- 1Department of Political Science, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, United States

- 2Department of Political Science, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 3ELTE Centre for Social Sciences, Budapest, Hungary

Debates on the nature and causes of populism persist in the public and among academics. We test two contemporary theories of populism – issue-based and ideational – by exploring their implications for the expression of populist rhetoric among citizens. In a large scale, cross-national experiment (N ~ 18,000), we prompt the expression of populism through an elaboration task exploring the causes and solutions to current policy problems. The task frames the discussion as the product of either responsible actors (populist framing) or impersonal circumstances (non-populist framing). Three findings emerge: (1) different political issues provoke more populism than others; (2) framing policy problems in terms of responsible actors increases the expression of populism across countries and participants; and (3) political issues combine with respondents’ ideology to prompt populism in predictable ways. These findings support the arguments of the ideational approach.

1 Introduction

If populism was largely a European Zeitgeist two decades ago (Mudde, 2004), it is now a Poltergeist disrupting democratic institutions around the globe (Ruth-Lovell et al., 2019). While the size and durability of the current wave of populism is still in doubt (Jenne et al., 2021; Rooduijn et al., 2012), evidence shows that populists can have a significant, negative impact on liberal democratic institutions once they are in power that offsets any improvements to democratic representation and participation (e.g., Pappas, 2019; Kenny, 2020; Rogenhofer and Panievsky, 2020). Determining the nature and causes of the contemporary surge in populist forces is critical.

In this article, we test two (sets) of the most prominent individual-level approaches to explaining the emergence of populist forces: the ideational approach, which sees populism primarily as a common discursive frame that becomes salient under conditions of democratic representational failure (Hawkins et al., 2019; Mudde, 2017; Aslanidis, 2016); and issue-based approaches, which associate populism with clusters of issue positions of the left or right, such as opposition to economic liberalism or the defense of traditional social values (Edwards, 2010; Norris and Inglehart, 2019).

While these two approaches pose different arguments about the nature and causes of populism, both make claims about when politicians and citizens use the “people vs. elite” rhetoric that helps distinguish populist forces from other parties and movements. We take advantage of this overlap by presenting the results of a cross-national, online experiment designed to invoke populist rhetoric among ordinary citizens. The experiment, which replicates an earlier study in the United States, asks respondents to elaborate on the causes and solutions to major policy failures affecting their country. The treatment condition varies from the control in terms of how these failures are framed as the result of knowing actions by powerful actors, thus mimicking features of populist rhetoric; or as the consequence of impersonal events and circumstances, thereby imitating pluralist rhetoric.

The experiment was conducted with over 18,000 English-speaking participants in more than 100 countries, giving us the statistical leverage to parse out the effects of framing and issue positions on how populism is spoken. We find that while populist rhetoric does accompany certain issues more than others, populist framing consistently increases this level of rhetoric across all issues. Furthermore, these increases are predictably associated with certain ideological positions: even when an ideologically diverse array of respondents mention an issue as salient, they employ populist rhetoric only when it is compatible with their host ideology. Overall, the results suggest that issue-centric approaches perform a useful function by helping us identify the historically specific structural changes associated with populist forces, but that the ideational approach better explains why these structural changes provoke citizens and politicians to frame issues in populist terms.

1.1 Different approaches to populism

While the earliest theories of populism’s causes were largely structural, emphasizing aggregate-level, long-term causes rooted in trajectories of economic development and political institutions (Conniff, 1982; di Tella, 1965; Germani, 1978; Weffort, 1978), newer theories tend to be individual-level ones emphasizing the decision making of individual citizens. These individual level accounts are particularly compelling in light of recent studies that citizens, and not just politicians, hold populist attitudes and even use populist rhetoric to think about and discuss politics (Abts et al., 2019; Akkerman et al., 2014; Cramer, 2016; Torre, 2010), and that these attitudes and rhetoric correlate with support for populist parties and movements (Andreadis et al., 2019; Akkerman et al., 2017; van Hauwaert and van Kessel, 2018). Together, these studies make the case for an approach to populism that studies both the supply and demand for populism at individual levels.

Of the various theories currently competing as individual-level explanations of populism, two stand out. On the one hand, issue-based approaches link support for populist forces to the failure of government policy to protect citizens’ particularistic demands. In countries in the Global South in the mid-twentieth century, populism was frequently seen as a cyclical response to long-term patterns of delayed development and economic dependency on the Global North, resulting in poverty and inequality (Cardoso and Faletto, 1979; Vilas, 1992). In wealthy democracies today, issue-based theories argue that these demands arise from long-term economic malaise brought on by globalization (Ferguson, 2016; Rodrik, 2017) or that they represent a cultural backlash to the spread of secular, post-materialist values and non-native cultures (Betz, 1994; Norris and Inglehart, 2019). A few studies affirm that it is the combination of these issue sets, cultural and economic, that motivate populist voting (Gidron and Hall, 2019). Whatever their regional and temporal differences all of these studies make a similar argument about the primacy of voters’ calculations of interest (material or cultural) in shaping their preferences for populist parties and candidates.1

Early studies using issue-based arguments often went as far as defining populism entirely in terms of these issue positions (e.g., Cardoso and Faletto, 1979; Vilas, 1992; Dornbusch and Edwards, 1990). However, the current tendency is for these studies to formally define populism in terms of a “people vs. elite” rhetoric, thus placing them closer to the ideational camp, while limiting their analytical focus to specific ideological flavors of populist parties, such as those of the radical right. Thus, as Hunger and Paxton (2021) note in their review of the European populism literature, populist rhetoric is seen as a necessary condition that allows a party to be labeled as populist, but is not seen as having a significant role in driving support for these types of parties.

The ideational approach defines populism largely in terms of its rhetoric, as an effort to interpret politics as a struggle between the reified will of the common people and an evil, conspiring elite (Hawkins et al., 2019; Mudde, 2017). To be clear, the ideational approach does not see populism as an ideology in the traditional sense, as it neither contains a coherent set of roles and relationships governing state and society, nor a broad policy program. Rather, populism is “ideational” because it is an argument about the fundamental nature of the political community and how its values—democratic values of popular sovereignty—are under threat. Hence, scholars using the ideational approach refer to populism as a “discourse,” “thin-centered ideology,” or a “frame of mind” and place it within a typology of frames that includes pluralism, elitism, and nationalism (Aslanidis, 2016; Cleen and Stavrakakis, 2017; Mudde, 2004). We especially prefer to approach populism in terms of framing theory and refer to it as a discursive frame in the rest of this article.

Ideational scholars argue that we cannot understand support for populist actors merely in terms of particular policy demands, because populist framing is not intrinsically linked to any specific issues or ideological preferences. Across the world, and even within some countries, populism can be attached to ideologies on the left, right, and center, and is used to frame widely different issue stances. The particular vessel for populism varies dramatically across contexts. However, the ideational approach argues that in practice, certain issues become associated with support for populists at certain times and in certain countries because the underlying policy failures are serious and can credibly be viewed as the result of policy choices by elites, and these elites are allied with the beneficiaries of those choices.

So far, a limited amount of research has directly compared and evaluated these sets of approaches to one another. Recently, several studies have used conjoint experiments to evaluate how “thick” – or issue-based, left–right, and partisan content – and “thin” – or ideational content – elements of populism drive electoral support for elected officials and candidates (Dai and Kustov, 2024; Ferrari, 2024; Neuner and Wratil, 2020; Silva et al., 2022). We think these contributions point in the right direction, but at present these comparisons have been made only with electoral support (in the form of vote choice) without considering how citizens speak and reason about politics more broadly. This is especially important given findings in other parts of the populism literature about the impact of populist framing on how individuals discuss politics, interact with political information, feel about political figures, and are mobilized to engage with politics (e.g., Hameleers et al., 2016; Hameleers et al., 2018; Busby et al., 2019a; Hameleers and Fawzi, 2020). This suggests an ongoing need to compare issue-based and ideational approaches to populism in a number of areas to establish the place of these theories in understanding populism in mass publics.

1.2 Issue-based and ideational predictions

In the paragraphs that follow, we outline the predictions of the issue-based and ideational perspectives for expressions of populism in the public. We emphasize expressions of populism because both approaches see these as at least partly definitional, but also because previous work has shown that populist rhetoric has political consequences (e.g., Busby et al., 2019b) and because of its potential for feedback loops in the public. When citizens are prompted to think about issues in populist ways, their expressions of populism can go on to encourage populism in others, possibly leading to cascades of populism. Further, expressions of populism in the public can serve as signals to elites and provide motivations for parties and political figures to adopt a more populist perspective (Scott, 2023; Surdea-Hernea, 2025).

To begin, both the issue and ideational approaches initially have the same prediction about expressions of populism by individuals:

H1: At any given moment, members of the public will express more populism when discussing some issues than others.

