- Instituto Complutense de Ciencia de la Administración de la UCM (UCM-ICCA), Madrid, Spain

Since the late 1970s, there has been a general trend toward a decline in electoral participation in European democracies. That tendency is especially acute if we refer to young people, who find no means to carry their demands to the public authorities. This downward trend in citizen participation in elections has occurred at the same time that European countries have experienced an overall increase in the socioeconomic level and educational background of the population, factors traditionally associated with greater electoral participation. This constant decline, together with other processes, has led to this situation being described as a “crisis of representative democracies.” To alleviate this crisis, many countries have proceeded to use innovative formulas to try to incorporate citizens into decision-making processes. On the one hand, the advance in communication technologies is allowing not only greater access to information, but also increasing the possibilities of both direct interaction with citizens and the ability to respond to simple demands. On the other hand, a part of the population increasingly demands that their proposals be taken into consideration, not only as a democratic right, but also as a tool for more effective management. In this article, we explore the implementation of two specific experiences at the local level with young people, evaluating their impact in small towns in Sierra Norte and the challenges they present for municipalities that wish to implement them in a post-pandemic context. We present the methodology used to conduct them and the main findings that might help to reproduce these initiatives.

1 Introduction

Since the late 1970s, there has been a general trend toward a decline in electoral participation in European democracies (Mair, 2013; Giugni and Grasso, 2022; Cancela, 2023). This downward trend in citizen participation in elections has occurred at the same time that European countries have experienced an overall increase in the socioeconomic level and educational background of the population, factors traditionally associated with greater electoral participation (Lipset, 1960; Verba et al., 1978; Putnam et al., 1994; Lijphart, 1997; Schlozman and Brady, 2022). This constant decline, together with other processes, has led to this situation being described as a “crisis of representative democracies” (Rosanvallon, 2011; Manin, 2017; Tormey, 2014; Innerarity, 2019; Dryzek et al., 2019).

To alleviate this crisis, many countries have proceeded to use innovative formulas to try to incorporate citizens into decision-making processes (Font et al., 2000). In this regard, even the European Union has joined the application of these techniques, as we could witness with the Conference on the Future of Europe, with various results (Markowicz and Tosiek, 2023). On the one hand, the advance in communication technologies is allowing not only greater access to information, but also increasing the possibilities of both direct interaction with citizens and the ability to respond to simple demands. On the other hand, a part of the population increasingly demands that their proposals be taken into consideration, not only as a democratic right, but also as a tool for more effective management.

Citizens’ participation allows the objectives of public policies to be adapted to the needs of the group to which the public policy is aimed (Font et al., 2000). These objectives are thus redefined in accordance with citizen preferences, which promote the efficiency of public spending. Indeed, possible problems in implementation are anticipated, and alternatives that were not foreseen by public officials are proposed. In summary, certain spending can be reduced (and even eliminated) by anticipating peoples’ demands, and the programs implemented can be evaluated and adapted to the needs of the population.

The implementation of these citizen participation processes has been done fundamentally at the local level, as isolated political initiatives, generally without an adequate evaluation of the impacts of using one or another formula. However, in this study, we wonder to what extent the use of these techniques, particularly deliberative ones, is suitable for easing the incorporation of young people into participatory processes.

To do this, we will start from our experience in the implementation of two specific projects of Participatory Action Research (PAR) at the local level, evaluating their impact and the challenges they present for municipalities that wish to implement them. Both projects aimed to shed light on the new forms of young people’s participation, their level of involvement, and their needs after the COVID-19 crisis in the new post-pandemic reality, so that they can tackle the particular needs of young people living in Sierra Norte in Madrid.

In this research, we first review the theoretical approaches to the analysis of the political participation. Second, we introduce the context in which young participation takes place. Third, we present our methodological framework. Fourth, we describe the results of our project. Finally, we discuss the main conclusions of this study.

2 Political participation in an ever-changing context

Legitimacy and participation are at the core of the debate of what a political system is and how it can be classified (Soto Sainz, 2020). Indeed, there are numerous theoretical debates about what participation is and what it is not, as well as the numerous classifications of the forms of participation. According to Verba et al. (1972, p. 2), “political participation refers to those activities by private citizens that are more or less directly aimed at influencing the selection of governmental personnel and/or the actions they take.” This broad approach incorporates the actions of social participation into their political possible outcomes. The concept of participation has a basic distinction based on the level of implication. On the one hand, participation can be assimilated to taking part, which means being involved in some type of event. On the other hand, participation can be referred to as being part, that is, being a member of a group that directs the actions carried out. On that basic distinction, we have several layers of involvement in a participatory process that can also be taken into account in political participation. To get a more specific approach to the subject, we will be dealing first with the types of social and political participation and how they can combine. Second, we will address the issue of electoral participation. Third, we will address the role of young people in the participatory process, paying special attention to deliberative methods.

2.1 Types of social and political participation

To specify the concept of political participation, Conge (1988) departs from a critique of Verba and Nie’s definition, stating that it is too narrow and, thus, it does not cover some forms of participation. That way, Conge (1988, p. 245) distinguishes a series of six dimensions to be considered to organize the debate about political participation:

(1) Active versus passive forms. This divides between the action of voting and campaigning for a cause and more passive forms, such as the feeling or awareness toward political issues.

(2) Aggressive versus non-aggressive behavior. This incorporates into the definition of political participation attitudes, such as civil disobedience and political violence, against more conventional activities that do not imply breaking the law.

(3) Structural versus non-structural objects. Here, the author differentiates between efforts to change or maintain the form of government and efforts to change or maintain governmental authorities and/or their decisions.

(4) Governmental versus non-governmental aims. The author contrasts behavior directed toward governmental authorities, policies, and/or institutions with phenomena outside the realm of government.

(5) Mobilized versus voluntary actions. This aspect considers behavior sponsored and guided by the government to enhance its welfare, as opposed to behavior initiated by citizens in pursuit of their goals.

(6) Intended versus unintended outcomes. In this dimension, the author opposes intended and unintended consequences for a government.

In this debate, Conge (1988, p. 247) takes a stand and defines finally political participation as the “individual or collective action at the national or local level that supports or opposes state structures, authorities, and/or decisions regarding allocation of public goods.” Thus, actions can be verbal or written, violent or non-violent, and of any intensity.

Following Cunill Grau (1991) and Villarreal Martínez (2009, p. 32) proposes a division between social, community, political, and citizen participation. In this model, social participation is the one “which occurs due to the individual’s membership in associations or organizations for the defense of the interests of their members, and the main interlocutor is not the State but other social institutions” (Villarreal Martínez, 2009, p. 32). On the other hand, this author sees the community participation as “the involvement of individuals in collective action aimed at the development of the community by meeting the needs of its members and ensuring social reproduction” (Villarreal Martínez, 2009, p. 32). In reality, there is little difference between the two definitions, since collective action is impossible without organizations, whether formal or informal, to carry out the objectives proposed by the individuals. Therefore, Villareal shows that formal and informal participation should be considered separately because of their distinct implications, but in the framework of this study, we will understand both as one and the same: social participation, whether formal or informal.

Villarreal Martínez (2009, p. 32) considers that “political participation comprises citizens’ involvement in the formal organizations and mechanisms of the political system: parties, parliaments, city councils, elections.” Thus, this form of participation is mediated by the mechanisms of political representation. In addition to that, we have citizen participation “when citizens are directly involved in public actions, with a broad understanding of politics and a vision of public space as a space for citizens” (Villarreal Martínez, 2009, p. 32). This participation connects citizens and the political institutions in defining collective goals and how to achieve them directly. Again, as in social and community participation, the difference is merely the context and regard we establish related to our object of study. When dealing with political participation, Villareal only considers the formal relationship, whereas in citizens’ participation, there is an emphasis on the co-creation of policies, which also happens in the first case, but mediated by formal means. This definition leaves aside the objectives set by citizens themselves in their actions. Thus, Kasse and Marsh (1979, p. 42, in Delfino and Zubieta, 2010, p. 213) consider that political participation are “those voluntary actions carried out by citizens with the aim of influencing both directly and indirectly the political choices at different levels of the political system,” along the same lines of Verba et al. (1972, p. 2). Regarding Villarreal Martínez (2009, p. 32) definition of citizen participation, Merino (1996, in Guillén et al., 2009, p. 180) specifies that “citizen participation means intervening in the centers of government of a collectivity, participating in its decisions in collective life, in the administration of its resources, in the way its costs and benefits are distributed.” In this way, the citizen who participates is a co-decision maker in the areas that affect him and are closest to him.

Based on this elaboration by the previous authors, we can define a series of dimensions of participation:

(1) Active and passive forms. Passive forms are those in which the individual chooses among a series of options proposed to them, while active forms are the actions to define the problem and its solutions.

(2) Active and reactive participation. Active participation proposes alternatives to the social or political problem, while reactive participation is a response (generally in the form of a complaint or rejection) to policies, without proposing alternatives.

(3) Formal, informal, and non-formal participation. Formal participation is the one that takes place within institutional channels through formal organizations, while non-formal participation is that which takes place within those channels but outside formal organizations. Informal participation does not have a specific degree of formalization, so their organizational dimension is spontaneous. Although participants share a common objective, they are not organized in a specific way.

Beyond those categories, we can differentiate between social and political participation. Social participation is characterized by the intervention in the community, whereas political participation is characterized by the intention of influencing either polities (structures), policies (results), or politics (authors and processes). Both can be undertaken actively and passively, through formal, non-formal, and informal means. Citizens’ participation stands out as a form of political participation in which the citizens are asked by public authorities to become co-creators of legislation and policies, either formally or non-formally.

2.2 Young people’s participation and deliberative democracy

Access to social participation takes place in a social context. In this sense, the existence of participation resources is important, but they must also be linked to the contexts and social networks to which people belong. In this structure, gender, social class, social networks, and length of residence in the neighborhood play an important role. It is not only necessary to take into account the areas where participation can take place (existing resources), but also that these are close contexts for the socialization of people. Thus, there are structures of opportunities that show the different probabilities of access to goods, services, or the realization of activities through various means of participation.

Certain groups in political, social, and economic life suffer some obstacles to participation. Indeed, we know that participatory processes have always had a certain bias (Navarro Yáñez, 2000). Those problems might be related to economic capacity: participating takes time and requires certain economic independence. Other problems are related to cultural capital: individuals need to have the personal tools and skills to engage in participatory processes that are not always simple in nature and are usually associated with age, either with the too young and too old. Some other problems are related to what can be called the emergence of a “coalition of the convinced,” that is to say, a self-selection bias in which only people who are convinced of the positive nature of the participatory process take part in them as a way to support them. However, that is not the only problem derived from self-selection biases: some participatory mechanisms can be used with political intentions to legitimate certain policies, whereas some others might gather only people who are against a particular policy promoted by the local authorities, thus biasing the results of both cases.

