- 1Taizhou Institute of Administration, Taizhou, China

- 2Communication University of Zhejiang, Hangzhou, China

An effective measure to enhance the overall deliberative capacity of society is to promote large-scale deliberation by constructing and improving a deliberative system. Based on Dryzek's theory of deliberative system and the practical experience of Chinese grassroots deliberation, this paper conducts a configuration analysis of the influencing factors and their configuration paths of 30 cases' deliberative capacity. The results show that: all components of the deliberative system have important effects on the deliberative capacity, but no single component constitutes the necessary condition for high deliberative capacity; there are three configuration paths that give rise to high deliberative capacity, which can be divided into two types: government-single-driven type and government-society-dual-driven type. Deliberative systems with different maturity can obtain high deliberative capacity as long as they adopt the correct configuration paths; The influence of the components of a deliberative system on deliberative capacity will change with the variations of maturity of the deliberative system.

Problem presentation

As the role of deliberative democracy in social governance becomes increasingly prominent, enhancing one's own deliberative capacity has become the goal of every modern democratic society. There are many factors restricting the improvement of deliberative capacity, and the narrow scope of deliberation is undoubtedly one of the most important reasons, which stems from the structural contradiction inherent in deliberative democracy between mass participation and niche dialogue. The theory of deliberative system, the latest theoretical achievement in the research and practice of deliberative democracy, offers an effective solution to this contradiction. It advocates the division of labor and integration of various scattered and isolated elements of deliberation with systematic thinking, thus promoting the development of large-scale deliberation and realizing the overall improvement of social deliberative capacity.

Deliberative capacity enhancement has always been an important topic in the theoretical research of deliberative democracy. After reviewing the literature, it can be seen that the academic research on deliberative capacity mainly follows three approaches: first, the research approach of deliberative subjects, which focuses on the deliberative capacity of individuals, organizations, and groups as deliberative subjects. For example, Lundell analyzed the concept, determinants, and measurement dimensions of individual deliberative capacity (Krister, 2014); Carlo et al. outlined a deliberative model of intraparty democracy, proposing that strengthening deliberation within political parties can enhance their capacity to coordinate between society and the state (Invernizzi-Accetti and Wolkenstein, 2017). Wang explored the constituent elements, characteristics, and enhancement paths of the deliberative capacity of participatory parties in the context of Chinese politics (Wei, 2016); Sun explored the elements, characteristics, and improvement paths of deliberative capacity of social organizations (Fafeng, 2019). Second, the research approach of deliberative platforms, which focuses on the deliberative capacity of specific deliberative organizations, institutions or networks as deliberative platforms or channels. Schouten et al. used the concept of deliberative capacity to analyze and evaluate a specific type of roundtable meeting for multi-stakeholder governance (Schouten et al., 2012); Suiter et al. confirmed the potential of minipublics to enhance the deliberative capacity of citizens (Suiter et al., 2020). Milewicz and Goodin analyzed the deliberative capacity of international institutions; (Milewicz and Goodin, 2016). Gu et al. explored the problems and improvement suggestions for the construction of the deliberative capacity of the CPPCC (Jianjun et al., 2016); Third, the research approach of deliberative systems, a new approach focusing on the deliberative capacity of a certain political system, which has been continuously expanded due to the emergence of the theory of deliberative system. Dryzek proposed an analytical framework for deliberative systems, and on this basis, he clearly defined the deliberative capacity (Dryzek, 2009a); Curato used Dryzek's analytical framework to evaluate the deliberative capacity of the Philippine political system (Curato, 2015); Tang proposed an analytical framework for deliberative capacity analysis, including social capacity, institutional capacity, and participatory capacity, based on the background of Chinese deliberative democracy practices (Tang, 2014); Que believes that the deliberative capacity of a nation can be defined in terms of credibility, inclusiveness, and indirectness of the deliberative structure (Tianshu, 2010).

The theory of deliberative system not only expands the research approaches of deliberative capacity, but also raises questions and challenges to some existing researches. These challenges are manifested in three aspects: first, some conclusions of the research approaches of deliberative subjects and deliberative platforms are subject to scrutiny and testing by the research approach of deliberative system. For example, some deliberative mechanisms considered exemplary respectively, have been found to be detrimental to the system's deliberative capacity, whereas some flawed deliberative mechanisms have been found to promote overall deliberative capacity (Parkinson and Mansbridge, 2013). Moreover, some new basic theoretical issues remain to be answered. For example, the interactions between different components of the deliberative system, as well as the specific mechanisms by which these components affect the system's deliberative capacity, need further research. Finally, the importance of country-specific researches has been raised to a new level. The deliberative systems of different countries have both commonalities and individualities. Both the construction of the deliberative system and the enhancement of the system's deliberative capacity must be based on the political institutional background and practical experience of the country.

The Chinese government has always attached great importance to the systematic development of deliberative democracy, and various explorations and practices around the construction of deliberative democracy systems are in full swing across the country. While accumulating many successful experiences, China has also encountered a variety of problems and difficulties. Thus, China's practices can provide a lot of valuable empirical materials for the theoretical research of deliberative system. Given this, based on the grassroots practices of deliberative democracy in China, this article attempts to use the analytical framework of deliberative system to analyze the influencing factors and mechanisms of the deliberative capacity in the context of China's political system, with a view to exploring the following main issues: 1. What components of the deliberative system can affect deliberative capacity significantly? 2. What are the specific mechanisms by which these components affect deliberative capacity? 3. What are the practical forms of constructing the deliberative system? Answers to these questions can provide some useful insights and suggestions for the researches of deliberative system theory and the practices of enhancing deliberative capacity in various nations.

Theory and hypotheses

Analytical framework

The constituent elements of a deliberative system are an important aspect of deliberative system theory. Several scholars have defined the constituent elements of deliberative systems from different perspectives. In this regard, Zhang identified 8 different research perspectives (Dawei, 2020a,b). Among them, the most influential scholars are as follows: first, Mansbridge proposed four elements of a deliberative system from a functional perspective: binding decisions of the state (both in the law itself and its implementation); activities directly related to preparing for those binding decisions; informal talk related to those binding decisions; and arenas of formal or informal talk related to decisions on issues of common concern that are not intended for binding decisions by the state (Parkinson and Mansbridge, 2013). Secondly, Parkinson, from a procedural perspective, proposed 6 elements of a deliberative system: agents, sites, entities, transmission, translation, implementation (Parkinson, 2010). Finally, Dryzek, from a structural perspective, distinguished the constituent elements of a deliberative system into two main aspects: the deliberative spaces and the connections between these spaces. The former includes two elements: public space and empowered space, while the latter includes four elements: transmission, accountability, meta-deliberation and decisiveness (Dryzek, 2009b). These defining methods each have their own characteristics, advantages, and applicable analysis scenarios. Our study adopts Dryzek's analytical framework mainly for two reasons: first, this analytical framework is structural, focusing on internal structure and connections, which helps grasping the key elements and mechanisms of deliberative systems to better understand China's deliberative system. Although grassroots practices of deliberative systems exist in China, these practices are often unconscious or lack a clear concept and theory of deliberative systems (Dawei, 2020a,b). In the preliminary stage of deliberative system theory research, a structural analytical framework is the most suitable. In terms of China's practices, Mansbridge's functional analysis framework is too rough, which easily leads to overlooking some structural and substantive key elements. Parkinson's procedural analytical framework, on the other hand, is too detailed, and its improper operation can easily result in improper expansion of the deliberative system, incorrectly including elements that do not belong to deliberative systems. Finally, this analytical framework aligns well with China's practices of deliberative democracy. Unlike Mansbridge and Parkinson who closely link deliberation to free elections, Dryzek argues that the constituent elements of a deliberative system do not require any specific institution as a necessary condition. His analytical framework of deliberative systems is applicable to all types of political environments: authoritarian regimes, new and old democratic states, and governance that eludes states. Therefore, compared with the analytical frameworks of the former two, Dryzek's framework has broader applicability. Additionally, Zhang Dawei's analysis of the leading deliberative model in Tianchang City, China, reveals that this model not only demonstrates a high degree of consistency with the six elements of Dryzek's deliberative system but also shares significant similarities in characteristics (Dawei, 2020a,b). It is worth noting that Dryzek regards the state as the primary democratic actor and attaches full importance to empowered spaces, which is also highly consistent with China's practices of deliberative democracy. A fundamental feature of China's deliberative democracy is that the Party and the government play a leading or guiding role in deliberative practices.

