- 1Institute of Ethnic Studies, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia

- 2Research Center for History, Politics and International Affairs, Faculty of Social Science and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia

Introduction: Indigenous Peoples play a vital role in democratic systems; however, their political participation is often hindered by structural barriers, including limited access to fundamental infrastructure and services, lack of formal recognition of land rights, and systemic discrimination. Despite the growing global discourse on Indigenous Peoples’ political participation, a comprehensive synthesis of international trends remains limited. This study aims to systematically review Indigenous Peoples’ political participation and highlight key themes that shape their participation in governance and advocacy.

Methods: A systematic literature review was conducted following the PRISMA framework, analyzing 15 peer-reviewed articles that examine Indigenous Peoples’ political participation across different regions. Thematic analysis was employed to identify recurring patterns and key themes that characterize Indigenous political participation.

Results: Five primary themes emerged from the analysis: (1) land rights and political participation, which highlights the link between territorial claims and political participation; (2) indigenous governance and state relations, examining how Indigenous communities interact with governmental structures; (3) gender, identity, and political participation, addressing the unique challenges faced by Indigenous women; (4) digital activism and Indigenous mobilization, exploring the role of technology in fostering advocacy; and (5) environmental governance and climate justice, connecting Indigenous rights to broader ecological concerns.

Discussion: The findings contribute to the existing knowledge base by bridging gaps in the literature and offering insights into the structural challenges and opportunities for Indigenous political participation. This study underscores the need for more inclusive decision-making processes that recognize Indigenous rights and advocate for equitable representation. Future research should further explore the intersection of Indigenous political agency with digital activism, gender dynamics, and climate justice to inform policy frameworks that support Indigenous self-determination.

1 Introduction

Democracy flourishes when individuals are proactively involved in political activities, which serves as the fundamental for national governance. Ostrom (2000) emphasized the significance of individuals’ continuous political participation, such as affiliating with political parties, voting, or participating in advocacy groups, civic organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), to sustain democracy (Deth, 1997; Ostrom, 2000). Nevertheless, political participation is required to be accessible to guarantee all citizens possess equal chances to determine relevant policy-making initiatives and implementation and convey collective opinions to policymakers (Schlozman et al., 2012). Conventionally, political participation is defined as a series of individuals’ demeanors to shape governmental outcomes and policy-making decisions directly or indirectly (Verba et al., 1978), which encompass campaigning, advocacy, and voting (Milbrath and Goel, 1977). The definition has recently been expanded to electoral activities and political party participation, whereas unconventional participation encapsulates civil resistance, demonstrations, and online activism (Dalton and Welzel, 2014). Political participation reinforces governmental accountability, representation, and responsiveness in ensuring democratic governance. Nonetheless, political participation is not necessarily open for all citizens, especially Indigenous Peoples worldwide, who continue to be substantially neglected in their respective rights and underrepresented in formal political institutions. The status as a minority group and structural barriers, such as limited electoral representation, ambiguous legal status, insufficient channels for meaningful communications, and low awareness of political participatory means, impede Indigenous Peoples’ political participation (Dabin et al., 2019; Arrese, 2020; Tomaselli, 2020), on top of low accessibility to education, systemic discrimination, and economic marginalization (Usek and Dunlop, 2023).

The present study seeks to explore the contemporary forms of political participation among Indigenous Peoples, with a particular focus on contributing factors, prevailing challenges, and contextual dynamics that shape their participation by conducting a systematic literature review (SLR) guided by the following research question: What are the global trends in Indigenous Peoples’ political participation? To date, no comprehensive SLR has explicitly focused on this topic. While one existing review has examined trends and challenges in political science research related to Indigenous politics and policy, its scope was limited to publications from 2019 to 2023 and did not adhere to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol (Soares, 2024). In light of this gap, the current study offers a novel and methodologically rigorous contribution by systematically analyzing international scholarship on Indigenous political participation. This review aims to provide a nuanced understanding of participation patterns and inform academic audiences and policymakers about the current global landscape of Indigenous political participation.

Particularly, 15 peer-reviewed studies were scrutinized by adhering to the PRISMA framework to guarantee a rigorous analysis. A total of five emerging themes were discovered, namely land rights and political participation, Indigenous People governance and state relations, gender and identity in political participation, online activism and Indigenous People mobilization, and environmental governance and climate justice. The first theme examined how territorial sovereignty and legal recognition contributed to Indigenous People’s political agency while the second theme appraised how Indigenous People navigated national and global political structures. The third theme evaluated the intersectionality between Indigenous People political participation and leadership, whereas the following theme analyzed the higher usage of social media and online channels for political advocacy and civic disobedience. The final theme scrutinized Indigenous People’s political advocacy toward climate change challenges and policy-making decisions. Simultaneously, several existing literature gaps were addressed, including limited intersectional research on the diversity of Indigenous communities, methodological shortcomings in comparative research, and limited theorization of online political participation. Accordingly, this study integrated existing empirical evidence across various geopolitical settings and assisted in providing a more holistic comprehension by performing comparative techniques to pinpoint both facilitators and barriers to Indigenous People’s political participation and governance. Theoretically, intersectional feminism, digital resistance, political ecology, and decolonialism were also investigated to formulate a more nuanced conceptual model. Methodological improvements in thematic analysis beyond descriptive analysis were also elucidated to appraise systemic power dynamics and emerging trends in Indigenous People’s political participation. The detailed methodology is delineated in the following section by explaining the inclusion criteria of selected articles for the SLR before performing both descriptive and thematic analyses in the third section. The fourth section elucidates the implications of existing empirical evidence, followed by the fifth section summarizing the current SLR with potential future directions. Several study limitations are also underscored for future scholars evaluating similar topics. Resultantly, the present study offered valuable insights into the continual discourse on Indigenous People political representation, self-determination, and future inclusion into the democratic governance structure.

2 Methodology

This study applied PRISMA by searching for relevant past studies in online research databases as the initial phase before identifying relevant articles, screening selected studies, assessing eligibility, and synthesizing existing empirical evidence.