The first clear depiction of those problems in participatory processes and bias can be traced to Arnstein (1969, p. 217) representation of the ladder of participation. In her model, we observe various degrees in which we could see how much power is given to citizens and stakeholders through participation. Arnstein (1969, p. 217) distinguishes these eight steps: 1. Manipulation; 2. Therapy; 3. Informing; 4. Consultation; 5. Placation; 6. Partnership; 7. Delegated power; 8. Citizens’ Control. In the first two steps, citizens’ participation is non-existent, and it is basically directed. In steps three to five, participants are informed, consulted, or given minor concessions. In the last three steps, participants co-decide to different degrees with policymakers.

Young people, especially children, present a particular challenge to measure and promote their participation (Weiss, 2020). In some cases, when they are minors, they do not have the legal age to enjoy political rights and are therefore less likely to be considered by policymakers. This encompasses haughty attitudes toward young people, as well as condescending ones. Even when they are young adults, their lower tendency to participate through formal and non-formal channels, as well as their high abstention ratios, makes them a less attractive public to politicians. To explain the degree of involvement of children in their community and the way in which they were treated, Hart (1993, 2008) adapted Arnstein’s ladder of participation and developed a ladder with several levels, representing the degree to which young participants are taken into account in the decision-making process.

This model proposed by Hart can also be translated into young adults, who, even though they have the right to vote, find themselves more into this second type of ladder rather than the one thought for regular participation. In this second ladder, their participation tends to be manipulated, showing higher levels of tokenism and placation. This fact increases their difficulties in taking part in the participatory process, even the ones addressed to them. Thus, we can see that, in addition to the absence of the tools or skills to participate, young people have to face the disregard made by older people, who tend to treat their demands with disdain.

Participatory processes are especially suited to deal with these anticipated problems. There are three main participatory processes, depending on the aim of the participation. There can be participation mechanisms addressed to diagnosis and agenda setting, policy formulation and decision-making, and management (Font et al., 2000, p. 121). This classification departs from the public policy cycle perspective and where these mechanisms lie within such a cycle.

On the other hand, we can classify participatory processes depending on the role we want the citizens to play. Thus, public officials might want to either inform the community, gather the opinion of the community, gather the opinion of stakeholders, articulate the opinion of the community, strengthen the bonds of the community, reinforce the associative sector, seek the participation of the unorganized citizen, reinforce the role of co-decision of the community, and encourage a shift toward a more participatory culture. In that regard, all these objectives can be summarized into three basic functions: retrieve information, promote a debate and a negotiated solution, or make a decision. Therefore, participatory tools can be divided into consultation, deliberation, and decision-making mechanisms (from Font, 2004).

Consultation mechanisms establish a formalized mechanism for interlocution and dialogue with the representatives of more or less recognizable groups or communities. On occasions, their consultation is mandatory within the process of elaborating the laws. This communication process tends to be unidirectional regarding a municipal proposal or action.

Deliberative democracy mechanisms place emphasis on the capacity for reflection and dialogue of ordinary citizens, making them participants in the process of reflection that leads to decision-making (Elster, 1998). It is a two-way exchange between citizens and the public administration, on the idea that it might foster not only trust in the public administration but also improve the quality of policies. They seek to reach a conclusion that brings the initial positions closer together and therefore promotes better policies by involving the recipients of the policies. Deliberative instruments encourage civic culture and social capital and increase the legitimacy of the discursive frameworks that underpin democratic processes. Indeed, they develop tolerance and empathy by integrating different points of view (Güemes and Resina, 2018, p. 74).

Direct democracy mechanisms seek to make it possible for any member of the community to participate directly in the decision-making process. In this mechanism, citizens intervene in the final decision-making process, although on occasions they are allowed to participate in the proposal process (Font, 2004, p. 35–36). Therefore, by making emphasis on the decision, direct democracy mechanisms move away from deliberative tools, in which emphasis is put on the process itself.

From all those types, deliberative tools are the ones that adapt especially well to both young people and the regard older people tend to display toward them. Consultation processes, although suitable for policymakers, usually lack any participatory mechanism, which makes them less attractive to young people, who alienate from them. Decision-making processes, on the other hand, tend to reduce the power of local authorities in the final outcome, which makes them suspicious about the process. Indeed, young people seem suspicious as well about the true final nature of these decisions. Therefore, deliberative processes seem to strike a right balance between these two extremes. On the one hand, they can be used to inform, as well as serve as a source of information. On the other hand, citizen deliberation helps to bring forward possible solutions that were out of the scope of policymakers.

As pointed out by authors, such as Benedicto and Morán (2015), studies on youth participation should take into account factors such as the weakness of youth citizenship, their civic powerlessness, and social frustration to explain certain socio-political marginalization of young people. Thus, these structural factors can explain the marginalization of young people in political participation and the scarce socio-political integration of youth. Factors, such as the loss of considerable demographic weight, mean that they do not belong to a priority group for social policies, thus increasing the obstacles to achieving economic and residential emancipation. In addition, there are growing difficulties in accessing the labor market with social frustration resulting from the blockage of their expectations for personal and professional fulfillment.

On the other hand, there is an emerging type of political activism that is very different from the parameters of traditional militant commitment. In this model, the purpose is to reduce intermediation structures to a minimum, building virtual spaces of connectivity and experiments with new hybrid forms of commitment and participation (Subirats, 2015). A type of civic participation based on a collaborative logic is becoming increasingly relevant among the new generations, which is embodied in very diverse practices with online tools (Márquez Muñoz, 2024) through which people seek to influence public space, thus reformulating the political meaning of their participation. According to Parés (2014), the diversity of the forms of youth participation with respect to adults does not have to do with an apathy toward social or political issues, but rather a disaffection with institutions and the party system.

3 Context of youth participation in Sierra Norte

3.1 Electoral participation

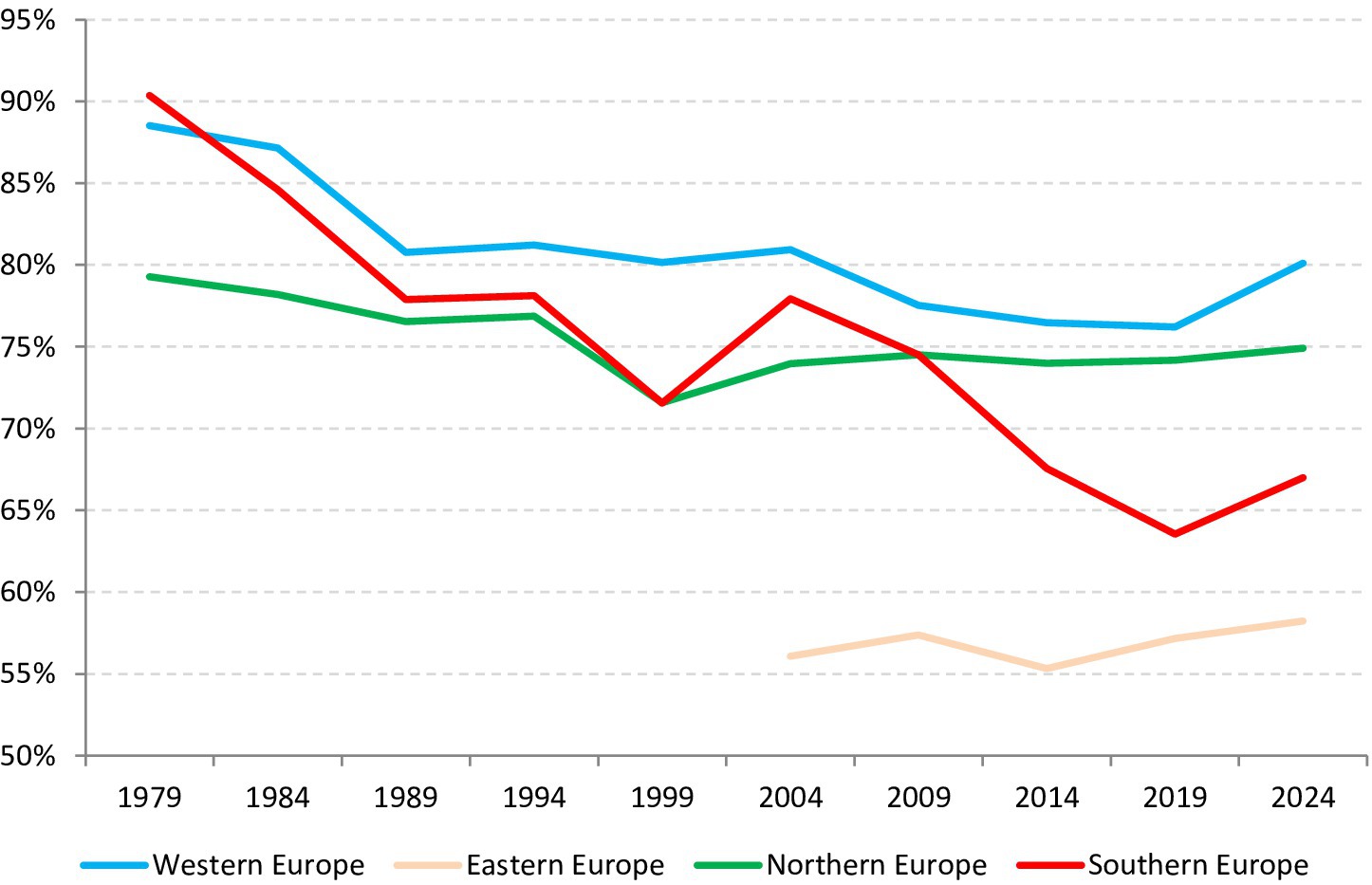

The issue of electoral participation has been one of the central elements in analyses of citizen participation. As Blondel et al. (1998, p. 2) point out, concerns about democracy and the legitimacy of the European Union have been raised on numerous occasions, given that electoral participation has always been low and declining. To analyze this issue and assess the overall trend, it is useful to conduct both a longitudinal and comparative analysis of national elections in the respective European states, dividing them by region to assess the different impacts that have occurred over the last 45 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Average electoral turnout in national elections in EU countries (1979–2024). Source: own elaboration from IDEA (2024) data.

When we look at the data for general elections, we see a constant downward trend in voter turnout over time. Thus, we observe that, in general, in Europe, electoral participation is declining and follows the same trend regardless of the type of election. By regions, Western Europe leads the rest of the regions in voter turnout, with a very slight difference compared to Northern Europe. On the other hand, Southern Europe has seen a progressive decline in turnout, while Eastern Europe has seen a gradual, albeit slight, upward trend. Spain follows that general trend of constant but slow decline in electoral participation.

