- 1Department of Religion Studies, Institute of Philosophy, Political Science and Religious Studies, Committee of Science, Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (CS MSHE RK), Almaty, Kazakhstan

- 2Faculty of Humanities and Law, Higher School of International Relations and Diplomacy, Turan University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

This research investigates the transformation of Kazakhstan's religious landscape following independence from the Soviet Union, with particular emphasis on state regulatory mechanisms governing Islamic practices. The study examines the historical trajectory of Islam in Kazakhstan from its eighth-century origins through the Soviet period to contemporary developments, addressing the balance between secular governance and religious freedom in a context of growing Islamic identification. The study adopts a longitudinal approach and employs a mixed-methods design combining quantitative archival analysis with qualitative field research. Primary data sources include population census records (1999, 2009, 2021), legislative documentation, and statistical data on religious institutions. These quantitative materials are supplemented by semi-structured interviews with Muslim community representatives. The analytical framework integrates demographic, institutional, and policy perspectives with community-based insights. Demographic analysis reveals significant shifts in religious identification patterns, with Muslims constituting approximately 70% of the national population by 2021. Institutional growth was marked by an increase from 2,685 Islamic organizations in 2020 to 2,832 in 2024. Educational analysis indicates that 12 of 14 existing spiritual educational establishments focus on Islamic studies. Content analysis of governmental and media sources confirms sustained institutional expansion and a pronounced orientation toward Islamic education. Legislative changes in response to security incidents in 2011 and 2016 introduced restrictions on freedom of conscience aimed at countering extremism and terrorism. The findings demonstrate that Kazakhstan has developed a distinctive model of state-religious relations integrating secular governance with recognition of Islam's historical and cultural significance. Despite suppression during the Soviet era, Islamic practices and institutions have undergone substantial revival under careful state regulation. The regulatory approach reflects a strategic balance between supporting traditional religious practices and safeguarding national security, offering a unique post-Soviet model of religious governance relevant for broader Central Asian comparative analysis.

1 Introduction

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the achievement of independence, the governments of all former Soviet republics, including Kazakhstan, confronted substantial challenges in transforming political, cultural, economic, and social structures. The fundamental transformation of political systems, coupled with the departure from centralized state governance, significantly facilitated the formation of national identity and distinctiveness. This transformation necessitated a comprehensive reevaluation of religion's role within a state historically dominated by Soviet atheistic traditions. In Kazakhstan's context, where Islam constitutes the predominant religion [The Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), 2020], this issue assumes relevance, reflecting the population's aspiration to preserve cultural values amid rapid globalization processes.

The contemporary imperative for many nations to achieve equilibrium between tradition preservation and integration into an interconnected, technologically advanced world renders this question equally significant and pertinent. Within this framework, Islamic modernization emerges as both a religious and socio-political phenomenon influencing diverse domains—from education to legal policy and the development of state-religious institutional relations. Given the increasing religiosity concerning Islam in Kazakhstan [The Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), 2020], research into this phenomenon provides opportunities to identify aspects of state oversight within the religious sphere.

Global processes, including information integration and strengthened intergovernmental ties, have intensified cultural exchange, thereby heightening the necessity to adapt religious practices to globalized conditions. Digital technology development exemplifies this adaptation, enabling believers to connect with religious figures in remote domestic regions and internationally. This connectivity can strengthen religious identity while mitigating radicalization threats—an issue of relevance to Kazakhstan (Beyer and Finke, 2019).

Examining Islamic modernization in Kazakhstan proves crucial as it provides a paradigmatic example for other Central Asian countries where religion similarly plays a significant role in state socio-political life. Given the extensive range of contemporary social and political challenges—including violent extremism and radicalization threats—Islamic modernization emerges as a mechanism for ensuring stability and preserving national identity.

Within this study's context, the problem of radical Islamist movements assumes prominence. Mukan et al. (2023) explored this issue, noting that radical Islamist movements in Kazakhstan have established educational centers, while religious activists seek to close institutions promoting radical ideologies and engaging in other destructive activities. Another critical issue concerns the suppression of national movements during the Soviet period. Kassimbekova (2024) reported that during the USSR era, interest among Kazakhs in their country decreased by 40%, with both language and religion experiencing significant restrictions. Islamic modernization has been discussed by Kartabayeva (2019), who argued that Islamic leaders should focus on purging religion of negative phenomena contributing to stagnation, including prejudice, ignorance, and folly.

Zhumagulov and Kartabayeva (2020) observed that all Islamic branches found in the Middle East exist in Kazakhstan, creating a potentially dangerous situation that could lead to fragmentation within the country's already limited population. Dinasheva et al. (2023) noted that during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Kazakhs experienced significant influence from imperial policies, with Russian school establishment in Turkestan contributing to population Russification. The division between secular and theocratic state systems presents another significant area of inquiry. Despite formal state-religion separation in Kazakhstan, Zhumagulov and Kartabayeva (2020) identified persistent contradictions, exemplified by the coexistence of Kurban Ait (Eid al-Adha) celebrations and Christmas recognition as public holidays with the state's secular nature, which remains a driving force for Kazakhstan's sustainable development.

Despite formal state-religion separation in Kazakhstan, Jumashov and Sadvokasov (2022) identified persistent contradictions, exemplified by the coexistence of Kurban Ait (Eid al-Adha) celebrations and Christmas recognition as public holidays with the state's secular nature, which remains a driving force for Kazakhstan's sustainable development.

The significance of religion for Central Asian peoples has been emphasized by Olcott (2023), who observed that throughout seven decades of Soviet rule, most regional populations continued to honor and celebrate significant Muslim events. Sartori (2021) noted that religious component studies in Central Asia improved substantially following Tasar's work publication, which identified the institutional space occupied by religion during Soviet rule in the region.

Based on the considerations, this study's objective is to explore the transformation of Kazakhstan's religious landscape following independence. The research tasks include examining Islam's history in Kazakhstan, analyzing population census data regarding Muslims, and identifying governmental mechanisms for religious sphere regulation.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Research design

This study employs a mixed-methods design combining quantitative archival analysis with qualitative field research to examine the transformation of Islamic identity in post-Soviet Kazakhstan. The methodological framework integrates contemporary community perspectives with documented historical processes through systematic analysis of primary data sources including population census records, legislative documentation, statistical data on religious institutions, and semi-structured interviews with Muslim community representatives.

2.2 Data sources and selection criteria

Population census data from three temporal points (1999, 2009, and 2021) were selected to establish demographic trends in religious affiliation (Committee on Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 1999, 2011, 2022). These sources were chosen based on their official status, comprehensive national coverage, and temporal consistency enabling longitudinal analysis.

Legislative documents, specifically the “Law on Religious Activity and Religious Associations” (Online Zakon, 2011a), were analyzed as primary regulatory frameworks governing religious practice. Official statistical data on religious institutions were obtained from the Committee for Religious Affairs under the Ministry of Culture and Information of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Committee on Religious Affairs of the Ministry of Culture Information of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2020; Ministry of Religious Affairs of Kazakhstan, 2024a) and the Government of Kazakhstan website (Ministry of Religious Affairs of Kazakhstan, 2024b), selected for their authoritative status and regular updating protocols.

Secondary sources were systematically selected based on three criteria: (1) institutional credibility, (2) temporal relevance to post-Soviet developments, and (3) analytical depth. Resources from the Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting under the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (CABAR Asia, 2020) and the e-history.kz portal (E-history.kz, 2021) were included for their specialized regional expertise and comprehensive historical coverage.

International perspectives were incorporated through U.S. Embassy reports (U.S. Embassy Consulate in Kazakhstan, 2022) and Deutsche Welle publications (Deutsche Welle, 2024) to ensure analytical balance and external validation. Additional sources on religious developments included academic publications (E-history.kz, 2013), survey data from the World Values Survey (CABAR Asia, 2024a), and specialized institutional reports (Nur-Mubarak University, 2022).

2.3 Analytical methods

Content analysis was conducted using a structured coding framework based on predetermined thematic categories: (1) historical development of Islam, (2) demographic changes, (3) state-religion relations, (4) institutional development, and (5) contemporary challenges. Each source was systematically coded using NVivo 12 software, with inter-coder reliability established through dual coding of 20% of materials by two independent researchers, achieving Cohen's kappa coefficient of 0.84.

The unit of analysis varied by source type: for legislative documents, individual articles and provisions; for media reports, complete articles; for census data, statistical tables and demographic categories. Coding schema employed both deductive categories derived from theoretical frameworks on post-Soviet religious transformation and inductive themes emerging from the data.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Quantitative data analysis was performed using SPSS 28.0, employing descriptive statistics for demographic trends and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Temporal trend analysis utilized linear regression models to identify significant changes in religious affiliation rates across census periods. Correlation analysis examined relationships between institutional growth (mosques, educational facilities) and demographic changes using Pearson correlation coefficients.

Census data validation involved cross-referencing with World Values Survey findings and international demographic reports to assess consistency and identify potential discrepancies. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

2.5 Qualitative interview analysis

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 practicing Muslims selected through stratified random sampling across Kazakhstan's major urban centers (Almaty, Nur-Sultan, Shymkent, n = 9) and rural regions (n = 6). Sampling frame was established using community organization membership lists, ensuring representation across age groups (18–65 years), gender (40% female, 60% male), and educational backgrounds.

Interview protocols focused on: (1) personal experiences with religious practice, (2) perceptions of state policies, (3) community dynamics, and (4) generational changes in religious observance. Interviews lasted 45–90 min, were audio-recorded with consent, and transcribed verbatim in Kazakh/Russian with professional translation to English.

Thematic analysis followed Braun and Clarke's six-phase approach: familiarization, initial coding, theme development, theme review, definition and naming, and report production. Analysis was conducted using Atlas.ti 9, with member checking performed through participant validation of key findings.

2.6 Data integration and triangulation

Mixed-methods integration employed a convergent parallel design where quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed independently then merged during interpretation. Triangulation protocols included: (1) source triangulation across government, academic, and media sources; (2) methodological triangulation combining statistical and interview data; and (3) investigator triangulation through collaborative analysis by multiple researchers.

2.7 Limitations and bias considerations

Several methodological limitations were identified and addressed: (1) Potential government bias in official statistics was mitigated through cross-validation with international survey data; (2) Media source selection bias was controlled through systematic inclusion of diverse institutional perspectives; (3) Interview sample size limitations were acknowledged, with findings presented as exploratory rather than generalizable; (4) Language translation effects were minimized through professional translation services and back-translation verification for key concepts.

Temporal limitations include the focus on post-1991 developments, which may underrepresent pre-Soviet Islamic traditions, and the reliance on available census categories that may not capture the full complexity of religious identity.

2.8 Ethical considerations

All interview participants provided informed consent, with anonymity guaranteed through pseudonym usage. The study received approval from the institutional ethics committee, and data storage followed confidentiality protocols with encrypted digital files and secure physical storage for hard copies.

2.9 Contextual framework

Kazakhstan, the world's largest landlocked country and ninth-largest nation globally, occupies a strategic position in Central Asia between Russia and China, with its territory spanning 2.7 million square kilometers and hosting a population of ~19.4 million people comprising over 130 ethnic groups. The country's historical trajectory as a crossroads of the Great Silk Road, its subsequent incorporation into the Russian Empire in the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries, seven decades under Soviet rule (1920–1991), and eventual independence in 1991 have profoundly shaped its contemporary religious landscape, creating a unique context where traditional Kazakh culture, Islamic heritage, Soviet secular legacy, and modern globalization processes intersect to influence religious identity and practice among the predominantly Muslim population.

3 Results

3.1 Historical development and state regulation of Islam

The establishment of Islam in the territory of modern Kazakhstan is intrinsically linked to Arab expansion into the region during the eighth to ninth centuries CE. The pivotal events of this period, involving Arabs and the Chinese Tang Dynasty, culminated in the Battle of Talas, which also witnessed the participation of the Turkic Karluk people, according to historian Zhusupova and Sabitov (2024). The Karluks emerged as beneficiaries of this struggle, and in 840 CE, their ruler declared himself the leader of a Turkic state. By this time, Islam had already established its presence in the territory of modern Kazakhstan. Turkologist S. Khizmetli proposes a slightly later timeline, asserting that the ancestors of Kazakhs began converting to Islam in the tenth century, coinciding with the formation of Muslim states such as Volga Bulgaria in 921, the Karakhanids in 945, the Ghaznavids in 963, and the Seljuks in 1038.

A significant strengthening of Islam in the region occurred under the rule of Amir Timur in the late fourteenth century (E-history.kz, 2021). During this period, theological centers of Hanafi jurisprudence were established, and the works of the Sufi poet Khoja Ahmed Yasawi were widely disseminated among the nomadic populations in southern Kazakhstan. In honor of Yasawi, a grand mausoleum—an architectural masterpiece of global significance—was erected in the fourteenth–fifteenth centuries, becoming the most prominent Islamic monument in Kazakhstan.

The colonial period marked a crucial turning point in attitudes toward Islam. The Russian imperial government actively promoted Christianity among the nomads of Kazakhstan and neighboring regions, though these efforts yielded limited results. Subsequently, Islam's spread was managed through oversight by Tatar mullahs and other representatives of the Russian clergy. The large-scale resettlement of Russians in Kazakhstan contributed to the ethnic division of the region into northern and southern parts. Russian authorities perceived Islam as a potential threat to colonial policy and imperial integrity. By 1917, a pan-Kazakh congress proposed separating religion from the state in its programmatic documents. However, subsequent congresses and their decisions were annulled following the rise of Soviet power (Toleubay et al., 2024).

In the 1920s, early Soviet policies allowed Muslims in Central Asia to work in schools and even teach religious doctrine in institutions for children. However, the anti-religious campaigns that began in the late 1920s and lasted until 1941 marked a decisive turning point. These campaigns, alongside the abandonment of the New Economic Policy (NEP), significantly curtailed religious freedoms (New Economic Policy, 2024). According to Sheriyazdanov, a senior researcher at the Institute of State History under the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of Kazakhstan, anti-religious policies did not fully achieve their goals. Research conducted in Kazakhstan in the late 1980s revealed that the proportion of believers or those sympathetic to religion ranged from 20% to 70%, depending on the region.

Kazakhstan's approach to religious regulation has evolved significantly since independence. One of the key legislative acts is the Law on Religious Activities and Religious Associations (Online Zakon, 2011a), which establishes that the state is secular and separated from religion, with all citizens and stateless individuals being equal before the law regardless of their faith. The law stipulates that the education system (except for specialized institutions) is detached from religion and provides for the creation of religious associations at local, regional, and national levels.

According to a study by the Stockholm-based Institute for Security and Development Policy (Cornell et al., 2018), Kazakhstan's secular governance model aligns more closely with skepticism and isolationism as seen in Turkey or France, rather than the neutrality exemplified by the United States. This approach means that the government supports and promotes traditional religious communities to restore their societal role while opposing the spread of non-traditional doctrines within the country, reflecting a “dominant religion” model with specific nuances that encourage the development of all traditional religions without favoring anyone.

Social and political events have significantly influenced religious regulation over time. A series of terrorist attacks in 2011 in the Aktobe region, Atyrau, Taraz and a village in Almaty region (Masa Media, 2023) led to legislative amendments. The October 2011 Law on Religious Activities and Religious Associations introduced measures such as denying missionary registration for citizens, foreigners, or stateless individuals based on negative conclusions from theological reviews or if such activities were deemed threats to the constitutional order, public safety, individual rights and freedoms, or public health and morality (Online Zakon, 2011a). Following another terrorist attack in 2016 (Masa Media, 2023), with officials linking the perpetrators to radical Takfiri Islamic ideology and ISIS, Kazakhstan implemented additional educational measures, including the mandatory subject “Secularism and Basics of Religious Studies” in schools starting from the ninth grade.

3.2 Contemporary religious landscape and institutional growth

The question of religious affiliation in Kazakhstan's population during the 1990s remains complex, as the 1999 population census did not include questions about religion, focusing instead on population size, gender and age distribution, marital status, education, and proficiency in the state language (Committee on Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 1999). Religious affiliation questions were included in the censuses conducted in 2009 and 2021, providing clearer data on the country's religious landscape (Table 1). While numerical data might suggest a decline in the proportion of Muslims in Kazakhstan, this primarily reflects overall population growth. A more significant trend is the noticeable reduction in the number of Christians: in 2009, one in four census respondents identified as Christian, whereas in 2021, this figure dropped to one in five.

Table 1. Religious affiliation in Kazakhstan according to the 2009 and 2021 censuses (table placeholder: provide the exact data breakdown for the 2009 and 2021 censuses when available).

Analyzing rural and urban distinctions reveals notable differences in religious affiliation. In 2009, 61.1% of the urban population identified as Muslim compared to 81% in rural areas. By 2021, these numbers shifted to 64.4% for urban Muslims and 76.8% for rural Muslims. According to the Central Asia Bureau for Analytical Reporting (CABAR Asia, 2022), the 2009 census captured even those who identified with a religion more out of tradition than personal faith. Despite the complexity of accurately tracking the number of Muslims over a long period, census results consistently indicate that Islam remains the predominant religion in Kazakhstan.

Data from the World Values Survey in 2011 and 2018 further highlight a rise in religiosity among Kazakhstanis (CABAR Asia, 2024a,b). When asked about the importance of religion, responses shifted significantly over time: in 2011, 21.5% considered religion very important, increasing to 28.7% in 2018. Those who found religion “rather important” rose slightly, from 33.5% in 2011 to 35.5% in 2018. The proportion of individuals who considered religion unimportant dropped from 11.4% to 8.9%. More dramatic changes emerged in religious practices: in 2011, 37% of respondents stated they rarely participated in religious ceremonies (excluding weddings and funerals), but by 2018, this figure plummeted to 11.1%.

Islam's prominence has grown across all age groups. In 2011, 57.9% of those under 29, 54.6% aged 30–49, and 35.4% aged 50 and older identified as Muslim. By 2018, these figures rose to 65.9%, 71.2%, and 63.4%, respectively. Conversely, the proportion identifying as Orthodox Christians decreased significantly, and the reduction in individuals not affiliating with any religion fell from 19.8% in 2011 to 8.1% in 2018 among those under 29.

The institutional development of Islam in Kazakhstan has been substantial. Kazakhstan has seen a rise in the number of religious associations and their branches. In the first three quarters of 2020, 2,685 Islamic organizations were registered, increasing to 2,832 during the same period in 2024 (Ministry of Religious Affairs of Kazakhstan, 2024a). By comparison, the number of Christian organizations remained relatively stable, with 347 new registrations in the first three quarters of 2024 compared to 342 in the same period in 2020.

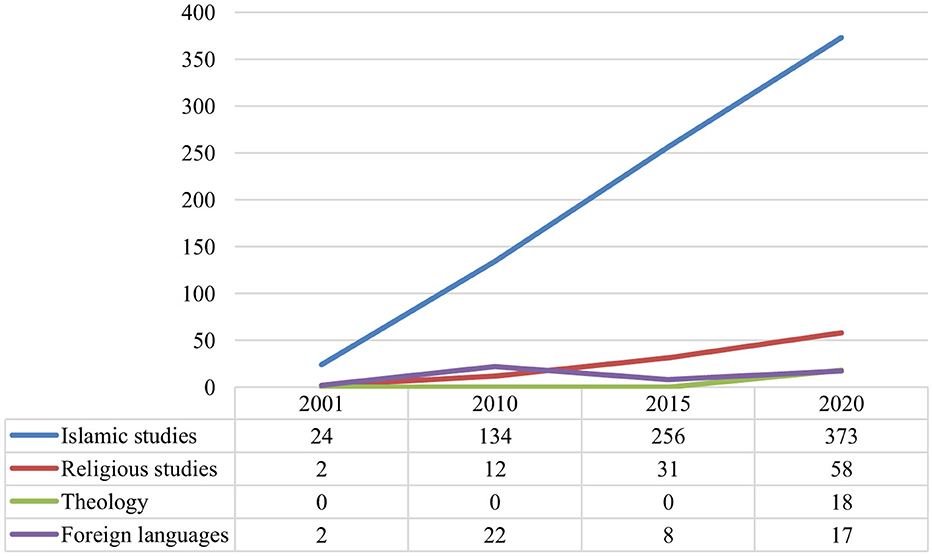

As of mid-2024, there were 14 religious educational institutions in Kazakhstan, enrolling over 5,500 students, according to the Ministry of Culture and Information (Ministry of Religious Affairs of Kazakhstan, 2024a). Among these, 12 institutions focus on Islamic teachings, including the Nur-Mubarak University, nine madrasah-colleges, the Islamic Institute for Imam Training, and the Husamuddin as-Syganaki Islamic Institute. Christian theology is taught in only two institutions: the Almaty Orthodox Theological Seminary and the Maria Mother of the Church Interdiocesan Higher Theological Seminary. The Nur-Mubarak University's Strategy (Nur-Mubarak University, 2022) indicates that employment rates among undergraduate students stood at 83%, master's students at 90%, and doctoral students at 99% (Figure 1). Between 2004 and 2020, more than 1,000 graduates joined the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Kazakhstan (SAMK), with others entering government institutions, education, or pursuing further studies.

Figure 1. Number of undergraduate students at Nur-Mubarak University. Source: Compiled by the author based on the University's Strategy for 2022–2026 (Nur-Mubarak University, 2022).

The most recent addition to religious educational institutions is the Husamuddin as-Syganaki Islamic Institute under SAMK, inaugurated in fall 2022 in Astana (Muftyat.kz, 2022a,b). According to SAMK Chairman N. T. Otpenov, the institute aims to enhance imams' knowledge, teach Arabic, and develop their abilities to explain religious matters, offering young people the opportunity to pursue quality spiritual education domestically rather than abroad.

3.3 Contemporary challenges and cultural tensions

The number of mosques in Kazakhstan has grown substantially since independence. According to the Head of Turkey's Directorate of Religious Affairs, A. Erbaş, Kazakhstan had only 68 mosques at the time of independence (Erbash, 2021). By 2021, this number had risen to at least 2,713 registered mosques under SAMK (Muftyat.kz, 2021), with 88 new mosques opened in 2023 alone (Azan.kz, 2024). This brings the total to 2,854 mosques, including 21 central, 406 urban, 165 district, and over 2,200 rural mosques. Kazakhstan also hosts more than 350 prayer halls, with nearly 300 mosques under construction as of early 2024.

According to a 2021 report by the U.S. Embassy and Consulate in Kazakhstan (U.S. Embassy Consulate in Kazakhstan, 2022), 22 religious organizations are officially banned under laws combating extremism, including groups like Hizb ut-Tahrir, the Taliban, and the Islamic State. However, in June 2024, the Taliban was removed from the banned organizations list as part of efforts to establish trade and economic ties with Afghanistan's new government (Deutsche Welle, 2024). These developments reflect the government's balancing act between security concerns and diplomatic pragmatism.

The Director of the Institute for Geopolitical Research and Professor at Nur-Mubarak University, A. Izbairov, noted in a 2023 interview that the number and influence of adherents of non-traditional religious movements have significantly decreased in recent years (Malim.kz, 2023). This is reflected in the decline of terrorist attacks, which peaked between 2011 and 2016. Traditional Islam continues to gain prominence in Kazakhstan, seen as a natural return to ancestral traditions and beliefs. However, non-traditional religious movements occasionally emerge, such as the “AllatRa” sect that became active in Almaty in 2023 (Golos Naroda, 2023), promoting an ideology combining elements of Islam, Judaism, and Christianity.

Since at least 2017, Kazakhstan has officially recognized Salafism as a significant threat to national security (Kazakhstanskaya Pravda, 2017). A SAMK spokesperson stated in 2011 that Salafism should be banned in Kazakhstan due to its dangerous nature (Online Zakon, 2011b). Public opinion data from Alash. Online revealed that as of November 2024, nearly 400 people supported a legislative ban on Salafism, while 22 opposed it (Alash Online, 2024). Officials argue that Salafism poses a threat to secular governance by advocating for the dismantling of secular institutions and suppression of other practices and religions (Nur.kz, 2024a).

Cultural tensions have emerged regarding Islamic dress codes, particularly the wearing of hijabs, niqabs, and burqas, which are considered foreign to Kazakhstan's cultural past (Open Society Foundations, 2016). In October 2023, Kazakhstan banned students and teachers from wearing hijabs in schools (UNN, 2023), sparking public debate and incidents of girls refusing to attend classes. President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev emphasized that schools are educational institutions where knowledge and skills are prioritized, while religion is a personal matter (UNN, 2023). During the March 2024 National Kurultai, Tokayev stated that the increasing number of people wearing black robes contradicts Kazakh norms and traditions, reflecting foreign influences rooted in religious fanaticism (Nur.kz, 2024b). Although media outlets claimed in September 2024 that Kazakhstan's Supreme Court ruled the hijab ban unlawful (Kursiv Media, 2024), this report was later refuted by the court [Jogargy Sot (Supreme Court of Kazakhstan), 2024].

The historical trajectory of Islam in Kazakhstan demonstrates its resilience and evolving role in society despite colonial, imperial, and Soviet efforts to suppress or control it. The modernization of Islam in Kazakhstan represents a complex, ongoing transformation involving increasing religious observance, state regulation of religious activities, and changes in religious policy. The government's approach reflects a commitment to building a secular state while ensuring religious stability, navigating between traditional Islamic revival and concerns about foreign religious influences.

4 Discussion

The historical trajectory of Islam in Kazakhstan reveals a complex interplay between religious identity, state policy, and social dynamics spanning over a millennium. The introduction of Islamic faith to Kazakh territories during the eighth to tenth centuries AD through Arab conquests established foundational religious structures that demonstrated remarkable resilience through subsequent political transformations (Malik and Khaki, 2021). Arab conquests by the mid-tenth century facilitated significant integration of Central Asia into Islamic civilization, with the establishment of Muslim state entities including the Karakhanid Khanate and the Seljuk Empire serving as institutional anchors for religious continuity (Zimonyi, 2024).

The permanence of Islamic establishment in the region, evidenced by close ties with the Arab Caliphate and sustained support from religious centers, distinguishes the Kazakhstani experience from temporary religious influences observed elsewhere. Laruelle (2021) emphasizes that during the Abbasid Caliphate period, Central Asia emerged as a key Islamic center, indicating that Islamization extended beyond the initial conquest period and continued through the Timurid era. This historical depth provides crucial context for understanding contemporary Islamic identity in Kazakhstan.

The Russian Imperial period introduced significant challenges to Islamic practice through attempted Christianization policies, which ultimately proved unsuccessful. The Tsarist government's subsequent control over Muslim religious activities reflects early state attempts to manage religious diversity (Cech, 2022). The concept of “Moscow as the Third Rome” and associated Russification policies represented systematic efforts to alter the religious landscape, yet these interventions failed to displace the established Islamic foundation.

The Soviet period marked the most intensive phase of religious suppression, with temporary relief during the New Economic Policy (NEP) followed by systematic religious repressions. Sadeh (2024) documents the precarious position of Soviet Muslims, noting that despite attendance at the 1926 Meccan Congress, the “stigmatized” status of Muslims reflected their extremely unstable position within the country. The demographic impact of these policies was substantial, with the Muslim population declining from 58.5% to 36% between 1926 and 1979 due to repressions (Ohayon, 2023).

However, the persistence of Islamic identity despite systematic suppression demonstrates the deep cultural embedding of religious practice. Rozkošová and Cech (2021) argue that while anti-religious propaganda weakened Islamic expression, certain privileges and periodic “thaw” periods enabled Muslims to preserve traditions and historical roots. By the late 1980s, between 20% and 80% of the population identified as Muslim, indicating significant variation in religious expression but consistent underlying identity maintenance.

The post-independence period witnessed dramatic religious revival, with Muslim identification rising to ~47% by 2001 (Rodriguez, 2023) and subsequently reaching nearly 70% of Kazakhstan's population according to recent census data (Omidi et al., 2024; Land et al., 2024). The establishment of a muftiate as the official representative of the country's Muslims in the 1990s (Jones and Menon, 2022) provided institutional framework for this revival. Kan (2024) documents the broader trend of rising religiosity in Kazakhstan after 1991, particularly among Muslims.

The infrastructure development accompanying religious revival has been substantial. From fewer than 70 mosques at independence—a consequence of Soviet-era closures of mosques and madrasahs (Zholdassuly, 2024)—the number grew by 100–150% in the first two decades of independence (Rodriguez, 2023). The expansion of religious organizations from 2,685 in 2020 to 2,832 in 2024 reflects this continued growth trajectory. Spiritual educational institutions have similarly expanded, with 12 of 14 existing institutions in 2024 relating to Islam, including universities such as “Nūr-Mubārak” offering Islamic studies programs.

Contemporary religious governance in Kazakhstan exemplifies what Boman (2023) characterizes as “parallelization of secularization and strong Islamic presence.” Despite constitutional secularism and statements by President Tokayev maintaining secular state principles, the government must balance religious freedom with security concerns. The prohibition of over 20 organizations, including the Muslim Brotherhood and ISIS, reflects security imperatives (Gamza and Jones, 2021) while regulatory frameworks attempt to maintain equilibrium between religious expression and state stability.

The management of Islamic diversity presents challenges regarding Salafist movements. Public opinion surveys and official statements indicate negative attitudes toward Salafism, reflecting concerns about potential threats to secular governance (Belhaj, 2024; De Koning, 2014). However, Olsson (2020) emphasizes the importance of distinguishing between different types of Salafism, as they do not necessarily represent uniform threats to state security.

Cultural expression through religious dress codes presents another dimension of state-religion negotiation. The wearing of traditional Eastern clothing elements, including niqabs, and restrictions on beard growth for men (Ozawa et al., 2024) illustrate the delicate balance between constitutional religious freedom guarantees and secular educational policies. Presidential statements emphasizing education over religion in schools reflect governmental attempts to maintain institutional secularism while accommodating religious diversity.

The Kazakhstani experience offers important insights into religious governance in post-communist societies. The remarkable persistence of Islamic identity through periods of systematic suppression, followed by rapid revival under conditions of political liberalization, demonstrates both the resilience of religious culture and the importance of institutional frameworks in facilitating religious expression. The contemporary challenge of balancing secular governance with majority Muslim population preferences reflects broader tensions between democratic governance and religious identity in diverse societies.

Future research should examine the long-term sustainability of the current secular-religious balance, particularly as global Islamic revival trends (Astuti and Asih, 2021) intersect with local Kazakhstani political and cultural dynamics. The effectiveness of current regulatory approaches in preventing religious extremism while maintaining religious freedom deserves continued scholarly attention, as does the role of educational institutions in shaping religious discourse and practice in contemporary Kazakhstan.

