- Department of International Relations, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, United States

The juxtaposition of “us” the people vs. “them” the elites and the demonization of outsiders have been the recurring themes across the post-Soviet space, from opposition party programs to the political rhetoric of chief executives. Is populism, often defined as a manifestation of nativism, anti-elitism, and xenophobia in party politics, social movements, policy, and leadership styles, a useful concept for the study of post-Soviet politics? To answer this question, I trace a range political manifestations of populism starting with the early years of transition, during the regime breakdowns, in participatory autocracies, and under the consolidating repressive dictatorships. A populist syndrome appears to be most pronounced in the context of democratic backsliding, contentious politics, and unconsolidated autocracies. As the post-Soviet autocratic regimes consolidate restrictive and non-participatory mechanisms of societal control (dominant parties, centralized propaganda machines, and repressive apparatus), populist tactics become less prevalent and populism as a concept describing elements of political life becomes more problematic.

1 Introduction

The rise of extreme-right politics around the world has brought heightened attention to the concept of populism. It has been called “the new big thing” in Western politics (Giraudi, 2018). Central Eastern Europe (CEE) and countries of the former Soviet Union had been part of the populist resurgence (Madlovics and Magyar, 2021). The post-communist political transitions had been punctuated by the rise of populist parties, movements, and leaders–the trend uniting the East European and post-Soviet transitional experiences. Then the East European and post-Soviet trends parted in the mid 2000s. Eastern Europe (including the post-Soviet Baltic states) consolidated democratic contestation and integrated with the EU, while most post-Soviet states consolidated their autocracies. All other former Soviet states remaining on the democratic trajectories experience at least one episode of democratic backsliding. The resurgence of nationalism and anti-liberalism had brought the populist and euro-skeptic forces to power in Eastern Europe. Increasingly nationalist and anti-Western positions of Russia and other post-Soviet countries invited scholars to draw parallels between the right-wing populist resurgence in Europe's liberal democracies and mounting anti-liberalism, nativism, and nationalism of the post-Soviet space.1

In 2010, one scholar of Russian politics observed that “…populism embraced the whole Russian political spectrum, including even those sectors which always positioned themselves as anti-populist (right-wing liberals, for example)” (Korgunuyuk, 2010, p. 243). Others have criticized this assessment arguing that although populist elements are abundant in political rhetoric, “clear and sustained instances of populism are a distinct rarity” in the post-Soviet space (March 2017, p. 214). According to this latter position, the major reason for this rarity of true populism, defined by a set of principles of popular sovereignty, anti-elitism, and messianic leadership, is the post-Soviet deficiency of truly participatory pluralist politics.2 In fact, conceptualizations of populism routinely situate it in democratic institutions, political liberalism, and mass participation. Populism is seen as a threat to democracy, but do autocracies provide fertile breeding grounds for populist tendencies? As the post-Soviet autocrats crush independent political expression, destroy the organizational bases of civil society, and brutally persecute political dissent, do they resort to populist politics? Or do they abandon populism with its popular sovereignty, anti-elitism, nativism, and the “people's leader” messianism? Does the consolidation of autocratic political regimes promote or hinder populist movements, rhetoric, and policies?

The post-Soviet region presents the perfect setting for examining these questions for the following reasons. First, the region encompasses a very diverse set of socio-economic, cultural, political, and institutional conditions that act as confounding factors. Second, the region experienced a direct Russian rule. From the Soviet times it inherits a unique set of historical reference points (repression, industrialization, collectivization, and assimilation policies) that continue to shape various populist narratives on both the right and the left sides of the political spectrum. Although the post-Soviet societies share with the CEE countries many socialist legacies and post-communist manifestations of populism (e.g., Viktor Orban in Hungary, Robert Fico and his party Smer in Slovakia, and Law and Justice party in Poland), Russia's frequent and forceful meddling in their domestic politics sets this region apart from the CEE. Lastly, except for the Baltic states, all post-Soviet countries have had a recent experience with authoritarian rule and/or democratic backsliding. This makes them the prime case for examining connections between populism and authoritarianism.3

In this contribution to the special issue, I revisit the autocracy-populism connection by adopting a wider definition of populism than the one that led March (2017) to speak about limitations of populist appeal in post-Soviet politics. I trace different manifestations of populism in post-Soviet politics from the early 1990s to the present day. I investigate the relationship between autocracy and different ways in which populism manifests itself in the post-Soviet region. Instead of focusing on a specific political aspect of populism that applies to different scholarship domains or conceptual traditions, I consider a range of its “symptoms” that jointly amount to the “populist syndrome.”

This approach allows us to consider ideological, strategic, behavioral, and socio-cultural manifestations of populism. My descriptive analysis reveals that the region's populist parties, movements, policies, and rhetoric thrived in transitional political settings associated with political pluralism, some degree of elite contestation, elements of participatory (electoral) dynamics, and a fair degree of civil liberties (freedom of association, press, and religion). I further find that the rise of repression, effective silencing of political expression, and severe limitations on citizens political behavior closes off opportunities of populist political action both to the opposition and the ruling autocrats. My central argument is that in the post-Soviet space consolidation of repressive authoritarianism leads to the demise of populism, not the other way around. Populist popular mobilization had been instrumental in bringing a few anti-liberal post-Soviet strongmen to power, such as Japarov. In other cases, the nationalist, anti-elitist, and nativist ideologies effectively justified the consolidation of autocratic rule of former Communist bosses, such as Lukashenka, and their hand-picked successors, such as Putin. Without doubt, populism features prominently in the post-Soviet regime dynamics, yet when the anti-liberal agenda succeeds, the core defining elements of anti-elitism, popular sovereignty and mobilizational leadership lose their political appeal. Even though the post-Soviet dictatorships most recent past had been filled with multiple manifestations of populist movements, leaders, rhetoric, and policies, the success of the antiliberal agenda had defeated populism as mobilizational force and political strategy.

The article is organized as follows. I start by defining populism as a set of ideational, strategic, and socio-political manifestations. I review some of the most notable manifestations of populism across four distinct political domains: (1) the electoral arena where parties and ideology structure popular political participation; (2) the political leadership arena where political strategies help politicians secure and retain office; and (3) mass mobilization including electoral and protest behavior. My review of a variety of post-Soviet populist manifestations demonstrate organizational pluralism, participatory politics, and protection of (some) civil liberties are essential for the populist resurgence. I conclude that the evolution of Eurasian autocracies from economic liberalism and participatory (electoral) authoritarianism toward statist and non-participatory political arrangements has undermined the populist project. The final remarks situate the post-Soviet experience in the global resurgence of populism and speculate about its near and distant future.

2 The syndrome of populism

Populism is often defined as an empty ideology or irresponsible demagoguery of self-serving political leaders, opening this concept to a wide range of political phenomena characteristic of political organization, leadership, and mass behavior. Conceptually, populism has been defined as a “thin-centered” ideology (Mudde, 2004; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017), discourse (Laclau, 2005), leadership methods and instruments for wining and exercising political power (Weyland, 2001; Jansen, 2011; Weyland, 2017), and anti-institutional politics. In systematizing different conceptual traditions in the study of populism, Oxford Handbook of Populism identified the ideational (emphasis on ideology and political organization), strategic (emphasis on leadership and policies) and socio-cultural (emphasis on political performance and style) approaches. Although these traditions problematize different aspects of politics and see populism through different conceptual lenses, they all recognize anti-elitism, popular sovereignty, charismatic leadership, and demonization of variously defined “others” as the concept's defining qualitative characteristics.

In empirical analyses the term populism is often applied to political parties, ideologies, leaders, movements, mass communication, and political mobilization. Because populism manifests itself in a variety of political institutions, behaviors, and ideas (parties, leaders, ideologies) that are traditionally studied by the theoretically and methodologically diverse research traditions in political science and related disciplines, the choice of definition often restricts research to a specific substantive domain. Methodological and theoretical compartmentalization of substantive research domains may lead to overstating or underestimating the extent to which populism characterizes any given political context. The diametrically opposing assessments of post-Soviet populism found in Korgunuyuk (2010) and March (2017) is a good example of how such domain compartmentalization can lead to diametrically different assessments. Moreover, because most conceptions of populism recognize it as a “hollow,” open-ended, and situational phenomenon, populism is bound to have culture-specific manifestations making it harder for comparativists to identify its common-denominator defining features the that span regimes, political cultures, and political cleavage structures of various societies.

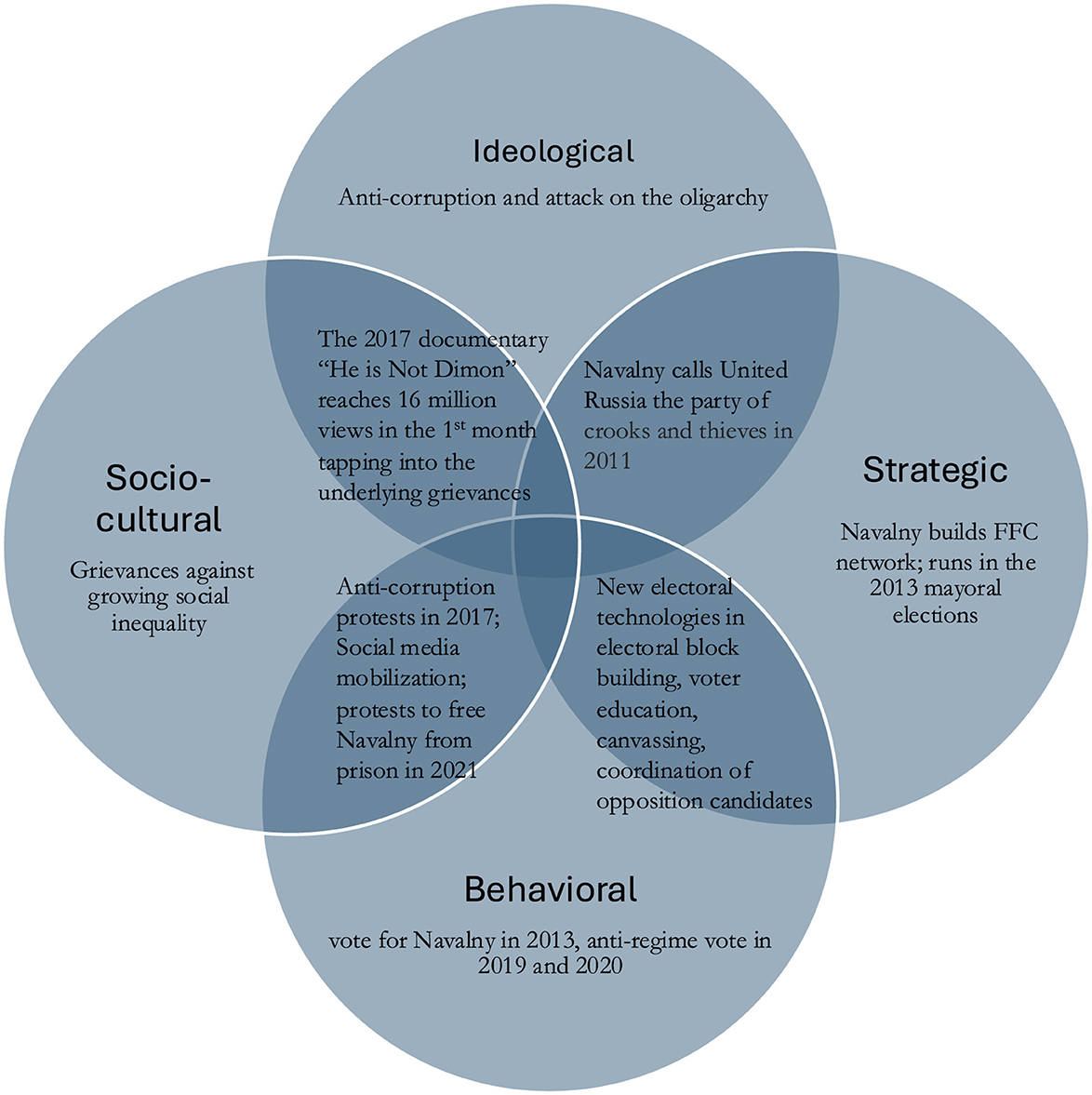

To recognize the complex and context-specific manifestations of populism I define it as “qualitative characteristic of political doctrines, parties, and movements, for which the opposition of the elite class and the masses is the key point of the agenda; it is also the method and style of mobilizing mass support aimed at supporting these forces and doctrines.” This definition is adopted from Makarenko (2018). I loosely follow Berlin et al. (1968) in summarizing the defining qualitative characteristics as follows: (1) idealization of the people often framed in terms of popular sovereignty; (2) anti-elitism and anti-establishment often extended to an attack on institutions (3) reverence for power often manifested in statism, militarism, longing for strong leader, party, or the state; (4) juxtaposition of the image of an organic society associated with idealization of the past and the hostile and disruptive “other” that manifest in xenophobia, racism, anti-Semitism, or conspiracy theories. This definition allows us to focus on a group of symptoms, or manifestations of the four above defining elements of populism in ideology, leadership, policies, and mass behavior. In what follows, I call all or any of the four substantive manifestations of populism across any four political domains a “syndrome of populism.” Figure 1 captures four overlapping political domains that cave up the space for populism's ideational, institutional, strategic, and behavioral manifestations.

Figure 1. Populist syndrome domains. The core intersection represents the holistic manifestation of populism, where ideology, strategy, behavior, and socio-cultural elements coalesce, exemplifying the multifaceted nature of populist movements, leadership, and parties.

Such a definition allows us to include examples as diverse as Lukashenka's4 leadership prior to 2020 anti-regime protests in Belarus; General Lebed's bid for Russian presidency; the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia led by Vladimir Zhirinovsky, a vocal nationalist and anti-democrat; mass mobilizations leading to “color” revolutions; Vladimir Putin's crusades against Russian oligarchs in the 2000s (Casula, 2013); the oligarch-founder of the Labor Party of Lithuania Viktor Uspaskich; Aleksey Navalny's anti-corruption movement that occasionally courted ultra-nationalist groups; Vladimir Zelensky's 2019 presidential campaign; and Sadyr Japarov's anti-establishment crusade in 2011–2013. This is not an exhaustive list of populist manifestations in the region, but just a snippet of a vast scope and variety of populist syndromes. By defining populism as a syndrome of symptoms that may manifest themselves jointly or in isolation in political discourse, organizations, leadership, and mass behavior I hope to avoid biased conclusions about its prevalence and limitations in the post-Soviet space.

3 Populist manifestations

Much of the post-Soviet populist politics have taken place in settings drastically divergent from both the liberal democracies of the capitalist West and the inequality-driven class politics of Latin America. To appreciate the situational and culturally embedded nature of post-Soviet populism one needs to recognize its deep historical roots in the region. Narodnichestvo, the nineteenth century naïve peasant-centered socialism of intellectuals, was the region's first “populist” movement (Morini, 2013). This movement was a product of the intellectual elite's critique of the Russian imperial autocracy with virtually no mass political following. The Soviet period had also seen some elements of populism, such as its ideology of popular sovereignty, Joseph Stalin's personality cult, and anti-elitism of Soviet egalitarianism (Brandenberger, 2010). Yet these features coexisted with elements largely seen as antithetical to populism: party leadership (as opposed to personal leadership), internationalism, and institutionalism.

The opening up of the public space by M. Gorbachev's glasnost' policy in the late 1980s and the collapse of the USSR gave rise to the populist electoral rhetoric and political organizations coalescing around charismatic personalities and ideologically diverse, yet people-centered programs. Through the “transitional” 1990s, populism was largely confined to the political opposition, with numerous examples of successful transformation of populist challengers to the mainstream presidents. While in power, many leaders had resorted to the populist governance: unrealistic promises had been enacted into government policies; nativist and anti-elite rhetoric was used to mobilize support for the incumbent governments, and lavish social spending often financed by natural resources helped maintain the stability of political regimes (Kuzio, 2010; Matsen et al., 2016). As governments discovered and perfected the populist tactics the opposition forces did not abandon the populist cause. Across various countries the opposition was able to channel social grievances into political crusades against corrupted elites, government institutions, and variously defined outsiders. The rest of the section surveys post-Soviet populism in ways it manifested itself in the following political domains: parties and ideology, leadership and governance, and mass mobilization.

4 Parties and ideologies

A plethora of political parties that came to contest popular elections in Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia since the early 1990s squarely fall into the populist category. Many parties formed to contest the initial democratic elections on both sides of political spectrum criticized the “anti-people” economic reforms and betrayals of national interests by self-serving politicians. Emblematically, the first party to be registered by Russia's ministry of justice after the collapse of the USSR was the right-wing populist Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR), a party that defied its name by being neither liberal nor democratic. Other right-wing populist parties include Russia' Rodina, founded in the mid-1990s, Ukraine's Svoboda formed in 1991, National Alliance formed to contest the 2010 Latvian elections, and Alliance of Patriots of Georgia (APG)5 founded in 2012. These parties capitalized on ultranationalist rhetoric, xenophobia, and attacks on minorities and migrants. Although forming at various stages of economic liberalization in different geopolitical contexts, these right-wing populist parties converged on embracing the statist economy, strong charismatic leaders, and confrontational stances in international politics. Both the anti-Western and anti-Russian populist stances framed foreign policy in terms of existential threats to the nation and made these claims an integral part of their domestic policy platforms.6

Post-Soviet populism is ideologically diverse and draws inspiration from a variety of nativist and universalist traditions. Ethnic nationalism had been the dominant mode for defining “the people.” Yet, it had not been the only way to separate “us” from “them.” Russia's All-National Union–a party successfully contesting regional elections in 1990–2011, for example, campaigned on pan-Orthodox Christian values. Its version of nationalism was based on religion instead of ethnic identity. The Party advanced a traditionalist critique of both Yeltsin and Putin's cultural and family policies on the ground that they were promoting or permitting homosexuality, abortions, smoking, and drinking.7 Not all right-wing populist parties cling to traditionalism though. A combination of traditionalism, nationalism, and some liberal values (such as economic liberalism) had been a characteristic feature of many post-Soviet populist platforms.

The Russian LDPR was founded by Vladimir Zhirinovsky, whose 1991 presidential nomination was nearly banned due to an insufficient number of voter signatures. Responding to accusations of being a Kremlin's electoral decoy, Zhirinovsky invested much effort in party-building, ultimately creating a long-lasting organization that maintained its parliamentary representation for over three decades and survived its charismatic founder's death in 2022.8 This longevity is an exceptional achievement in a post-communist context usually characterized by instability of parties and fluidity of party systems. In the 1990s, the LDPR advocated hawkish militarism and imperialism as an alternative path to Yeltsin's pro-Western foreign policy. At its conception, the LDPR was both anti-communist and anti-reformist, yet it promised an affluent economic order based on private property, restoration of Russia's military might, and the resurrection of its neo-colonial dominance in Eurasia. The LDPR demonized the ruling “democrats” as the usurpers of power and made ridiculous electoral promises, such as free distribution of vodka. Zhirinovsky famously promised that under his leadership Russian soldiers will “wash their boots in the warm waters of the Indian Ocean” (Specter, 1994). Another characteristic campaign promise was “a man to every woman and vodka to every man.”

The LDPR platform seemed naive and ridiculous in the 1990s, yet many of the party's positions became the mainstream political discourse in the 2010–2020. These include the critique of the dissolution of the Soviet Union as Russia's major fiasco (a thesis that later became the central point of Putin's agenda of “bringing Russia up from its knees”), glorification of totalitarian past and strong statist leaders, calls for the reunification of all land previously controlled by the Russian empire, and its contradictory version of nationalism that is racist and yet ethnically ambiguous (Zhirinovsky was born in Central Asia in a Jewish Ukrainian family). The LDPR pioneered many influential populist appeals and strategies. Its version of populist nationalism spanned the entire post-Soviet period and made a substantial impact on the development of the party system, policy discourse, and political communication in Russia and the Russophone “near abroad.” Many elements of the LDPR message had been copied and re-combined by other parties in Russia, including the Great Fatherland Party (2013–2020) and Russia's Democratic Choice (2010–2016).

While the LDPR stayed true to its populist credo for decades, another post-Soviet right-wing populist party Svoboda (Liberty) Social-National Party of Ukraine went through a considerable transformation. Founded in the 1991 as a neo-Nazi, ultra-nationalist, and anti-communist organization, they underwent a major transformation during the Orange Revolution of 2004 to broaden its popular appeal. Party leader Oleg Tiahnybok purged the organization of extremists and put a considerable effort into distancing the party from the Nazis symbols and rhetoric. Yet, the party retained its ethno-nationalist outlook. In the 2012 parliamentary elections Svoboda received the support of about 10% of voters located predominantly in western, Ukrainian-speaking regions and actively participated in the events of the 2014 Euromaidan revolution (Shekhovtsov and Umland, 2014). In 2014, members of the party served in the first Yatsenyuk cabinet, but withdrew from the governing coalition in anticipation of the 2014 parliamentary elections that did not bring the party enough popular support to clear the 5% electoral threshold. Since then, the party has only been able to win some local elections and remained a marginal political force. Despite a significant moderation of its position and plundering popularity it continues to be a convenient target of much Russian propaganda that claims Ukraine is a neo-Nazi regime.

Another brand of the post-Soviet populist parties dating back to the 1990s is left-wing populism. Unlike right-wing populist parties' appeals for national revival, left-wing populism is more directly associated with the rejection of market economic reforms and the critique of neo-liberal economic policies. Examples of left-wing populist parties include Moldovan? or (Socio-Political movement “Equality,” 1998–2023), Ukraine's Batkivshchyna founded by Yulia Tymoshenko in 1999, Russian party of Pensioners founded in 1997, the Labor Party of Lithuania established in 2003, and Just Russia party established in 2006. All these parties advocate the expansion of the social safety net, government transfers to various groups of population, and removing oligarch's influence from politics. Left-wing populism often combines elements of anti-globalist nationalism, anti-elitism, and statism.

In addition, both reformed and unreformed communist parties had made important strides toward populism. Several major socialist parties broadened their appeals and significantly departed from the working-class-centered ideology to transform themselves into the catch-all parties. Many scholars have identified strong populist elements in their electoral stances. The Communist party of Russia for example, expanded its manifesto to include calls for national unity. The Party of Socialists (PSRM) and Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova (PCRM) appealed to the Soviet nostalgia and opposed liberal economic reforms as elitist and unpatriotic. Similarly, trying to reverse the declining electoral support on the part of pensioners and state employees, in the 2000s the Communist Party of Ukraine assumed the role of systemic opposition and in its 2019 platform went as far as to claim that the Bolsheviks created both the Ukrainian state and Ukrainian nation (Lassila and Nizhnikau, 2022).

As this brief survey reveals, populist ideology has taken on many different forms in the region. Various parties have capitalized on different elements of populist messages, emphasizing either idealized past, pernicious effects of hostile “others,” glorifying power, or crusading against elitist establishment. Depending on the socio-political and international context, populist parties' ideological and cultural references varied, and their targets differed. Manifestations of populist “othering” include anti-Russian (anti-colonial) sentiments of Svoboda and APG; anti-migrant and anti-Western stance of LDPR and Moldovan Socialist, and antisemitism and Muslim migrant targeting rhetoric or Rodina. Post-Soviet populist parties also varied in their attitudes to globalization, a dimension approximated by countries' historic experiences of colonialism. Historic experiences of Russian colonialism, Soviet collectivization, and transitional recession in different ways preconditioned the emergence of ethno-nationalist anti-Russian stances, Soviet nostalgia, revanchist militarism and anti-Western nationalism. Given this variety, it would be hard to find a post-Soviet party not utilizing at least one of the defining elements of populism: idealization of the past, people-centrism, anti-elitism, vilification of the outgroup, or glorification of power. Yet, for many post-Soviet liberal reformists and social-democratic parties (e.g., Yabloko, Our Home—Russia, both Social Democratic parties in Ukraine, and the Social Democratic Party of Moldova) populism never became the defining feature. Some parties experience brief shifts to populist rhetoric, like the Ukraine's Party of Regions which briefly shifted its industrialists-serving agenda to the left to win the 2004 elections only to revert to big business-serving agenda afterwards. Additionally, many regional, ethnic, or issue-specific parties seldom ventured into populist rhetoric (e.g., the Baltic Republican Party in Russia, the Buryat-Mongolian People's Party in Russia, the Party of Hungarians of Ukraine, the Ecologist Green Party in Moldova). The only persistent populist element of the autocrats' “pocket parties” had been the glorification of their leaders (e.g., Nur Otan in Kazakhstan, the New Azerbaijan Party, the People's Democratic Party of Uzbekistan).

Unrestricted access to the electoral arena and legal guarantees for free speech had been important preconditions for the emergence and evolution of populist party organizations in the post-Soviet space. Countries that explicitly banned certain types of political expression (Kazakhstan, for example constitutionally banns ethnic haltered in public speech) had not seen right-wing populist party formation. Constitutional weakness of legislative branches embedded in many post-Soviet constitutions weakened democratic accountability, contributing to the party fragility.

5 Populist leaders

The post-Soviet space had been home to the prominent charismatic leaders who strategically chose their rhetoric, image, and political promises to win popular support. The first generation of post-communist populist leaders came to prominence on the wave of anti-communist mobilization culminating in the dissolution of the USSR and the establishment of the newly independent states. A cohort of charismatic leaders (Boris Yeltsin of Russia, Zviad Gamsakhurdia of Georgia, Abulfaz Elchibey of Azerbaijan, Olzhas Suleymenov of Kazakhstan, Aliaksandr Lukashenka of Belarus) came to the fore tying their political ambitions to various permutations of populist rhetoric, including appeals to people's sovereignty, ethnic nationalism, anti-elitism, anti-corruption, and the historical destiny of their people. As many of these charismatic populists were elected the first post-communist presidents, March (2017) calls them the “mobilization presidents” who “managed to use populism to connect to mass mobilization and bring themselves to power” (p. 222).9

The populism of such mobilization leaders, however, seldom survived the consolidation of their power in the new institutional makeup of the post-Soviet states. The prime example is the transformation of Yeltsin's political agenda and leadership style from the defense of people sovereignty and rebellious defiance of state authority to the institution-builder and defender of the super-presidential regime that soon emerged. In a short time between the collapse of the USSR in 1991 and the 1995 presidential elections Yeltsin transformed from the tank-riding, people-hands-shaking revolutionary to the Kremlin-dwelling, tennis-playing, foreign-leaders-embracing supporter of the oligarchs. Many other populist leaders have followed the same trajectory: rising to prominence on populist rhetoric, securing public office, and successfully assimilating the political establishment's message and style. If initially unsuccessful in their bids for executive offices, some populist leaders became party-builders–a path exemplified by Zhirinovsky and LDPR and Tymoshenko and Batkivshchyna party.

A far greater number of populist politicians have not been party-builders. Yeltsin's presidential challenger General Alexander Lebed, for example, had started his political career in 1995 as a member of the centrist Congress of Russian Communities. His 1996 bid for presidency was cast in a populist law and order rhetoric and a promise to end an unpopular Chechen conflict. Mounting an attack on the state allegedly jointly controlled by the nomenklatura and criminal forces, Lebed claimed a strong military man like him was the only force capable of transforming the state, ending the embezzlement of national resources, and creating the market conditions for economic recovery. After finishing the 1996 presidential race in third place after incumbent president Yeltsin and communist Genadiy Zyuganov, Lebed joined the executive Security Council and abandoned his presidential aspirations. He was later elected governor of the vast and remote Krasnoyarsk Krai region.

Some of the post-Soviet populists were unable to cling to power for long (Gamsakhurdia) and others were assimilated by the political establishment (Lebed, Suleimenov). Yet others were able to maintain their populist style while presiding over the entrenched patrimonial elites and institutionalizing their super-residential rule. Aliaksandr Lukashenka is often seen as the prime example of such an “authoritarian populist” (Matsuzato, 2004). While never departing from his simplistic folk style and supposedly people-centered bashing of internal and external enemies, starting in the early 2000s Lukashenka severely restricted any opportunities for contesting his rule and eliminated legitimate venues for political participation. The true nature of his despotic rule manifested in the 2020–2021 “slipper protest,” when the “people's president” ordered mass arrests, beatings, and torture of thousands of peaceful protesters against electoral fraud he orchestrated to remain in power.

In recent years Lukashenka has been adopting nativist rhetoric to further his “populist” platform, particularly through historical revisionism and manipulation of domestic ethnic tensions. Using the war in Ukraine as a backdrop, Lukashenka has portrayed Belarus as a nation under siege, particularly by NATO, Poland, and ethnic Poles living in Belarus. Ethnic Poles have been delineated as “internal traitors” to the regime; individuals such as Andrezej Poczobut, were sentenced to years in prison for allegedly inciting hatred and promoting Nazism. Lukashenka's government enacted the “Law on Genocide of the Belarusian People,” revising history to paint Poles and the West as Nazi-aligned enemies while promoting a homogenous, Soviet-style Belarusian identity. This historical revisionism reinforces anti-Polish rhetoric, with the state increasingly viewing Poles as a pro-Western fifth column. Lukashenka's leadership style, ethno-nationalism, and demonization of domestic and foreign “enemies” are clear manifestations of populism, yet his appeals to popular sovereignty and anti-elitism had been undercut by the efforts to repress popular mobilization.

The color revolutions of the early 2000s brought about the second generation of populist mobilization leaders, such as Julia Tymoshenko of Ukraine and Mikheil Saakashvili in Georgia.10 While Tymoshenko emerged from the parliamentary opposition, Saakashvili had held a ministerial position under President Shevardnadze only to later fall out and lead anti-government protests in 2003. Both founded oppositional parties–Batkivshchyna and United National Movement–that survived past their founder's hold of government premier and presidential terms. Both leaders professed a nationalist, anti-elitist, and pro-Western style of nationalism, yet Tymoshenko's message was centered on a social justice and anti-oligarchy crusade, while Saakashvili focused on anti-corruption. Both employed populist tactics on the campaign trail: promising easy solutions to social problems, speaking to their supporters in a simple language, surrounding themselves with “common people” and parading ethnic symbolism. While in office, both stuck to their electoral agenda: lavish social spendings in the case of Tymoshenko11 and anti-corruption reforms, including lustration in the security services in the case of Saakashvili. Yet, while holding office, both leaders have moderated their nationalist and anti-elite rhetoric. After suffering electoral losses, both leaders faced legal prosecution for actions committed while in office.

The 2020s have seen the third wave of populist mobilizational leaders who came to prominence in the new tide of anti-government mobilization in Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Ukraine, Armenia, and Georgia. While all have championed anti-corruption appeals, anti-elitism, appeals to traditional values and nationalism, and positioned themselves as outsiders, the political tactics these leaders employed varied as their respective countries enjoyed varying levels of political pluralism and civil liberties. Although the 2018 Velvet revolution in Armenia is usually considered the last of the “color revolutions” of the 2000s, it brought to the prime-minister position a journalist, turned populist, Nikol Pashinyan, who best fits this type of third-generation populist. A true political outsider, Pashinyan capitalizes on the image of “the man of the people.” He combined this image with nationalist rhetoric in what some analysts called war-provoking (Huseynov, 2020) populist foreign policy (Nikoghosyan and Ter-Matevosyan, 2022) that led to the devastating defeat in a war with Azerbaijan and the 2022 loss of Nagorno-Karabakh.

In 2019, Volodymir Zelenskyy became the next populist outsider to rise to the position of head of the state. A famous Ukrainian comedian, in 2015–2019 Zelenskyy starred in a TV political comedy “Servant of the People” as a schoolteacher erroneously elected president (Yanchenko, 2022; Yanchenko and Zulianello, 2024). The TV show's slogan “the story of the next president,” was the headline of Zelenskyy's 2019 electoral platform of a common man destined to shake up corrupt “corridors of power” (Ryabinska, 2024). With a swift emotionally charged electoral campaign against the incumbent millionaire Petro Poroshenko, Zelenskyy was able to win the support of 73% of Ukraine's voters—an unprecedented victory in a country where since 1994 all presidential races have been won by narrow majorities. Unlike many other post-Soviet leaders, Zelenskyy's candidacy consisted of emotional yet substantively vague messages. He didn't take nuanced positions on complex issues. Instead, his electoral message was formulated in simple straightforward language of an average person. His identity of a Jewish Ukrainian from the Russian-speaking eastern region projected a variant of ambiguous nationalism, reminiscent of Zhirinovsky's longing for the restoration of national greatness.

If Zelenskyy represents a true outsider type of mobilizational populist (Aleksei Navalny and Levan Vasadze12 will fall into this category as well), Sadyr Japarov of Kyrgyzstan represents a “recalcitrant member of the political class” type of mobilizational populist leader. Japarov's political career dates to the Tulip Revolution of 2005. After being elected to the national legislature he was picked by President Bakiev to serve as head of the Anti-Corruption Agency. After losing his government post in the 2010 April revolution he became a sharp critic of “anti-patriotic” dealings of the political elites who, according to him sold off the country's natural resources to foreign corporations and pocketed the proceeds without addressing the needs of the common people. In 2013, Japarov emerged as a leader of a popular movement to re-nationalize Kyrgyzstan's most lucrative gold mine and participated in violent opposition protests that escalated to attempts to seize the presidential residence and kidnap local officials. To evade prosecution for his violent acts, Japarov fled the country, but upon his return to Kyrgyzstan in 2017 was arrested and sentenced to 11 years in prison (Pikulicka-Wilczewska, 2021).

The trajectory of Japarov's rise on the wave of mass mobilization against corruption, persecution for participation in street protests, exile, and imprisonment foreshadows that of Alexey Navalny in Russia.13 Unlike Navalny, however, Japarov was successful in mobilizing supporters to free him from prison during the 2020 electoral fraud protests. He was acquitted in his second trial and became the country's acting president. After securing the legitimacy of his presidential office in a staggering 79% electoral victory in 2021, Japarov amended the country's constitution to strengthen the executive central power. Notably, Article 2 of the Constitution replaced the “supremacy of law” with “supremacy of the power of the people, represented by the President.” The amendments not only enshrined the core populist principles in the country's constitutional law but also insulated the president from any institutional checks and balances. According to the proponents of this reform, insulating the president from the influence of other institutional forces ensured that corrupt elites could not “buy him off” so that the president is free to implement the will of the people. The revolutionary mobilization against government corruption culminated in the election of an autocrat because of his supposed responsiveness to ordinary people (Chekirova, 2023).

The contrast between Zelenskyy and Japarov's presidency is staggering, yet both embody the quintessential features of populist leadership: the juxtaposition between virtuous masses and corrupt elites; reliance on the will and power of the people; emotional appeals to social justice; and relatable simple-man language. There are other regional leaders, who used similar strategies. Moldovan President Maia Sandu centered her message on anti-corruption, nationalism, and increasingly on the fear of Russian neo-colonialism. A Harvard graduate, Sandu served as an adviser to the World Bank and a Minister of Education under President Nicolae Timofti (2012–2015). During the 2015–2016 popular protests against the oligarchic state capture, Sandu founded a liberal pro-Western Party of Action and Solidarity, but her 2016 presidential bid failed to overtake the pro-Russian Socialist's candidate Igor Dodon. Under Dodon's presidency Moldova continued the path of oligarchic capture and democratic backsliding while a broad political coalition emerged on the growing public distaste for political corruption (Marandici, 2021a, 2025). In 2019, Sandu's Party of Action and Solidarity secured 15 seats in a 101-strong legislature, split with its electoral coalition partner, the center-right Dignity and Truth Platform, and formed a governing coalition with the pro-Russian socialist PSRM.

Sandu's premiership led to a constitutional crisis and resulted in a vote of no confidence later in 2019. While heading a caretaker government, Sandu run for presidential office in 2020. Her campaign had been a direct extension of the popular mobilization against oligarchic elites who evaded prosecution for their corrupt behavior and peddled their interests at the expense of the Moldovan people (Moisé, 2021). Countering the “populist rhetoric of power” professed by PCRM, Sor, and the Democratic Party, Sandu “employed a populist rhetoric of the anti-oligarchic opposition” (Peru-Balan, 2017). Similarly to Navalny and Zelensky, Sandu exemplifies the democracy-promoting popular-sovereignty push-back against oligarchy, corruption, and crony authoritarianism. Unlike her political opponents' nostalgia- and social justice-based rhetoric (Marandici, 2021a), Sandu's populism targeted younger generations, who no longer could relate to the bygone Soviet era but instead had an optimistic outlook on the European Union. While the electoral failures of the left-wing Moldovan populists may be linked to their inability to build strong party organizations that go beyond charismatic leadership (Gherghina and Soare, 2021), it remains unclear whether PAS will be able to sustain a lasting catch-all electoral appeal and build party organization independent of tits charismatic founder.14

While Sandu's anti-corruption rhetoric had been followed by political actions to undercut the influence of moneyed interests, it would not be correct to take all populist anti-oligarch rhetoric at its face value. The right-wing Order and Justice and the left-wing Labor Party in Lithuania, for example, criticized the high-level corruption and undue oligarchic influence in politics, yet both parties had been implicated in political scandals linked to illegal financing and bug-biasness favoritism. Some populist parties, such as Moldova's PSRM in 2002–2009, comfortably combined anti-oligarchic people-centered rhetoric with business-state collision. The oligarchs' support for the anti-elitist anti-corruption agenda, like in the case of Ukraine's business tycoon Kolomoisky's backing Zelenskiy's presidential campaign, might seem counterintuitive (Williams and Zinets, 2019). Yet, given the ubiquitous influence of money in the post-Soviet politics, oligarchs may find populist parties instrumental in their inter-elite struggles, rent extraction, or political risk hedging. Future exploration of the interplay between populism and business interest would be a welcomed addition to the growing literature on the politics of oligarchic influence (Markus and Charnysh, 2017; Szakonyi, 2020; Marandici, 2021b).

6 Populist mass mobilization

The previous section discussed the post-Soviet populist leaders who rose to prominence either during the early years of transition or during times of regime backdown. Those were the times of political pluralism and popular mobilization that challenged the state. The flip side of populist leadership is populist following, or the reception and support for anti-elitist, nativist, and traditionalist messages on the part of the mass public. Populist syndrome often manifests in electoral mobilization for populist parties and leaders as well as in the mass protests, grassroot organizations, and vigilante groups professing ideas of popular sovereignty. A popular leader who can effectively communicate with the mass public has often been the key in instigating support for populist programs. Yet, the most impactful populist mobilization episodes have been aided by political organizations, such as parties and civic associations. Vladimir Zhirinovsky, Alexander Lebed, Julia Tymoshenko, and Mia Sandu mobilized their supporters with the help of political party organizations.

The “revolutionary populist” leaders of the color revolutions and anti-regime protests of the 2010s galvanized mass electoral and protest mobilization with messages that simultaneously directed social grievances against elite corruption and betrayal of people's interests as well as patriotic nationalist appeals. A vast majority of post-Soviet protest episodes cluster around elections, when mobilization is happening around contested outcomes. The populist message then centers on the critique of corrupt officials who steal the elections, but may also take on more explicit traditionalist, nativist, and nationalist turns depending on the nature of the contested policy alternatives. There were major protest episodes that were instigated by non-electoral developments, such as the 2014 Maidan revolution protesting Ukraine's withdrawal from the EU association agreement or the 2017 Russian protests that followed the release of the investigative documentary “He is Not Dimon” by Aleksey Navalny's Foundation for the Fight of Corruption (FFC). The documentary implicated then Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev in high-profile corruption and resulting in a series of mass protests.

Navalny's rise as the leader of populist mobilization was aided by his investments in building a NGO, the Anti-Corruption Foundation in 2011. Figure 2 illustrates different manifestations or Russia's anticorruption mobilization. Navalny's independent political career started with his expulsion from the liberal Yabloko party for participating in the nationalist Russian March protests in 2007. Following the failed electoral fraud protests of 2011 Navalny and his NGO engaged in investigative reporting of the extensive corruption and embezzlement schemes implicating Russia's top political elite. Focusing on the critiques of elite corruption that resonated with the public, Navalny quickly gained popularity and in the 2013 mayoral elections received 27% of the vote. This threatened the security of the Kremlin-backed establishment and made Navalny the top enemy of Putin's regime.

Figure 2. Populist syndrome domains: illustrating application to Navalny's anticorruption movement. The boundaries between the domains are pervious, yest the diagram allows separating electoral, ideological, strategic, and socio-cultural aspects of Navalny's movement.

Navalny and his foundation were targeted by several court cases, including embezzlement, fraud, and illegal financing. Continuing investigative reporting, questioned the prosperity and social justice-based claims of Putin's regime and culminated in a massive wave of anti-regime protests that swept vast Russian regions in 2017–2018. Like political party organization, FFC with its regional chapters, staff, and collection of donations had been instrumental in successful populist mobilization. The anti-corruption movement and protest activities were further galvanized by the 2017 and 2019 violent attacks on Navalny, who fled the country after being poisoned by a radioactive substance. While in exile Navalny and his team worked on another investigative report exposing the workings of Russia's security agencies against civil activists. Faced with the pending criminal sentence he returned to Russia in 2021 to face another trial, conviction, imprisonment, and death in the Arctic penal colony in 2024. The 2021 protests demanding Navalny's release paled in comparison to the 2017–2018 movement. At the same time the Russian government used increasingly repressive methods to demobilize the movement.

Russia's anti-corruption movement exemplified the non-violent mobilization against the self-enriching political establishment. Yet, the post-Soviet populist mobilization also had a violent side, clearly tapping into the 3rd and 4th defining elements of populist syndrome from p. 4 of this article: reverence for power manifested in militarism, longing for strong leader, juxtaposition of the organic society and the hostile and disruptive “other.” The Georgina March and Kyrk Choro in Kyrgyzstan exemplify populist movements that despite being small in membership and marginal to the political science, have been mobilizing supporters for violent acts in the name of ethnic nationalism and traditional values. Although Georgia is home to a few ultra-nationalist conservative groups (Geo Pepe, Georgian Power, Resistance, Zneoba, and Georgian Idea), Georgian March is by far the most vocal and recognizable populist group. It might be small, but its effect on national politics had been extremely influential. The group was founded during the 2017 anti-immigrant protests (Silagadze, 2020). In 2018, the movement organized counter-protests involving recreational drug liberalization rallies and successfully disrupted the Tbilisi Pride Parade. Members of the movement made rape threats to the liberal Youth representative to the UN and protested a member of the national football team because of his support for the LGBTQ rights. They violently attacked a journalist who expressed ideas the Georgian March found insulting to Christians. Despite attracting a lot of media coverage for their extremist rhetoric and public displays of violence, Georgian March gained a negligible electoral support, winning only 0.3% of the national vote in the 2020 elections and quickly faded from the political scene after that. The 2020 report concluded that Georgian March and similar groups “remain on the margins and do not have a decisive influence over Georgian public discourse at this point” (Tugushi et al., 2019)

Another example of an extremist populist movement is Kyrgyz Kyrk Choro. The group has advocated for the revival of Kyrgyz traditional culture and social values since 2011. It made international headlines in 2014 when it raided a foreign-owned karaoke bar, harassed its mixed-gender audience, detained several Chinese migrants and turned them over to the police. The movement's activists are self-professed Kyrgyz patriots who claim to guard the purity of the ancient ways of life and reject liberal Western values as alien to the Kyrgyz society. They have successfully politicized the historic memory of Chinese conquest and enslavement of the seventeenth century to target Chinese-owned business, bazaar traders, and other migrants as the national enemy. The movement recruits it following among young provincial men who engage in vigilante-style police raids against illegal immigrants, prostitution rings, and LGBTQ organizations and other supposedly “immoral” groups (Aitkulova, 2021). In 2016, masked members of the movement violently attacked the Feminist March in Bishkek for promulgating liberal values alien to the Kyrgyz society. Notably, the police, predominantly composed of traditionalist men, failed to stop the attacks, arresting the members of the Feminist March instead. Kyrk Choro took an active part in the 2020 riots that were sparked by allegations of electoral fraud (BBC, 2020). Movement sympathizers backed the anti-establishment nationalist Sadyr Japarov as their presidential nominee and refused to back any of the opposition parties, whom they deemed corrupted by Western liberalism.

Close ties between Kyryk Choro and law-enforcement agencies raises a question of whether the movement had been a disguised top-down attempt by the state to mobilize and channel social grievances in a way that lends political benefits to the political elites. Similar suspicions had been raised about Russia's government tolerance of so-called systemic opposition, such as Our Home Russia (OHR), LDPR, and the Union of Rightist Forces.15 An important enabling factor in populist mobilization had been the lack of violent repression on the part of the government and respect for the rights of speech and assembly. When the state had employed repressive force to target civil organizations and violently suppressed protests, populist movements had been quickly crushed.

7 The demise of pluralism and autocratic pseudo-populism

As the previous sections demonstrated, the revolutionary upheavals which led to the leadership turnovers and prevented autocratic consolidation were accompanied by a surge in populist manifestations. Populist parties and leaders used inflammatory rhetoric that channeled popular grievances toward specific targets: corrupt elites and variously defined “others.” Yet, as early as the late 1990s, some the post-communist regimes entered the consolidation stage. Illiberal electoral autocracies, characterized by limited political competition, consolidated first in Central Asia, Belarus, Azerbaijan, and later in Russia.16 These countries went through constitutional changes that effectively insulated incumbent leaders from political contestation and popular pressures. They tightened restrictions on civil society making it difficult for the people to organize in pursuit of their interests. Oppositional parties faced high hurdles in financing their operations, putting their candidates on the ballots, and getting access to the media. The latter, through different economic and regulatory mechanisms came under a tight state control. When parties were able to put their candidates on the ballot and mobilize electoral support, they often lost elections because of ballot stuffing and other types of electoral fraud. Street protests got suppressed with increasing brutality. How did such conditions affect populist syndrome?

When the opposition is excluded from politics, media is tightly controlled, and civil society curtailed, the only political force that can resort to populist rhetoric, policy, and leadership style is the autocratic leader. In fact, the post-Soviet space is filled with charismatic autocrats who effectively employ populist rhetoric and pursue nationalist (protectionist) economic policies (Lukashenka and Putin), social and emigration policies that target minorities or the “others” (Japarov, and Islam Karimov, whose anti-Islamism policy targeted rural areas and regional clans), embed traditionalist values in the country's legislation (Russia's anti-gay laws or laws banning child adoption by foreigners), and define their foreign policy objectives in terms of revisionist notions of national greatness.17

From the early years of independence Central Asia regime legitimation had rested on nativism, ethno-nationalist ideology, traditionalism, and, in some instances anti-elitism, by trying to cast elites in the liberal, colonial, or Western terms. The nationalist and patriotic rhetoric often serves as the symbol of a leader's commitment to native people. Traditionalism, anti-liberalism, and anti-colonialism justified authorities' attacks of liberal opposition that usually demanded upholding human rights, protecting minorities, and guaranteeing free elections (Karlekar and Tripathi, 2024). At the same time, the Central Asian leaders mostly refrained from mobilizing various types of political participation. While holding elections, they maintained a tight control on the ballot composition, electoral campaign messaging, and often manipulated the published election results. They preemptively disrupted organizational venues of popular mobilization and relied on violence and intimidation, rather than trying to win the hearts and minds of their people.

The political style of Saparmurat Niyazov is the prime example of such a quasi-populist legitimation strategy. A Communist Party leader of Soviet Turkmenistan, Niyazov learned the rhetorical power of appeals to the “the will of the people” in the Communist party school. After the dissolution of the USSR in 1991 he quickly consolidated his rule over an independent Turkmenistan and resorted to traditionalism and messianic nationalism as the legitimizing principles of his regime. He authored a two-volume epic “Ruhnama,” or the Book of the Soul, which, according to Niyazov, was inspired by his prophetic vision of his destiny to lead the nation to the “golden age.” Like Mao's Little Red Book, traditionalism and ethno-nationalism had been the central elements of his ideology, yet through his rule he only paid lip service to popular sovereignty, distancing himself from the people and demobilizing political participation.

Kassym-Jomart Tokayev of Kazakhstan is largely seen as a pragmatic technocrat, yet he made an overture to a populist stance following a failed coup attempt by the members of Nazarbayev clan. In 2019, Nursultan Nazarbayev, who ruled Kazakhstan since 1989, transferred the residency to Tokayev. Nazarbayev's family members continued to occupy the leading positions. And intra-elite conflict brewed. In January 2022, elite-instigated anti-government riots occurred. Tokayev's rule was maintained with the help of the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) troops. Emerging victorious from the confrontation with the intra-elite challengers, on Jan 11, Tokayev delivered a televised speech against destructive activities of powerful economic elites: “A group of very profitable companies emerged in the country as well as a group of wealthy individuals… I think it is time they pay their dues to the people of Kazakhstan…” Tokayev's acknowledgment of the divide between national elites and the masses, his siding with the people, and the calls for redistributive justice fit squarely with the populist project (Tokayev, 2022). Yet no populist moves have followed this people-centric stance. In 3 years following his “populist pivot” Tokayev has not engaged in any redistributive reforms and has not purged the elites.18

Some observers see President Putin as a populist leader following the 2008 financial crisis and the country's turn to nationalism and traditionalism in the aftermath of the 2014 annexation of Crimea (Busygina, 2019; Hoppe, 2022). Yet others debate this label. March even calls Putin an “anti-populist” (2017). Putin's prioritization of institution-building, technocratic governance, reliance on the clientelism of loyal corrupt elites, and his arms-length relations with the masses make his leadership style, policies, and ideology antithetical to populism. According to Morini “…in the Russian case, populism may be seen as a façade mechanism of recruitment and legitimation for authoritarian regimes” (p. 358). Busygina (2019) describes it as “situational populism” the other autocratic leaders also resort to when their regime stability is threatened.

The issue of Putin's (pseudo?) populism is closely connected to the question of Putin's personal popularity. Studies of public opinion, voting, and protest behavior generally conclude that Russian autocracy depends on and is sustained by a widespread popular support for Putin's regime.19 The genuine popularity of Putin and support for the government had been recognized as the central features of regime stability. An agreement emerged around the notion that the negative experiences of the 1990s recession undermined public support for democracy and aided the rise of Russian authoritarianism. Putin's ascension to power has not been a result of popular mobilization. He was an unknown bureaucrat with a security services background who was hand-picked by outgoing president Yeltsin to ensure no members of Yeltsin's family were prosecuted for their corrupt dealings. High energy prices and conservative macroeconomic policy during the first two terms of Putin's presidency produced impressive economic improvements. Although much of the economic prosperity was due to the surge in global oil prices, this did not prevent the people from attributing good lives to autocratic rule. Public opinion research and electoral studies agreed that support for the government in the early 2000s was largely due to the good performance of the Russian economy (Treisman, 2011).

During this period Putin's central message was the supremacy of law and legality, strengthening of central government institutions, and curbing the pernicious influence of the oligarchic elites who “stole” the state (peoples') resources during the Yeltsin-era privatization.20 Putin's leadership style was that of a detail-oriented, hard-working administrator. His regular public appearances mostly featured routine government meetings where he questions ministers and heads of the agencies regarding their specific assignments. Unlike his predecessor, who enthusiastically embraced the rediscovered Christianity, Putin initially maintained very formal relations with the Russian Orthodox Church. The first two terms in office Putin also preferred to keep his hobbies and leisure travel private and kept his shirt (and tie!) on the publicly released photographs. The only aspect of Putin's first two terms that falls under the umbrella of populist performances was his attack on the oligarchs and campaigns to redistribute their property. Yet that redistribution entailed nationalization or acquisition by other elites more loyal to Putin.

The 2008 financial crisis and declining oil prices had a cooling effect. Putin's popularity declined slightly (Treisman, 2014). But such an effect was short-lived. To explain continuing support for the incumbent government in times of slower economic growth, economic setbacks, and international sanctions against the Russian annexation of Crimea the literature focused on the rise of nationalist rhetoric, propaganda, and rallying around the flag effect (Hale, 2018; Frye, 2019; Greene and Robertson, 2017). As the autocratic state was losing its ability to buy off popular approval with generous federal spending, it seemed to shift to the new legitimation strategy that more heavily relied upon nationalist and traditionalism. By fostering a sense of nationalism, and vilifying internal (liberals, the LGBTQ community, foreign-funded NGOs) and external (the West, NATO, the EU, the American propaganda) critics, autocracy justified its rollback on political rights and civil liberties. The pro-regime propaganda had proven effective in maintaining high approval. Even after the start of the war in Ukraine that resulted in sanction-induced currency devaluation, declining incomes, and restrictions of international travel, Putin's approval remains strong (Frye et al., 2023). The 2023 coup attempt did not affect the standard indicators of regime support either (Zakharov et al., 2024). Does it mean that Putin's nationalist, traditionalist, and anti-liberal appeals are successful in channeling peoples' grievances away from the government and toward the “enemies” of Russia? The best answer is that I don't know. One must heavily discount survey research methods in an autocracy that jails critics and labels those who disagree as “foreign agents.” Buckley et al. (2024) suggest that the very notion of Putin's popularity might be deliberately orchestrated by the state-controlled media to suppress anti-regime protests and boost regime stability.

The flip side of government approval—protest behavior—presents a different vantage point to examine populist syndrome in Putin's Russia. In the post-Soviet period, Russian citizens often protested to express their economic and political grievances and to place demands on the authorities (Robertson, 2010; Lankina and Skovoroda, 2016). Researchers explored the connection between protest behavior, elite strategies, and electoral politics and suggested that protests may have enhanced the legitimacy of Russia's autocratic government (Robertson, 2010; Smyth et al., 2013; Frye and Borisova, 2019). By allowing protests to proceed, authorities maintain the semblance of participatory politics and constitutional order. It is true that Putin had never been a mobilizational populist, yet in the first decade of his rule the regime generally tolerated protests and even turned the anti-government mobilization into a tool for maintaining regime stability.

With the nationalist and traditionalist turn in Russian politics, the regimes' tolerance of protests progressively diminished. Authorities' response to the anti-regime Bolotnaya Square protests in 2011 and 2021 used a mixture of police brutality, intimidation of protest leadership, and attacks on civil society organizations. The research found that preemptive repression in Russia effectively undermined protest mobilization (Tertytchnaya, 2023). The latest wave of antiwar protests and their suppression have shown that the Russian state had amassed sufficient repressive power to maintain Putin's regime in the face of declining economic performance and a disillusioned populace. After the start of the 2022 war, a wave of antiwar protests has swept across the country. Observers saw this as an indication of Putin's weakness and imminent decline (Laruelle, 2022). Even before the war Frye saw the increasing use of repression as evidence that “other tools for keeping Putin in power are failing” (Frye, 2021). The regime's appeals to patriotism and its revisionists aspirations to restore Russia's strength and power did not prevent anti-war mass mobilization.

Facing growing opposition to the war, the government criminalized anti-war speech and detained 18910 activists in 2022 (OVD-Info, 2025). As a result of increasing repression, protest activity nearly disappeared in 2023. When in February 2024 the authorities announced Aleksey Navalny had died in an arctic penal colony, Russian authorities arrested 387 people who attempted to publicly mourn the opposition leader's death (Amnesty International, 2024).21 While historically protests in Russia spiked during electoral periods, the 2024 presidential election saw no uptake in the protest activity. Despite the strong belief that Putin's regime depends on the success of his nationalist, anti-liberal rhetoric and vilification of the West strongly supported by the Russian people, repression has been the key to its survival in 2022–2024. Putin's alleged populism had been more of the legitimation strategy, not a political strategy to win and retain power or an ideology for mobilizing mass support.22

8 Concluding remarks

Writing in 1992 about the future of newly liberalized post-communist countries, Ken Jowitt gloomily predicted that “…demagogues, priests, and colonels more than democrats and capitalist” would shape the politics of post-communist Eastern Europe (Jowitt, 1992). At first it seemed that Jowitt got it wrong and Western liberalism triumphed as implied in Francis Fukuyama's “End of History and the Last Man.”23 At the end of the 1990s, Jowett's skepticism seemed more relevant for the aborted democratic transitions of post-Soviet states. Populism of both the left and the right-wing varieties had been the defining feature of post-Soviet politics. The populist syndrome was in full swing in the 1990s during the times of democratic transition. These were characterized by the weak states, fledgling party systems, nascent civil society, and pluralistic (by default) press. This period represented an ideal window of opportunity for populist leaders to build party organizations and mobilize mass electoral support for their candidacies.

Yet, Jowitt's prediction was proven wrong by the consolidation of some post-Soviet states into electoral autocracies and then into traditional, personalistic, and bureaucratic non-participatory regimes with purely symbolic electoral rituals, repressive controls of public activism and silencing of political expression have severely curtailed the populist syndrome in the region. At first, electoral autocratic consolidation meant the development of a stronger state apparatus, consolidation of media space into fewer outlets, and growing importance of institutionalized politics. These conditions still provided opportunities for both incumbents and challengers to engage the public in a populist discourse in support (or to challenge) power contestation. During the times of regime breakdowns that weakened the state, polarized the elites, and agitated civil society, populism grew into a larger force. It provided a powerful tool to mobilize the masses for overthrowing the government and brought to power true and false political outsiders.

The evolution of electoral autocracies into repressive non-participatory regimes put major limitations on some forms of populist manifestations. Strong state institutions, consolidation of elites, suppressed civil society, state monopoly on media, and gradual elimination of political pluralism have closed off populist channels to all but the government actors. Further autocratic consolidation strengthened the regime's resilience to internal challenges and diminished the importance of electoral mechanisms for legitimizing the autocratic rule. The establishment of strict state control over the media and development of comprehensive propaganda eliminated the necessity of including mass political behavior into the calculus of autocratic survival.

The repressive autocracies' populism is a dubious category because outside of the pluralist political space, appeals to popular sovereignty, nativism, and quest for popular support have no real political significance. For that reason, many seemingly populist moves on the part of the autocrats, such as Putin and Tokayev, should not be taken at their face value. We might be witnessing ideological mimicry that with the decline of participatory institutions and the rise of repression becomes an outdated instrument in the toolkit of autocratic rule. “Without a minimal level of pluralism… it is extremely difficult to develop a genuine and stable populist force” (March, 2017, p. 214). In 2025, the state of political repression and mass demobilization in Central Asia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, and Russia are such that no populist party or leader can challenge the political elites with the people-centered political message. As the self-organizing capacity of civil society erodes, even the populist leadership style of autocrats becomes obsolete. This begs a question why do autocrats use populist rhetoric?

One popular argument centered on the cost of repression may help. Because repression is costly, autocrats often employ other less costly measures to entice popular compliance with their rule. The populist ideology may serve as a convenient strategy of regime survival in the face of political contestation by elites and potential mass mobilization. Principles of popular sovereignty, if proclaimed by the leaders and their media propaganda machines may help convince the people that their voice matter, even if their ballots are not counted. Conflict over traditional values and targeting minorities may help divert public's attention from economic issues. It may even be possible to shift the blame for unpopular policies to the foreign enemies plotting against the nation's interests. Yet, as I discussed earlier, Putin's regime's use of populist propaganda did not prevent anti-corruption and anti-war protests that challenged the stability of Putin's regime. At this point, with the Russian government's survival in office resting upon electoral fraud, assault on civil society organizations, and imprisonment of political activists, populist appeals remain a mere window dressing.

I generally worry about populism because of the threat it poses to liberal democracy: populism attacks the institutional foundations of democratic politics, such as independent courts, constitutional checks on the executive, guaranteed protections of minorities, the rule of law, and free media (Madlovics and Magyar, 2021). The post-Soviet populist experience gives a sobering perspective on the global resurgence of populism and its implications for the future of democracy.

It shows that without participatory democratic contestation populism loses its mobilizational function. Because populism is a form of liberal democratic failure, in order for populism to emerge democracy must be present.24 The experience of post-Soviet autocracies show that the destruction of civil liberties and elimination of political pluralism renders all appeals to popular sovereignty and political strategy to mobilize mass support completely irrelevant. With the rise of repressive autocracy, the future of post-Soviet populism is bleak. There is little comfort thought in the notion that if successful in bringing down democratic institutions, populist politics will find its eventual demise in autocratic government.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DD: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to credit my research assistant Celia Frahn, Department of International Relations, Lehigh University for her research support of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^There is a growing objection to the use of “post-Soviet” label because it may intentionally or unintentionally reinforce the (neo-)colonial mindset (Sagatiene, 2023). My focus on countries sharing the legacy of the Soviet rule does not imply any judgment on the cultural belonging of any former Soviet countries to the European civilization, neither does it endorse any political agenda for regional integration or territorial expansion.

2. ^The scholarly interest in post-Soviet populism appears to be on the rise. I analyzed articles published in five leading journals on regional politics (Europe-Asia Studies, Problems of Post-Communism, East European Politics and Societies, Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization, and Post-Soviet Affairs). In the period between 1997 and 2013 I found the term populism appeared in the titles, keywords, or abstracts of the articles addressing post-Soviet states 23.3 times per year on average. That number increased to 35.7 times per year on average in 2014–2024.

3. ^Despite their good democratic records, the Baltic countries had not been immune to the resurgence of populism (Pettai, 2019). On the contrary, populism had been a prominent and consistent feature of Baltic politics since democratic transition. Ulinskaite and Pukelis (2024), for example, find that Lithuanian country-wide “populist discourse has remained fairly stable over the period” of 1990–2020, noting a short-lived increase in populist rhetoric in 2008–2009. The Baltic states provide ample examples of populist parties on the left (e.g., the Lithuanian People's Party and the Labor Party) and the right (e.g., the Conservative People's Party of Estonia (EKRE), Latvia First party, Latvian National Alliance) and have shared with other post-Soviet countries many aspects of populist rhetoric and electoral mobilization strategies.

4. ^Many proper names referenced in this paper are known to academic audiences in the Russified or Westernized forms. I will spell them according to the corresponding national languages.

5. ^Based on the expert survey defying populism as a confluence of juxtaposition between elites and masses and belief in the supremacy of the will of the people, Silagadze concludes that ethnonational and religious Alliance of Patriots of Georgia (APG) and leftist Labor Party (LP) are the only populist parties in contemporary Georgia.

6. ^See Hoppe (2022) for an inciteful analysis of that he calls sovereigntism and anti-corruption messianism as two characteristics modes of post-Soviet populist mobilization.

7. ^Even as the government of Russia made a traditionalist turn in the 2010s with the adoption of a series of laws promulgating traditional values and banning “LGBT propaganda,” a regional court banned the party in 2011 as an extremist organization.

8. ^After receiving an impressive 22.8% of the national vote in the 1991 presidential elections, Zhirinovsky's personal electoral success declined to single-digits since the 1996 presidential elections, while LDPR's performance stabilized at about 11% of the national vote, dropping to 8% and 7.5% of the national vote in 2007 and 2021.

9. ^The adoption of populist stances by post-Soviet autocrats during the episode of popular mobilization or the elite threats had been yet another manifestation of post-Soviet populist syndrome (Busygina, 2019). I discuss such cases in Section 7.

10. ^Kurmanbek Bakiev in Kyrgyz Republic is a good candidate for inclusion in this cohort of populist leaders: a regime insider capitalizing on the 2005 popular mobilization against his predecessor, Askar Akaev, in 2005. After assuming power, however, he embarked on solidifying a repressive clan-based regime, profiteering from corruption and selling off national resources and after being ousted by the 2010 protests faced criminal charges for the actions committed in office.

11. ^High levels of social spending had been the central reason Timochenko is considered populist (Kuzio, 2010).

12. ^A conservative pro-Kremlin Georgian businessman, Levan Vasadze, founded the Eri political party to contest the 2021 municipal elections in Georgia with attacks against the LGBTQ community, liberal NGOs, and paradoxically, given his business background, economic liberalism. Vasadze's populist strategy heavily rests on his outsider credentials, and he is widely believed to be supported by Russian authorities as an instrument of extending Russian influence in Georgia.

13. ^The next section of the paper discusses Navalny's role in organizing Russia's anti-corruption political movement.

14. ^For a Humane Latvia party (former Who Ones the State?) presents a cautionary tale of the importance of charismatic leadership in anti-corruption populist mobilization. After receiving the second-largest vote for its anti-corruption agenda in 2018, the party ousted two of its populist leaders Aldis Gobzems and Artuss Kaimins. Subsequently, the party struggled to position itself vis-à-vis other political forces and saw a precipitous decline in its popular support.