2.1 Identification

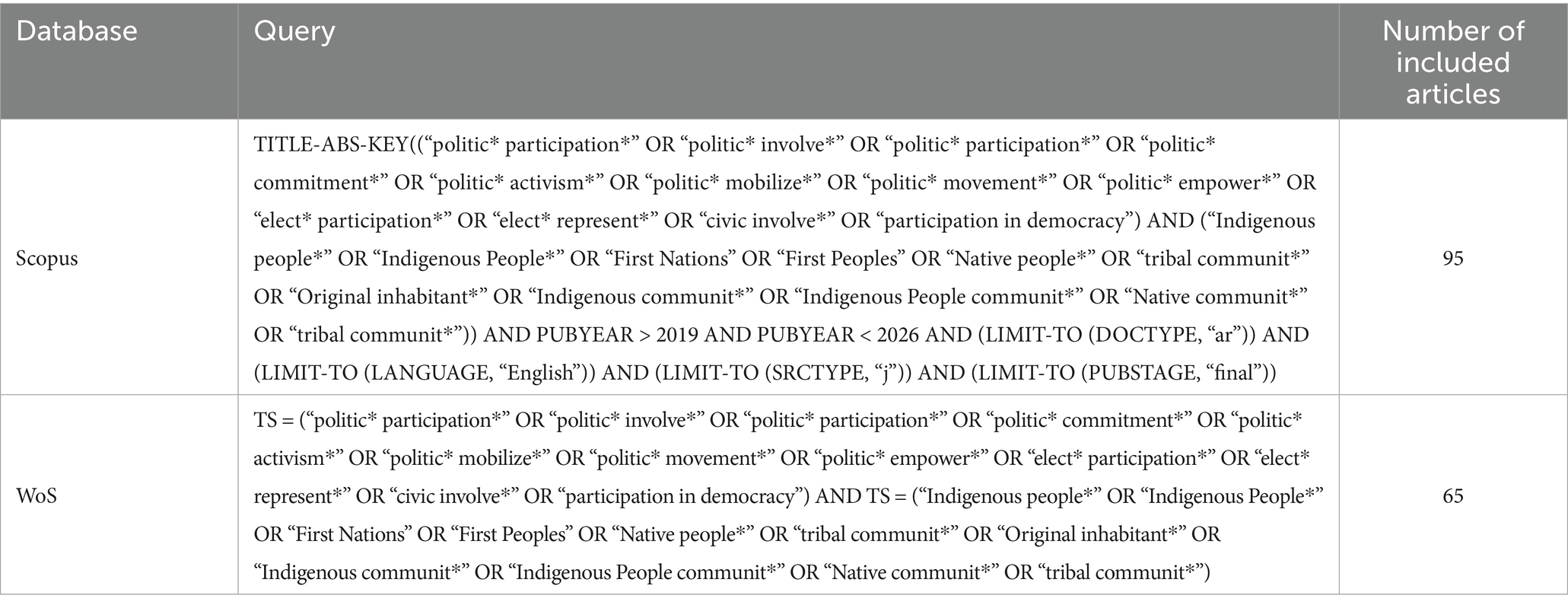

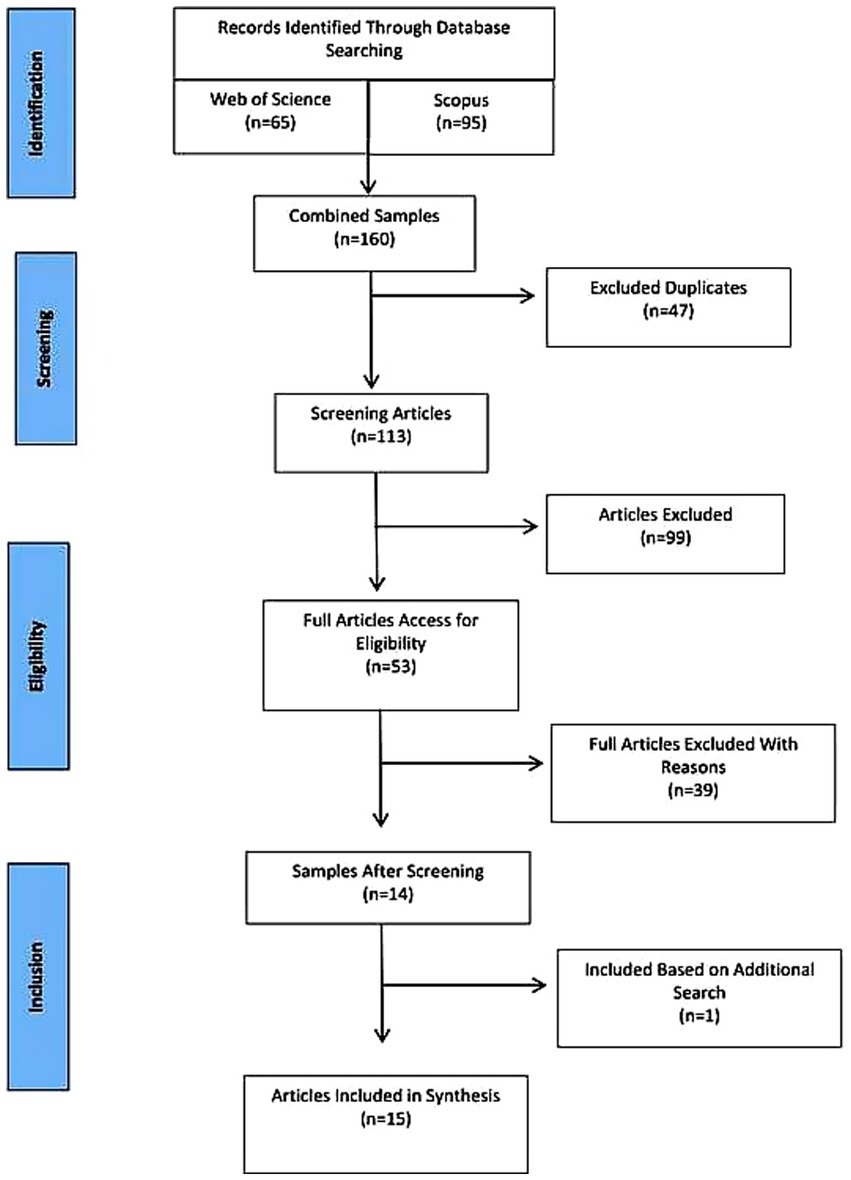

A structured search technique was established according to the RQ (Shafril et al., 2021). Specifically, keywords, including Indigenous Peoples and political participation, were defined before being extended to synonyms and similar concepts, such as tribes, political mobilization, political participation, and Indigenous communities. A holistic search was also guaranteed by systematically integrating the keywords via advanced search techniques, namely phrase searching, truncation, wildcards, field code functions, and Boolean operators (Shafril et al., 2021). The literature search was performed on the three major databases, namely Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus, which were highly acknowledged for extensive records of academic publications in the discipline of social sciences (Vieira and Gomes, 2009). WoS encapsulated over 28,000 articles across diverse academic domains, whereas Scopus comprised over 22,000 studies from over 5,000 global journals. Google Scholar was also employed to acquire articles not available on the two databases as mentioned above. Furthermore, cultural differences in the terminology of depicting Indigenous Peoples and country-specific terms were considered, including Indigenous Peoples and Torres Strait Islanders for Australia and Adivasi and Scheduled Tribes for India, to guarantee diversity and inclusivity (Xiao and Watson, 2017). The process was performed between November 2024 and December 2024, producing 160 articles for screening (Table 1).

2.2 Screening

Screening functioned to remove identified articles irrelevant to the RQ or not fulfilling the inclusion criteria. A total of 47 duplicate articles were eliminated before the preliminary screening to review study abstracts and determine the relevance degree to the RQ. Resultantly, 99 articles were excluded. A more refined process was subsequently conducted by perusing the titles and abstracts based on the RQ, which finalized 53 studies for further action.

