Abstract

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) play a key role in climate governance, yet a systematic overview of their engagement at the global scale remains limited. This study aims to address this gap by systematically reviewing 40 empirical studies on NGO involvement in global climate governance. The principal findings of this research are that (1) most studies appeared in environment-focused and governance-related journals, covering less than a decade; (2) theoretical frameworks, predominantly materialist, underpinned most analyses; (3) qualitative methods, especially case studies, prevailed over quantitative approaches; (4) environmental and social NGOs were central actors, mainly engaged in policy option-identification and formulation; (5) both inside and outside strategies were widely used, while entrepreneurial strategies received less attention; and (6) organizational factors were more prevalent than state- or international-level dynamics in shaping NGO engagement. This study offers insights into how NGOs participate in global climate governance and suggests implications for future research, policymaking, and practice.

1 Introduction

Climate change presents one of the most critical challenges to the social-ecological system, threatening human wellbeing. In response to this complex and “wicked” issue, a regime complex for climate change has emerged, involving state, private and civil society actors on multiple scales (Keohane and Victor, 2011). Within this evolving governance landscape, NGOs have increasingly become established as key actors in addressing climate change (Ben Youssef, 2024; Tosun et al., 2024). While NGOs engage in climate governance at multiple levels, from the local to the global, this study will focus exclusively on those operating beyond the state.

In recent decades, NGOs have gained significant influence in the area of global climate governance. Although global efforts have been made to tackle climate change, significant international governance gaps have nonetheless emerged, creating both opportunities and pressures for NGOs to expand their roles. This dynamic can be observed in their growing institutional presence: the cumulative number of NGOs granted observer status by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has grown from 162 at COP 1 to 3782 at COP 29 (UNFCCC, 2024b).

With this sharp rise in participation, NGOs now contribute to three interrelated areas: representation, accountability and resilience. First, NGOs amplify the voices of marginalized communities, such as indigenous peoples and low-income populations in developing countries, ensuring that diverse perspectives are represented in international negotiations (Gereke and Brühl, 2019). This inclusive participation helps to address democratic deficits and bolster the legitimacy of global climate institutions (Marquardt and Bäckstrand, 2022; Zhao, 2024). Second, NGOs enhance accountability and transparency with climate governance. They monitor state commitments, for instance, by tracking compliance with Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, assessing progress and exposing policy gaps (Bäckstrand et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2024). They also mobilize the grassroots to shape government positions in international negotiation (Pandey, 2015). Third, NGOs play an increasing role in disaster risk reduction (DRR) and resilience-building. Partnering with governments and the private sector, they respond to the immediate needs of vulnerable communities, raise public awareness of various DRR strategies, and enrich DDR practice with locally-grounded, biophilic perspectives that emphasize human–nature interactions (Lassa, 2018; Lencastre et al., 2023; Lopes et al., 2025).

Despite NGOs' considerable contributions, their engagement in global climate governance is not without challenges. They are facing political, social, and organizational obstacles, which often constrain their ability to deliver on their promise. First, restrictive political structures often limit their effectiveness and independence. Many governments, particularly those hesitant to adopt more stringent climate policies that could disrupt their political or economic agendas, tend to restrict NGO involvement or sideline them in favor of business interests (Hanegraaff, 2015; Liu et al., 2017; Middeldorp and Le Billon, 2019). This resistance is especially pronounced in authoritarian and semi-authoritarian contexts, where NGOs face legal restrictions, state surveillance, and even political persecution, all of which curtail their participation in climate governance (Cadag, 2025). Second, social skepticism toward NGOs has been mounting amid populist narratives, concerns over international funding as foreign control, as well as accusations of elite detachment from local realities (Brombo, 2021; Steinberg and Wertman, 2018). The proliferation of “briefcase NGOs”—organizations formed primarily to attract international funding without delivering meaningful services—has further eroded public confidence (Dupuy et al., 2015). Finally, internal governance gaps, especially in terms of transparency deficits, have raised critical concerns. Some NGOs struggle to uphold the very transparency and accountability standards they promote externally. High-profile incidents, such as the whistleblower case within Transparency International, illustrate the gap between advocacy and practice, raising questions about their credibility (Barrington, 2025).

However, a universally accepted definition of the term NGO has yet to emerge. Some researchers emphasize the function of NGOs, defining them as “advocacy organizations pursuing principled goals and public benefits, often using a mix of domestic and global actions” (Henry et al., 2019) or as organizations attempting to influence international law and policy (Raustiala, 2020). Some others stress the independent and voluntary nature of NGOs, framing them as actors primarily driven by non-profit goals distinct from state or market interests (Anheier and Toepler, 2023). This study tends to agree with the latter, as firstly it is congruent with the UNFCCC approach to admitting observer organizations, which has been adopted by multiple climate governance scholars, given the central role of UNFCCC as the primary framework for global climate action. Secondly, it accounts for the diverse range of NGOs in terms of their resources, size, and influence. These organizations can range from large globally-famed entities, such as Greenpeace, to small grassroots organizations with minimal global presence.

In recent years, several literature reviews have examined NGO engagement in climate or environmental governance from multiple angles. Some review articles have highlighted the local scale (Ibones et al., 2024); some have focused on the state scale (Liu et al., 2017); some have addressed the regional scale (Haris et al., 2020). Some have concentrated on the roles of NGOs; some have stressed the strategies that NGOs have adopted to address climate change (Lu et al., 2023); some have sought to assess the conditions for effective NGO governance activities (Sharma, 2023). These studies have added to our understanding of NGOs' roles across different contexts.

Nevertheless, they have predominantly concentrated on the national or subnational levels and occasionally on regional levels, leaving the global dimension relatively underexplored. The global scale merits further investigation, as it operates beyond the jurisdiction of individual states, relying instead on regulating interdependent relationships among diverse actors in the absence of a central authority (Rosenau, 1999). Moreover, although these reviews have assessed how NGOs participate in climate governance processes, including their roles, strategies and operation conditions, they pay relatively scarce attention to the broader trajectory of scholarship on this topic. This leaves a gap for a review that not only synthesizes NGO engagement but also traces the development of research in this field.

To address this gap, the present review focuses explicitly on NGO climate action at the global scale, integrating macro research trends and micro-level insights. On the one hand, this review attempts to analyze data distribution from all possible perspectives, including research designs, roles, strategies and impacting factors, to identify emerging directions. On the other hand, it aims to provide a road map for policy-makers and practitioners, especially those involved in monitoring NDCs through their expertise and commitment, promoting a more equitable climate finance mechanism grounded in climate justice, and strengthening climate adaptation and resilience by integrating ecological and human wellbeing.

Against this background, this paper addresses two research questions:

-

(1) What are the research trends on NGO engagement in global climate governance?

-

(2) How do NGOs engage in this arena?

By answering these two questions, this study offers a synthesis of (1) the research trends, including publication patterns, theoretical frameworks and research designs; and (2) NGO engagement, encompassing categories, roles, strategies and determining factors.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Data collection and filtering

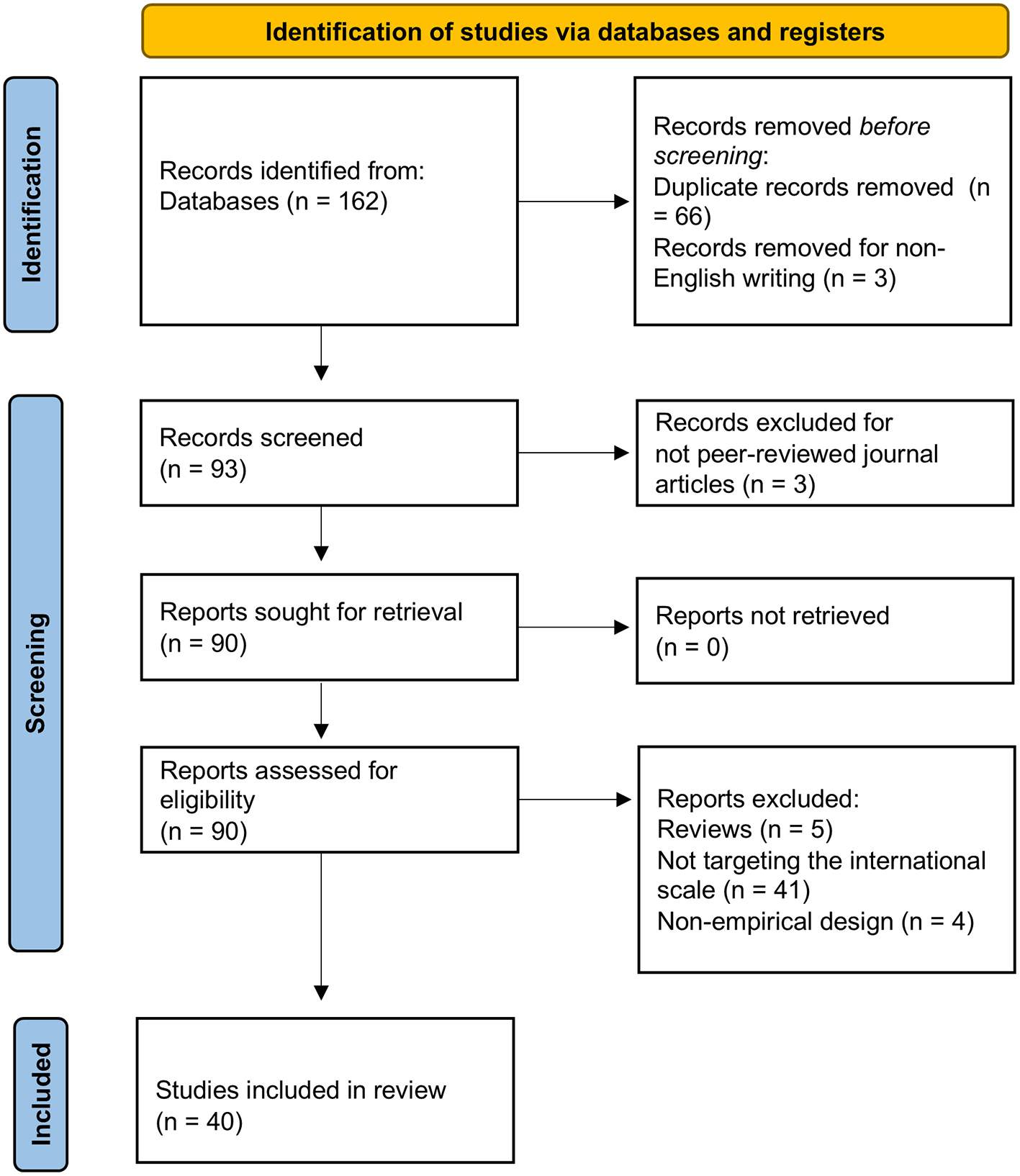

To conduct this review, this study employed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method, following a systematic and rigorous procedure to ensure transparency in the process (Moher et al., 2009). The PRISMA method recommends that four steps are followed in conducting a systematic review: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flow chart of the article selection process.

Identification. In March 2025, a comprehensive literature search was undertaken using two major databases: Web of Science and Scopus, both of which have been widely recognized for their use in producing high-quality systematic reviews (Haris et al., 2020; Townsend et al., 2023). To capture recent relevant research trends, the publication period was restricted to 2014–2024, and only documents classified as “articles” were included. Specific search strings employed in the databases were: TI (“Climat*” OR “global warming*” OR “temperature ris*” OR “sea level ris*” OR “el-nino” OR “la-nina”) AND TI (“nongovernmental organi*ation*” OR “non governmental organi*ation*” OR “NGO” OR “NGOs” OR “ENGO” OR “ENGOs” OR “INGO” OR “INGOs” OR “civil society” OR “grassroot communities” OR “third sector” OR “voluntary sector”). In order to focus specifically on NGO engagement in global climate governance, a title search was used at this point. The initial search yielded 162 results: 71 from Web of Science and 91 from Scopus. After removing duplicates and non-English papers, 93 articles proceeded to the screening phase. Only English-language articles were included due to limited capacity to review and analyze non-English texts. While this decision may introduce some linguistic bias, the risk of missing key contributions is limited, as most influential studies in this field are predominantly published in English.

Screening. During this stage, three articles published in non-peer-reviewed journals were excluded. Consequently, 90 records went on to the eligibility phase.

Eligibility. Each of the articles was then manually assessed based on pre-set inclusion criteria after a thorough review. The criteria required that the studies should: (1) focus on NGOs; (2) address climate governance beyond the national level; and (3) employ an empirical research design. In total, 50 articles that fell short of the criteria were excluded at this stage.

Inclusion. After screening and filtering, this number was narrowed down to 40, in alignment with Robinson and Lowe's (2015) recommendation that a manageable yet comprehensive sample size for a systematic review should be usually less than 50.

2.2 Coding scheme

To explore and examine the trends and developments in NGO engagement in global climate governance, this study developed a coding scheme based on six dimensions. These dimensions were adopted from previous studies on climate governance as well as NGOs or publications by authoritative international organizations. For example, Haris et al. (2020) categorized the role of environmental NGOs based on a four-phase policy cycle, when presenting their findings on NGO climate action in Southeast Asia. In a similar way, Townsend et al. (2023) coded NGO strategies into four groups according to the target (government or business) and interaction with the target (inside or outside). Additionally, in their review of NGO scholarship in the field of international development, Brass et al. (2018) coded journal publications, NGO activities, and paths.

-

(1) Codes for the theoretical frameworks

Based upon variations in the privileged assumptions of major global governance theories and paradigms, this inquiry classified theoretical frameworks into six categories: materialist, ideationalist, relationalist, historical, self-proposed, or unspecified (McCourt, 2016; Sørensen, 2008; Tucker, 2021).

-

(2) Codes for the categories of NGOs

Drawing on the nine constituencies of NGOs as defined by the UNFCCC Secretariat (2023), this investigation grouped NGOs into five categories: economic, environmental, social, and research and independent (R & I) NGOs, and local governments and municipal authorities (LGMA). Economic NGOs included two constituencies: business and industry NGOs (BINGO), and farmers, while social NGOs encompassed four constituencies: indigenous peoples' organizations (IPO), trade union NGOs (TUNGO), women and gender (WGC), and youth NGOs (YOUNGO).

-

(3) Codes for the roles of NGOs

Haris et al. (2020) proposed that the roles of NGOs in climate governance could be classified into four functions: identification of policy options, policy formulation, policy implementation, and policy evaluation and monitoring.

-

(4) Codes for the strategies of NGOs

Building on insights from Nasiritousi (2019) and Townsend et al. (2023), this research categorized NGOs' strategies in global climate governance into three pathways, based their interaction with governments: inside strategy, outside strategy and entrepreneurial strategy.

-

(5) Codes for factors affecting NGO engagement

Following Singer's (1961) levels of analysis framework in international relations, this current study categorized the factors influencing effective NGO engagement in global climate governance into three distinct levels: organizational, state, and international.

3 Research results

3.1 Distribution of publication

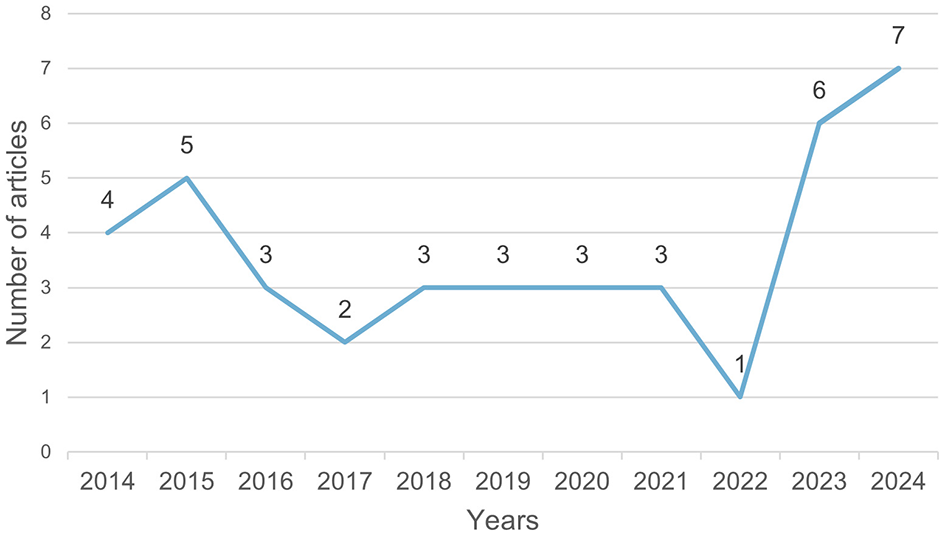

As shown in Figure 2, there was a fluctuating yet increasing number of empirical studies on NGOs' global climate action over the years from 2014 to 2024, indicating a growing interest in NGOs among global climate governance scholars. It goes with greater recognition of NGO influences in the global climate governance architecture amid pressing climate challenges. Specifically, the past 2 years have seen a sharp rise in publications, peaking at seven studies in 2024. This recent growth coincides with major institutional and political developments, including the operationalization of Paris Agreement mechanisms such as the Global Stocktake, and heightened attention to climate finance instruments such as the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD; UNFCCC, 2022, 2023, 2024a). Compared to earlier fluctuations, this surge appears more sustained, marking a potential shift in the academic agenda toward systematic examination of NGO action in global climate governance.

Figure 2

Number of published papers per year.

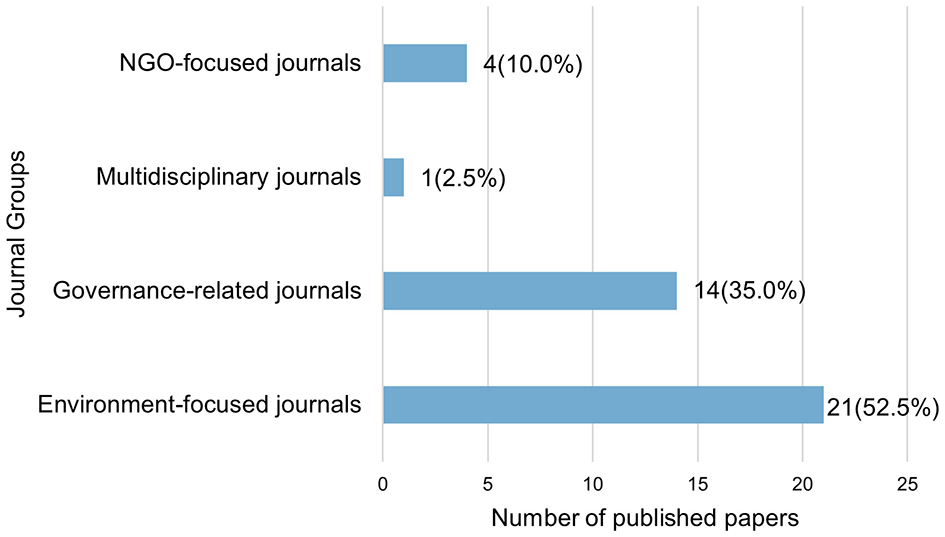

With regards journal distribution, these peer-reviewed articles have appeared in 35 academic journals, reflecting a multidimensional and multidisciplinary research focus. Notably, four journals, publishing two or more related studies, are more receptive to NGO climate action beyond the state level: Environmental Communication (3 studies), Global Environmental Politics (3 studies), Climate Policy (2 studies), and Sustainability (2 studies). Based on research focus, the journals identified in the present study can roughly be categorized into four groups (Figure 3). First, environment-focused journals, like Climate Policy, Environmental Policy and Governance, and Global Environmental Change, addressed varied climate-related issues. Second, governance-related journals, such as Global Governance, British Journal of Political Science, and Global Policy, emphasized the diversity of political and governance perspectives explored within the field. Third, NGO-focused journals, like Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly and Journal of Civil Society, extended the discussion on NGO dynamism in global climate initiatives. Fourth, multidisciplinary journals, like Sci, also published articles in this field. Together, 87.5% of the papers were published in outlets focusing on environmental governance (52.5%) and governance studies (35.0%).

Figure 3

Distribution of published papers by journal groups.

3.2 Theoretical frameworks

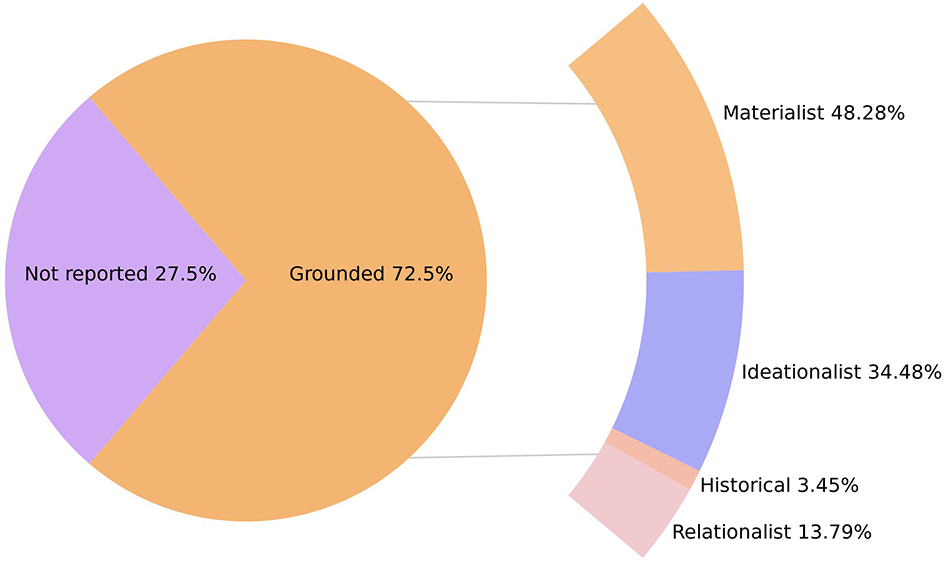

The majority of the studies (72.5%) explicitly introduced the theoretical or analytic frameworks underpinning their research (Figure 4). For instance, Sunnemark (2024) explored the dynamics of counter-hegemony and anti-colonial climate alliances within global civil society and then constructed his post-apocalyptic environmentalism framework by integrating neo-Gramscian insights and post- and decolonial perspectives. Notably he devoted the whole literature review section to introducing and elaborating on this theoretical framework. It should be pointed out that while these reviewed studies lacked a shared theoretical foundation, a high ratio (48.3%) of those grounded upon governance theories seemed to echo the premises of materialism, with a smaller proportion of them being ideationalist (34.5%) and relationalist (13.8%). For example, frameworks such as collective action and neopluralist perspectives (Hanegraaff, 2015) and polycentric climate governance (Tosun et al., 2024) were both premised on materialist assumptions, though differing in specific theoretical orientations. Meanwhile, inter-risk framing contests (Enggaard et al., 2023) and green governmentality (Uggla and Soneryd, 2017) were based on ideationalist assumptions. At the same time, semantic network analysis (Kim and Hara, 2024) was definitely rooted in relationalist assumptions. Although theoretical approaches of this field display a degree of diversity, prevailing analyses tend to frame NGO roles in terms of power, resources, and institutional capacities, which may downplay ideational or relational mechanisms to some extent.

Figure 4

Distributed of adopted theories in the reviewed studies.

However, a minority of the studies (27.5%) did not explicitly present a theoretical or analytical framework for their research (Figure 4). For example, Aubert et al. (2020) examined multistakeholder engagement dynamics within the “4 per 1000” initiative, drawing upon literature related to voluntary initiatives, and science and technology studies. While these theoretical underpinnings were mentioned in the introduction section, this study did not clearly articulate how these foundational ideas informed the empirical analyses presented in the subsequent sections. A lack of clarity and transparency in linking theory with analysis may limit cumulative theorization in this field.

3.3 Research design

These empirical studies showed great diversity in research design, differing in terms of their research methods, sample size, study length, data collection and analysis methods.

In terms of research methods, Table 1 demonstrates a marked preference on qualitative approaches, with quantitative and mixed designs far less frequently employed in examining NGO engagement in global climate governance. More than half of the studies (65.0%) employed qualitative approaches, with case studies being the most common. For example, Chan (2021) qualitatively explored how NGOs have provided negotiation support to developing countries, to enable them to navigate complex multilateral processes more effectively, based on three case studies: the Legal Response Initiative, Independent Diplomat, and the International Institute for Environment and Development. Quantitative methods accounted for 20.0% of the studies, while mixed methods were applied even less frequently (15.0%). For instance, Krantz (2021) employed descriptive statistics to capture patterns of religious NGOs' participation in UNFCCC conferences while Tosun and Levario Saad (2023) integrated ordered logistic regressions and qualitative interviews to explain variation in NGO engagement with climate issues.

Table 1

| Research methods | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Qualitative method | 26 (65.0%) |

| Quantitative method | 8 (20.0%) |

| Mixed method | 6 (15.0%) |

Distribution of research methods.

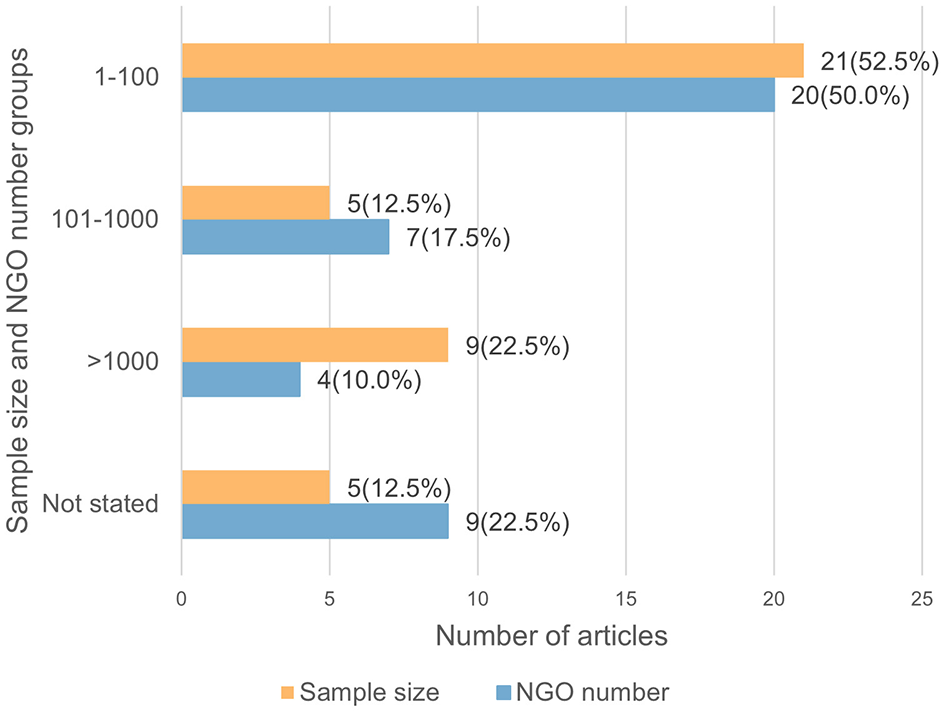

Respecting sample size (Figure 5), 52.5% of the reviewed studies utilized a sample size of 100 or fewer, most of which were actually smaller than 10. This could be due to the frequent use of qualitative methods, such as case study, comparative qualitative study, and process tracing, which prioritize in-depth understanding based on a smaller group of participants rather than broad generalizability. For example, Lück et al. (2016) undertook three thorough case studies on COP 16 held in Cacun (2010), COP 18 held in Doha (2012), and COP 19 held in Warsaw (2013), to examine the interplay between environmental NGOs and journalists in the coproduction networks. Conversely, a small proportion of the studies (22.5%) examined sample sizes over 1,000, leveraging big data to create new datasets for their research. For instance, Koliev et al. (2023, 2024) used natural processing language (NPL) to compile a climate shaming dataset of 2295 environmental NGOs in 176 countries.

Figure 5

Distribution of sample size and NGO number.

Similar to sample size, most studies (50.0%) analyzed fewer than 100 NGOs (Figure 5). However, the number of NGOs considered did not always match up with the sample size. The second-largest group of studies (17.5%) examined between 101 and 1,000 NGOs. This discrepancy may partly reflect cases where NGOs were not the primary unit of analysis, or where samples included other entities such as interviewees (Luhtakallio et al., 2022; Szarka, 2014), development projects (Davila et al., 2024), and country-diad-year statistics (Böhmelt et al., 2014). In addition, 12.5% of studies did not specify their sample size while a higher proportion (22.5%) failed to report how many NGOs were examined in their studies. These reporting omissions may reduce the transparency of existing research and complicate cross-study comparisons.

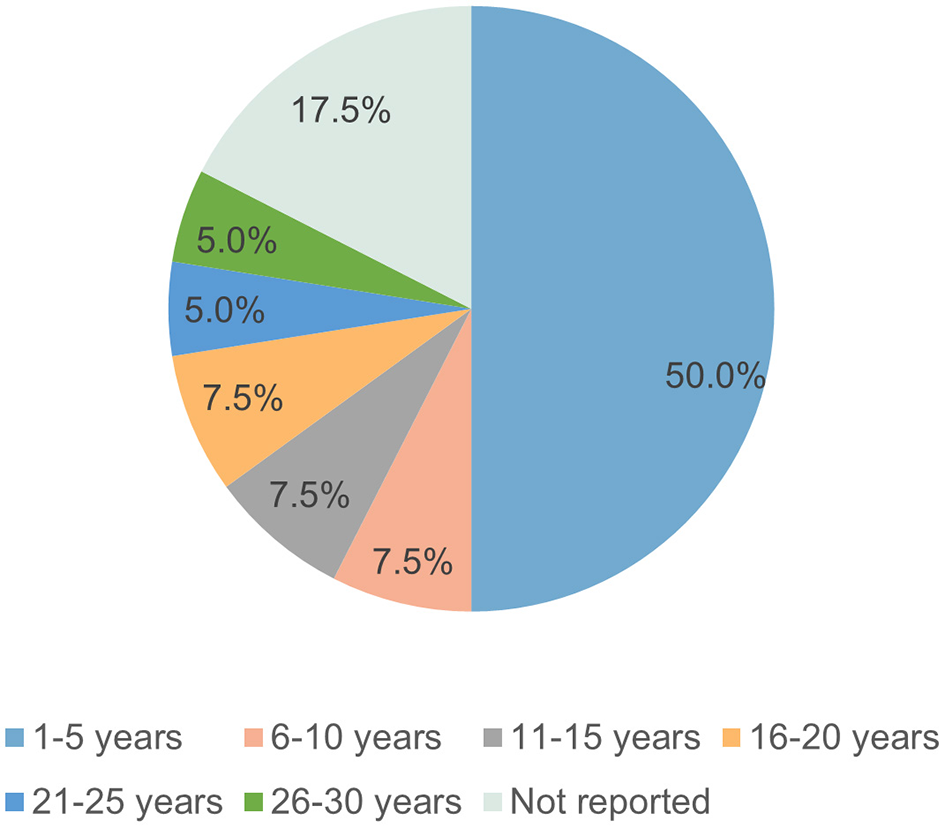

As for the study length (Figure 6), most studies (57.5%) were based on data spanning no more than a decade. Among them half of the studies (50%) covered 5 years or less while a further 7.5% addressed periods of 6–10 years. For example, Laestadius et al. (2014, 2016) conducted interviews with NGO staff from December 2011 to September 2012, to explore factors that shape NGOs' advocacy against meat consumption, given its significant impact on climate change. In contrast, 25.0% of the studies relied on data spanning over a decade, including 7.5% covering 11–15 years, 7.5% covering 16–20 years, 5.0% covering 21–25 years, and 5.0% covering 26–30 years. For example, Simpson and Smits (2018) examined how ENGOs influenced energy and climate security transitions in illiberal political environments across three decades from 1988 to 2018.

Figure 6

Proportion of study length distribution.

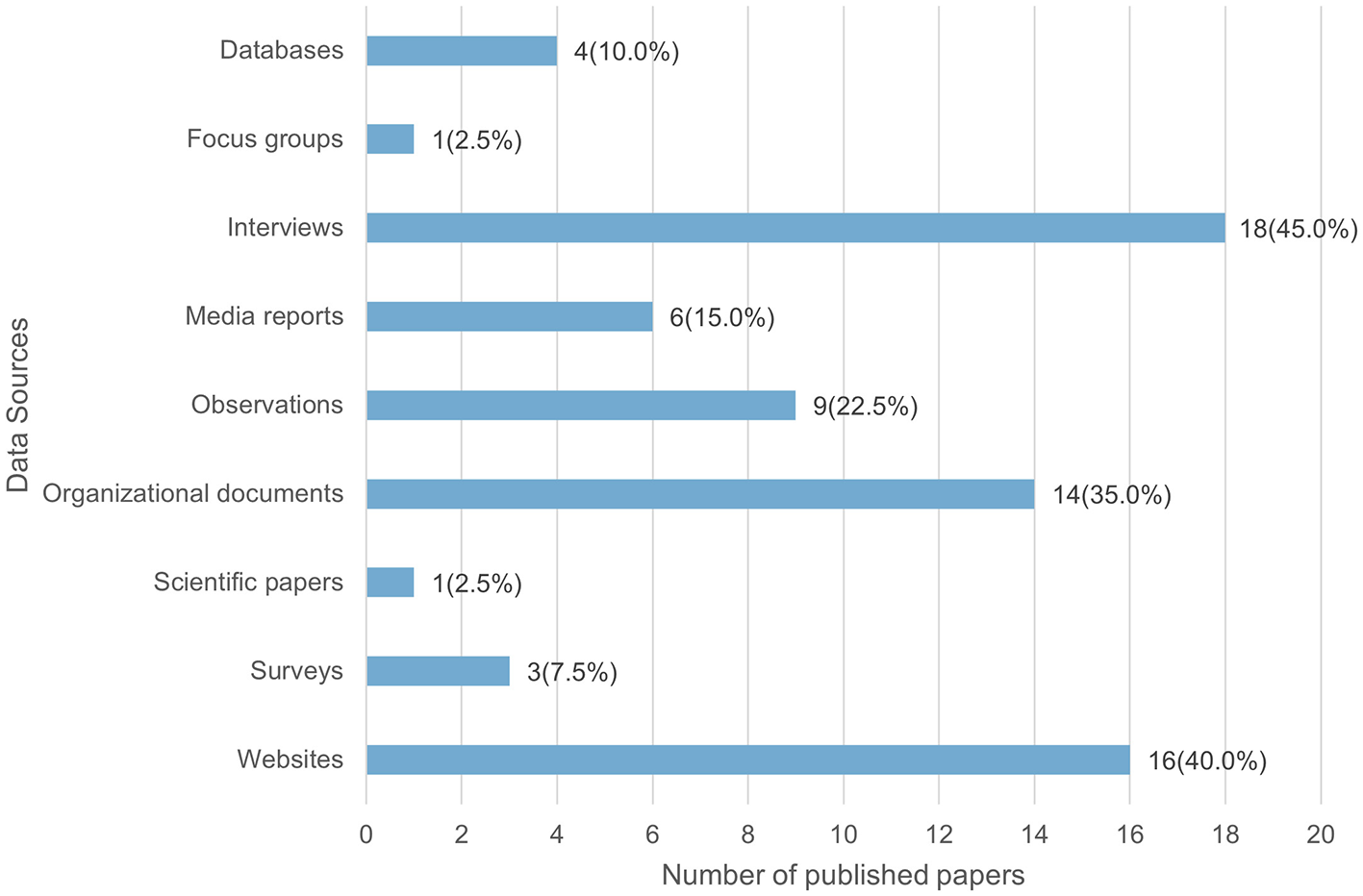

With regard to data collection (Figure 7), interviews were the most frequently used data sources (45.0%), followed by organizational websites (40.0%), organizational documents (35.0%), and observation (22.5%). Though less common, media reports (15.0%) and databases (10.0%) were also important data sources in the reviewed studies. It should be noted that a vast majority of the studies employed multiple data sources. For example, McGregor et al. (2018) collected data from Intended Nationally Determined Contributions, NGO websites, email correspondence with NGO staff and media reports, to explore how local NGOs in Climate Vulnerable Forum member countries created new knowledge and understanding and contributed to climate adaptation action within the broader context of global climate governance.

Figure 7

Distribution of data collection methods.

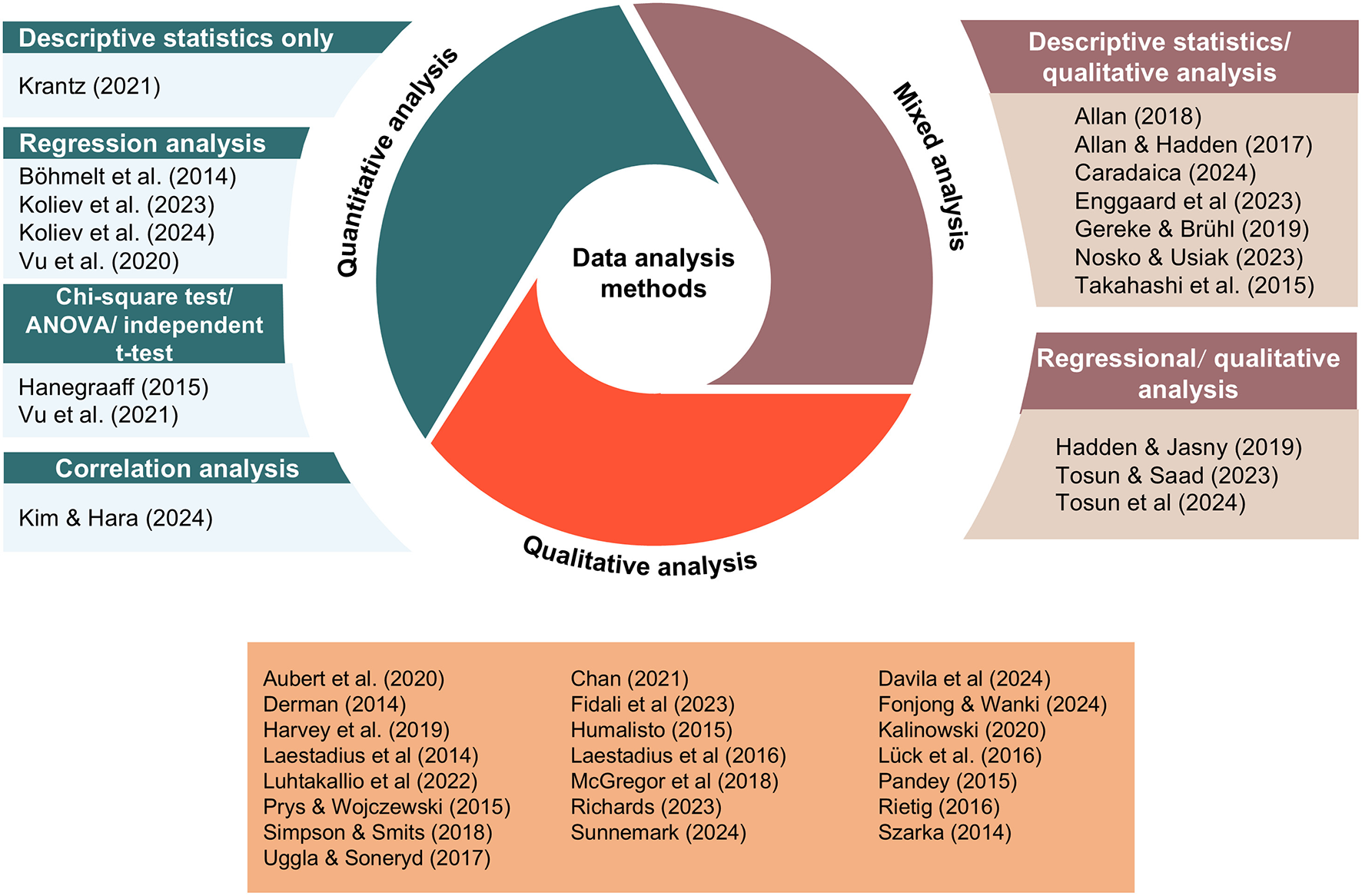

As regards the data analysis methods (Table 2), qualitative techniques were the predominant approach, employed in 80% of the studies while quantitative analysis methods were also used in 45.0% of the cases. It should be noted that these percentages are not mutually exclusive, as 10 studies (25.0%) adopted a mixed-method that combined both qualitative and quantitative techniques (Figure 8). Among studies that applied quantitative analysis methods, inferential statistics (25.0%) were slightly common than descriptive measures (20.0%), with regression the most frequently employed technique.

Table 2

| Data analysis methods | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Qualitative analysis | 32 (80.0%) |

| Regression analysis | 7 (17.5%) |

| Correlation analysis | 1 (2.5%) |

| Chi-square test/ANOVA test/independent t-test | 2 (5.0%) |

| Descriptive statisticsa | 8 (20.0%) |

Distribution of data analysis methods.

aStudies that only resorted to descriptive statistics when conducting quantitative analysis were counted.

Figure 8

Distribution of data analysis methods.

3.4 Categories and roles of NGOs

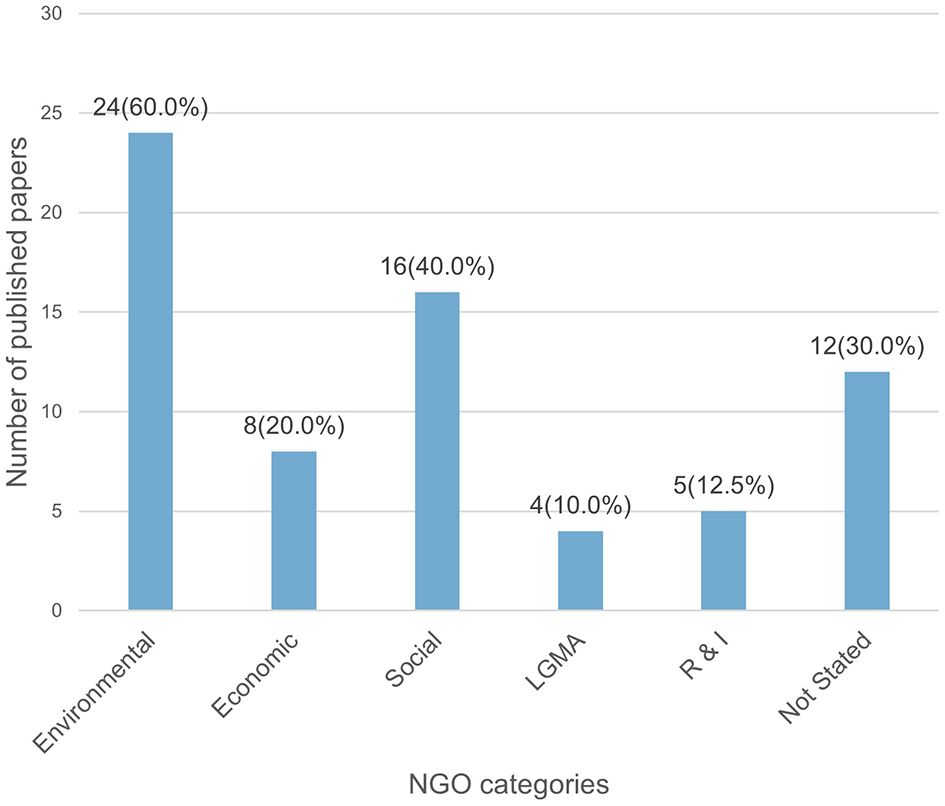

Among all five categories (Figure 9), environmental NGOs (60.0%) were the most involved in global climate action, followed by social NGOs (40.0%), economic NGOs (20.0%), R & I NGOs (12.5%), and LGMA (10.0%). The dominance of environmental NGOs was a logical finding, in that they often lead advocacy efforts, highlighting the urgency of climate change issues and influencing policymakers through scientific research and grassroots mobilization (Farid, 2019; Partelow et al., 2020). Social NGOs constituted the second largest group in the area of global climate action, implying a focus on inclusiveness, equity, and social justice within climate-related discussions (Clarke and de Cruz, 2015; Gereke and Brühl, 2019). This widening scope suggests that climate action is no longer confined to environmental expertise alone but is increasingly integrated into broader social agendas.

Figure 9

Distribution of NGO categories.

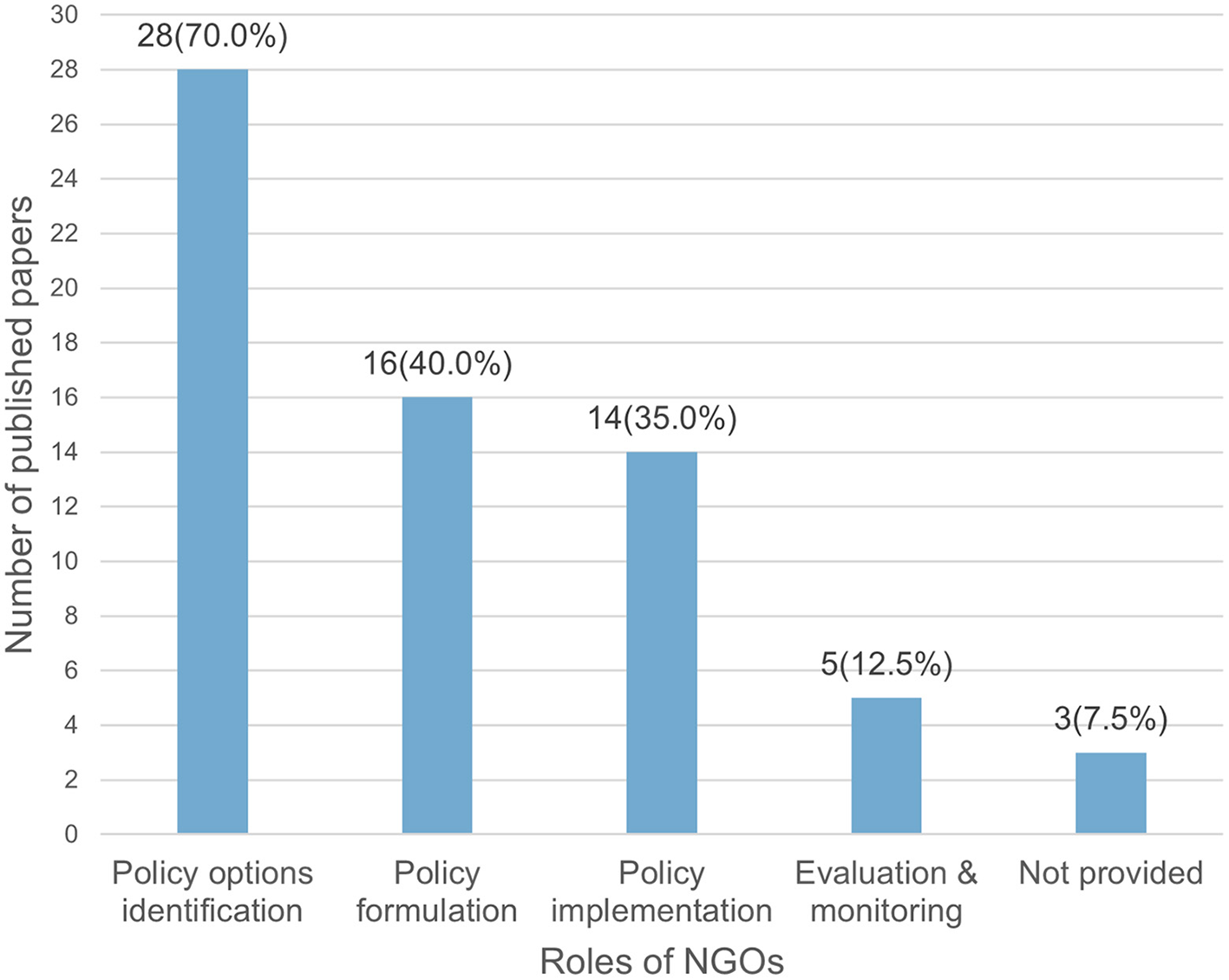

In terms of the roles that NGOs played in global climate governance, their activities are concentrated in the early policy stages, notably option-identification and formulation, while their engagement in later stages, such as evaluation and monitoring, remains comparatively limited. The majority of the studies (70.0%) revealed NGO involvement in identifying policy options, like issue-framing and lobbying (Figure 10). For example, Allan and Hadden (2017) investigated how a strategy shift among NGOs to justice-based framing enhanced their mobilization effects, thereby bolstering their influence on global governance outcomes. The second most frequently identified role, observed in 40.0% of the reviewed studies, was related to policy formulation. In this capacity, NGOs might participate in national delegations (Böhmelt et al., 2014) or assist governments to prepare for NDC reports (Allan, 2018). Thirdly, NGOs were also involved in policy implementation (35.0%). For example, Harvey et al. (2019) explored how NGOs contributed to data collection, technical analysis, and local engagement within the climate services sector in sub-Saharan Africa. Lastly, NGOs were also shown to have played a part in policy evaluation and monitoring (12.5%). One such example is found in Richards's (2023) study, in which the Oakland Institute ran a shocking investigative exposé to uncover the devastating impact of plantations on both local communities and the environment. This imbalance is likely indicative of NGOs' comparative advantages in advocacy and framing, alongside structural barriers to sustained involvement in long-term oversight.

Figure 10

Distribution of NGO roles.

3.5 NGO strategies

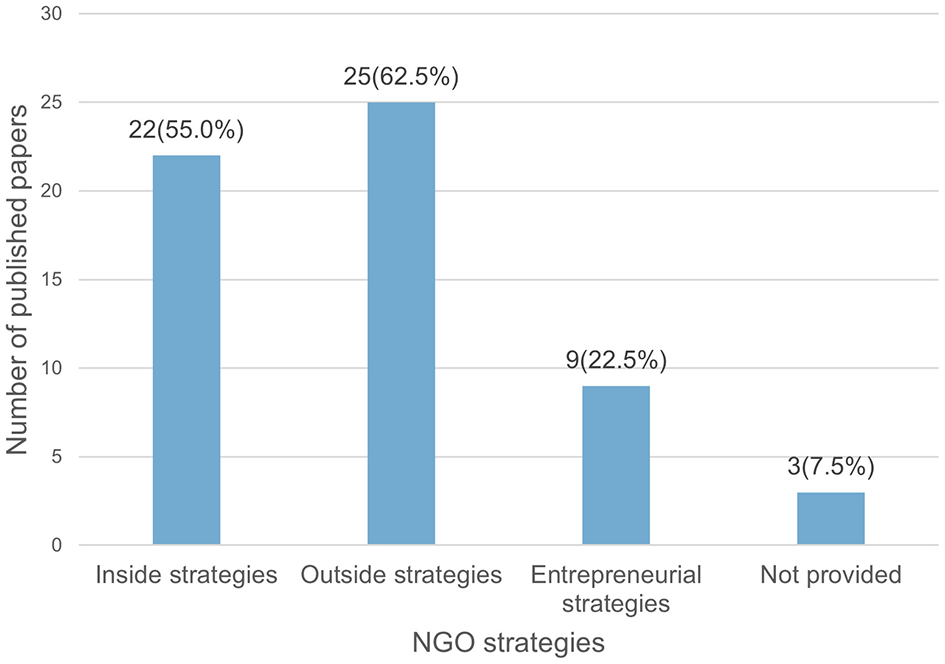

Among the three types of NGO strategies, outside strategies (62.5%) were adopted more often than inside strategies (55.0%; Figure 11). Outside strategies mainly focus on pressuring the government into action or inaction, through climate activism, naming and shaming, monitoring the actions of national and international institutions. One such example was Koliev et al.'s (2023) inquiry into how environmental NGOs chose their targets for climate shaming. In contrast, inside strategies involve direct engagement with decision-makers, including participating in policy-making processes, lobbying and partnering with government. For example, Chan (2021) analyzed how NGOs supported the operation of developing-country delegations by offering them specialized resources, training, and diplomatic advisory services. It indicates that NGOs are investing in direct policy engagement, seeking to shape climate governance not only from the margins but also from within the institutional arenas. Surprisingly, the entrepreneurial strategy was employed far less frequently, appearing in only 22.5% of the reviewed studies. Its relative infrequent use may be due to greater resource demands, risks, and specialized expertise required to devise and implement independent and innovative climate solutions.

Figure 11

Distribution of NGO strategies.

Additionally, while a significant proportion of the studies (55.0%) focused exclusively on a single strategy type, 45.0% of the studies revealed that NGOs pursued a combination of two or even three types of strategies in their climate governance efforts. They may leverage outside pressure to strengthen inside negotiation positions, complement advocacy with collaborative partnerships or take entrepreneurial climate action while shaping policy. For example, NGOs collaborated not only with government and IGOs but also with other NGOs to deliver food aid in Lake Chad Basin (Fonjong and Wanki, 2024). This hybrid-strategy approach is a logical finding, as NGOs diversify their tactics to navigate shifting political opportunities and resource constraints.

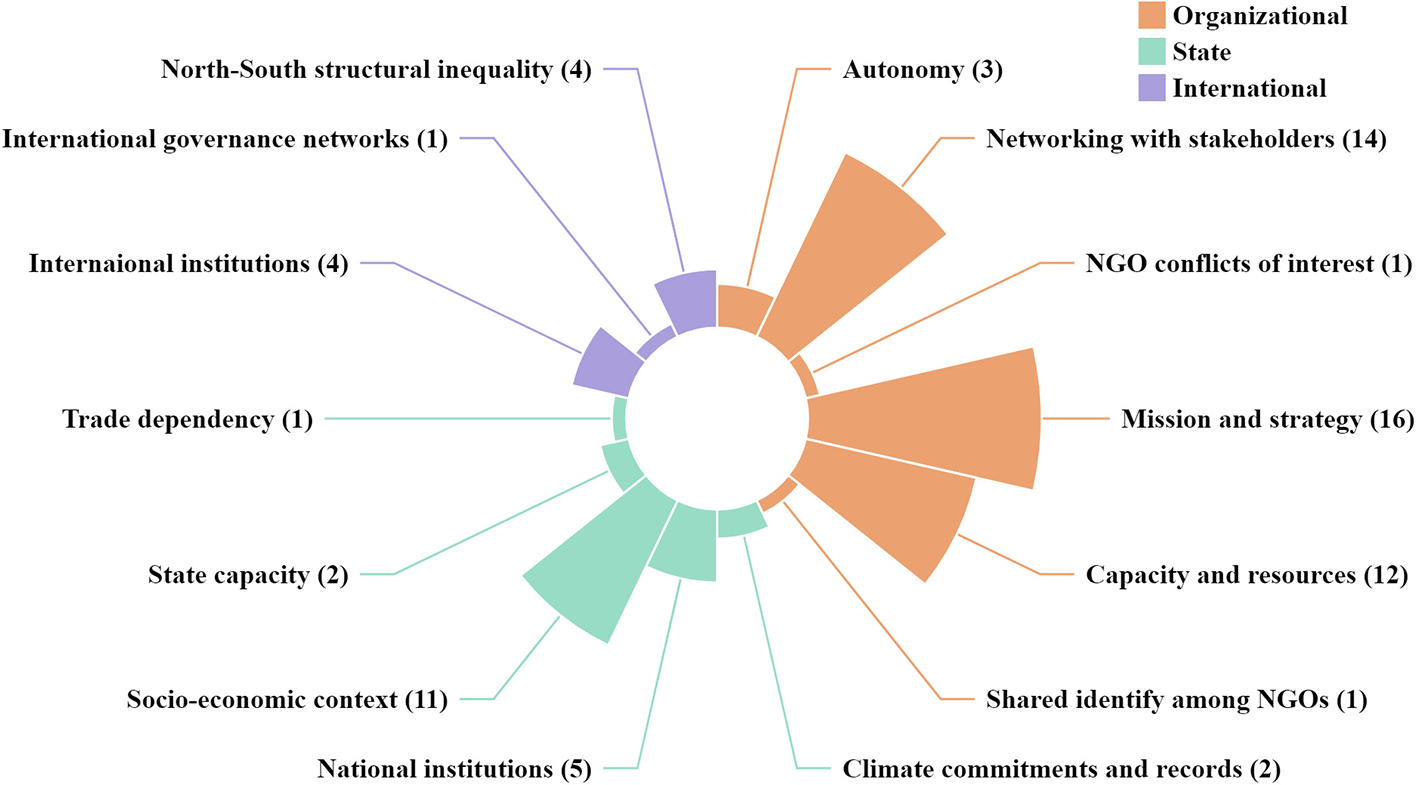

3.6 Factors influencing NGO engagement

As is illustrated in Table 3, the reviewed studies primarily assess factors influencing NGO engagement at a single analytical level, with fewer examining them across multiple levels. More than half of the studies (52.5%) identified factors enabling or constraining NGOs' global climate action from the perspective of a single level, with the organizational-level factors being most frequently examined. For example, Caradaica (2024) found that NGOs with climate-orientated discourse and missions played a prominent role in the transition to new European climate hegemony. In contrast, 37.5% of the studies identified the impacting factors across two levels of analysis, while only one study assessed the motivations across three levels. An illustrative case is Derman's (2014) finding that while the political opportunity structure, involving national and international institutional factors, could influence the efficacy of NGO advocacy, NGOs' expertise and capacity were also a determining factor.

Table 3

| Levels of analysis | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| 1 level | 21 (52.5%) |

| 2 levels | 15 (37.5%) |

| 3 levels | 1 (2.5%) |

| Not provided | 3 (7.5%) |

Distribution of levels of analysis.

Furthermore, the present study also investigated the distribution of factors at each level of analysis (Figure 12). At the organizational level, the most reported factors were mission and strategy (16 studies) and networking with stakeholders (14 studies) and capacity and resources (14 studies). For example, in their analysis of the tactical choices of climate NGOs within transnational advocacy networks, Hadden and Jasny (2019) found that whether NGOs chose protest tactics was influenced by adjacent organizations instead of equivalent organizations. This focus suggests that strengthening internal capabilities remains a priority for enhancing NGO effectiveness. At the state level, the socio-economic context (11 studies) was the most frequently examined factor and national institutions (5 studies) were much less often identified. For example, Fidali et al. (2023) identified socio-economic factors hindering NGO climate action: complex donor processes and requirements, and inadequate recognition of local NGOs. On the international scale, North-South structural inequality (4 studies) and international institutions (4 studies) were most frequently identified as influencing factors. For example, Vu et al. (2021) identified significant North-South differences in NGO framing strategies while Kalinowski (2020) analyzed how international institutional innovation and constraints affected NGO involvement in the Green Climate Fund.

Figure 12

Detailed distribution of impacting factors by levels of analysis.

4 Discussion

This review sheds light on several patterns and debates regarding NGO engagement in global climate governance.

First of all, this field of NGO engagement in global climate governance has grown substantially. Rising publication trend corresponds with broader observations of NGOs' increasing visibility in global politics (Allan and Hadden, 2017; UNFCCC, 2024b). However, this expansion does not automatically translate into substantive influence as persistent institutional barriers, resource limitations, and legitimacy challenges constrain NGOs' ability to shape outcomes (Brombo, 2021; Cadag, 2025; Takahashi et al., 2015). Importantly, the disciplinary positioning of this literature reinforces certain blind spots. Most studies are published in environmental and governance studies journals rather than NGO-focused outlets, indicating that NGOs are usually framed as governance instruments rather than organizational actors with distinctive institutional logic. While such framing resonates with research on transnational advocacy (Hanegraaff, 2015), equitable climate finance (Prys and Wojczewski, 2015), and disaster risk reduction (Lassa, 2018), it sidelines insights from NGO scholarship on their internal structures, organizational dynamics and professionalization. Overall, this tension highlights that NGOs are increasingly visible in climate governance scholarship, yet current literature risks overstating NGO's external presence while neglecting their internal organizational realities.

The prevalence of materialist perspectives over ideational perspectives reflects a debate on material-ideational sources of power and influence in global environmental politics. Many studies tend to frame resources, institutional access, and structural asymmetries as drivers of NGO influence while other scholars stress framing, norms and discourse authority shape climate politics (Allan, 2018; Enggaard et al., 2023; Uggla and Soneryd, 2017). While NGOs derive authority through both channels, but most studies privilege one side. In practice, these dimensions are often interdependent: material resources condition the reach of discursive strategies, while effective framing can reshape institutional opportunities. This suggests that the two perspectives are not dichotomous but mutually reinforcing, echoing analytical eclecticism in world politics that integrate material and ideational insights.

The field remains dominated by qualitative research, privileging interpretive depth over generalizability. This resonates with Brass et al.'s (2018) findings on NGO studies in development and reflects broader methodological preferences in global environmental politics (Hochstetler and Laituri, 2014). While some studies have introduced quantitative approaches, including regression and correlation analyses of NGO climate action (Kim and Hara, 2024; Vu et al., 2020), these remain less common. Similarly, the scarcity of longitudinal studies, also observed in other areas of global governance, complicates efforts to assess how NGO influence evolves across time. More recently, computational techniques, such as natural language processing applied to climate shaming (Koliev et al., 2023, 2024), have begun to complement traditional case studies, showing how methodological approaches are diversifying, though still unevenly distributed.

With regard to their roles, NGOs are most active in agenda-setting and policy formulation, focusing less on policy implementation and monitoring. This aligns with transnational advocacy research that identifies NGOs as effective framers of issues (Allan and Hadden, 2017). In contrast, this pattern diverges from studies such as Haris et al. (2020), which found NGOs were more engaged in policy implementation, and monitoring. This discrepancy may stem from differences in scale and scope: their study concentrated only on several Southeast Asian countries, whereas this review covered the global scale. This suggests that conclusions about NGO roles are contingent on the scale of governance under examination, which may account for diverging findings across studies.

NGOs combine both outside and inside strategies. This convergence with Dellmuth and Tallberg (2017) affirms that NGOs rarely rely on a single repertoire. However, the preference over outside strategies in climate governance contrasts with Townsend et al.'s (2023) finding in the health arena where inside strategies seemed slightly more prevalent than outside strategies. This discrepancy indicates governance arenas condition NGOs' strategic choice, as climate governance often incentivizes public mobilization and discursive pressure, whereas health governance provides more institutionalized access points.

Finally, this review reveals divergent emphases on organizational-level versus structural-level determinants of NGO engagement, echoing long-standing agency—structure debates in political science. Some scholars stress organizational factors, such as mission and strategy, networking with stakeholders, and capacity and resources, as the main drivers of NGO action (Allan, 2018; Hadden and Jasny, 2019; Lück et al., 2016). Others emphasize structural conditions, highlighting how international political dynamics and national socio-economic and institutional contexts shape NGOs' room for maneuver (Koliev et al., 2024; McGregor et al., 2018; Vu et al., 2020). Although organizational determinants appear more frequently stressed, integrative accounts offer a more nuanced perspective. For instance, Enggaard et al. (2023) combines NGO agency with political opportunity structures to show that agency and structure are mutually constitutive rather than opposed.

5 Conclusion

By systematically synthesizing 40 empirical studies from 2014 to 2024, this review reveals clear patterns but also important imbalances in theoretical orientations, methodological approaches, and the coverage of different NGO roles and strategies.

These findings make several contributions to the current literature. First, it addresses a gap in the climate governance literature by providing one of the first systematic overviews dedicated specifically to NGOs at the global level. Second, it maps the dominant analytical tendencies in this field, showing how materialist perspectives and qualitative research designs continue to prevail, while ideational, relational, and mixed-method approaches remain underutilized. Third, it identifies cross-cutting patterns in NGO strategies and modes of engagement, offering a structured account that deepens our understanding of NGO climate action.

The review also carries practical implications. For policymakers, this study underscores the need to institutionalize mechanisms that enable NGOs to contribute expertise and legitimacy to global decision-making. For NGOs themselves, the findings point to the value of combining insider and outsider strategies while exploring entrepreneurial initiatives as complementary modes of influence. Overall, these insights enhance our understanding of NGOs as dynamic actors in climate governance and offer a starting point for more effective, inclusive, and sustainable responses to the climate crisis.

6 Limitations and future research

Despite its contributions, this review is subject to several limitations. First, while this study aims to include a comprehensive range of empirical studies on NGOs' global climate action, variations in paper quality and methodological rigor pose challenges for generalizability. As the body of literature expands, future studies should adopt stricter inclusion criteria to enhance the reliability of the findings. Second, the exclusive focus on global-level engagement may overlook important activities at national or local levels where climate action often unfolds with equal dynamism.

While these limitations define the scope of this review, the synthesis nonetheless points to broader gaps in the field that future research should address. Theoretically, the prevalence of materialist perspectives could be balanced by deeper engagement with ideational, relational, and historicist approaches, allowing for richer explanations of NGO strategies and influence. Methodologically, reliance on qualitative studies with small samples and short timeframes limits cumulative theorization; longitudinal designs, mixed-method approaches, and large-N datasets would provide more robust assessments of NGO influence and its evolution over time. Empirically, greater attention should be devoted to NGOs' roles in policy implementation, monitoring and evaluation, which remain relatively underexplored. Similarly, entrepreneurial strategies require further investigation to understand when and why NGOs pursue them, and how they interact with insider and outsider tactics.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

ZL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. MY: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. We utilized ChatGPT to improve clarity, and grammar. We take full responsibility for the research outcomes and writing.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Allan J. I. (2018). Seeking entry: discursive hooks and NGOs in global climate politics. Global Policy9, 560–569. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12586

2

Allan J. I. Hadden J. (2017). Exploring the framing power of NGOs in global climate politics. Env. Polit.26, 600–620. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2017.1319017

3

Anheier H. K. Toepler S. (2023). Nonprofit Organizations: Theory, Management, Policy, 3rd Edn. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429299681-2

4

Aubert P.-M. Ruat R. Treyer S. Rankovic A. (2020). Holding the ground. Alliances and defiances between scientists, policy-makers and civil society in the development of a voluntary initiative, the “4 per 1000: soils for food security and climate”. Environ. Sci. Policy113, 80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.008

5

Bäckstrand K. Kuyper J. Linnér B. Lövbrand E. (2017). Non-state actors in global climate governance: from Copenhagen to Paris and beyond. Environ. Politics26, 561–579. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2017.1327485

6

Barrington R. (2025). “Transparency International in the UK: integrity in campaigning,” in The Routledge Handbook of Anti-Corruption Research and Practice, eds. J. Pozsgai-Alvarez and R. Bratu (Routledge), 521–532. doi: 10.4324/9781003303275-37

7

Ben Youssef A. (2024). The role of NGOs in climate policies: the case of Tunisia. J. Econ. Behav. Org.220, 388–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2024.02.016

8

Böhmelt T. Koubi V. Bernauer T. (2014). Civil society participation in global governance: insights from climate politics. Eur. J. Polit. Res.53, 18–36. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12016

9

Brass J. N. Longhofer W. Robinson R. S. Schnable A. (2018). NGOs and international development: a review of thirty-five years of scholarship. World Dev.112, 136–149. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.07.016

10

Brombo P. (2021). “The interaction among populism, civil society organisations and European institutions,” in The Impact of Populism on European Institutions and Civil Society: Discourses, Practices, and Policies, eds. C. Ruzza, C. Berti, and P. Cossarini (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 219–242. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-73411-4_10

11

Cadag J. R. D. (2025). “Depoliticisation is disaster risk creation: insights into nongovernmental organisations' disaster prevention and humanitarian response in the Philippines,” in Depoliticising Humanitarian Action: Paradigms, Dilemmas, Resistance, eds. I. Desportes, A. Corbet, and A. Siddiqi (Abingdon: Routledge), 135–154. doi: 10.4324/9781003412410-11

12

Caradaica M. (2024). Civil society as the arena of the new European climate hegemony: a neo-Gramscian approach to European green transition. Civil Szemle21, 5–18. doi: 10.62560/csz.2024.02.01

13

Chan N. (2021). Beyond delegation size: developing country negotiating capacity and NGO ‘support' in international climate negotiations. Int. Environ. Agreements Polit. Law Econ.21, 201–217. doi: 10.1007/s10784-020-09513-4

14

Clarke M. de Cruz I. (2015). A climate-compatible approach to development practice by international humanitarian NGOs. Disasters39, s19–s34. doi: 10.1111/disa.12110

15

Davila F. Jacobs B. Nadeem F. Kelly R. Kurimoto N. (2024). Finding climate smart agriculture in civil-society initiatives. Mitigation Adaptation Strategies Global Change29:14. doi: 10.1007/s11027-024-10108-6

16

Dellmuth L. M. Tallberg J. (2017). Advocacy strategies in global governance: inside versus outside lobbying. Polit. Stud.65, 705–723. doi: 10.1177/0032321716684356

17

Derman B. B. (2014). Climate governance, justice, and transnational civil society. Clim. Policy14, 23–41. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2014.849492

18

Dupuy K. E. Ron J. Prakash A. (2015). Who survived? Ethiopia's regulatory crackdown on foreign-funded NGOs. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ.22, 419–456. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2014.903854

19

Enggaard T. R. Hedegaard Isfeldt A. S. Kvist Møller A. H. Carlsen H. B. Albris K. Blok A. (2023). Inter-risk framing contests: the politics of issue attention among Scandinavian climate NGOs during the coronavirus pandemic. Sociology57, 1467–1490. doi: 10.1177/00380385221150379

20

Farid M. (2019). Advocacy in action: China's grassroots NGOs as catalysts for policy innovation. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev.54, 528–549. doi: 10.1007/s12116-019-09292-3

21

Fidali K. Toamua O. Aquillah H. Lomaloma S. Mauriasi P. R. Nasiu S. et al . (2023). Can civil society organizations and faith-based organizations in Fiji, Samoa, and Solomon Islands access climate finance?Dev. Policy Rev.41:e12728. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12728

22

Fonjong L. Wanki J. E. (2024). Unpacking the food security crisis in the ecologically fragile and conflict-ridden Lake Chad Basin: interrogating NGOs' response to the climate change-security nexus. J. Environ. Dev.33, 370–388. doi: 10.1177/10704965241231550

23

Gereke M. Brühl T. (2019). Unpacking the unequal representation of Northern and Southern NGOs in international climate change politics. Third World Q.40, 870–889. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2019.1596023

24

Hadden J. Jasny L. (2019). The power of peers: how transnational advocacy networks shape NGO strategies on climate change. Br. J. Polit. Sci.49, 637–659. doi: 10.1017/S0007123416000582

25

Hanegraaff M. (2015). Transnational advocacy over time: business and NGO mobilization at UN climate summits. Global Environ. Polit.15, 83–104. doi: 10.1162/GLEP_a_00273

26

Haris S. M. Mustafa F. B. Raja Ariffin R. N. (2020). Systematic literature review of climate change governance activities of environmental nongovernmental organizations in Southeast Asia. Environ. Manage.66, 816–825. doi: 10.1007/s00267-020-01355-9

27

Harvey B. Jones L. Cochrane L. Singh R. (2019). The evolving landscape of climate services in sub-Saharan Africa: what roles have NGOs played?Clim. Change157, 81–98. doi: 10.1007/s10584-019-02410-z

28

Henry L. A. Sundstrom L. M. Winston C. Bala-Miller P. (2019). NGO participation in global governance institutions: international and domestic drivers of engagement. Interest Groups Advocacy8, 291–332. doi: 10.1057/s41309-019-00066-9

29

Hochstetler K. Laituri M. (2014). “Methods in international environmental politics,” in Advances in International Environmental Politics, eds. M. M. Betsill, K. Hochstetler, and D. Stevis (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 78–104. doi: 10.1057/9781137338976_4

30

Ibones K. A. Enero J. V. Jore J. S. Mamhot V. I. Matheu C. M. Pacaldo H. B. B. et al . (2024). Enabling role of civil society organizations (CSOs) in local environmental management in the Philippines: a systematic review. J. Civil Soc.20, 359–379. doi: 10.1080/17448689.2024.2381826

31

Kalinowski T. (2020). Institutional innovations and their challenges in the Green Climate Fund: country ownership, civil society participation and private sector engagement. Sustainability12:8827. doi: 10.3390/su12218827

32

Keohane R. Victor D. (2011). The regime complex for climate change. Perspect. Polit.9, 7–23. doi: 10.1017/S1537592710004068

33

Kim E. Hara N. (2024). Identifying different semantic features of public engagement with climate change NGOs using semantic network analysis. Sustainability16:1438. doi: 10.3390/su16041438

34

Koliev F. Duit A. Park B. (2024). The impact of INGO climate shaming on national laws. Int. Interact.50, 94–120. doi: 10.1080/03050629.2023.2279627

35

Koliev F. Park B. Duit A. (2023). Climate shaming: explaining environmental NGOs targeting practices. Clim. Policy23, 845–858. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2022.2143315

36

Krantz D. (2021). COP and the cloth: quantitatively and normatively assessing religious NGO participation at the Conference of Parties to the United Nations framework convention on climate change. Science3:24. doi: 10.3390/sci3020024

37

Laestadius L. I. Neff R. A. Barry C. L. Frattaroli S. (2014). “We don't tell people what to do”: an examination of the factors influencing NGO decisions to campaign for reduced meat consumption in light of climate change. Global Environ. Change29, 32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.08.001

38

Laestadius L. I. Neff R. A. Barry C. L. Frattaroli S. (2016). No meat, less meat, or better meat: understanding NGO messaging choices intended to alter meat consumption in light of climate change. Environ. Commun.10, 84–103. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.981561

39

Lassa J. A. (2018). “Roles of non-government organizations in disaster risk reduction,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Natural Hazard Science (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Available online at: https://oxfordre.com/naturalhazardscience/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.001.0001/acrefore-9780199389407-e-45 (Accessed August 11, 2025).

40

Lencastre M. P. A. Vidal D. G. Lopes H. S. Curado M. J. (2023). Biophilia inpieces: critical approach of a general concept. Environ. Soc. Psychol.8:1869. doi: 10.54517/esp.v8i3.1869

41

Liu L. Wang P. Wu T. (2017). The role of nongovernmental organizations in China's climate change governance. WIREs Clim. Change8:e483. doi: 10.1002/wcc.483

42

Lopes H. S. Silva P. F. Pinto B. G. Cuevas P. D. Ribeiro V. Remoaldo P. (2025). Urban heat stress in the context of socioeconomic and environmental challenges: heat risk analysis and online surveys in northwestern Portugal. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct.120:105384. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2025.105384

43

Lu Y. Wang Y. Zhan C. (2023). Building rural community disaster resilience in developing countries: insights from a Chinese NGO's Safe Rural Community programme. Disasters47, 1090–1117. doi: 10.1111/disa.12586

44

Lück J. Wozniak A. Wessler H. (2016). Networks of coproduction: how journalists and environmental NGOs create common interpretations of the UN Climate Change Conferences. Int. J. Press Polit.21, 25–47. doi: 10.1177/1940161215612204

45

Luhtakallio E. Ylä-Anttila T. Lounela A. (2022). How do civil society organizations influence climate change politics? Evidence from India, Indonesia, and Finland. J. Civil Soc.18, 410–432. doi: 10.1080/17448689.2022.2164026

46

Marquardt J. Bäckstrand K. (2022). “Democracy beyond the state: non-state actors and the legitimacy of climate governance,” in The Routledge Handbook of Democracy and Sustainability, eds. B. Bornemann, H. Knappe, and P. Nanz (Abingdon: Routledge), 237–253. doi: 10.4324/9780429024085-21

47

McCourt D. M. (2016). Practice theory and relationalism as the new constructivism. Int. Stud. Q.60, 475–485. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqw036

48

McGregor I. Yerbury H. Shahid A. (2018). The voices of local NGOs in climate change issues: examples from climate vulnerable nations. Cosmopolitan Civil Soc. Interdiscipl. J.10, 63–80. doi: 10.5130/ccs.v10.i3.6019

49

Middeldorp N. Le Billon P. (2019). Deadly environmental governance: authoritarianism, eco-populism, and the repression of environmental and land defenders. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geograph.109, 324–337. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1530586

50

Moher D. Liberati A. Tetzlaff J. Altman D. G. PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med.6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

51

Nasiritousi N. (2019). “NGOs and the environment,” in Routledge Handbook of NGOs and International Relations, ed. T. Davies (Abingdon: Routledge), 329–342. doi: 10.4324/9781315268927-24

52

Pandey C. L. (2015). Managing climate change: shifting roles for NGOs in the climate negotiations. Environ. Values24, 799–824. doi: 10.3197/096327115X14420732702734

53

Partelow S. Winkler K. J. Thaler G. M. (2020). Environmental non-governmental organizations and global environmental discourse. PLoS ONE15:e0232945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232945

54

Prys M. Wojczewski T. (2015). Rising powers, NGOs and North–South relations in global climate governance: the case of climate finance. Politikon42, 93–111. doi: 10.1080/02589346.2015.1005794

55

Raustiala K. (2020). “NGOs in international treaty-making,” in The Oxford Guide to Treaties, 2nd Edn., eds. D. B. Hollis (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 173–198. doi: 10.1093/law/9780198848349.003.0009

56

Richards I. (2023). Capturing the environment, security, and development nexus: intergovernmental and NGO programming during the climate crisis. Confl. Secur. Dev.23, 425–445. doi: 10.1080/14678802.2023.2211019

57

Robinson P. Lowe J. (2015). Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health39, 103–103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

58

Rosenau J. N. (1999). “Toward an ontology for global governance,” in Approaches to Global Governance Theory, eds. M. Hewson and T. J. Sinclair (Albany, NY: SUNY Press), 287–301.

59

Sharma R. (2023). Civil society organizations' institutional climate capacity for community-based conservation projects: characteristics, factors, and issues. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain.5:100218. doi: 10.1016/j.crsust.2023.100218

60

Simpson A. Smits M. (2018). Transitions to energy and climate security in Southeast Asia? Civil society encounters with illiberalism in Thailand and Myanmar. Soc. Nat. Resourc.31, 580–598. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2017.1413720

61

Singer J. D. (1961). The level-of-analysis problem in international relations. World Polit.14, 77–92. doi: 10.2307/2009557

62

Sørensen G. (2008). The case for combining material forces and ideas in the study of IR. Euro. J. Int. Relat.14, 5–32. doi: 10.1177/1354066107087768

63

Steinberg G. Wertman B. (2018). Value clash: civil society, foreign funding, and national sovereignty. Global Govern.24, 1–10. doi: 10.1163/19426720-02401001

64

Sunnemark L. (2024). Articulating post-apocalyptic environmentalism: global civil society and the struggle for anti-colonial climate politics in the climate movement. Globalizations21, 839–856. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2023.2288405

65

Szarka J. (2014). Non-governmental organizations and citizen action on climate change: strategies, rationales and practices. Open Polit. Sci. J.7, 1–8. doi: 10.2174/1874949601407010001

66

Takahashi B. Edwards G. Roberts J. T. Duan R. (2015). Exploring the use of online platforms for climate change policy and public engagement by NGOs in Latin America. Environ. Commun.9, 228–247. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.1001764

67

Tosun J. Levario Saad E. (2023). Adapted to climate change? Issue portfolios of environmental nongovernmental organizations in the Americas. Nonprofit Voluntary Sector Q.52, 917–951. doi: 10.1177/08997640221146962

68

Tosun J. Levario Saad E. Gutiérrez D. (2024). Participating in polycentric climate governance: the partnership choices of Latin American NGOs. Global Environ. Polit.24, 144–167. doi: 10.1162/glep_a_00752

69

Townsend B. Johnson T. D. Ralston R. Cullerton K. Martin J. Collin J. et al . (2023). A framework of NGO inside and outside strategies in the commercial determinants of health: findings from a narrative review. Global Health19:74. doi: 10.1186/s12992-023-00978-x

70

Tucker A. (2021). Historicism now: historiographic ontology, epistemology and methodology out of bounds. J. Philos. Hist.16, 92–121. doi: 10.1163/18722636-12341458

71

Uggla Y. Soneryd L. (2017). Green governmentality, responsibilization, and resistance: international ENGOs' issue framings of future energy supply and climate change mitigation. Socijalna Ekologija26, 87–104. doi: 10.17234/SocEkol.26.3.2

72

UNFCCC (2022). Funding Arrangements for Responding to Loss and Damage Associated with the Adverse Effects of Climate Change, Including a Focus on Addressing Loss and Damage (No. Decision 2/CP.27). Available online at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cp2022_10a01_E.pdf (Accessed August 12, 2025).

73

UNFCCC (2023). Why the Global Stocktake is Important for Climate Action this Decade. Available online at: https://unfccc.int/topics/global-stocktake/about-the-global-stocktake/why-the-global-stocktake-is-important-for-climate-action-this-decade (Accessed August 12, 2025).

74

UNFCCC (2024a). Report of the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage and Guidance to the Fund (No. Decision 5/CP.29). UNFCCC. Available online at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2024_17a02_adv.pdf (Accessed August 12, 2025).

75

UNFCCC (2024b). Statistics on Admission. Available online at: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/parties-non-party-stakeholders/non-party-stakeholders/statistics#Statistics-on-admission (Accessed March 28, 2025).

76

UNFCCC Secretariat (2023). Constituencies and You. Available online at: https://unfccc.int/documents/36933 (Accessed January 2, 2025).

77

Vu H. T. Blomberg M. Seo H. Liu Y. Shayesteh F. Do H. V. (2021). Social media and environmental activism: framing climate change on Facebook by global NGOs. Sci. Commun.43, 91–115. doi: 10.1177/1075547020971644

78

Vu H. T. Do H. V. Seo H. Liu Y. (2020). Who leads the conversation on climate change?: a study of a global network of NGOs on Twitter. Environ. Commun.14, 450–464. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2019.1687099

79

Wu Q. Smits M. Zhu A. L. (2024). Strategic transparency under authoritarian environmentalism: information disclosure and the role of environmental NGOs in China's national emission trading scheme. Clim. Policy1–20. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2024.2386380

80

Zhao B. (2024). Granting legitimacy from non-state actor deliberation: an example of women's groups at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Environ. Policy Govern.34, 236–255. doi: 10.1002/eet.2074

Summary

Keywords

NGOs, global climate governance, climate change, role, strategy, systematic review

Citation

Li Z and Yaakop MR (2025) Engaging non-governmental organizations in global climate governance: a systematic review of journal publications from 2014 to 2024. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1604680. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1604680

Received

02 April 2025

Accepted

17 September 2025

Published

07 October 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Diogo Guedes Vidal, Universidade Aberta, Portugal

Reviewed by

Hélder Lopes, University of Minho, Portugal; Emilio José Medrano-Sánchez, Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola S.R.L, Peru

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Li and Yaakop.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhidan Li, p116857@siswa.ukm.edu.my

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.