5 Conclusion

The establishment of Islam in the territory of contemporary Kazakhstan commenced during the eight century AD and was consolidated through Arab conquests in the subsequent century. The religion experienced rapid development and continued to flourish during the Timurid period, demonstrating the enduring nature of Islamic traditions in Kazakhstan. Despite prolonged periods of religious persecution under both the Russian Empire and the extensive repressions of the Soviet era, a substantial proportion of the population-maintained identification with, or sympathy toward, the Muslim faith.

Following Kazakhstan's independence, reliable demographic data regarding the Muslim population was initially unavailable. However, it may be reasonably assumed that both the numerical strength and social status of Muslims were considerably lower than contemporary levels. This decline resulted from decades of atheist policies implemented during the Soviet period and the institutional prevalence of non-Islamic religious centers. Nevertheless, the preservation and expansion of Muslim faith in Kazakhstan was first documented in the 2009 population census and subsequently confirmed by the 2021 census, wherein 70.2% and 69.3% of citizens, respectively, declared Islamic affiliation. These demographic trends received additional validation through independent surveys conducted by the World Values Survey, which demonstrated increased religiosity and enhanced religious observance practices.

In the context of national security considerations, the Kazakhstani government has prohibited dozens of radical Islamist organizations. Survey research conducted among Kazakhstani citizens indicates that approximately two-thirds of the population adheres to the Muslim faith, corroborating official census data.

State policy in Kazakhstan represents a delicate balance between maintaining secular governmental structures and accommodating the modernization of Islamic beliefs. The primary legislative framework governing the religious sphere is embodied in the “Law on Religious Activity and Religious Associations.” This legislation was formulated in response to terrorist incidents within Kazakhstan, establishing specific regulatory conditions for missionaries and other religious personnel while restricting certain religious activities in public spaces. Since independence, fourteen religious educational institutions have been established, twelve of which are Islamic, reflecting the institutional development and societal popularization of Islam. The mosque infrastructure has expanded dramatically from merely 68 establishments in 1991 to nearly 3,000 by 2024, with additional construction projects ongoing. The practice of wearing headscarves in educational institutions gained popularity, creating tension with perceived national characteristics and ultimately resulting in governmental prohibition.

This analysis yields several key conclusions regarding the transformation of the religious component in post-Soviet Kazakhstan. The research reveals complex dynamics in Islamic development, characterized by both historical continuity and contemporary re-Islamization trends. Demographic analysis of census data demonstrates a significant increase in citizens identifying as Muslims, indicating Islam's expanding role in the socio-cultural landscape of independent Kazakhstan. The study identifies primary mechanisms of state regulation within the religious sphere, designed to maintain interfaith harmony while preventing religious extremism. These findings support the conclusion that Kazakhstan has developed a distinctive model of state-confessional relations, successfully combining secular governance with recognition of Islam's historical significance in Kazakhstani society's development.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Validation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Supervision, Investigation, Funding acquisition. NS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. MN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Formal analysis, Resources, Project administration, Software, Data curation, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research has been funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. BR BR21882428 “The influence and prospects of Islam as a spiritual, cultural, political, and social phenomenon in postnormal times: the experience of the countries of the Middle East and Central Asia”).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alash Online (2024). Initiative for a Legislative Ban on Salafism in Kazakhstan. Available online at: https://alash.online/1687-zapret.html (Accessed July 19, 2024).

Astuti, Y., and Asih, D. (2021). Country of origin, religiosity and halal awareness: a case study of purchase intention of korean food. J. Asian Fin. Econ. Bus. 8, 413–421. doi: 10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no4.0413

Azan.kz (2024). 88 Mosques Opened in Kazakhstan in 2023. Available online at: https://azan.kz/ahbar/read/88-mechetey-otkryilos-v-kazahstane-za-2023-god-14958 (Accessed February 4, 2025).

Belhaj, A. (2024). Secularism as an anti-religious conspiracy: salafi challenges to French Laïcité. Religions 15, 1–17. doi: 10.3390/rel15050546

Beyer, J., and Finke, P. (2019). Practices of traditionalization in Central Asia. Cent. Asian Surv. 38, 310–328. doi: 10.1080/02634937.2019.1636766

Boman, B. (2023). “Secularization and the resurgence of religions,” in Parallelization: A Theory of Cultural, Economic and Political Complexity, ed. B. Boman (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland), 23–32.

CABAR Asia (2020). “They Say” Podcast: Is It True That People Who Practice Islam Should Be Feared? Available online at: https://cabar.asia/en/they-say-podcast-is-it-true-that-people-who-practice-islam-should-be-feared (Accessed November 7, 2024).

CABAR Asia (2022). How the Number of Believers in Kazakhstan Changed. Available online at: https://cabar.asia/ru/kak-izmenilos-kolichestvo-veruyushhih-v-kazahstane (Accessed July 11, 2024).

CABAR Asia (2024a). Kazakhstanis Have Become More Religious. Available online at: https://cabar.asia/ru/kazahstantsy-stali-bolee-religioznymi (Accessed January 19, 2025).

CABAR Asia (2024b). What Was the Traditional Religion of the Kazakhs? Available online at: https://cabar.asia/ru/kakoj-byla-traditsionnaya-religiya-kazahov (Accessed January 27, 2025).

Cech, L. (2022). Islam in the history of Russia: confrontation vs. cooperation. EUrASEANs J. Global Socio Econ. Dyn. 1, 99–105. doi: 10.35678/2539-5645.1(32).2022.99-105

Committee on Religious Affairs of the Ministry of Culture and Information of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2020). Number of Registered Religious Organizations and Their Branches. Available online at: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/din/documents/details/73240?lang=ru (Accessed February 20, 2025).

Committee on Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan (1999). Population Census. Available online at: https://stat.gov.kz/ru/national/1999/ (Accessed October 7, 2024).

Committee on Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2011). Population Census. Available online at: https://stat.gov.kz/ru/national/2009/general/ (Accessed October 15, 2024).

Committee on Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2022). Population Census. Available online at: https://stat.gov.kz/ru/national/2021/ (Accessed October 23, 2024).

Cornell, S. E., Starr, S. F., and Tucker, J. (2018). Religion and the Secular State in Kazakhstan. Stockholm: Institute for Security and Development Policy.

De Koning, M. (2014). Between the Prophet and Paradise: the Salafi struggle in the Netherlands. Can. J. Netherlandic Stud. 33, 34, 17–34. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281376874_Between_the_Prophet_and_Paradise_The_Salafi_struggle_in_the_Netherlands

Deutsche Welle (2024). Kazakhstan Excluded the ‘Taliban' from the List of Terrorist Organizations. Available online at: https://www.dw.com/ru/kazahstan-isklucil-taliban-iz-spiska-terroristiceskih-organizacij/a-69255242 (Accessed August 12, 2024).

Dinasheva, L. S., Kattabekova, N. K., and Jahangir, I. u. (2023). XIX g. sony - XX g. basynda Osman imperiiasy men Resei turkilerindegi dini jane zaiyrly bilim reformalary [Reforms of Religious and Secular Education among the Turks of the Osman Empire and Russia in the late XIX - early XX centuries]. Ясауи _университетінің _хабаршысы. 1, 479–493. doi: 10.47526/2023-1/2664-0686.43

E-history.kz (2013). History of Protestantism in Kazakhstan. Available online at: https://e-history.kz/ru/e-resources/show/13379 (Accessed July 3, 2024).

E-history.kz (2021). Islam in Kazakhstan. Available online at: https://e-history.kz/ru/news/show/32645 (Accessed July 27, 2024).

Erbash, A. (2021). Radical Movements Must Not Be Allowed to Strengthen in Kazakhstan. Available online at: http://surl.li/hqoxzn (Accessed February 12, 2025).

Gamza, D., and Jones, P. (2021). The evolution of religious regulation in Central Asia, 1991–2018. Cent. Asian Surv. 40, 197–221. doi: 10.1080/02634937.2020.1836477

Golos Naroda (2023). New Sect: Kazakhstanis Await the End of the World on July 27. Available online at: https://golos-naroda.kz/15249-novaia-sekta-kazakhstantsy-zhdut-kontsa-sveta-27-iiulia-1687343431/ (Accessed September 5, 2024).

Jogargy Sot (Supreme Court of Kazakhstan) (2024). The Supreme Court Has Not Lifted the Ban on Wearing Headscarves in Schools (Telegram post). Available online at: https://t.me/Jogargy_sot/3603 (Accessed December 18, 2024).

Jones, P., and Menon, A. (2022). Trust in religious leaders and voluntary compliance: lessons from social distancing during COVID-19 in Central Asia. J. Sci. Study Relig. 61, 583–602. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12804

Jumashov, R. M., and Sadvokasov, Sh. A. (2022). The history of the revival of Islam in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Bull. Karaganda Univ. Hist. Philos. Ser. 108, 63–71. doi: 10.31489/2022hph4/63-71

Kan, M. (2024). Religion and contraceptive use in Kazakhstan. Demogr. Res. 50, 547–582. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2024.50.21

Kartabayeva, E. (2019). Jadidism - a movement for the modernization of Islam at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. J. Hist. 94, 72–81. doi: 10.26577/jh-2019-3-h9

Kassimbekova, M. (2024). Орталық Aзиядағы «Ислам Жаңғыруы» Mәселесінің (Қазіргі Тарихнамалық Еңбектер Бойынша). Trk Dergisi 5, 22–33. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.12637484

Kazakhstanskaya Pravda (2017). The KNB Named the Main Source of Terrorist Threats to Kazakhstan. Available online at: https://kazpravda.kz/n/v-knb-nazvali-glavnyy-istochnik-terroristicheskoy-ugrozy-dlya-kazahstana/ (Accessed December 10, 2024).

Kursiv Media (2024). The Supreme Court of Kazakhstan Considered the Ban on Wearing Headscarves in Schools Illegal. Available online at: https://kz.kursiv.media/2024-09-25/lsbs-platok/ (Accessed December 26, 2024).

Land, S., Neafie, J. E., and Courtney, M. G. (2024). The role of identity and strategic narratives on public perceptions of china: the case of the new silk road in Kazakhstan. Area Dev. Policy. 9, 568–590. doi: 10.1080/23792949.2024.2376322

Laruelle, M. (2021). Central Peripheries: Nationhood in Central Asia. London: UCL Press. Available online at: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/51805. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1gn3t79

Malik, B. A., and Khaki, G. N. (2021). Historical overview of Islam in Kazakhstan: from the Arab Islamization to soviet oppression. J. Cent. Asian Stud. 28, 37–68. Available online at: https://ccas.uok.edu.in/Files/93269b6c-7f53-4439-ae9a-3bdf55a4c649/Journal/3283e044-479e-4cbe-a7b3-6729029d632f.pdf

Malim.kz (2023). Islamization in Kazakhstan: Growing Pains or Real Threat? Available online at: https://malim.kz/article/analytics/islamizaciya-v-kazaxstane-bolezn-rosta-ili-realnaya-ugroza-20010 (Accessed August 4, 2024).

Masa Media (2023). Terrorist Attacks in Kazakhstan Since Independence. Available online at: https://masa.media/ru/site/kakie-terakty-proiskhodili-v-kazakhstane-s-obreteniya-nezavisimosti (Accessed November 8, 2024).

Ministry of Religious Affairs of Kazakhstan (2024a). List of Registered Religious Organizations and Their Branches. Available online at: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/din/documents/details/733733?lang=ru (Accessed October 31, 2024).

Ministry of Religious Affairs of Kazakhstan (2024b). Religious Sphere. Available online at: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/qogam/activities/141?lang=ru (Accessed August 28, 2024).

Muftyat.kz (2021). Annual Report 2021: 68 Mosques Were Built. Available online at: https://www.muftyat.kz/ru/news/qmdb/2021-12-30/38428-godovoi-otchet-2021-byli-postroeny-68-mechetei/ (Accessed June 25, 2024).

Muftyat.kz (2022a). The As-Syganaki Institute Branch Opened in Almaty. Available online at: https://www.muftyat.kz/ru/articles/qmdb/2022-10-09/40603-v-almaty-otkrylsia-filial-instituta-as-syganaki-foto/ (Accessed November 24, 2024).

Muftyat.kz (2022b). The Islamic Institute Named after Husamuddin As-Syganaki Opened in the Capital. Available online at: https://www.muftyat.kz/ru/news/qmdb/2022-09-08/40325-v-stolitse-otkrylsia-islamskii-institut-imeni-khusamuddin-as-syganaki-foto/ (Accessed December 2, 2024).

Mukan, A., Borbassova, K., and Issaeva, L. (2023). Traditional Islam and its impact on the dynamics of integration and disintegration processes of the national identity of society. Eurasian J. Relig. Stud. 35, 48–58. doi: 10.26577//EJRS.2023.v35.i3.r5

New Economic Policy (2024). Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Available online at: https://bse.slovaronline.com/23330-NOVAYA_EKONOMICHESKAYA_POLITIKA (Accessed August 11, 2025).

Nur.kz (2024a). Tokayev Clearly Defined Kazakhstan's Position on Religious Fundamentalism and Salafism. Available online at: https://www.nur.kz/society/2118192-tokaev-chetko-oboznachil-poziciyu-rk-v-otnoshenii-religioznogo-fundamentalizma-i-salafizma-schitaet-ekspert-v-koltochnik/ (Accessed January 3, 2025).

Nur.kz (2024b). ‘Everyone Knows This': Tokayev Spoke About People Wrapped in Black Clothes. Available online at: https://www.nur.kz/politics/kazakhstan/2069061-vse-ob-etom-znayut-tokaev-vyskazalsya-o-lyudyah-zakutannyh-v-chernye-odeyaniya/ (Accessed January 11, 2025).

Nur-Mubarak University (2022). Nur-Mubarak Egyptian Islamic Culture University Strategy 2022-2026. Available online at: https://www.nmu.edu.kz/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/2022-2026-Strategic-plan-RUS.pdf (Accessed September 13, 2024).

Ohayon, I. (2023). Documenting Kazakh funeral rituals through material life indicators (1960s−1980s). Geistes-, Sozial-und Kulturwissenschaftlicher Anzeiger 1, 83–106. doi: 10.1553/anzeiger157-1s83

Olcott, M. B. (2023). “Islam and fundamentalism in independent Central Asia,” in Muslim Eurasia, ed. Y. Ro'I (London: Routledge), 21–39.

Olsson, S. (2020). ‘True, masculine men are not like women!': salafism between extremism and democracy. Religions 11, 1–16. doi: 10.3390/rel11030118

Omidi, A., Khan, K. H., and Schortz, O. (2024). Explaining the vicious circle of political repression and islamic radicalism in Central Asia. Cogent Soc. Sci. 10, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2024.2350115

Online Zakon (2011a). On Religious Activities and Religious Organizations. Available online at: https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=31067690andpos=3;-108#pos=3;-108 (Accessed September 21, 2024).

Online Zakon (2011b). Salafism Has Become a Dangerous Religious Movement in Kazakhstan - DUMK. Available online at: https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=31025973andpos=4;-57#pos=4;-57 (Accessed September 29, 2024).

Open Society Foundations (2016). I Avoid Places Where the Niqab is Banned. Available online at: https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/i-avoid-places-where-niqab-banned (Accessed August 11, 2025).

Ozawa, V., Durrani, N., and Thibault, H. (2024). The political economy of education in central Asia: exploring the fault lines of social cohesion. Glob. Soc. Educ. 1–14. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2024.2330361

Rodriguez, E. B. (2023). Religion and state in Central Asia: a comparative regional approach. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Res. Rev. 6, 79–99. doi: 10.47814/ijssrr.v6i1.766

Rozkošová, Z., and Cech, L. (2021). Seeking a place for Islam in post-soviet Russia. Przeglad Strategiczny 14, 183–197. doi: 10.14746/ps.2021.1.11

Sadeh, R. B. (2024). Worldmaking in the Hijaz: Muslims between South Asian and Soviet Visions of Managing Difference, 1919–1926. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 66, 185–212. doi: 10.1017/S0010417523000324

Sartori, P. (2021). “On the importance of having a method: reading atheistic documents on Islamic revival in 1950s Central Asia,” in From the Khan's Oven, eds. E. Tasar et al. (Leiden: Brill), 284–322.

The Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) (2020). National/Regional Profiles of Kazakhstan. Available online at: https://www.thearda.com/world-religion/national-profiles?u=120c (Accessed September 9, 2024).

Toleubay, A., Kassymbekova, B., and Nurlanbekova, G. (2024). The dynamics of Islam in Kazakhstan from an educational perspective. Religions 15:1243. doi: 10.3390/rel15101243

U.S. Embassy and Consulate in Kazakhstan (2022). Kazakhstan: 2021 Report on Religious Freedom. Available online at: https://kz.usembassy.gov/ru/ru-2021-report-on-international-religious-freedom-kazakhstan-2/ (Accessed August 20, 2024).

UNN (2023). Kazakhstan Announced a Hijab Ban in Schools. Available online at: https://unn.ua/ru/news/kazakhstan-ogolosiv-pro-zaboronu-khidzhabiv-u-shkolakh

Zholdassuly, T. (2024). Sovyet Kazakistan'inda Tasavvuf: Komünistlerin Yesevilik ve Işanlara Yönelik Faaliyeti. Türk Kültürü ve Haci Bektaş Veli Araştirma Dergisi 109, 49–78. doi: 10.60163/hbv.109.001

Zhumagulov, K., and Kartabayeva, E. (2020). The role of Islam in modernization processes in kazakhstan. J. Hist. 97, 128–136. doi: 10.26577/JH.2020.v97.i2.14

Zhusupova, A., and Sabitov, Z. (2024). The importance of tribal affiliation among Kazakhs in modern-day Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan Spectr. 111. doi: 10.52536/2415-8216.2024-3.08

Keywords: religious policy, state regulation, secularism, national security, Muslim identity

Citation: Zhandossova S, Seitakhmetova N and Nurov M (2025) Religious policy of Kazakhstan: mechanisms for managing the Islamic environment amid post-soviet transformation. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1606705. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1606705

Received: 06 April 2025; Accepted: 08 August 2025;

Published: 01 September 2025.

Edited by:

Oliver Fernando Hidalgo, University of Passau, GermanyReviewed by:

Sulaimon Adigun Muse, Lagos State University of Education LASUED, NigeriaMohammad Rindu Fajar Islamy, Indonesia University of Education, Indonesia

Zhuldyz Kabidenova, Toraighyrov University, Kazakhstan

Copyright © 2025 Zhandossova, Seitakhmetova and Nurov. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marhabbat Nurov, bWFya2hhYmJhdG51ckBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Sholpan Zhandossova

Sholpan Zhandossova Natalya Seitakhmetova

Natalya Seitakhmetova Marhabbat Nurov

Marhabbat Nurov