For both theories of populism, the issues associated with populism vary by country and historical period. Across most historical periods and regions, economic well-being (especially inequality and the lack of social mobility) has been associated with populism (Betz, 2019; Kazin, 1998; Walicki, 1969). In the contemporary context, and in some earlier periods as well, populism can be linked with concerns over immigration, racism, and the clash over traditional versus secular or postmodern values (Betz, 2017; Cramer, 2016; Hochschild, 2017). In any historical juncture, both issues-based and ideational approaches see populism’s people vs. elite rhetoric being associated with certain issues and political topics. That is, regardless of whether they see these issues as causal, they at least accept them as correlational.

However, the two approaches diverge in their expectations about how easy it is to trigger more populist expression, either around existing issues already associated with populism or new ones not yet made populist. Issue-based approaches spend little time explaining exactly when or how populist ideas come to be associated with particular issue positions; often, these clusters of policy positions are treated as if they were inherently populist. Clearly, these issues reflect some of voters’ deepest concerns and have festered long enough that voters have lost confidence in the traditional parties. Thus, for an issue-based theory of populism, populist trappings are long in forming and resistant to change, at least until the underlying policy issues are resolved.

In contrast, the ideational perspective holds that expressions of populism can readily increase, and that supposedly non-populist issues can become suffused with populist rhetoric if voters are prompted the right way. In the language of framing, voters already possess a number of latent populist considerations that can be made more accessible, applicable, and salient with the correct emphasis or frame (Chong and Druckman, 2007; Klar et al., 2013). Different kinds of rhetoric and messaging can therefore influence expressions of populism by shifting the relative salience of these underlying, more latent beliefs.2 For populism, this often occurs when elites, the media, or the public are given specific kinds of references to in-groups or pushed to place blame for political problems or crises “vertically” on intentional corrupt elite actors and/or “horizontally” on a range of culpable outgroups (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007). By attributing blame to such out-groups, populist messages activate or supply cognitive blame heuristics – causal links in public discourse and citizens’ minds [see discussion in Corbu et al., 2019]. This potential of populist ideas to produce a cognitive framing effect should exist across a range of political issues, not just those associated with particular political perspectives. Further, in line with framing research, the ideational approach does not expect populist framing to shift people’s issue positions; instead, populist appeals shift the way people conceive of those political priorities and how they express their views on those topics.

Thus, issue-based approaches yield the following hypothesis regarding the short-term consequences of populist rhetoric and framing:

H2A: Populist framing will not cause individuals to express more populism.

While the ideational approach implies the following:

H2B: Populist framing will cause individuals to express more populism around policy issues they already view as important.

Beyond these standard predictions of the issue-based and ideational perspectives, the ideational approach has a unique argument that can be used to narrow the universe of political topics that politicians and citizens effectively frame in populist terms. Populist framing is of course not associated with every discussion of certain issues, but with certain issue positions—not with immigration broadly, for example, but with a desire to prevent immigrant competition for blue-collar jobs and to facilitate assimilation into a dominant national identity.

From an issue-based perspective, the relationship of certain issues with populist framing is not well explained or predictable except to the extent that it is assumed to be constant—it is a given, an inherent property of certain issue positions. This is why issue-based theories are perplexed when new populist movements emerge that flip the positions of older movements—for example, why U.S. populists in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries championed government ownership of key industrial sectors in transportation, finance, and communications (Kazin, 1998), while those in the early twenty-first century often opposed it (Lowndes, 2017).

From an ideational point of view, however, these associations are more predictable and can be explained in terms of another ideational factor, namely, one’s host ideology. The ideational approach sees the host ideology – or the larger ideological view populism is linked to - as having a kind of causal primacy that determines what issue positions populism can successfully leverage. This happens not just because the host ideology expresses or even determines where voters already stand on a given issue, but because these ideologies have embedded within them a sense of which groups in society are virtuous and which should be held in suspicion, a belief that correlates with actual partisan allies and opponents. In particular, ideologies of the left draw from classic socialist arguments about conspiracies of economic and religious elites and the virtues of enlightened intellectuals, while ideologies of the right draw from an equally familiar, conservative heritage of arguments about conspiring revolutionaries and secular intellectuals and the noble motives of the traditional elite (Freeden, 1996). Thus, even if opposing sets of ideologues from the left and right feel strongly about the same issue, they may or may not frame their positions in populist terms because of how willing they are to blame responsible groups for failures on those issues.

As an example, leftists concerned about environmental degradation today will be more willing to accept and use populist rhetoric to frame this issue because they already tend to blame corporate and capitalist elites for policy failure. In contrast, rightists who are concerned about the environment should resist the combination of populism and the environment, as their pre-existing ideological views discourage them from demonizing business elites and make them more likely to blame aggregate consumer behavior or misguided government regulation. To take a contrasting contemporary issue, rightists concerned about immigration are comfortable adopting a populist frame because can readily blame intellectuals and interest groups that champion the cause of multiculturalism and immigrant rights, while leftists concerned about immigration prefer to blame impersonal forces of global events, bad institutions, and the bigotry of ordinary citizens for the challenges faced by growing numbers of immigrants, an attribution that is less compatible with populism. This claim is distinct from the proposition that leftist and rightist individuals care about different issues; instead, we hypothesize that populism has no purchase for leftist and rightist politicians who focus on issue positions that are out of sync with their broader ideologies. There are leftists concerned about immigration and rightists worried about the environment, but for these individuals, populist frames fall flat.

We articulate this line of thinking with a general prediction in H3, made testable in its specific versions in H3A and H3B. These hypotheses draw on the typical enemies of left and right ideologies to gain insight into the sources of populism.

H3: The effect of populist framing varies by issue area and by citizens’ ideological orientations.

H3A: Populist framing about nationalistic and cultural issues prompts more populism among those on the right than on the left.

H3B: Populist framing about the environment and redistribution prompts more populism among those on the left than on the right.

Note that the issue-based perspective does not anticipate either H3A or H3B, given that it does not expect any short-term increase in citizens’ populist rhetoric due to other people’s populist framing (see H2A). Thus, we do not propose an alternative hypothesis derived from an issue-based approach.

To test these predictions, we require a context where individuals can express their issue-based concerns. In addition, some of these people must be exposed to populist framing of the issue, while others must not. Further, we must examine a sufficiently high number of individuals such that, for each policy concern, we observe individuals with left, center, and right ideological orientations. This latter point is crucial to examine circumstances where policy concerns are in and out of sync with citizens’ general ideological orientations. As such, we turn to new sources of data rather than drawing on existing studies of populism. In the section that follows, we describe our unique source of data, its benefits, and how we leverage an experimental design with an extremely high-powered sample of respondents (N = 18,984) to evaluate our hypotheses.

2 Method

We test our hypotheses through a preregistered experiment embedded in an online survey launched on 21 November 2018. To conduct the experiment, we collaborated with The Guardian as part of a series of long-format digital articles on populism. Our study comes from one of the early articles in the series, an interactive quiz that measured readers’ populist attitudes and political ideology. At the end of this article, readers were invited to participate in an additional survey that contained our experiment. Those who accepted were taken to a Qualtrics instrument that we designed. After agreeing to participate, participants answered a question about their age to filter out individuals under 18.3 Those who qualified were then randomly assigned to the treatment conditions in the following sections with equal probability and began the substantive portion of the study.

Participants first answered a series of demographic and attitudinal questions, including measures of gender and education, populist attitudes (using the module suggested by Silva et al., 2019), left–right ideology, and interpersonal trust. They then proceeded to our experimental treatment, a manipulation of populist framing.

This treatment was drawn from our previous research (Busby et al., 2019b) and consisted of an elaboration task in which participants answered three questions about a policy problem in their country. After selecting their country from a dropdown list, participants were first asked to identify the problem in their country that worried them most:

“Here is a list of problems that different people mention in different countries. Which one worries you the most for your country?

If the problem that worries you most is missing from the list, please pick “other” and type it in. (If you select other, please limit your response to a few words).”

Participants chose from the following list of problems, presented in randomized order: the (1) decline in our traditional values, (2) the lack of direction in our government, (3) environmental degradation, (4) economic and social inequality, (5) racism and the lack of tolerance, (6) the negative state of our economy, (7) the threat of terrorism, (8) the high cost of health care, (9) the poor quality of education, (10) the increasing number of immigrants, or (11) Other (and asked to explain). This list had been pre-tested and used elsewhere (Busby et al., 2019a; Busby et al., 2019b); we made minor adaptations to fit our international sample.4

From here, respondents were asked to complete one of two versions of the elaboration task based on their treatment assignment. Participants randomly assigned to what we call the “populist” treatment completed the two following open-ended questions about the problem they selected in the prior step. This version focused on identifying specific actors behind the issue that concerned the respondent:

What groups or individuals do you think are most responsible for (problem they selected)? (Please limit your response to a few words).

In at least a few sentences, explain why you think these groups or individuals are responsible and what should be done about them.

Participants randomly assigned to the “control” (non-populist) group were instead asked the following items. These emphasize impersonal forces at work behind political crises and problems and what would address those forces.

What events or circumstances do you think are the main cause of (problem they selected)? (Please limit your response to a few words).

In at least a few sentences, explain why you think these events or circumstances have caused this and what should be done in response.

While both treatments incorporate references to the larger political community and major policy failures—essential components of a populist frame—the populist treatment completed the frame by asking participants to blame specific political actors. We chose to employ these treatments, and label the former as a populist frame, for a number of reasons. First, the populist frame links to one of the key elements of populist rhetoric – the blaming of political problems on specific actors or elites in society – by asking respondents to attribute blame to a specific group or actor. To be clear, populism is more than this kind of blame; it also includes emphasizes failures of government and the people as virtuous and good (Busby et al., 2019b). However, this type of dispositionally-focused blame is required for populism and an element that distinguishes populism from alternative discourses. Pluralist discourse, for example, also values popular sovereignty and ordinary people but avoids attributing blame like populism (Mudde, 2004; Espejo, 2011). As such, this kind of blame is an element that separates populist rhetoric from other alternatives and represents a way to reframe appeals in a more or less populist way.

Second, we refer to the treatment as populist because other work has shown that it provokes more populist rhetoric and behavior in people’s responses to political problems (Busby et al., 2019a; Busby et al., 2019b; Wiesehomeier et al., 2025). Our claim with respect to this literature is not that these types of frames only promote more populism (prior work has not argued nor empirically demonstrated this point) but that, along with other potential effects, framing blame for problems in this manner generates more populism in what people say in response to problems of governance.

Third, we prefer this way of prompting populism – as opposed to more vignette-style treatments referencing statements by real populist actors – because it does not depend on respondents’ ideology or issues-based concerns. Instead, it is tied to whatever respondents selected prior to seeing the treatments, given the structure of these treatments. As such, the treatment is orthogonal to the issue-based considerations that are often intertwined with populism in other treatments or in the real world. It also allows us to compare individuals who care about the same issues or have the same ideological background but experienced a populist and nonpopulist blaming task.

As in previous studies, the ideational approach to populism expects this populist treatment to make populist ideas more salient in respondents’ minds and prompt more expressions of populist language. Because the elaboration technique requires participants to associate a problem with a culpable group or individual, it also likely activates negative out-group stereotypes for use in assigning causal responsibility (Corbu et al., 2019; Hameleers et al., 2019). In contrast, the control (non-populist) treatment should not result in increased expressions of populism (H2B).

Following these elaboration tasks, participants completed the experiment and were shown an information page that explained more about the experiment, the respondents’ score on the populism items, and the study’s aggregated, anonymized results.5 Our primary dependent variable – expressed populism – comes from participants’ responses to the open-ended questions, measured via a combination of human coding and supervised, machine coding. Responses were coded for three elements. The first, a mention of a responsible actor of some type, served as a manipulation check only. The other two—mentions of a conspiring elite and a good people—provided our outcome measure. Responses counted as mentioning a conspiring elite if they referred to a responsible actor that could be considered politically powerful in a democracy, such as bankers, a ruling political party, or the media; responses that blamed groups or individuals who were not politically powerful in this way—such as youth or workers in a particular sector—or that blamed an impersonal situation were coded as 0. Responses counted as mentioning a good people if they referred explicitly and in a positive light to a large number citizens suffering from the policy problem (“people like us” or “ordinary Canadians”). A response was then coded as populist if it contained mentions of both a conspiring elite and a good people, yielding a dichotomous measure. This measure was relatively discriminating, as on average, only 11.8% of responses were coded as populist.6

We began coding for our three elements by hand-coding a random subset of 4,000 responses. Research assistants who were blinded to the treatment assignment and hypotheses performed this coding after in-depth training using data from prior experiments. To code the remaining 14,000 responses, which would have been prohibitively expensive in time and money to code by hand, we brought in supervised machine coding techniques. These types of approaches combine the efficiency of computerized coding methods with the accuracy of human coding and have been used in a variety of applications to code for topics like media framing (Burscher et al., 2014; García-Marín and Calatrava, 2018) and ideology (Bonica, 2018). They can be especially useful when working with large quantities of text and complex topics (Nelson et al., 2018). Using a linear support vector classifier and oversampling on the populist responses (due to their relative infrequency – see Figure 1), we trained and tested the algorithm to code for the same three elements as the human coders (responsible actor, conspiring elite, good people). We then applied the resulting classifier on the remaining responses and, as with the original human coding, marked responses as populist if the latter two elements (conspiring elite and good people) were present. More details on this process, including the codebook for the hand-coded responses, can be found in the Online Appendix.

3 Results

Before presenting our results, we acknowledge a tradeoff in our research design. As recruitment for this study was done via self-selection into a link at the end of an article hosted by The Guardian, we do not expect this sample to be representative of the global population, the readership of The Guardian, or any particular country. Instead, we consciously trade representativity for the leverage that our sample size (approximately 18,000 individuals) and heterogeneity grant us in testing the observable implications of the ideational and issue-based theories (see Druckman and Kam, 2011; Mullinix et al., 2015; Coppock, 2018).

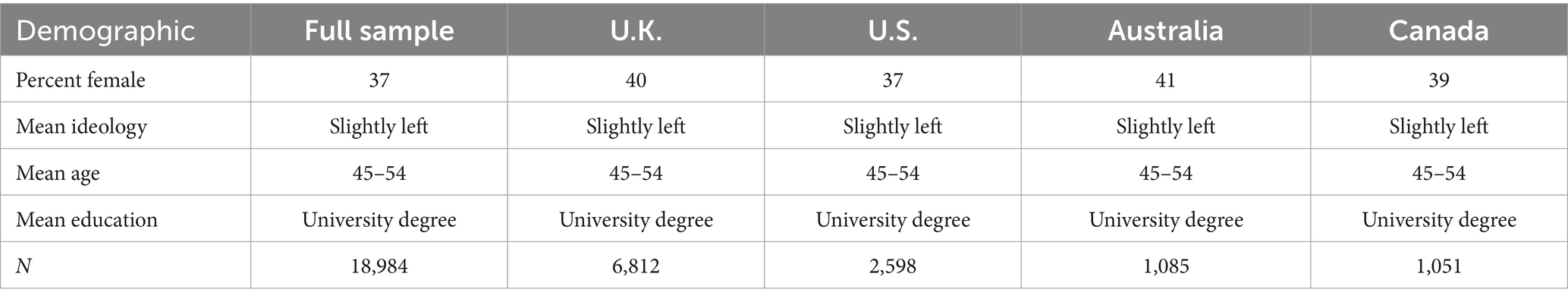

Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the entire sample and for the four largest country sub-samples. Study participants come from 155 countries, with 61 percent from the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, and Canada.7 Our participants tend to be male, leftist, middle-aged, and university educated. Hence our ability to generalize from this experiment to all kinds of individuals has limits, but even with an unrepresentative sample, the sample’s sheer size and randomization permit well-powered statistical tests of treatment effects and treatment heterogeneity. For example, although only 39 percent of the sample are not from the countries listed in Table 1, this still corresponds to over 7,000 participants from countries outside of the UK, US, Australia, and Canada. With respect to ideology, although the sample leans to the left, because of its size, our experiment contains thousands of respondents on the right. In addition, as we report in our robustness checks, multivariate analyses that control for the demographic skew of the sample find the same treatment effects. These controls include education, gender, age, general trust, and left–right ideology; in no case does the inclusion of these controls change the conclusions we present later in this manuscript.8 This is a crucial component to our design, given that our hypotheses require different kinds of interactive or moderation-focused tests (see Brookes et al., 2004; Leon and Heo, 2009).