Conditions and hypotheses

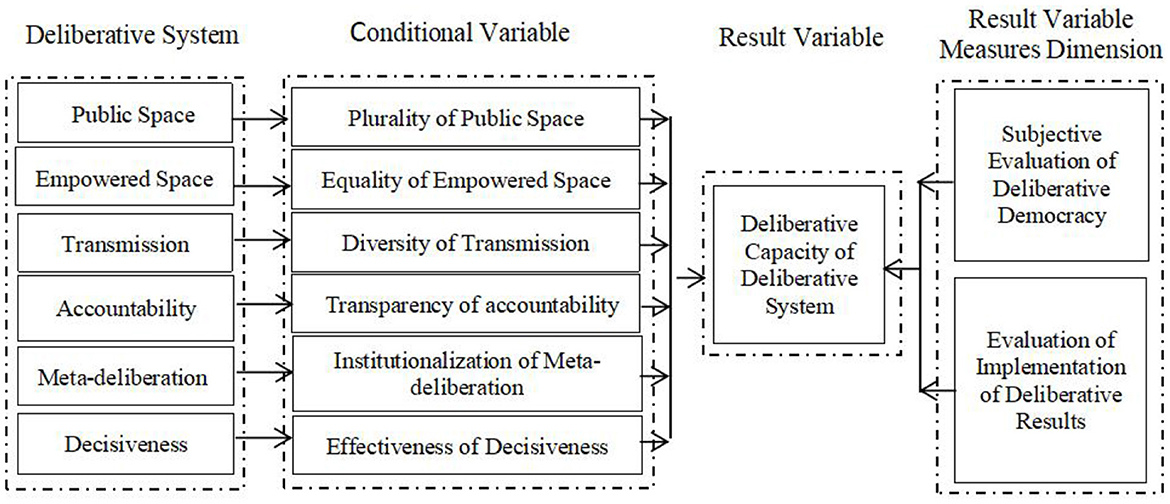

After determining Dryzek's deliberative system theory as the analytical framework for this study, it is necessary to operationalize the influencing factors of the six aspects of this deliberative system. Since these elements have rich connotations and attributes, it is crucial to identify core conditional variables to describe these elements effectively. Following the principle of Occam's Razor, which states that the fewer reasons used to explain a phenomenon, the closer the analysis gets to the core factors of causality, this study aims to limit the explanatory antecedents to a minimum to ensure the feasibility and scientific validity of the research. To this end, based on an extensive review of relevant literature, this study proposes one (six variables in total) conditional variable for each of the six influencing factors of the deliberative system. (Refer to Figure 1).

Plurality of Public space. Public space refers to a deliberative space with few restrictions on who can participate and what participants can say, where people can freely, widely, and truthfully express their views and ideas, including the media, social movements, activist associations, and physical locations (cafés, classrooms, and so on), the Internet, public hearings, and citizen-based forums of various sorts (Dryzek, 2009b). A crucial function of public space is to provide public opinion for public decision-making. Habermas believes that public opinion is formed through extensive, decentralized, and non-subjective communication activities, which spread throughout the public space and encompass all citizens (Huosheng and Zhihong, 2008). Young also holds that the deliberative process, in a complex large-scale society, must be understood as non-subjective and decentralized (Yang, 2013). Zhang and Yang view the public space as a network of interactions and communications among multiple actors (Chengfu and Chongqi, 2023). It can be seen that decentralized and diverse opinion expression is not only a basic feature of the public space but also an important prerequisite for the sound operation of deliberative democracy. Sunstein's research shows that when opinion narrowing or polarization occurs in the public space, the deliberative mechanism will fall into functional failure due to the lack of inclusive dialogue (Sunstein, 2001). Although there are significant differences in the operation logic between China's public space and that of the West, the full expression of multiple opinions in China's public space remains a necessary prerequisite for ensuring the healthy operation of China's grassroots deliberative democracy. Diverse opinion expression optimizes the structure of deliberative subjects, expands the dimensions of issues, and improves the quality of the process, ultimately enhancing the legitimacy and effectiveness of deliberative outcomes. In view of this, this study presumes that in the practice of China's grassroots deliberative democracy, the diversity of opinion expression in the public space is positively correlated with deliberative capabilities, and thus proposes the research hypothesis: the more pluralistic the public space, the greater the deliberative capacity of the political system.

Equality of Empowered space. Empowered space is where actors in collective decision-making institutions deliberate, transforming public opinion formed in the public space into legally binding laws and decisions (Dryzek, 2009b). Due to the inherent hierarchy and authority within collective decision-making institutions, deliberation within them are easily influenced by various inequalities among deliberative subjects in terms of identity, information, resources, and capabilities. These inequalities can have many negative effects on the deliberation, such as harming the interests of vulnerable groups and affecting the quality of public decisions. Song believes that in administrative deliberation, government departments' dominance over deliberation topics, procedures, and other arrangements often leads to unequal status between the government and the public, affecting the quality of deliberation (Xiongwei, 2016). Conversely, by improving and optimizing deliberation procedures and techniques, reducing these inequalities among deliberative participants, allowing vulnerable groups to express demands and opinions freely and truthfully without being constrained by hierarchy and authority, the effectiveness of deliberation will be significantly enhanced. Qi et al. found that when grassroots residents can access to real information related to governance issues and have effective opportunities for equal expression and influence over decision-making during deliberations with grassroots governments, decision-making errors can be largely avoided, and public acceptance of decisions can be increased (Zilong et al., 2021). It can be seen that in the political context of China, ensuring the deliberative equality of the empowered space is of great significance for the deliberative subjects to engage in real deliberation and the deliberation organizer to improve the effectiveness of deliberation. Therefore, the research hypothesis is proposed: the more equal the empowered space is, the greater the deliberative capacity of the political system is.

Diversity of Transmission. Transmission refers to the means and mechanisms through which public space influences empowered space including various forms such as voting, social movements, and personal contacts (Dryzek, 2009b). Transmission can link different deliberative spaces and sites, facilitate the circulation of discourse and ideas among these spaces and sites, and play a crucial role in the effective operation of the entire deliberative system. “A deliberative system is more democratic if it can foster the transmission of claims and ideas across different sites” (Boswell et al., 2016). As deliberative spaces and sites are decentralized and diverse, a variety of transmission routes and mechanisms are needed to match them. Different scholars have discovered various transmission mechanisms. For example, Hendriks revealed the role of mini-publics (Carolyn, 2016), Mendonca focused on the importance of bureaucrats, media, and activists (Mendonça, 2016), Zhang and Zhao analyzed the guiding role of party organizations on discourse circulation in grassroots deliberation (Dawei and Yichen, 2021). Zhao stressed the role of the Internet in public decision-making and deliberation (Haiyan, 2019). It is these diverse transmission routes and mechanisms that together promote the efficient flow of discourse and ideas in the deliberative system. “Coupling mechanisms can also come in more institutional varieties where disconnected sites are formally linked” (Carolyn, 2016). Thus, the diversity of transmission is a fundamental characteristic of deliberative systems. The more diverse the routes, carriers, and mechanisms of transmission, the more efficiently discourse and ideas circulate among different deliberative spaces and sites, and the greater the democratic level of the deliberative system. Therefore, the research hypothesis is proposed: the greater the diversity of transmission mechanisms is, the greater the deliberative capacity of the political system is.

4. Transparency of Accountability. Accountability refers to the means and mechanisms through which empowered space is accountable to public space, including various forms such as elections, citizen assemblies, and media oversight. Also, accountability is essential for generating the legitimacy of collective outcomes (Dryzek, 2009b). For accountability, the transparency of means and information is crucial; it is the foundation of public political participation and a prerequisite for holding government departments and their members accountable. Hu and Liu believe that without timely, complete, and accurate public information, the public cannot effectively hold the government accountable (Chunyan and Bihua, 2016). Zheng and Meng believe that information disclosure is an important aspect of government accountability, as it helps people obtain high-quality information and promotes political participation (Siyao and Tianguang, 2022). Yang believes that information is a fundamental element for achieving government accountability; the severe problem of information asymmetry between government accountability subjects and objects seriously affects the precision, fairness, and effectiveness of government accountability (Nan, 2021). Therefore, this study emphasizes that the transparency of means and information is a fundamental aspect of accountability and a basic prerequisite for its effective operation. The more transparent the means and information are, the more effective the accountability is, and the more democratic the deliberative system is. Therefore, the research hypothesis is proposed: the more transparent the accountability is, the greater the deliberative capacity of the political system is.

