- Department of Politics, Languages and International Studies, University of Bath, Bath, United Kingdom

Amid China's rise and intensifying China–U.S. competition in the Indo–Pacific region, it is widely consented among international scholars that a key strategy in Southeast Asia's statecraft and geopolitics is the adoption of “hedging” against great powers, to maximize economic gains and mitigate security risks. For more than two decades, academic, strategic, and policy studies of Southeast Asia's hedging strategies have contributed a wealth of diverse scholarship, which increasingly influences the academic, strategic, and policy debates among emerging powers and small- and medium-sized littoral states in the Indo–Pacific region. This article reviews the literature and identifies key theoretical developments and research gaps. In response to the recognized conceptual–methodological gap in effectively addressing, capturing, and mitigating the structural uncertainties and security risks arising from great power rivalry, this article outlines a futurist approach to anticipatory methodology. Using a Taiwan contingency for scenario planning in which the U.S. and China engage in armed conflict over Taiwan, it imagines possible, plausible, probable, and preferable scenarios, corresponding policy options, and identifies the limits and strategic scenarios that South Korea, the Philippines, and Vietnam would likely consider and encounter. This article concludes that to preserve a suitable external security environment for hedging to maximize economic gains and minimize security risks, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) will need to work closely not only with ASEAN member-states but also with partners to anticipate different future scenarios and proactively prevent the worst-case scenario of a Taiwan contingency from occurring. A novel conceptual contribution of “anticipatory hedging” is therefore made to advance the theoretical development of hedging.

1 Introduction

Southeast Asian countries are increasingly concerned about the intensifying great power rivalry, competition, and decoupling between the United States (U.S.) and China, which have caused spillover effects in the region. For the past 20 years, scholars have agreed that East and Southeast Asian countries have been adopting the “hedging” strategy. However, recent analyses express concerns that this long-held “hedging” strategy by Southeast Asia may soon be either abandoned or rendered ineffective if a major U.S.–China armed conflict emerges across the Taiwan Strait (Marston and Bruce, 2020; Ngeow, 2024).

Since the Taiwan Strait is geopolitically connected to the South China Sea, where Beijing, Taipei, the Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia, and Indonesia have overlapping territorial claims and sovereignty disputes, many Southeast Asian countries are concerned that the Taiwan contingency will likely trigger wider armed conflicts and crises across the South China Sea and Southeast Asia. The entire region could then be drawn into a U.S.–China conflict. Southeast Asia's long-practiced “hedging” strategy would be rendered ineffective or obsolete, forcing Southeast Asian countries to take sides with either the U.S. or China. The Taiwan contingency would significantly undermine the cohesion and functions of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), divide the ASEAN region, and bring unprecedented crises, disruptions, and chaos to the countries in the Indo–Pacific region.

In response to these strategic and policy concerns, this article will first review the theoretical development of the “hedging” strategy among Southeast Asian countries in the English-speaking scientific literature. It will identify research gaps and envision a suitable methodological approach for Southeast Asian policymakers to better practice hedging amid increasing structural uncertainties resulting from intensifying U.S.–China rivalry and decoupling.

2 Literature review and knowledge gaps

2.1 Key theoretical developments of “hedging”

Apart from Southeast Asian scholars, various scholars from Japan, the U.S., mainland China, Taiwan, Australia, and Europe have also reached a consensus: in response to China's economic rise and U.S.–China competition, ASEAN countries have adopted “hedging” policies (Anwar, 2023, p. 360–361; Askari and Tahir, 2021; Boyd et al., 2023; Feng and Netkhunakorn, 2024; Gerstl, 2022, 2024; Kuok, 2024; Lim and Cooper, 2015; Matsuda, 2012; Roy, 2005; Tan, 2020). As a proactive strategy, Southeast Asian small states commonly wish to achieve two contradictory main goals through “hedging” with the U.S. and China. On one hand, ASEAN countries wish to develop their national economies by deepening economic and trade relations with China. On the other hand, to mitigate the risks of conflict and over-dependence on China, ASEAN countries seek to maintain security cooperation and economic-trade relations with America.

Although China's rise brought positive economic development opportunities to ASEAN, regional flashpoints such as the South China Sea necessitate that smaller and middle-sized Southeast Asian states seek an “insurance policy”. In other words, if conflict emerges between ASEAN and China in the South China Sea, the “fall back option” would be Southeast Asia's security cooperation with America. Hedging against the U.S. and China would mean achieving “returns-maximization” and fully preparing for “risk-contingency” as two policy goals (Anwar, 2023, p. 360–361, Askari and Tahir, 2021; Boyd et al., 2023; Feng and Netkhunakorn, 2024; Gerstl, 2022, 2024; Kuok, 2024; Lim and Cooper, 2015; Matsuda, 2012; Roy, 2005; Tan, 2020). Three main theoretical developments of hedging are identified in the literature: (1) neorealism, (2) neoclassical realism, and (3) norms competition.

2.1.1 Neorealism

In the first place, influenced by relevant debates surrounding defensive neorealism in American international relations theory (Schweller, 1994; Walt, 1985; Waltz, 1979), Malaysian scholar Kuik (2008, p. 150; 2016a) suggested that the analytical dualism constituted by the “balancing” school and the “bandwagoning” school in neorealism is unable to explain why and how Southeast Asian smaller states conduct their foreign and security policies in reaction to the structural uncertainties arising from the rise of China and the U.S.–China rivalry. On the one hand, the balancing school suggests that for smaller states to protect their own national security in the face of the potential threat of a rising neighboring power like China, they would devise two balancing policies to mitigate security risks: (1) internal balancing—strengthening national defense and military capability; (2) external balancing—forging alliances with the competitors of the rising neighboring power, i.e., the U.S. and European–Asian allies. On the other hand, the bandwagoning school suggests that when facing a rising China, the Southeast Asian smaller states would choose to bandwagon with it, i.e., exchange for profits to satisfy domestic interests by accepting a subordinate role under the rising Chinese power.

Kuik (2008, p. 160) suggests that even nowadays Southeast Asian countries choose to maintain military cooperation with the U.S. and Western powers; however, this does not mean that they intend to “balance” against a rising China. A main reason is that Southeast Asia's security relationships with Western powers historically predate the contemporary rise of China. Additionally, Southeast Asian military modernization programs were neither designed to counter China's rise nor accelerated by it.

In a similar vein, developing economic and trade relations with China does not necessarily imply that Southeast Asia agrees to “bandwagon” with a rising China. The smaller states of Southeast Asia seek to pragmatically cooperate with China, largely motivated by economic profits and diplomatic gains. They have not established a security alliance with China. Pure balancing and pure bandwagoning would significantly curtail the agency and autonomy of these smaller states, which would also increase strategic risks. Pure balancers would be accused by Beijing of collaborating with America to contain China's rise. Consequently, they would be denied access to the Chinese market and become tactical targets of the Chinese military. Similarly, a pure bandwagon would be criticized by the U.S. and its allies for joining the China camp, which would increase their risks of being politically isolated, financially sanctioned, and militarily targeted by the West, thereby causing them substantial economic, diplomatic, and political losses.

In view of these complex considerations, Southeast Asian countries commonly aim to maximize their economic and security gains from both the U.S. and China while minimizing the associated strategic risks and losses. The ruling elites in Southeast Asia, therefore, choose to adopt various “hedging” strategies that consist of different combinations of balancing and bandwagoning acts. Despite their strategic variations, Southeast Asian political elites commonly wish to achieve three “regime legitimation” objectives (Kuik, 2008, p. 161–162):

• To ensure their political survival by mitigating the security, economic, and political risks that could undermine their governance capacity.

• To clarify and address potential threats and risks early by recognizing that these security risks have evolved as a result of changing domestic and external factors.

• To protect national security and sovereignty while concurrently enhancing economic growth.

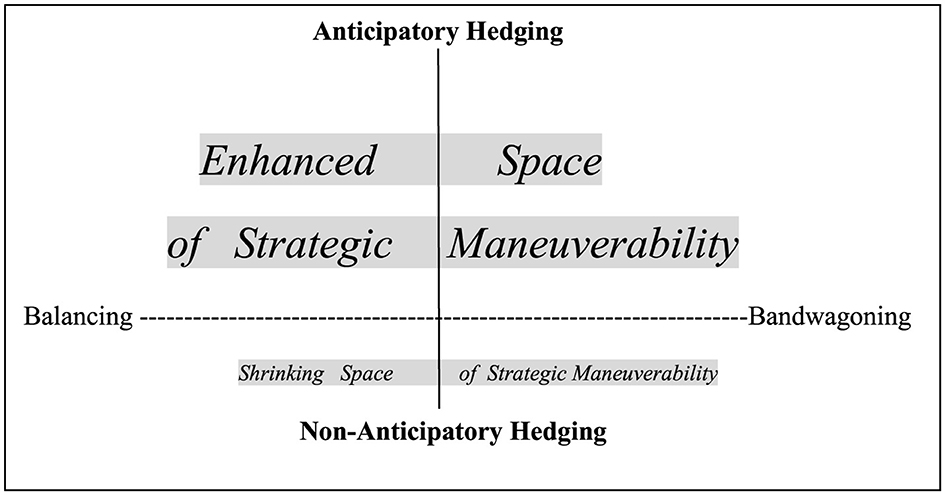

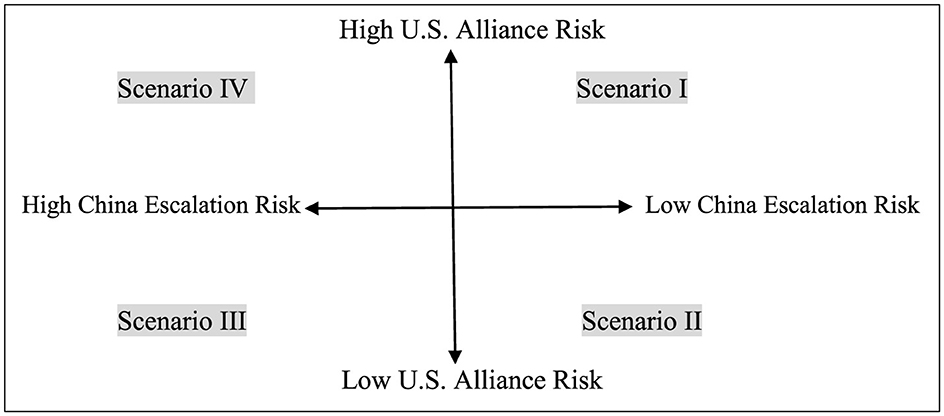

Conceptually, while balancing and bandwagoning constitute the two oppositional poles, hedging refers to the continuum-spectrum of a range of different policy options connecting the two poles (Figure 1). According to a scholarly consensus, there are at least five policy elements conceptualized in hedging: (1) economic pragmatism, (2) binding engagement, (3) limited bandwagoning, (4) domination denial, and (5) indirect balancing (Gerstl, 2022: Chapter 2, Kuik, 2008, p. 166–171, Liu, 2024, p. 34–36).