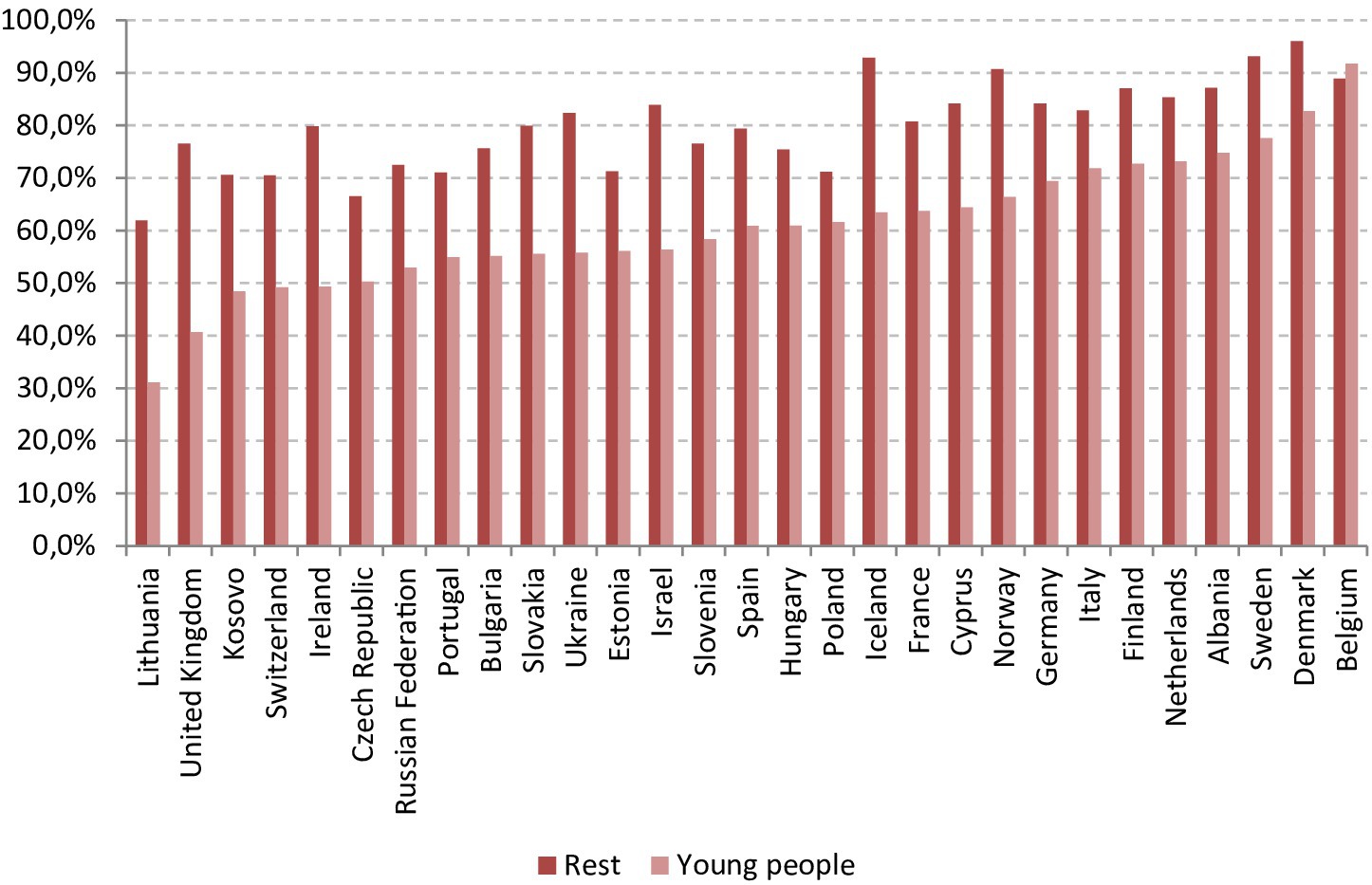

Regarding the specific electoral participation of young people, the only data we can retrieve is through survey data. In the following figure, we show the results for the European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure (2023), which offers a wide range of countries to compare with. In this survey, respondents were asked if they had voted in the previous election, having the right to do so. We show the results by country, comparing young people (lighter color) with older people (darker color) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Electoral turnout by young people in EU countries (2014). Source: own elaboration from European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure (2023) data.

We can see that young Spanish people are placed in the middle of European countries. A total of 60.8% of them voted in the last elections, compared to the 79.4% declared by older people. They ranked 15th of the 30 countries in the sample. There is a 20-point gap between young people and the rest, which is important, although it is not the biggest, being that one in Lithuania and the United Kingdom.

That survey also presented the opportunity for other indicators of political participation. The Spanish youngster performed quite differently. Regarding the option of having contacted a politician or government official in the last 12 months, Spanish youngsters ranked 8th. When asked if they had worked in another organization or association in the last 12 months, they ranked 10th. Regarding signing a petition over the last 12 months, Spanish young people are in the 6th position. When asked if they worked in a political party or action group over the last 12 months, they ranked 4th. Finally, regarding having taken part in lawful public demonstration in the last 12 months, Spanish young people ranked 1st.

Thus, we can see that young Spanish population is less into passive modes of participation, such as elections, whereas they are more involved in active and collective ones, especially in protest movements. Indeed, electoral participation is declining, not only in Southern Europe but all over the European Union. However, this process of electoral decline is in sharp contrast with the motivation of young people to engage actively and participate in certain protest movements.

3.2 Young people’s perception of their role in society

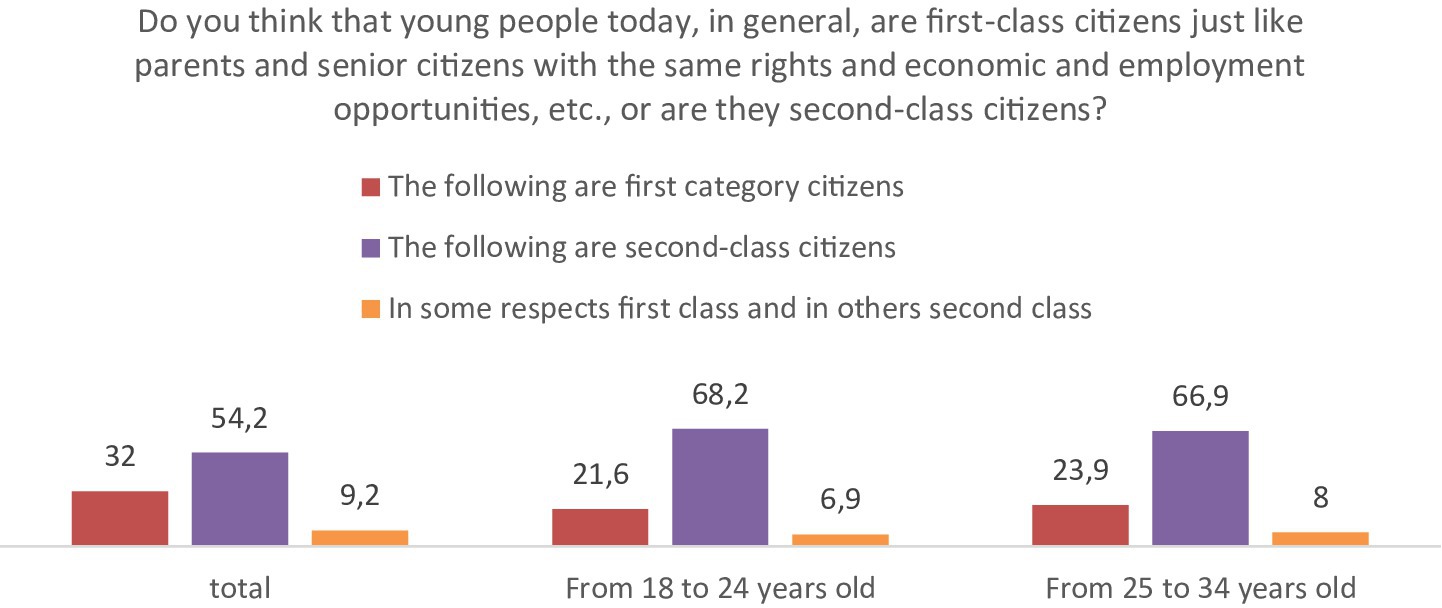

The crisis caused by the pandemic has deepened the self-awareness of powerlessness among the general population. This is even more noticeable when looking at the expectations of young people. In the following figure, we show the perception of opportunities for young people in a national study (CIS, 2021). We present data for the whole population as well as for people aged 18–24 and 25–34 years (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Perception of opportunities for young people, by age group (in percentages). Source: Estudio 3,329| Infancia y juventud ante la pandemia de la COVID-19 (CIS, 2021).

According to CIS studies (CIS, 2021), more than half of the population interviewed is of the opinion that young people are second-class citizens, with fewer rights and opportunities. However, this perception increases among young people under 35 years of age. The younger the respondent, the more critical their view is regarding this issue.