5. Institutionalization of Meta-deliberation. Meta-Deliberation refers to the means and mechanisms by which the deliberative system conducts self-organization. It reflects the capacity of the deliberative system for self-reflection and self-reform, enabling the deliberative system to improve its own deliberative capacity over time (Dryzek and Niemeyer, 2010). In the political context of China, meta-deliberation mainly manifests in the party and government's continuous reflections on and improvements to the deliberative system. These reflections and improvements involve various aspects of deliberative activities, including innovation and optimization of deliberative platforms, standardization and improvement of deliberative procedures, evaluation and feedback of deliberative processes, and learning and training of deliberative knowledge and skills by deliberative participants. However, in reality, these reflections and improvements are often difficult to implement because they are not effectively institutionalized, and their implementations are often affected by the authority or even personal wills. Huntington believes that institutionalization is a process by which organizations or programs gain value and stability. The stronger an organization or program's adaptability, complexity, autonomy, and internal coordination are, the higher its level of institutionalization is (Huntington, 2008). Yue and Chen find that the higher the level of institutionalization of deliberative democracy is, the less likely it is for elite governance to degenerate into strongman rule (Jinglun and Yongxin, 2016). Therefore, this study considers the level of institutionalization as a key measure of meta-deliberation and believes that the higher the level of institutionalization of meta-deliberation is, the stronger the system's capacity for self-reflection and reform is, leading to greater deliberative capacity. Therefore, the research hypothesis is proposed: the higher the institutionalization level of meta-deliberation is, the greater the deliberative capacity of the political system is.

6. Effectiveness of Decisiveness. Decisiveness refers to the degree to which these five elements together determine the content of collective decisions, reflecting the effectiveness of the means and mechanisms by which deliberative outcomes influence collective decision-making (Dryzek, 2009b). From the current practices of grassroots deliberative democracy in China, decisiveness means and mechanisms mainly consist of two aspects: The first is the institutional aspect, which involves the institutions for accountability for the implementation of deliberative outcomes, exerting external rigid constraints on government departments to implement deliberative outcomes. The lack of these institutions leads to disconnection and discontinuity between deliberative outcomes and collective decisions. “The regulations on the operation of grassroots deliberative democracy in China are mainly reflected in documents issued by the party and government, in which there are no clear accountability provisions for the non-adoption or inadequate implementation of deliberative outcomes. This gives some grassroots officials great discretionary power in adopting and implementing deliberative outcomes, hindering the effective implementation of deliberative outcomes” (Yujia and Dengwen, 2022). The second is the conceptual aspect, which involves the correct understanding of deliberative democracy by government officials, creating an internal driving force for government officials to implement deliberative outcomes. In reality, many local government officials have a cognitive bias toward deliberative democracy. They obviously prefer deliberative democracy as a tool for “maintaining stability” and regard it as a tool for resolving social problems. At the same time, they tend to ignore the value of deliberative democracy in promoting fairness, justice, and equality, which affects the effectiveness of administrative deliberation and brings great obstacles to the sustainable development of deliberation (Xiaolin and Yiyun, 2017). In general, if the government departments of a deliberative system have established sound institutions of accountability for the implementation of deliberative outcomes, simultaneously, the government officials have a correct and comprehensive understanding of deliberative democracy, its decisiveness mechanisms will be practical and effective, leading to the deliberative outcomes having a substantial impact on collective decision-making. Therefore, the research hypothesis is proposed: the more effective the decisiveness mechanisms are, the greater the deliberative capacity of the political system is.

Analysis of limitations

Although Dryzek claims that his deliberative systems analysis framework can accommodate various types of political regimes, its theoretical presupposition still remains the binary separation between the government and society. The public space he presupposed is a diverse, open, and autonomous field, in which people can freely and independently express diverse viewpoints, and where the government and society have an equal and cooperative relationship in the deliberative process. This presupposition fundamentally contradicts China's political practices, where deliberative democracy is characterized by the government's deep embedding in society. This embedding is not only reflected in the operational rules of the public space—where public opinion must be expressed orderly within the institutional framework established by the government, but also in the construction of various deliberative mechanisms—the government, through its strong institutional capacity, builds deliberative mechanisms from the top down, including not only its own meta-deliberation and decisiveness mechanisms but also transmission and accountability mechanisms that link the public space with the authorized space. From this, it can be seen that when applying Dryzek's deliberative systems theory to analyze China's deliberative practice, one cannot merely make simple “formal analogies” and remain at the surface level of analyzing the influence of each element of the deliberative system on the deliberative capacity. Otherwise, it is impossible to truly understand the power structure and operational logic of China's deliberative system. Take transmission as an example: while both Western and Chinese transmission mechanisms play important roles in promoting deliberative democracy, they have fundamentally different power bases. The former is rooted in media independence and interest group competition, exhibiting characteristics of diversity and competitiveness, whereas the latter relies on government power, emphasizing the government's integration and guidance of public opinion. Therefore, the interpretation of the elements of China's deliberative system should be based on the background of China's political system and the logic of power operation behind it.

Research method, case selection, and variables

Research methods

FsQCA is a mature configuration comparison analysis technique. It can analyze not only small and medium-sized sample data but also large sample data. Additionally, it has the dual advantages of both qualitative and quantitative analysis due to its ability to convert data into continuous fuzzy membership scores. This study chooses QCA as the research method for several reasons: firstly, due to the limited number of sample cases involved, it is not suitable for large-sample quantitative analysis. Besides, it aims to go beyond the limitations of individual case analysis and reveal causal regularities with a certain degree of universality. Secondly, QCA is a case-oriented and context-sensitive analysis method that requires a rich understanding of cases and ongoing dialogue between theory and cases. By using QCA for analysis, this study can deepen its understanding of cases while better localizing external theories in China. Lastly, QCA can effectively address the causal complexity of the social phenomena faced in this study. Given the close relationships between the constituent elements of deliberative systems, these elements often do not act independently but act through combinations of elements to influence deliberative capacity. Compared with traditional statistical techniques, which focus on analyzing the marginal effects of independent variables on dependent variables, QCA is more in line with the needs of this study, well analyzing the relationship between conditional combinations and outcome variables as well as the relationship between conditional variables.

Case selection

The selection of cases in QCA must follow certain principles. Cases are not randomly selected but chosen based on research questions, theoretical foundations, and practical needs. “case selection by itself is a process guided by the underlying research question and the preliminary hypotheses one may have in this respect” (Rihoux and Ragin, 2012). The familiarity of the researcher with the cases, the researcher's language skills, and the accessibility of data are all crucial for the correct application of QCA. Secondly, it is essential to ensure the sufficient homogeneity and maximum heterogeneity of the universe of cases, which can be achieved by adding some restrictions to the selection of cases. Both cases with “positive” outcomes and cases with “negative” outcomes should be selected. Lastly, the ratio of the number of cases to the number of conditions should be appropriate to avoid the “limited diversity problem,” where observed data are far less rich than the potential property space delineated by the conditions.

This study takes the deliberative system of town (sub-district) level in Taizhou City as the research object. This is because Taizhou has always been one of the most active areas in the practice of grassroots deliberative democracy in China, and it has explored and implemented various forms of deliberative democracy, including financial budget deliberation, industrial wage deliberation, public decision deliberation. Taizhou's practice of deliberative democracy not only provides a feasible path to cultivate the new growth of deliberative democracy in China, but also offers good empirical materials for the theoretical study of deliberative democracy. It should be noted that to enhance the feasibility of the study, the scope of deliberative activities addressed herein is confined to all deliberative activities conducted by town (sub-district) governments, with deliberative activities carried out by village and community organizations explicitly excluded from the research scope. Based on the above case selection principles, this study has selected a total of 30 towns (sub-districts) as research cases. Most of these cases exhibit good similarity in economic scale and population size to achieve the highest degree of homogeneity, while also including cases with significantly smaller economic and population scales to ensure maximum heterogeneity. Additionally, these cases include both those with high deliberative capacity and those with low deliberative capacity. Finally, the number of cases matches the number of conditions. “A common practice in an intermediate-N analysis (say, 10 to 40 cases) would be to select from 4 to 6 conditions” (Rihoux and Ragin, 2012).