2.1.2 Neoclassical realism

Second, because hedging policies are primarily intended to serve the Southeast Asian ruling elites” “regime legitimation” agenda, a growing body of studies contributed by Australian, mainland Chinese, Taiwanese, Singaporean, Thai, and Vietnamese scholars suggests the usefulness and relevance of neoclassical realism. Using different Southeast Asian countries for comparative case studies, these scholarly studies have explained how various hedging behaviors toward the U.S. and China were motivated by the complex interplay between domestic politics and external factors (Fang and Li, 2022; Liu, 2023; Marston, 2024; Zha, 2022).

2.1.3 Norms competition

In the third theoretical development of hedging, scholars integrated neorealist and/or neoclassical realist conceptual features with elements of liberalism and constructivism. Through studies of international laws and institutions, these researchers established that various ASEAN countries utilized international laws and legal systems to protect their rights and advance claims in disputes with China in the South China Sea. Hedging also involves “norms competition” with China, in which Southeast Asian smaller powers bolster their own international legitimacy and the legality of their territorial claims, which also serves to bind and socialize China into regional norms favorable to the Southeast Asian smaller states (Chan and Charoenvattananukul, 2024; Nguyen, 2023; Tang, 2021). A notable example is the 2013–2016 South China Sea arbitration case filed and won by the Republic of the Philippines at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (The Hague, the Netherlands) against the People's Republic of China under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

2.2 Research gaps identified

2.2.1 Conceptual gap: distinguishing hedging from balancing/containment

The three theoretical developments in the literature have indeed enriched our understanding of Southeast Asian hedging strategies. Nonetheless, there are a few research gaps and important issues identified for further investigation.

First, although hedging consists of different extents of balancing and bandwagoning acts (Goh, 2006, 2007, 2016; Kuik, 2016a; Roy, 2005), it must be distinguished from balancing, which can also mean containment. Balancing China would naturally strengthen security cooperation or military alliances with America. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, Thailand, and Singapore have signed active security treaties and/or arrangements with America. These countries are integral constituents of the “East Asian first-island chain”, which the U.S. uses to geopolitically contain China. Goh (2006) therefore suggested that it is necessary to conceptually separate “hedging” from “balancing/containment”; although “hedging” can include balancing acts, it is not equivalent to “containment” (Goh, 2006).

This scholarly position has served to draw a clear theoretical and conceptual boundary demarcating hedging from “offshore balancing”, the latter being a key concept in offensive neorealism (Mearsheimer, 2001, p. 226). According to American offensive neorealist Mearsheimer, in order to defend global hegemony against the challenges posed by the rising regional hegemons of Nazi Germany, Soviet Russia, and Imperial Japan in Europe and Northeast Asia, the United Kingdom (U.K.) and the U.S. resorted to the strategy of “offshore balancing” before the Second World War (WWII). As offshore balancers, the U.K. and U.S. did not directly counter the military offensives of Nazi German troops, the Russian Red Army, and the Imperial Japanese armed forces. Instead, they adopted “buck-passing” strategies to “bait” the rising regional hegemons against the U.K.–U.S. allies in the European and Asian Rimlands for “blood-letting”, thereby containing the rising powers of Germany, Russia, and Japan (Mearsheimer, 2001, p. 153–155). By allowing and supporting their European and Asian allies/partners to weaken these rising regional hegemons, the balance of power in Europe and Northeast Asia was temporarily restored to conditions favorable for U.K.–U.S. global hegemony.

Southeast Asian policymakers should have already understood that the strategic success of hedging hinges on a subtle understanding of neutrality; being neutral means preventing the acts of balancing and bandwagoning from being used by offshore balancers to contain and weaken China. In other words, Southeast Asian strategists must ensure that the smaller ASEAN states are not baited into shouldering the burden of blood-letting and containing China. This is intended to prevent Southeast Asia from directly conflicting with China, which would bleed the regional economy and damage national security.

2.2.2 Empirical and policy gap: clarifying the Philippines's hedging strategy

In connection with the above discussion that distinguishes the notion of “balancing against China” from the position of “containing China”, the second research gap concerns the important debate about whether Philippine policy was actually hedging or balancing against China. Scholars have persistently argued that the Philippines actually balanced against China instead of practicing hedging (Kuik, 2016b, p. 169; Kuik, 2024). In contrast to this minority scholarly assessment, the majority of studies contributed not only by Filipino scholars but also by Malaysian, American, mainland Chinese, Taiwanese, and South Asian think tankers and scholars suggest otherwise. They argue that the contemporary Filipino ruling elites are mainly concerned about their own domestic political legitimacy and relatively precarious regime/leader security due to the Philippine military's strong historic ties with and hardware dependency on the U.S. military sector. This dependency has allowed the Philippine military to stage mini coups as threats, which can lead to renegotiation of policy decisions made by the Philippine civilian governments (De Castro, 2009, p. 116–117; Rodier, 2022, p. 112; Zha, 2022). As a result, the Philippines' hedging strategies tend to swing more drastically between the two poles of balancing and bandwagoning, making them less predictable than the hedging practices of other Southeast Asian countries.

In general, the scholarly consensus so far is that the Philippines has practiced a balancing-emphasized hedging strategy (mainly against China) and policies to protect its national security and develop its national economy (Askari and Tahir, 2021; Banlaoi, 2021; De Castro, 2009, 2021; Liou and Hsu, 2017; Liu, 2024; Rodier, 2022; Tang, 2021; Weerasena, 2024; Wong, 2018: Chapter 2, 25–50). As the Philippines is America's major treaty ally in Southeast Asia and has granted the U.S. access to its military bases, it has utilized international laws and U.S. security cooperation as instruments to protect its economic, energy, and sovereignty interests, while advancing legal claims in the South China Sea and maintaining economic and trade relations with China, its largest trading partner. In this context, this author argues that future research needs to address the hypothesis of “Philippine exceptionalism” in studies of Southeast Asian hedging strategies. In other words, have the Philippine ruling elites actually collaborated with the U.S. in “offshore balancing” to contain China, with the strategic intention of undermining China at the expense of their own national economic development and security?

2.2.3 Methodological gap: anticipating futures and scenario planning

Third, scholars have noted that hedging is only applicable in limited contexts and narrow circumstances. They caution that if the U.S. and China were to go to war or engage in armed conflict in the region, Southeast Asia would face maximum structural pressures, inevitably leading to the abandonment of hedging policies in favor of choosing sides (Jackson, 2014; Lim and Cooper, 2015; Mishra and Wang, 2024). In response to the scholarly consensus that “hedging” is inherently a risk management strategy for addressing structural uncertainties arising from great power competition (Han et al., 2023; Kuik, 2021; Lai and Kuik, 2021), Haacke (2019, p. 394) usefully clarifies that hedging methodologically entails “anticipatory” and “probabilistic” risk assessments of different future scenarios:

“The distinction between security risks and security threats is crucial. In contradistinction to security threats, security risks are probabilistic and usually assessed both in terms of their likelihood and potential magnitude. Significantly, if the management of risk is anticipatory and proactive, usually involving efforts to avoid, transfer, or reduce the former, threats are normally associated with an action-reaction dynamic.” (Haacke, 2019, p. 394)

This scholarly intervention highlights the relevance and suitability of anticipatory prescience as a methodological approach to hedging strategy in Southeast Asia.

3 Research questions

The review of key theoretical developments and research gaps identified above sheds light on future studies of hedging in Southeast Asia. In addition to generating “knowledge of understanding”, which previous studies have achieved, the relative shortage of “knowledge of anticipation” is necessary to fill the actual policy gaps of “contingency”, “worst scenario”, and “anticipate possibilities” (Goh, 2005; Matsuda, 2012). To effectively ascertain the security risks arising from the structural uncertainties in the U.S.–China great power rivalry, “knowledge of anticipation” should enable policymakers to envision different possible future scenarios and identify the plausible and probable scenarios in actual policy planning. These insights are essential for preparing for and pre-empting contingencies and avoiding worst-case scenarios. Therefore, the anticipatory approach and methodology of hedging strategy are warranted. To address these research gaps, the following questions will be explored in this article:

• Methodological issues: What does anticipation mean and entail as scientific knowledge? What would be the epistemology of anticipation? How can future scenarios be anticipated for strategic decision-making? What methodological steps could be taken to generate knowledge of anticipation relevant to the policy studies of Southeast Asian hedging strategy?

• Strategic issues: What might happen to Southeast Asia in the event of a Taiwan contingency? To validate the knowledge of anticipation for Southeast Asia, we will examine another sub-region along the “East Asian first-island chain”, where the U.S.–China rivalry is also prominent, for strategic and methodological triangulation. Thus, what might also happen to Northeast Asia in a Taiwan contingency? What are the possible, plausible, and probable scenarios in the case of the Taiwan contingency for the selected Northeast Asian and Southeast Asian countries?

• Policy issues: How would South Korea, the Philippines, and Vietnam react to the Taiwan contingency? What would their policy options be? What possible, plausible, and probable scenarios could unfold for South Korea, the Philippines, and Vietnam? What would be the worst-case scenario? What are their preferred/desirable future scenarios? How would Indonesia and the ASEAN headquarters plan for the Taiwan contingency? What is the most desirable/preferred scenario that the ASEAN headquarters should aim to achieve and shape in the Indo–Pacific region? In an extreme scenario, what options should ASEAN offer to Southeast Asian countries for consideration? How can we prepare for and enhance the likelihood of this preferred decision being chosen by the ASEAN member-states?

• Conceptual issues: How can we conceptually distinguish the hedging strategy from balancing/containment? What insights could the Philippines' hedging case study provide to clarify the conceptual difference between Southeast Asian hedging and American neorealist balancing/containment? How can we maintain and maximize the effectiveness of the hedging strategy? How can we proactively prevent events and mitigate factors that would lead to a reduction in hedging space, as well as erosion of maneuverability and flexibility?