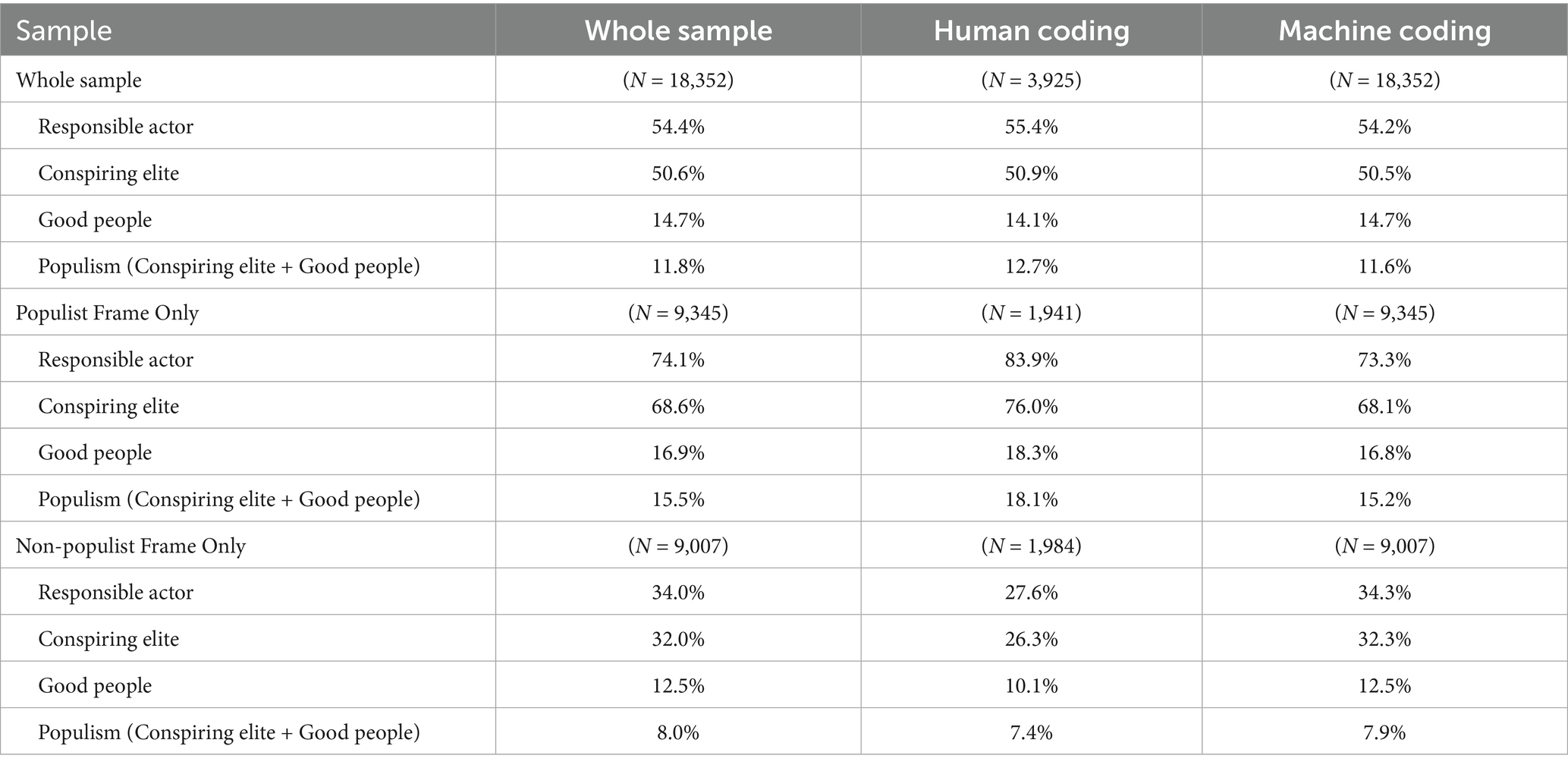

To check treatment compliance, Table 2 reports overall incidence of responsible actor in the open-ended responses in both treatment groups. While 34% mentioned a responsible actor in the non-populist frame condition, 74% mentioned one in the populist frame condition; this suggests compliance was high. These results are stronger for the human-coded portion of the data (28 and 84%, respectively) than the machine-coded portion (34 and 73%). Further comparisons across the columns of Table 2 indicates a high degree of correspondence between the overall patterns in the human and machine coding: in the whole sample, differences between the two are less than one percentage point. In the populist frame condition, the machine coding appears to underestimate the amount of populism slightly (by about 3 percentage points) whereas the opposite is true in the non-populist frame. If anything, this means our reliance on the machine coding should lead to underestimates or more conservative conclusions about the effect of populist framing.

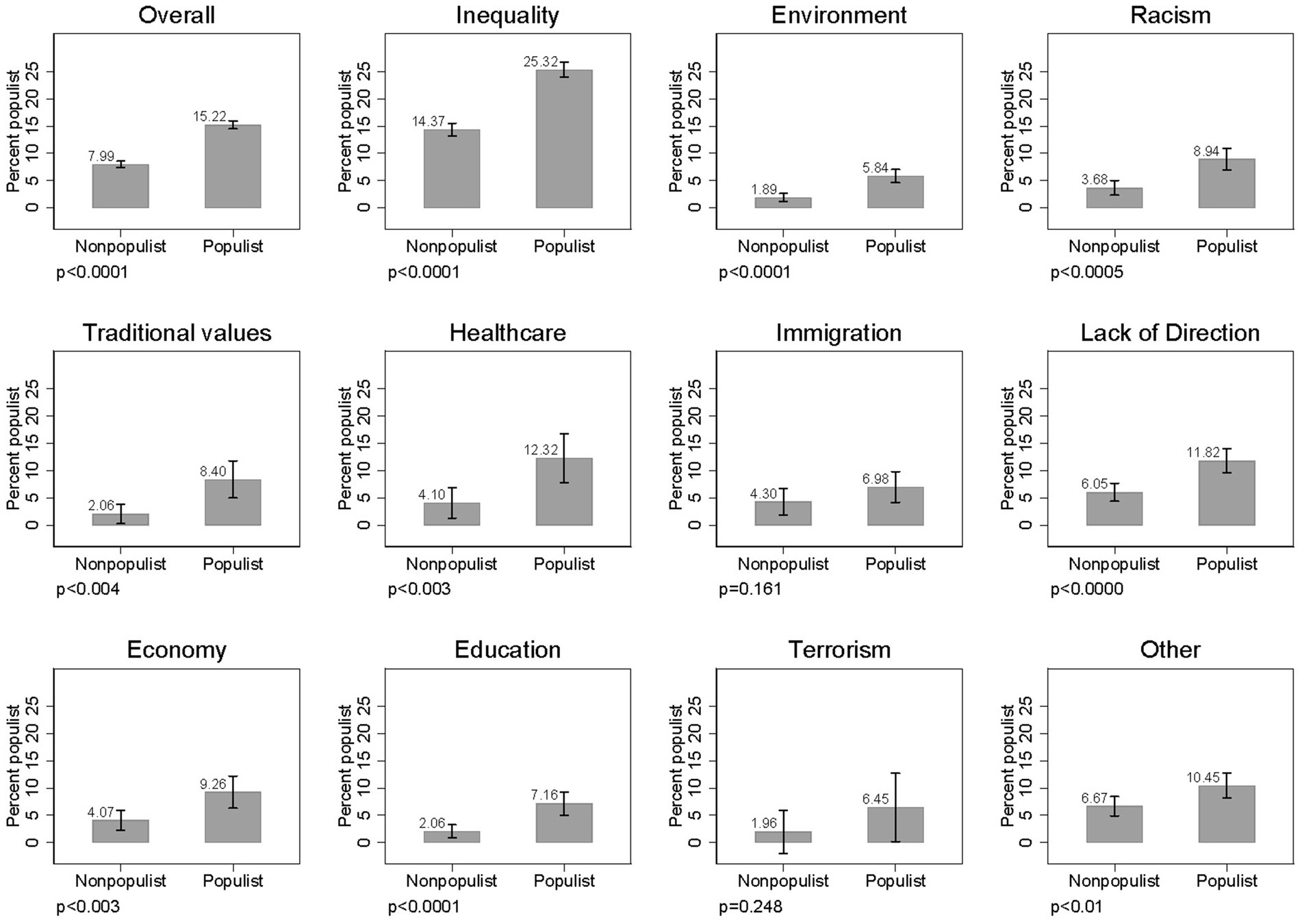

We first consider evidence in support of H1, that there should be variation in the amount of populism people express in conjunction with different political issues. As noted earlier, this is the prediction shared by both the issue and ideational approaches. In Figure 1, we present the amount of populism for each of the 11 problems respondents could have selected and broken out by treatment condition. The x-axes in these figures indicate which treatment condition the respondents were in (non-populist or populist). The y-axes indicate the percent of respondents in those conditions who wrote a populist response. Overall, we see significant variation in the amount of populism people express in response to these issues, confirming H1. Just considering the non-populist frame on the left of these panels, these issues create different amounts of populism. The issue of economic and social inequality, for example, generates the most populism, with 14.4 percent of the respondents providing a populist response in the non-populist condition. Other problems like the high cost of healthcare and a lack of direction in the government prompt more muted populist expressions (4.1 and 6.05 percent, respectively). A final group of problems is even less fertile ground for populism; environmental degradation, the poor quality of education, and the threat of terrorism prompt less than 3 percent of respondents to speak in populist ways.

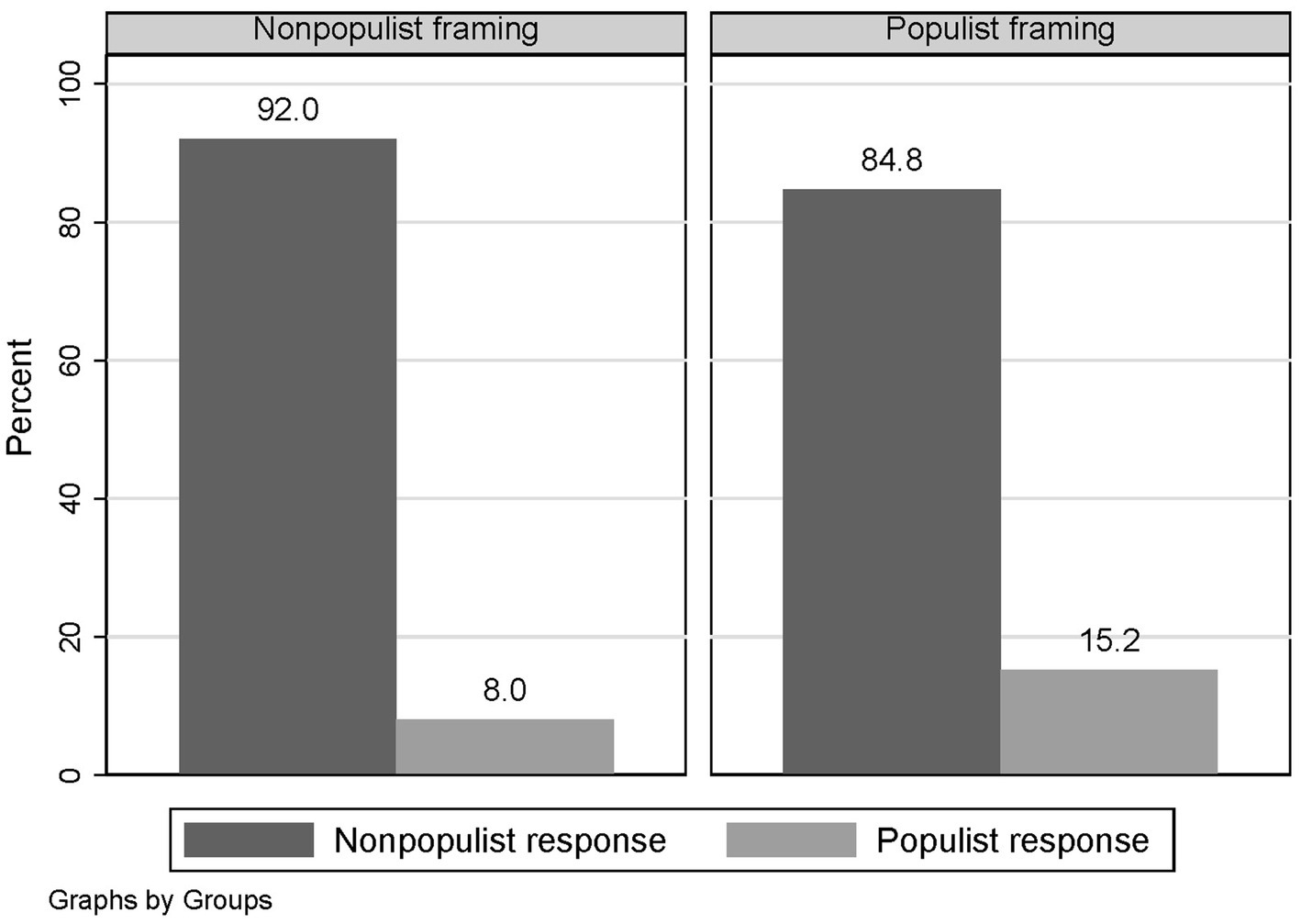

We now directly compare levels of expressed populism in the two experimental conditions, and test H2A and H2B. Only about 13 to 16 percent of respondents across both conditions expressed a populist answer (a statement referencing both a conspiring elite and the good people – see Table 2). Simply asking individuals who/what is to blame for their political problems does not necessarily generate much populism. But do populist frames lead to greater expressions of populism? If so, then more participants should express populism after assigning responsibility for policy failures in a populist way (per H2B). As participants were randomly assigned to these blame tasks, evaluating the causal impact of the populist framing requires only comparing proportions across the two groups.9

Figure 2 shows the distribution of expressed populism in the populist and nonpopulist treatment groups. We observe higher amounts of expressed populism in the populist framing condition. This difference is both substantively large (an increase of 7.2 percentage points, or a 90 percent increase, from the non-populist framing) and statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Such evidence is consistent with H2B, the hypothesis that the populist frame increases expressions of populism.10

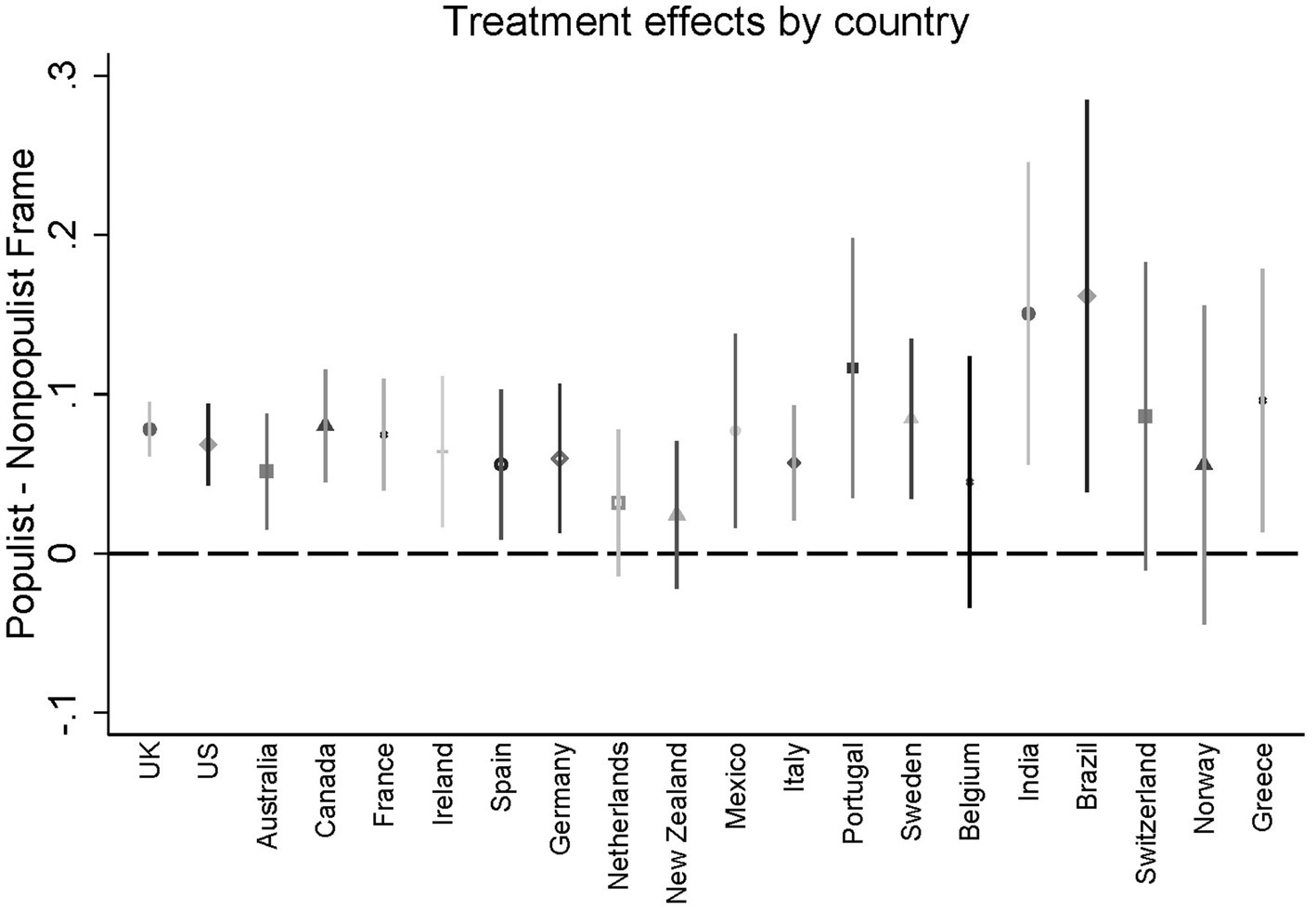

The ideational theory of populism suggests that populist framing should influence respondents in a variety of political and national contexts. Figure 3 graphs the treatment from Figure 2 across the 20 most frequent countries in our data.11 This includes prominent countries in Europe (e.g., France and Germany), those with significant traditions of populism (e.g., Switzerland), and large countries outside of Europe (e.g., Mexico, Brazil, and India). In all but five cases (Netherlands, New Zealand, Belgium, Norway, and Switerland), we observe an increase in populism in response to the populist framing. This consistency is remarkable given the differences among these countries and lends additional support to broad applicability of H2B.12

Returning to Figure 1 further illustrates the general effect of populist framing across issues. While different issues offer different baselines potential for populism, the treatment still has an effect across all of them. Using proportions tests, nine of these comparisons are significant at least at the p = 0.01 level, while two (immigration and terrorism) have a p-value higher than 0.10. In all 11 cases, treatment effects are positive and often substantively large. When considering the absolute change in expressions of populism, we see large differences between issues, with inequality, healthcare, and the economy generating the largest increases in populism. Considering relative changes in populism (e.g., a proportional change from the amount of populism in the nonpopulist frame condition) mutes some of these differences but still shows variation by issue type. As an added reliability check, we re-estimated these treatments using alternative methods that account for differences in the countries in our sample – country fixed effects with and without country-clustered standard errors.13 Since our treatment assignment was completely randomized, the populist and nonpopulists framing groups do not differ in their country composition. However, what these problems represent in each country may differ and respondents from the same country may be more like each other in expressions of populism than respondents from another country. Our alternative methods account for these possibilities. As shown in the Online Appendix, this leads to the same conclusion both in the effect size of the populist framing and tests of significance. Our conclusions should thus be robust to these specific estimation choices, and country-level differences about what these problems represent are not confounding our estimates. This is not to suggest that host ideologies and populism combine is static across context; instead, these alternative analyses indicate that populism framing has a remarkably consistent effect across contexts once we account for country-specific differences.

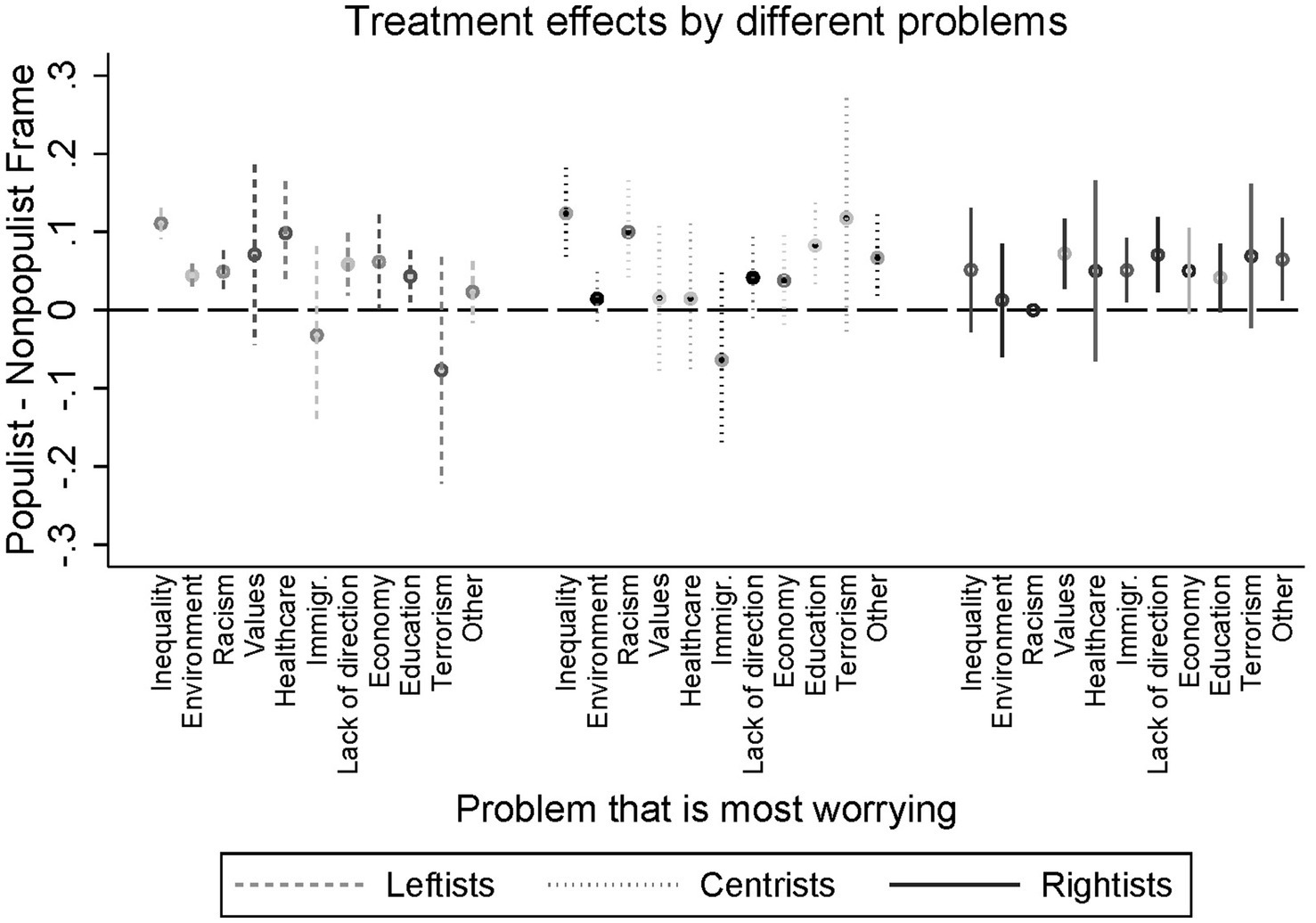

Our final hypotheses argue that the impact of ideas and issues varies in specific ways for left and right ideologies (H3A and H3B). To evaluate this proposition, we estimate the treatment comparisons separately for leftists, centrists, and rightists based on respondents’ self-placement prior to the treatments. Results presented in Figure 4 suggest where ideology does and does not matter. For example, for leftists and rightists, the economy and a lack of direction in government provide fruitful ground for populist rhetoric. In contrast, the issues of racism, the environment, and healthcare produce more populism in response to populist rhetoric for leftists. Rightists who care about these issues (and there are many in the sample) appear to be unmoved by the populist frame. However, both immigration and a decline in traditional values combined with populist rhetoric provoke more populism only for those on the right, as those on the left who focus on these topics do not react to the populist treatment. Estimating these differences using country fixed effects with and without country-clustered standard errors leads to the same conclusions (see the Online Appendix). In brief, then, the combination of issue areas and the ideological views of citizens clearly matter for understanding the consequences of the ideas of populism. Further, this occurs predictably for those on the right and left. Rightists concerned about the environment and leftists worried about immigration seem to resist populist frames, even when those frames are directly connected to these topics of concern.

Another way to consider H3A and H3B is to evaluate if adding the corresponding interactions improves our ability to understand expressions of populism. This involves nested model comparisons of a version of the analyses which does not incorporate the problem selection and individuals’ ideology with more complex models. In all cases, such a nested test suggests that adding the interaction with problem type improves our ability to predict expressions of populism. Adding the triple interaction with ideology and problem type does so further. More details can be found in the Online Appendix. We take this as an indication that our understanding of populism improves when we consider the ideas of populism in combination with ideological and issue-based content.

Two potential concerns about all of these results relate to respondent fatigue and the role of education. Participants completed a separate survey (a populism quiz hosted by the news organization The Guardian) before beginning the study discussed here. As a result, they may have begun this experiment with some amount of survey fatigue and a lack of attention. We remain confident in our results despite this concern. If this mental fatigue reduces respondents’ focus to our treatments, then the results reported here underestimate the real effect of populist framing. In addition, whatever respondent fatigue exists in this study is randomized across treatment conditions and therefore does not undermine our causal inferences. We also designed our experiment with this possibility in mind and kept our instrument brief. The timing variables in our data also indicate that respondents took the survey seriously and engaged in the treatments; for example, the median time spent on the survey was 7.5 min and the median time spent on the treatments alone was 2.7 min. Less than 5 % of respondents took fewer than 3 min on the whole experiment and under 30 s on the treatments.

Some studies suggest that individuals with less education are more susceptible to populist ideas and rhetoric (e.g., Elchardus and Spruyt, 2016; Spruyt et al., 2016). This suggests that our sample – which, as a sample of readers of The Guardian and their associates, has a higher level of education than most country-level surveys – may be more resistant to populist framing. As with respondent fatigue, however, this suggests our tests are conservative ones as our sample should be less prone to react to populist rhetoric. Furthermore, when we consider the role of education in our sample in different statistical models, we find no evidence that education acts as a confounder of our results or that level of education moderates the treatments. Again, this highlights the strength of having an extremely large sample to test for heterogenous effects. More detailed analyses can be found in the Online Appendix.

4 Discussion and conclusion

Populism’s manifestations and consequences on politics across the world remain crucial concerns for academics and policy makers. Recent examples of populist actors suggest that populism is not merely historical. In this paper, we evaluate the predictions of both issue and ideational perspectives on expressions of populism in the public.

We find evidence that expressions of populism vary dramatically across different political issues. At the same time, we observe results in our data that strongly support the ideational approach, especially when it acknowledges the role of specific issues and ideologies. When exposed some of the basic components of populist framing (e.g., blame attribution to intentional actors), people are more likely to express populist ideas themselves. This arousal is not restricted to one particular ideological camp and stretches across different national contexts. Some areas do provide more fertile ground for populism’s claims than others, and larger ideological divisions beyond populism constrain which issues can easily be framed as populist for different groups of individuals. As populism requires a host ideology to be successful, our data suggest that understanding populism requires acknowledges the ideas of populism as well as the political issues to which those ideas attempt to attach themselves.

Of course, more can be done to improve on our empirical strategy. Our study employs populist frames in isolation, but individuals likely experience multiple frames—populist, pluralist, elitist, etc.—at once. The relative strength of these ideas and how they compete with one another are questions populism researchers should investigate. Our study also omits attributes of populist messengers (such as charismatic appeal, leadership style, etc.) which could be profitably integrated. We also use one particular type of sample that we feel has a number of benefits; however, we encourage others to run similar studies on samples with different social, ideological, and demographic compositions. Furthermore, our analysis reflects the issues most salient to scholars and to each country’s citizens at the time of our experiment. We recognize that issue salience varies over time and space, a fact that both constrains the predictive power of issue-based approaches and places some scope conditions around our (and others’) experimental findings.

