007; Schilling, 2009; Krasikova et al., 2013; Schyns and Schilling, 2013; Thoroughgood et al., 2018; Mackey et al., 2021).

Despite divergent terminologies and methodological strategies, these efforts converge around a relatively stable conceptual terrain. Frameworks range from aversive/abusive leadership (Tepper, 2000; Bligh et al., 2007), bad leadership conceptualized as a spectrum from incompetence to unethical behavior (Kellerman, 2004), evil leadership (Kellerman, 2004; Bostock, 2010), exploitative leadership (Schmid et al., 2019), negative leadership (Schilling, 2009), toxic leadership (Lipman-Blumen, 2006; Bostock, 2010; Pelletier, 2010, 2012; Heppell, 2011, 2020), tyrannical/despotic leadership (Ashforth, 1994; Einarsen et al., 2007; De Hoogh and Den Hartog, 2008; Mirowska et al., 2022; Tourish and Willmott, 2023), and vampire leadership (Van Wart et al., 2021), to broader integrative constructs such as destructive leadership (Einarsen et al., 2007; Krasikova et al., 2013; Schyns and Schilling, 2013; Thoroughgood et al., 2018; Mackey et al., 2021). Across this literature, a shared recognition emerges: destructive leadership is not a one-off aberration but a sustained and systemic pattern of harm. It is a process embedded in organizational or political structures, made durable through the complicity of followers and institutional permissiveness. Understanding it, therefore, requires moving beyond isolated labels and toward an integrated perspective on how harm is relationally enacted, legitimized, and reproduced over time.

Among the more comprehensive approaches, the toxic triangle model proposed by Padilla et al. (2007) and further developed by Thoroughgood et al. (2018) remains especially influential. It shifts attention from individual pathology to a relational framework, emphasizing the interaction of three elements: toxic leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments. This model highlights that destructive leadership is rarely the result of leader traits alone; it is co-produced and sustained through compliance, complicity, and contextual factors. Yet, despite this advance, the field remains fragmented, with overlapping constructs and blurred conceptual boundaries that complicate theoretical clarity and empirical comparability (Mackey et al., 2021).

At the turn of the 21st century, scholarly attention turned increasingly toward the “dark side” of leadership personality (Hogan and Hogan, 2001; Paulhus and Williams, 2002). Hogan and Hogan (2001) introduced the concept of “dark personality” into organizational science, emphasizing the role of subclinical derailers—idiosyncratic traits that may not meet diagnostic criteria but nonetheless distort professional behavior. Although such characteristics can offer short-term advantages in competitive or high-pressure contexts, the Hogans argued that their long-term effects are typically corrosive, undermining trust, performance, and cohesion.

In political science, Paulhus and Williams' (2002) concept of the Dark Triad, narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy, has been widely adopted to analyze political leadership and its societal impacts—these traits, while subclinical, are linked to manipulative, ethically questionable, and socially aversive behavior. Narcissism reflects grandiosity and a hunger for admiration; Machiavellianism denotes strategic manipulation and distrust; psychopathy involves impulsivity, lack of empathy, and antisocial tendencies (see also Rauthmann, 2012). The framework was later expanded to include sadism as a fourth dimension, forming the Dark Tetrad (Paulhus, 2014), and has inspired further extensions, such as the “Dark Tent,” which encompasses traits like paranoia and hubristic pride (Marcus and Zeigler-Hill, 2015).

Despite this conceptual proliferation, the field remains faced with unresolved theoretical and methodological tensions. Chief among these is the absence of clear criteria for inclusion, which has led to overlapping constructs, such as the ongoing debate over the redundancy of psychopathy and Machiavellianism (Miller et al., 2019; Kowalski et al., 2021). These ambiguities complicate both empirical measurement and the interpretability of findings.

Nevertheless, dark traits appear disproportionately among political elites. Narcissism, in particular, alongside psychopathy and Machiavellianism to a lesser extent, has been shown to correlate with political ambition, success, and performance (Lilienfeld et al., 2012; Watts et al., 2013; Blais and Pruysers, 2017; Nai, 2019; Pfeffer, 2021; Peterson and Palmer, 2022). Some studies suggest that U.S. presidents score higher on narcissism and psychopathy than the general population, and that these traits may even predict leadership effectiveness (Lilienfeld et al., 2012; Watts et al., 2013). Moreover, populist and authoritarian leaders, such as Putin, Trump, Bolsonaro, Erdogan, Orbán, Duterte, and Netanyahu, exhibit significantly higher Dark Triad scores than their mainstream counterparts (Nai and Martínez i Coma, 2019; Nai and Toros, 2020). These findings suggest that such traits, although potentially functional in achieving power, may also simultaneously erode democratic norms.

Still, the robustness of these claims is limited by the reliance on expert assessments and public perceptions (Lilienfeld et al., 2012; Nai and Maier, 2021b). Self-reported data remain rare. An exception is Maier et al. (2022), who analyzed German state-level candidates using the Political Elites Aversive Personality Scale (PEAPS). Their findings show that younger, more ideologically extreme, and right-leaning candidates scored higher on narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Although overall scores were moderate, they were notably higher than those of the general population, albeit lower than expert estimations of national-level elites (Maier et al., 2022, p. 355).

Beyond their theoretical and methodological limitations (Harms et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2019; Kowalski et al., 2021), leader-centered explanations of harmful leadership face three further challenges. First, they rely heavily on subjective evaluations of political actors. In the case of dark triadic traits, both expert and lay assessments are often shaped by the evaluator's ideological orientation and worldview (Wright and Tomlinson, 2018; cf. Nai and Maier, 2021a). This means that perceptions of narcissism, Machiavellianism, or psychopathy are not simply derived from observable behavior but are filtered through partisan and cognitive biases. These interpretive distortions are further amplified in polarized environments, where shared identity with the leader can insulate them from criticism, while opposition figures are disproportionately blamed for adverse outcomes (Giessner et al., 2009; Krishnarajan, 2023; Davies et al., 2024). As Bligh et al. (2007) argue, bad leadership is a social construct, produced not only by leaders' actions but by followers' attributions and emotional investments. The psychological literature offers a parallel insight in the form of the “horn effect,” whereby negative traits color overall evaluations more strongly than is warranted (Forgas and Laham, 2022).

Second, applying pathological frameworks to political leaders, even under the guise of subclinical traits (Paulhus and Williams, 2002) or “political personality profiles” (Post and Doucette, 2019), raises serious ethical and epistemological concerns. This tension is institutionalized in the Goldwater Rule, a guideline issued by the American Psychiatric Association that prohibits diagnosing public figures without first conducting a direct clinical examination and obtaining their consent. The rule emerged after the 1964 presidential campaign, when Fact magazine published the results of a controversial survey of psychiatrists on Barry Goldwater's mental fitness. Despite inconclusive data, the article labeled him with various personality disorders, prompting backlash over the politicization of psychiatric authority. The episode serves as a cautionary tale about speculative diagnoses in political discourse, highlighting the potential damage not only to the individuals involved but also to public trust in mental health expertise.

Since 2016, debates around Donald Trump's perceived mental fitness have reignited longstanding tensions over the role of psychological expertise in public discourse. While psychiatry remains bound by ethical constraints such as the Goldwater Rule, which forbids diagnosing public figures without direct examination, psychology often operates with looser standards (Lilienfeld et al., 2018a,b). The problem, however, is not merely one of professional boundaries, but of empirical uncertainty. In an era of media saturation and impression management, distinguishing between authentic traits and carefully crafted public images becomes increasingly challenging. As a result, psychological speculation risks collapsing the boundary between science and partisanship, turning potentially valuable diagnostic frameworks into instruments of character assassination. The recent public discourse surrounding Trump, Biden, and Magyar exemplifies how questions of mental fitness are often invoked less for diagnostic insight than for political effect, typically in the absence of rigorous evidence.

The last, but equally pressing criticism concerns the normative architecture that underlies much of leadership theory. The field often operates with implicit ideals of what leadership should be, constructing typologies in binary opposition to negatively coded styles. Lewin's democratic and autocratic leadership dichotomy (Lewin et al., 1939) and Bass's contrast between authentic and pseudo-transformational leadership (Bass and Steidlmeier, 1999) are emblematic examples. Burns' (2003) ideal of “transforming leadership” has likewise served as an implicit or explicit moral benchmark in later critiques of bad leadership (Kellerman, 2004; Nye, 2008). Even scholars who focus on toxic leadership, such as Jean Lipman-Blumen, retain normative commitments, her ideal of “connective leadership” (Lipman-Blumen, 2000) remains underexplored compared to her critique of destructive styles (Lipman-Blumen, 2006). Her contrasting evaluations of George W. Bush and Barack Obama in 2009 illustrate how such ideals often map directly onto political preference (Lipman-Blumen, 2009a,b).

These normative assumptions also shape how traits like narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy are interpreted in political contexts. While frequently pathologized, these traits often correlate with political ambition, leadership drive, and participation (Chen et al., 2021; Peterson and Palmer, 2022). As Pfeffer (2021) notes, the paradox lies in the fact that traits deemed socially undesirable may in fact be functional, or even necessary, in high-stakes, conflict-driven political arenas. This calls for greater conceptual nuance: not all “dark” traits lead to destructive leadership, and not every deviation from normative expectations signals dysfunction. Rather than moralizing these traits, we should analyze their effects in relation to specific institutional and cultural contexts.

Despite some acknowledgment of their adaptive potential, the dominant view in literature remains largely critical. Many scholars argue that Dark Triad traits are inherently associated with immoral behavior. Kay and Saucier (2020) distill this position into two hypotheses: first, that individuals with dark characteristics are unable to make moral judgments; and second, that they can distinguish right from wrong but consciously prioritize self-interest over ethics. Their findings complicate both claims. While individuals high in psychopathy did show impaired moral reasoning, no such pattern was found for Machiavellianism or narcissism. Although Kay and Saucier stop short of drawing definitive conclusions, their study challenges the assumption that all dark traits uniformly lead to unethical behavior and invites a more differentiated, evidence-based approach to linking personality and morality in political life.

These findings highlight a broader limitation of the trait-based approach: it tends to isolate individual psychology from the structural and relational forces that shape political behavior. Focusing narrowly on personality risks obscuring how context, especially institutional design, social norms, and group dynamics, amplifies or mitigates the expression of bad leadership. To fully understand the conditions under which bad leadership flourishes, we must move beyond the individual level and examine how political environments interact with personality, identity, and followership. At the same time, attributing co-responsibility to followers and environments should not be mistaken for diminishing leader accountability. Rather, this perspective enriches our understanding of how harmful leadership becomes legitimized by illuminating the broader ecology of complicity without excusing the originating agency of leaders themselves.

While much of the literature on bad leadership focuses on individual traits or behaviors, it is crucial to account for the broader institutional and political environment that constrains or enables bad leadership. Political leadership research has traditionally been strongly institution/position-centric (Metz, 2024), emphasizing formal rules, structures, and regime types regarding bad leadership (Diamond, 2002; Wigell, 2008; Bogaards, 2009; Levitsky and Way, 2010; Brancati, 2014; Mufti, 2018; Pappas, 2019; Larres, 2021; Sinkkonen, 2021) while often underestimating the relational dynamics between leaders and followers. Padilla et al.'s (2007) toxic triangle model emphasizes that destructive leadership rarely emerges in isolation: it arises through the confluence of harmful leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments. While this model was developed in the context of organizational behavior, its insight—that context co-produces leadership outcomes—is particularly relevant to politics. Political environments are not neutral containers; they are dynamically shaped by the leaders and followers they host.

In well-established democracies, institutional robustness and entrenched norms may slow the rise of bad leadership, yet, as Levitsky and Ziblatt (2019) argue, democracy today is less often overthrown than hollowed out from within. As Helms (2025) demonstrates, the personalization of executive leadership across Western and non-Western democracies facilitates such erosion by concentrating authority in the hands of charismatic figures while weakening the mediating functions of parties and legislatures. This tendency is even more pronounced in new or unconsolidated democracies, where institutional fragility, clientelism, and limited democratic experience provide fertile ground for populist appeals and executive aggrandizement. These developments are compounded by trends identified by Poguntke and Webb (2018), namely, the presidentialization and personalization of democratic politics—where the former refers to the increasing concentration of executive power, visibility, and autonomy in the hands of political leaders, even within parliamentary systems, while the latter denotes the growing emphasis on individual leaders over parties, programs, or collective decision-making processes, often driven by media dynamics and voter preferences for recognizable and emotionally resonant figures. These shifts hollow out traditional party government and elevate individual leaders above collective accountability mechanisms. When combined with populism and affective polarization, personalization facilitates an emotionally charged, identity-driven, and norm-flexible rule. Institutions may persist formally in such systems, but their normative authority and balancing functions are often bypassed or neutralized. In such contexts, leadership is not merely constrained by institutions, it can actively reshape them. Drawing on Skowronek's theory of reconstructive leadership, Illés et al. (2018) show how leaders like Orbán not only erode constitutional norms but also establish new political regimes when backed by sufficiently strong follower mandates.

Leaders do not merely inherit political contexts, they reinterpret, dramatize, and at times actively generate crises to justify exceptional authority. As Körösényi et al. (2016) argue, contemporary leadership, especially in personalized and mediatized environments, relies on the performative framing of crises, their redefinition, and emotional mobilization. Populist leaders are particularly skilled in this regard: they recast opposition as an existential threat, turn institutions into symbols of elite obstruction, and present themselves as the sole embodiment of the popular will. In doing so, they erode pluralism and institutional constraints while claiming to restore democracy on behalf of a betrayed people (Mounk, 2018; Pappas, 2019).

Importantly, the emergence of bad leadership cannot be disentangled from the role of followers. As this study contends, bad leadership is not merely the product of deviant personalities; it is co-produced through the legitimation of norm violations by identity-aligned followers in permissive political environments. Bartels (2023) provides compelling evidence that democratic erosion in Europe is primarily driven “from the top” by populist elites, but sustained “from below” by voters who tolerate, rationalize, or even celebrate illiberal policies when framed as expressions of group identity or moral reparation.

This dynamic holds across regime types but takes on distinct forms depending on institutional strength. In newer democracies, where democratic norms are less deeply rooted and institutions less consolidated, bad leadership thrives without a cohesive societal majority committed to liberal rules of the game. Yet even in established democracies, institutional strength is not always sufficient to resist transgression, especially when emotionally polarized followers perceive constraints on leadership not as democratic safeguards but as illegitimate obstacles to their group's empowerment.

Ultimately, understanding bad leadership requires us to move beyond leader-centric and institutionalist frameworks toward a more relational view: followers actively shape political outcomes by legitimizing or resisting leadership claims. Citizens do not merely operate within democratic institutions; they determine whether those institutions endure, evolve, or collapse. As this study argues, the fate of democracy depends not only on its formal architecture but on whether followers continue to treat institutions as legitimate constraints or authorize their dismantling by leaders who claim to embody the people's will.

3 The enablers: from passive conformists to active accomplices

Scholarship on bad leadership often echoes the age-old adage that “people get the leaders they deserve,” implying that bad followers enable bad leaders and hinder the effectiveness of good ones (Nye, 2008, p. 135). This view has been accompanied by a new normative ideal of the follower, proactive, critical, yet unwaveringly loyal to “good” leadership. This construct stands in sharp contrast to traditional depictions of followership, which have long been associated with obedience, passivity, and conformity, traits now increasingly viewed as symptoms of bad followership.

Most frameworks categorize followers of bad leaders into two broad types: conformists and colluders (Padilla et al., 2007). Conformists exhibit passive and unquestioning loyalty, often driven by unmet psychological needs, fear, or a desire for dependency. Lipman-Blumen (2006) describes these as “benign followers,” credulous individuals motivated more by pragmatism than ideology. Thoroughgood et al. (2012) further differentiate conformists into three subtypes: “lost souls,” who seek protection and identity; “bystanders,” who remain disengaged due to indifference or fear; and “authoritarians,” who gravitate toward strong hierarchical leadership. By contrast, colluders actively support bad leaders for personal gain or ideological alignment. Lipman-Blumen (2006) distinguishes between the leader's entourage, who share the leader's toxic values, and malevolent followers, who are driven by envy or opportunism. Thoroughgood et al. (2012) identify “acolytes,” who are value-aligned with the leader, and “opportunists,” who seek personal benefit regardless of ideology. Kellerman (2024) broadens this spectrum under the label “enablers,” encompassing both active complicity and passive tolerance.

Two main types of followers differ not only in behavior and motivation but also in the explanatory logics they embody. While collusion implies ideological or strategic alignment, conformity is often rooted in psychological need or situational fear. Yet both categories reflect deeper normative assumptions. Two persistent myths, usually traced back to interpretations of Hitler's Germany, continue to shape academic and public discourse on followership, reinforcing simplistic dichotomies between autonomy and obedience, morality and conformity.

4 Second myth: followers of bad leaders are natural conformists

Academic and public discourse often interpret the emergence of evil as an innate human tendency, a perspective largely shaped by a simplified reading of Arendt's (1994) “banality of evil” thesis (Birney et al., 2024, p. 94–95). In her analysis of Adolf Eichmann, a central figure in orchestrating the Holocaust, Arendt challenged the notion that such individuals are necessarily monstrous or psychopathic. Instead, she portrayed Eichmann as a disturbingly ordinary bureaucrat, focused on efficiency and personal advancement, detached from the moral consequences of his actions. This interpretation has been amplified by canonical social psychology experiments, notably Milgram's (1974) obedience studies and Zimbardo's (2007). Stanford Prison Experiment, which have long served as empirical cornerstones for the claim that people tend to obey authority blindly and uncritically. Such findings have sustained the view that conformity and obedience are default human responses under hierarchical pressure.

However, this narrative has been increasingly contested. Scholars like Haslam and Reicher have demonstrated that followers often do not simply submit to authority out of passivity or fear. Rather, obedience is more accurately understood as a process of active identification with leaders, with norms, or with collective goals. Their work invites leadership scholars to reconsider the dominant myth of passive followership and to explore the more complex psychological and relational mechanisms through which individuals come to support destructive authority.

The seminal work of Milgram (1974) fundamentally shaped public and academic understandings of obedience to authority. In his iconic experiments, participants were instructed to administer electric shocks to a “learner” at increasing voltages. Although outcomes varied across iterations, the initial finding that all participants proceeded to at least 300 volts, and 65% reached the maximum of 450 volts, quickly became emblematic of the human tendency toward blind obedience. Milgram (1974, p. 6) famously interpreted these results through Arendt's “banality of evil” lens, arguing that participants acted not out of aggression but a sense of duty. In his view, they entered an “agential state” (Milgram, 1974, p. 132–134), suspending moral judgment to carry out the directives of a legitimate authority figure.

However, later reinterpretations have significantly challenged this conclusion. Haslam and colleagues argue that Milgram's participants did not simply yield to coercion but engaged in engaged followership, aligning with the experimenter's scientific mission. Engaged followership describes a dynamic in which followers actively participate in and morally justify collective behavior by aligning themselves with the leader's identity, goals, and normative vision (Haslam et al., 2020). Four key findings support this view (Haslam et al., 2015; Birney et al., 2024). First, Milgram's framing of the study as a contribution to science fostered participant commitment. Second, many participants stopped between 150 and 315 volts, moments when the learner's distress created an alternative target for identification (Packer, 2008). Third, participants were more likely to resist direct orders (“You have no other choice, you must go on”) than appeals to scientific purpose (“The experiment requires that you continue”) (Burger, 2009; Burger et al., 2011; Haslam et al., 2014). Fourth, willingness to administer maximum shocks correlated with identification with the scientific goals of the experimenter rather than detachment or lack of moral concern (Reicher et al., 2014). These findings undermine the notion that obedience is a universal and passive human reflex. Instead, they suggest that compliance is shaped by social identity, perceived legitimacy, and the framing of authority—challenging the foundational myth of blind conformity that has long informed both leadership studies and popular narratives about evil.

In his seminal Stanford Prison Experiment, Zimbardo (2007) assigned 24 undergraduate volunteers to the roles of guards or prisoners in a simulated prison environment. Unlike Milgram's study on obedience to external authority, Zimbardo sought to demonstrate how individuals internalize and enact roles even in the absence of explicit coercion. The results were dramatic and remain influential despite sustained ethical and methodological criticism. The guards' behavior became increasingly abusive, leading to the early termination of the experiment after just 6 days. Zimbardo interpreted this escalation as evidence that situational factors and assigned roles can override personal morality, pushing ordinary people to enact cruelty without critical reflection. This transformation, which he termed the Lucifer Effect, evokes the metamorphosis of Dr. Jekyll into Mr. Hyde in Stevenson's novella, an analogy that powerfully captured public imagination.

Zimbardo's interpretation has been widely disseminated and reinforced through multiple popular and academic channels, including his TED Talk (Zimbardo, 2008), bestselling book The Lucifer Effect (2007), and several dramatizations (Musen, 1992; Das Experiment, 2001; The Experiment, 2010; The Stanford Prison Experiment, 2015). As a result, his conclusions continue to shape dominant narratives about human nature and power, often cited as proof that tyranny lies dormant within us all, waiting for the right situation to emerge.

However, subsequent analyses have challenged the notion that the guards' behavior emerged spontaneously. Archival materials and documentary footage (Musen, 1992) reveal that Zimbardo and his team actively shaped the experiment's outcomes through direct instruction and identity leadership. During orientation, guards were urged to create fear, enforce arbitrariness, and deindividuate prisoners—guidance that framed the study as an “us versus them” conflict (Haslam et al., 2019). In this light, Zimbardo acted less as an impartial observer and more as a leader influencing participant identity and conduct. According to Haslam et al. (2020), identity leadership refers to a process through which leaders cultivate, represent, and advance a shared social identity to mobilize followers and legitimize collective action—a dynamic clearly at play in the constructed intergroup antagonism of the Stanford Prison Experiment.

Further evidence supports this reinterpretation. A 5-h pre-briefing scripted guard behavior in detail, and post-study interviews revealed ongoing encouragement to maintain harsh conditions. Participants later recalled that cruelty was not merely tolerated but expected to ensure the experiment's credibility (Haslam et al., 2019; Le Texier, 2019; cf. Zimbardo and Haney, 2020). These insights challenge the original narrative, underscoring the central role of leadership in activating destructive group dynamics, contrary to the experiment's portrayal as a natural unfolding of situational pathology.

Building on these critiques, Haslam and Reicher's (2006, 2007) BBC Prison Study offered a more rigorously controlled alternative. Unlike Zimbardo, they refrained from direct intervention and allowed group dynamics to evolve naturally. Early permeability between prisoner and guard roles encouraged individual ambition, but when advancement was blocked, collective resistance emerged. The arrival of a new prisoner, a trade union leader, further destabilized guard control and led to a brief period of egalitarian rule. However, this system faltered, and some participants began to favor authoritarian alternatives. Psychometric data revealed a rise in authoritarianism, particularly among individuals frustrated with the inefficiency of democracy. Rather than viewing tyranny as a byproduct of role conformity, Haslam and Reicher emphasize the role of group identity, leadership, and the failure of collective cohesion. Their findings suggest that oppressive systems do not emerge from inherent obedience but from the collapse of shared identity and the search for order amid uncertainty. In this view, the emergence of authoritarianism reflects not human nature per se, but the social dynamics of failed democratic cooperation.

Taken together, these reinterpretations of Milgram's and Zimbardo's classic studies—alongside more recent analyses such as Haslam et al. (2022) identity-based account of the Capitol assault—offer a powerful corrective to the myth of passive, conformity-driven followership. Rather than defaulting to obedience or cruelty, individuals appear to act in ways that reflect their identification with group norms, leadership goals, and perceived moral justifications. Authority alone does not guarantee compliance; followers must recognize and internalize the leader's mission as their own. This underscores the role of identity leadership, where leaders cultivate a shared sense of “us” to foster engaged followership—a process that can render even violent or anti-democratic actions morally intelligible and collectively meaningful. This insight fundamentally shifts the analytical lens from static personality structures or situational determinism to relational and identity-based processes. It invites leadership scholars and political scientists to move beyond reductive models of human behavior and toward a more nuanced understanding of how destructive authority is legitimized, enacted, and resisted within group contexts. If tyranny is not a latent instinct but a product of failed collective meaning-making, then the resilience of democratic norms hinges not on suppressing power but on sustaining shared identity, moral clarity, and critical leadership accountability. At the same time, recognizing active identification as a key mechanism in obedience must not serve to shift blame away from those in power. Rather, it highlights how leadership manipulates moral alignment and identity cues to recruit complicity—an insight that sharpens, rather than blurs, moral accountability.

5 The third myth: followers as mere colluders sharing leaders' negative traits

It is often assumed that followers of bad leaders resemble them in kind, sharing the same undesirable traits that ostensibly bind them into a political alliance. This assumption reflects a broader belief that leaders represent their groups, leading observers to project individual traits onto the collective. Haslam and Reicher (2016) caution against this heuristic, noting that it flattens political judgment into stereotype: the familiar narrative of “fools led by knaves.”

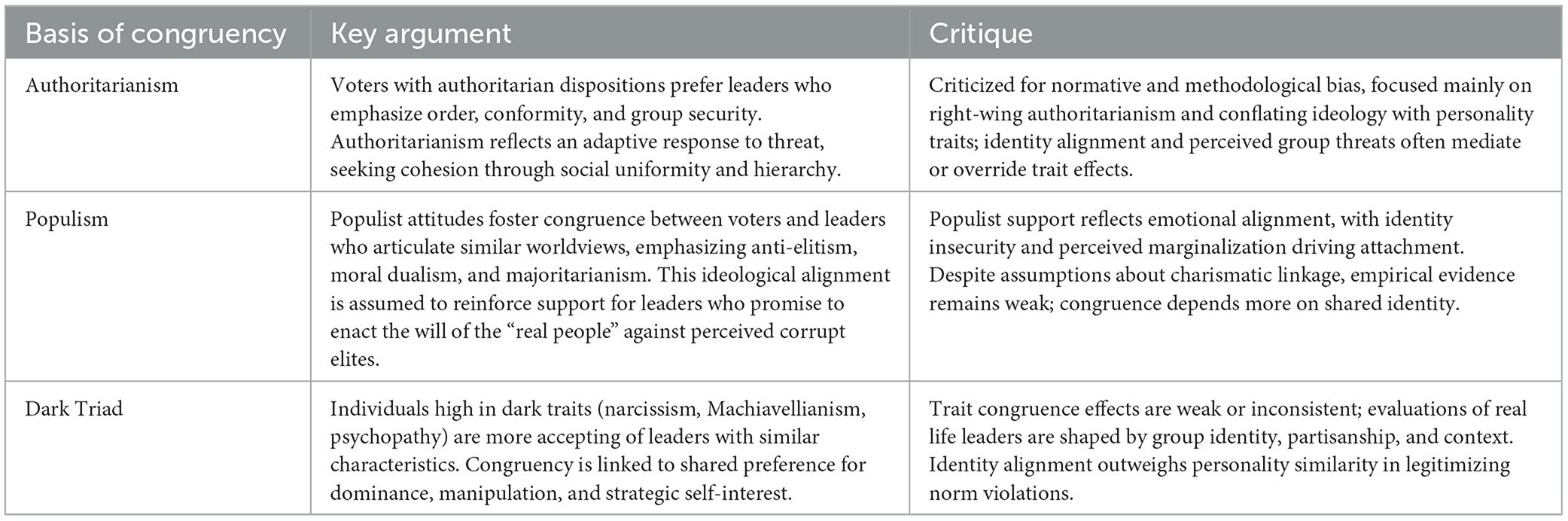

Political psychology has codified this intuition in the congruence model, which posits that individuals are more likely to support politicians whose personality traits mirror their own (Caprara and Zimbardo, 2004). This framework has shaped empirical inquiry across three domains often linked to bad leadership: authoritarian dispositions (Adorno et al., 1950; Duckitt, 2022), populist attitudes (Hawkins et al., 2012; Akkerman et al., 2014), and dark personality traits (Paulhus and Williams, 2002; Nai and Toros, 2020). Each line of research suggests that psychological similarity between leaders and followers may reinforce political alignment, particularly under conditions of uncertainty or threat.

Yet while the empirical findings regarding these associations are mixed, they risk overstating the determinism of personality and underestimating the situational, emotional, and identity-driven processes that mediate follower loyalty. Trait similarity alone does not fully explain how and why followers rationalize norm violations, especially in contexts where moral polarization and shared identity override personal misgivings. This study argues that bad leadership is less about psychological mirroring than the relational dynamics through which legitimacy is actively constructed.

5.1 Authoritarianism

The similarity-attraction thesis in harmful leadership draws heavily on psychological theories developed initially to explain the rise of fascism, particularly Nazi Germany. Early models of authoritarianism sought to understand how ordinary people became complicit in mass violence and dictatorship, focusing on personality traits that predisposed individuals to submission, conformity, and aggression toward out-groups. Fromm (1941) described the authoritarian personality as driven by a paradoxical mix of domination and submission rooted in psychological insecurity. Though speculative, his work laid the foundation for Adorno et al.'s (1950) influential study, which aimed to identify psychological predispositions that made citizens vulnerable to fascist propaganda and authoritarian leaders. Adorno's nine authoritarian traits, including conventionalism, submission to authority, and aggression toward deviance, were operationalized through the F-scale (e.g., “People can be divided into two distinct classes, the weak and the strong”). These traits were theorized as defense mechanisms developed through harsh upbringings and socio-economic anxiety, making individuals susceptible to leaders who redirected frustration toward scapegoats. The implicit goal was to explain how “good Germans” could support, or at least tolerate, a genocidal regime.

Later research refined these early models. Altemeyer (1981, 1996) reconceptualized authoritarianism as a learned attitude rather than a fixed personality structure and introduced the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) scale based on three traits: conventionalism, authoritarian submission, and authoritarian aggression. In contrast to Adorno's psychoanalytic orientation, Altemeyer argued that authoritarian tendencies are shaped by social learning and life experiences, particularly during adolescence. Complementing this, Pratto et al. (1994) introduced Social Dominance Orientation (SDO), a measure of preference for group-based hierarchies. While RWA and SDO operate independently, they both predict support for authoritarian leaders, prejudice, and social intolerance (Altemeyer, 1998).

Modern approaches move further away from trait-based explanations and emphasize the social-psychological functions of authoritarian attitudes. Duckitt's (2001) Dual Process Model (DPM) and Kreindler's (2005) Dual Group Processes Model link RWA to a desire for security and group cohesion under threat, while SDO reflects a motivation to maintain group dominance. This reconceptualization foregrounds the dynamic interaction between group identity, ideological beliefs, and contextual threats in shaping authoritarian tendencies (see also Duckitt, 1989; Feldman, 2003). As Engelhardt et al. (2023, p. 540) put it succinctly, “Authoritarianism is a personality adaptation that prioritizes social cohesion and conformity to in-group norms over personal freedom and individual autonomy.”

Despite these theoretical advancements, research on authoritarianism continues to face criticism for normative bias, particularly its exclusive focus on right-wing variants while neglecting left-wing authoritarianism (Duckitt, 2022, p. 180–181). Moreover, the ideological framing of constructs such as RWA raises methodological concerns: when measures are saturated with political content, it becomes challenging to distinguish authoritarianism from mere ideological preference. This conflation limits the explanatory power of authoritarianism research and reduces complex identity-driven dynamics to static ideological congruence.

Although authoritarianism is often viewed as a central threat to democracy, its link to regime preferences is more complex than commonly assumed (Erhardt, 2023). While authoritarian attitudes are frequently associated with support for strong leaders who sidestep constitutional constraints, U.S.-based studies show that dissatisfaction with democracy does not straightforwardly translate into support for strongman rule (Drutman et al., 2018). Instead, many citizens reconcile their desire for forceful leadership with a general attachment to democracy, albeit one that favors majoritarianism over liberal institutionalism. Malka and Costello (2023) similarly find little explicit rejection of democracy among Americans, but widespread support for authoritarian practices when perceived as beneficial, along with a readiness to undermine elections through violence. Identity dynamics best explain these patterns. Research across countries and contexts (Kingzette et al., 2021; Fossati et al., 2022; Simonovits et al., 2022; Braley et al., 2023; Bryan, 2023; Krishnarajan, 2023; Littvay et al., 2024) shows that citizens are more accepting of illiberal actions when their preferred party or leader is in power. This asymmetry, what Simonovits et al. (2022) call “democratic hypocrisy,” reflects selective enforcement of norms: people expect rivals to obey the rules while excusing violations from their own side.

Partisan identity thus often overrides democratic principles. Graham and Svolik (2020) demonstrate that many voters prioritize partisan interests over core norms like fair elections or checks and balances. Krishnarajan's (2023) 23-country study further shows that people adjust their definition of democracy to align with their values, perceiving supportive policies as democratic, even if illiberal, and opposing ones as undemocratic, even when procedurally sound. Two main insights emerge. First, perceptions of democracy are shaped more by identity-based evaluations than by institutional knowledge. Second, democratic norms have become politicized, with their application contingent on group alignment. Kingzette et al. (2021) attribute this to affective polarization: governing parties erode constraints while opposition parties defend them, and citizens follow suit, applying democratic standards selectively. Braley et al. (2023) offer a partial remedy, showing that when voters perceive opponents as more norm-abiding than expected, their own tolerance for anti-democratic behavior decreases. Still, the evidence is clear: institutional resilience depends not just on formal design, but on whether citizens, as followers, uphold norms consistently, especially when their side is in power.

5.2 Populism

In political science, increasing attention is paid to how citizens' populist attitudes, such as anti-elitism, people-centrism, and Manicheanism, create fertile ground for harmful leadership. As a recent review notes, populist voters often feel alienated from representative institutions and perceive established parties as unresponsive to their needs. This disillusionment, intensified by economic and cultural crises, fuels anxiety, anger, and conspiracy thinking (Marcos-Marne et al., 2023). While empirical results vary, most studies consistently find an association between populist attitudes and support for populist parties.

Populism is deeply intertwined with identity politics (Aslanidis, 2020; Uysal et al., 2022). Empirical studies suggest that individuals from disadvantaged groups, those who struggle to establish a positive social identity, are particularly susceptible to populist worldviews (Spruyt et al., 2016). Identity insecurity has been shown to increase both openness to populism (Hogg and Gøtzsche-Astrup, 2021) and preference for strong, directive leaders (Hogg, 2021). These findings highlight the central role of identity dynamics in shaping support for populist leadership: populism appeals not only as a critique of elite politics but also as a vehicle for symbolic belonging and moral affirmation.

Within this framework, the quasi-direct, emotionally charged relationship between leaders and followers becomes pivotal. While populism is frequently associated with charismatic leadership, empirical evidence remains mixed (van der Brug and Mughan, 2007; Michel et al., 2020). Recent studies show that populist supporters may idealize their leaders, yet do not necessarily perceive them as more charismatic than mainstream politicians (Metz and Plesz, 2023, 2025). What they do share, however, is a preference for political styles that promise a more immediate and morally framed expression of popular sovereignty. Populist citizens tend to be critical of representative institutions but are not uniformly hostile to democratic principles. Instead, they often advocate for a majoritarian and plebiscitary model of democracy that emphasizes direct, unmediated expressions of the people's will (Bos et al., 2023; Marcos-Marne et al., 2023; Zaslove and Meijers, 2024). While this does not necessarily amount to a rejection of democracy, it frequently entails the erosion of liberal norms, particularly when identity alignment and emotional investment in leaders override commitments to pluralism and institutional checks.

5.3 Dark Triad

Political scientists have increasingly explored the intersection of voters' populist attitudes and dark personality traits, particularly in relation to leaders who exhibit such characteristics. While research suggests that populist voters tend to be more tolerant of politicians with dark traits (Nai, 2022), and that individuals high in these traits are more likely to support populist candidates (Bakker et al., 2016), the relationship remains inconsistent. A Canadian study found a negative association between narcissism and populist sentiment (Pruysers, 2021), whereas a Spanish study reported that psychopathy and Machiavellianism negatively predicted populist worldviews, with narcissism positively linked to the people-centric dimension of populism (Galais and Rico, 2021). Other findings suggest that narcissism predicts support for Trump only indirectly, through ideological mediators such as RWA and SDO (Hart and Stekler, 2022). However, broader evidence on the ideological alignment of dark traits remains mixed (Hart et al., 2018). A recent comparative study adds further nuance: while psychopathy showed the strongest positive association with populist attitudes, Machiavellianism followed, and narcissism had no effect, underscoring the cultural and contextual variability of the populism–dark personality link (Hofstetter and Filsinger, 2024).

Analyses of trait congruence show that, in general, voters disfavor candidates perceived as having dark traits. Yet voters who score high on these traits themselves tend to be more accepting, especially among those with weak partisan ties (Hart et al., 2018; Nai et al., 2021). Still, confirming these congruence effects in real-world politics remains challenging due to the interpretive influence of ideological and identity-based biases (Wright and Tomlinson, 2018; cf. Nai and Maier, 2021a). Experimental research on fictional leaders, where identity effects are absent, further complicates this mapping. Overall, these findings cast doubt on the similarity thesis at the individual level. However, perceived similarity matters in another way: a recent German study found that voters, especially those with authoritarian or populist leanings, are more likely to tolerate illiberal practices when their policy preferences are represented, even if doing so compromises liberal democratic norms (Lewandowsky and Jankowski, 2023).

These results point to an important qualification: while individual-level traits such as authoritarianism, populist attitudes, or dark personality characteristics may shape responses to norm violations, their influence is neither universal nor stable across contexts. Rather, these dispositions tend to matter most within the framework of a shared identity or in light of strong ideological alignment. For example, social identity influences attitudes toward political violence: strong partisan allegiance can increase the likelihood of justifying violent actions—but primarily among individuals exhibiting dark traits (Gøtzsche-Astrup, 2021). This suggests that ideological commitment and group belonging moderate the relationship between personality traits and political behavior, reinforcing the idea that followership cannot be reduced to individual psychology alone. Instead, understanding tolerance for bad leadership requires integrating personal dispositions with the emotional, moral, and identity-based mechanisms through which legitimacy is collectively co-produced.

Taken together, these findings challenge the deterministic assumption that bad leaders are merely reflections of their followers' psychological dispositions (Table 2). While there is evidence of attitudinal and personality-based congruence, especially under conditions of identity threat, emotional polarization, and weakened institutional trust, such alignment is neither uniform nor sufficient to explain norm violations. Authoritarianism, populist attitudes, and dark personality traits interact with broader social, political, and contextual forces, shaping how followers perceive and respond to leadership. Rather than attributing bad followership to individual pathology, this chapter underscores the importance of identity alignment, perceived representational congruence, and affective partisanship as mechanisms through which citizens legitimize harmful leadership. In this view, followers are not passive mirrors of deviance but active co-producers of political legitimacy, capable of sustaining or contesting democratic backsliding depending on how leaders' actions resonate with their moral frameworks and group identities. The third myth, that followers are mere colluders sharing their leaders' worst qualities, fails to capture the complexity and contingency of political allegiance in democratic decline.

6 Discussion

This article has argued that dominant approaches to the study of bad leadership are shaped by three influential myths that distort our understanding of how harmful authority emerges and endures (Table 3). First, much of the literature continues to treat bad leadership as the product of deviant personal traits or destructive behavioral styles, attributing failure primarily to individual pathology. Second, followers are often portrayed as passive conformists who simply submit to authority, reinforcing a simplistic view of obedience as reflexive and universal. Third, it is frequently assumed that followers of bad leaders share the same negative traits, such as authoritarianism or populist attitudes, which explains their political alignment through psychological resemblance.

Each of these assumptions has come under increasing empirical and theoretical scrutiny. Leadership outcomes are not determined solely by leaders but are co-produced through dynamic interactions with followers in environments that permit or encourage norm violations. Followers, in turn, do not merely comply out of blind submission, but actively engage in meaning-making processes rooted in group identification and moral justification. And rather than being drawn to leaders because of shared traits, many followers align with harmful leadership through emotional and identity-based attachment, even in the absence of deep psychological similarity.

However, the three myths are not just theoretically flawed; they have tangible consequences. By obscuring the relational, structural, and identity-based mechanisms that enable destructive leadership, they risk promoting simplistic explanations and ineffective responses. In both organizational and political arenas, such misunderstandings can weaken accountability, normalize deviance, and facilitate the rise of authoritarian figures who cloak themselves in legitimacy. Importantly, recognizing followers' active role in sustaining harmful leadership does not mean diffusing responsibility away from leaders. On the contrary, it reveals how power operates through the strategic cultivation of moral alignment and group identification—tools that deepen, rather than diminish, the ethical burden of those who lead. This perspective advocates for a more refined model of accountability: one that does not reduce harm to individual pathology but instead understands leadership as a dynamic interplay of agency and context, persuasion and reception.

Crucially, harmful leadership should not be seen as an aberration that lies outside the normal bounds of social influence. On the contrary, it is not the opposite of “good” leadership, but often its mirror image—driven by the very same psychological and relational mechanisms that sustain socially desirable leadership. What distinguishes the two is not the processes themselves, but the engaged followership, identity leadership, and moral consequences of the collective projects they enable. Far from being wholly deviant, destructive leadership emerges from familiar dynamics of identity construction, follower engagement, and contextual permissiveness. In short, this paper does not dismiss the importance of understanding bad leadership but offers a perspective freed from the distorting influence of popular myths.

The cited empirical research suggests that future studies should investigate what most influences whether individuals tolerate norm violations or harmful behavior in their leaders. Emerging findings underscore the central role of shared identity in mediating these judgments, highlighting a crucial direction for future inquiry.

Group identity is central to shaping moral judgment and tolerance for bad leadership. Leaders perceived as prototypical group representatives often receive moral leniency when violating norms, as followers prioritize cohesion over ethical consistency. This “transgression credit” (Abrams et al., 2018; Davies et al., 2024) enables in-group leaders to evade scrutiny that would otherwise apply to out-group figures. Research highlights that perceived leader morality reinforces alignment with group values, strengthening legitimacy and cohesion (Giannella et al., 2022). Tolerance also depends on whether norm violations are seen as benefiting the in-group or harming the out-group. Voters consistently judge in-group leaders' unethical behavior more leniently than that of out-group leaders (Redlawsk and Walter, 2024). Electoral victories reinforce leaders' prototypicality, encouraging followers to excuse violations as necessary responses to external pressures (Gaffney et al., 2019; Morais et al., 2020; Syfers et al., 2022). Motivated reasoning can shield partisans from recognizing wrongdoing, but when disillusionment sets in, it often leads to abrupt withdrawal of support (von Sikorski et al., 2020).

Despite these insights, several research gaps remain. Future studies should explore how individual-level factors, such as dark personality traits, populist attitudes, and authoritarian tendencies, interact with identity to shape tolerance for norm violations. Additionally, the impact of psychological, power, and physical distance on the moral judgment of political vs. organizational leaders remains an open question. The differential tolerance for corruption, incompetence, or ethical misconduct also deserves further inquiry. Finally, institutional contexts and political polarization must be better integrated into models explaining when and why citizens accept or resist destructive leadership.

Although followership receives less scholarly attention than leadership, it is often framed by two persistent myths. First, followers are assumed to be naturally submissive and conformist, an assumption long associated with Milgram's and Zimbardo's studies but now challenged by more recent evidence emphasizing shared identity and group dynamics as key motivators. Second, followers are often assumed to resemble their leaders, drawn to them through shared authoritarian, populist, or dark traits. However, these traits alone rarely explain leader support. Instead, shared identity, particularly when coupled with moral and affective polarization, offers a more compelling explanation for why followers overlook harmful behaviors or justify norm violations. While individual personality traits and political attitudes—such as authoritarianism or populist orientations—may contribute to these dynamics, their influence becomes salient primarily within the framework of a shared identity or in light of group identification. Understanding followership thus requires attention not only to personality or ideology, but to the emotional, moral, and identity-based mechanisms through which legitimacy is co-produced.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

RM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Ministry for Innovation and Technology under the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Fund (grant number FK 146569). RM is a recipient of the Bolyai János Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (grant number BO/00077/22). The research was conducted within the framework of the project MORES—Moral Emotions in Politics: How They Unite, How They Divide, which has received funding from the European Union under Grant Agreement No. 101132601. Views and opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT and Deepl in the writing process to improve language and readability of the manuscript. After using these tools, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abrams, D., Travaglino, G. A., Marques, J. M., Pinto, I., and Levine, J. M. (2018). Deviance credit: tolerance of deviant ingroup leaders is mediated by their accrual of prototypicality and conferral of their right to be supported. J. Soc. Iss. 74, 36–55. doi: 10.1111/josi.12255

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., and Sanford, N. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality, 1st Edn. New York, N.Y.: Harper & Brothers.

Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., and Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comp. Polit. Stud. 47, 1324–1353. doi: 10.1177/0010414013512600

Altemeyer, B. (1998). “The other ‘authoritarian personality,”' in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, ed. M. P. Zanna (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 47–92.

Arendt, H. (1994). Eichmann In Jerusalem: A Report On The Banality Of Evil. New York, NY: Penguin Classics.

Ashforth, B. (1994). Petty tyranny in organizations. Hum. Relat. 47, 755–778. doi: 10.1177/001872679404700701

Aslanidis, P. (2020). “The social psychology of populism,” in Mapping Populism, eds. A. Ron, and M. Nadesan (New York, NY: Routledge), 166–175.

Bakker, B. N., Rooduijn, M., and Schumacher, G. (2016). The psychological roots of populist voting: evidence from the United States, the Netherlands and Germany. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 55, 302–320. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12121

Barling, J., Christie, A., and Turner, N. (2008). Pseudo-transformational leadership: towards the development and test of a model. J. Bus. Ethics 81, 851–861. doi: 10.1007/s10551-007-9552-8

Bartels, L. M. (2023). Democracy Erodes from the Top: Leaders, Citizens, and the Challenge of Populism in Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bass, B. M., and Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. Leadersh. Q. 10, 181–217. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00016-8

Birney, M. E., Reicher, S. D., and Haslam, S. A. (2024). Obedience as “engaged followership”: a review and research agenda. Philos. Sci. 28, 91–105. doi: 10.4000/11ptx

Blais, J., and Pruysers, S. (2017). The power of the dark side: personality, the dark triad, and political ambition. Pers. Individ. Dif. 113, 167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.03.029

Bligh, M. C., Kohles, J. C., Pearce, C. L., Justin, J. E., and Stovall, J. F. (2007). When the romance is over: follower perspectives of aversive leadership. Appl. Psychol. 56, 528–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00303.x

Bogaards, M. (2009). How to classify hybrid regimes? Defective democracy and electoral authoritarianism. Democratization 16, 399–423. doi: 10.1080/13510340902777800

Bos, L., Wichgers, L., and van Spanje, J. (2023). Are populists politically intolerant? Citizens' populist attitudes and tolerance of various political antagonists. Polit. Stud. 71, 851–868. doi: 10.1177/00323217211049299

Bostock, W. W. (2010). “Evil, toxic and pathological categories of leadership: implications for political power,” in Challenging Evil: Time, Society and Changing Concepts of the Meaning of Evil, eds. J. Schlegel, and B. Hansen (Leiden; Boston, MA: Brill), 11–16.

Braley, A., Lenz, G. S., Adjodah, D., Rahnama, H., and Pentland, A. (2023). Why voters who value democracy participate in democratic backsliding. Nat Hum Behav. 7, 1282–93. doi: 10.1038/s41562-023-01594-w

Brancati, D. (2014). Democratic authoritarianism: origins and effects. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 17, 313–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-052013-115248

Bryan, J. D. (2023). What kind of democracy do we all support? How partisan interest impacts a citizen's conceptualization of democracy. Comp. Polit. Stud. 56, 1597–1627. doi: 10.1177/00104140231152784

Burger, J. M. (2009). Replicating Milgram: would people still obey today? Am. Psychol. 64, 1–11. doi: 10.1037/a0010932

Burger, J. M., Girgis, Z. M., and Manning, C. C. (2011). In their own words: explaining obedience to authority through an examination of participants' comments. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2, 460–466. doi: 10.1177/1948550610397632

Burns, J. M. (2003). Transforming Leadership: A New Pursuit of Happiness. New York, NY: Grove Press.

Camgoz, S. M., and Karapinar, P. B. (2021). “Measuring destructive leadership,” in Destructive Leadership and Management Hypocrisy, eds. S. M. Camgöz, and Ö. T. Ekmekci (Bradford: Emerald Publishing Limited), 181–195.

Caprara, G. V., and Zimbardo, P. (2004). Personalizing politics: a congruency model of political preference. Am. Psychol. 59, 581–594. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.581

Chen, P., Pruysers, S., and Blais, J. (2021). The dark side of politics: participation and the dark triad. Polit. Stud. 69, 577–601. doi: 10.1177/0032321720911566

Collinson, D., Smolović Jones, O., and Grint, K. (2018). ‘No more heroes': critical perspectives on leadership romanticism. Org. Stud. 39, 1625–1647. doi: 10.1177/0170840617727784

Conger, J. A. (1990). The dark side of leadership. Organ. Dyn. 19, 44–55. doi: 10.1016/0090-2616(90)90070-6

Conger, J. A., and Kanungo, R. N. (1998). Charismatic Leadership in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Davies, B., Abrams, D., and Leicht, C. (2024). Why leaders can be bad: linking rigor with relevance using machine learning analysis to test the transgression credit theory of leadership. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 27, 1068–1087. doi: 10.1177/13684302241242095