4 Methodology

4.1 Promise of futures intelligence

Methodologically, anticipating international conflicts falls within the cross-disciplinary fields of futurology/future studies, foresight science, and intelligence studies, collectively referred to as “futures intelligence”. In this article, the prescient methods of “alternative futures analysis” and “multiple scenarios generation” are adopted to anticipate the possible scenarios and policy options that policymakers in South Korea, the Philippines, Vietnam, and ASEAN will need to consider (Pherson and Heuer, 2021: Chapter 9, Wong, 2022, p. 37–44). This section is dedicated to explaining this methodology in terms of its nature, approaches, tools, types of generated knowledge, and methodological steps to anticipate future scenarios.

The past three decades have witnessed the professionalization of future studies/futurology (Gary and von der Gracht, 2015). Various methods and diverse applications of futures intelligence are increasingly used by governments, transnational corporations, tech enterprises, banks, financial institutions, agribusinesses, marketing and polling companies, environmental organizations, and non-governmental organizations. In reference to the growing wealth of literature, the following paragraphs discuss the techniques and essence of futures intelligence (Asian Development Bank, 2020; Calof and Smith, 2010; Cook et al., 2014; Daheim and Uerz, 2008; De Graff, 2014; Dhami et al., 2022; Herring, 1992; Mandel and Irwin, 2021; Muller, 2009; Omand, 2014; Torres and Pena, 2021; Wee, 2001; Wirtz and George, 2022).

First, what is “futures intelligence”? As a cross-disciplinary field integrating futurology/future studies and intelligence studies, futures intelligence is considered essential for making successful strategic decisions. It provides analytical knowledge of anticipation regarding future changes, trends, and latent influences (Kuosa and Stucki, 2020). In general, futures intelligence aims to assess, judge, anticipate, and envision the effects of different events, trends, and phenomena on future developments. It can enable public and private organizations to achieve anticipated objectives in uncertain and challenging environments and enhance their chances of survival (Kuosa and Stucki, 2020).

Whereas, positivism assumes that objective reality exists “out there” and can evolve outside human consciousness, constructivism assumes that reality is contingent on, if not socially constructed by, human actors and their (inter)-subjectivity. The epistemological proposition of futures intelligence, however, allows interactions between objective reality and subjective preferences to take place, be re-imagined, and be shaped in the future. Because “futures intelligence” is by nature “anticipatory knowledge”, the key word “futures” should be in plural form, suggesting that futures intelligence practitioners need to consider and anticipate multiple future scenarios and their developmental possibilities (Mandel and Irwin, 2021, p. 2).

Having adopted futurology's three main methodological approaches—the probabilistic approach, the possibilistic approach, and the constructivist approach (Wong, 2022, p. 37–40)—futures intelligence can generate at least four types of anticipatory knowledge: plausible futures, probable futures, possible futures, and preferred futures (Kuosa and Stucki, 2020). International researchers agree that quality futures intelligence can be generated and achieved through the analytical technique of the “cone of plausibility” (Figure 2) (Dhami et al., 2022).

Figure 2. Cone of plausibility. Source: Swanson (2021). URL: https://knowledgeworks.org/resources/tool-exploring-plausible-probable-possible-preferred-futures/ (Retrieved on 10 May 2025).

4.2 Cone of plausibility

The tool of the “cone of plausibility” originated from the U.S. military in the late 1980s (Taylor, 1988, 1990). In the 2010s, a refined version was published by analysts at the Central Intelligence Agency (Pherson and Heuer, 2014). Nowadays, the British government (e.g., Ministry of Defense) continues to use the cone of plausibility to anticipate future scenarios, including planning for the impacts of major geopolitical events (e.g., Brexit) on the U.K.'s international trade and economic relations, immigration numbers, and level of international influence (Dhami et al., 2022).

Within the cone of plausibility, the “possible futures” include the widest range of future scenarios and possibilities. The “plausible futures” refer to the “more likely to happen” future scenarios that consider different factors of uncertainty. The “probable futures” refer to the “most likely to happen” future scenarios for which probability can sometimes be calculated. The “preferable futures” are the possible future scenarios envisioned and desired by people who wish to turn them into future reality (Swanson, 2021).

In other words, the “possible futures” may include the “plausible futures”, “probable futures”, and “preferable futures”. The “possible futures” and “plausible futures” are both anticipated from past events, known behaviors/actions, and identified causes. Using scientific reasoning techniques of deduction, induction, and abduction, the “probable futures” can then be generated from known facts, identified historical patterns, and existing theories. In reality, the “probable futures” have the highest likelihood of occurring. In comparison, although the “preferable scenarios” can be “plausible scenarios,” to avoid the undesirable “probable futures,” the “preferable scenarios” are meant to be identified and achieved through human or artificial efforts.

4.3 Four types of anticipatory knowledge

The “cone of plausibility” may generate four types of anticipatory knowledge as futures intelligence. First are megatrends, trends, and change drivers. Megatrends refer to global, long-term developments of change that have commercial, economic, social, and cultural impacts on society and individuals. Megatrends include multi-level interconnected phenomena that are very resistant to directional change. Examples are climate change, urbanization, and digitization. Trends are existing developments that continue historical developmental pathways. Examples are economic growth and the importance of cybersecurity. Change drivers are the future-shaping forces of development found inside and outside organizations, markets, or societies. These include new legislation, new consumption needs, technological change, and competitive divisions (Swanson, 2021).

The second type of anticipatory knowledge entails concrete descriptions of plausible scenarios. They are not necessarily accurate predictions of the future, but they can help explore and anticipate possibilities and prepare for unexpected events (Swanson, 2021).

The third type of anticipatory knowledge includes discontinuities, emerging issues, and weak signals. This futures intelligence knowledge is also known as horizontal scanning. Discontinuities and emerging issues are the “strong signals” of changes and trends. These strong signals can be exacerbated, weakened, or ceased and can represent the formation and formal emergence of new entities. In contrast, “weak signals” are early warnings of potential discontinuities, which include the research phase of a new technology. Weak signals are not public knowledge and are confined to a minority of people. However, weak signals can become trends, disappear, or evolve into early indicators of major incidents such as “wild cards” or “black swans” (Swanson, 2021).

Fourth type of futures intelligence knowledge may be generated by imagination, including “wild cards” and “science fiction”. The “wild cards” and “black swan” events are among the most impactful but have a low probability of occurrence. Based on existing phenomena, they often represent very bold anticipations. Their nature is accidental, unexpected, surprising, and they can lead to severe disruptions and shocks. Examples include the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2008 global financial crisis, and the September 11 terror attacks. Although “science fiction” can detach from reality, it can stimulate us to imagine future possibilities and visions beyond conventional thinking (Swanson, 2021).

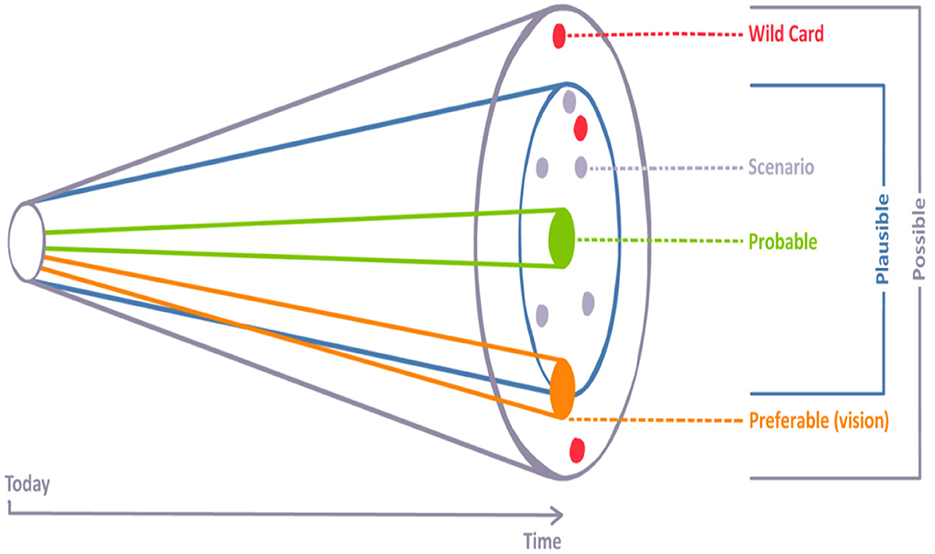

4.4 Executing two-axis four-quadrant anticipatory framework

A two-axis four-quadrant methodical framework is used for easy visualization and anticipation, allowing anticipators and decision-makers to envision future scenarios that deserve their attention and to concretize the worst-case scenarios to be avoided. This kind of futures intelligence work typically requires one or multiple teams of experts, researchers, and informed individuals as anticipators. The specific human intelligence gathering technique of the “Delphi panel” may be used (Gary and von der Gracht, 2015; Wong, 2022). Below are two figures for methodical illustration (Figures 3, 4).

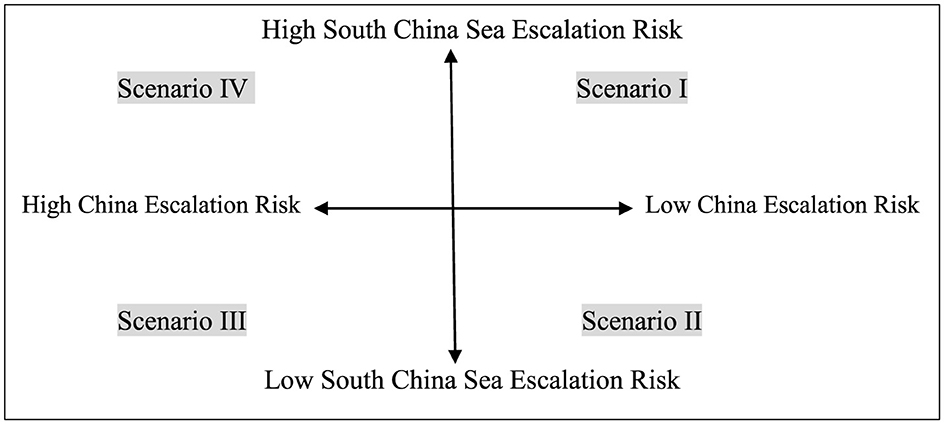

Figure 3. Anticipating Taiwan contingency: a two-axis model factoring in U.S. alliance risk and China escalation risk. Source: Author.