Our results provide an interesting comparison point for existing research that compares issue and ideational components of populism (Andreadis et al., 2019; Neuner and Wratil, 2020; Silva et al., 2022). While this research has considered some linkages between the issue and ideational notions of populism, these studies have focused on single countries or a few cases and, thus, have lacked all the components needed to evaluate our predictions. In addition, this work has not focused on citizens’ expressions of populism, emphasizing instead preferences for different parties or candidates. As such, our research here does not directly contradict those findings, given that we do not explore vote preferences nor use the same methodological tools. On the other hand, our results indicate that the ideational perspective does seem to be more useful in understanding citizens’ expressions of populism than issue- or ideologically-focused considerations. More work should be done to connect these different findings and determine the overall consequences of ideational and issue-based elements of populism.

To governments, institutions, and citizens, populism remains an important phenomenon. Given the contemporary state of politics across the world, its relevance is unlikely to go away soon. The research presented here adds to our understanding of populism by affirming that the ideas of populism are critically important, but that these ideas must be attached to specific issues and political problems. In this respect, not all political topics are interchangeable, and populist actors are not free to maneuver through policy debates unfettered. These findings suggest that actors interested in impeding the rise and success of populism would do well to emphasize topics where populism has less purchase.

Perhaps more important, the ideational approach suggests a dose of humility in our attempts to prevent or mitigate populism. As our cross-country results affirm, populist ideas and an affinity for populist rhetoric are widespread. It is best viewed as a set of ideas that is innate to democracy, a periodic phenomenon that results from an inability to create perfectly representative systems of government (Canovan, 1999; see also Stavrakakis, 2024). While populists in power can be a danger to liberal democratic institutions (Huber and Schimpf, 2016; Kenny, 2020), their rhetoric points to issues that traditional parties have overlooked and constituents that have been alienated (Cristóbal, 2012). To the degree that we can read these signs correctly and quickly, we may find antidotes to social polarization and violent conflict. Responding to populism, then, cannot be restricted to de-emphasizing specific issues or combating specific kinds of rhetoric; instead, the solutions may lie in improving democracy and proactively resolving the failures of representative systems.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://osf.io/gnkhr/.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Central European University Ethical Research Policy. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

EB: Data curation, Validation, Resources, Visualization, Methodology, Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Supervision, Investigation, Software. RC: Conceptualization, Validation, Data curation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Resources, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Software. KH: Conceptualization, Supervision, Software, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Visualization, Data curation, Formal analysis. LL: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the Department of Political Science at Clemson University, the Department of Political Science at Brigham Young University, and the Department of Political Science at Georgia State University. The authors also thank participants in a panel at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Political Science Association for feedback on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1606288/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^An important subset of the populism literature proposes a slightly different causal mechanism, arguing that concerns over social status (driven by material and cultural issues mentioned here) are the real driving force behind populist parties and ideas (c.f. Spruyt et al., 2016). Unfortunately, we are unable to test this argument here.

2. ^We note that this process does not require us to claim or test if such populist expressions are deeply held or more transient. Instead, populist considerations exist in the minds of many in a latent and can be primed and made more relevant and salient. In response to other frames or contexts, these expressions may become further heightened or more dormant.

3. ^The legal definition of an adult varies among the countries in our sample; we use 18 years old as a rough way to exclude individuals legally defined as minors.

4. ^The most common response is economic and social inequality which is mentioned approximately 40 percent of the time. This is mirrored in high levels of concerns in countries worldwide about the economy (see Nadler, 2025).

5. ^The experiment included other variables after our populism treatments and open-ended questions. None were included in any analyses or designed to test the hypotheses presented here.

6. ^Studies using the ideational approach (including our own elsewhere) often argue for using continuous measures of populism. However, the open-ended responses that we coded are too short to allow this. Our requirement that responses include both a conspiring elite and a good people follows the non-compensatory logic articulated by Wuttke et al. (2020). We suspect that the result generally undercounts the level of populism in open-ended responses.

7. ^We restrict our focus to these four countries as this follows our preregistered analysis plan. We do, however, consider a larger range of countries as a robustness check.

8. ^It is always possible that the sample is biased in important ways that do not correspond to the variables we have observed; this is a limit of any attempt to account for confounding through the use of control variables in regression-style models. For our purposes here, we note that we observe no confounding from the variables we do observe and present subgroup analyses throughout to assess the generalizability of our results as much as we can.

9. ^Some recommend evaluating if treatment groups are balanced, although this is debated (e.g., Mutz et al., 2017). We remain agnostic about such tests but mention that we found no reliable demographic differences between conditions.

10. ^This pattern persists among those with high, medium, and low levels of pre-treatment populism, although the effects are larger for those high in populism. See the Online Appendix.

11. ^Our preregistration explicitly discussed looking at the top 4 countries (UK, US, AU, and CA); we include the others as additional comparisons points in different political contexts.

12. ^Sample sizes were: UK: 6812; US: 2598; Australia: 1085; Canada: 1051; France: 999; Ireland: 557; Spain: 507; Germany: 451; Netherlands: 491; New Zealand: 400; Mexico: 349; Italy: 320; Portugal: 208; Sweden: 230; Belgium: 182; India: 162; Brazil: 143; Switzerland: 119; Norway: 134; Greece: 141.

13. ^One consideration is the number of fixed effects and clustering units. To provide many clusters while still having numerous respondents within each cluster, we created indicators for each country that had at least 30 observations. This covered 98 percent of the respondents and created 52 units: 51 countries and a category for the remaining participants.

References

Abts, K., Kochuyt, T., and van Kessel, S. (2019). “Populism in Belgium: the mobilization of the body anti-politic” in The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis. eds. K. A. Hawkins, R. Carlin, L. Littvay, and C. R. Kaltwasse (Abingdon: Routledge).

Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., and Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comp. Pol. Stud. 47, 1324–1353. doi: 10.1177/0010414013512600

Akkerman, A., Zaslove, A., and Spruyt, B. (2017). ‘We the people’or ‘we the peoples’? A comparison of support for the populist radical right and populist radical left in the Netherlands. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 23, 377–403. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12275

Andreadis, I., Hawkins, K. A., Kaltwasser, C. R., and Singer, M. M. (2019). “The conditional effects of populist attitudes on voter choices in four democracies” in The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis. eds. K. A. Hawkins, R. Carlin, and L. Littvay (Abingdon: Routledge).

Aslanidis, P. (2016). Is populism an ideology? A refutation and a new perspective. Polit. Stud. 64, 88–104. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12224

Betz, H.-G. (2017). Nativism across time and space. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 23, 335–353. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12260

Betz, H.-G. (2019). “Popuist mobilization across time and space” in The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and method. eds. K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, and C. R. Kaltwasser (Abingdon: Routledge).

Bonica, A. (2018). Inferring roll-call scores from campaign contributions using supervised machine learning. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 62, 830–848. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12376

Brookes, S. T., Whitely, E., Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Mulheran, P. A., and Peters, T. J. (2004). Subgroup analyses in randomized trials: risks of subgroup-specific analyses: power and sample size for the interaction test. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 57, 229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.08.009

Burscher, B., Odijk, D., Vliegenthart, R., de Rijke, M., and de Vreese, C. H. (2014). Teaching the computer to code frames in news: comparing two supervised machine learning approaches to frame analysis. Commun. Methods Meas. 8, 190–206. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2014.937527

Busby, E. C., Doyle, D., Hawkins, K. A., and Wiesehomeier, N. (2019a). “Activating populist attitudes: the role of corruption” in The ideational approach to populism: concept, theory, and method. eds. K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, and C. R. Kaltwasser (New York: Routledge), 374–395.

Busby, E. C., Gubler, J. R., and Hawkins, K. A. (2019b). Framing and blame attribution in populist rhetoric. J. Polit. 81, 616–630. doi: 10.1086/701832

Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Polit. Stud. 47, 2–16.

Cardoso, F. H., and Faletto, E. (1979). Dependency and development in Latin America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Chong, D., and Druckman, J. N. (2007). Framing theory. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 10, 103–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00331_3.x

Cleen, D. B., and Stavrakakis, Y. (2017). Distinctions and articulations: a discourse theoretical framework for the study of populism and nationalism. Javn. - Public 24, 301–319. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2017.1330083

Conniff, M. L. (1982). Latin American populism in comparative perspective. New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press.

Coppock, A. (2018). Generalizing from survey experiments conducted on mechanical Turk: a replication approach. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 7, 1–16. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2018.10

Corbu, N., Bos, L., Schemer, C., Schulz, A., Matthes, J., de Vreese, C. H., et al. (2019). “Cognitive responses to populist communication: the impact of populist message elements on blame attribution and stereotyping” in Communicating populism: comparing actor perceptions, media coverage, and effect on citizens in Europe. eds. C. Reimann, J. Stanyer, and T. Aalberg (New York: Routledge).

Cramer, K. J. (2016). The politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cristóbal, R. K. (2012). The ambivalence of populism: threat and corrective for democracy. Democratization 19, 184–208. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2011.572619

Dai, Y., and Kustov, A. (2024). The (in)effectiveness of populist rhetoric: a conjoint experiment of campaign messaging. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 12, 849–856. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2023.55

Dornbusch, R., and Edwards, S. (1990). Macroeconomic populism. Journal of development economics 32, 247–277.

Druckman, J. N., and Kam, C. D. (2011). “Students as experimental participants: a defense of the ‘narrow data base” in Cambridge handbook of experimental political science. eds. J. N. Druckman, D. P. Green, J. H. Kuklinski, and A. Lupia (New York: Cambridge University Press).

Edwards, S. (2010). Left behind: Latin America and the false promise of populism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago press.

Elchardus, M., and Spruyt, B. (2016). Populism, persistent republicanism and Declinism: an empirical analysis of populism as a thin ideology. Gov. Oppos. 51, 111–133. doi: 10.1017/gov.2014.27

Espejo, O. P. (2011). The time of popular sovereignty: process and the democratic state. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Ferguson, N. (2016). Populism as a backlash against globalization: historical perspectives. Horizons no. 8, 12–23. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48573684

Ferrari, D. (2024). The effect of combining a populist rhetoric into right-wing positions on candidates’ electoral support. Elect. Stud. 89, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2024.102787

Freeden, M. (1996). Ideologies and political theory: A conceptual approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

García-Marín, J., and Calatrava, A. (2018). The use of supervised learning algorithms in political communication and media studies: locating frames in the press. Commun. Soc. 31, 175–188. doi: 10.15581/003.31.3.175-188

Germani, G. (1978). Authoritarianism, fascism, and National Populism. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Gidron, N., and Hall, P. A. (2019). Populism as a problem of social integration. Compar. Polit. Stud. 53:79947. doi: 10.1177/0010414019879947

Hameleers, M., Bos, L., and De Vreese, C. H. (2016). They did it’ the effects of emotionalized blame attribution in populist communication. Commun. Res. 44, 1–31. doi: 10.1177/0093650216644026

Hameleers, M., Bos, L., Fawzi, N., Reinemann, C., Andreadis, I., Corbu, N., et al. (2018). Start spreading the news: a comparative experiment on the effects of populist communication on political engagement in sixteen European countries. Int. J. Press/Politics 23, 517–538. doi: 10.1177/1940161218786786

Hameleers, M., and Fawzi, N. (2020). Widening the divide between them and us? The effects of populist communication on cognitive and affective stereotyping in a comparative European setting. Polit. Commun. 37, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2020.1723754

Hameleers, M., Reinemann, C., Schmuck, D., and Fawzi, N. (2019). “Conceptualizing the effects and political consequences of populist communication from a social identity perspective” in Communicating populism: Comparing actor perceptions, media coverage, and effect on citizens in Europe. eds. C. Reimann, J. Stanyer, T. Aalberg, F. Esser, and C. H. Vreese (London: Routledge), 183–206.

Hawkins, K. A., Carlin, R., Littvay, L., and Kaltwasser, C. R. (2019). The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis. Extremism and democracy. London: Routledge.

Huber, R. A., and Schimpf, C. H. (2016). Friend or foe? Testing the influence of populism on democratic quality in Latin America. Polit. Stud. 64, 872–889. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12219

Hunger, S., and Paxton, F. (2021). What’s in a buzzword? A systematic review of the state of populism research in political science. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 10, 1–17. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2021.44

Jagers, J., and Walgrave, S. (2007). ‘Populism as political communication style: an empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium. Eur J Polit Res 46, 319–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

Jenne, E. K., Hawkins, K. A., and Silva, B. C. (2021). Mapping populism and nationalism in leader rhetoric across North America and Europe. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 56, 170–196. doi: 10.1007/s12116-021-09334-9

Kazin, M. (1998). The populist persuasion: An American history. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Kenny, P. D. (2020). ‘The enemy of the people’: populists and press freedom. Polit. Res. Q. 73, 261–275. doi: 10.1177/10659129188240

Klar, S., Robison, J., and Druckman, J. N. (2013). “Political dynamics of framing” in New directions in media and politics. ed. T. N. Ridout (New York: Routledge).

Leon, A. C., and Heo, M. (2009). Sample sizes required to detect interactions between two binary fixed-effects in a mixed-effects linear regression model. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 53, 603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.csda.2008.06.010

Lowndes, J. (2017). “Populism in the United States” in The Oxford handbook of populism. eds. C. R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. O. Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 232–247.

Mudde, C. (2004). The Populist Zeitgeist. Gov. Oppos. 39, 542–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

Mudde, C. (2017). “Populism: an ideational approach” in The Oxford handbook of populism. eds. C. R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. O. Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Mullinix, K. J., Leeper, T. J., Druckman, J. N., and Freese, J. (2015). The generalizability of survey experiments. J. Exper. Polit. Sci. 2, 109–138. doi: 10.1017/XPS.2015.19

Mutz, D. C., Pemantle, R., and Pham, P. (2017). The perils of balance testing in experimental design: messy analyses of clean data. Am. Stat. 73:2143. doi: 10.1080/00031305.2017.1322143

Nelson, L. K., Burk, D., Knudsen, M., and McCall, L. (2018). The future of coding: a comparison of hand-coding and three types of computer-assisted text analysis methods. Sociol. Methods Res. 50, 202–237. doi: 10.1177/0049124118769114

Neuner, F. G., and Wratil, C. (2020). The populist marketplace: unpacking the role of ‘thin’ and ‘thick’ ideology. Polit. Behav. 44:629. doi: 10.1007/s11109-020-09629-y

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash and the rise of populism: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rodrik, D. (2017). Populism and the economics of globalization. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Rogenhofer, J. M., and Panievsky, A. (2020). Antidemocratic populism in power: comparing Erdoğan’s Turkey with Modi’s India and Netanyahu’s Israel. Democratization 27, 1394–1412. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2020.1795135

Rooduijn, M., de Lange, S. L., and van der Brug, W. (2012). A populist zeitgeist? Programmatic contagion by populist parties in Western Europe. Party Polit. 20:6065. doi: 10.1177/1354068811436065

Ruth-Lovell, S. P., David, D., and Kirk, A. H. (2019). Consequences of Populism Memo for The Guardian’s New Populism Project. Team Populism. Available at: https://populism.byu.edu/0000017d-bf5b-d420-afff-bf7f898c0001/tp-consequences-memo-pdf

Scott, Z. (2023). Inviting the populists to the party: populist appeals in presidential primaries. Polit. Res. Q. 76, 1827–1842. doi: 10.1177/10659129231181558

Silva, B. C., Andreadis, I., Anduiza, E., Blanuša, N., Corti, Y. M., Delfino, G., et al. (2019). “Public opinion surveys: a new measure” in The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and method. eds. K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, and C. R. Kaltwasser (New York: Routledge), 150–178.

Silva, B. C., Neuner, F. G., and Wratil, C. (2022). Populism and candidate support in the US: the effects of ‘thin’ and ‘host’ ideology. J. Exper. Polit. Sci. 10, 1–10. doi: 10.1017/XPS.2022.9

Spruyt, B., Keppens, G., and Van Droogenbroeck, F. (2016). Who supports populism and what attracts people to it? Polit. Res. Q. 69, 335–346. doi: 10.1177/1065912916639138

Surdea-Hernea, V. (2025). The populist spiral: how populist rhetoric spreads within party systems. Party Polit. 27:1394. doi: 10.1177/13540688251362306

di Tella, T. (1965). “Populism and reform in Latin America” in Obstacles to change in Latin America. ed. C. Véliz (London: Oxford University Press), 47–74.

van Hauwaert, S., and van Kessel, S. (2018). Beyond protest and discontent: a cross-national analysis of the effect of populist attitudes and issue positions on populist party support. Eur J Polit Res 57, 68–92. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12216

Walicki, A. (1969). “Russia” in Populism: Its meaning and National Characteristics. eds. G. Ionescu and E. Gellner (New York: The Macmillan Company), 62–96.

Weffort, F. C. (1978). O Populismo Na Política Brasileira. Coleção Estudos Brasileiros. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

Wiesehomeier, N., Busby, E. C., and Flynn, D. J. (2025). “Populism and misinformation” in The ideational approach to populism: consequences and mitigation. eds. A. Chryssogelos, E. T. Hawkins, K. A. Hawkins, L. Littvay, and N. Wiesehomeier (New York: Routledge).

Keywords: populism, experiment, blame, ideational, issues, cross-national

Citation: Busby EC, Carlin RE, Hawkins KA and Littvay L (2025) Speaking populism: ideational vs. issue-based theories of populism. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1606288. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1606288

Edited by:

John Eaton, Florida Gateway College, United StatesReviewed by:

Fred Paxton, University of Glasgow, United KingdomErnesto Dominguez Lopez, Agricultural University of Havana, Cuba

Copyright © 2025 Busby, Carlin, Hawkins and Littvay. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ethan C. Busby, ZXRoYW4uYnVzYnlAYnl1LmVkdQ==

Ethan C. Busby

Ethan C. Busby Ryan E. Carlin

Ryan E. Carlin Kirk A. Hawkins

Kirk A. Hawkins Levente Littvay

Levente Littvay