2.3 Assessing eligibility

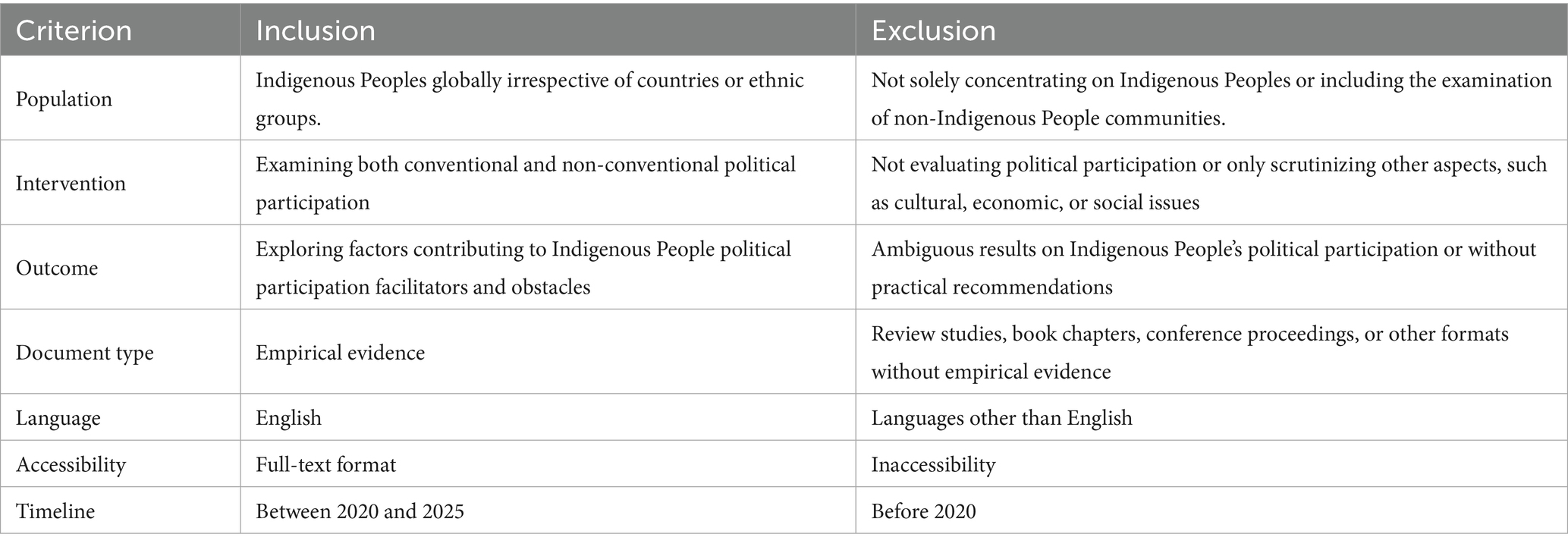

The procedure included two phases (Xiao and Watson, 2017). Preliminary screening scrutinized the abstracts to determine initial relevance to the RQ before a more holistic quality appraisal by perusing the entire articles for detailed content assessment. The process guaranteed reproducibility, transparency, and cross-verification by recording excluded articles (Kitchenham, 2007, as cited in Xiao and Watson, 2017). Both inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined according to the RQ to guarantee the sole focus on Indigenous People’s political participation. Hence, only 14 articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria, with an additional study from Google Scholar included. The inclusion of only 15 articles in this SLR resulted from a rigorous and methodologically sound screening process designed to ensure both thematic relevance and empirical quality. An initial search across three major academic databases, WoS, Scopus, and Google Scholar generated a broad pool of studies. However, numerous articles were excluded due to poor methodological quality, duplication, unavailability of full texts, non-English language, or lack of direct relevance to Indigenous Peoples’ political participation. To minimize selection bias and enhance reliability, clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied at multiple screening stages, with all decisions documented and cross-verified. The decision to include only studies published between 2020 and 2025 aimed to capture the most contemporary global trends and recent developments in Indigenous political participation, particularly in light of increasing global attention to Indigenous rights, decolonization movements, and digital activism. While the limited number of studies may influence the breadth of generalization, this was a deliberate methodological choice to maintain analytical rigor by synthesizing only the most recent, empirically robust, and thematically relevant literature (Table 2).

2.4 Synthesis

Both descriptive and thematic analyses were conducted on the final 15 articles (Tranfield et al., 2003). Descriptive analysis was performed in Excel to classify the articles according to the country, publication year, concept, study design, empirical evidence, and recommendations for future directions, which offered a structured overview of the study profiles and trends regarding geographical and methodological patterns. Thematic analysis in this study followed Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework, employing a deductive approach to identify themes that directly addressed the research questions (Braun and Clarke, 2006). While thematic analysis is often linked to qualitative and narrative data, this review also incorporated quantitative studies that included sufficient textual elements, such as open-ended survey responses, that could be meaningfully coded. In the first phase, the author acquainted themselves with the content by thoroughly reading and re-reading the selected studies to develop a deep understanding of the data. During the second phase, initial codes were generated manually through a systematic review of the texts. These codes were subsequently used to identify broader patterns in the third phase. The fourth phase involved reviewing and refining the emerging themes to ensure internal consistency and conceptual clarity, including identifying relevant sub-themes. In the fifth phase, each theme was clearly defined and appropriately labeled. Finally, the themes were assessed for relevance and coherence in addressing the key research questions in the sixth phase. Throughout the entire process, the coding structure and interpretation of themes were continuously refined to maintain analytical rigor and ensure consistency across both qualitative and quantitative data sources (Figure 1).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive analysis

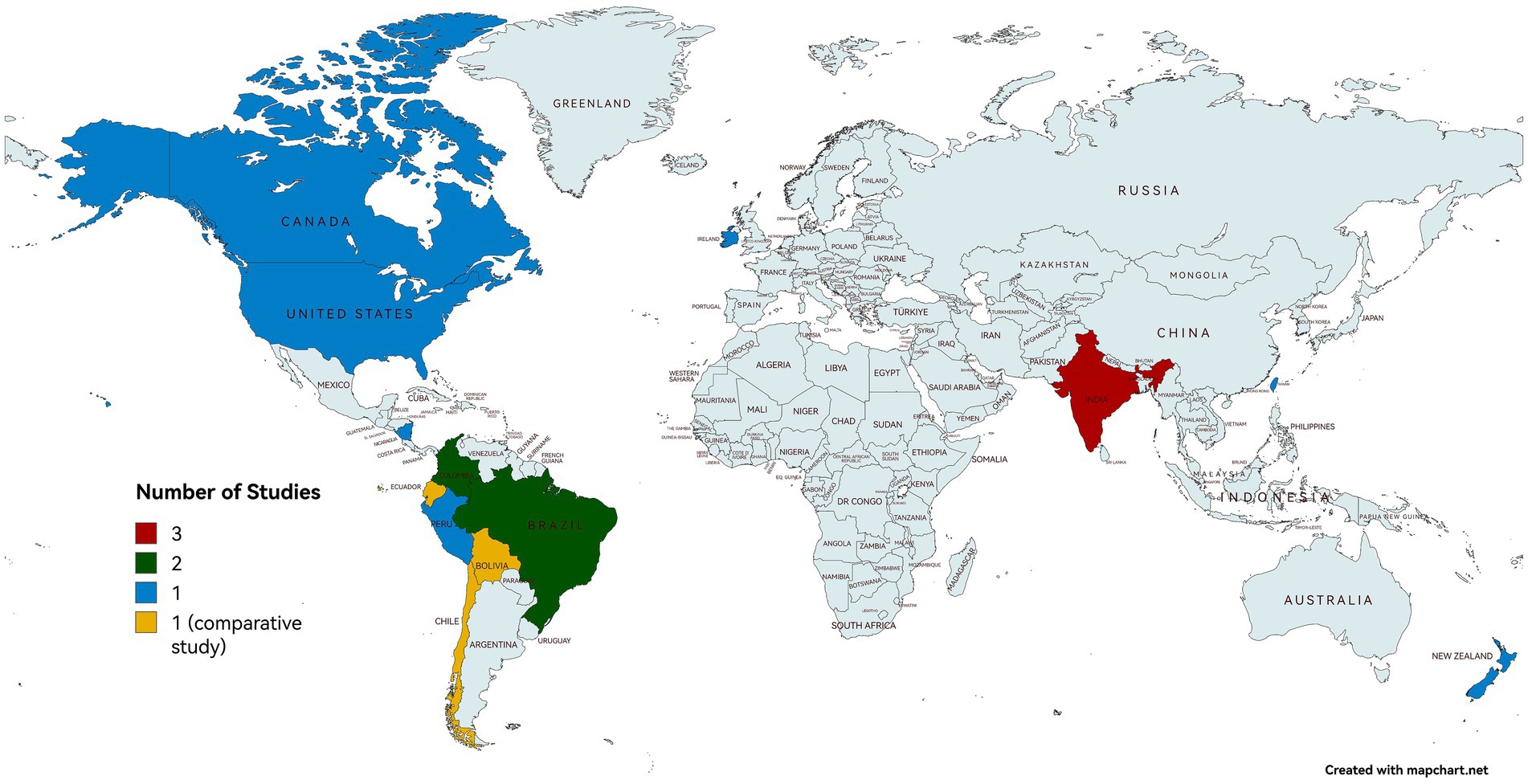

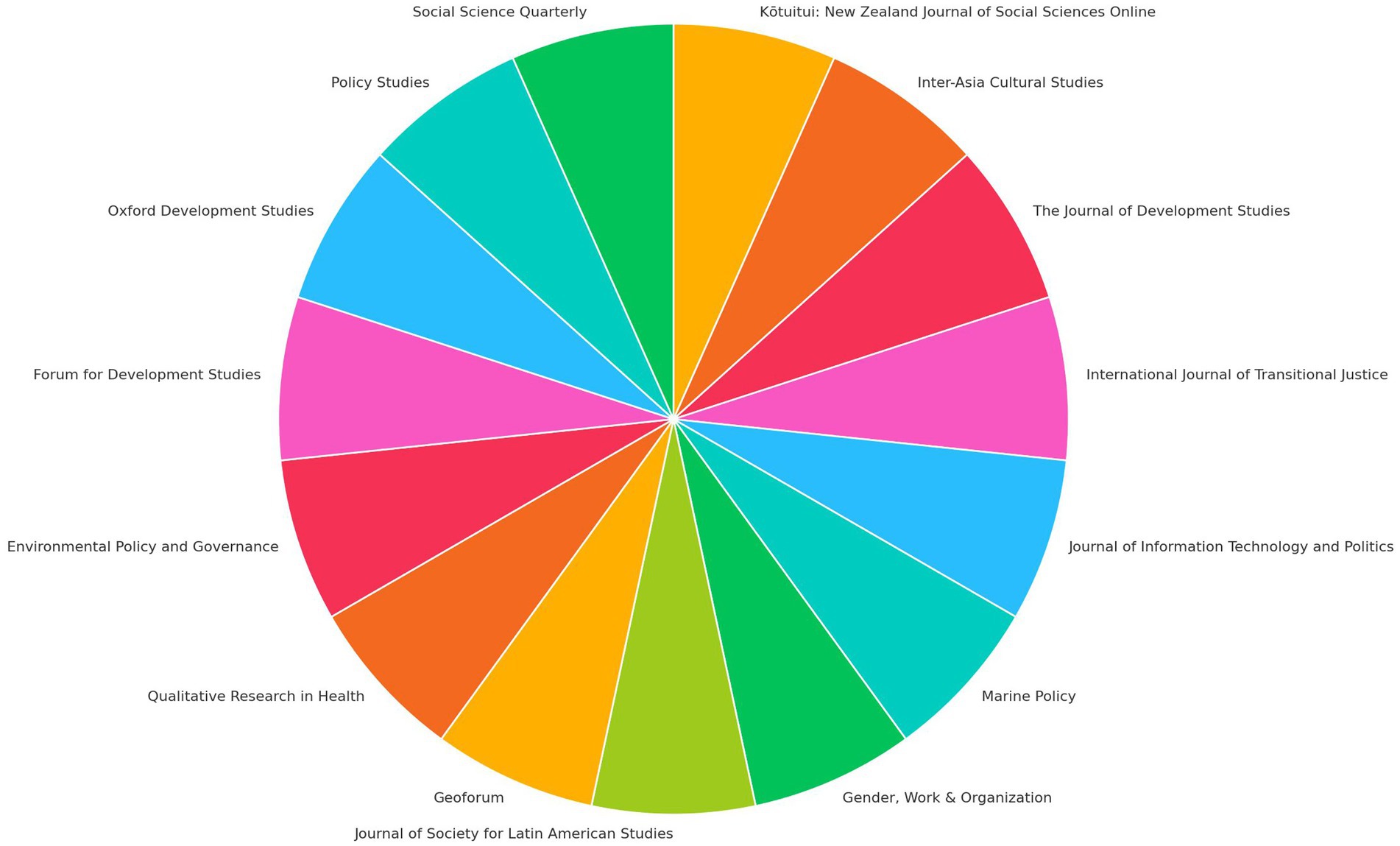

The 15 articles demonstrated high variations in the geographical focus, publication year, and journal distribution. Particularly, four studies were published in 2024, followed by three in 2020, 2022, and 2023, respectively, and two in 2021, which reflected increasing academic traction in Indigenous People’s political participation and relevant topics in recent years. All 15 articles were conducted in 11 different nations, which highlighted the international relevance of the current topic. A total of three articles concentrated on India, followed by two in Brazil and Colombia, respectively, and one in New Zealand, the United States of America (USA), Taiwan, Canada, Nicaragua, Ireland, and Peru, respectively. In addition, an article was a comparative study focusing on Indigenous People’s political dynamics in three Latin American nations, namely Bolivia, Chile, and Ecuador. The geographical variation indicated diverse sociopolitical settings of how Indigenous Peoples navigated political participation, governance, and policy frameworks. The 15 studies were published in 15 journals respectively, with each encompassing a wide range of interdisciplinary topics. The journals encapsulated the Journal of Information Technology and Politics, Journal of Society for Latin American Studies, Social Science Quarterly, Journal of Development Studies, Forum for Development Studies, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, Policy Studies, International Journal of Transnational Justice, Marine Policy, Gender, Work, and Organization, Geoforum, Qualitative Research in Health, Environmental Policy and Governance, Oxford Development Studies, and the Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. The wide range of publication journals posited that Indigenous People’s political participation was popular across various fields, such as gender studies, development studies, environmental policy, political science, and transnational justice. Summarily, the descriptive results served as a robust foundation for thematic and comparative analyses (Figures 2–4).

3.2 Thematic analysis

Indigenous communities globally participate in various political activities to navigate intricate relationships with diverse legal frameworks, state institutions, and governance structures. The existing studies not only underscore the challenges for ensuring sufficient Indigenous People’s representation, land rights, and environmental justice but also the agency, resilience, and innovation in asserting sovereignty. The five key themes derived from 15 articles indicated the multidimensional aspect of Indigenous People’s political participation and the continuous endeavors to resolve marginalization issues while fostering self-determination.

3.2.1 Theme 1: land rights and political participation

Land is not only a pivotal resource but also a fundamental of Indigenous People’s identity, culture, and political agency. Prior scholars revealed that secure land tenure promoted higher political participation as Indigenous communities with recognized land rights tended to participate in electoral processes and policy advocacy efforts (Nandwani, 2023). The enactment of the Forest Rights Act in India elevated political participation among Scheduled Tribes affiliated with respective political parties to advocate for and protect Indigenous People’s rights (Nandwani, 2023). Vega et al. (2022) also delineated how automatic demarcation actions in the Brazilian Amazon, especially how riverine communities physically specified respective land borders, served as a politically resistant against state encroachment and corporate exploitation. Nonetheless, land recognition does not frequently lead to political participation, particularly when Indigenous communities become more politically mobilized owing to frustration with unfulfilled promises related to land rights (Raj and V, 2024). For instance, Kaingang Indigenous farmers in Brazil expressed significant grievances over land distribution that spurred collective political actions, which emphasized how political participation could originate from both aspiration and disillusionment (Barbosa et al., 2022). Summarily, land rights issues were highly interweaved with political participation when Indigenous communities navigated formal political institutions while asserting sovereignty.

3.2.2 Theme 2: indigenous peoples governance and state relations

Indigenous People’s political participation is determined by how Indigenous communities participate with national governance systems. Traditionally, Indigenous Peoples have been deprived of personal rights by state institutions, although policy negotiations, legal battles, and electoral participation have enabled certain Indigenous community to advance their political rights. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Nicaragua has played an integral function in legitimizing Indigenous People’s land rights, which has allowed higher political agency in national governance systems (Koper, 2021). Moreover, Māori electoral roll choices indicated specific political identity and historical experiences with state power, with factors, including cultural attachment and grievances over colonization contributing to voter registration decisions (Greaves et al., 2023). Nonetheless, state relations are frequently symbolized by power asymmetries, which necessitates Indigenous People to formulate both formal and informal political approaches. Indigenous People’s organizations in Peru have collaborated within the governance of Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) to advocate for rights in environmental policymaking (Lozano et al., 2023). While participation in state-led environmental governance can extend the influence of Indigenous People, navigating bureaucratic and hierarchical power structures is frequently ineffective in fully integrating Indigenous People’s perspectives to ensure full autonomy while rejecting co-optation (Fan and Sung, 2020).

3.2.3 Theme 3: gender, identity, and political representation

The interweaving between Indigenous People, gender, and political participation is a vital aspect of Indigenous People’s political participation. Particularly, Indigenous females have frequently experienced specific obstacles to political participation owing to marginalization persisting from colonialism and gender discrimination. Previous academicians highlighted the significance of gender-specific methods to improve Indigenous People’s political participation, such as determining feminist participatory actions in Colombia through the Truth Commission to incorporate female opinions into post-conflict justice procedures (Santamaría et al., 2020). Travelers mothers, who were an Indigenous in Ireland, resolved additional layers of exclusion by striking an equilibrium between ethnic identity, maternal responsibilities, and political ambition amidst the prevalence of male- and white-dominated political settings (Cullen, 2024). Additionally, Indigenous females in rural Colombia elucidated how food security was directly associated with autonomy and broader socio-political participation, which underscored the requirement for comprehensive methods for Indigenous female rights incorporating political, economic, and cultural aspects (Sinclair et al., 2022). The results strengthened the notion that Indigenous People’s political participation could not entirely be comprehended without accounting for Indigenous females’ gender-specific and systemic barriers, which should be effectively resolved to attain inclusive political participation.

3.2.4 Theme 4: online activism and indigenous people’s mobilization

The advancements in digital technologies have offered various instruments for Indigenous People to be involved in multiple political activities despite the emergence of different state repression and control issues (Tank et al., 2024). Specifically, Indigenous People’s political participation in Latin America has demonstrated a growing trend of social media usage for storytelling and digital mobilization to advocate for respective Indigenous People’s rights (Lupien et al., 2021). Nonetheless, online environments are not frequently secure when governments can capitalize on censorship, surveillance technologies, and libel laws to oppress Indigenous People. Online political activities have significantly impacted Native American’s electoral processes in the USA, which has elevated voter participation across Indigenous Peoples. While digital technologies have offered channels for Indigenous People’s self-representation and civic disobedience online, that they have also been exposed to alternative suppression forms from governments in a more digitalized political environment (Schroedel et al., 2020).

3.2.5 Theme 5: environmental governance and climate justice

Indigenous Peoples are the vanguard of climate justice movements to advocate for land and ecosystem protection while countering environmental exploitation. Past academicians discovered that Indigenous Peoples’ participation in environmental governance required political agency beyond electoral processes to effectively integrate legislation, activism, and global support (Snook et al., 2022). Indigenous People organizations in Peru engaged in REDD+ to enhance recognition of Indigenous People’s knowledge in climate policy-making processes (Lozano et al., 2023). Indigenous Peoples in Brazil also withstood agricultural business expansion, which was a significant challenge for ecological survival and land sovereignty and demonstrated the intricate junction between Indigenous People’s political participation and environmental justice (Barbosa et al., 2022). Thus, Indigenous People have not only countered exploitative businesses but also developed different sustainable governance frameworks based on ancestral knowledge and ecological stewardship.

4 Discussion

Indigenous People’s political activities are dynamic and evolving due to the involvement of protests, electoral processes, environmental advocacy, and online activism. The present SLR highlighted Indigenous People’s political participation with governmental institutions was limited owing to existing bureaucracy, systemic discrimination, and persisting colonial legacies despite growing recognition in both legal and political frameworks. Data synthesis demonstrated effective approaches to resolve the aforementioned political obstacles that significantly impeded comprehensive political inclusion, which produced wider implications and identified gaps in existing governance systems to fully incorporate Indigenous People’s sovereignty and self-determination. Particularly, land rights were a pivotal factor contributing to Indigenous People’s political participation as formal land tenure drove higher participation in electoral and governance procedures (Nandwani, 2023). Nonetheless, land recognition is not synonymous with political empowerment as Indigenous People frequently encounter barriers in government-led bureaucracy emphasizing economic development over Indigenous People’s sovereignty (Raj and V, 2024). For instance, legal land recognition did not effectively resolve conflicts over resource control of the Kaingang in Brazil as the recognition heightened collective mobilization due to unfulfilled promises (Barbosa et al., 2022). Therefore, land recognition might also result in co-opting Indigenous People’s protests within existing governance models.

Prior scholars revealed that political participation within existing governance systems aggravated instead of mitigating persisting power asymmetries. For example, REDD+ in Peru continued to be restrained by top-down decision-making approaches emphasizing market-based conservation frameworks over Indigenous People’s ecological governance despite securing political representation (Lozano et al., 2023). Similarly, Indigenous Peoples’s political representation continued to be symbolic instead of substantive despite being involved in the electoral process. Māori voter registration in New Zealand indicated persisting historical grievances without leading to higher political influences within current governmental frameworks (Greaves et al., 2023). Resultantly, Indigenous People’s marginalization persisted within existing governance models despite higher political recognition and representation. Furthermore, the intricate relationship between identity, gender, and political participation deteriorated Indigenous Peoples’ political participation, especially among females who were required to counter additional layers of exclusion emerging from persisting colonial power structures and gender-specific discrimination. Santamaría et al. (2020) demonstrated how gender-specific interventions were integral to resolving political violence and achieving justice among Indigenous females involved in the Colombian Truth Commission. Nevertheless, structural obstacles, including institutional biases and racialized maternal expectations, persisted with significant influences on political development among Irish Indigenous women (Cullen, 2024). Therefore, further endeavors are necessary to counter existing patriarchal power structures.

Online activism provided both opportunities and limitations in Indigenous People’s political activities. Particularly, social networking sites and online channels have served as effective instruments to mobilize civic disobedience and protests, record unjust treatments, and challenge prevalent narratives (Lupien et al., 2021; Tank et al., 2024). Latin American Indigenous activists have capitalized on digital technologies to circumvent conventional media censorship to advocate for land rights. Nevertheless, digital technologies can also expose Indigenous activists to online harassment, governmental surveillance, and algorithmic suppression, which restrain the capability to mobilize without risks (Lupien et al., 2021). Online activism also necessitates access to digital technologies, which is low among indigenous peoples in remote areas. Therefore, more Indigenous People-specific digital infrastructures and more effective protections against online suppression should be provided to guarantee that online activism functions as a secure and feasible channel for political activities. While Indigenous Peoples are internationally acknowledged as the vanguards of biodiversity and climate justice movements, existing environmental governance models continuously comprise colonial power systems and structures. The REDD+ in Peru demonstrated restricted decision-making power over land and resources despite Indigenous Peoples being allowed to participate in climate policy (Lozano et al., 2023). Indigenous People’s countermeasures to agricultural business expansion and deforestation in Brazil were perceived as an environmental issue rather than a political movement for self-determination (Barbosa et al., 2022). Hence, Indigenous Peoples’ climate governance could not be decolonized without acknowledging Indigenous Peoples’ sovereignty as pivotal to environmental decision-making instead of an advisory or secondary concern.

5 Conclusion

The current study systemically reviewed current international trends in Indigenous People’s political participation and underscored the emerging opportunities and persistent barriers. While Indigenous Peoples are participate in political activities via traditional and alternative methods, the participation rate remains low owing to the presence of systemic obstacles in terms of electoral discrimination, legal exclusion, and socioeconomic marginalization. Numerous countries continue to implement policies constraining Indigenous People participation in governance frameworks, although the recognition of Indigenous People rights in global forums demonstrates a growing trend. While certain Indigenous communities successfully mobilized for political inclusion, relevant endeavors varied across geographical locations and political environments. The advocacy for land sovereignty continued to be one of the most politically significant issues that spurred electoral and political participation. In addition, the interconnection between Indigenous Peoples’ governance and governmental institutions continually exhibited significant tension when governments continuously regarded Indigenous Peoples’ self-determination as a threat to national sovereignty instead of an expansion of existing democratic governance structures. The intersectionality between identity, gender, and socioeconomic status also significantly shaped Indigenous People’s political agency, wherein Indigenous females experienced exacerbated obstacles to political participation, which underscored the importance of inclusivity for diverse Indigenous People’s experiences. Summarily, significant systemic and epistemological challenges persist despite higher recognition of Indigenous People political participation in both scholarly and policymaking discourses. Indigenous People are required to strive for more meaningful representation via civic movements, governmental institutions, or online advocacy. Future researchers, activists, and policymakers should collaborate to effectively remove existing systemic challenges to facilitate inclusive governance and Indigenous People’s political agency, which can assist in developing a more just and equitable political landscape for Indigenous Peoples across the globe.

6 Study limitations and future directions

Several study limitations exist owing to the sole focus on Indigenous People’s political participation through governmental models without incorporating Indigenous People-specific governance structures and conventional political systems. Future academicians can appraise how Indigenous Peoples define and exert political influences beyond electoral processes and legal recognition. Moreover, existing empirical evidence on gender and intersectionality is limited due to minimal concentration on Indigenous LGBTQ+ communities. Intersectional research can be conducted more by future scholars to offer a more holistic comprehension of how several identity symbols determine Indigenous People’s political agency. Regional bias may also be present as most studies were performed in North America, Latin America, and Oceania, whereas investigations on Indigenous Peoples political movements in Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Arctic are limited. Future scholars can expand geographical representation to integrate a wider range of Indigenous People’s political experiences. In addition, online activism related to algorithmic oppression, governmental surveillance, and the role of AI in contributing to Indigenous Peoples discourse is an emerging topic to pinpoint both risks and opportunities of online mobilization when emphasizing Indigenous People-led digital infrastructure. Meanwhile, an integrated methodology with digital ethnography, participatory action research, and Indigenous Peoples oral traditions can be implemented to acquire enriched and comparative insights. Existing studies only advocate for Indigenous People’s political participation within governmental institutions without evaluating the challenges posed by such inclusion toward systemic power systems. Future academicians can extend the current study topic to Indigenous People-led governance frameworks, land-back movements, structural transformation, and transnational Indigenous People political networks to discover effective methods of self-determination. A further limitation of this review is its narrow scope, as it synthesized findings from only 15 articles due to the application of strict quality standards, issues with duplication, language barriers, and the unavailability of full texts from other potentially relevant sources. While such criteria enhance the rigor of the review, they also restrict the comprehensiveness of the synthesis. Therefore, future research should aim to expand the evidence base by incorporating a wider range of diverse and interdisciplinary literature.

Author contributions

BR: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. KA: Writing – review & editing. SD: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This article was supported by the TAP Fund (code RE-2024-004) of the Institute of Ethnic Studies, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Arrese, D. (2020). The right of political participation of indigenous peoples and the UN declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. Max Planck Yearbook Unit. Nat. Law Online 23, 109–144. doi: 10.1163/18757413_023001005

Barbosa, D., Oderich, E., and Camana, A. (2022). Kaingang indigenous, family farmers and soy in southern Brazil: new old conflicts over land. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 50, 30–43. doi: 10.1080/13600818.2021.1956446

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cullen, P. (2024). Minoritized mother politicians in Ireland: subjectivities and subjectivation in the political workplace. Gend. Work. Organ. 32, 389–407. doi: 10.1111/gwao.13159

Dabin, S., Daoust, J. F., and Papillon, M. (2019). Indigenous peoples and affinity voting in Canada. Can. J. Polit. Sci. 52, 39–53. doi: 10.1017/S0008423918000574

Dalton, R. J., and Welzel, C. (Eds.) (2014). The civic culture transformed: From allegiant to assertive citizens : Cambridge University Press.

Deth, J. W. V. (1997). “Introduction: social involvement and democratic politics” in Private groups and public life: Social participation, voluntary associations and political involvement in representative democracies (London: Routledge).

Fan, M.-F., and Sung, S.-C. (2020). Indigenous political participation in the deliberative systems: the long-term care service controversy in Taiwan. Policy Stud. 43, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/01442872.2020.1760233

Greaves, L. M., Hayward, J., Barnett, D., Crengle, S., and Clark, T. C. (2023). The predictors of Māori electoral roll choice and knowledge: rangatahi Māori voter enrolment in a representative New Zealand youth survey. Kōtuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 18, 290–309. doi: 10.1080/1177083X.2022.2156356

Koper, N. (2021). The inter-American court of human rights and indigenous rights in Nicaragua: from land to empowerment? Soc. Latin Am. Stud. 41, 608–624. doi: 10.1111/blar.13286

Kitchenham, B. (2007). Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering (EBSE Technical Report, EBSE-2007-01). Keele University and University of Durham.

Lozano, L., Pugley, D. D., Luna, S., Broeck, P. V. D., and Parra, C. (2023). Challenging state authority and hierarchical power: a casestudy of the engagement of Peru's Amazonian IndigenousPeoples' organizations in the governance of REDD+. Environ. Policy Gov. 34, 1–15. doi: 10.1002/eet.2067

Lupien, P., Chiriboga, G., and Machaca, S. (2021). Indigenous movements, ICTs and the state Latin America. J. Inform. Tech. Polit. 18, 387–400. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2021.1887039

Milbrath, L. W., and Goel, M. L. (1977). Political participation: How and why do people get involved in politics? USA: University Press of America.

Nandwani, B. (2023). Land rights recognition and political participation: evidence from India. J. Dev. Stud. 59, 1741–1759. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2023.2235107

Ostrom, E. (2000). Collective action and the evolution of social norms. J. Econ. Perspect. 14, 137–158. doi: 10.1257/jep.14.3.137

Raj, N., and V, A. (2024). Empowerment of tribal women in India: impact of the Forest rights act 2006. Forum Dev. Stud. 1–20. doi: 10.1080/08039410.2024.2432302

Santamaría, A., Muelas, D., Caceres, P., Kuetguaje, W., and Villegas, J. (2020). Decolonial sketches and intercultural approaches to truth: corporeal experiences and testimonies of indigenous women in Colombia. Int. J. Trans. Just. 14, 56–79. doi: 10.1093/ijtj/ijz034

Schlozman, K. L., Verba, S., and Brady, H. E. (2012). The Unheavenly chorus: Unequal political voice and the broken promise of American democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Schroedel, J., Berg, A., Dietrich, J., and Rodriguez, J. M. (2020). Political trust and native American electoral participation: an analysis of survey data from Nevada and South Dakota. Soc. Sci. Q. 101, 1885–1904. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12840

Shafril, H. A. M., Samah, A. A., and Kamarudin, S. (2021). Speaking of the devil: a systematic literature review on community preparedness for earthquakes. Nat. Hazards 108, 2393–2419. doi: 10.1007/s11069-021-04797-4

Sinclair, K., Thompson-Colon, T., Bastidas-Granja, A. M., Matamoros, S. E. D. C., Olaya, E., and Melgar-Quinonez, H. (2022). Women's autonomy and food security: connecting the dots from the perspective of indigenous women in rural Colombia. SSM 2, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100078

Snook, J., Cunsolo, A., Ford, J., Furgal, C., Jones-Bitton, A., and Harper, S. (2022). “Just because you have a land claim, that doesn’t mean everything’s going to fall in place”: an Inuit social struggle for fishery access and well-being. Mar. Policy 140, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105071

Soares, L. B. (2024). Mapping trends and challenges in political science research in indigenous policy and politics (2019-2023). Int. Political Sci. Abs. 74, 561–574. doi: 10.1177/00208345241275166

Tank, N., Gundala, U., and Mohanty, S. (2024). Tribal mobilization for religious identity and political space: ongoing demand for inclusion of Sarna-tribal religion in the census of India. Inter-Asia Cult. Stud. 25, 856–873. doi: 10.1080/14649373.2024.2389722

Tomaselli, A. (2020). Political participation, the international labour organization, and indigenous peoples: convention 169 ‘participatory’ rights. Int. J. Hum. Rights 24, 127–143. doi: 10.1080/13642987.2019.1677612

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., and Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manage. 14, 207–222. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.00375

Usek, V. S., and Dunlop, L. (2023). Indigenous youth activism: the role of education in creating capabilities. J. Youth Stud. 28, 281–298. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2023.2261865

Vega, A., Fraser, J., Torres, M., and Loures, R. (2022). Those who live like us: autodemarcations and the co-becoming of indigenous and beiradeiros on the upper Tapajós River, Brazilian Amazonia. Geoforum 129, 39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.01.003

Verba, S., Nie, N. H., and Kim, J.-O. (1978). Participation and political equality: a seven-nation comparison. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Vieira, E. S., and Gomes, J. A. N. F. (2009). A comparison of Scopus and web of science for a typical university. Scientometrics 81, 587–600. doi: 10.1007/s11192-009-2178-0

Keywords: indigenous peoples, political participation, democracy, systematic literature review, PRISMA

Citation: Rathakrishnan B, Aboo Talib Khalid K and Daud S (2025) A systematic literature review on the international trends of indigenous peoples’ political participation. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1601300. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1601300

Edited by:

Sivamurugan Pandian, University of Science Malaysia (USM), MalaysiaReviewed by:

Paramjit Singh Jamir Singh, University of Science Malaysia (USM), MalaysiaZaheruddin Othman, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia

Copyright © 2025 Rathakrishnan, Aboo Talib Khalid and Daud. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Banupriya Rathakrishnan, cDExNzYzMkBzaXN3YS51a20uZWR1Lm15

†ORCID: Kartini Aboo Talib Khalid, orcid.org/0000-0002-1702-0601

Sity Daud, orcid.org/0000-0002-4980-7783

Banupriya Rathakrishnan

Banupriya Rathakrishnan Kartini Aboo Talib Khalid1,2†

Kartini Aboo Talib Khalid1,2†