Measurement and calibration of variables

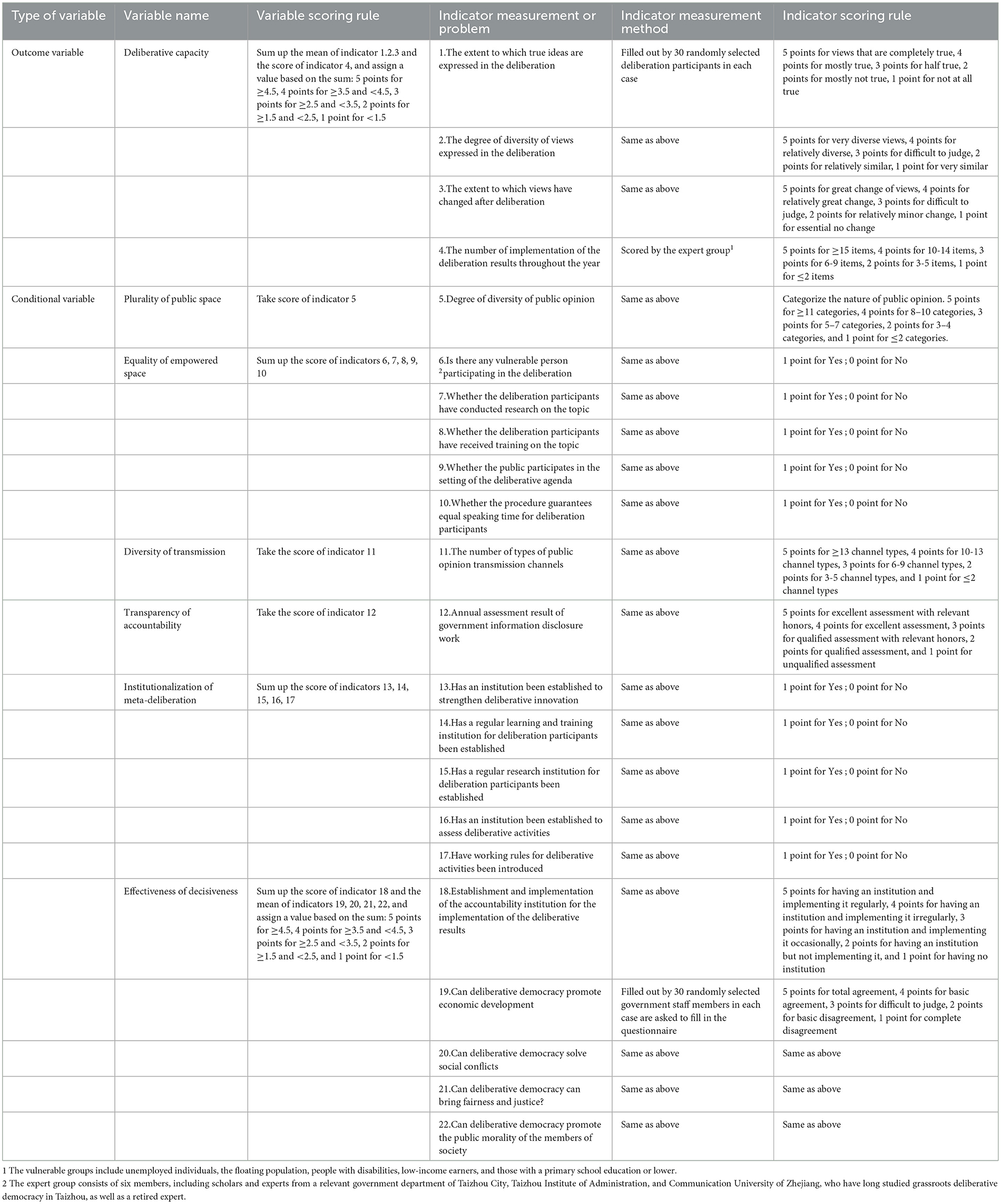

The outcome variable of this study is the deliberative capacity of the deliberative system. Dryzek defines deliberative capacity as the extent to which a political system possesses structures to host authentic, inclusive, and consequential deliberation. Authenticity refers to the feature of deliberation, that it must induce reflection non-coercively, connect claims to more general principles, and exhibit reciprocity. Inclusiveness means that interests and discourses present in a political setting are extensive and diverse. Decisiveness refers to the significant impact of deliberation outcomes on collective decisions (John, 2009). Milewicz and Goodin believe that assessing the deliberative capacities of a political system require considering two elements. The first relates to the capacity for high-quality deliberation to occur. The second relates to the capacity for that deliberation to have effects outside of itself (Milewicz and Goodin, 2016). Combining the views of these scholars, this study believes that understanding deliberative capacity requires grasping two dimensions: a value dimension, where deliberations must be authentic, inclusive, and interactive, reflecting democratic values; and a result dimension, where deliberations must be effective, with deliberation outcomes significantly impacting collective decisions or being effectively implemented (Refer to Figure 1). Therefore, the measurement of deliberative capacity includes two dimensions: one is to measure the subjective evaluation of deliberative democracy by the deliberative participants in the empowered space deliberations; the other is to evaluate the implementation of the deliberation results. The measurement methods and scoring rules of these two dimensions are shown in Table 1. The study includes six conditional variables: plurality of public space, equality of empowered space, diversity of transmission, transparency of accountability, institutionalization of meta-deliberation, and effectiveness of decisiveness. The measurement methods and scoring rules for these variables are also detailed in Table 1.

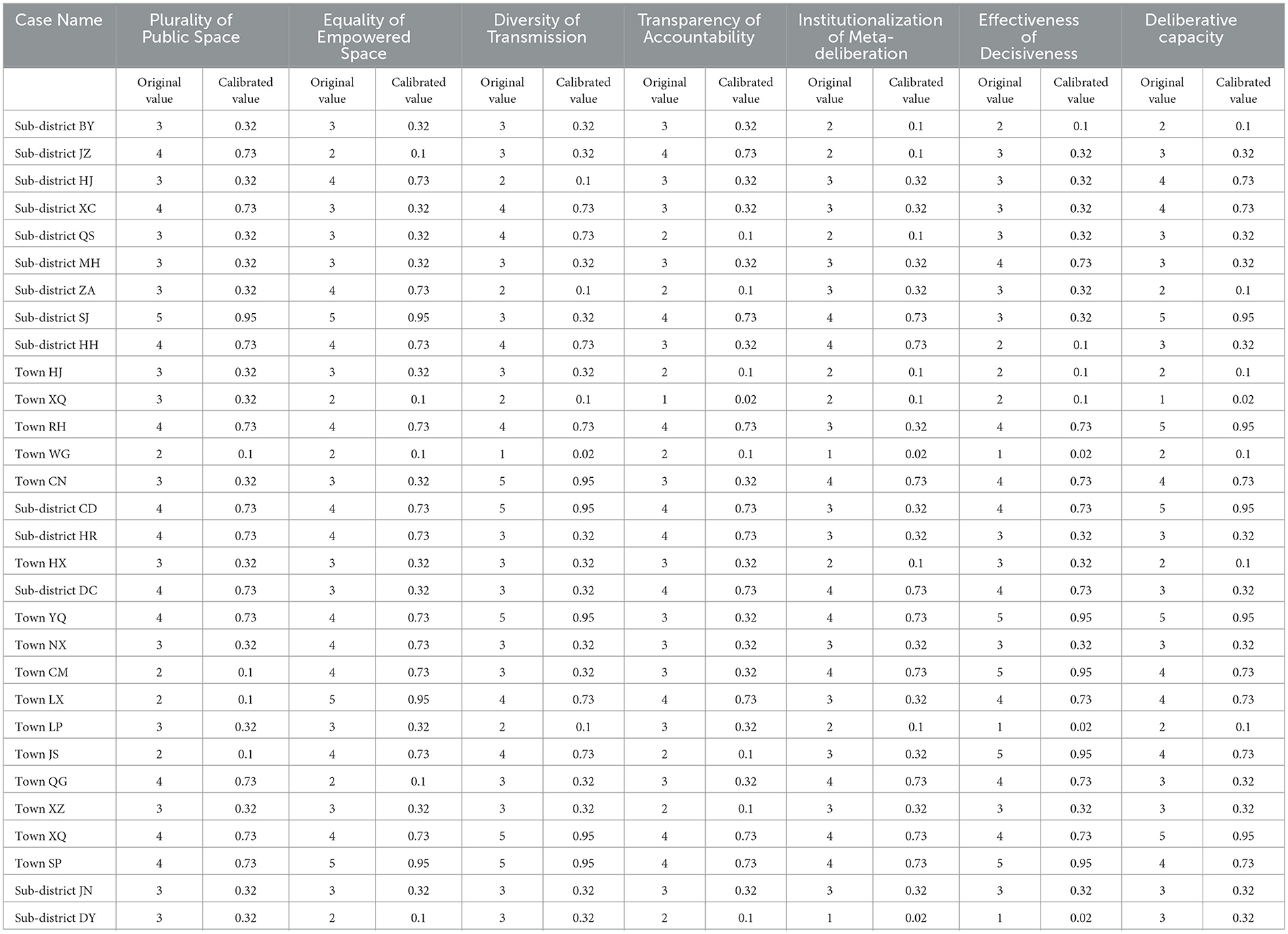

After assigning values to all variables, the study needs to calibrate their initial scores into fuzzy set membership scores. This study uses direct calibration, setting the original scores of 5, 3.5, and 1.5 as full membership threshold (1), crossover point (0.5), and full non-membership threshold (0) respectively, and then uses the FSQCA software to calibrate all initial scores into fuzzy set membership scores. The closer the calibrated value is to 1, the higher the degree to which the case belongs to the relevant set; the closer it is to 0, the lower the degree of belonging; 0.5 indicates the most ambiguous belonging of the case. The calibration results for all variables are shown in Table 2.

Analysis and results

Univariate necessary condition analysis

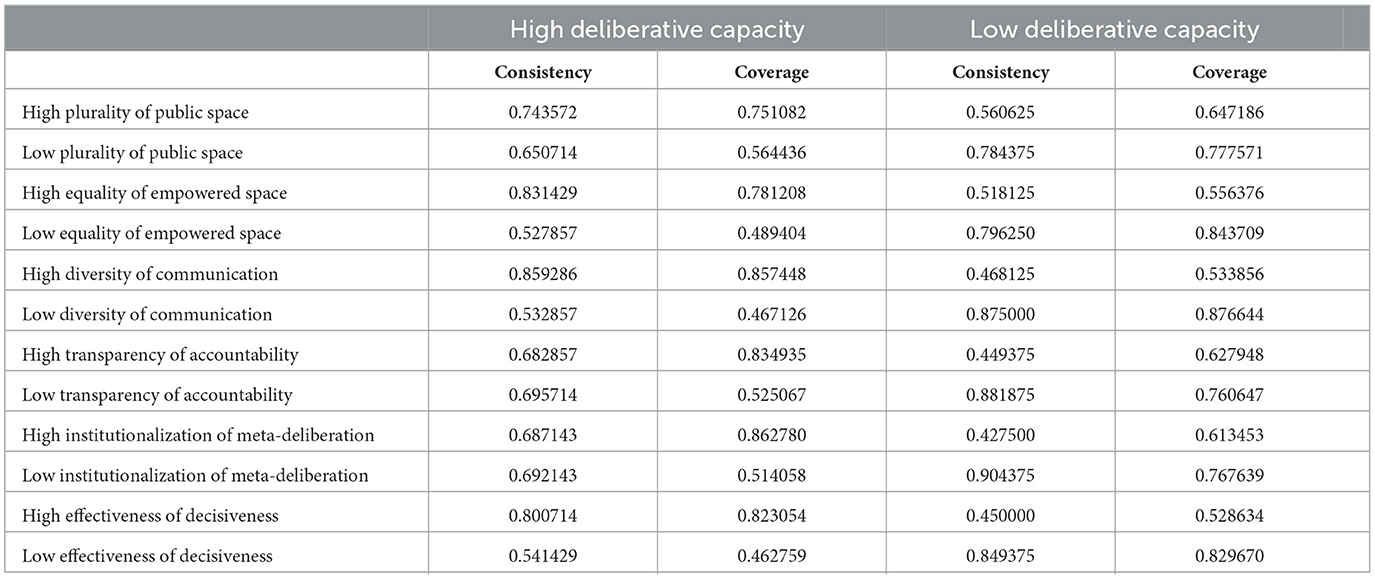

Before conducting configurational analysis using QCA, it is generally necessary to perform a necessary condition analysis on each antecedent condition. In fuzzy set analysis, necessary conditions are considered as supersets of result variables, which can be evaluated through two indicators: consistency and coverage of the fuzzy subset relationship. By using FSQCA software to perform necessary condition analysis on all condition variables (including logical negations) and the result variables (including logical negation), this study obtained the results shown in Table 3. It can be observed that for the result variable “high deliberative capacity”, the consistency of all individual condition variables (including logical negations) is less than 0.9. This indicates that these condition variables are not necessary conditions for the result variable “high deliberative capacity”, requiring further sufficient condition analysis on these combinations of condition variables. For the result variable “low deliberative capacity”, only the consistency of “low institutionalization of meta-deliberation” is greater than 0.9, indicating it can be considered as a necessary condition for “low deliberative capacity.” This implies that if a deliberative system has low deliberative capacity, then its institutionalization of meta-mechanism is also low, which is consistent with the researchers' findings in this study during field research.

Sufficient condition configuration analysis

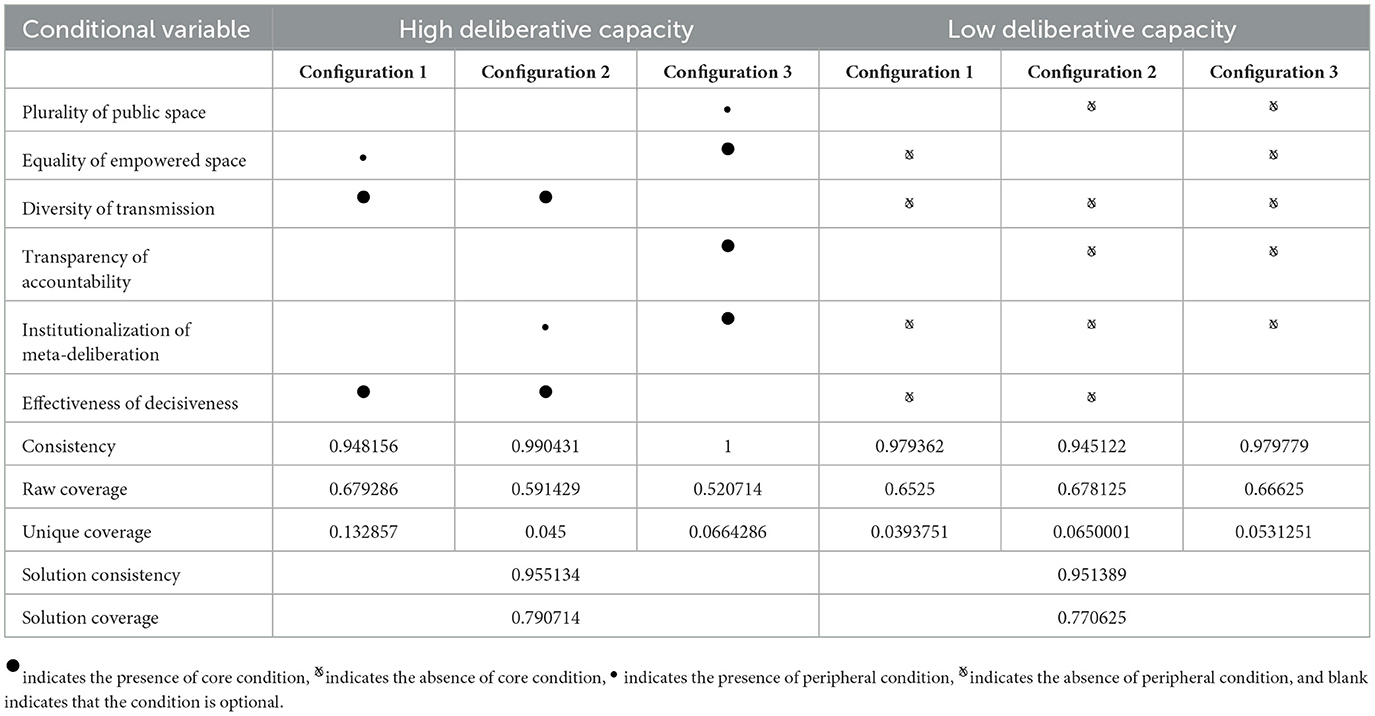

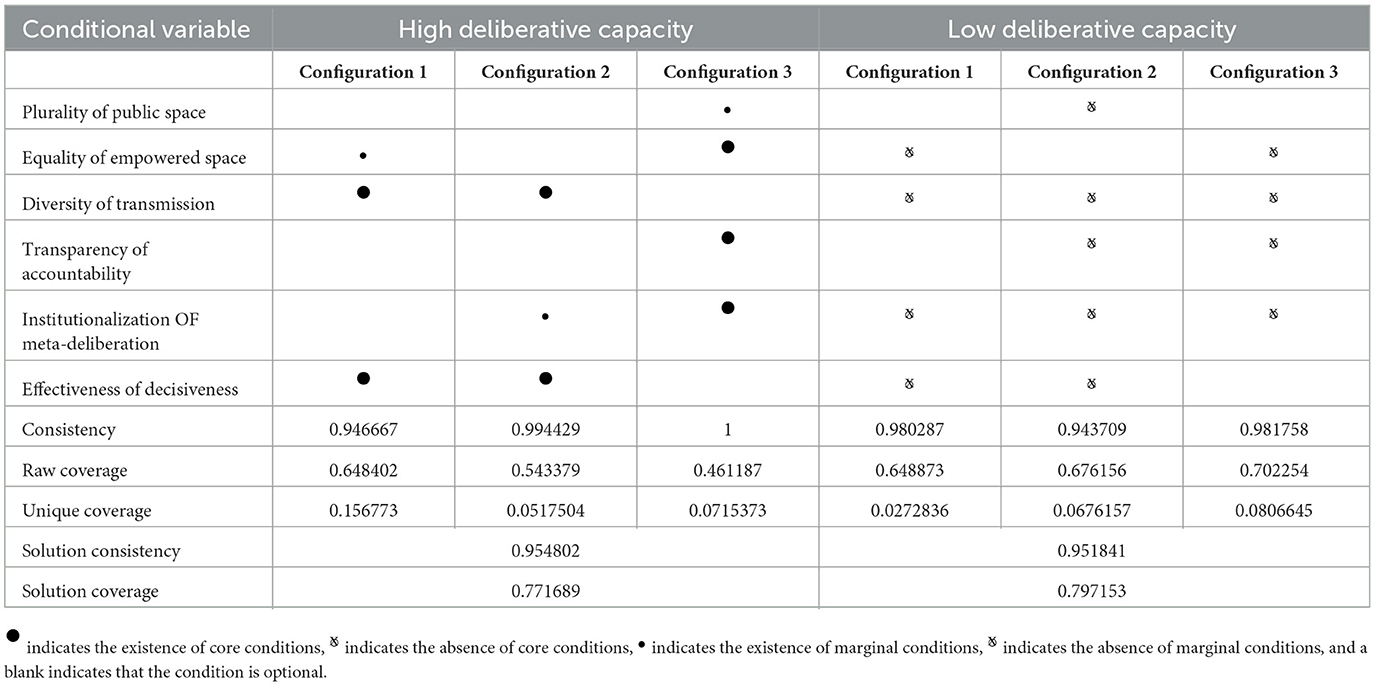

After performing necessary condition analysis on the condition variables, it is necessary to further conduct sufficient condition analysis on individual condition or combinations of conditions. In fuzzy set analysis, sufficient conditions are considered as subsets of the result variables, which can be evaluated through two indicators: consistency and coverage indicators of the fuzzy subset relationship. This study first utilized FSQCA software to conduct configurational analysis on high deliberative capacity. The empirical case frequency threshold was set at 1, the consistency threshold at 0.85, and the PRI consistency threshold at 0.75 to avoid simultaneous subset relationships. In the “standard analyses”, the combinations “high plurality of public space * high equality of empowered space * high diversity of transmission * high transparency of accountability * high effectiveness of decisiveness “and” high equality of empowered space * high transparency of accountability * high institutionalization of meta-deliberation ” were considered as prime implicants. The analysis yielded three solutions through counterfactual analysis: complex solution (excluding logical remainders), intermediate solution (including partial logical remainders), and parsimonious solution (including all logical remainders). Among these, complex solutions have case orientation but lack theoretical applicability, parsimonious solutions have theoretical applicability but lack realistic rationality, and only intermediate solutions have both theoretical applicability and realistic rationality, so they are frequently adopted by most researchers. Subsequently, the study conducted configurational analysis on low deliberative capacity with similar threshold settings. This study presents the intermediate solution and distinguishes between core conditions and peripheral conditions according to (Ragin 2008) and (Peer 2011)'s methods, that is, a condition that appears simultaneously in both the intermediate solution and the parsimonious solution is regarded as a core condition, while a condition that only appears in the intermediate solution is regarded as a peripheral condition. The analysis results are presented in Table 4.

• Configurational Analysis for “High Deliberative Capacity”. Configuration 1 indicates that a deliberative system will exhibit high deliberative capacity as long as it performs well in the empowered space, transmission, and decisiveness, regardless of its performance in the public space, accountability, and meta-deliberation. Town JS is a typical case in this configuration, with insufficient foundational conditions for the development of its deliberative system. Firstly, the development of public space is lagging. Town JS is located on an island with a small and structurally simple economy focused on aquaculture and tourism, which leads to simple public opinions and interest demands mainly focusing on economic development, environmental protection, and infrastructure construction. Secondly, there is a low level of transparency in accountability, with weak government information disclosure highlighted by non-standardized, untimely, and incomplete disclosure. Finally, the institutionalization of meta-deliberation is not sound enough. Although deliberative work rules have been issued and regular learning and training institutions have been established for participants, there is still a lack of institutions for assessing feedback on deliberative activities and promoting innovation. Despite these unfavorable conditions, the leading cadres of Town JS attach great importance to deliberation and carry out every deliberative activity very seriously. They extensively publicize and solicit public opinions through various channels before the deliberation, ensure fairness and justice in the deliberation, and promote the implementation of the deliberative results through the accountability institution after the deliberation. With the outstanding role played by the government, Town JS has achieved a high deliberative capacity, leading to a strong deliberative consciousness among officials and the public who actively participate in deliberative activities. Configuration 2 demonstrates that a deliberative system will possess high deliberative capacity as long as it excels in transmission, meta-deliberation, and decisiveness, regardless of its performance in public space, empowered space, and accountability. Town CN is a typical case in this configuration, with relatively average foundational conditions for the development of its deliberative system. Firstly, the development level of public spaces is generally average. Town CN is located near mountains and seas, with abundant ecological resources. Its economy is mainly based on agriculture and tourism, supplemented by manufacturing. As a result, the public opinions it collected involve five aspects: economic development, environmental protection, infrastructure construction, medical and health care, and school education. The diversity of public interest expressions is moderately average. Secondly, the degree of equality in deliberation is generally average. Although the masses in Town CN can actively participate in deliberation and have participated in special research and training on relevant issues, they cannot participate in agenda setting, and their equal right to speak has not been effectively guaranteed by institutions. Finally, the transparency of accountability is generally average. Although the government of Town CN has received relevant honors on information disclosure, there are still some problems such as untimely and incomplete information disclosure. Even though the basic conditions are average, Town CN's advantages in the institutionalization of meta-deliberation well compensate for this deficiency. On the one hand, Town CN not only introduced the rules of deliberation work, but also established institutions for regular learning, training, and evaluating and providing feedback on deliberative activities for the participants. On the other hand, the leading cadres of Town CN, like those in Town JS, attach great importance to deliberation. They have not only established highly diversified channels to collect public opinions but also established and effectively implemented accountability institutions of deliberative results. It is these advantages that enable Town CN to have high deliberative capacity and create a locally characteristic deliberation brand. Configuration 3 illustrates that a deliberative system will achieve high deliberative capacity as long as it performs well in public space, empowered space, accountability, and meta-deliberation, regardless of its performance in transmission and decisiveness. Sub-district SJ is a typical case in this configuration, with favorable foundational conditions for developing a deliberative system. Firstly, its public space is relatively developed. Sub-district SJ is adjacent to the main urban area of Taizhou City, with well-developed primary and secondary industries. It has both large-scale planting and breeding bases, as well as a large number of large-scale industrial enterprises. There are also many industry associations and other social organizations, and the expressions of public interests are relatively sufficient and diverse, involving 12 aspects such as economic development, medical and health care, school education, and cultural construction. Secondly, the degree of equality in deliberation is relatively high. Sub-district SJ not only organizes participants to study and research on the topics but also procedurally guarantees the equal speaking rights of participants. The masses can not only participate extensively in deliberation but also substantially participate in the setting of deliberative agendas. Thirdly, the transparency of accountability is relatively high, and the government information disclosure of Sub-district SJ is timely and standardized. It has received an excellent rating in the annual assessment. Finally, the degree of standardization and institutionalization is relatively high. Like Town CN, it has not only introduced deliberation work rules but also established institutions for regular learning, training, and evaluating and providing feedback on deliberative activities for the participants. There are two shortcomings in Sub-district SJ. On the one hand, its transmission mechanism is moderately diverse, which may be related to its well-developed public space. The diverse and sufficient public opinion expressions in Sub-district SJ reduce the need for the government to establish diverse channels for public opinion collection. On the other hand, the effectiveness of decisiveness is generally average. This is mainly due to the cognitive level of government officials, but this deficiency can be compensated for by a higher level of deliberative democracy institutionalization.

• Configurational Analysis for “Low Deliberative Capacity”. There are three configurations for “low deliberative capacity”: Configuration 1 (low equality of empowered space * low diversity of transmission * low institutionalization of meta-deliberation * low effectiveness of decisiveness), Configuration 2 (low plurality of public space * low diversity of transmission * low transparency of accountability * low institutionalization of meta-deliberation * low effectiveness of decisiveness), and Configuration 3 (low plurality of public space * low equality of empowered space * low diversity of transmission * low transparency of accountability * low institutionalization of meta-deliberation). Configuration 1 indicates that if a deliberation system performs inadequately in empowered space, transmission, meta-deliberation, and decisiveness, regardless of its performance in public space and accountability, its deliberative capacity will be low. Configuration 2 suggests that if a deliberative system performs inadequately in all aspects except empowered space, then its deliberative capacity will be low. Configuration 3 shows that if a deliberative system performs inadequately in all aspects except decisiveness, then its deliberative capacity will be low. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, low institutionalization of meta-deliberation is a necessary condition for low deliberative capacity, implying that if a case has low deliberative capacity, its institutionalization of meta-deliberation will also be low.

Robustness test of results

The robustness test of results is a crucial step in QCA analysis. There are various ways to conduct robustness tests in QCA, such as changing calibrations, altering minimum case frequencies or consistency thresholds, replacing conditional variables, adding or removing cases, etc. After performing robustness tests, if the analysis results do not undergo substantial changes in terms of the number and composition of configurations, consistency, coverage, etc, then the results are considered reliable. In this study, robustness testing was conducted by changing the calibration anchor points, adjusting the fully belonging threshold, crossover points, and fully non-belonging threshold from the original settings of 5, 3.5, 1.5 to 5, 3.5, 2. Other threshold settings remained unchanged, and the final configuration analysis results are presented in Table 5. A comparison between Tables 4, 5 shows that apart from slight changes in the values of consistency and coverage, as well as a minor alteration in Configuration 3 for “low deliberative capacity,” the two tables are largely consistent. This indicates that the analysis passed the robustness test and the research results are reliable.

Category analysis of practical forms

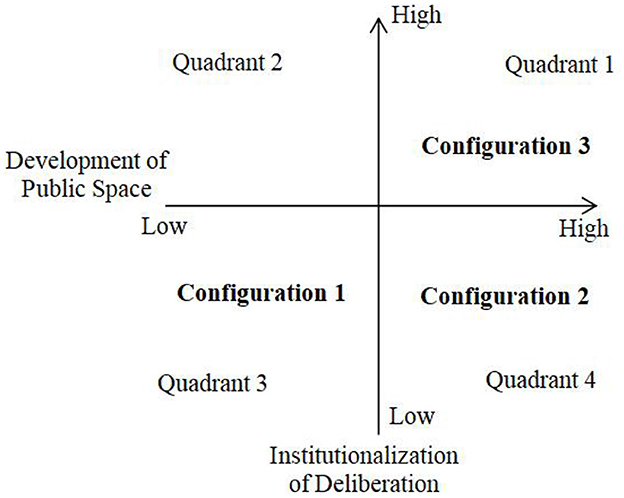

From the perspective of the roles played by the government and society, the three configurations leading to high deliberative capacity mentioned above can be classified into two practical types. The first type includes configuration 1 and configuration 2, characterized by high diversity in transmission and high effectiveness in decisiveness but without any requirements for public space and accountability mechanisms. The study has shown that the public opinion transmission channels that play significant roles in empowered space deliberation are mostly constructed or led by the government, and the decisiveness mechanisms crucial for the implementation of deliberative outcomes are actively constructed by the government. Therefore, the high diversity of transmission and the high effectiveness of decisiveness mean that governments play important roles. Overall, this type of configurations reflect the government's role and can be referred to as a government-single-driven type. Configuration 3 represents the second type, characterized by high plurality in public space, high equality in empowered space, high transparency in accountability, and high institutionalization in meta-deliberation without any requirements for transmission and decisiveness. This type of configuration has higher requirements for the completeness of antecedent conditions compared to the first type. High plurality of public space is a result of social influence, high institutionalization of meta-deliberation is a result of government influence, high equality of empowered space and high transparency of accountability are results of combined social and government influence, therefore, this type of configuration reflects the combined roles of government and society and can be termed as government-society-dual driven. Additionally, these three configurations imply three different levels of maturity in the development of deliberative systems. Four quadrants can be constructed with the development level of public space as the vertical axis and the institutionalization level of deliberation as the horizontal axis. Configuration 1 has no requirements in terms of public space, accountability, and meta-deliberation, which means that it has low or no requirements for the development of public space and the institutionalization of deliberation. Therefore, it has the lowest requirements for the maturity of the deliberative system and can be located in Quadrant 3; Configuration 2 has no requirements for public space, empowered space, and accountability, which means that it has low or no requirements on the development degree of public space, but has high requirements for the degree of deliberation institutionalization. Therefore, it requires the deliberation system to have a medium level of maturity and is located in Quadrant 4; Configuration 3 has no requirements for transmission and the decisiveness but proposes higher requirements for the development of public space and the degree of deliberation institutionalization. Therefore, it has the highest requirements for the maturity of the deliberation system and is located in Quadrant 1. It should be pointed out here that Configuration 1 has the lowest requirement for the maturity of the deliberation system, which does not mean that the maturity of the deliberation system in all cases within this configuration is necessarily low (refer to Figure 2).

Conclusion and implications

Establishing and improving the Chinese deliberative system can effectively enhance the deliberative capacity of Chinese society. Compared with the rich practices of Chinese local governments, theoretical research on the Chinese deliberative system has lagged behind. Do theories of Western deliberative systems apply to China, and to what extent? Answering these questions requires testing them within China's political context and using Chinese empirical data. This study is such an attempt: it employs Dryzek's analytical framework of deliberative systems to conduct an empirical analysis of grassroots deliberative democracy in China, aiming to reveal the specific mechanisms and practical forms through which the constituent elements of deliberative systems influence deliberative capacity.

First, the six constituent elements of the deliberative system—namely public space, empowered space, transmission, accountability, meta-deliberation, and decisiveness—all have a significant impact on the deliberative capacity of the system. However, no single factor constitutes a necessary condition for high deliberative capacity, meaning no single factor is indispensable for the deliberative system to generate high deliberative capacity. High deliberative capacity is not the result of any single factor but rather the combined effect of multiple factors. These factors are closely interconnected, and in different contexts, they can form different combinations of factors (configurations) to exert significant influence on the outcome variable (deliberative capacity). This study identifies three key configurations (as mentioned above). These findings suggest that in the process of enhancing deliberative capacity by constructing deliberative systems, local governments, on the one hand, should not overly rely on any single factor. Instead, they should strengthen systematic thinking, enhance comprehensive planning, and build dynamic mechanisms for multi-factor coordination. On the other hand, they should base their efforts on local realities, pursue targeted strengthening of specific factors, and explore differentiated configuration paths suitable for their own contexts.

Secondly, From the perspective of the roles played by the government and society, the three configurations that achieve high deliberative capacity can be categorized into two practical forms: government single-driven type and government-society-dual-driven type. This classification framework not only reveals differences in the power sources of deliberative systems but also reflects the underlying logic of state-society relations in the practice of deliberative democracy. The former represents a kind of configuration paths led by administrative power, requiring the government to play a core role in constructing the deliberative system. It is suitable for regions with weak social self-governance capabilities. The latter emphasizes equal collaboration between the government and society to jointly exert influence, suitable for areas abundant in social capital. Traditional theories of deliberative democracy emphasize that the development of the public space is a prerequisite for the advancement of deliberative democracy. However, this study finds that even in regions with an underdeveloped public space, it does not necessarily mean that deliberative democracy cannot develop effectively. When social forces are insufficient, the government can play a leading role to compensate for this deficiency. As illustrated by the case of JS Town above, the town government can address the shortage of social capital and thus achieve the improvement of deliberative capacity by enhancing its own “decisiveness”, such as improving its understanding of deliberative democracy and strengthening the supervision and implementation of deliberative outcomes.

Thirdly, the relationship between the maturity of a deliberative system and its deliberative capacity is not a simple linear correlation, but allows for the possibility of pluralistic configurational adaptation. In other words, high deliberative capacity is not exclusive to highly mature deliberative systems; low-maturity deliberative systems can also achieve high deliberative capacity as long as appropriate configurations are adopted. The three configurations that produce high deliberative capacity adapt to three deliberative systems of different maturity levels. Configuration 1 can adapt to contexts where both the development level of the public space and the institutionalization of deliberation are low, so it is suitable for low-maturity deliberative systems. Configuration 2 can adapt to situations where the development level of the public space is low but the institutionalization of deliberation is high, so it is suitable for moderate-maturity deliberative systems. Configuration 3 can adapt to scenarios where both the development level of the public space and the institutionalization of deliberation are high, so it is suitable for high-maturity deliberative systems.

Fourthly, the correlations between the constituent elements of a deliberative system and its deliberative capacity exhibit significant contextual dependence, varying as the system's maturity evolves. In other words, the roles of constituent elements in shaping deliberative capacity vary with the maturity level of the deliberative system. For instance, transmission is particularly critical for Configuration 1 and Configuration 2. This can be attributed to the fact that, in these two configurations, the public space is underdeveloped, and citizens' interests and opinions are expressed in a singular and insufficient manner. As a result, the diversified communication mechanisms established by the government become a “lifeline” for the government to fully understand public opinion. By contrast, transmission is largely dispensable for Configuration 3, where a well-developed public space enables citizens to spontaneously express diverse opinions, rendering government-led diversified communication mechanisms less necessary. In short, the role of transmission diminishes as the deliberative system matures. Similarly, decisiveness is of utmost importance for Configuration 1 and Configuration 2 but is less critical for Configuration 3. In Configuration 3, a developed public space and sound accountability mechanisms ensure effective public supervision over the implementation of deliberative outcomes. Moreover, the deliberative system possesses institutionalized capacities for self-reflection and self-improvement, which collectively weaken the importance of decisiveness to some extent.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Department of Scientific Research, Taizhou Institute of Administration. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HW: Methodology, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Project administration. HX: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. LZ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SL: Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Research Project of the Research Center for Comprehensive and Strict Party Governance of the Party School of the CPC Zhejiang Provincial Committee, a new type of key think tank in Zhejiang Province, “Theoretical Framework and Practical Path of Constructing a Deliberative System from the Perspective of Whole-Process People's Democracy: Empirical Analysis Based on Outstanding Deliberation Cases in Zhejiang Province” (CYZD202209).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1602445/full#supplementary-material

References

Boswell, J., Hendriks, C. M., and Selen, A. (2016). Message received? Examining transmission in deliberative systems. Crit. Policy Stud. 3, 263–283. doi: 10.1080/19460171.2016.1188712

Carolyn, M. (2016). Coupling citizens and elites in deliberative systems: the role of institutional design. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 1, 43–60. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12123

Chengfu, Z., and Chongqi, Y. (2023). Rebuilding the value of public governance. Teach. Res. 1, 66–77. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.0257-2826.2023.01.007

Chunyan, H., and Bihua, L. (2016). A review of foreign social accountability research: examination of influencing factors. Adm. Forum 4, 103–108. doi: 10.16637/j.cnki.23-1360/d.2016.04.019

Curato, N. C. (2015). Deliberative capacity as an indicator of democratic quality: the case of the Philippines. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1, 99–116. doi: 10.1177/0192512113504337

Dawei, Z. (2020a). Identification of conditions, types, and quality of deliberative systems in community governance-based on a comparison of 6 community deliberative experiment cases. Exploration 6, 45–54. doi: 10.16501/j.cnki.50-1019/d.2020.06.004

Dawei, Z. (2020b). Party-led group discussions: leading deliberations in community governance in the deliberative system - a case study of the '1+n+x' community deliberation experiment in Tianchang City. Zhongzhou J. 10, 75–82. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-0751.2020.10.013

Dawei, Z., and Yichen, Z. (2021). Leading deliberation: new developments in party-led autonomous governance under the theory of deliberative systems - a case study of Muzhai Village. Yizhou, Guangxi. Hunan Forum 5, 47–62. doi: 10.16479/j.cnki.cn43-1160/d.2021.05.005

Dryzek, J., and Niemeyer, S. (2010). The Foundations and Frontiers of Deliberative Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199562947.001.0001

Dryzek, J. S. (2009a). Democratization as deliberative capacity building. Comp. Polit. Stud. 42, 1379–1402. doi: 10.1177/0010414009332129

Dryzek, J. S. (2009b). Democratization as deliberative capacity building. Comp. Polit. Stud. 11, 1379–1402. doi: 10.1177/0010414009332129

Fafeng, S. (2019). Elements, characteristics and enhancement paths of deliberative capacity of social organizations in current China. Acad. Res. 11, 55–59. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-7326.2019.11.008

Haiyan, Z. (2019). Forms and effectiveness analysis of networked deliberative democracy in public decision-making. J. Shenzhen Univ. 4, 125–133. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-260X.2019.04.014

Huntington, S. P. (2008). Political Order in Changing Societies. Shanghai: Shanghai People's Publishing House.

Huosheng, T., and Zhihong, W. (2008). Habermas' dual-track deliberative democracy theory. J. Theor. Res. Assoc. Chin. People's Polit. Consult. Conf. 1, 32–39.

Invernizzi-Accetti, C., and Wolkenstein, F. (2017). The crisis of party democracy, cognitive mobilization, and the case for making parties more deliberative. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 111, 97–109. doi: 10.1017/S0003055416000526

Jianjun, G., Liu, W., and Wei, C. (2016). Problems and optimization of deliberative democracy in the people's political consultative conference-practice and exploration of hangzhou municipal people's political consultative conference. J. PartySchool Tianjin Municipal Committee of C. P. C, 2, 42–48. doi: 10.16029/j.cnki.1008-410X.2016.02.008

Jinglun, Y., and Yongxin, C. (2016). How do social elites promote rural community governance? experience from taomi community in Taiwan. Nanjing Soc. Sci. 5, 75–81. doi: 10.15937/j.cnki.issn1001-8263.2016.05.011

John, S. D. (2009). Democratization as deliberative capacity building. Comp. Polit. Stud. 54, 1379–1402. doi: 10.1177/0010414009332129

Krister, L. (2014). Deliberative capacity of individuals-dimensions and determinants. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 1, 67–86. doi: 10.14738/assrj.14.234

Mendonça, R. F. (2016). Mitigating systemic dangers: the role of connectivity inducers in a deliberative system. Crit. Policy Stud. 2, 171–190. doi: 10.1080/19460171.2016.1165127

Milewicz, K. M., and Goodin, R. E. (2016). Deliberative capacity building through international organizations: the case of the universal periodic review of human rights. Brit. J. Polit. Sci. 2, 513–533. doi: 10.1017/S0007123415000708

Nan, Y. (2021). Path selection for enhancing government accountability effectiveness from a process perspective. Yunnan Soc. Sci. 3, 26–33. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-8691.2021.03.005

Parkinson, J, and Mansbridge, J. (2013). Deliberative Systems: Deliberative Democracy at the Large Scale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139178914

Parkinson, J. (2010). “Conceptualising and mapping the deliberative society,” in PSA 60th Anniversary Conference. Edinburgh.

Peer, C. F. (2011). Building better causal theories: a fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manage. J. 2, 393–420. doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.60263120

Ragin, C. C. (2008). Measurement Versus Calibration: A Set-Theoretic Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199286546.003.0008

Rihoux, B., and Ragin, C. C. (2012). Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Schouten, G., Leroy, P., and Glasbergen, P. (2012). On the deliberative capacity of private multi-stakeholder governance: the roundtables on responsible soy and sustainable palm oil. Ecol. Econ. 83, 42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.007

Siyao, Z., and Tianguang, M. (2022). Government information disclosure and governance effectiveness in public crisis management - based on a survey experiment. Public Manage. Policy Rev. 1, 88–103. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4026.2022.01.014

Suiter, J., Muradova, L., Gastil, J., and Farrell, D. M. (2020). Scaling up deliberation: testing the potential of mini-publics to enhance the deliberative capacity of citizens. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 26, 253–272. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12405

Tang, B. (2014). Development and prospects of deliberative democracy in China: the dimensions of deliberative capacity building. J. Chin. Polit. Sci. 2, 115–132. doi: 10.1007/s11366-014-9285-3

Tianshu, Q. (2010). Construction of deliberative capacity in democratic politics in China: structures, norms and values. J. PartySchool Tianjin Municipal Committee of C. P. C. 3, 35–69.

Wei, W. (2016). Research on the path to enhance the deliberative capacity of participating parties. J. PartySchool Zhejiang Provincial Committee of C. P. C. 6, 91–98. doi: 10.15944/j.cnki.33-1010/d.2016.06.013

Xiaolin, W, and Yiyun, X. (2017). Between democracy and stability: decision-making deliberation views of local government officials - based on questionnaire analysis of 814 government officials, Exploration 5, 47–53. doi: 10.16501/j.cnki.50-1019/d.2017.05.007

Xiongwei, S. (2016). The logical starting point, basic connotation and improvement path of government deliberation. Jianghan Forum 6, 42–47. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-854X.2016.06.006

Yujia, G, and Dengwen, Z. (2022). Sustainable development of grassroots deliberative democracy in China - sources of motivation, resistance factors and path selection. Soc. Sci. Res. 2, 57–65. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-4769.2022.02.007

Keywords: influencing factors, deliberative capacity, configuration path, deliberative system, qualitative analysis of fuzzy-sets (fsQCA)

Citation: Wang H, Xie H, Zhu L and Liang S (2025) The influencing factors of deliberative capacity and their configuration paths from the perspective of deliberative system: a fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis of 30 cases. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1602445. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1602445

Received: 03 April 2025; Accepted: 16 July 2025;

Published: 11 August 2025.

Edited by:

Oliver Fernando Hidalgo, University of Passau, GermanyReviewed by:

Fengxian Qiu, Anhui Normal University, ChinaPei Zhijun, Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics, China

Copyright © 2025 Wang, Xie, Zhu and Liang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Han Wang, aGFuY2V3b25nNTA5QDE2My5jb20=

Han Wang

Han Wang Hui Xie2

Hui Xie2