Figure 4. Anticipating Taiwan contingency: a two-axis model factoring in South China Sea escalation risk and china escalation risk. Source: Author.

Two axes should be chosen to construct the four-scenario framework, representing high uncertainties/impacts that can be clearly defined. For each axis, two extreme ends must be established. Four scenarios will be formed by combining the ends of the axes accordingly. A key question in populating the four quadrants resulting from the axes is: How do different vectors or change drivers influencing movement on the two axes affect the likelihood of stability (e.g., de-escalation or conflict) and options for policy intervention (e.g., complete neutrality or taking sides) manifest themselves in these scenarios? Examples of change drivers used in this research include U.S. alliance risk, China escalation risk, Korean Peninsula escalation risk, and South China Sea escalation risk.

The Philippines is selected because, while Manila is an active U.S. treaty ally hosting U.S. military personnel at its domestic bases, it is also a key disputant in the South China Sea maritime disputes. Vietnam is also chosen because, although Hanoi is not a U.S. treaty ally, it is a significant disputant in the South China Sea territorial disputes. To provide a control reference for validating the knowledge of anticipation in Southeast Asia, we select another sub-region along the “East Asian first-island chain,” where the U.S.–China rivalry is prominent for strategic and methodological triangulation. Thus, as an active U.S. treaty ally in Northeast Asia hosting U.S. troops and bases, South Korea is selected.

Scenarios are meant to be used, not just created per se. Scenarios are constructed and bombarded with one or several imagined “wild cards” (i.e., black swan and science fiction) events. A fifth scenario could optionally be created based on the occurrence of some wild card events. Scenario planning using academic language and modes of thought would not be sufficient to create a plausible and compelling set of futures. In contrast to conventional science's goal of establishing patterns, controlling variables, and predicting the future, futures intelligence aims solely to generate anticipatory knowledge, not predictive knowledge. It is important to create narratives that concretely describe and bring to life each imagined future scenario.

This methodology is not without limitations. The first limitation is that it is neither crystal ball gazing nor a fortune-telling exercise. Second, it is unable to accurately predict future developments in the positivistic sense. Instead, this methodology allows us to anticipate different scenarios so that we can pre-emptively discern what the worst (nightmare) scenarios might be and how to avoid them. Moreover, it aims to explore and facilitate various positive imaginations, transnational discussions, collective envisioning, and prudent strategic planning for international policymakers to anticipate, identify, and plan for the most preferable scenarios as an international community that cares about each country's welfare and the wellbeing of others.

5 Case study I: anticipating South Korean responses in a Taiwan contingency

Since 2023, a growing body of analyses contributed by American and British think tankers and scholars has aimed at foreseeing and anticipating the possible future scenarios resulting from a potential “Taiwan contingency” (Boyd et al., 2023; Mazarr et al., 2023; Taylor and Guan, 2024). A strategic and policy consensus has emerged: should the U.S. and China engage in armed conflict over Taiwan, the U.S. would no longer be able to guarantee a military victory with absolute certainty, due to the closing structural–strategic gap and military capabilities of the two great powers in recent years. Nonetheless, because Taiwan is an integral part of the “East Asian first island chain”, the U.S. would eventually need to garner diplomatic support and military assistance from Asian allies and partners for joint intervention in a Taiwan contingency. The U.S. clearly has a security interest and strategic intent in preserving the divided-rule status quo across the Taiwan Strait by preventing Beijing from unifying Taiwan by force or consent (Allison and Glick-Unterman, 2021; Davis, 2022; Evans, 2021; Freeman, 2021; O'Hanlon, 2022a,c; O'Hanlon et al., 2022).

In Asia, U.S. allies and military bases and facilities are mainly located in Northeast Asia (i.e., Japan and South Korea), Southeast Asia (e.g., the Philippines, Thailand, and Singapore), and the Indo–Pacific region (e.g., Australia and the Diego Garcia Islands). When planning for a Taiwan contingency, it is impossible to separate future scenario planning from the geostrategic flashpoints in the Korean Peninsula, East China Sea, South China Sea, South Asia, and the Indian and Pacific Oceans (Boyd et al., 2023; Mazarr et al., 2023; Taylor and Guan, 2024).

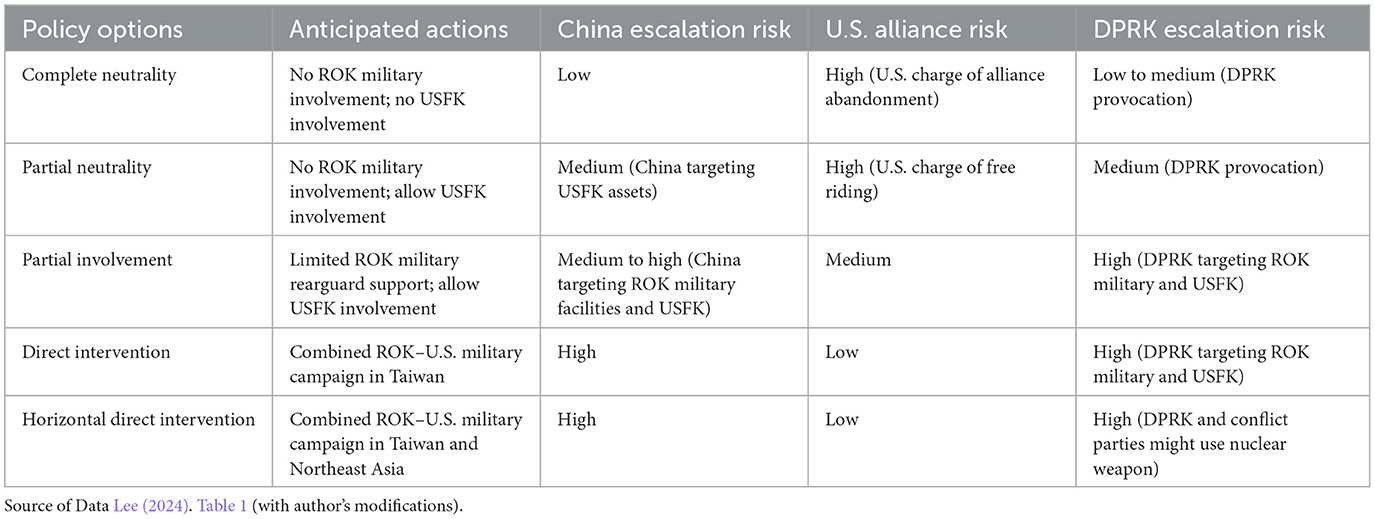

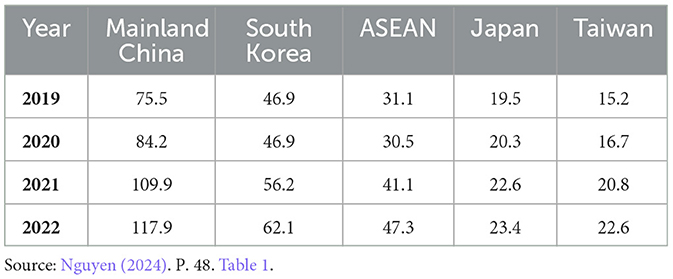

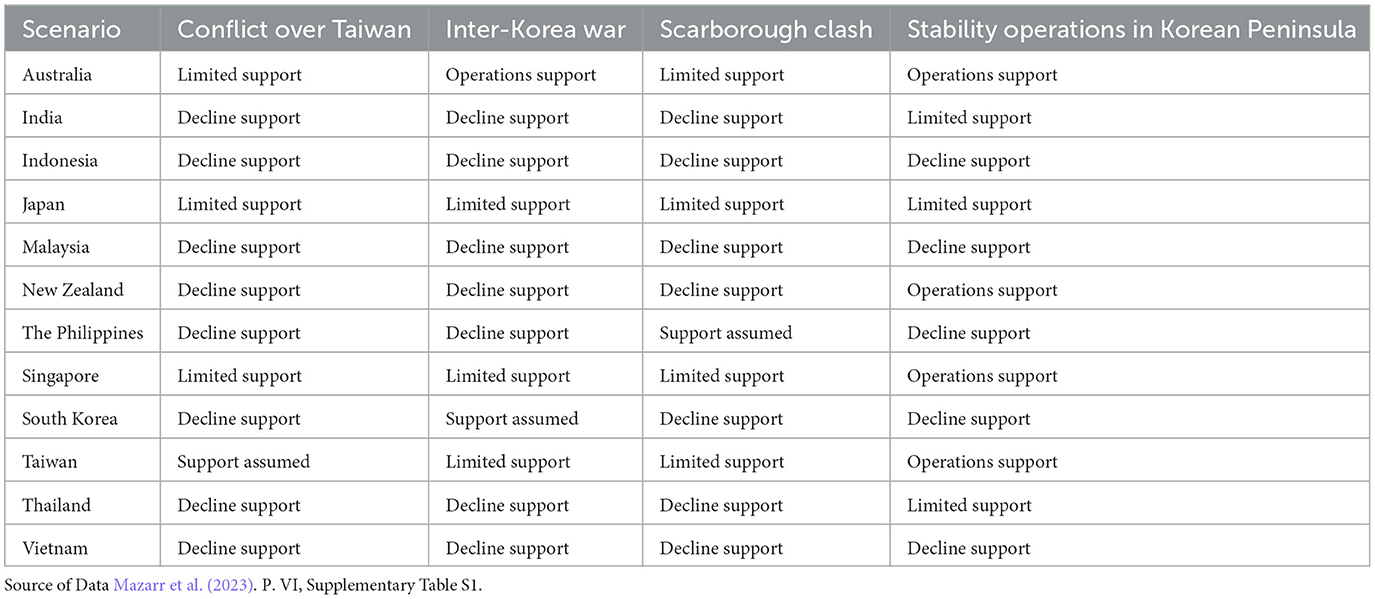

According to a 2023 research report published by the American defense think tank RAND Corporation, when considering whether Asian allies and partners would decide to participate in a U.S.-led joint military campaign in a Taiwan contingency, this question is actually geopolitically connected with the situation and stability on the Korean Peninsula and the territorial disputes in the South China Sea. In other words, when deciding whether to join the U.S. in militarily intervening in a Taiwan contingency, an Asian ally would need to factor in its own national security interests and the specific, more immediate flashpoints it is facing (Table 1).