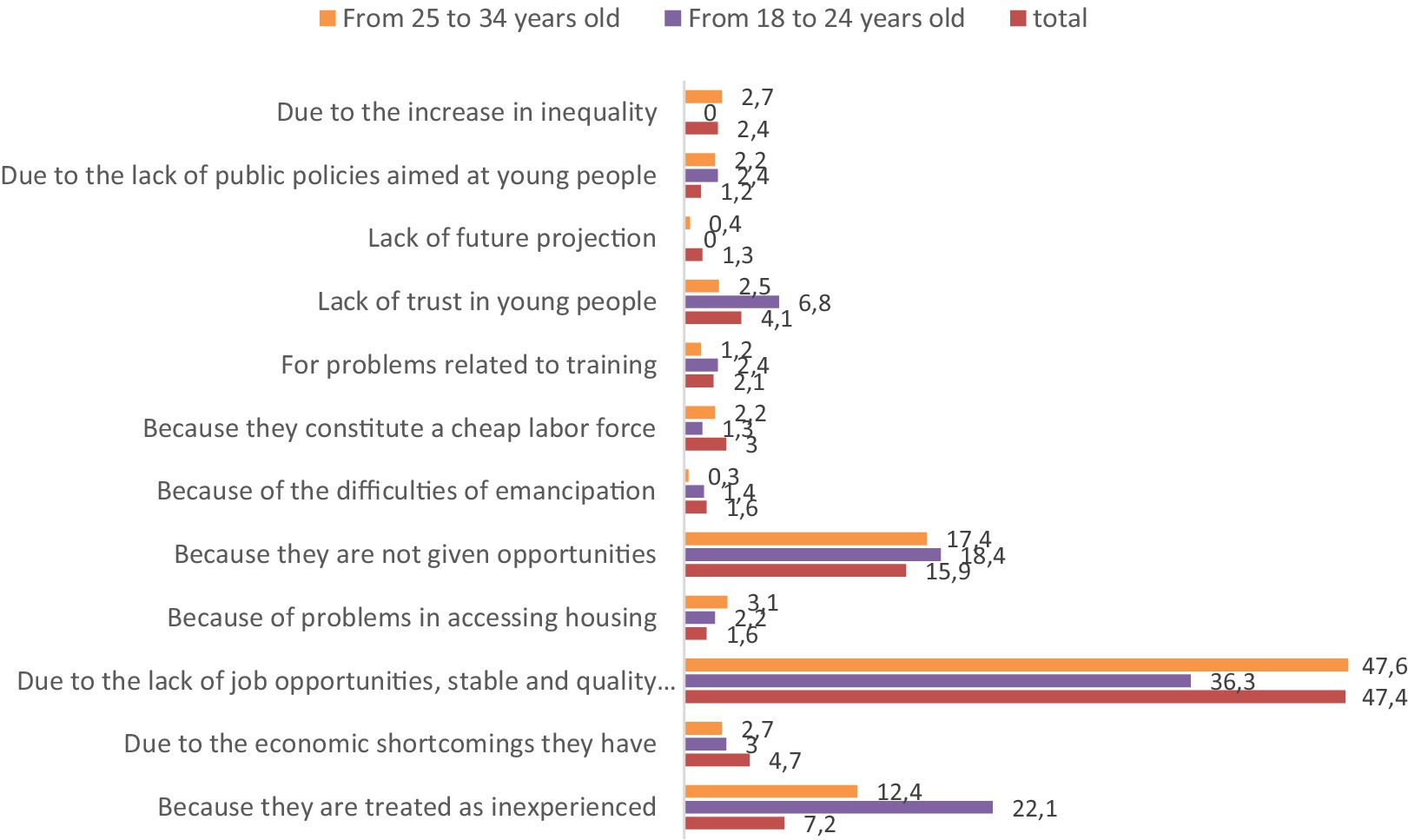

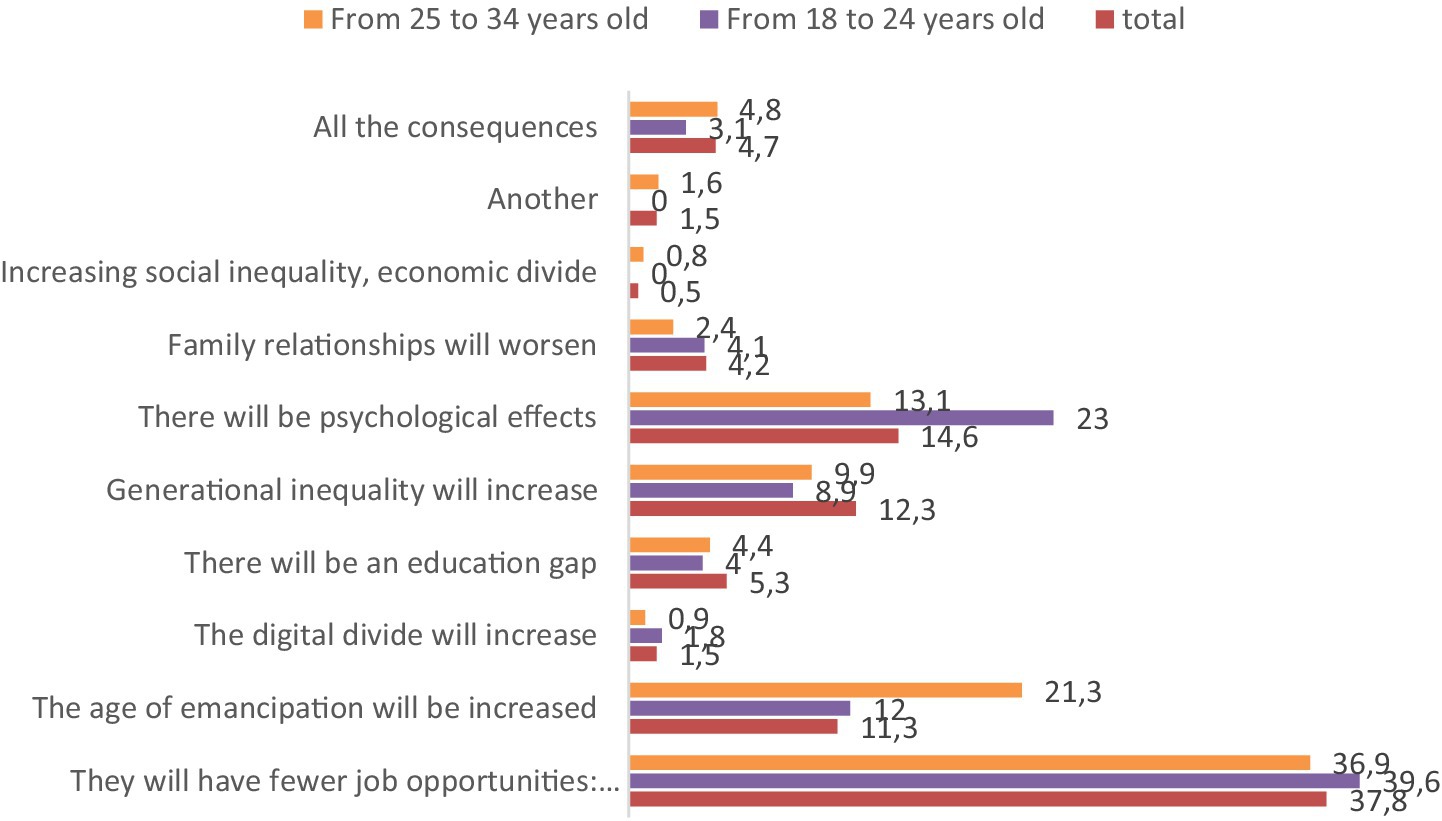

In the following figure, we present the reasons given for such a perception. Again, we present data divided by group age for every category. The factors that make the younger social group, between 18 and 24 years of age, to perceive young people as second-class citizens are very much driven by their lack of access to the labor market (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Reasons for fewer opportunities and rights, by age group (in percentages). Source: Estudio 3,329| Infancia y juventud ante la pandemia de la COVID-19 (CIS, 2021).

Most respondents state that young people in Spain are not given opportunities, are treated as inexperienced, and have little confidence in them. Differences are not remarkable in most items, except for one: the youngest respondents have the perception that they are treated as inexperienced, doubling and even tripling other age groups. Thus, the consequences of the post-pandemic crisis among young people are remarkable, as that age group is particularly marked. In the following figure, we will see other consequences of the pandemic among young people (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Main consequences of the pandemic among young people by age group (in percentages). Source: Estudio 3,329| Infancia y juventud ante la pandemia de la COVID-19 (CIS, 2021).

The general population perceives that there is no remarkable difference among age groups, according to the CIS (2021), with a worsening of the situation among young people. In addition to greater exclusion from the labor market and from housing, younger people highlight the psychological effects as one of the most important consequences; 23% of young people aged 18–24 years consider mental health problems among young people to be the main consequence of the pandemic. In fact, 21.4% of people in this age group report that they are currently experiencing increased stress or pandemic fatigue 1 year after confinement due to health or financial problems at home.

3.3 Young people in Sierra Norte

The municipalities that took part in the project were all from the north of the region of Madrid. All of them had in common that they were very small rural areas. The population density in the Sierra Norte territory is the lowest in the region of Madrid. More than half of the municipalities in the Sierra Norte have less than 13 inhabitants per square kilometer, according to the Registry of Local Entities of the Ministry of Territorial Policy and Public Function.

This situation is especially severe in the case of youth. In 2021, according to the National Institute of Statistics (INE, 2021) data, there were 4,562 young people between the ages of 15 and 29 years in the 42 municipalities that make up the Sierra Norte. This means that 14% of the inhabitants of the Sierra Norte are adolescents and young people between the ages of 15 and 29 years. However, the subregions of Sierra de La Cabrera and Valle del Jarama are the ones with the largest young population, almost 7 out of 10 young people from the Sierra Norte live there; 41% of young people aged 15–29 years in the Sierra Norte live in the Sierra de La Cabrera and 28% in the Jarama Valley. This means that the young population is concentrated and thus it is scarce in many areas. Hereby, we present the number of eligible young participants in raw numbers by municipality (Table 1).

As can be seen in the previous table, the eligible population was very low. Most young people in these areas live in three villages, which concentrate most of the young population. Indeed, it is quite common that, even though some young people live in one municipality, they receive most of the services in another nearby municipality.

The current depopulation and emigration of young people in the territory is clear, so that in the municipalities classified as having a critical situation, the future viability of remaining as an independent municipality is in doubt. Although there are municipalities in a less unfavorable situation, demographic problems or those related to services, infrastructures, or employment are evident in all of them.

On the other hand, when the study was conducted, it is important to highlight the uncertainty regarding young people due to the COVID crisis. According to the study on the effect of COVID-19 on public youth policies in the Community of Madrid (CJCM, 2020), in July 2020, of the 42 municipalities that make up the Sierra Norte, only 62% had youth service. Among the main concerns regarding local youth services and resources, professionals in youth work highlighted the development of programs, projects, and actions for young people in 71.9% of the interviewed, and the analysis of youth reality and strategic planning in 70.1%. In the same study, professionals in the field of youth consider it essential to make proposals to strengthen youth participation in youth policies.

4 Methodological framework

This study takes the approach of a Participatory Action Research that aimed to achieve a critical analysis of reality and, in turn, encourage the participation of the sectors involved so that they are drivers of change. First, we present our research design. Second, we describe the methodology of both the Citizens’ Convention and the Citizens’ Jury. Third, we explain the selection of our units of study.

4.1 Research design

We conducted two studies using a similar methodology: Citizens’ Convention “Generating alternatives for the Sierra Norte”1 and “Citizens’ Jury: young verdict on the situation in the Sierra Norte de Madrid.”2 In both studies, our research question was the same: to what extent deliberative democratic mechanisms, such as Citizens’ Convention and Citizens’ Juries, can be used to effectively foster youth political participation? Thus, both projects aimed to shed light on the new forms of young people’s participation, their level of involvement, and needs after the COVID-19 crisis in the new post-pandemic reality, so that they can tackle the particular needs of young people living in Sierra Norte. The goal was to be able to face the participation deficit and the generational shift in Sierra Norte. Participants reflected on those topics and planned solutions and ideas to encourage young people’s participation in organizations and municipalities, so that they could adopt policies to address the challenges detected.

The project was conceived as Participatory Action Research, utilizing the methodology of a Citizens’ Jury (JC). A Citizens’ Jury is a participatory action and a research technique in which a group of people is invited to give a verdict on a series of questions posed to them after having been adequately informed by experts on the different angles of the problem. Thus, we created a series of deliberation spaces as well as a forum. It was a meeting space with young people, decision-makers of the municipalities, and experts to debate about the demands of the young people and the possible alternatives to address their problems and priorities they detected in the municipalities of Sierra Norte.

The Citizens’ Jury allowed us to assess the opinions of citizens on a specific problem. It is a mechanism of participation that seeks, based on the collective deliberation of a group of subjects randomly selected from among the members of the community, to help institutional representatives in making certain strategic decisions for the municipalities’ planning. Within the logic of diagnosis in participatory research, Citizens’ Juries help improve the traditional process of decision-making and prioritization of public or institutional policies through deliberation and report writing. Furthermore, the Citizens’ Jury provides community members with the opportunity to deliberate together among a group of peers and reflect on possible solutions to an issue of community interest.

Our Citizens’ Jury consisted of a sharing of the results of the prospective phase with experts who described experiences in the field. To this end, clear and simple information on the subject was provided before asking the young people for their opinions. During the jury, we allocated time and space for them to deliberate and reflect on this information before making a decision.

4.2 Methodology of the deliberative experiences

The experiences that we present here are both examples of deliberative participation mechanisms. However, each one of them had its own particularities that we will present here. The comparison will serve us in the discussion to check the pros and cons of each intake. First, we will present the Citizen’s Convention Project, which actually took place before the Citizens’ Jury, although both of them took part after COVID-19 crisis, so that this factor remained constant. Second, we will describe the methodology carried out in the Citizens’ Jury, which benefited from the former to improve it.

4.2.1 Citizen’s convention project

The project consisted of three interconnected events taking place in different cities of Sierra Norte. The first event took place in Villavieja del Lozoya. The topic to be discussed was “The European Union and social and youth policies in the Sierra Norte,” in which young people and policymakers debated what we could learn from European policies to revitalize Sierra Norte and its youth policies. The second event took place in Mangirón and was the central event. The Citizen’s Convention was a meeting place for 32 young people from Sierra Norte for 3 days, from 28th to 30th June 2021. In this participatory process, young people, after having been previously informed about the previous event, debated and generated proposals for the Sierra Norte to improve the youth policies of their municipalities. The debate was carried out with experts and political decision-makers to assess and reach a consensus on the proposals and their viability. The sessions were not recorded to allow spontaneity, but all the conclusions were written by the participants themselves. The event also included leisure spaces and moments to share and get to know each other. Finally, in September, participants of the Convention debated with the general public and passed the conclusions of the meetings on to municipal leaders to enrich the policies of their municipalities.

The main event was structured into four sections. The first day was devoted to knowing about the activity, setting up the expectations, and making the group feel connected. The second day was divided into two sections. During the morning, we had the informative part of the Convention, where participants got to learn about the challenges being faced by young people in Sierra Norte. In this section, they had the chance to interact with experts to make up their minds. In the third section (second day in the evening) of the meeting, participants worked on detecting the problems they considered the most important for them and created proposals. In the final section (the third day), participants presented their ideas to policymakers and debated with them. Policymakers also took the chance to present their ideas of future policies to check what their impressions were on them.

During the whole event, a group of experts facilitated the process. The main point of the facilitation was to encourage attendees to take an active role in the subsequent debates, helping them be ready to deal with experts and policymakers so that young people’s views are taken into account. We started the event with a presentation that was accompanied by several games. These games served as an energizer for young people and helped to raise the issues we wanted them to debate in a playful way.

Once we had settled working dynamics, we divided the attendees into smaller working groups, so that they could articulate their opinions, and the groups were more inclusive. The aim of this was to create a space for young people to meet and engage in horizontal dialogue to launch the subsequent debates. In these debates, the facilitators were part of each group as moderators, trying to ensure that the young people themselves were the protagonists. Thus, we had rapporteurs for each group so that everyone could take part.

At the end of the discussion between young people, we brought the debate together in a plenary session. In this part of the consultation, the rapporteurs were given the floor to explain what each group discussed and what issues arose. Once the presentation was over and the policymakers could watch it, any attendee who wished was given the floor so that each one could relate what we can do for the future of Sierra Norte and what we can contribute to this construction process from our municipalities.

4.2.2 Citizens’ Jury

This second project was much more complex than the previous one. To carry it out, the project was developed through successive phases, some of which required some overlapping in their development. We developed an initial phase, an implementation phase, and an evaluation phase. Each of these phases is described in detail below.

4.2.2.1 Initial phase

Step 1. Initial analysis phase. Within this phase, we proceeded to an analysis of secondary data of the municipality on the youth population. That lets us know the overall composition of young people in Sierra Norte and has a general framework to produce a set of profiles desirable for our juries. We then proceeded to a mapping of organizations and resources for young people in the municipality, and have also made a preliminary analysis of needs and problems.

Step 2. Contact with agents in the area for networking.

Step 3. Meeting to present the program, attended by agents from the area, to define the topics and focus of the study. At this meeting, the methodology of the Citizens’ Jury was presented, and the driving group was organized. Similarly, the three topics to be addressed were decided: leisure and free time; citizen participation; and problems associated with depopulation (employment, housing, education, and health).

Step 4. Design of the target profiles of the Citizens’ Juries and the issues to be addressed in them, seeking to ensure that there is a real possibility of influencing the design of policies in the selected areas. It was decided that each Citizens’ Jury was to be composed by 12 people, and we tried to ensure a gender balance, with representation of young people in working age as well as those studying.

4.2.2.2 Implementation phase

Step 1. Organization of the Citizens’ Juries. Three meetings were organized in Mangirón, Rascafría, and Buitrago, with a different Citizens’ jury in each of them. The first meeting dealt with the topic of leisure and free time. The second jury dealt with the topic of citizen participation. The third jury dealt with problems associated with depopulation (employment, housing, education, and health). In this way, it has been possible to work in small groups, which has facilitated the deliberation to be more agile and fruitful. The following activities have been developed for each of the meetings.

Step 2. Logistical organization for the execution of the project by searching for locations in the Sierra Norte and contacting the young people of the driving group who were involved in the project.

Step 3. Contact with entities and experts who participated in the meetings as experts.

Step 4. Development of the Citizens’ Jury itself. Participants attended the event, where they received detailed information from experts on a topic under study and deliberated to develop proposals to answer a set of three questions. The meetings were structured in the following format:

- Presentation of the Citizens’ Jury methodology.

- Presentation of the representatives of the different participating municipalities and the youth policies they have been developing.

- Presentation of the current state of young people in the Sierra Norte by experts, social agents, political decision makers, and other young people.

- Citizens’ Jury discussion on the current state of young people in Sierra Norte and the challenges they face.

- Proposal of possible policies to combat the problems detected.

- Citizens’ Jury discussion on the priority of possible proposals.

- Drafting of the Citizens’ Jury set of proposals to establish new bases for a youth policy in the Sierra Norte.

Step 5. Citizens’ Forum. This meeting brought together members of the three Citizens’ Juries to present their conclusions on the issues they had dealt with to political representatives and other young people. In this forum, the proposals put forward were discussed with representatives from the city councils, and the best ways for their implementation were discussed. This forum explored the use of participatory techniques over time in future stable projects, which will be maintained by the participating municipalities.

4.2.2.3 Evaluation phase

In this phase, we evaluated the functioning of the participatory technique and looked for possible ways to further implement it. The objective was to see the feasibility of creating a stable tool to inform youth policies in Sierra Norte. In this sense, contacts were made with the Local Action Group of the Sierra Norte de Madrid to see how the conclusions of the juries could feed into the setting of objectives in the next cycle after the local elections. In addition, for their part, the young people involved in the project had been in constant contact with each other and with their respective town councils to establish permanent working links on the youth policies of their municipality. In this sense, several initiatives have been launched for the creation of associations in the municipalities of the Sierra Norte, so that the municipalities have a set of interlocutors to facilitate the development of such policies.

4.3 Selection of the units of study

To carry out this study, we have two sampling layers and two time frameworks. On the one hand, we have a set of municipalities that took part in the project, all belonging to Sierra Norte, a territory in the north of the region of Madrid. On the other hand, we have a series of participants selected both for our Citizens’ Juries and our Deliberative Forum. Regarding the time framework, we present it after the two samples.

4.3.1 Sample of municipalities

To select the towns that were going to be part of the project, we did not produce a sample. We relied on the will of their elected officials to be part of the deliberative experience. These municipalities are not representative of the region of Madrid as a whole. Indeed, the aim of the study was not to have a representative sample, but to represent the most depopulated areas. This means that in some of the municipalities, the number of young people was even below five. Thus, there is a self-selection bias that cannot be controlled for: municipalities that decided to take part in this project were the ones suffering from low numbers of young people, and thus those willing to be more attractive for them to stay in their towns.

The municipalities that took place in the project were Braojos, Gascones, Horcajo de la Sierra—Aoslos, Horcajuelo de la Sierra, Madarcos, Montejo de la Sierra, Piñuecar-Gandullas, Prádena del Rincón, Puebla de la Sierra, Puentes Viejas, Robregordo, Somosierra, Serna del Monte, and Villavieja del Lozoya. As we had already stated, all of them had in common that they are very small rural areas.

This provided a sample of cases that could be described as a set of deviant cases because municipalities that took place were the smallest ones in Comunidad de Madrid and, from those, particularly those that had a smaller proportion of young people. For the purposes of the study, as we will show in the discussion, this is an interesting issue because in participatory processes, it is quite common that municipalities that are willing to take part in experimental activities is due to being used to participatory processes or solving an issue detected, usually lack of participation itself (Navarro Yáñez, 2000).

4.3.1.1 Participants in Citizens’ Convention

Whereas we had one sample of municipalities, we have had several samples of participants for our two projects, Citizens’ Convention and Citizens’ Jury. Here, we describe both the samples of the Citizens’ Convention and the Citizens’ Jury.

Thirty-two young people from the municipalities of the Sierra Norte, six political representatives, and 10 experts from the participating town halls took part. Of the 32 participants, 14 were male and 18 were female. The age of the participants chosen was skewed toward very young people (under 18), but that was due to the fact that it was difficult to find participants of working age. Thirty of the participants were minors and only two were over 18 years. From the six political representatives, four were mayors and two city counselors. The 10 experts were from the Dirección General de Juventud de la Comunidad de Madrid, the Dirección General de Cooperación con el Estado y la Unión Europea, and the Consejo de la Juventud de la Comunidad de Madrid, as well as four from local organizations and three youth workers.

For the selection of young participants, we counted on youth services, which helped to reach out to young people. In Sierra Norte, there are several programs in place, and those municipal technicians served as the connection with the local population. However, as we will discuss later on, this created a set of expectations, as the usual services they carry out are connected to leisure time, so the initiative was labeled to participants more as a summer camp than a participatory meeting. The people chosen were selected among the different municipalities, so that there were representatives from as many of them as possible, but it was inevitable to have several participants from the same village.

4.3.1.2 Participants in Citizens’ Jury

The Citizens’ Jury had a more structured selection of participants, following closely the methodology that imposes that people selected are a sample that aspires to have some representativeness of the different profiles of the population in terms of variability. Finally, these were the participants:

- Ten decision-makers. The three meetings were attended by political leaders, six mayors, and four counselors of the municipalities of the Sierra Norte involved.

- Twenty-seven experts in each area being worked on (leisure and free time, citizen participation, and depopulation) and in the field of youth. As for the participating entities and experts, in each case, we tried to have younger interlocutors and representatives with a discourse closer to the participants. On the other hand, the representation of women was taken into account, trying to reach, as far as possible, a parity presence.

- Thirty-six young people were selected to be part of the Citizens’ Jury. Participants were aged between 16 and 29 years, according to their socio-demographic profiles (age, gender, and residence). Each Citizens’ Jury was composed of 12 young people. In the composition of the Citizens’ Jury, we have tried to have a representation of the real population with a representation that was close to parity of men and women, students, young workers, and unemployed youth who are not currently studying. From those profiles, we finally gathered 44% of men and 56% of women; 11% were students at high school, whereas 16% of participants were young people beyond the studying age. Finally, most of the participants were concentrated in the age group of 18–25, with a total of 72%.

- Thirty-five young people were invited to discuss the conclusions of the verdict of the Citizens’ Jury. For this purpose, we counted on young people of school age from the IES La Cabrera, which is the educational space through which most of the students of the Sierra Norte go through.

4.3.2 Time framework

Both projects were conducted in post-pandemic times. The Citizens’ Convention was undertaken from May to September 2021. The Citizens’ Juries were completed from January to June 2022. The common post-pandemic framework makes it clear that the main conclusions achieved regarding participation are not biased by the particular sanitary situation.

5 Results

In the present study, we observe the different forms of youth participation through deliberative mechanisms and try to get a better understanding of the areas of participation and structure of opportunities for young people in Sierra Norte.

5.1 Results of the Citizens’ Convention

The citizens’ convention “Generating alternatives for the Sierra Norte” was held in Mangirón from 28 to 30 July and was attended by 32 young people from the municipalities of the Sierra Norte, political and technical representatives of the participating municipalities, as well as various speakers who provided information on the opportunities offered by the EU for young people and the situation of the Sierra Norte. In addition to informative talks and debates between young people, speakers, political decision-makers, and technicians of the territory, several workshops were held and participatory methodologies were applied to identify youth problems in Sierra Norte to generate proposals. These proposals were written in bullet points by the participants, reorganized and uploaded to the website of the Conference of the Future of Europe (CoFUE, 2021), so that they can be widespread.

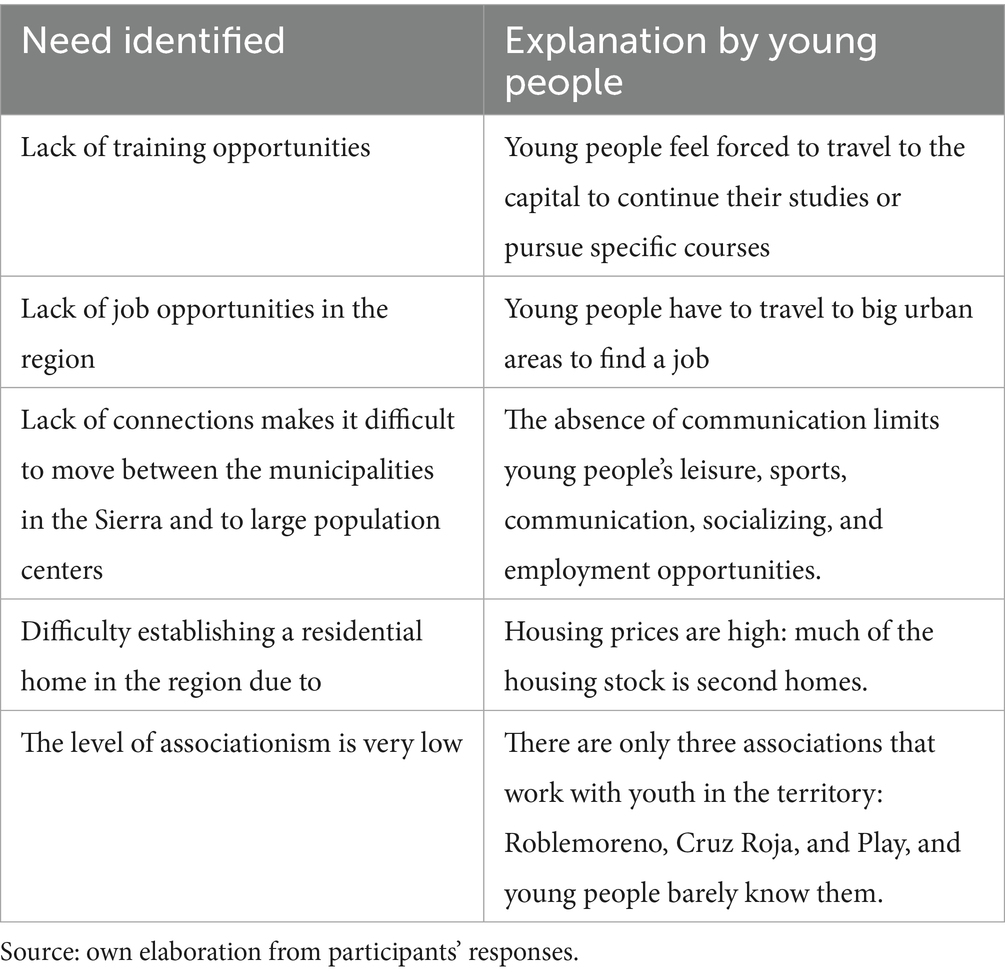

During the Convention, participants made an analysis of the problems detected in the Sierra Norte de Madrid that affect the population and are of particular concern to young people in rural areas. Structurally, basic problems were detected in the territory, such as the lack of territorial policies, lack of appreciation of young people’s interests, lack of political interest, lack of investment in the Sierra Norte, and lack of participatory culture. They were summarized in the following needs identified (Table 2).

These problems are embodied in other issues or symptoms that are perceived as worrisome, such as the lack of environmental education, especially among tourists. Participants perceived a limitation of opportunities due to the lack of communication with other towns. The low number of the young population, very scattered in the territory, induced a lack of integration and low participation as well. There are also some primary needs common to other areas: shortage of businesses leads to a lack of employment. There is also a lack of housing for primary residences due to the use of a large part of the housing stock as second homes.

As a result of the process of deliberation between participants and policymakers, there is a consensus that Sierra Norte lacks a medium- and long-term strategy regarding youth workers. They (usually young people themselves) face significant job instability. Their work is subject to a high degree of temporary employment, as their positions are subject to one-time subsidies that are rarely sustained. This prevents the administrations from developing networks that effectively reach young people. There is also a lack of awareness of the solutions the EU offers to municipalities. The staff in small municipalities lacks knowledge and information about specific programs to target the population or local development.

On the other hand, participants worked to look for solutions or alternatives to some of the specific problems detected. They decided to create five areas of interest: youth and leisure, education and environment, connectivity between towns: transportation, youth employment, and health. The summary of this study is summarized in the following proposals according to the topics chosen by participants.

In the field of youth and leisure they proposed:

• Establish an offer of leisure tailored to young people and consult them to do so. This would address the low youth participation rate.

• Allocate more resources to young people.

• Establish integration dynamics to address the lack of adaptation among young people.

• Hold more talks, activities, and training to raise social awareness.

• Use youth information channels, such as social media with qualified personnel, adapting communication to young people to avoid misinformation among the group.

• Implement more initiatives and projects for young people in the area, listening to their needs; cinemas, concerts, theaters, etc.

• Increased interest from public administrations in the youth community to prevent the exodus of young people from the area.

• The creation of youth leisure centers shared by many municipalities.

In the field of education and environment they proposed:

• Subject about environment in schools, workshops, environmental education talks, and field trips to the countryside and recycling centers to expand environmental education and promote the sustainability of the regions.

• Expand the range of public centers with more modules and university degrees to address the limited training offerings in the region.

• Orientation talks on the different career paths and their opportunities in the region, as well as training paths to prevent the exodus of young people from rural areas.

• Specifically, regarding the environment, the proposal is to promote sustainable tourism in rural areas with measures such as:

○ Establish more recycling points in the countryside

○ Install waste recycling machines that exchange trash for money

○ Provide more environmental education in schools and colleges

○ Create a patrol of young people in the area to receive training, collect waste, and ensure that tourists practice sustainable tourism

○ An environmental campaign.

Regarding connectivity between villages and transportation, they proposed:

• Hiring a person for a period of time to transport anyone who needs it to the nearest bus stop using an 8-seater vehicle.

• Add more busses (more frequent) and change bus schedules to meet the needs of residents.

• Increase connectivity between villages and not just serve the central focus with Madrid to ensure regional development.

In the field of youth employment they proposed:

• Promote youth employment in the villages of the Sierra Norte. To achieve this, the city council should work with the local business community to hire young people part-time.

In the field of health they proposed:

• Provide information about on-call pharmacies and their hours in all the towns in the Sierra de Madrid with informational posters throughout the town, on the internet, and on social media.

Participants proposed concrete measures in the field of youth and leisure and in the field of education and environment. However, the major issue expressed by participants was regarding the connectivity between towns: transportation. This topic alone was the major issue that, in their regard, would solve most of the other issues. Indeed, it was the hottest topic with policymakers, as they thought that their proposal (recently approved, Sierra Car) already resolved all these issues, but participants underlined that the high price and the need to book it 1 day in advance made it impractical for their needs.

5.2 Results of the Citizens’ Jury

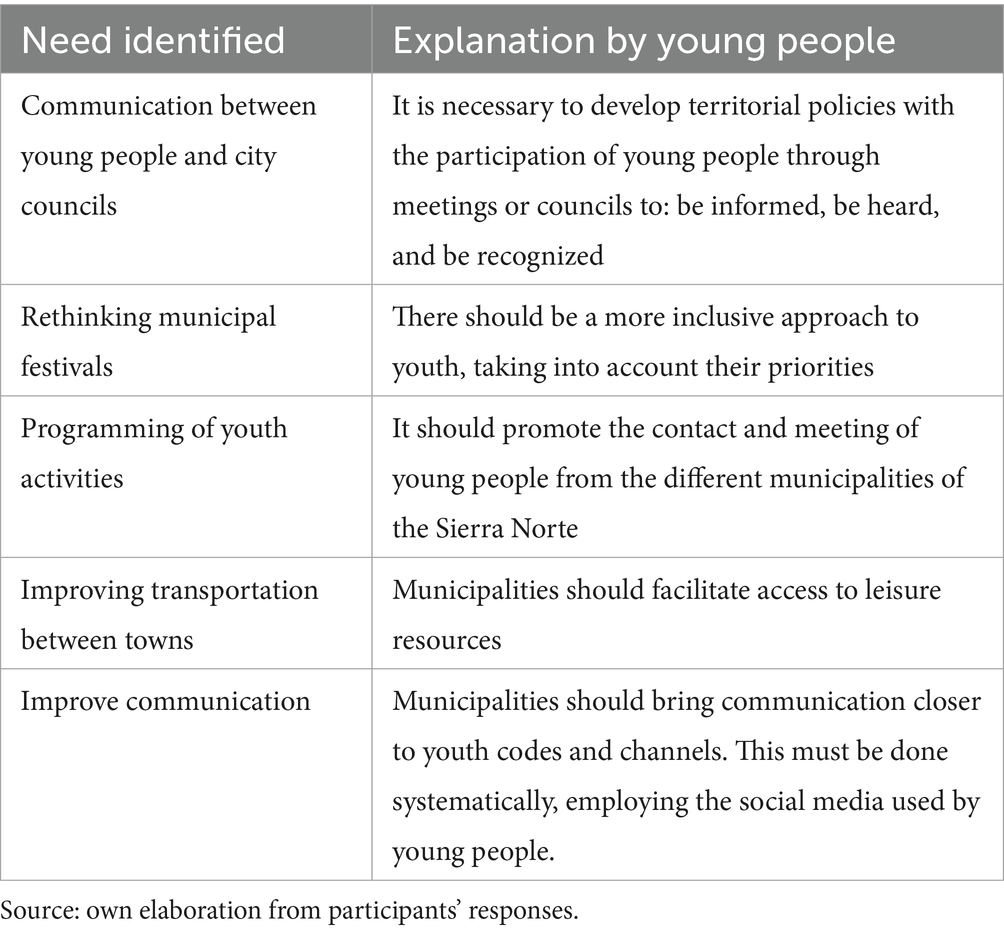

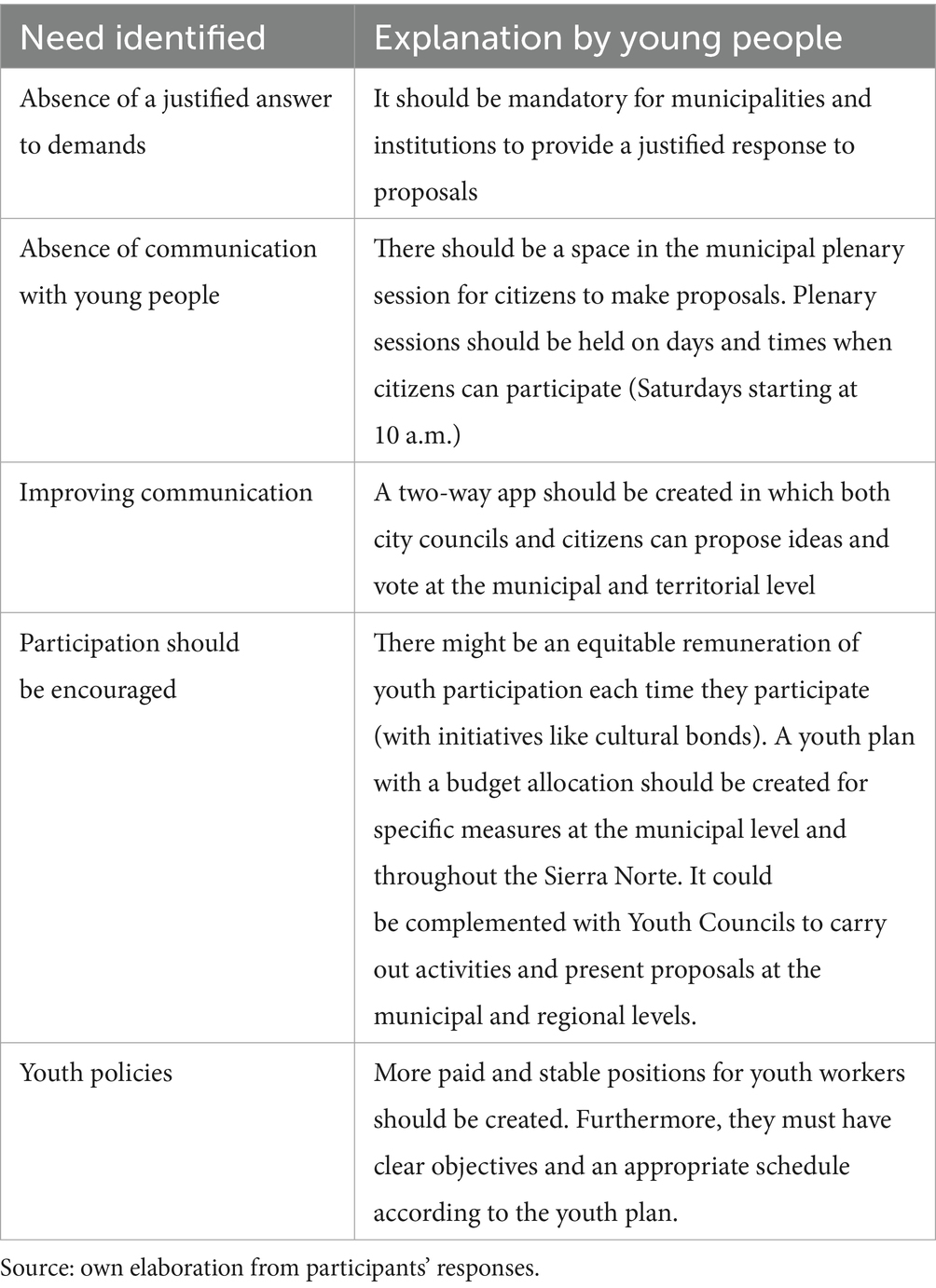

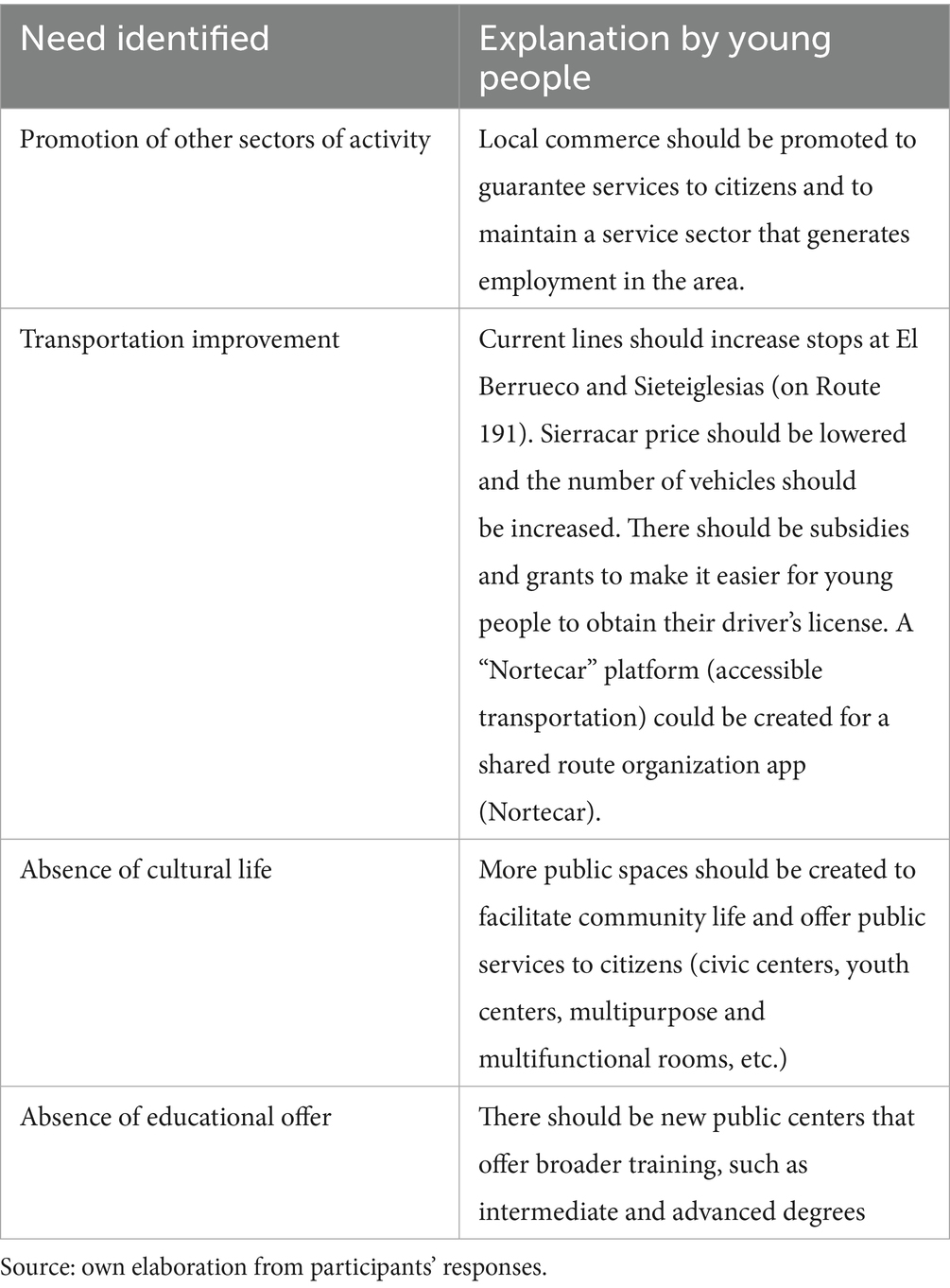

Based on the previous experience, we reframed the Citizens’ Jury so that we could make it more fruitful. In the Citizens Convention, the proposals were vague and it was harder to retrace the real impact of them. In this case, we selected the topics that were more important for participants in the previous experience so that we could concentrate on one topic and have a deeper understanding. The realization of this participatory action research project with the citizen jury methodology aims to still address the issue of rural youth in the Sierra Norte. However, instead of letting participants choose the topics they want to address, we chose the topics. Participants were informed, and they had to deliver a report with the young people’s verdict on the situation, so that participants could make proposals for improvement to policymakers. Therefore, the Citizens’ Jury had the general objective of gathering the opinion of young people on the topics of leisure, promotion of young people’s participation, and depopulation (Tables 3–5).

The main result of the project and possible impact in the medium and long term has been the sensitization toward participation and knowledge about the needs of youth in the Sierra Norte, not only to young people, but also to policymakers. Thus, we can differentiate between two main types of impact, both toward young people and policymakers.

First, the main impact on project participants is a first contact with participation itself and a process of empowerment. Sierra Norte of Madrid is characterized by its population dispersion. In the area of youth, this generates an atomized space, which limits the social relations that can be developed by the young population. Young people are characterized by their fragmentation and, therefore, their inability to make collective demands. The Citizens’ Jury, above all, has helped them to become aware of this reality and of their capacity to influence decision-making processes. The participants have acquired a greater practical knowledge about the possibilities of promoting youth participation in the Sierra Norte. This awareness has even contributed to the self-organization of jury members to create an association that can represent the youth of their municipality.

Participants in the Citizens’ Jury have developed key organizational skills to address the lack of coordination of youth in the Sierra Norte, such as teamwork, communication and social interaction, flexibility, and innovation in problem-solving. This has led to the empowerment of a part of the youth collective in the territory and a greater participation within it.

On the other hand, the project had an impact on policymakers. The information extracted from the study and the methodological process of the Citizens’ Juries itself provided political decision-makers, municipal technicians, and other agents involved with more knowledge about the opinions of young people. The meetings have shown that many of the policies implemented by the municipalities are not known by the young people who are their potential beneficiaries. Thus, some of the group’s demands are already satisfied, but they are not aware of them. On the other hand, some of the services proposed by the municipalities are known, but there is no real demand, their formulation is not adequate, or they are limited to a certain age group, leaving other age groups totally unattended, notably the 15 years −18 yage group.

The project has also served to create channels of communication between citizens and their representatives, so that the participants in the juries have had a greater presence and involvement in municipal and municipality policies. New communication dynamics have been generated with the political representatives, who have had the opportunity to get to know their younger neighbors more closely, and these same young people, who have been able to present their alternatives to their representatives. Thus, through deliberation, the barriers of communication that exist between the two groups have been reduced.

In particular, with this project, we have observed these impacts:

• Greater awareness on the part of some political representatives of the importance of generating spaces for youth participation and debate.

• Greater dissemination of information and tools for youth participation in the region, both to social entities and institutions of the territory.

• Greater visibility of young people, their needs, and proposals for action.

• Greater knowledge of young people of the institutions, the associative network, and the youth resources of the Sierra Norte.

At the regional level, the action developed might be followed to activate citizen participation and meet the needs of young people in rural areas. The project has shown that there is a need for leisure and participation of young people in small municipalities with fewer resources. In this regard, we intend to involve representatives at the regional level in charge of youth policies. In particular, by involving the Youth Council of the Community of Madrid, it might echo the problems of the rural youth of the so-called poor mountains of Madrid, and these problems will be exposed to a wider audience.

Finally, the development of the project has promoted cooperation spaces in the territory between municipalities, as well as networking with the entities of the territory to promote actions and strategies for youth at the territorial level, both in the planning of activities and in political advocacy.

5.3 Comparison between experiences

Although both experiences were similar in nature, the way in which they were implemented was different. They were quite similar in the number of young people involved, but how they were organized was quite different as well. Indeed, the selection process was also conducted differently. The topics we dealt with in each meeting were chosen differently. In the following lines, we will examine those differences in more detail.

First, regarding the number of participants, although both experiences had a similar total number of young people (32–36), they developed different dynamics. The citizens’ convention “Generating alternatives for the Sierra Norte” was attended by 32 young people at once. On the other hand, each of the three Citizens’ Juries was attended by 12 young people each. The smaller number of the Citizens’ Juries helped to empower participants quickly and helped to bring a greater involvement by them. Indeed, the greater number of the Citizens’ Convention brought more dynamics in which participants got distracted from the main goal of the activity, and there was more emphasis on having a good time rather than the deliberative process itself.

Second, regarding the selection of participants, for the Citizens’ Convention, we relied on city halls to do it. We set up some objectives for them with specific profiles, but the information was dispersed as it approached the operational level, resulting in some youth workers advertising it as a sort of summer camp. For the Citizens’ Juries, we created participant profiles again, but we had a more direct control of the information sent to participants, so that false expectations would not be created for participants. This made the participants in the Citizens’ Juries more aligned with the objectives of the deliberative activities, and their actions were much more focused.

Third, regarding the selection of topics, in the Citizens’ Convention, we let the participants set the priorities of the Convention through an identification of problems and then possible solutions. In the Citizens’ Juries, we selected the topics beforehand, and the participants knew specifically what we were going to talk about, and they had a dossier of information they could read as well to prepare for the meeting. The second system proved to be more successful and created fewer expectations as they were told quite clearly that they were to provide a verdict, but it was up to policymakers to make a decision. The first system led to the creation of a set of expectations about the feasibility of their proposals that produced some effects of frustration over time as their proposals were not translated into policies, many of them simply because municipalities do not have the competences to do so.

Thus, overall, we could assess that the Citizens’ Juries as such worked better than the Citizens’ Convention. Even if Citizens’ Juries could be scaled up to several dozen participants, for small communities, the reduced number of participants proved to be better in all terms, particularly in terms of deliberation, as the participants were more prone to debate in smaller numbers and participation was more intense.

6 Discussion

Youth participation in Sierra Norte is very sporadic and scarce. The absence of regional projects for young people and the lack of continuity of programs and technical personnel, added to the geographical dispersion of the young population in the territory and its low demographic weight, have determined, together with other factors, a fragile participation of youth in general. Indeed, the target population is among those who are less prone to get involved in public affairs. In this sense, the expectations raised have been met with the number of young people participating in the meetings. The participation of young people has been achieved thanks to the dissemination efforts of each town council and the direct contact of municipal technicians with the young population of each municipality.

However, at a certain point in the project, our efforts were more directed to find people to take part in it than on the participatory process itself. For the Citizens’ Convention, municipal services proved to create false assumptions about the project and the number of participants, 36 in a 3-day meeting, proved to be a problem rather than an asset. Some participants thought they were going to a summer camp, which forced the team to intervene to redirect participants who were willing to take part. Regarding the Citizens’ Jury, the reduction of participants to 12 makes it more suitable for small areas, favoring concentrating in finding the right profiles for it.

Regarding young people, some profiles are harder to achieve. The older young population (25–29) has been the most complex. Local employment programs in two municipalities have been used to invite them to participate, but with limited success. Once young people leave school age in the area, given that there is no University in any of the municipalities, those profiles, which barely relate to local communities, are very hard to identify. At a certain point, two alternatives were considered: issuing official letters from the city halls and paying for the participation, as would be the case in a real jury. Both were discarded by the local authorities, but problems in reaching out some profiles made us consider that as a more viable alternative than having skewed samples of individuals.

Overall, the fundamental role of young people living in the Sierra Norte has been recognized and fulfilled. Their active participation in the issuance of proposals has been highlighted and taken into account by the authorities and policymakers participating in the project. The participation of political decision-makers, however, has been partial. It has not been possible to count on the active participation of experts and political decision-makers from all the town councils involved in the project in the working sessions during the meetings. Indeed, proposals quickly exceeded the capacities of these small municipalities. In the case of the Citizens’ Convention, although warned repeatedly, some frustration was created among participants. In the Citizens’ Jury, the scope was limited and the participants were asked to answer a specific problem. Involving citizens in problem definition, while ideal, has to be matched with the willingness of city halls to act on those issues. There is a ladder of participation for a reason, and ladders are better used when walked step-by-step.

When dealing with projects of deliberative democracy, it has to be taken into account that policymakers have their own agenda. We observed that many of the policymakers tried to transform participation into symbolic rather than meaningful, along the lines exposed by Arnstein (1969) and Hart (2008). Thus, in that context, as project managers, most of our effort went into educating not only young participants but also policymakers to be aware of the importance of these processes.

The dialogue between young people and policymakers was fruitful. An effective channel of communication has been established between young people and policymakers at local and regional levels. In this regard, our first project led to the creation of an informal association of young people who met at our event and realized they had the same problems. During our Citizens’ Jury, another participant took the lead to create a formal association, although the administrative burden in the process meant that this could not be completed in the time of the development of the project. The most meaningful policy impact of both projects was on the refinement of Sierracar services, a transportation initiative for Sierra Norte. Some changes were made after the deliberative processes, as letting the reservation be done on the same day (not the previous day as it was stated before).

However, those first steps are also very fragile and volatile and depend more on individual initiatives than structural conditions. They had not solidified over time and, thus, the overall impact of the project on policies was minor. It has also to be ascertained that the project was conceived before the COVID-19 pandemic hitting it when it was about to start. That also meant that the end of the project got quite close to local elections and that new officials were elected. The big renovation of local political elites meant that there was no continuity. Even if the project was presented to the new local authorities, there have been no new initiatives to continue with these projects.

Following Dryzek et al. (2019), dialogue has led to a better understanding of the specific needs of young people in rural areas and has facilitated active listening on both sides to work on more appropriate and effective policies to address needs and take advantage of potential. At the very beginning of this dialogue, it was necessary to make policymakers aware that the meeting was not about justifying themselves or indoctrinating participants, but a clear and sincere dialogue. Several sessions would have worked better for that purpose. However, in general, if there is no political will from the local authorities, it is very hard to start those processes when there is not a big push by local communities.

Our projects also worked to stimulate knowledge about local and regional resources and democratic practice. The methodology has been successfully used to increase young people’s knowledge about good practices, agents involved in the territory, knowledge of the closest political and technical decision-makers, and of European programs that land in the territory. The evaluations we conducted showed that participants had a good time and enjoyed taking part in the activity, even if it took place during their free time on a weekend. Young people have highlighted the fact that they have been able to broaden their vision and knowledge of resources in Sierra Norte. The methodology used has also been highly valued by young people and the political and decision-makers involved.

Answering our research question, the Citizens’ Jury, over more massive deliberative forums, such as the Citizens’ Convention, has proven to be a better methodology for including young people in decision-making at the local level. The municipal and regional authorities have recognized its importance and have committed themselves to continuing to involve young people in youth-related issues. In fact, it is feasible that the methodology will be repeated to continue delving into some key issues for territorial development in the field of youth. It has also worked to articulate youth opinion for the development of policies and to make them aware of problems they had not reflected on. Through the project, several documents have been produced that have served as a framework for the development of youth policies in the Sierra Norte. For example, city mayors have changed their approach to Sierracar so that it could be more affordable to young people, and learned that what they thought young people wanted was not as they had planned.

Overall, the methodologies proved to work well and engage young people more than other forms of participation. Indeed, people who participated in those experiences showed more interest in either taking part in associations or joining new participatory events. The smaller groups of the Citizens’ Juries are also a better space for deliberation and engagement between policymakers and participants. The verdict issued by the young people contained concrete solutions to improve the quality of life and wellbeing of young people in the area, promote their participation, and address the challenge of depopulation. Even though verdicts were very specific, their impact on concrete policies cannot be ascertained for sure. Two projects cannot change the full landscape of participation in a very depopulated area characterized by a lack of interest in both policymakers and citizens. Indeed, the most important thing for participatory processes is the political will of policymakers regarding participation. However, once the will is present, among many other options such as participatory budget, deliberative surveys, forums, or alike, the Citizens’ Jury, with a low level of needs in terms of mobilization, could be a perfect tool to lead the first steps of participation in rural environments where there is little experience about them.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the low number of participants make it very easy to be identified. General conclusions on the meetings can be made available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to b3NvdG9AdWNtLmVz.

Author contributions

ÓS-S: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author declares that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was conducted under the Erasmus Plus project 2020-3-ES02-KA347-016590 of the European Union and a grant by Comunidad de Madrid.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the municipality of Robregordo for leading this Erasmus Plus project, as well as the municipalities of Sierra Norte for taking an active part in it. The author wishes to acknowledge the contribution of Iuventia S. Coop. Mad., particularly Eva Gracia and Sandra Soto, for their organization of the logistics of the citizens’ juries and the collaboration in its development of the project and analysis. The author wishes to thank the help of Claudia Ranea in the development of the citizens’ juries and analysis. The author would also like to thank the reviewers for their suggestions and comments.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement