- 1Department of Historical and Classical Studies, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

- 2Department of Political Science, MacEwan University, Edmonton, AB, Canada

This paper contributes to the growing demand-side literature on populism by investigating how different types of populist attitudes shape support for strongman leaders. By capitalizing on popular discontent with the political establishment, populist leaders often ascend to power through democratic means, only to consolidate authority and weaken the very institutions that facilitated their rise. We argue that a major obstacle to understanding populist support lies in the tendency to treat populist attitudes as a single, monolithic construct. Dominated by the ideational approach, much of the existing literature neglects the role of the populist strongman and offers only limited conceptual clarity on authoritarian populism—particularly at the attitudinal level. To address this gap, we develop a more refined framework that moves beyond the standard definitional elements of the ideational model, demonstrating that populist attitudes consist of two distinct varieties. Using novel survey data from nine countries, we conduct a factor analysis that consistently reveals two components: one capturing anti-elitism and people-centrism (anti-establishment populism), and another reflecting majoritarianism, support for strongman rule, elitism, and exclusive nationalism (authoritarian populism). This underscores that the appeal of populist strongmen is rooted not in democratic ideals, but rather in the allure of authoritarian governance. Our findings show that in six countries—Italy, Hungary, Poland, Spain, Brazil, and Argentina—support for populist leaders is primarily driven by authoritarian populist attitudes. In contrast, anti-establishment populism emerges as the dominant factor only in France and Canada, while neither dimension has a significant effect in the United States.

1 Introduction

The rise of populist leaders, often labeled as strongmen, has drawn significant scholarly and media attention over the past two decades (Ben-Ghiat, 2020; Rachman, 2022). Studies emphasize their charisma (Pappas, 2016; McDonnell, 2016) and rhetorical style (Ostiguy, 2009), which foster a direct bond with the masses (Germani, 1978; Mény and Surel, 2002), often through “low,” coarse, and folksy language to project authenticity (Ostiguy and Roberts, 2016). Research on the economic and political consequences of populist governance has predominantly produced negative findings. Funke et al. (2023) show that prolonged populism results in economic decline, lower GDP, and diminished macroeconomic stability. Ruth-Lovell and Grahn (2023) argue that populist governance erodes electoral, liberal, and deliberative dimensions of democracy, while Erhardt and Filsinger (2024) contend that the primary danger to contemporary democratic survival stems from executive aggrandizement carried out by elected populist leaders. Despite these harmful consequences, populist leaders continue to enjoy substantial public backing, raising a crucial question: why do citizens back populist strongmen, even when such support threatens democratic institutions and economic stability?

The literature presents an ambivalent relationship between populism and democracy. On one hand, some scholars argue that populism is inherently illiberal, as it rejects electoral competition and institutional checks and balances—core tenets of representative democracy (Müller, 2014; Urbinati, 2019; Pappas and Kriesi, 2015). Populist movements embrace majoritarian politics and seek to suppress opposition, often through a charismatic strongman who pledges to dismantle institutional constraints in the name of executing the people’s will. Under this interpretation, populism becomes synonymous with authoritarianism (Bugaric, 2019). On the other hand, an alternative perspective suggests that populism can serve as a corrective to democratic deficiencies (Canovan, 1999; Laclau, 2005). Populists claim to represent the true will of the people and argue that existing institutions are insufficiently democratic (Ivaldi et al., 2017; Jacobs et al., 2018). From this perspective, some scholars see populism as a “politics of hope” (Spruyt et al., 2016) that reinvigorates democracy (Stavrakakis and Katsambekis, 2014). According to this view, populist leaders are essential for uniting diverse groups in opposition to entrenched elites and driving political change (Laclau, 2005). These competing interpretations highlight the complexity of populist politics and the need for a more nuanced understanding of what drives its appeal among supporters.

Although both scenarios are plausible, our understanding of the underlying motivations driving individual-level support for populist leaders remains limited. Drawing on the growing body of demand-side literature on populism, this paper explores the extent to which populist attitudes influence support for strongman leaders. Empirical research on populist attitudes has produced mixed and occasionally contradictory results. While some studies suggest that populist attitudes increase the likelihood of voting for a populist party (Akkerman et al., 2014; Van Hauwaert and Kessel, 2018), others argue that ideological alignment plays a more decisive role (Kittel, 2024; Dai and Kustov, 2024; Castanho Silva et al., 2022). More surprisingly, some studies find that populist citizens simultaneously favor direct democracy while also supporting authoritarian decision-making (Wegscheider et al., 2023) or rule by a small group of elites (Spruyt et al., 2023).

These inconsistencies indicate that populism, along with populist attitudes, is not a monolithic phenomenon but instead comprises distinct strands, each with varying implications for support for democratic institutions and democracy more broadly.

We argue that a significant challenge in understanding populist support stems from the overlooked variety of populist attitudes. Thus far, the conceptualization of populist attitudes has largely been shaped by the ideational approach, focusing primarily on anti-elitism and people-centrism (Mudde, 2004; Akkerman et al., 2014; Castanho Silva et al., 2020). While this approach has significantly advanced our understanding of populism, it neglects a crucial dimension: the appeal of strongman leadership to a specific subset of populist supporters. For these individuals, a strong leader embodies security and prosperity for the dominant majority, motivating their support through the belief that such leadership can safeguard traditional values and protect their perceived interests. Building upon this argument, we propose that distinguishing between distinct types of populist supporters—those endorsing a democratic, people-centered variant and those inclined toward authoritarian forms of leadership—is not only analytically feasible but also theoretically imperative. Our key assertion is that populist attitudes manifest in two distinct forms. The first, anti-establishment populism, repudiates the ruling elites, champions the will of the people, and supports more direct democratic representation—an approach well captured by the ideational framework. The second, authoritarian populism, rejects liberal democratic norms in favor of strongman leadership. This populist variant privileges leaders willing to subvert democratic institutions to safeguard the interest of the dominant majority responsible for their rise in power.

To test our theory, we analyze original survey data from nine countries across four regions: Western Europe (France, Italy, Spain), Central Europe (Hungary, Poland), North America (Canada, U. S.), and South America (Brazil, Argentina). The supply-side literature on populism often emphasizes that populist movements can be categorized along an inclusionary-exclusionary dimension, itself shaped by an underlying left–right ideology (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2013). Left-wing populism, which centers on economic grievances related to inequality, is generally understood as inclusionary. As Vasilopoulos and Jost (2020) note, it embodies a pluralistic conception of society in which ethnic, religious, and sexual minorities are viewed as part of “the people” whose interests deserve protection, particularly against those of the upper class. Accordingly, left-wing populism seeks to extend rights and resources to minority groups (Golder, 2016). By contrast, right-wing populism advances a monolithic notion of “the people” that aligns with the ethnic majority (Vasilopoulos and Jost, 2020). It is, therefore, an exclusionary form of populism that portrays ethnic, religious, and sexual minorities as threats to the perceived homogeneity of the “native” population (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2013). Despite the prominence of several left-wing populist leaders in recent years, this article focuses on right-wing populism. This is because right-wing populist movements have seen a broader and more sustained rise in the past decade and have been more directly associated with challenges to liberal democratic norms, the rule of law, and minority rights. Their exclusionary appeals and framing of “the people” as ethnically or culturally homogenous have made them especially consequential for debates around democratic backsliding and social cohesion. Although each of the leaders examined can be characterized as a right-wing populist strongman or strongwoman, they display notable variation in whether they currently hold office, how extreme or provocative their discourse is, and how much institutional oversight limits their ability to exercise authority without constraint. This enables us to uncover important variation within the broader landscape of right-wing populist leadership, particularly in relation to whether their appeals are rooted more in authoritarian or anti-establishment populist attitudes.

We first employ factor analysis to identify the presence of both anti-establishment and authoritarian populist attitudes in each country. We then run Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regressions to evaluate the impact of these attitudes on electoral support for populist strong(wo)men. Our findings reveal that in six of the nine cases (Italy, Spain, Brazil, Argentina, Hungary, and Poland), electoral support for populist leaders is primarily driven by authoritarian populist attitudes. In only two cases (France and Canada) does anti-establishment populism serve as the main driver, while neither variant significantly influences populist support in the U.S. Overall, our findings point to a troubling trend for democratic stability. Populist voters appear to support right-wing populist leaders not because they view them as champions of democracy, but because they appreciate their willingness to bypass institutional constraints and suppress democratic discourse. This underscores that the appeal of populist strongmen is rooted not in democratic ideals, but rather in the allure of authoritarian governance.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 The populist paradox and the role of the strongman

The tension between the populist strongman’s initial appeal as a champion of the people and the subsequent erosion of democratic norms once that strongman secures power constitutes one of the central paradoxes of populism. Time and again, participants in populist movements lend their support to leaders and parties that profess a commitment to enhancing democratic representation while simultaneously undermining democratic norms and curtailing individual rights and freedoms. Urbinati (2019) aptly characterizes this phenomenon as the “disfigurement of representative democracy.” By capitalizing on popular discontent with the political establishment, populist leaders often ascend to power through democratic means, only to consolidate authority and weaken the very institutions that facilitated their rise.

Nevertheless, considerable debate persists regarding the centrality of the populist leader—or strongman—in defining populism. Weyland (2001, p. 14), a pioneer of the political-strategic approach, conceptualizes populism as a “political strategy through which a personalistic leader seeks or exercises government power based on direct, unmediated, uninstitutionalized support from large numbers of mostly unorganized followers.” Albertazzi and McDonnell (2008, p. 7) similarly contend that “the charismatic bond between leader and follower is absolutely central to populist parties.” This perspective is echoed in Urbinati’s (2019, p. 9) work, where she asserts that populism eschews traditional party structures and deliberative democracy. Instead, populism operates by severing the link between traditional party elites and the electorate, advancing the claim that, because the people and the leader have effectively merged, intermediary elites (i.e., parties) become redundant, as does the process of deliberation. This direct, unmediated relationship between the populist leader and the people fosters a form of plebiscitary democracy in which the leader’s authority is rooted in a perceived mandate from the “authentic” majority, thereby circumventing the checks and balances inherent in liberal democratic regimes.

The political-strategic approach is not without its detractors, who contend that it overemphasizes the centrality of the populist leader in defining populism. Skeptics argue that this framework imputes to the populist strongman a utility-maximizing rationality and power-seeking intent that is not empirically distinguishable from the behavior of other political leaders (Rueda, 2021). Pappas (2016) likewise challenges the presumed link between populism and charismatic leadership, asserting that the presence of charisma should no longer be considered a defining characteristic of populism. Similarly, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (2014, p. 382), key proponents of the ideational approach, argue that populism is not solely confined to the agency of personalistic leaders, noting that “an elective affinity between populism and a strong leader seems to exist. However, the former can exist without the latter.”

Our objective is not to engage in a semantic debate over the proper definition of populism. Instead, we seek to underscore that the chosen definition of populism has direct and consequential implications for how populist attitudes are conceptualized and operationalized at the individual level. To date, the ideational approach—which downplays the centrality of the populist leader—has become the dominant framework in the study of populist attitudes (Castanho Silva et al., 2020). While we acknowledge the significant insights this approach has provided, we contend that it fails to capture the full complexity of populist attitudes and their effects on support for populist strongmen. By focusing predominantly on anti-elitism and people-centeredness, the ideational approach overlooks the authoritarian dimension of populist attitudes—a critical factor in understanding the appeal of strongman figures. Addressing these gaps allows for a more comprehensive analysis of how varieties of populist attitudes interact and influence voter behavior.

The ideational approach, which has largely shaped the conceptualization of populist attitudes at the individual level, defines populism as a thin-centered ideology that constructs society as a dichotomy between two homogeneous and antagonistic groups: the “pure people” and the “corrupt elites” (Mudde, 2004, 2007). Building on this definition, populist attitudes are typically conceptualized as comprising three distinct dimensions: anti-elitism, people-centrism, and a Manichaean worldview that frames society as a struggle between good and evil (Akkerman et al., 2014; Erhardt and Filsinger, 2024). However, this conceptualization overlooks a crucial dimension—the allure of the populist strongman. While the ideational approach emphasizes the moral dichotomy between the “pure people” and the “corrupt elites,” it fails to account for the psychological and emotional appeal of a strong, decisive leader who promises to restore order, defend traditional values, and embody the will of the people. This omission is crucial for accurately capturing populist attitudes, as support for populist strongmen often arises not solely from ideological alignment but also from the belief that these leaders possess the strength and determination required to confront entrenched elites and bring about meaningful change.

Wegscheider et al. (2023) reveal that populist citizens simultaneously exhibit stronger support for direct democratic mechanisms and a greater preference for authoritarian procedures compared to their non-populist counterparts. Donovan (2021) shows that supporters of radical right populist (RRP) parties disproportionately endorse strong, unchecked leaders and express openness to military rule. Moreover, these illiberal attitudes did not predict support for mainstream center-right parties, suggesting that authoritarian attitudes is specific to the RRP base, not just the broader right. Similarly, in their examination of the relationship between populism, elitism, and pluralism, Spruyt et al. (2023) find that a notable segment of populists—particularly those with lower levels of political sophistication—endorse a form of elitism that paradoxically undermines the centrality of “the people” in democratic governance. The propensity for citizens to hold a contradictory and ideologically incoherent set of political beliefs is hardly a novel phenomenon (Converse, 1964). However, we argue that the contradictions inherent in populist attitudes, as outlined above, may be partially attributable to the limitations of the prevailing approach to conceptualizing and measuring these attitudes. Specifically, we argue that populist attitudes manifest in two distinct forms: anti-establishment and authoritarian populism. The ideational approach, with its emphasis on anti-elitism and people-centrism, captures anti-establishment populism but fails to distinguish authoritarian populist attitudes. This oversight is particularly important given that, while Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert (2020) find that populist citizens tend to express stronger support for democracy, they caution that this support may be rooted in a conception of democracy that is at odds with liberal democratic principles, potentially favoring the emergence of illiberal democratic regimes. We concur with their assessment but extend their argument by suggesting that the populist citizenry is not monolithic—some gravitate toward an illiberal democratic framework, while others remain committed to representative democracy. Recognizing these two distinct types of populist citizens helps to clarify the seemingly paradoxical finding by Wegscheider et al. (2023) that populists simultaneously endorse both direct democratic mechanisms and authoritarian governance. This duality reflects the inherent tensions within populist attitudes, which oscillate between a desire for unmediated popular sovereignty and an inclination toward strong, centralized authority.

While numerous studies acknowledge that authoritarian populists have come to dominate political systems in various countries across the globe, they often treat authoritarian populism as a mere subset of populism—one that has been distorted by an excessive concentration of power in the hands of a democratically elected strongman. Surprisingly, formal definitions of authoritarian populism—and even more so, of authoritarian populist attitudes—are remarkably limited in the existing literature. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (2017) observe that, beginning in the 1990s, populist radical right parties in Europe advanced their political agendas by crafting platforms that fused populism with two complementary ideologies: authoritarianism and nativism. This “marriage of convenience” between populism, authoritarianism, and nativism (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017, p. 34) has since been treated as a given in subsequent definitions of authoritarian populism. However, precisely because populist radical right parties have become adept at seamlessly blending these ideologies in their rhetoric, it becomes increasingly difficult to disentangle populism from authoritarianism and right-wing ideology or to delineate the boundaries of authoritarian populism with clarity (Wagner et al., 2024). Moreover, far too often, the presence of authoritarian populist attitudes is inferred from individuals’ support for populist radical right parties or their alignment with these parties’ anti-immigrant, nativist ideological positions (see, for example, Bartle et al., 2019). This conflation not only obscures the distinction between authoritarian populist attitudes and radical right ideology but also limits the ability to accurately measure and conceptualize authoritarian populism as a distinct phenomenon. A notable example is Norris and Inglehart’s (2019) influential work on cultural backlash and the rise of authoritarian populism in the West. Drawing on earlier arguments (Inglehart and Norris, 2017), they contend that support for authoritarian populist parties stems from a preference for social conformity, traditional moral hierarchies, and strong law-and-order orientation, values that stand in sharp contrast to liberal democratic norms such as pluralism, tolerance, and individual autonomy. They define authoritarian values as comprising conformity, security, and loyalty (Norris and Inglehart, 2019, p. 71) and conceptualize populism as a rhetorical style emphasizing people-centeredness and anti-elitism (Norris and Inglehart, 2019, p. 66). However, due to acknowledged data limitations, they operationalize populist attitudes using a scale measuring mistrust in politicians, parties, and parliaments.

2.2 Defining features of authoritarian populist attitudes

Fortunately, the recent works of Zürn (2022) and his colleagues (Wajner et al., 2024) help clarify the conceptual contours of authoritarian populism, providing valuable guidance for our operationalization of authoritarian populist attitudes below. Zürn (2022) builds on Lipset and Rokkan’s (1967) cleavage structure theory, arguing that the dual forces of globalization and Europeanization have generated a new societal cleavage that fuels the rise of authoritarian populist parties. While this argument echoes earlier contributions (see Hooghe and Marks, 2009; Kriesi et al., 2006), Zürn diverges from conventional scholarship by asserting that neither economic insecurity (Hobolt, 2016; Przeworski, 2019) nor cultural backlash (Norris and Inglehart, 2019) alone sufficiently explain the growing appeal of authoritarian populism. Zürn (2022, p. 798) conceptualizes authoritarian populism as a thick-centered ideology that is majoritarian, positioning the homogeneous will of the majority in opposition to liberal rights and pluralism. It is also inherently nationalist, emphasizing the protection of borders and the national will against the perceived threats posed by cosmopolitanism and non-majoritarian institutions (NMIs), such as central banks, international organizations, or constitutional courts. Consequently, authoritarian populism constructs a stark antagonism between the corrupt, distant cosmopolitan elite and the virtuous, local people. This perspective aligns with Norris and Inglehart’s (2019, p. 444) observation that authoritarian populists place minimal value on the international rules-based order and are skeptical of multinational cooperations.

Zürn’s (2022) definition of authoritarian populism provides a valuable framework for distinguishing between anti-establishment populism and authoritarian populism, as outlined by Bugaric (2019). In his analysis of the rise of populist movements over the past century, Bugaric (2019) contends that populism is Janus-faced, encompassing a variety of distinct forms, each with profoundly different political consequences. He classifies these forms into two broad categories: democratic and anti-establishment populism on one hand, and authoritarian populism on the other. The former blends elements of liberalism and democratic principles, advocating for greater inclusion and representation, while the latter is characterized by hostility toward the liberal international order, rooted in nationalism, protectionism, and the personalization of power.

For our purposes, the former aligns with the traditional ideational components of anti-elitism and people-centrism, coupled with a desire for greater direct democracy and enhanced accountability from established elites. The latter, however, is distinguished by a majoritarian conception of the popular will that seeks to marginalize opposition voices (Brubaker, 2017), prioritizes the protection of national interests, and places trust in a populist strongman as the embodiment of the people’s will. The tension between authoritarianism and anti-establishment politics has been a recurring theme in analyses of Latin American political development, from movements that emerged in the first half of the twentieth century such as Peronism, Varguism, and Cardenismo to more recent cases like Chavismo (Medina Echavarría, 1980; Freyre, 2003; Ebel and Taras, 2013). Zürn’s (2022) definition offers a crucial analytical advantage by allowing us to disentangle authoritarian populism from radical right-wing ideology, clarifying the conceptual boundaries between these overlapping but distinct phenomena.

In sum, we posit that there are two distinct types of populist citizens that come to support a populist strongman. The first type are the anti-establishment populists who are genuinely invested in enhancing democratic representation and restoring a voice to the “silent majority.” While disillusioned with the current state of democracy in their respective countries, this group remains committed to the principles of liberal democratic processes, viewing them as the most appropriate—if not ideal—means of addressing their grievances. Their support for populist parties often functions as a protest vote against the entrenched political establishment, aimed at dislodging established elites from power and replacing them with populist leaders who pledge to champion the interests of ordinary, hard-working citizens. The ultimate objective is to recalibrate the distribution of economic and political power away from supranational institutions and privileged elites and toward the “common people.” Importantly, this orientation does not inherently seek to permanently silence or exclude minority voices from the political process. Rather, it advocates for an enhanced role for the “silent majority” in decision-making, often through mechanisms such as referendums, which are perceived as a more direct and unmediated expression of the people’s will.

By contrast, the second type are the authoritarian populists, whose motivations are fundamentally different from those of their anti-establishment counterparts. Rather than seeking to enhance or safeguard democratic processes, authoritarian populists gravitate toward populist leaders precisely because these leaders advocate an exclusionary form of majoritarianism that aims to marginalize and punish out-groups for their perceived lack of conformity. As Norris and Inglehart (2019) argue, the rapid societal transformations of recent decades have triggered an “authoritarian reflex” in certain individuals—a response characterized by heightened anxiety and a desire to restore order in the face of perceived chaos. Convinced that the world is a dangerous and unpredictable place, and driven by fear of both further societal change and the “out-groups” they perceive as catalysts of this transformation, authoritarian populists seek out leaders who validate their anxieties and reinforce their belief that these out-groups are the root cause of societal decline. These leaders, in turn, offer simple, decisive solutions to complex problems and pledge to swiftly dispense justice against perceived enemies of the people. From our perspective, this unwavering attraction to the populist strongman—who embodies strength, decisiveness, and the promise of retribution—is the defining characteristic of authoritarian populist attitudes.

3 Data and methods

3.1 Data, cases, and items measuring populist attitudes

For the empirical analysis, we draw on data from the Varieties of Populist Attitudes (VoPA) public opinion survey. A random sample of one thousand respondents per country were invited to complete the survey from a set of partner panels based on the Lucid exchange platform, a high-quality source of public opinion data. The results were weighted by age and gender using Census information. The sample is geographically stratified to be representative of all nine countries. The data were collected in three waves spanning September 2022 to May 2024, beginning with Canada, the United States, France, and Italy (September–November 2022), followed by Hungary and Spain (November 2023–January 2024), and concluding with Poland, Brazil, and Argentina (March–May 2024).

We categorize our countries into three clusters. The first—France, Italy, the US, and Canada—has seen populism recently enter the mainstream from the right, driven by charismatic leaders (Wagner et al., 2024). US populism traces back to the 1890s Agrarian Populist Party, a left-wing movement uniting agrarians, miners, and industrial workers. While right-wing populism dominates today, figures like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez maintain a notable left-wing presence (Armaly and Enders, 2024). Canadian populism, though sharing an agrarian left-wing past with the US, is more centrist and less polarizing. Despite media comparisons between Trump and Poilievre, Canadian populism has not adopted the nativism and xenophobia of Trump’s Republican faction. French populism has been largely shaped by Marine Le Pen, whose emphasis on immigration has made her and her party emblematic of populism’s xenophobic and nativist tendencies. In Italy, while often likened to Trump, Meloni distinguishes herself from other populist strong(wo)men by moderating her Eurosceptic rhetoric, distancing herself from Vladimir Putin, and steering her party closer to the political mainstream.

Our second cluster—Spain, Brazil, and Argentina—has traditionally been associated with left-wing populism, often regarded as more inclusionary than its right-wing counterpart, fostering greater democratic engagement and pluralism (Stavrakakis and Katsambekis, 2014). It positions itself as a voice for marginalized groups, including the poor and ethnic minorities (Rooduijn and Akkerman, 2017), while advancing an economic populism that frames politics as a struggle between the working class and entrenched financial elites, corporate power, and neoliberal institutions (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017). However, the recent ascendance of Vox in Spain, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, and Javier Milei in Argentina challenges this narrative. Vox’s nativist rhetoric, Bolsonaro’s authoritarian populism, and Milei’s radical libertarianism signal a significant shift, blurring the historical association of these countries with left-wing populism.

The third cluster consists of post-communist Central European countries, specifically Hungary and Poland, where populism is defined by right-wing nationalism and illiberalism. Both have become synonymous with democratic backsliding, driven by authoritarian-leaning strongman leaders (Bernhard, 2021). The legacy of communist rule and state socialism has rendered left-wing governance largely unpopular in the region, entrenching populism as a predominantly right-wing phenomenon. Burgaric (2019) argues that populists in Hungary and Poland have institutionalized a new form of semi-authoritarianism through sustained attacks on the rule of law, civil liberties, media, and electoral rules. Kende and Krekó (2020) attribute the success of right-wing populism in the region to a fragile national identity rooted in experiences of weak sovereignty and socially accepted hostility toward ethnic minorities. They also suggest that populist citizens in these countries exhibit core conservative attitudes, driven by a desire for strong authority reminiscent of the socialist era.

This cross-national variation in the type of right-wing populism offers a crucial analytical advantage: it allows us to examine how support for populist strongmen is shaped by different populist attitudes across countries. While all selected leaders fit the mold of right-wing populist strong(wo)men, they vary significantly in terms of incumbency status, the radicalism of their rhetoric, and the extent to which political institutions constrain executive authority. For example, Pierre Poilievre in Canada and Marine Le Pen in France are opposition figures who channel widespread anti-elite sentiment but operate within institutional environments characterized by strong checks and balances on executive authority, and have not yet held office as Prime Minister or President. In contrast, leaders like Viktor Orbán in Hungary and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil have governed with a high degree of institutional control, using their positions to weaken checks and balances, undermine the judiciary, and centralize authority. Giorgia Meloni, while now Prime Minister of Italy, has moderated aspects of her rhetoric since taking office, especially on the European Union, suggesting a strategic adaptation to institutional constraints and coalition governance. Meanwhile, Javier Milei in Argentina, though newly elected, has built his public persona around dramatic anti-establishment gestures and a promise to dismantle state institutions, raising questions about how institutional limits will shape his presidency. These contrasts allow us to examine whether authoritarian or anti-establishment populist attitudes are more salient in contexts where populist leaders are challengers versus incumbents, or where institutions are more or less vulnerable to executive control.

This variation enables us to ask whether the same type of populist attitudes, anti-establishment or authoritarian, drives support across these different contexts, or whether the appeal of strongman leadership depends on specific national conditions. Are authoritarian populist attitudes more salient in contexts where leaders already wield executive power and face few institutional checks? Do anti-establishment populist attitudes dominate where populist leaders remain in opposition and position themselves as challengers to a corrupt elite? By holding constant the ideological orientation and the personalized leadership style of the figures under study, we isolate variation that is especially relevant to our theoretical question. We exclude left-wing populists not only for conceptual coherence but also because they typically promote pluralism, inclusion, and participatory governance, and rarely cultivate the authoritarian leadership persona that is central to our analysis.

Populist attitudes comprise a “set of political ideas” (Hawkins et al., 2012, p. 5) about the structure of power in society (Albertazzi and McDonnell, 2008). The majority of studies measuring populist attitudes differentiate between three distinct dimensions: anti-elitism, people-centeredness, and a Manichaean distinction between good and evil (see Castanho Silva et al., 2020). Scholars agree that the core element of populism is “the people” (Mudde, 2004; Brubaker, 2017) and their demands for greater (democratic) representation. Accordingly, for populists, politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people (Mudde, 2007). The calls for greater sovereignty of the people is not unique to populism, but also constitutes a core feature of liberal democracy. What moves these demands for greater sovereignty into the populist realm is when they are coupled with antagonism toward the established elites, who are frequently portrayed as corrupt and unresponsive to popular will. Taken together, anti-elitism and people-centeredness form the crux of anti-establishment populism (Schumacher et al., 2022). To account for these two dimensions, our measurement model includes two questions asking the extent to which respondents agree that (1) Politics is dominated by selfish politicians who protect the interests of the rich and powerful in society (anti-elitism) and (2) Citizens should have the final say on the most important political issues by voting on them directly in referendums (people-centrism).

The third dimension of populist attitudes—the Manichaean distinction—is open to contestation. In constructing a populist attitude scale, numerous studies contain a survey question that asks respondents to assess whether politics is ultimately a struggle between good and evil (Hawkins et al., 2012; Akkerman et al., 2014; Oliver and Rahn, 2016; Castanho Silva et al., 2018; Armaly and Enders, 2024). Akkerman et al. (2014, p. 1327) argue that populists have a very specific understanding of the people as not only sovereign but also as homogenous, pure, and virtuous. The elites, by contrast threaten the purity and unity of the sovereign people, hence the juxtaposition of the “pure” and “good” people with the “corrupt” and “evil” elites (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2014). Yet, in the work of Hawkins et al. (2012) and Akkerman et al. (2014), the two studies where the Manichaean distinction enters the populist attitudes lexicon, Manichaeanism loads poorly on the populist attitudes scale. For these reasons, we omit the Manichaean distinction from our operationalization of anti-establishment populism.

Regarding authoritarian populist attitudes, we conceptualize authoritarian populism—drawing on Zürn (2022) and Wajner et al. (2024)—as comprising three fundamental elements: majoritarianism, decisionism, and nationalism. We employ four survey items to capture these various dimensions of authoritarianism populism. First, to tap into majoritarianism, we use the question about the respondent’s agreement with the statement that—“The will of the majority should always prevail, even over the rights of minorities.” This survey item captures the populists’ opposition to institutional structures intrinsic to pluralism (Schulz et al., 2018), and reflects the notion that executing the “will of the people,” who by default form the majority, is the most important political objective (Taggart, 2000). Populist movements argue that the “silent majority,” long ignored by the political establishment, is the only legitimate decision-maker. This silent majority is a homogenous group that shares the same values and interests, and forms a coherent entity ready to withstand external threats (Albertazzi and McDonnell, 2008). We view majoritarianism as conceptually distinct from people-centrism. The beliefs that the people should have the final say in political decisions or that politicians should follow the will of the people—the linchpins of people-centrism—are more democratic in nature, and therefore more aligned with anti-establishment populism. Majoritarianism, on the other hand, reflects a more authoritarian impulse to impose the will of the majority on all dissenting voices that pose a threat to the homogenous nature of the populist’s group.

To operationalize decisionism, we use two survey items. The first examines the respondent’s support for strong and decisive leadership. Authoritarian populism supports transgressive strongman leaders and perceives legal rules and constitutional norms as obstacles to the swift exercise of authority that is demanded by the will of the people (Norris and Inglehart, 2019). For the populist leader to execute the will of the people, the formal structures of liberal democracy must be cast aside, lest traditional elites interfere and dilute the general will of the people (Bugaric, 2019; Erhardt and Filsinger, 2024). Accordingly, populism—and authoritarian populism particularly—“exhibits an elective affinity with plebiscitary politics and the personalization of power” which are perceived as the “best means for the direct and unmediated representation of the people” (Akkerman et al., 2014). Given our central argument that a defining characteristic of authoritarian populism is the strongman’s claim to embody the will of the majority against perceived outsiders, we include the following survey item: “Having a strong leader in government is good for the country, even if they have to make questionable decisions to achieve their goals.” This question serves to capture support for decisionist leadership—a core component of authoritarian populism.

Our second “decisionism” item pertains to elitism. The relationship between elitism and populism is, by some degrees, contradictory. On the one hand, the raison d’être of populism is to criticize and oppose elites. Conversely, elitism is rooted in the belief that the common people are incapable of making important political decisions and that the country would be better served if technocrats or experts were allowed to craft policy. On the other hand, Akkerman et al. (2014) point out that both populism and elitism share a disdain for politics as usual. Both populist and technocratic attitudes represent a rejection of the current workings of representative democracy as nonresponsive and irresponsible (Bertsou and Caramani, 2022). Furthermore, even though populists ostensibly call for more democracy, populist movements are often led by charismatic leaders and organized in highly centralized and personalized parties, suggesting that they, themselves, are elitist institutions at the upper echelons of power. Bertsou and Caramani (2022) corroborate this confounding relationship between populism and elitism, demonstrating that a large chunk of citizens who score high on populism invariably showcase strong preferences for technocratic expertise (see also Spruyt et al., 2023). This being the case, we anticipate a countervailing relationship between elitism and our two varieties of populist attitudes. We predict that anti-establishment populism, with its emphasis on enhanced democratic representation and reverence for the people, will be negatively correlated with elitism. Conversely, authoritarian populism should exhibit a strong, positive correlation with elitism, rooted in their mutual emphasis on expedient decision-making. Furthermore, much like elitists, authoritarian populists are skeptical that the citizenry, writ large, should have a say in important decisions, given that the citizenry also includes “outgroups” that are perceived as threatening to the populists’ agenda. Unlike anti-establishment populists, who are committed to upholding democratic norms, authoritarian populists are more willing to surrender decision-making to an authoritarian-style strongman and their cadre of elites. We measure this type of “technocratic elitism” (Spruyt et al., 2023) with a question about the sentiment that “Politicians possess the necessary technical knowledge to solve the country’s problems.”

Finally, we measure nationalism with a survey item that asks respondents the degree to which they self-identify as a nationalist. Rather than using a neutral question that queries about the respondent’s pride in her country or her attachment to her nation, we employ more aggressive langue, and define nationalism as identification with one’s nation and support for its interests, especially at the expense of other nations. We adopt this approach aiming to capture a more exclusionary form of nationalism, one aligned with the anti-globalist sentiments identified by Zürn (2022, p. 788), who notes that, “Authoritarian populists are also ‘anti-internationalists,’ since they unconditionally support national sovereignty and reject any political authority beyond the nation-state.”

Table 1 summarizes our survey measure of populist attitudes and designates each one as related to either anti-establishment or authoritarian populism. All but the nationalism survey items are on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher values indicating stronger agreement with the statement. The nationalism question uses an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (“not nationalist at all”) to 10 (“very nationalist”).

To test the merits of our conceptual framework, we begin with a principal component factor analysis (PCFA) of the six survey items listed in Table 1.1 We conduct separate analyses for each of the nine countries to examine how well our framework holds in different contexts. We employ varimax rotation to extract the components. Since a varimax rotation yields orthogonal components, we used it on an assumption of poor correlation between the two populist motivations we seek to identify. The PCFA produces two factors across our cases with an Eigenvalue larger than 1.

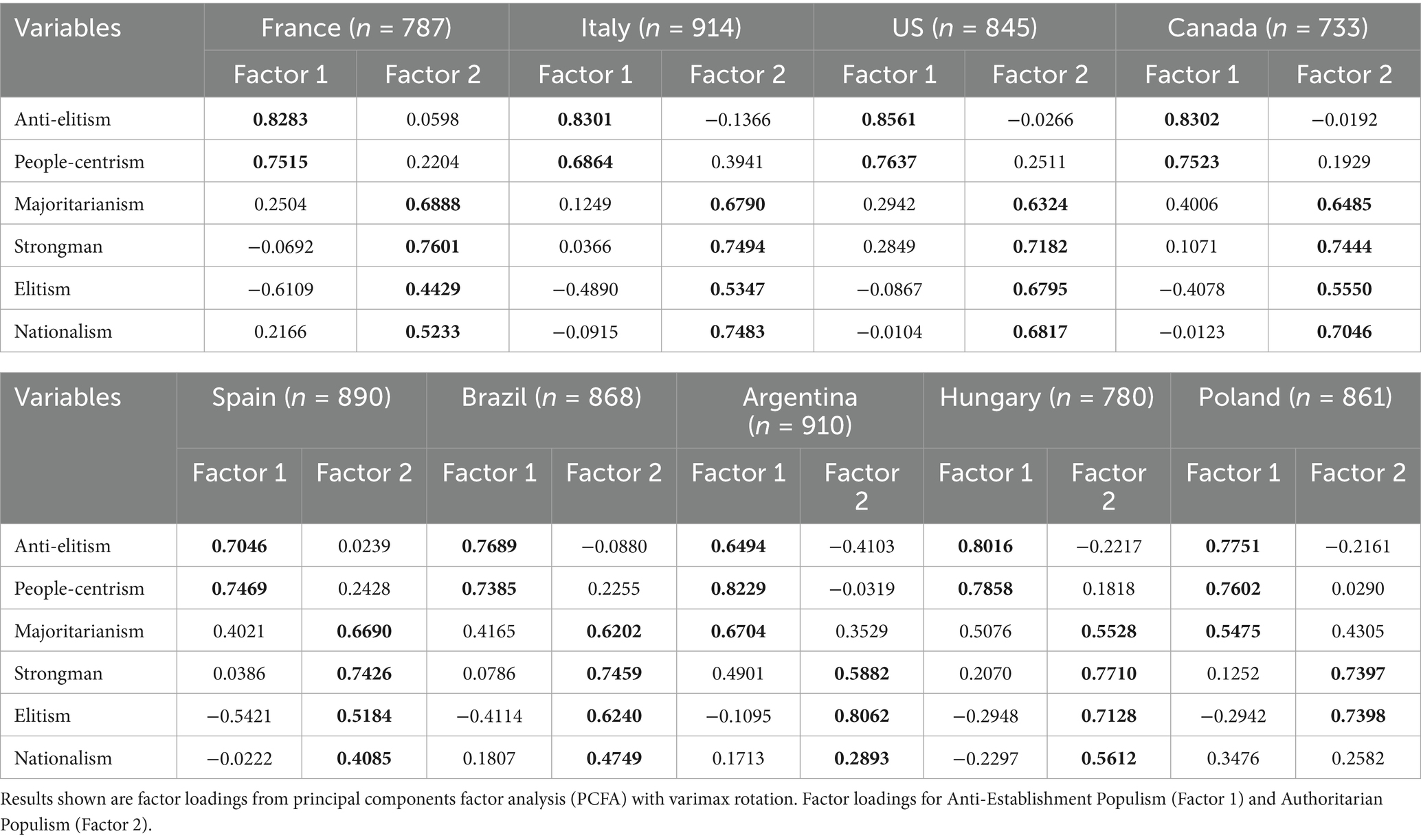

The results of the factor analysis, as presented in Table 2, confirm that there are, indeed, two types of populist attitudes. Despite the geographic, historical, and political differences reflected in our nine cases, we clearly see that anti-elitism and people-centrism load almost exclusively on the first factor. We consider this factor the anti-establishment variety of populist attitudes that is predicated on the primacy of the will of the people and a defiance of the establishment. Apart from Argentina and Poland, the variables measuring majoritarianism, strongman leadership, elitism, and nationalism consistently hang together on the second factor, which we label the authoritarian dimension of populist attitudes. In Argentina and Poland, majoritarianism loads more heavily on the first factor than the second, although there is sufficient cross-loading on both factors for us to retain our original measurement scheme. Additionally, the nationalism variable loads rather weakly on either factor in Argentina and Poland.

3.2 Dependent and independent variables

Our dependent variable captures the extent of political support for populist, radical-right leadership across the surveyed countries. This is measured through a survey item that asks respondents to indicate their level of agreement with the statement: “I prefer [NAME OF LEADER] to be the president/prime minister of [COUNTRY NAME].” Responses to this item are recorded on a five-point Likert scale, where higher values denote stronger support for the leader. The populist leaders, along with their party affiliations and the positions they held at the time of the survey, are detailed in Table 3.

This survey question offers several advantages over traditional vote intention measures, capturing nuanced support levels rather than reducing preferences to a binary choice. As Jacobs et al. (2018) note, many populist citizens vote strategically for non-populist parties. Our approach captures these attitudes while distinguishing support for individual leaders from party preference, which is especially relevant in parliamentary systems.

We assess two competing explanations for support for populist leadership: populist attitudes and ideological alignment with issues central to radical-right parties and their platforms. A persistent challenge in disentangling the influence of populist attitudes lies in their latent conflation with host ideologies and overlapping concepts such as nativism and protectionism (Hunger and Paxton, 2022). This conflation complicates efforts to determine whether populist attitudes independently drive support for populist leaders and parties or whether voters are primarily drawn by radical-right ideological commitments.

Thus, our main independent variables of interest are anti-establishment and authoritarian populist attitudes, operationalized through factor scores derived from our factor analysis presented in Table 2. Recognizing populism as a multidimensional phenomenon, Schulz et al. (2018, p. 318) caution that relying on unidimensional scales (e.g., Hawkins et al., 2012; Akkerman et al., 2014; Elchardus and Spruyt, 2016) obscures critical distinctions between varieties of populist attitudes. We consider factor scores to provide the most precise measure of respondents’ affinity for specific types of populism. This approach allows the six populism-related items to load with varying degrees while maintaining the interpretability of the composite scores. The resulting factor scores for anti-establishment and authoritarian populist attitudes are standardized with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. Given that we employ orthogonal rotation (i.e., varimax rotation) to derive the factor scores, the anti-establishment and authoritarian populist attitudes variables are explicitly uncorrelated with one another across our nine cases, (Pearson’s r = 0.00).

To capture the respondent’s ideological affinity to radical-right policies, we rely on three additional survey questions. The first assesses opposition to immigration—the cornerstone of the radical right’s platform (Rydgren, 2007; Mudde, 2007)—by asking whether respondents believe immigrants increase crime rates. The second captures cultural backlash, as theorized by Norris and Inglehart (2019), who argue that the rise of radical-right parties is fueled by mass immigration and multiculturalism, which some perceive as threats to societal cohesion. Cultural backlash is measured through a survey item asking respondents whether they agree that “Cultural diversity limits my opportunities in [country X].” The third question gages egocentric victimhood (Armaly and Enders, 2024), or what Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (2018) call “social envy.” Studies show that radical right populist parties attract voters who score high on measures of relative depravation (Burgoon et al., 2019). These individuals may not face absolute economic hardship but perceive themselves as falling behind while others, particularly minorities, reap the benefits of government programs and job opportunities. Radical right parties exploit these grievances, appealing to those marginalized by globalization—the so-called “losers of modernization” (Betz, 1994)—by highlighting the failure of mainstream parties to address economic inequality and often advocating for protectionism and economic nationalism. Social envy is measured through a survey item asking whether “Other [nationality] citizens have more opportunities for economic success than I do.” All three items are assessed using a five-point Likert scale, with higher values indicating greater levels of xenophobia, cultural backlash, and social envy.

Another key driver of public support for populist radical-right parties in Europe is euroscepticism (Hobolt, 2016; Burgoon et al., 2019; Brigevich, 2020), with opposition to European integration being a hallmark of the radical right’s political agenda (Fagerholm, 2018). Radical parties and their supporters oppose European integration on both economic and cultural grounds, viewing the EU’s open-border policy as a catalyst for immigration that erodes national culture and undermines employment opportunities for citizens. In the five EU member states surveyed—France, Italy, Spain, Hungary, and Poland—we assess hard Euroscepticism (Taggart and Szczerbiak, 2004) through a survey item measuring respondents’ support for their country’s withdrawal from the EU, using a five-point scale. We anticipate that opposition to the EU and its policies extends beyond Europe, finding fertile ground in other regions. In North America, the EU is often depicted as a globalist, overly bureaucratic entity that undermines national sovereignty and imposes undemocratic progressive agendas. In Latin America, critics frame the EU as an imperial, hegemonic bloc and a vehicle for neoliberal capitalism. These anti-EU sentiments align with Zürn’s (2022) argument that international organizations, due to their non-majoritarian nature, are increasingly viewed as instruments of liberal cosmopolitan elites and adversaries of the “pure people.” Accordingly, we probe our North and South American respondents for their perspectives on the EU. In the US and Canada, respondents rated their preference for less versus more European Union on a five-point scale, while in Brazil and Argentina, they expressed their favorability toward the EU on a four-point scale, with higher values in both cases indicating greater opposition.

We further investigate the extent to which racial resentment and cultural grievances shape support for populist radical-right leaders. Armaly and Enders (2024) demonstrate that individuals with the most pronounced populist orientations perceive their salient in-groups—both religious and racial—as experiencing relative marginalization. This aligns with the radical right’s declaration of a “War against Woke,” a crusade against government policies aimed at addressing systemic discrimination against ethnic, racial, and sexual minorities (Dorey, 2024). Wokeism is characterized by a liberal emphasis on minority rights and marginalized groups, coupled with a commitment to critical theories aimed at dismantling the status quo and reinforcing the oppressor/oppressed binary (Valentin, 2023). Consequently, wokeism imposes a moral imperative on majority groups to acknowledge and atone for their positions of privilege. While the culture war against wokeism is particularly pronounced in the US, UK, and Canada (McCurdy et al., 2025), radical-right parties in Europe have also entered the discourse by embracing, rather than repudiating, their countries’ colonial histories, while concurrently attributing national decline to immigration and multiculturalism (Griffini, 2023). We use a survey item asking respondents whether they agree that their country is racist (5-point scale) and expect supporters of populist radical-right leaders to reject this claim and its implicit “woke” premise of majority privilege.

Lastly, we include several typical voting behavior control variables. To capture general mistrust in mainstream institutions, we use a question on whether the media increasingly broadcasts fake news (5-point scale), a recurring theme in radical-right rhetoric (Knops and De Cleen, 2019). We further control for ideology (11-point, general left–right scale), income, education, age, and gender. We anticipate that supporters of the populist leaders analyzed will lean strongly to the right and that males will show higher levels of support, consistent with evidence of a gender gap in populist voting (Spierings and Zaslove, 2017).

3.3 Results

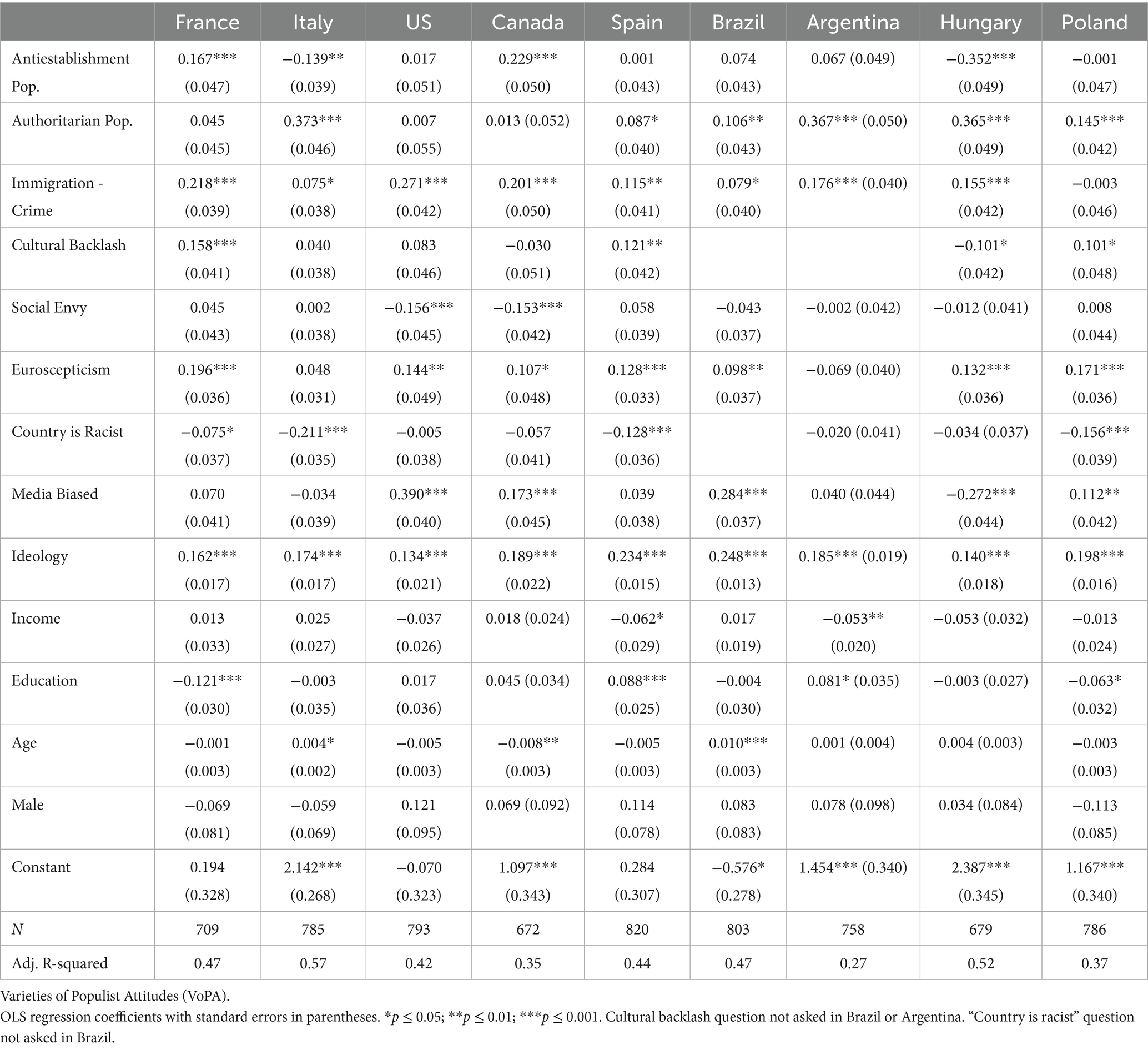

Following Erhardt and Filsinger (2024), who argue that populist attitudes are context-dependent—given the historical and ideological diversity of populism across nations—we conduct separate regressions for each of the nine cases, presented in Table 4. A test of multicollinearity shows that the variance inflation factor (VIF) scores across all nine models are below 2, indicating negligible levels of multicollinearity. As such, our regression estimates are likely to be stable and interpretable. In all but one country—the US—populist attitudes exert a significant impact on support for a populist strongman, independent of radical-right ideological preferences. The results provide clear evidence supporting our argument that there are two distinct types of populist attitudes that lead individuals to support for a populist strong(wo)man.

In France and Canada, this support is primarily driven by anti-establishment populism, whereas authoritarian populism emerges as the dominant force in Italy, Spain, Brazil, Argentina, Hungary, and Poland. While Armaly and Enders (2024) rightly assert that there are no universal pathways to populism, our findings suggest that authoritarian populist attitudes, overall, are the primary drivers of support for populist radical-right leaders. Notably, the two varieties of populism exert mutually exclusive effects on strongman support. In none of our cases do anti-establishment and authoritarian populism simultaneously increase (or decrease) such support. Instead, these forms of populism occupy opposing ends of a continuum, underscoring that populist attitudes are structured along a democratic-authoritarian cleavage (Gagnon et al., 2018). This divide is most pronounced in Italy and Hungary, where a positive and statistically significant coefficient for the authoritarian populism variable is accompanied by a negative and significant coefficient for anti-establishment populism.

In France and Canada, support for Le Pen and Poilievre is driven by a pronounced demand for enhanced democratic representation in response to perceived political corruption. The anti-establishment populism variable exhibits a statistically significant and positive effect in both contexts, with democratic sentiment particularly robust in Canada, where the authoritarian populism variable is both significant and negative. This outcome is not entirely unexpected in the case of Le Pen, despite her frequent inclusion in media lists of populist strong(wo)men (Ellyatt, 2025; Kurlantzick, 2017). Le Pen and her party, the RN, have historically advocated for referendums and ballot initiatives, arguing that these instruments empower the people by allowing them to exercise direct, unmediated authority (Ivaldi et al., 2017). Simultaneously, Le Pen has made significant strides in normalizing her party and softening her image (Startin, 2022; Mayer, 2022), thereby avoiding the strongwoman persona that typically appeals to authoritarian populists.

Similarly, Poilievre’s appeal is anchored more firmly in anti-establishmentarianism than in cultivating the persona of a populist strongman (Beauchamp, 2024). A dominant figure within the Conservative Party, Poilievre swiftly ascended to its leadership by aligning himself with the Freedom Convoy protest against COVID-19 mandates. Since then, his distinct brand of Canadian prairie populism has been characterized by sharp critiques of Trudeau’s government for perceived overreach and of financial institutions for allegedly betraying the working class (The Canadian Press, 2023). Poilievre’s rhetoric resonates with voters disillusioned by traditional elites, offering a vision of restoring power to ordinary Canadians. Unlike archetypal strongman figures who rely on overt authoritarianism and centralized control, Poilievre channels his populist energy toward dismantling perceived institutional corruption and advocating for decentralized governance, further distancing himself from the authoritarian strain of populism.

In contrast, support for Meloni in Italy is firmly anchored in authoritarian populism and a rejection of anti-establishmentarianism—both of which are unsurprising. Unlike Le Pen and Poilievre, Meloni holds the position of Prime Minister, and her party, Fratelli d’Italia (FdI), is a dominant force within a coalition government alongside other populist right-wing parties. Consequently, the negative coefficient for anti-establishment populism is expected, as Meloni and her cohort of populist politicians have transitioned from insurgents to the establishment. Their consolidation of power has tempered the perception that politicians are inherently corrupt, reflecting a shift in public sentiment. This result aligns with Jungkunz et al.’s (2021) findings that populism operates as a “thermostatic” attitude, expressing a demand for change that diminishes once that change is realized. While populist citizens may initially accuse elites of acting against the people’s interests, this grievance tends to subside once their populist leader ascends to power. Second, Meloni has carefully cultivated a strong(wo)man persona, presenting herself as a decisive leader (Melito and Zulianello, 2025) focused on safeguarding national security, particularly in response to the ongoing migrant crisis (Sondel-Cedarmas, 2022). Her leadership of Fratelli d’Italia (FdI) reinforces the perception of a strong(wo)man at the helm of a law-and-order party, whose political agenda is anchored in the triad of “God, homeland, and family” (Donà, 2022). This emphasis on traditional values, combined with a focus on stricter laws and societal order, resonates with the authoritarian worldview, solidifying Meloni’s support as a manifestation of authoritarian populism.

Abascal, leader of Spain’s Vox, has meticulously crafted a strongman persona, positioning himself as the defender of traditional Spanish values and against perceived threats to national identity. His rhetoric emphasizes the need to restore order, protect national sovereignty, and combat what he portrays as the destabilizing forces of multiculturalism and progressive ideology. Under Abascal’s leadership, Vox has pledged to “make Spain great again” (Turnbull-Dugarte, 2019), echoing the populist rhetoric of Donald Trump. He relentlessly targets his political adversaries—particularly the Spanish left and separatist movements—often branding them as criminals and terrorists intent on dismantling the Spanish state (Cervi et al., 2023). Empirical evidence suggests that populist attitudes play a significant role in driving support for Vox (Marcos-Marne, 2021; Ramos-González et al., 2024), further cementing Abascal’s position as a strongman figure in Spanish politics. His tough stance on immigration, his calls for harsher penalties for criminals, and his opposition to regional autonomy, particularly Catalan separatism, further reinforce his image as a decisive and uncompromising leader. By invoking themes of patriotism, security, and cultural preservation, Abascal channels authoritarian populism, in line with our expectations.

Bolsonaro and Milei have firmly established themselves in the media as populist strongmen, though their distinct brands of right-wing populism diverge considerably. Bolsonaro is often depicted as a quintessential authoritarian populist, bearing striking similarities to Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán (Farias et al., 2022). Indeed, numerous parallels have been drawn between the erosion of democratic norms during Bolsonaro’s presidency in Brazil and Trump’s tenure in the United States. Both leaders have waged relentless attacks on the political establishment, vilified their opponents, undermined trust in electoral processes, and incited political violence among their supporters (Pion-Berlin et al., 2023; Molas, 2023). Bolsonaro epitomizes the archetype of a right-wing authoritarian, as evidenced by his relentless advocacy for draconian law-and-order policies, his inflammatory denigration of racial and sexual minorities, and his zealous promotion of religious nationalism—best encapsulated by his campaign slogan, “Brazil above everything, God above everyone” (do Nascimento Cunha, 2023). Our findings indicate that Bolsonaro supporters are clearly authoritarian populists and not anti-establishment ones.

Argentina’s Milei offers a compelling case study in the evolving nature of right-wing populism, which adapts to the unique socio-political contexts of individual countries. Milei deliberately cultivates a public persona as El Loco (the Madman), wielding a chainsaw as a theatrical symbol of his radical economic agenda aimed at slashing government spending, dismantling bureaucracy, and eliminating the entrenched “political caste” (Rojas, 2024). Milei’s specific brand of populism defies easy classification, as he refrains from criticizing immigration, adopts a libertarian stance on social issues, and advocates for globalist, pro-market policies. Consequently, scholars have characterized his ideological position, paradoxically, as either “libertarian populism” (Heinisch et al., 2024) or “managerial populism” (Del Pino Diaz, 2024). It is somewhat surprising, then, that anti-establishment populism proves to be a weak predictor of support for Milei, whereas authoritarian populism—with its strong emphasis on exclusionary nationalism—exerts a significant influence. Milei’s flamboyant public persona has enabled him to convincingly craft the image of a strongman uniquely capable of dismantling the deeply entrenched corruption in Argentina, which he attributes to the failures of both leftist governance and previous neoliberal policies.

In Central Europe, support for both Orbán and Duda is predominantly driven by authoritarian populist attitudes. Orbán has gained (in)fame for promoting his vision of illiberal democracy, which repudiates Western liberalism and multiculturalism in favor of nationalism and conservative Christian values. He has distinguished himself through his sustained assaults on perceived “elites” outside his government—journalists, academics, and the media—whom he accuses of orchestrating conspiracies against him. Moreover, his populist rhetoric has increasingly targeted Brussels, depicting the EU as a bureaucratic empire determined to subvert national sovereignty and erode traditional cultural values (Csehi and Zgut, 2020). Central to Orbán’s narrative is the idea that Hungary must defend itself from external forces seeking to impose progressive ideologies that threaten the nation’s Christian heritage and societal cohesion. His government has implemented sweeping reforms to consolidate power, weaken judicial independence, and curtail press freedoms, all under the guise of protecting Hungary from foreign interference.

Compared to Orbán, Duda has attracted less academic and media scrutiny, as the populist spotlight in Poland has largely centered on Jarosław Kaczyński, the long-standing leader and co-founder of PiS. Nevertheless, Duda has firmly established himself as a populist strongman in his own right, skillfully navigating the political landscape to consolidate his authority while aligning closely with Kaczyński’s nationalist and conservative agenda. Since ascending to the presidency in 2015, Duda has played a central role in advancing judicial reforms that have provoked intense criticism from the European Union for eroding the foundations of Polish democracy (Korinteli, 2022). He further inflamed these tensions during his 2020 presidential campaign by resorting to strident anti-LGBTQ rhetoric, portraying sexual minorities as proponents of a “destructive” ideology (Jungkunz et al., 2021) and tacitly endorsing the creation of “LGBT-free zones” across various municipalities. His populist appeal is firmly anchored in PiS’s core electorate—a constituency that is deeply conservative, predominantly rural, and economically marginalized—making them especially susceptible to the authoritarian strain of populism.

Only in the United States do neither type of populist attitudes predict support for a populist leader—an outcome that is perhaps our most unexpected, given that Trump epitomizes the archetype of a populist strongman. However, Trump’s support in the 2016 election has been attributed to a complex interplay of factors, including racial resentment (Tolbert et al., 2018), economic grievances (Ferguson et al., 2020), and anti-immigration sentiment (Donovan and Redlawsk, 2018). These findings align with Inglehart and Norris’s (2017) cultural backlash thesis, which suggests that support for Trump reflects a defensive reaction against rapid social change and perceived erosion of traditional values. In such contexts, strongman appeals resonate not because of populist attitudes, but because they promise to restore a familiar moral and cultural order. Recent findings by Dai and Kustov (2024) similarly demonstrate that during the 2016 American elections, Trump’s populist rhetoric did not resonate as strongly with voters exhibiting populist attitudes. Instead, his electoral appeal was more closely tied to his perceived moderation on economic issues and his hardline stance on immigration.

Beyond differentiating between anti-establishment and authoritarian populist attitudes, we are particularly interested in examining Jungkunz et al.’s (2021) claim that the anti-elitism dimension of populist attitudes most accurately predicts support for populist leaders and parties when they remain in opposition. This analysis presents a valuable opportunity to explore whether anti-elitism continues to exert significant influence once populist actors move from the periphery to positions of power. Once populist leaders ascend to positions of power, they cease to be perceived as political outsiders. Consequently, their supporters become “unlikely to agree with statements about the corruption of political leaders; having installed their preferred leaders, they no longer consider political leaders to be the major problem of the country or to be conspiring against the good and honest people” (Jungkunz et al., 2021, p. 13). This shift reflects a broader tendency wherein populist supporters, having succeeded in elevating their chosen leaders, experience a decline in anti-elitist sentiment as their leaders become synonymous with the establishment they once denounced. In such cases, populist attitude scales fail to accurately capture populist sentiments and, consequently, lose their predictive power in forecasting populist vote choice. Our findings partially validate this argument. Populist leaders who held executive office at the time our surveys were conducted—Meloni, Orbán, Duda, and Milei—did not attract anti-establishment populists and, in fact, actively repelled them in the cases of Meloni and Orbán. This suggests that once populist leaders transition from insurgent challengers to incumbents, they lose their appeal to anti-establishment voters who perceive them as part of the very establishment they once opposed. Conversely, two of the three populist leaders who were in opposition and had never held the office of prime minister—Le Pen and Poilievre—derived their support primarily from anti-establishment populist sentiment.

Turning our attention to the variables capturing the core principles of radical right ideology, we find that anti-immigrant sentiment is a significant predictor of support for populist leadership in all cases except Poland. This anomaly is likely due to the timing of the Polish survey, which was conducted in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—a period when Poland extended refuge to millions of Ukrainians. Given the historical affinity between Poles and Ukrainians, this humanitarian response may have temporarily muted anti-immigrant sentiment. Furthermore, this outcome is consistent with the findings of Olejnik and Wroński (2025), who demonstrate that anti-immigrant sentiment does not significantly predict voting for populist parties in the Polish context. Empirical support for Norris and Inglehart’s (2019) cultural backlash thesis emerges only in France, Spain, and Poland. This is expected in France, where Le Pen routinely leverages Islamophobic rhetoric to mobilize her supporters. However, it is puzzling that the cultural backlash variables do not reach statistical significance in cases such as the United States and Canada, where growing skepticism about the benefits of multiculturalism has recently gained prominence. Paradoxically, despite Orbán’s relentless campaign against cultural diversity and progressive values in Hungary, respondents who score high on cultural backlash are less likely to support him. Conversely, in Poland, where PiS and Duda have pursued a similarly aggressive, and at times even more draconian, campaign—particularly concerning LGBTQ rights—high levels of cultural backlash strongly predict support for Duda. Social envy emerges as the weakest predictor of support for populist leadership across our nine countries, achieving statistical significance only in the United States and Canada—and, surprisingly, with a negative effect. One plausible explanation is that social envy, as an expression of economic grievance, may be more effectively addressed through support for left-wing populist parties and candidates, whose platforms are traditionally more attuned to addressing socioeconomic inequality.

One of the most robust findings across our nine countries is that Euroscepticism serves as a significant predictor of support for populist leadership, even in non-EU countries. The only exceptions are Italy and Argentina, where the Euroscepticism variable fails to achieve statistical significance. In Italy, this is likely due to Meloni’s recent moderation of her anti-EU rhetoric, adopting a more pragmatic and cooperative stance following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and recognizing Italy’s reliance on substantial EU funding through its post-COVID national recovery and resilience plan. Milei, of course, is a self-proclaimed anarcho-capitalist, making it unsurprising that his supporters would favor the globalist, neoliberal orientation of the EU. In contrast, our proxy for wokeism—the “our country is racist” variable—yields more nuanced results. It demonstrates the strongest predictive power in Western Europe and Poland, where respondents who agree that their country is racist are significantly less likely to support populist radical-right leaders. This outcome is expected, particularly in countries like Poland, where radical-right parties have promoted revisionist historical narratives, leading their supporters to reject such statements. However, we anticipated a stronger negative correlation between racial guilt and support for Trump and Poilievre, given the heightened polarization surrounding wokeism and cancel culture in North America.

Lastly, we examine our control variables. Mistrust of the media emerges as a significant and positive predictor of support for populist leadership in the United States, Canada, Brazil, and Poland. This is unsurprising, as both Trump, Poilievre and Bolsonaro have relentlessly attacked the media, while PiS has similarly cultivated distrust, particularly toward foreign-owned news outlets. Across all nine countries, supporters of populist radical-right leaders consistently identify as ideologically right-wing. However, no clear patterns emerge concerning the effects of income, education, or age. Notably, the gender gap in support for populist leadership appears to have closed, as the male dummy variable fails to achieve statistical significance in any of the nine cases.

In sum, our findings reveal that authoritarian populism is a more significant and consistent explanatory factor in predicting support for populist radical-right leaders across our cases than anti-establishment populism. The influence of authoritarian populist attitudes remains robust even after accounting for radical-right ideological predispositions, underscoring the salience of authoritarian populism as a core driver of populist strong(wo)man support. Beyond populist attitudes, anti-immigrant sentiment and Euroscepticism emerge as the most reliable predictors of populist radical-right support, demonstrating their importance in shaping voter preferences. Moreover, the relative weakness of anti-establishment populism in driving support for populist leaders in power highlights a crucial dynamic: once populist actors become part of the political establishment, appeal to anti-elitist sentiments diminishes.

4 Discussion and conclusion

In this analysis, we aimed to explore the relationship between individual-level populist attitudes and electoral support for populist leaders characterized by strongman tactics. Rather than being a panacea or a corrective to the deficiencies of undemocratic liberalism, populist governance all too frequently precipitates the corrosion of democratic systems (Ruth-Lovell and Grahn, 2023). Weyland (2021) argues that populist leaders engage in a “fiction of representation via identity,” claiming to embody the people directly rather than representing them through democratic institutions, thereby blurring the distinction between leader and masses. This confers them a great deal of latitude, “which in their opportunistic power hunger they commonly use to DIS-empower the people by suffocating democracy, populism’s inherent danger” (Weyland, 2021, p. 186). This rendition of populism raises questions about the underlying motivations of the average populist citizen. Are they simply pawns in the leader’s power grab, seduced by the assurance of direct representation that never comes to fruition? Or are they active participants in a mutually reinforcing relationship with the strongman leader, enamored by his promise to defend their group’s interests at all costs, even if that cost is democracy?

We contend that the current conceptualization of populist attitudes does not allow us to sufficiently capture the range of motivations that draw populist citizens to populist strongmen. The dominant ideational approach to measuring populist attitudes is focused on operationalizing the three definitional components of populism derived by Mudde (2004): anti-elitism, people-centrism, and the Manichaean distinction between good and evil. Putting aside the Manichaeanism component, which has been frequently found to load on a separate dimension in various factor analyses of populist attitudes (Akkerman et al., 2014; Hawkins et al., 2012), we argue that anti-elitism and people centrism are best-suited to measure only one specific type of populist attitude—anti-establishment populism. This type of populist attitude does not reject liberal democratic processes but pushes for direct democracy as a means to return the voice back to the people in the face of unresponsive elites. For anti-establishment populists, a vote for a populist strongman is not intended as a carte blanche to exclude minority voices from the political process (i.e., anti-pluralism) or to pursue their group’s agenda at all costs. Rather, it is a protest-vote that aims to shake up the political status quo.

The contribution of this article is to advance a conceptualization of populist attitudes that moves beyond the definitional elements of the ideational approach and to demonstrate that populist attitudes come in two varieties. In stark contrast to anti-establishment populism stands the authoritarian variety, which does aim to subvert the liberal democratic order. Authoritarian populism, although not a new concept, has suffered from a lack of precise conceptual definitions.

Although numerous studies recognize populism’s potential to devolve into authoritarian forms, few clearly delineate what distinguishes authoritarian populism from its less pernicious variants. Fortunately, recent scholarship by Zürn (2022) and Wajner et al. (2024) provides a compelling framework, defining authoritarian populism as rooted in majoritarianism, nationalism, and the call to delegate substantial authority to the populist leader. Building upon this definition, we can attain a more comprehensive understanding of the motivations driving authoritarian populist voters. Authoritarian populists are not concerned with preserving the liberal democratic process, but turn to populist leaders precisely because they advocate an exclusionary form of majoritarianism that privileges their in-group in the face of non-conforming out-groups.