Table 1. Likelihood of Ally/partner contributions to conflict scenarios in Northeast, East, and Southeast Asia.

The security and stability of the Korean Peninsula involve at least four countries that possess nuclear weaponry: the U.S., China, North Korea, and Russia. To pre-empt the worst-case scenario of a nuclear war, anticipating the Taiwan contingency should also involve anticipating the Korean Peninsula contingency.

Since the Cold War, North Korean threats have been South Korea's main national security concern. However, in recent years, Seoul has become increasingly aware of the worsening U.S.–China relations and the growing strategic–military gaps between the two great powers. In 2021, for the first time, Seoul made a joint announcement with the U.S. government regarding the importance of maintaining peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait. In 2023, another U.S.–South Korea joint statement publicly declared that maintaining peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait is essential for the region's security and stability. As of 2023, U.S. military bases in South Korea host about 28,500 U.S. troops. Given South Korea's geographical proximity to mainland China, Taiwan, the East China Sea, the Yellow Sea, and the Sea of Japan, South Korea is a key littoral hub of the “Sea Lines of Communication” (SLOCs) connecting Northeast Asia with the Indo–Pacific region. These recent geopolitical and geo-economic developments have gradually increased South Korea's vulnerability, making it more susceptible to being drawn into a major U.S.–China armed conflict over Taiwan (Lee, 2024).

During the Cold War period (1947–1989), South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK), Taiwan, and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam, 1955–1975) were U.S. allies on the Asian frontlines. While the three smaller Asian states commonly sought to reunify their nations with the lost or partitioned territories controlled by their communist competitors, South Korea and Taiwan actively sought to establish their own multilateral security alliances. During the Korean War (1950–1953), Taipei's Chiang Kai-shek government offered to send 33,000 troops to South Korea. During the Vietnam War (1955–1975), South Korea's Park Chung–Hee government deployed 300,000 troops to Vietnam to support South Vietnam. These actions indicated that Taipei and Seoul had similar policies in collaborating with the U.S. to counter the spread of communism in the region (Lee, 2024, p. 20–21).

Nonetheless, because of the U.S.-led “hub-and-spokes” alliance system in Asia, Seoul and Taipei rarely engaged in bilateral strategic coordination or mutual military arrangements. In the early 1970s, the U.S. formally recognized the People's Republic of China and established diplomatic ties with Beijing. The U.S. policy shifted from previously recognizing the Republic of China in Taipei to recognizing only the People's Republic of China as the legitimate government of China. The U.S. also withdrew troops from Vietnam in 1975. The Cold War ended in 1989. From 1991 to 1992, the end of the Cold War witnessed increasing domestic political pressure demanding the withdrawal of U.S. military bases from the Philippines, leading Manila to decide to close the U.S. military bases in the country. In 1992, South Korea also changed its recognition from the Republic of China (Taipei) to the People's Republic of China in Beijing as the legitimate government of China. These events reflected that the ideology of anti-communism was no longer effective in unifying the U.S., South Korea, Taiwan, and other Asian allies (Lee, 2024, p. 20–21). The importance of the U.S. alliance system was also in decline.

The U.S.-led “hub-and-spokes” alliance system implied that South Korea did not need to consider the defense needs of other U.S. allies. The 1953 Mutual Defense Treaty signed by the U.S. and South Korea stipulated that mutual defense was only applicable to scenarios in which either American territory or South Korean territory in the Pacific Ocean was attacked by a third-party country. In other words, the U.S.–South Korea security treaty neither covers the scenario in which a U.S. ally or partner country is under attack (such as Taiwan) nor applies to situations where U.S. military bases or personnel in Taiwan are attacked.

To many South Koreans, the purpose of the U.S. alliance was to mitigate threats from North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK). Fighting a war with America over Taiwan was outside the scope of the U.S.–South Korea treaty. In 2023, South Korean scholars suggested that it would be highly unlikely for South Korea to militarily intervene in a Taiwan contingency (Lee and Lee, 2023, p. 157). However, American think tank scholars did not rule out the possibility that U.S. military bases and/or American troops stationed in South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, and Australia could be used to support a potential Taiwan Strait conflict (O'Hanlon, 2022b). Scholars also cautioned that because Seoul would want the U.S. to honor its security guarantee to defend South Korea against North Korea and to avoid undermining the U.S.–South Korea alliance, Seoul would not prevent the U.S. Forces Korea (USFK) from intervening in a Taiwan conflict. A close strategic interconnection exists between the Taiwan Strait and the Korean Peninsula. It is evident that South Korea will inevitably be impacted by a Taiwan contingency (Cho, 2023; Hsiao, 2023; Lee, 2024, p. 24).

According to the anticipations presented in Table 2, if China and the U.S. engage in armed conflict over Taiwan, South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) would find it very difficult to adopt the policy options of “complete neutrality” and “partial neutrality”, simply because these options would conflict with South Korean national security interests. These two options would not only damage the U.S.–ROK alliance and strategic trust but would also undermine the security guarantee that the U.S. provides to defend South Korea from North Korean threats. In a scenario where North Korea exploits a Taiwan contingency to launch attacks against South Korea, South Korea would need U.S. military support to aid in its defense.

The remaining policy option for South Korea would then be “partial involvement”. Originally, this option was mainly intended to decrease the likelihood that the ROK military would become tactical targets of the Chinese military. However, it would also make ROK military facilities and USFK assets potential tactical targets of the Chinese military. Because the U.S.–China conflict over Taiwan is unlikely to be resolved quickly, a protracted war could escalate into the “direct intervention” policy option, leading to a scenario where the ROK military joins the U.S. military to fight China over Taiwan. This situation would also increase the likelihood of North Korea attacking South Korea and the USFK, dragging the entire Korean Peninsula into a Taiwan military conflict. This policy option of “horizontal direct intervention” in a regional war would not only represent the “worst scenario nightmare” for South Korea but also raise the risk of an international nuclear armed conflict in Northeast Asia and beyond.

Whereas Beijing would strive to contain potential armed conflict with the U.S. to Taiwan, the U.S. would seek to internationalize the Taiwan conflict to encourage joint military intervention from its regional allies. A Taiwan contingency would likely spill over into Northeast Asia and the South China Sea, where Beijing, Taipei, the Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia, and Indonesia have overlapping territorial claims. However, from the perspective of South Korea, the worst scenario to avoid would be the spillover effects of the Taiwan conflict on the Korean Peninsula. The preferred future scenario would be the absence of any U.S.–China armed conflict over Taiwan. Therefore, it is in South Korea's interest to proactively prevent a Taiwan contingency from occurring. Proactively preserving the current peaceful status quo across the Taiwan Strait appears to be the best policy option for Seoul to consider.

As the Taiwan Strait is also geopolitically connected to the South China Sea, when South Korea considers devising a proactive policy to prevent a Taiwan contingency, Seoul would naturally need coordination and input from Southeast Asia. This would require a closer examination of the Philippines' hedging strategies, which have elicited divergent views among scholars.

6 Case study II: anticipating Philippine responses to Taiwan contingency

Whilst the majority of scholars agree that the Philippines has been practicing evolving strategies of hedging (which include varying extents of balancing and bandwagoning acts) (Askari and Tahir, 2021; Banlaoi, 2021; De Castro, 2009, 2021; Liou and Hsu, 2017; Liu, 2024; Rodier, 2022; Tang, 2021; Weerasena, 2024; Wong, 2018: Chapter 2), a minority but influential scholarly position has persistently argued that the Philippines has actually been practicing (pure) balancing against China, which may imply containment (Kuik, 2016b: 169; Kuik, 2024). This minority position of “Philippine exceptionalism” deserves closer examination, promising a more comprehensive understanding of hedging strategies in Southeast Asia and allowing us to conceptually distinguish hedging from balancing and containment. Using the current administration of President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Romualdez Marcos Jr. (2022–present) for ethnographic fieldwork investigation, anticipation, and scenario planning, the following paragraphs illustrate why the Philippines has indeed stood out as an exception in Southeast Asian hedging.

Shortly after Marcos Jr. was inaugurated as the Philippine president in June 2022, I was invited by City Mayor Mrs. Maila Rosario Ting-Que to visit Tuguegarao City, the capital of Cagayan Province and the Cagayan Valley (Administrative Region II) in northern Luzon, in August 2022. After landing at Tuguegarao City airport, I was met by Mayor Ting-Que and the Philippine National Police regional commander. A government vehicle drove me to the mayor's residence—the Hotel Delfino. After I checked into the hotel, the mayor communicated with the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Tuguegarao, the Most Reverend Ricardo Baccay, for me to visit his office in the afternoon. In the following days, I met and discussed matters with other Philippine officials, professionals, lawyers, researchers, and businesspeople in meetings inside the hotel, the mayor's office, and other designated venues.

A field trip was also arranged to visit the Archdiocese-administered higher learning institutions—the Lyceum of Aparri and the Thomas Aquinas Major Theological Seminary—along the northern coast of Cagayan Province. In Aparri, in addition to meeting with faculty members, I engaged with students, informed researchers, senior clergy, and parishioners about the evolving geopolitical situation facing the coastal community. I was accompanied by clergy to visit selected locations along the northern coast, including government offices, mining fields, construction sites, coastal farmlands, parishes, and abandoned buildings and machinery left by China-related entities. From the 1st day's contacts and conversations with the mayor, police, and the Archbishop, I understood that this trip involved governmental representatives and the Catholic Church's policymakers. While I assessed the local situations against the backdrop of superpower geopolitics, I was able to engage with various local perspectives and offer my initial assessments during this trip for the Philippine government and the Catholic Church.1

As a cultural pattern in Philippine local and national politics, Mayor Maila Ting-Que's family members have also served in the governments of Tuguegarao City and Cagayan Province, as well as in the Philippine Congress, as elected mayors, councilors, and congressmen since 1986. During the martial law regime (1972–1986) under former President Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos Sr. (current President Marcos Jr.'s late father), northern Luzon was the political stronghold of the Marcos family, which hails from the adjacent Ilocos Norte Province. Mayor Maila Ting-Que's late father, former Tuguegarao City Mayor (1988–1998; 2007–2013) Mr. Delfin Telan Ting (1938–2022), aligned with the Marcos Sr. government's anti-communist ideology and counter-insurgency policies when Cagayan Province was troubled by communist insurgency. Since then, the two political families have become long-time allies.

In the 2022 national election, the Ting family campaigned for Marcos Jr.'s presidency. For more than two decades, my relationships with the Philippine political elite have deepened as my research on the Philippines continues (Wong, 2024). My August 2022 field trip to northern Luzon and Manila, along with post-fieldwork research, generated several key findings for anticipating Philippine responses to a Taiwan contingency.

In the first place, Taipei has already controlled three disputed islands in the South China Sea. The first is the Pratas Islands (Tungsha Islands; 東沙群島), which are administered by Taiwan's Kaohsiung City government and disputed by the Guangdong Provincial government of the People's Republic of China. The Pratas Islands occupy a geostrategically sensitive location as the maritime mid-point connecting southern Taiwan (410 km), Hong Kong (320 km), and northern Philippines (490 km); they connect the SLOCs leading to (1) the Taiwan Strait, (2) the Luzon Strait, and (3) the South China Sea (Figure 5). As of November 2020, about 500 Taiwanese marines were stationed on the Pratas Islands. The main island has a network of underground bunkers. Given the geostrategic location of the Pratas Islands, recent PLA military exercises in nearby areas were perceived to show an intent to cut off supply lines connecting Taiwan and the Pratas Islands in a Taiwan contingency scenario.

Figure 5. Geostrategic Location of the Taiwan-Controlled Pratas (Tungsha) Islands in the South China Sea. Source: Forum IAS (2020). https://forumias.com/blog/pratas-islands-a-new-flashpoint-in-the-south-china-sea/ (Retrieved on 23 October 2024).

The second Taipei-controlled disputed island is Taiping Island, which is the largest in the entire disputed Spratly Islands (Figure 6). While it is administered by Taiwan's Kaohsiung City government, it is also disputed by Beijing, Vietnam, and the Philippines. On Taiping Island, Taiwan authorities have maintained electricity generators, an aircraft runway, a hospital, radar equipment, a lighthouse, and military facilities. Through Taiping Island, Taipei has also maintained control over the adjacent uninhabited Zhongzhou Reef by regularly having it patrolled by Taiwan's Coast Guard Administration.

Figure 6. Location of Taiping Island in the South China Sea. Source: Yeh et al. (2021). URL: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84434-z (Retrieved on 23 October 2024).

The strategic value of Taiping Island for the Taipei government is significant; it serves as Taiwan's pivot in the South China Sea. In January 2013, the Philippines initiated arbitration proceedings against China in the Permanent Arbitration Court (The Hague) under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), including China's historic rights and sovereignty claims over parts or all of the Spratly Islands. The Philippines won the case in 2016, but like Beijing, Taipei also did not recognize the ruling.

The second finding concerns how changing U.S.–China dynamics in recent years across the Taiwan Strait have caused major changes in the Philippines' assessment of its external security environment. Manila has had to deal with at least three anticipated future scenarios of complex security challenges (Patton, 2022).

First anticipated scenario: If armed conflict occurs over Taiwan, the Philippines will inevitably be impacted due to its geographical proximity to Taiwan. During the Vietnam War (1955–1975), thousands of South Vietnamese soldiers and refugees evacuated from Vietnam to the Philippines, causing humanitarian crises. It was estimated in 2022 that there were at least 200,000 overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) living and working in Taiwan. The families of these OFWs in the Philippines would likely have a significant influence on the Philippine government's decision-making in a Taiwan contingency. Philippine government officials have already outlined emergency evacuation plans from Taiwan (Patton, 2022).

Second anticipated scenario: If Beijing succeeds in reuniting Taiwan, Manila's territorial claims in the South China Sea will be jeopardized. The 2016 Philippines' international legal arbitration victory over Beijing under UNCLOS was not recognized by Beijing. This arbitration outcome, however, worsened China–Philippines relations. Since the Philippines filed the arbitration case in 2013, China has built military-use artificial islands in the South China Sea, which further constitutes serious national security threats to the Philippines. When Beijing seeks to take control of Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait, the Chinese military will also seek to control the disputed islands and islets in the South China Sea occupied by Taipei. This would aim to expand China's military control in the South China Sea, which would be detrimental to Philippine national security. The Philippines would therefore wish to preserve the current divided-rule status quo across the Taiwan Strait (Patton, 2022).

Third anticipated scenario: The U.S. military's controversial withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 significantly weakened America's credibility among its Asian allies. The Philippines was also concerned about the diminishing military-strategic advantage that the U.S. previously held over China (Allison and Glick-Unterman, 2021; O'Hanlon, 2022b). As the Philippines is America's treaty ally, there is a high risk that it could be affected by, if not dragged into, a cross-Strait conflict between Beijing and Taipei, as well as America. However, if the U.S. decides not to aid Taiwan, Manila would need to seriously consider adopting a stance of neutrality in a Taiwan contingency. Additionally, if the Philippine government decides to militarily support the U.S., Manila is likely to be accused by Beijing of collaborating with the U.S. to contain China militarily. The Philippines would then become a tactical target for the Chinese military. Under the ongoing trend and turbulent dynamics of U.S.–China decoupling, a Taiwan contingency scenario has created a significant security dilemma for Manila, leading to strategic passivity that limits the Philippines' options for maneuvering and hedging between the U.S. and China.

The third key finding was established through my field research in the northernmost Philippine coastal province of Cagayan in August 2022. Cagayan is the nearest Philippine province to Taiwan, with its islands located only about 190 km from the southern coast of Taiwan. The geostrategic islands of Cagayan (e.g., Fuga Island) control access to the Luzon Strait shipping lanes, which connect the Pacific Ocean, the South China Sea, and the Taiwan Strait, as well as the trans-Pacific submarine cables. In April 2022, for the first time, the U.S. military and the Philippine military conducted their joint “Balikatan (Filipino language meaning: shoulder-to-shoulder)” military exercise along the coast of Cagayan Province (Editorial, 2022; Mangosing, 2022a,b; Ong, 2022). It is safe to suggest that Cagayan Province and its islands in the Luzon Strait are part of the “East Asian first island-chain”.

Philippine analysts reported that in recent years, Chinese enterprises attempted to invest in Fuga Island and the nearby maritime area. These proposals were opposed by the Philippine military and the Philippine Department of National Defense (Crismundo, 2020; Heydarian, 2019). Since 2007, mining operations by China and other East Asian countries have existed in the Cagayan River Valley and the Luzon Strait. Coastal mining activities by Chinese companies also caused disputes involving the government and the church, along with protests and conflicts from local farmers, fishermen, and communist insurgents (Saludes, 2021; Wong et al., 2013, 2015). My August 2022 fieldwork suggested that attempts to purchase coastal farmland by alleged Chinese proxies were rejected by local Filipino landowners. Monetary gifts made by these alleged proxies to the Roman Catholic Church were also intercepted and rejected by the Archbishop of Tuguegarao.

For more than two decades, businesspeople of Chinese citizenship have operated offshore online gaming and physical gambling facilities in the Philippines, specifically in the northeastern port town of Cagayan Province, Santa Ana. These offshore gaming and gambling facilities were licensed by the Philippine government. They were allowed to operate exclusive casinos solely for foreign tourists, particularly those coming from mainland China. According to sources in the Philippine Catholic Church, in recent years, as tensions across the Taiwan Strait grew, parishioners noticed an increased presence of military-aged Chinese individuals in Santa Ana. One day in 2022, a parishioner found a wallet on the street that contained an unverified identity card of the People's Liberation Army (PLA). While the wallet was handed to the Philippine police, the Catholic Church also reported the unusual incident to Philippine military intelligence. Local suspicions had already suggested that alleged PLA intelligence agents or scouts were present in Santa Ana and the adjacent coastal areas. The perceptions I gathered in Cagayan Province and Manila indicated that because Cagayan Province's geographical proximity to the Taiwan Strait and its geostrategically sensitive location, if an armed conflict were to occur over Taiwan, Cagayan Province would likely become a battlefield, and the entire Luzon Island would inevitably be impacted.

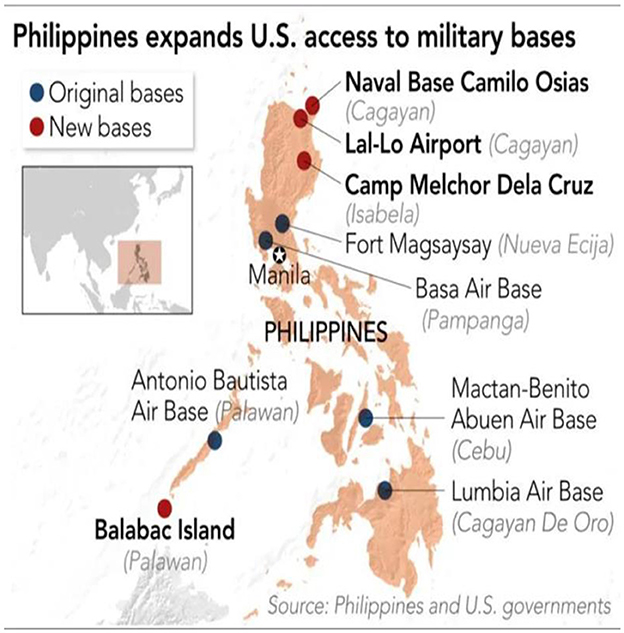

The fourth key finding concerned the Marcos Jr. government's 2023 decision to install new U.S. military bases in Cagayan Province and northern Luzon (Figure 7) (Cepeda, 2023; Editorial, 2023; Venzon, 2023). In 2014, former Philippine President Benigno Aquino III signed the “Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA)” with the Obama administration. EDCA was judged by the Philippine judiciary to be constitutional in 2016. By allowing the U.S. to use five Philippine military bases for training, infrastructure construction, storage facilities, and other mutually agreed activities, EDCA aimed to strengthen U.S.–Philippines security cooperation. In 2020, the Duterte government requested Beijing to comply with the 2016 South China Sea international arbitration outcome, which worsened Philippines–China relations. From 2016 to 2022, in an attempt to avoid escalating conflict with Beijing, former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte did not implement the respective EDCA clauses that allowed U.S. access to and use of Philippine military bases.

Figure 7. Locations of EDCA Philippine Military Bases for U.S. Access and Use. Source: Venzon (2023). URL: https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/South-China-Sea/Philippines-U.S.-hold-biggest-ever-drills-to-counter-China (Retrieved on 23 October 2024).

When Marcos Jr. was elected president in 2022, some Philippine scholars suggested that the Philippines' hedging strategy regarding the U.S.–China relationship necessitated a review and fine-tuning. A main driver was that the intensifying U.S.–China competition had recently evolved into economic–technological decoupling and a new Cold War. As Southeast Asia's major treaty ally, the Philippines faced increasing structural pressures and uncertainties to take sides. However, continued turbulence in American domestic politics, the U.S. military's chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, and the growing military-strategic distance between the U.S. and Chinese militaries have led the Philippines to recognize that the U.S. may not be able to guarantee a decisive military victory in a Taiwan contingency. If the Philippines chooses to fully align with the U.S., an open war scenario with China will bring tremendous misery and suffering to the Filipino people.

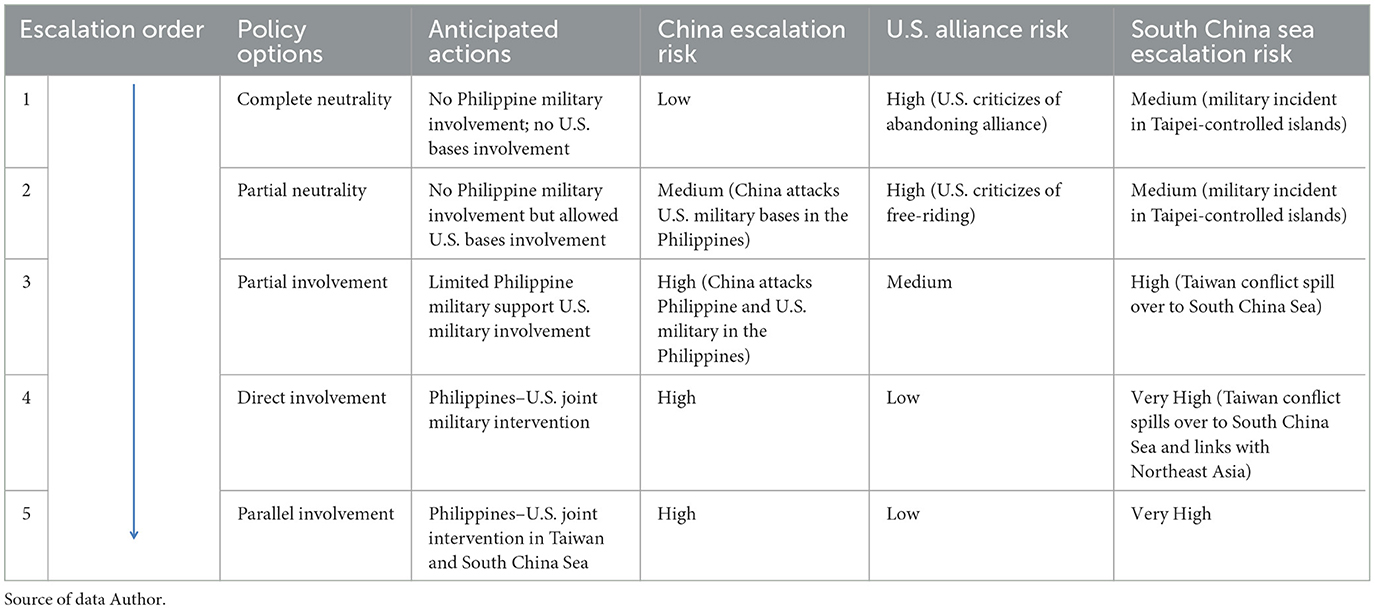

Therefore, in contrast to Duterte's hedging strategy aimed at de-escalating conflict with China, the Marcos Jr. government's hedging strategy has clearly shifted toward a more specific anticipatory strategic purpose of balancing against a Taiwan contingency worst scenario, which also aims to prevent the Philippines from being dragged into a regional war (Table 3). In particular, Marcos Jr.'s major decision was to allow the U.S. military access to the following three new Philippine military bases in the Cagayan Valley Region:

• Naval Base Camilo Osias, Santa Ana, Cagayan Province.

• Lal-Lo Airport, Cagayan Province.

• Camp Melchor Dela Cruz, Isabela Province.

I consider these to be President Marcos Jr.'s primary strategic and security considerations: a Taiwan contingency would likely lead to the following undesirable/worst scenarios. The Philippines had to resort to the above EDCA-approved U.S. military basing measures to prevent or deter the anticipated escalations of armed conflict from occurring across the Taiwan Strait and into the South China Sea.

First, a Taiwan contingency will cause ~200,000 Filipinos/OFWs in Taiwan to return to the Philippines. This scenario will negatively impact the Philippine economy by cutting off remittance incomes and economic benefits coming from Taiwan.

Second, a Taiwan contingency will result in an unprecedented number of war refugees and political asylum seekers flooding from Taiwan into the Philippines. This would not only lead to major humanitarian crises and suffering but also weaken the Philippines' national security and internal social stability.

Third, a Taiwan contingency will prompt the U.S. and its allies to impose sweeping economic and financial sanctions on China. Because mainland China has been the largest trading partner of the Philippine economy, the China–Philippine trade flows and economic volumes will be severely curtailed by these sanctions. The Philippine economy will be significantly damaged, leading to widespread unemployment, a major economic crisis, devaluation of the Philippine peso, and social unrest.

Fourth, in a Taiwan contingency, Beijing would seek to militarily take over the Taipei-controlled islands in the South China Sea, which the Philippines and Vietnam also claim. A U.S.–China armed conflict over Taiwan could easily escalate and spill over into an international conflict in the South China Sea. This would significantly undermine ASEAN's unity and ongoing efforts to resolve maritime–territorial disputes peacefully and orderly, and it could potentially weaken the Philippines' sovereignty claims and legal rights in the South China Sea disputes.

Fifth, in a Taiwan contingency, because of the Philippines–U.S. alliance and the EDCA military basing arrangements that already grant the U.S. access to Philippine military bases, it is nearly impossible for the Philippines to adopt a “complete neutrality” or “partial neutrality” policy. It is reasonably anticipated that, in the escalations from the point of “partial involvement” onward, the Philippines will eventually join U.S. forces in a full-fledged war against China over Taiwan and the South China Sea, and potentially in Northeast Asia (Table 3).

In summary, President Marcos Jr.'s decision and motivation to allow the U.S. military back into Philippine bases were neither to express support for the “Taiwan independence” forces, nor primarily aimed at helping the U.S. offshore-balance or contain China, nor to exhaust China's resources. Instead, Marcos Jr. intended to leverage the U.S. alliance and security guarantees to deter a Taiwan contingency, in order to protect the Philippine national economy and security interests, maintain domestic social stability, and uphold the country's legal rights in the South China Sea. These were essential for the legitimacy of Marcos Jr.'s regime.

7 Case study III: anticipating Vietnam's responses to Taiwan contingency

Unlike Japan, South Korea, Australia, and the Philippines, most Southeast Asian countries today are not U.S. treaty allies. They are less constrained by factors such as the U.S. alliance treaty, the stationing of U.S. forces, and military basing arrangements. When anticipating how Southeast Asia would respond to a Taiwan contingency, the considerations of these Asian partners warrant our attention. Vietnam is therefore chosen for examination. A primary reason is that, as one of the competing claimants of the disputed Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, like the Philippines, Vietnam also has overlapping sovereignty claims on the Taipei-controlled Taiping Island (Chinese: 太平島; Itu Aba) and Zhongzhou Reef (Chinese: 中洲礁; Ban Than Reef). Taiping Island is adjacent to three Vietnam-controlled islands: Namyit Island, Sand Cay, and Petley Reef, which are also disputed by Beijing, Taipei, and Manila (Nguyen, 2024, p. 53).

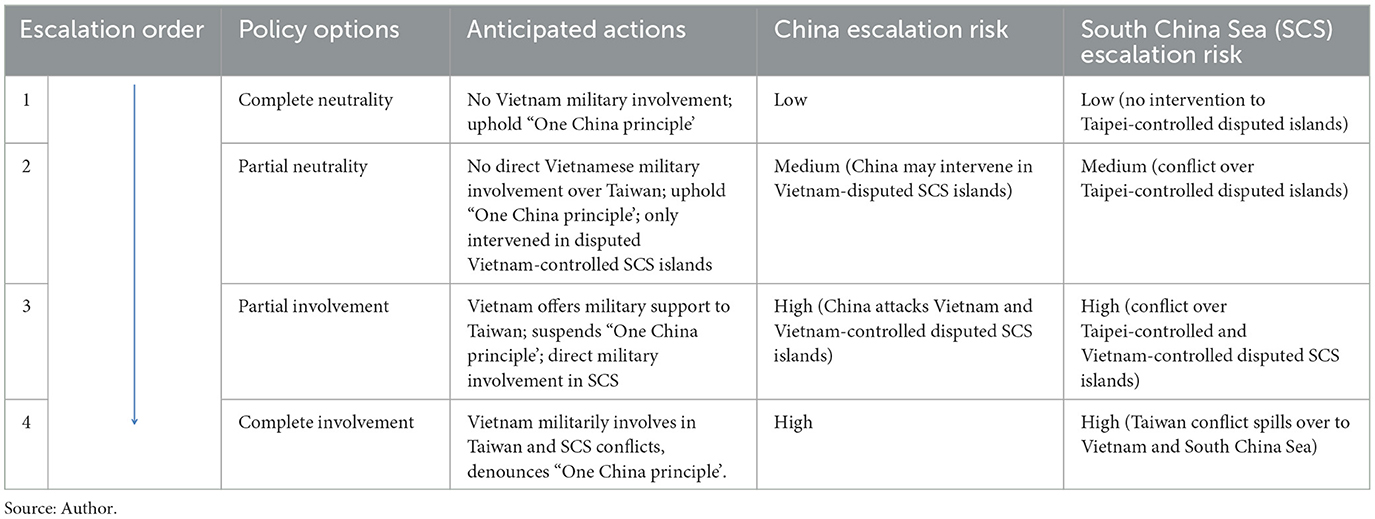

If the U.S. and China engage in armed conflict over Taiwan, the Philippines will likely be militarily involved (as anticipated in the previous section), which would likely trigger further armed conflicts in the disputed South China Sea. Vietnam would naturally fear that the dual conflicts in Taiwan and the South China Sea will weaken its existing interests, sovereignty claims, and rights in the region. Moreover, because the South China Sea disputes involve multiple parties, despite Vietnam considering staying neutral at the beginning, Hanoi would soon find itself possibly entangled in a series of concomitant conflicts with various parties across multiple theaters. However, the outcome of such a multi-frontal conflict scenario would not necessarily be favorable to Vietnam. A Taiwan contingency has therefore created an anticipated series of security dilemmas for Vietnam.

I believe that Vietnam does not wish to see a Taiwan contingency occur because such a crisis would likely escalate conflicts and lead to multiple crises for Vietnam (Table 4). These conflicts and crises would bring substantial uncertainties and security risks to Hanoi, which would seriously damage Vietnam's internal stability and economic development.

In the first place, Vietnam supported Beijing's “One China principle”. Hanoi did not maintain formal diplomatic relations with Taipei. During the Vietnam War (1955–1975), given their common anti-communist cause, Taipei's Kuomintang government maintained formal relations with the government of South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam; 1955–1975). After the Vietnam War, North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) unified South Vietnam and established the “Socialist Republic of Vietnam”, which exists to the present day.

It was only in 1992 that Taipei re-established informal relations with Hanoi by setting up the “Taipei Economic and Cultural Office” in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. In 1993, while successfully signing a bilateral investment agreement with Taipei, Vietnam established its own economic and cultural offices in Taiwan. Since then, Taiwan has been a major investor in Vietnam. By the end of 2022, it was estimated that there were 2,900 Taiwan-invested projects in Vietnam, with a total value of 36 billion U.S. dollars. From 2019 to 2022, Taiwan was also among Vietnam's top five importing countries, surpassing the U.S. and the European Union (E.U.) (Table 5). The main commodities in Taiwan–Vietnam bilateral trade included computers, electronic products, parts and components, and machinery. Vietnamese local governments actively attracted Taiwanese companies to invest in the electronics and semiconductor industries by offering special policy concessions and administrative convenience to Taiwanese enterprises (Nguyen, 2024, p. 48).

As of 2023, Vietnam's economic and cultural office in Taiwan estimated a total of 400,000 Vietnamese living in Taiwan. Approximately 250,000 of them were part of Taiwan's active labor force, mainly serving in the manufacturing, healthcare, and home care service sectors. Under the Taipei government's active implementation of the “New Southbound Policy” (Chinese: 新南向政策) since 2016, Vietnam aimed to deepen relations and expand cooperation with Taiwan in education, tourism, trade, and talent exchange (Nguyen, 2024, p. 49).

Since 1986, when Vietnam adopted Deng Xiaoping's policy to implement economic reforms (Vietnamese: Ðôi Mói), Hanoi has pursued a multilateral and “omnidirectional foreign policy” (Nguyen, 2024, p. 54). Since then, Vietnamese policy has aimed at establishing itself as a reliable partner and friend to all nations. Vietnam has not only managed to mend relations with the U.S. and China but has also normalized its relationships with Southeast Asian neighbors. This policy has helped Vietnam create a stable external security environment for national economic development. The economic pragmatism behind this policy explains why Vietnam seeks to deepen its economic and trade relations with Taiwan. Moreover, Vietnam is eager to learn from Taiwan's successful industrialization experience and economic development miracle, enabling Vietnam to become another high-end industrialized, developed economy (Nguyen, 2024, p. 50).

For Vietnam, a Taiwan contingency would likely lead to at least three overlapping crises. First, the fate of the 400,000 Vietnamese living in Taiwan would be in question. In February 2022, when the Russia–Ukraine War began, Vietnam managed to evacuate 2,600 citizens from Ukraine. However, this evacuation process faced difficulties, as these citizens needed to find their own ways to reach airports in Poland and Romania before boarding the arranged flights. In a Taiwan contingency, Vietnamese citizens would likely request the Hanoi government to evacuate the 400,000 Vietnamese from Taiwan. This challenging mission could lead to serious humanitarian crises and refugee problems that would undermine Vietnam's domestic political stability (Nguyen, 2024, p. 51–52).

Second, a Taiwan contingency would seriously disrupt or even halt trade and investment flows between Taiwan and Vietnam. This disruption would cause significant shortages of critical commodities, negatively affecting Vietnam's production and exports. One of the most affected sectors would likely be Vietnam's fast-developing semiconductor industry. Taiwan is a major production base for semiconductors and chips, accounting for 92% of the world's most advanced semiconductors and one-third of high-end complex chips. A Taiwan contingency would severely impact global chip flows and semiconductor supply chains. Vietnam's ambitions and plans to become a future manufacturing base for semiconductors would likely be frustrated and suspended (Nguyen, 2024, p. 52).

Third, a Taiwan contingency would prompt many foreign investors and enterprises to withdraw from the markets of mainland China and Taiwan. While Vietnam might benefit from the reallocation of these investments in the long run, it would immediately suffer significant losses in its trade with China, its largest trading partner in recent years (Table 4). Western financial sanctions against China would also severely impact global trade, from which Vietnam has benefited. A Taiwan contingency would likely lead to surging unemployment rates, drastic economic contraction, and significant currency devaluation, resulting in a multi-layered national economic crisis for Vietnam.

Fourth, a Taiwan contingency would likely spill over into the disputed islands in the South China Sea. For instance, Vietnam would need to prepare contingency plans to respond to any armed incidents on the Taiwan-controlled Taiping Island (Nguyen, 2024, p. 53). If China and the U.S. engage in armed conflict over Taiwan, Vietnam's national development strategy, which depends on a stable external security environment, would be jeopardized. The Hanoi government would be forced to alter Vietnam's multilateral diplomacy and omnidirectional foreign policy adopted since 1986. Vietnam would then face greater structural pressures from a new Cold War, forcing it to take sides. Such a policy shift could trigger uncertainties, diplomatic conflicts, domestic instabilities, and political crises.

In sum, Vietnam does not consider a Taiwan contingency scenario to be in its interest at all; Hanoi has good reasons to want to prevent such a scenario. A Taiwan contingency would lead to multiple crises for Hanoi. Naturally, Hanoi would wish to collaborate with ASEAN and external partners to prevent it from occurring. Preserving the current divided-rule status quo across the Taiwan Strait and pre-empting a Taiwan contingency seems to be a viable, if not the only, way forward that ASEAN member-states and external partners should consider in order to reach consensus and resolutions.

8 Conceptual innovation: toward anticipatory hedging

The above case studies have contributed several novel conceptual advances to Southeast Asian hedging strategies. First, hedging is conceptually distinguished from balancing, which suggests containment. The hedger's core strategic self-identity and intent differ from those of the offshore-balancer, who may inadvertently or deliberately work for an external great power to balance against, contain, or weaken the neighboring great power in dispute. The hedger's primary strategic intent is to strategically use the great power rivalry to achieve its own national security goals and enhance its capacity to defend territorial integrity and sovereignty from the disputing great power.

Second, in response to scholarly concerns that the shrinking space for hedging and erosion of maneuverability are being exacerbated by the U.S.–China great power rivalry and the potential for armed conflict, this article demonstrates that a futurist methodology of anticipation can not only mitigate the problems of shrinkage and erosion but can also proactively preserve and pre-emptively enlarge the space, agency of maneuverability, strategic flexibility, and range of hedging policy options.

In other words, anticipation adds a new conceptual dimension to the existing dualism of hedging found in Figure 1. Using the two-axis four-quadrant anticipatory framework for illustration, the advanced hedging model is now represented in Figure 8. With the practice of a new anticipatory hedging strategy (distinguished from non-anticipatory hedging strategy), the anticipator-hedger would be more capable of astutely utilizing selected policy tools from neorealism, neoclassical realism, and norms competition to increase strategic maneuverability, gain flexibility, expand policy options, and enjoy a higher degree of freedom to hedge against future uncertainties, at least pre-emptively identifying and preventing the worst-case scenario from occurring.

9 Conclusion

In conclusion, several key lessons have been learned. First, on the one hand, the rise of China over the past three decades has brought significant economic and trade benefits, as well as developmental opportunities, for Southeast Asia to enhance national economies and regional development. On the other hand, territorial disputes in the South China Sea and China's growing political influence and military might have also introduced new security risks arising from the structural uncertainties not only of a rising China but also of intensifying China–U.S. geopolitical-economic competition in the Indo–Pacific region. Regional flashpoints in the South China Sea, East China Sea, and the Korean Peninsula are strategically interconnected with stability across the Taiwan Strait. A Taiwan contingency would likely spill over into other regional flashpoints, potentially triggering concomitant armed conflicts in Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia. Depending on the circumstances, a Taiwan conflict might even spill over into flashpoints in South Asia and territorial disputes in the Himalayas.

Second, Southeast Asia's hedging strategies are believed to have brought positive economic gains and significant trade benefits to smaller, medium-sized, and emerging powers in the Indo–Pacific region. Additionally, these hedging strategies have been effective due to U.S. security guarantees, military provisions, and alliance partnerships. The U.S.'s economic and security presence in Asia is regarded as an asset to hedge against structural uncertainties and security risks arising from a rising China, but it could also be a source of geopolitical tension and potential armed conflict because of the intensifying U.S.–China great power rivalry.

Third, a Taiwan contingency would significantly shrink the strategic maneuvering room for small- and medium-sized states in Southeast Asia and Northeast Asia. In the case of U.S. allies like South Korea and the Philippines, assuming U.S. military intervention in a Taiwan contingency against China's armed invasion, these allies would be under unprecedented pressure to honor and uphold the U.S. alliance in defending against national security threats from North Korea and China in the Korean Peninsula and South China Sea, respectively. As a result, they would likely join U.S. forces in armed conflict against China over Taiwan.

Given that a Taiwan contingency would likely spill over into the Korean Peninsula and South China Sea, it is in the interests of both South Korea and the Philippines to prevent such a contingency from occurring. Preserving the current peaceful divided-rule status quo across the Taiwan Strait aligns with the interests of both South Korea and the Philippines.

For non-U.S. treaty allies in Southeast Asia, such as Vietnam, a Taiwan contingency would likely expose Hanoi to increased vulnerabilities and security risks both domestically and internationally. With 400,000 Vietnamese living and working in Taiwan, the Hanoi government would quickly find itself embroiled in multiple overlapping domestic political, economic, humanitarian, and international crises that would significantly undermine the legitimacy of the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam.